Abstract

Engineered T cells represent an emerging therapeutic modality. However, complex engineering strategies can present a challenge for enriching and expanding therapeutic cells at clinical scale. In addition, lack of in vivo cytokine support can lead to poor engraftment of transferred T cells, including regulatory T cells (Treg). Here, we establish a cell-intrinsic selection system that leverages the dependency of primary T cells on IL-2 signaling. FRB-IL2RB and FKBP-IL2RG fusion proteins were identified permitting selective expansion of primary CD4+ T cells in rapamycin supplemented medium. This chemically inducible signaling complex (CISC) was subsequently incorporated into HDR donor templates designed to drive expression of the Treg master regulator FOXP3. Following editing of CD4+ T cells, CISC+ engineered Treg (CISC EngTreg) were selectively expanded using rapamycin and maintained Treg activity. Following transfer into immunodeficient mice treated with rapamycin, CISC EngTreg exhibited sustained engraftment in the absence of IL-2. Furthermore, in vivo CISC engagement increased the therapeutic activity of CISC EngTreg. Finally, an editing strategy targeting the TRAC locus permitted generation and selective enrichment of CISC+ functional CD19-CAR-T cells. Together, CISC provides a robust platform to achieve both in vitro enrichment and in vivo engraftment and activation, features likely beneficial across multiple gene-edited T cell applications.

Keywords: Treg, IL-2, CRISPR, mTOR, CAR-T, CISC

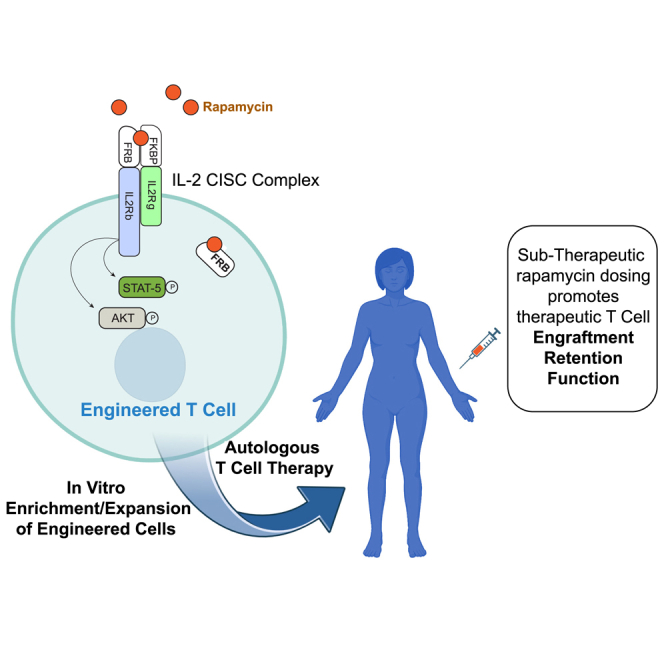

Graphical abstract

To facilitate the development of gene-edited T cell therapies, David Rawlings and colleagues have established a novel fusion cytokine receptor system that activates IL-2 signaling in response to rapamycin. This chemically inducible signaling complex can be incorporated into gene-editing platforms to generate Treg or CAR-T products, providing a robust platform to promote in vitro enrichment and in vivo engraftment.

Introduction

Adoptive transfer of genetically modified autologous T cells has emerged as an important therapeutic strategy for hematological malignancies. While current FDA-approved therapies utilize viral vectors to deliver chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) or T cell receptors (TCRs),1 gene editing in primary human T cells using designer nucleases has been reproducibly achieved, and gene-editing strategies to improve CAR-T cell efficacy are being actively pursued.2,3 In addition to cancer applications, T cell therapies focused on isolation and ex vivo expansion of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Treg) are being developed as a potential strategy for restoring tolerance in autoimmune diseases and solid organ transplant.4,5,6 Natural or thymic Treg cells (tTreg) are potent mediators of self-tolerance but represent only a small subset of circulating CD4+ T cells.7 Our group recently developed a gene-editing strategy to convert peripheral blood CD4+ T cells into immunosuppressive Treg-like cells through the site-specific integration of a strong promoter upstream of the FOXP3 gene,8 the master regulator of Treg cell fate.7,8 Work to date suggests that these engineered Treg (EngTreg) may exhibit therapeutic potential in a variety of autoimmune disorders as well as graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).8,9

Gene editing to generate therapeutic CD4+ or CD8+ T cells via homology-directed repair (HDR)-based approaches results in a mixed population of edited and unedited cells. This is of particular concern for EngTreg, as unedited CD4+ T cells may act as immune effectors and exacerbate disease.4,5,6 To that end, selectable markers have been paired with HDR editing to allow for column or fluorescence-activated cell sorting-based enrichment. Alternatively, a method that could selectively promote the survival or expansion of the edited cell product could enhance both manufacture and application of engineered T cell therapies.

T cell survival and proliferation depends on signals mediated by the TCRs, co-stimulatory receptors, and cytokine receptors. While each of these signals play crucial roles in various aspects of T cell activation, signals mediated by the cytokine receptor common γ chain (γC or IL2RG) are critical for supporting both T cell survival and the massive T cell expansions that may occur following initial TCR-mediated activation.10 The central role of IL2RG-mediated signaling in T cell survival and proliferation is illustrated by the array of cytokine/cytokine receptors that pair with IL2RG for signaling as well as the profound immunodeficiency that accompanies mutations in the IL2RG gene that abrogate its function.11,12

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) is a cytokine of particular interest to T cell therapy due to its role in supporting survival and proliferation of CD4+ T cells. IL-2-dependent signaling involves its initial binding to a high-affinity subunit (IL2RA or CD25) that lacks intrinsic signaling function.13 The complex of IL-2 and IL2RA then interacts with two other receptor subunits—the common γ chain (IL2RG) and the IL-2 cytokine receptor β (IL2RB) chain, which undergo heterodimerization-induced conformational changes to mediate signaling.13 IL-2 is crucially important for Treg homeostasis.14 In both genetic mouse models and human subjects, altered function in IL-2 signaling components (IL2RA, IL2RB, and STAT-5) increase the risk for autoimmune diseases including type I diabetes.15,16,17 CD4+ T cells, including Treg, require IL-2 in the culture medium for survival and expansion ex vivo. Beyond this in vitro requirement for IL-2, a significant concern for cell-based therapies involving CD4+ T cells, including tTreg or EngTreg, is the ability of these cells to persist in vivo without sustained IL-2 support.4,5

There have been previous attempts to modulate IL-2 signaling to control T cell or Treg expansion in an inducible manner.18 Site-specific mutants of IL-2 and IL2RB have been developed that allow for specific expansion of mutant receptor-expressing cells when the mutant IL-2 is present.19 Such orthogonal IL-2/IL2RB systems have been applied to both CAR-T cells and Treg, showing improved therapeutic efficacy in in vivo tumor or solid organ transplant models.20,21,22,23 IL-2-binding monoclonal antibodies have been shown to modulate immune response in vivo and promote T cell expansion,24 while IL-2 cytokine-antibody fusions have also been developed that engage the high-affinity IL2RA that is highly expressed on Treg, promoting Treg expansion in vivo.25 Finally, IL-2 mutants (also known as muteins) with reduced affinity for IL2RB and increased dependence on high-affinity IL2RA have been developed.18 Candidate IL-2 muteins can promote expansion of human or murine Treg populations and limit autoimmune disease progression in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice.26,27

Here, we have developed a cell-intrinsic technology for provision of inducible IL2R signaling to CD4+ T cells, with the goal of providing a means through which T cell survival and activation in culture ex vivo and in vivo may be supported through a tightly regulated “drug-on” mechanism. While previous attempts have been made to utilize chemically inducible dimerization (CID) technology28 to mediate signaling of synthetic cytokine receptors, these receptors were not able to support cell proliferation.29 This previous work suggested that such architectures did not reproduce receptor cytoplasmic tail movements required for a fully competent signaling conformation. Consequently, we explored multiple alternative architectures in which CID domains were placed within truncated IL2RB and IL2RG receptors to recapitulate natural heterodimerization-induced signaling events. We identified a single compact architecture that supported robust drug-regulated proliferative signaling in primary human T cells, allowing for selective enrichment both ex vivo and in vivo.

Results

Engineering a chemically inducible signaling complex capable of mimicking IL-2 signaling

We designed and evaluated a series of chimeric proteins in which the rapamycin-binding domains FKBP and FRB (the rapamycin-binding domain of mTOR) are fused to fragments of IL2RG and IL2RB, respectively (Figure 1A); the two chimeric proteins together are referred to hereafter as chemically inducible signaling complexes (CISCs). To permit binding by either the clinically relevant therapeutic agent, rapamycin, or the heterodimerizing rapamycin analog, AP21967, the FRB domain contained a T2098L point mutation.28 In these architectures, the rapamycin-binding domains replaced most of the extracellular domains of IL2RG and IL2RB. Upon rapamycin binding, the CISC is designed to form a trimeric FKBP-(rapamycin)-FRB complex, resulting in heterodimerization of the intracellular signaling domains of IL2RG and IL2RB.

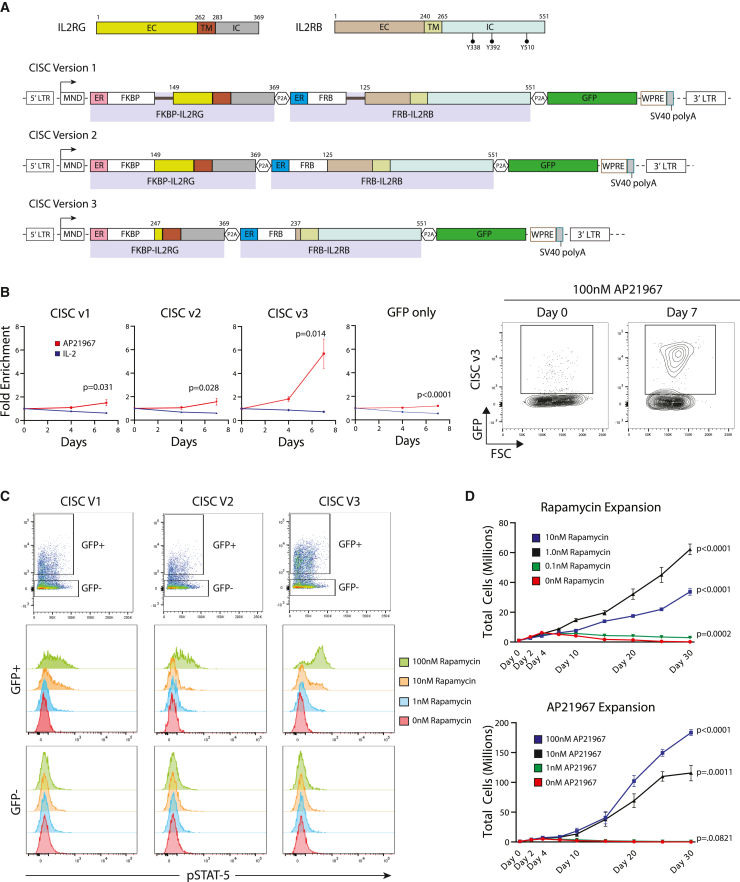

Figure 1.

Identification of an optimized IL-2 CISC architecture for in vitro enrichment and expansion of CD4+ T cells

(A) Schematic representation of domain structures of human IL2RG and IL2RB (upper schematic) and the alternative IL-2 CISC LV expression cassettes (lower schematics). Numbering indicates amino acid residues within relevant protein structure. EC, extracellular domain; TM, transmembrane domain; IC, intracellular domain; ER, endoplasmic reticulum targeting signal sequence. Black bars in CISCv1 represent a flexible linker sequence. (B) Left panel: progressive fold enrichment for GFP+ primary human CD4+ T cells following transduction with alternative CISC LV constructs following culture in 50 ng/mL IL-2 versus 100 nM AP21967. Right panel: representative GFP flow plots for CISCv3 on days 0 and 7. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 3 technical replicates. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of STAT-5 phosphorylation in primary human CD4+ T cells expressing alternative CISC constructs following 30 min treatment with increasing doses of rapamycin. Upper panels: GFP+ and GFP–gating for each sample. Lower histograms: intracellular phospho-STAT-5 staining within each GFP gate. (D) Primary human CD4+ T cells transduced with CISCv3 were expanded for 25 days using the indicated doses of rapamycin (upper panel, n = 4) or AP21967 (lower panel, n = 3). Total cell numbers were determined for each technical replicate at the indicated time points. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 1A depicts three IL-2 CISC designs with alternative truncations of the extracellular domain fused to FRB or FKBP, each retaining the full-length IL2RB or IL2RG transmembrane and intracellular domains, respectively (Figure 1A). IL2-CISCv1 and IL2-CISCv2 included >100 amino acids of the extracellular ligand-binding domains, while IL-2-CISCv3 lacked nearly the entire extracellular domain. In addition, for IL2-CISCv1, a tripeptide (GSS) linker was added between the FRB and FKBP rapamycin-binding motifs and downstream IL2RB and IL2RG receptor chains, respectively, to promote greater flexibility for FRB-FKPB dimerization. In each construct, a cis-linked fluorescent protein marker, GFP, and a woodchuck hepatitis virus post-translational regulatory element (WPRE) were included to label CISC-expressing cells and improve mRNA expression, respectively. Peptide coding sequences were separated by in-frame 2A ribosome-skip peptide elements.

Each construct was cloned into a lentiviral vector (LV) backbone containing the constitutively active, γ-retroviral-derived promoter, MND,30 and used to transduce primary human CD4+ T cell populations. As shown in Figure 1B, to determine whether candidate CISC constructs were capable of mimicking IL2R signaling, transduced cells were expanded in medium containing either IL-2 or AP21967 with selection tracked by GFP expression over 7 days, in comparison with an MND-driven “GFP only” lentivirus control. All IL-2 CISC constructs led to a progressive increase in the percentage of GFP+ cells in the presence of AP21967, while GFP positivity remained stable in cells maintained in IL-2 (Figure 1B). Whereas CISCv1 and CISCv2 exhibited a modest increase in GFP+ cells (∼2-fold), CISCv3 displayed robust (∼6-fold) enrichment.

STAT5 is a proximal target of IL2R signaling, and phosphorylation of STAT5 is a canonical indicator of IL2R activation.31 Therefore, we next determined if this key signaling pathway was also activated in response to CISC engagement. We used flow cytometry to determine the level of intracellular STAT5 phosphorylation (pSTAT5) in T cells transduced with the CISC variants and cultured in increasing doses of rapamycin in the absence of IL-2. Using GFP−, non-transduced cells as an internal control, we observed dose-dependent induction of pSTAT5 in response to rapamycin for all CISC variants, signaling changes that were specific to the GFP+ population (Figure 1C). Again, consistent with our enrichment results, the level of pSTAT5 was higher in cells expressing CISCv3. Western blot analysis for AKT phosphorylation (p-serine 473 or p-threonine 308) demonstrated a similar kinetic in response to rapamycin or IL-2 stimulation; findings consistent with activation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway (Figure S1A). Finally, a time course of pSTAT5 induction in response to CISCv3 activation using rapamycin showed peak phosphorylation at 30 min and subsequent decline over 24 h, findings that mirrored activation in response to IL-2 (Figure S1B). Together, these findings suggested that the receptor architecture in CISCv3 mediated a robust, IL-2-like, downstream signaling program.

The CISCv3 architecture utilizes signal sequences from lipocalin 2 (LCN2) and CD8a to promote surface expression of the fusion receptor chains. To assess subcellular localization, we generated a CISCv3 LV expression construct with HA and V5 epitope tags fused to the N termini of FKBP-IL2RG and FRB-IL2RB, respectively. In parallel, based upon a previous study,29 we generated a CISCv3 equivalent construct using matched Ig-kappa signal sequences substituted for LCN2 and CD8a (Figure S2A). In either a murine pre-B cell line Ba/F3 (Figures S2B and S2C) or primary human CD4 T cells (Figure S2D), culture with 100 nM AP21967-induced equivalent levels of CISC enrichment regardless of signal sequence. Immunofluorescence staining for the HA epitope tag in LV-transduced 293T cells demonstrated a primarily cytoplasmic staining pattern for both LCN2/CD8a and Ig-kappa signal sequence CISC constructs (Figure S2E).

Development of an intracellular rapamycin decoy

IL-2 signaling promotes proliferation of activated T cells, in part through phospho-STAT5-dependent mechanisms. Therefore, we next examined the capacity of rapamycin or AP21967 to induce proliferation and expansion of CD4+ T cells expressing CISCv3. Over 25 days, cultures treated with 1–10 nM rapamycin exhibited a progressive increase in CISC-expressing T cells (Figure 1D, upper panel). However, cell expansion plateaued at 1 nM rapamycin and decreased with higher doses (10 nM). Proliferation was impacted despite the observation that acute treatment with 10 nM rapamycin induced higher levels of pSTAT5 compared with the 1 nM dose (Figure 1C). These findings suggested that rapamycin-dependent inhibition of endogenous mTOR might limit the ability of CISC signaling to induce cell proliferation in response to rapamycin. Consistent with this hypothesis, treatment of CISCv3-expressing cells with the rapamycin analog, AP21967, that does not bind mTOR, induced dose-dependent cellular expansion at doses up to 100 nM, with no apparent inhibitory effect (Figure 1D, lower panel).

To rescue the limited cell expansion of CISC-expressing cells in 10 nM rapamycin, we modified CISCv3, adding a cis-linked FRB domain lacking an ER-targeting signal sequence. We predicted that this would generate a “free” cytosolic FRB protein capable of competitively binding to cytosolic rapamycin, limiting its engagement with mTOR. We refer to this architecture as the “Decoy CISC” (Figure S3A).

To assess the potential protective effect of the cytosolic FRB domain on enrichment and proliferation of CISC-expressing cells, we transduced CD4+ T cells using LV expressing either CISCv3 or Decoy CISC, each with a cis-linked mCherry marker. Transduced populations were tracked for mCherry enrichment (Figure S3B) and relative fold expansion (Figure S3C) in the setting of increasing doses of rapamycin (1–10 nM rapamycin) or 100 nM AP212967. When cultured in the presence of 1 nM rapamycin or 100 nM AP21967, these constructs displayed similar fold expansion, while significantly higher expansion was observed for Decoy CISC-expressing cells at the higher rapamycin dose (10 nM). To assess the impact on mTOR signaling, we performed flow cytometry analysis of the downstream target, S6, phosphorylated in response to mTOR activation.32 CISC- or Decoy CISC-expressing cells were expanded in vehicle (DMSO) or 10 nM rapamycin for 6 days, followed by staining for phospho-S6 (pS6). While no change was detected in CISC cells expanded in 10 nM rapamycin, Decoy CISC cells under the same conditions displayed increased levels of pS6 (Figure S3D).

Together, these findings demonstrate that co-expression of cytosolic FRB domain can limit the rapamycin mediated inhibitory effect on cell expansion and that the Decoy CISC design is permissive for mTOR signaling, even in the presence of higher-dose rapamycin. We thus incorporated the cytosolic FRB domain into all subsequent CISC cassettes.

Incorporation of the IL-2 CISC into a FOXP3 gene-editing strategy

To assess the functional properties of IL-2 CISC technology for potential use in T cell therapeutic applications, we next incorporated the CISC design into a HDR-based gene-editing strategy. We previously demonstrated conversion of primary human CD4+ T cells into engineered T regulatory cells (EngTreg) via targeted insertion of the MND promoter upstream of the FOXP3 open reading frame.8,9 EngTreg generated using this approach exhibit robust immune suppression in vitro and in vivo. We hypothesized that co-expression of the CISC with FOXP3 would permit generation of EngTreg cells capable of enrichment and expansion in vitro using rapamycin, simplifying cell manufacturing. In addition, we predicted that CISC-expressing EngTreg would exhibit a selective advantage for in vivo engraftment and retention in the context of systemic rapamycin treatment.

To test these ideas, we designed a recombinant (r)AAV6 HDR donor vector to deliver a CISC cassette under the control of the MND promoter that, following successful HDR, leads to in-frame, cis-linked, expression of all CISC elements, in parallel with endogenous FOXP3 expression (Figure 2A). For gene editing, Cas9 ribonucleoprotein containing a validated guide RNA targeting coding exon 1 of FOXP3,8 was co-delivered in association with the rAAV6 as an HDR template.

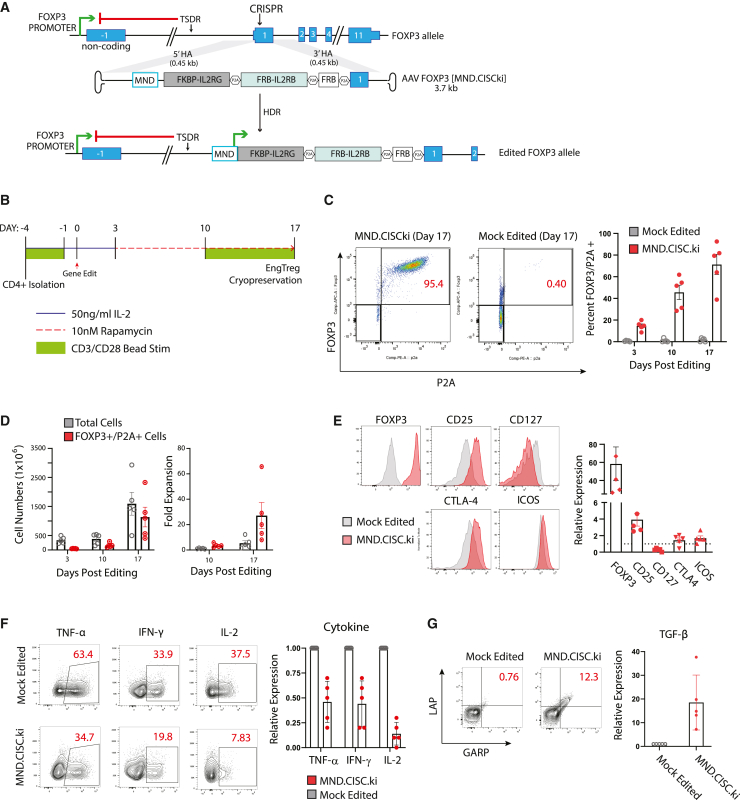

Figure 2.

CISC EngTreg cells have Treg-like immunophenotype and cytokine profile after rapamycin enrichment

(A) Diagram of the FOXP3 locus and an AAV donor template [MND.CISCki] designed to introduce the CISC elements via CRISPR-meditated HDR. Successfully gene-edited locus (bottom) drives constitutive expression of the CISC components and endogenous FOXP3 from the transgene’s MND promoter, bypassing the methylated TSDR silencing element. (B) CISC EngTreg manufacturing strategy. Timing of CD3/CD28 activation beads, IL-2, and rapamycin inclusion in the culture medium is shown. Mock-edited cells were cultured with 50 ng/mL IL-2 throughout with matched CD3/CD28 activation. (C) Left panel: representative FOXP3/P2A flow plots for MND.CISCki gene-edited cells and mock-edited cells on day 17. Right panel: proportion of FOXP3+/P2A+ cells on days 3, 10, and 17 post-editing. CISC EngTreg were manufactured using five independent PBMC donors (mean ± SEM, n = 5). (D) Quantification of the cell number (left) and relative fold expansion (right) for total cells versus HDR-edited (FOXP3+/P2A+) cells. (E) Immunophenotyping of mock-edited versus CISC EngTreg. Left panels: expression of Treg markers at day 3 after thawing of cryopreserved cell populations. Right panel: relative fold change in MFI of indicated Treg markers in CISC EngTreg versus mock cells (dotted line). (F) Mock and CISC EngTreg cells were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 5 h to assess production of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2. Left panels: representative flow plots. Right panels: relative expression for indicated cytokines in CISC EngTreg versus mock cells. (G) Mock-edited or CISC EngTreg cells were stimulated with soluble CD3 and CD28 antibodies for 24 h, followed by flow analysis for LAP and GARP to assess TGF-β production. Left panels: representative flow plots. Right graph: relative TGF-β expression in CISC EngTreg versus mock cells. For (C)–(G), data represent n = 5 biological replicates and are presented as mean ± SEM.

To determine whether CISC expression within the targeted FOXP3 locus would permit rapamycin-mediated selective expansion of CISC EngTreg, we developed a CD4 T cell-editing and expansion protocol where treatment with 10 nM rapamycin was initiated 3 days post-HDR editing, allowing time for CISC expression and cell recovery from the editing procedure. As shown in Figure 2B, edited cells were first selected for 7 days in rapamycin medium without IL-2, followed by a secondary CD3/CD28 bead stimulation and an additional 7 days of culture in rapamycin. Mock-edited cells, which cannot survive in IL-2-free medium, were cultured in medium with IL-2 (50 ng/mL) during an identical expansion schedule. CISC EngTreg cells were detected by flow cytometry analysis based on intracellular staining for cells co-expressing FOXP3 and the P2A residual peptide tag (present on elements of the CISC; Figure 2C, left panel).

CD4+ T cells from five different human donors were edited to produce CISC EngTreg or mock-edited cells, followed by enrichment and expansion as shown in Figure 2B. Flow cytometry detection of CISC EngTreg (based on FOXP3 and P2A positivity) was assessed on days 3, 10, and 17 (Figure 2C, right panel), showing progressive enrichment. From an initial population of <20% edited cells, the final purity of CISC EngTreg cells ranged from 40% to 95% across the T cell donors. Cell counts were performed at matched time points to determine total and CISC EngTreg cell numbers (Figure 2D, left panel). Total cell numbers increased progressively for both mock and CISC EngTreg populations, although CISC EngTreg cells displayed a higher fold expansion (Figure 2D, right panel) due, in part, to the smaller starting population. The differences in purity across donors suggested variability in HDR rates and/or in efficiency of rapamycin selection. As one way to address this, we incorporated CD25 column-based purification on day 6 to enrich for CD25hi HDR-edited, FOXP3 “programmed” cells (Figure S4A). As predicted, we observed higher levels of CD25 expression in edited versus unedited populations (Figure S4B) and CD25 enrichment improved CISC EngTreg purity and expansion particularly at earlier time points (Figures S4C–S4E).

To assess IL-2 signaling in the context of HDR-edited cells, we examined pSTAT5 in enriched CISC EngTreg cells (Figure S5). In the absence of stimulation, CISC EngTreg exhibited a higher basal level of pSTAT5 in comparison with mock-edited cells, possibly due to retained cytosolic rapamycin continuing to engage CISC receptors localized to an internal membrane surface33 (Figure S2E). Notably, the levels pSTAT5 were consistently higher in CISC EngTreg compared with mock cells in response to 50 ng/mL IL-2 (Figure S5A). pSTAT5 levels increased in a dose-dependent manner in response to rapamycin only in CISC EngTreg (Figure S5B).

While these findings demonstrated that IL-2 CISC can select for relevant HDR-editing events when paired in cis, it remained unclear whether CISC expression or rapamycin selection might impact the biology of enforced FOXP3 expression. Previously, we demonstrated that enforced constitutive FOXP3 expression in EngTreg induced Treg marker expression.8 CISC cell products generated from five separate peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) donors were subjected to flow-based phenotypic analyses in comparison with mock cells. CISC EngTreg cells displayed key Treg features including increased expression of FOXP3, CD25, CTLA-4, and ICOS, and decreased expression of CD127 (Figure 2E). In parallel, we determined whether CISC EngTreg exhibit a switch in secreted cytokine profile consistent with an immunosuppressive program. In response to phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)/ionomycin stimulation, CISC EngTreg, in comparison with mock-edited CD4+ T cells, reduced expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, and increased expression of the immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-β (based upon co-expression of latency-associated peptide [LAP] and glycoprotein A repetitions predominant [GARP])34 (Figures 2F and 2G). In summary, CISC EngTreg are efficiently enriched and expanded in rapamycin and express an immunophenotype and a cytokine profile consistent with a Treg program.

CISC editing generates functional, immunosuppressive EngTreg

Next, we directly assessed the functional immunosuppressive capacity of CISC EngTreg. An important characteristic of Treg is the ability to suppress the in vitro proliferation of activated autologous CD4+ effector T cells (Teff). As shown in Figure 3A, autologous Teff cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (CTV) and induced to proliferate by co-stimulation with CD3/CD28 beads. Teff cultured alone displayed a strong proliferative response that was inhibited by co-culture with CISC EngTreg to a similar extent as by purified, autologous thymic-derived tTreg. As expected, Teff proliferation was inhibited to a much greater extent by either CISC EngTreg or tTreg compared with the addition of control (mock)-edited CD4+ T cells.

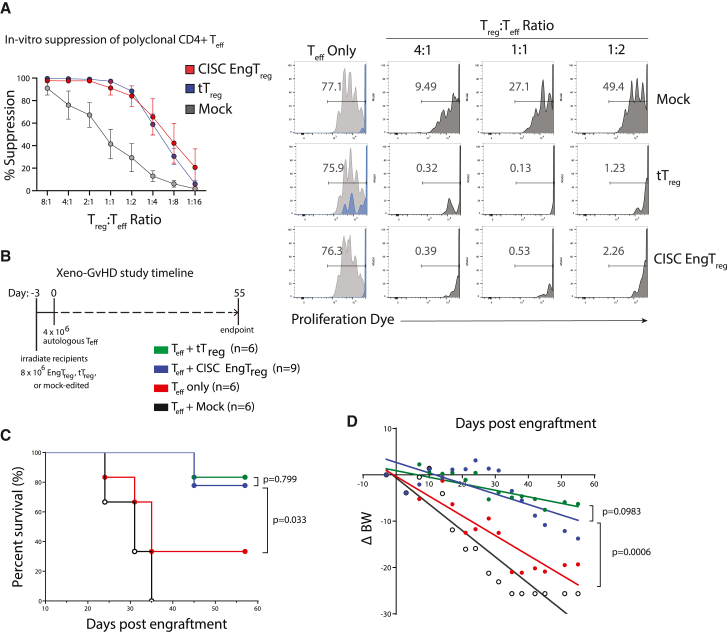

Figure 3.

CISC EngTreg are immunosuppressive in vitro and in vivo

(A) Left: graph shows the percent suppression (mean ± SEM; n = 5) of effector T cell proliferation after 4 days in culture with CD3/CD28 activation beads and the indicated ratio of autologous CISC EngTreg, mock, or tTreg. Percentage suppression was calculated as ((%) Teff dividing without Treg – (%) Teff dividing with Treg)/(%) Teff dividing without Treg) × 100. Right panels: representative flow cytometry histograms for the in vitro suppression assay. Fluorescence of the CTV-labeled Teff cells is shown for the Treg treatment groups indicated at the top of each column. For the Teff only group (no Treg), histograms of CD3/CD28-stimulated Teff cells (gray) are shown overlaid with that of the same cells cultured without stimulation (blue). Histograms for dye-labeled Teff cells co-cultured with different ratios of mock cells, CISC EngTreg, or tTreg are shown in dark gray. (B–D) Xenogeneic GvHD study in NSG mice. (B) Timeline of murine xeno-GvHD study. Minimally irradiated NSG mice were delivered tTreg, mock-edited cells, CISC EngTreg cells, or nothing (8 × 106 cells/mouse, day −3) followed by CD4+ Teff cells (4 × 106 cells/mouse) delivered 3 days later for all groups (day 0). (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of NSG mice monitored up to 57 days after Teff injection; mice were euthanized at pre-determined humane endpoints. p values were calculated based on log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (D) Linear regression analyses of body weight changes (ΔBW, %) were calculated as ((current BW − original BW on day −3)/original BW at day −3) × 100.

Next, we assessed in vivo immunosuppressive function of CISC EngTreg cells using an established xenogeneic GvHD model based upon adoptive transfer of human CD4+ Teff into immunodeficient NOD-scid-IL2rγNULL (NSG) mice.8,35 To test the ability of CISC EngTreg cells to modulate disease, we delivered 8 × 106 CISC EngTreg, purified tTreg, or mock-edited cells to minimally irradiated NSG recipients, followed 3 days later by adoptive transfer of 4 × 106 autologous CD4+ T cells. Body weight, GvHD symptom onset, and overall survival were monitored for 55 days after Teff transplant (Figure 3B). Mice receiving CISC EngTreg showed delayed GvHD development relative to mice receiving the mock-edited or Teff only control groups (Figure 3C). Importantly, overall survival was identical in mice receiving CISC EngTreg and purified tTreg. Body weight change followed a similar pattern to overall survival, with CISC EngTreg cells providing a similar level of protection from GvHD disease progression as tTreg (Figure 3D). Thus, incorporation of the CISC at the FOXP3 locus and subsequent enrichment and expansion in rapamycin generates EngTreg with functional characteristics similar to tTreg.

Rapamycin promotes engraftment and survival of CISC EngTreg in vivo

A key design feature of a CISC-expressing therapeutic T cell product is a theoretical advantage for engraftment and/or survival following adoptive transfer in the setting of systemic rapamycin therapy. This in vivo selective advantage is predicted to be particularly important for EngTreg when IL-2 is limited. To directly model and assess this idea, we performed in vivo studies to track CISC EngTreg in NSG mice treated with and without rapamycin. In NSG animals, in the absence of human Teff, EngTreg cells lack any source of human IL-2 and are predicted to display only transient engraftment.

To facilitate in vivo detection of transplanted cells in peripheral blood and tissue samples, we initially utilized an alternative HDR template, MND.μCISC.GFPki, that included a truncated but signaling-competent version of the IL2RB (IL2RBmin) subunit,36 referred to hereafter as μCISC, expressed in cis with GFP as an in-frame fusion with the N terminus of the FOXP3 protein (Figure 4A). This μCISC cassette design was used for initial engraftment studies because: (1) the reduced size of the donor cassette improved rAAV packaging and HDR rates (Figure S6A) and (2) the GFP fusion facilitated tracking of edited cells in vivo using flow cytometry. Based on GFP positivity, μCISC EngTreg were enriched in vitro in 10 nM rapamycin with similar kinetics as CISC EngTreg (Figures S6B and 4B, left panel) and achieved a similar level of expansion (Figure 4B, right panel, compare with Figure 2D). μCISC EngTreg also displayed a similar Treg immunophenotype (Figure S6C) and in vitro immunosuppressive activity (Figure S6D).

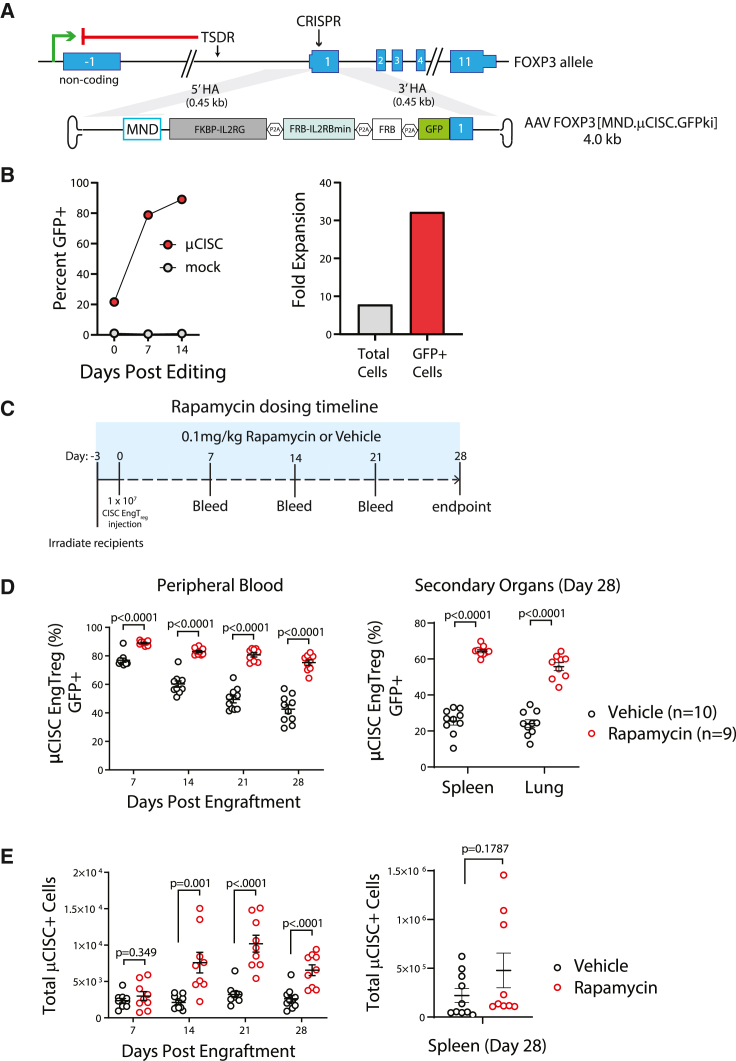

Figure 4.

Systemic rapamycin improves in vivo persistence of adoptively transferred CISC EngTreg cells

(A) Diagram of FOXP3 locus and an AAV donor template [MND.μCISC.GFPki] designed to introduce a truncated CISC with a shortened IL2RB subunit in conjunction with a GFP tag via CRISPR-meditated HDR. The homology arms flanking the MND.μCISC.GFPki cassette are the same as the full-length CISC AAV donor template used in the previous figures. (B) Left panel: enrichment of μCISC EngTreg and (right panel) fold change in cell numbers over time post-editing when cultured in 10 nM rapamycin. (C) Timeline of rapamycin in vivo study. NSG mice were minimally irradiated and received 1 × 107 μCISC EngTreg cells on day 0. Rapamycin (0.1 mg/kg) or vehicle solution were delivered i.p. to corresponding groups of animals every other day, starting at day −3 and extending until the end of study (4 weeks after cell delivery). Peripheral blood was collected weekly from all animals and tissues from spleen and lung were collected at the time of sacrifice. (D) The percentage of GFP+ cells (of hCD45+, hCD4+) in peripheral blood at each collection point and indicated tissues at time of sacrifice as assessed by flow cytometry. (E) Total numbers of GFP+, hCD45+, and hCD4+ cells per 100 μL sample in peripheral blood and spleen. Data presented as mean ± SEM.

To determine the capacity for rapamycin to promote engraftment and/or survival of CISC EngTreg in vivo, we transplanted 1 × 107 μCISC EngTreg into recipient NSG animals (Figure 4C) treated with 0.1 mg/kg rapamycin or vehicle control on alternate days beginning 1 day before the cell transfer. The high dose of CISC EngTreg per animal was selected in part to ensure a detectable level of engrafted cells in peripheral blood samples at early time points. Peripheral blood was collected weekly and animals were sacrificed on day 28 for tissue analysis. Significantly higher proportions of GFP+ μCISC EngTreg were present in peripheral blood in the rapamycin-treated group at all time points (Figure 4D, left). Spleen and lung samples also revealed a higher percentage of EngTreg in rapamycin-treated animals (Figure 4D, right). Consistent with these findings, the absolute number of EngTreg was significantly increased in peripheral blood of rapamycin-treated animals at later time points, and trended higher in the spleen at endpoint (Figure 4E). Together, these data suggest that rapamycin can provide IL-2-like signaling support to CISC EngTreg in vivo, promoting engraftment and retention in the absence of exogenous IL-2.

Next, we performed in vivo experiments using full-length CISC EngTreg to determine whether this construct mediated a similar rapamycin-dependent increase in engraftment. We also compared engraftment supported by rapamycin versus human IL-2. NSG mice were adoptively transferred 8 × 106 CISC EngTreg cells and treated with 0.05 mg/kg rapamycin, 50,000 IU human IL-2, or vehicle alone for 14 days (Figure S7A). Compared with vehicle control, we observed similar increases in both the percentage and absolute number of EngTreg (based on CD25+/CD127− flow cytometry) in rapamycin and IL-2 treatment groups (Figures S7B and S7C).

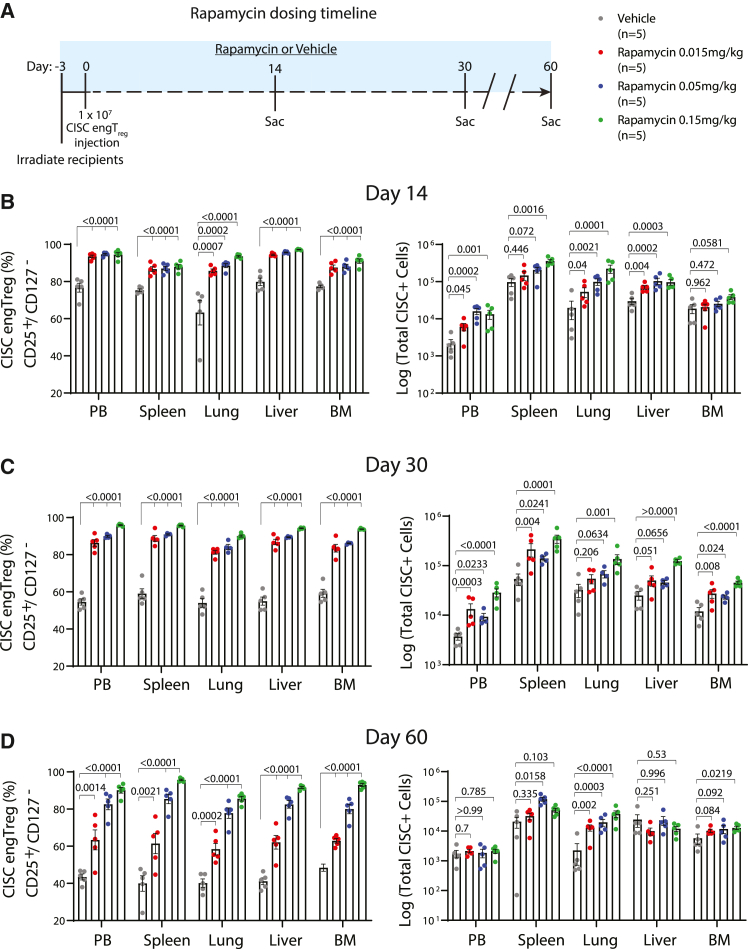

In a second set of studies, we assessed rapamycin dosing requirements, including whether subtherapeutic rapamycin levels might be sufficient to mediate in vivo survival of CISC EngTreg. We first assessed in vivo rapamycin serum levels after repeated dosing in NSG mice. Minimally irradiated recipient animals received 5 × 106 human CD3+ Teff cells (to mimic resident T cell populations capable of accumulating intracellular rapamycin) and then dosed with 0.015 or 0.05 mg/kg rapamycin every other day for 12 days (Figure S8A). Peripheral blood was collected at multiple time points within a 48 h window following the final rapamycin dose for quantitation of rapamycin levels. Subtherapeutic serum rapamycin trough levels (below 5 ng/mL) were observed for both dosing regimens (Figure S8B). Next, NSG recipient mice were transplanted with 1 ×107 CISC EngTreg and treated with 0.015, 0.05, and 0.15 mg/kg rapamycin (or vehicle control) for 60 days. Subgroups of recipients were sacrificed on days 14, 30, and 60 (Figure 5A) for collection of peripheral blood, spleen, lung, liver, and bone marrow. Flow analysis of leukocytes from these tissues for CD4+CD25hi/CD127− T cells was used to identify EngTreg. Strikingly, we observed an increase in the percentage of CD4+CD25hi/CD127− cells within rapamycin-treated groups, across all time points and across multiple tissues. In addition, there was a significant increase in the number of CD4+CD25hi/CD127− cells in rapamycin-treated groups at earlier time points. This numerical increase in EngTreg decreased over time, likely reflecting a lack of TCR engagement for most EngTreg within the NSG host environment (Figures 5B–5D). Cumulatively, these data demonstrate that the IL-2 CISC can effectively promote the in vivo selection and retention of transplanted CISC-expressing cells in the setting of either a therapeutic or subtherapeutic rapamycin dosing regimen.

Figure 5.

In vivo persistence of CISC EngTreg cells is rapamycin dose dependent

(A) Timeline of rapamycin dose-response study. On day 0, 60 mice were delivered CISC EngTreg cells (8 × 106 cells/mouse) 3 days after minimal irradiation. Animals were divided into 4 treatment groups of 15 mice receiving 0.015, 0.05, and 0.15 mg/kg rapamycin or vehicle, respectively. Five animals among each group were sacrificed at days 14, 30, and 60 post engraftment. Rapamycin or vehicle solution were delivered i.p. to corresponding groups every other day, starting at day 0 when CISC EngTreg cells were i.v. delivered (3 days after irradiation). (B–D) Peripheral blood and tissues from spleen, lung, liver, and bone marrow were collected at time of sacrifice and subjected to flow analyses to examine CISC EngTreg percentage and absolute numbers. Data presented as mean ± SEM. p values as listed are for vehicle versus each individual rapamycin dose.

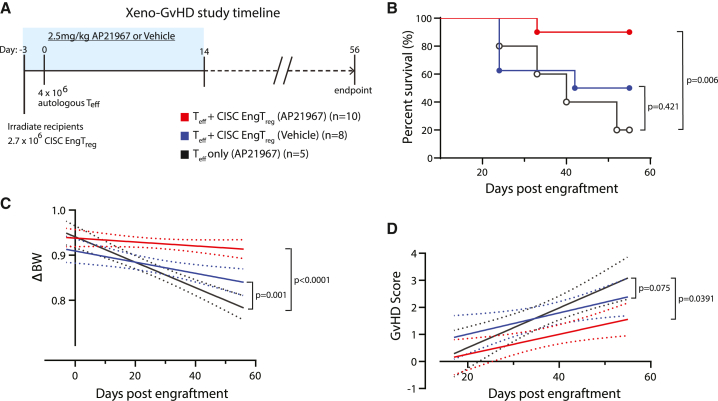

CISC activation in vivo limits GvHD following delivery of a subtherapeutic dose of CISC EngTreg

A fundamental clinical benefit of IL-2 CISC would be the capacity to amplify the therapeutic activity of CISC EngTreg. To address this question, we utilized a modified version of our in vivo xeno-GvHD model. Because rapamycin treatment alone can ameliorate GvHD by inhibiting the proliferation of Teff cells,37 we used AP21967 as an in vivo CISC dimerizer as this agent does not impact mTOR signaling. As described above (Figures 3B–3D), CISC EngTreg modulate GvHD in the absence of in vivo CISC activation. Therefore, we first performed a dose titration experiment to identify a subtherapeutic dose of EngTreg. Irradiated NSG mice were transplanted with various ratios of CISC EngTreg: autologous Teff (2:1 and 0.7:1), or a 2:1 ratio of mock-edited T cells: autologous Teff, and monitored for body weight change and GvHD score (Figure S9A). While mock-edited cells did not prevent disease (Figure S9B), the 2:1 Treg:Teff ratio was protective and, in this setting, in vivo CISC engagement by AP21967 did not improve disease outcome (Figure S9C). In contrast, we observed improvement in survival and body weight with AP21967 treatment in the 0.7:1 Treg:Teff cohort (Figure S9D). Based on these findings, we performed an expanded study using a larger cohort of mice adoptively transplanted with a Treg:Teff ratio of 0.7:1 and treated for a 2-week period with either AP21967 or vehicle control, with surviving animals monitored for up to 56 days (Figure 6A). Animals engrafted with CISC EngTreg and treated with AP21967 exhibited improved survival, weight loss, and GvHD scores (Figures 6B–6D) in comparison with recipients of either CISC EngTreg in the absence of dimerizer therapy or Teff-only recipients. Thus, IL-2 CISC engagement in vivo promotes increased therapeutic activity that correlates with sustained in vivo engraftment and retention of CISC EngTreg.

Figure 6.

AP20187 supports GvHD prevention by CISC EngTreg in vivo

(A) Timeline of the AP20187-treated murine xeno-GvHD study. Blue box indicates the time period of daily i.p. administration of AP20187 (2.5 mg/kg) or vehicle solution. Body weight was monitored three times per week, starting on day −3 until the end of study; GvHD symptoms were scored weekly starting at day 14. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of NSG mice; mice were euthanized at pre-determined humane endpoints. p values were calculated based on log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (C) Linear regression analysis of body weight changes (ΔBW) was calculated as (current BW − original BW on day −3)/original BW at day −3. (D) Linear regression of weekly GvHD scores.

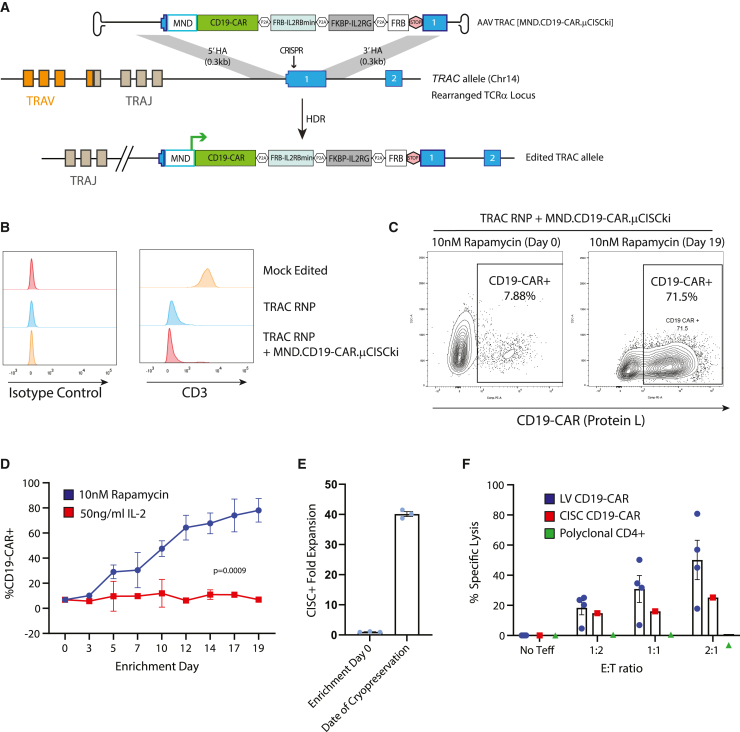

Generation of TCR-deleted, CISC-expressing, selectable CD19-CAR-T cells

While the preceding studies focused on Treg engineering, the IL-2 CISC is anticipated to be broadly applicable to cell-based therapies using Teff cells, including CAR-T cells. While currently approved CAR-T therapies utilize lentiviral delivery of a CD19-CAR, there is interest in expressing the CD19-CAR from the TRAC locus, both to delete the endogenous TCR and to potentially achieve a more physiological level of CAR expression.38 We designed a novel HDR cassette targeting the first exon of human TRAC designed to deliver a CD19-CAR in conjunction with the above previously described μCISC architecture driven by an exogenous MND promoter and terminated with a stop codon followed by an Sv40 poly-adenylation sequence (Figure 7A). This engineering strategy utilized a TRAC-targeting sgRNA which, when delivered alone or in combination with the AAV TRAC [MND.CD19-CAR.mCISCki] HDR template, resulted in a high level of endogenous CD3 knockout in primary human CD4+ T cells (Figure 7B). An HDR-editing rate of 6%–8% was observed across multiple donors based on CD19-CAR expression 3 days post editing (Figure 7C, enrichment day 0). The limited initial editing rate likely reflected the large size of the HDR donor template (4,617 bp). When cultured in 10 nM rapamycin, we observed progressive enrichment for CD19-CAR+ cells to >70% (Figure 7C, enrichment day 19, Figure 7D) with an ∼40-fold expansion in the presence of rapamycin (Figure 7E). The resulting CISC-enriched CD19-CAR T cells showed functional activity in a CD19-target killing assay at least equivalent to CD19-CAR-T cells generated by lentiviral transduction using the identical promoter and CD19-CAR sequences (Figure 7F). Together, these data demonstrate that HDR editing using the CISC platform permits generation of TCR-deleted, functional, and CISC-selectable CD19-CAR-T cells for potential therapeutic application.

Figure 7.

Generation of TCR-deleted, CISC-expressing, selectable, and functional CD19-CAR-T cells

(A) Schematic of engineering strategy for knockin of MND.CD19-CAR.P2A.μCISC cassette into human TRAC locus. STOP element consists of a TAA stop codon followed by an SV40 polyadenylation sequence. (B) Flow cytometry histogram of CD3 surface expression in primary human CD4+ T cells 3 days after the indicated editing procedure. Isotype control stain shown in the left panel. (C) Representative Protein-L flow cytometry plots for MND.CD19-CAR.P2A.μCISC-edited CD4+ T cells at days 0 and 19 of rapamycin enrichment. CD19-CAR CISC T cell percentage (D) and fold expansion (E) after culture in 50 ng/mL IL-2 or 10 nM rapamycin for 19 days. (F) Specific killing (% lysis) of CD19+ K562 target cells in a mixed-target assay at 48 h post-mixing with indicated proportion of effector T cells. LV CD19-CAR-T cells were generated by transduction of CD4+ T cells with MND.CD19-CAR lentivirus (E:T ratios, ratio of effector cell to target cell). Data presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the design and testing of a synthetic IL-2 receptor-based system, CISC, that can effectively select for engineered T cells in vitro and in vivo based on treatment with an exogenous dimerizing agent. Using optimized CISC constructs, we achieve rapid in vitro enrichment of primary human T cells, derived from multiple independent donors, following either LV- or HDR-based CISC delivery in the presence of the clinically approved immunosuppressive agent, rapamycin, or the rapamycin analog, AP21967. T cell enrichment correlated with evidence of downstream IL2R signaling as assessed by pSTAT5 induction, permitting both robust cell expansion and selective survival. Importantly, delivery of the CISC elements in association with cytoplasmic expression of a free FRB domain efficiently countered the negative impact of rapamycin on T cell proliferation, enhancing the cell-intrinsic benefits of the optimized CISC construct. Using the EngTreg platform as a critical case study, we show that co-delivery of CISC within an HDR donor cassette targeting the FOXP3 locus allows for in vivo activation following adoptive transfer. Specifically, in the setting of systemic rapamycin dosing, CISC elements promoted engraftment and long-term retention of EngTreg populations. Strikingly, in animals treated with chemical dimerizer, selective engraftment and survival of CISC EngTreg was achievable even in a fully IL-2-deficient environment. Furthermore, using a subtherapeutic dose of EngTreg, we show that CISC activation increased the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of EngTreg in a GvHD model. Finally, we demonstrate that delivery of CISC and CD19-CAR within the TCRα locus in primary CD4+ T cells permitted selective outgrowth of HDR-edited, endogenous TCR-deficient, functional CAR-expressing Teff. Thus, IL-2 CISC delivery is likely broadly applicable as an engineering tool for enrichment and in vivo manipulation across a wide variety of T cell-based therapies.

At present, most T cell engineering strategies involving site-specific integration of gene expression cassettes mediate targeted integration at efficiencies lower than cassette delivery by random lentiviral transduction. Thus, in vitro selection systems to purify successfully engineered cells are likely to become increasingly important, particularly as more complex engineering strategies are adopted. T cells require cytokine signaling for prolonged survival and expansion, particularly the IL-2/IL-15 signaling cascade activated downstream of the common IL2RG chain. Several previous studies have demonstrated that significant activation of IL2R signaling pathways can be triggered by antibody-mediated heterodimerization of chimeric receptors that include IL2RB/IL2RG tails.39,40 While these chimeric receptors were useful for helping to unravel the biochemistry of IL2R signaling, they have not been developed for translational applications for a variety of reasons, among them the need for clinical development of a bio-orthogonal antibody and the long half-life of antibodies leading to compromised control of cell proliferation. An alternative architecture based on rapamycin-mediated heterodimerization of chimeric receptors constructed from rapamycin analog-binding domains, erythropoietin transmembrane domains, and IL2RB and IL2RG cytoplasmic tails was previously evaluated,29 but proved unable to fully reconstitute IL-2 signaling. This previous architecture failed to activate the PI3K/AKT signal transduction pathway in response to rapamycin,29 suggesting that heterodimerization mediated by a small molecule drug alone might be inadequate to mimic the conformational changes in the IL2RB/IL2RG intracellular tails required for IL2R signaling.

In contrast to previous approaches, we show that the alternative IL2RB-FRB/IL2RG-FKBP fusion architecture within IL-2 CISC is capable of mimicking IL-2 signaling in primary human T cells. CISC expression promoted selective expansion in response to rapamycin and functioned as an in vitro selection tool in the absence of IL-2. IL-2 CISC also functioned in EngTreg when introduced at the FOXP3 locus in conjunction with a constitutive exogenous promoter. After in vitro rapamycin selection, the resulting cells displayed a Treg-like phenotype and functional immunosuppressive capacity equivalent to tTreg (Figures 2 and 3). IL-2 CISC also has potential utility in other cell-editing approaches. For example, pairing IL-2 CISC to a CD19-CAR knockin at the TRAC locus allowed for generation of functional CAR-T cells with endogenous TCR deletion that could be enriched in vitro using rapamycin (Figure 7). Finally, while the data presented here apply the IL-2 CISC in the context of CD4+ T cells, we predict that the CISC will function similarly in CD8+ T cells, potentially allowing for the generation of a wide variety of CISC-expressing engineered T cell products.

While selection for CISC engineered T cells in vitro using rapamycin is an effective enrichment strategy for HDR-edited populations, expansion of therapeutic T cell products may be impacted by rapamycin-mediated CISC selection. We addressed the potential negative effects of rapamycin on T cell proliferation by including a free FRB domain to compete for rapamycin binding, thereby limiting the inhibition of endogenous mTOR. Consistent with this concept, CISC-expressing T cells containing the free FRB tolerated higher rapamycin doses (including doses as high as 10 nM; Figure S3). As 10 nM rapamycin was above the steady-state rapamycin doses explored in vivo in this study, future work is required to determine the upper limits tolerated by CISC-expressing cells in vivo. In addition, the in vitro expansion of TCR-deleted, CISC-selectable CD19-CAR-T cells was less robust than previously described LV-transduced CAR-T products suggesting that additional optimization is required for manufacturing of HDR-edited CISC T cell populations.

A point of concern in autologous T cell-based therapy is in vivo engraftment and retention of engineered T cells after adoptive transfer, particularly for Treg therapies. Treg do not produce IL-2 and instead depend on IL-2 produced in a localized inflammatory setting for proliferation and survival in vivo.13 Rapamycin is utilized as an immunosuppressive agent in the context of solid organ transplantation and in other clinical settings.41 We demonstrate that, in the setting of systemic rapamycin treatment, IL-2 CISC promotes the engraftment and retention of HDR-edited EngTreg cells in a mouse model lacking any endogenous source for human IL-2 (Figure 4). Further, subtherapeutic rapamycin dosing was capable of engaging IL-2 CISC and promoting retention and immunosuppressive function of adoptively transferred EngTreg (Figure 5). This suggests that low-dose rapamycin may permit in vivo CISC functionality in contexts where broader mTOR inhibition is not desired. While our in vivo studies examining CISC EngTreg cells were designed based on previous similar studies8 and generated statistically significant data, relatively low numbers of recipient animals were used and expanding future work to larger cohorts will be important. Development of CISC constructs that function similarly in murine T cells would also be valuable to assess the role for CISC in immune-competent models. Such future work will help to more fully elucidate the rapamycin and cell dose requirements for CISC-engineered products in individual disease contexts to achieve optimal therapeutic benefit.

Treg cells display constitutive high expression of the IL2Rα subunit (CD25), which forms a high-affinity trimeric receptor with IL2Rγ and IL2Rβ. Thus, Treg cells respond more strongly to an equivalent concentration of IL-2 than Teff cells that do not express CD25. IL-2 signaling not only supports Treg survival and proliferation but also directly promotes Treg suppressive function.16 Mice with forced expression of a signaling-deficient IL2Rβ mutant specifically in T cells show increased diabetes development in a NOD mouse model,42 and Treg cells from these mice have reduced ability to block NOD Teff-induced diabetes in an adoptive transfer model. IL-2 signaling directly promotes expression of FOXP3, and thus the Treg suppressive program, via activation of STAT5.43 Our data indicate that the signal-transduction pathway induced by IL-2 CISC induces downstream STAT5 and AKT phosphorylation (Figures 1C, S1, and S5), achieving levels at least equivalent to exogenous IL-2 (Figures S1 and S5). Further, we observed sustained pSTAT5 in CISC-expressing T cells, even after rapamycin withdrawal (Figure S5), potentially due to retained intracellular rapamycin engaging IL-2 CISC complexes pre-assembled on cytoplasmic membrane surfaces. It has been previously reported that exogenously expressed IL-2 receptor components can localize and signal at the intracellular endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi membranes.33 We observed significant cytoplasmic localization of IL-2 CISC chains in cells transduced with CISC lentivirus, regardless of signal sequence used (Figure S2). While not tested, IL-2 CISC may promote Treg suppressive function by “super-charging” the IL-2 pathway through sustained activation in vivo and/or by inducing a higher pSTAT5 levels than achieved by endogenous IL2R. Additional detailed analysis of signaling and transcriptional events following rapamycin-induced CISC versus IL2R engagement are required to define the impacts of CISC engineering on Treg biology.

Finally, the heteromeric nature of the IL-2 receptor suggests potential uses for the IL-2 CISC in more complex T cell engineering strategies. In our current study, we introduced both the IL2RG-FKBP and IL2RB-FRP fusion proteins into a single locus (FOXP3 or TRAC, respectively). However, it should be feasible to divide the IL-2 CISC functional domains into two independent editing events targeting separate genetic loci. This could allow for the delivery of larger cis-linked gene expression cassettes as well as simultaneous genetic manipulation at two endogenous gene targets. Previously characterized loci that could be paired with FOXP3 include beta-2 microglobulin (B2M) to generate allogeneic EngTreg44 or TRAC for replacement of the endogenous TCR with a defined TCR or CAR to generate antigen-specific EngTreg (see Figure 7). Linking half of the IL-2 CISC to each individual edit should permit generation of dual-edited cell products wherein only cells with both successful HDR events would be selected by rapamycin treatment. Taken together, these combined findings suggest that leveraging applications of IL-2 CISC in these and other contexts is likely to help to facilitate a range of next-generation T cell-based therapies.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

Gibson Assembly (New England Biolabs) or InFusion (Clontech) kits were used to clone PCR-amplified or gene-synthesized (Integrated DNA Technology or GenScript) fragments consisting of codon-optimized fusions of FKBP with human IL2RG or FRB with human IL2RB. Fusion protein cassettes were inserted into a pRRL lentiviral backbone (Addgene, no. 36247) downstream of a modified retroviral enhancer/promoter MND and upstream of a WPRE/sv40pA element. All inserted cassettes were sequenced to confirm correct amplifications and fusions. pAAV FOXP3 [MND.CISC.ki] and pAAV FOXP3 [MND.μCISC.GFP.ki] were derived from pAAV FOXP3 [MND.LNGFR-P2A-ki].8 For pAAV_TRAC [CD19_CAR. μCISC.ki], a 5′ homology arm representing 22547272–22547577 of human chromosome 14 and a 3′ homology arm representing 22547578–22547891 of human chromosome 14 were cloned flanking an MND.CD19-CAR.P2A.μCISC coding sequence. These homology arms precisely flank the predicted cut site of the TRAC-targeting sgRNA. The CD19-CAR coding sequence was described previously.45

Viral vector production

Recombinant AAVs were generated and tittered using the triple transfection method and serotype 6 helper plasmid described previously.46 VSV-G pseudotyped Lentiviruses were generated as described.47 Recombinant viral titers were calculated by qPCR using ITR (AAV) or WPRE (LV) specific primers.

Primary human T cell culture, editing, expansion, and LV transduction

Human PBMCs were purchased from Fred Hutch’s Cooperative Center for Excellence in Hematology Cell Processing Core Facility and also from STEMCELL Technologies. CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMCs using EasySep Human CD4+ T cell Enrichment Kit (STEMCELL Technologies), then either frozen or cultured for editing. T cells were cultured in T cell medium (RPMI 1640 with 20% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with human cytokine IL-2 (50 ng/mL). T cells were activated in culture using human T-Expander CD3/28 Dynabeads (Gibco) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for subsequent lentiviral transduction or CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing as described previously.8 sgRNA sequences utilized in CRIPSR-Cas9 editing were: FOXP3, UCCAGCUGGGCGAGGCUCCU; TRAC, GAGAAUCAAAAUCGGUGAAU.

For CISC EngTreg or CISC CD19-CAR-T cell expansion, cells were recovered post-editing in T cell medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL human IL-2 for 3 days, then maintained in T cell medium containing 10 nM rapamycin (Sigma) for 7 days. Cells were then re-plated using a G-Rex gas permeable cell culture system (Wilson Wolf Manufacturing) six-well plates at 1–5 × 106 cells per well in T cell medium with 10 nM rapamycin and re-activated using CD3/CD28 Dynabeads and an additional 7 days. Rapamycin medium was replenished every other day during the expansion phase.

IL-2 pathway analysis

LV-transduced CD4+ T cells or enriched CISC EngTreg cells were cultured without cytokine support for 24 h. Rapamycin at increasing doses or 50 ng/mL human IL-2 was then added to the culture medium and after 30 min cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for intracellular flow cytometry analysis using anti-phospho-STAT5 (BD Biosciences). For analysis of mTOR activation, LV-transduced CD4+ T cells were expanded in 50 ng/mL human IL-2 for 3 days post-transduction, then maintained in medium supplemented with 10 nM rapamycin or DMSO for 6 days. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for intracellular flow cytometry analysis using anti-phospho-S6 (Cell Signaling Technology).

Immunophenotyping assay

Mock-edited and CISC EngTreg cells were thawed and rested in the 20% FBS-RPMI T cell medium supplemented with IL-2 (5 ng/mL) for 3 days, followed by staining for flow analysis. To gate out non-viable cells, live/dead fixable Near-IR dead cell stain (Invitrogen) was included with cell surface staining for CD4 (BD Biosciences), CD25 (BD Biosciences), CD127 (BD Biosciences), and ICOS (AF700, BioLegend). Cells were fixed and permeabilized by True-Nuclear transcription factor buffer set (BioLegend), followed by intracellular staining with antibodies for FOXP3 (BioLegend), CLTA-4 (BioLegend), and p2A (peptide antibody, Novus Biologicals, conjugated with PE-by Lightning link R-PE kit, Novus Biologicals).

CD19-CAR CISC T cells were subjected to surface staining for CD3 (BD Biosciences) with mouse IgG (BD Biosciences) serving as an isotype control stain. Biotinylated Protein-L (GenScript) was used in conjunction with PE-Streptavidin (SAv-PE, BD Biosciences) for detection of CD19-CAR surface expression.

Immunosuppression assays using polyclonal EngTreg

CD4+ Teff cells (“responders”) were isolated from frozen PBMCs then immediately frozen. Once they were thawed, they were rested for 1.5 h and stained with CellTrace Violet (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Autologous mock or EngTreg (“Suppressor”) cells were also thawed and rested together with responder cells and stained with eFluor 670 (eBioscience). Stained suppressor cells were plated in 96-well U-bottom plates and serial diluted out in T cell medium. The CTV stained responder cells (2.5 × 104 cells/well) in T cell medium were then plated in the same plate and stimulated with different ratios of CD3/CD28 T-activator beads (1:4 to 1:20 beads:Teff). The plates were cultured at 37°C for 96 h. All conditions were replicated in two wells, and replicate wells were combined prior to flow cytometry analyses.

Cytokine production assay

Both mock and EngTreg cells were thawed and rested in the 20% FBS-RPMI T cell medium with IL-2 (5 ng/mL) for 3 days, followed by addition of Golgi-stop (Monensin), PMA (50 ng/mL), and ionomycin (1 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 5 h. Cells were processed for flow analysis using a BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit and stained for live/dead, CD4 and IL-2 (Life Technologies), IFN-γ (BioLegend), and TNF-α (Life Technologies). For TGF-β, cells were stimulated with soluble CD3 and CD28 antibodies (1 μg/mL each, Miltanyi Biotech) at 37°C for 24 h and stained for surface expression of LAP (BioLegend) and GARP (BD Bioscience).

Mouse studies

NSG mice were originally purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited specific pathogen-free facility at Seattle Children’s Research Institute (SCRI). All animal work was performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the SCRI.

Xenograft-induced GvHD

Human Treg were isolated by EasySep Human CD4+CD127low Regulatory T cell Isolation kit (STEMCELL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and expanded for 14 days in T cell medium with rapamycin and IL-2 (100 ng/mL). Three days prior to delivery of the Teff xenograft, mock or CISC EngTreg cells were delivered i.v. (8 × 106/mouse) into irradiated (200 cGy) 8- to 10-week-old NSG mice. Baytril was added to drinking water (0.2 mg/mL; Bayer Healthcare) for 14 days following irradiation. On experiment day 0, freshly isolated autologous human CD4+ Teff cells were delivered i.v. (4 × 106/mouse). Mice were weighed three times per week and scored for GvHD symptoms weekly by investigators who were blinded to which treatment each mouse received. Disease score values are intended to reflect the degree of systemic GvHD and represent a previously described48 scoring system that incorporates five clinical parameters: weight loss, posture (hunching), activity, fur texture, and skin integrity. At each time point, study animals were evaluated and graded from 0 to 2 for each criterion. A clinical index was subsequently generated by summation of the five criteria scores (maximum index = 10). Mice from each cohort were euthanized at the end of study, or at any time during the experiment when they lost over 20% body weight. The presence of human T cells was assessed by flow cytometry using antibodies to human CD45 (Life Technologies), CD4 (BD Bioscience), CD25 (BD Bioscience), CD127 (BD Bioscience), FOXP3 (BioLegend), and P2A (Novus Biologicals) in multiple tissues, including peripheral blood, spleen, liver, lung, and bone marrow.

For AP21967 study, NSG mice at age of 8–10 weeks were irradiated at 200 cGy and mock or CISC EngTreg cells were delivered by i.v. injection 3 days before delivery of polyclonal CD4+ Teff cells. AP21967 (Takara Bio) was reconstituted in DMSO at 25 mg/mL, and subsequently diluted in sterile 1.4% Tween-80, 10% PEG-400 (vehicle) to deliver 2.5 mg/kg dose per animal. AP21967 or vehicle solution was delivered daily by intraperitoneal injection, starting at the day of mock and CISC EngTreg cell delivery until 14 days after CD4+ Teff cell injection.

Rapamycin in vivo study

NSG mice at 8–10 weeks of age were sub-lethally irradiated (200 cGy) and i.v. injected with mock, CISC, or μCISC EngTreg cells (1 × 107 cells/mouse) 3 days later. Rapamycin stock of 20 mg/mL was prepared in DMSO, and furthermore diluted in vehicle solution (5% PEG-400, 5% Tween-80). Doses of 0.1, 0.15, 0.05, and 0.015 mg/kg rapamycin or matched volumes of vehicle solutions were i.p. delivered to animals every other day, starting at the day of cell transfer until the end of study. Peripheral blood was collected weekly by retro-orbital bleeding and analyzed for flow analysis. The presence of human T cells was assessed by flow cytometry using antibodies to human CD45 (Life Technologies), CD4 (BD Bioscience), CD25 (BD Bioscience), CD127 (BD Bioscience), FOXP3 (BioLegend), and P2A (Novus Biologicals) in multiple tissues, including peripheral blood, spleen, liver, lung, and bone marrow. Presence of engrafted EngTreg cells as assessed as %GFP+ of Live, hCD45+, hCD4+ gated cells, or %hCD25+/hCD127− of Live, hCD45+, hCD4+ gated cells from processed tissue samples on each indicated time point or at study endpoint. The total number of cells in each analyzed sample was determined using flow cytometry particles for absolute cell counting (Spherotech).

CAR-T cytotoxicity assay

CAR-T killing assays were performed as previously described.45 K562 CD19+ and control target cell lines consist of K562 cells (ATCC) stably transduced with LV carrying either MND.CD19.T2A.GFP (CD19+ K562) or MND.BCMA.T2A.BFP (irrelevant antigen control; CD19- K562). In brief, equal numbers of CD19+ and CD19− K562 target cells (T) were co-cultured with control or CD19-CAR-T cells (E) (generated either by HDR or LV) at various E:T ratios. At 48 h, cytotoxicity was calculated as percent specific lysis: 100% X (1 – (%CD19+/%CD19− at noted E:T)/(%CD19+/CD19− at 0:1 E:T)) by flow cytometry.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. For replicated datasets, significance was determined based on unpaired t test or two-way ANOVA. Survival cure data from in vivo studies was analyzed using log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Simple linear regression analysis was performed for body weight and GvHD score data from in vivo studies. All statistical analyses were run using GraphPad Prism software version 9.2.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Haddock for assistance with editing the manuscript and Dr. Laura Smith for effective coordination of studies. We also thank the members of the Rawlings laboratory for helpful discussions and support. This work was supported by grants from the Helmsley Charitable Trust and GentiBio, Inc. (to D.J.R.), the Seattle Children's Research Institute (SCRI) Program for Cell and Gene Therapy (PCGT), the Children’s Guild Association Endowed Chair in Pediatric Immunology (to D.J.R.), and the Hansen Investigator in Pediatric Innovation Endowment (to D.J.R.).

Author contributions

D.J.R., A.M.S., P.J.C., and S.J.Y. conceptualized and designed the study. S.E.W., A.B., A.R., T.D., and P.J.C. generated and tested CISC LV constructs in human CD4+ T cells and cell lines. S.J.Y. and S.E.W. generated and characterized human CISC EngTreg in vitro. S.J.Y., C.J., and N.P.D. performed in vivo GvHD studies. L.-J.W., G.I.U., and S.J.Y. performed in vivo rapamycin dosing experiments. A.G. and P.J.C. generated TRAC editing constructs and generated and characterized CISC CAR-T cells. P.J.C., S.J.Y., K.S., and D.J.R. wrote the manuscript with assistance from additional co-authors. D.J.R. obtained funding and was responsible for the project.

Declaration of interests

D.J.R. is a scientific co-founder and Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) member of GentiBio, Inc., and scientific co-founder and SAB member of BeBiopharma, Inc. A.M.S. is a scientific co-founder and SAB member of GentiBio, Inc., and scientific co-founder and CEO of Umoja Biopharma. D.J.R. received past and current funding from GentiBio, Inc., for related work. D.J.R., A.M.S., P.J.C., and K.S. are inventors on patents describing methods for generating antigen-specific engineered regulatory T cells and/or use of the CISC platform. G.I.U. was a previous employee of Casebia Therapeutics and a current employee of GentiBio, Inc.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.04.021.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.June C.H., Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:64–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young R.M., Engel N.W., Uslu U., Wellhausen N., June C.H. Next-generation CAR T-cell therapies. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:1625–1633. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stadtmauer E.A., Fraietta J.A., Davis M.M., Cohen A.D., Weber K.L., Lancaster E., Mangan P.A., Kulikovskaya I., Gupta M., Chen F., et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science. 2020;367 doi: 10.1126/science.aba7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raffin C., Vo L.T., Bluestone J.A. Treg cell-based therapies: challenges and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:158–172. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira L.M.R., Muller Y.D., Bluestone J.A., Tang Q. Next-generation regulatory T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:749–769. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amini L., Greig J., Schmueck-Henneresse M., Volk H.D., Bézie S., Reinke P., Guillonneau C., Wagner D.L., Anegon I. Super-treg: toward a new era of adoptive Treg therapy enabled by genetic modifications. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.611638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontenot J.D., Gavin M.A., Rudensky A.Y. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honaker Y., Hubbard N., Xiang Y., Fisher L., Hagin D., Sommer K., Song Y., Yang S.J., Lopez C., Tappen T., et al. Gene editing to induce FOXP3 expression in human CD4(+) T cells leads to a stable regulatory phenotype and function. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay6422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang S.J., Singh A.K., Drow T., Tappen T., Honaker Y., Barahmand-Pour-Whitman F., Linsley P.S., Cerosaletti K., Mauk K., Xiang Y., et al. Pancreatic islet-specific engineered Tregs exhibit robust antigen-specific and bystander immune suppression in type 1 diabetes models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin J.X., Leonard W.J. The common cytokine receptor gamma chain family of cytokines. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018;10 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao X., Shores E.W., Hu-Li J., Anver M.R., Kelsall B.L., Russell S.M., Drago J., Noguchi M., Grinberg A., Bloom E.T., et al. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Immunity. 1995;2:223–238. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noguchi M., Yi H., Rosenblatt H.M., Filipovich A.H., Adelstein S., Modi W.S., McBride O.W., Leonard W.J. Interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain mutation results in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency in humans. Cell. 1993;73:147–157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90167-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao W., Lin J.X., Leonard W.J. Interleukin-2 at the crossroads of effector responses, tolerance, and immunotherapy. Immunity. 2013;38:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liston A., Gray D.H.D. Homeostatic control of regulatory T cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:154–165. doi: 10.1038/nri3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe C.E., Cooper J.D., Brusko T., Walker N.M., Smyth D.J., Bailey R., Bourget K., Plagnol V., Field S., Atkinson M., et al. Large-scale genetic fine mapping and genotype-phenotype associations implicate polymorphism in the IL2RA region in type 1 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1074–1082. doi: 10.1038/ng2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinen T., Kannan A.K., Levine A.G., Fan X., Klein U., Zheng Y., Gasteiger G., Feng Y., Fontenot J.D., Rudensky A.Y. An essential role for the IL-2 receptor in Treg cell function. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:1322–1333. doi: 10.1038/ni.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng G., Yu A., Malek T.R. T-cell tolerance and the multi-functional role of IL-2R signaling in T-regulatory cells. Immunol. Rev. 2011;241:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitra S., Leonard W.J. Biology of IL-2 and its therapeutic modulation: mechanisms and strategies. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018;103:643–655. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2RI0717-278R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sockolosky J.T., Trotta E., Parisi G., Picton L., Su L.L., Le A.C., Chhabra A., Silveria S.L., George B.M., King I.C., et al. Selective targeting of engineered T cells using orthogonal IL-2 cytokine-receptor complexes. Science. 2018;359:1037–1042. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q., Hresko M.E., Picton L.K., Su L., Hollander M.J., Nunez-Cruz S., Zhang Z., Assenmacher C.A., Sockolosky J.T., Garcia K.C., Milone M.C. A human orthogonal IL-2 and IL-2Rbeta system enhances CAR T cell expansion and antitumor activity in a murine model of leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abg6986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aspuria P.J., Vivona S., Bauer M., Semana M., Ratti N., McCauley S., Riener R., de Waal Malefyt R., Rokkam D., Emmerich J., et al. An orthogonal IL-2 and IL-2Rbeta system drives persistence and activation of CAR T cells and clearance of bulky lymphoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13:eabg7565. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abg7565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirai T., Ramos T.L., Lin P.Y., Simonetta F., Su L.L., Picton L.K., Baker J., Lin J.X., Li P., Seo K., et al. Selective expansion of regulatory T cells using an orthogonal IL-2/IL-2 receptor system facilitates transplantation tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI139991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes Ramos T., Bolivar-Wagers S., Jin S., Thangavelu G., Simonetta F., Lin P.Y., Hirai T., Saha A., Koehn B.H., Su L.L., et al. Prevention of acute GVHD disease using an orthogonal IL-2/IL-2Rbeta system to selectively expand regulatory T-cells in vivo. Blood. 2022;141:1337–1352. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022018440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyman O., Kovar M., Rubinstein M.P., Surh C.D., Sprent J. Selective stimulation of T cell subsets with antibody-cytokine immune complexes. Science. 2006;311:1924–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1122927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spangler J.B., Trotta E., Tomala J., Peck A., Young T.A., Savvides C.S., Silveria S., Votavova P., Salafsky J., Pande V.S., et al. Engineering a single-agent cytokine/antibody fusion that selectively expands regulatory T cells for autoimmune disease therapy. J. Immunol. 2018;201:2094–2106. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khoryati L., Pham M.N., Sherve M., Kumari S., Cook K., Pearson J., Bogdani M., Campbell D.J., Gavin M.A. An IL-2 mutein engineered to promote expansion of regulatory T cells arrests ongoing autoimmunity in mice. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aba5264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson L.B., Bell C.J.M., Howlett S.K., Pekalski M.L., Brady K., Hinton H., Sauter D., Todd J.A., Umana P., Ast O., et al. A long-lived IL-2 mutein that selectively activates and expands regulatory T cells as a therapy for autoimmune disease. J. Autoimmun. 2018;95:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayle J.H., Grimley J.S., Stankunas K., Gestwicki J.E., Wandless T.J., Crabtree G.R. Rapamycin analogs with differential binding specificity permit orthogonal control of protein activity. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogawa K., Kawahara M., Nagamune T. Construction of unnatural heterodimeric receptors based on IL-2 and IL-6 receptor subunits. Biotechnol. Prog. 2013;29:1512–1518. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halene S., Wang L., Cooper R.M., Bockstoce D.C., Robbins P.B., Kohn D.B. Improved expression in hematopoietic and lymphoid cells in mice after transplantation of bone marrow transduced with a modified retroviral vector. Blood. 1999;94:3349–3357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malek T.R., Castro I. Interleukin-2 receptor signaling: at the interface between tolerance and immunity. Immunity. 2010;33:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hay N., Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volkó J., Kenesei Á., Zhang M., Várnai P., Mocsár G., Petrus M.N., Jambrovics K., Balajthy Z., Müller G., Bodnár A., et al. IL-2 receptors preassemble and signal in the ER/Golgi causing resistance to antiproliferative anti-IL-2Ralpha therapies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:21120–21130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901382116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tran D.Q., Andersson J., Wang R., Ramsey H., Unutmaz D., Shevach E.M. GARP (LRRC32) is essential for the surface expression of latent TGF-beta on platelets and activated FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13445–13450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King M.A., Covassin L., Brehm M.A., Racki W., Pearson T., Leif J., Laning J., Fodor W., Foreman O., Burzenski L., et al. Human peripheral blood leucocyte non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain gene mouse model of xenogeneic graft-versus-host-like disease and the role of host major histocompatibility complex. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009;157:104–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lord J.D., McIntosh B.C., Greenberg P.D., Nelson B.H. The IL-2 receptor promotes lymphocyte proliferation and induction of the c-myc, bcl-2, and bcl-x genes through the trans-activation domain of Stat5. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2533–2541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blazar B.R., Taylor P.A., Snover D.C., Sehgal S.N., Vallera D.A. Murine recipients of fully mismatched donor marrow are protected from lethal graft-versus-host disease by the in vivo administration of rapamycin but develop an autoimmune-like syndrome. J. Immunol. 1993;151:5726–5741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eyquem J., Mansilla-Soto J., Giavridis T., van der Stegen S.J.C., Hamieh M., Cunanan K.M., Odak A., Gönen M., Sadelain M. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature. 2017;543:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sogo T., Kawahara M., Ueda H., Otsu M., Onodera M., Nakauchi H., Nagamune T. T cell growth control using hapten-specific antibody/interleukin-2 receptor chimera. Cytokine. 2009;46:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sogo T., Kawahara M., Tsumoto K., Kumagai I., Ueda H., Nagamune T. Selective expansion of genetically modified T cells using an antibody/interleukin-2 receptor chimera. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008;337:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacDonald A.S., RAPAMUNE Global Study Group A worldwide, phase III, randomized, controlled, safety and efficacy study of a sirolimus/cyclosporine regimen for prevention of acute rejection in recipients of primary mismatched renal allografts. Transplantation. 2001;71:271–280. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200101270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dwyer C.J., Bayer A.L., Fotino C., Yu L., Cabello-Kindelan C., Ward N.C., Toomer K.H., Chen Z., Malek T.R. Altered homeostasis and development of regulatory T cell subsets represent an IL-2R-dependent risk for diabetes in NOD mice. Sci. Signal. 2017;10 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aam9563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burchill M.A., Yang J., Vogtenhuber C., Blazar B.R., Farrar M.A. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren J., Liu X., Fang C., Jiang S., June C.H., Zhao Y. Multiplex genome editing to generate universal CAR T cells resistant to PD1 inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:2255–2266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]