Abstract

Wild barley, from “Evolution Canyon (EC)” in Mount Carmel, Israel, are ideal models for cereal chromosome evolution studies. Here, the wild barley EC_S1 is from the south slope with higher daily temperatures and drought, while EC_N1 is from the north slope with a cooler climate and higher relative humidity, which results in a differentiated selection due to contrasting environments. We assembled a 5.03 Gb genome with contig N50 of 3.53 Mb for wild barley EC_S1 and a 5.05 Gb genome with contig N50 of 3.45 Mb for EC_N1 using 145 Gb and 160.0 Gb Illumina sequencing data, 295.6 Gb and 285.35 Gb Nanopore sequencing data and 555.1 Gb and 514.5 Gb Hi-C sequencing data, respectively. BUSCOs and CEGMA evaluation suggested highly complete assemblies. Using full-length transcriptome data, we predicted 39,179 and 38,373 high-confidence genes in EC_S1 and EC_N1, in which 93.6% and 95.2% were functionally annotated, respectively. We annotated repetitive elements and non-coding RNAs. These two wild barley genome assemblies will provide a rich gene pool for domesticated barley.

Subject terms: Plant ecology, Plant evolution

Background & Summary

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), the fourth largest crop in terms of total cultivated area worldwide, is one of the earliest domesticated crops1. The cultivated barley is believed to be domesticated about 10,000 years ago from the wild progenitor H. spontaneum2. Beyond its importance as a major global crop, barley also serves as an invaluable model organism for research into crop domestication and adaptability due to its diploid status, relatively small genome within the Triticeae, and broad environmental adaptability3,4. A growing body of research highlights that during domestication, barley’s agronomic traits were selectively enhanced for efficient harvesting, maximized yield, and improved grain quality. In contrast, genetic variations crucial for survival under environmental stresses have been diminished or even eradicated5, posing significant challenges when breeding new resilient varieties in response to climate and environmental shifts., Wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum K. Koch), the ancestor of cultivated barley, has a wide eco-geographic distribution across highly diverse environments throughout Southwestern Asia6. The capacity of wild barley to withstand dry and hot conditions has significant implications for barley breeding, especially considering that a mere 40% of alleles present in wild barley are found within the gene pool of globally cultivated barley7,8. The wild barley population, therefore, can contribute a rich reservoir of genes tolerant to drought and heat, which can be introduced into domesticated barley - a feat made possible by the ease with which the two species can crossbreed. This paves the way for breeding cultivars resilient to climate change.

High-quality genome assembly is required for the exploitation of beneficial genetic variants in the wild barley1,8. With the advancements in sequencing technology, notable strides have been made in barley genomics. The draft sequence assembly of barley cultivar (cv.) Morex was reported in 2012, and it was further improved in 2017, especially in the centromeric region and highly repetitive region7,9, and again with significant improvement in continuity in 202110. Besides, the draft genome and high-quality reference genome of Tibetan hulless barley have been publicly available in 2018, which significantly enriched barley genomic resources8,11. Recently, a barley pan-genome study reported the de novo assemblies for 20 representative barley worldwide accessions and revealed abundant structural variations among the genomes12, which underscore the need for high-quality wild barley assemblies in comparative genomic studies and future barley breeding initiatives.

The ‘Evolution Canyon’ model serves as an optimal micro-climatic divergence model between slopes, designed to understand the impact of climate and environmental changes on genomic adaptation and differentiation13. The sharp microclimatic divergence between the abutting slopes has been proposed to drive genomic adaptive divergence underpinnings of local adaptation, providing a unique system for comparative genomic study. High-quality genome assemblies of wild barley from micro-climatically contrasting sites can enrich the barley genome resources and provide genomic insight into the relationship between environmental selection and genome evolution. Here, we report two chromosome-scale assemblies for two wild barleys (EC_S1 from the south slope, EC_N1 from the north slope of Evolution Canyon in Mountains of Carmel, Israel), using the Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing method, Hi-C chromosome conformation capture and Bionano-optical mapping technologies. With BUSCO, CEGMAG and GC-depth analysis, we demonstrate that the two assemblies are of high integrity and accuracy. Using the assemblies, we further predicted their genes, repetitive elements, and non-coding RNAs. The wild barley can provide a rich gene pool for stress-tolerant genes that might be introduced into domesticated barley, and our wild barley genomes will greatly facilitate such endeavours. The wild barley assemblies will also enable comparative genomic studies penetrating genomic evolution and adaptation of barley.

Methods

Sample preparation, library construction and sequencing

Seeds were collected from two samples, EC-S1 and EC-N1, at the South-facing slope and north-facing slope, respectively, of the “Evolution Canyon” in Mount Carmel, Israel, and were germinated and grown in the glasshouse at Yangtze University (Jingzhou, Hubei Province, China). Mature leaves were harvested for DNA extraction and sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted following the CTAB method and purified with QIAGEN® Genomic kit (Cat#13343, QIAGEN, Germany). DNA quality and concentration were examined using a NanoDropTM 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). DNA concentration was estimated with a Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

For long-read sequencing, approximately 3–4 µg DNA per sample was used as input material for the ONT library preparations. After the sample was qualified, size-select of long DNA fragments was performed using the PippinHT system (Sage Science, USA). Next, the ends of DNA fragments were repaired, and A-ligation reactions were conducted with NEBNext Ultra II End Repair/dA-tailing Kit (Cat# E7546). The adapter in the SQK-LSK109 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) was used for further ligation reaction, and DNA library was measured by Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). About 700 ng DNA library was constructed and performed on a Nanopore PromethION sequencer instrument (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) at the Genome Center of Grandomics (Wuhan, China).

A total of 295.6 Gb (~65× coverage of the estimated genome size) subreads in EC_S1 and 285.35 Gb (~65× coverage of the estimated genome size) subreads in EC_N1 were yielded for genome assembly. For the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform, libraries for Illumina paired-end genome sequencing were constructed using Truseq Nano DNA HT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina USA) following the standard manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina), and then sequenced with a paired-end sequencing strategy. Finally, we obtained 145.0 Gb (~32× coverage of the estimated genome size) in EC_S1 and 160.0 Gb (~36X coverage of the estimated genome size) clean data after quality inspection. For High-through chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) sequencing, genomic DNA was extracted from the EC_S1 and EC_N1 sample. Thereafter, we constructed the Hi-C library and obtained sequencing data via the Illumina Novaseq/MGI-2000 platform to anchor hybrid scaffolds onto chromosome14. After quality control and filtration, 555.1 Gb (~122× coverage of the estimated genome size) clean data in EC_S1 and 514.5 Gb clean data in EC_N1 were obtained for the next analysis. Samples of roots and leaves (and young panicle) at the seedling, tillering and booting stage were used to collect transcriptome data by RNA sequencing for predicting the gene model.

Total RNA was extracted by grinding tissue in TRIzol reagent (TIANGEN, China) on dry ice and processed following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The integrity of the RNA was determined with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and agarose gel electrophoresis. The purity and concentration of the RNA were determined with the NanodropTM 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). cDNAs were prepared with DNA damage repair, end repair, and sequencing adapters ligation using SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 (Pacific Biosciences). The SMRTbell template was annealed to the sequencing primer, bound to polymerase, and sequenced on the PacBio Sequel platform using Sequel Binding Kit 3.0 (Pacific Biosciences) with 20 h movies. Finally, a total of 168.9 Gb clean data in EC_S1 and 111.8 Gb clean data in EC_N1 with filtration was yielded for further analysis.

For BioNano physical mapping, DNA extracted from EC_S1 and EC_N1 were subject to manufacturer-recommended protocols for library preparation (Plant DNA Isolation Kit,80003) and optical scanning provided by BioNano Genomics (https://bionanogenomics.com), with the labeling enzyme Direct Label Enzyme (DLE) (Bionano PrepDLS Labeling DNA Kit,80005). Labelled DNA samples were loaded and run on the Saphyr system (BioNano Genomics). Raw BioNano data were cleaned by removing molecules matching any of the following rules: length less than 150 kb, molecule signal-to-noise ratio less than 2.75, label signal-to-noise ratio less than 2.75, or label intensity greater 0.8. About 443.19 Gb and 311.01 Gb clean data were yielded after filtering with the parameter “Molecule length <150 kb” and “MinSites (/100 kb) <9”.

De novo assembly of the wild barley genome

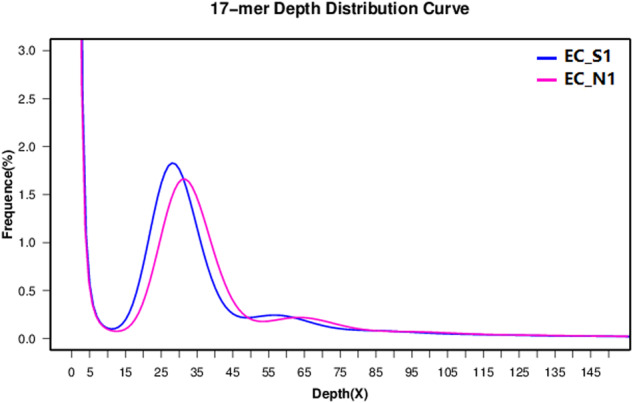

To ensure reads are reliable, Illumina paired-ended sequenced raw reads for the genomic survey were first filtered using the Fastp v.0.20.015 preprocessor (set to default parameters). To understand the genomic characteristics of EC_S1 and EC_N1, the K-mer analysis16 was performed using Illumina DNA data prior to genome assembly to estimate the genome size and heterozygosity. Briefly, quality-filtered reads were subjected to 17-mer frequency distribution analysis using the Jellyfish program16. The genome size was determined based on k-mer frequency distributions, using details from the peak depth and the count of 17-mers. Likewise, the heterozygosity rate was estimated utilizing the count of k-mers at half the peak depth and through simulation analysis using A. thaliana genome data as described in a previous publication17. The results indicated that the estimated genome sizes of EC_S1 and EC_N1 were 4.56 Gb and 4.40 Gb, respectively, both displaying low heterozygosity. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The k-mer distribution used to estimate the genome size of the wild barley EC_S1 and EC_N1. The distribution was determined based on the Jellyfish analysis using a k-mer size of 17.

For de novo genome assembly, an ONT-only assembly was constructed by using an OLC (overlap layout-consensus)18/string graph method19 with NextDenovo. Considering the high error rate of ONT raw reads, the original subreads were first self-corrected using NextCorrect, thus obtaining 190.0 Gb (~38X coverage of the estimated genome size) and 172.8 Gb (~39× coverage of the estimated genome size) consistent sequences (CNS reads) in EC_S1 and EC_N1, respectively. Comparing CNS was then performed with the NextGraph module to capture correlations of CNS. Based on the correlation of CNS, 4.66 Gb preliminary genome with a contig N50 length of 3.26 Mb in EC_S1 and 4.66 Gb preliminary genome with a contig N50 length of 3.17 Mb in EC_N1 were obtained (Table 1). To improve the accuracy of the assembly, we refine the contigs with Racon20 using ONT long reads and Nextpolish using Illumina short reads with default parameters. Finally, we obtained a polish genome of 5.03 Gb with a contig N50 length of 3.53 Mb in EC_S1 and 5.05 Gb with a contig N50 length of 3.45 Mb in EC_N1 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Statistics of EC_S1 and EC_N1 preliminary genome assembly.

| Stat Type | EC_S1 | EC_N1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig Length(bp) | Contig Number | Contig Length(bp) | Contig Number | |

| N50 | 3,264,181 | 421 | 3,171,294 | 429 |

| N60 | 2,617,547 | 580 | 2,530,446 | 593 |

| N70 | 1,943,493 | 787 | 1,924,359 | 806 |

| N80 | 1,285,538 | 1,079 | 1,275,833 | 1,102 |

| N90 | 715,201 | 1,562 | 717,612 | 1,590 |

| Longest | 18,405,770 | 1 | 21,572,244 | 1 |

| Total | 4,656,798,638 | 2,593 | 4,659,696,944 | 2,628 |

| Length > = 1 kb | 4,656,798,638 | 2,593 | 4,659,696,944 | 2,628 |

| Length > = 2 kb | 4,656,798,638 | 2,593 | 4,659,696,944 | 2,628 |

| Length > = 5 kb | 4,656,798,638 | 2,593 | 4,659,696,944 | 2,628 |

Table 2.

Statistics of the EC_S1 and EC_N1 polished genome assembly.

| Parameter | EC_S1 | EC_N1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contig Length (bp) | Contig Number (#) | Contig Length (bp) | Contig Number (#) | |

| N50 | 3,525,661 | 421 | 3,451,742 | 428 |

| N60 | 2,827,275 | 579 | 2,752,099 | 592 |

| N70 | 2,095,788 | 786 | 2,087,500 | 805 |

| N80 | 1,389,397 | 1,078 | 1,385,479 | 1,100 |

| N90 | 771,157 | 1,560 | 777,785 | 1,587 |

| Longest | 19,859,128 | 1 | 23,442,753 | 1 |

| Total | 5,025,137,494 | 2,593 | 5,052,015,165 | 2,628 |

| Length > = 1 kb | 5,025,137,494 | 2,593 | 5,052,015,165 | 2,628 |

| Length > = 2 kb | 5,025,137,494 | 2,593 | 5,052,015,165 | 2,628 |

| Length > = 5 kb | 5,025,137,494 | 2,593 | 5,052,015,165 | 2,628 |

The completeness of genome assembly was assessed using BUSCO v4.0.5 with single copy homologous genes in embryophyta_odb10 of OrthoDB database (Benchmarking Universal Single Copy Orthologs)21 and CEGMA v2 (Core Eukaryotic Gene Mapping Approach)22. 96.2% and 96.3% of complete BUSCOs were found in EC_S1 and EC_N1, respectively (Fig. S1). In addition, a total of 98.39% core genes in EC_S1 and 97.18% core genes in EC_N1 were detected among 248 core gene collections, suggesting high confidence in genome assembly in both EC_S1 and EC_N1 (Fig. S2). To evaluate the consistency of genome sequence, we aligned the second-generation sequencing data and the third-generation sequencing data to the polish genome by bwa v0.7.12-r103923 and minimap2 vr4124. The results showed that the average depth of the second-generation sequencing data in the EC_ S1 and EC_ N1 was 28.22 and 31.22, respectively, and the coverage (depth > = 1×) was 85.97 and 84.88%. The average depth of the third-generation sequencing data in EC_ S1 and EC_ N1 was 55.12 and 43.83, respectively, and the coverage (depth > = 1×) was 99.80 and 99.62% (Table 3). GC-depth analysis showed that the GC content was distributed in 40%–50%, and the sequencing depth was concentrated in 40–80× in both EC_ S1 and EC_ N1 assemblies (Fig. S3). The corrected genome sequence was compared with NT library (Nucleotide Sequence Database, downloaded on 3rd August 2018, https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/FASTA/nt.gz) to determine the classification of the sequence, suggesting that there was a small amount of mitochondrial and chloroplast nucleic acids in the sequence but no exogenous pollution (Table 4).

Table 3.

Genome sequence consistency and coverage.

| Total Reads | Map Reads | Map Rate (%) | Average depth (X) | Coverage (Depth = 1X) (%) | Single nucleotide accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 971,244,971 | 969,319,898 | 99.8 | 28.22 | 85.97 | 99.997 |

| 1,071,625,423 | 1,069,602,506 | 99.81 | 31.22 | 84.88 | 99.996 |

| 18,481,260 | 18,474,324 | 99.96 | 55.12 | 99.8 | — |

| 11,802,366 | 11,798,906 | 99.97 | 43.83 | 99.62 | — |

Table 4.

Genomic contamination assessment of EC_S1 and EC_N1 assemblies.

| Assembly | Type | Contig Number | Contig Number ratio (%) | Contig Length (bp) | Contig Length ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC_S1 | Viridiplantae | 2,591 | 99.92 | 5,024,174,262 | 99.98 |

| Mitochondrion/Chloroplast | 1 | 0.04 | 603,539 | 0.01 | |

| Nohit | 1 | 0.04 | 359,693 | 0.01 | |

| Total | 2,593 | 100 | 5,025,137,494 | 100 | |

| EC_N1 | Viridiplantae | 2,626 | 99.92 | 5,050,254,425 | 99.97 |

| Mitochondrion/Chloroplast | 2 | 0.08 | 1,760,740 | 0.03 | |

| Nohit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 2,628 | 100 | 5,052,015,165 | 100 |

Chromosome assembly by optical mapping and Hi-C data

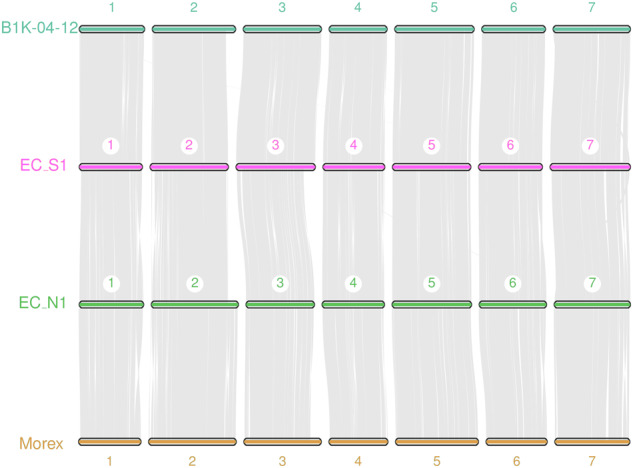

De novo assembly of BioNano molecules into genome maps was performed using the script pipelineCL.py in the BioNano Solve package v3.3 (BioNano Genomics). Hybrid scaffolds were assembled from ONT assembly and BioNano genome maps using the script hybridScaffold.pl in the Solve package. Finally, EC_S1’s genome super-scaffold size was 5.1 Gb with a scaffold N50 of 90.4 Mb and contig N50 of 1.67 Mb; EC_N1’s genome super-scaffold size was 5.2 Gb with scaffold N50 of 43.7 Mb and contig N50 of 1.59 Mb (Table 5). Compared to previously published barley genome assemblies, current genomes assemblies showed a great improvement in contig N50 and scaffold N50 (Table S1), and their quality was closed to the new version genome of Morex assembled by PacBio long-read (Table S2)1,12. For Hi-C auxiliary assembly, a total of 3.83 billion paired-end reads were generated from the libraries of EC_S1 and 3.54 billion from EC_N1. Then, quality controlling of Hi-C raw data was performed using HiC-Pro25 as in previous research. Firstly, low-quality sequences (quality scores < 20), adaptor sequences and sequences shorter than 30 bp were filtered out using Fastp15. The clean paired-end reads were then mapped to the draft assembled sequence using bowtie2 v2.3.226 to get 759 million (39.63%) unique mapped paired-end reads in EC_S1 and 581 million (33.81%) in EC_N1. About 586 million (30.62%) valid interaction paired reads in EC_S1 and 436 million in EC_N1 were identified and retained by HiC-Pro25 from unique mapped paired-end reads for further analysis (Table 6). Invalid read pairs, including dangling-end, self-cycle, re-ligation, and dumped products, were filtered by HiC-Pro25. The 5.07 Gb scaffolds (98.58%) in EC_S1 and 5.10 Gb scaffolds (97.16%) in EC_N1 were further clustered, ordered, and oriented scaffolds onto the seven chromosomes by LACHESIS27, respectively (Table 7). According to the resulting Hi-C contact heatmap, mis-assemblies and mis-joins were manually corrected based on neighbouring interactions. The final assemblies were aligned to the previously reported barley genome assemblies of wild barley B1K-04–12 and cultivated barley Morex12 by Mummer v4.028. Then the raw alignments results were further filtered by delta-filter from Mummer software28. The results were visualized by NGenomeSyn v2.029, which demonstrated high collinearity across the majority of all chromosome regions. Furthermore, we identified abundant structural variations (SVs), including large fragment inversions (INVs) and insertions or deletions (INDELs) (refer to Fig. 2 and Fig. S4). These findings enrich the diversity of the barley genome resource.

Table 5.

Statistics of scaffold constructed by BioNano in EC_S1 and EC_N1.

| Samples | Stat Type | Scaffold Length (bp) | Scaffold Number (#) | Contig Length (bp) | Contig Number (#) | Gap Length (bp) | Gap Number (#) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC_S1 | N50 | 90,435,441 | 15 | 1,673,488 | 843 | 173,720 | 127 |

| N60 | 66,240,192 | 21 | 1,259,474 | 1,189 | 140,328 | 181 | |

| N70 | 36,446,783 | 31 | 928,307 | 1,655 | 104,275 | 251 | |

| N80 | 16,660,035 | 51 | 613,754 | 2,320 | 75,432 | 347 | |

| N90 | 547,941 | 292 | 375,970 | 3,365 | 46,368 | 487 | |

| Longest | 275,161,632 | 1 | 9,363,529 | 1 | 1,469,128 | 1 | |

| Total | 5,110,963,655 | 3,671 | 5,025,137,494 | 6,981 | 85,826,161 | 3,310 | |

| Length > = 1 kb | 5,110,951,505 | 3,581 | 5,025,125,344 | 6,891 | 85,784,138 | 878 | |

| Length > = 2 kb | 5,110,917,100 | 3,558 | 5,025,090,939 | 6,868 | 85,771,526 | 870 | |

| Length > = 5 kb | 5,110,584,325 | 3,464 | 5,024,758,164 | 6,774 | 85,642,946 | 830 | |

| EC_N1 | N50 | 43,706,098 | 29 | 1,588,206 | 905 | 970,159 | 36 |

| N60 | 24,896,804 | 45 | 1,191,192 | 1,272 | 407,276 | 64 | |

| N70 | 14,063,939 | 74 | 850,038 | 1,773 | 226,986 | 119 | |

| N80 | 5,480,950 | 134 | 576,932 | 2,499 | 142,755 | 212 | |

| N90 | 518,178 | 509 | 352,017 | 3,618 | 75,821 | 372 | |

| Longest | 238,728,233 | 1 | 12,370,996 | 1 | 7,555,966 | 1 | |

| Total | 5,219,379,810 | 4,132 | 5,052,015,165 | 7,489 | 167,364,645 | 3,357 | |

| Length > = 1 kb | 5,219,364,283 | 4,036 | 5,051,999,638 | 7,393 | 167,326,492 | 897 | |

| Length > = 2 kb | 5,219,325,547 | 4,012 | 5,051,960,902 | 7,369 | 167,312,956 | 888 | |

| Length > = 5 kb | 5,218,959,372 | 3,908 | 5,051,594,727 | 7,265 | 167,164,119 | 847 |

Table 6.

Valid paired end reads statistics of Hi-C data.

| Sample | EC_S1 | EC_N1 |

|---|---|---|

| Unique Mapped Paired-end Reads | 759,088,187 | 581,279,660 |

| Dangling End Paired-end Reads | 31,922,666 | 24,560,096 |

| Self Circle Paired-end Reads | 3,807,620 | 2,591,099 |

| Dumped Paired-end Reads | 132,876,819 | 113,956,204 |

| Valid Paired-end Reads | 586,484,335 | 436,245,999 |

| Valid Rate (%) | 77 | 75.05 |

| Vailded reads of unique mapping(%) | 31 | 25.38 |

Table 7.

Chromosome length assembled by Hi-C data in EC_S1 and EC_N1.

| Chromosome | EC_S1 | EC_N1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | Scaffold Number (#) | Size (bp) | Scaffold Number (#) | |

| LG01 (Chr2H) | 701,205,537 | 58 | 718,190,815 | 83 |

| LG02 (Chr7H) | 679,094,545 | 57 | 654,994,973 | 86 |

| LG03 (Chr3H) | 675,898,809 | 47 | 610,452,210 | 114 |

| LG04 (Chr4H) | 668,531,449 | 95 | 584,827,964 | 89 |

| LG05 (Chr5H) | 632,171,286 | 50 | 572,391,443 | 39 |

| LG06 (Chr6H) | 612,997,366 | 54 | 560,827,502 | 91 |

| LG07 (Chr1H) | 554,163,281 | 23 | 349,920,086 | 22 |

| Total | 4,524,062,273 | 384 | 4,051,604,993 | 524 |

Fig. 2.

The collinearity analysis among assemblies of EC_S1, EC_N1, B1K-04–12 and Morex.

Gene model prediction and functional annotation

We first annotated the tandem repeats using the software GMATA30 and Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF)31, where GMATA identifies the simple repeats sequences (SSRs) and TRF recognizes all tandem repeat elements in the whole genome. Transposable elements (TE) in the EC_S1 and EC_N1 genomes were then identified using a combination of ab initio and homology-based methods. For further identification of the repeats throughout the genome, RepeatMasker v2.0.132 was applied to search for known and novel TEs by mapping sequences against the de novo repeat library and Repbase TE library (version 20180826)33. Overlapping transposable elements belonging to the same repeat class were collated and combined. The repeat elements were annotated and shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Characterization of wild barley TE annotation in wild barley EC_S1 and EC_N1.

| Class | Order | Super family | EC_S1 | EC_N1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of elements | Length of sequence (bp) | Percentage of sequence (%) | Number of elements | Length of sequence (bp) | Percentage of sequence (%) | |||

| Class I | tatal | 4,978,332 | 4,068,129,400 | 79.6 | 4,723,019 | 4,070,454,371 | 77.99 | |

| LTR | total | 4,687,283 | 3,961,835,992 | 77.52 | 4,451,964 | 3,967,760,212 | 76.02 | |

| Unknown | 2,028,714 | 1,258,880,928 | 24.63 | 1,935,231 | 1,222,171,928 | 23.42 | ||

| Copia | 719,996 | 837,900,974 | 16.39 | 650,395 | 794,223,165 | 15.22 | ||

| Gypsy | 1,930,780 | 1,853,447,741 | 36.26 | 1,855,837 | 1,946,140,147 | 37.29 | ||

| Ngaro | 5,420 | 10,505,226 | 0.21 | |||||

| Other | 2,373 | 1,101,123 | 0.02 | 10,501 | 5,224,972 | 0.1 | ||

| LINE | total | 226,254 | 99,136,722 | 1.94 | 242,326 | 99,764,545 | 1.91 | |

| Unknown | 144,737 | 36,996,261 | 0.72 | 156,002 | 39,317,430 | 0.75 | ||

| L1 | 77,807 | 60,197,197 | 1.18 | 82,685 | 58,346,236 | 1.12 | ||

| Other | 3,710 | 1,943,264 | 0.04 | 3,639 | 2,100,879 | 0.04 | ||

| SINE | total | 64,795 | 7,156,686 | 0.14 | 28,729 | 2,929,614 | 0.06 | |

| Unknown | 64,665 | 7,150,037 | 0.14 | |||||

| Other | 130 | 6,649 | 0 | 28,729 | 2,929,614 | 0.06 | ||

| Class II | total | 994,800 | 390,247,909 | 7.64 | 1,067,975 | 416,959,633 | 7.99 | |

| DNA | total | 869,197 | 365,992,210 | 7.16 | 930,184 | 389,472,730 | 7.46 | |

| Unknown | 413,075 | 97,864,858 | 1.91 | 486,434 | 100,295,321 | 1.92 | ||

| CMC-EnSpm | 332,344 | 230,347,500 | 4.51 | 318,045 | 249,528,462 | 4.78 | ||

| MULE-MuDR | 36,509 | 16,457,049 | 0.32 | 36,575 | 17,892,859 | 0.34 | ||

| PIF-Harbinger | 35,961 | 12,689,209 | 0.25 | 34,867 | 12,358,068 | 0.24 | ||

| Other | 51,308 | 8,633,594 | 0.17 | 54,263 | 9,398,020 | 0.18 | ||

| RC | Other | 26,312 | 5,377,294 | 0.11 | 15,817 | 2,125,122 | 0.04 | |

| Total TEs | 5,973,132 | 4,458,377,309 | 87.23 | 5,790,994 | 4,487,414,004 | 85.98 | ||

| Tandem Repeats | total | 169,508 | 11,650,363 | 0.23 | 170,835 | 11,744,363 | 0.23 | |

| SSR | 68,608 | 826,702 | 0.02 | 71,838 | 864,442 | 0.02 | ||

| tandem_repeat | 100,900 | 10,823,661 | 0.21 | 98,997 | 10,879,921 | 0.21 | ||

| Unknown | 322,655 | 68,422,508 | 1.34 | 307,877 | 56,497,367 | 1.08 | ||

| Simple repeats | 17,136 | 4,940,437 | 0.1 | 17,083 | 4,370,082 | 0.08 | ||

| Other | 54,300 | 11,252,823 | 0.22 | 11,779 | 1,365,226 | 0.03 | ||

| Low complexity | 3,462 | 634,097 | 0.01 | 4,904 | 667,464 | 0.01 | ||

| Total Repeats | 6,540,193 | 4,555,277,537 | 89.13 | 6,303,472 | 4,562,058,506 | 87.41 | ||

Three independent approaches, including ab initio prediction, homology search, and reference guided transcriptome assembly, were used for gene prediction in a repeat-masked genome34. In detail, GeMoMa v1.3.135 was used to align the homologous protein sequences from related species to the assembly and then got the gene structure information, which was homolog prediction. For RNA-seq based gene prediction, filtered mRNA-seq reads were aligned to the reference genome using STAR (default)36. The transcripts were then assembled using Stringtie v2.1.437 and open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments (PASA)38. For the de novo prediction, RNA-seq reads were de novo assembled using Stringtie and analyzed with PASA to produce a training set. Augustus v2.5.539 with default parameters was then utilized for ab initio gene prediction with the training set. Finally, EVidenceModeler (EVM)40 was used to produce an integrated gene set of which genes with TE were removed using Transposon PSI package41 and the miscoded genes were further filtered. According to Mascher et al.7, high-confidence (HC) gene was defined as genes that had a significant BLAST hit to reference proteins and representative proteins had a similarity to the respective template sequence above a threshold which was determined on the basis of the origin of template sequences (>60% for Arabidopsis thaliana, sorghum and rice, >65% for Brachypodium distachyon, and >85% for barley). Finally, a total of 39,179 high-confidence and 20,936 low-confidence protein-coding genes were identified in EC_S1 genome, and 38,373 high-confidence and 20,243 low-confidence protein-coding genes in EC_N1 (Table 9).

Table 9.

The summary of gene annotation in the EC_S1 and EC_N1 assemblies.

| Annotation | Methods | EC_S1 | EC_N1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (#) | Percentage (%) | Number (#) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Structure annotation | De novo | 67,693 | 112.61 | 64,389 | 109.85 |

| Homology | 47,152 | 78.44 | 47604 | 81.21 | |

| RNA-seq | 21,019 | 34.96 | 20026 | 34.16 | |

| High-confidence | 39,179 | 65.17 | 38373 | 65.47 | |

| Low-confidence | 20936 | 34.83 | 20243 | 34.53 | |

| Total | 60,115 | 100 | 58616 | 100 | |

| Functional annotation | KOG | 23,722 | 39.46 | 23,687 | 40.41 |

| KEGG | 16,549 | 27.53 | 16,673 | 28.44 | |

| NR | 55,919 | 93.02 | 55,417 | 94.54 | |

| SwissProt | 35,219 | 58.59 | 35,574 | 60.69 | |

| GO | 26,264 | 43.69 | 26,512 | 45.23 | |

| Overall_annotated | 56,261 | 93.59 | 55,772 | 95.15 | |

Gene functional information, motifs and domains of their proteins were assigned by comparing with public databases including SwissProt42, NCBI non-redundant protein sequences (nr)43, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)44, Clusters of orthologous groups for eukaryotic complete genomes (KOG)45 and Gene Ontology (GO)46. The putative domains and GO terms of genes were identified using the InterProScan program47 with default parameters. For the other four databases, BLASTp48 was used to compare the EvidenceModeler-integrated protein sequences against the four well-known public protein databases with an E-value cutoff of 1e-05 and the results with the hit with the lowest E value were retained. Results from the five database searches were concatenated, leading to a total of 56,261 (93.59%) genes in EC_S1 and 55,772 (95.15) genes in EC_N1 with function annotation (Table 9).

Annotation of non-coding RNA genes

To obtain the ncRNA (non-coding RNA), we used two strategies: searching against a database and predicting with a model. Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) were predicted using tRNAscan-SE v2.0.649 with eukaryote parameters. MicroRNA, rRNA, small nuclear RNA, and small nucleolar RNA were detected using Infernal cmscan50 to search the Rfam database51. The rRNAs and their subunits were predicted using RNAmmer52. Finally, a total of 1,163 and 888 rRNA was identified in EC_S1 and EC_N1, respectively. Moreover, total of 7770 ncRNA was identified in EC_S1, including 1180 snRNA (0.0024%), 6188 miRNA (0.0158%), 229 spliceosomal (0.0007%) and 173 other (0.0005%); 7701 ncRNA was identified in EC_N1, including 1065 snRNA (0.0021%), 6246 miRNA (0.0156%), 225 spliceosomal (0.0007%) and 165 other (0.0005%). In addition, 1913 and 2039 tRNA were detected in EC_S1 and EC_N1, covering all 20 anti-codons types of amino acids (Table 10).

Table 10.

Summary of non-coding RNA in the EC_S1 and EC_N1 assemblies.

| Type | EC_S1 | EC_N1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (#) | Average length (bp) | Total length (bp) | Percentage (%) | Number (#) | Average length (bp) | Total length (bp) | Percentage (%) | ||

| rRNA | Total | 1,163 | 306.35 | 356,281 | 0.007 | 888 | 6302.03 | 368966 | 0.0071 |

| 18 S | 43 | 1,819.65 | 78,245 | 0.0015 | 50 | 1772.52 | 88626 | 0.0017 | |

| 28 S | 34 | 4,467.53 | 151,896 | 0.003 | 44 | 4260.2 | 187449 | 0.0036 | |

| 5 S | 1,080 | 115.96 | 125,240 | 0.0025 | 790 | 116.81 | 610 | 0 | |

| 5.8 S | 6 | 150 | 900 | 0 | 4 | 152.5 | 92281 | 0.0018 | |

| ncRNA | Total | 7,770 | 127.53 | 990,911 | 0.0194 | 7701 | 544.67 | 984269 | 0.0189 |

| other | 173 | 146.58 | 25,358 | 0.0005 | 165 | 154.86 | 25552 | 0.0005 | |

| snRNA | 1,180 | 105.15 | 124,074 | 0.0024 | 1065 | 105.16 | 111993 | 0.0021 | |

| miRNA | 6,188 | 130.12 | 805,169 | 0.0158 | 6246 | 129.99 | 811926 | 0.0156 | |

| spliceosomal | 229 | 158.56 | 36,310 | 0.0007 | 225 | 154.66 | 34798 | 0.0007 | |

| regulatory | cis-regulatory | 171 | 45.96 | 7,859 | 0.0002 | 205 | 49.34 | 10115 | 0.0002 |

| tRNA | tRNA | 1,913 | 75.2 | 143,855 | 0.0028 | 2039 | 75.34 | 153619 | 0.0029 |

Data Records

The EC_S1 and EC_N1 genome sequence are available at NCBI database under Bioproject accession PRJNA94768053,54. RNA-seq (The samples’ information are showed in Table S3), NGS, Hi-C, and Nanopore data sets are available at NCBI under Bioproject accession PRJNA74817855. Bionano data sets are available at NCBI Supplementary Files under accession SUPPF_0000004010 (EC_S1) and SUPPF_0000004011 (EC_N1)55. The genome annotation GFF3, CDS sequences, and protein sequences are available at figshare56.

Technical Validation

DNA and RNA integrity

The quality of DNA and RNA molecules and libraries was examined before genome and transcriptome sequencing. The DNA degradation and contamination of the extracted DNA were monitored on 1% agarose gels. DNA purity was then inspected using NanoDrop™ 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), of which OD260/280 ranged from 1.8 to 2.0 and OD 260/230 was between 2.0 to 2.2. Finally, DNA concentration was further measured by Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The integrity of the RNA was determined with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and agarose gel electrophoresis. The purity and concentration of the RNA were determined with the NanodropTM 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and Qubit® 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Only the high-quality RNA sample (OD260/280 = 1.8~2.2, OD260/230 ≥ 2.0, RIN ≥ 7, >1 μg) was used to construct the sequencing library.

Assessment of the genome assembly

After using BUSCO and CEGMA to evaluate genome integrity, we have also evaluated the accuracy of the genome. All the Illumina paired-end reads were mapped to the assembled genome using bwa 0.7.12-r1039 (default)22, and the mapping rate, as well as genome coverage of sequencing reads were assessed. Then samtools v1.457 and bcftools v2.29.258 were used to calculate the homozygous and heterozygous mutation sites corresponding to the samples. Homozygous sites were regarded as genomic error sites to calculate the single base error rate. The accuracy of genomic single base was 99.997% (depth > = 5x) in EC_S1 and 99.996% (depth > = 5x) in EC_N1. The Minimap2 r41 (-x map-ont)23 was used to map all long-reads back to the genome, to calculate mapping rate, coverage, and GC content. the draft genome assemblies were submitted to the NT library (Nucleotide Sequence Database, downloaded on 3rd August, 2018, https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/FASTA/nt.gz) and aligned sequences were eliminated to remove the mitochondria sequences in the assemblies. The results showed that most of the sequences were aligned with the target species, indicating that there was no external contamination in the assembled genome.

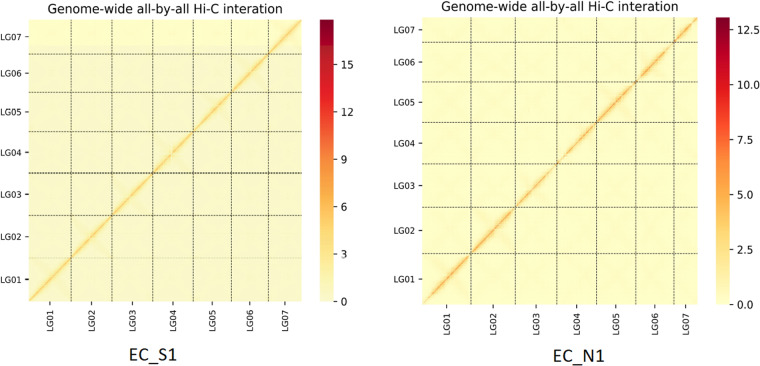

Finally, the seven chromosomes of EC_S1 and EC_N1 assemblies were evaluated. The genome with chromosomes aligned by Hi-C data was divided into ‘bin’ (in a length of 100 KB). The number of Hi-C read pairs covered by any two ‘bins’ was used to define the signal for the interaction between those ‘bins’27, and the heat map of Hi-C interaction of chromosomes was made by HiCPlotter.py script in Python v2.7 (Fig. 3). This figure shows that the intensity of interaction in the diagonal position was higher than that in the non-diagonal position, and there was no obvious noise outside the diagonal, indicating that the chromosomes assembly of both EC_S1 and EC_N1 were high-quality.

Fig. 3.

Heat map of chromosomes interactions by Hi-C sequence of wild barley EC_S1 and EC_N1. LG1-LG7 represent Chr2H, Chr7H, Chr3H, Chr4H, Chr5H, Chr6H, Chr1H, respectively. The horizontal and vertical coordinates represent the order of each ‘bin’ on the corresponding chromosome.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Hubei Key Research and Development Program (2021BBA225) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901438, 31471496), Grain Research and Development Corporation (9176507), and the support from Scientific and Technological Innovation Team Foundation of Yangtze University. The authors would also like to thank the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre for the use of their computing resources.

Author contributions

Wenying Zhang and Tianhua He designed and conceived this work; Rui Pan and Haifei Hu collected the materials and prepared DNA and RNA for sequencing; Rui Pan and Haifei Hu analyzed the data. Rui Pan wrote the manuscript with other authors’ help; Yuhui Xiao, Le Xu, Yanhao Xu, Kai Ouyang and Chengdao Li revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Code availability

No specific code or script was used in this work. All commands used in the processing were executed according to the manual and protocols of the corresponding bioinformatics software.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tianhua He, Email: tianhua.he@murdoch.edu.au.

Wenying Zhang, Email: wyzhang@yangtzeu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-023-02434-2.

References

- 1.Liu M, et al. The draft genome of a wild barley genotype reveals its enrichment in genes related to biotic and abiotic stresses compared to cultivated barley. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020;18:443–456. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonathan B, Blattner FR. Species-level phylogeny and polyploid relationships in Hordeum (Poaceae) inferred by next-generation sequencing and in silico cloning of multiple nuclear loci. Syst. Biol. 2015;644:792–808. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer KFX, et al. Unlocking the barley genome by chromosomal and comparative genomics. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1249–1263. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mingcheng L, et al. Genome sequence of the progenitor of the wheat D genome Aegilops tauschii. Nature. 2017;551:498–502. doi: 10.1038/nature24486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmgren MG, et al. Are we ready for back-to-nature crop breeding? Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fa, Irbairn, A. The origins and spread of domesticated plants in Southwest Asia and Europe. Environ. Archaeol. 15, 99-100 (2010).

- 7.Mascher M, et al. A chromosome conformation capture ordered sequence of the barley genome. Nature. 2017;544:426–433. doi: 10.1038/nature22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng XQ, et al. The draft genome of Tibetan hulless barley reveals adaptive patterns to the high stressful Tibetan Plateau. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:1095–1100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423628112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer KFX, et al. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature. 2012;491:711–716. doi: 10.1038/nature11543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mascher M, et al. Long-read sequence assembly: a technical evaluation in barley. Plant Cell. 2021;33:1888–1906. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai F, et al. Assembly and analysis of a qingke reference genome demonstrate its close genetic relation to modern cultivated barley. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:760–770. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jayakodi M, et al. The barley pan-genome reveals the hidden legacy of mutation breeding. Nature. 2020;588:284–289. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, W. et al. Genome architecture and diverged selection shaping pattern of genomic differentiation in wild barley. Plant Biotechnol. J. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Belton JM, et al. Hi-C: A comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods. 2012;58:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S, et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:884–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranallo-Benavidez TR, Jaron KS, Schatz MC. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1432. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li ZY, et al. Comparison of the two major classes of assembly algorithms: overlap-layout-consensus and de-bruijn-graph. Brief Funct. Genomics. 2012;11:25–37. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elr035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers G. Building fragment assembly string graphs. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:79–85. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaser R, et al. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 2017;27:737–746. doi: 10.1101/gr.214270.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simao FA, et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv. 2013;1303:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Servant N, et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 2015;16:259–270. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0831-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–354. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burton JN, et al. Chromosome-scale scaffolding of de novo genome assemblies based on chromatin interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:1119–1125. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marçais G, et al. MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018;14:e1005944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He W, et al. NGenomeSyn: an easy-to-use and flexible tool for publication-ready visualization of syntenic relationships across multiple genomes. Bioinformatics. 2023;39:121–122. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btad121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang XW, Wang L. GMATA: An integrated software package for genome-scale SSR mining, marker development and viewing. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1350. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gary B. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1–14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurka J, et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Mob DNA. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y, et al. Chromosome genome assembly and annotation of the yellowbelly pufferfish with PacBio and Hi-C sequencing data. Sci. Data. 2019;6:267–275. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0279-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keilwagen J, et al. GeMoMa: homology-based gene prediction utilizing intron position conservation and RNA-seq data. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1962:161–177. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2012;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pertea M, et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mario S, et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:435–439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas BJ, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.TransposonPSI. http://transposonpsi.sourceforge.net/.

- 42.Bairoch A. The swiss-prot protein sequence database user manual. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Camacho C, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421–430. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanehisa M, et al. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tatusov RL, et al. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ashburner M, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zdobnov EM, Rolf A. InterProScan–an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:847–848. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altschul SF, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nawrocki EP, et al. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1335–1337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffiths-Jones S, et al. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:121–124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karin L, et al. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.2023. NCBI Assembly. GCA_029782615.1

- 54.2023. NCBI Assembly. GCA_029783385.1

- 55.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP329205

- 56.Pan R. 2023. Wild barley genome annotation. Figshare. [DOI]

- 57.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2987–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2023. NCBI Assembly. GCA_029782615.1

- 2023. NCBI Assembly. GCA_029783385.1

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP329205

- Pan R. 2023. Wild barley genome annotation. Figshare. [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No specific code or script was used in this work. All commands used in the processing were executed according to the manual and protocols of the corresponding bioinformatics software.