Abstract

Aim

To investigate the effectiveness of different dressings on pressure injuries and screen the dressings for efficacy.

Design

Systematic review and network meta‐analysis.

Methods

Articles published from several electronic databases and other resources were selected. Two reviewers independently selected studies, extracted data and assessed the quality of selected studies.

Results

Twenty‐five studies that contained data on moist dressings (hydrocolloidal dressing, foam dressing, silver ion dressing, biological wound dressing, hydrogel dressing, polymeric membrane dressing) and sterile gauze dressings (traditional gauze dressings) were included. All RCTs were at a medium to high risk of bias. Moist dressings were found to be more advantageous than the traditional dressings. Hydrocolloid dressings [RR = 1.38, 95% CI (1.18, 1.60)] showed a higher cure rate than sterile gauze dressing and foam dressings [RR = 1.37, 95% CI (1.16, 1.61)]. Silver ion dressings [RR = l.37, 95% CI (1.08, 1. 73)] showed a higher cure rate than sterile gauze dressings. Sterile gauze dressing dressings [RR = 0.51, 95% CI (0.44, 0.78)] showed a lower cure rate compared with polymeric membrane dressings; whereas Sterile gauze dressing dressings [RR = 0.80, 95% CI (0.47, 1.37)] had a lower cure rate compared to biological wound dressings. Foam and hydrocolloid dressings were associated with the least healing time. Few dressing changes were required for moist dressings.

Keywords: dressings, efficacy, network meta‐analysis, pressure injury

1. INTRODUCTION

Pressure injuries (PIs) are localized injuries to the skin and/or underlying tissue, also known as pressure sores, decubitus ulcers and bedsores. They are usually caused by chronic pressure or friction between the soft tissue at the bony prominence and the outer surface (Mervis & Phillips, 2019; Nazerali et al., 2010). PI can cause tissue necrosis, pain, sepsis, decreased mobility and more (Pittman & Gillespie, 2020). The quality of life of the patient also gets affected. Furthermore, prolonged hospital stays of PI patients reduce bed availability for other patients (Eisenbud et al., 2003; Mulder et al., 1993). PIs are common in patients that are bedridden for long term mainly because of medical procedures or compression by medical devices (Banks et al., 1999). PIs if not treated in time, can easily cause wound infection, affect the prognosis and increase the length of hospital stay and the medical cost. PIs cause physical and psychological pain to patients and form a public economic health problem that deserves the attention of the majority of medical and health personnel (Meaume et al., 2005; Stephen‐Haynes, 2012; Walker et al., 2017).

Pressure injuries and their treatment are some of the most challenging clinical problems in medicine (Kamoun et al., 2017). Therefore, one of the top priorities for clinical nurses is to find reliable treatments for PIs (Bouza et al., 2005; Heyneman et al., 2008). At present, local treatment of PIs mainly includes various types of wound dressings to promote wound healing, help in wound debridement, avoid bacterial infection and prevent further damage (Huang et al., 2015). Recent studies have focused on various types of dressings for PI treatment. Many types of dressings are available; however, consensus on their therapeutic effect has not been reported yet (Pott et al., 2014).

The aim of the present study was to collate the available evidence from RCTs in a network meta‐analysis for the following purposes: (1) to assess the relative efficacy of different types of dressings for the treatment of PIs in adults;(2) and rank all types of available dressings in order of their effect on PI treatment.

2. METHODS AND ANALYSIS

2.1. Ethics statement

The present meta‐analysis was based solely on previously published studies, with no original individual patient data and thus did not require ethical approval.

2.2. Information sources and search strategy

Digital databases including PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure were used for the search. All the search results from the date of inception of each database to May 2022 were included. Additionally, we explored the bibliographies of relevant reviews to identify other potentially eligible studies. The literature search terms and strategies included ‘Pressure Ulcer’ [Mesh] OR pressure ulcer*[Title/Abstract] OR pressure sore*[Title/Abstract] OR decubitus ulceration[Title/Abstract] OR decubitus ulcer*[Title/Abstract] OR bed sore*[Title/Abstract] OR bedsore*[Title/Abstract] OR decubital ulcer*[Title/Abstract] OR ‘ulcers decubitus’ [Title/Abstract]; ‘Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic’ [Mesh] OR randomized controlled trial[Publication Type] OR ‘random*[Title/Abstract]’; ‘Bandages’ [Mesh] OR ‘Bandages, Hydrocolloid’ [Mesh] OR ‘Occlusive Dressings’ [Mesh] OR ‘Honey’ [Mesh] OR ‘Hydrogels’ [Mesh] OR ‘Alginates’ [Mesh] OR ‘Negative‐Pressure Wound Therapy’ [Mesh] OR ‘Silver’ [Mesh] OR ‘Silver Sulfadiazine’ [Mesh] OR ‘Collagenases’ [Mesh] OR Bandage*[Title/Abstract] OR dressing*[Title/Abstract] OR gauze[Title/Abstract] OR tulle[Title/Abstract] OR film*[Title/Abstract] OR bead[Title/Abstract] OR Pad*[Title/Abstract] OR hydrocolloid*[Title/Abstract] OR ‘sodium hyaluronate’ [Title/Abstract] OR alginate*[Title/Abstract] OR hydrogel*[Title/Abstract] OR silver*[Title/Abstract] OR honey*[Title/Abstract] OR Foam*[Title/Abstract] OR ‘non adherent’ [Title/Abstract] OR matrix[Title/Abstract] OR Collagenase*[Title/Abstract] OR foam*[Title/Abstract] OR non‐adherent[Title/Abstract]’. The searching strategy and syntax were shown in Table S1. The present study was conducted according to the Cochrane Collaboration and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses 2009 guidelines for meta‐analysis and systematic review (Liberati et al., 2009).

2.3. Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Participants: patients with PIs; Interventions: dressings were used as a treatment method in both the experimental group and the control group. Studies that included the following outcomes were considered: Primary outcome measures: cure rate, healing time. Secondary outcome measures: number of dressing changes; studies: only randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Exclusion criteria included: poor quality of literature, duplicate publications, conference papers/abstracts and intervention with a combination of dressings.

2.4. Study selection and data collection

Titles and abstracts were screened, and data were extracted from the included studies by two reviewers independently and strictly according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Standardized data collection tables were used to extract the data from the included studies. Complete texts were read if the information given in the title or abstract did not pass the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by considering the opinion of a third reviewer. We collected data on patients' baseline characteristics (age and sex) and the interventions/comparators used in each study.

2.5. Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of the included RCTs was evaluated independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by considering the opinion of a third reviewer.

The present study assessed the quality of the literature according to the recommended risk of bias assessment tool, Cochrane 5.1.0. The quality was evaluated based on the following seven parts: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, researchers, outcome assessment, completeness of outcome measures, selective reporting and other sources of bias. Each section was rated as ‘high risk of bias’, ‘unclear bias’ or ‘low risk of bias’. See Table S2.

2.6. Statistical analysis

2.6.1. Data synthesis

Stata 16.0 was used for data processing and analysis and to draw related graphs (Shim et al., 2017). We calculated the standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous variable data, and the relative risk (RR) with 95% CIs for dichotomous variable data. The number of iterations for the initial and continuous update of the model was set to 10,000. The first 10,000 annealing times were used to eliminate the influence of the initial value, and sampling was started after 10,001 times. A consistency model was used to estimate relative effects. Subsequently, we calculated the relative rankings of the intervention groups and presented the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) percentages. For any outcome, we performed a network meta‐analysis only if the intervention groups could be connected to form a network; however, we did not exclude comparisons of support surfaces assigned to the same group from the overall systematic review.

2.6.2. Assessment of the certainty of evidence

We judged the risk of publication bias by assessing the completeness of the literature search (i.e. examining the extent of the literature search and assessing the amount of unpublished data located), and plotting the funnel plot for each pairwise meta‐analysis that included more than 10 studies and a comparison‐adjusted funnel plot for the network.

3. RESULTS

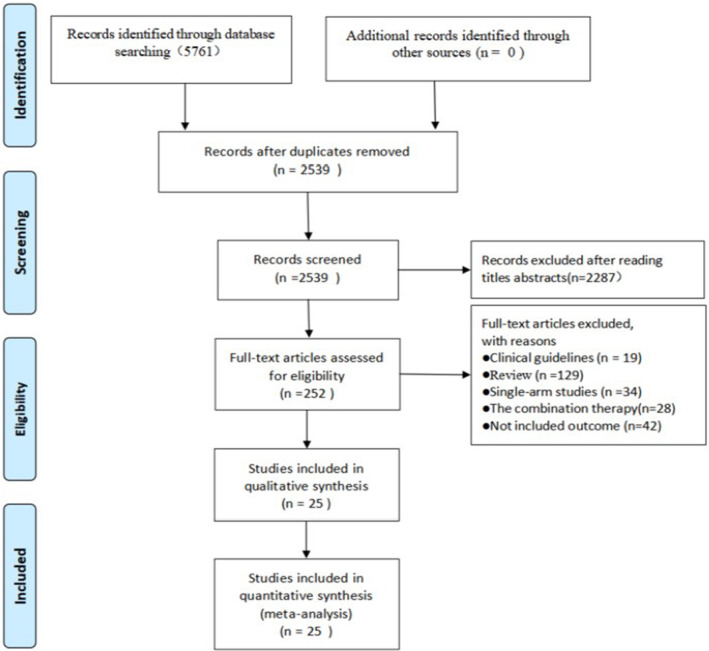

Figure 1 summarizes the literature review process. We identified relevant studies by initial screening that involved reading titles and abstracts. For a comprehensive search and to prevent omission, we used an extensive search strategy to retrieve as many eligible RCT studies as possible. Therefore, it seems unlikely that relevant trials were missed. The search identified 5761 records. After a full‐text screening of 252 potentially eligible studies, 25 studies were included; eight were published in English and 17 in Chinese. All the participating authors agreed with the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this study.

FIGURE 1.

Literature review flowchart.

Table 1 presents the baseline demographic characteristics and interventions reported in the 25 included trials, which included a total of 1730 patients. The trials were conducted between 1994 and 2019. The mean age range of patients for all studies was 35.0–81.0 years (One study report lacked patient baseline age data).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Country | Intervention | Sample | Age, mean (SD) | Gender (male/female) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXP | CON | EXP | CON | EXP | CON | |||

| Zhang (2019) | China | Foam dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 10 | 10 | 39.90 ± 11.20 | 40.75 ± 11.66 | 6/4 | 5/5 |

| Lu and Su (2018) | China | Foam dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 43 | 42 | 69.5 ± 6.8 | 69.3 ± 6.9 | 25/18 | 26/16 |

| Chen (2013) | China | Foam dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 15 | 15 | 66–99 | 9/21 | ||

| He (2019) | China | Hydrocolloidal dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 44 | 44 | 72.36 ± 2.06 | 72.38 ± 2.08 | 28/16 | 27/17 |

| Pan et al. (2013) | China | Foam dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 46 | 46 | 53–91 | 58/34 | ||

| Chen et al. (2017) | China | Silver ion dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 42 | 42 | 71.48 ± 3.25 | 70.89 ± 3.17 | 23/19 | 22/20 |

| Li (2019) | China | Hydrocolloidal dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 39 | 39 | 80.12 ± 3.8 | 81.32 ± 3.24 | 20/19 | 29/10 |

| Huang et al. (2017) | China | Hydrocolloidal dressing vs. foam dressing | 30 | 30 | 21–92 | 38/22 | ||

| Yang et al. (2014) | China | Biological wound dressing vs. foam dressing | 30 | 30 | 64.3 ± 3.4 | 64.6 ± 2.7 | 16/14 | 18/12 |

| Wang (2014) | China | Silver ion dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 26 | 26 | 47.6–76.5 | 47.3–75.3 | 14/12 | 15/11 |

| Chu et al. (2012) | China | Foam dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 43 | 40 | 70 ± 2.7 | 69.0 ± 2.5 | 42/41 | |

| Luo et al. (2009) | China | Hydrocolloidal dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 26 | 26 | 50.15 ± 7.86 | 37/15 | ||

| Pi et al. (2014) | China | Foam dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 56 | 56 | 55.0 ± 3.8 | 54.0 ± 4.2 | 34/22 | 31/25 |

| Li (2015) | China | Silver ion dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 20 | 20 | 67–93 | 22/16 | ||

| Zhang et al. (2019) | China | Hydrocolloidal dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 56 | 56 | 47.25 ± 11.62 | 46.82 ± 11.54 | 28/28 | 26/30 |

| Wu et al. (2013) | China | Silver ion dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 20 | 22 | 66.78 ± 14.21 | 23/31 | ||

| Banks et al. (1994) | English | Foam dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 26 | 24 | — | 18/32 | ||

| Sebern (1986) | USA | Polymeric membrane dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 37 | 40 | 76.3 ± 17.6 | 72.4 ± 17.9 | — | |

| Thomas et al. (1998) | USA | Hydrogel dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 16 | 14 | 79 ± 9 | 72 ± 13 | 7/9 | 9/5 |

| Kim et al. (1996) | Korea | Hydrocolloidal dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 26 | 18 | 50.5 ± 18.3 | 46.9 ± 16.8 | 23/3 | 13/5 |

| Bale et al. (1997) | English | Foam dressing vs. hydrocolloidal dressing | 29 | 31 | 73 | 74 | 12/17 | 15/16 |

| Hollisaz et al. (2004) | Iran | Hydrocolloidal dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 31 | 30 | 36.81 ± 6.71 | 36.6 ± 6.17 | — | |

| Brown‐Etris et al. (2008) | USA | Polymeric membrane dressing vs. hydrocolloidal dressing | 35 | 37 | 78.3 ± 14.70 | 72.7 ± 18.61 | 13/22 | 19/18 |

| Hondé et al. (1994) | France | Polymeric membrane dressing vs. hydrocolloidal dressing | 80 | 88 | 80.4 ± 8.2 | 83.5 ± 7.8 | 54/26 | 67/21 |

| Kordestani et al. (2008) | Iran | Biological wound dressing vs. sterile gauze dressing | 32 | 22 | 45.8 | 41.2 | — | |

Abbreviations: EXP, experiment group; CON, control group; SD, standard deviation.

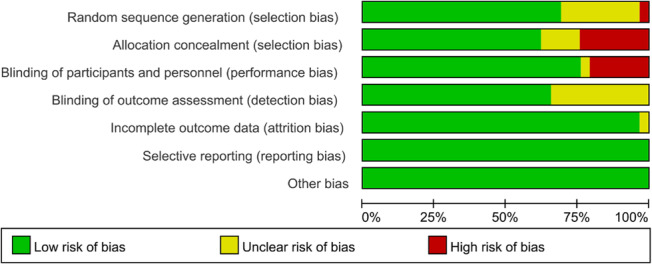

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias for the included studies. Out of the 25 included RCTs, 14 were considered to have a low risk of bias, and 11 studies were considered to have a moderate risk of bias. The risk of bias was primarily due to undocumented details regarding the management of blinding, allocation concealment or missing data.

FIGURE 2.

Quality assessment risk table.

3.1. Cure rate

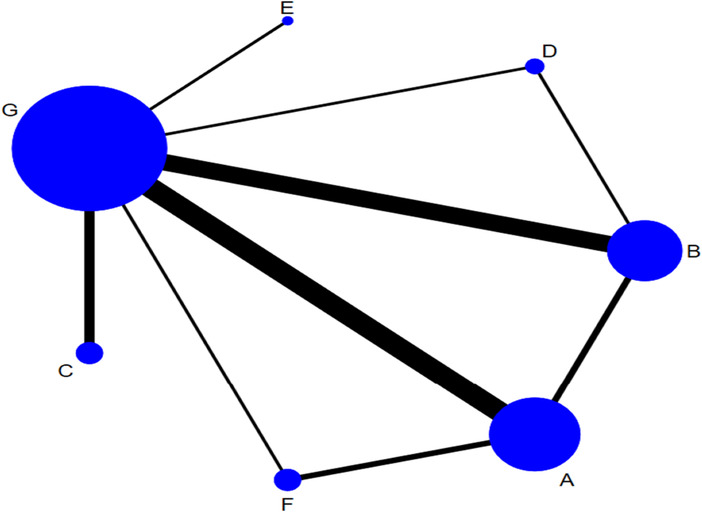

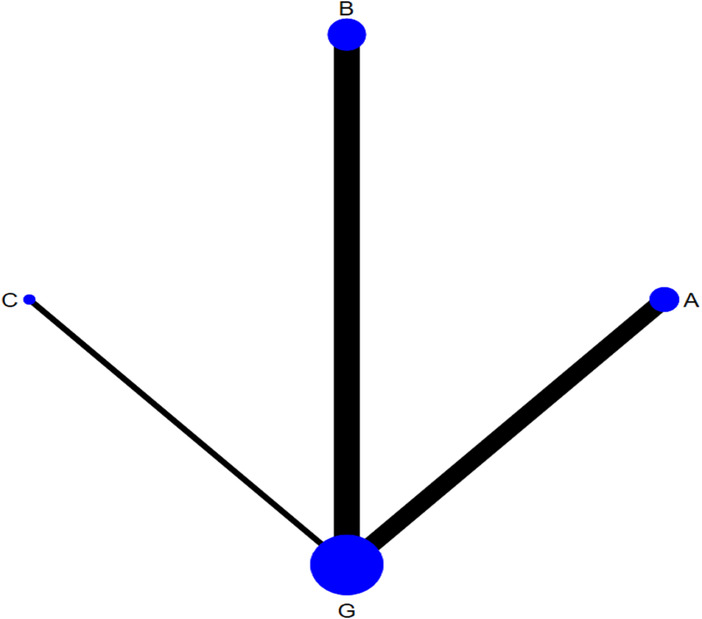

The network of eligible comparison for the efficacy of the different dressings is presented in Figure 3. Taking G as the centre, the size of the dots represents the sample size of the intervention and the thickness of the connecting line between each measure represents the number of RCTs that used two‐point treatment. A large number of closed loops were observed. Except for treatments E and C, the other treatments formed a closed loop. (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Network plot of different types of dressings for the network meta‐analysis. (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; D, biological wound dressing; E, hydrogel dressing; F, polymeric membrane dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

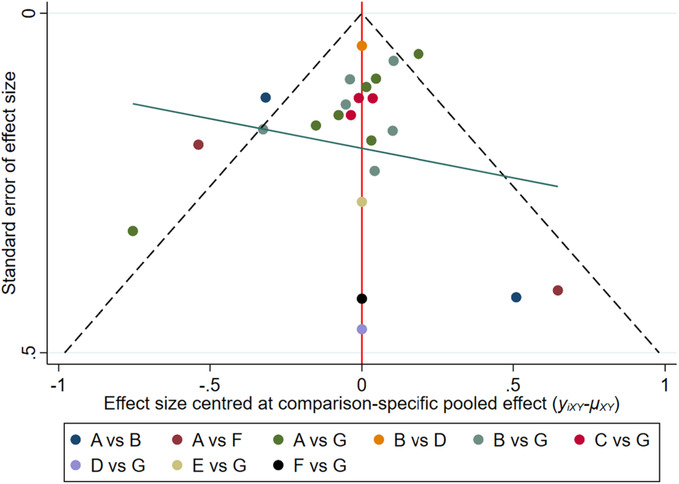

Twenty‐four RCTs reported cure rates including interventions with dressings such as: foam dressings, sterile gauze dressing, hydrocolloid dressings, silver ion dressings, biological wound dressings and hydrogel dressings. The results of the mesh meta‐analysis are shown in Table 2. The cure rate of foam dressing was higher compared with that of sterile gauze dressing [RR = 1.37, 95% CI (1.16, 1.61)]; the cure rate of hydrocolloidal dressing and silver ion dressing was higher than that of sterile gauze [RR = 1.38, 95% CI (1.18, 1.60)], [RR = 1.37, 95% CI (1.08, 1.73), respectively]; sterile gauze dressing failed to show any difference in cure rates compared to hydrogel dressing; compared with sterile gauze, the cure rate of biological wound dressing and polymeric membrane dressing was higher [RR = 1.58, 95% CI (1.06, 2.37)], [RR = 1.97, 95% CI (1.29, 3.00)]; no statistical difference was observed when compared with the control groups. Nodal analysis was performed to assess the intervention measures, and the results showed an absence of inconsistency between the direct and indirect results of each intervention (p > 0.05). Owing to the comparative adjustment of the funnel results, all studies were basically within the inverted funnel and the additional Egger's test p‐value was >0.05, suggesting that our study may not involve publication bias (Figure 4).

TABLE 2.

Influence of different dressings on healing of PIs. (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; D, biological wound dressing; E, hydrogel dressing; F, polymeric membrane dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

| A | ||||||

| 1.01 (0.83, 1.22) | B | |||||

| 1.01 (0.76, 1.34) | 1.00 (0.75, 1.33) | C | ||||

| 0.87 (0.58, 1.30) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.23) | 0.86 (0.54, 1.38) | D | |||

| 1.42 (0.74, 2.71) | 1.41 (0.73, 2.69) | 1.41 (0.72, 2.75) | 1.63 (0.77, 3.43) | E | ||

| 0.70 (0.47, 1.04) | 0.70 (0.45, 1.07) | 0.70 (0.43, 1.13) | 0.80 (0.47, 1.37) | 0.49 (0.23, 1.05) | F | |

| 1.38 (1.18, 1.60) | 1.37 (1.16, 1.61) | 1.37 (1.08, 1.73) | 1.58 (1.06, 2.37) | 0.97 (0.52, 1.82) | 1.97 (1.29, 3.00) | G |

Note: Bold values indicates a statistical difference between pairwise comparisons.

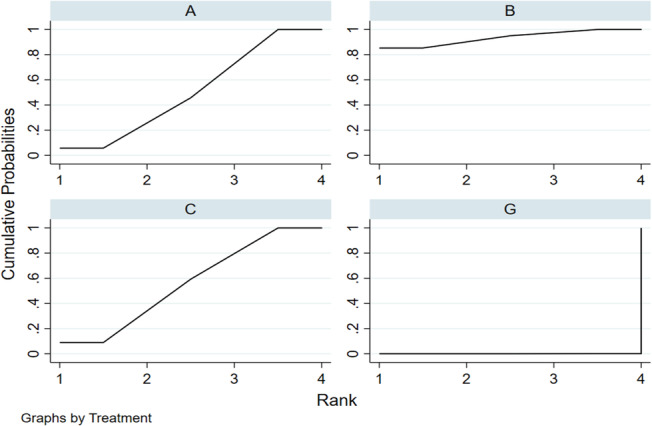

FIGURE 4.

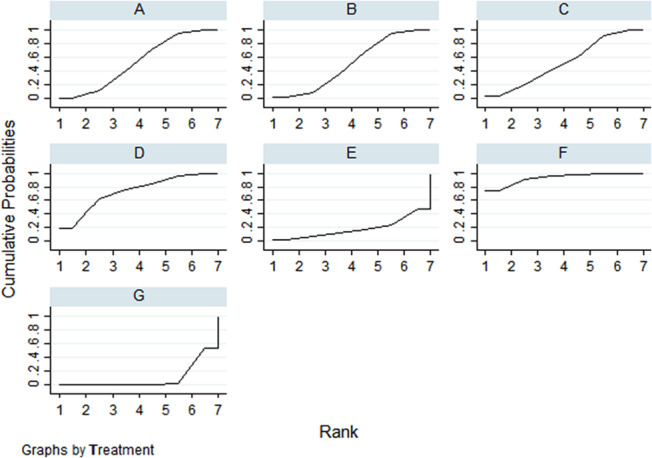

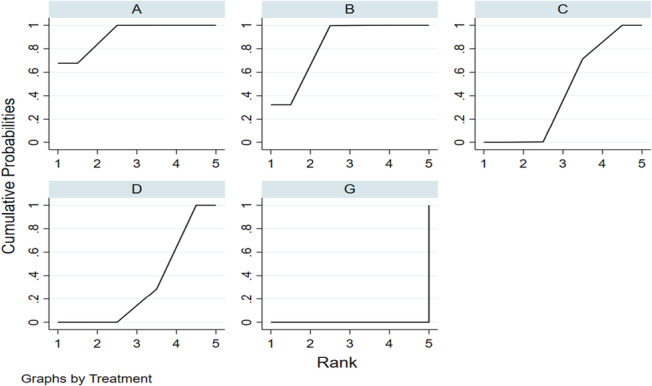

The SUCRA line drawn for ranking the dressings. (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; D, biological wound dressing; E, hydrogel dressing; F, polymeric membrane dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

According to the p values in the ranking chart and the results of the network meta‐analysis, the order of dressings according to the cure rate from high to low was: polymeric membrane dressing, biological wound dressing, hydrocolloidal dressing, silver ion dressing, foam dressing, hydrogel dressing and sterile gauze dressing. (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Funnel plot of Cure rate. (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; D, biological wound dressing; E, hydrogel dressing; F, polymeric membrane dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

3.2. Healing time

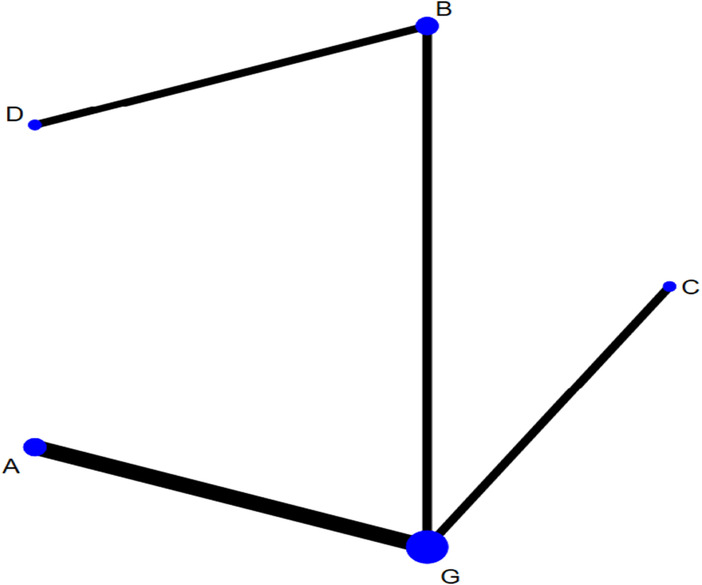

The network of eligible comparisons for testing the efficacy of the different dressings is presented in Figure 6. Considering G as the centre, the size of the dots represents the sample size of the intervention and thickness of the connecting line between each measure represents the number of RCTs using the two‐point treatment. A closed loop could not be formed because the number of studies included was small (Figure 7).

FIGURE 6.

Network plot of healing time for the network meta‐analysis (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

FIGURE 7.

The SUCRA line drawn for ranking the dressings. (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

Eight RCTs reported healing time and included interventions of: foam dressings, hydrocolloid dressings, sterile gauze and silver ion dressings. The results of the network meta‐analysis are shown in Table 3: compared with sterile gauze, foam dressing was associated with shorter healing time [SMD = −1.09, 95% CI (−1.67, −0.50)]; moreover, compared with sterile gauze dressing, silver ion dressing and hydrocolloid dressings were associated with shorter healing times [SMD = −1.16, 95% CI (−1.82, −0.51), SMD = −2.00, 95% CI (−3.14, −0.86)]. No significant statistical difference was observed among other interventions. Node analysis showed the absence of inconsistency between the direct and indirect results of each intervention (p > 0.05). Funnel plot to assess publication bias was not drawn as less than 10 studies were included.

TABLE 3.

Influence of different dressings on healing time of PIs.(A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

| C | |||

| −0.84 (−2.15, 0.48) | A | ||

| −0.91 (−2.20, 0.37) | −0.08 (−0.96, 0.80) | B | |

| −2.00 (−3.14, −0.86) | −1.16 (−1.82, −0.51) | −1.09 (−1.67, −0.50) | G |

Note: Bold values indicates a statistical difference between pairwise comparisons.

The results of the network meta‐analysis were combined with the p values to compare the healing time for various types of dressings used in the treatment of PIs. The ascending order based on healing time can be given as follows: silver ion dressing, hydrocolloidal dressing, foam dressing and sterile gauze.

3.3. Number of dressing changes

The network of eligible comparisons for testing the efficacy of the different dressings is presented in Figure 8. Considering G as the centre, the size of the dots represents the sample size of the intervention and the thickness of the connecting line between each measure represents the number of RCTs that used two‐point treatment. A closed loop could not be formed.

FIGURE 8.

Network plot of number of dressing changes for the network meta‐analysis. (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; D, biological wound dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

Five RCTs reported the number of dressing changes and included the following types of dressings: hydrocolloidal dressing, foam dressing, silver ion dressing, biological wound dressing and sterile gauze dressing. One of the interventions in the RCT was silver ion dressing and biological wound dressing, which failed to form a mesh with other dressings. The results of a separate analysis are shown in (Table 4): compared with hydrocolloidal dressing, foam dressing, sterile gauze dressing and biological wound dressing could reduce the number of dressing changes [SMD = −2.29, 95% CI (−3.46, −1.12)], [SMD = −2.02, 95% CI (−2.78, −1.26)], [SMD = −3.90, 95% CI (−4.95, −2.84)], respectively. The results of the network meta‐analysis showed that compared with gauze, the use of hydrocolloid dressing reduced the number of dressing changes [SMD = −1.61, 95% CI (−2.11, −1.10)], while sterile gauze, foam dressing and silver ion dressing reduced the number of dressing changes [SMD = −3.57, 95% CI (−4.44, −2.70)] and [SMD = −1.88, 95% CI (−2.61, −1.14)]. No statistically significant difference was observed among other interventions. According to the ranking chart, p value and the results of network meta‐analysis, the order of dressing type based on the number of dressing changes required in ascending order was as follows: biological wound dressing, silver ion dressing, foam dressing, hydrocolloid dressing and sterile dressing (Figure 9).

TABLE 4.

Influence of different dressings on number of dressing changes for the treatment of PIs.(A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; D, biological wound dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

| D | ||||

| −0.33 (−1.70, 1.04) | C | |||

| −2.02 (−2.78, −1.26) | −1.69 (−2.83, −0.55) | B | ||

| −2.29 (−3.46, −1.12) | −1.96 (−2.97, −0.95) | −0.27 (−1.16, 0.62) | A | |

| −3.90 (−4.95, −2.84) | −3.57 (−4.44, −2.70) | −1.88 (−2.61, −1.14) | −1.61 (−2.11, −1.10) | G |

Note: Bold values indicates a statistical difference between pairwise comparisons.

FIGURE 9.

The SUCRA line drawn for ranking the dressings. (A, hydrocolloidal dressing; B, foam dressing; C, silver ion dressing; D, biological wound dressing; G, sterile gauze dressing).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, the effects of different dressings on PIs were analysed by adjusting for indirect comparisons and mixed treatment effect analysis (Stephen‐Haynes, 2012). The results showed that moist dressings were superior to traditional sterile gauze and sterile gauze dressing dressings in terms of cure rate, healing time and number of dressing changes required. Although the results of our analysis can help clinicians make decisions related to dressing selection when treating PIs, selection must be done carefully (Meaume et al., 2005). The variety of treatments currently available in healthcare settings, contextual factors, such as patient preferences and type of health insurance, should also be considered while selection (Mervis & Phillips, 2019). Moist dressings should be used for wound healing compared to traditional dressings in consideration of the effectiveness of treatment methods.

Cure rate is an important indicator for efficacy of dressings for PI, thus it is an important factor for dressing selection. The present study found that compared with a sterile gauze dressing, foam dressing and hydrocolloid dressing could improve the PI cure rate (Boyko et al., 2018). In contrast, previous reviews had shown that it was not clear that foam dressings were more effective than sterile gauze dressing because of low‐quality evidence (Westby et al., 2017). Compared with sterile gauze, hydrocolloidal dressing, foam dressing, silver ion dressing, biological wound dressing and polymeric membrane dressing have more advantages in terms of the PI cure rate. However, no statistical difference was observed in the cure rate of different types of moist (Reddy et al., 2006). According to the ranking results, the polymeric membrane dressing had the best cure rates for PI among the moist dressings (Bluestein & Javaheri, 2008). Studies have shown that the polymeric membrane dressings could effectively treat PI and significantly improve the cure rate. Clinical studies verify that polymeric membrane dressing use leads to a significant decrease in pain, bruises and inflammation and speeds up healing of both open and closed tissue injuries (Benskin, 2018). Owing to the limited number of original studies included in the network meta‐analysis based on the number of PI wounds, the lack of comparison of biological wound dressings and lack of a closed loop between interventions, a consistency test could not be performed. The results of this part of the study are provided only as a supplementary reference (Laat et al., 2006). Overall, the results of the network meta‐analysis based on the number of PI wounds were consistent with the results of the network meta‐analysis based on the number of PI patients' reliability.

Healing time is also a factor affecting the effectiveness of dressings. The shorter the healing time, the lesser burden PI imposes on the patient. The results of the network meta‐analysis showed that silver ion dressings required the shortest time for PI healing. Silver ion dressing is a non‐occlusive dressing that can absorb wound exudate and form a mesh‐like gel on the wound surface, creating a slightly acidic, anaerobic and moderately moist healing environment for the wound that can promote the release of growth factors, thereby shortening healing time. Silver ion dressings are preferred by clinical nurses for the treatment of PIs. Medical workers consider cost is an important factor while choosing dressings. The use of hydrocolloidal dressings involves the lowest direct costs, but reports of relevant outcomes in the included RCTs were few and involved only four dressings. The economic results for foam dressings, hydrocolloid and biological wound dressings were not available and hence they could not be assessed in terms of direct costs. The method for the nursing expenses may have been different in different studies and the sample size that we analysed was not large; therefore, the analysis of the results is only for reference. The number of dressing changes is related to the workload of clinical nurses, and an increase in the number of dressing changes increases the work pressure of nurses. Studies have shown that patients with PI experience pain when the dressings are changed. Therefore, the number of dressing changes is one of the bases for selecting the type of moist dressing. The results of the network meta‐analysis performed in the present study showed that the number of dressing changes was minimal when biological wound dressings were used. However, our results need to be verified further as we considered only a few types of dressings and analysed a small sample.

Our study assessed the outcomes related to dressing effectiveness and comfort. The analysis of outcomes of RCTs performed in the present study was more comprehensive than that reported in the previous studies. Additionally, this study used the latest bias risk assessment tool recommended by Cochrane to evaluate the quality of the included studies and conducted consistency, publication bias and sensitivity analysis to judge the reliability of the outcome indicators. The RCTs included in this study have a certain risk of bias and include dressings of different manufacturers; therefore, the components of dressings might be slightly different. The reported treatment cycles were also inconsistent, and most of the RCTs did not report stages of PIs, which may have some impact on the outcome. Because there may be differences in the type of dressing applied for different pressure ulcer types, there was considerable uncertainty in the ranking of interventions, and the results need to be interpreted with caution. In future, a large, multi‐centre randomized controlled trial should be carried out to verify the conclusions of this study.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Compared to traditional dressings, moist dressings performed better in all outcome measures. The use of moist dressings improved cure rate, reduce healing time and the number of dressing changes. The polymeric membrane dressing showed the highest cure rate for PI. Combining the advantages and disadvantages of dressings for each outcome index, polymeric membrane dressing and silver ion dressing were effective for the treatment of PIs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.Z. and H.C.: conceptualization; C.Z., K.Z. and S.Z.: methodology; C.Z. and B.W.: formal analysis; S.Z. and B.W.: investigation; S.Z. and B.W.: data curation; C.Z. and H.C.: writing—review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study received no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was based on previously published studies; therefore, ethical approval and patient consent were not required.

Supporting information

Table S1.

Table S2.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Yan Li for her expert advice during the writing of the manuscript.

Zhang, C. , Zhang, S. , Wu, B. , Zou, K. , & Chen, H. (2023). Efficacy of different types of dressings on pressure injuries: Systematic review and network meta‐analysis . Nursing Open, 10, 5857–5867. 10.1002/nop2.1867

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Bale, S. , Squires, D. , Varnon, T. , Walker, A. , Benbow, M. , & Harding, K. G. (1997). A comparison of two dressings in pressure sore management. Journal of Wound Care, 6(10), 463–466. 10.12968/jowc.1997.6.10.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks, V. , Bale, S. , & Harding, K. G. (1994). Superficial pressure sores: Comparing two regimes. Journal of Wound Care, 3(1), 8–10. 10.12968/jowc.1994.3.1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks, V. , Hagelstein, S. , Thomas, N. , Bale, S. , & Harding, K. G. (1999). Comparing hydrocolloid dressings in management of exuding wounds. British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing), 8(10), 640–646. 10.12968/bjon.1999.8.10.6600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benskin, L. L. (2018). Evidence for polymeric membrane dressings as a unique dressing subcategory, using pressure ulcers as an example. Advances in Wound Care, 7(12), 419–426. 10.1089/wound.2018.0822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestein, D. , & Javaheri, A. (2008). Pressure ulcers: Prevention, evaluation, and management. American Family Physician, 78(10), 1186–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouza, C. , Saz, Z. , Muñoz, A. , & Amate, J. M. (2005). Efficacy of advanced dressings in the treatment of pressure ulcers: A systematic review. Journal of Wound Care, 14(5), 193–199. 10.12968/jowc.2005.14.5.26773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko, T. V. , Longaker, M. T. , & Yang, G. P. (2018). Review of the current management of pressure ulcers. Advances in Wound Care, 7(2), 57–67. 10.1089/wound.2016.0697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown‐Etris, M. , Milne, C. , Orsted, H. , Gates, J. L. , Netsch, D. , Punchello, M. , Couture, N. , Albert, M. , Attrell, E. , & Freyberg, J. (2008). A prospective, randomized, multisite clinical evaluation of a transparent absorbent acrylic dressing and a hydrocolloid dressing in the management of stage II and shallow stage III pressure ulcers. Advances in Skin & Wound Care, 21(4), 169–174. 10.1097/01.ASW.0000305429.01413.f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. (2013). The efficacy of Kanghuier dressing in the treatment of stage III pressure ulcers. Clinical Medicine, 33(1), 124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. X. , Mo, M. H. , Lu, Y. Y. , & Chen, J. B. (2017). Application of nano‐silver medical antibacterial dressing combined with comfortable nursing in the treatment and nursing of senile stage III pressure ulcers. Nursing Practice and Research, 14(9), 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W. Y. , Wu, N. , Li, Y. H. , Zhang, C. J. , & Wu, S. F. (2012). Curative effect observation of 43 cases of stage II pressure ulcer treated with Youjie foam dressing. Journal of Guangdong Medical College, 30(5), 543–544. [Google Scholar]

- de Laat, E. H. , Schoonhoven, L. , Pickkers, P. , Verbeek, A. L. , & van Achterberg, T. (2006). Epidemiology, risk and prevention of pressure ulcers in critically ill patients: A literature review. Journal of Wound Care, 15(6), 269–275. 10.12968/jowc.2006.15.6.26920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbud, D. , Hunter, H. , Kessler, L. , & Zulkowski, K. (2003). Hydrogel wound dressings: Where do we stand in 2003? Ostomy/Wound Management, 49(10), 52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, C. Y. (2019). The effect of Kanghuier hydrocolloid dressing on wound healing of stage 2 pressure ulcers in elderly patients. China Medical Engineering, 27(6), 72–74. 10.19338/j.issn.1672-2019.2019.06.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heyneman, A. , Beele, H. , Vanderwee, K. , & Defloor, T. (2008). A systematic review of the use of hydrocolloids in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(9), 1164–1173. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollisaz, M. T. , Khedmat, H. , & Yari, F. (2004). A randomized clinical trial comparing hydrocolloid, phenytoin and simple dressings for the treatment of pressure ulcers [ISRCTN33429693]. BMC Dermatology, 4(1), 18. 10.1186/1471-5945-4-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondé, C. , Derks, C. , & Tudor, D. (1994). Local treatment of pressure sores in the elderly: Amino acid copolymer membrane versus hydrocolloid dressing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 42(11), 1180–1183. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06985.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. , Woo, K. Y. , Liu, L. B. , Wen, R. J. , Hu, A. L. , & Shi, C. G. (2015). Dressings for preventing pressure ulcers: A meta‐analysis. Advances in Skin & Wound Care, 28(6), 267–273. 10.1097/01.ASW.0000463905.69998.0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. Q. , Li, Y. , & Lu, L. L. (2017). Observation on the effect of hydrocolloid transparent paste and foam dressing in the treatment of stage I pressure ulcers. Contemporary Nurses (Mid‐Journal), 12, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun, E. A. , Kenawy, E. S. , & Chen, X. (2017). A review on polymeric hydrogel membranes for wound dressing applications: PVA‐based hydrogel dressings. Journal of Advanced Research, 8(3), 217–233. 10.1016/j.jare.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. C. , Shin, J. C. , Park, C. I. , Oh, S. H. , Choi, S. M. , & Kim, Y. S. (1996). Efficacy of hydrocolloid occlusive dressing technique in decubitus ulcer treatment: A comparative study. Yonsei Medical Journal, 37(3), 181–185. 10.3349/ymj.1996.37.3.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordestani, S. , Shahrezaee, M. , Tahmasebi, M. N. , Hajimahmodi, H. , Haji Ghasemali, D. , & Abyaneh, M. S. (2008). A randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness of an advanced wound dressing used in Iran. Journal of Wound Care, 17(7), 323–327. 10.12968/jowc.2008.17.7.30525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. (2019). Observation on the efficacy of hydrocolloid dressing in the treatment of secondary pressure ulcers in elderly patients. China Geriatric Health Medicine, 17(5), 124–125+130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. C. (2015). Observation of the curative effect of Yubang antibacterial dressing in the treatment of stage III pressure ulcers. Contemporary Nurses (Mid‐Journal), 2015(9), 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A. , Altman, D. G. , Tetzlaff, J. , Mulrow, C. , Gøtzsche, P. C. , Ioannidis, J. P. , Clarke, M. , Devereaux, P. J. , Kleijnen, J. , & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339, b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q. X. , & Su, C. F. (2018). Feasibility study of De wet skin foam dressing in the nursing of elderly stage III pressure ulcer. Electronic Journal of Practical Clinical Nursing, 3(13), 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H. Y. , Guo, S. M. , & Shen, Y. (2009). Observation on the effect of 3M hydrophilic dressing (artificial skin) on patients with pressure ulcers. Sichuan Medicine, 30(5), 778–779. [Google Scholar]

- Meaume, S. , Colin, D. , Barrois, B. , Bohbot, S. , & Allaert, F. A. (2005). Preventing the occurrence of pressure ulceration in hospitalised elderly patients. Journal of Wound Care, 14(2), 78–82. 10.12968/jowc.2005.14.2.26741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervis, J. S. , & Phillips, T. J. (2019). Pressure ulcers: Pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 81(4), 881–890. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, G. D. , Altman, M. , Seeley, J. E. , & Tintle, T. (1993). Prospective randomized study of the efficacy of hydrogel, hydrocolloid, and saline solution‐moistened dressings on the management of pressure ulcers. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 1(4), 213–218. 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1993.10406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazerali, R. S. , Song, K. R. , & Wong, M. S. (2010). Facial pressure ulcer following prone positioning. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 63(4), e413–e414. 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X. L. , Li, Y. B. , & Huang, Y. Z. (2013). Observation on the curative effect of Mepilokang dressing in the treatment of stage II and superficial stage III pressure ulcers. Nursing Practice and Research, 21(12), 158. [Google Scholar]

- Pi, Y. , Shen, W. L. , & Wang, L. (2014). Observation on the efficacy of 3M polyester foam dressing in the treatment of stage I pressure ulcers in critically ill patients. Modern Medicine and Health, 30(16), 2424–2426. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, J. , & Gillespie, C. (2020). Medical device‐related pressure injuries. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 32(4), 533–542. 10.1016/j.cnc.2020.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pott, F. S. , Meier, M. J. , Stocco, J. G. , Crozeta, K. , & Ribas, J. D. (2014). The effectiveness of hydrocolloid dressings versus other dressings in the healing of pressure ulcers in adults and older adults: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Revista Latino‐Americana de Enfermagem, 22(3), 511–520. 10.1590/0104-1169.3480.2445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, M. , Gill, S. S. , & Rochon, P. A. (2006). Preventing pressure ulcers: A systematic review. JAMA, 296(8), 974–984. 10.1001/jama.296.8.974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebern, M. D. (1986). Pressure ulcer management in home health care: Efficacy and cost effectiveness of moisture vapor permeable dressing. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 67(10), 726–729. 10.1016/0003-9993(86)90004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim, S. , Yoon, B. H. , Shin, I. S. , & Bae, J. M. (2017). Network meta‐analysis: Application and practice using Stata. Epidemiology and Health, 39, e2017047. 10.4178/epih.e2017047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen‐Haynes, J. (2012). Pressure ulceration and palliative care: Prevention, treatment, policy and outcomes. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 18(1), 9–16. 10.12968/ijpn.2012.18.1.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D. R. , Goode, P. S. , LaMaster, K. , & Tennyson, T. (1998). Acemannan hydrogel dressing versus saline dressing for pressure ulcers. A randomized, controlled trial. Advances in Wound Care: The Journal for Prevention and Healing, 11(6), 273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R. M. , Gillespie, B. M. , Thalib, L. , Higgins, N. S. , & Whitty, J. A. (2017). Foam dressings for treating pressure ulcers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10(10), CD011332. 10.1002/14651858.CD011332.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. (2014). Observation on the nursing effect of silver ion antibacterial dressing in the treatment of stage III pressure ulcers in urology. China Health Industry, 11(19), 67–68. 10.16659/j.cnki.1672-5654.2014.19.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westby, M. J. , Dumville, J. C. , Soares, M. O. , Stubbs, N. , & Norman, G. (2017). Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6(6), CD011947. 10.1002/14651858.CD011947.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Q. , Lu, S. S. , Jin, L. L. , & Xu, Y. (2013). Application and effect observation of silver ion antibacterial dressing in pressure ulcer infected wounds. Chinese journal of hospital Infectious Diseases, 23(9), 2079–2081. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D. M. , Qin, P. , Wang, L. , & Ren, H. (2014). Observation on the curative effect of medical invisible antibacterial film in the treatment of stage II and III pressure ulcers. Southwest National Defense Medicine, 24(5), 520–522. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Z. , Li, Y. M. , & Xiong, J. C. (2019). Observation on the effect of refined nursing combined with Kanghuier hydrocolloid dressing in stage II pressure ulcers. Journal of Qiqihar Medical College, 40(10), 1318–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. X. (2019). Application and effect of Bayertan foam dressing in pressure ulcer care. World Latest Medical Information Digest, 19(25), 251. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Table S2.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.