Abstract

Objectives:

We provided an overview of the literature on decision aid interventions for family caregivers of older adults with advanced dementia regarding decision making about tube feeding. We synthesized (1) the use of theory during the development, implementation, and evaluation of decision aids; (2) the development, content, and delivery of decision aid interventions; (3) caregivers’ experience with decision aid interventions; and (4) the effect of decision aid interventions on caregivers’ quality of decision-making about feeding options.

Design:

Scoping review.

Methods:

We conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed studies published January 1, 2000eJune 30, 2022, in MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases. The process was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework, which includes identifying the research question, choosing related studies, charting the data, and summarizing results. Empirical articles concerning the decision aid interventions about feeding options were selected.

Results:

Six publications reporting 4 unique decision aid interventions were included. All the interventions targeted caregivers of older adults with advanced dementia. Three decision aids were culturally adapted from existing decision aids. The Ottawa Decision Support Framework and the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Framework were used in these 6 publications. Interventions aimed to improve decision making regarding tube feeding for caregivers through static delivery methods. Caregivers rated these decision aids as helpful and acceptable. Decisional conflict and knowledge of feeding options were the most common outcomes evaluated. Reduction in decisional conflict and increase in knowledge were consistently found among dementia caregivers, but no intervention effects were found on preferences for the use of tube feeding.

Conclusions and Implications:

Decision aid interventions effectively improve decision-making regarding tube feeding among the target population. Cultural adaptation of an existing decision aid intervention is the main strategy. However, the lack of guidance of a cultural adaptation framework in this process may lead to difficulties explaining caregivers’ behavioral changes. Moreover, merely providing information is not enough to change caregivers’ preferences or behavior of use of tube feeding. A systematic approach to cultural adaptation and interactive intervention is needed in future studies.

Keywords: Advanced dementia, dementia caregivers, decision aid, interventions, tube feeding

Dementia is a progressive, incurable disease characterized by cognitive and functional decline.1 Eating problems, the most common clinical complication, affect 86% of patients with advanced dementia.2 When faced with their loved ones’ eating difficulties and weight loss, family caregivers have to make ethically and emotionally difficult decisions about feeding options, that is, whether to initiate tube feeding or to continue hand feeding.3 Althoughf tube feeding has been used to provide nutrition, evidence has shown that it does not benefit individuals with advanced dementia in terms of extending survival, healing pressure ulcers, reducing aspiration, or improving nutritional status.4–7 Nevertheless, a recent 5-state study in the United States found that 11% of patients with advanced dementia are tube fed, revealing the need to improve decision making around feeding options by involving family caregivers.8

Researchers begun to develop and test interventions that focusing on supporting family caregivers’ decision making about feeding options for individuals with dementia. These interventions have primarily taken the form of decision aids–interventions that take a more targeted approach than other educational materials by making the clinical choices explicit, presenting information about options and associated risks and benefits, and assisting in understanding the relationship between decisions and personal values.9 For example, many of the educational materials may not provide comprehensive information about the risks and benefits of each treatment.10 The format of decision aids can be booklets, pamphlets, videos, or web-based tools. Decision aids designed to support family caregivers in decision making about feeding options have been shown to increase knowledge of tube feeding, to decrease decisional conflict, and increase the frequency of discussion about feeding options with health professionals.11 Despite those positive outcomes, how these decision aids have been developed, implemented, and evaluated remains unknown. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review to synthesize the literature across the intervention trajectory and guide the development and modification of family caregiver-oriented decision aid interventions about feeding options. More specifically, we aimed to provide an overview of the literature on decision aid interventions about feeding options for family caregivers by synthesizing (1) the theoretical underpinnings across the decision aid intervention trajectory; (2) the development, content, and delivery of decision aid interventions; (3) family caregivers’ experience with decision aid interventions; and (4) the effect of decision aid interventions on their quality of decision making about feeding options (ie, decisional conflict, knowledge).

Methods

We conducted a scoping review to identify and synthesize how the literature is framing our topic.12 Different from systematic reviews, scoping reviews provide a descriptive overview of the reviewed studies without a critical appraisal.13 We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s 5-step methodological framework13 as outlined below.

Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

The research questions that we used to guide this scoping review were as follows: (1) How has theory been used during the development, implementation, and evaluation of decision aid interventions about feeding options for dementia family caregivers? (2) What has been the content and format of decision aid interventions about feeding options for dementia caregivers? (3) What have user experiences been with these decision aid interventions? and (4) How have decision aid interventions influenced family caregivers’ decision-making quality outcomes?

Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

For this scoping review, we used a systematic search strategy (Supplementary Material 1) and addressed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).14,15 We formulated search terms based on the Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) framework and searched 5 databases, including MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL Complete, and Web of Science Core Collection. Search terms included tube feeding, dementia or cognitive impairment, and decision aids, in combination, with the final search limited to articles published between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2022 (see detailed search terms and results in Supplementary Appendix 1), as a preliminary search demonstrated no studies published on this topic prior to 2000.

Step 3: Study Selection

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) peer-reviewed articles, (2) focused on family caregivers of individuals with advanced dementia, and (3) intervention studies including empirical findings. Exclusion criteria were studies published in languages other than English and studies focused on formal caregivers. Review articles, expert opinion, protocol, and quality improvement process articles were also excluded, although we reviewed their reference lists to identify additional potential studies.

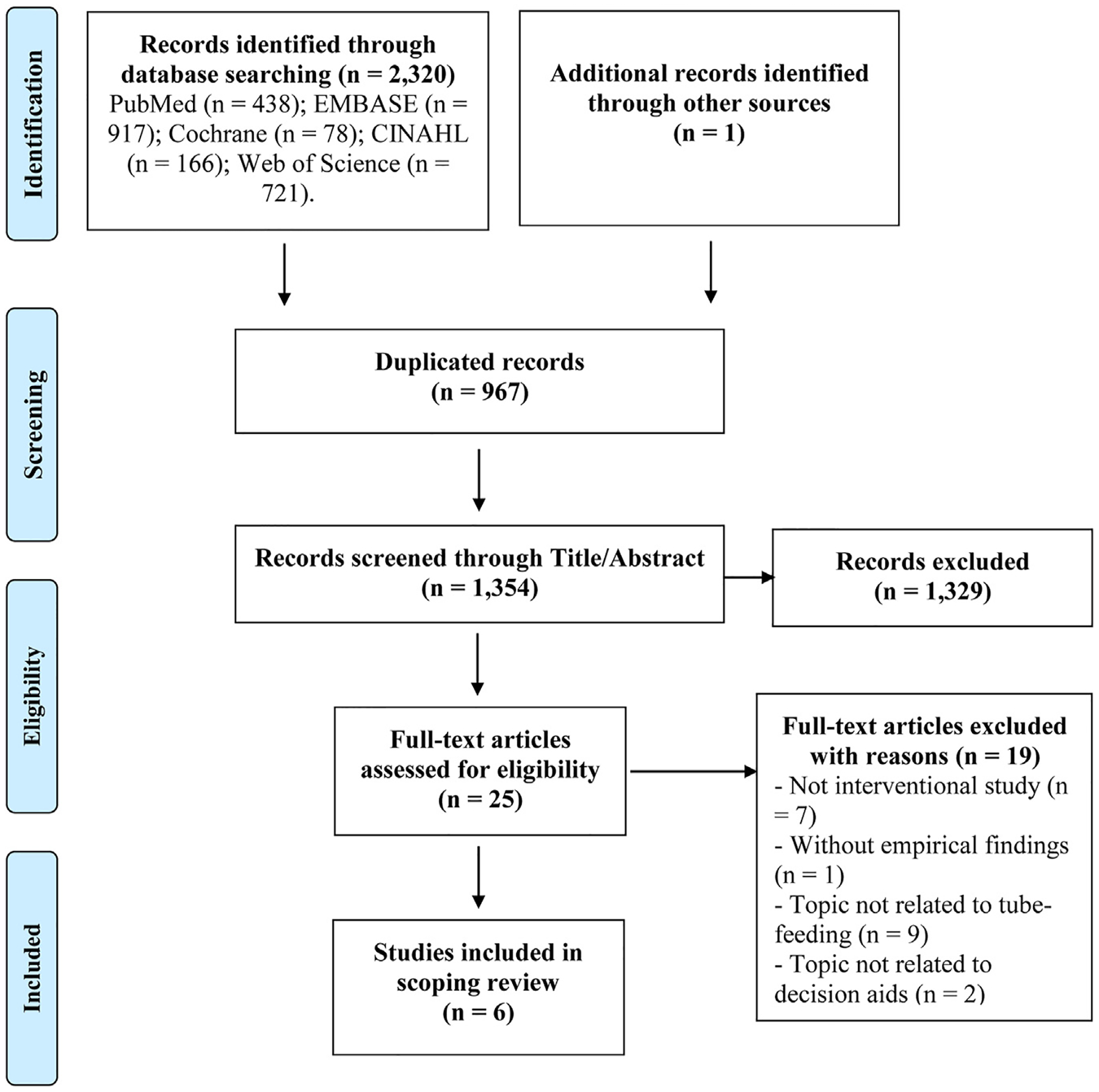

The database search produced 2320 studies for consideration. After duplicates were removed, 967 publications remained. For these articles, we first screened titles and abstracts for inclusion. Next, if inclusion criteria were met, we retrieved and reviewed the full-text article, discussing any disagreements about inclusion until consensus was reached. We identified 25 publications eligible for full-article review. In the final round of review, 6 articles met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, comprising our final sample. Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the literature search.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection and abstraction process for the current scoping review.

Step 4: Charting the Data

We developed a data abstraction form specifically for this review, including the author name(s), publication date, country, content, study populations, delivery, intervention duration, outcome measures, and main findings. Based on the guideline of the scoping review, we did not evaluate the quality of each study based on methodological rigor.12,13

Step 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

We used narrative synthesis to formulate answers to our research questions.16 Using an iterative process, narrative synthesis facilitates an analysis of relationships within and between studies, enabling us to attain our goal of providing an overview of the literature.17 We summarized findings pertaining to each of our research questions.

Results

Our sample consisted of 6 publications representing 4 unique decision aid interventions (Table 1). Two interventions were conducted in the United States, 1 in Japan, and 1 in Brazil. One of these interventions was presented by authors in 3 publications. We used the term publication when referring to the information found in a specific article and used the term study when referring to information consistent across all articles from a single study.

Table 1.

Description of the 6 Eligible Articles

| Article | Intervention Design | Country | Content | Targeted Populations | Delivery | Intervention Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derech and Neves (2020)18 | Feasibility | Brazil | Information | Caregivers of older adults with severe dementia; aged ≥18 y; could read and write | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Ersek et al(2014)19 | RCT | USA | Information | Nursing home residents with advanced dementia and their surrogates | Audiovisual version Print version | 3 mo |

| Hanson et al (2011)11 | RCT | USA | Information | Nursing home residents with advanced dementia and their surrogates | Audiovisual version Print version | 3 mo |

| Kuraoka and Nakayama (2014)20 | Pre-posttest study (No control group) | Japan | Information | Families of cognitively impaired inpatients aged ≥65 y who were considered for placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube | Print version Review with researchers or physicians | After reviewing the decision aid |

| Mitchell et al (2001)21 | Pre-posttest study | USA | Information | Families of cognitively impaired inpatients aged ≥65 y who were considered for placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube | Audiovisual version Print version | After reviewing the decision aid |

| Snyder et al (2013)22 | RCT | USA | Information | Nursing home residents with advanced dementia and their surrogates | Audiovisual version Print version | 3 mo |

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Study designs in these articles included feasibility (n = 1), pre-posttest (n = 2), and randomized controlled trial (n = 3). All studies focused on caregivers of individuals with advanced dementia. Study settings included nursing homes (n = 3) and acute care hospitals (n = 2).

Research Question 1: Theoretical Underpinnings of This Body of Literature

Only 2 studies used theory to develop or/and evaluate an intervention. The Ottawa Decision Support Framework is characterized by 3 basic steps: (1) identify the needs of the caregivers; (2) address these needs by providing decision support; and (3) evaluate the effect on decision-making.23 This framework seemed to particularly lend itself to the development and evaluation of the decision aid. For example, this framework was used by Mitchell et al21 to guide the development and evaluation of their decision aid. Decisional conflict is a state of uncertainty about the course of action to take.24 Decision conflict, along with knowledge and expectation, is an important indicator of the decision-making quality in the Ottawa Decision Support Framework.23 Outcome selections were also consistent with this framework in the other 2 studies, even though the framework was not mentioned. In addition, Hanson et al reported the use of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Framework25 to ensure the quality of a culturally adapted decision aid as the content was updated with a review of the relevant medical literature.11,22,26

Research Question 2: Content and Format of Decision Aid Interventions

In the following section, we provide a detailed summary of the development of interventions, their targeted outcomes, their content, and their delivery mode(s). After examining these design elements, we found that (1) researchers were active in culturally adapting existing decision aid interventions for different cultures and new settings, and (2) intervention content was similar across studies.

Development process and intervention design

The development process for decision aid interventions appears to be highly iterative, as one or more pilot phases of these interventions or multiple rounds of consultation and revision were reported in all articles. In the Mitchell et al study,21 authors consulted caregivers and other relevant stakeholders and incorporated their comments to design and revise the content of their decision aid.

Researchers in 3 studies culturally adapted an existing decision aid (n = 3). Investigators in 2 of these studies culturally adapted the existing decision aid developed by Mitchell et al.11,20,22 The Brazilian version of the decision aid was adapted from Hanson’s decision aid: Making Choices: Feeding Options for Patients with Dementia.18 Given that more than 30% of participants in the treatment group were African Americans, the text of the existing decision aid was revised to a sixth-grade reading level.11,22,26 In the development process of the decision aid in Japanese and Portuguese, in addition to language translation and updating the existing evidence with those from their population, the authors also consulted local physicians and incorporated their feedback to culturally adapt the existing decision aid.18,20 In 4 studies, physicians were consulted and contributed to the development and revision of the decision aid. In 3 studies, caregivers were involved in the development.11,18,21,22 Health literacy experts and other experts also contributed to the cultural adaptation of the decision aid.11,18,22

Targeted outcomes

In 5 articles, the purpose of the intervention was to improve the quality of caregivers’ decision-making about feeding options (eg, increasing caregiver knowledge, lowering decisional conflict, and setting expectations of benefit from tube feeding). In 3 articles, authors also aimed to investigate the effect of interventions on caregivers’ preference toward tube feeding,20–22 whereas 1 article focused on the actual use of tube feeding.11 One article aimed to improve caregivers’ decision-making quality and their communication with health providers (Table 2).11 One article investigated the association between nurse practitioner and physician assistant (NP/PA) staffing in nursing homes and the impact of decision aid interventions on the frequency of caregiver-provider communication and caregivers’ decisional conflict in nursing homes.19 Table 2 presents the studies’ target outcomes, outcome measures, and main findings.

Table 2.

Target Outcomes, Outcome Measures, and Main Findings Among the 6 Eligible Articles

| Study | Outcome(s)/Outcome Measure(s) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Derech and Neves (2020)18 | N/A | N/A |

| Ersek et al (2014)19 | Frequency of surrogate-provider discussions, decisional conflict | Decisional conflict of surrogates ↓ Frequency of surrogate-provider discussion in facilities that had lower NP/PA staffing level ↑ |

| Hanson et al (2011)11 | Decisional conflict, surrogate knowledge, frequency of communication with providers, and feeding treatment use | Decisional conflict: Intervention group < control group Knowledge, frequency of communication with providers: Intervention group > control group Tube feeding was rare in both groups |

| Kuraoka and Nakayama (2014)20 | Knowledge, decisional conflict, and predisposition regarding feeding tube placement, acceptability of the decision aid | Knowledge ↑, decisional conflict ↓ Of those who were unsure at baseline (n = 4), 2 were slightly in favor and 2 remained unsure after working through the aid. Of those who were slightly against at baseline (n = 3), 2 changed to slightly in favor and 1 changed to clearly against. Most substitute decision makers found the decision aid was helpful and clear, 8 found that it was appropriate in length but 4 found it was a little too long. |

| Mitchell et al (2001)21 | Knowledge, decisional conflict, predisposition regarding feeding tube placement, and the acceptability of the decision aid | Knowledge ↑, decisional conflict ↓ Among 7 participants who were unsure at baseline, 4 chose supportive care only, 1 chose tube feeding, and 2 remained unsure. All participants stated that the aid was helpful and would recommend it to others; many of them found it was clear, balanced, and appropriate in length. |

| Snyder et al (2013)22 | Knowledge of feeding options, the expectation of benefits from tube feeding, decisional conflict, feeding options preferences | Knowledge: ↑ Expectation of benefits from tube feeding and decisional conflict: ↓ Surrogates preferred assisted oral feeding initially, they reported ↑ certainty about this choice after |

Intervention content, delivery, and intervention duration

Given that 3 studies were culturally adapted either from the decision aid developed by Mitchell et al or the one culturally adapted from Mitchell et al’s decision aid, the content of these decision aids is similar. The content of the decision aid interventions included information on dementia, principles of surrogate decision making, and the advantages and disadvantages of tube feeding and hand feeding.

Two studies delivered an audiovisual-print decision aid (Hanson’s 3 articles and Mitchell et al’s),19 and 1 study only provided a printed decision aid.20 Three studies provided caregivers with intervention materials to review on their own without additional intervention elements,11,19,21,22 whereas in one study, a researcher or physician assisted caregivers to read the decision aid, answered caregivers’ questions, and discussed the effects of tube feeding on quality of life with caregivers.20

The duration of interventions in 5 articles was 1 day (n = 2)20,21 or 9 months (n = 3).11,19,22 Although caregivers were encouraged to take the printed version of the decision aid home, the intervention that lasted 9 months did not require caregivers to review the decision aid at home with a specific degree of frequency (ie, unstructured).

Research Question 3: Caregivers’ User Experience With Decision Aid Interventions

Only 1 study reported that the decision aid required 20 minutes to review,11,19,22 and this information was not reported in the other 3 studies.18,20,21 Only 2 articles reported information regarding caregivers’ user experience (ie, their attitudes and opinions about using the decision aid).20,21 The user experience information was collected in the postquestionnaire. The specific questions regarding the user experience were whether caregivers found the decision aid was appropriate in length, clear, balanced, and helpful and whether they would recommend it to others.

Research Question 4: Effect of Decision Aid Interventions on Caregivers’ Decision Making About Feeding Options

Decision-making processes and outcomes were investigated and reported in 5 articles. Knowledge of tube feeding (n = 4) and decisional conflict (n = 5) were the most frequently investigated outcomes. Other commonly explored outcomes included preferences about tube feeding (n = 3), communication between caregivers and health providers (n = 2), and actual use of tube feeding (n = 1).

All 3 intervention studies reported significant postintervention increases in knowledge regarding tube feeding and reduction in decisional conflict.11,20–22 In addition, Hanson et al11 reported that their decision aid intervention increased the frequency of caregivers’ communication about feeding options with providers. Ersek et al19 further found that the decision aid significantly increased discussion rates in facilities with part-time or no NP/PA staffing and that sites with full-time NP/PA staffing had high baseline rates of discussion.

Data on the effects of decision aids on caregivers’ preferences about tube feeding and actual use of tube feeding are limited. Mitchel et al reported that the effectiveness of decision aids on caregivers’ predisposition to tube feeding was only found in those who were unsure of their decision at baseline.21 Kuraoka and Nakayama20 found that among the 13 participants, the number of caregivers who were in favor or slightly in favor of tube feeding increased from 2 to 6 after using the decision aid in Japan, the number of caregivers who were clearly against or slightly against tube feeding decreased from 7 to 5, and the number of caregivers who were unsure reduced from 4 to 2.20 Snyder et al22 reported that caregivers who preferred hand feeding at baseline reported more certainty about their choice after the decision aid. Hanson reported that dementia patients in the intervention group were more likely to receive a dysphagia diet and demonstrated a trend toward greater staff eating assistance than those who received usual care.11 Tube feeding was rare after 9 months’ intervention and was not significantly different between these 2 groups.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to synthesize studies on decision aid interventions for dementia caregivers on decision making about feeding options. The small number of interventions in our review indicates that this area is understudied. In total, 6 publications represent 4 unique decision aid interventions. Among the 4 interventions, 3 were culturally adapted from an existing intervention. The Ottawa Decision Support Framework and the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Framework were used to guide intervention development and evaluation.

The interventions aimed to improve caregivers’ decision making regarding feeding options by providing education. This was accomplished largely through content on dementia and feeding options, the advantages and disadvantages of tube feeding and hand feeding, and the skills of the surrogate decision maker. Most studies used a pre-posttest design with a short duration of intervention. Posttest questionnaires were used to collect information on caregivers’ experience of using the decision aid. Overall, most caregivers found the decision aid helpful and acceptable in difficult and emotional circumstances. A range of decision-making processes and outcomes were investigated, with the knowledge of tube feeding and decisional conflict being the most common. Increase in knowledge of tube feeding and reduction of decisional conflict were commonly reported. However, the effects of interventions on caregivers’ preference or actual use of tube feeding were limited.

Culturally Adapting an Existing Decision Aid Intervention Is Feasible in Decision Making About Feeding Options

Cultural adaptation of existing decision aid interventions has emerged as an intervention strategy as a result of the scarce resources and the cultural diversity of populations.27 The review results provide evidence of the benefits of culturally adapted decision aid interventions aimed to improve caregivers’ decision making regarding feeding options. Indeed, the culturally adapted interventions achieved statistically significant improvements in knowledge of tube feeding, frequency of discussions between caregivers and providers, and reduction in decisional conflict.11,20,22 Of note, one study suggested that the culturally adapted decision aid intervention significantly increased some assisted oral feeding techniques, such as dysphagia diet and specialized staff assistance for feeding.11 The results of this review provide preliminary support for the feasibility and potential benefits of culturally adapting existing decision aid interventions for caregivers in feeding-related decision making. However, there is a need to increase the quality of culturally adapted decision aid interventions.

Although guidelines for cultural adaptation of evidence-based behavioral interventions have been developed,28 few interventions used a systematic approach to cultural adaptation. First, limited information was provided on the methodological approaches used to inform the cultural adaptation. Second, the most common strategy identified in this review was surface-structure strategies, such as revising the decision-aid tools to a lower reading level and replacing the evidence with data from another population. However, deep-structure strategies that address cultural values, mistrust, and communication patterns were not used in most of the reviewed literature. Previous studies have shown that surface-structure adaptations may increase the acceptability of an intervention but may be insufficient to change participants’ behaviors.29,30 Of the 3 intervention studies, one conducted in Japan reported the greatest increase in the number of participants who preferred tube feeding.20 Without a theoretical framework that links specific cultural adaptations to specific anticipated outcomes, it is difficult to explain this result.

Delivering Information Alone Is Not Enough

The existing decision aids typically included information about advanced dementia, feeding options, and their advantages and disadvantages and the role of the surrogate decision maker. Such rich information presented in a static print or audio/video format can be overwhelming for most caregivers, and the standardized content cannot address each caregiver’s needs. In our review, most interventions could increase caregivers’ knowledge of tube feeding and reduce their decisional conflict. Still, they could not mitigate caregivers’ preference over tube feeding or patients’ actual use of tube feeding. Given the complexity of the decision making regarding tube feeding, the decision aid might be the first important step to improve the quality of decision making about feeding options. Individualized consultation is needed to ensure that the decisions are consistent with personal values and goals of care. In addition, some scholars also emphasized the need for the use of more advanced technology for decision aid interventions, such as websites or mobile apps that enable the delivery of tailored information to suit the varying needs of dementia caregivers.31

Recent literature emphasizes the need for the usage of motivational interviewing, a person-centered counseling approach that involves helping individuals to explore and resolve ambivalence about behavior change regarding end-of-life medical treatment.32 Emerging research also demonstrates that an advanced dementia consultation service with a standardized goals of care decision aid is more effective in reducing the rates of rehospitalization and feeding tube insertion than the standardized decision aid intervention alone.33 Therefore, in addition to delivering information through decision aid, future interventions aim to decrease the use of tube feeding, needs to add tailored components, such as motivational interviewing.

Limitations

We did not exhaustively search every electronic database and may have missed some relevant studies. In addition, studies in languages other than English may have contributed to this review. Last, in this scoping review, we only included studies that undertook empirical research employing qualitative or quantitative methods. We may exclude some studies that have been developed without empirical findings. For example, a newly developed decision aid in England that focused on multiple decisions including feeding options was not included in this scoping review.34 In fact, family caregivers of individuals with advanced dementia have to face multiple decisions, and the decision-making about feeding options is often inter-related with other areas of end-of-life decision making. Future studies need to compare the effect of the decision aid focusing on a single decision with those focusing on multiple decisions in improving the quality of decision making.

Conclusions and Implications

We have described the development and evaluation of decision aid interventions for caregivers of persons with advanced dementia. All the interventions aimed to improve caregivers’ decision making about feeding options. Most of the interventions are culturally adapted from an existing decision aid intervention; however, none of them used a theoretical framework to guide cultural adaptation. The interventions provided only static support in the printed or audio format. Caregivers reported that the interventions were acceptable. Knowledge in tube feeding and decisional conflict were frequently investigated. Although there were significant improvements in the knowledge of tube feeding, decisional conflict, and discussions between caregivers and providers, there was no significant change in caregivers’ preference toward tube feeding or patients’ actual use of tube feeding. Our review underscores the importance of adding individualized components to decrease the use of tube feeding in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant P50MD017356).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mitchell SL. Advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2533–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillick MR. Rethinking the role of tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Mitchell SL, et al. Does feeding tube insertion and its timing improve survival? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1918–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YF, Hsu TW, Liang CS, et al. The efficacy and safety of tube feeding in advanced dementia patients: a systemic review and meta-analysis study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee and Clinical Practice and Models of Care Committee. American Geriatrics Society feeding tubes in advanced dementia position statement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1590–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies N, Barrado-Martin Y, Vickerstaff V, et al. Enteral tube feeding for people with severe dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;8:CD013503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Kuo SK, et al. Decision-making and outcomes of feeding tube insertion: a five-state study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:881–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes-Rovner M International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS): beyond decision aids to usual design of patient education materials. Health Expect. 2007;10:103–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanson LC, Carey TS, Caprio AJ, et al. Improving decision-making for feeding options in advanced dementia: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2009–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5:371–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169: 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan KS, Ter Riet G, Glanville J, Sowden AJ, Kleijnen J. Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: CRD’s Guidance for Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008;6:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derech RDA, Neves FS. Cross-cultural adaptation and content validity of the patient decision aid “Making Choices: Feeding Options for Patients with Dementia” to Brazilian Portuguese language. Article in Portuguese, English. Codas. 2021;33:e20200044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ersek M, Sefcik JS, Lin FC, Lee TJ, Gilliam R, Hanson LC. Provider staffing effect on a decision aid intervention. Clin Nurs Res. 2014;23:36–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuraoka Y, Nakayama K. A decision aid regarding long-term tube feeding targeting substitute decision makers for cognitively impaired older persons in Japan: a small-scale before-and-after study. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell S, Tetroe J, O’Connor A. A decision aid for long-term tube feeding in cognitively impaired older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snyder EA, Caprio AJ, Wessell K, Lin FC, Hanson LC. Impact of a decision aid on surrogate decision-makers’ perceptions of feeding options for patients with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:114–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, et al. A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995; 15:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson LC, Gilliam R, Lee TJ. Successful clinical trial research in nursing homes: the improving decision-making study. Clin Trials. 2010;7:735–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chenel V, Mortenson WB, Guay M, Jutai JW, Auger C. Cultural adaptation and validation of patient decision aids: a scoping review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez MMD, Baumann AA, Schwartz AL. Cultural adaptation of an evidence based intervention: From theory to practice in a Latino/a community context. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;47:170–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews AK, Steffen AD, Kuhns LM, et al. Evaluation of a randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of a culturally targeted and nontargeted smoking cessation intervention for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21:1506–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagisetty PA, Priyadarshini S, Terrell S, et al. Culturally targeted strategies for diabetes prevention in minority population: a systematic review and framework. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43:54–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie B, Berkley AS, Kwak J, Fleischmann KR, Champion JD, Koltai KS. End-of-life decision making by family caregivers of persons with advanced dementia: a literature review of decision aids. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312118777517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fried TR, Leung SL, Blakley LA, Martino S. Development and pilot testing of a motivational interview for engagement in advance care planning. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:897–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catic AG, Berg AI, Moran JA, et al. Preliminary data from an advanced dementia consult service: integrating research, education, and clinical expertise. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2008–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies N, Sampson EL, West E, et al. A decision aid to support family carers of people living with dementia towards the end-of-life: coproduction process, outcome and reflections. Health Expect. 2021;24:1677–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.