Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the healthcare industry and its workforce, particularly nurses, who have been at the forefront of patient care. As the world begins to emerge from the pandemic, attention is turning to the long-term effects of the crisis on nurses’ mental health and well-being, and specifically nursing burnout. Prevalent risk factors related to nursing burnout often historically involve high workload, insufficient support and/or resources, work–life imbalance, and even lack of autonomy and organization climate challenges. Understanding the factors that contribute to nursing burnout to help mitigate it is vital to ensuring the ongoing health and well-being of the nursing workforce, especially since the ongoing waning of coronavirus (COVID-19). This rapid review identifies 36 articles and explores the latest research on nursing burnout in outpatient (ambulatory care) healthcare facilities as the global pandemic continues to subside, and therefore identifies constructs that suggest areas for future research beyond previously identified contributing factors of nursing burnout while the pandemic virus levels were high.

Keywords: nursing, burnout, workforce, COVID-19, coronavirus, ambulatory care, outpatient

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to the Problem

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 flipped the world of healthcare as we know it on its head. It took an already overworked, understaffed industry and added even more pressure with waning resources, absent administration, poor work–life balance, and an even bigger increase in the already high turnover rates. Nurse burnout refers to a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion that results from prolonged exposure to high levels of job-related stress, demanding work conditions, and a sense of depersonalization or cynicism towards one’s job. It is a complex and multi-dimensional phenomenon that can occur when nurses experience overwhelming feelings of being emotionally drained, depleted of energy, and unable to cope effectively with the demands of their work.

Prior to the pandemic, nurses were more willing to let the long-established problems with the healthcare industry slide, but with the pandemic exacerbating these issues, coupled with the extreme compassion fatigue and burnout that are being experienced, they are no longer staying quiet and sweeping them under the rug. This has led to nurses leaving the bedside and the industry in droves, increasing the extreme nursing shortage even more. Burnout can have serious consequences for both the well-being of the individual nurse and the quality of patient care provided. It can lead to increased absenteeism, higher turnover rates, decreased job satisfaction, and compromised patient safety and outcomes. Recognizing and addressing nurse burnout and related impacting risk and protective factors is crucial for promoting the well-being of nurses and ensuring the delivery of high-quality healthcare services. Implementing supportive strategies, providing resources, and creating a positive work environment can help mitigate the risk of nurse burnout and promote a healthier and more resilient nursing workforce.

1.2. Significance of This Study

Prior to 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic progressed in waves across countries as they worked to adapt to public health measures and developing treatment protocols. Throughout this whole period, professionals in the nursing field experienced continued burnout as a result of the pandemic. Multiple systematic literature reviews were conducted as COVID-19 surged across the globe and identified contributing factors, to include the following constructs:

Responsiveness of organizational reaction to virus surges [2];

Lack of identification methods of burnout among nursing teams during the provision of care [1];

Working environment, strength of staff members, and leadership effectiveness [3].

These prior review findings were from studies conducted in acute care (hospital) settings, the primary location for the treatment of COVID-19 patients during the initial and ongoing stages of the pandemic. In addition to identifying nursing burnout constructs, these prior reviews further identified and discussed potential long-term industry workforce implications, including quality of care and patient outcomes [4]. Now that the COVID-19 pandemic has subsided, with increasing vaccination rates and a return to routine care for healthcare facilities, our research team was interested in current nursing burnout contributors specific to outpatient (ambulatory care) healthcare organizations. Therefore, the aim of this study is to better identify the current and most recent nursing burnout factors in the outpatient/ambulatory care segment of the healthcare industry. Such information could support healthcare leadership’s efforts to combat ongoing burnout factors in the nursing workforce, while also staying attuned to underlying factors contributing to the issue in the routine care (non-acute) environment. While our review team recognizes that the decline of the COVID-19 virus and its virulence will vary across both time periods and locations (region), the intent of this study is to attempt to preempt any new or developing influences upon the ongoing burnout experienced in the industry’s nursing profession.

2. Materials and Methods

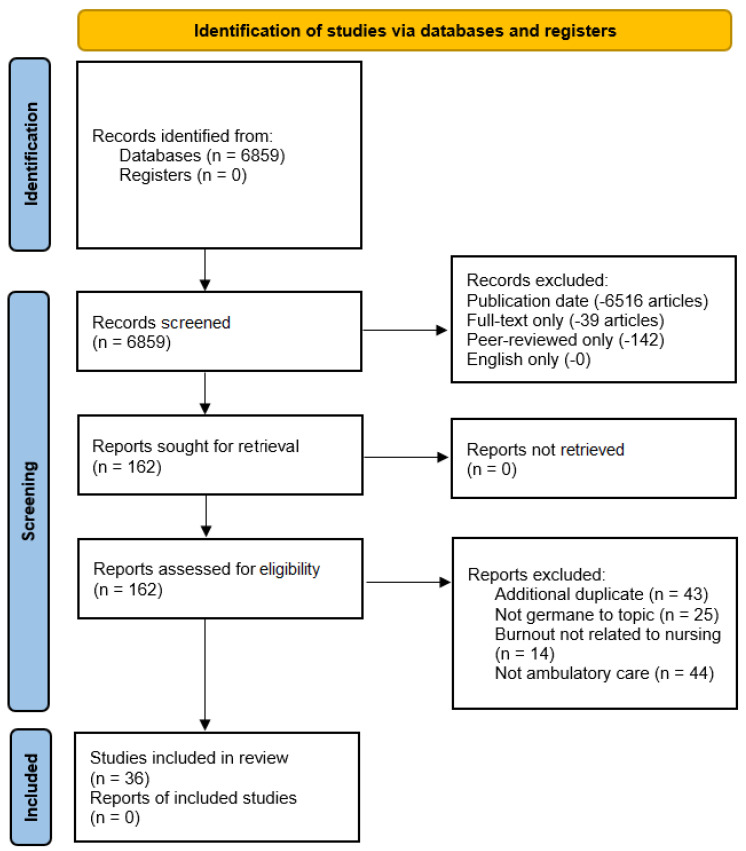

This systematic review was guided by the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol. The 2020 PRISMA checklist and flow diagram were used in an effort to demonstrate process transparency and the thoroughness of the research team’s rapid review process and related research databases.

2.1. Overview

The authors of this manuscript constituted the entire research team for this study. Our research team’s overall intent was to investigate underlying factors (constructs) influencing burnout in the field of nursing for ambulatory care (outpatient) healthcare organizations in the present day. Three main research databases were queried using the EBSCOhost platform via the Southern Illinois University-Carbondale library website: Academic Search Complete, CINAHL Plus, and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Our research team used multiple iterations of review search terms to identify a search string that encompassed as many articles related to the review topic as possible. Proper identification of current publications (article manuscripts) surrounding the ongoing nursing shortage in the healthcare industry began with basic search engine (Google, etc.) searches to identify initial terminology related to the study topic. Next, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), the controlled vocabulary thesaurus that indexes publications for PubMed, was also searched. Finally, the library’s EBSCOhost advanced search preempted (suggested) terminology was also utilized.

Multiple iterations of searches were conducted with varying Boolean operators to identify the largest possible review sample for this study. The final search string identified by the team was as follows:

[(“nursing shortage’) AND (“ambulatory care” OR “outpatient care” OR “outpatient services” OR “urgent care” OR “clinic visits”) AND (“burnout OR burn-out OR burn out OR stress OR occupational stress or compassionate fatigue”)]

After an initial search, which yielded 6859 articles, our research team narrowed down the results by applying filters for publication dates between 1 January 2022 and 2024, leading to the identification of 343 articles. The selection of the 1 January 2022 date was crucial as it allowed the team to focus on understanding the reasons behind nursing-related workforce burnout in the ambulatory care setting, considering the decreasing rates of COVID-19 transmission and the alleviating concerns of the pandemic within the industry. While the incidence and prevalence of the virus varied across countries at any one time, the 1 January 2022 to present publication date search criteria were selected by our research team in an attempt to identify potential constructs for the research topic during the initial stages of increasing vaccination rates and a significant drop in the spread of the virus during this timeframe.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Published manuscripts were included in the review if nursing shortages were specifically addressed, as related to burnout challenges and/or underlying themes. Publications had to be published in good-quality, peer-reviewed journals and/or identified as academic journals by the EBSCOhost database library website. Our research team implemented supplementary database search parameters to generate targeted and relevant results that aligned with the specific research objectives. In addition to the 1 January 2022 through 2024 publication date criteria (−6516 articles), full-text filtering was also applied (−39 articles). Peer-reviewed articles only were filtered again using the EBSCOhost database option, resulting in 162 articles remaining (−142 articles). The option to further delineate down to academic journals only and English-only articles did not result in the removal of any further manuscripts beyond this point (−0 articles).

Using the available menu/check-box filter options on the EBSCOhost platform, our research team carried out all the exclusion steps mentioned above. Figure 1 visually represents the rapid review process and the search exclusion criteria applied, leading to a final set of 162 articles.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) figure that demonstrates the study selection process.

The authors of this study conducted a comprehensive review of the included studies, involving a thorough examination of each identified publication by at least two members of the research team. Table 1 presents the distribution of three sets, each containing 162 review articles, which were assigned to individual research team members.

Table 1.

Reviewer assignment of the initial database search findings (full-article review).

| Article Assignment | Reviewer 1 | Reviewer 2 | Reviewer 3 | Reviewer 4 | Reviewer 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles 1–40 | X | X | X | ||

| Articles 41–80 | X | X | X | ||

| Articles 81–120 | X | X | X | ||

| Articles 121–162 | X | X | X |

Efforts included in the full-text review of the remaining manuscripts included the assessment of each manuscript’s patient population, intervention, comparison, and outcome(s) (PICO) variables, including assessing each article’s research method(s), validity, and the reliability of data. This assessment by our research team occurred only after the application of the EBSCOhost search parameters. After conducting a full-text review for eligibility, our research team identified 36 publications that met the criteria and were retained for further analysis. The articles removed from the review to result in the remaining 36 were excluded for reasons as categorized below:

In total, 43 articles were identified as additional duplicates not identified previously by the research database.

Out of the total, 25 articles were found to be irrelevant to the research topic. These articles were either mistakenly included in the initial database search or mentioned “nursing” in the context of healthcare delivery but were not directly related to “nursing burnout” or similar subjects. Of these, 14 articles were specifically focused on burnout in the health professions, but not specific to the field of nursing (i.e., physicians, therapists, other medical providers).

In total, 44 articles were removed for focusing on themes related to this study but not specific to the outpatient/ambulatory care setting.

To address potential article bias or conflicts related to the application of selection criteria, our research team engaged in online collaboration through webinars. During multiple consensus meetings, no disagreements arose among the team members on these matters.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

The team’s full-text review of the 36 articles identified underlying constructs (characteristics) associated with nursing burnout in the ambulatory care/outpatient healthcare settings, specifically, from the database search date filter, those published from 1 January 2022 through 2024. A summary of the review findings for each article is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of findings (n = 36).

| Reference Number and Authors(s)/Year | Article Title | Journal/Publication | Participant Population | Purpose/Method | Outcome/Observation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] Dilmaghani et al., 2022 |

Work-family conflict and the professional quality of life and their sociodemographic characteristics among nurses: A cross-sectional study in Tehran, Iran | BMC Nursing |

|

|

|

| [6] Girard and Nardone, 2022 |

The Oregon Wellness Program: Serving Healthcare Professionals in Distress from Burnout and COVID-19 | Journal of Medical Regulation |

|

|

|

| [7] Opoku et al., 2022 |

Attrition of Nursing Professionals in Ghana: An Effect of Burnout on Intention to Quit | Nursing Research & Practice |

|

|

|

| [8] Udoh and Kabunga, 2022 |

Burnout and Associated Factors among Hospital-Based Nurses in Northern Uganda: A Cross-Sectional Survey | BioMed Research International |

|

|

|

| [9] Thapa et al., 2022 |

Job demands, job resources, and health outcomes among nursing professionals in private and public healthcare sectors in Sweden—a prospective study | BMC Nursing |

|

|

|

| [10] Poku et al., 2022 |

Impacts of Nursing Work Environment on Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Burnout in Ghana | Nursing Research & Practice |

|

|

|

| [11] Litke et al., 2022 |

Building resilience in German primary care practices: a qualitative study | BMC Primary Care |

|

|

|

| [12] Yosef et al., 2022 |

Occupational Stress among Operation Room Clinicians at Ethiopian University Hospitals | Journal of Environmental and Public Health |

|

|

|

| [13] Bodenheimer, T., 2022 |

Revitalizing Primary Care, Part 2: Hopes for the Future | Annals of Family Medicine |

|

|

|

| [14] Sirkin et al., 2023 |

Primary Care’s Challenges and Responses in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from AHRQ’s Learning Community | Annals of Family Medicine |

|

|

|

| [15] Al Sabei et al., 2022 |

Relationship between interprofessional teamwork and nurses’ intent to leave work: The mediating role of job satisfaction and burnout | Nursing Forum |

|

|

|

| [16] Terp et al., 2022 |

A feasibility study of a cognitive behavioral based stress management intervention for nursing students: results, challenges, and implications for research and practice | BMC Nursing |

|

|

|

| [17] Poon et al., 2022 |

A global overview of healthcare workers’ turnover intention amid COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with future directions | BMC |

|

|

|

| [18] Park et al., 2022 |

Latent profile analysis on Korean nurses: Emotional labor strategies and well-being | Journal of Advanced Nursing |

|

|

|

| [19] Anskär at al., 2022 |

‘But there are so many referrals which are totally … only generating work and irritation’: a qualitative study of physicians’ and nurses’ experiences of work tasks in primary care in Sweden | Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care |

|

|

|

| [20] Shen et al., 2022 |

Analysis of the Effect of the Communication Ability of Nurses in Outpatient Infusion Room on the Treatment Experience of Patients and Their Families | Computational & Mathematical Methods in Medicine |

|

|

|

| [21] Dewey and Allwood, 2022 |

When Needs Are High but Resources Are Low: A Study of Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress Symptoms Among Nurses and Nursing Students in Rural Uganda | International Journal of Stress Management |

|

|

|

| [22] Poku et al., 2022 |

Quality of work-life and turnover intentions among the Ghanaian nursing workforce: A multicenter study | PloS one |

|

|

|

| [23] Tolksdorf et al., 2022 |

Correlates of turnover intention among nursing staff in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review | BMC Nursing |

|

|

|

| [24] Hegarty et al., 2022 |

Nurse staffing levels within acute care: results of a national day of care survey | BMC Health Services Research |

|

|

|

| [25] Paulus, 2022 |

Exploring the Evidence: Considerations for the Dialysis Practice Setting Approach to Staffing | Nephrology Nursing Journal |

|

|

|

| [26] Kühl et al., 2022 |

General practitioner care in nursing homes during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: a retrospective survey among nursing home managers | BMC Primary Care |

|

|

|

| [27] Midje et al., 2022 |

The role of working environment and employee engagement in person-centered processes for older adults in long-term care services | International Practice Development Journal |

|

|

|

| [28] Heuel et al., 2022 |

Chronic stress, behavioral tendencies, and determinants of health behaviors in nurses: a mixed-methods approach | BMC Public Health |

|

|

|

| [29] Jingxia et al., 2022 |

The changes in the nursing practice environment brought by COVID-19 and improvement recommendations from the nurses’ perspective: a cross-sectional study | BioMed Central |

|

|

|

| [30] Phiri et al., 2022 |

International recruitment of mental health nurses to the national health service: a challenge for the UK | BMC Nursing |

|

|

|

| [31] Jithitikulchai, 2022 |

Improving allocative efficiency from network consolidation: a solution for the health workforce shortage | BMC |

|

|

|

| [32] Jones et al., 2022 |

Rapid Deployment of Team Nursing During a Pandemic: Implementation Strategies and Lessons Learned | Critical Care Nurse |

|

|

|

| [33] Olaussen et al., 2022 |

Integrating simulation training during clinical practice in nursing homes: an experimental study of nursing students’ knowledge acquisition, self-efficacy and learning needs | BMC |

|

|

|

| [34] Phillips et al., 2022 |

The impact of the work environment on the health-related quality of life of Licensed Practical Nurses: a cross-sectional survey in four work environments | BMC |

|

|

|

| [35] Kim et al., 2022 |

Combination Relationship between Features of Person-Centered Care and Patient Safety Activities of Nurses Working in Small–Medium-Sized Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study | Jiwon Nursing Reports |

|

|

|

| [36] Horvath and Carter, 2022 |

Emergency Nurses’ Perceptions of Leadership Strategies and Intention to Leave: A scoping review of the literature | Canadian Journal of Emergency Nursing |

|

|

|

| [37] Nuruzzaman et al., 2022 |

Adopting workload-based staffing norms at public sector health facilities in Bangladesh: evidence from two districts | BMC |

|

|

|

| [38] Hasselblad and Loan, 2022 |

Implementing Shared Governance to Improve Ambulatory Care Nurse Perceptions of Practice Autonomy | AAACN Viewpoint |

|

|

|

| [39] HakemZadeh et al., 2022 |

Differential Relationships Between Work-Life Interface Constructs and Intention to Stay in or Leave the Profession: Evidence from Midwives in Canada | Psychological Reports |

|

|

|

| [40] Unsworth, 2022 |

In plain sight: the untapped potential of district nurses | Journal of Community Nursing |

|

|

|

3.2. Identification of Underlying Constructs

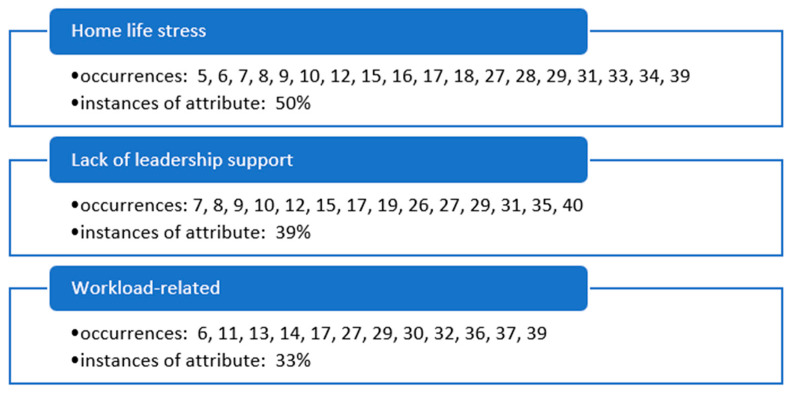

Early in the review team’s consensus meetings, three primary themes (underlying constructs) were identified in the literature, supporting the research topic of facilitators associated with nursing burnout in the ambulatory care setting as COVID-19 subsides (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Primary occurrences of underlying themes (constructs) influencing nursing burnout in ambulatory care organizations as identified in the literature.

Home life stress was a factor of nursing burnout during this timeframe of the pandemic in ambulatory care organizations at 50% instances of attribute contribution. This identified construct was observed the most in the literature of all the identified constructs and was a significant issue, as discussed in the identified articles. A lack of outpatient facilities, leadership support, and workload-related issues were also identified by the research team as significant contributing factors, at 39% and 33% instances of attribute each in the review, respectively.

4. Discussion

Each identified construct in this review supports the research team’s initial hypothesis that significant contributors to burnout in the field of nursing are continuing as the global pandemic continues to subside. With higher vaccination rates, lower transmission of the virus, and even fewer acute symptoms related to infection, the burnout of nurses in the healthcare industry continues, including in outpatient care facilities. As prior research identified contributing factors specifically related to the COVID-19 virus and related nursing personnel threats [1,2,3], this review identified what can be considered more routine or non-pandemic-related contributing factors to nursing burnout as COVID-19 continues to subside.

4.1. Home and/or Work Stress Contributing to Nursing Career Burnout

Health professionals in the nursing field are struggling regardless of specialty area. Nurses are leaving their current positions and, in some cases, the healthcare field entirely, seeking careers that are significantly less stressful and safer to work in [6,16,39]. Research has shown that career burnout is associated with both home and work stress. Work–family conflict is work and family roles being incompatible, causing tension in the home and at work [5,16,29]. This incompatibility has majorly contributed to the extreme nursing shortage we are experiencing in today’s health industry. It will be crucial to the future success of the healthcare industry to evaluate these stressors and address them accordingly.

About one third of an individual’s life is spent at the workplace, which can be a strain on one’s mental health and impede the ability to provide quality care for patients as well as providing for their loved ones at home [5,16,33,39]. Contributors of work stress include unsafe working conditions, increased working hours, and increased patient loads. The COVID-19 pandemic brought about a strenuous working environment for nurses, causing an increased feeling of burnout [8,10]. Personal protective equipment was limited, and large influxes of patients at one time resulted in longer hours and unsafe nurse-to-patient ratios [22,39]. Nearly 3 nurses per 1000 were abandoning their positions at bedside, leaving the nurses that were left to take on each of these dilemmas [5,10,12]. Solutions to addressing these issues were identified in various studies and included enhancing interprofessional teamwork, providing improved occupational health services, adjusting working hours, and providing continuous mental health services to employees [6,8,15]. Each of these areas of improvement have been found to curb the intentions of nurses to quit.

Burnout affects nearly half of all nurses, and these numbers are even higher in certain specialties [6,8,15]. Though work–life has a direct correlation to burnout, studies have also found associations of home life and sociodemographic factors to be contributors to the high prevalence of nurse burnout [15]. In one study, nurses were surveyed to evaluate the correlation between job burnout, professional quality of life, and home conflicts and the interference with work. The three-part questionnaire found that factors such as having children, living with parents, having a disabled family member at home, and having a second job were all significant factors that contributed to professional quality of life [5]. Studies to address these concerns suggest that customizing emotional and mental programs to respond to high-risk profiles will be beneficial to both employees and the organization as a whole [6,8,9,15]. The success of an organization and avoidance of employee burnout truly rely on an organization’s ability to realize and address the aforementioned factors and help nurses establish a positive work–life balance in order to attract new employees and retain the staff they currently have.

4.2. Lack of Organization/Administration Support

Recent studies have shown that burnout has been linked to nurses’ intention to quit the profession [8,26,35]. It was reported that moderate to high burnout has been reported among nurses and other healthcare professionals [7,8,26]. High workload, years of practice, resilience, inadequate staffing, and lack of leadership support have been identified as some of the highest complaints amongst healthcare workers. In one study, a prevalence rate of 69.0% of nurses with intention to quit their profession was reported [7].

According to Poku, Donkor, and Naab, another study carried out in Ghana reported health labor force scarcities have consequences on global healthcare delivery and quality of patient care [10]. Understanding the challenges of turnover rate and the retention of staff is essential in the discussion of strategies for improving the nursing workforce. High staff turnover intentions in many organizations are attributed to factors such as poor quality of staffing and inadequacy of proper equipment to care for patients. Such poor work conditions present high work demand, inadequate group support, and increased physical and emotional work demand. Lack of support from nurse managers, unjustified workloads, and increased emotional exhaustion of RNs mostly lead to increased staff intentions of resigning [10].

A study conducted in Oman by Sabei et al. found that nursing turnover may adversely affect the delivery of healthcare services and potentially threaten patient safety outcomes [15]. Nursing turnover has been associated with increased healthcare costs and additional financial burdens for organizations. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated this issue, with evidence showing that an increasing number of nursing professionals have left the bedside and intend to leave their jobs due to the threat posed by the virus. Therefore, the World Health Organization and many healthcare policymakers have emphasized the urgent need to invest in nurses to strengthen global health. Identifying the factors influencing nurses’ intentions to leave is a crucial step in enhancing retention and improving overall patient safety [7,8,15,30,32,39].

4.3. Workload-Related Issues

The COVID-19 outbreak caused a serious increase in workload in the healthcare field. Due to the increasing number of patients during the outbreak, there were not enough workers to cover the long shifts that needed to be covered. Many nurses had a lot of struggles to overcome with the long hours of work. There was an increase in nurses becoming burnt out in their profession and quitting their jobs, only to cause harder times and workloads for other nurses. Many nurses complained of conflicts with home life and family time. They could not spend the time they needed to with their families due to working schedules. These long hours caused even more nurses to quit their jobs and also contributed to a greater number of dysfunctional families.

The overwhelming workload was caused by increased patients and a decrease in workers. The same problems are being experienced worldwide. There have been many days where there was a 50–60% increase in the daily workload [11,37]. Due to the complexity of healthcare, when there is one portion of the business that is being overworked or understaffed, it affects multiple areas of the industry, not just nursing. Nurses already work long hours and when they are required to work extra it causes a domino effect. Fully staffing one department by utilizing the staff of another leads the helping unit potentially being understaffed. Then, trying to staff that unit leads to another unit being short-staffed, and so on. Moving staff around between units in a hospital is not a sustainable solution, and has only contributed more to nurses becoming frustrated with their jobs [13,27,29].

When the process of being overworked continues, many problems arise. In one study, 300 nurses who reported experiencing high levels of workplace burnout also had signs of depression. They were also not living a healthy lifestyle and starting to show weight gain. These same nurses agreed that they were not able to complete all management duties efficiently and effectively due to workload. None of them were happy with the way their lives have been through the stress of COVID-19 and all of the extra work it was taking to keep things up and running in outpatient medical facilities [6,8,17,29].

4.4. Ambulatory Care Nursing Burnout as the Pandemic Subsides

This rapid review identified underlying themes related to nursing burnout in the outpatient/ambulatory care healthcare industry, which can easily be mapped to pre- and mid-pandemic challenges [1,2,3] as well. While these underlying variables identified by the research team do not add any additional or new influencing constructs to the ongoing industry challenge experienced by healthcare organizations and their leaders, the findings do support a continued requirement to address this important industry dilemma. While balancing home life with workplace expectations and needs, a lack of organizational leadership support, and other work-related variables were identified in this review as contributing factors to nursing burnout in the ambulatory care setting, healthcare organizational leadership should continue to assess and address the need to reverse such contributing factors as COVID-19 continues to subside and outpatient care, specifically any postponed or delayed routine care, resumes in this industry segment.

5. Conclusions

For a long time, nurses have experienced compassion fatigue and burnout in the healthcare industry. Improper work–life balance, lack of administrative support, and being overworked and underappreciated are the biggest contributing factors to these feelings. A lack of response to these issues, especially with the added pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic, has led to nurses leaving the bedside and the profession in droves. As demonstrated in this review, current contributing factors leading to nursing burnout have changed minimally since the peak of the global pandemic [1,2,3] and the underlying contributing factors continue to exist.

This rapid review has multiple limitations, as with any qualitative study. The review only assesses nursing burnout in the ambulatory care segment of the healthcare industry, which does vary across multiple (national) healthcare systems. Characteristics specific to individual healthcare systems will most likely have inherent influencing variables related to nurse burnout, and therefore should be investigated as future research. The review includes a limited publication (manuscript) date range to determine if any new underlying constructs related to nursing burnout in ambulatory care exist, as compared to previously known influencing variables. This date range search parameter is not perfectly assignable to the decline in COVID-19 prevalence across all regions and levels of virulence. As a result, the findings of this review should be interpreted generally, yet do support previously known factors contributing to nursing burnout in the healthcare industry.

In order to remedy the extreme nursing shortage we are experiencing, future research and leadership initiatives should address the root causes of nurses experiencing burnout as the pandemic continues to subside. Actions to support such initiatives may include listening to employees, supporting employees in establishing a healthy work–life balance, and implementing solutions to satisfy and retain their employees for the long term in outpatient care organizations.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this review in accordance with ICMJE standards. Conceptualization, C.L., J.B., S.A., B.A. and B.J.A.; methodology, C.L.; software, C.L.; validation, C.L., J.B., S.A., B.A. and B.J.A.; formal analysis, C.L., J.B., S.A., B.A. and B.J.A.; investigation, C.L., J.B., S.A., B.A. and B.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B., S.A., B.A. and B.J.A.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Galanis P., Vraka I., Fragkou D., Bilali A., Kaitelidou D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021;77:3286–3302. doi: 10.1111/jan.14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez R., Lord H., Halcomb E., Moxham L., Middleton R., Alananzeh I., Ellwood L. Implications for COVID-19: A systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020;111:103637. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sena Santos F.M., Dantas Pessoa J., da Silva L.S.R., Honorio M.L.T., Santos de Melo M., Alves do Nascimento N. Physical exhaustion of nursing professionals in the COVID-19 combat. Nurs. Sao Paulo. 2021;24:5974–5979. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sriharan A., West K.J., Almost J., Hamza A. COVID-19-Related Occupational Burnout and Moral Distress among Nurses: A Rapid Scoping Review. Nurs. Leadersh. 2021;34:7–19. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2021.26459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dilmaghani R.B., Armoon B., Moghaddam L.F. Work-family conflict and the professional quality of life and their sociodemographic characteristics among nurses: A cross-sectional study in Tehran, Iran. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:289. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-01069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girard D.E., Nardone D.A. The Oregon Wellness Program: Serving Healthcare Professionals in Distress from Burnout and COVID-19. J. Med. Regul. 2022;108:27–34. doi: 10.30770/2572-1852-108.3.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opoku D.A., Ayisi-Boateng N.K., Osarfo J., Sulemana A., Mohammed A., Spangenberg K., Awini A.B., Edusei A.K. Attrition of Nursing Professionals in Ghana: An Effect of Burnout on Intention to Quit. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2022;2022:3100344. doi: 10.1155/2022/3100344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Udho S., Kabunga A. Burnout and Associated Factors among Hospital-Based Nurses in Northern Uganda: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BioMed Res. Int. 2022;2022:8231564. doi: 10.1155/2022/8231564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thapa D.R., Stengård J., Ekström-Bergström A., Areskoug Josefsson K., Krettek A., Nyberg A. Job demands, job resources, and health outcomes among nursing professionals in private and public healthcare sectors in Sweden—A prospective study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:140. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00924-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poku C.A., Donkor E., Naab F. Impacts of Nursing Work Environment on Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Burnout in Ghana. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2022;2022:1310508. doi: 10.1155/2022/1310508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litke N., Weis A., Koetsenruijter J., Fehrer V., Koeppen M., Kuemmel S., Szecsenyi J., Wensing M. Building resilience in German primary care practices: A qualitative study. BMC Prim. Care. 2022;23:221. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01834-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yosef B., Berhe Y.W., Fentie D.Y., Getahun A.B. Occupational Stress among Operation Room Clinicians at Ethiopian University Hospitals. J. Environ. Public Health. 2022;2022:2077317. doi: 10.1155/2022/2077317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodenheimer T. Revitalizing Primary Care, Part 2: Hopes for the Future. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022;20:469–478. doi: 10.1370/afm.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirkin J.T., Flanagan E., Tong S.T., Coffman M., McNellis R.J., McPherson T., Bierman A.S. Primary Care’s Challenges and Responses in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from AHRQ’s Learning Community. Ann. Fam. Med. 2023;21:76–82. doi: 10.1370/afm.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Sabei S.D., Labrague L.J., Al R.O., AbuAlRub R., Burney I.A., Jayapal S.K. Relationship between interpro-fessional teamwork and nurses’ intent to leave work: The mediating role of job satisfaction and burnout. Nurs. Forum. 2022;57:568–576. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terp U., Bisholt B., Hjärthag F. A feasibility study of a cognitive behavioral based stress management intervention for nursing students: Results, challenges, and implications for research and practice. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:30. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00761-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poon Y.-S.R., Lin Y.P., Griffiths P., Yong K.K., Seah B., Liaw S.Y. A global overview of healthcare workers’ turnover intention amid COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with future directions. Hum. Resour. Health. 2022;20:70. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00764-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park C., Cho H., Lee D., Jeon H. Latent profile analysis on Korean nurses: Emotional labour strategies and well-being. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022;78:1632–1641. doi: 10.1111/jan.15062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anskär E., Falk M., Sverker A. “But there are so many referrals which are totally… only generating work and irritation”: A qualitative study of physicians’ and nurses’ experiences of work tasks in primary care in Sweden. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2022;40:350–359. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2022.2139447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen X., Zhang Y., Wei J. Analysis of the Effect of the Communication Ability of Nurses in Outpatient Infusion Room on the Treatment Experience of Patients and Their Families. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022;2022:1143662. doi: 10.1155/2022/1143662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Dewey L.M., Allwood M.A. When needs are high but resources are low: A study of burnout and secondary traumatic stress symptoms among nurses and nursing students in rural Uganda. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2022;29:31–43. doi: 10.1037/str0000238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poku C.A., Alem J.N., Poku R.O., Osei S.A., Amoah E.O., Ofei A.M.A. Quality of work-life and turnover intentions among the Ghanaian nursing workforce: A multicentre study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0272597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tolksdorf K.H., Tischler U., Heinrichs K. Correlates of turnover intention among nursing staff in the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:174. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00949-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegarty H., Knight T., Atkin C., Kelly T., Subbe C., Lasserson D., Holland M. Nurse staffing levels within acute care: Results of a national day of care survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022;22:493. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07562-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paulus A.B. Exploring the Evidence: Considerations for the Dialysis Practice Setting Approach to Staffing. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2022;49:369–383. doi: 10.37526/1526-744X.2022.49.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kühl A., Hering C., Herrmann W.J., Gangnus A., Kohl R., Steinhagen-Thiessen E., Kuhlmey A., Gellert P. General practitioner care in nursing homes during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: A retrospective survey among nursing home managers. BMC Prim. Care. 2022;23:334. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01947-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Midje H.H., Torp S., Øvergård K.I. The role of working environment and employee engagement in person-centred processes for older adults in long-term care services. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2022;12:58–76. doi: 10.19043/ipdj.122.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heuel L., Lübstorf S., Otto A.K., Wollesen B. Chronic stress, behavioral tendencies, and determinants of health behaviors in nurses: A mixed-methods approach. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:624. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12993-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jingxia C., Longling Z., Qiantao Z., Weixue P., Xiaolian J. The changes in the nursing practice environment brought by COVID-19 and improvement recommendations from the nurses’ perspective: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022;22:754. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phiri P., Sajid S., Baykoca A., Shetty S., Mudoni D., Rathod S., Delanerolle G. International recruitment of mental health nurses to the national health service: A challenge for the UK. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:355. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-01128-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jithitikulchai T. Improving allocative efficiency from network consolidation: A solution for the health work-force shortage. Hum. Resour. Health. 2022;20:59. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00732-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones K.L., Johnson M.R., Lehnertz A.Y., Kramer R.R., Drilling K.E., Bungum L.D., Bell S.J. Rapid Deployment of Team Nursing during a Pandemic: Implementation Strategies and Lessons Learned. Crit. Care Nurse. 2022;42:27–36. doi: 10.4037/ccn2022399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olaussen C., Steindal S.A., Jelsness-Jørgensen L.P., Aase I., Stenseth H.V., Tvedt C.R. Integrating simulation training during clinical practice in nursing homes: An experimental study of nursing students’ knowledge acquisition, self-efficacy and learning needs. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:47. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00824-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips L.A., Santos N.d.L., Ntanda H., Jackson J. The impact of the work environment on the health-related quality of life of Licensed Practical Nurses: A cross-sectional survey in four work environments. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2022;20:44. doi: 10.1186/s12955-022-01951-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M.S., Cho Y.O., Park J. Combination Relationship between Features of Person-Centered Care and Patient Safety Activities of Nurses Working in Small–Medium-Sized Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2022;12:861–872. doi: 10.3390/nursrep12040083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horvath S., Carter N. Emergency Nurses’ Perceptions of Leadership Strategies and Intention to Leave: A scoping review of the literature. Can. J. Emerg. Nurs. (CJEN) 2022;45:11–36. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nuruzzaman, Zapata T., Cruz V.D.O., Alam S., Tune S.N.B.K., Joarder T. Adopting workload-based staffing norms at public sector health facilities in Bangladesh: Evidence from two districts. Hum. Resour. Health. 2022;19:151. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00697-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasselblad M.M., Loan L.A. Implementing Shared Governance to Improve Ambulatory Care Nurse Perceptions of Practice Autonomy. AAACN Viewp. 2022;44:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.HakemZadeh F., Chowhan J., Neiterman E., Zeytinoglu I., Geraci J., Lobb D. Differential Relationships between Work-Life Interface Constructs and Intention to Stay in or Leave the Profession: Evidence from Midwives in Canada. Psychol. Rep. 2022 doi: 10.1177/00332941221132994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unsworth J. In plain sight: The untapped potential of district nurses. J. Community Nurs. 2022;36:24–25. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.