Abstract

Gastric neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) are highly aggressive cancer with dismal prognosis. Platinum-based chemotherapy is used as the first-line treatment for this entity. However, there are no established therapeutic guidelines for platinum-resistant gastric NEC. We herein report a patient with metastatic gastric NEC who achieved durable and complete response to nivolumab with radiotherapy for oligoprogressive metastasis. A 70-year-old male patient had recurrences of resected gastric NEC, involving the liver and lymph nodes. His disease became refractory to cisplatin and etoposide combination therapy, after which he was treated with nivolumab. All the tumors showed marked shrinkage. However, 1 year after starting nivolumab, one metastatic lesion of the liver began to enlarge, and radiotherapy was performed to the lesion. Thereafter, a complete response was obtained, which has been maintained without any treatment for the past 2 years.

Keywords: Gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma, Nivolumab, Oligometastasis, Radiotherapy

Introduction

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) is a rare cancer with an estimated incidence of 4.6/1,000,000 in 2012 [1]. It most commonly has colorectal, followed by upper gastrointestinal and pancreatic origins. Gastroenteropancreatic NEC is highly aggressive with poor prognosis, with a median overall survival of 38 months for localized disease and 5 months for metastatic disease [2]. Traditionally, extra-pulmonary NEC is considered similar to small-cell lung cancer, and platinum-containing doublet regimens have been recommended for advanced gastroenteropancreatic NEC [3–5]. The median overall survival was reported to be 13.3 months in patients with advanced gastric NEC treated with systemic chemotherapy [6]. Recently, a randomized phase III trial in which etoposide plus cisplatin versus irinotecan plus cisplatin was administered for advanced gastroenteropancreatic NEC demonstrated that both regimens remain the standard first-line treatment options [7]. Although there is no standard second-line treatment after failure of platinum-based treatment, fluoropyrimidine in combination with either irinotecan, oxaliplatin, or temozolomide, is weakly recommended without prospective or randomized trials [8].

Recently, nivolumab, a monoclonal antibody against programmed death-1 (PD-1) receptor, which is one of the ICIs, showed moderate activity for small cell lung carcinoma refractory to chemotherapy. The drug showed a response rate of 11.6%, and 2 year survival rate of 17.9% in phase 1/2 trial for nivolumab monotherapy [9]. Moreover, it has been reported that in a small population of some cancers such as non-small cell lung cancer, hepatocellular cancer, and urothelial cancer, progression of a few metastatic lesions occurred during treatment with tyrosine-kinase inhibitors or ICIs, while most other lesions remained well controlled [10]. This progression of a limited number of metastatic lesions has been termed as oligoprogression, but the term has not been universally defined. In this case, it has been shown that adding local treatment to oligoprogressive lesions may have a clinical benefit in some patients. Although ICIs are also used for gastric NEC, not much is known about their efficacy and benefits in additional local treatments.

Here, we present a rare case of gastric NEC in which use of nivolumab and additional radiotherapy to oligoprogressive metastasis provided a durable and complete response.

Case report

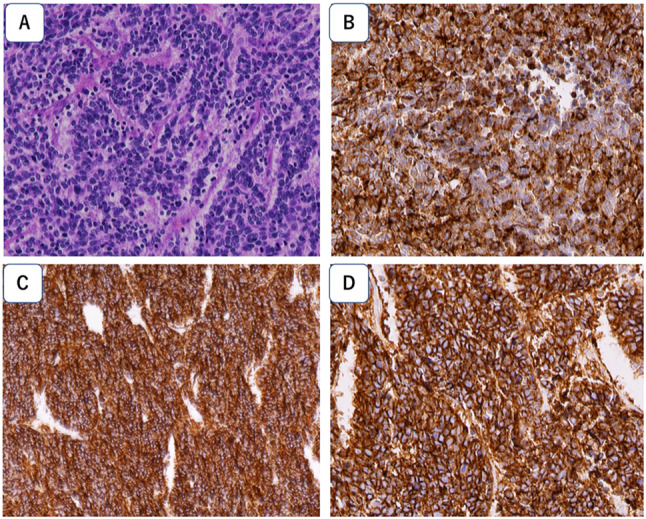

A 70-year-old male patient with history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) visited a medical clinic complaining of tarry stool. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a type 2 tumor in distal stomach, and histological diagnosis of endoscopic biopsy was small cell type NEC. Distal gastrectomy was performed at the referred hospital since no distant metastasis was observed with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan. Post-operative diagnosis was small cell carcinoma with positive immunohistochemical expression of chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56 (Fig. 1). Pathological staging was stage IIB (T3N1M0), in accordance with the 8th edition of UICC/TNM classification. During adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 (tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil), recurrences were observed in the liver and lymph nodes. He subsequently received paclitaxel plus ramucirumab, but the disease progressed. Then, he was referred to our hospital for further treatment.

Fig. 1.

Pathological examination of surgical specimens. A Hematoxylin and Eosin stained section showing small atypical cells with high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, proliferating densely in cord-like or ribbon-like arrangement. Tumor cells show diffuse positivity for B chromogranin A, C synaptophysin, and D CD56 immunostaining. Magnification, × 400

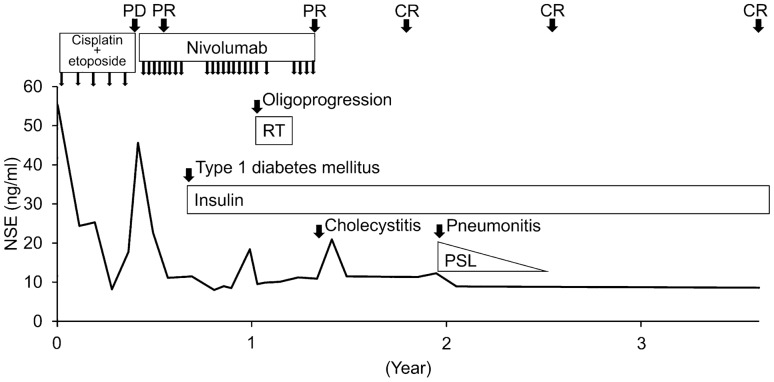

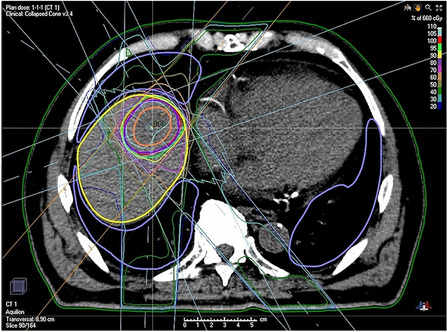

We started his treatment with cisplatin (80 mg/m2, day 1) plus etoposide (100 mg/m2, days 1, 2, and 3) every 3 weeks, after which shrinking of tumors was observed along with a decrease in serum neuron specific enolase (NSE) level (Fig. 2). However, after five courses of treatment, all metastatic lesions enlarged, and a lymph node metastasis invaded the remnant stomach (Figs. 3A, 4A). His treatment was then changed to nivolumab (240 mg/body on day 1, every 2 weeks). The European Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 0, and the patient had no subjective symptoms. Serum NSE, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and HbA1c levels were 45 ng/ml, 3.4, and 6.6%, respectively (Table 1). CT scan after 4 courses of nivolumab showed partial response with remarkable tumor shrinkage (Fig. 4B), and serum levels of NSE returned to the normal range (Fig. 2). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy after 8 courses of nivolumab showed disappearance of lymph node metastasis invading the stomach (Fig. 3B). Three months from the start of nivolumab therapy, the patient complained of thirst and polyuria during the regular visit, and his blood investigation showed abnormal sugar metabolism findings. Serum values of glucose, glycoalbumin, and HbA1c were 602 mg/dl, 33%, and 7.8%, respectively. Serum C-peptide was 1.97 ng/ml, and urinary C-peptide decreased to 11 μg/day. Serum anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody and urinary ketone body were negative. We stopped nivolumab treatment and started insulin therapy with lispro plus glargine, once the diagnosis of nivolumab-related type 1 DM was made. Nivolumab was restarted after serum blood sugar control was attained in 2 months. 1 year after initial nivolumab treatment, enlargement of one liver metastatic lesion was observed (Fig. 4C). Radiotherapy (66 Gy/10 fractions) was performed for this lesion in combination with nivolumab (Fig. 5), and a complete response was achieved (Fig. 4D). Nivolumab was discontinued 2.5 months after completion of radiotherapy, due to cholecystitis requiring cholecystectomy. Although pneumonitis developed in bilateral lower lung fields 5.5 months after radiotherapy completion, it responded well to corticosteroids. At present, complete response has been maintained for 2 years since nivolumab was discontinued (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient’s clinical course. Durable complete response was achieved using nivolumab and radiotherapy. NSE neuron specific enolase, RT radiotherapy, PSL prednisolone, PD progressive disease, PR partial response, CR complete response

Fig. 3.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy findings. A Direct invasion of lymph node metastases to the stomach remnant was observed before administration of nivolumab. B Invasion of lymph node disappeared 4 months after commencement of nivolumab therapy

Fig. 4.

Computed tomography scan of the liver (yellow and blue arrows) and lymph node (green arrow) metastasis. A Metastatic sites before receiving nivolumab. B Tumor remarkably shrunk after 2 months of nivolumab administration. C Liver metastasis regrowth after 1 year of nivolumab administration (yellow arrow). D Complete response was achieved 6 months after radiotherapy was concomitantly administered with nivolumab therapy

Table 1.

Laboratory data before commencement of nivolumab therapy

| Hematology | |

| White blood cells | 12,800/μl |

| Neutrophils | 68.8% |

| Lymphocytes | 20.1% |

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | 3.42 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.8 (g/dL) |

| Platelets | 18.7 × 104/μl |

| Biochemistry | |

| Albumin | 4.0 (g/dL) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 25 (U/L) |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 23 (U/L) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 287 (U/L) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 280 (U/L) |

| Total bilirubin | 0.4 (mg/dL) |

| Urea nitrogen | 21.3 (mg/dL) |

| Creatinine | 1.08 (mg/dL) |

| C-reactive protein | 3.89 (mg/dL) |

| Amylase | 67 (U/L) |

| Casual blood glucose | 278 (mg/dL) |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 6.6 (%) |

| NSE | 45.6 (ng/mL) |

| Urine analysis | |

| Protein | (−) |

| Glucose | 4+ |

| Ketone | (−) |

NSE neuron specific enolase

Fig. 5.

Dose-distribution of radiotherapy for oligoprogressive liver metastasis

Discussion

The noteworthy findings of the present case were that a patient with platinum-resistant gastric NEC showed good response to nivolumab and a progressed metastatic lesion emerging 1 year after nivolumab therapy was successfully treated with radiotherapy.

Few studies have reported the efficacy of nivolumab in gastric NEC, except a case of metastatic NEC after gastrectomy of mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma, in which the NEC component was limited to 5% at the invasive front [11]. Recently, a phase II clinical trial of ipilimumab plus nivolumab in patients with nonpancreatic neuroendocrine tumors was conducted [12]. Although a high overall response rate of 44% was observed in patients with nonpancreatic NEC, two patients with gastric NEC demonstrated no response. ICIs are expected to have effective therapeutic effects on NEC, however, further studies are required to set guidelines for selection of patients sensitive to ICIs.

Our patient demonstrated good performance status, normal organ functions, and relatively less tumor burden at the end of standard platinum-based chemotherapy. Good overall general condition of the patients’ has been suggested to be essential for successful immunotherapy [13]. Moreover, several biomarkers for the response to PD-1/ programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors have been reported to elicit durable anti-tumor effects in multiple cancers [14–16]. NLR, a marker of systemic inflammation, has been suggested as a predictive or prognostic factor for gastric cancer treated using nivolumab [17, 18]. Low NLR (< 5) has been associated with longer progression-free and overall survival compared to high NLR (≧5) in gastric cancer patients. The present case met this finding (low NLR of 3.42 in the pretreatment phase). NEC demonstrates high PD-L1 expression and high tumor mutation burden [19], which are considered preferable for response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in several malignant tumors [20, 21]. On the other hand, absence of microsatellite instability-high gene status, another favorable biomarker for ICIs, was reported in digestive system NECs [19]. A phase II clinical trial of pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, for metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms showed no difference in disease control rate, progression free survival, and overall survival between PD-L1-negative and -positive groups [22]. Unfortunately, PD-L1 expression, tumor mutation burden, and microsatellite gene status were not tested in our patient, and the contribution of these biomarkers towards patients’ response was unknown.

It has been recognized that a certain proportion of patients treated with ICIs experience oligoprogression during the course of treatment [10]. In our patient, progression of only one liver metastatic lesion was observed, while all other metastases maintained good response. At that timepoint, it was a progressive disease and next treatment plan was devised. However, we used local radiotherapy for the lesion because no effective drug was left for consideration. Fortunately, this lesion was well controlled with radiotherapy, and tumor shrinkage of other lesions were maintained with nivolumab. As reported, local radiation therapy triggers systemic anti-tumor effects by the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, increasing tumor infiltrating immune cells, and modulating neoantigen expression simultaneously [23]; however, the clinical benefit remains controversial [24–26].

Our patient experienced type 1 DM, which was considered a nivolumab-related adverse event. Since neither ketoacidosis nor ketosis was observed in the patient, his DM did not fully match the diagnostic criteria of acute-onset type 1 DM based on the Japanese Diabetes Society guideline [27]. However, this could be attributed to the very initial stage of type 1 DM. In fact, similar nivolumab-related fulminant type 1 DM with lack of diabetic ketoacidosis was reported in a previous study [28]. Type 1 DM is a rare immune-related adverse event (0.1–0.2%) [29], and only one case with previous history of type 2 DM has been reported [30], similar to our case. Further accumulation of clinical data is needed to determine whether type 2 DM is a risk factor for ICI-related type 1 DM. In our patient, pneumonitis developed 5 months after completion of radiation therapy and 3 months after termination of nivolumab. Irradiation field for liver metastasis involved a part of bilateral lung. Radiation pneumonitis commonly develops 3–6 months after completion of radiation, and nivolumab-related pneumonitis is also considered. Although it remained unclear whether either or both of nivolumab and radiation induced pneumonitis, precaution should be taken for the risk of pneumonitis.

To summarize, we reported a rare case of gastric NEC, successfully treated using nivolumab for metastatic entities and radiotherapy for a progressed liver metastasis, which was accompanied with the development of nivolumab-related type 1 DM and pneumonitis. Further studies are needed to assess the efficacy of ICIs in gastric NEC and the management of oligoprogression.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

I.H. serves as a consultant to Asahi Kasei, Ono, Chugai, Taiho, and Eisai pharmaceutical companies. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The authors declare that this study conformed to the Declaration a Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of his disease and clinical course.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Das S, Dasari A. Epidemiology, incidence, and prevalence of neuroendocrine neoplasms: are there global differences? Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23:43. doi: 10.1007/s11912-021-01029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Carbonero R, Sorbye H, Baudin E, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:186–194. doi: 10.1159/000443172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013;42:557–577. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31828e34a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:844–860. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah MH, Goldner WS, Benson AB, et al. Neuroendocrine and adrenal tumors, version 2.2021. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2021;19:839–867. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi T, Machida N, Morizane C, et al. Multicenter retrospective analysis of systemic chemotherapy for advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1176–1181. doi: 10.1111/cas.12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morizane C, Machida N, Honma Y, et al. Effectiveness of etoposide and cisplatin vs irinotecan and cisplatin therapy for patients with advanced neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system: The TOPIC-NEC phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorbye H, Grande E, Pavel M, et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society ( ENETS ) 2023 guidance paper for digestive neuroendocrine carcinoma. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023 doi: 10.1111/jne.13249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ready NE, Ott PA, Hellmann MD, et al. Nivolumab monotherapy and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small cell lung cancer: results from the CheckMate 032 Randomized Cohort. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:426–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sindhu KK, Nehlsen AD, Lehrer EJ, et al. Oligoprogression of solid tumors on immune checkpoint inhibitors: the impact of local ablative radiation therapy. Biomedicines. 2022 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10102481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawayama H, Komohara Y, Hirao H, et al. Nivolumab exerts therapeutic effects against metastatic lesions from early gastric adenocarcinoma with a small proportion of neuroendocrine carcinoma after gastrectomy: a case report. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13:759–765. doi: 10.1007/s12328-020-01159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel SP, Othus M, Chae YK, et al. A phase II basket trial of dual anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1 blockade in rare tumors (DART SWOG 1609) in patients with nonpancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santini D, Zeppola T, Russano M, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors during late stages of life: an ad-hoc analysis from a large multicenter cohort. J Transl Med. 2021;19:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02937-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M, et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aar3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGranahan N, Furness AJS, Rosenthal R, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 2016;351:1463–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogata T, Satake H, Ogata M et al (2018) Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictive or prognostic factor for gastric cancer treated with nivolumab: a multicenter retrospective study. Oncotarget 9:34520–34527. 10.18632/oncotarget.26145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Suzuki H, Yamada T, Sugaya A, et al. Retrospective analysis for the efficacy and safety of nivolumab in advanced gastric cancer patients according to ascites burden. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01810-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xing J, Ying H, Li J, et al. Immune checkpoint markers in neuroendocrine carcinoma of the digestive system. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagos GG, Izar B, Rizvi NA. Beyond tumor PD-L1: emerging genomic biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B. 2020;40:1–11. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_289967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:847–856. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vijayvergia N, Dasari A, Deng M, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms: joint analysis of two prospective, non-randomised trials. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:1309–1314. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0775-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin M, Patin EC, Pedersen M, et al. Inflammatory microenvironment remodelling by tumour cells after radiotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:203–217. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klemen ND, Wang M, Feingold PL, et al. Patterns of failure after immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors predict durable progression-free survival after local therapy for metastatic melanoma. J Immunother cancer. 2019;7:196. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0672-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Y, Li H, Fan Y. Progression patterns, treatment, and prognosis beyond resistance of responders to immunotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.642883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenfeld JD, Giobbie-Hurder A, Ranasinghe S, et al. Durvalumab plus tremelimumab alone or in combination with low-dose or hypofractionated radiotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer refractory to previous PD(L)-1 therapy: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:279–291. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00658-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki E, Maruyama T, Imagawa A, et al. Diagnostic criteria for acute-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus (2012): report of the committee of Japan diabetes society on the research of fulminant and acute-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5:115–118. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto N, Tsurutani Y, Katsuragawa S, et al. A patient with nivolumab-related fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus whose serum C-peptide level was preserved at the initial detection of hyperglycemia. Intern Med. 2019;58:2825–2830. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2780-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baden MY, Imagawa A, Abiru N, et al. Characteristics and clinical course of type 1 diabetes mellitus related to anti-programmed cell death-1 therapy. Diabetol Int. 2019;10:58–66. doi: 10.1007/s13340-018-0362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes J, Vudattu N, Sznol M, et al. Precipitation of autoimmune diabetes with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:e55–e57. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]