Abstract

Background

Malaria caused by Plasmodium species is a prominent public health concern worldwide, and the infection of a malarial parasite is transmitted to humans through the saliva of female Anopheles mosquitoes. Plasmodium invasion is a rapid and complex process. A critical step in the blood-stage infection of malarial parasites is the adhesion of merozoites to red blood cells (RBCs), which involves interactions between parasite ligands and receptors. The present study aimed to investigate a previously uncharacterized protein, PbMAP1 (encoded by PBANKA_1425900), which facilitates Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbANKA) merozoite attachment and invasion via the heparan sulfate receptor.

Methods

PbMAP1 protein expression was investigated at the asexual blood stage, and its specific binding activity to both heparan sulfate and RBCs was analyzed using western blotting, immunofluorescence, and flow cytometry. Furthermore, a PbMAP1-knockout parasitic strain was established using the double-crossover method to investigate its pathogenicity in mice.

Results

The PbMAP1 protein, primarily localized to the P. berghei membrane at the merozoite stage, is involved in binding to heparan sulfate-like receptor on RBC surface of during merozoite invasion. Furthermore, mice immunized with the PbMAP1 protein or passively immunized with sera from PbMAP1-immunized mice exhibited increased immunity against lethal challenge. The PbMAP1-knockout parasite exhibited reduced pathogenicity.

Conclusions

PbMAP1 is involved in the binding of P. berghei to heparan sulfate-like receptors on RBC surface during merozoite invasion.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13071-023-05896-w.

Keywords: Plasmodium, Heparin-binding protein, Invasion, Pathogenicity

Background

Malaria remains one of the world’s most important fatal diseases, with at least 241 million malaria cases and 627,000 malaria deaths recorded worldwide each year [1]. The growth and replication of Plasmodium parasites in red blood cells (RBCs) and the rupture of infected RBCs (iRBCs) are responsible for most symptoms of malaria [2]. Therefore, the blood stage of the parasites is the primary target for intervention. The process of erythrocyte invasion by the merozoites involves four continuous steps: attachment of a merozoite to the erythrocyte surface, followed by apical reorientation, tight junction formation, and final invasion [3]. As the adhesion of a merozoite to the RBC surface is essential to complete invasion, it is logical to believe that molecules presented on the merozoite surface play a critical role in this process. To date, several merozoite surface proteins as well as rhoptry- and microneme-derived proteins have been shown to play roles in the invasion process [4]. However, many proteins are associated with erythrocyte invasion, the functions of which remain to be explored further.

Heparan sulfate (HS), a non-branched polysaccharide of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which are widely distributed on the surface of vertebrate cells, is utilized by Apicomplexan parasites to invade host cells [5–11]. The adhesion of Toxoplasma gondii surface antigens and secreted proteins to host cells via heparin/HS has been reported. Specifically, T. gondii invasion-related proteins, such as surface protein 1 (SAG1), rhoptry protein 2 (ROP2), ROP4, and dense granule antigen 2 (GRA2), bind heparin [12]. HS is an essential receptor for Plasmodium falciparum that recognizes erythrocytes prior to invasion. HS also functions as a receptor for P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), a parasite virulent factor associated with rosette formation that can adhere to normal erythrocytes [13, 14]. In addition, P. falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 (PfMSP-1), reticulocyte-binding homolog (PfRH5), and erythrocyte-binding protein (PfEBA-140) have been reported to bind to HS on the surface of RBCs and are disrupted by heparin [11, 15, 16]. Additionally, HS inhibits the invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium berghei [17]. However, many proteins expressed on the P. berghei merozoite surface that interact with HS remain poorly characterized.

In the present study, we identified a novel protein (PbMAP1) on the surface of P. berghei that binds heparin and HS. The specificity of PbMAP1 binding to HS on the surface of RBCs was characterized. PbMAP1-specific antibodies inhibited parasite invasion. Parasites with gene deletion exhibited reduced pathogenicity in mice. Our findings suggest that PbMAP1 plays a critical role in merozoite invasion of erythrocytes.

Methods

Animals

Female BALB/c mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were purchased from Liaoning Changsheng Biological Technology Company (Benxi, China) and maintained in an animal laboratory using a standard protocol. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines of the Shenyang Agricultural University, China (ethical approval no. SYXK < Liao > 2021-0010).

Parasite proliferation

Parasites were revitalized from frozen infected RBC stocks and maintained by infecting BALB/c mice through intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 1 × 106 parasitised erythrocytes per mouse, as previously described [18]. Peripheral blood parasitemia was assessed using Giemsa-stained thin blood smears.

Bioinformatic analysis and gene identification

To identify genes encoding potential merozoite surface proteins, we searched the PlasmoDB malaria database for proteins expressed in merozoites with a putative signal peptide or an external or at least one transmembrane domain [19]. We identified PBANKA_1425900, which encodes a putative protein of 154 kDa, named PbMAP1. PbMAP1 (PBANKA_1425900) and orthologous sequences in Plasmodium yoelii (PY17X_1428000), P. chabaudi (PCHAS_1427700), P. vinckei (PVSEL_1402900), P. falciparum (PF3D7_0811600), P. ovale (PocGH01_14036000), P. malariae (PMALA_030180), P. gaboni (PGSY75_0811600), and P. reichenowi (PRCDC_0810900) were obtained by searching within the PlasmoDB database. Sequence similarities were determined using DNAMAN 6 (Lynnon Corp., USA).

Generation of recombinant PbMAP1 protein

The gene encoding PbMAP1 was cloned using RT-PCR with total RNA isolated from P. berghei-infected erythrocytes. The amplified product was cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 expression vector. The GST-tagged recombinant protein was expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells, and the soluble protein was purified using Glutathione Sepharose (GE Healthcare) via affinity purification.

Heparin-binding and competition assays

Purified GST-PbMAP1 and GST proteins (5 nmol) were mixed with 40 μl heparin-Sepharose beads and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were washed seven times with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min at 4 °C. The pellets were boiled in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer to analyze the heparin-binding activity by western blotting. Sepharose was used as the control.

To analyze the specific affinity between the protein and heparin, 5 nmol GST-PbMAP1 was incubated with 50 μl heparin or chondroitin sulfate A (CSA, Sigma Aldrich, USA) at various concentrations (10, 1, 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001 mg ml-1) for 30 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, 40 μl heparin-Sepharose beads were gradually added to the mixture and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. Finally, the heparin-Sepharose beads were washed seven times with PBS and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min at 4 °C. The effect of competition was analyzed using western blotting. Heparin-binding and competition assays were conducted as previously described [20].

Binding of recombinant PbMAP1 to RBCs

Affinity-purified GST-PbMAP1 and the GST control protein were respectively incubated with mouse RBCs (7 μl packed volume) in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37 ℃ (final volume 1 ml) [21]. The RBC pellet was washed seven times in 1 ml PBS, and proteins bound to the RBCs were analyzed with western blotting using GST mAb (1:3000; TransGen).

To further confirm the binding of PbMAP1 to mouse RBC, freshly collected RBCs in PBS were washed, resuspended in RPMI (20% hematocrit), and fixed on glass slides with methanol (20–30 s) as a thin smear. The fixed RBCs were washed in PBS, blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at 37 °C, washed again (5 times, 10 min each), and incubated with 5 nmol GST-PbMAP1 or 5 nmol GST in 3% BSA for 2 h at 37 °C. Slide samples were washed five times with PBS, incubated with goat anti-GST antibody (1:3000; TransGen), washed five times, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:500; Sigma). High-resolution images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems). The mean fluorescence intensity of the RBCs was determined using the FACSAria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Generation of PbMAP1-specific antibodies

A peptide (CLYKSFKFVPPKKKLTDYFEEMFSDHKVEYDSLENVSKQL) from the PbMAP1 protein was synthesized by Sangon Biotech. Rats and mice were immunized to obtain polyclonal antibodies. For the first immunization, 50 μg peptide per mouse emulsified with complete Freund’s adjuvant was subcutaneously injected, followed by three immunizations with 50 μg peptide per mouse emulsified with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant at 2-week inter-injection intervals. The mice in the control group were injected with Freund’s adjuvant. Antibody titers were evaluated using ELISA. Briefly, to coat microplates with recombinant PbMAP1, 50 μl of the prepared working PbMAP1 protein solution was added to each well of a 96-well ELISA plate (0.5 μg PbMAP1/well). The plate was incubated overnight at 4 ℃. Subsequently, the unbound coating PbMAP1 solution was discarded, and the wells were washed three times with 200 μl PBST. The remaining protein-binding sites in the coated wells were blocked by adding 50 μl of 3% BSA per well of the microtiter plate and incubated for 1 h at 37 ℃. Next, after washing three times, the plate was incubated with 50 μl diluted serum samples (1:500, 1:1000, 1:2000, 1:4000, 1:8000, 1:16,000, and 1:32,000) at 37 ℃ for 1 h for binding reaction, followed by 50 μl HRP anti-mouse IgG antibodies in the dark at 37 ℃ for 1 h. The unbound HRP anti-mouse IgG antibodies were washed five times with 200 μl PBST. For substrate reaction, 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added to each well and incubated in the dark at 37 ℃ for 15 min for blue color development. At the next stage, 50 μl of 2M H2SO4 was added to each well to quench the reaction. Absorbance was read with a microtiter plate reader at 450 nm immediately after the addition of 2M H2SO4. The antibodies for the samples were determined using the following formula: titer = (optical density [OD] values of sample—OD values of blank control)/(OD values of negative control—OD values of blank control).

Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to localize the expression of PbMAP1

Infected red blood cell smears were fixed in methanol at room temperature for 10 min. The cells were marked with a hydrophobic PAP pen and washed five times with PBS. The cells were blocked with 3% BSA. Primary anti-PbMAP1 antibodies (1:50) were diluted in 3% BSA and added to the slides. The cells were incubated overnight at 4°C and subsequently washed five times with PBS. Next, secondary anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 antibodies (1:500) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to the slides. The cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C and then washed five times with PBS. The cells were mounted with ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica).

Passive immunization assays with PbMAP1-immune sera

In passive immunization assays, each mouse was intravenously (IV) injected with 500 μl sera from peptide-immunized mice 24 h earlier. After 24 h of challenging with 1 × 106 iRBCs, each mouse was IV injected with 500 μl sera from peptide-immunized mice again. Parasitemia was measured and counted as described above.

Construction of plasmids for PbMAP1 gene editing

We used the double-crossover method to generate a PbMAP1-knockout strain, as previously described [22]. The plasmid was constructed using pl0001 (MR4; ATCC, USA). PbMAP1 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) were PCR-amplified as the left or right homologous arms and inserted respectively upstream and downstream of the DHFR gene. The 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR were subcloned in the pl0001 plasmid using restriction enzyme sites (Apa I/BspD I or BamH I/Not I).

To re-introduce the PbMAP1 gene into the knockout strain (ΔPbMAP1), the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid pYCm (a gift from Prof. Jing Yuan, Xiamen University) was used, and a parasitic strain with a reconstructed PbMAP1 gene was generated in ΔPbMAP1 strain. Oligonucleotides for guide RNA (sgRNA) were designed using the Eukaryotic Pathogen CRISPR guide RNA/DNA Design Tool (http://grna.ctegd.uga.edu/) and ligated into the pYCm. Mutagenesis was performed using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB, E0552). Specifically, the 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR (400 to 700 bp) of the target genes were amplified as left or right homologous arms using specific primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) and inserted into the restriction sites in pYCm.

Transfection of PbANKA parasites

Plasmodium berghei was transfected as previously described [22]. Two BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with erythrocytes from P. berghei-infected mice (1-4 droplets of 5%–15% parasitemia). Once parasitemia ranged between 1% and 3%, the parasites were collected and cultured in vitro to mature schizonts in RPMI 1640 containing 20% FBS. A total of 5 μg linear plasmid (digested with Kpn I and Sac II) was mixed with 1 × 107 schizonts purified with 60% Nycodenz (AXIS-SHIELD). The mixture was transferred to an electroporation cuvette and pulsed at 800 V and 25 μF capacitance using Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad). To the transfected parasites, 100 μl of complete culture medium was added immediately, and the suspension was IV injected into another BALB/c mouse. The mice were administered drinking water containing pyrimethamine (70 μg ml-1) 1 day after infection with transfected parasites (with knockout plasmids). Pyrimethamine was administered for 4–9 days up to the collection of infected blood. In addition, a single dose of 0.1 ml WR99210 (16 mg kg-1 body weight in mice weighing 20 g) was administered 3 days after infection with transfected parasites (with complemented plasmid). Genomic DNA was extracted from parasites for PCR analysis. Parasite clones with the correct modifications were obtained using the limiting dilution method. Positive clones were tested using PCR, western blotting and IFA. The primers used for genotyping are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Confirmation of PbMAP1 expression in gene-edited parasites with southern blotting

Southern blotting of PbMAP1 and ΔPbMAP1 parasites was performed using the DIG High Prime DNA Labelling and Detection Starter Kit (Roche) according to the product manual. Briefly, genomic DNA was digested by Hind III for 1 h at 37 °C and separated on a 0.8% agarose gel for southern blotting onto a Hybond N+ nylon transfer membrane (Millipore). The target gDNA bands were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe complementary to PbMAP1 and detected using an anti-digoxigenin AP-conjugated antibody. The primers used for probe amplification are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Infectivity tests of mice with wild-type P. berghei and gene-edited strains

For comparison the infectivity of wild-type P. berghei and gene-edited strains, 90 female BALB/c mice were randomly divided into nine groups of 10 mice each and were intraperitoneally administered with specific doses (1 × 103, 1 × 104, or 1 × 106) of P. berghei wild-type (WT), ΔPbMAP1 (knockout strain), or ReΔPbMAP1 (the gene re-complement strain) strains. Parasitemia was assessed daily by counting cells in Giemsa-stained smears from a droplet of tail blood. Animals were monitored daily for survival.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

The parasites were harvested from the blood of BALB/c mice infected with WT or ΔPbMAP1 strains. Total RNA was extracted [23] from the parasite pellets using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), dissolved in RNase-free pure water, and quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000/2000c). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from random primer mixes using PrimeScript RT Enzyme Mix I (Takara), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers (Additional file 1: Table S1) were designed to detect the mRNA transcription of certain genes after PbMAP1 knockout. The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The housekeeping gene actin (PBANKA_1459300) was used to normalize the transcriptional level of each gene.

Serum cytokine analyses

Levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, MCP-1, CCL4, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12p70 in mouse sera were determined using the Cytometric Bead Array Mouse Inflammation kit (BD Biosciences). Samples were assayed according to the standard protocol (BD Biosciences) and examined using the FACSAria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) driven by the FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

Results

The sequence of PbMAP1 is conserved across Plasmodium species

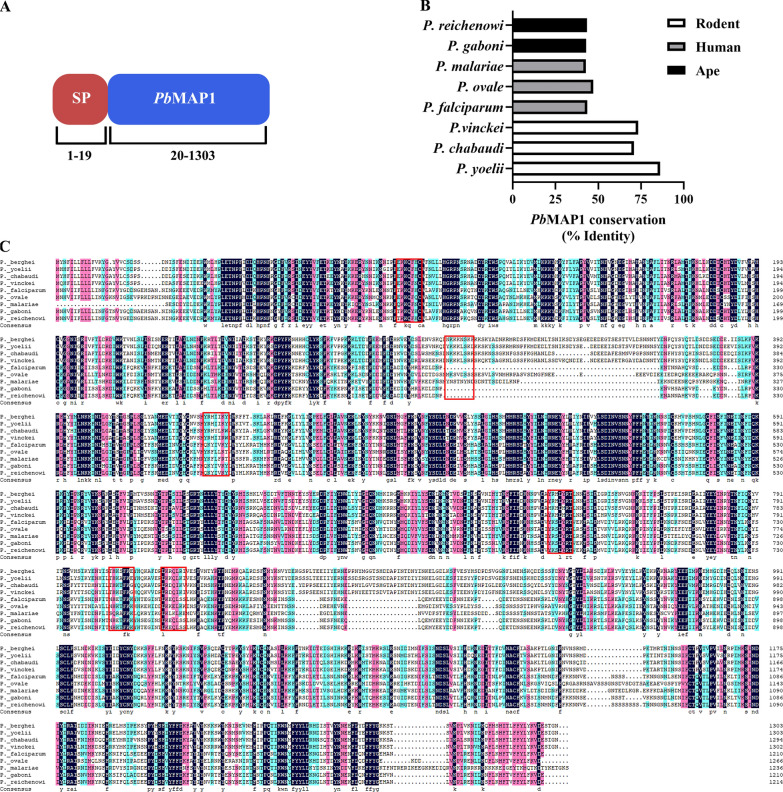

The gene coding for PbMAP1 is located on chromosome 14 and encodes a protein of 1303 amino acids, which is predicted to contain a signal peptide at the N-terminus (Fig. 1A). The amino acid sequence of PbMAP1 is relatively conserved across Plasmodium species, with > 70% identity among P. yoelii, P. chabaudi, and P. vinckei orthologs, > 40% identity across species infecting humans (including the zoonotic P. knowlesi), and > 43% identity with species infecting apes (Fig. 1B, 1C).

Fig. 1.

Sequence analysis of PbMAP1. A PbMAP1 is 1303-amino acid long and predicted to contain a signal peptide. B Identity in amino acid sequence between PbMAP1 and orthologous sequences from other Plasmodium species. C Alignment of amino acid sequence of PbMAP1 with orthologs of Plasmodium species (sequence identities are listed in the Methods section). The putative heparin binding motifs in the sequences are highlighted in the red box

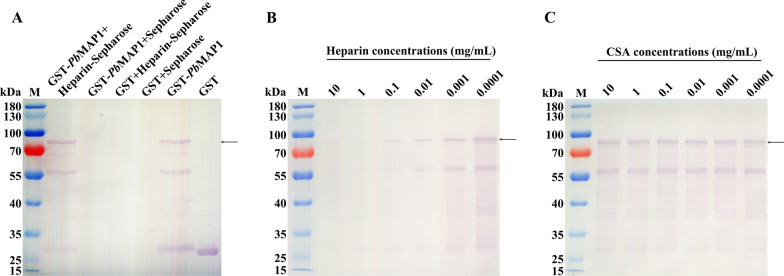

PbMAP1 specifically binds heparin

To demonstrate the properties of PbMAP1 binding to heparin, the recombinant protein GST-PbMAP1 was purified. GST-PbMAP1 could bind to heparin-Sepharose but not to Sepharose, whereas GST could not bind to heparin (Fig. 2A). The competitive inhibition assay revealed that with an increase in heparin concentration, the binding amount of GST-PbMAP1 to heparin decreased gradually (Fig. 2B); however, no significant change in the binding of GST-PbMAP1 to heparin was noted with increase in CSA concentration (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

GST-PbMAP1 specifically bound to heparin. A Heparin-binding activity was detected using western blotting with anti-GST antibody. GST-PbMAP1 could bind heparin-Sepharose but not Sepharose. GST could not bind heparin-Sepharose. B Competitive inhibition was detected using western blotting with an anti-GST antibody. As the heparin concentration increased, GST-PbMAP1 binding with heparin-Sepharose gradually decreased. C As the CSA concentration increased, no significant changes in GST-PbMAP1 binding with heparin-Sepharose were noted

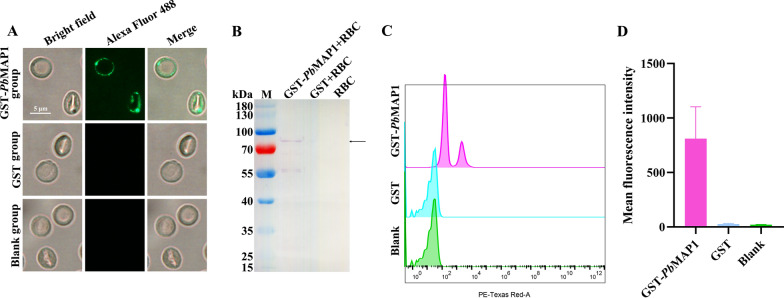

Recombinant PbMAP1 could specifically bind to mouse RBCs

GST-PbMAP1 and GST were incubated with RBCs and analyzed using IFA, western blotting, and flow cytometry. IFA showed that the RBCs incubated with GST-PbMAP1 exhibited specific green fluorescence on the surface, whereas the RBCs incubated with GST alone showed no fluorescence (Fig. 3A). Western blotting showed that specific target bands were detected for RBCs incubated with GST-PbMAP1, while no bands were detected for RBCs incubated with GST alone (Fig. 3B). The binding of GST-PbMAP1 to RBCs was analyzed using flow cytometry, and the results confirmed that PbMAP1 could bind to RBCs (Fig. 3C). Therefore, PbMAP1 could bind to the surface of RBCs.

Fig. 3.

GST-PbMAP1 binds to mouse RBCs. A Indirect immunofluorescence assay using an anti-GST antibody as the primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) as the secondary antibody shows the binding of GST-PbMAP1 to RBCs. GST was used as the control. Scale bar, 5 μm. B Western blotting using an anti-GST antibody shows the binding of GST-PbMAP1 to RBCs. C Cell flow cytometry analysis of erythrocyte binding by the GST-PbMAP1 with GST as a control. A clear shift is observed with GST-PbMAP1-bound erythrocytes. D The fluorescence intensity of erythrocytes bound with GST- PbMAP1 compared to that with GST and blank controls

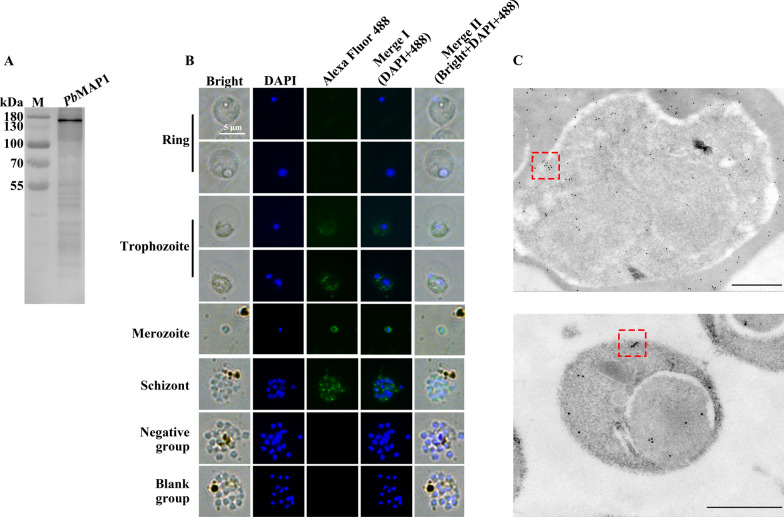

PbMAP1 localization on merozoites

To investigate the localization of PbMAP1 in merozoites, western blotting, IFA, and immunoelectron microscopy were performed using PbMAP1-specific antibodies. Western blotting confirmed PbMAP1 expression in merozoites. Next, we analyzed the expression and localization of PbMAP1 using IFA. Fluorescence was observed on the surface on free merozoites and that in the schizonts. Immunoelectron microscopy further verified that PbMAP1 was mainly located on the plasma membrane (Fig. 4A–C).

Fig. 4.

PbMAP1 is expressed in merozoites. A Western blotting of native PbMAP1 expressed in Plasmodium berghei merozoite detected using PbMAP1-specific antibodies. B Indirect immunofluorescence of PbMAP1. Free merozoites and parasite at ring-, trophozoite-, and schizont stages were fixed, and PbMAP1 expression was detected with anti-PbMAP1 IgG (green). Parasite nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). C Immune electron microscopy images of PbMAP1. The gold particles were localized to the merozoite membrane. Scale bar, 500 nm

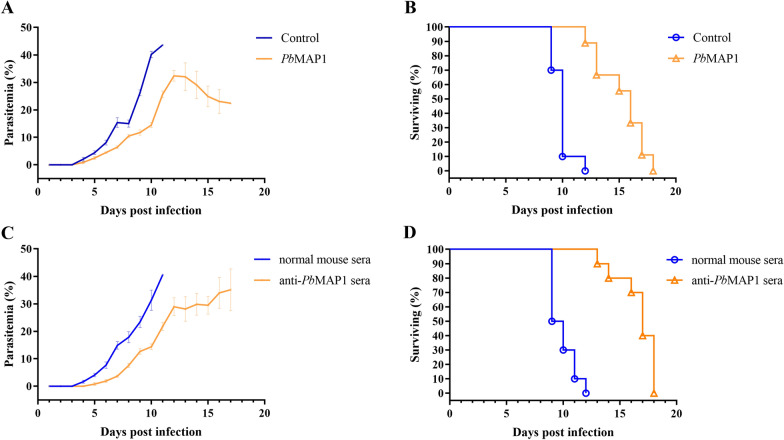

Immunization with PbMAP1-specific peptides protects against infection

In this assay, we aimed to determine whether PbMAP1-specific antibodies protected the host from parasitic infections in vivo. BALB/c mice (N = 10 per group) were immunized four times with specific peptides. The mice with high antibody titers were injected with 1 × 106 iRBCs, and their survival time and parasitemia were measured. The mice immunized with specific peptides showed significantly longer survival (Fig. 5A, B). Furthermore, hyperimmune serum was collected and intravenously injected into BALB/c mice, followed by the injection of 1 × 106 iRBCs. The survival of the mice injected with anti-PbMAP1 serum was significantly longer than that of the control mice. Therefore, PbMAP1 antibodies could inhibit the invasion of parasites and produce immune-protective effects (Fig. 5C, D).

Fig. 5.

PbMAP1-specific antibodies generated protective immunity against Plasmodium berghei ANKA. A, B BALB/c mice without any immunization (control) exhibited 1.70-fold higher parasitemia than PbMAP1 peptide-immunized mice on day 11 post-infection; the error bars indicate SD. Mice immunized with PbMAP1 peptides survived 6 days longer than control mice. C, D Mice injected with serum from a normal infected mouse exhibited 1.86-fold higher parasitemia than those injected with anti-PbMAP1 sera on day 11 post-infection. Compared with the normal mouse serum group, the anti-PbMAP1 serum group survived for 6 days longer; the error bars indicate SD

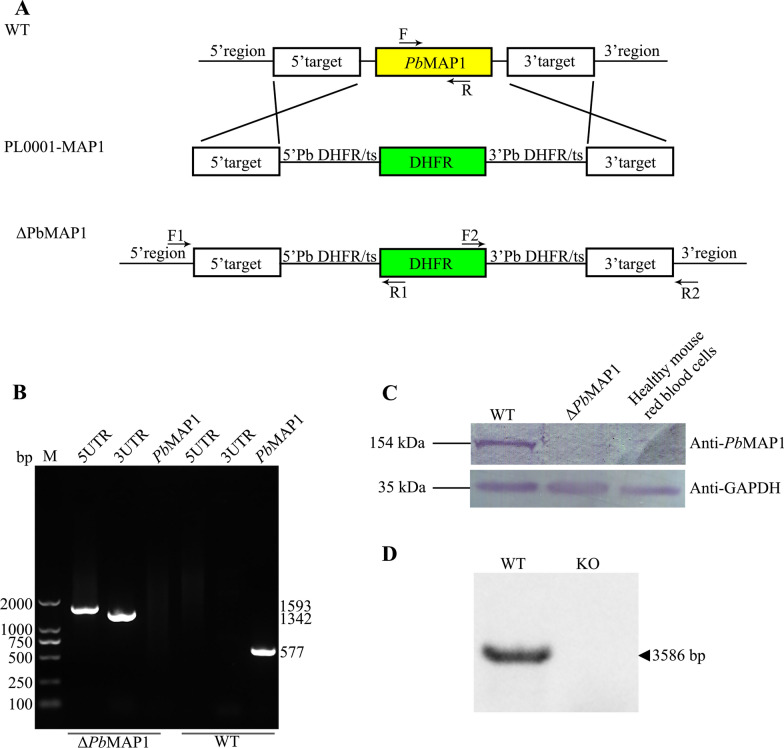

Establishment of a PbMAP1-knockout (ΔPbMAP1) strain

We examined whether PbMAP1 is a key factor for binding to the surface of RBCs by knocking out the PbMAP1 gene from the parasite (Fig. 6A). The knockout strain (ΔPbMAP1) was cloned and verified using PCR with specific primers (Fig. 6B). Moreover, western blotting confirmed virtually complete deletion of PbMAP1 (Fig. 6C), and no signal was detectable in southern blotting in the ΔPbMAP1 strain (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Construction of a PbMAP1-knockout strain (ΔPbMAP1). A Scheme of the transfection plasmid used to target and knock out PbMAP1 in the PbANKA strain using the double-crossover method. B PCR validation of PbMAP1 deletion. PCR products from 5'-UTR, 3′-UTR, and PbMAP1 showed that PbMAP1 was replaced by DHFR. C Western blotting of PbMAP1 expression in WT and ΔPbMAP1. Protein bands with expected molecular weights are shown. No PbMAP1 protein was detected in the knockout strain. GAPDH was used as the control. D Southern blotting using a DNA probe from the PbMAP1 gene in WT and ΔPbMAP1. The gene encoding PbMAP1 was completely deleted in the knockout strain

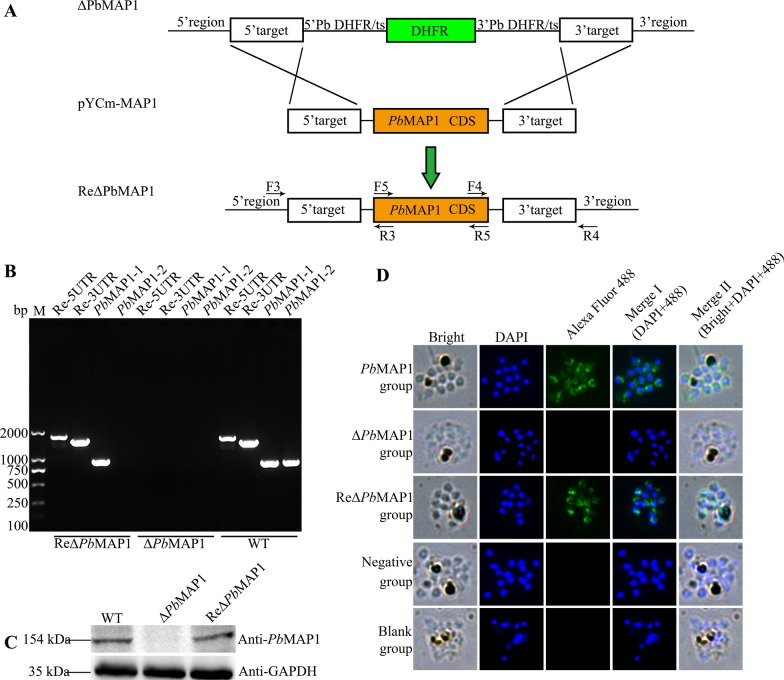

Construction of the PbMAP1 gene re-complement (ReΔPbMAP1) strain

To demonstrate that the phenotype defect was due to the deletion of the gene coding for PbMAP1, we re-introduced the PbMAP1 gene without intron at the endogenous PbMAP1 locus in the ΔPbMAP1 parasite (Fig. 7A). The gene complemented parasite (ReΔPbMAP1) was cloned and verified using PCR with specific primers (Fig. 7B). Western blotting and IFA also confirmed PbMAP1 expression in the ReΔPbMAP1 strain (Fig. 7C, D).

Fig. 7.

Construction of the PbMAP1-complemented strain (ReΔPbMAP1). A Scheme of the transfection plasmid used to target and re-introduce PbMAP1 gene in ΔPbMAP1 using the CRISPR/Cas9 method. B PCR validation of PbMAP1 reintroduction. PCR products from 5′-UTR, 3′-UTR, and PbMAP1 showed that PbMAP1 was re-introduced. C Western blotting of PbMAP1 expression in ΔPbMAP1 and ReΔPbMAP1. No protein band with expected molecular weight was detected in the ΔPbMAP1 strain, but in the ReΔPbMAP1 strain; GAPDH was used as the control. D IFA using rat anti-PbMAP1 IgG to detect PbMAP1 expression. PbMAP1 was detected in WT and ReΔPbMAP1 but not in the ΔPbMAP1 strain

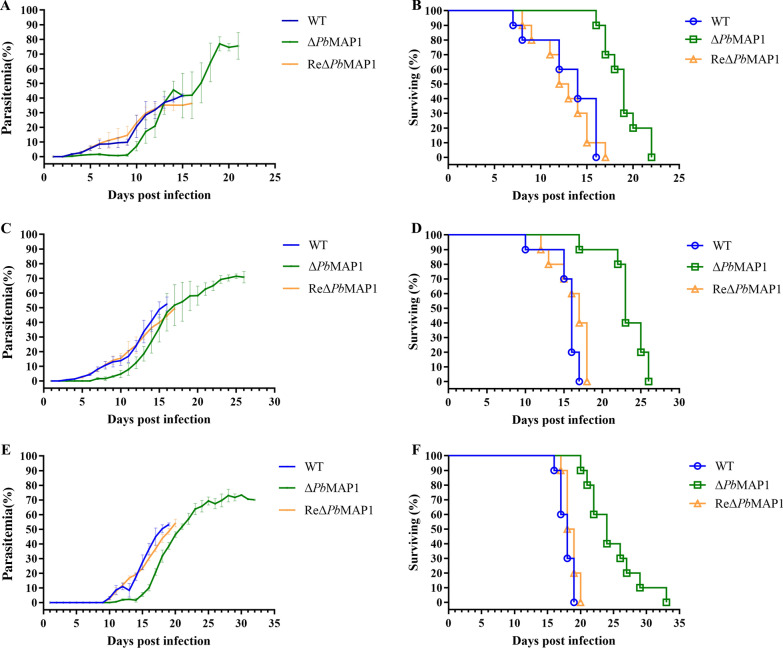

Deletion of PbMAP1 led to virulence deficiency

To investigate the correlation of the PbMAP1 with parasite infectivity, we infected mice with WT PbMAP1, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 at 1 × 106 parasites per mouse. Tail blood was analyzed daily post-infection using Giemsa-stained smears, which revealed that the degree of parasitemia in mice infected with the ΔPbMAP1 parasites was lower than that in mice infected with WT parasites. Moreover, the survival time of these mice was monitored. Mice infected with ΔPbMAP1 parasites died 4–10 days later than those infected with WT. All mice died of severe anemia (Fig. 8A, B). A similar phenomenon was noted in mice infected with WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 when infected with 1 × 103 or 1 × 104 parasites per mouse (Fig. 8C–F).

Fig. 8.

PbMAP1 deletion reduced the infectivity of PbMAP1. A and B Parasitemia and survival curves of BALB/c mice after intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 106 WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 parasites. C and D Parasitemia and survival curves of BALB/c mice after intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 104 WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 parasites. E and F Parasitemia in and survival curves of BALB/c mice after intraperitoneal infection with 1 × 103 WT, ΔPbMAP1, or ReΔPbMAP1 parasites.

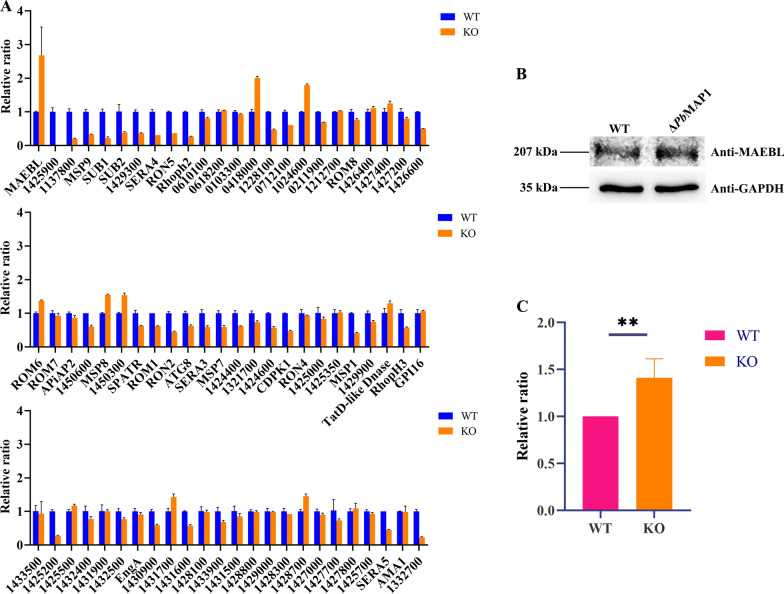

Interestingly, as the parasites continued to divide and proliferate, their virulence appeared to recover. To confirm that the phenomenon of virulence recovery was the result of PbMAP1 knockout, qRT-PCR was performed on specific genes in the WT and ΔPbMAP1 parasites (Fig. 9A). Compared with WT, PbMAP1-knockout strains showed significantly upregulated transcript levels of MAEBL gene coding for the merozoite adhesive erythrocytic binding protein (MAEBL), and significantly downregulated transcript levels of 10 other genes, suggesting a complementary association between PbMAP1 and MAEBL. Western blotting showed that the expression level of the MAEBL protein in ΔPbMAP1 strains was higher than that in WT strains (Fig. 9B, C).

Fig. 9.

Transcription analysis of invasion-related genes in the ΔPbMAP1 parasites with qRT-PCR. A Transcription of MAEBL was significantly upregulated in ΔPbMAP1 strains compared to that in the wild-type strain. B and C Expression of MAEBL protein in ΔPbMAP1 strains was positively correlated with transcription levels. Experiments were repeated three times. Error bars represent SD

Infection with ΔPbMAP1 induced stronger IFN-γ and TNF-α responses in infected mice

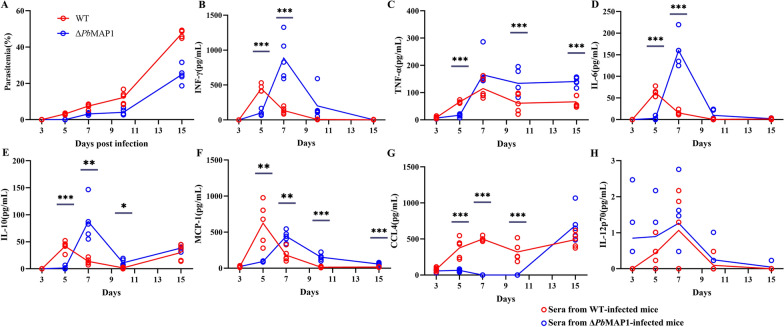

To explore the impact of the PbMAP1 on the outcome of blood-stage infection, we infected mice with either WT- or ΔPbMAP1-infected RBCs at 1 × 104 parasites per mouse and characterized the early immune response in WT- or ΔPbMAP1-infected mice. We collected sera on days 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 after infection and assayed the samples for expression of various cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 10A). The serum levels of IFN-γ were higher in ΔPbMAP1-infected mice than the peak levels in the WT-infected mice, and peak levels were recorded on day 7 after infection (Fig. 10B). Similarly, on day 7 after infection, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 were higher in ΔPbMAP1-infected mice (Fig. 10C–E). Conversely, on day 7 after infection, the levels of MCP-1 and CCL4 were higher in WT-infected mice than in ΔPbMAP1-infected mice (Fig. 10F, G). Over the infection time, the levels of CCL4 became equivalent in the two groups and continued to increase until day 10 after infection. Similarly, IL-12p70 levels increased with the progression of infection, although no significant differences were noted between the two groups (Fig. 10H).

Fig. 10.

ΔPbMAP1 infection induced stronger IFN-γ and TNF-α responses in infected mice. A BALB/c mice were infected with either ΔPbMAP1 or WT using 1 × 104 iRBCs per mouse intraperitoneally. Parasitemia was monitored during the course of infection. Each circle represents an individual mouse. Analyses were performed with five animals per group. B–H Sera collected from infected mice at different time points. Time-dependent changes in serum levels of various cytokines and chemokines as quantified using a bead array (BD). Each circle refers to the response of a mouse, and lines indicate mean values. Statistically significant differences are shown with asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001)

Discussion

The invasion of Plasmodium into RBCs is a rapid and complex process that involves RBC adhesion, apical reorientation, mobile junction complex, and parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) formation and modification in a series of dynamic steps [24–26]. The key proteins associated with RBC parasite invasion include various proteins located on the merozoite surface, in micronemes, rhoptries, and dense granules [27–29]. When a merozoite invades RBCs, the parasite’s surface proteins bind to RBC surface receptors, increasing calcium concentration in the cytoplasm of the parasite; this in turn stimulates the secretion of microneme proteins, such as TRAP, which plays an important role in the gliding motility and invasion, leading to a series of invasion steps [30–34]. Therefore, adhesion is the first step for Plasmodium to invade RBCs, and proteins located on the surface of merozoites play pivotal roles in the process of invasion. However, specific surface proteins that bind to RBCs have not been fully characterized, and these proteins may be important virulence factors in the process of infection.

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are long linear carbohydrate chains that are attached to the core proteins to form proteoglycans. HS is a GAG and comprises alternating glucosamine and uronic acid residues in the repeated disaccharide unit (-4GlcAβ1-4GlcNAcα1-) [6, 14, 35]. HS is localized to the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix of many tissues, and it is implicated in multiple aspects of the Plasmodium life cycle [36, 37]. As such, HS is the major receptor for Plasmodium invading RBCs [38–41].

Early studies reported that peptides that can bind to heparin contain one or more consistent heparin-binding motifs, namely [-X-B-B-X-B-X-] or [- X-B-B-B-X-X-B-X-], where B is the basic residue of basic amino acids, such as lysine, arginine, and histidine, and X is a hydrophilic amino acid residue [42]. Previous studies on P. falciparum indicated that the binding of PfEMP1 to HS receptor on RBCs relies on the presence of multiple heparin-binding motifs in the DBLα region [39]. In the present study, we identified a novel protein, PbMAP1, which contains heparin-binding motifs, indicating that PbMAP1 can potentially bind HS-like receptor. Therefore, the binding of PbMAP1 to the RBCs surface receptor was investigated.

Specifically, our IFA and electron microscopy demonstrated that PbMAP1 is expressed on the surface of P. berghei. As a surface protein, PbMAP1 may be involved in the interaction between the parasite and RBC surface receptors. Based on three-dimensional (3D) structural modeling of PbMAP1 and its heparin-binding motifs, we expressed and purified the recombinant protein GST-PbMAP1 in Escherichia coli and used the GST protein as the negative control for functional verification. Heparin-binding and competitive inhibition experiments showed that GST-PbMAP1 could bind to heparin in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2). IFA, western blotting, and flow cytometry further indicated that the PbMAP1 protein could bind to the surface of RBCs (Fig. 3). Therefore, PbMAP1 may be involved in binding to HS-like receptor on the RBC surface.

Furthermore, PbMAP1 was knocked out to assess its function. We found that the pathogenicity of the ΔPbMAP1 strain in mice was attenuated compared to that of the WT strain (Fig. 8). The use of PbMAP1-knockout strain further demonstrated the role of the PbMAP1 protein in the binding to RBCs. In addition, we observed that mice immunized with PbMAP1-specific peptides achieved immune protection (Fig. 5). Therefore, PbMAP1 may play important roles in the binding and invasion of P. berghei to RBCs. Interestingly, we found that with the continuous replication of the parasites, the infectivity of the ΔPbMAP1 parasite seemed recovered. Therefore, we speculated that some ways of compensation may occur. We collected WT and ΔPbMAP1 strains and searched for genes with significant differences in transcript levels after PbMAP1 knockout using qRT-PCR. The transcript level of MAEBL was surprisingly found significantly upregulated, but the transcript levels of 10 other merozoite genes were significantly downregulated. These results confirmed that PbMAP1 knockout affected MAEBL expression (Fig. 8).

To assess the potential mechanism through which injection with the ΔPbMAP1 strain can confer immune protection in mice, we examined changes in cytokine levels after immunizing with the ΔPbMAP1 strains. Levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10, which are important for the activation of protective immunity, were significantly increased at the early stage of ΔPbMAP1 infection. Therefore, PbMAP1 expression is likely beneficial to the parasite by preventing protective immune responses in the host.

Conclusion

The present study showed that the surface protein PbMAP1 is involved in the binding of P. berghei to the HS receptor on RBC surface. The absence of PbMAP1 is presumably deleterious to the parasite, as it evokes a specific immune response in the host. Our findings revealed the interaction between PbMAP1, a novel P. berghei surface protein, and HS-like receptor during invasion. Simultaneously, these findings can be useful approaches for deep characterization of P. falciparum proteins in human malaria.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primer sequences referred to in this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Nature and Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82030060) and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (grant no. 2019-I2M-5-042).

Abbreviations

- RBCs

Red blood cells

- PbANKA

Plasmodium berghei ANKA

- HS

Heparan sulfate

- GAGs

Glycosaminoglycans

- MSP

Merozoite surface protein

- EBL

Erythrocyte binding antigens

- MAEBL

Merozoite adhesive erythrocytic binding protein

- IP

Intraperitoneal

- PBS

Phosphate buffer saline

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- HS

Heparan sulfate

- CSA

Chondroitin sulfate A

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- DAPI

2′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- IV

Intravenous

- WT

Wildtype

- IFN-γ

Interferon gamma

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- IL

Interleukin

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- CCL4

Macrophage inflammatory protein-1β

Author contributions

JG performed most experiments, analyzed that data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NJ mentored all experimental work. YZ assisted with the parasite proliferation and bioinformatics analysis. RC assisted with the immunological analysis. YF assisted with the immunofluorescence experiments. XS assisted with the cell adhesion experiments. QC conceived the study, analyzed the data, and finalized the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal protocols and procedures were performed according to the regulations of the Animal Ethics Committee of the Shenyang Agricultural University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: World malaria report 2021. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2021/report/en/

- 2.Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–9. doi: 10.1038/415673a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaur D, Mayer DCG, Miller LH. Parasite ligand–host receptor interactions during invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium merozoites. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1413–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilson PR, Nebl T, Vukcevic D, Moritz RL, Sargeant T, Speed TP, et al. Identification and stoichiometry of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane proteins of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1286–99. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600035-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi K, Kato K, Sugi T, Yamane D, Shimojima M, Tohya Y, et al. Application of retrovirus-mediated expression cloning for receptor screening of a parasite. Anal Biochem. 2009;389:80–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann R, Werner C, Sterling J. Exploring structure–property relationships of GAGs to tailor ECM-mimicking hydrogels. Polymers (Basel). 2018;10:1376. doi: 10.3390/polym10121376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasti N, Wahlgren M, Chen Q. Molecular aspects of malaria pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;41:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima M, Rudd T, Yates E. New applications of heparin and other glycosaminoglycans. Molecules. 2017;22:749. doi: 10.3390/molecules22050749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogt AM, Pettersson F, Moll K, Jonsson C, Normark J, Ribacke U, et al. Release of sequestered malaria parasites upon injection of a glycosaminoglycan. PloS Pathog. 2006;2:e100. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carruthers VB, Håkansson S, Giddings OK, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma gondii uses sulfated proteoglycans for substrate and host cell attachment. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4005–11. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4005-4011.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle MJ, Richards JS, Gilson PR, Chai W, Beeson JG. Interactions with heparin-like molecules during erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Blood. 2010;115:4559–68. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azzouz N, Kamena F, Laurino P, Kikkeri R, Mercier C, Cesbron-Delauw M, et al. Toxoplasma gondii secretory proteins bind to sulfated heparin structures. Glycobiology. 2013;23:106–20. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Q, Barragan A, Fernandez V, Sundström A, Schlichtherle M, Sahlén A, et al. Identification of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane proteins 1 (PfEMP1) as the rosetting ligand of the malaria parasite P. falciparum. J Exp Med. 1998;187:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogt AM, Barragan A, Chen Q, Kironde F, Spillmann D, Wahlgren M. Heparan sulfate on endothelial cells mediates the binding of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes via the DBL1alpha domain of PfEMP1. Blood. 2003;101:2405–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi K, Kato K, Sugi T, Takemae H, Pandey K, Gong H, et al. Plasmodium falciparum BAEBL binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the human erythrocyte surface. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1716–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baum J, Chen L, Healer J, Lopaticki S, Boyle M, Triglia T, et al. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 5 – an essential adhesin involved in invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:371–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao L, Yang C, Patterson PS, Udhayakumar V, Lal AA. Sulfated polyanions inhibit invasion of erythrocytes by plasmodial merozoites and cytoadherence of endothelial cells to parasitized erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1373–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1373-1378.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanni LA, Fonseca LF, Langhorne J. Mouse models for erythrocytic-stage malaria. Methods Mol Med. 2002;72:57–76. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-271-6:57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, et al. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D539–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang D, Jiang N, Chen Q. ROP9, MIC3, and SAG2 are heparin-binding proteins in Toxoplasma gondii and involved in host cell attachment and invasion. Acta Trop. 2019;192:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goel VK, Li X, Chen H, Liu S-C, Chishti AH, Oh SS. Band3 is a host receptor binding merozoite surface protein 1 during the Plasmodium falciparum invasion of erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5164–69. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0834959100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janse CJ, Ramesar J, Waters AP. High-efficiency transfection and drug selection of genetically transformed blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:346–56. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyes S, Pinches R, Newbold C. A simple RNA analysis method shows var and rif multigene family expression patterns in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;105:311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilson PR, Crabb BS. Morphology and kinetics of the three distinct phases of red blood cell invasion by Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aikawa M, Miller LH, Johnson J, Rabbege J. Erythrocyte entry by malarial parasites. A moving junction between erythrocyte and parasite. J Cell Biol. 1978;77:72–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.77.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cowman AF, Crabb BS. Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell. 2006;124:755–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sam-Yellowe TY. Rhoptry organelles of the apicomplexa: their role in host cell invasion and intracellular survival. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:308–16. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)10030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowman AF, Tonkin CJ, Tham WH, Duraisingh MT. The molecular basis of erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:232–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao X, Chang Z, Tu Z, Yu S, Wei X, Zhou J, et al. PfRON3 is an erythrocyte-binding protein and a potential blood-stage vaccine candidate antigen. Malar J. 2014;13:490. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sultan AA, Thathy V, Frevert U, Robson KJH, Crisanti A, Nussenzweig V, et al. TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. 1997;90:511–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bargieri DY, Thiberge S, Tay CL, Carey AF, Rantz A, Hischen F, et al. Plasmodium merozoite TRAP family protein is essential for vacuole membrane disruption and gamete egress from erythrocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:618–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buscaglia CA, Coppens I, Hol WGJ, Nussenzweig V. Sites of interaction between aldolase and thrombospondin-related anonymous protein in plasmodium. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4947–57. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovett JL, Sibley LD. Intracellular calcium stores in Toxoplasma gondii govern invasion of host cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3009–16. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Billker O, Lourido S, Sibley LD. Calcium-dependent signaling and kinases in apicomplexan parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:612–22. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dennissen MABA, Jenniskens GJ, Pieffers M, Versteeg EMM, Petitou M, Veerkamp JH, et al. Large, tissue-regulated domain diversity of heparan sulfates demonstrated by phage display antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10982–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McQuaid F, Rowe JA. Rosetting revisited: a critical look at the evidence for host erythrocyte receptors in Plasmodium falciparum rosetting. Parasitology. 2020;147:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0031182019001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams Y, Kuhnrae P, Higgins MK, Ghumra A, Rowe JA. Rosetting Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes bind to human brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro, demonstrating a dual adhesion phenotype mediated by distinct P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 domains. Infect Immun. 2014;82:949–59. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01233-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Jiang N, Lu H, Hou N, Piao X, Cai P, et al. Proteomic analysis of Plasmodium falciparum schizonts reveals heparin-binding merozoite proteins. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:2185–93. doi: 10.1021/pr400038j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barragan A, Fernandez V, Chen Q, von Euler A, Wahlgren M, Spillmann D. The Duffy-binding-like domain 1 of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) is a heparan sulfate ligand that requires 12 mers for binding. Blood. 2000;95:3594–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi K, Kato K. Evaluating the use of heparin for synchronization of in vitro culture of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Int. 2016;65:549–51. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss GE, Gilson PR, Taechalertpaisarn T, Tham WH, de Jong NWM, Harvey KL, et al. Revealing the sequence and resulting cellular morphology of receptor–ligand interactions during Plasmodium falciparum invasion of erythrocytes. PLOS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004670. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardin AD, Weintraub HJ. Molecular modeling of protein–glycosaminoglycan interactions. Arterioscler Dallas Tex. 1989;9:21–32. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primer sequences referred to in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.