Highlights

-

•

Starches modification with rose polyphenols by multi-frequency power ultrasound (MFPU) was studied.

-

•

MFPU significantly promotes the formation of polyphenol-starch complexes.

-

•

MFPU optimized the digestive properties of polyphenol-starch complexes.

-

•

The viscosity of starches decreased after rose polyphenols addition and MFPU treatment.

Keywords: Starch, Edible rose polyphenols, Multi-frequency power ultrasound, In vitro

Abstract

As the main source of energy for human beings, starch is widely present in people's daily diet. However, due to its high content of rapidly digestive starch, it can cause a rapid increase in blood glucose after consumption, which is harmful to the human body. In the current study, the complexes made from edible rose polyphenols (ERPs) and three starches (corn, potato and pea) with different typical crystalline were prepared separately by multi-frequency power ultrasound (MFPU). The MFPU includes single-frequency modes of 40, 60 kHz and dual-frequency of 40 and 60 kHz in sequential and simultaneous mode. The results of the amount of complexes showed that ultrasound could promote the formation of polyphenol-starch complexes for all the three starches and the amount of ERPs in complexes depended on the ultrasonic parameters including treatment power, time and frequency. Infrared spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction indicated that ERPs with or without ultrasound could interact with the three starches through non-covalent bonds to form non-V-type complexes. Scanning electron microscopy showed that the shape of starches changed obviously from round/oval to angular and the surface of the starches were no longer smooth and appeared obvious pits, indicating that the ultrasonic field destroyed the structure of starches. In addition, compared to the control group, the in vitro digestibility study with 40/60 kHz sonication revealed that ultrasonic treatment greatly improved the digestive properties of the polyphenol-starch complexes by significantly increasing the content of resistant starch (20.31%, 17.27% and 14.98%) in the three starches. Furthermore, the viscosity properties of the three starches were all decreased after ERPs addition and the effect was enhanced by ultrasound both for single- and dual-frequency. In conclusion, ultrasound can be used as an effective method for preparing ERPs-starch complexes to develop high value-added products and low glycemic index (GI) foods.

1. Introduction

Starch, as a major food macronutrient is the main ingredient of almost staple food and the energy source for human beings [1]. It consists of amylose with α-1,4 glycosidic bonds and amylopectin with α-1,4 and α-1,6 glycosidic bonds. According to its digestion rate, starch has been classified into rapidly digestible, slowly digestible, and resistant starch [2]. The high content of rapidly digestible starch (RDS) in starch can cause a surge in blood sugar within a short period of time after consumption and long-term postprandial hyperglycemia may lead to chronic diseases such as mellitus diabetes, obesity and coronary heart disease [3]. Starch modification is a promising method to partly overcome the drawback by changing the physicochemical and functional properties of starch [4]. Many modification methods including physical, chemical, enzymatical and genetic have been reported to reduce the digestibility of their native forms [5]. However, each of these approaches has particular advantages and disadvantages.

Edible rose (Rosa rugosa), a member of the Rosacear family, has been cultivated in China for more than 2,000 years [6], [7]. Nowadays, rose has become dominant agricultural products in the world flower industry [8]. Rose is rich in essential oil, vitamins, minerals, and physiologically-active substances, such as anthocyanins, polyphenols, polysaccharides, and flavonoids [9]. In the rose industry of China, it is mainly used to extract essential oil or processed to rose cake and tea. Our previous studies have shown that the content of polyphenols in edible rose (Pingyin rose) is as high as 187.13 mg/g [10] and the polyphenols mainly consist of catechin, quercetin-3β-D-glucoside, phlorizin, procyanidin B2, gallicacid, and rutin [7]. Edible rose polyphenols (ERPs) have various physiological activities such as scavenging free radicals, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial, lowering blood lipids, and preventing heart disease [11]. More and more attention should be paid to the deep processing of edible rose.

Polyphenols can be applied to modify starch and change its digestive properties. The interaction between polyphenols and starches have been studied for many years [12], [13], [14]. The interaction leads to either the formation of inclusion complex in the form of amylose single left-hand helices [1], or the formation of non-inclusive complex with much weaker binding through hydrogen bonds [15]. The results of the interactions and the effects on the starch properties appear to be not only related to the starches and phenolic structure, but also affected by the preparation methods [16].

The traditional methods for preparing starch-polyphenol complexes are to incubate the dissolved starches and polyphenols at elevated temperatures in a solution of water, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and/or potassium hydroxide (KOH) [14], [17], [18]. However, high temperature during preparing process may result in oxidation and degradation of phenolic compounds. Thus, the researchers have been searching for an improved solution. Guo, Zhao, Chen, Chen and Zheng [16] investigated the characterization and digestion of lotus seed starch-green tea polyphenol complexes prepared under high hydrostatic pressure and found that green tea polyphenols were shown to be able to form V-type inclusion complex with amylose via high hydrostatic pressure. Zhao, Sun, Lin, Chen, Qin, Wu, Zheng and Guo [19] studied the effects of high-pressure homogenization (HPH) on the characterization and digestion behavior of lotus seed starch–green tea. The results indicated that HPH is a cost-effective technique for modified starch preparation and a new strategy for process intensification.

Ultrasonic technology, as a green, efficient and non-polluting processing method is increasingly used in the food industry [20]. It is one of the non-thermal technologies and is considered as an effective methods for the modification of starch granules in solution and gelatinized starch [21], [22]. Li, Tian, Fang, Chen and Hunag [23] described the ultrasonic method for preparation of maize starch-caffeic acid complex at different ultrasonic power levels (65, 130, 260 and 520 W). It has been found that ultrasound can facilitate to form starch–caffeic acid complexes, and the amount of caffeic acid in complexes depended on the ultrasound power levels. Besides, Zhao, Sun, Lin, Chen, Qin, Wu, Zheng and Guo [19] also evaluated the ultrasound and microwave synergistic interaction (UM) in the preparation of the lotus seed starch-green tea polyphenol complex. The results indicated that lower ultrasonic power of UM treatment favors a non-inclusive complex mainly formed through hydrogen bonds, whereas higher power contributes to the V-type inclusion complex, in the form of single, left-handed helices. Inspired by the previous research, we are wondering whether multi-frequency power ultrasound treatment could facilitate to the formation of inclusion complexes between edible rose polyphenols and starch.

To the best of our knowledge, most of the literatures focuses on the modification of starch granules and gelatinized starch by ultrasound, and only a few studies have investigated the influence of ultrasound on the formation of polyphenol-starch complex, especially for multi-frequency power ultrasound (MFPU). Compared to traditional single-frequency ultrasound, MFPU have more even sound field distribution, higher enhancement in cavitation yield and more resonances named “combination resonances” [22].

Therefore, in the current study, three starches with different crystalline including corn starch (A-type crystalline structure), potato starch (B-type) and pea starch (C-type) were selected to interact with edible rose polyphenols irradiated by multi-frequency power ultrasound at low temperature. The physicochemical properties and in vitro digestive properties of the complexes were investigated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Raw materials

The freeze-dried roses were provided by Shandong Huamei Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Pingyin, Jinan, Shandong). Corn (amylose content, 33%), potato (amylose content, 36%) and pea starch (amylose content, 43%) were purchased from Shandong Fuyang Biological Starch Ltd. All reagents such as absolute ethanol, Folin-Ciocalteu, sodium carbonate, and potassium bromide were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Experimental protocols

2.2.1. Extraction method of edible rose polyphenols

The edible rose polyphenols were extracted according to the our previous method of Xu, Feng, Tiliwa, Yan, Wei, Zhou, Ma, Wang and Chang [10]. The rose powder was accurately weighed and added to a concentration of 50% ethanol, with a ratio of rose to liquid of 1:45 (m/V). It was extracted with ultrasonic assistance (ultrasonic power 300 W, frequency 20 + 28 kHz in simultaneous working mode) for 30 min. After the reaction, the supernatant was centrifuged at 11,000 g for 10 min and used for subsequent experiments.

2.2.2. Preparation of ultrasound-assisted polyphenol-starch complexes

The suspensions of corn starch, potato starch or pea starch (10 g) with aforementioned supernatant of ERPs (10 mL) in 100 mL of distilled water and stirred well. The mixture was irradiated with multi-frequency power ultrasound (MFPU-1, Jiangsu University) at a power level of 0–500 W for 0–25 min. The ultrasonic frequency modes include single-frequency of 40, 60 kHz, and dual-frequency of 40 and 60 kHz in sequential mode and simultaneous mode.

Afterward, the ultrasound treated suspension was centrifuged at 2200 g for 15 min. Then the precipitates were transferred to a vacuum freeze-drying oven for 24 h at 50 °C. The dried powder was ground, placed in plastic bag and stored in a desiccator until further analysis.

2.3. Analytical methods

2.3.1. Determination of polyphenol content

The content of polyphenols in the complex was calculated according to the solvent (ethanol) extraction method, described by [24] with some modifications. Each preparation sample (0.1 g) was suspended in 5 mL of anhydrous ethanol and incubated in a constant temperature water bath (40 °C) for 30 min. The samples were cooled to room temperature, and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min. A 1.0 mL of the supernatant of each sample was then mixed with 1.0 mL of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent (diluted to one-tenth of the initial concentration with deionized water) and stored for 5 min, and then 1.0 mL of 6% w/v Na2CO3 solution was added. The mixture was swirled and put in a temperature bath at 40 °C for 20 min. Absorbance values were then measured at 765 nm using a UV spectrophotometer.

2.3.2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The SEM analysis was determined according to the method of Zheng, Tian, Kong, Yang, Yin, Xu, Chen, Liu and Ye [25] with minor modifications. The freeze-dried ERPs-starch samples were fixed on conductive gel, blown off the floating powder and then coated with a thin gold. The microstructure of ERPs-starch samples was observed using scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S-3400 N, Hitachi High Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

2.3.3. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

The Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of the freeze-dried ERPs-starch samples was determined by FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet IS50, Thermo Electron Corporation, USA) according to the method of Han, Bao, Wu and Ouyang [26] with minor modifications. The freeze-dried ERPs-starch (2 mg) and potassium bromide (200 mg) were mixed and ground in an agate mortar. The mixture was pressed into 1 ∼ 2 mm slice, and placed in an infrared spectrometer to scan the particles in the wavelength range of 4000–650 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and a number of 64 scans.

2.3.4. X-ray diffraction analysis (X-RD)

According to the method of Zhong, Ying, Dong-Hui, Qiang, Jun-Hu and Jin-Hua [27] with minor modifications, the freeze-dried ERPs-starch powder was placed in an X-ray reaction cavity (D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer, Bruker, Germany). The test was carried out at 40 kV tube pressure, 40 mA tube current, 2°/min steps, and 5-40° scattering range.

2.3.5. Determination of iodine binding capacity

The freeze-dried powders were dispersed in distilled water and prepared to 1% ERPs-starch solution. It was heated in a boiling water bath for 15 min and then cooled to room temperature. 1 mL of iodine solution (2% KI, 0.2% I2) was added to 50 mL of the solution. After standing at room temperature for 30 min, the maximum absorption wavelength (λmax) was analyzed by scanning at 500 ∼ 800 nm [28].

2.3.6. Determination of particle size

The starch was prepared into a 1% starch emulsion solution and stirred every 5 min. After 30 min, starch particle size was measured at 25 °C using a laser particle size tester (Litesizer 500, Anton Paar, Shanghai, China).

2.3.7. Determination of solubility and swelling power

The solubility and swelling power were determined as described by [29] with slight modifications. Briefly, accurately 0.2 g of ERPs-starch powder were dissolved in 10 mL distilled water. After vortexing for 20 s, the solution was heated in a water bath at 90℃ for 30 min with vortex mixing. The mixture was centrifuged at 1238 g for 20 min and the supernatant was poured into the aluminum box. The box with supernatant was heated at 105℃ until constant weight. The solubility and swelling degree were calculated according to the following formula.

| (1) |

| (2) |

where: A-- Mass of supernatant after constant weight (g);

W-- Mass of added starch (g);

P-- Mass of precipitate after centrifugation (g).

2.3.8. Determination of in vitro digestion characteristics

For the preparation of enzyme mixture, 6 g α-amylase (8000 U/g) were dissolved in 40 mL deionized water. After stirring magnetically for 30 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 2200 g for 20 min. The supernatant was removed and 1.4 mL of amyloglucosidase (100000 U/g) and 3.6 mL of distilled water were added. The solution obtained was store in a refrigerator at 4 °C.

The in vitro digestion of the ERPs-starch complex from ultrasonic treatment was determined according to the method of Nilay and Ilkay [30]. Briefly, 1 g ERPs-starch powder was placed in a 50 mL conical flask and several glass beads was added in the flask to simulate the peristaltic environment of the gastrointestinal tract. 20 mL sodium acetate buffer (210 mL 0.1 mol/L acetic acid solution with 790 mL 0.1 mol/L sodium acetate solution) was added. Afterwards, 5 mL enzyme mixture was added to the flask and hydrolyzed at 37 °C with 175 r/min. Then 0.5 mL supernatant was taken to 20 mL 70% ethanol solution at 20 min and 120 min, respectively. After centrifugation for 5 min (2000 g), 0.1 mL supernatant was taken to 3 mL glucose oxidase–peroxidase solution, and the absorbance was measured at 510 nm after water bath at 50 °C for 20 min. At the same time, 0.1 mL of 1 mg/mL glucose standard solution and 0.1 mL of distilled water were taken as standard and blank groups, respectively. According to the absorbance value, the contents of RDS, SDS and RS were calculated respectively. The calculation formula were as follows:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where: G20 - glucose content produced after 20 min of amylase hydrolysis (mg);

G120 - the glucose content produced after 120 min of amylase hydrolysis (mg);

FG - free glucose content in starch before enzyme hydrolysis treatment (mg);

TS - total starch content in the sample (mg).

2.3.9. Determination of rheological properties

The rheological properties were determined by referring to the method of Ashoka, Prisana, Worawikunya, Rungtiva and M.C. [31] with slight modifications. The samples were prepared by adding water to a 5% concentration of starch solution, heated in a water bath at 90 °C for 30 min and then cooled to room temperature. The rheological properties were measured by F-4 modular intelligent rheometer (Chopin Technologies, France) with a plate diameter of 40 mm and a test spacing of 0.5 mm. In the static rheological test, the shear rate was set at 0.1 ∼ 100 s−1 and the temperature was set at 25 ℃. The dynamic rheological measurement conditions were 25 °C, strain of 0.2 % and frequency of 0.1–––10 Hz.

2.3.10. Determination of textural properties

The method of Klara, Mathias, Corine, Hanna, S. and Maud [32] was used to determined the textural properties of the starches with slight modifications. XT plus texture analyzer (CT3, Brookfield Corporation, USA) with a flat-surface P75 cylinder probe (diameter 60 mm). The cylindrical gel sample (diameter 20 mm and height 15 mm) was subjected to the compression test at room temperature. The parameters were set with the sample deformation of 3.0 mm, test-speed of 1.0 mm/s and two cycle compression test.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried in triplicate and the data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using ORIGIN 9.0 (Origin-Lab Inc., Northampton, MA, USA) and SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results and analysis

3.1. Effect of MFPU conditions on polyphenol content

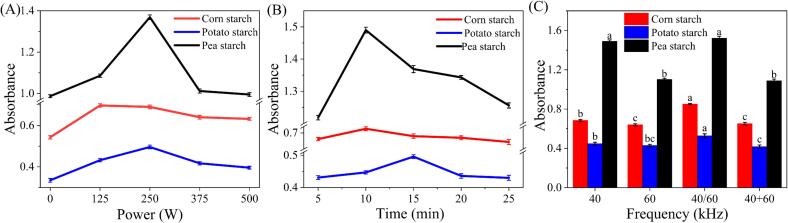

In order to determine whether ultrasonic treatment can promote the combination between ERPs and starch, the content of edible rose polyphenols was determined by the reduction reaction with the polyphenol hydroxyl group using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Apparently, the three different crystalline starches had the same trend after ultrasonic treatment. The absorbance of the obtained samples increased significantly with the increase of ultrasonic power and duration (Fig. 1 A, B). This is mainly due to the disintegration of swollen starch granules by ultrasonic treatment, which promotes the interaction between starch and small molecule ligands. The results are consistent with previous findings that ultrasonic treatment improves the dispersion of ligands in dextrinized starch suspensions [33]. However, when the ultrasonic power or duration were further increased, a sharp decrease in absorbance of the samples was detected. This is due to the rich hydroxyl groups on the outer surface of the starch chains, and the ERPs may interact with the starch chains through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic forces. Excessive ultrasonic treatment would break the weak hydrogen bonds between the starch chains and the polyphenols, leading to a decrease in absorbance. Additionally, more amylose molecules were released from the starch granules after ultrasonic treatment, and the amylose was easily depolymerized, which reduced the formation of starch-ligand complexes [23]. The results suggest that excessive sonication may have adverse effects.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ultrasonic power (A), duration (B), and frequency (C) on the relative amount of complexes.

From Fig. 1 C, it can be found that the binding rate between ERPs and starch under the single-frequency ultrasound of 40 kHz was higher than that under 60 kHz. This was probably because the low frequency ultrasonic wave has a larger wavelength and stronger penetrating ability than the high frequency, thus it can better destroy the molecular structure of starch and make it bind to rose polyphenol extracts at a higher rate. In addition, compared to the dual-frequency ultrasound of 40 and 60 kHz in simutaneous working mode, the binding rate of dual-frequency ultrasound in sequential working mode was higher. This was because the dual-frequency ultrasound in simutaneous working mode induces resonant fields in the response frame, as well as the superposition and reduction of two waves in some extended positions or stages, thus causing abrupt energy changes and reducing the energy emitted by the ultrasound device, which have a significant effect on the binding of starch and rose polyphenol extracts. It can be concluded from the results that proper ultrasonic parameters including power, duration and freqency would increase the binding rate of polyphenols and starch, while excessive ultrasound would be counterproductive and reduced the binding rate.

3.2. Analysis of scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The microscopic surface morphology of the three starches with different crystalline was observed using SEM, and the results are shown in Fig. 2. It can be found that the SEM images of the three starches have similar results. The three starch granules in different crystalline were large in volume, smooth in surface, and round or oval in shape before treatment. After the reaction of ERPs and starch, the starch granules remained the original shape, but some starch granules showed tiny lines and the integrity of the granules was destroyed (Fig. 2 A2). This indicates that ERPs could cause a certain degree of 'erosion' on starch, but the effect was limited.

Fig. 2.

SEM images of starches under different treatment conditions. A: Corn starch; B: Potato starch; C: Pea starch.

After ultrasonic treatment, the shape of starch granules changed obviously from round or oval to angular shape. Besides, the surface of the starch granules were no longer smooth and appeared obvious pits, indicating that the ultrasonic field destroyed the structure of starch granules. This situation can be attributed to the cavitation phenomenon. The bubbles near the starch surface caused by cavitation will collapse asymmetrically, resulting in a rapid microjet towards the starch surface, which led to different structural modifications of starches. Therefore, the implosion of cavitation bubbles will result in the fracture inside the starch [19]. This result would facilitate the entry of polyphenol molecules, allowing some of them to be embedded in the inner lumen of starch through non-covalent forms and increasing the binding rate of polyphenols to starch. Wei, Qi, Wang, Bi, Zou, Xu, Ren and Ma [34] found that ultrasonic treatment changes the starch surface morphology and increases the number and size of pores, and also promotes the penetration of oxidizing substances into the starch granules, increasing the chances of chemical reactions.

3.3. Analysis of fourier transform infrared spectral

The FTIR analysis is normally used to further investigate the interaction mechanism of ERPs with the three starches. The strong characteristic peak at around 3370 cm−1 represented O-H stretching vibration. The absorption peak at 2925 cm−1 is the stretching vibration peak of CH2 anti-symmetrical stretching, and the peak at 1650 cm−1 is the characteristic absorption peak of –OH of starch [23], [35]. These three peaks are the common absorption peaks of starch. As can be seen from Fig. 3, the FTIR spectrum of original starch and PS complex showed prominent absorption bands at 3370, 2925, 1650, 1047, 1022, 995 cm−1 (Fig. 3 A, B and C). Obviously, no new absorption peaks appeared in the infrared spectra of the three starches after ultrasonication or ERPs treatment, and the positions of the absorption peaks of each characteristic group did not change. The absorption peak areas at 1047, 1022 and 995 cm−1 represent the ordered crystalline region, amorphous region and helical structure of starch, respectively [23]. The intensity of the absorption peak at about 1047 and 1022 cm−1 of samples is changed after ultrasonic treatment, indicating that ultrasonic waves could disrupt the crystallinity of the starch granules.

Fig. 3.

FT-IR analysis of samples under different treatment conditions. A: Corn starch; B: Potato starch; C: Pea starch.

The value of 1047 /1022 cm−1 (Degree of order, DO) peak area ratio, which is called short-range order, represents the ordered crystalline region to the amorphous region in starch. 995 /1022 cm−1 (Degree of double helix, DD) represents the change of double helix structure inside the starch granule [36]. As can be seen from Table 1, the overall increase in DO value of starch after ultrasonic treatment can be observed. This may be due to the fact that ultrasound disrupts the starch molecular chains and the generated short chain molecular chains are connected by hydrogen bonds to form a new ordered structure [37]. The DD value of starch was significantly lower than that of PS, whereas the values of PS statistically increased under ultrasonic treatment in the single frequency of 40 kHz and dual frequency of 40/60 kHz. This may be due to the increase in the double helix structure as ultrasound disrupts the starch molecule and forms a new double helix structure [38].

Table 1.

DO and DD values of starches under different treatment conditions.

| Samples | conditions | DO | DD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn starch | Control | 0.76 ± 0.02c | 1.78 ± 0.03c |

| PS | 1.22 ± 0.09b | 2.18 ± 0.04b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 1.42 ± 0.02a | 2.40 ± 0.03a | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 1.44 ± 0.03a | 2.38 ± 0.01a | |

| Potato starch | Control | 0.55 ± 0.05c | 1.23 ± 0.02b |

| PS | 0.78 ± 0.01b | 1.28 ± 0.06b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 1.13 ± 0.02a | 2.09 ± 0.05a | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 1.10 ± 0.07a | 2.21 ± 0.16a | |

| Pea starch | Control | 0.55 ± 0.03c | 0.92 ± 0.04c |

| PS | 0.62 ± 0.04b | 1.05 ± 0.03b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 0.77 ± 0.02a | 1.27 ± 0.01a | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 0.75 ± 0.02a | 1.19 ± 0.07a |

3.4. X-ray diffraction analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique can be used to analyze the crystalline structure of starch. The spikes in the diffraction curve correspond to the crystalline structure of starch, and the type of crystalline structure of starch can be determined according to the position of the spikes (2θ) [39]. XRD can provide important information for the further investigation of the effect of ultrasonic synergistic interaction of rose polyphenol molecules on the crystalline structure of starch. As can be seen from the Fig. 4, the three starches with different crystalline structures have different diffraction peaks. Corn starch showed strong diffraction peaks at 2θ of 15°, 17°, 18° and 23°, which is a typical A-type crystalline structure. Potato starch and Pea starch showed the typical B-type crystalline structure with characteristic peaks at 17° and 22° and typical C-type patterns with well-defined diffraction peaks at 2θ of 15°, 17° and 23°, respectively. Starch interacts with phenolics through hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interaction and electrostatic and ionic interactions. These interactions drive starch and phenolics to form two types of complexes: V-type inclusion complex and non-V-type complex [4]. Starch showing peaks at diffraction peaks of 13.0 and 20.0°(2θ) indicates the existence of typical V-type crystalline structure [40]. From the XRD curves, it can not be found a diffraction characteristic peak near 2θ of 13° and 20° for the polyphenol-starch complex, indicating that a V-type inclusion complex was not formed for the PS and PS under ultrasonic treatment. Besides, as can be seen from Fig. 4, the number and intensity of the crystalline diffraction peaks of the corn and pea starch did not change significantly after the treatment with ultrasound or polyphenols, while the diffraction peak of potato starch at 22° disappeared after the treatment. It indicates that the water molecules migrated to the interior of potato starch particles and destroyed the original crystalline structure and the hydrogen bond structure within/between starch molecules during the treatment with ERPs and ultrasound. The chain segments of starch molecules and water molecules generate hydrogen bonding interactions and formed amorphous solution system through entanglement and aggregation [41].

Fig. 4.

X-ray diffraction patterns of samples under different treatment conditions. A: Corn starch; B: Potato starch; C: Pea starch.

3.5. Analysis of iodine binding capacity

Usually, the amylopectin has a very low iodine binding capacity due to its branched structure, whereas amylose has a high iodine affinity [3]. The effects of ultrasound and ERPs on the iodine blue values of starches are shown in Table 2. After the free reaction of starch with ERPs, the iodine blue value of starch showed a significant decrease and the combined treatment of starch with ultrasound and polyphenols intensified this trend. ERPs have a strong effect on the amylose content in starch, causing a large reduction in the amylose content. Ultrasound also has an effect on the amylose content, resulting in a significant reduction in the content. Besides, ultrasonic treatment under different frequency modes had no significant differences in the amylose content.

Table 2.

λmax, Iodine blue value and Iodine binding capacity of starches under different treatment conditions.

| Samples | Conditions | λmax/nm | Iodine blue value | Iodine binding capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn starch | Control | 592.36 ± 1.37a | 0.32 ± 0.02a | 1.37 ± 0.03a |

| PS | 556.92 ± 1.72b | 0.25 ± 0.01b | 0.96 ± 0.01b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 537.28 ± 1.14c | 0.11 ± 0.03c | 0.54 ± 0.01c | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 538.10 ± 1.58c | 0.11 ± 0.01c | 0.53 ± 0.00c | |

| Potato starch | Control | 605.11 ± 1.58a | 0.49 ± 0.01a | 1.55 ± 0.01a |

| PS | 593.42 ± 1.26b | 0.35 ± 0.01b | 1.33 ± 0.01b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 588.36 ± 0.8c | 0.31 ± 0.00c | 1.28 ± 0.03c | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 586.18 ± 1.01d | 0.30 ± 0.02c | 1.27 ± 0.01c | |

| Pea starch | Control | 622.67 ± 1.22a | 0.38 ± 0.01a | 1.77 ± 0.01a |

| PS | 612.40 ± 0.69b | 0.32 ± 0.00b | 1.66 ± 0.01b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 608.55 ± 1.25c | 0.28 ± 0.02c | 1.49 ± 0.03c | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 609.32 ± 0.19c | 0.30 ± 0.01c | 1.51 ± 0.01c |

The iodine binding power was obtained using the absorbance ratio of amylopectin-iodine complexes and amylose-iodine complexes, which can reflect the relative contents of the two complexes more intuitively. From Table 2, it can be found that the iodine binding power of starch showed a similar trend to the iodine blue value. Compared with the control, the iodine binding capacity of the three starches decreased by a maximum of 61.31%, 18.06% and 15.82% after the treatment. The experimental results showed that the interaction of rose polyphenols with the three starches separately with the aid of ultrasonic waves reduced the number of iodine ions entering the inner cavity of the amylose helix. It was presumably because the binding phenols entered the inner cavity of the amylose helix through the forces of van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, thus preventing the binding of iodine ions to the amylose [42]. Carmona-Garcia, Sanchez-Rivera, Méndez-Montealvo, Garza-Montoya and Bello-Pérez [43] had mentioned that starch and iodine can interact, where amylopectin interacts with iodine to form a purplish-red complex, while amylose interacts with iodine to form a blue complex, due to iodine ions entering the inner cavity of the hydrophobic helical structure of amylose and the two forming a blue complex via van der Waals forces.

3.6. Particle size analysis

The effect of ultrasound and rose polyphenols on the particle size of starch granules is shown specifically in Table 3. It can be found that the particle size of all three starches showed a trend of reduction after treatment. Compared to the control group, the particle size decreased by 16.4%, 30.97% and 21.98% after the reaction with polyphenols for corn, potato, and pea starch, respectively. This result was exacerbated by ultrasound with a maximum decrease of 56.4%, 42.8% and 53.4% after the combined treatment with ultrasound and ERPs. This is mainly the result of the erosion of polyphenols in combination with the mechanical and cavitation effect caused by ultrasound [44].

Table 3.

Particle size of starches under different treatment conditions.

| Sample | Control | PS | PS + MU-40 kHz | PS + MU-40/60 kHz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn starch | 18.90 ± 0.45a | 15.80 ± 0.81b | 9.10 ± 0.81c | 8.24 ± 0.37c |

| Potato starch | 27.15 ± 0.51a | 18.74 ± 0.27b | 15.67 ± 0.55c | 15.52 ± 0.58c |

| Pea starch | 27.88 ± 0.36a | 21.75 ± 0.15b | 16.64 ± 0.22c | 13.00 ± 0.80d |

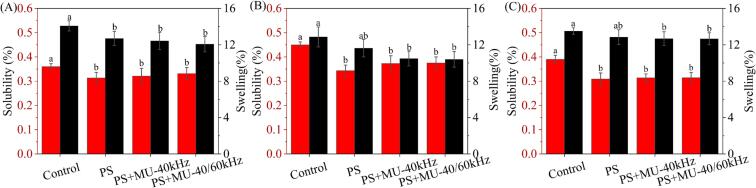

3.7. Solubility and swelling degree of expansion analysis

Husnain, Kashif, Haile, Qiufang and Xiaofeng [45] found that starch granules continued to absorb water with the increase of starch solution temperature, so that many amylose and some smaller amylopectin escape from the starch. The solubility of starch is closely related to the amylose and amylopectin during the swelling process. The swelling degree is an important indicator of the ability of starch to bind with water, which is closely related to various factors, such as the size of starch granules, the content of amylose, and the structure of starch molecules. As shown in Fig. 5, compared with the control, the solubility and swelling power of starch showed an overall decreasing trend with the addition of ERPs or ultrasonic treatment. The solubility of all three starches showed a decreasing trend after the addition of ERPs, which may be attributed to the reduced chance of escape of amylose and amylopectin from the starch by the addition of ERPs. Besides, the decrease of swelling power is mainly due to the oxidative cross-linking between starch and ERPs, which leads to the binding of more polymerized complexes with more water molecules, thus hindering the water absorption and swelling ability of starch [46]. Specific small molecules and the side chains of amylopectin can form stable complexes to achieve the effect of limiting the paste swelling of starch granules. After the addition of ERPs, the polyphenols and the side chains of starch formed stable complexes, thus limiting the paste swelling of starch granules.

Fig. 5.

Solubility and swelling of samples under different treatment conditions. A: Corn starch; B: Potato starch; C: Pea starch.

3.8. In vitro digestion characterization

Englyst, Kingman and Cummings [47] defined rapidly digestible starch (RDS) and slowly digestible starch (SDS) as starch that can be digested and broken down within 20 min and 20–120 min, respectively, whereas resistant starch (RS) as a starch that cannot be digested and broken down in the small intestine after 120 min. The in vitro digestive characteristics of starch can be measured to reflect the effect of starch on the rate of blood glucose elevation in humans and to determine the suitable population for the starch. The in vitro digestive characteristics of the three starches after ultrasound and ERPs treatment are shown in Fig. 6. Compared with the control, the RDS content of the three starches significantly decreased after the ERPs addition, whereas SDS and RS content significantly increased. Besides, the ultrasound-treated samples (PS + MU-40 kHz and PS + MU-40/60 kHz) showed higher content of both SDS and RS and lower content of RDS in comparison with PS. This may be due to the fact that sonication can change the molecular structure of starch and lead to the compact rearrangement of the double-helix structures in the starch granules, thereby reducing the hydrolysis rate of starch and making the hydrolysis of amylopectin slower [48]. In addition, the presence of polyphenols protected starch molecules from digestive enzymes, leading to an inhibitory effect on the digestion of polyphenol-starch complexes [49]. Therefore, the formation of polyphenol-starch complexes can resist enzymatic hydrolysis, reduce the rate of blood glucose elevation after human consumption, relieve the load on the relevant organs, and make the body healthier.

Fig. 6.

Changes in RDS, SDS, and RS contents under different treatment conditions. A: Corn starch; B: Potato starch; C: Pea starch.

3.9. Analysis of rheological properties

The rheological properties of starch reflect the disintegration of starch granules due to water absorption and swelling when starch pasting occurs, and the dissolution of amylose to form a three-dimensional network structure, which arises with the change of shear conditions and obtains different rheological parameters under shear force [36]. The dynamic rheological properties are shown in Fig. 7. The energy storage modulus G' and the loss modulus G“ are the energy stored in the elastic deformation and the energy lost in the viscous deformation of the starch paste during the deformation process, respectively. They can also reflect the magnitude of the gel strength formed by the starch paste [50]. The G' and G” values of all the three starch with or without ERPs increased with increasing the angular frequency. It can also be found that G' is higher than G“, indicating that the elastic properties dominate the viscous properties and the starch shows weak gel behavior [51]. Meanwhile, the addition of ERPs reduced the G' and G” of starch, indicating that the polyphenols reduced the junction between the amylose molecules in the starches and disrupted the gel structure of starches. This effect was remarkably exacerbated by ultrasound both for PS-MU-40 kHz and PS-MU-40/60 kHz.

Fig. 7.

Variation of rheological properties of samples under different treatment conditions. A: Corn starch; B: Potato starch; C: Pea starch.

It can be seen from Fig. 7 that the viscosity of the three starches with different crystalline dropped with an increase in the shear rate, indicating that the three starch pastes exhibited shear thinning and they were typical property for a pseudoplastic fluid. Compared with the control, the addition of ERPs with and without ultrasonic treatment remarkably lowered the viscosity of the three starches (Fig. A2, B2 and C2). Abdolkhalegh, Mohammadzadeh, Ali and Esmaeilzadeh [52] found that pea starch pastes exhibited shear thinning before and after the ultrasonic treatment, both of which were pseudoplastic fluids. The apparent viscosity of the sonicated pea starch paste was slightly greater than that of the original starch in the range of shear rate 0.1 ∼ 10 s−1, and the sonicated pea starch samples exhibited more intermolecular chain entanglements. This resulted in the enhancement of flow behavior restricting the movement of starch molecules and the starch paste was not easy to flow.

3.10. Analysis of textural properties

After the starch paste is cooled, the amylose interacts with each other through hydrogen bonding to form a gel with a certain hardness and elasticity of three-dimensional mesh structure. The gel texture of starch is related to the content of amylose, particle size and the structure of amylopectin, etc. For example, low amylose reduces the basic substances for the formation of three-dimensional reticulation structure, which leads to a lower degree of cross-linking between starch molecules during the gel formation process, and therefore the hardness and adhesive properties of the formed gel are reduced.

The textural properties of starch are related to the grid structure and strength of the starch macromolecules involved in the construction, and will reflect the quality of starch to a certain extent. Textural properties of the starches with different crystalline types after treatment are shown in Table 4. Compared with the control, the hardness of all three starches decreased after the addition of ERP, while the cohesiveness, elasticity, viscosity, chewiness and adhesion increased. This is mainly due to the fact that rose polyphenols are rich in carboxyl groups, which are combined with amylose through hydrogen bonding, weakening the intermolecular interaction between amylose and thus changing the gel texture [53]. Wen, Yao, Xu, Corke and Sui [54] found that the addition of purple potato combined with phenol will significantly reduce the hardness of starch and the maximum hardness can reduce by 71.04%, which is more conducive to the elderly, children or people with swallowing difficulties to eat.

Table 4.

Texture characteristics of starches under different treatment conditions.

| Sample | Conditions | Hardness | Cohesiveness | Elastic | Viscosity | Chewiness | Adhesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn starch | Control | 3.72 ± 0.16a | 38.55 ± 1.22d | 45.64 ± 2.21d | 47.12 ± 0.85c | 162.46 ± 2.59c | 79.66 ± 1.56d |

| PS | 3.46 ± 0.13b | 41.27 ± 0.96c | 49.49 ± 2.81c | 52.74 ± 2.53b | 171.30 ± 3.18b | 90.34 ± 1.89c | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 3.52 ± 0.15ab | 45.27 ± 1.35b | 54.39 ± 1.96b | 55.22 ± 2.62b | 191.56 ± 4.36a | 105.79 ± 2.22b | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 3.46 ± 0.11b | 57.16 ± 2.23a | 61.81 ± 2.53a | 61.69 ± 1.87a | 198.96 ± 5.12a | 131.00 ± 2.56a | |

| Potato starch | Control | 3.62 ± 0.13a | 46.12 ± 2.22b | 58.27 ± 3.52b | 59.96 ± 1.89b | 238.55 ± 1.28b | 145.24 ± 1.82c |

| PS | 3.46 ± 0.08ab | 54.04 ± 3.61a | 69.61 ± 2.53a | 66.17 ± 2.87a | 240.94 ± 2.54b | 159.43 ± 2.36b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 3.29 ± 0.05b | 56.32 ± 2.62a | 71.49 ± 1.32a | 68.16 ± 3.11a | 249.17 ± 2.17a | 169.84 ± 1.96a | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 3.27 ± 0.12b | 56.22 ± 1.99a | 68.93 ± 3.36a | 65.17 ± 2.96a | 248.24 ± 2.36a | 156.58 ± 2.54b | |

| Pea starch | Control | 4.15 ± 0.13a | 55.15 ± 1.21b | 58.27 ± 1.89c | 50.67 ± 3.15b | 166.99 ± 2.26c | 147.86 ± 1.32c |

| PS | 3.57 ± 0.21b | 56.28 ± 1.36b | 61.28 ± 0.96b | 63.68 ± 1.27a | 173.06 ± 1.55b | 160.21 ± 3.21b | |

| PS + MU-40 kHz | 3.29 ± 0.19b | 68.78 ± 3.18a | 76.72 ± 2.87a | 60.10 ± 3.51a | 180.22 ± 1.31a | 174.59 ± 2.57a | |

| PS + MU-40/60 kHz | 3.31 ± 0.15b | 68.30 ± 2.96a | 75.43 ± 2.55a | 61.69 ± 1.89a | 182.57 ± 1.83a | 176.33 ± 1.98a |

Besides, the ultrasonic treatment further reduced the hardness of starch and improved the textural properties such as cohesiveness, elasticity, viscosity, chewiness and adhesiveness. This is mainly due to the disruption and reorganization of amylose and amylopectin in starch by high-power or high-intensity ultrasound, which resulted in the alteration of the textural properties of starch [55]. There was no significant difference in the texture properties of the three starch gels between PS + MU-40 kHz and PS + MU-40/60 kHz. This was probably because the similar degree of damage to starch molecules by different modes of ultrasonic treatment, resulting in similar amylose content, which makes the hardness, elasticity, viscosity and other texture properties closer. Nie, Li, Liu, Lei and Li [56] found that the hardness decreased significantly when the sonication time and intensity increased.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we systematically investigated the effects of different ultrasonic power, time, and frequency treatments on the binding of corn starch (type A crystalline), potato starch (type B crystalline) and pea starch (type C crystalline) with rose polyphenols. The results showed that ultrasonic treatment can substantially increase the binding rate of starch and rose polyphenols. SEM results showed that all the three polyphenol-starch complexes appeared obvious pits and cracks, indicating that they were disrupted after sonication, which created favorable conditions for the binding of starch and polyphenols. Besides, no new absorption peaks appeared in any of the three polyphenol-starch complexes after ultrasonic treatment, and the positions of the absorption peaks of the characteristic groups did not change the chemical structure of the starch, but the DO and DD values increased, indicating that the ultrasonic treatment facilitated the complex to form new ordered and double helix structure from the results of FT-IR. The results of in vitro digestive properties showed that sonication reduced the RDS content and increased the SDS and RS content of the three polyphenol-starch complexes, resulting in improved digestive properties for processing of hypoglycemic foods. The textural properties showed that ultrasonic treatment optimized the hardness, elasticity, viscosity, chewiness and other textural properties of the three polyphenol-starch complexes. Rheological experiments showed that ultrasonic treatment significantly optimized the rheological properties of three polyphenol-starch complexes, providing theoretical support for their further processing. Therefore, the polyphenol-starch complexes studied in this paper can effectively reduce the rate of blood glucose rise after consumption, and also improve the textural and rheological properties of starch, providing a new type of healthy food.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Baoguo Xu: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Chao Zhang: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Zhenbin Liu: Writing – review & editing. Hanshan Xu: Writing – review & editing. Benxi Wei: Writing – review & editing. Bo Wang: Writing – review & editing. Qin Sun: Investigation, Methodology. Cunshan Zhou: Writing – review & editing. Haile Ma: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF11001700).

References

- 1.Zhu F. Interactions between starch and phenolic compound. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015;43:129–143. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi Y., Zhou S., Fan S., Ma Y., Li D., Tao Y., Han Y. Encapsulation of bioactive polyphenols by starch and their impacts on gut microbiota. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021;38:102–111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W., Zhu H., Rong L., Chen Y., Yu Q., Shen M., Xie J. Purple red rice bran anthocyanins reduce the digestibility of rice starch by forming V-type inclusion complexes. Food Res. Int. 2023;166 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu T., Li X., Ji S., Zhong Y., Simal-Gandara J., Capanoglu E., Xiao J., Lu B. Starch modification with phenolics: methods, physicochemical property alteration, and mechanisms of glycaemic control. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;111:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juansang J., Puttanlek C., Rungsardthong V., Puncha-arnon S., Uttapap D. Effect of gelatinisation on slowly digestible starch and resistant starch of heat-moisture treated and chemically modified canna starches. Food Chem. 2012;131:500–507. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu L., Zhang M., Ju R., Wang Y., Chitrakar B., Wang B. Effect of different drying methods on the quality of restructured rose flower (Rosa rugosa) chips. Drying Technol. 2020;38:1632–1643. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng M., Xu B., Nahidul Islam M., Zhou C., Wei B., Wang B., Ma H., Chang L. Individual and synergistic effect of multi-frequency ultrasound and electro-infrared pretreatments on polyphenol accumulation and drying characteristics of edible roses. Food Res. Int. 2023;163 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu L., Zhang M., Mujumdar A.S., Chang L. Convenient use of near-infrared spectroscopy to indirectly predict the antioxidant activitiy of edible rose (Rose chinensis Jacq “Crimsin Glory” H.T.) petals during infrared drying. Food Chem. 2022;369 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu L., Zhang M., Mujumdar A.S., Chang L. Effect of edible rose (Rosa rugosa cv. Plena) flower extract addition on the physicochemical, rheological, functional and sensory properties of set-type yogurt, Food. Bioscience. 2021;43 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu B., Feng M., Tiliwa E.S., Yan W., Wei B., Zhou C., Ma H., Wang B., Chang L. Multi-frequency power ultrasound green extraction of polyphenols from Pingyin rose: Optimization using the response surface methodology and exploration of the underlying mechanism. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022;156 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegde A.S., Gupta S., Sharma S., Srivatsan V., Kumari P. Edible rose flowers: A doorway to gastronomic and nutraceutical research. Food Res. Int. 2022;162 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amoako D.B., Awika J.M. Resistant starch formation through intrahelical V-complexes between polymeric proanthocyanidins and amylose. Food Chem. 2019;285:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao H., Lin Q., Liu G.-Q., Yu F. Evaluation of black tea polyphenol extract against the retrogradation of starches from various plant sources. Molecules. 2012;17:8147–8158. doi: 10.3390/molecules17078147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorentz C., Pencreac’h G., Soultani-Vigneron S., Rondeau-Mouro C., de Carvalho M., Pontoire B., Ergan F., Le Bail P. Coupling lipophilization and amylose complexation to encapsulate chlorogenic acid. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;90:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chai Y., Wang M., Zhang G. Interaction between Amylose and Tea Polyphenols Modulates the Postprandial Glycemic Response to High-Amylose Maize Starch. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:8608–8615. doi: 10.1021/jf402821r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Z., Zhao B., Chen J., Chen L., Zheng B. Insight into the characterization and digestion of lotus seed starch-tea polyphenol complexes prepared under high hydrostatic pressure. Food Chem. 2019;297 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.124992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao B., Wang B., Zheng B., Chen L., Guo Z. Effects and mechanism of high-pressure homogenization on the characterization and digestion behavior of lotus seed starch–green tea polyphenol complexes. J. Funct. Foods. 2019;57:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obiro W.C., Ray S.S., Emmambux M.N. V-amylose structural characteristics, methods of preparation, significance, and potential applications. Food Rev. Intl. 2012;28:412–438. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao B., Sun S., Lin H., Chen L., Qin S., Wu W., Zheng B., Guo Z. Physicochemical properties and digestion of the lotus seed starch-green tea polyphenol complex under ultrasound-microwave synergistic interaction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;52:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu B., Sylvain Tiliwa E., Yan W., Roknul Azam S.M., Wei B., Zhou C., Ma H., Bhandari B. Recent development in high quality drying of fruits and vegetables assisted by ultrasound: A review. Food Res. Internat. 2022;152 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdul R., Ankita K., Xin-An Z., Muhammad A.F., Rabia S., Ibrahim K., Azhari S., Maratab A., Muhammad F.M. Ultrasound based modification and structural-functional analysis of corn and cassava starch. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu B., Ren A., Chen J., Li H., Wei B., Wang J., Azam S.M.R., Bhandari B., Zhou C., Ma H. Effect of multi-mode dual-frequency ultrasound irradiation on the degradation of waxy corn starch in a gelatinized state. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;113 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J., Tian L., Fang Y., Chen W., Hunag G. Ultrasonic-assisted preparation of maize starch-caffeic acid complex: physicochemical and digestion properties. Starch - Stärke. 2021;73(1-2):2000084. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu B., Yu S., Shi C., Gu J., Shao Y., Chen Q., Li Y., Mezzenga R. Amyloid-polyphenol hybrid nanofilaments mitigate colitis and regulate gut microbial dysbiosis. ACS Nano. 2020;14:2760–2776. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b09125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y., Tian J., Kong X., Yang W., Yin X., Xu E., Chen S., Liu D., Ye X. Physicochemical and digestibility characterisation of maize starch–caffeic acid complexes. LWT. 2020;121:108857. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han M., Bao W., Wu Y., Ouyang J. Insights into the effects of caffeic acid and amylose on in vitro digestibility of maize starch-caffeic acid complex. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;162:922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong H., Ying L., Dong-Hui L., Qiang Z., Jun-Hu C., Jin-Hua W. Structural variations of rice starch affected by constant power microwave treatment. Food Chem. 2021;359 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miao M., Xiong S., Jiang B., Jiang H., Cui S.W., Zhang T. Dual-enzymatic modification of maize starch for increasing slow digestion property. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;38:180–185. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X., Xi C., Liang W., Zheng J., Zhao W., Ge X., Shen H., Zeng J., Gao H., Li W. Influence of pre- or post-electron beam irradiation on heat-moisture treated maize starch for multiscale structure, physicochemical properties and digestibility. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023;313 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilay G., Ilkay S. The effect of psyllium fiber on the in vitro starch digestion of steamed and roasted wheat based dough. Food Res. Int. 2023;168 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashoka R., Prisana S., Worawikunya K., Rungtiva W., S.L. M.C. Molecular structure and linear-non linear rheology relation of rice starch during milky, dough, and mature stages. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023;312 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klara N., Mathias J., Corine S., Hanna E.R., H.M. S., Maud L. Pasting and gelation of faba bean starch-protein mixtures. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;138 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H., Yao Y., Zhang Y., Zheng B., Zeng H. Ultrasonication-mediated formation of V-type lotus seed starch for subsequent complexation with butyric acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;236 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei B., Qi H., Wang Z., Bi Y., Zou J., Xu B., Ren X., Ma H. The ex-situ and in-situ ultrasonic assisted oxidation of corn starch: A comparative study. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;61:104854. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han X., Zhang M., Zhang R., Huang L., Jia X., Huang F., Liu L. Physicochemical interactions between rice starch and different polyphenols and structural characterization of their complexes. LWT. 2020;125 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang M., Chang L., Jiang F., Zhao N., Zheng P., Simbo J., Yu X., Du S.-K. Structural, physicochemical and rheological properties of starches isolated from banana varieties (Musa spp.) Food Chemistry: X. 2022;16 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Yang Y., Zhu S., Liu B., Zhong F., Huang D. Tea polyphenols-OSA starch interaction and its impact on interface properties and oxidative stability of O/W emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;135 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dan L., Qiang X., Shimin G., Wentong X. Potato starch films by incorporating tea polyphenol and MgO nanoparticles with enhanced physical, functional and preserved properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;221:108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karimi S.I., Piri G.S., Sajad P., Amirafshar A. Composite film based on potato starch/apple peel pectin/ZrO2 nanoparticles/ microencapsulated Zataria multiflora essential oil; investigation of physicochemical properties and use in quail meat packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;117 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chi C., Wang H., Wang S., He Y., Zheng X., Huang L., Jiao W. Promoting starch interaction with caffeic acid during hydrothermal treatment for slowing starch digestion. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022;82 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maniglia B.C., Castanha N., Rojas M.L., Augusto P.E. Emerging technologies to enhance starch performance. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020;37:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kou T., Gao Q. A study on the thermal stability of amylose-amylopectin and amylopectin-amylopectin in cross-linked starches through iodine binding capacity. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;88:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carmona-Garcia R., Sanchez-Rivera M.M., Méndez-Montealvo G., Garza-Montoya B., Bello-Pérez L.A. Effect of the cross-linked reagent type on some morphological, physicochemical and functional characteristics of banana starch. Musa paradisiacaCarbohydr. Polym. 2008;76:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sreejani B., Andreas H., Mathias B., Markus M., Prakash S.P., V.T.A. Insights into the structural, thermal, crystalline and rheological behavior of various hydrothermally modified elephant foot yam (Amorphophallus paeoniifolius) starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;129 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Husnain R., Kashif A., Haile M., Qiufang L., Xiaofeng R. Structural and physicochemical characterization of modified starch from arrowhead tuber (Sagittaria sagittifolia L.) using tri-frequency power ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Labat E., Morel M.H., Rouau X. Effect of laccase and manganese peroxidase on wheat gluten and pentosans during mixing. Food Hydrocoll. 2001;15:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Englyst H.N., Kingman S.M., Cummings J.H. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992;46:S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao X., Yongheng Z., Qi C., Lipeng W., Shengyang J., Bowen Y., Yongzhu Z., Jianfu S., Baiyi L. Modulating the digestibility of cassava starch by esterification with phenolic acids. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;127 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tao X., Xiaoxi L., Shengyang J., Yongheng Z., Jesus S.-G., Esra C., Jianbo X., Baiyi L. Starch modification with phenolics: methods, physicochemical property alteration, and mechanisms of glycaemic control. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;111:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang C., Narayanamoorthy S., Ming S., Li K., Cantre D., Sui Z., Corke H. Rheological properties, structure and digestibility of starches isolated from common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties from Europe and Asia. LWT. 2022;161 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jia S., Zhao H., Tao H., Yu B., Liu P., Cui B. Influence of corn resistant starches type III on the rheology, structure, and viable counts of set yogurt. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;203:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdolkhalegh G., Mohammadzadeh M.J., Ali M., Esmaeilzadeh K.R. Physicochemical, structural, and rheological characteristics of corn starch after thermal-ultrasound processing. Food Sci. Technol. Internat. = Ciencia y tecnologia de los alimentos internacional. 2021;29:168–180. doi: 10.1177/10820132211069242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamin X., Fei X., Jie C., Ling C., Chaoyue C., Yangjing L. Effect of polyphenol-starch interactions on the starch properties of chestnut. J. Henan Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Edition) 2021;42:30–38. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wen Y., Yao T., Xu Y., Corke H., Sui Z. Pasting, thermal and rheological properties of octenylsuccinylate modified starches from diverse small granule starches differing in amylose content. J. Cereal Sci. 2020;95 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herceg I.L., Jambrak A.R., Šubarić D., Brnčić M., Herceg Z. Texture and pasting properties of ultrasonically treated corn starch. Czech J. Food Sci. 2010;28:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nie H., Li C., Liu P.-H., Lei C.-Y., Li J.-B. Retrogradation, gel texture properties, intrinsic viscosity and degradation mechanism of potato starch paste under ultrasonic irradiation. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;95:590–600. [Google Scholar]