Abstract

Digital light processing (DLP) 3D printing has become a powerful manufacturing tool for the fast fabrication of complex functional structures. The rapid progress in DLP printing has been linked to research on optical design factors and ink selection. This critical review highlights the main challenges in the DLP printing of photopolymerizable inks. The kinetics equations of photopolymerization reaction in a DLP printer are solved, and the dependence of curing depth on the process optical parameters and ink chemical properties are explained. Developments in DLP platform design and ink selection are summarized, and the roles of monomer structure and molecular weight on DLP printing resolution are shown by experimental data. A detailed guideline is presented to help engineers and scientists to select inks and optical parameters for fabricating functional structures for multi-material and 4D printing applications.

Keywords: Digital light processing, 3D printing, photosensitive monomer, ink selection, resolution improvement

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Digital light processing (DLP) printing is a layer-wise two-dimensional (2D) crosslinking of photosensitive inks when subjected to projection patterns. DLP printing has found applications in the rapid prototyping [1], tissue engineering [2,3], and regenerative medicine [4]. The market value was around US $370M in 2020, with an anticipated 25% compound annual growth rate between 2022 and 2026 [5]. The main applications include the fabrication of medical devices and healthcare equipment [6], surgical guides for dentistry [7], wax models for jewelry [8], sculptures for the aesthetics industry [9], and metamaterials for the soft robotics [10,11]. The advantages of DLP printing for creating micro-tissues has been discussed in a recent review [4]. In healthcare, organ failure or loss of organ function is becoming the number one cause of death worldwide [12]. Thus, DLP printing of the tissue or organ blocks can be a promising therapeutic option. For example, diabetes impact ever-growing four hundreds of millions of people [12], where transplantation of islets of Langerhans may enable insulin independence [13,14]. The effectiveness of such strategies depends on the delivery of various biological components to the implant or transplanted part. The rapid fabrication of vascularized tissues with current technologies is another unmet need. Recent advancements in the field [15] still lack an adequate variety of hollow constructs and capillaries compared to the microenvironment of natural tissue. DLP overcomes the current challenges in the fast fabrication of tissue building blocks at a high fidelity [2] to make three-dimensional (3D) tissue scaffolds at a clinically relevant production rate [16]. The rate of DLP printing is higher than conventional additive manufacturing methods such as extrusion 3D printing [17,18].

The light projection can occur via liquid crystal displays (LCDs) and digital micromirror devices (DMDs), used to direct the light as squared voxel patterns onto an ink material [4,19]. Examples of simple LCD- and DMD-based projectors are shown in Figure 1a–b. The LCD works by transmissive planar light patterns, while the DMD works by reflective processing of digital patterns. The LCD projectors are unable to transmit high intensity and high energy (UV) lights through the liquid crystal material [4,20,21]. The DMD is a micro-electromechanical semiconductor device designed to reflect a patterned high-intensity UV light from a light-emitting diode (LED) source to print high-fidelity structures [22,23].

Figure 1. DLP 3D printing,

a) a typical LCD-based platform as a transmissive method for 2D patterning of the light, b) a typical DMD-based DLP platform as a reflective technology for 2D patterning of the light, c) An anatomical photograph of a porcine heart showing the diversity in a natural biological organ (red represents the arterial blood supply and blue represents the venous blood supply) obtained by corrosion casting [35], d) a successful production of an (i) fractal tree, (ii) a hollow blood vessel with a pure non-scattering material (PEGDA, 1% w/v Irgacure 819 ), and zoom-in detail of vessel opening, (iii) the same material including light scattering bead (glass beads of 4 μm diameter, 1% w/v) resembling scattering due to presence of live cells, leading to the formation of clogged blood vessels through DMD-DLP printing [36].

3D printing technologies include contact-based and contactless methods. The common contact-based methods consist of fused deposition modeling, extrusion, and inkjet printing. Extrusion 3D printing has the versatility and affordability to make small to large structures [19]. It is a low-cost technology that benefits from a relatively high fabrication speed [24] and control over the mechanical properties [25]. It also has low resolutions, i.e. 100-1200 μm, compared to inkjet 3D printing, i.e. 10-50 μm [26]. Inkjet 3D printers deposit liquid-binding inks, benefiting from multiple reservoirs to be used for multi-material direct writing [24]. The low speed and high shear forces [27], along with the possibility of needle clogging, limit the use of this technology. Contactless methods consist of fabrication by stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP) 3D printing [28,29]. SLA is a solid freeform additive manufacturing [30,31], which uses laser light to sweep the ink surface for crosslinking and fabricating structures. It has a practical resolution of 40-150 μm [32]. DLP benefits from a higher speed [33], easy control over the mechanical properties [25], and a superior scalable resolution down to 1 μm compared to other methods [21]. The speed of fabrication is typically as high as 0.5 and 15 mm/s [21,34].

DLP printing has enabled the creation of tissue-like structures with microstructures and stiffness values similar to those of biological tissues [10]. The blood vessels shown in Figure 1c represent the in vivo-like architectures in a real heart organ. Compared to other 3D printing techniques, DLP printing is a promising technology that can enable us to fabricate complex organs with vessels ranging from 5-20 μm (capillaries) to 2-3 cm (aorta) at a clinically relevant resolution and speed. Figure 1d-i shows a DLP-printed example of veins with multiple sizes using polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) ink. When adding other components to pure photosensitive monomers, light scattering issues arise. Figure 1d-ii, iii show that adding 1% w/v glass microbeads, which mimics light scattering, leads to the clogging of the 3D printed vessels and the failure to transport fluids. Further investigations into the material selection are needed, along with a better understanding of light-material interactions such as refraction, scattering, and absorption kinetics.

A deeper insight into the molecular structure of photopolymerizable inks and the kinetics of photopolymerization reaction is required to optimize DLP printing towards high spatial resolutions and defined architectures. Further ink development is needed to obtain the resolution and the speed to fulfill the growing demand for fast fabrication and mass production. In this review, we focus on ink selection and design parameters in DLP-printed soft structures. The role of the ink chemistry and the monomer molecular structure in enhancing the performance of DLP platforms are discussed. The kinetics of light absorption and photopolymerization reaction is explained in detail to control the curing depth and processing parameters, such as the light intensity and the exposure time. The discussions would help material scientists and bioengineers select proper materials/inks and understand fundamental design considerations for improving printing fidelity. This work provides a roadmap to select the proper sets of DLP parameters, such as light wavelength and intensity, and ink formulation, such as photoinitiator content, for desired structural functionality.

Other light-patterning technologies such as point-by-point light patterning in laser-induced forward transfer method [37], layer-by-layer light patterning in LCD-based stereolithography, or volumetric light patterning in multiphoton polymerization methods [38,39] are not discussed here as a focus to keep the integrity of the review; however, their concepts are almost similar to DLP. Post-printing material properties can change, and the response of 3D printed construct can deviate from the designed performance. Extra light and heat may help stabilize the structure. The photopolymerization reaction kinetics and Euler-Bernoulli beam theory can be implemented to study post-curing induced shape distortion of DLP-printed thin structures [40]. The mechanical behavior of printed samples during post-printing is controlled by light exposure time per layer, layer height, light intensity, and structure thickness. Readers are referred to Ref.[41] for more details on the post-printing treatments.

2. Applications and Limitations of DLP printing

The applications and limitations of DLP printing were discussed in some review papers [4,42]. DLP fabrication speed can reach as high as 1000 mm3/s in a volumetric scale [43] and show enhanced resolutions as precise as 1-10 μm, ideal for microtissues [4]. The fast creation of complex structures with micrometer-sized resolutions allows the fabrication of micro-vascularized tissue models. The applications are tissue fabrication for clinical transplantation and for modeling disease pathologies and pharmaceutical compound screening [44]. DLP can be used for drug discovery, drug delivery, and screening in micro-tissue models of the lung [45], liver [46], bone [47], heart [48,49], and spinal cord [50].

The clinical outlook of DLP printing depends on technical developments and translation. In the clinical treatment of acute diseases, such as myocardial infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, and cerebral infarction, the effective treatment window is a few hours, requiring the surgeons to prepare the surgical plan within a few minutes. One can build a 3D structure with relatively high accuracy and adjustable physiomechanical properties by changing the DLP parameters such as exposure time, light intensity, and light wavelength [10]. DLP-printed disease models are also useful for the teaching of clinical medicine. DLP can print personalized dental teaching models of sufficient accuracy to represent oral malformation diseases [51]. Medical devices such as implants can be printed with DLP printers using biodegradable [52] or non-degradable [53] materials for in-vivo applications. DLP is capable of building implants to match the injured part and guiding the tissue regeneration at the interface.

For medical applications, a fundamental challenge is producing functional vasculatures with biocompatible materials and maintaining cell viability [43]. There are limited inks that can provide desired resolutions, biocompatibility, and bioactivity for tissue regeneration and biomedical applications. For industrial applications, the toxicity of the ink formulation and odors produced due to solvent evaporation or the photopolymerization reaction can be challenging. To overcome these challenges, it is possible to look for an alternative choice of materials used in the ink formulation. However, light scattering and light absorption kinetics can vary by changing the choice of monomer and solvent in the ink formulation. Proper choice of the solvent and monomer is necessary to achieve the required rheological properties of the ink for DLP printing. Another limitation is the need for large volumes of photo-polymerizable inks to enable multi-material printing. In the next section, we review different DLP strategies that are developed to overcome many of these limitations by improving the level of automation and optical design.

3. Design Models of DLP Platforms

3.1. Different DLP Printing Strategies

Depending on the ink formulation, different types of light projectors can be integrated into the design of a DLP platform ranging from infrared [54] to ultraviolet light [2]. Wang et al. [55] developed one design using a white light projector (~ 2500 lumen at visible wavelength range) for light patterning and crosslinking a hydrogel layer with a low speed of around two minutes per layer. Commercial light projectors generate vast amounts of energy which can heat the polymer vat to above 40°C in ~ 15 minutes [55].

Recent advancements in optics design aim to improve DLP capabilities to make implantable microtissue models for biomedical applications. Figure 2a shows the components of a DLP platform [46] designed for making hydrogel constructs with the incorporation of live cells for ocular stem cell transplantation. Their platform utilized a high-intensity UV light source (365 nm at ~ 88 mW/cm2) with several projection lenses to pass a collimated array of light through a photomask provided by the DLP device. They transferred the patterned light on top of a stationary printing stage. In this DLP platform, UV exposure at around 30 s was sufficient to form 18 injectable gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) based microscale cylinders of ~ 500 μm in diameter and ~ 500 μm in height (i.e., layer thickness). Ma et al. [46] used a similar platform for printing a thin layer of liver on a chip model with around 30 μm resolution (< 10 s). Zhu et al. [52] used a similar DLP platform and replaced its light source with a near UV (405 nm) source, and added a moving z-stage. The new design successfully constructed more complex 3D hollow constructs such as tubes and nerve guidance conduits. A miniaturized DLP platform enabled in-vivo fabrication of hydrogel constructs under a near-infrared light (> 800 nm) [54]. Owing to the high penetration depth of the near-infrared light, the portable platform provided noninvasive fabrication of hydrogel structures subcutaneously [54].

Figure 2. The advancements in DLP platforms:

a) Rapid printing of conjunctival stem cell micro constructs in 18 cylindrical shapes for subconjunctival ocular injection, [59], b) Microfluidics enabled multi-material maskless DLP 3D printing [2]. c) Flashing photopolymerization 3D printing, i) Schematic diagram of the printer, ii, iv) 3D models of a micro altar and micro apple, iii,v) SEM image of the printed models by flash photopolymerization with 100 μm layer thickness [57], d) Projection-based 3D printing of cell patterning scaffolds with multiscale channels [58], e) Xolography linear volumetric 3D printing, i) diagram of xolography and the thin light sheet intensity distribution, ii) Rendered illustration of the printing zone and associated photoinduced reaction pathways of the DCPI, iii) Absorbance spectrum of DCPI under dark conditions (grey) and 375 nm UV irradiation (blue), iv) photoswitch kinetics probed at 585 nm, v) the model, ink under 3D printing and the fabricated part which is a spherical cage with free-floating ball [60].

The next level of complexity is multi-material capacity. Grigoryan et al. [56] proposed a semiautomatic approach to change the material and manual washing of the printed construct in a DLP platform. Figure 2b illustrates the components of a platform proposed by Miri et al. [2]. They enabled computerized multi-material 3D printing in DLP platforms by adding a microfluidic chip. The platform allows the rapid exchange of polymer inks in the vat area with computerized pneumatic controllers. A set of biconvex and planoconvex lenses with UV (~ 380 nm) light of 100 mW/cm2 intensity on the vat area were sufficient to print parallel lines. Depending on the used optics and hydrogel system, these lines had a 25 μm resolution in 2D printing at exposure times between 1 and 20 s per layer. This advancement demonstrated an ultrafast and computerized DLP platform enabling 3D printing of multi-materials, co-culture of different cell lines, and fabrication of tissue building blocks for regenerative medicine applications. Demonstration of the scalability and resolution adjustment are other challenges in designing DLP platforms.

You et al. [57] introduced flashing photopolymerization to improve resolution in DLP platforms, in which light was exposed in millisecond scale (flash) portions. The approach attenuated light scattering and increased the crosslinking resolution. Xue et al. [58] controlled a scaffold’s thickness with less sophistication through appropriate light power and exposure time selection. They showed that a predefined thickness of PEGDA solution between a glass slide and a coverslip could be crosslinked by a 2D light pattern projected through a plano-convex lens onto the solution (Figure 2d). The intensity of UV light (~ 365 nm) around 2.7 mW/cm2 at 2.6 s of time exposure allows fabricating their structure with a tailored thickness. The projection ratio and resolution of the light pattern were adjustable via the relative position of the plano-convex lens placed between the DMD chip and the polymer vat.

Regehly et al. [27] recently introduced another advancement in designing specific optics and suitable ink formulations for DLP platforms. They introduced xolography (the crossing “x” light beams generate the entire “holos” object), or volumetric DLP printer, which demonstrates high resolution and a high-volume generation rate about ten times faster than lithography. Integrating a benzophenone type II photoinitiator into a spiropyran photoswitch, a dual color photoinitiator (DCPI) system was developed for activation through simultaneous irradiation at two different light wavelengths. A thin light sheet of a first wavelength (375 nm) excites a thin layer of photoinitiator molecules from the initial dormant state to a latent state with a finite lifetime (~ 6 s). To provide a homogeneous light intensity in the light sheet, the light can be divided and irradiated by the ink volume from both sides of the material cuvette (Figure 2e-i). An orthogonally arranged DLP projector generates light of a second wavelength (550 nm). It focuses the sectional images of the 3D model on being manufactured into the plane of the thin light sheet. Those initiator molecules in the latent state absorb the patterned light reflected by the DLP projector and cause the current layer to polymerize (Figure 2e-ii). The desired object is fabricated by projecting a sequence of images during synchronized movement of the ink volume through the fixed optical setup. The technology can be expanded to produce microscopic and nanoscopic objects using optical systems with a higher numerical aperture due to the irradiation with two light beams of different wavelengths at a fixed angle. This volumetric two-color 3D printing is based on molecular photoswitches and does not require any nonlinear chemical or physical processes. It is expected that Xolography will stimulate 3D printing research fields from photoinitiator and material development to projection and light sheet technologies for rapid and improved-resolution 3D printing soon. The approach’s success is dependent on the development of materials that can be used in this system, enabling controllable gelation using a specific dual-color photoinitiator system.

In summary, the current challenges in DLP printing are (i) difficulty in combining different materials (multi-material printing) that can be solved by using microfluidic setups, (ii) difficulty in adjusting printing resolution that can be solved by proper choice of optical hardware and light patterning techniques such as flashing photopolymerization to reduce light scattering, and (iii) difficulty to develop proper inks for DLP platforms. These concerns can be addressed by the introduction of novel formulations composed of molecular photoswitches and light sheet technology. In the next section, we summarize the versatility in the design of optics for different DLP platforms. Then, we review the solution of kinetics equations for the photopolymerization reaction. These equations will address phenomenological relationships between governing design parameters in DLP platforms.

3.2. Optical Design Parameters

Table 1 shows the variety of DLP platforms, light source specifications, resolutions, and fabrication speeds. There is a wide range of wavelengths from UV (λ = 320 to 400 nm) to visible (λ = 400 to 700 nm) and near-infrared light (λ = 800 to 1000 nm). By increasing the light wavelength, the lower energy characteristic of the light and inadequate light absorption by the initiators can challenge the photopolymerization reaction needed to print a robust structure. Increasing the wavelength from UV to infrared light decreases printing resolution (see Table 1). Other than the wavelength, proper setting of optical parameters such as collimation and polarization of the light is needed to achieve a balance between resolution, light penetration depth, and fabrication speed. The selection of a proper photoinitiator system, light intensity, and exposure time allows us to achieve an improved printing resolution and printing speed. In Ru: SPS photoinitiator system, light intensity as low as 0.23 mW/cm2 and 30 s exposure time can be used to achieve ~ 50 μm resolution at 10-100 μm/s vertical speed in DLP 3D printing. If LAP is incorporated in the ink composition instead of Ru: SPS, a light intensity as large as 700 mW/cm2 and 200 milliseconds exposure time can be used to fabricate features of ~ 15 μm resolution at 40 μm/s vertical speed. The photoinitiator’s molar absorptivity (or extinction coefficient, ε) can describe these observations. Photoinitiator Ru:SPS shows a high molar absorptivity (ε = 14600 M−1cm−1 at 450 nm) 300 folds higher than that of LAP (ε = 50 M−1cm−1 at 405 nm) [61]. Ru:SPS can be used for photo crosslinking at much lower light intensities than LAP because a higher molar absorptivity leads to a higher photoreactivity.

Table 1.

Versatility of optics design in DLP printing platforms

| Initiator | Optics Characteristics | DLP Chip | Grayscale | DLP Output | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| λ (nm) | I mW/cm2 | t (s) | H*W pixels | Cell Viability | Planar Resolution (μm) | Vertical Speed (μm/s) | Ref. | ||

| UCNP@ LAP | 980 | - | 15 | 1024× 768 | No | >80% in 7 days | 100 | 13 | [54] |

| Eosin Y | 400-700 | - | 240 | 1920 x 1080 | No | 60-85% in 5 days | 50 | ~5 | [55,63] |

| LAP | 405 | 16 | 120 | 1280 × 800 | No | 50 | - | [56] | |

| LAP | 405 | 7-17 | 10 | 2560× 1600 | No | High viability in 11 weeks | 10 | 400 | [52] |

| LAP | 405 | 22 | 6-120 | 1920 x 1080 | No | High viability in 14 days | 10 | - | [64] |

| LAP | 365 | 500 | 1-20 | 1050× 920 | No | >80% in 7 days 30 days | 10 | 5-100 | [2] |

| LAP | 365 | 88 | 15 | - | No | 50 | 20 | [65] | |

| LAP | 365 | 88 | 10-30 | 1024× 768 | No | 70% in 10 days | 30-50 | 15-50 | [46,59,66] |

| LAP | 365 | 11 | 45 | 1920 x 1200 | No | 42-60% in 3 days | ~ 25 | 5-15 | [67] |

| LAP | 385 | - | 30 | 912x1140 | No | 50%-90% in 1 day | 50 | ~10 | [68,69] |

| LAP | 365 | 2.7-6 | 3 | 1920x1080 | No | High viability in 2 days | 20 | ~ 250 | [58] |

| Ru:SPS | 400-700 | 0.23 | 30-60 | 954 × 480 | No | >98% in 14 days | 50 | 10-100 | [70] |

| LAP | 980 | - | 15 | No | High | >100 | - | [54] | |

| LAP | 380 | 700 | 0.2 | - | No | - | 15 | 40 | [6] |

| LAP | 365 | 2.8-5.6 | 5 | 2560 × 1600 | No | Not applicable | <10 | ~ 20 | [57] |

| DCPI | 520+375 | 215 | <1 | 3840 × 2160 | No | Not applicable | 20 | 140 | [60] |

| BAPO | 405 | 3-10 | 10 | 1920 × 1080 | No | Not applicable | <100 | 8-12 | [1] |

| Irga 819 | 380 | 18 | 30 | 1280 × 800 | Yes | Not applicable | >50 | 3 | [10] |

λ: light wavelength; I: Intensity of light off the lens; t: light exposure time; NA: not applicable; “-”: not enough data to report. UCNP@ LAP: up-conversion nanoparticle coated with LAP as photoinitiator; BAPO: bis-acylphosphine oxide; DCPI: dual color photoinitiator.

In cell printing, enhancing light energy by decreasing the wavelength can increase the printing resolution. This occurs at the expense of lower cell viability since high-energy UV light is a potential source of damage to DNA, affecting the proliferation and fate of live cells. DLP is considered a contactless printing method, showing reasonable cell viability at most platforms reviewed in Table 1. Contact-based 3D printing methods such as extrusion printing apply shear forces to the ink, damaging the cell membrane and decreasing its viability. Contactless DLP printing has become a popular modality because of its higher fabrication speed (100-1000 mm3/s) and improved resolution (< 20 μm) compared to other printing methods. Table 1 reveals that developed platforms ignore the potential of grayscale 3D printing. This capability can be incorporated into a DLP platform without increasing the hardware costs. The grayscale 3D printing technique allows controlled gradient crosslinking in printed structures. 4D printing means introducing programmable time-dependent material properties to a final 3D printed product using a stimulus upon exposure to different wavelengths of light [62] or submerging it in a medium to trigger a programmed swelling response [10]. In the last section, we categorized different types of 4D printing stimuli in DLP platforms as future trends (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Inks developed for 4D printing with DLP platforms

|

|

PHEMA: poly-hydroxy-ethyl-methacrylate; CNT: carbon nanotube; BDGE: bisphenol A di-glycidyl ether; PGBAPE: poly(propylene glycol) bis(2-aminopropyl) ether; DC: decylamine; ChLCE: (water-sensitive) cholesteric liquid crystal elastomer.

In summary, enhancing the light energy by decreasing the wavelength can increase the printing resolution. The role of photoinitiator content, molar absorptivity, light intensity, and exposure time on printing resolution is more complex. The following section is devoted to introducing different types of light-material interactions. We summarize the solution of kinetic equations for curing reactions to elucidate the non-linear dependence of the curing depth on the photoinitiator content, its molar absorptivity, light intensity, and exposure time during DLP printing.

4. Light-Material Interactions

This section discusses how light-material interactions can be controlled. In DLP printing, light refracts when it travels from the DLP source and reaches the ink material, which presents another refractive index (Figure 3a). The refractive index of the ink material determines the speed of light propagation and phase. Reflection happens when the light is reflected on the surface of the ink material because of the difference between the refractive index of the ink material and air. Figure 3 shows the main parameters that should be considered when designing a DLP printing setup. Scattering is an important phenomenon that affects the resolution.

Figure 3. Light-material interactions:

a) Diagram of basic concepts; b) Single photon absorption process; c) Sketch of particle size effect on scattering; d) Diagram of the two primary methodologies to measure scattering in an ink material; E) Effect of different photo absorbers (i.e., methylene blue, coccine, and tartrazine) on the printability of convex cone and vertical channel; (i) Wavelength scan results of the photoinitiator (i.e., Diphenyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide, DPPO) and photo absorbers; f) Effect of tartrazine concentration on (i) Patency degree of the vertical channel with a diameter of 1.5 mm, and (ii) The minimum printable diameter (Dmin) of the vertical channel with different diameters, and typical sample with 0.25% tartrazine [71].

4.1. Scattering Types

Scattering occurs due to the loss of directionality of light and spread of light beam spot. This phenomenon controls fair intensity distribution in the ink material. Light scattering can be defined according to the sizes of particles/molecules/cells in the ink composition. Mie scattering occurs when particles are the same size as the wavelength of light. Rayleigh scattering occurs when particles are smaller than the wavelength [72,73]. Figure 3d illustrates two techniques that can be used to measure light scattering in an ink material. The first technique is turbidimetry, in which light scattering is determined by measuring the decrease in intensity of the light beam after passing through the ink material. The second technique is nephelometry, in which light scattering is determined by measuring light at an angle (90°) away from the incident light passing through the ink material (Figure 3d).

4.2. Scattering Inhibition Methods

Achieving improved resolutions in DLP 3D printed constructs with light scattering problems has remained a technological challenge. To overcome resolution deterioration due to light scattering in hydrogel 3D printing, You et al. [57] developed a DLP method called flashing photopolymerization (FPP). In contrast to conventional DLP platforms where light is exposed continuously, light exposure to the vat is applied in millisecond scale flash portions in flashing polymerization. Since the flash exposure, the prepolymer negligibly scatters light; the polymerization takes place without penetrating continuous light into the environment. This leads to the exposure pattern being less perturbed by light scattering. Figure 2c shows the schematic diagram and resolution of prototypes constructed with this technique. Implementation of machine learning approaches in 3D printing is another strategy used in developing improved resolution DLP printers. You et al. [36] have developed a sophisticated neural networks algorithm to control light-material interactions to mitigate the scattering effects.

Another strategy to control the scattering effects is the addition of photo absorbers which work like light attenuators by absorbing excess light, which improves the pattern fidelity. Several researchers have reported some forms of light absorption or polymerization inhibition to reduce scattering, resulting in more accurate features. Zissi et al. [74] showed that cure width and depth could be decreased using a photo absorber, and these effects were established as a function of the concentration of the photo absorber in the ink solution. The quality of a 3D printed structure is related to the curing properties of each layer. It is essential to acquire insight into the relationship between the photo absorber composition, gelation kinetics for the layer formation, and its mechanical properties. Khairu et. al [75] used a photo absorber (Sudan I) to control the UV penetration for fabricating 3D microstructures in UV micro stereolithography. Yan Yang et. al [71] evaluated the impact of various photo absorbers (i.e., methylene blue, coccine, and tartrazine) over the photocuring process and printing fidelity (printability of convex cone and vertical channel). With the highest absorbance at 405 nm, tartrazine was the most effective photo absorber in slowing down the photocuring reaction. As illustrated in Figure 3e-i, the height of the printed cone (Φ = 1.5 mm) was not different after adding methylene blue or coccine. By adding tartrazine, the height of the cone decreased, which revealed that tartrazine was able to slow down light-induced crosslinking reaction. The depth of the internal vertical channel (Φ = 1.5 mm) increased after tatrazine was added as a photo absorber, enabling minimization of light scattering into the channel. This slowed down the overturning of the nonprinted area and allowed the printability of internal structures. This improvement in printing accuracy of the inner channel was related to the absorption of light scattering into the channel by tartrazine [71]. Grigoryan et al. demonstrated that adding tartrazine in PEGDA hydrogels can decrease light scattering for improved-resolution fabrication of an alveolar model topology with a voxel resolution of ~ 5 μm with perusable open channels measuring as small as 300 μm in diameter [45].

Adding inorganic gold nanoparticles, which are biocompatible for tissue bioprinting, has also been reported as a viable strategy to attenuate light scattering. By controlling the diameter of the nanoparticle, the peak absorbance can also be controlled [76]. The interaction between light and spherical nanoparticles can be described using the Mie theory [77]. Mie theory calculations determine the theoretical absorption and scattering cross sections, the sum of which is equal to the total extinction. This can be used to predict light scattering during DLP printing.

4.3. Light Absorption Photo-Chemistry

Photopolymerization includes the reaction of monomers that creates large networks once irradiated with UV light via the chemical absorption of photons. Absorption is regulated by Beer’s law, when using monochromatic beams [31]. It correlates this absorption to the wavelength of the incident light. With I0 being the intensity of the radiation that enters the ink material and I the power of the radiation that goes across, the transmittance T is given by T= I/I0. Beer’s law can be expressed as:

| (1) |

Where b is the thickness of the box, c is the concentration of the sample in the solution and a is the capacity of the sample to absorb radiation. Beer-Lambert law can be simplified to A= abc, where A is the absorbance and is expressed as:

Beer’s law says that the concentration and the absorbance are linearly proportional (for a constant thickness and radiation wavelength). The dispersion/scattering and absorption are conditioned by the wavelength and the increase in the blue region of the electromagnetic spectrum compared to the red and infrared regions. This absorption can be aroused by the reactant monomer or by a photoinitiator’s transference of absorbed energy. When photoinitiators are exposed to light, they generate free radicals which react with monomers and oligomers and initiate the polymer chain reaction and growth. Photoinitiators are vital elements for photocrosslinking in DLP printing [78].

4.4. Photopolymerization Kinetics

The equations derived in the Supplementary Material show the role of photoinitiator concentration, its extinction coefficient, exposure time, and light intensity on curing depth in a DLP printer. Figure 4 shows that there exists an optimal photoinitiator concentration (a threshold concentration) in the ink formulation to achieve the highest curing depth during the printing each layer.

Figure 4-.

3D curves and relevant 2D contour plots to address the dependence of the curing depth on the photoinitiator concentration and (a) the light intensity at fixed exposure time, t=0.2 s, (b) the exposure time at fixed light intensity, , in a DLP printing platform. The ink chemical properties (α and ε parameters) obtained from Lee et al. [79].

The optimal photoinitiator concentration nonlinearly decreases with increasing light intensity (Figure 4a and Eq. S10) and increasing exposure time (Figure 4b and Eq. S10). Increasing light intensity beyond a conventional range is limited to costly powerful LED/light sources. Increasing the exposure time is accessible through programming the DMD chip. However, it decreases the speed of printing. In layer-by-layer 3D fabrication, the exposure time and the curing depth of each layer determine the speed of 3D printer. Redundant intensity, exposure time, and photoinitiator concentration give rise to light scattering, leading to overcuring and deteriorated resolution. More details are discussed in Supplementary Material’s section about calculations of the optimal photoinitiator concentration in a DLP setup. In summary, engineers have to consider the light-matter interaction equations, including fabrication parameters and ink material variables, to control the printing quality when setting optimal conditions for a DLP platform. The next section is devoted to providing insight into the chemical properties and molecular structure of inks used in DLP platforms.

5. Ink Selection

5.1. General Guidelines

Table 2 summarizes the main compositions used as an ink material to benchmark DLP platforms. PEGDA of molecular weight between 250 and 700 Da at concentrations between 10 to 50 % v/v in water is a material used to improve the printing resolution. PEGDA is not a suitable material to test cell printability since cells do not attach to PEGDA scaffolds. GelMA (~ 5-15 % w/v) provides a lower printing resolution owing to a lower concentration of polymer content, higher molecular weight of the polymer, and higher light scattering, compared to PEGDA. Due to improved cell attachment to gelatin macromers, GelMA is useful for conducting cell studies with DLP platforms. Mixing PEGDA with GelMA can lead to a balanced printing resolution and cell attachment. The hydrogel constructs fabricated by these polymers are brittle. Chitosan methacrylate (CHI-MA) hydrogels in the presence of LAP as a photoinitiator with blue light (405 nm) are attractive alternatives owing to their enhanced mechanical properties, tailorable grafting degree, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [80].

Table 2.

Common ink compositions for DLP printing

| Ink | Initiator | Absorber | Feature size | Biocompatibility | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GelMA (15%w/v) | UCNP@LAP | No Dye | 150 μm- 1 cm | High | [54] |

| CHI-MA (1 %w/v) | LAP | No Dye | 50 μm- 1 cm | High | [81] |

| CMC-MA (2 %w/v) | LAP | No Dye | 100 μm- 1 cm | High | [82] |

| SF-GMA (10-30 %w/v) | LAP | No Dye | 100 μm- 3 cm | High | [83] |

| SF-PEG4A (2 %w/v) | Eosin Y | No Dye | 500 μm- 1 cm | High | [84] |

| PVA-MA (10 %w/v), PEGDA (40 %v/v) | Ru:SPS | Ponceau-Red | 500 μm-1 cm | High | [61,70] |

| GelMA (10 %w/v), PEGDA (10 %v/v) | Eosin Y | A Food Dye | 500 μm-1 cm | Medium | [55,63] |

| PEGDA (25 %v/v)-GelMA (7.5 %w/v) | LAP | No Dye | 100 μm-5 cm | High | [52] |

| PEGDA (20 %w/v) | LAP | Tartrazine (Organic dye) | 100 μm-3 cm | High | [64] |

| HAMA, GelMA (20 %w/v) | LAP | No Dye | 200 μm-6 mm | High | [68,69] |

| BPADA-GMA-BA (69:23:8) | Irga819 | Sudan I | 200 μm-6 mm | NA | [10] |

| GelMA-PEGDA | LAP | A Food Dye | 15 μm-2 cm | Low | [6] |

| PEGDA (20 to 50 %v/v), GelMA (5%w/v) | LAP | No Dye | 100 μm-2 mm | Medium | [57,58,67] |

| GelMA-PEGDA (10 %w/v), GelMA (2.5%w/v)-HA (1 %w/v), GelMA (10%w/v)-GMHA (1%w/v) | LAP | A Food Dye | 10 μm-5 mm | Medium | [2,46,59,65,66] |

| PETA (95 %w/v) | DCPI | No Dye | 20 μm-5 cm | NA | [60] |

NA: not applicable; UCNP @ LAP: LAP coated on an Up-Conversion Nano Particle; GelMA: gelatin methacrylate; CHI-MA: chitosan methacrylate; CMC-MA: carboxymethyl cellulose methacrylate; SF-GMA: silk fibroin produced by a methacrylation process using glycidyl methacrylate; HAMA: hyaluronic acid methacrylate; PVA-MA: poly-vinyl alcohol methacrylate; PEGDA: Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate; SF-PEG4A: silk fibroin (SF) incorporated 4-arm polyethylene glycol acrylate; BPADA: bisphenol A ethoxylate diacrylate; GMA: glycidyl methacrylate; BA: n-butyl acrylate; PETA: pentaerythritol tetraacrylate.

Depending on the application, some studies incorporate other inks such as HAMA, SF-GMA, SF-PEG4A PVA-MA, or BPADA-GMA-BA [2,10,46,59,61,65,66,70]. To achieve biocompatibility, it is necessary to use cell friendly photoinitiators such as Ru:SPS or LAP [4]. Depending on the wavelength of the light source, several dyes, as shown in Table 2, can be incorporated into the ink formulation for absorbing the scattered light and increasing printing resolution. The largest and smallest feature sizes printed by different DLP platforms are shown in Table 2. Most of DLP platforms are capable of printing large features of centimeter size scale in one-time exposure. This is considered large enough for additive manufacturing of industrial models and tissue building blocks. The smallest printable feature size fits in a wide range between 10 μm and 500 μm, depending on the ink material composition and optic design used for the DLP platform.

In summary, PEGDA is helpful to test the resolution of printing 3D structures, while GelMA and HAMA are useful to test the cell compatibility of the platform to print cell-laden hydrogel constructs. These 3D printed hydrogels show brittleness and low mechanical properties. CHI-MA, PVA-MA, SF-GMA, and SF-PEG4A are candidate photocrosslinkable biomaterials to test the platform’s ability to print constructs of stronger mechanical properties. PETA and BPADA-GMA-BA provide higher mechanical properties at the cost of lower biocompatibility.

5.2. Ink Molecular Structures

A DLP printing ink is composed of a mixture of monomers including functional groups (acrylate or vinyl), a light sensitive initiator and a photo absorber if needed. Correct choice of fillers in the photocurable ink formulation allows to tailor functional properties for the printed constructs. Molecular structures of main monomers used as a DLP printing ink are classified and illustrated in Table 3. Most DLP printers make use of inks comprised of an acrylate functional group in their molecular structure. Other ink formulations which implement thiol or thiol–acrylate based vitrimers need toxic photoinitiators [85,86]. In ink molecular structure, acrylate functional groups can show up as either a repeating side group (i.e., pendant) or as an end-group (i.e., termination). In following section, examples of pendant and termination formulations are summarized.

Table 3.

Molecular structure of DLP printing inks

|

|

|

‘-’: not enough data reported with a DLP platform comparable to other studies; Mw: molecular weight; UDMA: diurethane dimethacrylate; HEMA: 2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate; DMA: dimethyl acrylamide; TMPTA: trimethylolpropane triacrylate; IBOA: isobornyl acrylate; ACMO: 4-acryloylmorpholine.

5.2.1. Pendant Formulations

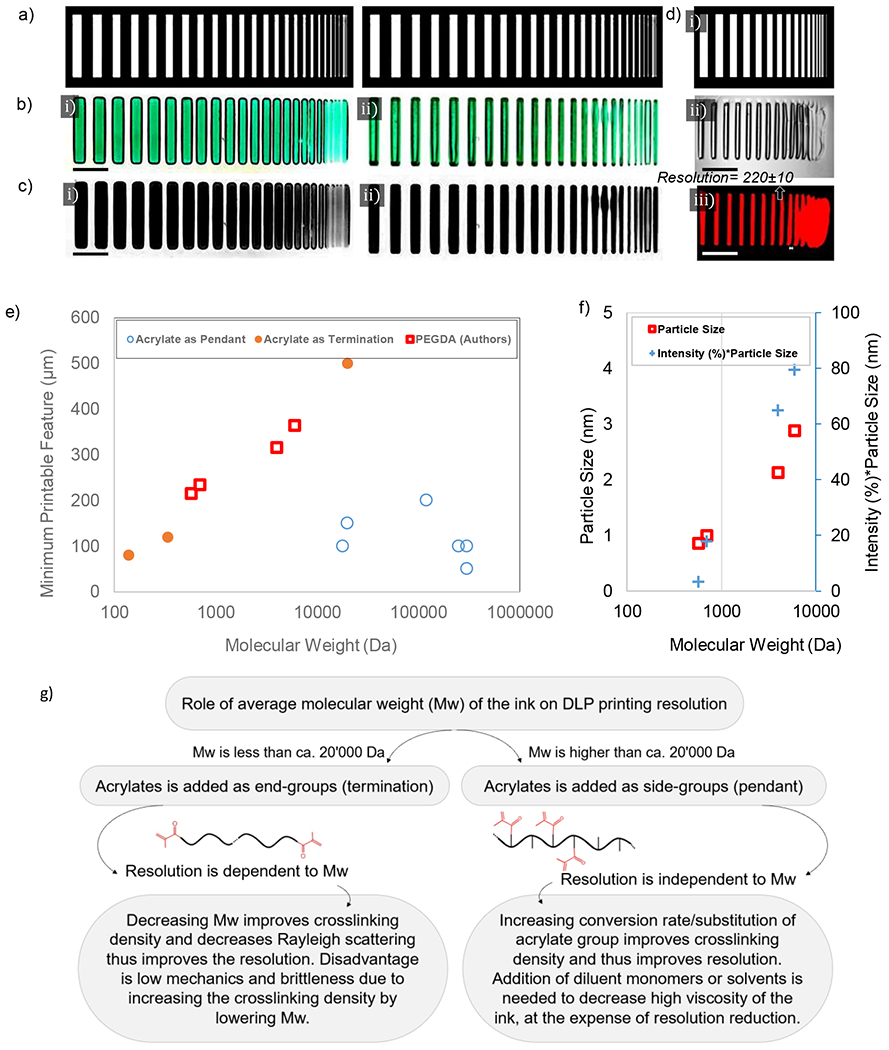

Examples of monomers with acrylate pendant groups, are gelatin methacrylate [54], chitosan methacrylate [81], carboxymethyl cellulose methacrylate [82], hyaluronic acid methacrylate [68,69,87], poly-vinyl alcohol methacrylate [47], and silk fibroin produced by a methacrylation process using glycidyl methacrylate [83]. Majority of these inks show good water solubility, low toxicity, and biocompatibility. Their monomer molecular weight is in a wide range between 18’000 Da and 300’000 Da while the obtained resolution during DLP printing is non relevant to the monomer molecular weight (Figure 5e). Increasing the substitution of acrylate as a side group on the backbone of the monomer (i.e., conversion ratio) can increase DLP printing resolution.

Figure 5. Role of molecular structure on obtained resolution during DLP printing;

a) used photomask for DLP printing of PEGDA; b) printed structures achieved from (i) PEGDA 6000 Da and (ii) PEGDA 700 Da (3 mM Ru:SPS), scale bar 5 mm; c) same patterns after removing background in grayscale mode; d) parallel lines photomask (i), obtained pattern under optical microscopy (ii), obtained pattern under fluorescent microscopy when Comarin 6 is used (iii) and the demonstration of estimated resolution based on the thinnest printable line, scale bar 1 mm; e) variations of the minimum printable feature size obtained from different formulations shown in Table 3 and the authors measurements on PEGDA samples; f) particle size obtained by DLS for uncrosslinked PEGDA samples of different molecular weights where size of particles are much smaller than the laser wavelength, ca. 200 nm; g) decision tree to help improving resolution of DLP printing based on the ink molecular structure.

5.2.2. Termination Formulations

Examples of monomers which use acrylate as a terminal group include polyethylene glycol diacrylate [64], bisphenol A ethoxylate diacrylate [10], diurethane dimethacrylate [60], and silk fibroin incorporated 4-arm polyethylene glycol acrylate [84]. Here, small size monomers such as pentaerythritol tetraacrylate [60], hydroxyethyl methacrylate [60], dimethyl acrylamide [1], trimethylolpropane triacrylate [1], isobornyl acrylate and acryloylmorpholine [88] can also be implemented. These monomers with a proper photoinitiator [4] are used as an ink in DLP platforms. Increasing the monomer molecular weight decreases the density of acrylate per volume of the ink which reduces the resolution of DLP. In PEGDA where acrylate is used as termination, it is expected that decreasing the molecular weight of PEG increases the acrylate density and increases DLP printing resolution. We showed this phenomenon in a macroscopic scale in Figure 5c-i for PEGDA 6000 Da (impaired resolution) and Figure 5c-ii for PEGDA 700 Da (improved resolution) where similar photoinitiator content and exposure time are applied to print both samples at 12.5% w/v polymer content.

5.3. Role of Monomer Molecular Weight

The role of monomer molecular weight on printing resolution has been disregarded. Printing resolution depends on optical design and material characteristics. The resolution (i.e., the minimum width of lines printed with DLP) versus the average monomer molecular weight based on data in Table 3 and authors’ measurements is shown in Figure 5e. A ‘parallel lines’ photomask with varying width (see Figure 5d-i) was used to crosslink PEGDA (20 wt.%) with different molecular weights (575, 700, 4000 and 6000 Da). Figure 5d-iii shows the resolution of printing (narrowest printable line; see also Supplementary Table S1). The feature size is increased proportional to the average of monomers molecular weight (for acrylate as termination). Increasing the molecular weight increases the light scattering due to the presence of larger macromolecules which enhances Rayleigh scattering and decreases the resolution of printing. Figure 5f illustrates the results of dynamic light scattering (DLS) performed on uncrosslinked PEGDA. The results show that increasing the molecular weight forms larger nanometer size particles with higher population (i.e., intensity) which enhances the light scattering. Note that Figure 5f is devoted to particle sizes much smaller than the DLS laser light wavelength, ca. 200 nm. Increasing the particle size by increasing the molecular weight enhances the Rayleigh scattering and decreases the printing resolution. Table 3 shows that if monomer molecular weight is above 20’000 Da, acrylate is used as a pendant in ink formulation. Figure 5e implies that in this situation the minimum printable feature size is irrelevant to the monomer molecular weight. Figure 5g summarizes this information by providing a decision tree for enhancing DLP printing resolution based on the ink molecular structure.

5.4. Role of Ink Viscosity

It is worth noting that the viscosity and solubility of some inks in the solvent significantly change by increasing their monomer molecular weight. For instance, by increasing the molecular weight of hyaluronic acid from 100’000 Da to 1’000’000 Da, the viscosity of HAMA at a fixed polymer content increases. To use the ink in a DLP platform, one should adjust the ink viscosity by decreasing polymer content (or increasing the solvent). This in turn decreases the acrylate density per volume of the ink and can reversely attenuate DLP printing resolution.

In high molecular weight inks, acrylate or vinyl groups were attached as a side group, pendant, to the backbone of molecular structure. The density of acrylate groups remains constant by increasing the molecular weight; thus, no significant change was observed in obtained resolution during DLP printing. These formulations included GelMA, HAMA, CHI-MA, CMC-MA, SF-GMA, and PVA-MA. In low molecular weight inks, acrylate or vinyl groups were attached as an end group, termination, to the backbone of molecular structure. Increasing the molecular weight reduces the relative density of acrylate groups and enhances light scattering. Therefore, increasing molecular weight could decrease the printing resolution or increase DLP’s minimum printable feature size. The next section represents future trends in DLP printing, including emerging techniques for multi-material and 4D fabrication.

6. Future Directions

6.1. Inks Enabling 4D Printing Mechanisms

One of the current trends in fabrication is creating dynamic constructs with time-dependent properties. According to the 4D printing concept [87,89], a 3D printed structure undergoes time-dependent self-transformation in shape, properties, or functionality when exposed to predetermined stimuli such as light [90], heat [10,91], magnetic field, or electrical field [92], humidity [93], and changes in pH [87,94]. Table 4 summarizes the inks used for 4D printing in DLP platforms. Different mechanisms governing on 4D stimulation of DLP printed products are shown in Table 4, which can be classified into two main tools. One tool consists of thermally activated microstructural transformation. The thermally activated change can be due to the shape memory behavior of the DLP printed material [10,91,92] or due to microstructural evolution in a DLP printed polymer foam [95]. The next mechanism consists of humidity-activated transformation, including non-reversible shape transformation [87,93,94] or reversible color transformation [90] due to water content variations in the environment. It is advantageous if the polymer can demonstrate the reversibility of the 4D transformation, which is provided by physical/chemical crosslinking and a reversible stimulus. 4D printing is still in its infancy, and few ink formulations are recognized till now with potential reversible 4D applications in DLP platforms [90]. Implementing molecular motors or photoswitches such as azobenzene and arylazopyrazole [96] in the ink molecular structure is a promising future direction in 4D DLP printing because they provide tunable, time-dependent and reversible properties [97] to the printed samples after 3D printing.

4D printing typically intends to include significant shape transformations from the initially printed geometry to the final activated stage. To fabricate a complex structure, one should consider nonlinear mechanical modeling at large deformations to predict the final shape from the as-printed form of the system. Most polymers often exhibit nonlinear, visco-hyperelastic behavior. Functionality transformation is a time-dependent, transient process. It is more challenging to define or quantify resolution in 4D printing than conventional 3D DLP printing. In hydrogel systems, 4D DLP printing is possible either through the capability of the ink for gradient crosslinking (to exploit the humidity-activated mechanism) or through an engineered gradient distribution of (nano-)particles during printing (to introduce a thermally activated tool). Few ink formulations have to shown good capabilities for gradient crosslinking at the molecular level toward the 4D printing [87,93,94].

6.2. Inks for Multi-Material Fabrication

Regarding the need for composite structures for biomanufacturing, recent efforts have been made to use advanced 3D printing to create complex, multi-component, micro-tissue models with a controlled cell-ECM-vasculature complex. DLP printing method benefits from a good speed and easy control over the mechanical properties of inks and a superior resolution down to ~ 10 μm compared to other methods. The X-Y resolution can approach around ~ 10 μm [2] (while ~ 1 μm for non-cellular inks), and the fabrication speed is typically between 0.5 and 10 mm/s (reaching 100 mm/s for non-cellular inks). Ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths are used for the rapid fabrication of tissue constructs by the DLP method. Applying other wavelengths, such as the green light, is less studied in the literature. Thus, DLP methods seem to be an ideal fit for the rapid fabrication of multi-material microtissues. The main issues are the compatibility of different inks used to material exchange and how the interactions can impact their optical properties. A combination of standard inks introduced in Table 2 may be utilized for multi-material DLP printing, provided all components can be dissolved in similar solvents. Table 3 provides information on the water solubility of typical monomers used in DLP ink formulations to check this condition. The tables would help to select a proper set of inks for multi-material fabrication.

7. Conclusions

This review covered (i) challenges in using different materials for multi-material printing, to be solved using microfluidic and dual-color photocrosslinking; (ii) challenges in improving resolution, to be solved by proper choice of inks, optical hardware, flashing photopolymerization, and others; and (iii) challenges in formulating inks and photoinitiator systems, to be addressed by light sheet technology and photoswitch systems. A detailed guideline was presented to help engineers in fabricating functional structures at improved resolutions. Light-material interactions such as refraction, scattering, and absorption phenomena were discussed for optimizing the fabrication process. The size of scattering particles and photon scattering were used to explain how to measure the quality of the DLP process. The roles of light wavelength, intensity, exposure time, and ink chemistry such as photoinitiator content, its molar absorptivity, and molecular structure of the ink monomer were explained on the curing depth or the effective resolution. Analysis of previous reports showed that decreasing the light wavelength improves the resolution in DLP platforms (see Table 1).

The photocrosslinking in DLP printers was modeled by theoretical optics to discover the correlation between the curing depth and the set of light parameters: exposure time, light intensity, and photoinitiator content. The phenomenological relationships revealed the nonlinear dependence of the photocuring depth on the process parameters and ink photochemistry. A photoinitiator threshold exists in the ink formulation, which allows achieving the highest curing depth in layer-by-layer printing [98]. Increasing light intensity beyond a conventional range increases fabrication costs, while improving the exposure time decreases printing speed, a hallmark of DLP printing. In layer-by-layer printing, the exposure time and the curing depth control the rate of fabrication. Redundant intensity, exposure time, and photoinitiator concentration raises light scattering, leading to overcuring and deteriorated resolution. Thus, engineers have to consider the light-matter interaction equations and fabrication parameters to control the printing quality.

We used experimental data to elucidate the role of monomer molecular weight on the resolution of DLP printing. In low molecular weight inks, acrylate groups were attached as an end group to the backbone of molecular structure. With increasing molecular weight, the relative density of acrylate groups was reduced while light scattering was enhanced, resulting in a decreased printing resolution. In high molecular weight inks, acrylate groups were attached as a side group, and the printing resolution was independent of the molecular weight as the density of acrylate groups remained constant with an increasing molecular weight. Thus, no significant change was observed in the obtained solution during DLP printing. General guidelines about ink material selection were given to achieve an improved resolution (Figure 5). Future trends in DLP printers for 4D and multi-material fabrication were discussed (Table 4). The discussions help material scientists and engineers select the proper combination of materials, photoinitiators, and optical parameters to improve 3D printing resolution in a DLP setup.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This review focuses on ink selection and design parameters for DLP-printing of soft structures

DLP strategies that improve the level of automation are summarized to overcome DLP limitations

The role of the ink chemistry and monomer molecular structure in performance of DLP are discussed

The kinetics of light absorption and photopolymerization reaction in DLP are explained

A roadmap is provided to select proper sets of DLP parameters and ink formulation for desired demand

Acknowledgments

Hossein G. Hosseinabadi acknowledges the receipt of fellowship award funding by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation during this research. Amir K. Miri acknowledges the receipt of a start-up fund from NJIT and R01-DC018577 from NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Ahn D, Stevens LM, Zhou K, Page ZA, Rapid High-Resolution Visible Light 3D Printing, ACS Cent. Sci 6 (2020) 1555–1563. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Miri AK, Nieto D, Iglesias L, Goodarzi Hosseinabadi H, Maharjan S, Ruiz-Esparza GU, Khoshakhlagh P, Manbachi A, Dokmeci MR, Chen S, Shin SR, Zhang YS, Khademhosseini A, Microfluidics-Enabled Multimaterial Maskless Stereolithographic Bioprinting, Adv. Mater 30 (2018) 1–9. 10.1002/adma.201800242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lu Y, Mapili G, Suhali G, Chen S, Roy K, A digital micro-mirror device-based system for the microfabrication of complex, spatially patterned tissue engineering scaffolds, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part A 77 (2006) 396–405. 10.1002/jbin.a.30601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goodarzi Hosseinabadi H, Dogan E, Miri AK, Ionov L, Digital Light Processing Bioprinting Advances for Microtissue Models, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 8 (2022) 1381. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.lc01509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Absolute Reports® - Market research Reports and Industry Analysis Reports, (n.d.). https://www.absolutereports.com/ (accessed February 14, 2022).

- [6].Bhusal A, Dogan E, Nguyen H-A, Labutina O, Nieto D, Miri AK, Multi-material digital light processing bioprinting of hydrogel-based microfluidic chips, Biofabrication. 14 (2022) 014103. 10.1088/1758-5090/ac2d78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen H, Wang H, Lv P, Wang Y, Sun Y, Quantitative evaluation of tissue surface adaption of CAD-designed and 3D printed wax pattern of maxillary complete denture, Biomed Res. Int 2015 (2015). 10.1155/2015/453968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kong Y, Application of 3D Printing Technology in Jewelry Design in the Era of Artificial Intelligence, Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput 1343 (2021) 162–169. 10.1007/978-3-030-69999-4_22/COVER. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Saorin JL, Diaz-Alemán MD, De La Torre-Cantero J, Meier C, Pérez Conesa I, Design and validation of an open source 3D printer based on digital ultraviolet light processing (DLP), for the improvement of traditional artistic casting techniques for microsculptures, Appl. Sci 11 (2021)3197. 10.3390/appll073197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kuang X, Wu J, Chen K, Zhao Z, Ding Z, Hu F, Fang D, Qi HJ, Grayscale digital light processing 3D printing for highly functionally graded materials, Sci. Adv 5 (2019). 10.1126/SCIADV.AAV5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dogan E, Bhusal A, Cecen B, Miri AK, 3D Printing metamaterials towards tissue engineering, Appl. Mater. Today 20 (2020). 10.1016/j.apmt.2020.100752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ, Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030, Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract 87 (2010) 4–14. 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shapiro AMJ, Pokrywczynska M, Ricordi C, Clinical pancreatic islet transplantation, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 13 (2017)268–277. 10.1038/nrendo.2016.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bruni A, Gala-Lopez B, Pepper AR, Abualhassan NS, James Shapiro AM, Islet cell transplantation for the treatment of type 1 diabetes: Recent advances and future challenges, Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther 7 (2014) 211–223. 10.2147/DMSO.S50789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Theus AS, Ning L, Hwang B, Gil C, Chen S, Wombwell A, Mehta R, Serpooshan V, Bioprintability: Physiomechanical and biological requirements of materials for 3d bioprinting processes, Polymers (Basel). 12 (2020) 1–19 10.3390/polyml2102262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nakamura O, Kawata S, Maruo S, Three-dimensional microfabrication with two-photon-absorbed photopolymerization. Opt. Lett Vol. 22, Issue 2, Pp. 132–134. 22 (1997) 132–134. 10.1364/OL.22.000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hosseinabadi HG, Bagheri R, Avila Gray L, Altstädt V, Drechsler K, Plasticity in polymeric honeycombs made by photo-polymerization and nozzle based 3D-printing, Polym. Test 63 (2017) 163–167. 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2017.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goodarzi Hosseinabadi H, Bagheri R, Altstädt V, Shear band propagation in honeycombs: numerical and experimental, Rapid Prototyp. J 24 (2018). 10.1108/RPJ-06-2016-0098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gu Z, Fu J, Lin H, He Y, Development of 3D bioprinting: From printing methods to biomedical applications, Asian J. Pharm. Sci 15 (2020) 529–557. 10.1016/j.ajps.2019.ll.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kowsari K, Lee W, Yoo SS, Fang NX, Scalable visible light 3D printing and bioprinting using an organic light-emitting diode microdisplay, IScience. 24 (2021) 103372. 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hwang HH, Zhu W, Victorine G, Lawrence N, Chen S, 3D-Printing of Functional Biomedical Microdevices via Light- and Extrusion-Based Approaches, Small Methods. 2 (2018) 1–18. 10.1002/smtd.201700277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Song P, Li M, Zhang B, Gui X, Han Y, Wang L, Zhou W, Guo L, Zhang Z, Li Z, Zhou C, Fan Y, Zhang X, DLP fabricating of precision GelMA/HAp porous composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering application, Compos. Part B Eng 244 (2022) 110163. 10.1016/J.COMPOSITESB.2022.110163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang B, Wang W, Gui X, Song P, Lei H, Li Z, Zhou C, Fan Y, Zhang X, 3D printing of customized key biomaterials genomics for bone regeneration, Appl. Mater. Today 26 (2022) 101346. 10.1016/j.apmt.2021.101346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mazzocchi A, Soker S, Skardal A, 3D bioprinting for high-throughput screening: Drug screening, disease modeling, and precision medicine applications, Appl. Phys. Rev 6 (2019). 10.1063/l.5056188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Samavedi S, Joy N, 3D printing for the development of in vitro cancer models, Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng 2 (2017) 35–42. 10.1016/j.cobme.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Blaeser A, Duarte Campos DF, Fischer H, 3D bioprinting of cell-laden hydrogels for advanced tissue engineering, Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng 2 (2017) 58–66. 10.1016/j.cobme.2017.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Samavedi S, Joy N, 3D printing for the development of in vitro cancer models, Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng 2 (2017) 35–42. 10.1016/j.cobme.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Miri AK, Mostafavi E, Khorsandi D, Hue S-K, Malpica M, Kkhademhosseini A, 12, Khademhosseini, Bioprinters for organs-on-chips, Biofabrication,. (2019) 0–23. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2053-1583/abe778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Miri AK, Khalilpour A, Cecen B, Maharjan S, Shin SR, Khademhosseini A, Multiscale bioprinting of vascularized models. Biomaterials. 198 (2019) 204–216. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Melchels FPW, Feijen J, Grijpma DW, A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering, Biomaterials. 31 (2010) 6121–6130. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hull CW. Arcadia C. United States Patent (19) Hull (54) (75) (73) 21) 22 (51) 52) (58) (56) APPARATUS FOR PRODUCTION OF THREE-DMENSONAL OBJECTS BY STEREO THOGRAPHY, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Blaeser A, Duarte Campos DF, Fischer H, 3D bioprinting of cell-laden hydrogels for advanced tissue engineering, Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng 2 (2017) 58–66. 10.1016/j.cobme.2017.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nielsen AV, Beauchamp MJ, Nordin GP, Woolley AT, 3D Printed Microfluidics, Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem 13 (2020) 45–65. 10.21146/annurev-anchem-091619-102649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhang B, Gui X, Song P, Xu X, Guo L, Han Y, Wang L, Zhou C, Fan Y, Zhang X, Three-Dimensional Printing of Large-Scale, High-Resolution Bioceramics with Micronano Inner Porosity and Customized Surface Characterization Design for Bone Regeneration, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022. ) 8804–8815. 10.1021/ACSAMI.lC22868/SUPPL_FILE/AMlC22868_SI_005.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].von Horst C, www.plastinate.com, HC Biovision, Ger (2020). www.plastinate.com (accessed October 7, 2022).

- [36].You S, Guan J, Alido J, Hwang HH, Yu R, Kwe L, Su H, Chen S, Mitigating scattering effects in light-based three-dimensional printing using machine learning, J. Manuf Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 142 (2020) 1–10. 10.1115/l.4046986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Catros S, Fricain JC, Guillotin B, Pippenger B, Bareille R, Remy M, Lebraud E, Desbat B, Amédée J, Guillemot F, Laser-assisted bioprinting for creating on-demand patterns of human osteoprogenitor cells and nano-hydroxyapatite, Biofabrication. 3 (2011). 10.1088/1758-5082/3/2/025001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Farsari M, Chichkov BN, Materials processing: Two-photon fabrication, Nat. Photonics 3 (2009) 450–452. 10.1038/nphoton.2009.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].You S, Li J, Zhu W, Yu C, Mei D, Chen S, Nanoscale 3D printing of hydrogels for cellular tissue engineering, J. Mater. Chem. B 6 (2018) 2187–2197. 10.1039/c8tb00301g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wu D, Zhao Z, Zhang Q, Qi HJ, Fang D, Mechanics of shape distortion of DLP 3D printed structures during UV post-curing, 2019. 10.1039/c9sm00725c. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [41].Kumbhar NN, Mulay AV, Post Processing Methods used to Improve Surface Finish of Products which are Manufactured by Additive Manufacturing Technologies: A Review, J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 99 (2018) 481–487. 10.1007/s40032-016-0340-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhang J, Hu Q, Wang S, Tao J, Gou M, Digital light processing based three-dimensional printing for medical applications, Int. J. Bioprinting 6 (2020) 12–27. 10.18063/ijb.v6il.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhu W, Ma X, Gou M, Mei D, Zhang K, Chen S, 3D printing of functional biomaterials for tissue engineering, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 40 (2016) 103–112. 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ma X, Liu J, Zhu W, Tang M, Lawrence N, Yu C, Gou M, Chen S, 3D bioprinting of functional tissue models for personalized drug screening and in vitro disease modeling, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 132 (2018) 235–251. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Grigoryan B, Paulsen SJ, Corbett DC, Sazer DW, Fortin CL, Zaita AJ, Greenfield PT, Calafat NJ, Gounley JP, Ta AH, Johansson F, Randles A, Rosenkrantz JE, Louis-Rosenberg JD, Galie PA, Stevens KR, Miller JS, Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels, Science (80-.). 364 (2019) 458–464. 10.1126/SCIENCE.AAV9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ma X, Qu X, Zhu W, Li Y-SS, Yuan S, Zhang H, Liu J, Wang P, Lai CSE, Zanella F, Feng G-SS, Sheikh F, Chien S, Chen S, Deterministically patterned biomimetic human iPSC-derived hepatic model via rapid 3D bioprinting, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113 (2016) 2206–2211. 10.1073/pnas.1524510113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lim KS, Levato R, Costa PF, Castilho MD, Alcala-Orozco CR, Van Dorenmalen KMA, Melchels FPW, Gawlitta D, Hooper GJ, Malda J, Woodfield TBF, Bio-resin for high resolution lithography-based biofabrication of complex cell-laden constructs. Biofabrication. 10 (2018). 10.1088/1758-5090/aac00c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ma X, Dewan S, Liu J, Tang M, Miller KL, Yu C, Lawrence N, McCulloch AD, Chen S, 3D printed micro-scale force gauge arrays to improve human cardiac tissue maturation and enable high throughput drug testing, Acta Biomater. 95 (2019) 319–327. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Liu J, He J, Liu J, Ma X, Chen Q, Lawrence N, Zhu W, Xu Y, Chen S, Rapid 3D bioprinting of in vitro cardiac tissue models using human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, Bioprinting. 13 (2019) e00040. 10.1016/j.bprint.2019.e00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Koffler J, Zhu W, Qu X, Platoshyn O, Dulin JN, Brock J, Graham L, Lu P, Sakamoto J, Marsala M, Chen S, Tuszynski MH, Biomimetic 3D-printed scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair, Nat. Med 25 (2019) 263–269. 10.1038/s41591-018-0296-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Höhne C, Schmitter M, 3D Printed Teeth for the Preclinical Education of Dental Students, J. Dent. Educ 83 (2019) 1100–1106. 10.21815/jde.019.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhu W, Tringale KR, Woller SA, You S, Johnson S, Shen H, Schimelman J, Whitney M, Steinauer J, Xu W, Yaksh TL, Nguyen QT, Chen S, Rapid continuous 3D printing of customizable peripheral nerve guidance conduits, Mater. Today 21 (2018) 951–959. 10.1016/j.mattod.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Osman RB, van der Veen AJ, Huiberts D, Wismeijer D, Alharbi N, 3D-printing zirconia implants: a dream or a reality? An in-vitro study evaluating the dimensional accuracy, surface topography and mechanical properties of printed zirconia implant and discs, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 75 (2017) 521–528. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chen Y, Zhang J, Liu X, Wang S, Tao J, Huang Y, Wu W, Li Y, Zhou K, Wei X, Chen S, Li X, Xu X, Cardon L, Qian Z, Gou M, Noninvasive in vivo 3D bioprinting, Sci. Adv 6 (2020) 1–11. 10.1126/sciadv.aba7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wang Z, Abdulla R, Parker B, Samanipour R, Ghosh S, Kim K, A simple and high-resolution stereolithography-based 3D bioprinting system using visible light crosslinkable bioinks, Biofabrication. 7 (2015). 10.1088/1758-5090/7/4/045009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Grigoryan B, Sazer DW, Avila A, Albritton JL, Padhye A, Ta AH, Greenfield PT, Gibbons DL, Miller JS, Development, characterization, and applications of multi-material stereolithography bioprinting, Sci. Rep 11 (2021) 1–13. 10.1038/s41598-021-82102-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].You S, Wang P, Schimelman J, Hwang HH, Chen S, High-fidelity 3D printing using flashing photopolymerization, Addit. Manuf 30 (2019) 100834. 10.1016/j.addma.2019.100834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Xue D, Wang Y, Zhang J, Mei D, Wang Y, Chen S, Projection-Based 3D Printing of Cell Patterning Scaffolds with Multiscale Channels, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10 (2018) 19428–19435. 10.1021/acsami.8b03867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhong Z, Deng X, Wang P, Yu C, Kiratitanaporn W, Wu X, Schimelman J, Tang M, Balayan A, Yao E, Tian J, Chen L, Zhang K, Chen S, Rapid bioprinting of conjunctival stem cell micro-constructs for subconjunctival ocular injection, Biomaterials. 267 (2021) 120462. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Regehly M, Garmshausen Y, Reuter M, König NF, Israel E, Kelly DP, Chou CY, Koch K, Asfari B, Hecht S, Xolography for linear volumetric 3D printing. Nature. 588 (2020) 620–624. 10.1038/s41586-020-3029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lim KS, Levato R, Costa PF, Castilho MD, Alcala-Orozco CR, van Dorenmalen KMA, Melchels FPW, Gawlitta D, Hooper GJ, Malda J, Woodfield TBF, Bio-resin for high resolution lithography-based biofabrication of complex cell laden constructs, Biofabrication. 10 (2018). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2053-1583/abe778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mizuguchi K, Nagano Y, Nishiyama H, Onoe H, Terakawa M, Multiphoton photoreduction for dual-wavelength-light-driven shrinkage and actuation in hydrogel, Opt. Mater. Express 10 (2020) 1931. 10.1364/ome.399874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Wang Z, Development of a visible light stereolithography-based bioprinting system for tissue engineering, Tianjin University, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Grigoryan B, Paulsen SJ, Corbett DC, Sazer DW, Fortin CL, Zaita AJ, Greenfield PT, Calafat NJ, Gounley JP, Ta AH, Johansson F, Randles A, Rosenkrantz JE, Louis-Rosenberg JD, Galie PA, Stevens KR, Miller JS, Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels, (n.d.). http://science.sciencemag.org/ (accessed August 19, 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [65].Zhu W. Qu X. Zhu J. Ma X. Patel S. Liu J. Wang P. Lai CSE. Gou M. Xu Y. Zhang K. Chen S. Direct 3D bioprinting of prevascularized tissue constructs with complex microarchitecture, Biomaterials. 124 (2017) 106–115. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wang P, Li X, Zhu W, Zhong Z, Moran A, Wang W, Zhang K, Chen S, 3D bioprinting of hydrogels for retina cell culturing, Bioprinting. 12 (2018) 1–6. 10.1016/j.bprint.2018.e00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Liu J, Miller K, Ma X, Dewan S, Lawrence N, Whang G, Chung P, McCulloch AD, Chen S, Direct 3D bioprinting of cardiac micro-tissues mimicking native myocardium, Biomaterials. 256 (2020). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Thomas A, Orellano I, Lam T, Noichl B, Geiger MA, Amler AK, Kreuder AE, Palmer C, Duda G, Lauster R, Kloke L, Vascular bioprinting with enzymatically degradable bioinks via multi-material projection-based stereolithography, Acta Biomater. 117 (2020) 121–132. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lam T, Dehne T, Krüger JP, Hondke S, Endres M, Thomas A, Lauster R, Sittinger M, Kloke L, Photopolymerizable gelatin and hyaluronic acid for stereolithographic 3D bioprinting of tissue-engineered cartilage, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B. Appl. Biomater 107 (2019) 2649–2657. 10.1002/JBM.B.34354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Li W, Wang M, Mille LS, Robledo Lara JA, Huerta V, Uribe Velázquez T, Cheng F, Li H, Gong J, Ching T, Murphy CA, Lesha A, Hassan S, Woodfield TBF, Lim KS, Zhang YS, A Smartphone-Enabled Portable Digital Light Processing 3D Printer, Adv. Mater (2021) 2102153. 10.1002/ADMA.202102153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Yang Y, Zhou Y, Lin X, Yang Q, Yang G, Printability of External and Internal Structures Based on Digital Light Processing 3D Printing Technique, Pharmaceutics. 12 (2020) 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Johnsen S, Widder EA, The physical basis of transparency in biological tissue: ultrastructure and the minimization of light scattering, J. Theor. Biol 199 (1999) 181–198. 10.1006/JTBI.1999.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Watson D, Hagen N, Diver J, Marchand P, Chachisvilis M, Elastic Light Scattering from Single Cells: Orientational Dynamics in Optical Trap, Biophys. J 87 (2004) 1298. 10.1529/BIOPHYSJ.104.042135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Zissi S, Bertsch A, Jézéquel JY, Corbel S, Lougnot DJ, André JC, Stereolithography and microtechniques, Microsyst. Technol 2 (1995) 97–102. 10.1007/BF02739538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Khairu K, Raman I, Mohamed MAS, Ibrahim M, Wahab MS, Parameter optimerization for photo polymerization of microstereolithography, Adv. Mater. Res 626 (2013) 420–424. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.626.420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Kumar S, Aaron J, Sokolov K, Directional conjugation of antibodies tonanoparticles for synthesis of multiplexed optical contrast agents with both delivery and targetingmoieties, (2008) 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wrigglesworth EG, Johnston JH, Mie theory and the dichroic effect for spherical gold nanoparticles: an experimental approach. Nanoscale Adv. 3 (2021) 3530–3536. 10.1039/DlNA00148E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Chen M, Zhong M, Johnson JA, Light-Controlled Radical Polymerization: Mechanisms, Methods, and Applications, Chem. Rev 116 (2016) 10167–10211. 10.1021/ACS.CHEMREV.5B0067L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Lee JH, Prud’homme RK, Aksay IA, Cure depth in photopolymerization: Experiments and theory, J. Mater. Res 16 (2001) 3536–3544. 10.1557/JMR.2001.0485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Shen Y, Tang H, Huang X, Hang R, Zhang X, Wang Y, Yao X, DLP printing photocurable chitosan to build bio-constructs for tissue engineering, Carbohydr. Polym 235 (2020) 115970. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Shen Y, Tang H, Huang X, Hang R, Zhang X, Wang Y, Yao X, DLP printing photocurable chitosan to build bio-constructs for tissue engineering, Carbohydr. Polym 235 (2020) 115970. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Melilli G, Carmagnola I, Tonda-Turo C, Pirri F, Ciardelli G, Sangermano M, Hakkarainen M, Chiappone A, DLP 3D Printing Meets Lignocellulosic Biopolymers: Carboxymethyl Cellulose Inks for 3D Biocompatible Hydrogels, (n.d.). 10.3390/polyml2081655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kim SH, Yeon YK, Lee JM, Chao JR, Lee YJ, Seo YB, Sultan MT, Lee OJ, Lee JS, Yoon S. Il, Hong IS, Khang G, Lee SJ, Yoo JJ, Park CH, Precisely printable and biocompatible silk fibroin bioink for digital light processing 3D printing, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 1–14. 10.1038/s41467-018-03759-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]