Abstract

Background

With a complex etiology and chronic, disabling evolution, schizophrenia continues to represent a challenge for patients, clinicians, and researchers alike. Recent emphasis in research on finding practical blood-based biomarkers for diagnosis improvement, disease development prediction, and therapeutic response monitoring in schizophrenia, led to studies aiming at elucidating a connection between stress and inflammation markers.

Methods

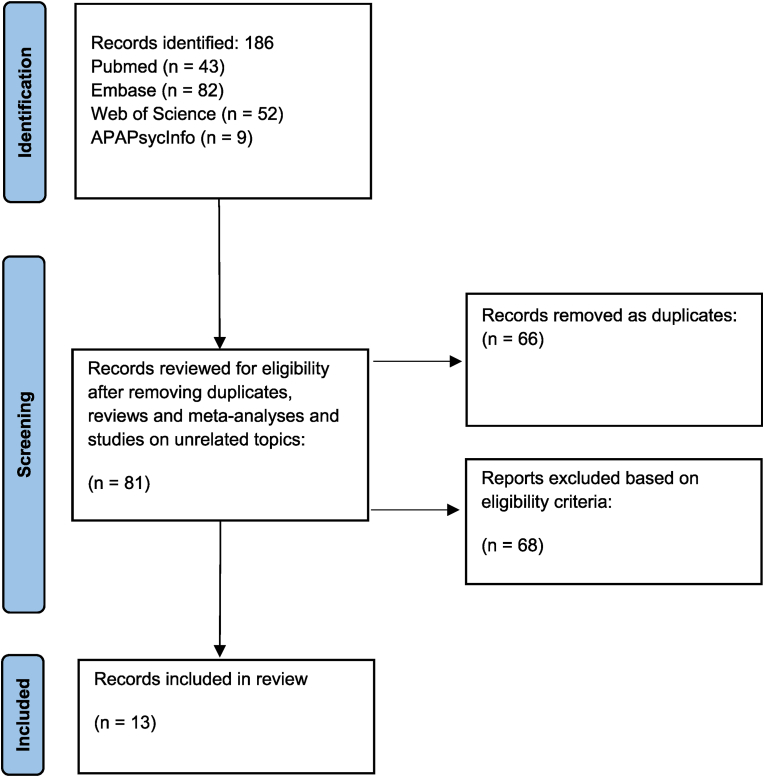

We set here to explore recent literature aiming to understand the connection between cytokines and cortisol level changes in individuals with schizophrenia and their potential relevance as markers of clinical improvement under treatment. A search was completed in Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and APAPsycInfo databases with search terms: (cytokines) AND (cortisol) AND (schizophrenia). This provided 43 results from Pubmed, 82 results from Embase, 52 results from Web of Science, and 9 results from APA PsycInfo. After removing articles not fitting the criteria, 13 articles were selected.

Results

While all studies included assess cortisol levels in individuals with schizophrenia, most of them included a healthy control group for comparisons there is diversity in the inflammation markers assessed – the most frequent being the IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α. Eleven of the 13 studies compare stress and inflammatory markers in individuals with schizophrenia to healthy controls, one study compares two subgroups of patients with schizophrenia, and one study compares pre- and post-measures in the same group of individuals with schizophrenia.

Conclusions

The focus of the studies within the topic is diverse. Many of the selected studies found correlations between cortisol and inflammation markers, however, the direction of correlation and inflammatory markers included differed. A variety of mechanisms behind cortisol and immunological changes associated with schizophrenia were considered. Evidence was found in these studies to suggest that biological immune and stress markers may be associated with clinical improvement in participants with schizophrenia, however, the exact mechanisms remain to be determined.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Stress, Cortisol, Inflammation, Cytokines

Highlights

-

•

Recent emphasis in research on finding practical blood-based biomarkers in schizophrenia supports the need for studies aiming at elucidating a connection between stress and inflammation markers.

-

•

The interplay of cytokine and cortisol changes in individuals with schizophrenia and their potential relevance as markers of clinical improvement under treatment requires more rigorous explorations.

-

•

There is evidence to suggest that biological immune and stress markers may be associated with clinical improvement in participants with schizophrenia, however, the exact mechanisms explaining it remain to be determined.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric disorder associated with an average of 14.5 potential years of life lost [1,2]. Given its heterogeneous presentation, the treatment of schizophrenia is complex, as antipsychotic medications effectively address positive symptoms but negative symptoms remain elusive to all approaches [1,3]. As a result, there has been a recent emphasis in research on finding practical blood-based biomarkers for diagnosis improvement, disease development prediction, and therapeutic response monitoring [2,4].

Among the myriad of factors discussed in the literature, inflammation stands out as an important factor in schizophrenia pathophysiology [5]. Stress has also been strongly highlighted as an important etiological factor, given its ability to modify the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response [6], with activating effect on the cytokines-secreting microglia (Perry, 2007). In healthy individuals, the corticotrophin-releasing factor secreted by the hypothalamus in response to stress binds receptors in the anterior pituitary gland lobe to induce adrenocorticotropic hormone release into the systemic circulation [7]. The adrenocorticotropic hormone, in turn, targets the adrenal cortex to secrete cortisol, which regulates physiological changes throughout the body [7]. Cortisol exhibits powerful anti-inflammatory effects as it can induce apoptosis of immune cells and regulate multiple pro-inflammatory genes encoding cytokines, chemokines, and inflammatory enzymes [8]. Through its effects on the metabolic regulation of glucose utilization and ATP production, cortisol can also be seen as an important modulator of emotion and cognition, key determinants of health from a mental health perspective [9]. The neural-diathesis stress model of schizophrenia hypothesizes that dysregulation of the HPA axis contributes to schizophrenia development [10], with numerous revisions suggesting the inclusion of inflammation in this equation [[11], [12], [13]].

Even though patients with chronic schizophrenia have an autonomic arousal response and subjective self-report of stress comparable to healthy individuals, numerous studies report that they also present with attenuated cortisol levels in response to laboratory-induced psychosocial stress [14,15]. Although there is substantial evidence to suggest HPA axis dysfunction in schizophrenia, up-to-date research results are far from elucidating the exact mechanism – especially in regards to the complex interaction with the immune system. The role of the immune system in the pathoaetiology of mental illness has become increasingly recognized [16]. Activation of microglia – the primary immune cells of the central nervous system, by environmental triggers, leads to the release of pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines [12]. In a healthy system, microglia, in an initial state of activation, have been shown to release pro-inflammatory compounds, including NO, IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, and glutamate. The subsequent activation state, that follows naturally, leads to the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10, IGF-1, TGF-B, and various neurotrophic factors. Evidence shows that both activation pathways are required for an appropriate immune response [17]. It's been suggested that dominance of the initial activation state leads to over-expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species that in turn lead to synaptic loss and neuronal death [18]. Microglial excessive or insufficient activity may have an important role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia as it is involved in the early neuronal development and survival, and particularly in the synaptic pruning, [12,19]. Reductions in microglial activity during neurodevelopment may lead to reduced synaptic pruning, and sustained deficits in synaptic connectivity [20], while excessive microglial activity later in life has been linked to synaptic loss and cognitive decline [21]. In animal models, pre-and post-natal infection and stress activate microglia in regions implicated in schizophrenia in humans: amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus acumbens, and prefrontal cortex. The glucocorticoids released by the HPA axis in response to stress target microglia due to their high level of glucocorticoid receptor expression [22]. Animal models have also shown that glucocorticoid receptor activation of microglia is necessary for the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines genes [23]. Interestingly, administration of glucocorticoids prior to an inflammatory trigger has been shown to have pro-inflammatory effects, whereas glucocorticoid administration subsequent to it has anti-inflammatory effects [24]. Stress-induced glucocorticoid release will then increase the neuronal release of glutamate, leading to neuronal loss [25].

Inflammation has in turn been found to have effects on the HPA axis and is considered to be a contributing factor to schizophrenia pathophysiology [6,26]. Inflammatory markers activate the HPA axis and the released cortisol will then act in an anti-inflammatory manner, suppressing particular cytokines involved in the inflammation, thus acting in a feedback loop system [27]. Important modulators of inflammation, cytokines coordinate the adaptive and innate immune system divisions by binding receptors on cells, having pro- or anti-inflammatory actions [1]. It is more and more accepted now that the immune system plays a role in facilitating the resolution of the biochemical and cellular events created by stress, ensuring that the signaling function of cytokines returns to equilibrium in order to correctly respond to new signals [16]. Resolution of mental stress may also form immunological memory to make future coping mechanisms more efficient, thus further emphasizing the connections between stress and the immune system [28]. Although various mechanisms have been suggested to support connections between inflammation and stress in schizophrenia, this aspect of the research has been pitted against heterogeneous findings [1]. Much evidence has been accumulating over the years on the impact inflammation has on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, and separately on the impact stress, but less numerous efforts are cited to connect the two. Our scoping review will explore recent literature aiming to highlight a connection between inflammatory cytokines and cortisol in individuals with schizophrenia and their potential relevance as markers of clinical improvement under treatment.

2. Methods

A systematic search was completed in Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, and APAPsycInfo databases with search terms: (cytokines) AND (cortisol) AND (schizophrenia). This provided 43 results from Pubmed, 82 results from Embase, 52 from the Web of Science, and 9 results from APA PsycInfo. After reading abstracts and removing duplicates and articles not fitting the criteria, 13 articles reporting on studies where cortisol and cytokines were evaluated in individuals with schizophrenia were selected (PRISMA diagram, Fig. 1). Our search limited the results to peer-reviewed clinical studies where individuals with schizophrenia were included in either an intervention or control group. We excluded conference abstracts, reviews, meta-analyses, or commentaries.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram.

3. Results

All studies included in this scoping review assessed cortisol levels, however, there is diversity in the cytokines assessed – the most frequent being the IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-8, as well as TNF-α. Eleven of the 13 studies (Table 1) compare stress and inflammatory markers in individuals with schizophrenia to healthy controls, one study ([29] compares two subgroups of patients with schizophrenia, and one study [30] compares pre- and post-measures in the same group of individuals with schizophrenia. Three of the 11 studies using control groups also compare results to groups other than healthy controls: patients with bipolar disorder [31], participants with ultra-high risk for psychosis [32,33], participants with first-episode psychosis as well as participants with ultra-high risk for psychosis [34].

Table 1.

Results.

| Article | Study population | Study protocol | Cytokines measured | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | n = 25 patients with SZ n = 25 controls |

Plasma cytokines and cortisol measured before, during, and after colectomy, hemicolectomy, and sigmoidectomy |

|

|

| [36] | n = 70 patients with SZ divided into two groups: Group A n = 35 received epidural anesthesia Group B n = 35 did not receive epidural anesthesia< n = 35 controls (Group C) |

Study investigated: whether epidural analgesia affects postoperative confusion in patients with SZ; -the relationship between cortisol or IL-6 and postoperative confusion |

|

|

| [37] | n = 78 patients with SZ n = 30 healthy controls |

Patients with SZ were randomly assigned to a 12-week treatment with 6 mg/day risperidone or 20 mg/day haloperidol, in a double-blind design. |

|

|

| [31] | n = 40 patients with SZ n = 20 patients with BP n = 40 healthy controls |

Study investigated the peripheral TLR activity in psychosis. Plasma was analyzed for cytokines, cortisol, and acute-phase proteins. |

|

|

| [38] | n = 34 participants with SZ n = 40 healthy controls |

Study investigated the contribution of the glucocorticoid-immune relationship to abnormal stress response in SZ. Two psychological stress tasks were used: PASAT (paced auditory serial addition task) MTPT (mirror-tracing persistence task) |

|

|

| [32,33] | n = 16 participants with chronic SZ n = 12 participants with UHR for psychosis n = 23 healthy controls |

Clinical and biochemical variables assessed for comparison between the 3 groups; Dexamethasone suppression test |

|

|

| [30] | n = 17 patients with SZ | Exercise protocol 3 times weekly for approx. 1 h for 3 months; Stress and inflammatory markers assessed before and 30, 60, and 90 days after protocol |

|

|

| [39] | n = 10 participants with SZ/SZA n = 10 healthy controls |

Study tested changes in immune, cortisol, kynurenine, and kynurenic acid responses to a psychosocial stressor in people with SZ and healthy controls. Psychosocial stressor used: Trier Social Stress Test |

|

|

| [34] | n = 25 participants with first psychosis episode, n = 16 participants with chronic SZ, n = 12 participants with Ultra High Risk, n = 23 healthy controls |

Study evaluated the Theory of Mind and Emotion Perception changes in a male cohort, in relation to immune and inflammatory markers. A dexamethasone suppression test was used. Clinical and biochemical variables were assessed for comparison between the groups. |

|

|

| [40] | n = 35 patients with SZ n = 17 healthy controls |

Study evaluated the main parameters of immunity and systemic inflammation in relation to brain damage markers and patterns of cognitive-affective in patients with SZ. |

|

|

| [41] | n = 33 participants with SZ n = 63 healthy controls |

Clinical and biochemical variables assessed for comparison between the 2 groups |

|

|

| [42] | n = 37 patients with SZ n = 35 healthy controls |

Clinical and biochemical variables assessed for comparison between the 2 groups |

|

|

| [29] | n = 121 patients with SZ and tardive dyskinesia (TD) n = 118 patients with SZ |

Oxidative stress factors, BDNF 1, inflammatory cytokines, prolactin, estrogen, and cortisol were measured in the two groups for comparison |

|

|

Abbreviations List: IFN: Interferon; IGF: insulin-like growth factor; IL: interleukin; PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale; SZ – Schizophrenia; SZA – Schizoaffective Disorder; TLR – Toll-Like Receptors; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; UHR – Ultra High Risk for psychosis.

The focus of the studies is diverse. Three of the studies – [41,42]; and Kuhoh et al. (2003) assess clinical changes in relation to inflammation and stress markers changes. Two other studies use the dexamethasone suppression test [32,33,34]. [38,39] use a psychosocial stressor while [30] use exercise to evaluate cortisol response and cytokines changes. All study samples involved adults, with various male-to-female ratios, with the exception of two studies done on a male cohort – [32,33,34].

Medication was discussed in all studies as a possible confounding factor, and one study focused on cortisol and inflammatory markers in relation to a typical versus an atypical antipsychotic medication [37].

Cortisol was evaluated in all studies and although the aim of the investigations was different, some trends could be distinguished. Following stress inductive conditions, cortisol was found significantly lower in individuals with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls in two studies - [36,39] while an increase in cortisol levels in association with an increase in IL-6 was found by Ref. [38]. Higher levels of cortisol were found in individuals with paranoid schizophrenia compared to individuals without cognitive impairment by Ref. [40] as well as [37]; where cortisol levels increased in individuals with schizophrenia after a 2-week antipsychotics wash-out period.Significant interactions between cortisol and cytokines were noted by Refs. [37,38,30,42]; and [35]. Significant interactions between cortisol and cytokines were found by Ref. [35]; where cortisol correlated with IL-6; [37] where the elevation of cortisol following the 2-week antipsychotics wash-out was correlated to an increase in IL-2 and IL-6 serum levels; [42]; where the cortisol x TNF-α x IL-8 was seen as indicative of risk factor for schizophrenia and by Ref. [38] where cortisol was positively correlated with IL-6, indicative of an inability to downregulate inflammatory responses in schizophrenia.

4. Discussion

Each of the 13 studies included in this review highlighted a particular aspect of the complex interactions between the immune and inflammatory systems within the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. A wide range of protocol designs, sample sizes, and immune assays were used. Overall, the findings suggest a clear implication of a myriad of immune-endocrine factors contributing to the heterogeneous presentation in schizophrenia, where environmental factors add to the genetic vulnerability in unique ways.

It is well established that stress hormones play an important role in triggering the expression of vulnerability to chronic, severe mental illnesses, including schizophrenia [43]. A difference was found in how controls and individuals with schizophrenia responded to stress tasks in several of the studies [38,39], surgical conditions [35,36] as well as to exercise [44]. In line with previous human and animal studies, cortisol levels were consistently found to rise in healthy controls but in individuals with schizophrenia, lower levels were more frequently found, by comparison, while a cortisol increase in these individuals was associated with an increase in inflammatory cytokines, suggesting an inability to downregulate the inflammatory response.

From a psychological standpoint, it is considered that people with this severe mental condition have failed to cope with stress [45]. However, the immune-inflammatory mechanisms underlying a genetically and physiologically compromised system seem to create a particular repertoire of reactions that manifest as a mental disorder that is hard to cope with. Early life stress, for example, leads to neuro-endocrine-immune changes that give a certain vulnerability to psychiatric disorders later in life [46]. Consistent with the findings of [31] included in this review, studies on healthy adults exposed to stress show higher levels of plasma cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, and serum TNF-α [47]. A recent study reporting on early life stress in healthy adolescents found that their lymphocytes produce up to 5 times more inflammatory cytokines as well as increased hair cortisol levels and low plasma BDNF levels [48].

Many of the selected studies found correlations between cortisol and inflammation markers. However, the direction of correlation and inflammatory markers included differed. [38] found a positive correlation between cortisol and IL-6, [40] found an increase in cortisol, IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ, while [42] identified a significant interaction between cortisol, TNF-α and IL-8.

The studies considered made varied suggestions in regard to the mechanisms behind cortisol and immunological changes associated with schizophrenia. [39] considered the kynurenine pathway and, given that IL-6 increases occurred independently from kynurenine, hypothesized that other mechanisms were involved in immune activation. However, this study directly contradicted findings in a study by Ref. [49] where it was considered that reduced neurogenesis may be due to influences on the kynurenine pathway. Mondelli and her team suggested that the lower synaptic plasticity and suboptimal brain function are due to disturbed monoaminergic pathways, explaining this way the reduced treatment response. [30] suggested a gene silencing process through reduced gene transcription, impacting this way the disease progression. Next, [32,33,42] considered the role of microglia activation in releasing pro-inflammatory immune factors, causing abnormal neurogenesis. [38] discussed the role of glucocorticoids in suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine gene transcription through the NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa) pathway. Further, [32,33] described a protective role for IL-4 against psychosis, as higher levels of this cytokine were found in individuals with ultra-high risk for psychosis compared to healthy controls and individuals with chronic schizophrenia. In the same study, it was considered that both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system are activated given that TNF-a, an innate immunity factor, and IFN-y, an adaptive immune arm factor, are increased in individuals at risk for psychosis [32,33]. This article further proposes that increased pro-inflammatory cytokines are balanced by a decrease in cortisol to maintain homeostasis. In a previous study, [50] described associations between IL-10 and schizophrenia to be due to IL-10's protective effect against inflammation-mediated degeneration of dopaminergic neurons on substantia nigra in individuals with first-episode psychosis. Consistent with previous studies [16] it was also considered that anti- and pro-inflammatory factor mobilization may result in immune dysregulation and result in chronically activated macrophages and T-lymphocytes.

Inflammation is considered a contributing factor to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, expressed by changes in immunological markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and different interleukins [51,52]. In our selected publications, [39] found that IL-6 spiked in healthy controls prior to cortisol increases, but no response was seen in participants with schizophrenia. This contradicted [38] findings where a negative correlation between acute cortisol response and responding Il-6 changes occurred in healthy controls, with a positive correlation occurring in participants with schizophrenia.

In patients with schizophrenia, the presence of gene polymorphism of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-6, has been linked to high serum levels of these cytokines [53]. It was suggested that IL-1β, IL-6, and TGF-B (transforming growth factor) could be schizophrenia state markers since they were elevated in both the first-episode and relapse of the disease, but these markers were decreased after the antipsychotic treatment [54]; [6]). Consistent with this, [37] found that treatment with risperidone – an atypical antipsychotic significantly reduced cortisol levels, which was associated with levels of IL-2, and thus improved negative symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia. Previous studies have consistently shown that antipsychotics exert immunosuppressive effects on the production of cytokines [55,56], suggesting epigenetic changes. [30] also suggest that individuals with schizophrenia are vulnerable to epigenetic changes induced by exercise, as they found that gene transcriptional repression via acetylation may occur with exercise interventions, thus impacting inflammatory marker changes throughout treatment.

Some of the selected studies made correlations between inflammatory markers and the severity of psychosis: [37] found that an elevated cortisol level was associated with negative symptoms, while elevated levels of IL-2 were associated with positive symptoms; [42] found positive associations with cognitive dysfunction severity, cortisol, TNF-a, and IL-8; [41] found a positive correlation between IL-18/IL-18BP ratio and depressive symptoms; [29] found lower levels of TNF-α in individuals with schizophrenia and tardive dyskinesia compared to those without it; finally, IL-4 was positively correlated with social cognition, and basic emotional perception [34].

Limitations of the present review include a limited number of studies identified as a result of a stringent set of criteria. The wide range of protocol designs, sample sizes, and focus of the selected studies made generalizations difficult. However, a general trend of highlighting a dysregulated HPA–immune system interaction in individuals with schizophrenia as opposed to healthy controls could be identified.

Common limitations in the studies included in this review refer to small sample sizes and no consistency in the gender balancing of samples. Finally, a wide range of approaches in controlling for confounding variables like race, smoking, BMI, and diet was noted as these may affect the stress-inflammation link. Future studies should increase sample size and possibly adopt a longitudinal design in support of further elucidating the HPA-immunity interaction changes along the progression of schizophrenia.

5. Conclusions

The possible role played by stress and inflammation has been broadly studied in depressive disorder and heart pathology, as well as in sleep disturbances and metabolic diseases. However, in schizophrenia, these aspects have been understudied. Our search in 4 databases on the topic resulted in the selection of 13 publications that fit the criteria established to possibly pinpoint recent evidence of an HPA-immune system interaction in schizophrenia. All selected studies evaluated cortisol and inflammation markers, but with a different cytokines assessment profile.

Although evident correlations between inflammation and cortisol which may be disturbed in individuals with schizophrenia were highlighted, the wide variety of protocols, immunological assays, and sample sizes do not allow for generalization. There is evidence to suggest that biological immune and stress markers may be associated with clinical improvement in participants with schizophrenia, however, the exact mechanisms explaining it remains to be determined.

The main limitations of this review include small sample size and limited generalizability.

Additional longitudinal study designs are needed to further understand the relationship between cortisol, inflammatory markers, and schizophrenia. This may contribute to guiding early intervention strategies, and measures of psychosis improvement under treatment.

Funding

Providence Care Innovation Grant 2019: “Innovative pathways to impactful treatment of chronic schizophrenia: disrupting the status-quo moving toward biological-driven, combined pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic approaches to define markers of therapeutic improvement in cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis promoted recovery”.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Miller B.J., Goldsmith D. Evaluating the hypothesis that schizophrenia is an inflammatory disorder. Focus. 2020;18(4):391–401. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20200015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hjorthøj C., Stürup A.E., McGrath J.J., Nordentoft M. SA57. Life expectancy and years of potential life lost in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2017;43(suppl_1):S133–S134. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx023.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King D.A. European Neuropsychopharmacology; 1998. Drug Treatment of the Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai C., Scarr E., Udawela M., Everall I.P., Chen W., Dean B. Biomarkers in schizophrenia: a focus on blood-based diagnostics and theranostics. World J. Psychiatr. 2016;6(1):102. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müller N. Inflammation in schizophrenia: pathogenetic aspects and therapeutic considerations. Schizophr. Bull. 2018;44(5):973–982. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkovic M.N., Erjavec G.N., Štrac D.Š., Uzun S., Kozumplik O., Pivac N. Theranostic biomarkers for schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(4):733. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith S.C., Vale W. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006;8(4):383–395. doi: 10.31887/dcns.2006.8.4/ssmith. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell G., Lightman S. The human stress response. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019;15:525–534. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown E.S. Effects of glucocorticoids on mood, memory, and the hippocampus. Treatment and preventive therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1179:41–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker E.F., Diforio D. Schizophrenia: a neural diathesis-stress model. Psychol. Rev. 1997;104(4):667–685. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones S.R., Fernyhough C. A new look at the neural diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia: the primacy of social-evaluative and uncontrollable situations. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33(5):1171–1177. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howes O.D., McCutcheon R. Inflammation and the neural diathesis-stress hypothesis of schizophrenia: a reconceptualization. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7(2):e1024. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pruessner M., Cullen A.E., Aas M., Walker E.F. The neural diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia revisited: an update on recent findings considering illness stage and neurobiological and methodological complexities. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017;73:191–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner K., Liu A., Laplante D.P., Lupien S.J., Pruessner J.C., Ciampi A., Joober R., King S. Cortisol response to a psychosocial stressor in schizophrenia: blunted, delayed, or normal? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(6):859–868. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen L.M., Gispen-de Wied C.C., Kahn R.S. Selective impairments in the stress response in schizophrenic patients. Psychopharmacology. 2000;149(3):319–325. doi: 10.1007/s002130000381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz M., Raposo C. Protective autoimmunity: a unifying model for the immune network involved in CNS repair. Neuroscientist. 2014;20(4):343–358. doi: 10.1177/1073858413516799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colton C.A. Heterogeneity of microglial activation in the innate immune response in the brain. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol.: Offic. J. Soci. NeuroImmune Pharmacol. 2009;4(4):399–418. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherry J.D., Olschowka J.A., O'Banion M.K. Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad, and the inflamed. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deczkowska A., Amit I., Schwartz M. Microglial immune checkpoint mechanisms. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:779–786. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paolicelli R.C., Bolasco G., Pagani F., Maggi L., Scianni M., Panzanelli P., Giustetto M., Ferreira T.A., Guiducci E., Dumas L., Ragozzino D., Gross C.T. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2011;333(6048):1456–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong S., Beja-Glasser V.F., Nfonoyim B.M., Frouin A., Li S., Ramakrishnan S., Merry K.M., Shi Q., Rosenthal A., Barres B.A., Lemere C.A., Selkoe D.J., Stevens B. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer's mouse models. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2016;352(6286):712–716. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sierra A., Gottfried-Blackmore A., Milner T.A., McEwen B.S., Bulloch K. Steroid hormone receptor expression and function in microglia. Glia. 2008;56(6):659–674. doi: 10.1002/glia.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen S., Janicki-Deverts D., Doyle W.J., Miller G.E., Frank E., Rabin B.S., Turner R.B. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(16):5995–5999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118355109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank M.G., Watkins L.R., Maier S.F. The permissive role of glucocorticoids in neuroinflammatory priming: mechanisms and insights. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2015;22(4):300–305. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moghaddam B., Bolinao M.L., Stein-Behrens B., Sapolsky R. Glucocorticoids mediate the stress-induced extracellular accumulation of glutamate. Brain Res. 1994;655(1–2):251–254. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldsmith D.R., Rapaport M.H. Inflammation and negative symptoms of schizophrenia: implications for reward processing and motivational deficits. Front. Psychiatr. 2020;11:46. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolkow A., Aisbett B., Reynolds J.V., Ferguson S.A., Main L.C. Relationships between inflammatory cytokine and cortisol responses in firefighters exposed to simulated wildfire suppression work and sleep restriction. Physiol. Rep. 2015;3(11) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz M., London A. Yale University Press; 2015. Neuroimmunity: a New Science that Will Revolutionize How We Keep Our Brains Healthy and Young. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Q., Yuan F., Zhang S., Liu W., Miao Q., Zheng X.…Hou K. Disease Markers; 2022. Correlation of Blood Biochemical Markers with Tardive Dyskinesia in Schizophrenic Patients. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavratti C., Dorneles G.P., Pochmann D., Peres A., Bard A., De Lima Schipper L., Lago P.D., Wagner L.C., Elsner V.R. Exercise-induced modulation of histone H4 acetylation status and cytokines levels in patients with schizophrenia. Physiol. Behav. 2017;168:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKernan D.P., Dennison U., Gaszner G., Cryan J.F., Dinan T.G. Enhanced peripheral toll-like receptor responses in psychosis: further evidence of a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Transl. Psychiatry. 2011;1(8):e36. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.37. e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karanikas E., Ntouros E., Oikonomou D., Floros G., Griveas I., Garyfallos G. Evidence for hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal Axis and immune alterations at prodrome of psychosis in males. Psych. Investig. 2017;14(5):703. doi: 10.4306/pi.2017.14.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karanikas E., Manganaris S., Ntouros E., Floros G., Antoniadis D., Garyfallos G. Cytokines, cortisol, and IGF-1 in first-episode psychosis and ultra-high-risk males. Evidence for TNF-α, IFN-γ, ΤNF-β, IL-4 deviation. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2017;26:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ntouros E., Karanikas E., Floros G., Andreou C., Tsoura A., Garyfallos G., Bozikas V.P. Social cognition in the course of psychosis and its correlation with biomarkers in a male cohort. Cognit. Neuropsychiatry. 2018;23(2):103–115. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2018.1440201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudoh A., Sakai T., Ishihara H., Matsuki A. Plasma cytokine response to surgical stress in schizophrenic patients. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2001;125(1):89–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kudoh A., Takase H., Takahira Y., Katagai H., Takazawa T. Postoperative confusion in schizophrenic patients is affected by interleukin-6. J. Clin. Anesth. 2003;15(6):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X.Y., Zhou D.F., Cao L.Y., Wu G.Y., Shen Y.C. Cortisol and cytokines in chronic and treatment-resistant patients with schizophrenia: association with psychopathology and response to antipsychotics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(8):1532–1538. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiappelli J., Shi Q., Kodi P., Savransky A., Kochunov P., Rowland L.M., Nugent K.L., Hong L.E. Disrupted glucocorticoid—immune interactions during stress response in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glassman M.J., Wehring H.J., Pocivavsek A., Sullivan K.A., Rowland L.M., McMahon R.P., Chiappelli J., Liu F., Kelly D.L. Peripheral cortisol and inflammatory response to a psychosocial stressor in people with schizophrenia. J. Neuropsych. 2018;2(2) doi: 10.21767/2471-8548.10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ushakov V.L., Malashenkova I.K., Krynskiy S.A., Kartashov S.I., Orlov V.A., Malakhov D.G.…Kostyuk G.P. Basic cognitive architecture, systemic inflammation, and immune dysfunction in schizophrenia. Современные технологии в медицине. 2019;11(3):32–38. (eng)) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wedervang-Resell K., Friis S., Lonning V., Smelror R., Johannessen C.H., Reponen E.J., Lyngstad S.H., Lekva T., Aukrust P., Ueland T., Andreassen O.A., Agartz I., Myhre A.M. Increased interleukin 18 activity in adolescents with early-onset psychosis is associated with cortisol and depressive symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q., He H., Cao B., Gao R., Jiang L., Zhang X.Y., Dai J. Analysis of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia based on machine learning: interaction between psychological stress and immune system. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;760 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker E.F., Trotman H.D., Pearce B.D., Addington J., Cadenhead K.S., Cornblatt B.A., Heinssen R., Mathalon D.H., Perkins D.O., Seidman L.J., Tsuang M.T., Cannon T.D., McGlashan T.H., Woods S.W. Cortisol levels and risk for psychosis: initial findings from the North American prodrome longitudinal study. Biol. Psychiatr. 2013;74(6):410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavratti C., Dorneles G., Pochmann D., Peres A., Bard A., de Lima Schipper L., Dal Lago P., Wagner L.C., Elsner V.R. Exercise-induced modulation of histone H4 acetylation status and cytokines levels in patients with schizophrenia. Physiol. Behav. 2017;168:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahn R.S., Sommer I.E.C. The neurobiology and treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatr. 2015;20(1):84–97. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danese A., McEwen B.S. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age- related disease. Physiol. Behav. 2012;106(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carpenter L.L., Gawuga C.E., Tyrka A.R., Lee J.K., Anderson G.M., Price L.H. Association between plasma IL-6 response to acute stress and early-life adversity in healthy adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(13):2617–2623. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.do Prado C.H., Grassi-Oliveira R., Daruy-Filho L., Wieck A., Bauer M.E. Evidence for immune activation and resistance to glucocorticoids following childhood maltreatment in adolescents without psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(11):2272–2282. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mondelli V., Ciufolini S., Murri M.B., Bonaccorso S., Di Forti M., Giordano A., Marques T.R., Zunszain P.A., Morgan C., Murray R.M., Pariante C.M., Dazzan P. Cortisol and inflammatory biomarkers predict poor treatment response in first episode psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2015;41(5):1162–1170. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karanikas E., Griveas I., Ntouros E., Floros G., Garyfallos G. Evidence for increased immune mobilization in First Episode Psychosis compared with the prodromal stage in males. Psychiatr. Res. Neuroimaging. 2016;244:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suvisaari J., Loo B., Saarni S.E., Haukka J., Perälä J., Saarni S.I., Viertiö S., Partti K., Lönnqvist J., Jula A. Inflammation in psychotic disorders: a population-based study. Psychiatr. Res. Neuroimaging. 2011;189(2):305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh B., Chaudhuri T.K. Role of C-reactive protein in schizophrenia: an overview. Psychiatr. Res. Neuroimaging. 2014;216(2):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reale M., Costantini E., Greig N.H. Cytokine imbalance in schizophrenia. From research to clinic: potential implications for treatment. Front. Psychiatr. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.536257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller B.J., Buckley P.J., Seabolt W., Mellor A.L., Kirkpatrick B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol. Psychiatr. 2011;70(7):663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maes M., Meltzer H.Y., Bosmans E., Bergmans R., Vandoolaeghe E., Ranjan R., Desnyder R. Increased plasma concentrations of interleukin-6, soluble interleukin-6, soluble interleukin- 2 and transferrin receptor in major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1995;34(4):301–309. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00028-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song C. The interaction between cytokines and neurotransmitters in depression and stress: possible mechanism of antidepressant treatments. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2000;15(3):199–211. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1077(200004)15:3<199::AID-HUP163>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]