Abstract

Eukaryotic life depends on the functional elements encoded by both the nuclear genome and organellar genomes, such as those contained within the mitochondria. The content, size, and structure of the mitochondrial genome varies across organisms with potentially large implications for phenotypic variance and resulting evolutionary trajectories. Among yeasts in the subphylum Saccharomycotina, extensive differences have been observed in various species relative to the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but mitochondrial genome sampling across many groups has been scarce, even as hundreds of nuclear genomes have become available. By extracting mitochondrial assemblies from existing short-read genome sequence datasets, we have greatly expanded both the number of available genomes and the coverage across sparsely sampled clades. Comparison of 353 yeast mitochondrial genomes revealed that, while size and GC content were fairly consistent across species, those in the genera Metschnikowia and Saccharomyces trended larger, while several species in the order Saccharomycetales, which includes S. cerevisiae, exhibited lower GC content. Extreme examples for both size and GC content were scattered throughout the subphylum. All mitochondrial genomes shared a core set of protein-coding genes for Complexes III, IV, and V, but they varied in the presence or absence of mitochondrially-encoded canonical Complex I genes. We traced the loss of Complex I genes to a major event in the ancestor of the orders Saccharomycetales and Saccharomycodales, but we also observed several independent losses in the orders Phaffomycetales, Pichiales, and Dipodascales. In contrast to prior hypotheses based on smaller-scale datasets, comparison of evolutionary rates in protein-coding genes showed no bias towards elevated rates among aerobically fermenting (Crabtree/Warburg-positive) yeasts. Mitochondrial introns were widely distributed, but they were highly enriched in some groups. The majority of mitochondrial introns were poorly conserved within groups, but several were shared within groups, between groups, and even across taxonomic orders, which is consistent with horizontal gene transfer, likely involving homing endonucleases acting as selfish elements. As the number of available fungal nuclear genomes continues to expand, the methods described here to retrieve mitochondrial genome sequences from these datasets will prove invaluable to ensuring that studies of fungal mitochondrial genomes keep pace with their nuclear counterparts.

Keywords: yeast1, mitochondria2, evolution3, selection4, diversity5. (Min.5-Max. 8)

1. Introduction

Eukaryotic evolution is a history of multiple genomes coming together. The acquisition of the mitochondria via endosymbiosis enabled new metabolic capacities, but it required the coevolution of two distinct genomes over time and created a novel dynamic (Muñoz-Gómez et al., 2015; Zachar and Szathmáry, 2017). In the vast majority of eukaryotic organisms, the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) has been vastly reduced to encode a small number of respiratory proteins and their corresponding translational machinery (Johnston and Williams, 2016). All other ancestral mitochondrial genes were either lost or transferred to the nuclear genome, which encodes nearly all genes required for the various mitochondrial functions (Adams and Palmer, 2003). Among extant mtDNAs, there is considerable variation in specific gene content, genome structure, and idiosyncrasies of gene expression (Santamaria et al., 2007; Gualberto et al., 2014; Hao, 2022; Dowling and Wolff, 2023). Dense sampling of eukaryotic taxa is required to understand how this variation arises and its impacts on the evolution and function of both genomes.

Budding yeasts of the subphylum Saccharomycotina (hereafter, yeasts) provide a valuable model for exploring this variation further. The early sequencing of the mtDNA of the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae provided a contrast to the picture of mitochondrial evolution that was emerging from animal studies. Whereas most animal mtDNAs were found to be highly gene-dense, small at typically under 20kb (Santamaria et al., 2007), and lacking introns, the S. cerevisiae mtDNA was several times larger (~75–85kb), contained fewer genes due to lacking any of the canonical mitochondrially-encoded components of Complex I of the electron transport chain, and contained introns in several genes (Foury et al., 1998). Further studies of other eukaryotic groups confirmed that marked differences from the smaller genome seen in animals are the norm (Gualberto and Newton, 2017; Sandor et al., 2018). The addition of mtDNAs from other yeasts showed that differences in genome size were widespread and that many yeast mtDNAs still encoded a canonical Complex I (Freel et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2017). However, the current sampling of yeast mtDNAs (Christinaki et al., 2022) remains heavily tilted towards yeasts in the order Saccharomycetales, which contains S. cerevisiae, and the order Serinales, which contains the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans (Butler et al., 2009), but these are only two of the 12 orders in the 400-million-year-old subphylum Saccharomycotina (Shen et al., 2018; Groenewald et al., 2023).

Yeasts have become an important model for studying the dynamics of genome evolution and, in particular, its interplay with metabolism (Scannell et al., 2011; Hittinger, 2013; Hittinger et al., 2015; Opulente et al., 2018). Nuclear genome sequences for hundreds of species across all major clades within Saccharomycotina are now available (Shen et al., 2018). However, the availability of mtDNAs for this subphylum is comparatively lacking. In this work, we demonstrate that yeast mtDNAs can be recovered from publicly available short-read genome sequencing datasets, and we more than doubled the number of available mitochondrial genomes across the subphylum to 353 mtDNAs. We show that there is considerable variation in genome size, GC content, patterns of selection, and intron content. Comparisons of gene content revealed that, while there was a major loss of Complex I in the evolution of the ancestor of the orders Saccharomycetales and Saccharomycodales, there are several additional independent losses in other orders. This dataset provides new opportunities to better understand mitochondrial evolution and its relationship to nuclear genome evolution.

2. Results

2.1. Mitochondrial Genome Sequence Rescue

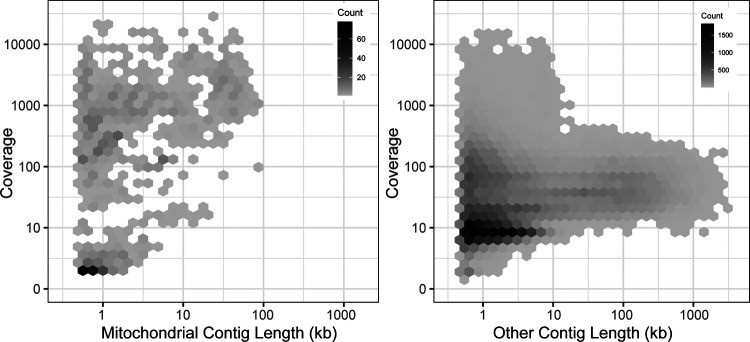

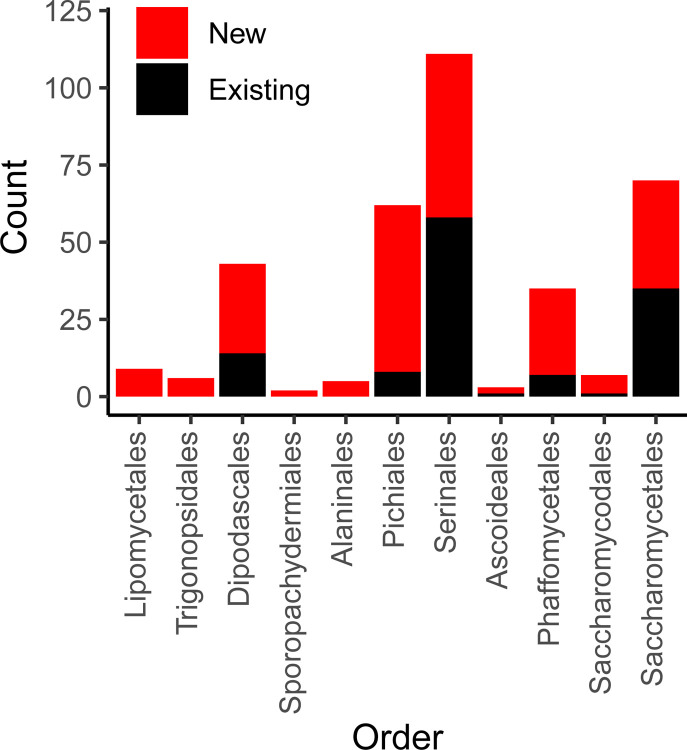

To expand the availability of mtDNAs across the subphylum Saccharomycotina, we used a two-pronged approach: first searching for mitochondrial sequences in existing genome assemblies, followed by constructing new genome assemblies using assemblers specialized in generating organellar genomes from short sequencing reads. By searching for matches to existing references, we identified a treasure trove of mitochondrial sequences within the existing assemblies with sizes in the expected ranges for mtDNAs and with elevated coverage relative to the rest of the assembly, which would be consistent with the high copy number expected for the mtDNA (Solieri, 2010) (Figure 1). The success rate for extracting nearly complete mtDNAs was quite high for newer assemblies, but it was lower for older assemblies due to either lack of coverage, previously applied computational filters to remove mtDNA, or potentially the use of strains lacking mtDNA to reduce sequencing costs (Supplemental Figure 1). When raw DNA sequencing reads were readily available, reassembly by targeting mitochondrial sequences proved to be even more effective. Out of 232 species assessed via both approaches, 19 were best assembled within the nuclear assembly, whereas 212 were best completed via reassembly (38 by plasmidSPAdes (Antipov et al., 2016) and 174 by NOVOPlasty (Dierckxsens et al., 2017)). After reducing the mitochondrial genome assemblies to the best representative for each species (Supplemental Table 1), the number of Saccharomycotina species with mtDNAs available increased from 132 (Christinaki et al., 2022) to 353, which included dramatically improved representation in several clades (Figure 2). Many of these mtDNAs were assembled as a circle, but a small number of assemblies remained fragmented, which resulted in missing portions with contig breakpoints that occasionally overlapped annotated genes. The pipeline for searching existing genome assemblies for mitochondrial sequences is available here: https://github.com/JFWolters/IdentifyMitoContigs.

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial Contig Profile.

The coverage and length profile of contigs from 196 assemblies newly sequenced in (Shen et al., 2018) that were flagged as putative mitochondrial contigs versus all other contigs is displayed (log10 scaling). The most useful mitochondrial contigs generally have a profile of elevated coverage with sizes between 10 and 100 kb, a combination rarely found in other contigs, although strict diagnostic cutoffs are not evident. Many poor-quality putative mitochondrial contigs were found in nuclear genome assemblies, but these were not present in mitochondrially-focused reassemblies.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial Genome Counts by Taxonomic Order.

The count of genomes for both newly added and existing genomes from public repositories are displayed according to taxonomic order (classifications recently described by Groenewald et al. 2023). For nearly all orders, a majority of genomes are new (barring Saccharomycetales (35 new versus 35 existing) and Serinales (53 new versus 58 existing)).

2.2. Phylogeny and Genome Characteristics

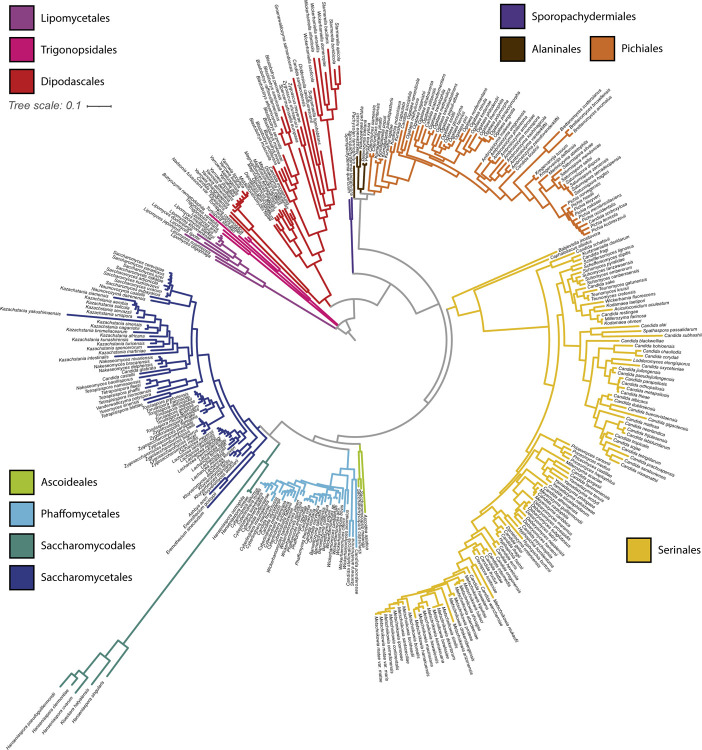

We constructed a phylogeny of yeast mtDNAs based on concatenation of the core protein-coding genes (Figure 3). Overall concordance with the existing nuclear phylogeny was reasonably high (normalized Robinson-Foulds distance 0.24 between matched subtrees). Placement of the recently described (Groenewald et al., 2023) taxonomic orders (previously designated as major clades (Shen et al., 2018)) was consistent between the phylogenies, barring three exceptions: two Trigonopsis species grouped closer to Lipomycetales than other Trigonopsidales; the Alaninales were paraphyletic with respect to the Pichiales, rather than forming a single monophyletic outgroup; and the placement of the fast-evolving lineage of Hanseniaspora (order Saccharomycodales) was uncertain due to the long branch at the root of this order. A similar inconsistency was observed in prior phylogenetic analysis where Hanseniaspora mtDNAs clustered with the order Serinales (Christinaki et al., 2022). The uncertainty in the placement of the fast-evolving lineage of Hanseniaspora is likely due to long branch attraction (Bergsten, 2005). Thus, in Figure 3, we have displayed results from a tree-building run that recovered the order Saccharomycodales as monophyletic, as expected from the genome-scale nuclear phylogeny (Shen et al., 2018). Within taxonomic orders, groupings of genera were highly congruent with the genome-wide species phylogeny, but some inconsistencies remained in the placements of genera. For example, Eremothecium mtDNAs appeared as an outgroup to other Saccharomycetales, rather than grouping with Kluyveromyces and Lachancea as expected. Overall, we conclude that the observed mtDNA phylogeny generally tracked the species phylogeny and was not consistent with widespread introgressions or horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of protein-coding genes across long evolutionary distances.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial Phylogeny of 353 Budding Yeasts.

A phylogenetic tree was built from the protein sequences of the core protein-coding genes shared by all 353 budding yeast species analyzed (COX1, COX2, COX3, ATP6, ATP8, ATP9, and COB). Branches are colored based on taxonomic order.

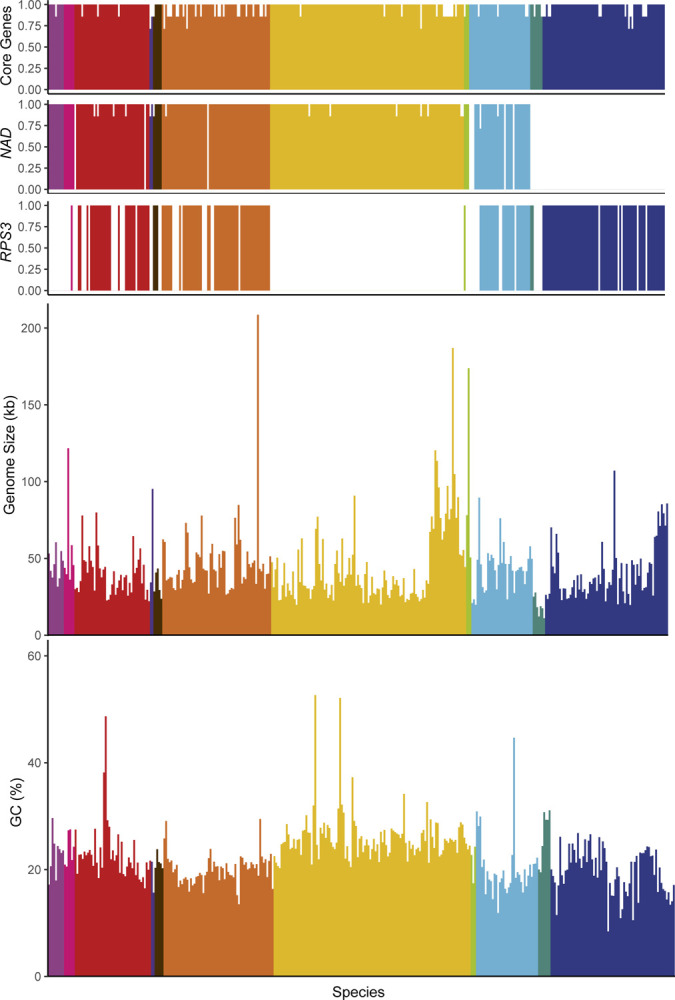

Analysis of mitochondrial genome content suggested that all mtDNAs likely retain the complete set of core respiratory genes, including: the Complex IV components encoded by COX1, COX2, and COX3; the complex III component encoded by COB; and the ATP synthase components encoded by ATP6, ATP8, and ATP9 (Figure 4A). The absence of some of these genes from a small number of assemblies was generally due to the assembly being fragmented or the annotation being manually removed due to issues with gene annotation (see Methods). In contrast, the mitochondrially-encoded components of the canonical Complex I (encoded by NAD1-NAD6 and NAD4L) were surprisingly absent in several mtDNAs that otherwise appeared to be complete (Figure 4B). These genes are generally present in the mtDNAs of most fungi (Sandor et al., 2018) but were known to be absent in the orders Saccharomycetales and Saccharomycodales (Freel et al., 2015; Christinaki et al., 2022); indeed, our analysis is consistent with a major loss event in the common ancestor of these lineages. However, we also observed a single species lacking these genes in the order Dipodascales, Nadsonia fulvescens var. fulvescens, which is consistent with their absence in the related species Nadsonia starkeyi-henricii (O’Boyle et al., 2018) that was not included in this dataset, as well as a novel single-species loss event in the order Pichiales for Ogataea philodendra. More strikingly, there were multiple independent losses within the order Phaffomycetales, including a single loss in the ancestor of Candida ponderosae, Starmera amethionina, and Candida stellimalicola, as well as potentially independent losses for Wickerhamomyces pijperi and Cyberlindnera petersonii. The distribution of the ribosomal protein encoded by RPS3 was extremely patchy (Figure 4C). RPS3 was not universally present in any taxonomic order, but all species in the dataset from the orders Serinales, Lipomycetales, and Sporopachydermiales lacked this gene.

Figure 4.

Genome Characteristics.

Genome characteristics are displayed and colored according to taxonomic order and placed based on position in the phylogenetic tree (left to right from Lipomycetales to Saccharomycetales, see Figure 3). The proportion of genes found in each genome are shown for: A) core genes (COX1, COX2, COX3, ATP6, ATP8, ATP9, and COB), B) Complex I genes (NAD1-NAD6, and NAD4L), and C) the RPS3 gene encoding a ribosomal protein. Genome sizes (D) and GC content (E) are indicated; both maintain a fairly limited range across the subphylum with a handful of extremes present across multiple taxonomic orders.

Despite similarities in gene content, genome size varied wildly at the extremes. Pichia heedii exceeded the previously largest observed Saccharomycotina mtDNA at 209,444 bp (versus the previous record of 187,024 bp in Metschnikowia arizonensis (Lee et al., 2020)), while the smallest observed mtDNA was Hanseniaspora pseudoguilliermondii at 11,080 bp (versus the previous record of 18.8 kb in Hanseniaspora uvarum (Pramateftaki et al., 2006)) (Figure 4D). The precise sizes of some mtDNAs were difficult to assess because not all assemblies were strictly complete, and short reads were not always capable of resolving genome structure reliably. The mtDNAs over 100 kb were typically more than double the size of any closely related species. Despite these observed extremes, the genome size of most species stayed within a range from approximately 20kb to 80kb (median size 39 kb, mean size 44 kb, standard deviation 23 kb). While this size variation is considerable in comparison with animal mtDNAs (Santamaria et al., 2007), it is within the ranges observed for other fungal mtDNAs (Sandor et al., 2018) and relatively low compared to plant mtDNAs (Gualberto and Newton, 2017).

The majority of species had similar GC content with a small number of outliers (Figure 4E). The average GC content was low (mean GC 22.5%, standard deviation 5.2%). Unusually high GC contents were sporadically placed around the phylogeny, including Candida subhashii (52.7%) and Candida gigantensis (52.1%) in the order Serinales, Magnusiomyces tetraspermus (48.7%) in the order Dipodascales, and Wickerhamomyces hampshirensis (44.7%) in the order Phaffomycetales. The lowest value observed was for Tetrapisispora blattae at 8.4% (order Saccharomycetales), which was close to lowest value of 7.6% previously observed in Saccharomycodes ludwigii (Nguyen et al., 2020a), which was not included in this dataset. Expansions of AT-rich intergenic regions have previously been reported to drive increases in genome size, which could drive a correlation between genome size and GC content. We found that, while this trend may be true in some groups, the overall correlation between genome size and GC content was poor and not significant after phylogenetic correction (r=−0.11, p-value 0.03; phylogenetically corrected r=−0.47, p-value 0.1, Supplemental Figure 2). Among the genomes over 100kb, the average GC content (22.8%) was close to the global average. Nakaseomyces bacillisporus may have driven prior correlations within smaller scale analyses of the order Saccharomycetales (Xiao et al., 2017) due its unusually large size (107 kb) and low GC content (10. 9%), but this relationship does not appear to be strong across the expanded dataset. If expansions of intergenic regions drive size variation between distant species (Hao, 2022), then they likely do so in a GC-independent manner.

2.3. Aerobic Fermenters Lack Evidence for Relaxed Purifying Selection

Metabolic strategies vary greatly among yeasts with regards to fermentation and respiration, which has been proposed to impact selection pressures on mitochondrial genes (Jiang et al., 2008). While many yeasts strongly respire fermentable carbon sources, such as glucose, there are many specialized yeasts, including most famously S. cerevisiae, that have developed metabolic strategies to preferentially ferment glucose and repress respiration, even in aerobic conditions (Merico et al., 2007; Rozpędowska et al., 2011; Hagman et al., 2013; Dashko et al., 2014; Hagman and Piškur, 2015). These aggressive fermenters are commonly said to exhibit Crabtree/Warburg Effect and are referred to as Crabtree/Warburg-positive (Diaz-Ruiz et al., 2011; Pfeiffer and Morley, 2014; Hammad et al., 2016). Given the relative disuse of respiration by this lifestyle, we hypothesized that the mitochondrially-encoded genes of Crabtree/Warburg-positive groups would exhibit elevated rates of non-synonymous substitutions due to relaxed purifying selection. Prior analysis of a limited set of species in the order Saccharomycetales had supported this model (Jiang et al., 2008).

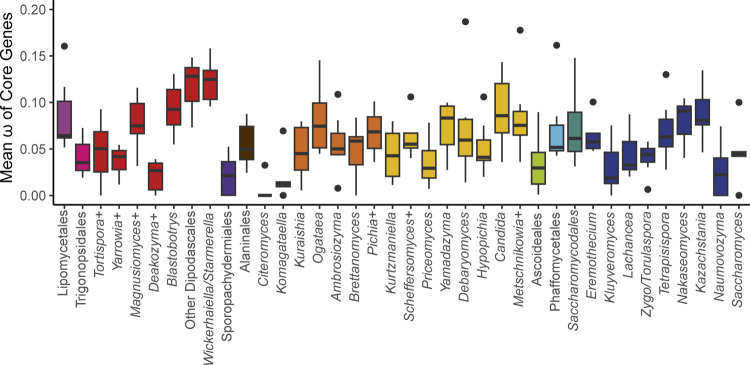

To test the generality of this hypothesis, we determined the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates (ω) among groups at roughly the genus level (see Methods) across the phylogeny (Figure 5, Supplemental Table 2). We expected that ω would be highest in Saccharomyces and in related yeasts in the order Saccharomycetales that had undergone a whole-genome duplication (Marcet-Houben and Gabaldón, 2015; Wolfe, 2015) and were known to be strong fermenters, such as Kazachstania and Nakaseomyces (Hagman et al., 2013). Surprisingly, we observed that ω varied greatly within taxonomic orders, with many groups exceeding the values observed for Saccharomyces. Indeed, the highest values were found in the order Dipodascales for yeasts in the Wickerhamiella/Starmerella clade and the grouping of yeasts most closely related to that clade (referred to as “Other Dipodascales” in Figure 5). The observed values for this clade are unlikely to be an artifact caused solely by long branch-lengths because the genus with the longest branch-lengths in the phylogeny (Hanseniaspora in the order Saccharomycodales) exhibited relatively moderate values. Within the order Saccharomycetales, we observed a general trend towards higher ω among yeasts that underwent the whole-genome duplication. The genus Saccharomyces followed this trend to some extent (genus mean ω 0.09 versus global mean 0.061), but this result was primarily driven by a single gene, ATP8, which had the highest value observed for all genes and groups and was driven by high values on the branches leading to S. paradoxus and S. arboricola (0.355). When this gene was excluded, the remaining genes defied the trend (0.046). ATP8 is highly conserved between S. cerevisiae strains (Wolters et al., 2015), which suggests inter- and intra-specific patterns of variation can differ greatly. Given the high ω values for many yeasts not known to be Crabtree/Warburg-positive and the relatively low ω for most Saccharomyces genes, we conclude that our much-expanded dataset does not support the previously proposed model of pervasive relaxed purifying selection on the mitochondrially-encoded genes of aerobic fermenters.

Figure 5.

Mean ω of Core Genes.

The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates for each of the core protein-coding genes was calculated for groups across the phylogeny (+ indicates that additional closely related species that are not currently classified in that genus were included, see Table S1). The box and whisker plots show the distribution of ω among genes within each group (boxes centered at median encompassing the interquartile range, whiskers up to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and outlier genes shown as individual datapoints). Two extreme outlier genes were omitted from the graph: ATP8 for Saccharomyces (0.355) and COB for Kurtzmaniella (0.250). Groups with aerobic fermenters, such as Saccharomyces, Kazachstania, and Nakaseomyces, do not exhibit significantly elevated ratios relative to the rest of the subphylum.

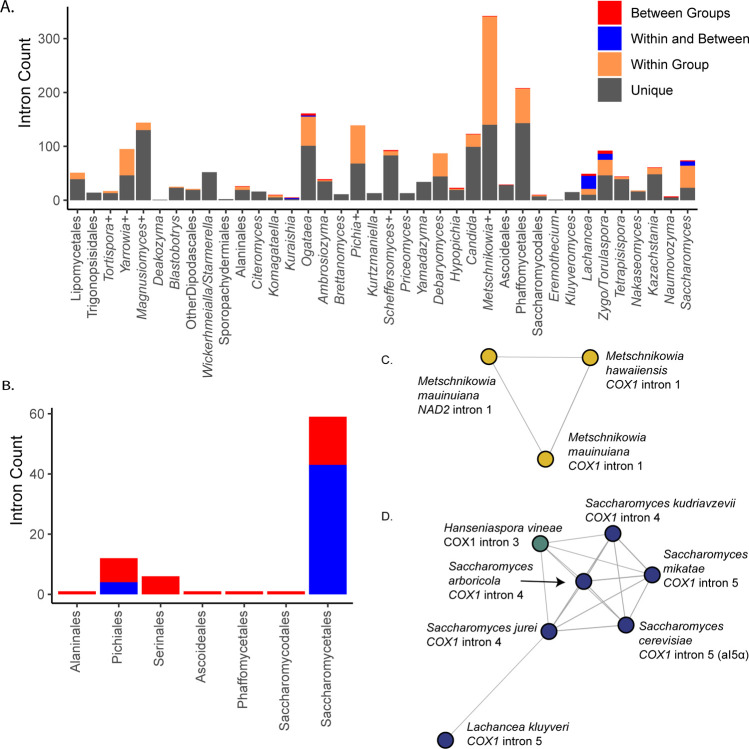

2.4. Evidence for Horizontal Transfer of Mitochondrial Introns Across Orders

Mitochondrial introns vary widely in yeasts, largely due to sporadic gains and losses (Xiao et al., 2017). Intron-encoded homing endonucleases are thought to drive intron turnover and potentially HGT of introns between species (Lang et al., 2007; Wu and Hao, 2014). The highest numbers of introns were observed in Magnusiomyces (mean 18 introns per species versus global mean 5.4 Supplemental Table 3), Metschnikowia (10.7), and Yarrowia (10.5, including other closely related anamorphic species that have yet to be reassigned to this genus). The lowest values were observed in Eremothecium (0.33) and Deakozyma (0.5), both of which included species that were completely free of introns. Nearly all introns were encoded within COX1 (55.3%), COB (30.1%), or NAD5 (7.4%); the remaining genes had <2% each. The small range of gene targets is consistent with intron homing by endonucleases transferring introns, including by HGT, to a limited range of target sites.

We identified potential intron HGTs based on BLAST comparisons of all mitochondrial introns observed using a conservative threshold to classify introns as unique, shared within a group (identical groupings as for the selection analysis above), shared within and between groups, or solely between groups (>50% of maximum possible bit score, Figure 6A). Most introns observed did not share high sequence similarity to introns from other species (65.6%), while most of the remainder were shared within a group (30%). A small number were shared across groups, and this phenomenon was especially common in the order Saccharomycetales (Figure 6B). Clustering the introns based on pairwise BLAST hits generated 271 clusters of related introns (Supplemental Table 3). Only a single cluster contained introns that were found within different genes due to homology between Metschnikowia mauinuiana NAD2 intron 1 and COX1 intron 1 from the same species and from Metschnikowia hawaiiensis (Figure 6C). NAD2 is duplicated in Metschnikowia mauinuiana, but only one copy has been colonized by this intron; however, the second copy contains a 560-bp duplication identical to the 3’ end the intron. Thus, M. mauinuiana NAD2 intron 1 may be misannotated and may instead be a 3’ terminal element that could be translated as an extension of the upstream gene; a similar phenomenon has been observed for COX2 and other genes in Saccharomyces (Peris et al., 2017). M. mauinuiana COX1 intron 1 had homology to the reverse transcriptase encoded in intron 1 of S. cerevisiae COX1; however, M. mauinuiana NAD2 intron 1 appeared to be truncated, which disrupts the intronic open reading frame. Thus, M. mauinuiana NAD2 intron 1 may better be thought of as an example of how a 3’ terminal element may be formed by an intronic mobile element acquiring a novel insertion site. The high number of introns in these species may be increasing the odds of such events in this genus, which has been speculated to have the strangest mitochondrial genomes (Lee et al., 2020).

Figure 6.

Intron Diversity.

A) Introns were classified based on pairwise BLAST hits as unique to that species, present in multiple species of the group, shared within and between groups, or only between groups. The counts of introns in each category within each group are displayed. B) The counts of introns in each taxonomic order that were shared or found only between groups are displayed. Orders not listed had no introns in these categories. C) Introns were clustered based on shared BLAST hits, and the single cluster containing hits shared across multiple genes is displayed. Nodes are colored based on taxonomic order as in Figure 2 (all Serinales). D) A cluster of introns is displayed that spans the orders Saccharomycetales and Saccharomycodales, including Saccharomyces spp., Lachancea kluyveri, and Hanseniaspora vineae. Nodes are colored based on taxonomic order as in Figure 3.

We observed 22 clusters that contained introns spanning multiple groups, including four that contained introns spanning multiple orders (Figure 6D, Supplemental Figure 3); these clusters are the top candidates for HGT events in our dataset. For example, the fifth intron of COX1 from S. cerevisiae (sometimes referred to as aI5α) shared homology with several Saccharomyces COX1 introns, as well as Hanseniaspora vineae COX1 intron 3 (Figure 6D). This cluster of introns may also include Lachancea kluyveri COX1 intron 5, but this connection was only supported for Saccharomyces jurei COX1 intron 4 (Figure 6D). All other H. vineae COX1 introns (order Saccharomycodales) shared limited homology to introns within the order Saccharomycetales, but it was well below our cutoff; since they shared no clear homology to other Hanseniaspora introns, these are also candidates for HGT, albeit more tentative ones. Two of the four clusters with evidence of cross-order HGT involved introns from Hypophichia burtonii, which suggests that this species may contain several highly active intronic mobile elements. Interestingly, this lineage also appears to have been an HGT donor of nuclear-encoded genes for utilization of the sugar galactose (Haase et al., 2021). We conclude that homology in homing endonuclease target sites likely enables the HGT of these selfish elements, even across large phylogenetic distances, at least in rare cases.

3. Discussion

As high-throughput sequencing revolutionized genomics, advances in yeast mitochondrial genomics were initially delayed. Early high-throughput datasets generated only partial sequences, potentially due to biases against AT-rich sequences (Chen et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2013). Advances in methodology led to large numbers of S. cerevisiae mitochondrial genomes being sequenced in tandem with their nuclear genomes (Strope et al., 2015). More recently, even very large population datasets produced mitochondrial genomes concurrently with the nuclear genomes (De Chiara et al., 2020). Prior to this study, these advances had not yet come to bear for large species-rich datasets, with targeted post-hoc searches of published assemblies yielding limited numbers of additional mtDNAs (Christinaki et al., 2022). Here, we have demonstrated that, even for short-read-only datasets, it is possible to extract high-quality mitochondrial genomes with a high success rate from datasets originally collected for nuclear sequencing. As yeast genomics progresses further, the mitochondrial component need not be an afterthought.

Despite these advances, limitations remain. Mitochondrial genome structure is complex and not always readily solvable through short reads alone. For example, the S. cerevisiae mtDNA maps genetically as circular, but the predominant molecular form is a linear concatemer of multiple genome units (Solieri, 2010). Other species exhibit true linear forms, including C. albicans (Gerhold et al., 2010), or even have capping terminal inverted repeats as seen in H. uvarum (Pramateftaki et al., 2006). Long-read sequencing technologies are a promising avenue to obtain not only complete mtDNAs, which short reads alone failed to provide for many species, but also to resolve complex genome structures by generating reads longer than a single genome unit in length. This strategy has already been successful at investigating large-scale deletion mutations in S. cerevisiae (Nunn and Goyal, 2022). However, specialized assemblers, similar in principle to those used here for reassembly of the short reads, will be needed because current long-read assemblers, such as canu (Koren et al., 2017), frequently misassemble circular-mapping genomes (Wick and Holt, 2019).

The most striking variation seen among the mtDNAs is the complete loss of canonical Complex I in Saccharomycetales, Saccharomycodales, and several additional lineages across the phylogeny. In S. cerevisiae, the acquisition of genes encoding a multi-unit alternative NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase facilitated this loss (Luttik et al., 1998; Kerscher, 2000), albeit at the cost of a loss in potential proton motive force. The mechanisms that allowed for this loss in the other independent events are currently unclear, but they suggest that multiple species may also have potentiating factors that could facilitate loss. Canonical Complex I is encoded by both nuclear and mitochondrial genes, but these nuclear genes were concomitantly lost in S. cerevisiae with the mitochondrial genes. If the same pattern persists across all independent loss events, then it may be possible to identify unknown genes related to Complex I that were also lost in tandem.

Originally, we hypothesized that preference for aerobic fermentation would be a major factor driving mitochondrial genome variation. Previously, it had even been hypothesized to play a significant role in the loss of Complex I as Brettanomyces species were the only others known to be Crabtree/Warburg-positive but still encode a canonical Complex I (Freel et al., 2015). Given that multiple losses of Complex I were observed in species not known to be Crabtree/Warburg-positive and given the lack of evidence for relaxed purifying selection in aerobic fermenters, it is not evident that this shift in metabolism is a major driver of mitochondrial gene evolution. An important caveat is that the methodology employed here may be limited by current datasets on the distribution of aerobic fermentation, which extrapolate from only a handful of well-characterized species. For example, the Wickerhamiella/Starmerella clade merits further attention due to the high rates of non-synonymous variation observed and potential environmental preferences for sugar-rich environments in this group (Gonçalves et al., 2020). Additionally, estimating selection at the group level may obscure patterns of selection that vary more between closely related species than between groups, as previously observed for Lachancea species (Freel et al., 2014). Focusing on selection pressures at the level of individual genes may also be more illuminating. The ω rates varied more for comparisons for the same gene across groups (mean variance 0.0018) than for comparisons of different genes within groups (0.0014). For example, while ATP9 is the most conserved gene within Saccharomyces, it is the least conserved in Nakaseomyces. If aerobic fermentation does play a role, it may relax selective pressure on some genes but increase purifying selection for others.

Mitochondrial introns may also serve an important role in shaping mitochondrial gene evolution. Homing endonucleases, which are encoded within mitochondrial introns or in downstream open reading frames at the 3’ end of mitochondrial genes, have been shown to modify sequences adjacent to the insertion site (Repar and Warnecke, 2017; Xiao et al., 2017; Wu and Hao, 2019). Transfers between groups, and potentially between orders, may introduce non-synonymous variation due to co-conversion of flanking sequences during insertion. We observed a large proportion of unique introns in our dataset, which is consistent with high rates of intron turnover underlying presence/absence variation. However, we have likely underestimated the true proportion of introns shared within groups due to the stringent criteria applied and the rapid decay of detectable sequence homology due to high mtDNA mutation rates (Sharp et al., 2018). Mitochondrial introns have been known to jump between different kingdoms between the symbiotic components of lichens (Mukhopadhyay and Hausner, 2021). Certain ecological conditions, such as coculture of Saccharomyces and Hanseniaspora during wine fermentation (Langenberg et al., 2017), may similarly facilitate horizontal transfer.

The mitochondrial genomes generated in this study provide many opportunities to further our understanding of evolution beyond the scope of this study. Pairing the data with the previously generated nuclear genomes will help elucidate the interplay between these two genomes. Interactions between mitochondrial and nuclear loci (mito-nuclear epistasis) have been demonstrated to affect phenotypic variation in yeasts (Paliwal et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2020b, 2023; Visinoni and Delneri, 2022; Biot-Pelletier et al., 2023) and a diverse array of model systems (Dowling et al., 2007; Burton and Barreto, 2012; Mossman et al., 2016). For many existing mitochondrial genomes, any analysis of such interactions was previously often complicated by the lack of a corresponding nuclear genome or by mismatches between the strains sequenced for a given species. By mining most of this new mtDNA dataset from a dataset of high-quality nuclear genomes (Shen et al., 2018), many of these previous limitations have been lifted, which has already enabled the novel insights described here. The breadth and the richness of these paired nuclear-mitochondrial datasets promise to greatly accelerate research into the evolution of yeast mitochondrial genomes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mitochondrial Genome Rescue, Assembly, and Annotation

We searched 332 yeast genome assemblies for mitochondrial contigs using a two-pronged, reference-based approach (Shen et al., 2018). First, we curated a set of reference mtDNAs from all accessions in Genbank matching Saccharomycotina and with the source as “mitochondrion” in September 2018 to generate a set of 110 published mtDNAs with a single representative per species (Supplemental Table 1). Existing annotations were curated based on length and presence of stop codons, and they were renamed for consistent formatting. When annotations were not available, new annotations were generated using MFANNOT (Lang et al., 2007). We identified putative mitochondrial contigs based on two BLAST strategies searches (v2.8.1). First, the coding sequences (CDS) from the curated references were used as queries to search each assembly, and contigs with at least 10 hits >70% coverage and e-value <0.001 were retained. Second, the contigs from each assembly were used as queries against the complete reference mtDNAs, and contigs with at least one 25% coverage hit with e-value <0.001 were retained. These contigs were then preliminarily annotated using MFANNOT (Lang et al., 2007) to estimate gene content (Lang et al., 2007). To eliminate contigs that were likely short duplicates of mitochondrial sequences transferred to the nuclear genome, also known as NUMTs (Hazkani-Covo et al., 2010; Xue et al., 2023), we filtered out contigs that did not possess at least one mitochondrial gene per 20 kb. Contigs larger than 300kb were also removed to eliminate any complete mtDNA duplicates in large nuclear contigs.

Assembly methods for nuclear genomes are generally not optimized for mitochondrial sequences, so we reassembled genomes for which sequencing reads were readily available, including 196 species sequenced in Shen et al. 2018 and 92 additional species included in that dataset that we resequenced to replace an older nuclear assembly as part of the Y1000+ Project (Supplemental Table 1) (Opulente et al., 2023). Reassembly was done using either plasmidSPAdes v3.9.0 (Antipov et al., 2016) or NOVOPlasty v4.2 (Dierckxsens et al., 2017). We annotated these assemblies using MFANNOT (Lang et al., 2007) and then searched for mitochondrial contigs as described above. For NOVOPlasty, multiple assemblies were constructed using different seeds either using the genes found in the putative mitochondrial contigs extracted from the nuclear assembly or the CDS from the closest available genome based on the nuclear phylogeny in the curated reference set. The putative mitochondrial contigs isolated from the nuclear assembly and the mitochondrial reassemblies were assessed based on completeness (% of expected genes present, excluding RPS3 and Complex I genes when none were present), contiguity (% of genes found on each contig), and circularity (count of reads that map across the contig endpoints after shifting the sequence such that the original breakpoint is internal in the permuted contig), and a single assembly was chosen for each species. We prioritized completeness and used contiguity and circularity to break ties. Generally, NOVOPlasty performed best, followed by plasmidSPAdes, while the existing contigs from the nuclear assembly were best in a small minority of cases. For the final dataset, we combined these assemblies with the curated reference set, retaining one assembly per species and choosing the reference assembly for a species when available.

All new assemblies, as well as existing mtDNAs that were not annotated, were annotated from scratch; all genome annotations, including published ones, were curated for consistency and to improve accuracy as described below. The translation table for each species was estimated using codetta v2.0 (Shulgina and Eddy, 2021). Yeast mitochondrial translation tables fall into either the Mold, Protozoan, and Coelenterate Mitochondrial Code and the Mycoplasma/Spiroplasma Code (NCBI table 4, hereafter referred to as the fungal code), which is consistent with other fungi, or the yeast mitochondrial code (NCBI table 3, originally based on S. cerevisiae, hereafter referred to as the Saccharomyces code) based on additional reassignments of AUA and CUN codons, which typically define the order Saccharomycetales. The exact placement of this transition was difficult to determine due to a loss of CUN codons in many Saccharomycetales, particularly Kluyveromyces species and other closely related genera. In many species, the CUN reassignment is supported by codetta, but the AUA reassignment is not, and the modified tRNA required for this reassignment is not present, which is consistent with a previous analysis of codon usage among Saccharomycotina mtDNAs (Christinaki et al., 2022). Currently, no translation table exists for the CUN reassignment without the AUA reassignments, so we used the Saccharomyces code when the CUN reassignment was supported and the fungal code for all others (Table S1). The AUA reassignment in the Saccharomyces code allows for this codon to be treated as a start codon by MFANNOT, which resulted in many misannotations at the 5’ end of genes. No examples of AUA being used as a valid start codon in yeasts have been described. We rectified this issue by reannotating all assemblies using table 4 to define start and end coordinates; we then used the Saccharomyces code for translation when appropriate. Finally, all annotations (for new and existing mtDNAs) were further manually curated to eliminate truncated genes, annotations split across contigs, and annotations containing large extensions due to misannotated introns or readthroughs. We identified several Kazachstania species with frameshifts consistent with the +1C frameshift mechanism previously described (Szabóová et al., 2018). To match the formatting in GenBank for those references, we encoded these as single-bp introns, but these were excluded from all intron analyses. We did not observe any byp elements, as described in Magnusiomyces tetraspermus, in the coding sequences of other species (Lang et al., 2014).

4.2. Mitochondrial Phylogeny Construction

We determined phylogenetic relationships among mitochondrial genomes based on the core set of genes shared by all species: COX1, COX2, COX3, COB, ATP6, ATP8, and ATP9. Complex I genes were excluded due their loss in a large fraction of the species. Protein sequences were aligned for each gene using MAFFT using the E-INS-I option (Katoh and Standley, 2013), and CDS were codon-aligned using the protein alignment. The alignments were concatenated and then filtered to retain only sites in which 95% of sequences were not gaps using trimAl (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009). We built multiple phylogenies from the filtered alignment using IQ-TREE using the mitochondrial substitution model (Minh et al., 2020). These phylogenies were highly concordant, except for the placement of the fast-evolving Hanseniaspora lineage. The topology most consistent with the nuclear phylogeny was selected as the final tree. Phylogenetic correction of correlations of genome size versus GC content were done using a generalized least squares approach (using gls from nlme (Pinheiro J, Bates D, 2023)) using a co-variation matrix generated using a Brownian motion model (using corPagel from ape (Paradis and Schliep, 2019)).

4.3. Estimating Patterns of Selection

To investigate patterns of selection on mitochondrial genes, we split the phylogeny into smaller groups at roughly the genus level to avoid saturation of synonymous substitutions (Table 1). For each of the genes in the core set, we built subtrees for each group and estimated ω along each branch of the subtree using PAML under model 1 (allowing variable ω for each branch) (Yang, 2007). For each gene, the ω value was determined as the mean of the values for all branches in the subtree for which there were sufficient synonymous substitutions (dS > 0.01).

4.4. Evaluating Evidence for Horizontal Transfer of Mitochondrial Introns

Possible HGTs of mitochondrial introns were determined based on an all-versus-all BLAST of mitochondrial introns against each other. Mitochondrial introns among closely related species are expected to share limited sequence similarity due to poor conservation of non-coding sequences, though elements that contribute to intron splicing may be under purifying selection. Thus, we set a conservative threshold that the bit score of each hit must be at least 50% of the maximum possible bit score determined by the self-to-self comparison of each intron and have an e-value < 10−10. Shared relationships within groups are likely to be due to vertical descent, although there is evidence that HGT frequently occurs at this scale (Wu and Hao, 2014), but such high sequence similarity at large phylogenetic distances is likely due to HGT. Clustering of intron sequences was performed using the Louvain method (Blondel et al., 2008) implemented in the igraph (Csárdi et al., 2023) package of R.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Mitochondrial Genome Quality.

The completeness (proportion of expected genes present on the best contig, excluding RPS3, and excluding NAD genes when none were present in the assembly) and contiguity (proportion of genes found present on the best contig) of putative mitochondrial contigs are shown for A) public genome assemblies included in (Shen et al., 2018), B) newly sequenced genome assemblies included in (Shen et al., 2018), and C) our final mitochondrial genome dataset. Genomes with high completeness but lower contiguity were typically well represented by only two contigs.

Supplemental Figure 2. Genome size versus GC Content.

The correlation between genome size and GC content is indicated with individual genomes labeled by taxonomic order as in Figure 3. Larger genomes tended to have lower GC content, but the correlation was only weakly significant. Phylogenetic correction increased the strength of the correlation, but it was no longer statistically significant. GC content does not appear to play a central role in influencing genome size.

Supplemental Figure 3. Candidates for Intron HGT across Taxonomic Orders.

Intron sequences were compared using BLAST, and scores were used to generate clusters of closely related introns. Four clusters showed high homology between introns from different taxonomic orders; three are displayed here, while the fourth one is in Figure 6C. Introns are labeled by taxonomic order as in Figure 3.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacob L. Steenwyk, Xiaofan Zhou, Trey K. Sato, Hittinger Lab members, and Y1000+ Project members for helpful comments; the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center DNA Sequencing Facility (Research Resource Identifier – RRID:SCR_017759) for providing DNA sequencing facilities and services; Wisconsin Energy Institute staff for computational support; and the Center for High-Throughput Computing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (https://doi.org/10.21231/GNT1-HW21).

Funding

This work was supported by postdoctoral fellowships or traineeships awarded to JFW from the National Institutes of Health Grant T32 HG002760-16 and the National Science Foundation Grant Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology 1907278. Research in the Hittinger Lab is supported by the National Science Foundation (grants DEB-2110403), by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch Project 1020204), in part by the DOE Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE BER Office of Science DE-SC0018409, and by an H. I. Romnes Faculty Fellowship (Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation). Research in the Rokas lab is supported by the National Science Foundation (DEB-2110404), by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI153356), and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by postdoctoral fellowships or traineeships awarded to JFW from the National Institutes of Health Grant T32 HG002760-16 and the National Science Foundation Grant Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology 1907278. Research in the Hittinger Lab is supported by the National Science Foundation (grants DEB-2110403), by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch Project 1020204), in part by the DOE Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE BER Office of Science DE-SC0018409, and by an H. I. Romnes Faculty Fellowship (Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation). Research in the Rokas lab is supported by the National Science Foundation (DEB-2110404), by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI153356), and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

AR is a scientific consultant for LifeMine Therapeutics, Inc. The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material should be uploaded separately on submission, if there are Supplementary Figures, please include the caption in the same file as the figure. Supplementary Material templates can be found in the Frontiers Word Templates file.

Please see the Supplementary Material section of the Author guidelines for details on the different file types accepted.

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data and analyses are available at https://figshare.com/s/9266509ee3a167725b5f. This link will be replaced with a public link on acceptance.

References

- Adams K. L., and Palmer J. D. (2003). Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: Gene loss and transfer to the nucleus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 380–395. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antipov D., Hartwick N., Shen M., Raiko M., Lapidus A., and Pevzner P. A. (2016). PlasmidSPAdes: Assembling plasmids from whole genome sequencing data. Bioinformatics 32, 3380–3387. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten J. (2005). A review of long-branch attraction. Cladistics 21, 163–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2005.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biot-Pelletier D., Bettinazzi S., Gagnon-Arsenault I., Dubé A. K., Bédard C., Nguyen T. H. M., et al. (2023). Evolutionary Trajectories are Contingent on Mitonuclear Interactions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 40, 1–16. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msad061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel V. D., Guillaume J. L., Lambiotte R., and Lefebvre E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton R. S., and Barreto F. S. (2012). A disproportionate role for mtDNA in Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities? Mol. Ecol. 21, 4942–57. doi: 10.1111/mec.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G., Rasmussen M. D., Lin M. F., Santos M. A. S., Sakthikumar S., Munro C. A., et al. (2009). Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature 459, 657–662. doi: 10.1038/nature08064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez S., Silla-Martínez J. M., and Gabaldón T. (2009). trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-C., Liu T., Yu C.-H., Chiang T.-Y., and Hwang C.-C. (2013). Effects of GC Bias in Next-Generation-Sequencing Data on De Novo Genome Assembly. PLoS One 8, e62856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christinaki A. C., Kanellopoulos S. G., Kortsinoglou A. M., Andrikopoulos M., Theelen B., Boekhout T., et al. (2022). Mitogenomics and mitochondrial gene phylogeny decipher the evolution of Saccharomycotina yeasts. Genome Biol. Evol. 14, 1–19. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evac073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csárdi G., Nepusz T., Müller K., Horvát S., Traag V., Zanini F., et al. (2023). igraph for R: R interface of the igraph library for graph theory and network analysis. Available at: https://zenodo.org/record/8046777. [Google Scholar]

- Dashko S., Zhou N., Compagno C., and Piskur J. (2014). Why, when, and how did yeast evolve alcoholic fermentation? FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 826–832. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Chiara M., Friedrich A., Barré B., Breitenbach M., Schacherer J., and Liti G. (2020). Discordant evolution of mitochondrial and nuclear yeast genomes at population level. BMC Biol. 18, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12915-020-00786-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Ruiz R., Rigoulet M., and Devin A. (2011). The Warburg and Crabtree effects: On the origin of cancer cell energy metabolism and of yeast glucose repression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1807, 568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierckxsens N., Mardulyn P., and Smits G. (2017). NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling D. K., Abiega K. C., and Arnqvist G. (2007). Temperature-specific outcomes of cytoplasmic-nuclear interactions on egg-to-adult development time in seed beetles. Evolution 61, 194–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling D. K., and Wolff J. N. (2023). Evolutionary genetics of the mitochondrial genome: insights from Drosophila. Genetics 224, 1–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/iyad036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foury F., Roganti T., Lecrenier N., and Purnelle B. (1998). The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 440, 325–31. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9872396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freel K. C., Friedrich A., Hou J., and Schacherer J. (2014). Population Genomic Analysis Reveals Highly Conserved Mitochondrial Genomes in the Yeast Species Lachancea thermotolerans. Genome Biol. Evol. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freel K. C., Friedrich A., and Schacherer J. (2015). Mitochondrial genome evolution in yeasts: An all-encompassing view. FEMS Yeast Res. 15, 1–9. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/fov023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhold J. M., Aun A., Sedman T., Jõers P., and Sedman J. (2010). Strand invasion structures in the inverted repeat of Candida albicans mitochondrial DNA reveal a role for homologous recombination in replication. Mol. Cell 39, 851–861. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves P., Gonçalves C., Brito P. H., and Sampaio J. P. (2020). The Wickerhamiella/Starmerella clade—A treasure trove for the study of the evolution of yeast metabolism. Yeast 37, 313–320. doi: 10.1002/yea.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald M., Hittinger C. T., Bensch K., Opulente D. A., Shen X.-X., Li Y., et al. (2023). A genome-informed higher rank classification of the biotechnologically important fungal subphylum Saccharomycotina. Stud. Mycol. 22, 1–22. doi: 10.3114/sim.2023.105.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualberto J. M., Mileshina D., Wallet C., Niazi A. K., Weber-Lotfi F., and Dietrich A. (2014). The plant mitochondrial genome: Dynamics and maintenance. Biochimie 100, 107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualberto J. M., and Newton K. J. (2017). Plant Mitochondrial Genomes: Dynamics and Mechanisms of Mutation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68, annurev-arplant-043015–112232. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase M. A. B., Kominek J., Opulente D. A., Shen X. X., LaBella A. L., Zhou X., et al. (2021). Repeated horizontal gene transfer of GALactose metabolism genes violates Dollo’s law of irreversible loss. Genetics 217. doi: 10.1093/GENETICS/IYAA012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman A., and Piškur J. (2015). A study on the fundamental mechanism and the evolutionary driving forces behind aerobic fermentation in yeast. PLoS One 10, 1–24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman A., Sall T., Compagno C., and Piskur J. (2013). Yeast “Make-Accumulate-Consume” Life Strategy Evolved as a Multi-Step Process That Predates the Whole Genome Duplication. PLoS One 8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammad N., Rosas-Lemus M., Uribe-Carvajal S., Rigoulet M., and Devin A. (2016). The Crabtree and Warburg effects: Do metabolite-induced regulations participate in their induction? Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1857, 1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao W. (2022). From Genome Variation to Molecular Mechanisms: What we Have Learned From Yeast Mitochondrial Genomes? Front. Microbiol. 13, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.806575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazkani-Covo E., Zeller R. M., and Martin W. (2010). Molecular poltergeists: Mitochondrial DNA copies (numts) in sequenced nuclear genomes. PLoS Genet. 6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittinger C. T. (2013). Saccharomyces diversity and evolution: A budding model genus. Trends Genet. 29, 309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittinger C. T., Rokas A., Bai F. Y., Boekhout T., Gonçalves P., Jeffries T. W., et al. (2015). Genomics and the making of yeast biodiversity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 35, 100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Guan W., Pinney D., Wang W., and Gu Z. (2008). Relaxation of yeast mitochondrial functions after whole-genome duplication. Genome Res. 18, 1466–1471. doi: 10.1101/gr.074674.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston I. G., and Williams B. P. (2016). Evolutionary inference across eukaryotes identifies specific pressures favoring mitochondrial gene retention. Cell Syst. 2, 101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., and Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher S. J. (2000). Diversity and origin of alternative NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1459, 274–283. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S., Walenz B. P., Berlin K., Miller J. R., Bergman N. H., and Phillippy A. M. (2017). Canu: Scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive κ-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang B. F., Jakubkova M., Hegedusova E., Daoud R., Forget L., Brejova B., et al. (2014). Massive programmed translational jumping in mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 5926–5931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322190111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang B. F., Laforest M.-J., and Burger G. (2007). Mitochondrial introns: a critical view. Trends Genet. 23, 119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenberg A. K., Bink F. J., Wolff L., Walter S., von Wallbrunn C., Grossmann M., et al. (2017). Glycolytic functions are conserved in the genome of the wine yeast Hanseniaspora uvarum, and pyruvate kinase limits its capacity for alcoholic fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, 1–20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01580-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. K., Hsiang T., Lachance M. A., and Smith D. R. (2020). The strange mitochondrial genomes of Metschnikowia yeasts. Curr. Biol. 30, R783–R801. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttik M. A. H., Overkamp K. M., Kötter P., De Vries S., Van Dijken J. P., and Pronk J. T. (1998). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae NDE1 and NDE2 genes encode separate mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenases catalyzing the oxidation of cytosolic NADH. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24529–24534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcet-Houben M., and Gabaldón T. (2015). Beyond the whole-genome duplication: Phylogenetic evidence for an ancient interspecies hybridization in the baker’s yeast lineage. PLoS Biol. 13, 1–26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merico A., Sulo P., Piškur J., and Compagno C. (2007). Fermentative lifestyle in yeasts belonging to the Saccharomyces complex. FEBS J. 274, 976–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh B. Q., Schmidt H. A., Chernomor O., Schrempf D., Woodhams M. D., Von Haeseler A., et al. (2020). IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman J. A., Biancani L. M., Zhu C. T., and Rand D. M. (2016). Mitonuclear epistasis for development time and its modification by diet in Drosophila. Genetics 203, 463–484. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.187286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay J., and Hausner G. (2021). Organellar introns in fungi, algae, and plants. Cells 10. doi: 10.3390/cells10082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Gómez S. A., Slamovits C. H., Dacks J. B., Baier K. A., Spencer K. D., and Wideman J. G. (2015). Ancient Homology of the Mitochondrial Contact Site and Cristae Organizing System Points to an Endosymbiotic Origin of Mitochondrial Cristae. Curr. Biol. 25, 1489–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D. T., Wu B., Xiao S., and Hao W. (2020a). Evolution of a record-setting at-rich genome: Indel mutation, recombination, and substitution bias. Genome Biol. Evol. 12, 2344–2354. doi: 10.1093/GBE/EVAA202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. H. M., Sondhi S., Ziesel A., Paliwal S., and Fiumera H. L. (2020b). Mitochondrial-nuclear coadaptation revealed through mtDNA replacements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Evol. Biol. 20, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12862-020-01685-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. H. M., Tinz-Burdick A., Lenhardt M., Geertz M., Ramirez F., Schwartz M., et al. (2023). Mapping mitonuclear epistasis using a novel recombinant yeast population. PLoS Genet. 19, 1–30. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1010401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn C. J., and Goyal S. (2022). Contingency and selection in mitochondrial genome dynamics. Elife 11, 1–46. doi: 10.7554/eLife.76557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle S., Bergin S. A., Hussey É. E., McLaughlin A. D., Riddell L. R., Byrne K. P., et al. (2018). Draft genome sequence of the yeast Nadsonia starkeyi-henricii UCD142, isolated from forest soil in Ireland. Genome Announc. 6, 1–2. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00549-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opulente D. A., LaBella A. L., Harrison M.-C., Wolters J. F., Liu C., Li Y., et al. (2023). Genomic and ecological factors shaping specialism and generalism across an entire subphylum. bioRxiv, 2023.06.19.545611. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.19.545611v1%0A https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.19.545611v1.abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Opulente D., Rollinson E., Bernick-Roehr C., Hulfachor A., Rokas A., Kurtzman C., et al. (2018). Factors driving metabolic diversity in the budding yeast subphylum. BMC Biol. 16. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0498-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal S., Fiumera A. C., and Fiumera H. L. (2014). Mitochondrial-Nuclear Epistasis Contributes to Phenotypic Variation and Coadaptation in Natural Isolates of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 198, 1251–1265. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.168575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E., and Schliep K. (2019). Ape 5.0: An environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris D., Arias A., Orlic S., Belloch C., Perez-Traves L., Querol A., et al. (2017). Mitochondrial introgression suggests extensive ancestral hybridization events among Saccharomyces species. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 108, 49–60. doi: 10.1101/028324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer T., and Morley A. (2014). An evolutionary perspective on the Crabtree effect. Front. Mol. Biosci. 1, 1–6. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2014.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, R. C. T. (2023). nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models.

- Pramateftaki P. V., Kouvelis V. N., Lanaridis P., and Typas M. A. (2006). The mitochondrial genome of the wine yeast Hanseniaspora uvarum: A unique genome organization among yeast/fungal counterparts. FEMS Yeast Res. 6, 77–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2005.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repar J., and Warnecke T. (2017). Mobile introns shape the genetic diversity of their host genes. Genetics 205, 1641–1648. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.199059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. G., Russ C., Costello M., Hollinger A., Lennon N. J., Hegarty R., et al. (2013). Characterizing and measuring bias in sequence data. Genome Biol. 14, R51. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-5-r51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozpędowska E., Hellborg L., Ishchuk O. P., Orhan F., Galafassi S., Merico A., et al. (2011). Parallel evolution of the make–accumulate–consume strategy in Saccharomyces and Dekkera yeasts. Nat. Commun. 2, 302. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandor S., Zhang Y., and Xu J. (2018). Fungal mitochondrial genomes and genetic polymorphisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 9433–9448. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria M., Lanave C., Vicario S., and Saccone C. (2007). Variability of the mitochondrial genome in mammals at the inter-species/intra-species boundary. Biol. Chem. 388, 943–946. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannell D. R., Zill O. a, Rokas A., Payen C., Dunham M. J., Eisen M. B., et al. (2011). The Awesome Power of Yeast Evolutionary Genetics: New Genome Sequences and Strain Resources for the Saccharomyces sensu stricto Genus. G3 (Bethesda). 1, 11–25. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp N. P., Sandell L., James C. G., and Otto S. P. (2018). The genome-wide rate and spectrum of spontaneous mutations differ between haploid and diploid yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, E5046–E5055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X.-X., Opulente D. A., Kominek J., Zhou X., Steenwyk J. L., Buh K. V., et al. (2018). Tempo and Mode of Genome Evolution in the Budding Yeast Subphylum. Cell 175, 1533–1545. doi: 10.1016/J.CELL.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulgina Y., and Eddy S. R. (2021). A computational screen for alternative genetic codes in over 250,000 genomes. Elife 10, 1–25. doi: 10.7554/eLife.71402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solieri L. (2010). Mitochondrial inheritance in budding yeasts: towards an integrated understanding. Trends Microbiol. 18, 521–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strope P. K., Skelly D. a, Kozmin S. G., Mahadevan G., Stone E. a, Magwene P. M., et al. (2015). The 100-genomes strains, a S. cerevisiae resource that illuminates its natural phenotypic and genotypic variation and emergence as an opportunistic pathogen. Genome Res. 25, 1–13. doi: 10.1101/gr.185538.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabóová D., Hapala I., and Sulo P. (2018). The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence from Kazachstania sinensis reveals a general +1C frameshift mechanism in CTGY codons. FEMS Yeast Res. 18, 1–10. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/foy028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visinoni F., and Delneri D. (2022). Mitonuclear interplay in yeast: from speciation to phenotypic adaptation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 76, 101957. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2022.101957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., and Holt K. E. (2019). Benchmarking of long-read assemblers for prokaryote whole genome sequencing. F1000Research 8, 1–22. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.21782.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe K. H. (2015). Origin of the yeast whole-genome duplication. PLoS Biol. 13, 1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters J. F., Chiu K., and Fiumera H. L. (2015). Population structure of mitochondrial genomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 16, 451. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1664-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., and Hao W. (2014). Horizontal transfer and gene conversion as an important driving force in shaping the landscape of mitochondrial introns. G3 (Bethesda). 4, 605–12. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.009910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., and Hao W. (2019). Mitochondrial-encoded endonucleases drive recombination of protein-coding genes in yeast. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 4233–4240. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S., Nguyen D. T., Wu B., and Hao W. (2017). Genetic drift and indel mutation in the evolution of yeast mitochondrial genome size. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 3088–3099. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L., Moreira J. D., Smith K. K., and Fetterman J. L. (2023). The Mighty NUMT: Mitochondrial DNA Flexing Its Code in the Nuclear Genome. Biomolecules 13, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/biom13050753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–91. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachar I., and Szathmáry E. (2017). Breath-giving cooperation: critical review of origin of mitochondria hypotheses. Biol. Direct 12, 19. doi: 10.1186/s13062-017-0190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Mitochondrial Genome Quality.

The completeness (proportion of expected genes present on the best contig, excluding RPS3, and excluding NAD genes when none were present in the assembly) and contiguity (proportion of genes found present on the best contig) of putative mitochondrial contigs are shown for A) public genome assemblies included in (Shen et al., 2018), B) newly sequenced genome assemblies included in (Shen et al., 2018), and C) our final mitochondrial genome dataset. Genomes with high completeness but lower contiguity were typically well represented by only two contigs.

Supplemental Figure 2. Genome size versus GC Content.

The correlation between genome size and GC content is indicated with individual genomes labeled by taxonomic order as in Figure 3. Larger genomes tended to have lower GC content, but the correlation was only weakly significant. Phylogenetic correction increased the strength of the correlation, but it was no longer statistically significant. GC content does not appear to play a central role in influencing genome size.

Supplemental Figure 3. Candidates for Intron HGT across Taxonomic Orders.

Intron sequences were compared using BLAST, and scores were used to generate clusters of closely related introns. Four clusters showed high homology between introns from different taxonomic orders; three are displayed here, while the fourth one is in Figure 6C. Introns are labeled by taxonomic order as in Figure 3.

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data and analyses are available at https://figshare.com/s/9266509ee3a167725b5f. This link will be replaced with a public link on acceptance.