Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the efficacy of expressive writing (EW) versus positive writing (PW) in different populations focusing on mood, health and writing content and to provide a basis for nurses to carry out the targeted treatment.

Design

Systematic review and meta‐analysis.

Methods

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines. Twelve electronic databases and references from articles were searched. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing EW and PW were included. Statistical analyses were executed using Stata 15.0 software.

Results

Twenty‐four RCTs and a total of 1558 participants were analysed. The results showed that for the general population, PW was more positive on mood than EW and could offer more changes in cognitive mechanisms. Among patients, although PW was more conducive to generating positive emotions, EW could stimulate cognitive changes more. Nursing staff should clarify the mechanism of PW and EW, combine the advantages of both and implement intervention according to the characteristics of different populations.

No Patient or Public Contribution

It does not apply to your work because this study is an analysis of published studies and does not involve patients or the public.

Keywords: cognition, emotion, expressive writing, health, nursing, positive writing

1. INTRODUCTION

Psychological intervention is an indispensable part of nursing, reflecting the people‐oriented service concept. With the transformation of the Bio‐psychosocial Medical Model, clinical workers have paid more and more attention to the psychological condition of patients and tried to influence or change their psychological state and social behavior in the course of nursing, which could promote the healthy development. As a powerful tool for psychological intervention, therapeutic writing is convenient, cheap and practical. Through writing, the expresser could understand the event from a new perspective, deepen cognition and comprehension, and make the processing of information more stable, improving mood and reducing chronic stress (Ruini & Mortara, 2022).

As a kind of writing therapy, expressive writing (EW) has been extensively implemented in clinical practice to study the physiological and psychological effects of emotional expression. In this method, participants are asked to put their thoughts and feelings into written words to cope with the pain caused by traumatic events or situations (Pennebaker & Chung, 2011). Numerous studies have shown that therapeutic expressive writing has beneficial physical and mental‐health effects in different user groups, such as chronically ill populations, informal caregivers, clinic nurses and students (Guo, 2023; Qian et al., 2020).

2. THE REVIEW

Expressive writing (EW), also known as written expression and written emotional disclosure, was pioneered by Pennebaker and Beall (1986). The classic EW paradigm involves 15–20 min for 3–4 days within a short period, in which participants are encouraged to express their thoughts and feelings openly about a stressful or traumatic real‐life event without paying attention to grammar or spelling. The theory was based on the act of writing as a means of modifying someone's life story and reconstructing the elements that survivors want to change. Pennebaker et al. (2007) used a computer program to analyze participants' emotional and cognitive processes, showing that EW increased the use of causal terms (e.g. because, effect, etc.) and insight words (e.g. consider, know, etc.), which indicated that participants' ability to establish causal links between life events and to be introspective was enhanced in writing. Thus, the benefits of writing stem from re‐examining traumatic events, becoming more organized and reorganizing meaningful stories (Chu et al., 2020; Glass et al., 2019).

With the advancement of the psychotherapy environment, the paradigm of expressive writing has evolved, and positive psychotherapy has been integrated into writing activities. Positive writing (PW) and benefit‐finding writing (BF) have been developed, which are devoted to guiding participants to emphasize the positive aspects of life. Unlike the writing prompts of EW that specifically focus on overcoming negative events and psychological symptoms, PW puts more emphasis on writing down positive emotions, coping strategies, future expectations and goals to improve participants' well‐being and help them to deal with negative emotions and traumatic events (Segal et al., 2009).

Up till the present moment, the classical expressive writing developed by Pennebaker and Beall (1986) and the positive psychotherapy‐oriented writing developed later have been applied in multiple applications. Deng and colleagues reported that the immediate effect of positive topics was significantly better than that of trauma topics, but the effect of long‐term (>3 months) intervention was not statistically significant (Deng, 2012). Stanton et al. (2002) applied therapeutic writing to the people with breast cancer and found that EW had a positive effect for women with low avoidance behaviour, whereas PW was more beneficial for those with high avoidance behaviour. However, in 2011, O'Connor and colleagues found that for informal caregivers, PW had more benefits than EW, so participants were not encouraged to narrate stressful or traumatic experiences. These contradictory results attracted our attention. It seems that EW and PW had specific user groups and the effects were different.

The data integration of expressive writing mainly focuses on the efficacy analysis of classic expressive writing in people with cancer, trauma survivors, adolescents and so on (Guo, 2023; Qian et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2015). Meta‐analyses on the differences in the efficacy of EW and PW have not been published. To determine the effects of EW and PW in different populations, we used a meta‐analysis and systematic review to assess the differences in mood, health and writing contents after using EW and PW in the general population and patients.

3. AIM

To evaluate the efficacy of EW versus PW in different populations focusing on mood, health and writing content and to provide a basis for nurses to carry out the targeted treatment.

4. METHODS

4.1. Design

The study was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

4.2. Search methods

A systematic literature search of PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Ovid‐EBM Reviews, Clinical Trials and Chinese databases (Sinomed, CNKI, CQVIP, Wanfang) for identification of articles published (from 1986 to December 2020) was performed independently by two investigators (Jiawei Lai and Ying Ren). The language restriction was English or Chinese. We searched for studies with the keywords related to EW, PW and BF (we considered BF to be a type of PW). For example, the complete search strategy for PubMed was: ((Therapeutic writing) OR (expressive writing)) OR (written emotional expression)) OR (written emotional disclosure)) OR (written expression)) AND (((positive writing) OR (positive emotional expression)) OR (positive emotional disclosure)) OR (positive expression)) OR (((benefit finding writing) OR (benefit finding expressive writing)) OR (benefit finding emotional expression)) OR (benefit finding emotional disclosure)) OR (benefit finding expression))) Filters: Clinical Trial, Meta‐Analysis, Randomized Controlled Trial, Review, Systematic Review, Chinese, English, from 1986 to 2020. We did not restrict the population. The reference lists of identified original and review articles were searched manually to identify potential additional articles.

4.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (i) RCTs comparing EW and PW; (ii) the results including any combination of emotion, stress, pain, health and writing contents; (iii) studies using variations of the EW and PW program (different length, frequency or duration of the program).

The exclusion criteria were: (i) mixed interventions of negative prompts and positive prompts, or interventions mixed with other psychotherapies. (ii) studies that did not obtain precise values for the mean and standard deviation (SD) or effect sizes.

4.4. Search outcome

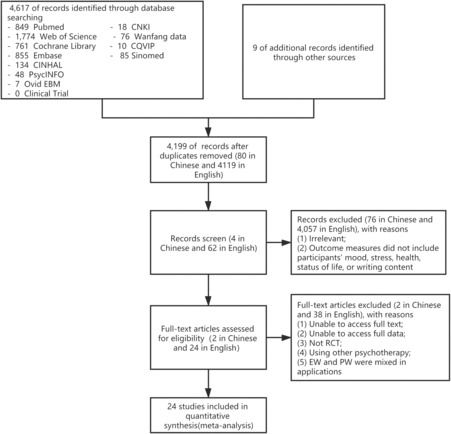

Two investigators (Jiawei Lai and Ying Ren) undertook the main tasks. In total, 4626 articles were identified and duplicates were removed. Subsequently, 4199 titles and abstracts were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 66 articles with full texts were carefully reviewed. Forty articles were excluded due to lack of full text or complete data, non‐RCTs, mixing of other psychological interventions and mixing EW and PW. Among the remaining 26 articles, three articles reported separate outcomes for one RCT (Creswell et al., 2007; Low et al., 2006; Stanton et al., 2002). Two articles reported separate outcomes for one RCT (Chu et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2017). One article conducted separate interventions in two populations (Graves et al., 2005), which were treated as two separate studies in our analysis. Finally, 24 RCTs were included for qualitative analysis. The flowchart of article selection is displayed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the literature search.

4.5. Quality appraisal

Risk of bias was assessed independently by two investigators (Jiawei Lai and Ying Ren) using the risk‐of‐bias tool within the Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org/; Higgins et al., 2022). Disagreements were resolved by a third investigator (Huijuan Song).

4.6. Data abstraction

Three investigators (Ying Wang, Shuang Li and Feng Xiao) extracted data on the characteristics of the study (e.g. trial design, randomization and blinding), demographic characteristics (e.g. sample size, population and age) and intervention conditions (e.g. intervention type, prompts, length and frequency), and outcome measures and results. If data were missing, a researcher contacted the author to obtain the relevant information. If information was not available, it was marked as ‘not reported’ (Zhou et al., 2015).

4.7. Synthesis

Data analyses were conducted by two researchers (Jiawei Lai and Ying Wang). Primary outcome measures were positive effect (PE), negative effect (NE), depression, anxiety, stress, health and writing contents after the writing intervention. Indicators of health include overall health, pain, languidness (Pennebaker's Inventory of Limbic Languidness, PILL), physical symptoms and health visits. Assessment of writing contents includes self‐rating of the essay and analysis of written words. Self‐rating was done according to participants' feelings about the writing tasks. Participants were asked mainly about how personal their essays were, how much they revealed emotions in their essays, how much writing increased their understanding of their experience, and how valuable the experiment was to them. Levels of scoring were employed to assess changes in the feeling of writing tasks. The analysis of writing words adopted Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), which is used to calculate the proportion of certain words used by participants (e.g. positive words and insight words) and to observe changes in words used in different writing tasks.

Stata 15.0 (Stata) was used for analyses. Measurement data are the mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Weighted (W)MD and standardized (S)MD were used as the effective indices for data measured by the same method and by different methods, respectively. Inverse variance was employed to merge and analyse the data of the included studies according to α = 0.05. The chi‐squared test was used to assess heterogeneity among studies (test level: p = 0.10), and I 2 was used to determine the degree of heterogeneity. p > 0.10 and I 2 < 50% indicated no statistically significant heterogeneity, in which case a fixed‐effects model (FEM) was used; p ≤ 0.10 and I 2 ≥ 50% indicated statistically significant heterogeneity, in which case a random‐effects model (REM) was employed and subgroup analysis was done to explore the heterogeneity source (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). Egger's test was employed to evaluate publication bias, with p < 0.05 suggesting that bias was present (Egger et al., 1997).

5. RESULTS

5.1. Study characteristics and quality assessment

Table 1 shows the key characteristics of the included studies. Ultimately, 26 full‐text articles were included in the analysis (Amiri et al., 2019; Ashley et al., 2011; Baikie et al., 2012; Burton & King, 2008; Chu et al., 2019; Creswell et al., 2007; Danoff‐Burg et al., 2006; Graves et al., 2005; Harvey et al., 2018; King, 2001; King & Miner, 2000; Klein & Boals, 2001; Kloss & Lisman, 2002; Li, 2014; Lichtenthal & Cruess, 2010; Low et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2017; Lumley et al., 2011; Lyubomirsky et al., 2006; McCullough et al., 2006; Norman et al., 2004; O'Connor et al., 2011, 2013; Segal et al., 2009; Stanton et al., 2002; Zhou & Zhu, 2014).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the studies using expressive writing (EW) and positive writing (PW) included in the meta‐analysis.

| Studies | State | Populations | Patients (N) | Age (years, M ± SD, range) | Contents for EW | Contents for PW | Frequency | Follow‐up (months [m]/weeks [w]) | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EW | PW | EW | PW | ||||||||

| Amiri et al. (2019) | IRAN | Patients in the open‐heart surgery department | 25 | 25 | 57.1 ± 2.0 | 58.0 ± 8.3 | Negative emotions and unpleasant memories | Positive emotions and positive memories | 10–15 min each time, 4 times for lasting a week | 1 w, 1 m | DASS |

| Ashley et al. (2011) | UK | Informal caregivers | 51 | 51 | 57.2 ± 11.6 | 54.1 ± 12.3 | Emotions and thoughts about the role as a caregiver | Emotions and thoughts about the positive and happy experiences | 20 min each day for 3 days | 2 w, 2 m, 6 m | BSI, LIWC, MC |

| Baikie et al. (2012) | AU | People with mood disorders | 70 | 69 | 40.2 ± 11.6 | Thoughts and feelings about the most traumatic experience | Thoughts and feelings about the most intensely positive experience | 20 min each time, 4 times for lasting 2 weeks | 1 m, 4 m |

CES‐D, DASS, PILL, OHQ |

|

| Burton and King (2008) | USA | Undergraduate psychology students | 15 | 15 | NR | The trauma | The positive experience | one time a day, 2 min each time, 2 days in total | 4–6 w | Mood, PILL, LIWC | |

| Chu et al. (2019); Lu et al. (2017) | USA | Chinese American breast cancer survivors | 34 | 29 |

54.5 ± 7.9 (15–62) |

Thoughts and feelings about the cancer | Emotional disclosure, coping and benefit‐finding | 30 min each time, 3 times a week for 3 weeks | 1 m, 3 m, 6 m | MC, LIWC | |

| Creswell et al. (2007), Low et al. (2006), Stanton et al. (2002) | USA | Early‐stage patients with breast cancer | 21 | 21 |

49.5 ± 12.2 (21–76) |

Thoughts and feelings about the breast cancer | Positive thoughts and feelings about the breast cancer | 20 min each time, 4 times for lasting 3 weeks | 1 m, 3 m | POMS, HI, LIWC, MC | |

| Danoff‐Burg et al. (2006) | USA | Adults with lupus or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | 24 | 27 | 51.2 ± 13.3 | Thoughts and feelings about the rheumatic disease | Positive thoughts and feelings about the illness experience | 20 min each time, 4 times for lasting 3 weeks | 1 m, 3 m | CES‐D, POMS, Pain, STAS | |

| Graves et al. (2005) | USA | Patients with breast cancer | 12 | 12 | 57.8 ± 10.5 | The most traumatic and upsetting experiences | The most joyful and happy experiences | 20 min, only once | N/A | CES‐D, PANAS, LIWC | |

| Healthy individuals | 12 | 12 | 57.0 ± 12.2 | ||||||||

| Harvey et al. (2018) | USA | Spousal cancer caregivers | 22 | 22 | 56.6 ± 12.1 | Undisclosed thoughts/feelings related to the cancer experience | Positive outcomes in light of the cancer experience | 15 min each time, once a week for 3 weeks | N/A | PSS, PHQ, MC | |

| King and Miner (2000) | USA | Psychology students | 38 | 32 | 21.0 (18–36) | Traumatic event or traumatic loss experience | Benefit experience made better to meet the challenges | 20 min each time, once a day for 3 days | N/A | Mood, LIWC, HI, MC | |

| King (2001) | USA | Psychology students | 22 | 19 | 21.0 ± 3.2 (18–42) | Traumatic event or loss experience | Visions of a better life in the future | 20 min each time, once a day for 4 days | N/A | Mood, HI, MC | |

| Klein and Boals (2001) | USA | College students | 34 | 33 | NR | Thoughts and feelings about the negative event | Thoughts and feelings about the positive event | 5 times in one semester | N/A | LIWC, MC | |

| Kloss and Lisman (2002) | USA | College students | 43 | 43 | 18–19 | The most traumatic and upsetting experiences | The happiest experience | 20 min each time, once a day for 3 days | 2 m, 3 m | HI, MC, BDI, STAI, PILL, PANAS, | |

| Li (2014) | CN | College students | 15 | 15 | 19–25 | Social anxiety events | Positive attitudes and actions about the negative events | 20 min each time, once a day for 4 days | 1 m | LSAS | |

| Lichtenthal and Cruess (2010) | USA | Undergraduate students in introductory psychology courses | 16 | 17 | 19.2 ± 1.3 | 20.4 ± 5.1 | Thoughts and emotions related to the loss | Positive life changes related to the loss | 20 min each time, 3 times for lasting 1 week | 3 m | CES‐D, PCL‐C, HI, MC |

| Lumley et al. (2011) | USA | Adults with RA | 43 | 24 | 55.4 ± 11.7 | 53.1 ± 10.0 | The stressful or traumatic event or experience | Positive emotional events | 20 min each time, once a day for lasting a week | 1 m, 3 m, 6 m | MPQ, PANAS, LIWC, MC |

| Lyubomirsky et al. (2006) | USA | Undergraduate psychology students | 20 | 24 |

19.4 ± 2.6 (17–38) |

The traumatic or negative event | The happiest life event | 15 min each time, once a day for 3 days | 1 m | PANAS, HI, MC | |

| McCullough et al. (2006) | USA | College students | 101 | 102 |

19.3 ± 2.8 (18–45 |

The negative event and feelings and the negative effects | The negative event and the positive effects/potential effects | 20 min, only one time | N/A | LIWC | |

| Norman et al. (2004) | USA | Women with chronic pelvic pain (CPP | 28 | 20 | 38.2 (18–64) | The negative emotional experiences related to CPP | The positive emotional experiences unrelated to CPP | At least 20 min each time, once a day for 3 days | 2 m | PANAS, MPQ, MC | |

| O'Connor et al. (2011) | UK | Female | 51 | 53 | 19.5 (18–22 | The stressful or traumatic issue/event about the body | Reading six body image success stories vignettes and writing about them | 15 min each time, once a day for 3 days | 4w | CES‐D, LIWC | |

| O'Connor et al. (2013) | UK | Healthy staff and students | 39 | 41 | 22.7 (18–41) | The most upsetting experience | The most positive and happiest experiences | 20 min each time, once a day for 3 days | 1 m, 6 m | CES‐D, HI, MC | |

| Segal et al. (2009) | USA | Psychology of undergraduate students | 30 | 30 |

24.0 ± 8.2 (17–53) |

The most traumatic and upsetting experiences | The most positive feelings and thoughts | 20 min each time, once every 2–3 days for lasting a week | 1 m | PANAS, MC | |

| Zhou and Zhu (2014) | CN | Senior high school students | 27 | 29 |

16.6 ± 0.6 (14–18) |

The strong negative emotional events and the deepest emotions | The strong positive emotional events and the deepest emotions | 20 min each time, once a day for 3 days | 2 w | POMS, CES‐D | |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CES‐D, The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; HI, Health indices, Health Service visits and illnesses or symptoms; LIWC, linguistic inquiry and word count; LSAS, Liebowitz social anxiety scale; MC, manipulation checks, self‐ratings of participants' feelings about the writing tasks; Mood, Rating the positive/negative moods on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal) in different emotional words; MPQ, McGill Pain Questionnaire‐Short Form; OHQ, overall health questions; Pain, Average level of pain during the past week was measured using a visual analogue scale; PANAS, positive and negative affect schedule; PCL‐C, the Post‐traumatic Stress Checklist‐Civilian Version; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PILL, Pennebaker's Inventory of Limbic Languidness; POMS, profile of mood states; PSS, 10‐item Perceived Stress Scale; STAS, State–Trait Anxiety Scale.

There were 1558 participants: 796 participants in the EW group and 762 in the PW group. The population groups were divided into ‘patients’ and ‘general population’. The former with a specific disease diagnosis comprised patients with cancer, immune disease, chronic pain or mental‐health problems; the latter without a specific disease diagnosis comprised college students studying psychology, informal caregivers and other member of the general people (e.g. female group). The studies were conducted in USA (17), UK (3), China (2), Australia (1) and Iran (1).

The results of study quality assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration are shown in Table 2. Overall, the evidence had a high risk of reporting and selection bias, ‘unclear’ risk of detection and performance bias and low risk of attrition and other types of bias.

TABLE 2.

Risk of bias.

| Reference | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiri et al. (2019) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ashley et al. (2011) | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Baikie et al. (2012) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Burton and King (2008) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Chu et al. (2019), Lu et al. (2017) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Creswell et al. (2007), Low et al. (2006), Stanton et al. (2002) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Danoff‐Burg et al. (2006) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Graves et al. (2005) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Harvey et al. (2018) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| King and Miner (2000) | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| King (2001) | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Klein and Boals (2001) | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Kloss and Lisman (2002) | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Li (2014) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lichtenthal and Cruess (2010) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes |

| Lumley et al. (2011) | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes |

| Lyubomirsky et al. (2006) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| McCullough et al. (2006) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Norman et al. (2004) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| O'Connor et al. (2011) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes |

| O'Connor et al. (2013) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes |

| Segal et al. (2009) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Zhou and Zhu (2014) | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes |

5.2. Outcomes

We regarded PW as the intervention group and EW as the control group. When the number of included studies was >5, we divided subgroups into different populations for analysis. Due to the large differences in writing‐time settings, to control for heterogeneity, we attempted to select data at similar time points when analysing emotion and health. We thought that time had little effect on evaluation of writing content, so the data were included directly in the analysis.

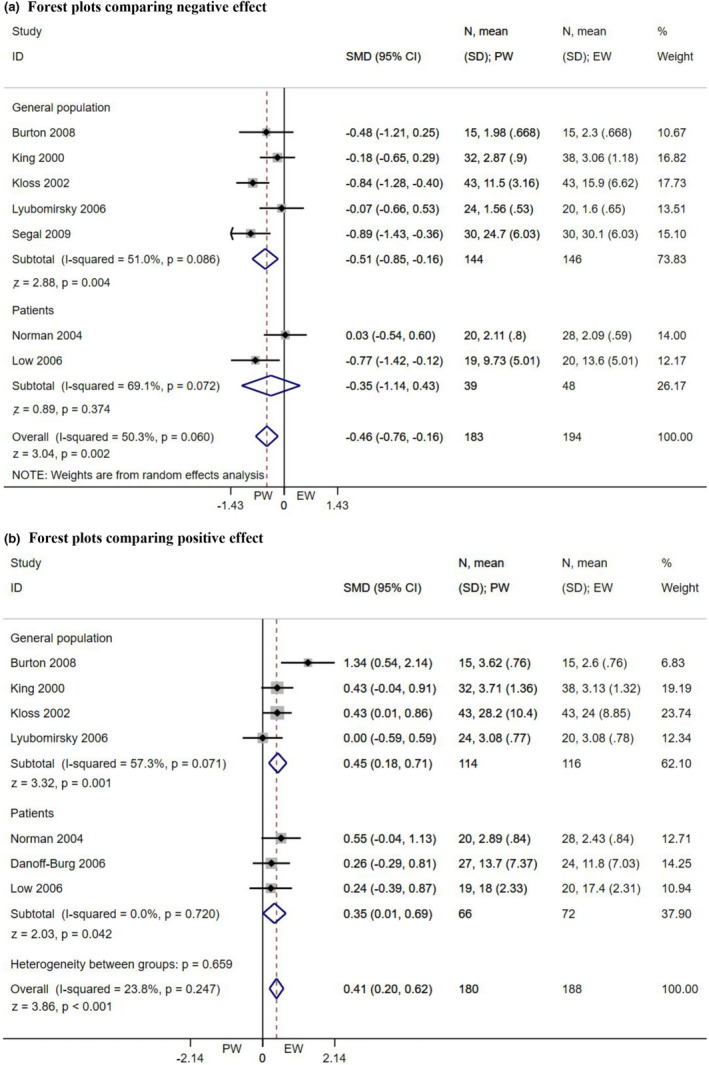

5.2.1. Influence on mood

Seven studies evaluated the NE in participants. Since the data were derived from the results of three measurement tools (Mood, Profile of Mood States and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule), SMD was used as the effect indicator for data consolidation. Two studies (Burton & King, 2008; Segal et al., 2009) reported only the MD, we used this along with the p‐value and sample size to obtain the SD (Liu, 2011) and then included the data in the meta‐analysis. The REM was used for statistical analyses (Figure 2a). Members of the EW group had a higher prevalence of negative emotions than that in the PW group (MD = −0.46, 95%CI: −0.76, −0.16, p = 0.002). To further analyse the effects in different populations, we divided the subgroups into patients and general population. There was no statistically significant difference between the two types of prompt writing in patients (p = 0.374). The main effect of the overall difference arose from the general population (MD = −0.51, 95% CI: −0.85, −0.16, p = 0.004).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plots comparing negative effect (a) and positive effect (b).

Seven studies evaluated the PE in participants. The data‐processing methods were identical to those described above. SMD was used as the effect indicator, and the FEM was used for statistical analyses (p = 0.247, I 2 = 23.8%; Figure 2b). The result showed that the positive emotion of the EW group was lower (MD = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.62, p < 0.001). Among the general population, PW elicited more benefits (MD = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.71, p = 0.001), whereas, for patients, there was just a marginally statistically significant difference between the two writing prompts (MD = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.69, p = 0.042).

The analysis of depression was based on REM (p = 0.073, I 2 = 46.1%), and anxiety (p = 0.196, I 2 = 33.8%) and stress (p = 0.380, I 2 = 0%) were based on FEM. The SMD was employed as the effect indicator. We found no statistically significant difference between the two prompts in different populations (both p > 0.10).

5.2.2. Influence on health

We explored the health status of participants. The number of studies on all projects was no more than five, so the population was not divided into subgroups for analysis. SMD was used as an effective indicator, and FEM was used for analyses (p > 0.10, I 2 = 0%). Overall health, pain, PILL, physical symptoms and health visits under the two writing conditions were not statistically significantly different (all p > 0.20).

5.2.3. Assessment of writing contents

We conducted the REM to examine the group difference in participants' ratings on the extent to which their writing essays were personal (p = 0.041, I 2 = 68.6%) and meaningful (p = 0.084, I 2 = 48.5%), and the FEM to the emotion revealing (p = 0.108, I 2 = 40.6%), upsetting (p = 0.498, I 2 = 0%) and difficult (p = 0.516, I 2 = 0%). Since different levels of the Likert scale were involved, SMD was used as the effect indicator. The ratings for emotion revealing, upsetting and difficult in general population were higher among the EW group (p < 0.001), but the rating for meaningful in patients was lower (p = 0.018). There was no statistically significant difference in personality between the two groups (p = 0.139).

Weighted mean difference was used as the effect indicator in the analysis of writing words, including positive words (e.g. love and sweet), negative words (e.g. hurt and nasty), cognitive mechanisms (e.g. cause and ought) and insight (e.g. think and know). Using the REM in both negative words (p < 0.001, I 2 = 77.5%) and positive words (p = 0.002, I 2 = 68.0%), whether it was general population or patients, the EW group used more negative words (p < 0.001), and the PW group used more positive words (p < 0.001), which was consistent with the requirements of writing prompts. FEM in insight (p = 0.398, I 2 = 1.4%) revealed that in the general population and patients, the EW group used more insight words than the PW group (p < 0.001). However, when using REM to analyse the cognitive mechanism of the two groups, there was extremely high heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I 2 = 98.5%) with a completely opposite result in patients and the general population. Patients were more inclined to show cognitive mechanisms in EW (MD = −2.61, 95%CI: −3.59, −1.63, p < 0.001), whereas the general population disclosed more cognitive mechanism changes in PW (MD = 3.63, 95% CI: 0.09, 7.16, p = 0.044).

5.2.4. Publication bias

There was no evidence of publication bias (Egger test, p > 0.05) except for studies on anxiety (Egger's test, p = 0.006), positive words (Egger's test, p = 0.021) and PILL (Egger's test, p = 0.038).

6. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyse the difference in efficacy between EW and PW in terms of mood, health and writing contents in different groups. However, several aspects related to these results should be interpreted with caution.

6.1. Writing and mood

The random‐effects model of this meta‐analysis achieved a statistically significant effect size of SMD indicating that members of the EW group in general population had higher negative emotions and lower positive emotions than that in the PW group. The lack of similar metadata made it difficult to compare the results with previous studies. However, there are two possible explanations for this finding. First, writing about traumatic experiences in the general population may be viewed as a fear activation rather than a problem‐solving process, and exposure increases especially for people who write about repeated events continuously (Kloss & Lisman, 2002). Positive writing may lead participants to turn aversive experiences into opportunities to cultivate resilience and positive outcomes, thus reducing negative reactions (Saldanha & Barclay, 2021). Second, we found from the previous research that content disclosed by the general population is often popular and common with less pressure (Doucet et al., 2018). According to the ratings of writing tasks in the general population, we could infer that PW was less difficult and upsetting, which could be why it had more advantages in general population. It suggests that PW may be more appropriate for the general population with less stress, such as informal caregivers and clinical workers.

Another finding was that the PW group of patients had higher positive emotions than the EW group with a small statistically significant difference. It was inconsistent with the meta‐analysis from Lim and Tierney (2023) on the effects of positive psychology interventions and other positive interventions on patients with depression, which had shown an insignificant result. There are three possible reasons. First, patients with early breast cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and chronic pelvic pain were included in the study. For these patients, their disease was not traumatic enough to trigger the beneficial effects of EW, especially during the recovery phase, which may be the floor effect. Previous studies have also confirmed that for patients with long‐term illness, EW has no statistically significant effect on mental health (Nyssen et al., 2016). Different from the mechanism of EW, PW does not target anxiety and depression symptoms but emphasizes the importance of holding a positive attitude toward the past, present and future. Thereby cultivating future‐oriented positive cognition and emotions, such as optimism and hope. Secondly, PW was more meaningful based on ratings of the writing task in patients, suggesting that PW might benefit patients by improving their ability to assign meaning to their experience. PW was able to guide patients to adjust their mindset and change cognition, discover the positive meaning of past experiences and thus increased coping resources and provided positive emotions (Ruini & Mortara, 2022). Thirdly, the patients involved in this study were mostly female. It was found that women in PW used fewer emotion expression suppression strategies, and the ability to induce or change the experience of a certain emotion by writing about positive experiences may have enhanced the skills of female participants to regulate their emotions by expressing positive or negative influences more frequently in their daily lives (Suhr et al., 2017). PW thus has certain positive effects on patients, especially female patients who may benefit more from PW. We should pay attention to the gender of patients and consider their differences in emotional expression when providing psychological rehabilitation services.

There was no statistically significant difference between groups in patients with negative emotions, perhaps because only two studies were included and fewer data could be analysed. The two studies involved patients with different diseases (early breast cancer and chronic pelvic pain), and the data were extracted at different time points (3 weeks and 2 months after the end of the intervention), leading to high heterogeneity in the result. Subsequent intervention studies using writing therapy in clinical patients should be increased, and measures should be harmonized as far as possible to obtain data that can be integrated for analysis.

In addition, there were no statistically significant differences between groups for specific negative emotions–depression, anxiety and stress–in the general population or among patients. It shows that PW and EW had the same effect on single negative emotion. This seems to contradict the above finding that PW has an advantage in reducing negative emotions, which might be influenced by the limited number of studies. Future work should focus on the influence and mechanism of different writing paradigms on negative emotional characteristics in order to obtain more reliable results.

6.2. Writing and health

Different types of writing had no statistically significant effect on participants' health, suggesting that EW and PW had essentially the same effect on health. Although samples from different groups were not divided into subgroups for analysis due to the limited number of studies, the heterogeneity of the studies was small, which made the conclusion more reliable. Several causes may account for these results. For example, both types of writing could improve participants' health. The study has shown that writing therapy can promote the behaviour of rethinking, causing changes in cognition and coping, and thus have similar health consequences through long‐term activation of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, adrenal gland and/or immune system (Creswell et al., 2007). There was also case in which neither type of writing made any difference to the participants' health (O'Connor et al., 2013). Most data were collected over a period of more than 2 months. The study has found that writing therapy was affected by dosage and its positive effects might not last for a long time (Guo, 2023). The problem with all the studies was that the indicators used to assess health were complex, affected by multiple factors and difficult to follow up. Therefore, we recommend that clinical workers should focus on more specific indicators and analyse participants' health problems through objective data. For example, Patient‐Reported Outcomes Instruments System for Chronic Diseases (PROMIS) and Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) can be combined with e‐health to obtain more regular, uniform and accurate follow‐up data.

6.3. Writing and writing contents

We found that insight words involved in cognitive mechanisms were used more often in EW regardless of the population. However, patients used more cognitive words in EW, while general population used more cognitive words in PW. The Study has shown that EW could benefit patients by activating their cognitive processing, strengthening self‐reflection, re‐evaluating constantly and promoting changes in cognition and coping (Niles et al., 2016). Similarly, PW allowed participants to make connections between their current lives and future dreams or to reflect on their relationships with meaningful others, which might promote self‐exploration and understanding. We believe that qualitative research could be carried out to explore the changing paths of cognition in EW and PW, identify the effective components and establish a more targeted mode of therapeutic writing. For example, Seyedfatemi et al. (2021) used the conventional content analysis approach to analyse the writing content and combined it with the semi‐structured interview to understand the experience and feelings of participants in the intervention process. Choi et al. (2023) adopted descriptive phenomenology and used expressive writing as a tool to explore the life experiences of Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors. The results showed great heterogeneity, which might be related to the writing length and incorrect recognition by the LIWC (Tang & Ryan, 2020). Therefore, we should rely not only on software when analysing writing content, but instead combine it with manual evaluation to explore the deeper meaning of the data.

6.4. Limitations

The limited number of current meta‐analyses of PW and EW were poorly homogenous–including our study–reflecting the fact that the research on writing therapy as adjunctive therapy for patients remains diverse. Assessment tools, indicators, outcome measures, included samples, indications, intervention methods and conclusions are varied. The poor homogeneity of RCTs also led to the major limitations of our meta‐analysis. First of all, due to inconsistent outcome measurements and incomplete data from different tools, most indicators could not be combined for meta‐analysis. Some data were estimated based on sample size and secondary statistics (such as p‐value), which might affect the accuracy of results. Second, inconsistent factors or indicators, such as the characteristics of the subjects and the timing of data collection, might lead to a bias in the results. In addition, the limited number of studies available made it difficult to investigate potential publication bias affecting the analysis. Although suggestive of publication bias, the power of the Egger test was too low (it is generally accepted that the Egger test should be performed over 10 studies) to distinguish chance from true asymmetry. Finally, we divided groups into general population and patients and failed to consider the influence of basic emotions, ethnicities and cultures, which should be considered in future studies.

7. CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review and meta‐analysis showed that PW provided more positive emotions and alleviated negative emotions than EW in both the general population and patients. In addition, PW promotes the cognitive mechanism in the general population, while EW contributes to cognitive improvement in patients. Therefore, PW could be used for intervention in non‐clinical populations, such as informal caregivers and medical staff. For clinical patients, it might be necessary to further explore the mechanism of PW and EW and combine the benefits of both emotional and cognitive mechanisms to form a multi‐mode intervention.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization (Jiawei Lai), Methodology (Jiawei Lai and Ying Ren), Formal analysis (Jiawei Lai and Ying Wang), Data visualization (Jiawei Lai), Manuscript drafting (Jiawei Lai), Manuscript review and editing (Huijuan Song and Ying Wang), Supervision (Huijuan Song), Project administration (Huijuan Song), Provision of resources (Shuang Li, Feng Xiao and Shaona Liao), Data curation (Tingping Xie and Weihuan Zhuang). Jiawei Lai and Huijuan Song contributed equally to this work and should both be considered first authors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ETHICAL STATEMENTS

There are no human participants in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Jinyan Wu for her comments on and suggestions about our manuscript. This work was supported by the Southern Medical University of Nanfang Hospital under Grant 2020H006, 2021H008 and 2021EBNc007.

Lai, J. , Song, H. , Wang, Y. , Ren, Y. , Li, S. , Xiao, F. , Liao, S. , Xie, T. , & Zhuang, W. (2023). Efficacy of expressive writing versus positive writing in different populations: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nursing Open, 10, 5961–5974. 10.1002/nop2.1897

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Amiri, Z. , Sanagoo, A. , Jouybari, L. , & Kavosi, A. (2019). The effect of written emotional disclosure on depression, anxiety, and stress of patients after open heart surgery. Brain, 10(2), 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, L. , O'Connor, D. B. , & Jones, F. (2011). Effects of emotional disclosure in caregivers: Moderating role of alexithymia. Stress and Health, 27(5), 376–387. 10.1002/smi.1388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baikie, K. A. , Geerligs, L. , & Wilhelm, K. (2012). Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: An online randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 310–319. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton, C. M. , & King, L. A. (2008). Effects of (very) brief writing on health: The two‐minute miracle. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13(1), 9–14. 10.1348/135910707X250910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E. , Shin, L. J. , Chen, L. , & Lu, Q. (2023). Lived experiences of young adult Chinese American breast cancer survivors: A qualitative analysis of their strengths and challenges using expressive writing. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 62, 102253. 10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Q. , Lu, Q. , & Wong, C. C. Y. (2019). Acculturation moderates the effects of expressive writing on post‐traumatic stress symptoms among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26(2), 185–194. 10.1007/s12529-019-09769-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Q. , Wu, I. , & Lu, Q. (2020). Expressive writing intervention for posttraumatic stress disorder among Chinese American breast cancer survivors: The moderating role of social constraints. Quality of Life Research, 29(4), 891–899. 10.1007/s11136-019-02385-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. D. , Lam, S. , Stanton, A. L. , Taylor, S. E. , Bower, J. E. , & Sherman, D. K. (2007). Does self‐affirmation, cognitive processing, or discovery of meaning explain cancer‐related health benefits of expressive writing? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(2), 238–250. 10.1177/0146167206294412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danoff‐Burg, S. , Agee, J. D. , Romanoff, N. R. , Kremer, J. M. , & Strosberg, J. M. (2006). Benefit finding and expressive writing in adults with lupus or rheumatoid arthritis. Psychology & Health, 21(5), 651–665. 10.1080/14768320500456996 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X. (2012). An application research on with written emotional expression improving self‐efficacy of college students . (Unpublished master's degree thesis), Chongqing Normal University. (Original work published in Chinese).

- Doucet, M. H. , Farella Guzzo, M. , & Groleau, D. (2018). Brief report: A qualitative evidence synthesis of the psychological processes of school‐based expressive writing interventions with adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 113–117. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M. , Davey Smith, G. , Schneider, M. , & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass, O. , Dreusicke, M. , Evans, J. , Bechard, E. , & Wolever, R. Q. (2019). Expressive writing to improve resilience to trauma: A clinical feasibility trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 34, 240–246. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves, K. D. , Schmidt, J. E. , Bollmer, J. , Fejfar, M. , Langer, S. , Blonder, L. X. , & Andrykowski, M. A. (2005). Emotional expression and emotional recognition in breast cancer survivors: A controlled comparison. Psychology & Health, 20, 579–596. 10.1080/0887044042000334742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. (2023). The delayed, durable effect of expressive writing on depression, anxiety and stress: A meta‐analytic review of studies with long‐term follow‐ups. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(1), 272–297. 10.1111/bjc.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, J. , Sanders, E. , Ko, L. , Manusov, V. , & Yi, J. (2018). The impact of written emotional disclosure on cancer caregivers' perceptions of burden, stress, and depression: A randomized controlled trial. Health Communication, 33(7), 824–832. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1315677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. , & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. , Thomas, J. , Chandler, J. , Cumpston, M. , Li, T. , & Page, M. J. (2022). In Welch V. A. (Ed.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons. https://training.cochrane.org/handbooks [Google Scholar]

- King, L. , & Miner, K. (2000). Writing about the perceived benefits of traumatic events: Implications for physical health. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 220–230. 10.1177/0146167200264008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King, L. A. (2001). The health benefits of writing about life goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 798–807. 10.1177/0146167201277003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, K. , & Boals, A. (2001). Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology‐General, 130(3), 520–533. 10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloss, J. D. , & Lisman, S. A. (2002). An exposure‐based examination of the effects of written emotional disclosure. British Journal of Health Psychology, 7(Pt 1), 31–46. 10.1348/135910702169349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. (2014). A research on expressive writing intervening social anxiety in college . (unpublished master's degree thesis), Guangxi university. (original work published in Chinese).

- Lichtenthal, W. G. , & Cruess, D. G. (2010). Effects of directed written disclosure on grief and distress symptoms among bereaved individuals. Death Studies, 34(6), 475–499. 10.1080/07481187.2010.483332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W. L. , & Tierney, S. (2023). The effectiveness of positive psychology interventions for promoting well‐being of adults experiencing depression compared to other active psychological treatments: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24(1), 249–273. 10.1007/s10902-022-00598-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. (2011). Data Extraction. In Wang D. (Ed.), The design and implementation methods of systematic review and meta–analysis. (pp. 77–85). People's Medical Publishing House. (Original work published in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Low, C. A. , Stanton, A. L. , & Danoff‐Burg, S. (2006). Expressive disclosure and benefit finding among breast cancer patients: Mechanisms for positive health effects. Health Psychology, 25(2), 181–189. 10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q. , Wong, C. C. , Gallagher, M. W. , Tou, R. Y. , Young, L. , & Loh, A. (2017). Expressive writing among Chinese American breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology, 36(4), 370–379. 10.1037/hea0000449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley, M. A. , Leisen, J. , Partridge, T. R. , Meyer, T. M. , Radcliffe, A. M. , Macklem, D. J. , Naoum, L. A. , Cohen, J. L. , Lasichak, L. M. , Lubetsky, M. R. , Mosley‐Williams, A. D. , & Granda, J. L. (2011). Does emotional disclosure about stress improve health in rheumatoid arthritis? Randomized, controlled trials of written and spoken disclosure. Pain, 152(4), 866–877. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S. , Sousa, L. , & Dickerhoof, R. (2006). The costs and benefits of writing, talking, and thinking about life's triumphs and defeats. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4), 692–708. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.4.692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, M. E. , Root, L. M. , & Cohen, A. D. (2006). Writing about the benefits of an interpersonal transgression facilitates forgiveness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 887–897. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles, A. N. , Byrne Haltom, K. E. , Lieberman, M. D. , Hur, C. , & Stanton, A. L. (2016). Writing content predicts benefit from written expressive disclosure: Evidence for repeated exposure and self‐affirmation. Cognition & Emotion, 30(2), 258–274. 10.1080/02699931.2014.995598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, S. A. , Lumley, M. A. , Dooley, J. A. , & Diamond, M. P. (2004). For whom does it work? Moderators of the effects of written emotional disclosure in a randomized trial among women with chronic pelvic pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(2), 174–183. 10.1097/01.psy.0000116979.77753.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyssen, O. P. , Taylor, S. J. , Wong, G. , Steed, E. , Bourke, L. , Lord, J. , Ross, C. A. , Hayman, S. , Field, V. , Higgins, A. , Greenhalgh, T. , & Meads, C. (2016). Does therapeutic writing help people with long‐term conditions? Systematic review, realist synthesis and economic considerations. Health Technology Assessment, 20(27), vii–367. 10.3310/hta20270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, D. B. , Hurling, R. , Hendrickx, H. , Osborne, G. , Hall, J. , Walklet, E. , Whaley, A. , & Wood, H. (2011). Effects of written emotional disclosure on implicit self‐esteem and body image. British Journal of Health Psychology, 16(3), 488–501. 10.1348/135910710X523210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, D. B. , Walker, S. , Hendrickx, H. , Talbot, D. , & Schaefer, A. (2013). Stress‐related thinking predicts the cortisol awakening response and somatic symptoms in healthy adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(3), 438–446. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Shamseer, L. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Brennan, S. E. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Li, T. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McDonald, S. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J. W. , & Beall, S. K. (1986). Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(3), 274–281. 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J.W. , Booth, R.J. , & Francis, M.E. (2007). Linguistic inquiry and word count (LIWC2007). Erlbaum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J. W. , & Chung, C. K. (2011). Expressive writing: Connections to physical and mental health. In Friedman H. S. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 417–437). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J. , Zhou, X. , Sun, X. , Wu, M. , Sun, S. , & Yu, X. (2020). Effects of expressive writing intervention for women's PTSD, depression, anxiety and stress related to pregnancy: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112933. 10.1016/j.psychres [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini, C. , & Mortara, C. C. (2022). Writing technique across psychotherapies‐from traditional expressive writing to new positive psychology interventions: A narrative review. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 52(1), 23–34. 10.1007/s10879-021-09520-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha, M. F. , & Barclay, L. J. (2021). Finding meaning in unfair experiences: Using expressive writing to foster resilience and positive outcomes. Applied Psychology. Health and Well‐Being, 13(4), 887–905. 10.1111/aphw.12277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal, D. L. , Tucker, H. C. , & Coolidge, F. L. (2009). A comparison of positive versus negative emotional expression in a written disclosure study among distressed students. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(4), 367–381. 10.1080/10926770902901345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seyedfatemi, N. , Ghezeljeh, T. N. , Bolhari, J. , & Rezaei, M. (2021). Effects of family‐based dignity intervention and expressive writing on anticipatory grief of family caregivers of patients with cancer: A study protocol for a four‐arm randomized controlled trial and a qualitative process evaluation. Trials, 22(1), 751. 10.1186/s13063-021-05718-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, A. L. , Danoff‐Burg, S. , Sworowski, L. A. , Collins, C. A. , Branstetter, A. D. , Rodriguez‐Hanley, A. , Kirk, S. B. , & Austenfeld, J. L. (2002). Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20(20), 4160–4168. 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhr, M. , Risch, A. K. , & Wilz, G. (2017). Maintaining mental health through positive writing: Effects of a resource diary on depression and emotion regulation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(12), 1586–1598. 10.1002/jclp.22463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. , & Ryan, L. (2020). Music performance anxiety: Can expressive writing intervention help? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1334. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C. , Wu, Y. , An, S. , & Li, X. (2015). Effect of expressive writing intervention on health outcomes in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One, 10(7), e0131802. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W. , & Zhu, J. (2014). Emotional expression and emotional recovery in high school students. Psychological Research, 7(6), 80–84. 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1159.2014.06.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.