Abstract

Purpose

Online pharmacies (OPs) represent a growing field that plays a major role in providing pharmaceutical services in Saudi Arabia (SA). Thus, investigating public awareness of this option and assessing consumers’ experiences and satisfaction, as well as opportunities and barriers for OPs, were the main aims of this study.

Participants and methods

In this cross-sectional study, adult participants (≥18 years) in SA completed a three-part, custom-designed online questionnaire. The first section collected information on participants’ demographic characteristics, their awareness of the existence of OPs, and history of OP purchases. The second section explores customer satisfaction levels and motivating factors. Finally, the third section investigated non-consumers’ reasons for not purchasing from OPs and sought information about services that could motivate them to make future purchase decisions.

Results

In total, 487 participants completed the questionnaire; they were mostly female (65.7%) and younger than 40 years (57.1%). Among all the respondents, 89.3% were aware of the existence of OPs, and 60.2% purchased from OPs in the past. Most were satisfied with the product quality (92.7%), completeness of order delivery (91.2%), and condition of the product and packaging (89.3%). Furthermore, 99.2% of respondents indicated that they would continue to purchase from OPs. Customers’ main motivational factors included saving time (85.5%), offers and discounts (83.6%), and variety of products (82.1%). Among non-consumers, the main reasons for not purchasing from OPs included a personal preference to visit a community pharmacy (87.2%), the ability to talk to pharmacists directly (83.6%), and the vicinity of a pharmacy (80.0%).

Conclusions

These findings confirm the increasing level of awareness regarding the existence of OPs in SA. Overall, OP customers expressed satisfaction with the services provided. Nevertheless, various areas of improvement have emerged, such as improved delivery time and providing medical consultation services. Increasing public awareness of OP services provided is essential considering their significant role in reforming the healthcare system in SA.

Keywords: Online Pharmacy, Saudi Arabia, Satisfaction, Motivation, Barriers, Experience, Consumers, Non-consumers

1. Introduction

Online shopping affects public behavior in terms of purchasing products and services. Currently, many customers buy medications and health products from online pharmacies (OPs) (Singh et al., 2020). In Saudi Arabia (SA), public purchase behavior involving OPs has gradually increased (Abanmy, 2017, Alwhaibi et al., 2021). Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which imposed quarantine and self-isolation worldwide, OPs provided patients and other consumers with the opportunity to enhance their access to products, including medications and services, which was reflected in increased sales and dispensing of medications through OPs (Fittler et al., 2022a, Ozawa et al., 2022).

In 2013, most SA residents had never heard of OPs, and there were no local pharmacies with online stores. Specifically, only 23% of people were aware of OPs, and of those, only 2.7% had bought medicines from an OP (Abanmy, 2017). Later, OPs gained popularity as an online industry, and multiple factors were found to influence public behavior and experiences with OPs in SA. In general, individuals’ use of the Internet and social media affects their online buying behavior; for OPs, in particular, the quality of medicinal products and delivery time influence public experience and satisfaction (Alwhaibi et al., 2021).

A comparison of patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical services provided by OPs and community pharmacies revealed that OP customers had a higher level of satisfaction with prices than community pharmacy customers, whereas the latter had a higher level of satisfaction with counseling (Govender and Suleman, 2019). In studies conducted in SA measuring the satisfaction levels of those who purchased medicines or other products from OPs in 2013 and 2020, most participants reported high satisfaction levels. However, these studies measured customer satisfaction levels in general, without examining the details of consumer satisfaction with other services provided by OPs (Abanmy, 2017, Alwhaibi et al., 2021).

Currently, OPs play a major role in providing pharmaceutical care services; for example, many OPs offer virtual follow-ups, counseling, processing and dispensing of electronic prescriptions, and the delivery of medications and orders to patients. These functions provide opportunities for pharmacists to deliver pharmaceutical care services (Ding et al., 2020), many of which are now offered by OPs in SA (Ahmad et al., 2020). However, the process of developing any service includes the need to address barriers and opportunities to implement and develop the service. In the case of OPs, these businesses face various obstacles, including a lack of market regulations, poor consideration of private sector interests, a lack of trust in community pharmacies’ ability to provide OP services, and limited organizational budgets and resources (Abu Bakar et al., 2022). The existence of illegitimate OPs that sell counterfeit medications and products or dispense prescribed medications without prescriptions, along with cybersecurity concerns including consumer fraud and the lack of protection of personal data, can have detrimental economic, social, and health-related consequences (Fincham, 2021). Despite these potential barriers, legitimate OPs have seized opportunities to conduct business based on their ability to enhance public access to medicines, medical devices, and health products, particularly for those with limited access to community pharmacies (Miller et al., 2021).

Since the onset of the pandemic, OPs have emerged as a public health necessity. Thus, understanding consumers’ experiences and current satisfaction with OP services is vital to improving the quality of services provided in the future. Identifying opportunities and barriers that affect consumer purchasing or usage behavior is critical. Identifying opportunities and investigating obstacles in this area can increase public awareness of available resources, increase access to valuable pharmacy services, and equip stakeholders with strategies to overcome obstacles to developing the growing OP market.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design, participants, and data collection

A cross-sectional study was conducted using a custom-designed online questionnaire distributed through social media platforms from October 2022 to January 2023. This study, which was limited to Arabic-speaking adults aged 18 years and older living in SA, aimed to explore participants’ awareness, usage, experience, and satisfaction with OPs as well as the opportunities and barriers for OPs in SA. Participation was voluntary, and no identifying information was collected to ensure the privacy of study participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Saud University Medical City (No. E-22–7131).

2.2. Development of the survey

The questionnaire was developed after reviewing the published literature to identify gaps regarding OPs. Four junior researchers developed the questionnaire, which was then reviewed and edited by two senior researchers with expertise in the field of social pharmacies. Next, four additional experts from the fields of social pharmacy and pharmacy practice reviewed the questionnaire for validity. The questionnaire was amended based on their feedback. The survey was developed and distributed in Arabic, translated into English by two investigators, and reviewed by two other investigators for publication purposes. The survey was then distributed to a small sample (10 participants) to pilot test the questionnaire for clarity and to evaluate the final draft of the online survey before public distribution. The pilot study did not result in any further changes.

The first section of this three-part survey collected information on demographic characteristics of the participants (e.g., age, gender, region of residence, and marital status), awareness of the existence of OPs and history of OP purchases. The second section, which was limited to consumers who had purchased from OP in the past, investigated the motivating factors for buying from OPs, consumers’ experiences and satisfaction with products and services ordered from OPs, and whether they planned to buy from OPs in the future. Finally, the third section addressed people who had never purchased from OPs and investigated the reasons why the participants did not choose to purchase from an OP, any plans to order products or services from OPs, and the products that these participants might be willing to buy in the future.

2.3. Data analysis

The study data included categorical variables (yes/no, a five-point Likert scale, or other relevant categories displayed in the tables) and are presented as frequencies with percentages. The chi-square test was used to investigate the differences among participant groups in awareness of OPs and purchasing from these pharmacies. An α level of < 0.05 was forest as statistical significance. Data were collected using Google Forms, imported into Excel, and analyzed using SAS statistical analytics software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Participant demographics

A total of 487 respondents participated in the study; 57.1% were younger than 40 years, and 65.7% were female. Most respondents (63.0%) were from the central region of SA, more than half were married (53.0%), and two-thirds had children living in the same household. Most respondents were aware of OPs (89.3%), and 60.2% of these participants reported having previous experience of purchasing from an OP. Participants younger than 40 years were more likely to be aware of OPs (92.1% vs. 85.7%; p = 0.023) and purchase from OPs (64.8% vs. 53.6%; p = 0.018) than older participants. Compared to women, men were less likely to be aware of OPs (91.6% vs. 85.0%; p = 0.027) and if they were aware of OPs, they were less likely to purchase from them (67.2% vs. 45.8%; p < 0.001). Participants living with children were more likely to be aware of OPs than those who did not. Moreover, participants with higher educational levels were more likely to purchase from OPs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| Characteristics and categories |

Overall n (%) |

Recognized the existence of online pharmacies |

Previously purchased from online pharmacies* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | p-value** | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | p-value** | ||

| Number of participants, n (%) | 487 (100.0) | 52 (10.7) | 435 (89.3) | 173 (39.8) | 262 (60.2) | ||

| Age | 0.023 | 0.018 | |||||

| < 40 years | 278 (57.1) | 22 (7.9) | 256 (92.1) | 90 (35.2) | 166 (64.8) | ||

| ≥ 40 years | 209 (42.9) | 30 (14.3) | 179 (85.7) | 83 (46.4) | 96 (53.6) | ||

| Gender | 0.027 | <0.001 | |||||

| Male | 167 (34.3) | 25 (15.0) | 142 (85.0) | 77 (54.2) | 65 (45.8) | ||

| Female | 320 (65.7) | 27 (8.4) | 293 (91.6) | 96 (32.8) | 197 (67.2) | ||

| Region of residence | 0.179 | 0.064 | |||||

| Central Region | 307 (63.0) | 32 (10.4) | 275 (89.6) | 95 (34.5) | 180 (65.5) | ||

| Western Region | 101 (20.7) | 16 (15.8) | 85 (84.2) | 42 (49.4) | 43 (50.6) | ||

| Eastern Region | 57 (11.7) | 4 (7.0) | 53 (92.9) | 25 (47.2) | 28 (52.8) | ||

| Southern Region | 17 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (100.0) | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | ||

| Northern Region | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Marital status | 0.060 | 0.809 | |||||

| Married | 258 (53.0) | 35 (13.6) | 223 (86.4) | 93 (41.7) | 130 (58.3) | ||

| Single | 205 (42.1) | 13 (6.3) | 192 (93.7) | 73 (38.0) | 119 (62.0) | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 16 (3.3) | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.2) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | ||

| Widowed | 8 (1.6) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | ||

| Children living in the same house | 0.017 | 0.688 | |||||

| Yes | 332 (68.2) | 43 (5.8) | 289 (94.2) | 113 (39.1) | 176 (60.9) | ||

| No | 155 (31.8) | 9 (13.0) | 146 (87.0) | 60 (41.1) | 86 (58.9) | ||

| Level of education | 0.700 | 0.041 | |||||

| Less than High School | 15 (3.1) | 3 (20.0) | 12 (80.0) | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | ||

| High School | 83 (17.0) | 7 (8.4) | 76 (91.6) | 31 (40.8) | 45 (59.2) | ||

| Diploma | 76 (15.6) | 9 (11.8) | 67 (88.2) | 32 (47.8) | 35 (52.2) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 255 (52.4) | 28 (11.0) | 227 (89.0) | 80 (35.2) | 147 (64.8) | ||

| Higher education (Master’s degree or Ph.D.) | 58 (11.9) | 5 (8.6) | 53 (91.4) | 21 (39.6) | 32 (60.4) | ||

| Job status | 0.144 | 0.270 | |||||

| Employee | 228 (46.8) | 30 (13.2) | 198 (86.8) | 88 (44.4) | 110 (55.6) | ||

| Student | 114 (23.4) | 5 (4.4) | 109 (95.6) | 37 (33.9) | 72 (66.1) | ||

| Unemployed/looking for a job | 42 (8.6) | 4 (9.5) | 38 (90.5) | 12 (31.6) | 26 (68.4) | ||

| Housewife | 45 (9.3) | 5 (11.1) | 40 (88.9) | 14 (35.0) | 26 (65.0) | ||

| Retired | 58 (11.9) | 8 (13.8) | 50 (86.2) | 22 (44.0) | 28 (56.0) | ||

Results are presented as frequency (%).

This include 435 participants who recognized the existence of online pharmacies (OPs).

p-values are from the chi-square test; values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Numbers in bold indicate significant results.

3.2. Participants with OP experience

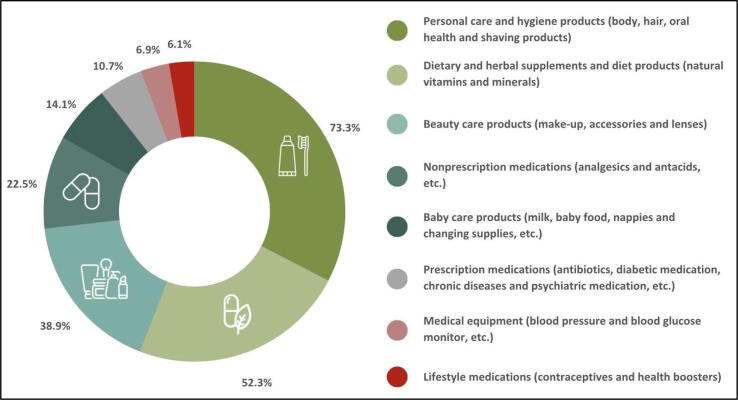

Most participants with experience with OPs (n = 262) ordered products from international OPs (68.7%) with or without ordering from local OPs (Fig. 1). More than half of the participants (53.4%) had purchased from any OP within the last three months, and 35.5% of the participants had purchased only once from any OP during the last three months (Table 2). The products most purchased from OPs were personal care items, followed by dietary or herbal supplements, beauty care products, and over-the-counter (OTC) medications. The least ordered products were medical equipment and lifestyle medications (Fig. 2). Based on previous experiences, most participants indicated that they would continue to purchase from OPs (99.2%).

Fig. 1.

The type of online pharmacies that consumers purchased products or healthcare services from. This question was asked to participants who have purchased from OPs only (n = 262/487).

Table 2.

Consumers purchasing experience with online pharmacy.*.

| Items | N (%) |

|---|---|

| When was the last time you purchased from online pharmacies? | |

| Within the past 3 months | 140 (53.4) |

| Within the past 6 months | 50 (19.1) |

| Within a year or more | 72 (27.5) |

| Approximately during the last three months, what is the monthly average of your orders from online pharmacies? | |

| I haven’t ordered from them in the past 3 months | 94 (35.9) |

| Once | 93 (35.5) |

| Twice | 45 (17.1) |

| Three times or more | 30 (11.5) |

| If online pharmacies provide the service of dispensing and delivering medicines prescribed by hospitals, would you accept this service? | |

| Yes, or Maybe | 256 (97.7) |

| No | 6 (2.3) |

| Have you ordered prescribed medications from online pharmacies? | |

| Yes | 59 (22.5) |

| No | 203 (77.5) |

| When you ordered prescribed medications from online pharmacy, were you counseled by pharmacists about the medication?** | |

| Yes | 38 (64.4) |

| No | 21 (35.6) |

| When you ordered prescribed medications from online pharmacy, were instructive labels placed on the medication received?** | |

| Yes | 47 (79.7) |

| No | 12 (20.3) |

These questions were asked to participants who have purchased from OPs only (n = 262/487).

This include participants who have ordered prescribed medication only (n = 59/262).

Fig. 2.

The type of products that consumers purchased from online pharmacies.This question was asked to participants who have purchased from OPs only (n = 262/487).

Although 97.7% of the participants (256/262) accepted the use of OP dispensing and delivery services for prescribed medications, only 22.5% (59/262) of them ordered prescription drugs through OPs. Among those who ordered prescription drugs, 35.6% did not receive any counseling, whereas 79.7% received instructive labeling of the delivered medications. Additionally, approximately two-thirds of the participants who had experience with OPs were aware of the availability of online pharmaceutical or medical services (such as receiving a consultation with a pharmacist), but only 16.5% had used any of these services. Of the 43 participants who used online services, 90.7% were satisfied or completely satisfied (Table 2).

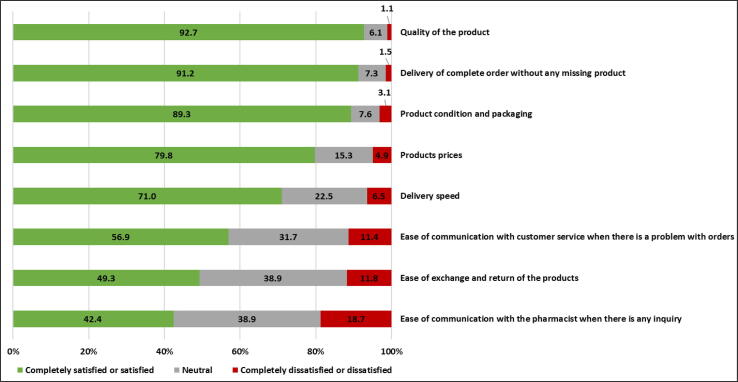

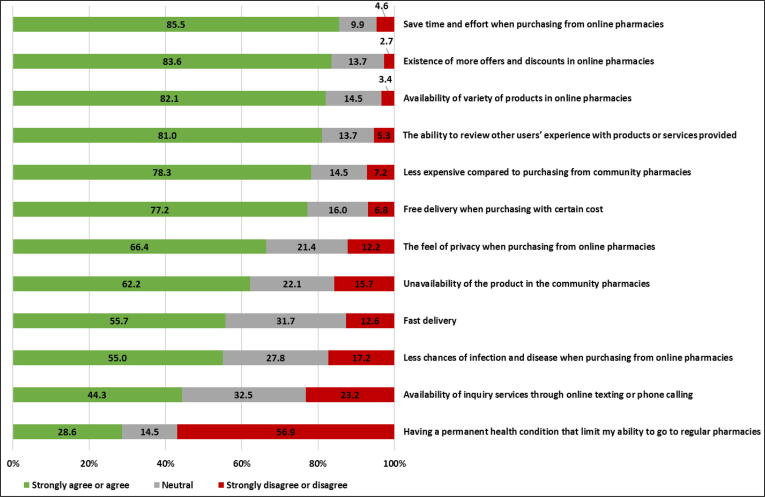

Most respondents were overall satisfied with the OPs. The main reasons included satisfaction with the quality of the delivered product, delivery of an entire order with no missing items, and condition of the product and packaging on delivery. Approximately 79.8% of the participants were satisfied or completely satisfied with the prices of the delivered products; however, only 71.0% were satisfied with the speed of delivery. Finally, only 56.9% of the consumers were satisfied with the ease of communication with customer service in case of problems with their orders, and only half of the participants were satisfied with the ease of the exchange and return processes. The most common area of dissatisfaction was the ease of communication with pharmacists when there was an inquiry; specifically, only 42.4% of all participants were satisfied with their experience in this area, compared to 18.7% who were not satisfied. The details of consumer satisfaction with their experiences are summarized in Fig. 3. Customers agreed or strongly agreed that the main motivational factors for them to purchase from OPs were saving time, offers and discounts, the availability of a variety of products compared with community pharmacies, the ability to review other users’ experiences before buying these products, and lower costs compared with purchasing from community pharmacies; the reasons for using OPs are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Consumers’ satisfaction with the purchasing experience from online pharmacy These questions were asked to participants who have purchased from OPs only (n = 262/487).

Fig. 4.

Consumers’ motivational factors for purchasing from online pharmacies These questions were asked to participants who have purchased from OPs only (n = 262/487).

3.3. Participants without OP experience

The reasons for not purchasing from online pharmacies that were most likely to be rated “agree” or “strongly agree” included the participants’ preference to go to regular pharmacies to check available products and receive their medications from the pharmacy while speaking to a pharmacist, along with a community pharmacy located in the participants’ neighborhood. In addition, many of these non-customers were concerned that the delivered product might not be suitable for their own health condition or that of their relatives, had difficulty differentiating between legitimate and illegitimate OPs, experienced difficulty communicating with a pharmacist to inquire about products, or had concerns about receiving counterfeit or ingenuine products. Interestingly, many participants “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” that not knowing about OPs (41.3%), lack of availability of OP services in their area (37.3%), and lack of knowledge about how to purchase or upload prescriptions to OPs (27.0%) were the reasons for their decision not to order from OPs. Fig. 5 lists the reasons for not buying from OPs, based on their importance to the participants.

Fig. 5.

Reasons why participants may not purchase from online pharmacies These questions were asked to participants who have not purchased from OPs only (n = 225/487).

However, most participants (95.1%) who had never purchased OPs indicated that they intended to or might eventually purchase from OPs. Furthermore, 96.0% answered that they would or might accept services from OPs that dispense or deliver medications prescribed by hospitals. Moreover, many non-consumers indicated that they would consider purchasing from OPs that could provide medical consultation services and rapid communication with pharmacists, deliver products in good condition, and ensure product compatibility with other medications and health conditions. By contrast, the least attractive aspect of OPs for non-consumers related to constant updates to information about the availability of drugs at OPs. Table 3 summarizes these services. Finally, the survey responses indicated that when non-consumers decide to buy from OPs, the majority would mainly purchase personal care and hygiene products, dietary or herbal supplements, OTC medications, or beauty care products (Table 3).

Table 3.

Non-consumers future purchasing behavior*.

| Items | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Services that if provided by online pharmacies the non-consumers would consider purchasing from online pharmacies in the future?** | |

| Providing medical consultation services and quick communication with pharmacist | 187 (83.1) |

| Ensure delivering products in good condition and taking responsibility for any damage | 149 (66.2) |

| Providing services to ensure that the purchased product doesn’t interfere with your medications or health condition | 148 (65.8) |

| Ensure the delivery of products within a short and specific period of time | 141 (62.7) |

| Offering simple instructions on how to use purchased products and its side effects | 136 (60.4) |

| Direct delivery through pharmacy without using delivery companies, because their delivery conditions are not guaranteed | 137 (60.9) |

| Providing after-sales services, such as return and exchange services | 132 (58.7) |

| Free delivery of products, with no objection on having a minimum charge for delivery | 126 (56.0) |

| Having a licensed local warehouse for international pharmacies and deliver from these warehouses | 117 (52.0) |

| Providing medication refill service | 110 (48.9) |

| Providing the service of dispensing and delivering medicines prescribed by hospitals and medical centers | 107 (47.6) |

| Constantly updating information about the available medications in online pharmacy | 104 (46.2) |

| What products will you purchase from online pharmacies in the future?** | |

| Personal care and hygiene products (body, hair, oral health and shaving products) | 182 (80.9) |

| Dietary and herbal supplements and diet products (natural vitamins and minerals) | 155 (68.9) |

| Nonprescription medications (analgesics and antacids, etc.) | 129 (57.3) |

| Beauty care products (make-up, accessories and lenses) | 120 (53.3) |

| Medical equipment (blood pressure or blood glucose monitors, etc.) | 112 (49.8) |

| Baby care products (milk, baby food, nappies and changing supplies, etc.) | 98 (43.6) |

| Lifestyle medications (contraceptives and health boosters) | 78 (34.7) |

| Prescription medications (antibiotics, diabetic medication, chronic diseases and psychiatric medication, etc.) | 77 (34.2) |

These questions were asked to participants who have not purchased from OPs only (n = 225/487).

Selection of multiple options was allowed for this question.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the public awareness of OPs and assessed consumer experiences and satisfaction, along with opportunities and barriers for OPs in SA. Based on the results, approximately 89.3% of the participants were aware of the OPs, and more than half (60.2%) had previously purchased from OPs. Most respondents were satisfied with their experience and indicated that they would continue ordering from OPs, mainly because of the quality of the received products and delivery conditions. Time-saving aspect, availability of a variety of products, and opportunity to take advantage of available offers and discounts, as well as the ability to review other people’s experiences with products, were the main motivating factors for these consumers to purchase from OPs. In contrast, non-consumers’ main reasons for choosing not to purchase from OPs were their personal preference for visiting community pharmacies, concerns about privacy, and difficulty distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate OPs. Other factors included having difficulty communicating with pharmacists about their health condition and the suitability of products for their health condition, concerns about receiving counterfeit or ingenuine products, difficulties involving exchanges and returns, and difficulty communicating with customer support when encountering problems with their orders.

In Europe, the public attitude toward the online purchase of medications became slightly positive after the COVID-19 pandemic, and this positive attitude translated to an approximately 10% increase in purchases of medications and health products from OPs compared to pre-COVID-19 purchases. Despite the increase in purchases from OPs, most individuals prefer to purchase medications from community pharmacies (Fittler, Ambrus, et al., 2022). In South Korea, OPs were strictly prohibited, but the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated OPs implementation (Song and Lee, 2021). Compared to previous studies in SA, we observed a large increase in public awareness of the availability of OPs in SA. For example, a 2013 study that investigated the extent of OP use in SA found that only 23.1% of the participants were aware of this option, and only approximately 3% bought medicines online (Abanmy, 2017). Similarly, a study published in 2015 that examined how consumers in Riyadh (in the central region) perceived and knew about the use of OP services reported that most participants had not heard of OPs (83%), and only about 1% had purchased medicinal products through OPs (Alfahad et al., 2015). In 2021, another study evaluated public awareness of the availability of OPs in SA, consumers’ motivations and their perception of OPs, and found that although ordering medication from OPs was still not well-recognized or used by the Saudi population, public awareness of OPs had increased to 89% (Alwhaibi et al., 2021), representing a large increase compared with historical numbers. A study conducted in Europe showed that most respondents (92.8%) were aware that medicinal products can be purchased online (Fittler, Ambrus, et al., 2022). Our study found a comparable level of public awareness regarding the existence of OPs (89.3%). However, in contrast to earlier findings, more than 60% of those who were aware of OPs used them, mainly to order health-related products and less frequently to order medications (22.5%) or pharmaceutical/medical services (16.5%). This comparison with earlier research reveals that the use of OPs is growing in SA, and we expect this trend to continue further based on the participants’ perceptions of OPs. Therefore, stakeholders regulating or serving this market should focus on improving regulations as well as existing services while developing new services for their OPs. The Saudi Food and Drug Authority has introduced guidelines for ordering prescription drugs from international OPs. Although this regulation allows ordering OTC medications and health-related products without a prescription, it is necessary to provide a prescription to allow ordered prescription-only medications to be cleared by customs. However, ordering narcotic, psychiatric, or controlled medications from OPs is prohibited (Saudi Food and Drug Authority, 2017).

According to the current literature, the primary reasons for purchasing from OPs include convenience, lower cost, and availability of various products compared with community pharmacies (Agarwal and Bhardwaj, 2020, Alwhaibi et al., 2021, Ashames et al., 2019, Assi et al., 2016, Fittler et al., 2018, Fung et al., 2004, Jairoun et al., 2021, Long et al., 2022, Orizio et al., 2011, Yang et al., 2021). These findings from national and international studies are consistent with the results of our study. The most important motivating factors among our participants who purchased from OPs were saving time and effort as well as the availability of a variety of products at reduced cost when purchasing from OPs. Additionally, we found that OP customers liked to take advantage of free shipping on certain items and read reviews of other customers’ experiences on the products or services they were interested in purchasing. Moreover, studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed new opportunities for OPs, such as providing virtual follow-ups, counseling, and pharmaceutical care services by pharmacists, as well as dispensing electronic prescriptions and delivering medications (Ahmad et al., 2020, Ding et al., 2020). Unquestionably, the existence of OPs offers an opportunity to increase public access to medicines, medical devices, and health products, especially for those with limited access to community pharmacies (Miller et al., 2021).

The present study found that the most frequently ordered products were personal care products (73.3%), followed by herbal supplements (52.3%), cosmetics (38.9%), and OTC medications (22.5%). This finding is similar to the results of a previous study in SA, which indicated that the most frequently purchased products were herbal medicines, supplements, and cosmetics, followed by OTC medications (Alwhaibi et al., 2021). However, we found an increase in the purchase of OTC and prescription medications compared to the findings of previous studies. Previously, the products that participants wanted to see offered by the OPs were beauty and care products, vitamins and supplements, and diet and fitness products (Hussein, 2018). In another study conducted in SA, OTC medications and cosmetics were found to be the most ordered or wanted-to-order OP products (Abanmy, 2017). The differences in the most ordered products compared to previous studies reflect variations in the demographics of the participants and their needs. In a cross-sectional study conducted in the UAE in 2018 to assess the practice of purchasing medications from online sources, OTC medications were the most commonly purchased products from OPs (Ashames et al., 2019). A later study conducted in the UAE during the COVID-19 pandemic reported that herbal supplements were the most frequently purchased products from OPs (Jairoun et al., 2021), and the COVID-19 pandemic was the most likely reason for this finding.

The results of similar studies in other parts of the world differ somewhat from the findings in the Middle Eastern context. A 2004 US study identified medications for the management of chronic diseases as the most commonly purchased products (75%), followed by supplements for sexual performance and weight loss (Susannah, 2004). In contrast, our research revealed that only 10.7% of participants ordered prescription drugs from OPs. Although 64.4% of the participants who ordered prescription medications received counseling from a pharmacist (through the OP website or application via direct messaging, phone, or video calling), 20.3% of the medications lacked proper instructive labeling for patients (labels placed on medications that include patient-specific information and instructions). In addition, a recent systematic review revealed that prescription medications obtained from international OPs were incorrectly labeled or lacked leaflets, and the use of OP to order medications remained limited, with rates ranging from 2% to 13% (Long et al., 2022). In the US, in 2015, for more than half of a study’s participants, the most purchased items were cosmetics and personal care products, followed by lifestyle products used as mood stabilizers or for cognitive function enhancement. In contrast, products marketed for weight loss or sexual performance were ordered by approximately 20–30% of the respondents, while muscle enhancers were purchased by approximately 16% (Assi et al., 2016). According to a study conducted in Portugal, the products most purchased from OPs were cosmetics, OTC medications, and food supplements (Santos, 2021), in line with the consumer purchasing behavior in our study. Although most participants who purchased from OPs were aware of the availability of medical services, such as consultations with a doctor or pharmacist, few had used these services. Conceivably, this reluctance reflected the participants’ concern that they might not receive a quick response from a pharmacist.

Most consumers in SA were generally satisfied with OPs, they were mostly satisfied with the price, ease of comparison between products, and availability of certain branded medications; however, they found the reliability of OPs unsatisfactory (Agarwal and Bhardwaj, 2020). A comparison of patient satisfaction with services provided by OPs or community pharmacies revealed that OP customers had a higher level of satisfaction with prices than community pharmacy customers, whereas the latter had a higher level of satisfaction with counseling (Govender and Suleman, 2019). In studies conducted in SA to measure the satisfaction levels of those who purchased medicines or other products from OPs in 2013 and 2020, most participants exhibited high satisfaction levels (greater than80%) (Abanmy, 2017, Alwhaibi et al., 2021), and most of these customers were satisfied with the quality of the product received (Alwhaibi et al., 2021). Based on these results, the public perception of community pharmacies and pharmacists in SA revealed that 81% of the public had a positive perception of their pharmacists, 62% were satisfied with the performance of community pharmacists, and 65% were satisfied with the services provided by community pharmacies (Almohammed and Alsanea, 2021, El-Kholy et al., 2022). While previous research focused on overall consumer satisfaction, our findings highlight specific areas of satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Most participants who used OP services were satisfied with them, whereas most non-consumers stated that they would consider making future purchases from OPs if they had easy access to pharmacists and medical counseling services. Their responses suggested that people who lack experience with OPs are unaware of the services they offer. Overall, previous studies found that the four main barriers to ordering pharmaceutical products from OPs were the cost of delivery, delay in receiving the order, concerns about a lack of licensure for some marketed products, and delivery of damaged products or incomplete orders (Hussein, 2018). We identified similar concerns, along with other reasons, among respondents who did not purchase from OPs (Fig. 5).

One of the main issues facing the growth of the OP market, both locally and globally, is the lack of regulations and monitoring required to protect consumers and patients by ensuring the safety and quality of the products sold through OPs and the legitimacy of these pharmacies (Long et al., 2022). In addition, many counterfeit medications or ingenuine health products are available (Fittler et al., 2022b, Kumaran et al., 2020), which can impact public safety and trust in online resources over time. In the current study, many participants indicated that they had difficulty distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate OPs or were concerned about receiving counterfeit or ingenuine products. In addition, some participants had additional concerns about receiving non-halal products, particularly when purchasing products from international OPs. Therefore, the public needs national and international regulations to control this market as well as policies for OPs to operate safely. Many countries with good regulatory and quality assurance systems have a lower prevalence of substandard or counterfeit products than countries with poor regulatory systems (Al-Worafi et al., 2020, Attaran et al., 2011).

Future research should concentrate on the safety of products ordered from OPs, particularly international companies, as well as further explore the extent of the problem with counterfeit products from OPs. Researchers should also investigate the type of medications dispensed through OPs and the prescribing and dispensing processes, which are critical to health outcomes. Inappropriate or inadequate procedures could lead to the misuse of medications, especially if patients do not receive appropriate counseling. Another topic of interest for future studies are patients with chronic diseases as consumers who may benefit the most from such services.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. For example, most study participants were female and from the central region of SA, which may have affected the generalizability of the study because only a limited number of participants were included from other regions. The survey was distributed through a social media platform, which might have excluded those who were unfamiliar with the social media platform used or lacked access to it, which may have affected their knowledge of OPs and ordering processes. In addition, because the survey responses were self-reported, recall bias could not be ruled out. Finally, we did not inquire about the participants’ health conditions, which might have impacted their purchasing behavior and level of satisfaction with the OP services.

5. Conclusion

Our research confirmed the increasing public awareness of the existence of OPs in SA. Overall, while the customers of these OPs were satisfied with the services provided, there is room for improvement, such as enhancing the speed of delivery and providing medical consultation services. Personal care and hygiene products were the most popular items, followed by beauty products and OTC medications; most participants did not order prescribed medications, which might reflect either their unawareness of these services or their inability to upload prescriptions. In conclusion, there is still a need to increase public awareness of the existing services provided by OPs and the use efficiently because of the significant role these businesses currently play in reforming the healthcare system in SA.

6. Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study methods, questionnaires, and data acquisition procedures were reviewed and approved by the local ethics board (Ref. No. E-22–7131; Institutional Review Board, King Saud University Medical City). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written consent from the respondents was waived; electronic consent was used instead, and all participants’ identifiers were kept confidential throughout the study.

7. Consent for publication

Not applicable.

8. Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

9. Authors’ contributions

OAA and NOA conceptualized, designed, and supervised the study. OA analyzed the data, produced the tables and figures, and was a major contributor to writing the manuscript. RAA, FOG, RSA, and SKA collected the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author (OAA) received funding from the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia through project no. (IFKSUOR3–101–3), to support the publication of this manuscript. The funding agency played no role in designing the study, analyzing and interpreting the data, or writing the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Rana Aljadeed, Dr. Shiekha Alaujan, Dr. Raniah Aljadeed, and Dr. Huda Alewairdhi for the time and effort they spent reviewing the questionnaire, which helped us improve the survey. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia, for funding this research through project no. (IFKSUOR3–101–3).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.06.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abanmy N. The extent of use of online pharmacies in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2017;25(6):891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu Bakar A., Ong S., Chuo Yew S.T., Ooi G.S., Hassali M. Barriers for implementation of e-pharmacy policy: views of pharmacy authorities, public institutions and societal groups. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2022;30:41–56. doi: 10.47836//pjssh.30.1.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S., Bhardwaj G. A study of consumer buying behaviour towards E-pharmacies in Delhi. Int J Forensic Engineering. 2020;4(4):17–19. doi: 10.1504/IJFE.2020.10037772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A., Alkharfy K.M., Alrabiah Z., Alhossan A. Saudi Arabia, pharmacists and COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020;13(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfahad N., Albelali M., Khurshid F., Al-Arifi M., Al-Dhawailie A., Alsultan M. Perception and knowledge to online pharmacy services among consumers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a pilot survey. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2015;34:1113–1118. http://www.latamjpharm.org/resumenes/34/6/LAJOP_34_6_1_10.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Almohammed O.A., Alsanea S. Public perception and attitude toward community pharmacists in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Health Systems Research. 2021;1(2):67–74. doi: 10.1159/000515207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alwhaibi M., Asser W.M., Al Aloola N.A., Alsalem N., Almomen A., Alhawassi T.M. Evaluating the frequency, consumers' motivation and perception of online medicinal, herbal, and health products purchase safety in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2021;29(2):166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Worafi Y., Alseragi W., Ming L.C., Alakhali K. Drug safety in China. In. 2020:381–388. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-819837-7.00028-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashames A., Bhandare R., Zain AlAbdin S., Alhalabi T., Jassem F. Public perception toward e-commerce of medicines and comparative pharmaceutical quality assessment study of two different products of furosemide tablets from community and illicit online pharmacies. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2019;11(3):284–291. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_66_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assi S., Thomas J., Haffar M., Osselton D. Exploring consumer and patient knowledge, behavior, and attitude toward medicinal and lifestyle products purchased from the internet: a web-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(2):e34. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attaran A., Bate R., Kendall M. Why and how to make an international crime of medicine counterfeiting. Journal of International Criminal Justice. 2011;9 doi: 10.1093/jicj/mqr005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., She Q., Chen F., Chen Z., Jiang M., Huang H., Li Y., Liao C. The internet hospital plus drug delivery platform for health management during the COVID-19 pandemic: observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e19678. doi: 10.2196/19678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kholy A.A., Abdelaal K., Alqhtani H., Abdel-Wahab B.A., Abdel-Latif M.M.M. Publics' perceptions of community pharmacists and satisfaction with pharmacy services in Al-Madinah city, Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58(3) doi: 10.3390/medicina58030432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham J.E. Negative consequences of the widespread and inappropriate easy access to purchasing prescription medications on the internet. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2021;14(1):22–28. https://www.ahdbonline.com/issues/2021/march-2021-vol-14-no-1/3086-negative-consequences-of-the-widespread-and-inappropriate-easy-access-to-purchasing-prescription-medications-on-the-internet [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fittler A., Vida R.G., Káplár M., Botz L. Consumers turning to the internet pharmacy market: cross-sectional study on the frequency and attitudes of Hungarian patients purchasing medications online. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(8):e11115. doi: 10.2196/11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fittler A., Ambrus T., Serefko A., Smejkalová L., Kijewska A., Szopa A., Káplár M. Attitudes and behaviors regarding online pharmacies in the aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic: At the tipping point towards the new normal. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1070473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fittler A., Paczolai P., Ashraf A.R., Pourhashemi A., Iványi P. Prevalence of poisoned Google search results of erectile dysfunction medications redirecting to illegal internet pharmacies: data analysis study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e38957. doi: 10.2196/38957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung C.H., Woo H.E., Asch S.M. Controversies and legal issues of prescribing and dispensing medications using the Internet. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(2):188–194. doi: 10.4065/79.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govender N., Suleman F. Comparison of patient satisfaction with pharmaceutical services of postal pharmacy and community pharmacy. Health SA. 2019;24:1105. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v24i0.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein R., Almohammadi A.A., Alweldi W.M., Alshik A.M., Malik S., Mashat A. Trends and issues of online pharmacies in Saudi Arabia. IADIS International Conference. 2018 https://www.iadisportal.org/digital-library/trends-and-issues-of-online-pharmacies-in-saudi-arabia [Google Scholar]

- Jairoun A.A., Al-Hemyari S.S., Abdulla N.M., El-Dahiyat F., Jairoun M., Al-Tamimi S.K., Babar Z.U. Online medication purchasing during the Covid-19 pandemic: potential risks to patient safety and the urgent need to develop more rigorous controls for purchasing online medications, a pilot study from the United Arab Emirates. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s40545-021-00320-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran H., Long C.S., Bakrin F.S., Tan C.S., Goh K.W., Al-Worafi Y.M., Lee K.S., Lua P.L., Ming L.C. Online pharmacies: desirable characteristics and regulations. Drugs & Therapy Perspectives. 2020;36(6):243–245. doi: 10.1007/s40267-020-00727-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long C.S., Kumaran H., Goh K.W., Bakrin F.S., Ming L.C., Rehman I.U., Dhaliwal J.S., Hadi M.A., Sim Y.W., Tan C.S. Online pharmacies selling prescription drugs: systematic review. Pharmacy (Basel) 2022;10(2) doi: 10.3390/pharmacy10020042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R., Wafula F., Onoka C.A., Saligram P., Musiega A., Ogira D., Okpani I., Ejughemre U., Murthy S., Garimella S., Sanderson M., Ettelt S., Allen P., Nambiar D., Salam A., Kweyu E., Hanson K., Goodman C. When technology precedes regulation: the challenges and opportunities of e-pharmacy in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(5):e005405. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orizio G., Merla A., Schulz P.J., Gelatti U. Quality of online pharmacies and websites selling prescription drugs: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e74. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa S., Billings J., Sun Y., Yu S., Penley B. COVID-19 treatments sold online without prescription requirements in the united states: cross-sectional study evaluating availability, safety and marketing of medications. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e27704. doi: 10.2196/27704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, E. O., 2021. Exploring the factors that influence the adoption of online pharmacy in Portugal: a study on consumeŕs acceptance and pharmacist́s perception. https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/139908/2/533380.pdf.

- Saudi Food and Drug Authority, 2017. Conditions and requirements for the clearance or exportation of individuals for personal use. https://www.sfda.gov.sa/en/regulations/78612.

- Singh H., Majumdar A., Malviya N. E-pharmacy impacts on society and pharma sector in economical pandemic situation: A review. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics. 2020;10:335–340. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v10i3-s.4122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song H.S., Lee B.M. The viability of online pharmacies in COVID-19 era in Korea. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021;11(9):1977–1980. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susannah, F., 2004. Prescription drugs online. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2004/10/10/prescription-drugs-online/.

- Yang L.Y., Lyons J.G., Erickson S.R., Wu C.H. Trends and characteristics of the US adult population's behavioral patterns in web-based prescription filling: national survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e23662. doi: 10.2196/23662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.