Abstract

STING activation has considerable potential as a new strategy for cancer therapy, but clinical results have not been encouraging. Recent studies explain why STING agonists often fail to regress human tumors and propose combinatorial strategies to overcome the pro-tumor effects of STING activation.

Keywords: chromosome instability, IL6, regulatory B cells, IL35

The cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS) −STING (stimulator of interferon genes) pathway activates the type I interferon response (see Glossary), leading to induction of cell death or growth inhibition. For this reason, cGAS/STING has been implicated as a cell-intrinsic tumor suppressor-like pathway. In addition, STING activates antigen-presenting cells, induces pro-inflammatory cytokines, and primes cytotoxic T cells. Therefore, STING agonists – chemicals that mimic the enzymatic products of cGAS, have the potential to serve as effective cancer therapies. Indeed, in pre-clinical studies, intra-tumoral administration of STING agonists – analogs of endogenous cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) – robustly induces tumor regression and generates a profound systemic immune response [1]. Surprisingly, monotherapy with STING agonists in patients with advanced cancer has rather limited clinical benefit, resulting in a certain degree of disappointment [2]. Now two recent studies uncover vastly different mechanisms which might render STING agonist therapy insufficient to stop tumor growth [3,4]

Previous studies on the tumor cell intrinsic roles of cGAS/STING in the background of chromosome instability (CIN) have revealed a tumor suppressor-like role for cGAS/STING. For example, induction of micronuclei in mouse embryonic fibroblasts activates cGAS and upregulates the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) [5]. Similarly, in mammary epithelial cells, gamma irradiation triggers, within 3–6 days, a cGAS/STING-mediated type I interferon response characterized by induction of both total and phosphorylated STAT1 protein [6]. Notably, these studies indicate that an interferon response requires cells to be cycling and undergoing mitosis to generate micronuclei in order to activate cGAS (Figure 1A–B), though the adequacy of micronuclei for cGAS activation is currently controversial. A recent study found that chromosome bridges, instead of micronuclei, are necessary for cGAS activation induced by mitotic inhibitors such as taxanes and spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) kinase inhibitors [7].

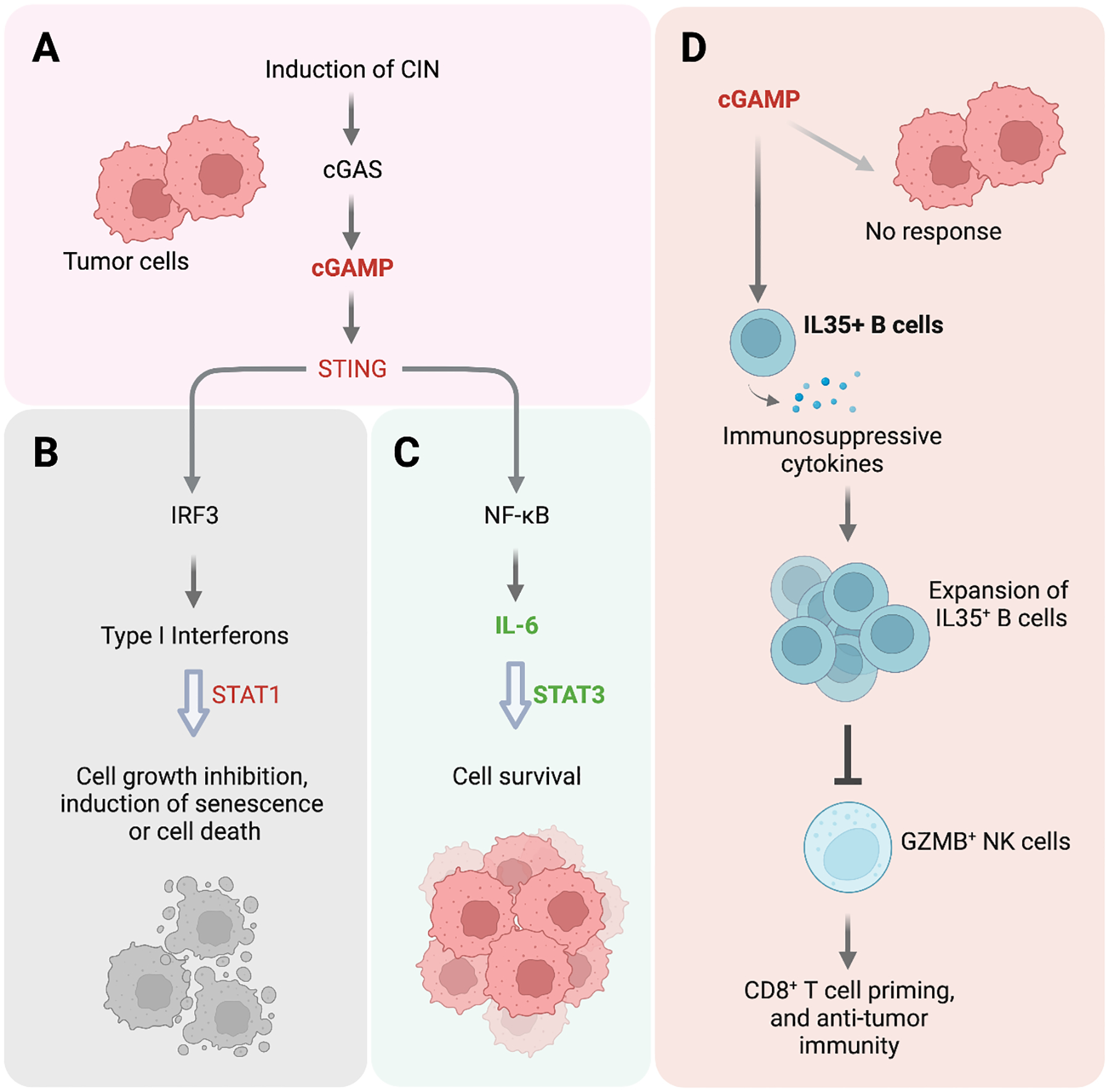

Figure 1.

Pleiotropic effects of STING activation in tumor and immune cells. (A) Exposing tumor cells to radiation, DNA-damaging agents, or mitotic inhibitor can induce chromosome instability (CIN), which results in cGAS/STING activation. (B) A classic outcome of cGAS/STING activation in tumor cells is IRF3-mediated production of type I interferons – cytokines that induce cancer cell death, growth inhibition or cell senescence. (C) In breast tumor cell lines, Hong et al. uncover a noncanonical NFκB response upon CIN-induced cGAS/STING activation that competitively promotes cell survival via IL6, IL6R, and STAT3. (D) In pancreatic tumor cells, Liu et al. find that STING agonist in the tumor microenvironment spares tumors cells and selectively targets IL35+ B cells. STING activation stimulates the expression of IL35 and other immunosuppressive cytokines, leading to the activation and proliferation of IL35+ B cells which in turn repress NK cells to reduce anti-tumor immunity and promote tumor cell survival.

In stark contrast to the notion of cGAS/STING as tumor suppressors (Figure 1B), in a recent study, Hong et al. show that cGAS/STING promotes the survival of cancer cells upon exposure to mitotic inhibitors (i.e. G2 checkpoint or SAC kinase inhibitors) and subsequent induction of chromosomal instability and micronuclei [3]. Consistent with previous findings, inflammatory gene expression, including that of interferon and NFκB signaling, is compromised in cGAS-knockout cells [5,6]. Intriguingly, though, cGAS-knockout cells treated with mitotic inhibitor for 2 or 3 days are more prone than control cells to apoptotic cell death, suggesting that cGAS/STING-driven inflammatory signaling likely promotes cell survival in response to CIN. The authors further determine that depleting downstream transcription factors STAT3 or the non-canonical NFκB member RELB promotes CIN-associated cell death similarly to cGAS depletion, suggesting that these factors might mediate the pro-survival effect of cGAS/STING (Figure 1C).

Furthermore, Hong et al. demonstrate that STAT3 is coupled to non-canonical NFκB via IL6/IL6R signaling. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL6 is known to activate STAT3 signaling, and CIN induction in cancer cells increases IL6 expression. In fact, the authors find that IL6 induction requires CIN-induced cGAS/STING and downstream non-canonical NFκB, because it can be prevented by knocking out cGAS, STING, or RELB. Additionally, the growth of the knockout cells with CIN can be rescued by treatment with exogenous IL6. Therefore, IL6 is a key downstream effector that promotes cell growth via STAT3 in the presence of CIN (Figure 1C).

Conversely, an IL6R inhibitor reduces the viability of cancer cells with CIN, presenting an actionable vulnerability. Of note, IL6R inhibition exhibits potent and selective efficacy in vivo in CIN high, mouse xenograft models versus their CIN low counterparts. In line with the findings of Hong et al., a recent study shows that the cancer drug doxorubicin also activates IL6-STAT3 in a STING-dependent manner [8]. Whether various other forms of DNA damage can induce CIN and activate pro-survival signals remains to be investigated in detail, but the findings of the two studies may proffer the idea that DNA damage-inducing therapies, including chemotherapeutics and radiation, could synergize with IL6R inhibition to effectively target a wide array of tumor types.

An interesting question can also be asked about the effect of CIN on cell growth inhibition. How can cells losing cGAS/STING and, therefore, the downstream pro-survival IL6-STAT3 and pro-cell death interferon-STAT1, be more sensitive to CIN-induced cell death? The concurrent loss of the two opposing pathways may not be sufficient, unless the pro-survival pathway happens to be more dominant. In this case, losing the pro-survival signal could outweigh the loss of pro-cell death signaling driven by interferon. Still, is there another possible explanation for how CIN might induce cell death? This result perhaps implicates the involvement of another cGAS/STING-independent mechanism, one that could also be limited by the activation of IL6-STAT3 signaling downstream of cGAS/STING.

Hong et al. convincingly show that IL6R inhibitors have the potential to attack CIN-high cancers, and the study reveals a previously underappreciated, pro-survival effect of cGAS/STING activation. Would such a role for cGAS/STING in cancer cells cause uncertainty for therapies based on STING activation? While this question largely remains to be addressed, another recent study adds a new layer of complexity to the use of STING agonist as an effective cancer therapy.

Driven by a lack of clinical efficacy of STING agonist therapy, Li et al. investigate the underlying mechanism through the use of mouse tumor models, and they narrowed the “culprit” down to a subset of B cells in the tumor microenvironment that inadvertently promote cancer cell survival [4]. In this study, systemic administration of cGAMP fails to impact the growth of transplanted mouse tumor cells. Profiling immune cells led to the observation that B cells – both their percentage among all tumor-associated immune cells and their absolute number in the tumor – were increased upon STING agonist treatment. Remarkably, depleting the Sting alleles in mouse B cells greatly impaired tumor growth. This would suggest that cGAS/STING activity in B cells, similar to its activity in cancer cells with CIN, can promote tumor growth in vivo.

Mechanistically, the authors find that STING agonists promote the proliferation of a subset of B cells by inducing the expression of mouse Ebi3 – a gene that encodes a subunit of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL35 (Figure 1D). Furthermore, induction of Ebi3 transcription by STING agonists depends on IRF3, but not type I interferon. Even more intriguingly, STING agonists cause the expansion of IL35+ B cells but not IL35+ T cells, marking a cell-type-specific behavior of STING activation. In human B cells as well, STING agonists promote the expression of immunosuppressive genes such as EBI3, an effect that is more pronounced in B cells isolated from pancreatic cancer patients than from healthy individuals.

How does the induction of IL35+ B cells by STING agonist ultimately impact tumor growth? The authors find that upon STING agonist treatment, mice with B cell-specific depletion of Ebi3 have more granzyme B-positive natural killer (NK) cells in the tumor microenvironment than control mice (Figure 1D). Notably, administering anti-IL35 on top of a STING agonist increases NK cell proliferation to reduce tumor volume and increase animal survival. It remains to be examined how exactly IL35+ B cells interact with NK cells and regulate their activity.

The studies of both Hong et al. and Li et al. suggest that a STING agonist by itself might not be an effective cancer therapy. This is owing to the potential pro-survival effect of cGAS/STING activation mediated by IL6-STAT3 – a mechanism discovered by Hong et al. in the context of CIN induction, and because the agonist may activate immunosuppressive B cells, which in turn inhibit NK cells to alter anti-tumor immunity. Nevertheless, these studies propose new, exciting targets – such as IL6R and IL35, whose inhibition could contribute profoundly to the control of tumor growth.

Even so, how does cGAS/STING activation have such a pleiotropic effect – a mixture of pro-cell death and pro-survival effects in tumor cells and actions that manifest in certain cells but not others (such as IL35+ B cells but not T cells expressing the same immunosuppressive cytokine)? Notably, cGAS/STING activity can mediate T cell death, possibly in an interferon-independent manner [9]. Still, a STING agonist was able to regress tumors in certain syngeneic tumor models but not others [1]. Understanding how STING activation works in tumor cells as well as non-tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment (e.g. immune and stromal cells) presents an array of interesting biological questions for which the answers might contribute to the development of STING agonist-based cancer therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Tao Zou (Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) for fruitful discussion. T.M.R. acknowledges funding by NIH grant R35 CA231945. Y.W. acknowledges funding by the Eleanor and Miles Shore Faculty Development Awards Program of Harvard Medical School.

GLOSSARY

- Type I interferon response

type I interferons such as interferon-β are induced in response to cytosolic, foreign (e.g. virus) or host nucleic acids. After secretion, type I interferons bind to their receptors on the cell membrane to initiate signal transduction and to induce gene expression

- NFκB

a family of transcription factors that activate the expression of inflammatory cytokines. The founding member of NFκB was discovered as a nuclear factor interacting with the enhancer for the gene encoding immunoglobin kappa light chain in B cells. The canonical NF-κB complex is a heterodimer of p50 (encoded by NFKB1) and RELA, while the non-canonical complex consists of p52 (encoded by NFKB2) and RELB

- STAT1

signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) drives gene transcription upon activation by kinases associated with interferon receptors. STAT1 forms a complex with STAT2 and IRF9 to drive the transcription of type I interferon response genes, while STAT1 dimer responds to type II interferon (i.e. interferon-γ). The STAT family also includes STAT3, a transcription factor whose activation often promotes cell survival

- IRF3

interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) is a transcription factor that is stimulated by the activation of nucleic acid sensors. After translocating to the nucleus, IRF3 drives the expression of type I interferons

- Granzyme B-positive natural killer cells

a type of innate immune cells that is capable of releasing cytotoxic granules that contain protease Granzyme B into target cells (e.g. tumor cells) to induce cell death

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

T.M.R. is a founder of Crimson Biotech, Crimson Biotech China, and Geode Therapeutics. Y.W consulted for Guidepoint Global.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corrales L, Glickman LH, McWhirter SM, Kanne DB, Sivick KE, Katibah GE, Woo SR, Lemmens E, Banda T, Leong JJ and Metchette K, 2015. Direct activation of STING in the tumor microenvironment leads to potent and systemic tumor regression and immunity. Cell reports, 11(7), pp.1018–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meric-Bernstam F, Sweis RF, Hodi FS, Messersmith WA, Andtbacka RH, Ingham M, Lewis N, Chen X, Pelletier M, Chen X and Wu J, 2022. Phase I dose-escalation trial of MIW815 (ADU-S100), an intratumoral STING agonist, in patients with advanced/metastatic solid tumors or lymphomas. Clinical Cancer Research, 28(4), pp.677–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong C, Schubert M, Tijhuis AE, Requesens M, Roorda M, van den Brink A, Ruiz LA, Bakker PL, van der Sluis T, Pieters W and Chen M, 2022. cGAS–STING drives the IL-6-dependent survival of chromosomally instable cancers. Nature, 607(7918), pp.366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, Mirlekar B, Johnson BM, Brickey W, Wrobel JA, Yang N, Song D, Entwistle S, Tan X, Deng M and Cui Y, 2022. STING-induced regulatory B cells compromise NK function in cancer immunity. Nature, pp.1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie KJ, Carroll P, Martin CA, Murina O, Fluteau A, Simpson DJ, Olova N, Sutcliffe H, Rainger JK, Leitch A, Osborn RT, Wheeler AP, Nowotny M, Gilbert N, Chandra T, Reijns M, & Jackson AP (2017). cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature, 548(7668), 461–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding SM, Benci JL, Irianto J, Discher DE, Minn AJ, & Greenberg RA (2017). Mitotic progression following DNA damage enables pattern recognition within micronuclei. Nature, 548(7668), 466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn PJ, Koch PD and Mitchison TJ, 2021. Chromatin bridges, not micronuclei, activate cGAS after drug-induced mitotic errors in human cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(48), p.e2103585118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasiyani H, Mane M, Rana K, Shinde A, Roy M, Singh J, Gohel D, Currim F, Srivastava R, & Singh R (2022). DNA damage induces STING mediated IL-6-STAT3 survival pathway in triple-negative breast cancer cells and decreased survival of breast cancer patients. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death, 27(11–12), 961–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Dobbs N, Yang K, & Yan N (2020). Interferon-Independent Activities of Mammalian STING Mediate Antiviral Response and Tumor Immune Evasion. Immunity, 53(1), 115–126.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]