Abstract

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) establishes latency in sensory neurons, a state in which the viral lytic genes are silenced and only the latency locus is transcriptionally active, producing the 2.0- and 1.5-kb latency-associated transcripts (LATs). Previous experimental evidence indicates that the LATs are stable introns, and it has been reported that LAT formation is abolished by debilitating substitution mutations in the predicted splice sites during lytic infection but not latency (J. L. Arthur et al., J. Gen. Virol. 79:107–116, 1998). We have independently studied a set of deletion mutations to explore the roles of the proposed splice sites during lytic and latent infection. HSV-1 mutant viruses missing the invariant intron-terminal 5′-G(T/C) or 3′-AG dinucleotides were analyzed for LAT formation during lytic infection in vitro, when only the 2-kb LAT is produced, and during latency in mouse trigeminal ganglia, where both LATs are expressed. Northern blot analysis of total RNAs from different productively infected cell lines showed that the lytic (2-kb) LAT was not expressed by the various splice site deletion mutants. In vivo studies using a mouse eye model of latency similarly showed that the latent (2- and 1.5-kb) LATs were not expressed by the mutants. PCR analysis with primers flanking the LAT sequence revealed the expected splice junction for LAT excision in RNA from sensory neurons latently infected with wild-type but not mutant virus. Using a virus mutant deleted in the splicing signals flanking the 556-bp region of LAT whose absence distinguishes the 1.5- and 2-kb LATs, we observed selective elimination of 1.5-kb LAT expression in latency, supporting previous suggestions that the internal region is removed by splicing. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the 2-kb LAT is formed during both lytic and latent infection by splicing at the predicted splice sites and that an additional splicing event is involved in the latency-restricted production of the 1.5-kb LAT. We have also mapped the 3′ end of the lytic 2-kb LAT and discuss our results in the context of previous models addressing the unusual stability of the LATs.

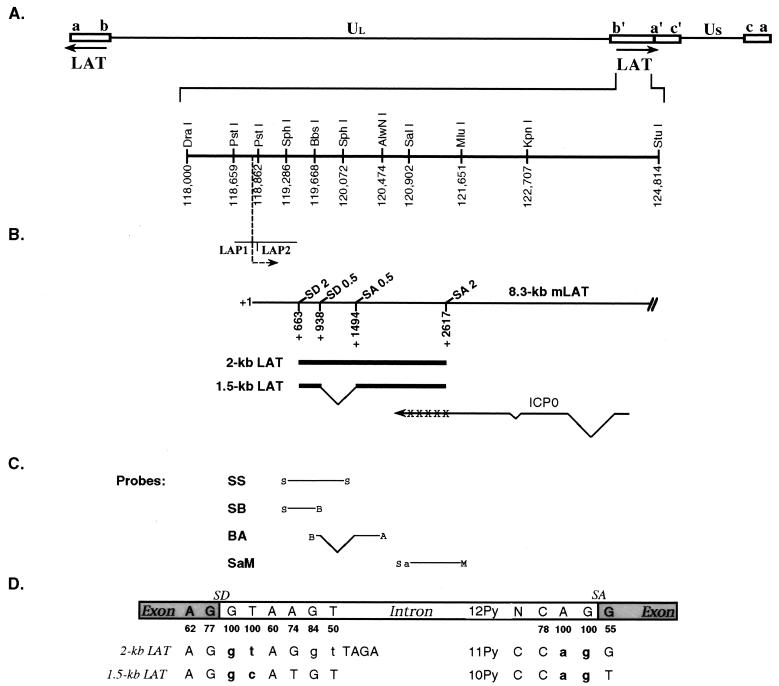

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) establishes a latent state in neurons persisting for the life of the host, with occasional reactivation (65). During latency, viral gene expression is extremely limited with the exception of two to three abundant, largely intranuclear transcripts encoded by the latency-associated transcript (LAT) loci in the repeats flanking the unique long (UL) region of the viral genome (Fig. 1) (33, 34, 51, 61–63). The most abundant LAT is a 2-kb RNA that is also expressed as a late gene product during lytic infection (47, 50). The second LAT is a latency-specific 1.5-kb RNA that is colinear with the 2-kb LAT except for an internal 556-nucleotide (nt) deletion between canonical pre-mRNA splicing signals, demonstrating that it is a spliced version of the larger LAT (Fig. 1B) (52, 56). A third LAT, occasionally detectable in latently infected neuronal cells, is believed to be a structural variant of the 1.5-kb LAT (68). The LATs do not contain large open reading frames, and thus far a LAT-encoded protein has not been detected in latently infected neurons (15), but the unique stability and expression of the LATs suggest that these RNA molecules serve regulatory functions in the establishment and maintenance of latency or reactivation from latency (48, 53).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the LATs of HSV-1 depicting the locations of probes and splice site mutations. (A) The LAT genes in the inverted repeats flanking UL and the positions of relevant restriction sites based on the published sequence of HSV-1 strain 17+ (44). (B) The minor 8.3-kb (mLAT) and major 2.0- and 1.5-kb LATs, transcribed from left to right, overlap with the ICP0 transcript transcribed off of the opposite strand. The positions of the two LAT promoters, LAP1 and LAP2, are indicated. Also diagrammed are the start site (nt 118801) and direction of transcription. Crosses over the ICP0 mRNA represent the region of complementarity to the major LATs that is read out of frame in the splice acceptor mutant; the arrowhead at the end of the mRNA indicates the direction of transcription. The positions of the canonical splice donor (SD) and splice acceptor (SA) sites potentially involved in the generation of the major LATs (2.0 and 1.5 kb) are also shown. (C) Locations of the probes used for Southern and Northern blot analysis. S, SphI; B, BbsI; A, AlwNI; Sa, SalI; M, MluI. (D) Alignment of the LAT splicing signals with eukaryotic consensus sites. The splice donor and splice acceptor consensus sequences are shown in boxes representing two exons (shaded) and an intron (open); the frequencies of these consensus nucleotides among vertebrate splice site sequences are listed underneath as percentages (35). The canonical splicing signals bounding the 2-kb LAT and the presumed internal intron (1.5-kb LAT) are shown below in alignment with the consensus sequences; the invariant dinucleotides at the intron-terminal positions are in boldface. The bases deleted in the splice site mutant viruses of this study are shown in lowercase. Py, pyrimidine; N, any nucleotide.

Published studies indicate that the LATs are stable introns excised from a pre-mRNA that also gives rise to an unspliced, low-abundance 8.3-kb mRNA termed mLAT (Fig. 1B) (13, 18, 39, 73). The major 2- and 1.5-kb LATs are located 663 bp downstream of the mLAT transcription start site, which is controlled by an upstream LAT promoter (LAP) (14, 73). We previously referred to this promoter as LAP1 since we reported the existence of a second promoter, LAP2, located immediately upstream of the 2-kb LAT region (10, 24). Abundant LAT production during latency is dependent on the activity of LAP1 (10, 14, 41), which is consistent with an intronic origin for these RNAs. Other observations supporting a splicing model for LAT production are the demonstration that the LATs are neither capped nor polyadenylated (13), in contrast to mLAT, that their shared coding sequences are flanked by canonical splice site signals, that their 5′ ends map almost precisely to the predicted splice donor site (52, 62), and that they are nonlinear molecules with characteristics typical of the branched intron products (lariats) of conventional pre-mRNA splicing (reviewed in references 4 and 19). In addition, studies using LAT minigene constructs and lacZ/LAT chimeric constructs have shown that both 2-kb LAT and an exonic product spliced at the canonical splice sites are generated in transiently transfected cells, demonstrating that these canonical sites are functional (18, 37). It has also been reported that 2- and 1.5-kb LATs were produced from a lacZ/LAT vector during latency, although it was not demonstrated that these LATs were produced by splicing (59). However, other observations are less supportive of a splicing mechanism. For example, both the stability of the major LATs (37, 46) and their presence in the polyribosomal RNA fraction of transfected (25, 70) and infected (25, 26, 42) cells are highly unusual for excised introns, the predicted exonic splicing product (spliced mLAT) is not readily detectable, and the 3′ ends of the LATs appear to map somewhat upstream of the predicted splice acceptor site rather than to the site itself (46, 52, 68). To reconcile these divergent observations with a splicing mechanism, it has been proposed that (i) spliced mLAT is highly unstable and (ii) the excised introns (i.e., the mature LATs) are stable lariats trimmed by a 3′-exonucleolytic activity up to a structural block variously suggested to be the branch point itself or a stable stem-loop structure that may form near the end of the intron (37, 46, 68, 70).

By using reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) as a sensitive detection procedure, evidence has been obtained that spliced mLAT exists in productively infected cells (70), but this product remains hypothetical in latently infected cells although both the 2.0- and 1.5-kb LATs are abundantly expressed in this situation. The LATs cannot be converted to linear molecules by treatment with standard lariat debranching extract (46, 68), thereby eliminating both a powerful argument for the lariat proposal and a tool to validate branch point mapping results; indeed, efforts to map the presumed LAT branch point have produced conflicting results (67, 70). The 3′ ends of the lytic and latent LATs have been mapped, but not at high resolution (46, 52, 61, 63, 68). While these deficiencies merely illustrate a certain lack of depth in the evidence supporting the splicing model for LAT formation during latency, a recent report by Arthur and coworkers (2) raises the possibility that the latency splicing model is in fact fundamentally flawed. These authors tested the functionality of the predicted splice donor and splice acceptor sites directly by mutating these sites. Surprisingly, their results indicate that the predicted splice sites are dispensable for LAT production during latency, although not during lytic infection.

We have studied an independent set of splice site mutations during lytic infection in vitro and latency in vivo. Our results show that these mutations eliminate LAT expression under both conditions. We have identified spliced mLAT in lytically and latently infected cells by RT-PCR and have found that the splice junction is the same in the two situations and coincides with the predicted splice sites. We observed in both wild-type (wt) and mutant virus-infected cells additional splicing patterns that support the view that the LAT splice sites are ordinary pre-mRNA splicing signals. Mutation of the canonical splice sites flanking the presumed internal 0.5-kb intron abolished the production of the 1.5-kb but not the 2-kb LAT during latency, demonstrating that the external and internal splice sites function independently. By S1 nuclease protection, we have mapped the 3′ end of the lytic 2-kb LAT to positions −24 and −25 relative to the splice acceptor site, and we discuss this finding in relation to LAT branching and stability. Together, our results considerably strengthen the argument that the major LATs in latency are formed by conventional pre-mRNA splicing at the predicted splice sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

African green monkey kidney (Vero), human neuroblastoma (SK-N-SH), and human osteosarcoma (U2OS) cell lines (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (SK-N-SH and U2OS) or Eagle’s minimum essential medium (Vero) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). Wild-type HSV-1 strains 17+ (5), obtained from F. Jenkins (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pa.), and KOS (12) were used in this study. Recombinant viruses were derived from the strain 17 mutant IE-0:lacZ transplacement vector, generously provided by S. Silverstein (Columbia University, New York, N.Y.) in which both copies of the ICP0 gene had been previously replaced with lacZ (9). High-titer stocks of viruses partially defective for ICP0 (2-kb LAT splice acceptor mutants) were prepared by using the ICP0-complementing U2OS cell line (69).

Plasmids.

The 10,137-bp BamHI B fragment from strain 17 was ligated into the unique BamHI site of pUC19 to make p17BB. Construction of pBB, the strain KOS counterpart of p17BB, and pSG28, which contain the EcoRI-EK sequences from KOS, has been previously described (10, 27). The EcoRV-XhoI fragments of pBB and p17BB were subcloned in pBluescript II KS (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) to yield pBST-LATin and pBST-17LATin, respectively. The SalI-AatII fragment of pBST-17LATin was blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and subcloned into the SmaI site of pSP72 (Promega, Madison, Wis.) to create pSP-17LAT(S/A). pBST-LAT-0, a variant of pBST-LATin that includes the region upstream of LAP1 and the balance of the ICP0 locus, was generated by insertion of the AvrII-EcoRV fragment of pBB upstream (into the XbaI/EcoRV sites) and the pSG28 XhoI-Psp1406 I fragment downstream (into the XhoI/Sa I sites) of the insert. The ends produced by Psp1406-I and SapI were filled-in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (New England Biolabs) prior to ligation. pBST-17LAT-0 was engineered by replacement of the KOS sequences between the EcoRV and XhoI sites of BST-LAT-0 with the corresponding sequences from pBST-17LATin. pBST-LAT1.5, derived from pBST-17LATin by site-directed mutagenesis, carries a complete deletion of the internal intron sequences of the 2-kb LAT.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The invariant G(T/C)/AG dinucleotides of the canonical splice sites flanking the 2-kb LAT and at the boundaries of the putative internal intron were deleted by a modified two-sided overlap extension PCR procedure (32). Substrates for overlap extension, top- and bottom-strand intermediates, were synthesized in 20-μl PCR mixtures containing 1× ThermoPol buffer (supplied with the enzyme), 20 pmol of primer, 400 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 140 ng of linearized pBST-LATin, and 0.4 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). Twenty cycles of 100°C for 5 s, 42 to 65°C for 1 to 5 s, and 72°C for 30 to 60 s were performed, and the reaction products were gel purified by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.). Purified intermediates (150 to 200 ng in total) were then combined at different molar ratios (1:1 to 3:1) in 20-μl reaction mixtures containing 1× ThermoPol buffer, 400 μM dNTPs, and 0.4 U of Vent DNA polymerase and extended in five to eight cycles of 100°C for 5 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The full-length product was gel purified and PCR amplified for 15 to 20 cycles with the outer primers as described for the first set of reactions, except that the annealing temperature was held at or above 60°C. The amplified fragment was cleaved at internal restriction sites and substituted for its corresponding sequence in pBST-LATin. Deletion of the 556-bp region of LAT coding for the internal intron was performed in a similar fashion, except that pBST-17LATin was used as the template in the synthesis of the intermediates and as the cloning vector in the final step. For recombination into the virus genome, mutated sequences were subcloned into pBST-LAT-0 (or pBST-17LAT-0 in the case of the 556-bp internal intron deletion).

Construction and screening of recombinant viruses.

SacI-linearized plasmid DNA (20 to 40 μg) and 1 to 10 μg of IE-0:lacZ transplacement vector cotransfected into 60% confluent Vero cell monolayers by calcium phosphate-mediated precipitation (28). Following an overnight incubation in 5% FBS–Dulbecco modified Eagle medium, the cells were overlaid with 15 ml of agarose overlay solution (0.5% low-melting-point-agarose [Life Technologies], minimal essential medium without phenol red [Life Technologies], 5% FBS) and incubated until the appearance of plaques (usually 2 to 4 days). A second overlay of 5 ml containing 350 μl of a 3% solution of neutral red (Life Technologies) and 80 μl of a 30-mg/ml solution of Bluo-Gal (Life Technologies) was then added, and large white plaques were picked and transferred to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes containing 200 μl of growth medium. Plaques were amplified by infection of fresh monolayers in 24-well plates. Infections were harvested at full cytopathic effect, transferred to fresh microcentrifuge tubes, and subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles. Lysates were cleared by a pulse spin, and the supernatants were transferred to fresh microcentrifuge tubes. The virus was concentrated by centrifugation (30 min), resuspended in 50 to 100 μl of digestion buffer (1% Nonidet NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5]), and digested with proteinase K (100 μg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) for 4 h at 56°C. The enzyme was heat inactivated (95°C for 10 min), and a 1- to 2-μl aliquot was used to screen for splice site deletions as follows. Fragments encompassing individual splice sites were amplified by PCR in 20-μl reactions containing [α-32P]dCTP (NEN/Dupont, Wilmington, Del.) or an end-labeled primer and analyzed on denaturing polyacrylamide gels capable of resolving the small size differences (two or four bases) between the mutant and wt fragments. For dl556, which carries a larger deletion (556 bp), native agarose gels were used instead. Marker-rescued viruses positive for the splice site deletions were purified by three rounds of limiting dilution, and the presence of the desired mutation in both copies of LAT, as well as the integrity of the genome, was subsequently verified by Southern hybridization and DNA sequence analysis.

Isolation of viral DNA.

Vero cells (2 × 106 4 × 106) infected at a multiplicity of infection of 3 were harvested by centrifugation at 12 h postinfection (p.i.), washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed overnight at 37°C in lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5]) containing proteinase K (1 mg/ml) (36). RNase A (20 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was then added, and incubation at 37°C was continued for 1 h. Samples were phenol-chloroform extracted and isopropanol precipitated; DNA pellets were washed with 70% ethanol, air dried, and solubilized in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA).

Southern blot analysis.

KpnI digests were resolved on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred to a Nytran Plus membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) overnight by downward capillary transfer (11) in 10× SSC (1.5 M NaCl, 1.5 M sodium citrate). Following UV cross-linking in a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene), the membrane was prehybridized for 4 h and then hybridized overnight at 65°C with a mixture of three 32P-labeled, double-stranded DNA probes (SB [SphI-BbsI and SalI-MluI from pBST-17LATin] and BA [BbsI-AlwNI from pBST-LAT1.5] [Fig. 1C]) in Church buffer (7% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 M sodium phosphate [pH 7.2]). Washes were successively performed in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS, 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS, and 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature for 15 min. In addition, a high-stringency wash was performed in 0.1× SSC–1% SDS at 65°C for 30 to 60 min. All probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a Random Primed DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim).

RNA isolation from productive infections.

Total RNA was isolated from lytically infected Vero, SK-N-SH, or U2OS cells at 8, 12, or 14 h p.i. by direct lysis in 1 ml of TRI Reagent (Sigma) and resuspended in 50 μl of 50% formamide. The RNA was repurified with 1 ml of TRI Reagent and resuspended in 50 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated HES (0.5% SDS, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.2]).

Latent infections and nucleic acid isolation.

The corneas of 5-week-old female BALB/c mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, Ind.) were scarified with a 25-gauge needle and inoculated with 5 μl of virus suspension (2 × 106 PFU). Trigeminal ganglia were then removed at 30 days p.i. and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Nucleic acids were isolated by homogenization in TRI Reagent Isolated DNA was further purified by proteinase K digestion in Hirt lysis buffer for 2 to 4 h at 56°C. DNA was stored in TE (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) and RNA in HES.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA (5 to 10 μg) was fractionated on a 1% agarose–0.4 mM formaldehyde gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. RNA transfer, immobilization, and hybridization were performed exactly as described above for Southern blots. Membranes were also washed as described above. LAT was detected with the 786-bp, 32P-labeled SphI-SphI fragment (SS) of pBST-17LATin (lytic infections) or with the three-probe mixture (SB, SaM, and BA) used for Southern hybridization (latent infections). Following LAT detection, membranes were stripped by being soaked twice at room temperature for 15 min in boiling 0.1× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM NaPO4 [pH 7.7])–0.5% SDS and reprobed for glycoprotein B (lytic infections) with the 969-bp, 32P-labeled BstEII-BstEII fragment of glycoprotein B (gB) or for cyclophilin (latent infections), encoded by a cellular housekeeping gene, with the 641-bp, 32P-labeled PvuII-DrdI fragment of pTRI-cyclophilin-Mouse (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). All probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a Random Primed DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim).

RNA PCR and DNA sequence analysis.

Aliquots of total RNA isolated from lytic and latent infections were repurified with TRI Reagent to remove traces of contaminating DNA and resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), using 2 μg of RNA and 2 pmol of a LAT-specific primer (5′-GCAGGGGCCAAGA-3′) exactly as described in the manufacturer’s protocol except that the RNase inhibitor RNasin (Promega) and annealing/extension temperatures in the range of 45 to 50°C were used. The primer was designed to have a low melting temperature on RNA templates in order to increase its specificity. For PCR, a 100-μl master mix reaction containing 2 μl of heat-inactivated reverse transcription reaction product, 1× PCR buffer (1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.01% gelatin, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]), 200 μM dNTP, 0.2 μM primer (forward/reverse; 5′-TCCATCGCCTTTCCTGTTCTCGCTTCT-3′/5′-CTCCCTGCCTCTTCCTCCTCGG-3), and 5 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim) was first prepared, to minimize pipetting error, and then divided equally into four tubes. Amplification was carried out with the following cycling parameters: 96°C for 2 min followed by 55 to 65 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 66°C for 2 min. The gel-purified reaction product was sequenced with the forward PCR primer, using a CircumVent Thermal Cycle Dideoxy DNA sequencing kit (New England Biolabs).

Quantitative DNA PCR of latent viral genomes.

For analysis of the relative number of latent viral genomes, two viral sequences were coamplified: a 211-bp sequence spanning the splice donor region of the 2-kb LAT (map positions 119382 to 119593) and a 480-bp segment of the DNA polymerase gene (64172 to 64652), with primers (forward and reverse) for LAT (5′-CTCCTCCCTCCCTTCCTCCCCCGTTAT-3′ and 5′-GGGAAAAGAACGGGCTGGTGTGCTGTA-3′) and DNA polymerase (5′-CAGTACGGCCCCGAGTTCGTGAC-3′ and 5′-GTCGTAGATGGTGCGGGTGATGTT-3′). Bulk reactions (100 μl) were assembled by using approximately 600 ng of total cellular DNA, 20 pmol of each primer, and 10 U of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies) and subsequently divided into 25-μl reactions prior to amplification. Twenty-eight cycles (denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and annealing/extension at 68°C for 130 s) were performed on triplicate samples following an initial denaturation step at 96°C for 2 min. A 12-μl aliquot from each reaction was then separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and analyzed by Southern hybridization as described earlier. Blots were probed for LAT, stripped, and reprobed for DNA polymerase. Hybridized blots were exposed to a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, Calif.) PhosphorImager screen, and the signals were quantitated with Imaging Research (St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada) software (MCID3.0 revision 1.2). For each sample, the values obtained with one probe were compared with the corresponding values obtained with the second probe after correction for differences in the lengths and specific activities of the probes. These comparisons demonstrated that the ratio of the values for the two probes was close to the expected ratio of 1 for a majority of the samples, which validated the data. The mean value and standard deviation were calculated for each virus by using the signals from both probes. For comparison between the samples, the mean values were normalized against amplification data for the cellular peripherin gene, encoding a neuron-specific intermediate filament protein (16). A 668-bp fragment of the peripherin gene was amplified in triplicate for 16 cycles with primers 5′-GCAGCAGGTGGAGGTAGAGGCAACAG-3′ (upstream) and 5′-CCGGCTCTCCTCCCCTTCCAGT-3′ (downstream) as described above, except that both the annealing and extension times were shortened by 10 s. All probes were gel-purified, random primer [α-32P]dCTP-labeled PCR fragments identical in size and sequence to the expected amplification products. These probes were chosen over internal 5′-end-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide probes to maximize the sensitivity of the assay after the specificity of each primer pair had been fully optimized and confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

S1 nuclease analysis.

S1 mapping was carried out essentially as described by Berk (3). Briefly, total RNA (20 μg) was hybridized overnight at 65°C with 20 ng of the 3′ end-labeled, 269-bp BspMI-AatII fragment of pBST-17LATin in 50 μl of hybridization buffer [80% (vol/vol) formamide, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.04 M piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES; pH 6.4)] and then digested at 14°C for 1 h or room temperature for 30 min with 10 to 300 U of S1 nuclease (Life Technologies) in 9 volumes of 1× digestion buffer (250 mM NaCl, 1 mM ZnCl2, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 30 mM sodium acetate [pH 4.6]). Reactions were stopped by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, and digestion products were analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel. The A/T sequencing ladder was generated by using BsiWI-linearized pSP17LATS/A and an arbitrarily chosen primer (5′-GGGAGGGAGACAAGA-3) and therefore served only as size standards. The probe was labeled by filling in the ends produced by BspMI with [α-32P]dCTP.

RESULTS

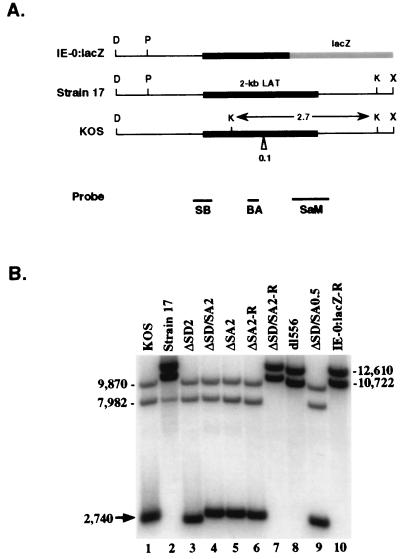

To determine the dependence of 2- and 1.5-kb LAT formation during lytic and latent infections on the consensus splicing signals bounding the 2-kb LAT region and the internal intron (Fig. 1D), we created viruses in which these signals were mutated individually or in pairs. The mutations chosen were deletions of the intron-terminal dinucleotides because these dinucleotides represent the most conserved positions of pre-mRNA splice-site signals (GT or GC for the splice donor and AG for the splice acceptor [Fig. 1D]) and because mutation of these dinucleotides invariably abolishes accurate splicing (1). However, such mutations can result in the selection of aberrant splice sites yielding products that are not easily distinguished on the basis of size from the wild-type product if the normal and aberrant sites are close together. For this reason, we also removed from the outer splice donor sequence a second GT dinucleotide located at positions 5 and 6 relative to the splice site. These deletions were generated by PCR using different combinations of mutant and wild-type primers, and the resulting mutant fragments were used to replace the corresponding wild-type LAT sequences in a plasmid harboring a region from HSV-1 strain KOS that included both the LAT and adjacent ICP0 loci. We created mutant LAT sequences that were deleted for the outer splice donor and splice acceptor individually (ΔSD2 and ΔSA2, respectively) or in combination (ΔSD/SA2), or for the two inner splice sites together (ΔSD/SA0.5). In addition, a fifth LAT mutant that had a precise deletion of the sequences between the two internal splice sites (dl556) was generated. All of these mutated KOS sequences were introduced into the LAT locus of an HSV-1 strain 17 ICP0-null mutant, IE-0:lacZ (9), allowing the identification of interstrain recombinants by blue-white screening. The strain 17 mutant had lacZ in place of ICP0 in both gene copies (Fig. 2A) and formed large blue plaques on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) staining of infected U2OS cells that complement ICP0-defective mutants (69). Interstrain recombinants restoring ICP0 had a growth advantage on noncomplementing Vero cells and produced white plaques on X-Gal staining. Recombinants containing the outer splice acceptor mutation required complementation for efficient growth because this mutation caused a reading-frame shift on the complementary strand in the carboxy-terminal end of ICP0, impairing the function of this regulatory protein. However, these viruses still grew eightfold more efficiently on Vero cells than the parental ICP0-null mutant, as shown by comparative plaque assays (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of virus recombinants deleted for LAT splice donor/acceptor sites. (A) LAT locus of the ICP0 mutant of strain 17 in which the ICP0 coding sequence was replaced by the lacZ gene, removing the 3′ terminus of the LAT intron (9). Unique KpnI (K) and PmlI (P) restriction enzyme sites within the DraI (D) and XhoI (X) fragments of each parental virus that were used to distinguish KOS from strain 17 sequences in the recombinant virus mutants are noted. The KOS LAT intron sequence also contains a 96-bp repeat (indicated as 0.1 at the Δ) resulting from a different copy number of a 16-nt repeat element; strain 17 syn+ contains 9 copies, while KOS contains 15 copies (64). Underneath are the locations of the radiolabeled strain 17 probes (SB, BA, and SaM) used simultaneously for Southern blot analysis of the KpnI digests (see also Fig. 1C and Materials and Methods). (B) Southern blot analysis of the SD/SA mutant viruses. Note that KOS parental virus (lane 1) contains three bands whereas strain 17 and the rescuant IE-0:lacZ-R (lanes 2 and 10, respectively) contain only two slower-migrating specific bands that are larger by ca. 2.7-kb sequence found only in KOS. Lanes 3 to 5 and 9 show the presence of KOS sequences in the 2-kb LAT SD/SA mutants and in the 1.5-kb LAT SD/SA mutant, respectively; lanes 6 and 7 show the virus rescuant patterns; lane 8 shows a faster-migrating strain 17 doublet due to the removal of the 0.5-kb internal intron sequences. Sizes are indicated in nucleotides.

The virus recombinants were subjected to Southern blot analysis to identify recombinants carrying KOS-specific markers in the LAT locus indicating acquisition of the desired splice site mutations, namely, an additional 21 bp immediately downstream of the SphI in the LAP2 promoter, a KpnI site between the inner splice sites, an extended 96-bp repeat sequence downstream of the inner splice acceptor, and the absence of a strain 17-specific PmlI site within LAP1 (Fig. 2A) (54, 64). In the KpnI digests (Fig. 2B), the 2.7-kb fragment indicates the presence of KOS-derived sequences surrounding the two splice acceptor sites (lanes 1, 4, 5, and 9). The virus splice site recombinants analyzed in lanes 4 and 9 also lacked the strain 17-specific PmlI site (data not shown), indicating that the region with the two splice donor sites was also KOS derived and suggesting that these viruses would have the desired splice donor as well as splice acceptor mutations. The ΔSA2 virus (lane 5) contained the upstream PmlI site (not shown), but the markers surrounding the site targeted for mutation were KOS specific. The ΔSD2 virus of (lane 3) lacked the downstream 96-bp repeat sequence from KOS but had the two markers surrounding the targeted splice donor (the KOS-specific KpnI fragment and no upstream PmlI site). The KpnI and PmlI digestion patterns of the dl556 virus (lane 8) were consistent with the intended deletion of the internal intron, reducing the size of one fragment in each digest and lacking the KOS-specific KpnI site inside the internal intron. For each of these interstrain recombinants, the presence of the intended mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown). Figure 2B also shows two of the mutant viruses rescued with wt strain 17 LAT sequences, returning the digestion pattern to strain 17 in one case (lane 7), but not in the other, where the rescue crossover occurred downstream of the KpnI site (lane 6; confirmed by DNA sequencing [data not shown]). Other restriction sites, such as SalI and SphI, were also used to map the KOS/strain 17 crossover boundaries in the recombinant viruses and were found to be consistent with the KpnI digestion results (data not shown).

Effect of LAT splice site mutations on LAT expression during lytic infection.

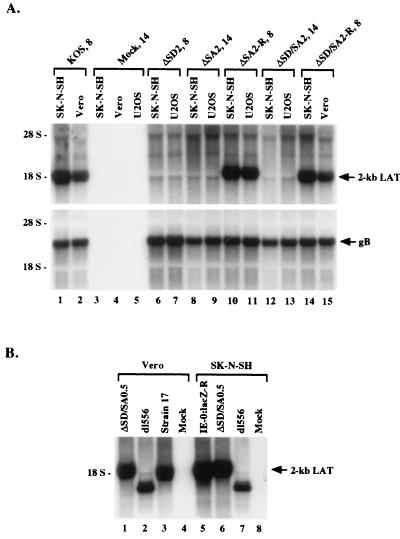

The ability of the deletion mutants to express the 2-kb LAT was evaluated in productively infected U2OS cells, which complement ICP0-defective mutants (69), and SK-N-SH cells, which may provide important neuronal factors for LAT splicing. These cell lines were infected at high multiplicity (multiplicity of infection of 10), and total cellular RNA was extracted 8 or 14 h p.i. Northern blot analysis using a 786-bp LAT-specific probe prepared from an SphI fragment spanning the two splice donor sites (probe SS in Fig. 1C) revealed that expression of the 2-kb LAT, the only LAT observed under these lytic conditions, was dependent on the integrity of the proposed outer splice sites in both cell lines (Fig. 3A, upper panel). While all deletion mutations were highly effective at preventing 2-kb LAT formation, rescuants showed normal LAT expression (Fig. 3A), confirming that the splice site mutations were responsible for the loss of LAT expression by the mutant viruses. Mutation of the two inner splice sites did not have an effect on the formation of LAT (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 6), and deletion of the sequence representing the internal intron (recombinant virus dl556 [Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 7]) did not interfere with the formation of a stable LAT, although this product was now 556 nt smaller than the wild-type 2-kb LAT. Unspliced message, presumably 8.3-kb mLAT, did not accumulate in mutant virus-infected cells (Fig. 3A), which is not surprising given the reported inherent instability of this mRNA (14, 18, 39, 74), and other aberrant products were not observed. The blot was stripped and rehybridized with a probe specific for gB. The constant signal across the lanes (Fig. 3A, lower panel) indicated that the observed differences in 2-kb LAT expression could not be explained by differences in the amount of total RNA in each lane, by the quality of RNAs loaded, or by failure of the splice acceptor/ICP0 mutants to express late genes of which both LAT (true late [γ2]) (10, 13, 50) and gB (early late [βγ or γ1]) are examples. In other experiments, the blot was rehybridized with a probe for the gC gene, a strictly late gene (20, 21, 31), and the results obtained were the same (data not shown). These observations support the proposal that formation of the 2-kb LAT during lytic infection involves splicing at the predicted outer splice sites while demonstrating that it is insensitive to mutations designed to inactivate the predicted internal splice sites.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of total RNAs isolated from productively infected cells in culture. (A) LAT expression from viruses with mutations in the external splice site signals at 8 or 14 h p.i. (indicated by virus names at the top) as visualized by hybridization with LAT-specific probe SS (Fig. 1C). The lower panel shows the stripped blot rehybridized with an HSV-1 gB-specific probe as a control. Virus names ending with −R designate rescued mutants. (B) LAT expression at 12 h p.i., using the SS probe, by a virus with mutated internal splice site signals (lanes 1 and 6) compared with expression from control viruses, including dl556, which has an exact deletion of the internal intron and is seen to produce 1.5-kb LAT under lytic conditions (lanes 2 and 7) instead of 2-kb LAT.

Effect of LAT splice site mutations on LAT expression during latency.

To determine whether the outer splice site mutations would affect 2-kb LAT production during latent infection and whether an effect could be observed for the inner splice site mutations, the wt and mutant recombinant viruses were inoculated onto the scarified cornea of mice, from which the infection can spread to the trigeminal ganglion neurons, where latency is established (55, 58). The ganglia were harvested after 30 days for RNA preparation to measure LAT expression, and DNA was isolated from several samples to compare latency levels by quantitation of viral genomes. Consistent with reports from other laboratories (17, 62), Northern blot analysis (Fig. 4A) showed that KOS-infected ganglia expressed the 2-kb LAT as well as a small amount of 1.5-kb LAT (lane 1) whereas both LATs were expressed abundantly by the strain 17 rescuant IE-0:lacZ-R (lane 9). However, neither LAT was detectable by Northern blotting (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 4) or RT-PCR (data not shown) when the infecting virus had mutations in either or both of the outer splice sites. To test whether this could be due to serious defects in the ability of these mutant viruses to establish latency, we determined the amounts of HSV DNA in infected ganglia for two of the viruses that showed no LAT expression (ΔSD2 and ΔSA2 [Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 4]) and two viruses that expressed 2-kb LAT (ΔSD/SA0.5 [Fig. 4A, lane 8]) or 1.5-kb LAT (dl556 [Fig. 4A, lane 7]) at high levels, similar to strain 17-rescued recombinants (ΔSA2-R and IE-0:lacZ-R [Fig. 4A, lanes 5 and 9]). Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate for two viral genes (see Materials and Methods for details), and the results of all determinations were arbitrarily expressed relative to the mean value calculated for dl556, which was the highest of the four. As shown in Fig. 4B, the differences in latency levels determined in this manner were small compared to the differences in LAT expression between these viruses seen in Fig. 4A. It can be concluded, therefore, that the complete loss of LAT expression by the ΔSD2 and ΔSA2 viruses could not be explained by an impaired ability to establish latency. On the surface, it may be surprising that we did not observe a greater difference in latency levels between the ICP0 wild-type viruses and the ICP0 mutant virus ΔSA2 (Fig. 4B). However, we note that ΔSA2 was able to replicate in noncomplementing Vero cells, although not as efficiently as wild-type virus (see above; data not shown), suggesting that the SA2 mutation altering the final portion of the ICP0 reading frame left the function of ICP0 relatively unimpaired. The lower panel of Fig. 4A demonstrates that the differences in LAT expression between wt and mutant viruses could also not be attributed to differences in the quality or amounts of RNA loaded in each lane. Furthermore, we have confirmed by sequencing of PCR-amplified LAT sequences that the splice site mutations were present in the genomic DNA isolated from mutant virus-infected ganglia (data not shown). Figure 4A also demonstrates that mutation of the presumed inner splice sites selectively abolished production of the 1.5-kb LAT (lane 8), supporting the view that these inner splice sites are critical for the formation of the smaller but not the larger LAT during latency. The sensitivity of this experiment is illustrated in lanes 10 to 12, showing that the limit of detection was at or below 5% of the LAT levels produced by wild-type KOS virus. Together, these results provide strong independent support for the earlier suggestions that the 2-kb LAT is an intron released by splicing at conventional pre-mRNA splice sites and that the 1.5-kb LAT is a variant produced by the same mechanism along with conventional splicing between two internal splice sites.

FIG. 4.

In vivo analysis of LAT expression by the mutant splice site recombinants. (A) Northern blot analysis of LAT expression in latently infected trigeminal ganglia. The probe used for LAT detection was the same as in Fig. 2, i.e., a mixture of probes SB, BA, and SaM (see also Fig. 1). Lanes 10 to 12 show 5-, 10-, and 20-fold dilutions, respectively, of the wt KOS RNA loaded in lane 1 to assess the sensitivity of the experiment. The dl556 mutant (lane 7) produces a LAT species that is 556 nt smaller than wild-type 2-kb LAT. The lower panel displays the ethidium bromide-stained gel prior to transfer demonstrating equal loading of the samples. (B) PCR analysis of latent viral genomes. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed on DNA samples from latently infected trigeminal ganglia, and the results were converted to numbers representing relative levels of latency based on HSV genome abundance (see Materials and Methods for a description of the procedures). DNA from dl556-infected ganglia yielded the highest mean value of triplicate determinations, and this value was arbitrarily set as the standard (100%).

Characterization of splicing products.

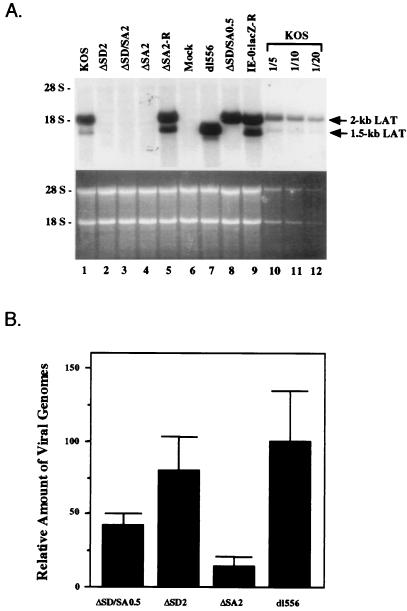

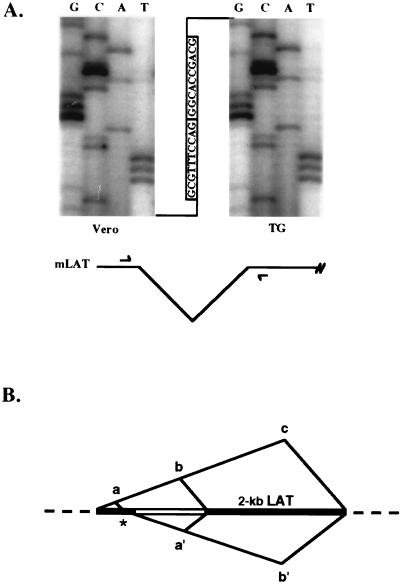

To further strengthen the conclusion that formation of the two major LATs involves splicing between the outer splice sites, experiments were performed to better characterize the predicted exonic and intronic products of this event, namely, the splice junction across the presumed 2-kb intron and the 3′ end of lytic 2-kb LAT. RT-PCR with primers flanking the 2-kb LAT region and sequencing of the single observed product, we obtained evidence that the primary LAT transcript is processed by the removal of an intron between the outer splice sites (Fig. 5). Thus, the amplified fragment, which was the same whether we used RNA from lytic or latent KOS infections, showed the joining of upstream and downstream sequences precisely at the predicted exon boundaries (Fig. 5A). This demonstrated that the outer splice sites are normally active in lytic and latent infection, which supports the interpretation of our mutational studies that our splice site mutations abolished LAT expression by disrupting normal splicing. Using other primer pairs, we have also amplified and sequenced additional splice junctions from latent infections, demonstrating the mixed pairing of outer and inner splice sites of opposite polarity (data not shown) and identifying a minor splice acceptor previously observed in transient transfection studies with a LAT minigene (37) (Fig. 5B). Since no corresponding intron (or exon) products are detected on Northern blots, the splicing events generating these junctions are rare or the excised introns and ligated exons are unstable.

FIG. 5.

Exonic product of splicing between the canonical splice sites bounding 2-kb LAT in lytic and latent infections detected by RT-PCR with a summary of splicing events in latent infections. (A) RT-PCR analysis of the exon junction resulting from splicing of the 2-kb LAT within spliced mLAT. RNAs were isolated from strain 17-infected Vero cells at 12 h p.i. and from latently infected trigeminal ganglia (TG). Aliquots were reverse transcribed from an mLAT-specific primer downstream of the 2-kb LAT region, and the products were amplified by PCR with mLAT-specific primers narrowly flanking the 2-kb LAT sequence, as diagrammed. Sequencing of the single RT-PCR product from each reaction demonstrated the joining in both situations of mLAT sequences at the canonical splicing signals bounding the major LATs. The autoradiographs show the sequences through the splice junction. (B) Summary of splicing events in latency. The 1.5-kb LAT sequence is diagrammed as two black boxes separated by an open box representing the internal intron, which together represent the 2-kb LAT sequence; flanking mLAT sequences are shown as dotted lines. Splice joints identified by RT-PCR are illustrated above and below the diagram as intersecting diagonal lines connecting the two sides of the joint. *, cryptic splice acceptor previously seen in minigene-transfected but not virus-infected cells.

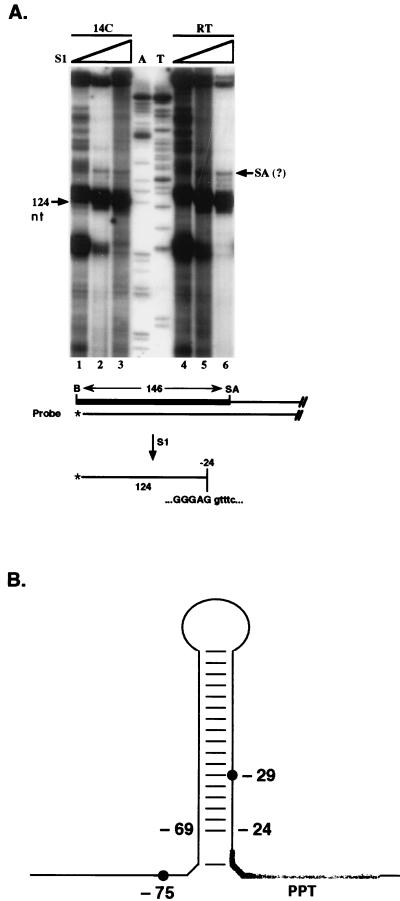

Consistent with a splicing mechanism generating the major LATs, the 5′ end of 2-kb LAT has been mapped to within a nucleotide from the exon/intron boundary in the outer splice donor sequence (61, 63). In contrast, varied evidence has been presented that the major LATs do not extend fully to the intron/exon boundary in the outer splice acceptor signal (46, 52, 68). Employing S1 nuclease protection experiments using a 3′ end-labeled probe centered over the outer splice acceptor signal (Fig. 6A), we mapped the 3′ end of the 2-kb LAT expressed in SK-N-SH cells infected with wt strain 17 to a position approximately 24 nt upstream of the splice acceptor site. Increasing amounts of S1 nuclease were used at two different temperatures (14°C and room temperature), and the center of the main protected band at the highest S1 concentration (300 U [lanes 3 and 6]) migrated at 124 nt, indicating the location of a 3′ end at position −24. Shorter autoradiographic exposures and an additional experiment using 1,050 U of enzyme showed prominent bands of 123 to 124 nt surrounded by several less intense bands, demonstrating that these were in fact completely digested products (data not shown). Thus, the major 3′ end of lytic 2-kb LAT is located near position −24 relative to the splice acceptor site (Fig. 6A, bottom). Interestingly, the faint band migrating 24 to 25 nt slower (lane 6) did not disappear when 1,050 U of S1 nuclease were used (data not shown), indicating that it might correspond to the very small fraction (7%) of lytic 2-kb LATs previously reported by Wu et al. to end at the splice acceptor (68).

FIG. 6.

S1 nuclease protection mapping of the 3′ ends of lytic 2-kb LAT and positions of the ends relative to previously proposed features. (A) S1 analysis of the 3′ ends of the 2-kb LAT. Increasing amounts of S1 enzyme (10 to 300 U) were used for digestions at 14°C (14C) and room temperature (RT). RNA was isolated from strain 17-infected SK-N-SH cells at 12 h p.i. The sketch of 3′-end-labeled probe below the autoradiograph indicates the position of the label (*) and the distance to the external splice acceptor site. The main protected bands on the autoradiograph at the highest enzyme concentrations (lanes 3 and 6) migrate at 123 to 124 nt, as determined by alignment with the A/T sequencing ladder. A product potentially extending to the splice acceptor (SA) is indicated. The main digestion products are sketched at the bottom, with the final protected nucleotides shown in capitals. (B) Proposed stem-loop structure in the 3′ region of LAT. All base pairs proposed by Krummenacher et al. (37) are represented, including a potentially unstable A:T pair at the base of the stem below two unpaired positions. The polypyrimidine tract (PPT) is shaded, and the alternately proposed branch points at −29 and −75 are marked by dots. The drawing illustrates that position −24, representing a major 3′ end of LAT, is located at the bottom of the stable portion of the hairpin and that the potential branch point at position −29 is inside the hairpin.

DISCUSSION

Much circumstantial evidence supports the proposal that the LATs are generated by conventional pre-mRNA splicing, but significant counterarguments have also been raised. Central aspects of the proposal have been tested, and the results argue in favor of a splicing mechanism. Spliced mLAT has been detected in infected CV-1 cells (70), and using mutations that would typically eliminate accurate pre-mRNA splicing, another study showed that the predicted splice sites are necessary for 2-kb LAT production during lytic infection (2). Our own results with independent splice site mutations showing complete elimination of lytic 2-kb LAT expression confirm this earlier study and discredit the possibility that the earlier mutations acted by affecting a process other than splicing, a possibility raised by the observation that the earlier splice donor mutant produced residual 2-kb LAT during lytic infection. Using rescued viruses, we have also shown that the loss of 2-kb LAT expression by our mutant viruses is not due to unanticipated mutations elsewhere in the viral genome since reversion of the splice site mutations restores wild-type levels of 2-kb LAT. Moreover, we have confirmed the previous identification in productively infected cells of a spliced, low-abundance LAT RNA whose splice junction shows that it is the exonic product of splicing between the external splice sites (70). In combination, this evidence clearly demonstrates that lytic 2-kb LAT is produced by pre-mRNA splicing.

Although some evidence exists that lytic and latent 2-kb LAT are the same molecule, the implication that the two are formed by the same mechanism must be viewed with caution given the enormous differences between lytic HSV-1 infection and latency. Aside from the nearly complete shutdown of HSV-1 gene expression during latency, as opposed to the ordered expression of most or all HSV-1 genes during lytic infection, expression of the LAT locus is controlled by different promoters in the two situations (10), and production of abundant 1.5-kb LAT is restricted to the latent state (13, 52, 62). It is noteworthy in this regard that the viral mutant dl556, which has an exact deletion of the internal intron sequences, expressed high levels of 1.5-kb LAT under lytic conditions (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 7), indicating that the absence of this LAT in lytic infections is not due to instability. Furthermore, failure to detect large quantities of this transcript in infected (Fig. 3A, lanes 1, 10, and 14) (6, 46) and transfected (25) neuronal cell lines, as well as latently infected primary neuronal cell cultures (49), suggests that a simple neuronal environment is not sufficient for its expression and that production of 1.5-kb LAT requires a latency-specific event, most likely latency-specific recognition and activation of the internal splice sites. In view of these differences between the lytic and latent states, we and others (2) have tested whether the outer splice sites required for LAT formation in latency are the same as those required in lytic infection.

Our results show that the production of the 2- and 1.5-kb LATs during latency depends on the preservation of the canonical splice site sequences bounding the 2-kb LAT. As in lytic infection (Fig. 3A), we found that mutation of either sequence alone (ΔSD2 or ΔSA2), or the two combined (ΔSD2 or ΔSA2), abolished LAT production (Fig. 4), and we identified a low-abundance exonic product formed by splicing between these sequences (Fig. 5). We also observed that mutation of the presumed splice sites for the internal intron eliminated 1.5-kb LAT production (Fig. 4) but left production of 2-kb LAT unchanged, indicating that the internal and external splice sites function independently. Although these results strongly argue that the LATs expressed in latently infected animals are formed by splicing, ideal evidence would include detection of increased amounts of unspliced precursor and/or aberrantly spliced pre-mRNA in splice site mutant-infected cells. However, these products were not seen on Northern blots, and the explanation that they are unstable remains to be confirmed. By qualitative RT-PCR, we have observed splicing between external and internal splice sites as well as other aberrant splicing patterns in latent infections with wt virus (Fig. 5B). Although we have no evidence that these aberrant patterns were enhanced by the splice site mutations we have tested or that new aberrant patterns were created, each mutation selectively eliminated the wt patterns in which the affected site was engaged (unpublished results). As seen previously (37), we identified an additional splice acceptor site for the external splice donor (* in Fig. 5B; splice a) whose sequence conforms to the usual splice acceptor consensus. The mixed pairings and typical sequences of these various sites suggest that all of them are processed by standard pre-mRNA splicing rather than by other RNA-processing machineries that operate in the cell, such as the partially dedicated machinery responsible for the removal of AT-AC introns (57) or excision machineries producing such functional RNAs as the intron-based snoRNAs (reviewed in reference 60).

Unexpectedly and in apparent conflict with our results, Arthur and coworkers reported that a different set of mutations in the canonical splice site signals flanking the 2-kb LAT sequence did not significantly affect 2-kb LAT formation during latency (2). Among the various explanations offered by these authors, our results favor the suggestion that their substitution mutations resulted in the activation of nearby cryptic splice sites, directing the formation of aberrant 2-kb LATs. The group observed that their donor mutant LAT RNA was greatly underrepresented and differed in electrophoretic mobility from the normal 2-kb LAT. They explained this underrepresentation with the suggestion that the donor mutant virus established latency with reduced efficiency, a suggestion based on the reduced expression of LAT in what appears to be a circular argument. They suggested from the abnormal gel migration of the donor mutant RNA that 2-kb LAT formation in latency may involve a pair of neuron-specific splice sites different from the canonical splice sites used in lytic infection but also offered the alternative possibility that their 2-kb LAT variant was generated from a cryptic 5′ splice site 4-nt downstream of the original donor site. Our results support the second interpretation since we did not see any latent RNA with our splice donor mutant which had the consensus GT dinucleotide of the putative cryptic site deleted precisely to prevent its activation. Furthermore, we note that the underrepresentation of the 2-kb LAT variant is readily explained by the use of a weak cryptic splice donor instead of the normal splice donor. In the same vein, we would suggest that the abundant RNA produced by the splice acceptor mutant of Arthur et al. was also an aberrant product. This RNA was not expressed by our splice acceptor mutant which lacked the consensus AG at the end of the presumed intron, whereas the substitution mutations of Arthur et al. created a new AG 2 nt downstream. Thus, we suggest that the 2-kb LATs described by these authors were not authentic LATs but unnatural variants created from cryptic splice sites activated in response to the splice site mutations that they tested. Within the context of this interpretation, the observations of Arthur et al. conform to the conclusion from our work that the predicted splice sites are critical for the generation of the normal LATs in latency.

Considerable evidence now exists that lytic 2-kb LAT is a lariat-shaped molecule, as expected for an excised intron (46, 68). However, most excised introns are rapidly degraded while the LATs are stable (37, 46). It has been shown by hybridization with short oligonucleotide probes that the 2-kb LAT does not extend fully to the external splice acceptor site (46, 52, 68), suggesting that this excised intron is targeted by a 3′-exonucleolytic activity like most excised introns, but that this activity encounters a barrier just inside the intron. This barrier could be the lariat branch itself, which would normally be removed by a cellular debranching activity (7), or a proposed hairpin structure between positions −21 and −72 relative to the splice acceptor with a 12-nt loop (Fig. 6B) (70). Since the position of the branched nucleotide is controversial, with one group suggesting position −75 (70) and another position −29 (67), we reasoned that precise mapping of the 3′ end of the 2-kb LAT could shed light on this issue.

Our S1 nuclease protection experiments demonstrate that lytic 2-kb LAT ends 24 to 25 nt upstream of the splice acceptor, which is precisely at the bottom of the stem portion of the proposed hairpin (Fig. 6B). This result is consistent with the hairpin protecting the excised intron from exonucleolytic degradation, which would suggest that the hairpin exists when the intron is released, presumably as a lariat. Unlike the alternate branch point at position −29, which would be inside the hairpin thereby possibly distorting its structure, the proposed branch point at position −75 would be located just upstream of the hairpin. The −75 branch point would be unusual in that it is a guanosine instead of the usual adenosine, is positioned more than the usual 18 to 40 nt upstream of the splice acceptor site (29), and is followed by a number of adenosines which would normally be favored as branch points (40). However, these features can be explained by the observation that the hairpin would span the distance between the −75 region and the polypyrimidine tract near the end of the intron (Fig. 6B), thereby allowing direct branch selection away from paired nucleotides in the hairpin, in favor of the upstream site. First, proximity between the branch point region and the polypyrimidine tract typically located near the 3′ end of introns is important for efficient branch formation, and there is precedent for hairpins coordinating the recognition of distant splice site elements (8, 22, 45). Second, experimental evidence has been presented that disruptive mutations in the LAT hairpin result in the utilization of alternative branch sites, supporting the suggestion that the hairpin plays an important role in branch site selection (37). In addition, since adenosine branches (position −29) are sensitive to HeLa cell debranching activity whereas guanosine branches (position −75) are not, branch formation at position −75 would offer an explanation for the reported resistance of 2-kb LAT to linearization by debranching extract (46, 68). Also, the −29 branch as a barrier to exonucleolytic degradation of the intron would not fully account for the observed protection down to position −24 and, unless the protective hairpin forms after branching, the region around position −29 would be unavailable for base pairing with the U2 small nuclear RNA, an interaction believed to be essential for branch formation (23, 43, 66, 72). Although these considerations may suggest that the unusual stability of the LATs is presently best explained by the hairpin/upstream-branch point model (Fig. 6B) (70), the strength of the experimental evidence for either branch point is debatable. The −75 site was mapped by a novel but largely untested procedure, and results from oligonucleotide-directed RNase H digestion studies that appear to argue against a major branch upstream of position −46 have been presented (67). Meanwhile, the primer extension experiment mapping the −29 branch point used a primer designed to anneal to the extreme 3′ end of the intron, apparently ignoring the previous evidence that this region is missing in the majority (>90%) of 2-kb LAT (68); it is therefore unclear whether this experiment detected a relevant precursor of 2-kb LAT or an aberrant end product of a minor processing pathway. In total, although our results appear to favor the hairpin model, firm conclusions will require further experimental efforts to resolve the present uncertainty regarding the branch position.

In conclusion, our results provide strong evidence that the lytic and latent LATs are formed by one and the same mechanism, which is conventional pre-mRNA splicing using the same canonical splice site signals. We suggest that our conclusions are in agreement with the results from a similar study by others (2) despite the appearance of disparate interpretations. Our study has provided additional information that defines the origin of the LATs in vivo and contributes to a better understanding of the unusual stability of the LATs. There remain, however, important questions regarding the function(s) of LAT. Is the stable LAT intron important for maintaining latency in humans despite its apparent lack of importance in rodents? Why is LAT internally spliced in vivo, and does the product have a unique functional role? Lastly, given evidence supporting an essential role of ICP0 in virus reactivation from latency (6, 30, 38, 71), does this role depend in part on functional activities encoded by the LAT locus? That is, interactions between the LATs and ICP0 could be key in the control of latency, a hypothesis that awaits further exploration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Saul Silverstein for providing the IE-0:lacZ transplacement vector. We thank M. Karina Soares for help with the figures and M. Karina Soares, Samuel French, James Cavalcoli, and Darren Wolfe for invaluable discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aebi M, Hornig H, Padgett R A, Reiser J, Weissmann C. Sequence requirements for splicing of higher eukaryotic nuclear pre-mRNA. Cell. 1986;47:555–565. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur J L, Everett R, Brierley I, Efstathiou S. Disruption of the 5′ and 3′ splice sites flanking the major latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1: evidence for alternate splicing in lytic and latent infections. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:107–116. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berk A J. Characterization of RNA molecules by S1 nuclease analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:335–347. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Block T M, Hill J M. The latency associated transcripts (LAT) of herpes simplex virus: still no end in sight. J Neurovirol. 1997;3:313–321. doi: 10.3109/13550289709030745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S M, Ritchie D A, Subak-Sharpe J H. Genetic studies with herpes simplex virus type 1. The isolation of temperature-sensitive mutants, their arrangement into complementation groups and recombination analysis leading to a linkage map. J Gen Virol. 1973;18:329–346. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-18-3-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai W, Astor T L, Liptak L M, Cho C, Coen D M, Schaffer P A. The herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein ICP0 enhances virus replication during acute infection and reactivation from latency. J Virol. 1993;67:7501–7512. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7501-7512.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman K B, Boeke J D. Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding yeast debranching enzyme. Cell. 1991;65:483–492. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90466-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chebli K, Gattoni R, Schmitt P, Hildwein G, Stevenin J. The 216-nucleotide intron of the E1A pre-mRNA contains a hairpin structure that permits utilization of unusually distant branch acceptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4852–4861. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Silverstein S. Herpes simplex viruses with mutations in the gene encoding ICP0 are defective in gene expression. J Virol. 1992;66:2916–2927. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2916-2927.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Schmidt M C, Goins W F, Glorioso J C. Two herpes simplex virus type 1 latency active promoters differ in their contribution to latency-associated transcript expression during lytic and latent infection. J Virol. 1995;69:7899–7908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7899-7908.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chomczynski P. One-hour downward alkaline capillary transfer for blotting of DNA and RNA. Anal Biochem. 1992;201:134–139. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90185-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLuca N A, Courtney M A, Schaffer P A. Temperature-sensitive mutants in herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 permissive for early gene expression. J Virol. 1984;52:767–776. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.3.767-776.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devi-Rao G B, Goddart S A, Hecht L M, Rochford R, Rice M K, Wagner E K. Relationship between polyadenylated and nonpolyadenylated HSV type 1 latency-associated transcripts. J Gen Virol. 1991;65:2179–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2179-2190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson A T, Sederati F, Devi-Rao G, Flanagan W M, Farrell M J, Stevens J G, Wagner E K, Feldman L T. Identification of the latency-associated transcript promoter by expression of rabbit β-globin mRNA in mouse sensory nerve ganglia latently infected with a recombinant herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 1989;63:3844–3851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3844-3851.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doerig C, Pizer L I, Wilcox C L. An antigen encoded by the latency-associated transcripts in neuronal cell cultures latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1991;65:2724–2727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2724-2727.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escurat M, Djabali K, Gumpel M, Gros F, Portier M-M. Differential expression of two neuronal intermediate-filament proteins, peripherin and the low-molecular-mass neurofilament protein (NF-L), during the development of the rat. J Neurosci. 1990;10:764–784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-03-00764.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fareed M, Spivack J. Two open reading frames (ORF1 and ORF2) within the 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript of herpes simplex virus type 1 are not essential for reactivation from latency. J Virol. 1994;68:8071–8081. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8071-8081.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell M J, Dobson A T, Feldman L T. Herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is a stable intron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:790–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser N W, Block T M, Spivack J G. The latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus: RNA in search of a function. Virology. 1992;191:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90160-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frink R J, Eisenberg R, Cohen G, Wagner E K. Herpes simplex virus type 1 HindIII fragment L encodes spliced and complementary mRNA species. J Virol. 1983;39:559–572. doi: 10.1128/jvi.39.2.559-572.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godowski P J, Knipe D M. Transcriptional control of herpesvirus gene expression: gene functions required for positive and negative regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;83:256–260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goguel V, Rosbash M. Splice site choice and splicing efficiency are positively influenced by pre-mRNA intramolecular base pairing in yeast. Cell. 1993;26:893–901. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90578-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goguel V, Wang Y, Rosbash M. Short artificial hairpins sequester splicing signals and inhibit yeast pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6841–6848. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goins W F, Sternberg L R, Croen K D, Krause P R, Hendricks R L, Fink D J, Straus S E, Levine M, Glorioso J C. A novel latency-active promoter is contained within the herpes simplex virus type 1 UL flanking repeats. J Virol. 1994;68:2239–2252. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2239-2252.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldenberg D, Mador N, Ball M J, Panet A, Steiner I. The abundant latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1 are bound to polyribosomes in cultured neuronal cells and during latent infection in mouse trigeminal ganglia. J Virol. 1997;71:2897–2904. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2897-2904.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldenberg D, Mador N, Panet A, Steiner I. Tissue specific distribution of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts on polyribosomes during latent infection. J Neurovirol. 1998;4:426–432. doi: 10.3109/13550289809114541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldin A L, Sandri-Goldin R M, Levine M, Glorioso J C. Cloning of herpes simplex virus type 1 sequences representing the whole genome. J Virol. 1981;38:50–58. doi: 10.1128/jvi.38.1.50-58.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham F L, van der Eb A J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green M R. Pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:671–708. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.003323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris R A, Everett R D, Zhu X X, Silverstein S, Preston C M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein Vmw 110 reactivates latent herpes simplex virus type 2 in an in vitro latency system. J Virol. 1989;63:3513–3515. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.8.3513-3515.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Homa T C, Otal T M, Glorioso J C, Levine M. Transcriptional control signals of a herpes simplex virus type 1 late (γ2) gene lie within bases −34 to +124 relative to the 5′ terminus of the mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3652–3666. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horton R M, Ho S N, Pullen J K, Hunt H D, Cai Z, Pease L R. Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol. 1993;217:270–279. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)17067-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kosz-Vnenchak M. Evidence for a novel regulatory pathway for herpes simplex virus gene expression in trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Virol. 1993;67:5383–5393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5383-5393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer M F, Coen D M. Quantification of transcripts from the ICP4 and thymidine kinase genes in mouse ganglia latently infected with herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 1995;69:1389–1399. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1389-1399.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krawczak M, Reiss J, Coopera D N. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum Genet. 1992;90:41–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00210743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krisky D, Marconi P, Goins W F, Glorioso J C. Development of replication-defective herpes simplex virus vectors. In: Robbins P, editor. Methods in molecular medicine, gene therapy protocols. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press Inc.; 1996. pp. 79–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krummenacher C, Zabolotny J, Fraser N. Selection of a nonconsensus branch point is influenced by an RNA stem-loop structure and is important to confer stability to the herpes simplex virus 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript. J Virol. 1997;71:5849–5860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5849-5860.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leib D, Coen D, Bogard C, Hicks K, Yager D, Knipe D, Tyler K, Schaffer P. Immediate-early regulatory gene mutants define different stages in the establishment and reactivation of herpes simplex virus latency. J Virol. 1989;63:759–768. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.759-768.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell W J, Lirette R P, Fraser N W. Mapping of low abundance latency-associated RNA in the trigeminal ganglia of mice latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:125–132. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore M J, Query C C, Sharp P A. Splicing of precursors to messenger RNAs by the spliceosome. In: Gesteland R F, Atkins J F, editors. The RNA world: the nature of modern RNA suggests a prebiotic RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicosia M, Deshmane S L, Zabolotny J M, Valyi-Nagy T, Fraser N W. Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) promoter deletion mutants can express a 2-kilobase transcript mapping to the LAT region. J Virol. 1993;67:7276–7283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7276-7283.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicosia M, Zabolotny J M, Lirette R P, Fraser N W. The HSV-1 2-kb latency-associated transcript is found in the cytoplasm comigrating with ribosomal subunits during productive infection. Virology. 1994;204:717–728. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker R, Siliciano P G, Guthrie C. Recognition of the TACT AAC box during mRNA splicing in yeast involves base pairing to the U2-like snRNA. Cell. 1987;49:229–239. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90564-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perry L J, McGeoch D J. The DNA sequences of the long repeat region and adjoining parts of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2831–2846. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-11-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reed R. The organization of 3′ splice-site sequences in mammalian introns. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2113–2123. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodahl E, Haarr L. Analysis of the 2-kilobase latency-associated transcript expressed in PC12 cells productively infected with herpes simplex virus type 1: evidence for a stable, nonlinear structure. J Virol. 1997;71:1703–1707. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1703-1707.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodahl E, Stevens J. Differential accumulation of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts in sensory and autonomic ganglia. Virology. 1992;189:385–388. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90721-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roizman B, Sears A. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Hirsch M S, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2231–2295. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith R, Escudero J, Wilcox C. Regulation of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcripts during the establishment of latency in sensory neurons in vitro. Virology. 1994;202:49–60. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spivack J, Fraser N. Expression of herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts in trigeminal ganglia of mice during acture infection and reactivation of latent infection. J Virol. 1988;62:1479–1485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1479-1485.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spivack J G, Fraser N W. Detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 transcripts during latent infection in mice. J Virol. 1987;61:3841–3847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3841-3847.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spivack J G, Woods G M, Fraser N W. Identification of a novel latency-specific splice donor signal within herpes simplex virus type 1 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript (LAT): translation inhibition of LAT open reading frames by the intron within the 2.0-kilobase LAT. J Virol. 1991;65:6800–6810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6800-6810.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevens J G. Human herpesviruses: a consideration of the latent state. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:318–332. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.3.318-332.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strelow L I, Laycock K A, Jun P Y, Rader A, Brady R H, Miller J K, Pepose J S, Leib D A. A structural and functional comparison of the latency-associated transcript promoters of herpes simplex virus type 1 strains KOS and McKrae. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2475–2480. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stroop W G, Rock D L, Fraser N W. Localization of herpes simplex virus in the trigeminal and olfactory systems of the mouse central nervous system during acute and latent infections by in situ hybridization. Lab Investig. 1984;51:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanaka S, Minagawa H, Toh Y, Liu Y, Mori R. Analysis by RNA-PCR of latency and reactivation of herpes simplex virus in multiple neuronal tissues. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2691–2698. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarn W-Y, Steitz J A. Highly diverged U4 and U6 small nuclear RNAs required for splicing rare AT-AC introns. Science. 1996;273:1824–1832. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tenser R B, Dunstan M E. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase expression in infection of the trigeminal ganglion. Virology. 1979;99:417–422. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson R L, Sawtell N M. The herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene regulates the establishment of latency. J Virol. 1997;71:5432–5440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5432-5440.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tollervey D, Kiss T. Function and synthesis of small nucleolar RNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:337–342. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wagner E K, Devi-Rao G, Feldman L T, Dobson A T, Zhang Y, Elanagan W F, Stevens T. Physical characterization of the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript in neurons. J Virol. 1988;62:1194–1202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1194-1202.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner E K, Flanagan W M, Devi-Rao G B, Zhang Y F, Hill J M, Anderson K P, Stevens J G. The herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript is spliced during the latent phase of infection. J Virol. 1988;62:4577–4585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4577-4585.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wechsler S L, Nesburn A B, Watson R, Slanina S M, Ghiasi H. Fine mapping of the latency-related gene of herpes simplex virus type 1: alternative splicing produces distinct latency-related RNAs containing open reading frames. J Virol. 1988;62:4051–4058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.4051-4058.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wechsler S L, Nesburn J, Zwaagstra N, Ghiasi H. Sequence of the latency related gene of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology. 1989;168:168–172. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitley P J. Herpes simplex virus. In: Fields B N, editor. Virology. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 1843–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu J, Manley J L. Mammalian pre-mRNA branch site selection by U2 snRNP involves base pairing. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.10.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu T-T, Su Y-H, Block T M, Taylor J M. Atypical splicing of the latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex type 1. Virology. 1998;243:140–149. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu T-T, Su Y-H, Block T M, Taylor J M. Evidence that two latency-associated transcripts of herpes simplex virus type 1 are nonlinear. J Virol. 1996;70:5962–5967. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5962-5967.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yao F, Schaffer P A. An activity specified by the osteosarcoma line U2OS can substitute functionally for ICP0, a major regulatory protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:6249–6258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6249-6258.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zabolotny J, Krummenacher C, Fraser N W. The herpes simplex virus type 1 2.0-kilobase latency-associated transcript is a stable intron which branches at a guanosine. J Virol. 1997;71:4199–4208. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4199-4208.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu X X, Chen J X, Young C S, Silverstein S. Reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus by adenovirus recombinants encoding mutant IE-0 gene products. J Virol. 1990;64:4489–4498. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4489-4498.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]