Abstract

Recurrent miscarriage (RM) affects approximately 1%–5% of couples worldwide. Due to its complicated etiologies, the treatments for RM also vary greatly, including surgery for anatomic factors such as septate uterus and uterine adhesions, thyroid modulation drugs for hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, and aspirin and low molecular weight heparin for antiphospholipid syndrome. However, these treatment modalities are still insufficient to solve RM. Omega‐3 fatty acids are reported to modulate the dysregulation of immune cells, oxidative stress, endocrine disorders, inflammation, etc., which are closely associated with the pathogenesis of RM. However, there is a lack of a systematic description of the involvement of omega‐3 fatty acids in treating RM, and the underlying mechanisms are also not clear. In this review, we sought to determine the potential mechanisms that are highly associated with the pathogenesis of RM and the regulation of omega‐3 fatty acids on these mechanisms. In addition, we also highlighted the direct and indirect clinical evidence of omega‐3 fatty acid supplements to treat RM, which might encourage the application of omega‐3 fatty acids to treat RM, thus improving pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: endocrine disorder, immunity, omega‐3 fatty acid, oxidative stress, recurrent miscarriage

We highlighted the direct and indirect clinical evidence of omega‐3 fatty acid supplements to treat RM, which might encourage the application of omega‐3 fatty acids to treat recurrent miscarriage, thus improving their pregnancy outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Recurrent miscarriage (RM) is a critical disorder of pregnancy that affects approximately 1%–5% of couples worldwide (Dimitriadis et al., 2020). The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has defined RM as three or more spontaneous miscarriages, while the American Society of Reproductive Medicine and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology both defined RM as two or more failures of pregnancy (ESHRE Guideline Group on RPL, 2018; Green & O'Donoghue, 2019; Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2012). The potential etiologies of RM are quite complex and include male factors (such as male partner's sperm quantity, sperm quality, and genetic mutations), and genetic abnormality, anatomic issues, and immune disorders (Deshmukh & Way, 2019; Quenby et al., 2021; Yu & Bao, 2022). Therefore, the treatment of RM also varies greatly and includes surgery, immunotherapies, anticoagulants, endocrine therapies, etc. (Deng et al., 2022; Uthman et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2014). However, current management is still insufficient to solve RM.

Omega‐3 fatty acids are a group of polyunsaturated fatty acids that mainly refer to α‐linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in terms of human physiology (Bradberry & Hilleman, 2013; Brinton & Mason, 2017). ALA, merely obtained from the diet, can be metabolized into EPA and DHA in humans, but the metabolized EPA and DHA are insufficient due to dietary habits (Bradberry & Hilleman, 2013). Therefore, it is important to directly take in EPA and DHA from dietary sources, such as fish oil and other sea foods (DiNicolantonio & O'Keefe, 2020). In terms of RM, there is some evidence suggesting the potential involvement of omega‐3 fatty acids in treating or preventing RM (Carta et al., 2005; Lazzarin et al., 2009; Rossi & Costa, 1993). In addition, omega‐3 fatty acids possess anti‐inflammatory, immune‐modulatory, and endocrine‐modulatory effects, which could possibly affect RM (Di Bari et al., 2017; Dimitriadis et al., 2020; Rees et al., 2022; Singh, 2020; Tajuddin et al., 2016). However, there is no general consensus on the benefits of omega‐3 fatty acid supplements in treating RM as well as the fundamental mechanism of omega‐3 fatty acids in disputing RM. This study aimed to review the potential involvement of omega‐3 fatty acids in RM.

2. CURRENT OPINIONS ON RM

2.1. Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment

RM is known for hampering the productivity of humans, and it also places huge stress on patients. It has been reported that couples, especially women with RM, bear huge psychological stress (Banno et al., 2020). The average prevalence of women with one previous miscarriage is 10.8%, that of women with two miscarriages is 1.9%, and that of women with three or more miscarriages is 0.7% in the West (Quenby et al., 2021). Taking the definition of RM as two or more previous miscarriages, the prevalence of miscarriage is obtained to be 2.6% in the West. However, the incidence of RM varies among regions and is reported to be 1%–5% (Dimitriadis et al., 2020; Quenby et al., 2021). Even worse, studies conducted in developing countries are lacking; thus, the actual data might vary. In the past few decades, several risk factors for RM have been identified. For instance, previous times of miscarriage is a critical risk factor for RM; individuals who experience six or more miscarriages face a nearly 60% risk of further miscarriage (Coomarasamy et al., 2020). Age is also a well‐recognized risk factor; individuals with an age range of 20–29 years have a lower risk of RM, while those with an age below 20 or above 30 have a higher risk of RM (Dimitriadis et al., 2020; Quenby et al., 2021). Other typical risk factors include obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30], stress, smoking, high caffeine or alcohol intake during the first trimester, thyroid dysfunction, polycystic ovary syndrome, antiphospholipid syndrome, etc. (Chakraborty et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2020; Sugiura‐Ogasawara, 2015; Uthman et al., 2019).

The treatments of RM rely on the etiologies of RM, which vary greatly and mainly include anatomic factors, endocrine factors, immune factors, etc. Regarding the common anatomic factors of RM, such as septate uterus and uterine adhesions, they can be treated with surgery. For instance, a meta‐analysis suggests that RM caused by a septate uterus can be managed by hysteroscopic metroplasty, although there exists a potential risk of postoperative complications (Valle & Ekpo, 2013). For patients with RM induced by uterine adhesions, hysteroscopic adhesiolysis is the common surgical management, combined with antiadhesion barriers if needed (Vitale et al., 2022).

Hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and polycystic ovary syndrome are common endocrine etiologies of RM (Amrane & McConnell, 2019). The treatment of RM due to hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism mainly includes antithyroid drugs (such as propylthiouracil and methimazole) and levothyroxine (Negro & Stagnaro‐Green, 2014). However, the dose of these agents should be carefully adjusted. In terms of polycystic ovary syndrome, the currently recommended management includes improvement of dietary intake, more physical activities, and weight control (Akre et al., 2022). In addition, metformin is also recommended to assist in weight management and insulin resistance (Zhao & He, 2022).

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a well‐recognized immune etiology of RM that affects approximately 15%–30% of patients with RM (Schreiber et al., 2018). Currently, aspirin (75–100 mg/day) or low molecular weight heparin (dosage not mentioned) is recommended to manage antiphospholipid syndrome in patients with RM (ESHRE Guideline Group on RPL et al., 2018). Recently, several meta‐analyses revealed that the combination of aspirin and low molecular weight heparin may improve the live birth rate compared with patients that received aspirin only (Hamulyak et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020).

However, the etiologies of approximately 50% of RM are still unclear (Tur‐Torres et al., 2017). Generally, several factors, including trophoblast dysfunction and relevant signaling pathways, genetic polymorphism, and immune dysfunction, may contribute to the pathogenesis of RM. Unfortunately, the treatment of patients with RM of unknown etiology remains unsatisfactory.

2.2. Underlying mechanisms

2.2.1. Trophoblast dysfunction and relevant signaling pathways

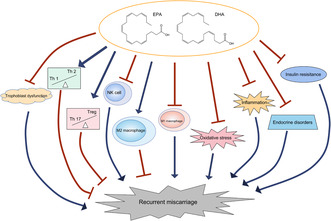

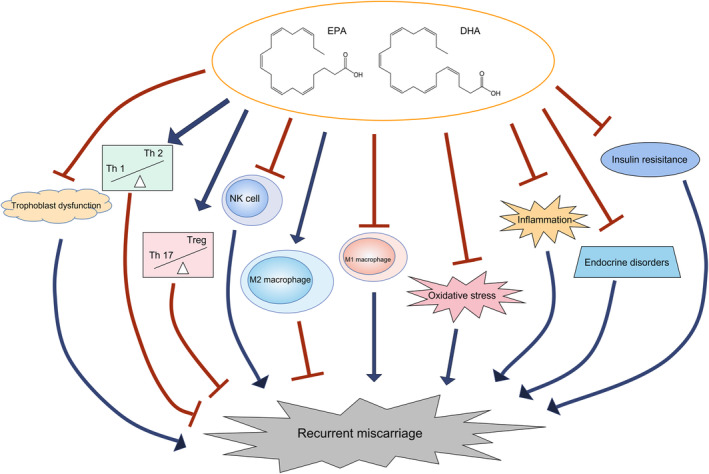

Previous studies have implied that trophoblast dysfunction is considered an underlying reason for miscarriage (Knofler et al., 2019). For instance, one study suggests that a low level of insulin‐like growth factor‐binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), a member of the IGFBP family that regulates cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation, is noted in specimens of patients with RM, and knockdown of IGFBP7 inhibits matrix metalloproteinase 2 and Slug (a widely expressed transcriptional regulator belonging to the Snail family of zinc finger transcription factors) levels via the insulin growth factor‐1 receptor (IGF‐1R)‐mediated c‐Jun signaling pathway to reduce trophoblast invasion, thus inducing miscarriage (Wu et al., 2022). Another study proposed that wingless/integrated (WNT) family member 16 (WNT16) promotes the survival and invasion of trophoblasts through the Akt/β‐catenin signaling pathway (Li, Shi, et al., 2022). In addition, it has been reported that long noncoding RNA‐HZ04 (lncRNA‐HZ04) binds with microRNA‐HZ04 (miR‐HZ04) to affect the stability of type 1 inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptor (IP3R1), subsequently activating the Ca2+‐mediated IP3R1/phospho‐calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II (p‐CMKII)/β‐sarcoglycan (SGCB) signaling pathway, thus increasing trophoblast apoptosis. Moreover, psoralen, a phytochemical compound that is traditionally used for treating psoriasis combined with ultraviolet, promotes the viability and invasion ability of trophoblasts and elevates the expression and activity of MMP‐2 and MMP‐9, as well as the nuclear accumulation and translocation of p65, suggesting that psoralen protects miscarriage by activating the nuclear factor‐κB pathway (Qi et al., 2022). Indeed, regulating trophoblast dysfunction and the underlying molecular mechanisms has become a research hotspot in recent years. It could be assumed that this research field may identify potential treatment targets and generate novel treatment options for RM in the near future; however, further validation is still needed (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The hypothesized mechanism of omega‐3 fatty acids in treating RM.

2.2.2. Genetic polymorphism

In recent years, studies have focused on the genetic risk factors for RM. For instance, Kwon et al. (2022) evaluated 388 patients with RM and 280 controls in Korea and revealed that the rs10515478 C>G polymorphism of the SMAD5 gene and the rs1046875 G>A polymorphism of the fructosamine 3 kinase‐related protein (FN3KRP) gene are associated with a lower risk of RM. A study conducted by Talwar et al. (2022) suggests that the 844INS68 polymorphism of cystathionine beta‐synthase (CBS) combined with the A2756G polymorphism of 5‐methytetrahydrofolate‐homocysteine methyltransferase (MTR) is associated with over 2‐fold increased RM risk. Salimi et al. (2020) presented a meta‐analysis including 31 case–control studies and revealed that 174 G>C and 634 G>C polymorphisms of the interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) gene and 137 G>C polymorphisms of the IL‐18 gene are associated with a higher risk of RM. Another meta‐analysis including 18 case–control studies conducted by Su et al. (2011) indicated that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 1154 G>A and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) Glu298Asp polymorphisms are closely associated with the risk of RM. These studies have highlighted the potential genetic risk factors for RM. However, more studies are encouraged to achieve a deep understanding of RM.

2.2.3. Immunity, oxidative stress, and inflammation in RM

The dysregulation of immunity, existence of oxidative stress, and high level of inflammation are thought to be key parameters in the pathogenesis of RM (Figure 1). Immune cells such as natural killer (NK) and T cells have a great impact on RM. A previous study disclosed a high cytotoxic activity of NK cells in RM patients in the luteal phase, which suggests that NK cell cytotoxic activity is responsible for pregnancy loss in patients with RM (Sokolov et al., 2019). Another study revealed that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α+/CD56+ NK cells are associated with the risk of pregnancy loss in RM patients (Takeyama et al., 2021). A recent study identified a novel subset of NK cells, CXCR4+ CD56bright decidual NK cells, which are insufficiently expressed in RM patients and RM model mice; in addition, adoptive transfer of these cells to NK cell‐deficient mice improves pregnancy outcomes (Tao et al., 2021). Notably, several studies conducted with a mouse model of RM suggested that the modulation of NK cells in abortion‐prone mice is able to promote pregnancy outcomes (Li et al., 2017; Nagamatsu et al., 2018; Rezaei Kahmini et al., 2020; Tanaka et al., 2016). T cells are also critical modulators of immunity. For instance, the adoption of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells reduces abortion in RM mice (Wang et al., 2019). Meanwhile, it has also been reported that the polarization of T cells toward T‐helper (Th)2 cells promotes pregnancy maintenance in abortion‐prone mice (Li, Sun, et al., 2022). In patients with RM, it is reported that the Th1/Th2 ratio is increased (Kuroda et al., 2021). Another study suggests that the Treg/Th17 ratio is significantly decreased in patients with RM compared to individuals with normal pregnancies (Ji et al., 2019). In terms of macrophages, it is suggested that the promotion of autophagy and cell resistance in decidual macrophages improves pregnancy maintenance in RM model mice (Yang et al., 2022). In addition, a higher level of M1 polarization of macrophages prevents pregnancy loss in RM model mice (Cui et al., 2021). Clinically, apoptosis and efferocytosis are higher in the macrophages of RM patients than in those of normal pregnancies (Sheng et al., 2022). In addition, M1 macrophages are abundant, but M2 macrophages are insufficient in the deciduae of patients with RM compared to those with normal pregnancies (Tsao et al., 2018).

Oxidative stress, caused by the imbalance of peroxidants and antioxidants, participates in various pathological processes, including RM. A previous study suggests that the levels of heat shock protein 70, nitrotyrosine, and lipid peroxidation are all elevated in placental tissues from miscarriages compared with those from normal pregnancies (Hempstock et al., 2003). The high level of oxidative stress hampers placental development, which induces pregnancy loss (Gupta et al., 2007). Clinically, numerous studies have implied that the level of oxidative stress is associated with RM. For instance, total antioxidant capacity is significantly decreased in RM patients, while the level of a DNA damage marker related to oxidative stress, 8‐hydroxydeoxyguanosine, is increased in RM patients (Alrashed et al., 2021). Other markers of oxidative stress, including oxidized glutathione (Ghneim & Alshebly, 2016), malondialdehyde (Al‐Sheikh et al., 2019), and nitric oxide (NO; Raffaelli et al., 2010), are all increased, but the levels of antioxidants, including superoxide dismutase (Ghneim et al., 2016) and glutathione (Ghneim & Alshebly, 2016), are decreased in RM patients.

The high level of inflammation may induce apoptosis in trophoblast cells, which could result in pregnancy loss (Alfian et al., 2022; Yougbare et al., 2017). Meanwhile, the levels of inflammatory cytokines can be modulated by immune cells such as NK cells and Th cells. As mentioned earlier, these immune cells critically modulate RM; thus, inflammatory cytokines also participate in the pathogenesis of RM. On the other hand, inflammation also regulates insulin resistance, obesity, and polycystic ovary syndrome, which are known factors associated with RM (Chakraborty et al., 2013; Sugiura‐Ogasawara, 2015). Indeed, clinical studies have reported the dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines in patients with RM (Lob et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021; Qian et al., 2018).

3. POTENTIAL INVOLVEMENT OF OMEGA‐3 FATTY ACIDS IN RM

Omega‐3 fatty acids are a group of polyunsaturated fatty acids that exert multiple biological functions, such as regulating cell survival, inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress, modulating immunity, and modifying the endocrine system.

3.1. Omega‐3 fatty acids regulate trophoblast dysfunction

Trophoblast dysfunction is critically associated with RM. According to some previous studies, omega‐3 fatty acids exert regulatory effects on trophoblast dysfunction. For instance, DHA (25 μM) attenuated lipopolysaccharide‐induced inflammation in trophoblast cell lines and decreased the preterm delivery of pregnant mice treated with LPS (Chen et al., 2018). A previous study suggested that DHA (12.5–100 μM) promoted the tube length and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor in a trophoblast cell line in a dose‐dependent manner (Johnsen et al., 2011). Similar findings were also reported in another study (Basak & Duttaroy, 2013). It has also been reported that 100 mM DHA significantly induced oxidative stress in a trophoblast cell line, while 1 and 10 mM DHA markedly decreased oxidative stress; pretreatment with 1 and 10 mM DHA also promoted the survival rate of trophoblasts under oxidative stress induced by H2O2 treatment (Shoji et al., 2009). These studies suggested the protective effect of DHA on trophoblast dysfunction, while the evidence of EPA on this is relatively lacking.

3.2. Omega‐3 fatty acids modulate immunity

Accumulating evidence has shown that omega‐3 fatty acids exert an immunoregulatory effect. One study showed that a fish oil‐enriched diet (4.0 g EPA and 2.9 g DHA per kg diet) increased CD11B+CD27− NK cells, CD107a+ NK cells, and CCR5+ NK cells after inflammation induction in mice (Jensen et al., 2022). In cancers, the activity of NK cells is inhibited (Seliger & Koehl, 2022). Exosomes from an omega‐3 fatty acid (12.5 μM EPA or DHA)‐treated multiple myeloma cell line (L363) were able to restore the activity of NK cells (NK‐92; Moloudizargari et al., 2020). In addition, it has also been reported that a daily omega‐3 fatty acid‐enriched diet (containing 1 g omega‐3 fatty acid) for 6 months reduced NK cell numbers and resulted in lower inflammation in healthy subjects (Mukaro et al., 2008). Although no studies have revealed the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids under RM conditions, it is assumed that they might also restore NK cells to a normal level.

The regulatory effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on T cells has been reported by a number of studies. It has been suggested that an omega‐3 fatty acid‐enriched diet (containing 5% omega‐3 fatty acids) increased CD4+Foxp3+ and CD4+Foxp3+CD25+ Tregs that suppress inflammation in mice; mechanically, omega‐3 fatty acid reduced Erk and Akt phosphorylation (Camacho‐Munoz et al., 2022). Meanwhile, another study revealed that compared with a high‐fat diet, ex vivo coculture of primary mouse CD4+ T cells with adipocytes from mice consuming high‐fat plus omega‐3 fatty acid (containing 5.3% kcal from menhaden fish oil) reduced Th1‐related cytokines but increased Th2‐related cytokines and lowered the level of the NOD‐like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome (Liddle et al., 2021). Moreover, supplementation with ALA, EPH, or DHA (100 μM) in a coculture system of human adipose‐derived stem cells from obese and human mononuclear cells inhibited interleukin (IL)‐17, which is mainly secreted by Th17 cells (Chehimi et al., 2019).

In terms of the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on macrophages, one study reported that in healthy human‐derived macrophages cultured with a differentiation medium containing omega‐3 fatty acids (20 μM), M1 macrophage differentiation was suppressed, but M2 macrophage differentiation was promoted (Schwager et al., 2022). Another study revealed that omega‐3 fatty acid (25 μM) reduced the production of NO and alleviated the level of inflammatory status in macrophages from type 1 diabetes mellitus mice (Davanso et al., 2021). Similar findings were observed in macrophages from patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm, in which ex vivo omega‐3 fatty acids (20 and 80 μM) reduced the production of proinflammatory cytokines in these macrophages (Meital et al., 2019).

Although these studies have indicated the regulation of omega‐3 fatty acids in immunity, it should be considered that the immune condition between RM and the circumstances above (such as inflammation, diabetes mellitus, and abdominal aortic aneurysm) may vary to some extent. Thus, the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on immunity in patients with RM still needs further verification.

3.3. Omega‐3 fatty acids modulate oxidative stress

Several studies have disclosed the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on oxidative stress. One study reported that consuming a diet enriched with omega‐3 fatty acids (containing 2.68% EPA and 3.17% DHA) for3 months reduced the level of thiobarbituric acid–reactive substances, a lipid peroxidation marker, in police dogs; meanwhile, the activity of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) was elevated compared with dogs consuming a normal diet (Ravic et al., 2022). Another study administered DHA‐enriched fish oil (450 mg/kg body weight twice daily) to stress‐induced brain oxidative stress model mice; the authors disclosed a lower level of serum lipid peroxidation and a higher level of serum total antioxidant capacity (Asari et al., 2022). Meanwhile, in rats fed a high‐fat diet, the addition of omega‐3 fatty acids (50.79 mol% DHA + EPA) reduced lipid peroxidation levels and increased GPx activity (Miralles‐Perez et al., 2021). One previous study explored the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on oxidative stress under the scenario of cigarette smoke (Wiest et al., 2017). The authors fed the mice a control diet or omega‐3 fatty acid diet (containing 1.8% ALA, 16.0% EPA, and 10.8% DHA) for 8 weeks and then exposed the mice to cigarette smoke for 5 days, 2 h per day. Cigarette smoke‐induced oxidative stress markers were significantly reduced in mice fed an omega‐3 fatty acid diet compared with mice fed a control diet (Wiest et al., 2017). A recent meta‐analysis reviewed 39 trials with 2875 subjects who either consumed omega‐3 fatty acid supplements or placebo (Heshmati et al., 2019). The pooled analysis showed that total antioxidant capacity, GPx, and reduction of malondialdehyde were significant in participants who received omega‐3 fatty acid supplements compared with those who received placebo; however, the changes in NO, glutathione, superoxide dismutase, and catalase activities were not significant between participants receiving different supplements (Heshmati et al., 2019). However, the molecular mechanisms by which omega‐3 fatty acids regulate oxidative stress are still not clear and require further exploration.

3.4. Omega‐3 fatty acids modulate the endocrine system

There is some evidence suggesting that omega‐3 fatty acids are able to modulate endocrine function. For instance, a randomized, controlled trial revealed that in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome, omega‐3 fatty acid (2000 mg/day omega‐3 fatty acids) combined with vitamin D (50,000 IU every 2 weeks) reduced the level of testosterone, ameliorated inflammation, improved total antioxidant capacity, and promoted mental health compared with placebo (Jamilian, Samimi, Mirhosseini, Afshar Ebrahimi, Aghadavod, Talaee, et al., 2018). Similar findings have also been reported in other randomized controlled trials (Amini et al., 2018; Rahmani et al., 2017; Sadeghi et al., 2020). Meanwhile, a recent meta‐analysis included 10 observational studies and revealed that omega‐3 fatty dietary intake reduced the risk of endocrine‐related cancers, such as ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer (Hoang et al., 2021). Moreover, one study reported that in rats with hyperthyroidism‐induced hepatic dysfunction, supplementation with omega‐3 fatty acids (3 g/kg/day containing 18% EPA and 12% DHA) plus L‐thyroxine decreased the serum level of triiodo‐l‐thyronine compared with L‐thyroxine alone; the authors also illustrated that the total antioxidant capacity and inflammation level were reduced by omega‐3 fatty acids plus L‐thyroxine compared with L‐thyroxine alone (Gomaa & Abd El‐Aziz, 2016). Considering that the pathogenesis of RM is closely associated with endocrine dysfunction, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism. (Amrane & McConnell, 2019), it is likely that omega‐3 fatty acids might modulate RM through endocrine regulation. However, there is no direct evidence illustrating the regulation of omega‐3 fatty acids in the RM‐related endocrine system, which should be explored in the future.

4. CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE OF OMEGA‐3 FATTY ACID SUPPLEMENTS IN RM

Until now, some clinical studies have implied the effect of omega‐3 fatty acid supplements in RM. The direct evidence that omega‐3 fatty acids are used to treat RM is quite limited (Table 1). However, there are some studies indicating that omega‐3 fatty acid supplements could modulate inflammation, insulin resistance, thyroid antibodies, and oxidative stress in pregnant women, which, as mentioned above, is deeply associated with RM (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Direct evidence from clinical studies indicating the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on RM.

| References | Study design | Participants | Grouping | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lazzarin et al. (2009) | Randomized, controlled trial | 60 RM patients |

Aspirin (100 mg daily) (N = 20) Omega‐3 fatty acids (4 g daily) (N = 20) Aspirin (100 mg daily) plus omega‐3 fatty acids (4 g daily) (N = 20) |

Aspirin plus omega‐3 fatty acids group had the highest uterine blood flow index |

| Carta et al. (2005) | Prospective study | 30 RM patients with antiphospholipid syndrome |

Aspirin (100 mg daily) (N = 15) Fish oil derivate (4 g daily) (N = 15) |

Live birth rate, gestational age at delivery, fetal birth weight, cesarean sections, and complications were comparable between groups |

| Rossi and Costa (1993) | Prospective study | 22 RM patients | All received EPA and DHA (5.1 g daily, ratio: 1.5) | Of 23 pregnancies, 19 ended at the 37th week producing a baby, 1 was going on at 32nd week, 2 pregnancies ended with cesarean section for preeclampsia at 30th and 35th week, and 1 intrauterine fetal death at the 27th week |

Abbreviations: CRP, C‐reactive protein; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; RM, recurrent miscarriage.

TABLE 2.

Indirect evidence from clinical studies indicating the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on RM.

| References | Study design | Participants | Grouping | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sley et al. (2020) | Prospective study | 725 pregnant women |

Omega‐3 fatty acid supplement (dose not clear) (N = 165) No omega‐3 fatty acid supplement (N = 560) |

Omega‐3 fatty acid supplement was associated with 10.2% lower levels of 8‐iso‐PGF2α and 10.3% lower levels of the metabolite |

| Jamilian, Samimi, Mirhosseini, Afshar Ebrahimi, Aghadavod, Taghizadeh, et al. (2018) | Randomized, controlled trial | 40 women with gestational diabetes mellitus |

Fish oil capsule containing DHA (180 mg) and EPA (120 mg) twice daily (N = 20) Placebo (N = 20) |

Fish oil supplement reduced mRNA levels of PPAR‐γ, LDLR, IL‐1, and TNF‐α in PBMCs |

| Kajarabille et al. (2017) | Randomized, controlled trial | 110 pregnant women |

Control dairy drink (N = 54) Fish oil‐enriched (containing 320 mg DHA and 72 mg EPA) dairy drink daily (N = 56) |

Fish oil supplement increased superoxide dismutase and catalase at delivery and after 2.5 months |

| Razavi et al. (2017) | Randomized, controlled trial | 120 women with gestational diabetes mellitus |

Omega‐3 fatty acid (1000 mg twice daily) (N = 30) Vitamin D (50,000 IU every 2 weeks) (N = 30) Omega‐3 fatty acid (1000 mg twice daily) + vitamin D (50,000 IU every 2 weeks) (N = 30) Placebo (N = 30) |

Omega‐3 fatty acid plus vitamin D reduced high‐sensitivity CRP while increased total antioxidant capacity and glutathione; it also decreased the incidences of newborns' hyperbilirubinemia and hospitalization compared with other treatments |

| Benvenga et al. (2016) | Prospective study | 236 thyroid disease‐free women |

Swordfish (equivalent to 6.3 ± 2.1 g DHA + EPA monthly) (N = 48) Oily fish (equivalent to 13.2 ± 5.4 g DHA + EPA monthly) (N = 52) Swordfish+other fish (equivalent to 6.0 ± 2.8 g DHA + EPA monthly) (N = 68) Fish other than swordfish and oily fish (equivalent to 5.1 ± 3.8 g DHA + EPA monthly) (N = 68) |

Positive rates and serum concentrations of thyroglobulin and thyroperoxidase antibodies were the lowest in oily fish group |

| Taghizadeh et al. (2016) | Randomized, controlled trial | 60 women with gestational diabetes mellitus |

Omega‐3 fatty acid (1000 mg daily) plus vitamin E (400 IU daily) (N = 30) Placebo (N = 30) |

Omega‐3 fatty acid plus vitamin E had beneficial effect on fasting plasma glucose, serum insulin concentration, and serum lipids |

| Jamilian et al. (2016) | Randomized, controlled trial | 60 women with gestational diabetes mellitus |

Omega‐3 fatty acid (1000 mg daily) + vitamin E (400 IU daily) (N = 30) Placebo (N = 30) |

Omega‐3 fatty acid promoted total antioxidant capacity but did not affect high‐sensitivity CRP; it also decreased hyperbilirubinemia incidence in newborns |

| Haghiac et al. (2015) | Randomized, controlled trial | 49 obese pregnant women |

DHA plus EPA (2 g daily) (N = 25) Placebo (N = 24) |

DHA plus EPA treatment reduced plasma CRP and TLR4 in adipose and placental |

| Samimi et al. (2015) | Randomized, controlled trial | 56 women with gestational diabetes mellitus |

DHA plus EPA (1000 mg daily) (N = 28) Placebo (N = 28) |

DHA plus EPA resulted in a greater serum insulin change and lower high‐sensitivity CRP, but did not affect fasting plasma glucose and lipid profiles |

Abbreviations: CRP, C‐reactive protein; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; IL‐1, interleukin‐1; LDLR, low‐density lipoprotein receptor; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PGF2α, prostaglandin F2α; PPAR‐γ, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma; RM, recurrent miscarriage; TLR4, toll‐like receptor 4; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α.

4.1. Direct evidence

The direct evidence of omega‐3 fatty acids in treating RM is quite limited. In a randomized controlled trial, RM patients with impaired uterine perfusion were assigned to receive daily 100 mg of aspirin, daily 4 g of omega‐3 fatty acids, or daily 100 mg of aspirin plus 4 g of omega‐3 fatty acids. The results revealed that after 2 months of intervention, the uterine artery pulsatility index was increased in all three groups, which suggests that omega‐3 fatty acids may serve as a therapeutic agent for RM due to impaired uterine perfusion (Lazzarin et al., 2009). However, the sample size of this study was not large enough (N = 20 in each group), and blinding was not mentioned. Additionally, this study does not investigate the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on live birth, a critical pregnancy outcome in patients with RM. Another prospective study enrolled 30 RM patients with antiphospholipid syndrome who either received low‐dose aspirin or omega‐3 fatty acids. The findings indicate that the live birth rate was 80% (12/15) in the aspirin group and 73.3% (11/15) in the omega‐3 fatty acid group (p > .05). In addition, the gestation duration and fetal birth weight were both similar between groups (Carta et al., 2005). However, the small sample size of this study may result in low statistical power and affect the reliability of the findings. Moreover, a prospective study enrolled 22 RM patients with antiphospholipid syndrome who were treated with fish oil, which was equivalent to 5.1 g of omega‐3 fatty acids. After 3 years of intervention, only one fetal death occurred at the 27th week of gestation. The other 21 pregnancies end with babies of good health (Rossi & Costa, 1993). Again, the sample size of this study is small, and there lacks a control cohort. These studies indicate that omega‐3 fatty acids possess treatment potential for RM. However, the sample sizes of these studies are generally small. Thus, more studies are required to further verify the therapeutic efficacy of omega‐3 fatty acids in patients with RM.

4.2. Indirect evidence

There is also some indirect evidence indicating the potential of omega‐3 fatty acid supplements for the treatment of RM. For example, a randomized controlled trial analyzed 49 obese pregnant women who either received placebo (N = 24) or daily 2 g of DHA plus EPA (N = 25) from weeks 10 to 16 of gestation to term. The results show that plasma C‐reactive protein was reduced in women who received DHA plus EPA. Meanwhile, the adipose tissue and placenta in women who received DHA plus EPA presented lower levels of inflammatory markers (Haghiac et al., 2015). A double‐blinded, randomized, controlled trial revealed that in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus, the administration of 180 mg of EPA and 120 mg of DHA twice a day for 6 weeks increased the mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPAR‐γ) and reduced the mRNA expression of low‐density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), IL‐1, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF‐α) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, indicating a lower level of insulin resistance (Jamilian Samimi, Mirhosseini, Afshar Ebrahimi, Aghadavod, Taghizadeh, et al., 2018). Similar findings have also been reported by other randomized controlled trials (Samimi et al., 2015; Taghizadeh et al., 2016). In a prospective study, 236 thyroid disease‐free, Caucasian pregnant women were assigned to take‐in swordfish, oily fish, swordfish plus other fish, and fish other than swordfish and oily fish. The serum levels of thyroid antibodies were lowest in women consuming oily fish. Meanwhile, a negative relationship was found between fish consumption and serum levels of thyroid antibodies in women consuming oily fish (Benvenga et al., 2016). A prospective study enrolled 725 pregnant women, among whom 165 women consumed omega‐3 fatty acids in the third trimester. The analysis revealed that the levels of urinary 8‐iso‐prostaglandin F2α, an oxidative stress marker, and its metabolite were lower in women who consumed omega‐3 fatty acids (Sley et al., 2020). This study indicates that omega‐3 fatty acids reduce oxidative stress during pregnancy. Similar findings have also been reported (Jamilian et al., 2017; Kajarabille et al., 2017; Razavi et al., 2017). However, these studies did not directly focus on the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on pregnancy outcomes in patients with RM. Rather, they could only serve as indirect evidence implying the treatment potential of omega‐3 fatty acids in these patients. In addition, the dosage of omega‐3 fatty acids varies among studies, and the optimal dosage of omega‐3 fatty acids still needs to be investigated. Moreover, most of these studies have a small sample size (fewer than 60 in each group), which would affect the statistical power and reliability of the findings.

5. CONCLUSION

RM greatly hampers reproductivity, which is induced or highly correlated with obesity, thyroid dysfunction, polycystic ovary syndrome, antiphospholipid syndrome, dysregulation of immune cells such as NK cells, T cells, and macrophages, oxidative stress, and other factors. In this review, it is clarified that omega‐3 fatty acids may prevent the pathogenesis of RM by modulating the dysregulation of trophoblasts, immune cells, oxidative stress, and endocrine function. In addition, the summarization of clinical evidence suggests that omega‐3 fatty acid supplements may serve as a potential therapeutic agent for RM, either directly improving pregnancy outcomes in patients with RM or indirectly ameliorating inflammation, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy (Figure 1). However, there is too little evidence directly demonstrating the involvement of omega‐3 fatty acids in the pathogenesis of RM or the efficacy of omega‐3 fatty acids in treating patients with RM. Therefore, future studies should investigate the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on immunity, oxidative stress, inflammation, and the endocrine system in RM, as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms. More importantly, further clinical studies should be conducted to clarify the therapeutic role of omega‐3 fatty acid supplements in treating RM, thus promoting the outcome of these patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fangxiang Mu: Data curation (equal); funding acquisition (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Huyan Huo: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); writing – original draft (equal). Mei Wang: Investigation (equal); methodology (equal); visualization (equal). Fang Wang: Conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by the Science Foundation of Lanzhou University (Grant No. 071100132) and the Science Foundation of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (Grant No. YJS‐BD‐19), and the Medical Innovation and Development Project of Lanzhou University (Grant No. lzuyxcx‐2022‐137).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study does not involve any human or animal testing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

Mu, F. , Huo, H. , Wang, M. , & Wang, F. (2023). Omega‐3 fatty acid supplements and recurrent miscarriage: A perspective on potential mechanisms and clinical evidence. Food Science & Nutrition, 11, 4460–4471. 10.1002/fsn3.3464

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Akre, S. , Sharma, K. , Chakole, S. , & Wanjari, M. B. (2022). Recent advances in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome: A review article. Cureus, 14(8), e27689. 10.7759/cureus.27689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfian, I. , Chakraborty, A. , Yong, H. E. J. , Saini, S. , Lau, R. W. K. , Kalionis, B. , Dimitriadis, E. , Alfaidy, N. , Ricardo, S. D. , Samuel, C. S. , & Murthi, P. (2022). The placental NLRP3 inflammasome and its downstream targets, caspase‐1 and interleukin‐6, are increased in human fetal growth restriction: Implications for aberrant inflammation‐induced trophoblast dysfunction. Cell, 11(9), 1413. 10.3390/cells11091413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alrashed, M. , Tabassum, H. , Almuhareb, N. , Almutlaq, N. , Alamro, W. , Alanazi, S. T. , Alenazi, F. K. , Alahmed, L. B. , Al Abudahash, M. M. , & Alenzi, N. D. (2021). Assessment of DNA damage in relation to heavy metal induced oxidative stress in females with recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL). Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 28(9), 5403–5407. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.05.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Sheikh, Y. A. , Ghneim, H. K. , Alharbi, A. F. , Alshebly, M. M. , Aljaser, F. S. , & Aboul‐Soud, M. A. M. (2019). Molecular and biochemical investigations of key antioxidant/oxidant molecules in Saudi patients with recurrent miscarriage. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 18(6), 4450–4460. 10.3892/etm.2019.8082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amini, M. , Bahmani, F. , Foroozanfard, F. , Vahedpoor, Z. , Ghaderi, A. , Taghizadeh, M. , Karbassizadeh, H. , & Asemi, Z. (2018). The effects of fish oil omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation on mental health parameters and metabolic status of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 1–9. 10.1080/0167482X.2018.1508282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrane, S. , & McConnell, R. (2019). Endocrine causes of recurrent pregnancy loss. Seminars in Perinatology, 43(2), 80–83. 10.1053/j.semperi.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asari, M. A. , Sirajudeen, K. N. S. , Mohd Yusof, N. A. , & Mohd Amin, M. S. I. (2022). DHA‐rich fish oil and Tualang honey reduce chronic stress‐induced oxidative damage in the brain of rat model. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 12(4), 361–366. 10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno, C. , Sugiura‐Ogasawara, M. , Ebara, T. , Ide, S. , Kitaori, T. , Sato, T. , Ando, K. , & Morita, Y. (2020). Attitude and perceptions toward miscarriage: A survey of a general population in Japan. Journal of Human Genetics, 65(2), 155–164. 10.1038/s10038-019-0694-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak, S. , & Duttaroy, A. K. (2013). Effects of fatty acids on angiogenic activity in the placental extravillious trophoblast cells. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids, 88(2), 155–162. 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenga, S. , Vigo, M. T. , Metro, D. , Granese, R. , Vita, R. , & Le Donne, M. (2016). Type of fish consumed and thyroid autoimmunity in pregnancy and postpartum. Endocrine, 52(1), 120–129. 10.1007/s12020-015-0698-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradberry, J. C. , & Hilleman, D. E. (2013). Overview of omega‐3 fatty acid therapies. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 38(11), 681–691. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton, E. A. , & Mason, R. P. (2017). Prescription omega‐3 fatty acid products containing highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). Lipids in Health and Disease, 16(1), 23. 10.1186/s12944-017-0415-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho‐Munoz, D. , Niven, J. , Kucuk, S. , Cucchi, D. , Certo, M. , Jones, S. W. , Fischer, D. P. , Mauro, C. , & Nicolaou, A. (2022). Omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reverse the impact of western diets on regulatory T cell responses through averting ceramide‐mediated pathways. Biochemical Pharmacology, 204, 115211. 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta, G. , Iovenitti, P. , & Falciglia, K. (2005). Recurrent miscarriage associated with antiphospholipid antibodies: Prophylactic treatment with low‐dose aspirin and fish oil derivates. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology, 32(1), 49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, P. , Goswami, S. K. , Rajani, S. , Sharma, S. , Kabir, S. N. , Chakravarty, B. , & Jana, K. (2013). Recurrent pregnancy loss in polycystic ovary syndrome: Role of hyperhomocysteinemia and insulin resistance. PLoS One, 8(5), e64446. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehimi, M. , Ward, R. , Pestel, J. , Robert, M. , Pesenti, S. , Bendridi, N. , Michalski, M.‐C. , Laville, M. , Vidal, H. , & Eljaafari, A. (2019). Omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids inhibit IL‐17A secretion through decreased ICAM‐1 expression in T cells co‐cultured with adipose‐derived stem cells harvested from adipose tissues of obese subjects. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 63(11), e1801148. 10.1002/mnfr.201801148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Y. , Chen, C. Y. , Liu, C. C. , & Chen, C. P. (2018). Omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce preterm labor by inhibiting trophoblast cathepsin S and inflammasome activation. Clinical Science, 132(20), 2221–2239. 10.1042/CS20180796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coomarasamy, A. , Devall, A. J. , Brosens, J. J. , Quenby, S. , Stephenson, M. D. , Sierra, S. , Christiansen, O. B. , Small, R. , Brewin, J. , Roberts, T. E. , Dhillon‐Smith, R. , Harb, H. , Noordali, H. , Papadopoulou, A. , Eapen, A. , Prior, M. , Di Renzo, G. C. , Hinshaw, K. , Mol, B. W. , … Gallos, I. D. (2020). Micronized vaginal progesterone to prevent miscarriage: A critical evaluation of randomized evidence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 223(2), 167–176. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L. , Xu, F. , Wang, S. , Li, X. , Lin, H. , Ding, Y. , & Du, M. (2021). Pharmacological activation of rev‐erbalpha suppresses LPS‐induced macrophage M1 polarization and prevents pregnancy loss. BMC Immunology, 22(1), 57. 10.1186/s12865-021-00438-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davanso, M. R. , Crisma, A. R. , Braga, T. T. , Masi, L. N. , do Amaral, C. L. , Leal, V. N. C. , de Lima, D. S. , Patente, T. A. , Barbuto, J. A. , Corrêa‐Giannella, M. L. , Lauterbach, M. , Kolbe, C. C. , Latz, E. , Camara, N. O. S. , Pontillo, A. , & Curi, R. (2021). Macrophage inflammatory state in type 1 diabetes: Triggered by NLRP3/iNOS pathway and attenuated by docosahexaenoic acid. Clinical Science, 135(1), 19–34. 10.1042/CS20201348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, T. , Liao, X. , & Zhu, S. (2022). Recent advances in treatment of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 77(6), 355–366. 10.1097/OGX.0000000000001033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh, H. , & Way, S. S. (2019). Immunological basis for recurrent fetal loss and pregnancy complications. Annual Review of Pathology, 14, 185–210. 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bari, F. , Granese, R. , Le Donne, M. , Vita, R. , & Benvenga, S. (2017). Autoimmune abnormalities of postpartum thyroid diseases. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 8, 166. 10.3389/fendo.2017.00166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadis, E. , Menkhorst, E. , Saito, S. , Kutteh, W. H. , & Brosens, J. J. (2020). Recurrent pregnancy loss. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 6(1), 98. 10.1038/s41572-020-00228-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNicolantonio, J. J. , & O'Keefe, J. H. (2020). The importance of marine omega‐3s for brain development and the prevention and treatment of behavior, mood, and other brain disorders. Nutrients, 12(8), 2333. 10.3390/nu12082333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, A. C. , Morgan, J. , Kane, M. , Stagnaro‐Green, A. , & Stephenson, M. D. (2020). Subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity in recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Fertility and Sterility, 113(3), 587–600 e581. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESHRE Guideline Group on RPL , Bender Atik, R. , Christiansen, O. B. , Elson, J. , Kolte, A. M. , Lewis, S. , Middeldorp, S. , Nelen, W. , Peramo, B. , Quenby, S. , Vermeulen, N. , & Goddijn, M. (2018). ESHRE guideline: recurrent pregnancy loss. Human Reproduction Open, 2018(2), hoy004. 10.1093/hropen/hoy004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghneim, H. K. , & Alshebly, M. M. (2016). Biochemical markers of oxidative stress in Saudi women with recurrent miscarriage. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 31(1), 98–105. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.1.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghneim, H. K. , Al‐Sheikh, Y. A. , Alshebly, M. M. , & Aboul‐Soud, M. A. (2016). Superoxide dismutase activity and gene expression levels in Saudi women with recurrent miscarriage. Molecular Medicine Reports, 13(3), 2606–2612. 10.3892/mmr.2016.4807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa, A. M. , & Abd El‐Aziz, E. A. (2016). Omega‐3 fatty acids decreases oxidative stress, tumor necrosis factor‐alpha, and interleukin‐1 beta in hyperthyroidism‐induced hepatic dysfunction rat model. Pathophysiology, 23(4), 295–301. 10.1016/j.pathophys.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. M. , & O'Donoghue, K. (2019). A review of reproductive outcomes of women with two consecutive miscarriages and no living child. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 39(6), 816–821. 10.1080/01443615.2019.1576600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. , Agarwal, A. , Banerjee, J. , & Alvarez, J. G. (2007). The role of oxidative stress in spontaneous abortion and recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 62(5), 335–347; quiz 353–334. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000261644.89300.df [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghiac, M. , Yang, X. H. , Presley, L. , Smith, S. , Dettelback, S. , Minium, J. , Belury, M. A. , Catalano, P. M. , & Hauguel‐de Mouzon, S. (2015). Dietary omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation reduces inflammation in obese pregnant women: A randomized double‐blind controlled clinical trial. PLoS One, 10(9), e0137309. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamulyak, E. N. , Scheres, L. J. , Marijnen, M. C. , Goddijn, M. , & Middeldorp, S. (2020). Aspirin or heparin or both for improving pregnancy outcomes in women with persistent antiphospholipid antibodies and recurrent pregnancy loss. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD012852. 10.1002/14651858.CD012852.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempstock, J. , Jauniaux, E. , Greenwold, N. , & Burton, G. J. (2003). The contribution of placental oxidative stress to early pregnancy failure. Human Pathology, 34(12), 1265–1275. 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heshmati, J. , Morvaridzadeh, M. , Maroufizadeh, S. , Akbari, A. , Yavari, M. , Amirinejad, A. , Maleki‐Hajiagha, A. , & Sepidarkish, M. (2019). Omega‐3 fatty acids supplementation and oxidative stress parameters: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of clinical trials. Pharmacological Research, 149, 104462. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, T. , Myung, S. K. , & Pham, T. T. (2021). Gynecological cancer and omega‐3 fatty acid intakes: Meta‐analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 30(1), 153–162. 10.6133/apjcn.202103_30(1).0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamilian, M. , Hashemi Dizaji, S. , Bahmani, F. , Taghizadeh, M. , Memarzadeh, M. R. , Karamali, M. , Akbari, M. , & Asemi, Z. (2017). A randomized controlled clinical trial investigating the effects of omega‐3 fatty acids and vitamin E co‐supplementation on biomarkers of oxidative stress, inflammation and pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 41(2), 143–149. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamilian, M. , Samimi, M. , Kolahdooz, F. , Khalaji, F. , Razavi, M. , & Asemi, Z. (2016). Omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation affects pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. The Journal of Maternal‐Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 29(4), 669–675. 10.3109/14767058.2015.1015980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamilian, M. , Samimi, M. , Mirhosseini, N. , Afshar Ebrahimi, F. , Aghadavod, E. , Taghizadeh, M. , & Asemi, Z. (2018). A randomized double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled trial investigating the effect of fish oil supplementation on gene expression related to insulin action, blood lipids, and inflammation in gestational diabetes mellitus‐fish oil supplementation and gestational diabetes. Nutrients, 10(2), 163. 10.3390/nu10020163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamilian, M. , Samimi, M. , Mirhosseini, N. , Afshar Ebrahimi, F. , Aghadavod, E. , Talaee, R. , Jafarnejad, S. , Dizaji, S. H. , & Asemi, Z. (2018). The influences of vitamin D and omega‐3 co‐supplementation on clinical, metabolic and genetic parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Affective Disorders, 238, 32–38. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K. N. , Heijink, M. , Giera, M. , Freysdottir, J. , & Hardardottir, I. (2022). Dietary fish oil increases the number of CD11b(+)CD27(−) NK cells at the inflammatory site and enhances key hallmarks of resolution of murine antigen‐induced peritonitis. Journal of Inflammation Research, 15, 311–324. 10.2147/JIR.S342399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J. , Zhai, H. , Zhou, H. , Song, S. , Mor, G. , & Liao, A. (2019). The role and mechanism of vitamin D‐mediated regulation of Treg/Th17 balance in recurrent pregnancy loss. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 81(6), e13112. 10.1111/aji.13112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, G. M. , Basak, S. , Weedon‐Fekjaer, M. S. , Staff, A. C. , & Duttaroy, A. K. (2011). Docosahexaenoic acid stimulates tube formation in first trimester trophoblast cells, HTR8/SVneo. Placenta, 32(9), 626–632. 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajarabille, N. , Hurtado, J. A. , Pena‐Quintana, L. , Pena, M. , Ruiz, J. , Diaz‐Castro, J. , Rodríguez‐Santana, Y. , Martin‐Alvarez, E. , López‐Frias, M. , Soldado, O. , Lara‐Villoslada, F. , & Ochoa, J. J. (2017). Omega‐3 LCPUFA supplement: A nutritional strategy to prevent maternal and neonatal oxidative stress. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(2), e12300. 10.1111/mcn.12300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knofler, M. , Haider, S. , Saleh, L. , Pollheimer, J. , Gamage, T. , & James, J. (2019). Human placenta and trophoblast development: Key molecular mechanisms and model systems. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 76(18), 3479–3496. 10.1007/s00018-019-03104-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, K. , Nakagawa, K. , Horikawa, T. , Moriyama, A. , Ojiro, Y. , Takamizawa, S. , Ochiai, A. , Matsumura, Y. , Ikemoto, Y. , Yamaguchi, K. , & Sugiyama, R. (2021). Increasing number of implantation failures and pregnancy losses associated with elevated Th1/Th2 cell ratio. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 86(3), e13429. 10.1111/aji.13429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M. J. , Kim, J. H. , Lee, J. Y. , Ko, E. J. , Park, H. W. , Shin, J. E. , Ahn, E.‐H. , & Kim, N. K. (2022). Genetic polymorphisms in the 3'‐untranslated regions of SMAD5, FN3KRP, and RUNX‐1 are associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. Biomedicine, 10(7), 1481. 10.3390/biomedicines10071481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarin, N. , Vaquero, E. , Exacoustos, C. , Bertonotti, E. , Romanini, M. E. , & Arduini, D. (2009). Low‐dose aspirin and omega‐3 fatty acids improve uterine artery blood flow velocity in women with recurrent miscarriage due to impaired uterine perfusion. Fertility and Sterility, 92(1), 296–300. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Gao, Y. H. , Xu, L. , & Li, Z. Y. (2020). Meta‐analysis of heparin combined with aspirin versus aspirin alone for unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 151(1), 23–32. 10.1002/ijgo.13266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. , Sun, F. , Xu, Y. , Chen, L. , Chen, C. , Cui, L. , Qian, J. , Li, D. , Wang, S. , & Du, M. (2022). Tim‐3(+) decidual Mphis induced Th2 and Treg bias in decidual CD4(+)T cells and promoted pregnancy maintenance via CD132. Cell Death & Disease, 13(5), 454. 10.1038/s41419-022-04899-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Shi, J. , Zhao, W. , Huang, X. , Cui, L. , Liu, L. , Jin, X. , Li, D. , Zhang, X. , & Du, M. (2022). WNT16 from decidual stromal cells regulates HTR8/SVneo trophoblastic cell function via AKT/beta‐catenin pathway. Reproduction, 163(5), 241–250. 10.1530/REP-21-0282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Zhang, J. , Zhang, D. , Hong, X. , Tao, Y. , Wang, S. , Xu, Y. , Piao, H. , Yin, W. , Yu, M. , Zhang, Y. , Fu, Q. , Li, D. , Chang, X. , & Du, M. (2017). Tim‐3 signaling in peripheral NK cells promotes maternal‐fetal immune tolerance and alleviates pregnancy loss. Science Signaling, 10(498), eaah4323. 10.1126/scisignal.aah4323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, D. M. , Hutchinson, A. L. , Monk, J. M. , Power, K. A. , & Robinson, L. E. (2021). Dietary omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids modulate CD4(+) T‐cell subset markers, adipocyte antigen‐presentation potential, and NLRP3 inflammasome activity in a coculture model of obese adipose tissue. Nutrition, 91–92, 111388. 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , Qiu, Y. , Yu, E. D. , Xiang, S. , Meng, R. , Niu, K. F. , & Zhu, H. (2020). Comparison of therapeutic interventions for recurrent pregnancy loss in association with antiphospholipid syndrome: A systematic review and network meta‐analysis. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 83(4), e13219. 10.1111/aji.13219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lob, S. , Amann, N. , Kuhn, C. , Schmoeckel, E. , Wockel, A. , Zati Zehni, A. , Kaltofen, T. , Keckstein, S. , Mumm, J.‐N. , Meister, S. , Kolben, T. , Mahner, S. , Jeschke, U. , & Vilsmaier, T. (2021). Interleukin‐1 beta is significantly upregulated in the decidua of spontaneous and recurrent miscarriage placentas. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 144, 103283. 10.1016/j.jri.2021.103283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meital, L. T. , Windsor, M. T. , Perissiou, M. , Schulze, K. , Magee, R. , Kuballa, A. , Golledge, J. , Bailey, T. G. , Askew, C. D. , & Russell, F. D. (2019). Omega‐3 fatty acids decrease oxidative stress and inflammation in macrophages from patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 12978. 10.1038/s41598-019-49362-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles‐Perez, B. , Nogues, M. R. , Sanchez‐Martos, V. , Taltavull, N. , Mendez, L. , Medina, I. , Ramos‐Romero, S. , Torres, J. L. , & Romeu, M. (2021). The effects of the combination of buckwheat D‐fagomine and fish omega‐3 fatty acids on oxidative stress and related risk factors in pre‐obese rats. Food, 10(2), 332. 10.3390/foods10020332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloudizargari, M. , Redegeld, F. , Asghari, M. H. , Mosaffa, N. , & Mortaz, E. (2020). Long‐chain polyunsaturated omega‐3 fatty acids reduce multiple myeloma exosome‐mediated suppression of NK cell cytotoxicity. Daru, 28(2), 647–659. 10.1007/s40199-020-00372-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaro, V. R. , Costabile, M. , Murphy, K. J. , Hii, C. S. , Howe, P. R. , & Ferrante, A. (2008). Leukocyte numbers and function in subjects eating n‐3 enriched foods: Selective depression of natural killer cell levels. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 10(3), R57. 10.1186/ar2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamatsu, T. , Fujii, T. , Schust, D. J. , Tsuchiya, N. , Tokita, Y. , Hoya, M. , Akiba, N. , Iriyama, T. , Kawana, K. , Osuga, Y. , & Fujii, T. (2018). Tokishakuyakusan, a traditional Japanese medicine (Kampo) mitigates iNKT cell‐mediated pregnancy loss in mice. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 80(4), e13021. 10.1111/aji.13021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negro, R. , & Stagnaro‐Green, A. (2014). Clinical aspects of hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and thyroid screening in pregnancy. Endocrine Practice, 20(6), 597–607. 10.4158/EP13350.RA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. , Yin, S. , & Wang, M. (2021). Significance of the ratio interferon‐gamma/interleukin‐4 in early diagnosis and immune mechanism of unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 154(1), 39–43. 10.1002/ijgo.13494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine . (2012). Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: A committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility, 98(5), 1103–1111. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, D. , Lu, J. , Fu, Z. , Lv, S. , & Hou, L. (2022). Psoralen promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of human extravillous trophoblast derived HTR‐8/Svneo cells in vitro by NF‐kappaB pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 804400. 10.3389/fphar.2022.804400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J. , Zhang, N. , Lin, J. , Wang, C. , Pan, X. , Chen, L. , Li, D. , & Wang, L. (2018). Distinct pattern of Th17/Treg cells in pregnant women with a history of unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Bioscience Trends, 12(2), 157–167. 10.5582/bst.2018.01012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenby, S. , Gallos, I. D. , Dhillon‐Smith, R. K. , Podesek, M. , Stephenson, M. D. , Fisher, J. , Brosens, J. J. , Brewin, J. , Ramhorst, R. , Lucas, E. S. , McCoy, R. C. , Anderson, R. , Daher, S. , Regan, L. , Al‐Memar, M. , Bourne, T. , MacIntyre, D. A. , Rai, R. , Christiansen, O. B. , … Coomarasamy, A. (2021). Miscarriage matters: The epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet, 397(10285), 1658–1667. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00682-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli, F. , Nanetti, L. , Vignini, A. , Mazzanti, L. , Giannubilo, S. R. , Curzi, C. M. , Turi, A. , Vitali, P. , & Tranquilli, A. L. (2010). Nitric oxide platelet production in spontaneous miscarriage in the first trimester. Fertility and Sterility, 93(6), 1976–1982. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani, E. , Samimi, M. , Ebrahimi, F. A. , Foroozanfard, F. , Ahmadi, S. , Rahimi, M. , Jamilian, M. , Aghadavod, E. , Bahmani, F. , Taghizadeh, M. , Memarzadeh, M. R. , & Asemi, Z. (2017). The effects of omega‐3 fatty acids and vitamin E co‐supplementation on gene expression of lipoprotein(a) and oxidized low‐density lipoprotein, lipid profiles and biomarkers of oxidative stress in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 439, 247–255. 10.1016/j.mce.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravic, B. , Debeljak‐Martacic, J. , Pokimica, B. , Vidovic, N. , Rankovic, S. , Glibetic, M. , Stepanović, P. , & Popovic, T. (2022). The effect of fish oil‐based foods on lipid and oxidative status parameters in police dogs. Biomolecules, 12(8), 1092. 10.3390/biom12081092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi, M. , Jamilian, M. , Samimi, M. , Afshar Ebrahimi, F. , Taghizadeh, M. , Bekhradi, R. , Hosseini, E. S. , Kashani, H. H. , Karamali, M. , & Asemi, Z. (2017). The effects of vitamin D and omega‐3 fatty acids co‐supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress and pregnancy outcomes in patients with gestational diabetes. Nutrition & Metabolism, 14, 80. 10.1186/s12986-017-0236-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees, G. , Brough, L. , Orsatti, G. M. , Lodge, A. , & Walker, S. (2022). Do micronutrient and omega‐3 fatty acid supplements affect human maternal immunity during pregnancy? A scoping review. Nutrients, 14(2), 367. 10.3390/nu14020367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei Kahmini, F. , Shahgaldi, S. , & Moazzeni, S. M. (2020). Mesenchymal stem cells alter the frequency and cytokine profile of natural killer cells in abortion‐prone mice. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 235(10), 7214–7223. 10.1002/jcp.29620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, E. , & Costa, M. (1993). Fish oil derivatives as a prophylaxis of recurrent miscarriage associated with antiphospholipid antibodies (APL): A pilot study. Lupus, 2(5), 319–323. 10.1177/096120339300200508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, F. , Alavi‐Naeini, A. , Mardanian, F. , Ghazvini, M. R. , & Mahaki, B. (2020). Omega‐3 and vitamin E co‐supplementation can improve antioxidant markers in obese/overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research, 90(5–6), 477–483. 10.1024/0300-9831/a000588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimi, E. , Karimi‐Zarchi, M. , Dastgheib, S. A. , Abbasi, H. , Tabatabaiee, R. S. , Hadadan, A. , Amjadi, N. , Akbarian‐Bafghi, M. J. , & Neamatzadeh, H. (2020). Association of promoter region polymorphisms of IL‐6 and IL‐18 genes with risk of recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Fetal and Pediatric Pathology, 39(4), 346–359. 10.1080/15513815.2019.1652379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samimi, M. , Jamilian, M. , Asemi, Z. , & Esmaillzadeh, A. (2015). Effects of omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation on insulin metabolism and lipid profiles in gestational diabetes: Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Clinical Nutrition, 34(3), 388–393. 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, K. , Sciascia, S. , de Groot, P. G. , Devreese, K. , Jacobsen, S. , Ruiz‐Irastorza, G. , Salmon, J. E. , Shoenfeld, Y. , Shovman, O. , & Hunt, B. J. (2018). Antiphospholipid syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 4, 17103. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwager, J. , Bompard, A. , Raederstorff, D. , Hug, H. , & Bendik, I. (2022). Resveratrol and omega‐3 PUFAs promote human macrophage differentiation and function. Biomedicine, 10(7), 1524. 10.3390/biomedicines10071524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger, B. , & Koehl, U. (2022). Underlying mechanisms of evasion from NK cells as rationale for improvement of NK cell‐based immunotherapies. Frontiers in Immunology, 13, 910595. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.910595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Y. R. , Hu, W. T. , Shen, H. H. , Wei, C. Y. , Liu, Y. K. , Ma, X. Q. , Li, M.‐Q. , & Zhu, X. Y. (2022). An imbalance of the IL‐33/ST2‐AXL‐efferocytosis axis induces pregnancy loss through metabolic reprogramming of decidual macrophages. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 79(3), 173. 10.1007/s00018-022-04197-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, H. , Franke, C. , Demmelmair, H. , & Koletzko, B. (2009). Effect of docosahexaenoic acid on oxidative stress in placental trophoblast cells. Early Human Development, 85(7), 433–437. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J. E. (2020). Dietary sources of omega‐3 fatty acids versus omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation effects on cognition and inflammation. Current Nutrition Reports, 9(3), 264–277. 10.1007/s13668-020-00329-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sley, E. G. , Rosen, E. M. , van't Erve, T. J. , Sathyanarayana, S. , Barrett, E. S. , Nguyen, R. H. N. , Bush, N. R. , Milne, G. L. , Swan, S. H. , & Ferguson, K. K. (2020). Omega‐3 fatty acid supplement use and oxidative stress levels in pregnancy. PLoS One, 15(10), e0240244. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov, D. I. , Mikhailova, V. A. , Agnayeva, A. O. , Bazhenov, D. O. , Khokhlova, E. V. , Bespalova, O. N. , Gzgzyan, A. M. , & Selkov, S. A. (2019). NK and trophoblast cells interaction: Cytotoxic activity on recurrent pregnancy loss. Gynecological Endocrinology, 35(sup1), 5–10. 10.1080/09513590.2019.1632084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, M. T. , Lin, S. H. , & Chen, Y. C. (2011). Genetic association studies of angiogenesis‐ and vasoconstriction‐related genes in women with recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 17(6), 803–812. 10.1093/humupd/dmr027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura‐Ogasawara, M. (2015). Recurrent pregnancy loss and obesity. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 29(4), 489–497. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh, M. , Jamilian, M. , Mazloomi, M. , Sanami, M. , & Asemi, Z. (2016). A randomized‐controlled clinical trial investigating the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids and vitamin E co‐supplementation on markers of insulin metabolism and lipid profiles in gestational diabetes. Journal of Clinical Lipidology, 10(2), 386–393. 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajuddin, N. , Shaikh, A. , & Hassan, A. (2016). Prescription omega‐3 fatty acid products: Considerations for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity, 9, 109–118. 10.2147/DMSO.S97036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeyama, R. , Fukui, A. , Mai, C. , Yamamoto, M. , Saeki, S. , Yamaya, A. , & Shibahara, H. (2021). Co‐expression of NKp46 with activating or inhibitory receptors on, and cytokine production by, uterine endometrial NK cells in recurrent pregnancy loss. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 145, 103324. 10.1016/j.jri.2021.103324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar, S. , Prasad, S. , Kaur, L. , Mishra, J. , Puri, M. , Sachdeva, M. P. , & Saraswathy, K. N. (2022). MTR, MTRR and CBS gene polymorphisms in recurrent miscarriages: A case control study from North India. Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences, 15(2), 191–196. 10.4103/jhrs.jhrs_186_21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, J. , Kitashoji, A. , Fukunaga, Y. , Kashihara, J. , Nakano, A. , & Kamizono, A. (2016). Intravenous immunoglobulin suppresses abortion relates to an increase in the CD44bright NK subset in recurrent pregnancy loss model mice. Biology of Reproduction, 95(2), 37. 10.1095/biolreprod.116.138438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y. , Li, Y. H. , Zhang, D. , Xu, L. , Chen, J. J. , Sang, Y. F. , Piao, H.‐L. , Jing, X.‐L. , Yu, M. , Fu, Q. , Zhou, S.‐T. , Li, D.‐J. , & Du, M. R. (2021). Decidual CXCR4(+) CD56(bright) NK cells as a novel NK subset in maternal‐foetal immune tolerance to alleviate early pregnancy failure. Clinical and Translational Medicine, 11(10), e540. 10.1002/ctm2.540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, F. Y. , Wu, M. Y. , Chang, Y. L. , Wu, C. T. , & Ho, H. N. (2018). M1 macrophages decrease in the deciduae from normal pregnancies but not from spontaneous abortions or unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortions. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 117(3), 204–211. 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tur‐Torres, M. H. , Garrido‐Gimenez, C. , & Alijotas‐Reig, J. (2017). Genetics of recurrent miscarriage and fetal loss. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 42, 11–25. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthman, I. , Noureldine, M. H. A. , Ruiz‐Irastorza, G. , & Khamashta, M. (2019). Management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 78(2), 155–161. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle, R. F. , & Ekpo, G. E. (2013). Hysteroscopic metroplasty for the septate uterus: Review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, 20(1), 22–42. 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, S. G. , Riemma, G. , Carugno, J. , Perez‐Medina, T. , Alonso Pacheco, L. , Haimovich, S. , Parry, J. P. , Di Spiezio Sardo, A. , & De Franciscis, P. (2022). Postsurgical barrier strategies to avoid the recurrence of intrauterine adhesion formation after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: A network meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 226(4), 487–498 e488. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Yang, J. , Yan, Y. , Zhu, Z. , Mu, Y. , Wang, X. , Zhang, J. , Liu, L. , Zhao, F. , & Chi, Y. (2019). Effect of adoptive transfer of CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) Treg induced by trichostatin a on the prevention of spontaneous abortion. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 131, 30–35. 10.1016/j.jri.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiest, E. F. , Walsh‐Wilcox, M. T. , & Walker, M. K. (2017). Omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids protect against cigarette smoke‐induced oxidative stress and vascular dysfunction. Toxicological Sciences, 156(1), 300–310. 10.1093/toxsci/kfw255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L. F. , Porter, T. F. , & Scott, J. R. (2014). Immunotherapy for recurrent miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10, CD000112. 10.1002/14651858.CD000112.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P. L. , Zhu, J. W. , Zeng, C. , Li, X. , Xue, Q. , & Yang, H. X. (2022). IGFBP7 enhances trophoblast invasion via IGF‐1R/c‐Jun signaling in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Reproduction, 164(5), 231–241. 10.1530/REP-21-0501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. L. , Lai, Z. Z. , Shi, J. W. , Zhou, W. J. , Mei, J. , Ye, J. F. , Zhang, T. , Wang, J. , Zhao, J.‐Y. , Li, D.‐J. , & Li, M. Q. (2022). A defective lysophosphatidic acid‐autophagy axis increases miscarriage risk by restricting decidual macrophage residence. Autophagy, 18(10), 2459–2480. 10.1080/15548627.2022.2039000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yougbare, I. , Tai, W. S. , Zdravic, D. , Oswald, B. E. , Lang, S. , Zhu, G. , Leong‐Poi, H. , Qu, D. , Yu, L. , Dunk, C. , Zhang, J. , Sled, J. G. , Lye, S. J. , Brkić, J. , Peng, C. , Höglund, P. , Croy, B. A. , Adamson, S. L. , Wen, X.‐Y. , … Ni, H. (2017). Activated NK cells cause placental dysfunction and miscarriages in fetal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Nature Communications, 8(1), 224. 10.1038/s41467-017-00269-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W. , & Bao, S. (2022). Association of male factors with recurrent pregnancy loss. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 154, 103758. 10.1016/j.jri.2022.103758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q. , & He, J. (2022). Efficacy and safety of metformin in pregnant women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review with meta‐analysis of randomized and non‐randomized controlled trials. Gynecological Endocrinology, 38(7), 558–568. 10.1080/09513590.2022.2080194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.