Video

Case showing a complete intraperitoneal maldeployment of a lumen-apposing metal stent during EUS-guided gastro-entero-anastomosis for malignant gastric outlet obstruction, which was rescued through a retrieval with peritoneoscopy through natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery.

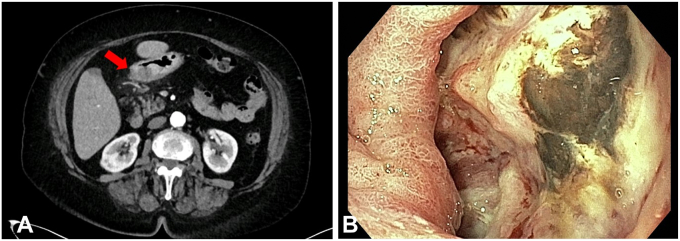

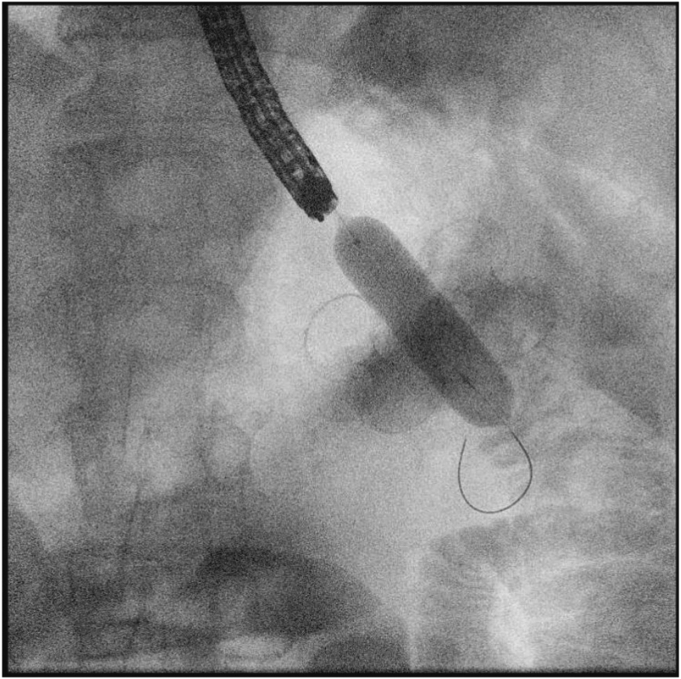

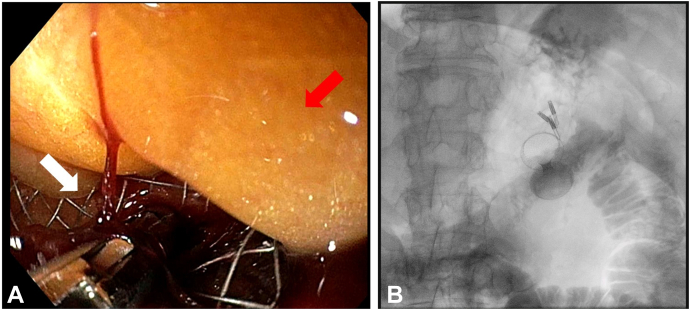

A 75-year-old female patient developed nausea and vomiting because of gastric outlet obstruction consequent to a duodenal malignancy infiltrating the antrum-duodenal wall and causing stomach enlargement (Fig. 1A). Moreover, she was considered unfit for surgery because of her performance status and severe cardiomyopathy. The gastroscopy showed duodenal neoplastic tissue occluding the pylorus (tissue was acquired with histological confirmation) (Fig. 1B). After a multidisciplinary board discussion, including an evaluation of internal protocols, we discussed the possibility of performing an alternative and off-label endoscopic procedure, an EUS-guided gastroenteroanastomosis (EUS-GEA), rather than duodenal stenting, with the patient and her family. After the meeting, the patient was aware of technical aspects, risks, benefits, and outcomes of both endoscopic procedures (duodenal stenting and EUS-GEA),1, 2, 3, 4 and she decided to undergo EUS-GEA. Therefore, we scheduled an EUS-GEA to resolve the gastric obstruction. EUS-GEA was performed using the single-balloon and freehand technique with deployment of a lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS). Prophylactic antibiotics with piperacillin/tazobactam were administered, and carbon dioxide (CO2) was used during the procedure because it is safer and more easily absorbable than air. The endoscopic balloon was placed beyond the occluded side of duodenum, and the endoscopist identified the desired intestinal loop with the instillation of contrast, saline, and methylene blue. The LAMS was going to be placed from the stomach into the identified loop through the Hot AXIOS delivery system (20 × 10 mm; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Mass, USA), but a double adverse event suddenly occurred. First, the first flange of the LAMS was deployed out of the jejunum, and after that the second flange was deployed into the peritoneal cavity. In that moment, we immediately had to decide whether to refer the patient to surgery or keep performing the procedure with endoscopic retrieval of the LAMS. Considering the use of CO2 and the patient’s condition, we decided to achieve the EUS-GEA with a second but successful attempt. The second LAMS (20 × 10 mm, Hot AXIOS; Boston Scientific) was releasing with the same technique, but this time we focused on having a more comfortable and stable position during the fistula creation. We successively moved to manage the retrieval of the intra-abdominal LAMS using the natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) technique.5 Therefore, we first identified the iatrogenic hole in the gastric wall with insertion of a guidewire through it, and then a dilation of the gastric wall defect to 18 mm of diameter was performed (Fig. 2), permitting us to cross it and perform a transgastric peritoneoscopy with the retrieval of the LAMS across the gastric defect by grasping it using a foreign body forceps (Fig. 3; Video 1, available online at www.videogie.org). The iatrogenic gastric defect was then closed with 3 metallic clips, and no extraluminal diffusion of contrast was seen at the fluoroscopic view. After 12 hours, the patient’s clinical status and laboratory tests were favorable, and her CT scan with oral contrast showed regular flow through the GEA with no extraluminal diffusion (Fig. 4) and an asymptomatic low amount of CO2, which was reabsorbed in 24 hours. Moreover, we closely talked to our infectious disease consultant, so we administered antibiotic therapy with quinolone (ciprofloxacin) and metronidazole for 5 days. The patient started a liquid diet after 24 hours and was discharged after another 48 hours of observation with a soft-solid diet. At our last follow-up call (4 months after the procedure), she was undergoing systemic chemotherapy and feeding with a soft-solid diet. Moreover, she did not complain about any late adverse event related to EUS-GEA. Currently, few reports discuss the use of NOTES as rescue therapy after LAMS maldeployment,6 and to our knowledge, no reports discuss the application of NOTES for accessing the peritoneal space and retrieving a maldeployed LAMS.

Figure 1.

A, CT scan showing malignant infiltration of the antrum. B, Endoscopic view of the neoplastic tissue.

Figure 2.

Radiologic view of balloon dilation of the gastric wall defect to achieve peritoneal access.

Figure 3.

A, Endoscopic view of the intraperitoneal LAMS rescue. The white arrow indicates the LAMS, and the red arrow indicates the peritoneal tissue. B, Radiologic view after EUS-guided gastroenteroanastomosis and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery showing normal placement of the LAMS and the 3 metallic clips applied to close the gastric defect. LAMS, Lumen-apposing metal stent.

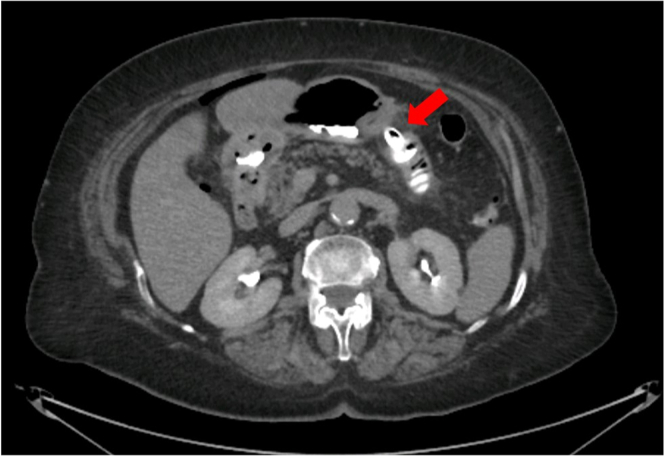

Figure 4.

CT scan with oral contrast showing regular flow into the jejunal loop through the lumen-apposing metal stent (red arrow).

Disclosure

The authors did not disclose any financial relationships.

Funding

This work was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente 2023.

Informed Consent

Dr Tarantino acts as guarantor of the article.

Supplementary data

Case showing a complete intraperitoneal maldeployment of a lumen-apposing metal stent during EUS-guided gastro-entero-anastomosis for malignant gastric outlet obstruction, which was rescued through a retrieval with peritoneoscopy through natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery.

References

- 1.Itoi T., Ishii K., Ikeuchi N., et al. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided double-balloon-occluded gastrojejunostomy bypass (EPASS) for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Gut. 2016;65:193–195. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyberg A., Kumta N., Karia K., Zerbo S., Sharaiha R.Z., Kahaleh M. EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy after failed enteral stenting. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1011–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ge P.S., Young J.Y., Dong W., Thompson C.C. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy versus enteral stent placement for palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3404–3411. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-06636-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan S.M., Dhir V., Chan Y.Y.Y., et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided balloon-occluded gastrojejunostomy bypass, duodenal stent or laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy for unresectable malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Dig Endosc. 2023;35:512–519. doi: 10.1111/den.14472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ASGE; SAGES. ASGE/SAGES Working Group on Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery White Paper October 2005. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez-Ocana R., Penas-Herrero I., Gil-Simon P., de la Serna-Higuera C., Perez-Miranda M. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery salvage of direct EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy. VideoGIE. 2017;2:346–348. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Case showing a complete intraperitoneal maldeployment of a lumen-apposing metal stent during EUS-guided gastro-entero-anastomosis for malignant gastric outlet obstruction, which was rescued through a retrieval with peritoneoscopy through natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery.

Case showing a complete intraperitoneal maldeployment of a lumen-apposing metal stent during EUS-guided gastro-entero-anastomosis for malignant gastric outlet obstruction, which was rescued through a retrieval with peritoneoscopy through natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery.