Abstract

Despite the well-documented association between experiences of substance use stigma and adverse mental health outcomes, little is known about the mechanisms underlying this association. Utilizing a community sample of substance-using adults who have experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, the current study examined the role of dysregulation stemming from both negative and positive emotions in the relation between substance use stigma and depressive symptoms. Community participants (N = 320, 46.9% women) completed self-report measures of substance-use-related stigma experiences, negative and positive emotion dysregulation, and depressive symptoms. Results showed that, adjusting for gender and substance use severity, substance use stigma was positively associated with emotion dysregulation, which in turn related to depressive symptoms. Substance use stigma was also found to be indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through emotion dysregulation, suggesting that emotion dysregulation accounted for the significant association between substance use stigma and depressive symptoms. These findings provide initial support for the role of emotion dysregulation as a mechanism through which stigma operates to undermine the mental health of substance-using, trauma-exposed individuals. Results underscore the potential utility of targeting emotion dysregulation in intervention efforts that are designed to facilitate stigma coping among individuals who use alcohol and/or drugs.

Keywords: stigma, emotion dysregulation, substance use, depression

Among individuals who use substances, stigma has been identified as a major barrier to recovery. Across numerous studies, experiences of prejudice and discrimination from family members and healthcare providers, as well as the internalization of negative stereotypes and shame associated with one’s substance use (e.g., the belief that individuals who use substances are untrustworthy and immoral), have been linked to elevated depressive symptoms (Ahern et al., 2007; Link et al., 1997), greater severity of existing substance use problems (Dearing et al., 2005; Kulesza et al., 2017), and lower substance use treatment utilization and retention (Cunningham et al., 1993; Semple et al., 2005). Despite these well-documented associations, little research has examined the psychological mechanisms through which stigma operates to adversely impact the well-being of individuals who use substances. Efforts to identify such mechanisms are crucial given their potential to inform the development of individual-level stigma coping interventions, which have shown initial promise in alleviating the health burden of substance use stigma (Luoma et al., 2008, 2012). To this end, the present study examined the role of emotion dysregulation (i.e., maladaptive ways of responding to both negative and positive emotions, including nonaccepting responses and difficulties controlling behaviors; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Weiss et al., 2015), as a possible mechanism underlying the association between experiences of substance use stigma and depressive symptoms among a community sample of substance-using, trauma-exposed adults.

Though evidence directly pertaining to substance use stigma is limited, research on other marginalized populations has implicated emotion dysregulation as an important mechanism through which stigma may operate to compromise mental health. Specifically, exposure to stigma-related stress can deplete self-regulatory resources, thereby undermining individuals’ ability to understand and manage their emotions, both at the state level (i.e., following acute experiences of prejudice and discrimination) and at the trait level (i.e., in the context of cumulative experiences of social rejection and devaluation over time; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Inzlicht et al., 2006). Across several studies, rumination, a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy that involves passively and repetitively focusing on one’s problems and their causes, mediated the association between experiences of discrimination and internalizing mental health symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety) among racial/ethnic and sexual minorities (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008, 2009; Miranda et al., 2013; Timmins et al., 2020). Other emotion regulation deficits, including lower emotional awareness and acceptance, limited access to various emotion regulation strategies, and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors in the context of intense emotions, have also been shown to mediate the association of experiences, anticipation, and internalization of stigma with depressive symptoms among gay and bisexual men (Pachankis et al., 2015) and HIV-positive individuals (Rendina et al., 2017).

Whereas extant research on stigma and emotion dysregulation has exclusively focused on difficulties in the regulation of negative emotions, two lines of inquiry suggest that problematic responding to positive emotions, such as happiness, might also play an important role in the context of coping with stigma-related stress. First, although positive emotions are typically viewed as a buffer against stress and a predictor of good psychological adjustment (Tugade et al., 2004), research indicates that regulating positive emotions poses significant cognitive demands (Gross & John, 2003), and that use of ineffective emotion regulation strategies (e.g., suppression) has been linked to increased physiological arousal (Gross & Levenson, 1997). Thus, to the extent that stigma depletes self-regulatory resources, it would likely also interfere with the effective regulation of positive emotions. Second, difficulties regulating positive emotions, including non-acceptance of positive emotions, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions, and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors in the context of positive emotions, have been associated with a number of adverse mental and behavioral health outcomes among trauma-exposed individuals, including posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, depressive symptoms, and substance use (Schick et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2018), further underscoring the clinical utility of elucidating the role of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions in the context of coping with substance use stigma among this population.

In light of these findings, the present research examined the associations among experiences of substance use stigma, difficulties in the regulation of negative and positive emotions (i.e., negative and positive emotion dysregulation), and depressive symptoms among a community sample of substance-using individuals in North America who have experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime. We chose to focus on depressive symptoms as our outcome of interest given that depression is highly comorbid with substance use disorders (Grant et al., 2004) and has been shown to hinder adherence to substance use treatment and increase risk for relapse following treatment (Davis et al., 2008; McKay et al., 2002). Given that trauma-exposed individuals are known to be disproportionately at risk for both depression and substance use disorders (Debell et al., 2014; Rytwinski et al., 2013), they might be particularly vulnerable to the psychosocial impact of substance use stigma and emotion dysregulation. Elucidating the associations of these factors with depressive symptoms can thus highlight the unique vulnerabilities facing this population, thereby informing the development and tailoring of interventions that address co-occurring mental health and substance use concerns in the context of trauma exposure.

Drawing from prior research (Smith et al., 2016), we conceptualized substance use stigma as a multifaceted construct that encompasses three interrelated processes: enacted stigma (i.e., experiences of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination from others in the past or present), anticipated stigma (i.e., expectations of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination from others in the future), and internalized stigma (i.e., endorsement and application of negative stereotypes to oneself). We hypothesized that substance use stigma would be positively associated with emotion dysregulation, which would in turn relate to depressive symptoms. We further hypothesized that substance use stigma would be indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through emotion dysregulation. Our hypothesized conceptual model is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Conceptual Model

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DERS-P = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale—Positive; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected as part of a larger study examining the role of executive functioning in the association between PTSD symptoms and substance use. Participants were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform. Beyond generating reliable data (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Shapiro et al., 2013), MTurk’s subject pool is diverse (Buhrmester et al., 2011) and represents the general population in terms of demographics (Mishra & Carleton, 2017) and prevalence of certain mental health problems, including depression (Shapiro et al., 2013).

Participants were screened for the larger study based upon five inclusionary criteria: (a) aged 18 years or older; (b) living in North America; (c) working knowledge of the English language; (d) endorsed experiencing a traumatic event on the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (i.e., something that is unusually or especially frightening, horrible, or traumatic, such as a serious accident or fire, a physical or sexual assault or abuse, an earthquake or flood, a war, seeing someone be killed or seriously injured, or having a loved one die through homicide or suicide; Prins et al., 2016) in their lifetime, and (e) endorsed at least one instance of alcohol or drug use in the preceding 30 days. Participants who met eligibility criteria provided informed consent and completed the survey on Qualtrics data collection platform. Participants were compensated $2.50 for study participation. All procedures were approved by the (University of Rhode Island) Institutional Review Board.

Of the obtained 951 responses, 392 participants were excluded for not meeting one or more inclusionary criteria (remaining n = 559). We then excluded 172 participants (remaining n = 387) who failed to pass any of the four validity checks interspersed in the study to ensure attentive responding (three items; e.g., participants being asked to rate “I am paid biweekly by leprechauns” on a 6-point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) and comprehension (one item asking participants to click on a little blue circle rather than the scale with items labeled from 1 to 5; Meade and Craig, 2012; Oppenheimer et al., 2009), and 67 participants who attempted to complete the survey more than once. Thus, the final analytic sample for the present study included 320 participants. Average age of participants was 35.79 years (SD = 10.63); 150 identified as women (46.9%), and 261 as White (81.6%). See Table 1 for further sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variables | M (SD) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 35.79 (10.63) | |

| Gender | ||

| Man | 161 (50.3%) | |

| Woman | 150 (46.9%) | |

| Transgender | 3 (0.9%) | |

| Genderqueer/non-binary | 4 (1.3%) | |

| Prefer not to respond | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 44 (13.8%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 264 (82.5%) | |

| Prefer not to respond | 12 (3.8%) | |

| Race a | ||

| Black or African American | 41 (12.8%) | |

| White | 261 (81.6%) | |

| American Indian/Native American | 14 (4.4%) | |

| Asian | 9 (2.8%) | |

| Not listed | 4 (1.3%)b | |

| Prefer not to respond | 4 (1.3%) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed full-time | 258 (80.6%) | |

| Employed part-time | 34 (10.6%) | |

| Not in labor force (e.g., student, homemaker) | 11 (3.4%) | |

| Unemployed | 13 (4.1%) | |

| Prefer not to respond | 4 (1.3%) | |

| Income | $25,847.99 ($35,576.11) | |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 11 (3.4%) | |

| High school degree | 30 (9.4%) | |

| Some college | 87 (27.3%) | |

| 4-year college | 114 (35.6%) | |

| More than 4-year college | 71 (22.2%) | |

| Prefer not to respond | 7 (2.2%) | |

Note.

Participants were able to select more than one descriptor which best described their racial background.

Of the four participants who selected “Not listed,” three wrote in that they identify Hispanic or Latinx as their race, and one wrote in that they identify Middle Eastern or North African as their race.

Measures

Substance Use Stigma

The Substance Use Stigma Mechanisms Scale (SU-SMS; Smith et al., 2016) is an 18-item self-report measure that assesses experiences of substance-use-related stigma across three subscales: enacted stigma (six items; e.g., “family members have looked down on me”), anticipated stigma (six items; e.g., “family members will think that I cannot be trusted”), and internalized stigma (six items; e.g., “having used alcohol and/or drugs makes me feel unclean”). Participants rate each item on a 5-point scale from 1 = Never to 5 = Very often; item scores are averaged to create subscale composite scores, with higher scores indicating more substance use stigma. The SU-SMS has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Smith et al., 2016), and Cronbach’s α in the current sample were .92, .93, and .95 for the enacted, anticipated, and internalized substance use stigma subscales, respectively.

Emotion Dysregulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16 (DERS-16; Bjureberg et al., 2016) is a modified 16-item brief version of the original 36-item DERS (Gratz & Roemer, 2004), a widely-used measure of emotion dysregulation. The DERS-16 is a self-report measure that assesses negative emotion dysregulation, specifically, nonacceptance of negative emotions, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing negative emotions, difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing negative emotions, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Participants rate each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = Almost never to 5 = Almost always, and items are summed to create a total scale score; higher scores reflect greater negative emotion dysregulation. The DERS-16 has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Bjureberg et al., 2016), and Cronbach’s α in the current sample was .96.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Positive (DERS-P; Weiss et al., 2015) is a 13-item self-report measure that assesses difficulties regulating positive emotions, specifically nonacceptance of positive emotions, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions, and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions. Participants rate each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = Almost never to 5 = Almost always, and items are summed to create a total scale score; higher scores reflect greater positive emotion dysregulation. The DERS-P has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Weiss et al., 2015, 2019), and Cronbach’s α in the current sample was .97.

Depressive Symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) is a nine-item self-report measure assessing depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Participants rate each item on a 4-point scale from 0 = Not at all to 3 = Nearly every day, and items are summed to create a total scale score; higher scores reflect greater depressive symptom severity. Scores of 10 or higher indicate depressive symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). The PHQ-9 has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Kroenke et al., 2001), and Cronbach’s α in the current sample was .92.

Covariates

Alcohol Use Problems.

The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993) is a 10-item self-report measure assessing alcohol consumption, drinking behaviors, adverse reactions to drinking, and alcohol-related problems. Participants rate each item on a 4-point scale from 0 = Never to 4 = Daily or almost daily, and items are summed to create a total scale score; higher scores indicate more severe alcohol use problems. Scores of 8 or higher indicate probable alcohol use disorder (AUD). The AUDIT has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Babor et al., 2001; Saunders et al., 1993), and Cronbach’s α in the current sample was .90.

Drug Use Problems.

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982) is a 10-item measure that assesses the presence of problems related to drug use, such as occupational or relational problems, illegal activities, or regret. Participants rate whether they have experienced each problem with response options 0 = No and 1 = Yes, and items are summed to create a total scale score; higher scores indicate more severe drug use problems. Scores of 3 or higher indicate probable drug use disorder (DUD). The DAST has demonstrated good psychometric properties, and Cronbach’s α in the current sample was .82.

Data Analysis

As recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), all study variables were assessed for assumptions of normality. Next, in IBM SPSS v 26, Pearson product–moment correlations were calculated among the primary study variables to explore their bivariate associations. Finally, in Mplus version 7.1, structural equation modeling was used to examine whether emotion dysregulation indirectly explained the relation between substance use stigma and depressive symptoms. Substance use stigma was modeled as a latent (exogenous) variable measured with the three SU-SMS subscales (i.e., enacted, anticipated, and internalized stigma), emotion dysregulation was modeled as a latent (endogenous) variable measured with the DERS (i.e., negative emotion dysregulation) and the DERS-P (i.e., positive emotion dysregulation), and depressive symptoms was modeled as a single observed (endogenous) variable, measured with the PHQ-9. We included severity of alcohol (i.e., AUDIT total score) and drug use problems (i.e., DAST total score) as covariates given that individuals with more severe substance use problems would likely experience greater substance use stigma. Given its established relationship with depression, we also included gender (1 = woman and 0 = man) as a covariate in our model. Further, to confirm the directionality of the indirect effects, we tested an alternative model in which depressive symptoms is posited to influence substance use stigma through emotion dysregulation. Finally, to ensure the robustness of our results, we re-ran our primary analyses in a subsample limited to only those participants with scores consistent with alcohol and/or drug use disorders.

Overall model fit was assessed using the likelihood ratio test based on the chi2 value, which assesses the magnitude of difference between the observed and proposed covariance matrices (Hu & Bentler, 1999). A nonsignificant likelihood ratio test indicated good model fit. However, because the chi2 test rejects even adequately fitting models (Bentler, 1990), fit indices based on the chi2 distribution were also used to assess model fit. Agreement among fit indices provides evidence that at least adequate model fit has been achieved. The comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), an incremental fit index, assessed fit relative to a null model (e.g., a model with all variables uncorrelated); CFI values greater than .95 indicated good model fit. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990) with accompanying 90% confidence intervals (CIs) assessed closeness of fit, with values less than .05 indicating good fit and less than .10 indicating adequate fit. The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) is the standardized difference between the observed and predicted covariance matrices, with values closer to zero indicating better fit and values less than .08 considered acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The bootstrap method was used to estimate the standard error of parameter estimates and bias-corrected CIs of the indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., 2002). In this study, 1,000 bootstrap samples were used to derive estimates of the indirect effect.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Based on benchmarks of skewness > 2 and kurtosis > 7 reflecting non-normality (Curran et al., 1996), scores for the primary study variables were normally distributed. Approximately half of participants reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of depression (n = 166, 51.9%), based on a cutoff score of 10 on the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001). Approximately half of participants reported probable AUD (n = 175, 54.7%), and more than one-third reported probable DUD (n = 126, 39.4%) based on cutoff scores of 8 and 3 on the AUDIT and DAST, respectively (Babor et al., 2001; Skinner, 1982). Bivariate correlations among substance use stigma, negative and positive emotion dysregulation, and depressive symptoms are presented in Table 2. Each of the substance use stigma subscales was significantly positively associated with positive and negative emotion dysregulation, as well as depressive symptoms. Positive and negative emotion dysregulation were also significantly positively related to depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Primary Variables of Interest

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enacted stigma | — | ||||||||

| 2. Anticipated stigma | .84** | — | |||||||

| 3. Internalized stigma | .60** | .65** | — | ||||||

| 4. DERS | .49** | 47** | .40** | — | |||||

| 5. DERS-P | .60** | .61** | .49** | .50** | — | ||||

| 6. PHQ-9 | .49** | .46** | .46** | .70** | .50** | — | |||

| 7. AUDIT | 43** | .44** | .45** | .25** | .38** | .33** | — | ||

| 8. DAST | .45** | .49** | .42** | .42** | .24** | .35** | .27** | — | |

| 9. Gender | −.05 | −.08 | −.04 | .10 | −.12* | .12* | −.002 | .01 | — |

| M (SD) | 2.13 (1.11) | 2.15 (1.18) | 2.56 (1.23) | 42.95 (16.17) | 23.66 (12.65) | 10.62 (7.24) | 11.11 (8.81) | 2.53 (2.53) | — |

| Range | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 16–80 | 12–61 | 0–27 | 0–38 | 0–10 |

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DERS-P = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale—Positive; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire—9; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Primary Analyses

The hypothesized structural model fit the data adequately, χ2(22) = 72.00, p < .001, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.09, 90% CI [0.06, 0.11], SRMR = 0.05; this model is summarized in Figure 2. The association between substance use stigma (i.e., enacted, anticipated, and internalized) and emotion dysregulation (i.e., negative and positive) was significant (β = 0.84, SE = .05, p < .001, 95% CI [0.73, 0.94]), as was the association between emotion dysregulation and depressive symptoms (β = 1.33, SE = .51, p = .009, 95% CI [0.94, 2.55]). Furthermore, the indirect effect of substance use stigma on depressive symptoms through the pathway of emotion dysregulation was also significant (β = 1.12, SE = .52, p = .03, 95% CI [0.72, 2.34]). Notably, the direct effect linking substance use stigma and depressive symptoms was not significant after controlling for emotion dysregulation (β = −0.56, SE = .52, p = .27, 95% CI [−1.79, −0.17]).

Figure 2.

Indirect Effect of Emotion Dysregulation in the Association Between Substance Use Stigma and Depressive Symptoms

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DERS-P = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale—Positive; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Supplementary Analyses

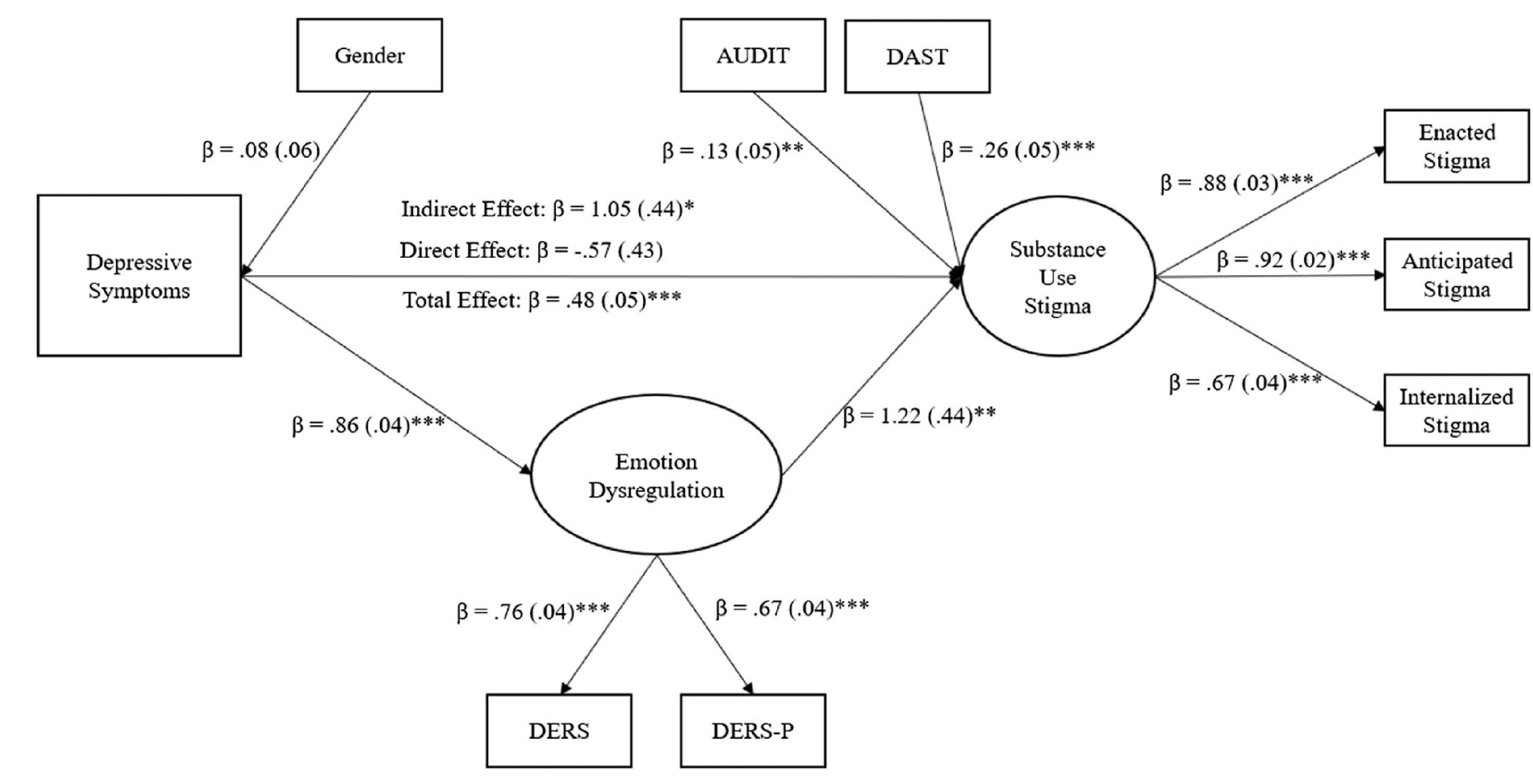

An alternative model was also tested to examine the reverse directionality with depressive symptoms being related to substance use stigma through emotion dysregulation. This model provided worse fit to the data, χ2(22) = 126.68, p < .001, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.12, 90% CI [0.10, 0.15], SRMR = 0.13; this model is summarized in Figure 3. In this model, the association between depressive symptoms and emotion dysregulation was significant (β = 0.86, SE = .04, p < .001, 95% CI [0.78, 0.93]), as was the association between emotion dysregulation and substance use stigma (β = 1.22, SE = .44, p = .005, 95% CI [0.78, 2.33]). Furthermore, the indirect effect of depressive symptoms on substance use stigma through the pathway of emotion dysregulation was also significant (β = 1.05, SE = .44, p = .02, 95% CI [0.64, 2.13]), and the direct effect of depressive symptoms on substance use stigma was not significant after controlling for emotion dysregulation (β = −0.57, SE = .43, p = .19, 95% CI [−1.71, −0.17]).

Figure 3.

Reverse Model Depicting the Indirect Effect of Emotion Dysregulation in the Association Between Depressive Symptoms and Substance Use Stigma

Note. DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DERS-P = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale—Positive; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Finally, we re-ran our primary analyses in a subsample of participants who reported scores on the AUDIT and/or DAST consistent with alcohol and/or drug use disorders, respectively. This model fit the data well, χ2(22) = 69.08, p < .001, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.08, 90% CI [0.06, 0.11], SRMR = 0.04. The association between substance use stigma and emotion dysregulation was significant (β = 0.86, SE = .05, p < .001, 95% CI [0.75, 0.93]), as was the association between emotion dysregulation and depressive symptoms (β = 1.44, SE = .67, p = .03, 95% CI [1.02, 2.40]). Furthermore, the indirect effect of substance use stigma on depressive symptoms through the pathway of emotion dysregulation was significant (β = 1.24, SE = .68, p = .07, 95% CI [0.78, 2.72]). The direct effect linking substance use stigma and depressive symptoms remained significant, though substantially attenuated, after controlling for emotion dysregulation (β = −0.68, SE = .67, p = .32, 95% CI [−2.24, −0.23]).

Discussion

In the past decade, emotion dysregulation has received increasing empirical attention as an important mechanism underlying the adverse impact of stigma on mental and behavioral health. However, most of the existing research in this area has focused on sexual and racial/ethnic minorities (e.g., Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Pachankis et al., 2015), and no study, to our knowledge, has examined the role of positive emotion dysregulation in the context of coping with stigma-related stress. The current investigation extended previous research by examining the associations among experiences of substance use stigma, negative and positive emotion dysregulation, and depressive symptoms among a sample of substance-using, trauma-exposed individuals. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that substance use stigma was positively associated with emotion dysregulation, which in turn related to depressive symptoms. Furthermore, substance use stigma was found to be indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through emotion dysregulation. Taken together, these results highlight the role of substance use stigma as a salient stressor for trauma-exposed individuals, while also illuminating the role of emotion dysregulation as a potential mechanism through which stigma operates to undermine the well-being of this at-risk population.

One key strength of the present investigation is its conceptualization of both substance use stigma and emotion dysregulation as multifaceted constructs. As noted by Smith et al. (2016), few existing studies have collectively measured enacted, anticipated, and internalized substance use stigma as distinct constructs, which is noteworthy given that these stigma processes have been known to differentially impact physical, mental, and behavioral health outcomes (Earnshaw et al., 2013). Similarly, an exclusive focus on negative emotion dysregulation in the extant stigma literature might limit our understanding of the relation between stigma and mental health, especially in contexts where maladaptive responding to positive emotions is salient (e.g., trauma-exposed populations; Weiss et al., 2018). By treating substance use stigma and emotion dysregulation as broader constructs that encompass multiple interrelated processes, the present research provides compelling evidence supporting these constructs’ utility in predicting depressive symptoms. Future research would benefit from taking a more nuanced approach to studying stigma and emotion dysregulation by elucidating the unique contributions of their individual components in relation to various mental and behavioral health outcomes.

The current findings also highlight the value of addressing emotion dysregulation as a promising treatment target in substance use stigma coping interventions. Given that both negative and positive emotion dysregulation have been shown to drive a wide range of clinical difficulties (Gratz & Tull, 2010; Weiss et al., 2019), interventions that target emotion dysregulation can potentially shape outcomes beyond depressive symptoms, such as substance use behaviors and treatment engagement. Indeed, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which focuses on facilitating emotion regulation via mindfulness and acceptance, has demonstrated initial promise in reducing internalized stigma as well as improving psychosocial functioning and treatment retention among patients in a residential substance use treatment program (Luoma et al., 2008, 2012). Future research is needed to assess the efficacy of emotion-regulation-focused interventions such as ACT with more diverse substance-using populations, including trauma-exposed individuals. Researchers could also explore the feasibility of incorporating stigma coping and mindfulness exercises into standard substance use prevention and treatment interventions (e.g., motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy).

Of note, our findings, alongside a rich body of research linking a wide array of stressors (e.g., acculturation [Paulus et al., 2019], childhood adversity [Weiss et al., 2013], domestic violence [Weiss et al., 2018]) to emotion dysregulation, suggest that emotion dysregulation may constitute a vulnerability factor for negative consequences of stress, including stigma-related sequelae. More research is needed to elucidate the relative impact of stigma on emotion dysregulation in the context of other general life stressors. Additionally, future work could also examine the possibility that emotion dysregulation might influence the strength and/or direction (i.e., moderate) the association between stigma-related stressors and depressive symptoms. Findings from these follow-up studies will further clarify the role of emotion dysregulation as a transdiagnostic treatment target and provide insights on who might particularly benefit from stigma coping interventions.

The present investigation has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of our data precluded predictive, causal conclusions. In particular, whereas our conceptualization of substance use stigma as a predictor of emotion dysregulation and depressive symptoms is well-grounded in the theoretical literature (Ahern et al., 2007; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Link et al., 1997), it is also possible that individuals with higher levels of depressive symptoms would be more inclined to report emotion regulation difficulties and stigma-related experiences. Although we were able to demonstrate statistically that our hypothesized model was superior than this possible alternative, future research using prospective designs is needed to clarify the relations among these constructs and elucidate the long-term, causal impact of substance use stigma on well-being. Relatedly, we relied on trait measures of substance use stigma, emotion dysregulation, and depressive symptoms in the present research. Experience sampling studies that assess behaviors and experiences in real time will clarify whether emotion dysregulation is more likely to manifest following experiences of substance use-related discrimination and subsequently lead to exacerbation of depressive symptoms.

Second, while utilization of a sample of substance-using, trauma-exposed individuals is a strength of the current study and represents an important contribution to the existing literature, our findings may not generalize to other samples, and thus require replication. For instance, trauma-exposed individuals are at increased risk for developing negative consequences from substance use (Debell et al., 2014), and thus experiences of substance use stigma in this population—including its prevalence, development, and relation to clinically relevant outcomes—may diverge from other populations. Further, consistent with the inclusion criteria of the larger study on which the current investigation is based (i.e., engagement in at least one instance of alcohol/drug use in the past 30 days), our sample includes participants with varying severities of substance use, many of whom might experience significantly less stigmatization than individuals who are diagnosed with substance use disorders. Finally, because participants for the current study were recruited on-line via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, our sample was relatively homogeneous, with most of the participants being White and well-educated. Future research should carefully examine the generalizability of our findings to other samples, such as individuals who are currently receiving substance use treatment and individuals from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Lastly, we recognize that emotion dysregulation likely represents one of the many pathways through which substance use stigma operates to undermine mental health. More research is needed to identify other potential mechanisms underlying the association between substance use stigma and depressive symptoms, such as lack of perceived social support (Birtel et al., 2017) and maladaptive coping strategies (Wang et al., 2018). Future studies could also examine how substance use stigma might operate through emotion dysregulation to shape other aspects of well-being beyond depression, such as self-esteem, treatment adherence, and overall quality of life.

In sum, the present research contributes to the existing literature by providing initial support for the role of emotion dysregulation, which encompasses difficulties in the regulation of both negative and positive emotions, as a mechanism underlying the association between substance use stigma and depressive symptoms among substance-using, trauma-exposed community individuals. Further, findings underscored the potential utility of targeting emotion dysregulation in intervention efforts that are designed to facilitate stigma coping among individuals who use alcohol and/or drugs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health awarded to Katie Wang (K01DA045738) and Nicole H. Weiss (K23DA039327, P20GM125507), as well as a grant awarded to Devon L. Quinn from the University of Rhode Island Undergraduate Research and Innovation Committee.

References

- Ahern J, Stuber J, & Galea S (2007). Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2–3), 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtel MD, Wood L, & Kempa NJ (2017). Stigma and social support in substance abuse: Implications for mental health and well-being. Psychiatry Research, 252,1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjureberg J, Ljótsson B, Tull MT, Hedman E, Sahlin H, Lundh L-G, Bjärehed J, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore T, Gumpert CH, & Gratz KL (2016). Development and validation of a brief version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: The DERS-16. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, & Gosling SD (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S, & Toneatto T (1993). Barriers to treatment: Why alcohol and drug abusers delay or never seek treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 18(3), 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, & Finch JF (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Uezato A, Newell JM, & Frazier E (2008). Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 21(1), 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing RL, Stuewig J, & Tangney JP (2005). On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 30(7), 1392–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, Batt-Rawden S, Greenberg N, Wessely S, & Goodwin L (2014). A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(9), 1401–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, & Copenhaver MM (2013). HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS and Behavior, 17(5), 1785–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, & Kaplan K (2004). Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(8), 807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Tull MT (2010). Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance-and mindfulness-based treatments. In Baer RA (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change (pp. 107–133). Context Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & Levenson R (1997). Hiding feelings: The acute effects of inhibiting positive and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(1), 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2008). Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(12), 1270–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Dovidio J (2009). How does stigma “get under the skin”?: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20(10), 1282–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, McKay L, & Aronson J (2006). Stigma as ego depletion: How being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychological Science, 17(3), 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ 9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza M, Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Osilla KC, & Ewing B (2017). Internalized stigma as an independent risk factor for substance use problems among primary care patients: Rationale and preliminary support. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180,52–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, & Nuttbrock L (1997). On stigma and its consequences: Evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(2), 177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Bunting K, & Rye AK (2008). Reducing self-stigma in substance abuse through acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, manual development, and pilot outcomes. Addiction Research & Theory, 16(2), 149–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, & Fletcher L (2012). Slow and steady wins the race: A randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(1), 43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Pettinati HM, Morrison R, Feeley M, Mulvaney FD, & Gallop R (2002). Relation of depression diagnoses to 2-year outcomes in cocaine-dependent patients in a randomized continuing care study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16(3), 225–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade AW, & Craig SB (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 437–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Polanco-Roman L, Tsypes A, & Valderrama J (2013). Perceived discrimination, ruminative subtypes, and risk for depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(4), 395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, & Carleton RN (2017). Use of online crowdsourcing platforms for gambling research. International Gambling Studies, 17(1), 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer DM, Meyvis T, & Davidenko N (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 867–872. [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Restar A, Ventuneac A, Grov C, & Parsons JT (2015). A minority stress-emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychology, 34(8), 829–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus DJ, Rodriguez-Cano R, Garza M, Ochoa-Perez M, Lemaire C, Bakhshaie J, Viana AG, & Zvolensky MJ (2019). Acculturative stress and alcohol use among Latinx recruited from a primary care clinic: Moderations by emotion dysregulation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(5), 589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, Marx BP, Kimerling R, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Kaloupek DG, Schnurr PP, Kaiser AP, Leyva YE, & Tiet QQ (2016). The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(10), 1206–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Gamarel KE, Pachankis JE, Ventuneac A, Grov C, & Parsons JT (2017). Extending the minority stress model to incorporate HIV-positive gay and bisexual men’s experiences: A longitudinal examination of mental health and sexual risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 147–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytwinski NK, Scur MD, Feeny NC, & Youngstrom EA (2013). The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(3), 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption—II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick MR, Weiss NH, Contractor A, Dixon-Gordon KL, & Spillane NS (2019). Depression and risky alcohol use: An examination of the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in trauma-exposed individuals. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(3), 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Grant I, & Patterson TL (2005). Utilization of drug treatment programs by methamphetamine users: The role of social stigma. The American Journal on Addictions, 14(4), 367–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DN, Chandler J, & Mueller PA (2013). Using Mechanical Turk to study clinical populations. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(2), 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1982). The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors, 7(4), 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LR, Earnshaw VA, Copenhaver MM, & Cunningham CO (2016). Substance use stigma: Reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162,34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Timmins L, Rimes KA, & Rahman Q (2020). Minority stressors, rumination, and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 661–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, & Feldman Barrett L (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1161–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Burton CL, & Pachankis JE (2018). Depression and substance use: Towards the development of an emotion regulation model of stigma coping. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(5), 859–866. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1391011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Darosh AG, Contractor AA, Schick MR, & Dixon-Gordon KL (2019). Confirmatory validation of the factor structure and psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Positive. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(7), 1267–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Dixon-Gordon KL, Peasant C, & Sullivan TP (2018). An examination of the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(5), 775–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Gratz KL, & Lavender J (2015). Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior Modification, 39(3), 431–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Lavender J, & Gratz KL (2013). Role of emotion dysregulation in the relationship between childhood abuse and probable PTSD in a sample of substance abusers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(11), 944–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]