Abstract

Study Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Objectives:

The interactions between hip osteoarthritis (OA) and spinal malalignment are poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to assess the influence of total hip arthroplasty (THA) on standing spinopelvic alignment.

Methods:

In this retrospective cohort study, patients undergoing THA for OA with pre-and postoperative full-body radiographs were included. Standing spinopelvic parameters were measured. Contralateral hip was graded on the Kellgren-Lawrence scale. Pre-and postoperative alignment parameters were compared by paired t-test. The severity of preoperative thoracolumbar deformity was measured using TPA. Linear regression was performed to assess the impact of preoperative TPA and changes in spinal alignment. Patients were separated into low and high TPA (<20 or >/=20 deg) and change in parameters were compared between groups by t-test. Similarly, the influence of K-L grade, age, and PI were also tested.

Results:

95 patients were included (mean age 58.6 yrs, BMI 28.7 kg/m2, 48.2% F). Follow-up radiographs were performed at mean 220 days. Overall, the following significant changes were found from pre-to postoperative: SPT (14.2 vs. 16.1, P = 0.021), CL (−8.9 vs. −5.3, P = .001), TS-CL (18.2 vs. 20.5, P = .037) and SVA (42.6 vs. 32.1, P = .004). Preoperative TPA was significantly associated with the change in PI-LL, SVA, and TPA. High TPA patients significantly decreased SVA more than low TPA patients. There was no significant impact of contralateral hip OA, PI, or age on change in alignment parameters.

Conclusion:

Spinopelvic alignment changes after THA, evident by a reduction in SVA. Preoperative spinal sagittal deformity impacts this change. Level of evidence: III.

Keywords: total hip arthroplasty, spinal deformity, spinal alignment, alignment parameters

Introduction

Both hip osteoarthritis (OA) and lumbar spine disease are 2 of the most common indications to undergo orthopaedic surgery. The concurrence of hip disease and spine disease, coined “hip-spine syndrome”, was originally described by Offierski and MacNab in 1983 and was based on the clinical observation of the improvement in LBP after total hip arthroplasty (THA). 1 It is thought that severe hip osteoarthritis (OA) may contribute to spinal malalignment, and thus treating hip OA might improve LBP.

Hip OA typically causes a hip flexion contracture and pelvic anteversion (reduced spinopelvic tilt [SPT]), and subsequent hyperextension of the lumbar spine as a compensatory mechanism to maintain upright posture. 2 More recent studies have quantified the relationship between pelvic and spine biomechanics. 3 Hip OA patients have been shown to have a higher sacral slope (SS) and lower SPT, and have a higher incidence global spinal malalignment. 4 In patients with spinal malalignment, hip arthritis may play a more debilitating role in overall global alignment, due to the combined inability of the pelvis to retrovert (increase SPT) and the lumbar spine to increase its lordosis. The impact of THA on spinopelvic alignment is unclear. The purpose of this study was to examine (1) differences in standing spinopelvic alignment before and after THA and (2) the influence of preoperative spinal sagittal malalignment in this setting.

Methods

This was an institutional review board (IRB) approved retrospective cohort study at a single academic center. Patients who underwent THA for osteoarthritis (OA) with both preoperative and postoperative (within 2 years) standing full body radiographs were included. Demographic and surgical data was collected and included date of surgery, approach, time of follow up radiographs, age, gender, and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2).

All patients underwent low-dose radiation biplanar stereoradiographic images (EOS imaging, Paris, France). 5 Patients underwent imaging in a weight-bearing free standing position with the arms flexed at 45 degrees as to avoid superimposition of the arms with the spine. 6

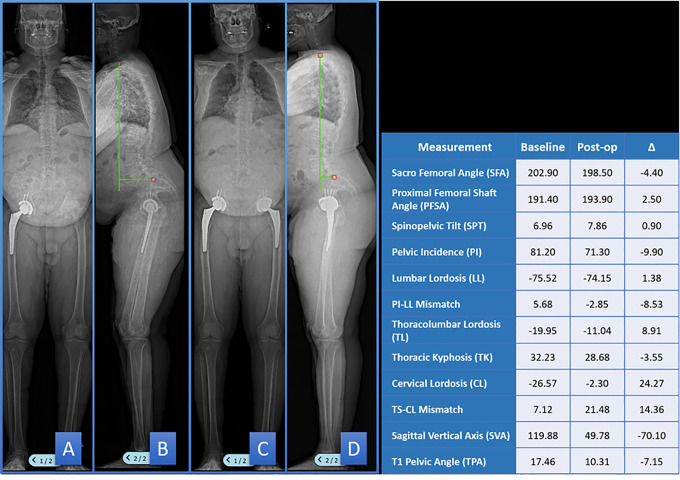

Each radiograph was measured using a validated measurement software (Surgimap, Nemaris, Inc., New York, USA). 7 Global spinal alignment parameters included: sagittal vertical axis (SVA, horizontal offset from a C7 plumbline to the posterosuperior corner of S1, mm) and T1 pelvic angle (TPA, angle between the line from the femoral head axis to the center of the T1 vertebra and the line from the femoral head axis to the middle of the S1 superior endplate, degrees). 8 Regional spinopelvic parameters included: spinopelvic tilt (SPT, angle between a line from the bicoxofemoral axis to the midpoint of the sacral endplate and a vertical line, degrees), pelvic incidence (PI, angle between a line from the bicoxofemoral axis to the midpoint of the sacral endplate and a line perpendicular to the sacral endplate, degrees), lumbar lordosis (LL, Cobb angle between the superior endplate of L1 and the superior endplate of S1, degrees), thoracic kyphosis (TK, Cobb angle between superior endplate of T4 and T12 vertebrae, degrees), cervical lordosis (CL, Cobb angle between the inferior endplate of C2 and the inferior endplate of C7, degrees), and T1slope—cervical lordosis (T1S-CL, degrees). Of note, we use the term SPT to measure sagittal pelvic orientation to differentiate from the measurement performed typically by hip surgeons, the anterior pelvic plane tilt. 9 Lower extremity parameters included: proximal femoral shaft angle (PFSA, angle between the axis of the proximal femoral shafts and the vertical, degrees) and sacrofemoral angle (SFA, angle between the line from the bicoxofemoral axis to the midpoint of the superior endplate of S1 and the line from the bicoxofemoral axis to the femorocondylar axis, degrees). (Figure 1). Lordosis was measured as a negative value and kyphosis was measured as a positive value.

Figure 1.

Summary of radiographic measurements performed. SPT—pelvic tilt; PI—pelvic incidence; LL—lumbar lordosis; TK—thoracic kyphosis; CL—cervical lordosis; TS-CL—T1slope—cervical lordosis; SVA—sagittal vertical axis; TPA—T1 pelvic angle; SFA—sacrofemoral angle; PSFA—proximal femoral shaft angle.

The severity of OA in the contralateral, nonoperative hip was graded according to the Kellgren-Lawrence system. 10 If the patient had a contralateral THA, this was noted.

Statistical Analysis

Pre-and postoperative alignment parameters were compared by paired t-test.

The impact of preoperative thoracolumbar deformity was assessed. First, linear regression was performed between change in each alignment parameter and preoperative TPA. Second, patients were separated into low and high TPA (<20 or >/=20 deg) and the same parameters were compared between groups by 2-tailed Students t-test. Similarly, patients were also separated into PI-LL mismatch (>10) and no PI-LL mismatch (<10), and the same parameters were compared.

The impact of contralateral hip OA was assessed in the following manner: patients were separated into groups based on contralateral hip K-L score (Low hip OA: THA, 0, 1, or 2 vs. high hip OA: 3 or 4), and the same alignment parameters were compared between groups. The impact of preoperative PI was assessed by comparing change in alignment parameters between patients with low PI (<45) and high PI (>60), The impact of age was assessed by performing linear regression between change in each alignment parameter and age.

All analyses were performed with Stata 15.0 (Statacorp, College Station, Tx). Level of significance was set to P < 0.05.

Results

There were 95 patients included (mean age 58.6 yrs, 48.2% F, mean body mass index 28.7 kg/m2). Average time point for follow up x-rays was 209 days. Thirteen patients underwent an anterior approach, 67 a posterior approach, 10 a direct lateral approach, and 5 patients were unknown.

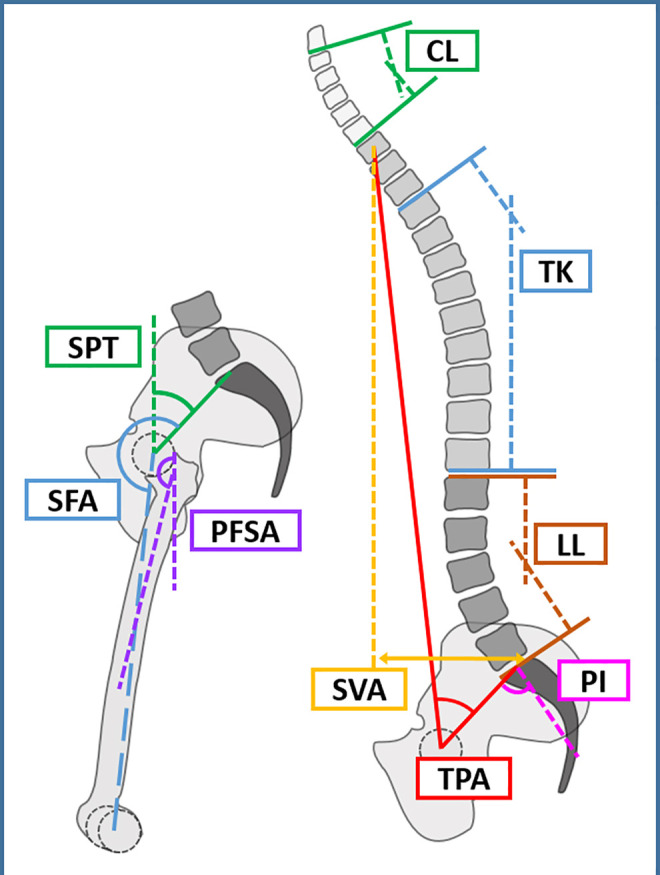

Overall, the following significant changes were found from preoperative to postoperative: SPT (14.2 vs. 16.1, P = 0.021), CL (−8.9 vs. −5.3, P = .001), TS-CL (18.2 vs. 20.5, P = .037) and SVA (42.6 vs. 32.1, P = .004). (Table 1). Figure 2 shows an example patient that demonstrates the decrease in SVA with THA.

Table 1.

Summary of Radiographic Results.

| Mean values of parameters | Correlation of change in parameter with preoperative TPA | Change in parameters based on TPA group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Change | P value | Coeff. | R2 | P value | Low TPA | High TPA | P value | |

| SPT | 14.17 | 16.09 | 1.92 | 0.021 | −0.14 | 0.03 | 0.095 | 2.08 | 1.33 | 0.70 |

| PI | 52.48 | 52.17 | −0.31 | 0.68 | −0.088 | 0.01 | 0.278 | −0.32 | −0.29 | 0.98 |

| LL | −50.51 | −49.38 | 1.13 | 0.23 | −0.17 | 0.03 | 0.085 | 1.69 | −0.85 | 0.27 |

| PI-LL | 1.97 | 2.79 | 0.82 | 0.37 | −0.26 | 0.07 | 0.007 | 1.34 | −1.14 | 0.26 |

| T10-L2 | 2.90 | 3.79 | 0.87 | 0.23 | −0.02 | 0.001 | 0.727 | 1.06 | 0.22 | 0.62 |

| TK | 35.49 | 35.06 | −0.44 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.112 | −0.69 | 0.48 | 0.62 |

| CL | −8.93 | −5.26 | 3.66 | 0.0014 | −0.066 | 0.003 | 0.576 | 3.70 | 3.40 | 0.90 |

| TS-CL | 18.20 | 20.52 | 2.35 | 0.037 | −0.18 | 0.03 | 0.105 | 3.10 | −0.11 | 0.22 |

| SVA | 42.59 | 32.14 | −10.44 | 0.004 | −0.94 | 0.07 | 0.011 | −6.60 | −23.65 | 0.046 |

| TPA | 13.80 | 14.23 | 0.43 | 0.52 | −0.22 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.98 | −1.51 | 0.12 |

| SFA | 198.51 | 199.86 | 1.32 | 0.09 | 0.46 | 0.004 | 0.57 | 1.22 | 1.65 | 0.78 |

| PSFA | 182.21 | 182.03 | −0.22 | 0.89 | 0.21 | 0.015 | 0.23 | −1.16 | 3.04 | 0.30 |

Abbreviations: SPT—spinopelvic tilt, degrees; PI—pelvic incidence, degrees; LL—lumbar lordosis, degrees; TK—thoracic kyphosis, degrees; CL—cervical lordosis; TS-CL—T1slope—cervical lordosis, degrees; SVA—sagittal vertical axis, mm; TPA—T1 pelvic angle, degrees, SFA—sacrofemoral angle, degrees; PSFA—proximal femoral shaft angle, degrees.

Figure 2.

Example patient—full body EOS radiographs preoperatively (A, B) and post-operatively (C, D) after total hip arthroplasty. The pre-and post-operative spinopelvic measurements are displayed in the table. Note the reduction in SVA after THA.

On regression analysis, preoperative TPA was associated with the change in PI-LL, SVA, and TPA from pre-to post-THA. Increasing TPA was correlated with decreasing PI-LL and decreasing global sagittal malalignment as measured by SVA and TPA. In comparing high TPA patients (n =21) to low TPA patients (n = 74), high TPA patients significantly decreased SVA more than low TPA patients.

There were no significant differences between PI-LL groups. Regarding the influence of contralateral hip OA on the change in parameters, there were 27 patients in the high grade contralateral hip OA group, and 68 patients in the low grade group. There were no significant differences between contralateral hip OA graded groups. There were 20 patients in the low PI group and 19 patients in the high PI group (the remaining 56 patients had a PI in the normal range, 45-60); there were no significant differences between groups. There were no significant correlations between age and change in standing alignment parameters (data not shown).

Discussion

Understanding the changes in spinopelvic alignment after THA is critical when considering undergoing this procedure. This study confirms prior literature regarding these changes. Importantly, additionally, this study for the first time examines the interplay between spinal deformity and hip disease and how preoperative spinal deformity impacts the change in spinopelvic alignment with THA.

Overall, we demonstrated a significant decrease in SVA and increased SPT after THA in the present study. Prior studies have demonstrated similar findings. Piazzolla found in a cohort of patients with low back pack pain, THA resulted in improvement in sagittal spinal alignment parameters including decrease in SVA and TPA. 11 Another study by Kim et al also showed decrease in SVA after THA, and in particular, found the SVA changes to present in the low and medium PI patients but not the high PI patients. 12 The present study was unable to demonstrate a difference between PI groups and change in global alignment parameters. This seemingly conflicting finding can be attributed to the fact that Kim et al did not perform any comparison in alignment parameters between PI groups, and thus could not conclude that PI significantly influenced alignment changes. Prior studies that failed to demonstrate a change in spinal alignment parameters were limited by lack examination of global alignment parameters and focused solely on LL, as well as small sample groups of 12-30 patients.13-16

We concurrently demonstrated a small but statistically significant increase in SPT post THA, representing an increased ability to retrovert the pelvis after THA. This finding contributes to the decrease in SVA as no other thoracolumbar alignment parameters significantly changed after THA. Patients with hip OA have a fixed hip flexion contracture, which may be physical from soft tissue tightness or bony overgrowth, or perhaps functional from pain. This inability to extend the hip prevents the patient from increasing SPT, and thus patients with hip OA have a higher SVA for a given TPA. 4 The ability to extend the hips after THA allows for restoration of terminal hip extension, with subsequent retroversion of the pelvis (increasing SPT) and reduction in SVA. Of note, while there was an increase in SFA with THA, we were unable to demonstrate a significant change. This may represent a type II (beta) error.

We further found that increasing preoperative sagittal malalignment, as measured by TPA, was significantly associated improvement in global spinal alignment parameters, as measured by SVA and TPA, as well as PI-LL mismatch after THA. This quantitative radiographic relationship between preoperative sagittal malaligment and change in spinopelvic parameters with THA is the first of its kind. Importantly, TPA is a measure of thoracolumbar sagittal alignment that isolates the spine from other compensatory mechanisms of the pelvis or lower extremities, whereas SVA is influenced by SPT and knee flexion angles. Day et al examined the influence of hip OA specifically in patients with spinal deformity, and found that high-grade OA patients had less pelvic tilt, less thoracic kyphosis, and greater SVA than low-grade OA patients. 17 Linking these 2 findings together, deformity patients (patients with high TPA) who have an inability to hyperlordose the lumbar spine rely on pelvic retroversion more so than non-deformity patients; thus it follows that restoration of the ability to retrovert the pelvis with THA would have a greater impact in maintaining upright posture in deformity patients. In the non-deformed patient, the lumbar lordosis may relax once SPT has been restored. Unfortunately, given that there were only 21 patients in the high TPA group, the study was likely underpowered to show regional differences.

We were surprised to find that contralateral hip OA did not impact the change in alignment parameters after undergoing THA. This may be due to confounding factors. The cause for a preoperative hip flexion contracture maybe multifold. It maybe structural due to soft tissue tightness or bony impingement, or it may functional due to pain. Presumably, if the patient has bilateral hip OA, the patient will undergo THA on the side that is more symptomatic. It may be that despite the severe OA on the contralateral side, the patient does not have as much pain on the contralateral side, and as such, hip flexion contracture on the contralateral side may not play such a substantial role.

Importantly, the associations described above, while present, are weak. For example, the R2 value of association of preoperative TPA with the change in SVA is 0.11, which can be interpreted to mean that only approximately 10% of the variation in change in SVA can be attributed to the preoperative TPA. This finding suggests that while preoperative spinal deformity plays a role in the change in spinal alignment with THA, there are likely many other factors that are contributing that were not examined by this study.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we did not examine health related quality of life (HRQoL) scores that were either spine specific or hip specific, which would enhance the findings of this study. Second, the patient population was small, limiting the interpretation of non-significant findings (type II error). Thus, there may be additional relationships between these complex variables that we were unable to demonstrate. In particular, while the overall analysis did not demonstrate an influential role of contralateral hip OA on alignment parameter changes with THA, it would be interesting to examine the impact of contralateral hip OA specifically in the deformity group.

Conclusion

THA overall decreases global sagittal spinal malalignment, which is of particular interest in patients with concomitant hip OA and spinal deformity. Furthermore, patients with greater sagittal malalignment preoperatively experience greater improvement in their global spinal alignment with THA. The mechanisms by which this occurs remains unclear; future studies with larger cohorts of patients may examine the influence of other regional spinopelvic and regional alignment parameters specifically in deformity patients.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Deeptee Jain, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9576-9722

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9576-9722

Edward M. Delsole, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5893-3434

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5893-3434

Elizabeth Lord, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2433-2475

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2433-2475

Themistocles Protopsaltis, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4978-2600

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4978-2600

References

- 1.Offierski CM, MacNab I. Hip-spine syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8(3):316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurwitz DE, Hulet CH, Andriacchi TP, Rosenberg AG, Galante JO. Gait compensations in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and their relationship to pain and passive hip motion. J Orthop Res. 1997;15(4):629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckland AJ, Vigdorchik J, Schwab FJ, et al. Acetabular anteversion changes due to spinal deformity correction: bridging the gap between hip and spine surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(23):1913–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weng WJ, Wang WJ, Wu MD, Xu ZH, Xu LL, Qiu Y. Characteristics of sagittal spine-pelvis-leg alignment in patients with severe hip osteoarthritis. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(6):1228–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wade R, Yang H, McKenna C, Faria R, Gummerson N, Woolacott N. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of EOS 2D/3D X-ray imaging system. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(2):296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton WC, Brown CW, Bridwell KH, Glassman SD, Suk SI, Cha CW. Is there an optimal patient stance for obtaining a lateral 36” radiograph? A critical comparison of three techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(4):427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lafage R, Ferrero E, Henry JK, et al. Validation of a new computer-assisted tool to measure spino-pelvic parameters. Spine J. 2015;15(12):2493–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Protopsaltis T, Schwab F, Bronsard N, et al. International Spine Study Group. The T1 pelvic angle, a novel radiographic measure of global sagittal deformity, accounts for both spinal inclination and pelvic tilt and correlates with health-related quality of life. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(19):1631–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckland AJ, DelSole EM, George SG, et al. Sagittal pelvic orientation: a comparison of two methods of measurement. Bull Hosp Jt Dis (2013). 2017;75(4):234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellgren J, Lawrence J. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piazzolla A, Solarino G, Bizzoca D, et al. Spinopelvic parameter changes and low back pain improvement due to femoral neck anteversion in patients with severe unilateral primary hip osteoarthritis undergoing total hip replacement. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(1):125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y, Lazennec J, Hani J, Pour AE. How do global sagittal alignment and posture change after total hip arthroplasty? Orthopaedic Proceedings. The British Editorial Society of Bone & Joint Surgery. 42–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bredow J, Katinakis F, Schlüter-Brust K, et al. Influence of hip replacement on sagittal alignment of the lumbar spine: an EOS study. Technol Health Care. 2015;23(6):847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Galim P, Ben-Galim T, Rand N, et al. Hip-spine syndrome: the effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(19):2099–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eguchi Y, Iida S, Suzuki C, et al. Spinopelvic alignment and low back pain after total hip replacement arthroplasty in patients with severe hip osteoarthritis. Asian Spine J. 2018;12(2):325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radcliff KE, Orozco F, Molby N, et al. Change in spinal alignment after total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Surg. 2013;5(4):261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day LM, DelSole EM, Beaubrun BM, et al. Radiological severity of hip osteoarthritis in patients with adult spinal deformity: the effect on spinopelvic and lower extremity compensatory mechanisms. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(9):2294–2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]