Abstract

Both pseudomyxoma peritonei and Morgagni hernias in adults are rare clinical conditions. A 70-year-old woman who was diagnosed with pseudomyxoma peritonei with Morgagni hernia underwent cytoreductive surgery and primary repair. Pseudomyxoma peritonei causes increased intra-abdominal pressure that may lead to acquired congenital diaphragmatic hernia when there is a local fragility in the diaphragmatic musculature. Parietal peritonectomy of the right diaphragmatic peritoneum can safely remove the hernia sac. The high rate of infections associated with cytoreductive surgery causes hesitation for concurrent mesh repair for Morgagni hernia. This is the first report of pseudomyxoma peritonei with Morgagni hernia. Cytoreductive surgery including parietal peritonectomy of the right diaphragmatic peritoneum plus primary repair of hernial defect was performed safely and successfully, which achieved positive short-term results for patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei-associated Morgagni hernia.

Keywords: Pseudomyxoma peritonei, Morgagni hernia, Cytoreductive surgery, Peritonectomy

Introduction

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare peritoneal malignancy characterized by diffuse progressive mucinous ascites and mucin-producing tumor cells distributed throughout the abdomen and pelvis [1]. Progression of PMP leads to abdominal distention, intestinal obstruction, intestinal fistula, urinary disorder, cachexia and ultimately death.

Acquired congenital diaphragmatic hernia has been defined as late-onset congenital diaphragmatic hernia [2]. Increased intra-abdominal pressure caused by circumstances such as obesity, pregnancy, and chronic cough, are well known cause of acquired congenital diaphragmatic hernia when there is a local fragility in the diaphragmatic musculature. To date, Morgagni hernia is a rare clinical entity occurring in adults without a well-described characterization of prevalence or natural history [3], and to the best our knowledge, there has been no English literature published on PMP associated Morgagni hernia.

Here, we present an adult case of PMP with asymptomatic Morgagni hernia that required cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and primary repair of the hernial defect.

Case report

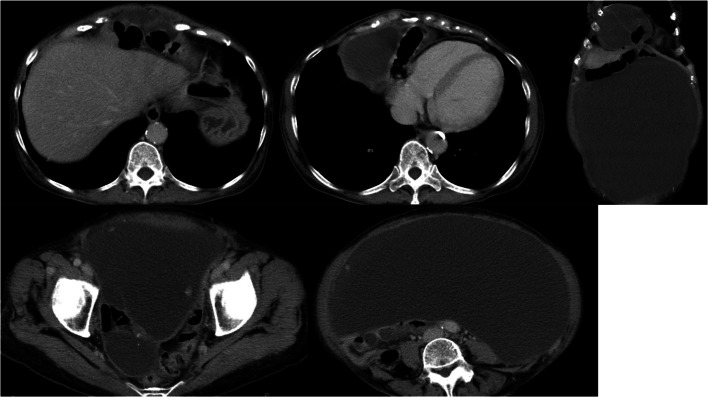

A 70-year-old woman was referred from primary care doctor for anorexia, increasing abdominal girth and leg edema. The patient’s surgical history included total abdominal hysterectomy and left oophorectomy. Computed tomography (CT) revealed cystic lesions that were presumed to be encapsulated ascites within the abdominal cavity and pelvis, and the cystic lesion and transverse colon were prolapsed into right thoracic cavity (Fig. 1). In the right pelvis, a cystic mass of 60 mm in diameter was found. The patient was referred to the Center of Peritoneal Dissemination for further treatment.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative CT findings. A cystic lesion presumed to be encapsulated ascites spreads from the abdominal cavity to the pelvis. A section of the transverse colon and ascites were prolapsed into right thoracic cavity behind the sternum. In the right pelvis, the cystic mass of 60 mm in diameter was found

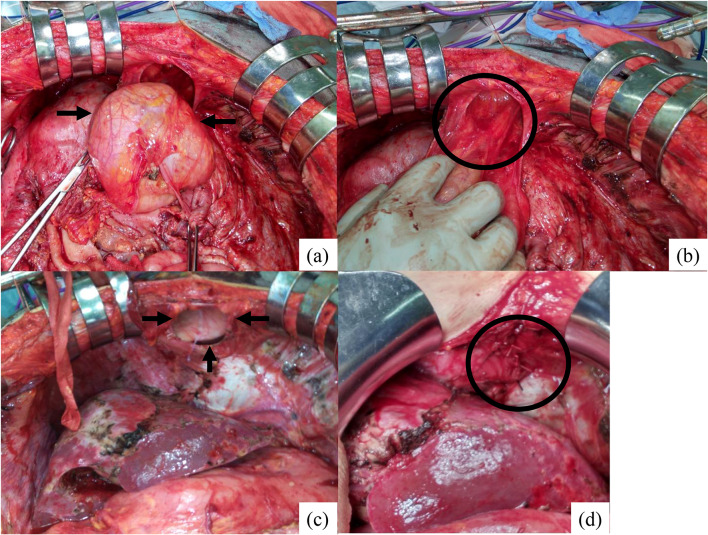

The preoperative diagnosis at our department was PMP with diaphragmatic hernia. Laparotomy was performed under general and epidural anesthesia. There was 6000 ml of encapsulated mucinous ascites. A mucin-producing tumor was found at the tip of the appendix, which was lumped with the right ovary. The peritoneal cancer index score was 12. CRS was performed by stripping all parietal peritoneum and visceral resection of appendix, right ovary, rectum, spleen, gall bladder and greater omentum and achieved complete cytoreduction (no residual visible disease). The diaphragmatic hernial orifice was found in the anterior diaphragm, which was diagnosed as Morgagni hernia. During the parietal peritonectomy of right diaphragmatic peritoneum, the hernia component was easily drawn back (Fig. 2a, b), and the hernia sac was removed safely. The hernial orifice was measured about 40 mm in diameter (Fig. 2c). Because of the concern of postoperative mesh infection, diaphragmatic hernia repair was performed via primary suture of the hernial defect using 0 absorbable suture (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative findings, a Hernia contents (black arrow), b Hernia sac (black circle), c Hernial defect (black arrow), d Primary repair by 0 absorbable suture (black circle)

Pathological examination was done on surgical specimens (Fig. 3). Pathologically, the appendix tumor was diagnosed with low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) (Fig. 4a). Only few tumor cells with low-grade atypia were found in the right ovary (Fig. 4b), which led to diagnosis of the appendix as the primary lesion. The ascites cytology revealed mucin without tumor cells. No tumor cells were found on surface of peritoneum. Finally, the patient diagnosis was LAMN and low-grade PMP.

Fig. 3.

Surgical specimen, a Appendix and right ovary with parietal peritoneum of right lower abdomen, b Right diaphragmatic peritoneum with hernia sac. A large amount of mucus adhered to the parietal peritoneum

Fig. 4.

Pathological findings hematoxylin and eosin staining (× 100 magnification) of the appendix, a and the right ovary (b). a Low-grade mucinous neoplasm. b Few tumor cells with poor atypia (black arrow) and abundant mucin

The patient started oral diet after seven days of surgery. Postoperative complications included urinary tract and central venous catheter infection 18 days after surgery (the Clavien–Dindo classification grade II). Antibiotic treatment was given for 14 days due to positive blood bacterial cultures. The appetite of the patient was gradually restored after completing the antibiotic treatment. The patient was discharged 40 days after surgery.

The patient did not receive postoperative treatment. On CT, there was no recurrence of pseudomyxoma peritonei and a Morgagni hernia 2 months after surgery (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Postoperative CT findings 2 months after surgery There were no signs of hernia recurrence between sternum and liver surface. The space after hernia sac resection was reduced compared to CT findings 14 days after surgery

Discussion

PMP is a rare peritoneal malignancy typically originating from a perforated mucinous tumor of the appendix [4]. In 2010, the WHO proposed the classification of appendiceal mucinous tumors and PMP based on the presence of mucin, and the cytological and architectural features [5]. According to the WHO classification, appendiceal mucinous tumors are defined as LAMN or mucinous adenocarcinoma, and PMP is divided into low and high grades [5]. Low-grade PMP is characterized by mucin pools with low cellularity, unremarkable cytology and non-stratified cuboidal epithelium [6].

Typical clinical symptoms of PMP include appendicitis, increased abdominal girth, ovarian mass, and inguinal hernia [7]. In the previous report, the incidence of PMP patients developing a new onset inguinal hernia was reported to range from 7.3% to 9.6% [1]. Although a case of diaphragmatic hernia following CRS for PMP has been reported [8], PMP causing diaphragmatic hernia is an extremely rare entity and this is first case report of PMP with Morgagni hernia. In PMP patient, the reason for the occurrence of Morgagni hernia is less common than inguinal or umbilical hernia is unclear. Diaphragmatic hernias are less prevalent than inguinal or umbilical hernias. This might be because the abdominal wall fragility is more likely to occur in inguinal or umbilical than in diaphragm. Similarly, we hypothesize that when PMP increases intra-abdominal pressure, it is more likely to develop inguinal or umbilical hernia rather than diaphragmatic hernia.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias are classified as esophageal hiatal, Bochdalek, and Morgagni hernias according to the site of the defect of diaphragm [9]. A Morgagni hernia is caused by defect found in the anterior aspect of the diaphragm between the costal and sternal portions of the muscle. In this case, the hernial orifice was found intraoperatively at the anterior, parasternal portion of the right diaphragm. The patient did not reveal any abnormalities during the previous medical check. Apart from increased intra-abdominal pressure due to PMP, there were no predisposing conditions for Morgagni hernia including trauma, obesity, chronic constipation, or chronic cough. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed as Morgagni hernia, presumably caused by increased intra-abdominal pressure by PMP.

For peritoneal surface malignancy, CRS has been accepted globally. CRS including parietal peritonectomy and required multi visceral resection [10, 11] can achieve long-term survival in patients with PMP. For appendiceal PMP, complete cytoreduction (CC) include CC-0 (no residual visible disease) or CC-1 (remaining nodules < 2.5 mm) [4], which can be expected with good disease-free survival and overall survival [6, 12]. In 2018, we reported in Japanese journal that the 5-year survival was 83% for cases with complete cytoreduction in our experience of more than 500 cases. The main determinants of the outcome are reported histological type and complete cytoreduction [4], not including hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) as there are no prospective studies to reveal the efficacy of HIPEC. In addition, HIPEC is not covered by Japanese medical insurance. Based on these regional considerations, our current strategy for PMP is CRS without HIPEC, which was indicated for the current patient.

Regarding postoperative treatment, there has been no evidence about usefulness of adjuvant chemotherapy for PMP where the primary lesion is LAMN; hence, we did not perform postoperative treatment in such cases.

In a previous report, 28% of the Morgagni hernia patients were asymptomatic [3]. Surgical repair is recommended for both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases to prevent complication such as incarceration, obstruction, and strangulation [9]. Longstanding principles underlying successful hernia repair are applicable to the repair of Morgagni hernia, which include complete reduction of hernia contents, resection of the hernia sac, and repair of the defect with mesh reinforcement as necessary [13]. The trans-abdominal approach can safely reduce hernia contents and repair intraabdominal pathology with a clear view of the surgery. Management of the hernia sac is a key decision factor [4]. Some authors feel the hernia sac should not be resected because of the risk of injuring thoracic structure, whereas an unexcised hernia sac can cause postoperative seroma, infection, and recurrence [13]. During repair of hernia defects, primary repair is performed mostly during traditional open surgery, while the spread of laparoscopic surgeries has increased mesh repair [14]. The use of prosthetic mesh is recommended to cover defects larger than 20–30 cm [2], and suturing large defects provided a flat surface for preventing mesh extrusion through defect may lead to reduce recurrence rate [15].

To date, there has been no conclusion of the superiority of each procedure [3]. In this case, we selected laparotomy to provide concurrent definitive CRS for PMP. There were fortunately few adhesions between hernia sac and thoracic structure, therefore the hernia sac was easily removed using a parietal peritonectomy of the right diaphragmatic peritoneum. For Morgagni hernia repair, we performed a primary repair due to concerns regarding postoperative surgical site infection that may cause mesh infection. Zhou et al. reported that infectious complication rate after CRS in their institution was anastomotic leakage (7.0%), abdominal abscess (10.5%), and wound infection (9.3%) [16]. In a systematic review, the rate of grade III/IV morbidity of CRS and HIPEC ranged from 12 to 52% even in high volume centers [17]. Based on this background of complications, we suggest that prosthetic mesh repair should not be performed simultaneously with CRS. According to our knowledge, the peritonectomy of right diaphragmatic peritoneum causes severe adhesion between liver and right diaphragm, resulting in the liver coverage of the repair site. After CRS, we believe primary repair and liver coverage can prevent Morgagni hernia recurrence.

In summary, PMP can cause acquired congenital diaphragmatic hernia. CRS including parietal peritonectomy of the right diaphragmatic peritoneum plus primary repair was performed safely and successfully achieved a positive short-term result for PMP with Morgagni hernia. A longer observation period is required to evaluate the ultimate result of this procedure.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (2022-0090).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained for the publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sugarbaker PH. Management of an inguinal hernia in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(6):1083–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiseman NE, MacPherson RI. “Acquired” congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1977;12(5):657–665. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(77)90389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton JD, Hofmann LJ, Hetz SP. Presentation and management of Morgagni hernias in adults: a review of 298 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(6):1413–1420. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9754-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Govaerts K, Lurvink RJ, De Hingh IHJT, et al. Appendiceal tumours and pseudomyxoma peritonei: Literature review with PSOGI/EURACAN clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(1):11–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe H, Miyasaka Y, Watanabe K, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei due to low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm with symptoms of inguinal hernia and uterine prolapse: a case report and review of the literature. Int Cancer Conf J. 2017;6(4):158–163. doi: 10.1007/s13691-017-0297-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ning S, Yang Y, Wang C, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei induced by low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm accompanied by rectal cancer: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2019;19(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0508-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esquivel J, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical presentation of the Pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Br J Surg. 2000;87(10):1414–1418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lampl B, Leebmann H, Mayr M, et al. Rare diaphragmatic complications following cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2014;44(2):383–386. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furukawa H, Wakasugi M, Yoshikawa Y, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic repair for a Morgagni hernia: a case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2021;14(1):124–127. doi: 10.1111/ases.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugarbaker PH. Parietal peritonectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(4):1250. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Ann Surg. 1995;221(1):29–42. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199501000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with Pseudomyxoma peritonei From appendiceal origin treated By a strategy of Cytoreductive surgery and Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2449–2456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeflang E, Madden J, Ibele A, et al. Laparoscopic management of symptomatic diaphragmatic hernia of Morgagni in adult. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(1):216–221. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-08259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsaros I, Katelani S, Giannopoulos S, et al. management of morgagni’s hernia in the adult population: a systemic review of the literature. World J Surg. 2021;45(10):3065–3072. doi: 10.1007/s00268-021-06203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gielis M, Bruera N, Pinsak A, et al. Laparoscopic repair of acute traumatic diaphragmatic hernia with mesh reinforcement: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;93:106910. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.106910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou S, Feng Q, Zhang J, et al. High-grade postoperative complications affect survival outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer peritoneal metastases treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07756-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chua TC, Yan TD, Saxena A, et al. Should the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy still be regarded as a highly morbid procedure? Ann Surg. 2009;249(6):900–907. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a45d86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.