Abstract

Purpose:

Understanding the association between social determinants of health (SDoHs) and microbial keratitis (MK) can inform underlying risk for patients and identify risk factors associated with worse disease, such as presenting visual acuity (VA) and time to initial presentation.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study was conducted with patients presenting with MK to the cornea clinic at a tertiary care hospital in Madurai, India. Patient demographics, SDoH survey responses, geographic pollution, and clinical features at presentation were collected. Descriptive statistics, univariate analysis, multi-variable linear regression models, and Poisson regression models were utilized.

Results:

There were 51 patients evaluated. The mean age was 51.2 years (SD = 13.3); 33.3% were female and 55% did not visit a vision center (VC) prior to presenting to the clinic. The median presenting logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) VA was 1.1 [Snellen 20/240, inter-quartile range (IQR) = 20/80 to 20/4000]. The median time to presentation was 7 days (IQR = 4.5 to 10). The average particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) concentration, a measure of air pollution, for the districts from which the patients traveled was 24.3 mg/m3 (SD = 1.6). Age- and sex-adjusted linear regression and Poisson regression results showed that higher levels of PM2.5 were associated with 0.28 worse presenting logMAR VA (Snellen 2.8 lines, P = 0.002). Patients who did not visit a VC had a 100% longer time to presentation compared to those who did (incidence rate ratio = 2.0, 95% confidence interval = 1.3–3.0, P = 0.001).

Conclusion:

Patient SDoH and environmental exposures can impact MK presentation. Understanding SDoH is important for public health and policy implications to mitigate eye health disparities in India.

Keywords: Air pollution, corneal ulcers, international eye care, microbial keratitis, social determinants of health, South India

Microbial keratitis (MK), commonly known as a corneal ulcer, is a serious, often emergent, infectious condition that is the cause of blindness in nearly 2 million cases globally each year.[1] Etiologies vary widely based on geography, with bacterial causes more common in western countries and Oceania and fungal causes equaling or exceeding bacterial causes in Asia.[2]

Social determinants of health (SDoHs) play a large role in disease severity and outcomes. The World Health Organization defines SDoH as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”[3] SDoHs include an individual’s neighborhood and built environment,[4] such as their exposure to air pollution, characterized by concentrations of suspended solid or liquid particles of various sizes.[5] Air pollution has been associated with worse outcomes for asthma,[6] heart disease,[7] and lung cancer.[8] For ophthalmic conditions, increased air pollution has been linked with dry eye syndrome,[9] glaucoma,[10] and MK.[5,11] Social risk factors (SRFs) such as lower educational attainment and lack of access to ocular protection, sanitation, and rural eye care all contribute to increasing the risk of the development and severity of MK.[1,12] In India, MK is more likely to occur in men, persons working in agricultural occupations, and persons who have experienced eye trauma.[13,14] SRFs also include food insecurity and housing instability.

Large ophthalmic health care entities focused on providing eye care in India have organizational hub-and-spoke models with tele-ophthalmology vision centers (VCs)[15] and regular “eye camps.” Those networks refer patients requiring further care to tertiary base hospitals (BHs).[16,17] As a result, identification of serious ocular pathology occurs more rapidly in rural settings where eye care would otherwise be inaccessible.

Our study aimed to investigate whether SDoHs and SRFs were associated with severity of MK at presentation to one such BH in southern India. The goal is to inform health policies to decrease the impact of these factors on ophthalmic health, thus decreasing MK morbidity.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted on patients presenting to the cornea clinic in April 2022 at a tertiary care hospital in Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee and the Institutional Review Board. Patients gave written informed consent before participating in the study.

Patients who were enrolled in a companion study, the Automated Quantitative Ulcer Analysis (AQUA, Clinical trial number NCT04420962) study, who had a stromal infiltrate measuring ≥2 mm, were recruited. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or had an in-patient or institutional status. Eyes were excluded if they had prior incisional corneal surgery, no light perception visual acuity (VA), corneal perforation, or impending perforation at presentation. Demographic data and clinical features of the infection were collected on the day of patient presentation and entered into a secure database. Organisms were identified by Gram stain, potassium hydroxide, or culture as deemed necessary by the study protocol. Patients were then approached for their consent to participate in this companion study, which was focused on SDoHs and SRFs. Surveys, originally written in English and then translated into the local language Tamil, asked for physical address (approximated by village location), housing and food security, transportation methods, and financial security.

To measure exposure to air pollution, we focused on the effect of the concentration (μg/m3) of particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5), an aerosol pollutant with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 2.5 μm that is associated with adverse health effects.[18] PM2.5 information was linked to each patient’s residential address at the district level using 2020 data produced by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago.[19] For reference of scale of PM2.5 concentration, the Environmental Protection Agency has reported an average United States national trend of 13.5 μg/m3 in 2000 to 8.5 μg/m3 in 2021.[20] As of 2013, the national standard is ideally a concentration of less than 12 μg/m3.[21]

The primary outcome variables were presenting VA and time to initial presentation to the cornea clinic. Snellen VA was converted to logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (logMAR) equivalent. For ease of conversion, values of count fingers, hand motion, and light perception were approximated by Snellen VAs of 20/4000, 20/40000, and 20/400000, respectively.[22] Time to presentation was calculated as the number of days between the date of symptom onset and the date of presentation to the cornea clinic. The distance between the patient’s residence, reported on the survey, and the closest vision center (VC), reported on hospital websites,[23,24] was determined using Google maps. Patient reported salary was converted from the survey reported Indian rupee (INR) to United States dollars (USD) using a conversion rate of 77.67 INR to 1 USD. VA displayed in Fig. 1 was grouped based on World Health Organization classification of visual impairment.[25]

Figure 1.

Point map displaying locations of patient residences (approximated by village) and their relationship with presenting Snellen VA and PM2.5 concentration. VA was stratified into normal vision (better than or equal to 20/40), low vision (between 20/40 and 20/400), and blindness (worse than 20/400) for ease of display, guided by definitions provided by the World Health Organization[25]

Statistical methods

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients were summarized with descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation (SD), median, inter-quartile range (IQR), frequency, and percentage. Univariate associations between presenting VA and time to presentation were investigated with non-parametric tests due to skewness, including Kendall rank correlations, 2-sample Wilcoxon tests, and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Multi-variable linear regression models were used to evaluate the effect of SDoH/SRF on presenting VA after adjustment for age and sex. Each SDoH/SRF was included in a separate model. SDoH/SRF investigated in models included PM2.5, annual household income, marital status, educational attainment, residence type, occupation, food and housing insecurity, mode of transportation to the clinic, if the patient was a breadwinner in the house, if the patient was financially burdened by the clinic appointment, and if the patient visited a VC prior to presenting to the BH. Model estimates were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multi-variable Poisson regression with robust variance was used to assess the effect of SDoH/SRF on time to presentation after adjustment for age and sex. Model estimates were exponentiated and interpreted as incidence rate ratio (IRR) with 95% CI. Point maps were used to visualize the spatial distribution of patient home village and its associated presenting VA or time to presentation with respect to PM2.5 concentration. All analyses were performed with R version 4.1.1 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 51 patients with MK were evaluated. Patients were on average 51.2 years old (SD = 13.3); 33.3% were female and 100% were South Asian. All but one patient had unilateral infections (98%, n = 50/51). For the patient with bilateral infections, the more severe eye was chosen as the study eye for analysis, resulting in a distribution of 47% (n = 24) right eye and 53% (n = 27) left eye infections. The median presenting logMAR VA for the study eye was 1.1 (Snellen equivalent 20/240, IQR = 20/80 to 20/4000). The median time to presentation was 7 days (IQR = 4.5 to 10).

SDoHs and SRFs of patients are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. The majority of patients were married (92%), had a middle school education or less (88%), reported an annual income of less than 2,400 USD (1,86,420 INR, 90%), lived in rural areas (78%), and had a primarily outdoor occupation (69%). Of all patients, 84% took public transit to get to the BH cornea clinic, 55% did not visit a VC prior to presenting to the BH, 77% were financially burdened by the visit, 45% reported food insecurity, and 14% reported unstable housing. The average PM2.5 concentration for the districts from which the patients traveled was 24.3 mg/m3 (SD = 1.6).

Table 1.

Outcomes, social determinants of health, and social risk factors (n=51)

| Continuous Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Presenting LogMAR VA | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.6-2.3) |

| Time to presentation to the study visit (day) | 8.9 (8.4) | 7.0 (4.5-10.0) |

| PM2.5 (mg/m3) | 24.3 (1.6) | 24.0 (23.5-24.1) |

|

| ||

| Categorical Variable | Frequency (Percent) | |

|

| ||

| Visited Aravind Vision Center or Community Clinic prior to the study visit | ||

| No | 28 (54.9) | |

| Yes | 23 (45.1) | |

| Food ran out | ||

| Often/Sometimes | 23 (45.1) | |

| Never | 28 (54.9) | |

| Transportation | ||

| Autorickshaw/Private Car/Other | 8 (15.7) | |

| Public Transit | 43 (84.3) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 4 (7.8) | |

| Married | 47 (92.2) | |

| Housing* | ||

| Unstable housing | 7 (14.0) | |

| Stable housing | 43 (86.0) | |

logMAR=logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution. SD=standard deviation. IQR=inter-quartile range. PM2.5=particular matter 2.5. *one participant did not report housing status

Supplementary Table 1.

Outcomes, social determinants of health, and social risk factors (n=51)

| Continuous Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Closest Vision Center to home (km) | 28.2 (36.8) | 14.0 (7.5-29.4) |

|

| ||

| Categorical Variable | Frequency (Percent) | |

|

| ||

| Annual Household Income | ||

| Less than 323 USD (25,092 INR) | 3 (5.9) | |

| 324-960 USD (25,093-74,556 INR) | 14 (27.5) | |

| 961-1,600 USD (74,557-124,272 INR) | 20 (39.2) | |

| 1,601-2,400 USD (124,273-186,420 INR) | 9 (17.6) | |

| Greater than 2,401 USD (186,421 INR) | 5 (9.8) | |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 16 (31.4) | |

| Primary School | 15 (29.4) | |

| Middle School | 14 (27.5) | |

| High school/Diploma/Undergrad/Postgrad | 6 (11.8) | |

| Residence Type | ||

| Rural | 40 (78.4) | |

| Urban/District | 11 (21.6) | |

| Occupation | ||

| Indoor | 14 (27.5) | |

| Outdoor | 35 (68.6) | |

| Indoor and Outdoor | 2 (3.9) | |

| Breadwinner in the house | ||

| No | 33 (64.7) | |

| Yes | 18 (35.3) | |

| Food worried | ||

| Often/Sometimes | 22 (43.1) | |

| Never | 29 (56.9) | |

| Financially burdened because of the visit | ||

| No | 12 (23.5) | |

| Yes | 39 (76.5) | |

| Number of people in the household | ||

| 1-2 | 9 (17.6) | |

| 3 | 19 (37.3) | |

| 4 | 15 (29.4) | |

| 5-6 | 8 (15.7) | |

SD=standard deviation. IQR=interquartile range. USD=United States dollar. INR=Indian rupee

Associations between presenting VA and SDoH/SRF are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2. Patients who lived in districts with higher levels of PM2.5 presented with significantly worse VA (Kendall tau = 0.28, P = 0.007). The remaining SDoH and SRF measures were not significantly associated with presenting VA. There was a trend for patients who never visited a VC to present with worse VA than those who had (median logMAR = 1.8 vs 1.1, P = 0.12). There was a trend for patients who often or sometimes worried about food running out to present with worse VA than those who never worried about it (median logMAR = 1.7 vs 1.3, P = 0.12).

Table 2.

Univariate associations of social determinants of health and social risk factors with presenting visual acuity and time to presentation

| Continuous Variable | Presenting visual acuity | Time to presentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Kendall Correlation | P | Kendall Correlation | P | |

| PM2.5 (µg/m3) | 0.28 | 0.0067 | 0.08 | 0.4620 |

|

| ||||

| Categorical Variable | Mean (SD), Median | P | Mean (SD), Median | P |

|

| ||||

| Visited Vision Center or Community Clinic prior to the study visit | ||||

| No | 1.8 (1.2), 1.5 | 0.1184 | 11.5 (10.1), 7.0 | 0.0217 |

| Yes | 1.1 (0.8), 1.0 | 5.7 (3.9), 6.0 | ||

| Food ran out | ||||

| Often/Sometimes | 1.7 (1.1), 1.5 | 0.1230 | 7.2 (5.1), 6.0 | 0.3860 |

| Never | 1.3 (1.1), 1.1 | 10.3 (10.2), 7.0 | ||

| Transportation | ||||

| Autorickshaw/Private Car/Other | 1.1 (1.0), 1.0 | 0.3285 | 6.0 (6.3), 3.5 | 0.0927 |

| Public Transit | 1.5 (1.1), 1.1 | 9.4 (8.7), 7.0 | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 0.6 (0.8), 0.4 | 0.0618 | 5.5 (3.7), 5.0 | 0.4379 |

| Married | 1.5 (1.1), 1.1 | 9.2 (8.6), 7.0 | ||

| Housing | ||||

| Unstable housing | 1.0 (0.7), 1.1 | 0.186 | 4.6 (2.8), 5.0 | 0.1322 |

| Stable housing | 1.6 (1.1), 1.1 | 9.6 (8.9), 7.0 | ||

PM2.5=particular matter 2.5. SD=standard deviation

Supplementary Table 2.

Univariate associations of social determinants of health and social risk factors with presenting visual acuity and time to presentation

| Continuous Variable | Presenting visual acuity | Time to presentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Kendall Correlation | P | Kendall Correlation | P | |

| Closest Vision Center to home (km) | 0.07 | 0.4767 | 0.15 | 0.1430 |

|

| ||||

| Categorical Variable | Mean (SD), Median | P | Mean (SD), Median | P |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.6 (1.1), 1.3 | 0.1748 | 9.6 (9.8), 6.5 | 0.8093 |

| Female | 1.2 (1.0), 1.0 | 7.5 (4.3), 7.0 | ||

| Annual Household Income | ||||

| Less than 323 USD (25,092 INR) | 1.8 (1.3), 1.1 | 0.3403 | 11.7 (7.6), 10.0 | 0.7201 |

| 324-960 USD (25,093-74,556 INR) | 1.5 (1.2), 1.3 | 7.3 (4.6), 6.5 | ||

| 961-1,600 USD (74,557-124,272 INR) | 1.5 (1.0), 1.1 | 8.0 (8.6), 6.0 | ||

| 1,601-2,400 USD (124,273-186,420 INR) | 1.7 (1.1), 1.3 | 11.0 (11.2), 7.0 | ||

| Greater than 2,401 USD (186,421 INR) | 0.7 (0.9), 0.5 | 11.8 (11.8), 7.0 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Illiterate | 1.6 (1.0), 1.2 | 0.5442 | 7.2 (4.4), 6.0 | 0.4135 |

| Primary School | 1.7 (1.2), 1.3 | 6.9 (5.4), 5.0 | ||

| Middle School | 1.2 (1.0), 1.0 | 11.0 (9.9), 8.5 | ||

| High school/Diploma/Undergrad/Postgrad | 1.3 (1.3), 0.8 | 13.3 (15.8), 4.5 | ||

| Residence Type | ||||

| Rural | 1.5 (1.0), 1.1 | 0.2354 | 8.3 (7.8), 6.5 | 0.4966 |

| Urban/District | 1.3 (1.4), 0.5 | 10.9 (10.5), 7.0 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Indoor | 1.5 (1.2), 1.1 | 0.9407 | 12.6 (10.6), 8.5 | 0.2371 |

| Outdoor | 1.5 (1.0), 1.1 | 7.3 (7.0), 6.0 | ||

| Indoor and outdoor | 1.9 (2.0), 1.9 | 10.5 (9.2), 10.5 | ||

| Breadwinner in the house | ||||

| No | 1.6 (1.1), 1.1 | 0.2979 | 8.8 (8.3), 7.0 | 0.9289 |

| Yes | 1.3 (1.2), 1.1 | 9.1 (8.7), 7.0 | ||

| Food worried | ||||

| Often/Sometimes | 1.7 (1.1), 1.5 | 0.1513 | 7.3 (5.2), 6.5 | 0.4908 |

| Never | 1.3 (1.0), 1.1 | 10.1 (10.1), 7.0 | ||

| Visit financially burdened | ||||

| No | 1.2 (1.1), 0.6 | 0.1661 | 9.5 (11.1), 5.5 | 0.5764 |

| Yes | 1.6 (1.1), 1.1 | 8.7 (7.5), 7.0 | ||

| Number of people in the household | ||||

| 1-2 | 1.3 (1.0), 1.1 | 0.4297 | 9.0 (6.4), 7.0 | 0.6133 |

| 3 | 1.3 (1.0), 1.1 | 7.7 (7.6), 7.0 | ||

| 4 | 1.4 (0.9), 1.3 | 11.5 (11.3), 7.0 | ||

| 5-6 | 2.2 (1.5), 2.3 | 6.8 (5.1), 5.5 | ||

SD=standard deviation. USD=United States dollar. INR=Indian rupee

Linear regression model results showed that every 1 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was associated with a 0.28 worse presenting logMAR VA after adjustment for age and sex (Snellen = 2.8 lines, 95% CI = 0.1–0.5, P = 0.002) [Table 3 and Supplementary Table 3]. Patients who did not visit a VC prior to presenting to the BH had a 0.6 worse presenting logMAR VA compared to those who did after adjustment for age and sex (Snellen = 6 lines, 95% CI = 0.0–1.2, P = 0.04). Patient locations, grouped by their corresponding presenting VA, were plotted on a point map to show the relative locations to the BH and the levels of PM2.5 by district [Fig. 1]. The majority of patients with low vision (Snellen 20/400 to 20/40, 23.5% of the cohort) were located in districts with PM2.5 levels of 23.9, 23.5, and 24.0 μg/m3 (Madurai, Sivagangai, and Dindigul districts, respectively). Patients with blindness (Snellen 20/400 or worse, 17.6%) were located in districts where the PM2.5 levels were 27.7 and 24.1 μg/m3 (Karur and Virudhunagar districts, respectively).

Table 3.

Linear regression model estimates for the effect of SDoHs and SRFs on presenting visual acuity. Poisson regression model estimates for the effect of SDoH and SRF on time to presentation. All models were adjusting for age and sex. Each SDoH/SRF was included in a separate model

| Variable | Presenting visual acuity | Time to presentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | P | IRR | 95% CI | P | |

| PM2.5 (µg/m3) | 0.28 | 0.1, 0.5 | 0.0018 | 1.17 | 1.0, 1.3 | 0.0241 |

| Did not visit vision center | 0.60 | 0.0, 1.2 | 0.0375 | 2.00 | 1.3, 3.0 | 0.0011 |

| Often/Sometimes Food Ran out vs Never | 0.44 | -0.1, 1.0 | 0.1333 | 0.71 | 0.5, 1.1 | 0.1296 |

| Public Transit vs Autorickshaw/Private Car/Other | 0.16 | -0.7, 1.0 | 0.6975 | 1.74 | 0.9, 3.5 | 0.1086 |

| Married vs Single | 0.58 | -0.7, 1.9 | 0.3616 | 2.57 | 1.2, 5.6 | 0.0183 |

| Unstable Housing vs Stable Housing | -0.71 | -1.5, 0.1 | 0.0946 | 0.47 | 0.3, 0.8 | 0.0057 |

CI=Confidence Interval. IRR=Incidence Rate Ratio, PM2.5=particular matter 2.5

Supplementary Table 3.

Linear regression model estimates for the effect of SDoH and SRF on presenting visual acuity. Poisson regression model estimates for the effect of SDoH and SRF on time to presentation. All models were adjusting for age and sex. Each SDoH/SRF was included in a separate model

| Variable | Presenting visual acuity | Time to presentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | P | Estimate | 95% CI | P | |

| Annual Household Income* | 0.4731 | |||||

| 324-960 USD (25,093-74,556 INR) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 961-1,600 USD (74,557-124,272 INR) | -0.5 | -1.4, 0.4 | 0.2501 | 1.08 | 0.7, 1.7 | 0.7039 |

| 1,601-2,400 USD (124,273-186,420 INR) | -0.23 | -1.4, 0.9 | 0.6893 | 1.43 | 0.7, 3.1 | 0.3738 |

| Education | 0.7257 | |||||

| Illiterate | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Primary School | -0.01 | -0.8, 0.8 | 0.9879 | 0.94 | 0.6, 1.6 | 0.8235 |

| Middle School | -0.41 | -1.2, 0.4 | 0.3215 | 1.50 | 0.9, 2.6 | 0.1444 |

| High School/Diploma/Undergrad/Postgrad | -0.19 | -1.4, 1.0 | 0.7528 | 1.83 | 0.6, 5.3 | 0.2644 |

| Urban/District vs Rural | -0.19 | -0.9, 0.6 | 0.6277 | 1.19 | 0.6, 2.3 | 0.6028 |

| Outdoor Occupation vs Indoor Occupation† | 0.11 | -0.5, 0.8 | 0.7372 | 0.58 | 0.3, 1.0 | 0.0517 |

| Was breadwinner in the house | -0.17 | -0.8, 0.5 | 0.6081 | 0.90 | 0.5, 1.7 | 0.7502 |

| Often/Sometimes Food Worried vs Never | 0.5 | -0.1, 1.1 | 0.0874 | 0.73 | 0.5, 1.1 | 0.1582 |

| Visit was financially burdened | 0.42 | -0.3, 1.1 | 0.2464 | 1.02 | 0.5, 2.1 | 0.9647 |

CI=Confidence Interval. *Income groups of less than 323 USD (25,092 INR) and greater than 2,401 USD (186,421 INR) were excluded from linear and Poisson regression due to a small sample size. †Patients who worked both indoor and outdoor were excluded from the linear regression model due to a small sample size

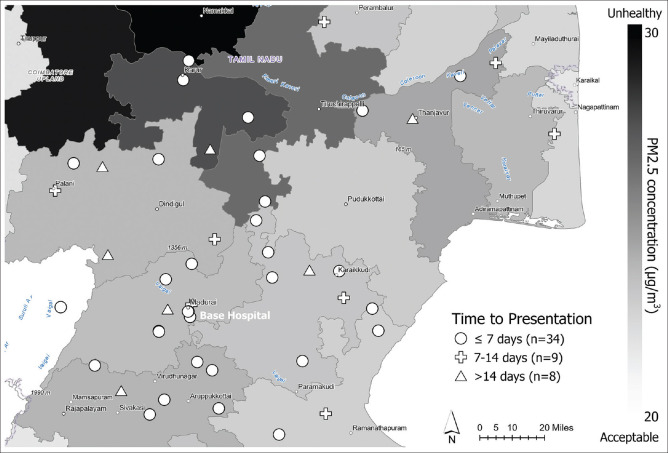

Associations between time to presentation to the BH and SDoH/SRF are also shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2. Those who did not visit a VC prior to the study visit took significantly longer to present to the BH than those who had visited one (mean = 11.5 vs 5.7 days, P = 0.02). PM2.5 levels and other SDoHs and SRFs were not significantly associated with time to initial presentation to the BH. The average time to presentation to the BH was slightly longer for patients who took public transit to the clinic compared to those who used other modes of transportation (9.4 vs 6.0 days, P = 0.09). However, Poisson regression model results showed that every 1 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was associated with a 17% longer time to presentation (10.1 days vs 8.6 days) after adjustment for age and sex (IRR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.0–1.3, P = 0.02). Patients who did not visit a VC prior to presenting to the BH had a 100% longer time to presentation (11.4 days vs 5.7 days) compared to those who did (IRR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.3–3.0, P < 0.01) after adjustment for age and sex. Further, patients who were married had a longer time to presentation (IRR = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.2–5.6, P = 0.02), while patients with unstable housing had a lesser time to presentation compared to those with stable housing (IRR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.3–0.8, P = 0.01) after adjustment for age and sex. Patient locations, grouped by their corresponding time to presentation, were plotted on a point map to show the relative locations to the BH and the levels of PM2.5 by district [Fig. 2]. The majority of patients with less than 7 days to presentation (41% of the cohort) were located in districts with PM2.5 levels of 23.9, 24.1, and 23.5 μg/m3 (Madurai, Virudhunagar, and Sivagangai, respectively).

Figure 2.

Point map displaying locations of patient residences (approximated by village) and their relationship with time to initial presentation (days) and PM2.5 concentration. Time to presentation was categorized ≤7 days, 8 to 14 days, and >14 days for ease of display

Discussion

This study explored the association between SDoH and SRF, including pollution, food and housing insecurity, access to regional eye care, transportation method, and financial burden of clinical care, with presenting VA and time to presentation for MK patients in southern India. The results of this study demonstrated that patients whose villages had higher levels of PM2.5 and those who did not initially visit a VC had significantly worse presenting VA. These two factors, in addition to being married, were associated with a longer time to presentation. Interestingly, those who reported unstable housing had a shorter time to presentation.

These results corroborate previous literature that has examined air pollution and MK outcomes in Korea. Lee and colleagues evaluated particulate matter 10 (PM10) spatial data and emergency room (ER) visits for keratitis.[11] They reported that in areas with the highest PM10 concentrations, there were significantly more ER visits for keratitis as compared to the areas with the bottom 20% concentrations of PM10 (p < 0.05). For acute herpes simplex keratitis, Sendra and colleagues determined that mice that were exposed to air pollution had greater herpes simplex keratitis severity, perhaps because of a local imbalance of innate and adaptive immune responses.[5] Previous research has also shown that dry eye, a known risk factor for MK, has been exacerbated by air pollution. Mo and colleagues found that among 5,062 patients in China, there were associations with PM2.5 and outpatient visits for dry eye disease.[26] Additionally, Shin and colleagues in Korea demonstrated that exposure to PM10 was associated with higher cataract incidence (hazard ratio 1.069, 95% CI: 1.025–1.115).[27] A study conducted in China by Fu and colleagues found that in 9,737 patients, a 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10, PM2.5, sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and carbon monoxide (CO) concentrations was associated with more conjunctivitis outpatient visits.[28]

In order to offer health research-based recommendations for air quality management in countries with high levels of pollution, the World Health Organization periodically releases air quality targets for a number of pollutants, including PM2.5. The latest update from 2021[29] recommends a PM2.5 annual mean of less than 5 μg/m3, a level which is far below that currently found in many Indian cities,[19,30] including the districts in which the patients from our study reside. Data regarding systemic illnesses exacerbated by high pollution, discussed previously, along with the results from our study regarding ocular morbidity, may inform future legislation to hasten the efforts to curb air pollution.

Patients who never visited a VC had significantly longer times to initial presentation to the BH than those who initially visited one and were subsequently referred to the BH for further evaluation. Though not statistically significant, those patients with VCs farther away from their residence also tended to present later. These findings highlight that poor access to care is likely associated with worse disease severity at presentation. The benefits of the hub-and-spoke system have been previously outlined in other works.[17] Efforts to expand the reach of regional screening centers are intended to improve access to care, so disease is identified and managed earlier.

Patients who were married took longer to present for care than those who were single. This may be because there were more household responsibilities to fulfill before seeking personal medical care. Additionally, those who reported unstable housing presented more quickly. It is possible that this occurred because patients with unstable housing tended to live closer to the VC than those with stable housing (median distance = 6.6 vs 16.2, p=0.108), allowing for sooner visits to the VC.

There are limitations to this work. First, the limited sample size may have precluded the identification of statistical significance between previously associated SDoH and severity of MK at presentation. The limited sample size also did not provide the necessary power to test the correlation between infection severity, occupation, and PM2.5 levels. Second, this study only included patients from South India, so these findings may not generalize to other regions of India or globally. Last, the PM2.5 concentrations for 2020, utilized in this work, were actually lower by 33% due to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.[31] Therefore, it is possible that 2022 PM2.5 readings would be higher than those we reported, likely augmenting the reported associations.

Conclusion

The findings from our research demonstrate the association between air pollution, specifically PM2.5, and presenting VA for patients with MK. Future work can explore the impact of SDoH and SRF on eye and vision outcomes after MK resolution. Vision loss and blindness have direct and indirect economic burden.[32-34] Future research could examine other forms of air pollution such as ozone (O3), carbon monoxide (CO), ammonia (NH3), nitric oxide (NO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and its associations with MK and additional eye diseases affecting the cornea. MK has also been linked to lack of access to clean water for hygiene; future research could examine water quality impacts on MK outcomes as well.

Our research adds to the literature on the association of air pollution with negative health outcomes in India.[35-39] Health policy, public health initiatives, and monitoring and regulating surrounding air pollution levels in India could improve eye health for persons living in areas with high pollution.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was supported by funding from the National Eye Institute (R01EY031033, Maria A. Woodward), the National Institutes of Health (GM111725, Patrice M. Hicks), a Research to Prevent Blindness Career Advancement Award (Maria A. Woodward), and the Michigan Ophthalmology Trainee Career Development Award (Anvesh Annadanam). The other authors do not have any disclosures.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The personnel who conducted this study were supported in part by a gift from Ms. Susan Lane.

References

- 1.Ting DSJ, Ho CS, Deshmukh R, Said DG, Dua HS. Infectious keratitis: An update on epidemiology, causative microorganisms, risk factors, and antimicrobial resistance. Eye. 2021;35:1084–101. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01339-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ung L, Bispo PJM, Shanbhag SS, Gilmore MS, Chodosh J. The persistent dilemma of microbial keratitis: Global burden, diagnosis, and antimicrobial resistance. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64:255–71. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Social Determinants of Health. U. S. Dep. Heal. Hum. Serv. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 20]. Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health .

- 4.Social Determinants of Health, CDC. 2022. [Last accessed on 2022 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/sdoh/index.html .

- 5.Sendra VG, Tau J, Zapata G, Lasagni Vitar RM, Illian E, Chiaradía P, et al. Polluted air exposure compromises corneal immunity and exacerbates inflammation in acute herpes simplex keratitis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:618597. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.618597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarnieri M, Balmes JR. Outdoor air pollution and asthma. Lancet. 2014;383:1581–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD, Biswal S, Rajagopalan S. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: Lessons learned from air pollution. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:656–72. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0371-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner MC, Andersen ZJ, Baccarelli A, Diver WR, Gapstur SM, Pope CA, et al. Outdoor air pollution and cancer: An overview of the current evidence and public health recommendations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:460–79. doi: 10.3322/caac.21632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandell JT, Idarraga M, Kumar N, Galor A. Impact of air pollution and weather on dry eye. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3740. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua SYL, Khawaja AP, Morgan J, Strouthidis N, Reisman C, Dick AD, et al. The relationship between ambient atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) and glaucoma in a large community cohort. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:4915. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-28346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JY, Kim JW, Kim EJ, Lee MY, Nam CW, Chung IS. Spatial analysis between particulate matter and emergency room visits for conjunctivitis and keratitis. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018;30:41. doi: 10.1186/s40557-018-0252-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: A social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97:407–19. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gopinathan U, Sharma S, Garg P, Rao G. Review of epidemiological features, microbiological diagnosis and treatment outcome of microbial keratitis: Experience of over a decade. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:273. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.53051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Meenakshi R, Padmavathy S, Shivakumar C, Srinivasan M. Microbial keratitis in South India: Influence of risk factors, climate, and geographical variation. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:61–9. doi: 10.1080/09286580601001347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aravind Vision Centre Network. Aravind Eye Care System. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 07]. Available from: https://aravind.org/vision-centre/#v_centres .

- 16.Schehlein EM, Yadalla D, Hutton D, Stein JD, Venkatesh R, Ehrlich JR. Detection of posterior segment eye disease in rural eye camps in South India: A nonrandomized cluster trial. Ophthalmol Retin. 2021;5:1107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komal S, Radhakrishnan N, Vardhan S A, Prajna NV. Effectiveness of a tele-ophthalmology vision center in treating corneal disorders and its associated economic benefits. Cornea. 2022;41:688–91. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazarenko Y, Pal D, Ariya PA. Air quality standards for the concentration of particulate matter 2.5, global descriptive analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99:125–37D. doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.245704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Air Quality Life Index. [Last accessed on 2022 Jul 31]. Available from: https://aqli.epic.uchicago.edu/country-spotlight/india/

- 20.Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Trends. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2022. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/air-trends/particulate-matter-pm25-trends .

- 21.What are the Air Quality Standards for PM?Environmental Protection Agency 2022. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www3.epa.gov/region1/airquality/pm-aq-standards.html .

- 22.Holladay JT. Proper method for calculating average visual acuity. J Refract Surg. 1997;13:388–91. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19970701-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aravind Eye Care Network. Aravind Eye Care System. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 07]. Available from: http://www.auromap.org/map.php?pid=897 .

- 24.Aravind Vision Centres Map. Aravind Eye Care System. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 07]. Available from: http://www.auromap.org/map.php?pid=755 .

- 25.Steinmetz JD, Bourne RRA, Briant PS, Flaxman SR, Taylor HRB, Jonas JB, et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The right to sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2021;9:e144–60. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mo Z, Fu Q, Lyu D, Zhang L, Qin Z, Tang Q, et al. Impacts of air pollution on dry eye disease among residents in Hangzhou, China: A case-crossover study. Environ Pollut. 2019;246:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.11.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin J, Lee H, Kim H. Association between exposure to ambient air pollution and age-related cataract: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9231. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu Q, Mo Z, Lyu D, Zhang L, Qin Z, Tang Q, et al. Air pollution and outpatient visits for conjunctivitis: A case-crossover study in Hangzhou, China. Environ Pollut. 2017;231:1344–50. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines. 2021. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 07]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/345334/9789240034433-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y .

- 30.Kesavachandran CN, Prathish KP, Sakhre S, Ajay SV, Rahul CM. Proposed city-specific interim targets for India based on WHO air quality guidelines 2021. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:30802–7. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar P, Hama S, Omidvarborna H, Sharma A, Sahani J, Abhijith KV, et al. Temporary reduction in fine particulate matter due to 'anthropogenic emissions switch-off'during COVID-19 lockdown in Indian cities. Sustain Cities Soc. 2020;62:102382. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Zhang P, Sublett F, Lamuda PA, Lundeen EA, et al. The economic burden of vision loss and blindness in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marques AP, Ramke J, Cairns J, Butt T, Zhang JH, Muirhead D, et al. Global economic productivity losses from vision impairment and blindness. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100852. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mannava S, Borah R, Shamanna B. Current estimates of the economic burden of blindness and visual impairment in India: A cost of illness study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:2141. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2804_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravishankara AR, David LM, Pierce JR, Venkataraman C. Outdoor air pollution in India is not only an urban problem. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:28640–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007236117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chowdhury S, Dey S. Cause-specific premature death from ambient PM2.5 exposure in India: Estimate adjusted for baseline mortality. Environ Int. 2016;91:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.David LM, Ravishankara AR, Kodros JK, Pierce JR, Venkataraman C, Sadavarte P. Premature mortality due to PM 2.5 over India: Effect of atmospheric transport and anthropogenic emissions. GeoHealth. 2019;3:2–10. doi: 10.1029/2018GH000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajak R, Chattopadhyay A. Short and long term exposure to ambient air pollution and impact on health in India: A systematic review. Int J Environ Health Res. 2020;30:593–617. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2019.1612042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patankar AM, Trivedi PL. Monetary burden of health impacts of air pollution in Mumbai, India: Implications for public health policy. Public Health. 2011;125:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]