Abstract

Study Design:

Cross-sectional, anonymous, international survey.

Objectives:

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the rapid adoption of telemedicine in spine surgery. This study sought to determine the extent of adoption and global perspectives on telemedicine in spine surgery.

Methods:

All members of AO Spine International were emailed an anonymous survey covering the participant’s experiences with and perceptions of telemedicine. Descriptive statistics were used to depict responses. Responses were compared among regions.

Results:

485 spine surgeons participated in the survey. Telemedicine usage rose from <10.0% to >39.0% of all visits. A majority of providers (60.5%) performed at least one telemedicine visit. The format of “telemedicine” varied widely by region: European (50.0%) and African (45.2%) surgeons were more likely to use phone calls, whereas North (66.7%) and South American (77.0%) surgeons more commonly used video (P < 0.001). North American providers used telemedicine the most during COVID-19 (>60.0% of all visits). 81.9% of all providers “agreed/strongly agreed” telemedicine was easy to use. Respondents tended to “agree” that imaging review, the initial appointment, and postoperative care could be performed using telemedicine. Almost all (95.4%) surgeons preferred at least one in-person visit prior to the day of surgery.

Conclusion:

Our study noted significant geographical differences in the rate of telemedicine adoption and the platform of telemedicine utilized. The results suggest a significant increase in telemedicine utilization, particularly in North America. Spine surgeons found telemedicine feasible for imaging review, initial visits, and follow-up visits although the vast majority still preferred at least one in-person preoperative visit.

Keywords: telemedicine, telehealth, spine, surgery, global, perspectives

Introduction

The global spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and subsequent social distancing mandates have resulted in the broad adoption of telemedicine across nearly all specialties. 1 Telemedicine is a loosely defined term and may refer to any interaction between providers and patients utilizing remote technologies. 2 Examples of these interactions include: video conferences, telephone visits, text-messaging, remote patient monitoring, and augmented/virtual reality.3,4

Prior to COVID-19, few spine practices utilized telemedicine.5-7 Several challenges impeded adoption, including: a lack of perceived benefit, technology implementation costs, difficulty diagnosing musculoskeletal disorders, and concerns regarding reimbursement and liability. 8 During the pandemic, however, as many as 35.6% of spine surgeons worldwide were performing over half of their clinical visits via telemedicine. 9 This abrupt shift in practice patterns has placed surgeons into mostly unfamiliar territory,5,6,8 without the time required for dissemination of knowledge and the establishment of best practices.10-12

Presently, there is little data in the literature regarding how spine surgeons use telemedicine, how often they use telemedicine, when this tool seems appropriate and (perhaps more importantly) when it seems inappropriate. While preliminary studies suggest that telemedicine can be an accurate and efficient tool for spine care with high patient satisfaction,13-15 a thorough exploration of these questions is critical to safely integrating telemedicine into the spine clinical workflow.

To address the aforementioned concerns, we conducted a large-scale, global survey of spine surgeons assessing their perceptions of telemedicine across multiple domains. We sought to determine global perspectives on telemedicine and explore regional differences in surgeon attitudes and adoption.

Methods

Survey Design

The “Telemedicine & the Spine Surgeon—Perspectives and Practices Worldwide” survey was developed to assess global and regional provider use and sentiment toward telemedicine. The survey was designed through a modified Delphi approach, with 4 rounds of question review by a panel of regional research representatives, spine surgeons, and epidemiologists. 16 Questions covered the following domains: demographics, telemedicine usage, patient perceptions, trust in remote visits, telemedicine challenges and benefits, telemedicine versus in-person visits, and telemedicine in training and research (Supplemental Appendix 1).

In order to effectively highlight relevant results from the breadth of topics collected, questions from the survey were grouped into 4 categories for further analysis: (1) Global Perspectives (current manuscript); (2) Challenges and Benefits; (3) Telemedicine Evaluations; and (4) Training.

Provider Sample and Survey Distribution

The survey was distributed via email to AO Spine members between May 15 to May 31, 2020. AO Spine is the world’s largest international society of spine surgeons, consisting of over 20 000 professionals with 6,000+ surgeon members (www.aospine.org). Among the surgeon membership, 3,805 opted to receive surveys via email. All questions were optional, and missing data points were excluded from analysis. No identifying information was included in the survey. Analysis initially planned to include 6 regions: Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America. However, because only 3 surgeons from Australia responded, they were grouped together with Asia as “Asia Pacific.”

Statistical Analyses & Survey Interpretation

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Tables and graphical representation of survey responses were created using Excel version 16.37 (Microsoft Inc, Albuquerque, NM) and the open-source Python “Plotly” library, version 4.8.2 (MIT license). Descriptive statistics were used to describe overall responses. Differences in responses were compared among regions. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using chi square and ANOVA tests as appropriate. Likert scale questions were analyzed as continuous variables, with the following scale: −2 Strongly Disagree; −1 Disagree; 0 Neutral; 1 Agree; 2 Strongly Agree. Type I error rate was set at a significance of P < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

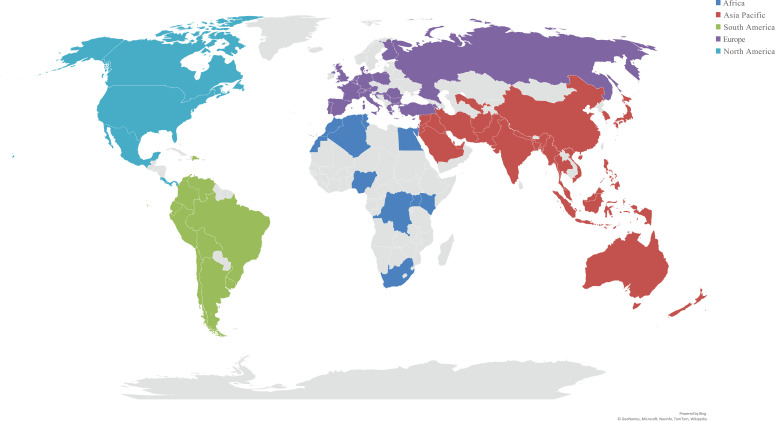

Of the 3,805 surgeons opting to receive email surveys, 485 individuals responded (12.7%) (Table 1). Responses included 75 countries and 5 regions (Figure 1). South America had the most responses (127/477; 26.6%), followed by Europe (116/477; 24.3%), Africa (95/477; 19.9%), Asia Pacific (94/477; 19.7%), and North America (45/477; 9.4%). Most respondents (446/472, 94.5%) were male, and the majority specialized in orthopedics (332/485; 68.5%). The greatest number of respondents were 35-44 years old (173/479; 36.1%), followed by 45-54 years old (160/479; 33.4%) and 55-64 years old (73/479; 15.2%). Most surgeons operated in urban communities (408/478; 85.4%) and had academic (164/482; 34.0%) or “privademic” (128/482; 26.6%) practices.

Table 1.

Survey Respondent Demographics.

| na | Percentageb | na | Percentageb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Specialty | ||||

| Male | 446 | 94.5% | Orthopedics | 332 | 68.5% |

| Female | 26 | 5.5% | Neurosurgery | 144 | 29.7% |

| Age (years) | Trauma | 50 | 10.3% | ||

| 25-34 | 56 | 11.7% | Pediatric Surgery | 16 | 3.3% |

| 35-44 | 173 | 36.1% | Other | 14 | 2.9% |

| 45-54 | 160 | 33.4% | Years Practicing | ||

| 55-64 | 73 | 15.2% | 0-5 | 100 | 20.9% |

| 65+ | 17 | 3.5% | 5-10 | 116 | 24.3% |

| Geographic Region | 11-15 | 82 | 17.2% | ||

| Africa | 95 | 19.9% | 16-20 | 68 | 14.2% |

| Asia Pacific | 94 | 19.7% | 20+ | 112 | 23.4% |

| Europe | 116 | 24.3% | Practice Breakdown (%) | ||

| North America | 45 | 9.4% | Percentage Research | ||

| South America | 127 | 26.6% | 0-25 | 356 | 74.9% |

| Estimated Population Hospital Serves | 26-50 | 100 | 21.1% | ||

| <100 000 | 46 | 9.6% | 51-75 | 13 | 2.7% |

| 100 000-500 000 | 118 | 24.7% | 76-100 | 6 | 1.3% |

| 500 000-1 000 000 | 100 | 21.0% | Percentage Clinical | ||

| 1 000 000-2 000 000 | 67 | 14.0% | 0-25 | 12 | 2.5% |

| >2 000 000 | 146 | 30.6% | 26-50 | 95 | 19.8% |

| Hospital Community | 51-75 | 191 | 39.8% | ||

| Urban | 408 | 85.4% | 76-100 | 182 | 37.9% |

| Suburban | 63 | 13.2% | Percentage Teaching | ||

| Rural | 7 | 1.5% | 0-25 | 334 | 72.5% |

| Practice Type | 26-50 | 95 | 20.6% | ||

| Academic/University Hospital | 164 | 34.0% | 51-75 | 16 | 3.5% |

| “Privademic” (Academic/Private combined) | 128 | 26.6% | 76-100 | 16 | 3.5% |

| Private Group, <10 Practitioners | 58 | 12.0% | Total Respondents | 485 | 100.0% |

| Private Group, >10 Practitioners | 20 | 4.1% | |||

| Individual Practice | 35 | 7.3% | |||

| Government/Military Hospital | 34 | 7.1% | |||

| Hospital Employee | 29 | 6.0% | |||

| Other | 14 | 2.9% | |||

a Number of respondents/votes.

b Percentages were calculated based on total responses per question, not total number of survey responses.

Figure 1.

Distribution of survey responses by geographic region.

Provider Telemedicine Usage

Before & during social distancing

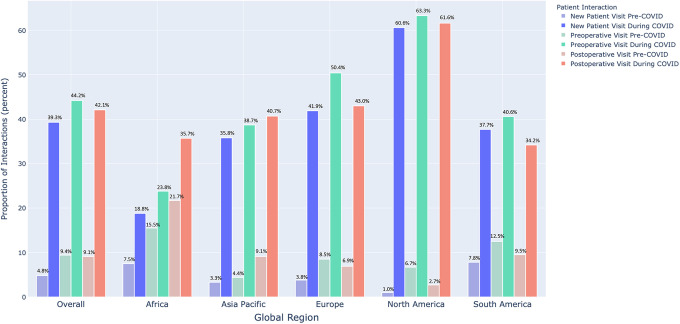

Prior to COVID-19 and social distancing, spine surgeons utilized telemedicine for <10.0% of cases (Table 2). During COVID-19 usage rose as providers performed a mean 39.3%-44.2% of all “new patient,” “follow-up,” and “postoperative” visits through telemedicine, with regional differences (new patient: P < 0.001; follow-up: P < 0.001; postoperative: P = 0.007). North America used telemedicine the most during COVID-19 at 60.6%-63.3% of visits, whereas Asia Pacific, Europe, and South America used telemedicine for 34.2%-50.4% of visits. Africa used telemedicine for 18.8%-35.7% of visits during COVID-19.

Table 2.

Provider Telemedicine Usage and Impressions.

| Overall | Africa | Asia Pacific | Europe | North America | South America | P Valueb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | ||||||||

| Before COVID-19% Telemedicine Visits of Total Practice | |||||||||||||

| % New patient | 4.8% (±12.0%) | 7.5% (±7.6%) | 3.3% (±8.9%) | 3.8% (±12.3%) | 1.0% (±2.9%) | 7.8% (±17.1%) | 0.045 | ||||||

| % Follow-up visits before surgery | 9.4% (±17.7%) | 15.5% (±14.7%) | 4.4% (±8.7%) | 8.5% (±16.3%) | 6.7% (±19.0%) | 12.5% (±22.9%) | 0.055 | ||||||

| % Postoperative visits | 9.1% (±18.5%) | 21.7% (±25.7%) | 9.1% (±18.0%) | 6.9% (±16.9%) | 2.7% (±5.6%) | 9.5% (±19.3%) | 0.002 | ||||||

| During COVID-19% Telemedicine Visits of Total Practice | |||||||||||||

| % New patient | 39.3% (±35.5%) | 18.8% (±21.5%) | 35.8% (±32.0%) | 41.9% (±36.1%) | 60.6% (±37.3%) | 37.7% (±36.2%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| % Follow-up visits before surgery | 44.2% (±35.8%) | 23.8% (±19.9%) | 38.7% (±32.8%) | 50.4% (±37.4%) | 63.3% (±36.0%) | 40.6% (±36.1%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| % Postoperative visits | 42.1% (±34.8%) | 35.7% (±23.2%) | 40.7% (±31.6%) | 43.0% (±34.9%) | 61.1% (±39.5%) | 34.2% (±35.5%) | 0.007 | ||||||

| Overall | Africa | Asia Pacific | Europe | North America | South America | ||||||||

| nc | % Total | nc | % Region | nc | % Region | nc | % Region | nc | % Region | nc | % Region | P Valueb | |

| March-May 2020 Seen Patients via Telemedicine | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 286 | 60.5% | 42 | 45.2% | 57 | 60.6% | 75 | 65.2% | 36 | 81.8% | 76 | 59.8% | |

| No, but I am a believer in telemedicine | 139 | 29.4% | 44 | 47.3% | 26 | 27.7% | 32 | 27.8% | 6 | 13.6% | 31 | 24.4% | |

| No, I do not think telemedicine gives any advantage | 48 | 10.1% | 7 | 7.5% | 11 | 11.7% | 8 | 7.0% | 2 | 4.5% | 20 | 15.7% | |

| Total Number of Telemedicine Visits Performed | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 0-10 | 57 | 24.2% | 12 | 38.7% | 21 | 42.0% | 5 | 8.1% | 1 | 3.0% | 18 | 30.0% | |

| 11-25 | 75 | 31.8% | 13 | 41.9% | 12 | 24.0% | 20 | 32.3% | 7 | 21.2% | 23 | 38.3% | |

| 20-50 | 52 | 22.0% | 5 | 16.1% | 7 | 14.0% | 14 | 22.6% | 14 | 42.4% | 12 | 20.0% | |

| 51-100 | 27 | 11.4% | 1 | 3.2% | 5 | 10.0% | 13 | 21.0% | 3 | 9.1% | 5 | 8.3% | |

| 100+ | 25 | 10.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 10.0% | 10 | 16.1% | 8 | 24.2% | 2 | 3.3% | |

| Opinion Changed After More Telemedicine Visits | 0.578 | ||||||||||||

| Better than it was | 138 | 59.0% | 15 | 48.4% | 32 | 65.3% | 32 | 51.6% | 22 | 66.7% | 37 | 62.7% | |

| Worse than it was | 13 | 5.6% | 2 | 6.5% | 2 | 4.1% | 4 | 6.5% | 3 | 9.1% | 2 | 3.4% | |

| Opinion unchanged | 83 | 35.5% | 14 | 45.2% | 15 | 30.6% | 26 | 41.9% | 8 | 24.2% | 20 | 33.9% | |

| Telemedicine Visit Requires ___ Time Than In-Person | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| More | 83 | 35.2% | 11 | 35.5% | 24 | 49.0% | 19 | 30.6% | 7 | 20.6% | 22 | 36.7% | |

| The same amount of | 77 | 32.6% | 2 | 6.5% | 12 | 24.5% | 27 | 43.5% | 10 | 29.4% | 26 | 43.3% | |

| Less | 76 | 32.2% | 18 | 58.1% | 13 | 26.5% | 16 | 25.8% | 17 | 50.0% | 12 | 20.0% | |

| How Comfortable Performing Surgery After Telemedicine | 0.151 | ||||||||||||

| Extremely comfortable | 10 | 4.6% | 1 | 3.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.8% | 5 | 16.1% | 3 | 5.7% | |

| Moderately comfortable | 56 | 25.9% | 6 | 20.0% | 13 | 28.9% | 14 | 24.6% | 7 | 22.6% | 16 | 30.2% | |

| Slightly comfortable | 70 | 32.4% | 10 | 33.3% | 14 | 31.1% | 17 | 29.8% | 9 | 29.0% | 20 | 37.7% | |

| Not at all comfortable | 80 | 37.0% | 13 | 43.3% | 18 | 40.0% | 25 | 43.9% | 10 | 32.3% | 14 | 26.4% | |

| Telemedicine Platform Used | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Secure EMR-Integrated System | 66 | 23.2% | 2 | 4.8% | 5 | 8.6% | 25 | 33.8% | 11 | 30.6% | 23 | 31.1% | |

| Secure non-EMR-Integrated System | 28 | 9.9% | 1 | 2.4% | 9 | 15.5% | 2 | 2.7% | 9 | 25.0% | 7 | 9.5% | |

| Non-secure (Facetime, Skype, etc.) | 71 | 25.0% | 13 | 31.0% | 19 | 32.8% | 8 | 10.8% | 4 | 11.1% | 27 | 36.5% | |

| Phone Call (no video) | 96 | 33.8% | 19 | 45.2% | 19 | 32.8% | 37 | 50.0% | 8 | 22.2% | 13 | 17.6% | |

| Other | 23 | 8.1% | 7 | 16.7% | 6 | 10.3% | 2 | 2.7% | 4 | 11.1% | 4 | 5.4% | |

| Telemedicine Platform Was Easy to Use | 0.002 | ||||||||||||

| Strongly Agree | 70 | 29.4% | 3 | 9.7% | 16 | 31.4% | 19 | 30.2% | 19 | 57.6% | 13 | 21.7% | |

| Agree | 125 | 52.5% | 21 | 67.7% | 25 | 49.0% | 29 | 46.0% | 13 | 39.4% | 37 | 61.7% | |

| Undecided | 33 | 13.9% | 5 | 16.1% | 4 | 7.8% | 13 | 20.6% | 1 | 3.0% | 10 | 16.7% | |

| Disagree | 9 | 3.8% | 2 | 6.5% | 5 | 9.8% | 2 | 3.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Strongly Disagree | 1 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Technical Difficulties Delay/Disrupt Visit | 0.145 | ||||||||||||

| Often (50+ %) | 13 | 5.5% | 3 | 9.7% | 5 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 9.1% | 2 | 3.3% | |

| Frequently (31-50%) | 21 | 8.9% | 2 | 6.5% | 4 | 8.0% | 6 | 9.5% | 1 | 3.0% | 8 | 13.3% | |

| Sometimes (16-30%) | 82 | 34.6% | 13 | 41.9% | 22 | 44.0% | 15 | 23.8% | 12 | 36.4% | 20 | 33.3% | |

| Rarely (1-15%) | 111 | 46.8% | 13 | 41.9% | 18 | 36.0% | 37 | 58.7% | 16 | 48.5% | 27 | 45.5% | |

| Never (0%) | 10 | 4.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.0% | 5 | 7.9% | 1 | 3.0% | 3 | 5.0% | |

| Telemedicine Imaging | 0.177 | ||||||||||||

| Same location for an in-person visit | 60 | 27.6% | 3 | 10.0% | 14 | 30.4% | 17 | 29.8% | 7 | 22.6% | 19 | 35.8% | |

| Different location | 38 | 17.5% | 7 | 23.3% | 9 | 19.6% | 10 | 17.5% | 2 | 6.5% | 10 | 18.9% | |

| The patient can choose the location | 119 | 54.8% | 20 | 66.7% | 23 | 50.0% | 30 | 52.6% | 22 | 71.0% | 24 | 45.3% | |

| Telemedicine Labs | 0.639 | ||||||||||||

| Same location for an in-person visit | 57 | 26.3% | 8 | 26.7% | 12 | 26.1% | 17 | 29.8% | 5 | 16.1% | 15 | 28.3% | |

| Different location | 42 | 19.4% | 8 | 26.7% | 7 | 15.2% | 12 | 21.1% | 4 | 12.9% | 11 | 20.8% | |

| The patient can choose the location | 118 | 54.4% | 14 | 46.7% | 27 | 58.7% | 28 | 49.1% | 22 | 71.0% | 27 | 50.9% | |

a Standard Deviation.

b Calculation of P values was performed using ANOVA and Pearson χ2 tests. Bolded values indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

c Number of respondents/votes.

Most respondents (286/473, 60.5%) had seen at least one patient via telemedicine throughout March, April, and May, with significant regional differences (P < 0.001). North America led with 36/44 (81.8%) of providers having performed at least 1 telemedicine visit, followed by Europe (75/115; 65.2%), Asia Pacific (57/94; 60.6%), South America (76/127; 59.8%), and Africa (42/93; 45.2%).

Usage sentiment

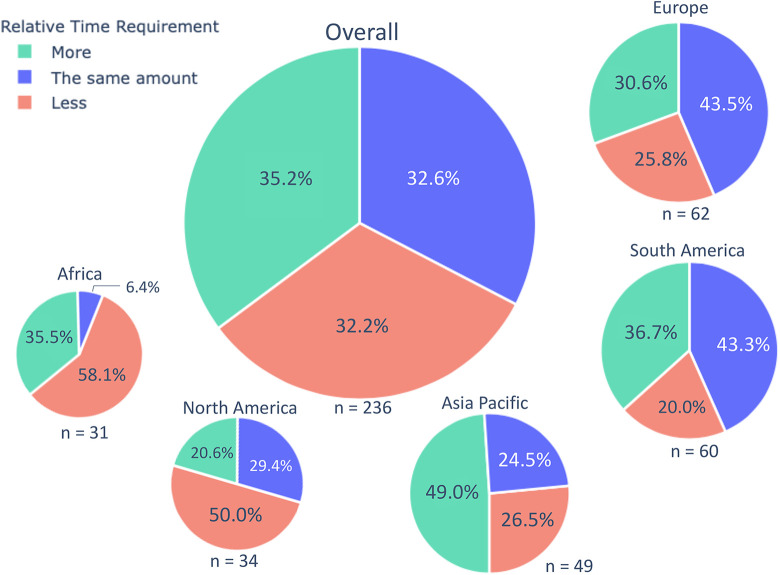

Only 48/473 (10.1%) of providers believed telemedicine did not “give any advantage” compared to in person visits. Surgeons had a more favorable impression of the technology the more they used it; 138/234 (59.0%) stated that their opinion of telemedicine was “better” after performing more visits. Only 13/234 (5.6%) believed telemedicine was “worse” after conducting more visits. There was an even split between overall sentiment about whether telemedicine required more (83/236; 35.2%), the same (77/236; 32.6%), or less (76/236; 32.2%) time than an in-person visit; however, regional responses varied (P < 0.001). Notably, age did not affect responses (P > 0.05). Most Asia Pacific respondents thought telemedicine required more time (24/49; 49.0%), while European (27/62; 43.5%) and South American (26/60; 43.3%) surgeons thought telemedicine required the same amount of time. North American (17/34; 50%) and African (18/31; 58.1%) physicians thought that telemedicine takes less time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Timing of telemedicine visits versus in-person visits. Area of pie indicates proportion of overall responses.

Surgeons (206/216; 95.4%) preferred to have at least 1 in-person visit prior to the day of surgery; 80/216 (37.0%) responded they were “not at all comfortable” performing surgery after a telemedicine encounter and did not indicate patients for surgery over telemedicine.

Telemedicine platform

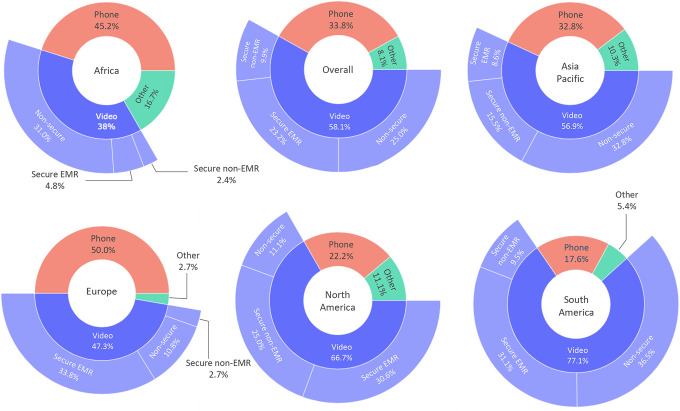

Overall, phone calls without video were the most common form of telemedicine (96/284; 33.8%), followed by non-secure videoconferencing programs (Facetime, Skype, etc.) (71/284; 25%), secure EMR-integrated systems (66/284; 23.2%), secure non-EMR-integrated systems (28/284; 9.9%), and other (23/284; 8.1%). Responses to “other” included: “Doximity,” “Microsoft Teams,” “WhatsApp,” “Amwell,” “Clickdoc,” “WeChat,” and “E-mail.” Regional differences were observed in the type of platform (P < 0.001). European (37/74; 50.0%) and African (19/42; 45.2%) surgeons were more likely to conduct phone calls whereas North American (24/36; 66.7%) and South American (57/74; 77.0%) surgeons were more likely to use video visits (EMR-Integrated or non-secure platforms, excluding “other”).

Most respondents (195/238; 81.9%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that their telemedicine platform was easy to use; however, regional responses varied (P = 0.002). North Americans (32/33; 97%), South Americans (50/60; 83.4%), Asia Pacific (41/51; 80.4%), Africans (24/31; 77.4%), and Europeans (48/63; 76.2%) agreed or strongly agreed telemedicine was easy to use. 14.3% (34/237) of the surgeons experienced technical difficulties for more than 30% of visits.

Patient Demographics

Responses about perceived patient demographics were mostly neutral (Table 3); providers did not feel strongly that patients using telemedicine had more income (mean: 0.05; SD: ±1.08), were more likely to be minorities (mean: 0.01; SD: ±0.86) or were impacted by demographic factors (mean: −0.06; SD: ±0.96). Respondents tended to agree that older patients have more difficulty using telemedicine platforms (mean: 0.44; SD: ±1.07). The only significant regional difference was in perceived level of education for patients using telemedicine (P = 0.034). Africa (mean: 0.52; SD: ±0.93), Asia Pacific (mean: 0.35; SD: ±0.95), and South America (mean: 0.36; SD: ±0.91) trended toward agreement that patients using telemedicine had more education, while North America (mean: 0.03; SD: ±1.05) and Europe (mean: −0.03; SD: ±0.97) responded neutrally.

Table 3.

Provider Perceptions of Telemedicine Patient Age, Income, Education, and Demographics.

| Overall | Africa | Asia Pacific | Europe | North America | South America | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | P Valueb | |

| Provider Perceptions on Patients | |||||||

| (-2 Strongly Disagree, −1 Disagree, 0 Neutral, 1 Agree, 2 Strongly Agree) | |||||||

| Patients via telemedicine are younger | -0.17 (±0.97) | 0.03 (±0.75) | -0.18 (±0.99) | -0.18 (±1.01) | -0.41 (±1.08) | -0.12 (±0.93) | 0.454 |

| Older patients have difficulty with telemedicine | 0.44 (±1.07) | 0.35 (±0.91) | 0.61 (±1.10) | 0.28 (±1.08) | 0.12 (±1.25) | 0.69 (±0.95) | 0.054 |

| Telemedicine options not available lower income | 0.05 (±1.08) | 0.39 (±0.99) | 0.06 (±1.18) | -0.13 (±1.10) | -0.18 (±1.07) | 0.19 (±1.00) | 0.126 |

| Patients via telemedicine tend to have more education | 0.23 (±0.97) | 0.52 (±0.93) | 0.35 (±0.95) | -0.03 (±0.97) | 0.03 (±1.05) | 0.36 (±0.91) | 0.034 |

| Patients via telemedicine less likely to be minorities | 0.01 (±0.86) | 0.23 (±0.97) | 0.00 (±0.83) | 0.02 (±0.88) | -0.13 (±0.89) | -0.06 (±0.93) | 0.364 |

| Telemedicine not impacted by demographic factors | -0.06 (±0.96) | -0.17 (±0.79) | 0.02 (±1.09) | 0.03 (±0.89) | -0.06 (±0.97) | -0.19 (±0.99) | 0.682 |

a Standard Deviation.

b Calculation of P values was performed using ANOVA tests. Bolded values indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

Personal Trust

Providers believed that patients should be seen in person at least once before scheduling surgery (mean: 1.37; SD: ±0.94) and postoperatively (mean: 1.11; SD: ±0.91) (Table 4). Respondents agreed that imaging review can be done over telemedicine (mean: 0.95; SD: ±0.99) and on average slightly agreed that the initial appointment (mean: 0.35; SD: ±1.20) and postoperative care (mean: 0.42; SD: ±1.00) can be done through telemedicine. There were no significant differences between regional responses (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Provider Trust in Telemedicine.

| Overall | Africa | Asia Pacific | Europe | North America | South America | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | P Valueb | |

| If You or a Family Member Were a Patient | |||||||

| (-2 Strongly Disagree, −1 Disagree, 0 Neutral, 1 Agree, 2 Strongly Agree) | |||||||

| The initial appointment can be done through telemedicine | 0.35 (±1.20) | 0.03 (±1.08) | 0.53 (±1.12) | 0.10 (±1.22) | 0.62 (±1.37) | 0.47 (±1.13) | 0.077 |

| Imaging review can be done over telemedicine | 0.95 (±0.99) | 0.71 (±0.94) | 0.94 (±1.00) | 0.94 (±0.97) | 1.21 (±1.07) | 0.95 (±0.98) | 0.392 |

| Postoperative care can be done through telemedicine | 0.42 (±1.00) | 0.29 (±1.04) | 0.40 (±1.03) | 0.43 (±0.94) | 0.79 (±1.05) | 0.30 (±0.98) | 0.210 |

| Patients should be seen at least once in person before surgery | 1.37 (±0.94) | 1.32 (±1.22) | 1.58 (±0.61) | 1.47 (±0.95) | 1.12 (±1.04) | 1.27 (±0.90) | 0.171 |

| Patients should be seen at least once in person postoperatively | 1.11 (±0.91) | 1.03 (±1.11) | 1.25 (±0.73) | 1.16 (±0.83) | 0.85 (±1.12) | 1.13 (±0.87) | 0.366 |

a Standard Deviation.

b Calculation of P values was performed using ANOVA tests. Bolded values indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first global survey to assess spine surgeon perceptions of telemedicine. We found that telemedicine usage rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic with significant regional variation in the type of platform utilized and attitudes toward telemedicine. These results provide an important snapshot of the current state of telemedicine in spine surgery and offer important areas for future investigation.

Global Usage & Perspectives

Globally, the use of telemedicine has soared across all specialties in response to the COVID-19 crisis.1,17,18 Our results are consistent with this trend: spine surgeon usage of telemedicine rose from less than 10.0% of all visits pre-COVID-19 to greater than 39.0% of all visits during the pandemic. This data is largely consistent with a previous study showing that 35.6% of spine surgeons worldwide were using telemedicine for over half of all visits in March 2020. 9

The speed with which this technology has been adopted is largely unprecedented. That said, our results indicate a largely positive outlook regarding telemedicine in spine surgery. A significant majority of surgeons (81.9%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that telemedicine was easy to use. Additionally, the value of telemedicine seemed to become more apparent after increased use; 59.0% of surgeons stated their opinion of telemedicine changed for the better after more experience. This combination — an easy to use platform that is more positively perceived with increased use — might suggest increased adoption over time. Notably, we found no significant differences in usage sentiment between age groups in our analysis. One may expect older physicians to be less comfortable adapting to telemedicine, though we found no evidence of this.

Of course, there were growing pains as well; 14.3% of respondents experienced technical difficulties on >30% of visits and another 34.6% experienced technical difficulties on 16-30% of visits. As surgeons and patients become more familiar with the technology and as telemedicine platforms mature, we expect the number of technical difficulties to decrease.

Previous studies have shown that telemedicine visits can be as effective as in-person consults for treating chronic conditions, making diagnoses, and even referring for surgery.19-21 To that end, surgeons in our study tended to agree that new patient visits, imaging review, and postoperative care could be performed by telemedicine. However, a plurality (37.0%) of providers did not feel comfortable offering surgery to patients based on telemedicine alone. Additionally, surgeons strongly agreed that patients must be seen at least once in person before and after surgery.

These findings reflect an uncertainty of how telemedicine fits into established practice patterns. Factors behind this conflict are numerous and include: technical difficulties, increased medicolegal exposure, inability to perform a physical exam, and weaker doctor-patient relationships. 8 While our survey touches on many of these factors, given the breadth and depth of these topics, we plan to explore them in more detail in future manuscripts. On the whole, our data suggests that telemedicine has an important role in care delivery and that surgeons are receptive to its use. This is consistent with early research supporting the efficacy and accuracy of telemedicine surgery decision making.13,14 More recently, preliminary guides have emerged to help standardize spine telemedicine care.22-24 However, significant work is needed to define the applications and limitations of this new tool.

Regional Variation (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Telemedicine usage before and during COVID-19.

The global reach of this survey is a unique feature and allows us to explore regional differences in the rates of telemedicine adoption, attitudes toward telemedicine, and types of platforms utilized in each region.

For instance, surgeons in Africa (21.7% of postoperative visits) and South America (12.4% of follow-up visits) reported higher telemedicine usage even before COVID-19 (global average was <10%). These differences could be driven by the increased access to care telemedicine provides, especially in regions with less population/medical care density.8,25,26 Other factors such as reimbursement parity might also have outsized impacts on telemedicine adoption.1,8 Indeed, adoption grew most rapidly in North America during the pandemic from a pre-COVID average of <7.0% to >60.0% of visits; importantly, most payors relaxed reimbursement rules during this time.27,28 The impact of these types of factors (i.e., potential barriers to telemedicine adoption) will be more fully explored in a future manuscript.

Another important contributor to regional differences was the different telemedicine platforms available. In Africa and Europe, respondents were much more likely to describe telephone calls as their telemedicine platform, whereas in North and South America, video visits constituted the main form of telemedicine (Figure 4). These differences highlight the lack of regulatory clarity surrounding telemedicine.8,27 Moreover, the very definition of telemedicine is a source of confusion, with over 100 peer-reviewed definitions existing throughout the literature. 29

Figure 4.

Main telemedicine platform used.

The difference between an all-audio and an audiovisual appointment may have important consequences: for instance, although not significant, we found the African and European surgeons were least likely to agree that the initial appointment could be performed over telemedicine (P = 0.077); whereas North and South American surgeons were most likely to agree (Table 4). We plan to further explore the impact of telemedicine platform on surgeon perceptions and their ability to perform physical examinations as part of future manuscripts. Even our initial findings, however, emphasize the importance of standardizing techniques, best practices, and technology to ensure clarity for future adoption.

Strengths and Limitations

As with any clinical study, our study has limitations. The percentage of total respondents was only 12.7% of AO Spine members who opted to receive surveys by email; however, this is consistent with previous response rates for other spine surveys.9,30 Additionally, because each question was optional, not every response had an answer, and survey fatigue may have lowered the response rate for latter questions. There is also an inherent selection bias in surgeons who chose to take the survey: it is likely that those with an interest in telehealth were more likely to respond. This might lead to an overestimation of telemedicine usage in the wider spine surgeon population.

Despite these limitations, we believe our survey offers a unique perspective on a new tool in spine surgery. We provide the results of a large (485 surgeons), global cross section of spine surgeons. This represents the largest international survey of spine surgeons to address telemedicine and highlights several important themes that might help speed adoption and clarify best practices.

Conclusion

Telemedicine usage has risen steeply during the COVID-19 crisis, from <10% to approximately 40% of all visits occurring over telemedicine. Spine surgeons approved of telemedicine, provided at least one in-person visit occurs pre- and post-operation. Standardization of telemedicine procedures and technology may help bridge the regional gap between video and non-video consultations and streamline telemedicine as a viable alternative to certain traditional visits. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess worldwide perspectives and regional variation in spine surgeon telemedicine usage and sentiment. Based on this foundation, future studies will analyze the challenges, benefits, efficacy, and training data collected to address targeted questions. In addition, we plan to distribute a follow-up survey to determine sustainability and the future of telemedicine use once the pandemic subsides.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-gsj-10.1177_21925682211022311 for Telemedicine in Spine Surgery: Global Perspectives and Practices by Grant Riew, Francis Lovecchio, Dino Samartzis, Philip K. Louie, Niccole Germscheid, Howard An, Jason Pui Yin Cheung, Norman Chutkan, Gary Michael Mallow, Marko H. Neva, Frank M. Phillips, Daniel Sciubba, Mohammad El-Sharkawi, Marcelo Valacco, Michael H. McCarthy, Melvin Makhni and Sravisht Iyer in Global Spine Journal

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to Kaija Kurki-Suonio and Fernando Kijel from AO Spine (Davos, Switzerland) for their assistance with circulating the survey to AO Spine members.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Grant J. Riew, AB  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8035-7357

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8035-7357

Francis Lovecchio, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5236-1420

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5236-1420

Dino Samartzis, DSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7473-1311

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7473-1311

Philip K. Louie, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4787-1538

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4787-1538

Jason Pui Yin Cheung, MBBS, MS, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7052-0875

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7052-0875

Daniel Sciubba, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7604-434X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7604-434X

Mohammad El-Sharkawi, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6177-7145

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6177-7145

Michael H. McCarthy, MD, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-6366

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-6366

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679–1681. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2003539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig J, Petterson V. Introduction to the practice of telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;11(1):3–9. doi:10.1177/1357633X0501100102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker J, Stanley A. Telemedicine technology: a review of services, equipment, and other aspects. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18(11):60. doi:10.1007/s11882-018-0814-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tachakra S, Wang XH, Istepanian RSH, Song YH. Mobile e-health: the unwired evolution of telemedicine. Telemed J E Health. 2003;9(3):247–257. doi:10.1089/153056203322502632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loeb AE, Rao SS, Ficke JR, Morris CD, Riley LH, Levin AS. Departmental experience and lessons learned with accelerated introduction of telemedicine during the covid-19 crisis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(11):e469–e476. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka MJ, Oh LS, Martin SD, Berkson EM. Telemedicine in the era of COVID-19: the virtual orthopaedic examination. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(12):e57. doi:10.2106/JBJS.20.00609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnally CJ, Vaccaro AR, Schroeder GD, Divi SN. Is evaluation with telemedicine sufficient before spine surgery? Clin Spine Surg. 2020. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000001027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makhni M, Riew G, Sumathipala M. Telemedicine in orthopaedic surgery: challenges and opportunities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(13):1109–1115. doi:10.2106/jbjs.20.00452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louie PK, Harada GK, McCarthy MH, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on spine surgeons worldwide. Global Spine J. 2020;10(5):534–552. doi:10.1177/2192568220925783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan KA, Thadani VN, Chan D, Oh JYL, Liu GKP. Addressing coronavirus disease 2019 in spine surgery: a rapid national consensus using the Delphi method via teleconference. Asian Spine J. 2020;14(3):373–381. doi:10.31616/asj.2020.0224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco D, Montenegro T, Gonzalez GA, et al. Telemedicine for the spine surgeon in the age of COVID-19: multicenter experiences of feasibility and implementation strategies. Global Spine J. 2021;11(4):608–613. doi:10.1177/2192568220932168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Helou A. Spine surgery in Atlantic Canada in the COVID-19 era: lessons learned so far. Spine J. 2020;20(9):1379–1380. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2020.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lightsey HM, Crawford AM, Xiong GX, Schoenfeld AJ, Simpson AK. Surgical plans generated from telemedicine visits are rarely changed after in-person evaluation in spine patients. Spine J. 2021;21(3):359–365. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2020.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford AM, Lightsey HM, Xiong GX, Striano BM, Schoenfeld AJ, Simpson AK. Telemedicine visits generate accurate surgical plans across orthopaedic subspecialties. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021:1–8. doi:10.1007/s00402-021-03903-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shafi K, Lovecchio F, Forston K, et al. The Efficacy of telehealth for the treatment of spinal disorders: patient-reported experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. HSS J. 2020;16(Suppl 1):1–7. doi:10.1007/s11420-020-09808-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. In Manag. 2004;42(1):15–29. doi:10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohannessian R, Duong TA, Odone A. Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18810. doi:10.2196/18810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lezak BA, Cole PA, Schroder LK, Cole PA. Global experience of orthopaedic trauma surgeons facing COVID-19: a survey highlighting the global orthopaedic response. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1519–1529. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04644-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buvik A, Bugge E, Knutsen G, Småbrekke A, Wilsgaard T. Quality of care for remote orthopaedic consultations using telemedicine: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):483. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1717-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertani A, Launay F, Candoni P, Mathieu L, Rongieras F, Chauvin F. Teleconsultation in paediatric orthopaedics in Djibouti: evaluation of response performance. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(7):803–807. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2012.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haukipuro K, Ohinmaa A, Winblad I, Linden T, Vuolio S. The feasibility of telemedicine for orthopaedic outpatient clinics—a randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2000;6(4):193–198. doi:10.1258/1357633001935347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahezi SE, Duarte RA, Yerra S, et al. Telemedicine during COVID-19 and beyond: a practical guide and best practices multidisciplinary approach for the orthopedic and neurologic pain physical examination. Pain Physician. 2020;23(4 S):S205–S238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haldeman S, Nordin M, Tavares P, et al. Distance management of spinal disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: evidence-based patient and clinician guides from the global spine care initiative. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(2):e25484. doi:10.2196/25484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer S, Shafi K, Lovecchio F, et al. The Spine physical examination using telemedicine: strategies and best practices. Global Spine J. 2020:2192568220944129. doi:10.1177/2192568220944129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Combi C, Pozzani G, Pozzi G. Telemedicine for developing countries. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(4):1025–1050. doi:10.4338/ACI-2016-06-R-0089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodridge D, Marciniuk D. Rural and remote care: overcoming the challenges of distance. Chron Respir Dis. 2016;13(2):192–203. doi:10.1177/1479972316633414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MEDICARE TELEMEDICINE HEALTH CARE PROVIDER FACT SHEET | CMS. Accessed April 18, 2020. Published Mar 17, 2020 https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet

- 28.Lacktman NM, Acosta JN, Levine SJ. 50-State Survey of Telehealth Commercial Payer Statutes. Published by Foley: https://www.foley.com/-/media/files/insights/health-care-law-today/19mc21487-50state-survey-of-telehealth-commercial.pdf 150.

- 29.Sood S, Mbarika V, Jugoo S, et al. What is telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(5):573–590. doi:10.1089/tmj.2006.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Härtl R, Lam KS, Wang J, Korge A, Kandziora F, Audigé L. Worldwide survey on the use of navigation in spine surgery. World Neurosurg. 2013;79(1):162–172. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-gsj-10.1177_21925682211022311 for Telemedicine in Spine Surgery: Global Perspectives and Practices by Grant Riew, Francis Lovecchio, Dino Samartzis, Philip K. Louie, Niccole Germscheid, Howard An, Jason Pui Yin Cheung, Norman Chutkan, Gary Michael Mallow, Marko H. Neva, Frank M. Phillips, Daniel Sciubba, Mohammad El-Sharkawi, Marcelo Valacco, Michael H. McCarthy, Melvin Makhni and Sravisht Iyer in Global Spine Journal