Abstract

Several factors are thought to limit the efficiency of retroviral transduction in clinical gene therapy protocols that target hematopoietic stem cells. For example, the level of expression of the amphotropic receptor Pit-2, a phosphate symporter, appears to be low in human and murine hematopoietic stem cells. We have previously demonstrated that transduction of hematopoietic cells in the presence of the fibronectin (FN) fragment CH-296 is extremely efficient (H. Hanenberg, X. L. Xiao, D. Dilloo, K. Hashino, I. Kato, and D. A. Williams, Nat. Med. 2:876–882, 1996). To examine functionally whether the retrovirus receptor is a limiting factor in transduction of hematopoietic cells, we performed competition experiments in the presence of FN CH-296 with retrovirus vectors pseudotyped with the same or a different envelope protein. We demonstrate in both human erythroleukemia (HEL) cells and primary human CD34+ hematopoietic cells inhibition of efficient infection due to receptor interference when two vectors targeting the amphotropic receptor are used simultaneously. Receptor interference lasted up to 24 h. No interference was demonstrated when vectors targeting the amphotropic receptor and the gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV) receptor Pit-1 were used concurrently. In contrast, simultaneous infection with vectors targeting both Pit-1 and Pit-2 yielded transduction efficiencies consistently higher than with either vector alone in both HEL cells and human CD34+ hematopoietic cells. These data demonstrate that the use of FN CH-296 leads to amphotropic receptor saturation in these cells. Simultaneous infection with vectors targeting both amphotropic and GALV receptors may prove to be of additional benefit in the design of gene therapy protocols.

In many mammalian cells, efficient introduction of genetic material can be accomplished with recombinant retroviral vectors. Retrovirus vectors have also been used as vehicles for gene therapy studies, since many therapeutic applications require integration of genes into cellular DNA (15, 35). Important potential targets for gene modification are hematopoietic stem cells that have the ability to establish long-lived and multilineage reconstitution of hematopoiesis in mammals (23, 40). Despite advantages of both retroviral vectors and hematopoietic stem cells as tools for genetic therapy, retroviral gene transfer into primitive stem cells of large animals via retrovirus vectors has been problematic, and the potential therapeutic use of gene transfer technology in human diseases remains largely unfulfilled (30).

Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer into human hematopoietic stem cells is influenced by multiple factors, including low viral titer (12, 25, 44) and the cycle status of the target stem cells (36). Recently, increasing attention has been focused on the level of expression of viral receptors in these primitive cells. Two different retroviral receptors have been extensively used for targeting cells of the human hematopoietic system: the amphotropic murine leukemia virus (MLV) receptor and the gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV) receptor (31). Both receptors have been characterized as sodium-dependent phosphate symporters (5, 45). Significant sequence similarity exists between the amphotropic receptor and the GALV receptor, although these receptors bind virion particles without cross-interference (37). The level of expression of the amphotropic receptor, Pit-2, has been measured by mRNA levels and appears to be low in human and primate CD34+ hematopoietic cells (21, 43, 51) and in murine hematopoietic stem cells (42). This has led to speculation that a low level of expression of the receptor protein is responsible, at least in part, for low-level transduction with amphotropic-packaged vectors (21, 42, 49). In contrast, the mRNA level of the GALV receptor, Pit-1, appears to be higher than that of the amphotropic receptor in CD34+ cells isolated from nonhuman primates (21). Thus the levels of mRNA of these two receptors appear to correlate with the respective levels of infection in different cells by recombinant retroviral vectors (21, 49). Kiem et al. (22) have exploited this difference to improve transduction of primate hematopoietic stem cells with GALV-pseudotyped vectors.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the capacity of retroviruses to bind their cognate receptor is sensitive to a variety of manipulations. During infection with replication-competent retrovirus, receptor occupancy by envelope protein interferes with subsequent reinfection of cells, a process termed superinfection interference (48). Transduction with replication-defective viruses, which lack envelope protein coding sequences, has rarely been reported to be associated with receptor interference (28). However, receptor interference may be particularly important with respect to the functional consequences of low receptor density in hematopoietic cells, a major target population for gene therapy applications. Since viral occupancy of the cognate receptor is a critical component of efficient infection, our laboratory has exploited colocalization of viral particles and target cells via interaction with fragments of the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin (FN) to increase transduction of a variety of mammalian cells, including hematopoietic cells (17, 39, 46). In a recent study, we noted that continuous exposure of human hematopoietic cells to virus in the presence of the peptide fragment FN CH-296 prior to induction of cell cycling led to a transduction efficiency significantly inferior to that when the cells were stimulated with cytokines prior to virus exposure (16). Since current clinical protocols frequently utilize multiple infections targeting the same receptor, the possibility that receptor expression or receptor interference may play a role in inefficient transduction of hematopoietic cells, particularly in the presence of fibronectin, could be critical to gene therapy protocols.

In the study reported here, hematopoietic cell lines and primary human CD34+ hematopoietic cells were infected on FN CH-296 simultaneously with distinguishable retroviral vectors pseudotyped with either the same or different envelope proteins. Simultaneous infection with two viruses pseudotyped with the same envelope protein was associated with inhibition of transduction both in human erythroleukemia (HEL) cells and in human CD34+ primary hematopoietic cells. This inhibition was attributable to receptor interference, since no inhibition could be demonstrated during simultaneous infection by two vectors utilizing different receptors for cell entry. Receptor interference continued for up to 24 h after the initial exposure to virus. In contrast, simultaneous infection with MLV amphotropic and GALV-pseudotyped vectors yielded transduction efficiencies consistently higher than in infection with either vector alone in both target cells. These studies demonstrate that, in the presence of FN CH-296, functional receptor density limits transduction of hematopoietic cells and sequential infection of these cells within a short period of time provides little additional quantitative transduction benefit. Finally, simultaneous infection with vectors targeting different receptors may prove to be an additional approach for further improving transduction of hematopoietic targets for gene therapy protocols.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary cells and cell lines.

Bone marrow CD34+ cells were obtained from healthy adult volunteers after informed consent according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Indiana University School of Medicine. Bone marrow CD34+ cells were purified with a MACS column according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Bitec, Auburn, Calif.). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from apheresis products collected following 4 days of treatment with 10 μg of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (Neupogen; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, Calif.) per kg of body weight per day. Peripheral blood CD34+ cells were isolated in an Isolex 300i column (Baxter Immunotherapy, Irvine, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purity of the cells was determined by staining 106 cells with 10 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled mouse anti-human CD34 antibody (BIRMA-K3; Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, Calif.). CD34+ cells were resuspended in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone, Logan, Utah), 1% (vol/vol) penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco BRL), and 1% (vol/vol) l-glutamine (PSG) (Gibco BRL). HEL cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were grown in RPMI (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 15% FCS and 1% PSG. HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% calf serum (Summit Biotech, Ft. Collins, Colo.).

Retroviral vectors.

Two retroviral vectors were used to generate virus stocks packaged in three different packaging cell lines. The LNC-mB7.1 vector has been described previously (16) and expresses the murine B7.1 cDNA from an internal cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (Fig. 1). This LNC vector also expresses the neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) gene for selection of infected cells in G418. LNC-mB7.1 was packaged in the PA317 (aLNC-mB7.1) (32) and pg13 (pgLNC-mB7.1) (34) packaging cell lines, generating both amphotropic and GALV viral stocks. The MFG-EGFP vector has been described previously (2) and expresses enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP), isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria, from the Moloney murine leukemia virus (MFG) long terminal repeat (LTR) (Fig. 1). MFG-EGFP was packaged into the GP+envAM12 packaging cell line (29), generating an amphotropic virus stock (aMFG-EGFP). Virus-producing cell lines were cultured in high-glucose DMEM, 10% FCS, 1% PSG, and 1% (vol/vol) minimal essential medium (MEM) sodium pyruvate (Gibco BRL). Retrovirus supernatants were collected at 32°C within 24 h of addition of fresh IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS and 1% PSG to confluent cells, filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and stored immediately at −80°C. Supernatants were collected from the following lines: GP+envAM12 packaging cells, aMFG-EGFP, PA317 packaging cells, aLNC-B7.1, pg13 packaging cells, and pgLNC-B7.1. In addition some supernatants were harvested from the above lines after treatment with the glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin C (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). A 0.15-μg/ml solution was prepared and stored according to Heifetz et al. (19). Treatment of cells with tunicamycin C inhibits their ability to glycosylate proteins and thus diminishes their ability to express retrovirus envelope proteins. All cell lines were mycoplasma free.

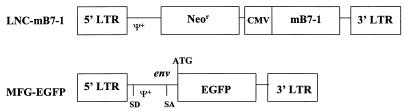

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of retroviral constructs. LNC-mB7.1 contains the neomycin phosphotransferase gene under control of the MLV 5′ LTR. The mB7.1 cDNA is under control of an internal CMV promoter. In MFG-EGFP, EGFP is expressed off of the MLV 5′ LTR via a spliced message. Neor, Neo phosphotransferase; mB7-1, murine B7.1 cDNA; SD, splice donor; SA, splice acceptor; env, envelope sequence denoting position of the envelope ATG.

The relative infection efficiency of the harvested virus stocks was determined by flow cytometry. Briefly, 5,000 HeLa cells/well were plated in six-well tissue culture plates (Corning Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) and incubated overnight. The following day, dilutions of virus stock ranging from undiluted to 1:10 were placed on the cells in the presence of 7.5 μg of polybrene (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, Wis.) per ml. The virus was diluted with fresh medium after a 4-h infection. After 6 days, cells were harvested from their wells and analyzed by flow cytometry. Transduction efficiency was subsequently compared by using the highest dilutions that showed positive HeLa cells by flow cytometry.

Infection and analysis of transduced cells.

CD34+ cells were prestimulated for 48 h in a solution of 100 units of G-CSF per ml, 100 ng of stem cell factor per ml, and 100 ng of megakaryocyte growth and development factor per ml (all from Amgen) in IMDM containing 10% FCS and PSG. All transductions were carried out in 24-well non-tissue culture treated plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) coated with recombinant FN CH-296 (RetroNectin; Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan), as previously described (17). To examine potential receptor saturation and interference, infections were carried out by using aMFG-EGFP with or without simultaneous exposure of cells to aLNC-mB7.1 or pgLNC-mB7.1. The ratio of mB7.1 virus to aMFG-EGFP virus ranged from 1:100 to 1:1, with all infections carried out in a total volume of 2 ml. To examine the duration of receptor interference, additional experiments were done in which cells were first infected for 4 h with aMFG-EGFP on FN CH-296 and then infected a second time at increasing time intervals (0 to 40 h later) with either aLNCmB7.1 or pgLNCmB7.1. Controls cells plated on FN CH-296 were exposed only to the second virus.

Infected cells were cultured for 2 to 6 days and then harvested for analysis. Cells were collected from FN CH-296-coated plates by thorough pipetting with medium and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells infected with LNC-mB7.1 were resuspended in 0.1 μg of phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse CD80 (B7.1) (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) per 100 μl of PBS–0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After staining, the cells were washed once in PBS, resuspended in PBS-BSA, and analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson). For expression of B7.1 and EGFP, gates were established with noninfected cells which had been stained with anti-mB7.1 antibody.

ELISA.

The envelope protein production of various cell lines was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Microtest III 96-well flexible polyvinyl chloride assay plates (Becton Dickinson) were loaded with FN CH-296 at a concentration of 1 μg/well in 100 μl of PBS for 2 to 4 h at room temperature. Plates were then blocked with 2% (wt/vol) BSA-PBS solution to completely fill the wells for 30 min. Wells were washed three times with PBS–0.1% (wt/vol) BSA–0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (washing buffer) (Sigma). Virus supernatant (100 μl) was loaded three consecutive times to the wells, and, each time, plates were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Wells were washed three times with washing buffer and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with a monoclonal antibody (83A25) which recognizes amphotropic envelope glycoprotein gp70 (14, 20). Plates were washed again and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with rat anti-goat immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.) diluted in PBS-Tween. The wells were washed and incubated with 100 μl of peroxidase substrate solution for 15 min at room temperature (1-Step Turbo ELISA; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). To stop the reaction, 100 μl of 1 mol of H2SO4 (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Ill.) per liter was added and the plates were read at 450 nm with a Thermomax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, Calif.).

Statistical analysis.

Differences between groups were compared by the Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P of <0.05.

RESULTS

Inhibition of infection is evident when cells are infected with two viruses of the same envelope pseudotype on FN CH-296.

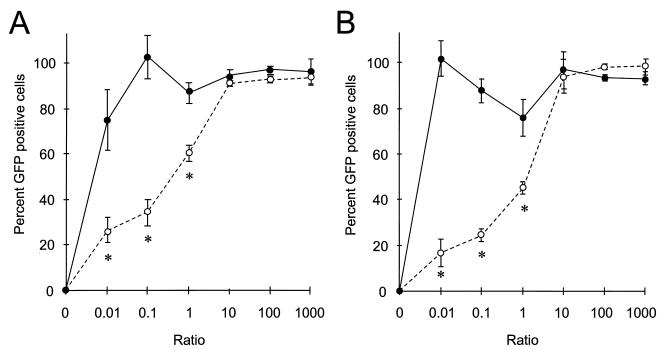

To determine whether receptor occupancy is a limiting factor for repeated infections with amphotropic viruses, HEL cells were infected simultaneously on FN CH-296 with two viruses which target the same amphotropic receptor: aMFG-EGFP and aLNC-B7.1 (Fig. 1). The efficiency of transduction of HEL cells with the reporter virus, aMFG-EGFP, was then compared to the transduction efficiency in the presence of pgLNC-B7.1, which targets the GALV receptor. As shown in Fig. 2A, the percentage of EGFP-positive cells is significantly reduced by simultaneous exposure to aLNC-B7.1 of equal volume and in a dilution-dependent fashion until the reporter virus, aMFG-EGFP, is present at a 10-fold-higher concentration than the second virus. In contrast, a second virus packaged in a different pseudotype did not significantly affect transduction even at a 100-fold-higher concentration. Since no inhibition of transduction was noted with virus targeting a second retroviral receptor, these data strongly imply that there is interference at the level of receptor binding in these experiments. The experiment was repeated with human CD34+ hematopoietic cells isolated from bone marrow from healthy volunteers. As seen in Fig. 2B, nearly identical results were obtained with human bone marrow CD34+ cells, including an apparent interference in transduction until the reporter virus of the same envelope pseudotype was present at a 10-fold excess. Similar data were seen when human G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells were used as target cells for retroviral infection (data not shown). These data demonstrate that receptor density or function is a limiting factor for genetic transduction of hematopoietic cells on FN CH-296.

FIG. 2.

Transduction of target cells infected simultaneously with two retroviruses. HEL (A) and CD34+ (B) cells were infected with 2-ml supernatants containing two retroviruses pseudotyped with the same (open symbols) or different (closed symbols) envelope proteins and mixed at ratios shown along the ordinate. The efficiency of infection of aMFG-EGFP is read as percent EGFP-positive cells when aMFG-EGFP is the only virus used. Values are means ± standard errors of the means for three independent experiments. ∗, P < 0.05.

Infection with two different pseudotypes increases total transduction.

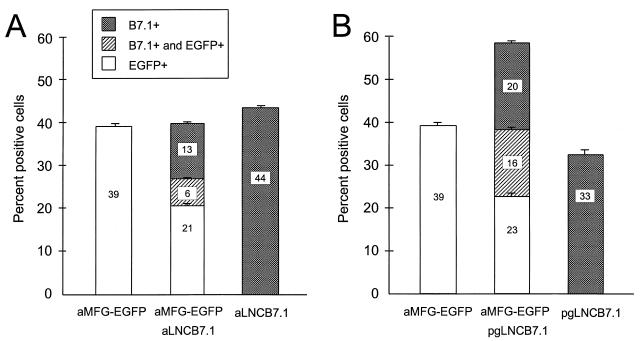

Next, we analyzed whether targeting of cells with two differently pseudotyped vectors could be utilized to increase the total number of transduced cells. As implied above, the total number of transduced HEL cells (measured as EGFP-positive plus mB7.1-positive cells and expressed as percent positive cells) produced with equal volumes of undiluted aMFG-EGFP and aLNC-mB7.1 supernatant is approximately equal to that of either virus used separately (Fig. 3A). However, the percentage of cells which demonstrated transduction by each virus is proportionally less. Although there is a small number of cells transduced with both viruses, the reduction in transduction by each virus is greater than the increase obtained by double transduction. For instance, aMFG-EGFP transduction falls from 39 to 27% (21% + 6%) in the presence of the second virus, while infection of aLNC-mB7.1 falls from 44 to 19% (13% + 6%). In contrast, the total percentage of cells infected when two viruses which target different receptors (aMFG-EGFP and pgLNC-mB7.1) are used is significantly greater than with either virus by itself (Fig. 3B). Thus, transduction of HEL cells reaches nearly 60% with both amphotropic and GALV-pseudotyped vectors compared to <40% with either vector alone. As shown in Fig. 3B, the population of cells transduced by amphotropic or GALV-pseudotyped virus alone is similar to that with concurrent infection with both pseudotypes. For instance, transduction was 39% with aMFG-EGFP alone and 33% with pgLNC-B7.1 alone versus 39% (23% + 16%) and 36% (20% + 16%) in the presence of a second virus of a different pseudotype, respectively. However, a large percentage of cells are transduced simultaneously by both vectors and express B7.1 and EGFP (16%). Thus, when two viruses of the same pseudotype are used, the infection efficiency of both is compromised, while, if two viruses target different receptors, both viruses exhibit their maximum infection efficiency. This result was found in three of three independent experiments with HEL cells (Table 1). Infection of human G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood or bone marrow CD34+ or CD34+/CD38− cells demonstrated a similar increase in transduction efficiency with simultaneous infection by two viruses targeting different receptors (Table 1). In two of three independent experiments, total transduction of CD34+ cells increased by 120 to 145%. A similar increase was demonstrated in the more primitive CD34+/CD38− cell population in two experiments.

FIG. 3.

Total transduction of HEL cells with simultaneous infection by two viruses with the same (A) or different (B) envelope proteins. Cells were infected by two viruses simultaneously and compared to cells that were infected by each virus separately. Efficiency of transduction was determined by flow analysis with either EGFP or mB7.1 used as a marker. Data are from one of three experiments with similar results and show means and standard errors of the means for quadruplicate wells.

TABLE 1.

Transduction of HEL and CD34+ hematopoietic cells

| Cell type | Transduction efficiency (total transduction increase) with indicated virus vector(s)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| amYWC | amB7.1 | amYWC + amB7.1 | amYWC | pgB7.1 | pgB7.1 + amYWC | |

| HEL | 14.5 ± 0.3 | 39.2 ± 3.3 | ∗25.9 ± 0.6 (66) | 14.5 ± 0.3 | 35.5 ± 1.9 | ∗44.4 ± 2.8 (125) |

| 13.0 ± 0.4 | 42.9 ± 0.9 | ∗16.9 ± 0.5 (39) | 13.0 ± 0.4 | 23.9 ± 0.3 | ∗27.0 ± 0.5 (113) | |

| 40.9 ± 2.6 | 43.9 ± 0.2 | ∗40.0 ± 0.6 (98) | 40.9 ± 2.6 | 32.5 ± 1.0 | ∗58.6 ± 0.8 (143) | |

| CD34+ | ||||||

| 5.4 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | ∗2.9 ± 0.3 (54) | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 19.9 ± 3.4 | ∗26.3 ± 0.2 (120) | |

| 8.3 ± 0.3 | 9.3 ± 2.1 | ∗∗6.2 ± 0.8 (67) | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 14.8 ± 3.1 | ∗21.5 ± 2.0 (145) | |

| 4.1 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 1.7 (92) | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 8.6 ± 0.4 (93) | |

| CD34+/CD38+ | 11.7 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.7 | ∗15.4 ± 0.4 (132) | |||

| CD34+/CD38− | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | †6.4 ± 1.6 (172) | |||

| 14.2 | 5.4 | ††16.2 (114) | ||||

Values are percentages. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ∗, difference between cumulative infection and boldfaced single infection is significant (P < 0.05); ∗∗, difference between cumulative infection and boldfaced single infection approaches significance; †, difference between cumulative infection and boldfaced single infection (P = 0.055); ††, statistics were not available for this experiment.

Supernatants from packaging lines that do not contain replication-defective vectors compete for receptor utilization.

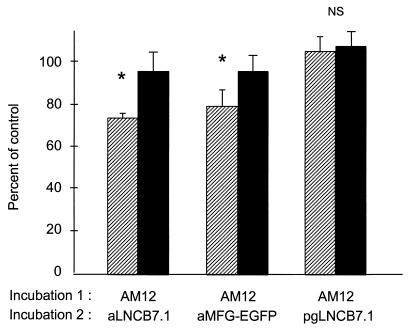

To further characterize putative factors blocking efficient retroviral transduction, HEL cells were exposed simultaneously to conditioned medium from packaging lines which had not been transfected with the retroviral backbone and to supernatant containing a replication-defective virus detectable by flow cytometry. Supernatant collected from GP+envAM12 or PA317 packaging cells was incubated on FN CH-296-coated plates. Target cells were added to “preloaded” plates, and, after 4-h, the first supernatant was replaced with aMFG-EGFP, aLNC-mB7.1, or pgLNC-mB7.1 supernatant. As seen in Fig. 4, exposure of FN CH-296 to conditioned medium from GP+envAM12 cells significantly reduced transduction of target cells by either aLNC-mB7.1 or aMFG-EGFP. To demonstrate that this effect was not unique to GP+envAM12 cells, the experiments were repeated with conditioned medium from PA317 cells. A similar degree of transduction interference was also seen (data not shown). In contrast, no inhibition of infection was demonstrated when FN CH-296 was incubated with conditioned medium from packaging cell lines used to generate amphotropic virus (GP+envAM12) followed by pg13 retrovirus (Fig. 4) or PA317 followed by pg13 retrovirus (data not shown). These data suggest that amphotropic packaging cell lines produce a factor(s) that binds to FN CH-296 and inhibits subsequent colocalization of viral particles and target cells. Since packaging lines have been previously shown to produce empty retroviral particles (18), we pretreated producer cells with tunicamycin C, an inhibitor of glycosylation known to reduce viral particle production (47, 53). This treatment led to a significant reversal of the inhibition seen by conditioned medium collected from GP+envAM12 (Fig. 4). A similar reversal of inhibition was demonstrated by treatment of PA317 packaging cells (data not shown). No inhibition was demonstrated when tunicamycin C was added to supernatant after collection, demonstrating that tunicamycin C itself is not inhibitory to virus infection.

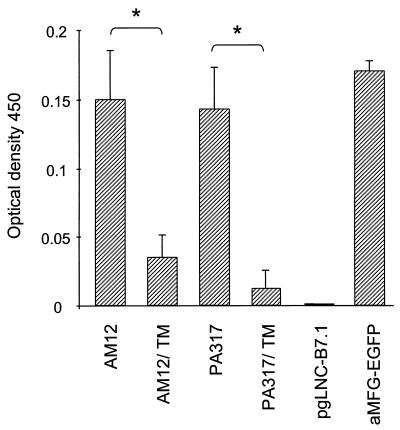

FIG. 4.

Interference of infection by conditioned medium from packaging cell lines. Supernatant from the GP+envAM12 (AM12) packaging line with (closed bars) or without (hatched bars) tunicamycin C was incubated with cells prior to infection with the indicated viruses. Transduction efficiency is measured as percent infection without preincubation, and data are means and standard deviations of three independent experiments done in duplicate. ∗, P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

Packaging lines produce envelope proteins that adhere to FN CH-296.

The data presented above strongly suggest that retroviral packaging cells produce glycosylated proteins which can bind to FN CH-296 and inhibit transduction of HEL cells. We have previously shown that retrovirus particles bind to FN CH-296 (17) and therefore have hypothesized that empty viral particles may also bind to this fragment. On the other hand, Le Doux et al. (27) have demonstrated that proteoglycans in virion-depleted conditioned medium from Ψ-Crip packaging cells are able to inhibit retroviral infection. To determine the inhibitory factor(s) binding to FN CH-296, we incubated conditioned medium from GP+envAM12 and PA317 on FN CH-296 and performed an ELISA with antibody to the amphotropic envelope protein gp70. ELISA plates were coated with FN CH-296, blocked with BSA, and then loaded with various viral supernatants. As shown in Fig. 5, supernatants from GP+envAM12, PA317, and aMFG-EGFP all contain proteins that adhere to FN CH-296 and are recognized by the gp70 antibody. As expected, pgLNC-mB7.1-conditioned medium did not contain FN CH-296-binding gp70 proteins recognized by this antibody. Once again, tunicamycin C treatment of packaging cells significantly decreased the production of gp70 proteins binding to FN CH-296. These data confirm that amphotropic packaging cell lines produce gp70 proteins and suggest that these proteins interfere with transduction of target hematopoietic cells on FN CH-296.

FIG. 5.

gp70 envelope protein from packaging cells binds to FN CH-296. Retrovirus-containing supernatants were collected from producer cells preincubated with or without tunicamycin C (TM). Binding of gp70 to FN CH-296 was detected by ELISA with an anti-gp70 monoclonal antibody. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for one experiment done in triplicate. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. ∗, P < 0.05.

Time course of receptor interference by amphotropic virus on FN CH-296.

As seen above, infection of both HEL and CD34+ cells with amphotropic virus inhibits simultaneous infection by a second amphotropic virus. To determine the duration of this interference, we performed a time course of infection with two viruses on FN CH-296. HEL cells were infected on FN CH-296-coated plates with aMFG-EGFP and, at various time points, the medium was replaced with either aLNC-mB7.1 or pgLNC-mB7.1 supernatants to monitor transduction with a second virus. As a control, cells exposed to no first virus were infected with a second virus at the same time points. Results were expressed as the number of B7.1-positive cells relative to the number of B7.1-positive cells that were infected by the second virus alone. As shown in Fig. 6, and in agreement with our previous experiments, when the second virus targets the same receptor (using aLNC-mB7.1), reduced efficiency of transduction is apparent (time zero) and this interference lasts for up to 24 h. In contrast, during the entire time course of the experiment, no interference is demonstrated when a different retroviral receptor is targeted (using pgLNC-mB7.1) (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Time course of retroviral receptor interference. HEL cells were infected with aMFG-EGFP for 4 h on FN CH-296-coated plates, after which virus was replaced with medium. At various time points, medium was replaced with either aLNC-mB7.1 (aLNCB7.1) or pgLNC-mB7.1 (pgLNCB7.1) as the second virus for an additional 4-h infection. Efficiency of infection was calculated as percent infection without the first virus. Data are means ± standard errors of the means of triplicate wells. ∗, P < 0.05 (aLNC-mB7.1 versus no first infection).

DISCUSSION

Inefficient infection of hematopoietic stem cells of large animals has prevented the application of retrovirus-mediated gene transfer to treatment of human diseases in gene therapy protocols (35, 41). Previous work in many laboratories has established that efficient transduction of murine repopulating hematopoietic stem cells is feasible (3, 7, 38, 54). In contrast, work in our laboratory and by several other investigators has demonstrated that in spite of efficient transduction of human in vitro clonogenic progenitor cells, transduction of either human NOD/SCID engrafting cells or cells capable of repopulating primates or humans is attained only at lower levels (9, 10, 13, 24, 26).

Several recent advances in the understanding of retroviral and stem cell biology have led to significant improvements in transduction of hematopoietic stem cells, as assayed with mouse repopulating assays, nonhuman primates, NOD/SCID repopulating assays, and phase I human trials (1, 4, 6, 11, 16, 22, 50). In addition to increased transduction of human CD34+ hematopoietic cells in one optimized protocol reported, Hanenberg et al. (16) noted a decrease in transduction of target CD34+ cells when these cells were exposed to virus prior to optimal prestimulation with cytokines. One explanation for these data is that the highly efficient interaction of the virus with the cognate amphotropic receptor due to the presence of FN CH-296 resulted in occupancy of all available viral receptors. Interactions of virus particles with the amphotropic viral receptor in the presence of FN CH-296 prior to cell division may have led to inefficient DNA integration of the provirus and interference with subsequent viral uptake. Such viral receptor interference is seen during infection of susceptible cells by replication-competent retroviruses and is due to receptor occupancy by retroviral envelope proteins (31, 48). In the case of replication-competent virus spread, treatment of infected target cells with tunicamycin C, an inhibitor of protein glycosylation, can reduce the production of mature envelope proteins and increase the susceptibility of treated cells to retrovirus infection (47).

Although receptor interference has been well studied during wild-type retroviral infections with replication-competent viruses (47), there is little evidence that this occurs during replication-defective transduction of mammalian cells. Le Doux et al. (27) and Walker et al. (52) demonstrated no interference of retroviral transduction by virion particles but did implicate chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in the conditioned medium of some producer cells lines in reducing retroviral infection. Since most current applications of recombinant retroviral vectors utilize replication-defective vectors packaged in specific producer cells lacking wild-type retrovirus, any evidence of receptor interference with these packaging cell lines could have important implications for the design of gene transfer protocols. Here, we demonstrate that infection of both HEL cells and human CD34+ primary hematopoietic cells is reduced during simultaneous infection with different retrovirus vectors packaged with the same envelope pseudotype. Detection of gp70 adherent to FN CH-296 and reduction in interference by pretreatment of packaging cells with tunicamycin C suggest that this interference is due to the presence of gp70 proteins in the supernatant from producer clones derived from two commonly used packaging cell lines and to binding of this protein on FN CH-296. In addition, conditioned medium from the producer cell lines tested prior to the introduction of a vector backbone suggests that these lines also produce proteins capable of interfering with infection of target cells on CH-296. Significant interference is present for up to 24 h after exposure of cells to virion particles. The timing may reflect the time required for acquisition of new receptors on the cell surface of target cells.

Interference of infection of target cells via one receptor can be overcome by simultaneous infection with a different viral receptor. Thus, simultaneous infection with viruses packaged with amphotropic and GALV envelope proteins shows no reduction in transduction efficiency. Surprisingly, simultaneous infection with two different pseudotype vectors is associated with transduction of a larger number of cells than either alone. These data suggest a unique population of cells that can be infected with only one pseudotype and a separate population of cells which can be infected via both receptors simultaneously. The biochemical or molecular basis of these differences is not clear, but Miller and Chen have previously suggested that use of 10A1 pseudotyped virus may be advantageous compared with standard amphotropic virus because of the use of more than one receptor by this pseudotype for cell entry (33). Simultaneous infection with vectors targeting different receptors may prove to be an important approach for further improving transduction of hematopoietic targets for gene therapy protocols.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the levels of amphotropic and GALV receptor mRNA vary between cells, can be modulated by various treatments, and correlate with the infection efficiency of retroviral vectors (5, 21, 42, 49). In addition, Crooks and Kohn demonstrated that growth factor exposure increases amphotropic retrovirus binding to human CD34+ hematopoietic cells (8). In this regard, our previous observations that optimal transduction of human CD34+ hematopoietic cells on FN CH-296 occurs after a short prestimulation with cytokines may relate both to increased adhesion of these cells to FN CH-296 due to modulation of integrin avidity (i.e., increased colocalization) and to increased levels of amphotropic and/or GALV receptor expression (16). In addition, the improvement in transduction after prestimulation with growth factors demonstrated by us and many other laboratories has been assumed to be associated with increased numbers of cells entering the cell cycle. Thus, optimization of transduction of primitive hematopoietic stem cell targets depends on modulation of a variety of cell parameters and simultaneous preservation of engrafting characteristics of these manipulated cells. The observations reported here may have important implications for increasing the transduction of hematopoietic stem cells or other mammalian cells in which infection efficiency is low.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of our laboratory and the Gene Therapy Working Group at Indiana University for helpful discussions. We thank Takara Shuzo Ltd. for supplying FN CH-296 (Retronectin). We thank Sharon Smoot for assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

H.H. was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. This work was supported by the Centers of Excellence in Molecular Hematology (NIDDK P50DK49218), grant NHLBI P01HL53586, and the Jon and Jennifer Simmons Charitable Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abonour R, Einhorn L, Hromas R, Robertson M J, Srour E, Traycoff C M, Bank A, Kato I, Asada K, Croop J, Smith F O, Williams D A, Cornetta K. High efficient MDR-1 gene transfer into humans using mobilized CD34+ cells transduced over recombinant fibronectin CH-296 fragment. Blood. 1998;92:690a. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bierhuizen M F, Westerman Y, Visser T P, Dimjati W, Wognum A W, Wagemaker G. Enhanced green fluorescent protein as selectable marker of retroviral-mediated gene transfer in immature hematopoietic bone marrow cells. Blood. 1997;90:3304–3315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodine D M, Seidel N E, Gale M S, Nienhuis A W, Orlic D. Efficient retrovirus transduction of mouse pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells mobilized into the peripheral blood by treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and stem cell factor. Blood. 1994;84:1482–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodine D M, Seidel N E, Orlic D. Bone marrow collected 14 days after in vivo administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and stem cell factor to mice has 10-fold more repopulating ability than untreated bone marrow. Blood. 1996;88:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chien M L, Foster J L, Douglas J L, Garcia J V. The amphotropic murine leukemia virus receptor gene encodes a 71-kilodalton protein that is induced by phosphate depletion. J Virol. 1997;71:4564–4570. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4564-4570.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conneally E, Eaves C J, Humphries R K. Efficient retroviral-mediated gene transfer to human cord blood stem cells with in vivo repopulating potential. Blood. 1998;91:3487–3493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Correll P H, Colilla S, Dave H P G, Karlsson S. High levels of human glucocerebrosidase activity in macrophages of long-term reconstituted mice after retroviral infection of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 1992;80:331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crooks G M, Kohn D B. Growth factors increase amphotropic retrovirus binding to human CD34+ bone marrow progenitor cells. Blood. 1993;82:3290–3297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deisseroth A B, Zu Z, Claxton D, Hanania E G, Fu S, Ellerson D, Goldberg L, Thomas M, Janicek K, Anderson W F, Hester J, Korbling M, Durett A, Moen R, Berenson R, Heimfeld S, Hamer J, Calvert L, Tibbits P, Talpaz M, Kantarjian H, Champlin R, Reading C. Genetic marking shows that Ph+ cells present in autologous transplants of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) contribute to relapse after autologous bone marrow in CML. Blood. 1994;83:3068–3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar C E, Cottler-Fox M, O’Shaughnessy J A, Doren S, Carter C, Berenson R, Brown S, Moen R C, Greenblatt J, Stewart F M, Leitman S F, Wilson W H, Cowan K, Young N S, Nienhuis A W. Retrovirally marked CD34-enriched peripheral blood and bone marrow cells contribute to long-term engraftment after autologous transplantation. Blood. 1995;85:3048–3057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunbar C E, Seidel N E, Doren S, Sellers S, Cline A P, Metzger M E, Agricola B A, Donahue R E, Bodine D M. Improved retroviral gene transfer into murine and rhesus peripheral blood or bone marrow repopulating cells primed in vivo with stem cell factor and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11871–11876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eipers P G, Krauss J C, Palsson B O, Emerson S G, Todd R F, Clarke M F. Retroviral-mediated gene transfer in human bone marrow cells grown in continuous perfusion culture vessels. Blood. 1995;86:3754–3762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emmons R V B, Doren S, Zujewski J, Cottler-Fox M, Carter C S, Hines K, O’Shaugnessy J A, Leitman S F, Greenblatt J J, Cowan K, Dunbar C E. Retroviral gene transduction of adult peripheral blood or marrow-derived CD34+ cells for six hours without growth factors or on autologous stroma does not improve marking efficiency assessed in vivo. Blood. 1997;89:4040–4046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans L H, Morrison R P, Malik F G, Portis J, Britt W J. A neutralizable epitope common to the envelope glycoproteins of ecotropic, polytropic, xenotropic, and amphotropic murine leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1990;64:6176–6183. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6176-6183.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanania E G, Kavanagh J, Hortobagyi G, Giles R E, Champlin R, Deisseroth A B. Recent advances in the application of gene therapy to human disease. Am J Med. 1995;99:537–552. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanenberg H, Hashino K, Konishi H, Hock R A, Kato I, Williams D A. Optimization of fibronectin-assisted retroviral gene transfer into human CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:2193–2206. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.18-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanenberg H, Xiao X L, Dilloo D, Hashino K, Kato I, Williams D A. Colocalization of retrovirus and target cells on specific fibronectin fragments increases genetic transduction of mammalian cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:876–882. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatzoglou M, Hodgson C P, Mularo F, Hanson R W. Efficient packaging of a specific VL30 retroelement by psi 2 cells which produce MoMLV recombinant retroviruses. Hum Gene Ther. 1990;1:385–397. doi: 10.1089/hum.1990.1.4-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heifetz A, Keenan W, Elbein A D. Mechanism of action of tunicamycin on the UDP-GlcNAc:dolichyl-phosphate GlcNAc-1-phosphate transferase. J Biochem. 1979;18:2186–2188. doi: 10.1021/bi00578a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadan M J, Sturm S, Anderson W F, Eglitis M A. Detection of receptor-specific murine leukemia virus binding to cells by immunofluorescence analysis. J Virol. 1992;66:2281–2287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2281-2287.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiem H P, Heyward S, Winkler A, Potter J, Allen J M, Miller A D, Andrews R G. Gene transfer into marrow repopulating cells: comparison between amphotropic and gibbon ape leukemia virus pseudotyped retroviral vectors in a competitive repopulation assay in baboons. Blood. 1997;90:4638–4645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiem H-P, Andrews R G, Morris J, Peterson L, Heyward S, Allen J M, Rasko J E J, Potter J, Miller D A. Improved gene transfer into baboon marrow repopulating cells using recombinant human fibronectin fragment Ch-296 in combination with IL-6, stem cell factor, FLT-3 ligand, and megakaryocyte growth and development factor. Blood. 1998;92:1878–1886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohn D B. Gene therapy for haematopoietic and lymphoid disorders. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohn D B, Weinberg K I, Nolta J A, Heiss L N, Lenarsky C, Crooks G M, Hanley M E, Annett G, Brooks J S, El-Khoureiy A, Lawrence K, Wells S, Moen R C, Bastian J, Williams-Herman D E, Elder M, Wara D, Bowen T, Hershfield M S, Mullen C A, Blaese R M, Parkman R. Engraftment of gene-modified umbilical cord blood cells in neonates with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Nat Med. 1995;1:1017–1023. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotani H, Newton P B I, Zhang S, Chiang Y L, Otto E, Weaver L, Blaese R M, Anderson W F, McGarrity G J. Improved methods of retroviral vector transduction and production for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:19–28. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larochelle A, Vormoor J, Hanenberg H, Wang J C Y, Bhatia M, Lapidot T, Moritz T, Murdoch B, Xiao X L, Kato I, Williams D A, Dick J E. Identification of primitive human hematopoietic cells capable of repopulating NOD/SCID mouse bone marrow: implications for gene therapy. Nat Med. 1996;2:1329–1337. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Doux J M, Morgan J R, Snow R G, Yarmush M L. Proteoglycans secreted by packaging cell lines inhibit retrovirus infection. J Virol. 1996;70:6468–6473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6468-6473.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombardi S, Massi C, Indino E, La Rosa C, Mazzetti P, Falcone M L, Rovero P, Fissi A, Pieroni O, Bandecchi P, Esposito F, Tozzini F, Bendinelli M, Garzelli C. Inhibition of feline immunodeficiency virus infection in vitro by envelope glycoprotein synthetic peptides. Virology. 1996;220:274–284. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markowitz D, Goff S, Bank A. Construction and use of a safe and efficient amphotropic packaging cell line. Virology. 1988;167:400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall E. Gene therapy’s growing pains. Science. 1995;269:1050–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.7652552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller A D. Cell surface receptors for retroviruses and implications for gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11407–11413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller A D, Buttimore C. Redesign of retrovirus packaging cell lines to avoid recombination leading to helper virus production. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2895–2902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.8.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller A D, Chen F. Retrovirus packaging cells based on 10A1 murine leukemia virus for production of vectors that use multiple receptors for cell entry. J Virol. 1996;70:5564–5571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5564-5571.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller A D, Garcia J V, von Suhr N, Lynch C M, Wilson C, Eiden M V. Construction and properties of retrovirus packaging cells based on gibbon ape leukemia virus. J Virol. 1991;65:2220–2224. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2220-2224.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller D A. Human gene therapy comes of age. Nature. 1992;357:455–460. doi: 10.1038/357455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller D G, Adam M A, Miller A D. Gene transfer by retrovirus vectors occurs only in cells that are actively replicating at the time of infection. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4239–4242. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller D G, Edwards R H, Miller A D. Cloning of the cellular receptor for amphotropic murine retroviruses reveals homology to that for gibbon ape leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:78–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moritz T, Dutt P, Xiao X L, Carstanjen D, Vik T, Hanenberg H, Williams D A. Fibronectin improves transduction of reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells by retroviral vectors: evidence of direct viral binding to chymotryptic carboxy-terminal fragments. Blood. 1996;88:855–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moritz T, Patel V P, Williams D A. Bone marrow extracellular matrix molecules improve gene transfer into human hematopoietic cells via retroviral vectors. J Clin Investig. 1994;93:1451–1457. doi: 10.1172/JCI117122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moritz T, Williams D A. Gene transfer into the hematopoietic system: vectors and gene transfer protocols. Curr Opin Hematol. 1994;1:423–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orkin, S. H., and A. G. Motulsky. 7 December 1995, posting date. Report and recommendations of the panel to assess the NIH investment in research on gene therapy. [Online.] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. www.nih.gov/news/panelrep.html.

- 42.Orlic D, Girard L J, Anderson S M, Do B K, Seidel N E, Jordan C T, Bodine D M. Transduction efficiency of cell lines and hematopoietic stem cells correlates with retrovirus receptor mRNA levels. Stem Cells. 1997;15(Suppl.):23–29. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530150805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orlic D, Girard L J, Anderson S M, Pyle L C, Yoder M C, Broxmeyer H E, Bodine D M. Identification of human and mouse hematopoietic stem cell populations expressing high levels of mRNA encoding retrovirus receptors. Blood. 1998;91:3247–3254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paul R W, Morris D, Hess B W, Dunn J, Overell R W. Increased viral titers through concentration of viral harvests from retroviral packaging lines. Hum Gene Ther. 1993;4:609–615. doi: 10.1089/hum.1993.4.5-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedersen L, Van Zeijl M, Johann S V, O’Hara B. Fungal phosphate transporter serves as a receptor backbone for gibbon ape leukemia virus. J Virol. 1997;71:7619–7622. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7619-7622.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pollok K E, Hanenberg H, Noblitt T W, Schroeder W L, Kato I, Emanuel D, Williams D A. High-efficiency gene transfer into normal and adenosine deaminase-deficient T-lymphocytes is mediated by transduction on recombinant fibronectin fragments. J Virol. 1998;72:4882–4892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4882-4892.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rein A, Schultz A M, Bader J P, Bassin R H. Inhibitors of glycosylation reverse retroviral interference. Virology. 1982;119:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rubin H. A virus in chick embryos which induced resistance to in vitro infection by Rous sarcoma virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1960;46:1105–1119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.46.8.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabatino D E, Do B Q, Pyle L C, Seidel N E, Girard L J, Spratt S K, Orlic D, Bodine D M. Amphotropic or gibbon ape leukemia virus retrovirus binding and transduction correlates with the level of receptor mRNA in human hematopoietic cell lines. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 1997;23:422–433. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1997.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Hennik P B, Verstegen M M A, Bierhuizen M F A, Limon A, Wognum A W, Cancelas J A, Barquinero J, Ploemacher R E, Wagemaker G. Highly efficient transduction of the green fluorescent protein gene in human umbilical cord blood stem cells capable of cobblestone formation in long-term cultures and multilineage engraftment of immunodeficient mice. Blood. 1998;92:4013–4022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Laer D, Thomsen S, Vogt B, Donath M, Kruppa J, Rein A, Ostertag W, Stocking C. Entry of amphotropic and 10A1 pseudotyped murine retroviruses is restricted in hematopoietic stem cell lines. J Virol. 1998;72:1424–1430. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1424-1430.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker P S, Hengge U R, Udey M C, Aksentijevich I, Vogel J C. Viral interference during simultaneous transduction with two independent helper-free retroviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:1131–1138. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.9-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson C A, Eiden M V. Viral and cellular factors governing hamster cell infection by murine gibbon ape leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1991;65:5975–5982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5975-5982.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson J M, Danos O, Grossman M, Raulet D H, Mulligan R C. Expression of human adenosine deaminase in mice reconstituted with retrovirus-transduced hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:439–443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]