Highlights

-

•

Ultrasonic frequency and power effects on peroxynitrite formation by sonolysis were examined.

-

•

Energy required for ultrasound-induced peroxynitrite formation increases with frequency.

-

•

Peroxynitrite formation decreases with frequency and increases with power.

-

•

High dependence of peroxynitrite production by sonolysis on ultrasonic power.

-

•

Peroxynitrite produced by sonolysis can be used as a dosimeter in sonochemistry.

Keywords: Peroxynitrite, Sonolysis, Frequency, Ultrasonic power, Dosimetry

Abstract

There is a lack of literature on peroxynitrite formation due to sonolysis of aerated water. In this work, the impact of sonication parameters, frequency and power, on ultrasonic peroxynitrite production in aerated alkaline water was investigated. Peroxynitrite formation was clearly established with undeniable evidence at all the tested frequencies in the range of 516–1140 kHz with a typical G-value (energy-specific yield) of 0.777 × 10−10, 0.627 × 10−10, 0.425 × 10−10 and 0.194 × 10−10 mol/J at 516, 558, 860 and 1140 kHz, respectively. The ultrasonication frequency has a direct impact on the sonochemical peroxynitrite production. Increasing the ultrasonication frequency in the interval 321–1140 kHz reduces peroxynitrite formation. The most practical sonochemistry dosimetries, including hydrogen peroxide production, triiodide dosimetry, Fricke dosimetry, and 4-nitrocatechol formation, were compared with the sonochemical efficiency of the reactors used to produce peroxynitrite. The G-value, energy specific yield, for the tested dosimetries was higher than that for peroxynitrite formation, regardless of frequency. For all chemical dosimetries investigated, the same trend of frequency dependence was found as for peroxynitrite generation. The influence of ultrasonication power on peroxynitrite formation by sonication at diverse frequencies in the interval 585–1140 kHz was studied. No peroxynitrite was formed at lower acoustic power levels, regardless of frequency. As the frequency increases, more power is required for peroxynitrite formation. The production of peroxynitrite increased as the acoustic power increased, despite the frequency of ultrasonic waves. Ultrasonic power is a key factor in the production of peroxynitrite by sonolysis. Since peroxynitrite is uniformly distributed in the bulk solution, peroxynitrite-sensitive solutes can be transformed both in the bulk of the solution and in the surfacial region (shell) of the cavitation bubble. The formation of peroxynitrite should be taken into account in sonochemistry, especially at higher pH values. Ultrasonic peroxynitrite formation in alkaline solution (pH 12) can be considered as a kind of chemical dosimetry in sonochemistry.

1. Introduction

The application of ultrasonic waves to a liquid medium causes particles or molecules to vibrate at their normal locations. Due to the sinusoidal nature of the acoustic pressure change, the molecules are rarefied during the rarefaction phase and compressed during the compression phase. A cavity is formed when the applied pressure breaks the molecular bond. Acoustic cavitation is the name given to this process. Although water has a relatively high tensile strength (requiring a negative pressure of about 1500 atm), cavitation can happen at very low pressures (20 atm) because of the existence of dissolved gas molecules that act as cavitation nuclei. Unless dispersed, a cavitation bubble, once formed, will grow in size by rectified diffusion or bubble coalescence. Harsh conditions, such as high pressures exceeding several hundred atmospheres and high temperatures exceeding a few thousand Kelvin, are thought to occur inside cavitation bubbles during their final compression stage [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. In these intense environments, water molecules are thermally split into hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen (•OH and H•), and other moieties can generate additional radical species (reactions (1)−(5)) [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17].

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

These major sonolysis radicals typically recombine in the absence of any solute to generate hydrogen peroxide, which is released into the medium (reactions (6)−(7)) [9], [18], [19].

| (6) |

| (7) |

Under the influence of ultrasound on an aerated aqueous solution, nitrate and nitrite ions are produced. NO•, according to reactions (8), (9), should be the main product of the process in bubbles at high temperature. The release of HNO2 into the medium is caused by reaction (10) at the interface. Hydrogen peroxide converts nitrite to nitrate (reactions (11)−(12)) [20], [21], [22], [23].

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

Nitrogen monoxide (NO•) and superoxide radical anion (O2•−) undergo a rapid combination reaction (k = 4–7 × 109 M−1 s−1 [24]) to generate peroxynitrite (reaction (13):

| (13) |

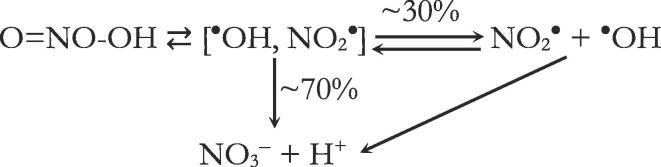

Peroxynitrite was first suggested as a physiologically pertinent cytotoxic intermediate by Beckman et al. [25]. The potential toxicity of peroxynitrite, due to its chemical reactivity in the presence of hydroxyl radical scavengers, was linked to the production of •OH or •OH-like radical species. The homolysis of peroxynitrite catalyzed by proton is supposed to produce the putative •OH product; the yield of •OH from ONOOH is thought to be approximately 30% [26], with the remainder isomerized to nitrate (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Proton-catalyzed decay of peroxynitrite.

In an alkaline solution, the peroxynitrite anion is stable, but its acid undergoes a first-order kinetics rearrangement to nitrate (reactions (14), (15) [23].

| (14) |

| (15) |

Peroxynitrous acid is stable at basic pH and can form peroxynitrite according to the reaction (16):

| (16) |

The sonochemical formation of peroxynitrite in aerated water has been observed for the first time by Mark et al. [23]. After irradiating an aqueous solution of NaOH (pH 12) with 321 kHz ultrasound, they observed the formation of peroxynitrite. Based on its absorption spectrum, peroxynitrite was clearly identified.

To the best of our knowledge, no other paper on the ultrasonic generation of peroxynitrite has been reported in the literature. Therefore, the purpose of the present paper is to examine the impact of ultrasonic frequency and power on the sonochemical formation of peroxynitrite in aerated alkaline water. Peroxynitrite production was demonstrated at different frequencies, namely 516, 585, 860, and 1140 kHz. Dosimetries such as hydrogen peroxide, Fricke, triiodide, and 4-nitrocatechol were investigated to increase the knowledge of sonolytic peroxynitrite formation. Different acoustic powers at diverse frequencies ranging from 585 to 1140 kHz were investigated to establish the relationship between the influence of ultrasonication power and frequency on peroxynitrite formation.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Reagents

In the present study, only analytical-grade compounds were used. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium iodide (KI), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), 4-nitrophenol and ammonium heptamolybdate ((NH4)6Mo7·4H2O) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich. Mohr’s salt (FeSO4(NH4)2SO4·6H2O) was provided by Panreac.

2.2. Ultrasonic reactors

Throughout the tests, water jacketed cylindrical glass reactors (500 mL of total capacity) were utilized for temperature control of the sonolysis experiments. A thermocouple submerged in the reaction medium was employed to measure the temperature within the reactors. It was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C by flowing refrigeration liquid throughout the cell. A Meinhardt multifrequency transducer with a 5.3 cm-diameter active area (model E/805/T/M) was used to transmit ultrasound irradiation from the bottom at 585, 860, and 1140 kHz (Fig. 1). The generator that supplies the multifrequency transducer runs at different electrical powers, which are represented by 3 fixed positions, viz. Amp. 2, Amp. 3, and Amp. 4. The 516 kHz ultrasonic irradiation was delivered to the reactor from the bottom through a 4 cm diameter piezoelectric disk mounted on a 5 cm diameter Pyrex plate. Under different operating conditions, 300 mL has been employed for sonochemical investigations at 585, 860, and 1140 kHz, and 90 mL has been used at 516 kHz. The conventional calorimetric technique was used to determine the amount of acoustic power dissipated in reactors under various ultrasonic conditions [27], [28], [29], [30]. The acoustic power levels employed in this investigation are shown in Fig. 2. The sonolytic powers ranged from 9.7 to 79 W at 585 kHz, from 12.3 to 107.3 W at 860 kHz and from 15 to 114 W at 1140 kHz. The acoustic power used at 516 kHz was 38.3 W.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the experimental apparatus (Meinhardt Ultrasonics high-frequency reactor (model E/805/T/M)).

Fig. 2.

Determined acoustic power at different ultrasonic conditions of frequency and amplitude position (conditions: V: 300 mL, frequency: 585, 860 and 1140 kHz, amplitude position: 2, 3 and 4).

2.3. Procedures

The formation of peroxynitrite was determined by spectrophotometry using a Biochrom WPA Lightwave II UV–visible spectrophotometer by following the evolution of the UV spectrum of an aqueous solution of NaOH at 0.01 M (pH 12) during ultrasonic irradiation. Peroxynitrite was identified by an intense band at 300 nm (the molar absorption coefficient ε = 1,670 L/mol·cm).

Analytical measurements of the concentrations of hydrogen peroxide were made using the iodometric technique [31]. The quartz cell of the spectrophotometer was filled with sample aliquots (200 µL) regularly collected from the reactor during sonolysis, together with 20 µL of ammonium heptamolybdate (0.01 M) and 1 mL of potassium iodide (0.1 M). The triiodide ion (I3−) is formed by the reaction of the iodide ion (I−) with H2O2. The mixtures were let stand for 5 min prior to absorbance determination. The absorbance was measured with a Biochrom WPA Lightwave II UV–visible spectrophotometer at 352 nm (the molar extinction coefficient ε = 26,300 L/mol·cm), which corresponds to the maximum wavelength of the produced triiodide ions (I3−).

Potassium iodide solution (0.1 M, 300 mL) was irradiated with ultrasonic waves. In this dosimetry, the formed I2 reacts with the iodide ions, present in excess, to produce triiodide ions (I3–), which absorb at a wavelength of 352 nm (the molar extinction coefficient ε = 26,000 L/mol·cm). The absorbance of the I3– ions was monitored using a Biochrom WPA Lightwave II UV–visible spectrophotometer.

In the Fricke dosimetry, Fe2+ ions in acidic medium are oxidized by hydroxyl radicals and H2O2 generated by sonolysis to form Fe3+ ions. The absorbance of the produced Fe3+ ions was analyzed at 303 nm (ε = 2197 L/mol·cm). The Fricke solution was made using H2SO4 (0.4 M), FeSO4(NH4)2SO4·6H2O (10−3 M) and NaCl (10−3 M).

When ultrasonic waves are applied to a 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) solution, hydroxyl radicals generated react with 4-NP molecules to form 4-nitrocatechol (4-NC). The amount of hydroxyl radicals produced during sonication is quantified by photometrically monitoring the produced 4-NC in basic medium. The aqueous solution of 4-NP has a maximum absorption at 399 nm. The 4-NP solution was prepared at a concentration of 139.11 mg/L (1 mM) and its pH was adjusted to 5 (pKa = 7.15). A volume of 300 mL of this solution was irradiated in the ultrasonic reactor. Sample aliquots of 1.5 mL collected periodically from the sonochemical reactor during sonication were added to an equivalent volume (1.5 mL) of 0.2 M NaOH in the quartz cell of the spectrophotometer. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 510 nm (ε = 12,500 L/mol·cm).

In the present work, a minimum of three separate runs of each of the experiments were carried out.

3. Results and discussion

Sonochemical efficiency, called G-value (mol/J), is an energy-specific yield defined by the ratio of compound concentration (C in M) to ultrasonic energy density (Ev in kJ/L) based on the following equation:

| (17) |

3.1. Peroxynitrite formation

Although peroxynitrite, with a pKa of 6.5–6.8, is stable in basic media, its protonated form is very unstable and decomposes with a half-life of about 1 s at pH 7.4 [32]. As a result, strong alkali is frequently used to produce or stabilize peroxynitrite solutions.

Representative UV–visible spectra variations of 0.01 M NaOH solution (300 mL and pH 12) as a function of sonication time at an ultrasonication frequency of 585 kHz and an acoustic power of 79 W were observed to elucidate the production of peroxynitrite (ONOO−) due to ultrasonic action. The relevant spectra are given in Fig. 3(a). These spectra clearly show peroxynitrite formation identified by an intense band at 300 nm with a molar extinction coefficient ε = 1670 L/mol·cm [33], [34], [35]. As the sonication time increases, the broad absorption band becomes evident. This maximum absorption corresponds to that of the peroxynitrite anion [23], [32], [36]. The peroxynitrite concentration in the reacting medium increases linearly with the ultrasonic exposure time and as a function of the ultrasonic energy density (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Changes in UV–visible absorption spectra observed during sonolysis of an aqueous 0.01 M NaOH solution (pH 12) vs. time at (a) 585 kHz (conditions: volume: 300 mL, acoustic power: 79 W) and (b) 516 kHz (conditions: volume: 90 mL, acoustic power: 38.3 W) showing the formation of peroxynitrite.

Fig. 4.

Linear evolution of peroxynitrite formation in NaOH solution (pH 12) vs. ultrasonic energy density at 585 kHz (conditions: volume: 300 mL, temperature: 25 ± 1 °C). The insert shows the results obtained at 516 kHz (conditions: volume: 90 mL, temperature: 25 ± 1 °C).

In order to confirm the formation of peroxynitrite at different ultrasonic conditions by using another sonochemical reactor and small volume of sodium hydroxide solution to obtain higher acoustic energy density, the application of 516 kHz and 38.3 W ultrasonic irradiation to 90 mL of the aerated NaOH solution (0.01 M) confirmed with incontrovertible evidence the production of peroxynitrite on the basis of its optical absorption band at 300 nm (Fig. 3(b) and 4). After a sonolysis time of 210 min, the peroxynitrite concentration obtained in these conditions was 408 µM. The peroxynitrite production rate was ∼ 2 µM/min.

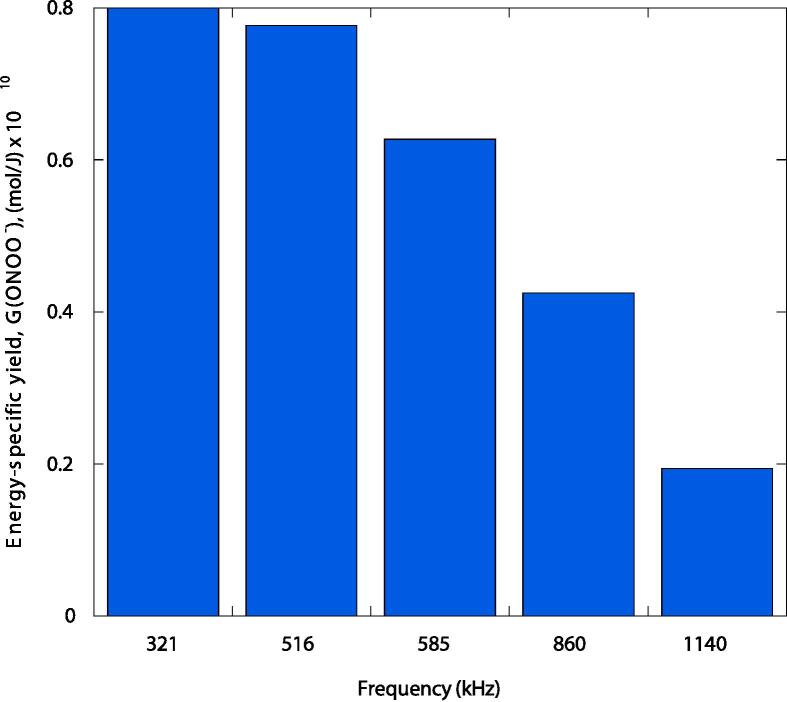

The typical energy-specific yield, G value, obtained for peroxynitrite production by sonolysis was G(ONOO−) = 0.777 × 10−10 mol/J at 516 kHz ultrasonic irradiation and 38.3 W acoustic power, and G(ONOO−) = 0.627 × 10−10 mol/J under 558 kHz of ultrasound frequency and 79 W of ultrasonic power. These results are slightly lower than those obtained by Mark et al. [23] at 321 kHz frequency and 170 W/kg dose rate as measured by calorimetry, who observed a G-value of 0.8 × 10−10 mol/J of absorbed ultrasonic energy. This slight difference was most likely due to the frequency effect, which will be the subject of discussion later in this paper.

Peroxynitrite mostly occurs as cis-ONOO− in alkaline aqueous solution [37]. The peroxynitrite anion is relatively stable at pH 8.6 and 25 °C, with kobs ≈ 0.01 s−1 [37], toward conversion to nitrate (via protonation of the peroxynitrite ion to peroxynitrous acid, ONOOH). At pH < 6.0 and 25 °C, peroxynitrous acid decomposes rapidly to nitrate with a conversion rate of k = 1.3 s−1 [37]. Peroxynitrous acid is a crucial intermediary in the general conversion of cis-ONOO− to NO3− (reactions (18), (19)), according to the pH-rate profile for the unimolecular decomposition of peroxynitrite, which displays sigmoidal behavior with a pKa of 6.5–6.8. An equilibrium between the cis,cis isomer of ONOOH and the cis-ONOO− (reaction (18) was predicted with pKa = 6.5–6.8 [37].

| (18) |

| (19) |

Mark et al. [23] proposed a likely pathway for peroxynitrite formation by sonolysis (reactions (20), (21), (22), (23), (24)).

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

| (24) |

Peroxynitrite is homogenously dispersed in the bulk solution. This means that a solute susceptible to the powerful oxidant peroxynitrite can be sonochemically transformed not only in the immediate vicinity of the cavitation bubble, but also in the bulk of the solution [23].

In order to interpret the results of the sonochemical formation of peroxynitrite, experimental measurements of the concentration of H2O2 produced by ultrasonic waves at 585 kHz and at 79 W acoustic energy in the absence of scavengers of hydroxyl radicals were determined in aerated water (Fig. 5). The concentration of H2O2 in sonicated water increased linearly with increasing acoustic energy density. The typical energy-specific yield G-value obtained for H2O2 sonolytic formation in aerated water was G(H2O2) = 3.37 × 10−10 mol/J. The G-value of H2O2 formation G(H2O2) = 3.37 × 10−10 mol/J is 5.4 times higher than that of peroxynitrite production G(ONOO−) = 0.627 × 10−10 mol/J at 558 kHz of ultrasound frequency and 79 W of ultrasonic power. For the generation of H2O2 in argon-saturated water (Fig. 5), which grew linearly with increasing acoustic energy density, a representative G-value of 4.84 × 10−10 mol/J was obtained at the same ultrasonic conditions used under air-saturated water (558 kHz and 79 W). This value is 7.7 times greater than that obtained for peroxynitrite.

Fig. 5.

Production yields of H2O2 (under air and Ar atmosphere), I3−, Fe3+ and 4-nitrocatechol vs. the ultrasonic energy density at 585 kHz (conditions: volume: 300 mL, temperature: 25 ± 1 °C).

For a more detailed examination of the results for the sonochemical formation of peroxynitrite, different dosimetries, namely triiodide dosimetry, Fricke dosimetry, and 4-nitrophenol oxidation (i.e., 4-nitrocatechol formation) [28], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], were performed at the same ultrasonic conditions (558 kHz and 79 W) mentioned for the sonolytic production of peroxynitrite. The results obtained for the three dosimetries are shown in Fig. 5. A linear augmentation in the concentration of I3−, Fe3+ and 4-NC produced by sonolysis with the acoustic energy density was observed. The energy-specific yield G-value obtained for the different dosimetries used is G(Fe3+) = 12.50 × 10−10 mol/J, G(I3−) = 4.36 × 10−10 mol/J and G(4-NC) = 1.066 × 10−10 mol/J. The G-value of the various dosimetries is higher than that obtained for peroxynitrite. The G-value of I3−, Fe3+ and 4-NC ultrasonic formation is 19.9, 7.0 and 1.7 times greater than that of peroxynitrite generation, respectively.

The G-value for the Fricke and triiodide dosimetries can be represented by [38]:

| (25) |

| (26) |

The G-value obtained for the Fricke dosimeter (G(Fe3+) = 12.50 mol/J) is in reasonable agreement with that determined for the triiodide dosimetry G(I3−) = 4.36 × 10−10 mol/J, since the G(Fe3+)-value calculated from the triiodide dosimeter is predicted to be G(Fe3+)calculated = 13.48 × 10−10 mol/J. The same tendency was stated by Iida et al. [38], who compared the G-value of the Fricke and triiodide dosimetries.

4-NP is oxidized via a hydrogen abstraction reaction involving the electrophilic attack of hydroxyl radical, with k = 3.8 × 109 M−1s−1 [18], at the ortho-position of the benzene ring (to a lesser extent, hydroxyl radical-addition occurs at the para-position) [29], [39]. The G-value of the 4-NC dosimeter can be expressed as follows:

| (27) |

The 4-NC dosimetry resulted in a lower G-value, G(4-NC) = 1.066 × 10−10 mol/J. The difference was thought to be due to the low yield of 4-NC formed from the oxidation of 4-NP. The G value for 4-NC formation follows the same trend as the terephthalic acid dosimetry. The same trends have been described in the literature where the G-value of Fricke dosimeter and terephthalate dosimeter have been compared [38], [43].

As mentioned above, the G-value of the three dosimetries tested (I3−, Fe3+ and 4-NC) is at least almost twice higher than that of the peroxynitrite formation. However, the G-value (G(ONOO−)sonolysis = 0.627 × 10−10 mol/J at 585 kHz and 79 W and G(ONOO−) = 0.777 × 10−10 mol/J at 516 kHz and 38.3 W) for peroxynitrite formation by sonolysis is comparable to that for radiolysis (G(ONOO−)radiolysis = 0.7 × 10−10 mol/J [44]). The standard Gibbs free energy of formation determines the amount of chemical energy stored in the accumulated peroxynitrite. The standard Gibbs free energy of formation of peroxynitrite ((ONOO−) = 69 kJ/mol) is 180 kJ/mol greater than that of nitrate [44]. This energy is similar to the energy of hydrogen combustion on a molar basis. For peroxynitrous acid, this standard Gibbs free energy of formation ((ONOOH) = 31 kJ/mol [44]) indicates that about 30% of the peroxynitrous acid must decompose into nitrogen dioxide and hydroxyl radicals (Scheme 1). The main conclusion from these results is that ultrasound-induced peroxynitrite formation requires higher energy, which may explain the lower G-value obtained for peroxynitrite compared to the dosimetries tested.

3.2. Influence of frequency

A volume of 300 mL of aerated NaOH solution (pH 12) was sonicated at three diverse frequencies: 585, 860 and 1140 kHz and at an amplitude position of Amp. 4 (Fig. 2). The results of the impact of frequency on peroxynitrite generation are expressed as a function of ultrasonic energy density, since the calorimetric power is different at different frequencies at the same amplitude position, as shown in Fig. 2. Fig. 6 illustrates the peroxynitrite formation during sonication at different frequencies. This figure demonstrates that peroxynitrite formation is directly related to ultrasound frequency. The amount of peroxynitrite produced at 585 kHz is greater than that produced at 860 and 1140 kHz for a given ultrasonic energy density. For example, at an ultrasonic energy density of 1500 kJ/L, increasing the frequency from 585 to 860 and 1140 kHz results in a decrease in the peroxynitrite concentration from 94.05 to 63.75 and 29.10 µM, respectively. The number of active bubbles and the single bubble yield are the two key variables that fluctuate with ultrasonic frequency and are responsible for these outcomes [45]. More specifically, a lower frequency (585 kHz in this case) gives the bubble more time to expand. This results in a large expansion ratio (Rmax/R0) and thus a higher compression ratio (Rmax/Rmin) of the bubble. As a result, the dissociation of nitrogen/oxygen and water vapor molecules into atoms and free radicals is accelerated, and the collapse will be more powerful, producing higher temperatures. In addition, at higher frequencies, bubbles collapse faster. This prevents the chemical mechanism inside the bubble from evolving and transforming the reactant molecules into atoms and free radicals [46]. Therefore, as the collapse time and temperature of the bubble decrease with increasing frequency, the dissociation of oxygen and water molecules and the rate of hydroxyl radical generation inside the bubble would decrease. In the surfacial layer (shell) of the cavitation bubble, the hydrogen peroxide, formed by the reaction of •OH and HO2• radicals, is exposed to further attack by •OH radicals, resulting in the production of superoxide, which reacts with nitric oxide to produce peroxynitrite (reactions (20)−(24)). On the other hand, there was a significant increase in the number of active bubbles with increasing frequency in the interval 585–1140 kHz [47]. Thus, the significant effect of frequency on individual bubble yield, which was found to be less effective at higher frequencies, was mainly responsible for the net influence of frequency in the interval 585–1140 kHz on peroxynitrite formation by sonolysis [47].

Fig. 6.

Effect of ultrasound frequency on the sonochemical formation of peroxynitrite as a function of ultrasonic energy density (conditions: 0.01 M NaOH (pH 12), volume: 300 mL, temperature: 25 ± 1 °C).

Fig. 7 shows the yield of peroxynitrite production as a function of the ultrasonic frequency tested in the present work compared to that of Mark et al. [23] using 321 kHz. The results show that increasing the ultrasonic frequency from 321 to 516, 585, 860, and 1140 kHz results in a decrease in energy-specific yield of 3%, 22%, 47%, and 76%, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Peroxynitrite production yield as a function of ultrasound frequency.

Different dosimetries (H2O2, I3−, Fe3+ and 4-NC) were performed under the same ultrasonic conditions used to produce peroxynitrite. The concentrations of the different species were found to increase linearly with the ultrasonic energy density (figures not shown). The results obtained for these dosimetries at the three frequencies tested are summarized in Table 1. Regardless of the dosimetry tested in this work, increasing the frequency in the interval 585–1140 kHz results in a decrease in the specific energy yield (G-value) of product formation, which is the same tendency observed for peroxynitrite production. The fact that the G-values of product formation in water decrease with increasing frequency (Table 1) indicates that the lowest sonochemical activity occurs at higher frequencies. The G-value of the different dosimetries is higher than that obtained for peroxynitrite formation. Increasing the frequency from 558 to 860 and 1140 kHz, respectively, induces a decrease in the G-value of formation of 36% and 69% for ONOO−, 55% and 67% for H2O2, 36% and 57% for I3−, 20% and 45% for Fe3+ and 42% and 54% for 4-NC. The most significant decrease in G-value at 860 kHz was observed for H2O2 followed by 4-NC and equally for ONOO− and I3− and then for Fe3+. At 1140 kHz, the G-value drop was in the following order: ONOO− > H2O2 > I3− > 4-NC > Fe3+. Furthermore, the frequency effect results obtained are in good agreement with those described in the literature [10], [19], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53].

Table 1.

Comparison between the energy-specific yield (G-value) for the formation of ONOO−, H2O2, I3−, Fe3+ and 4-NC vs. frequency.

| Frequency (kHz) | 585 | 860 | 1140 |

|---|---|---|---|

| G(ONOO−), mol/J | 0.627 × 10−10 | 0.425 × 10−10 | 0.194 × 10−10 |

| G(H2O2), mol/J | 3.37 × 10−10 | 1.52 × 10−10 | 1.11 × 10−10 |

| G(I3−), mol/J | 4.36 × 10−10 | 2.76 × 10−10 | 1.86 × 10−10 |

| G(Fe3+), mol/J | 12.50 × 10−10 | 10.03 × 10−10 | 6.92 × 10−10 |

| G(4-NC), mol/J | 1.066 × 10−10 | 0.753 × 10−10 | 0.657 × 10−10 |

3.3. Influence of ultrasonic power

The impact of ultrasonication power on peroxynitrite production by sonolysis at different frequencies, namely 585, 860, and 1140 kHz, was investigated. Fig. 8 shows that the production of peroxynitrite is linear over 120 min of sonication, regardless of the ultrasonic frequency. No peroxynitrite anions are formed at a frequency of 585 kHz and an ultrasonication power of 9.65 W. The same behavior was observed at a frequency of 860 kHz and calorimetric power of 12.33 W and at 1140 kHz for acoustic powers of 15 and 48 W. This suggests that the system depends on a threshold level of ultrasonic power to achieve efficient peroxynitrite formation. The absence of peroxynitrite formation at these ultrasound conditions is probably due to the lower energy input, which does not reach the Gibbs free energy required for product formation. After 120 min of sonication at 558 kHz, increasing the ultrasonication power from 38 to 79 W significantly increased the amount of peroxynitrite formed from 31.06 to 118.81 µM. At the same sonolysis time and 860 kHz of ultrasound frequency, the amount of peroxynitrite produced increases from 27.12 to 80.63 µM after increasing the ultrasonic power from 51 to 107.34 W. The increase in the number of cavitation bubbles explains the increase in the rate of peroxynitrite formation with acoustic power [54]. Increasing the acoustic power increases the acoustic energy transmitted to the reactor [55], [56]. This energy produced a high concentration of peroxynitrite in the solution due to the rapid pulsation and collapse of the cavitation bubbles. It has been reported that the population of cavitation bubbles (number and size) is also a function of frequency and ultrasonication power [57], [58]. Additionally, it was noted that the velocity of bubble wall has been found to be insignificant during the bubble growth phase and the first collapse stage, but it suddenly increases during the final collapse stage, reaching 24, 97, and 171 m/s at 9.65, 38, and 79 W, respectively, for a frequency of 558 kHz [57], [58]. These high implosion velocities result in stronger collapses, creating extremely high conditions inside the bubbles. In fact, the internal pressure of the bubble at the end of collapse can reach 32, 400 and 1138 atm at 9.65, 38 and 79 W, respectively, for 558 kHz ultrasonic frequency. Accordingly, at 9.65, 38 and 79 W, the temperature inside a bubble reached 1147, 2950 and 4190 K, respectively, at the end of the bubble collapse. These harsh conditions provide an exclusive environment for energetic chemical reactions [57]. The same tendencies of acoustic power increase can be generalized at 860 and 1140 kHz of ultrasonic frequencies.

Fig. 8.

Effect of ultrasonic power on the kinetics of sonochemical formation of peroxynitrite for three different frequencies (conditions: 0.01 M NaOH (pH 12), volume: 300 mL, temperature: 25 ± 1 °C).

Fig. 9 illustrates the energy-specific yield G-value for peroxynitrite formation at various ultrasonic frequencies and powers. It can be seen that when the ultrasonication power was increased from 38 to 79 W at 558 kHz, the G-value increased by 1.84 times. At 860 kHz, increasing the ultrasonic power from 51 to 107.34 W resulted in a 1.91-fold improvement in the energy-specific yield of peroxynitrite production. In summary, as the frequency increases, the energy requirement for ultrasound-induced peroxynitrite formation increases.

Fig. 9.

Effect of acoustic power on peroxynitrite production yield at different ultrasound frequencies.

4. Conclusion

The effect of ultrasonication frequency and power on the sonolytic formation of peroxynitrite in alkaline aerated water was examined. The sonochemical production of peroxynitrite was clearly demonstrated at 585 kHz ultrasound frequency and 79 W calorimetric power, and was confirmed with incontrovertible evidence using a low volume of NaOH solution (pH 12) to obtain a higher acoustic energy density in another ultrasonic reactor operating at 516 kHz frequency and 38.3 W ultrasonic power. Typical G-value, energy-specific yield, of 0.777 × 10−10 and 0.627 × 10−10 mol/J was determined at 516 kHz ultrasonic irradiation and 38.3 W acoustic power and under 558 kHz of ultrasound frequency and 79 W of ultrasonic power, respectively. The sonochemical efficiency of the reactors used for peroxynitrite production (558 kHz and 79 W) was compared with the most useful dosimetries such as hydrogen peroxide production, triiodide dosimetry, Fricke dosimetry, and 4-nitrocatechol formation. The energy-specific yield, G-value, of H2O2, I3−, Fe3+ and 4-NC ultrasonic formation was, respectively, 7.7, 19.9, 7.0 and 1.7 times higher than that of peroxynitrite production. This is probably due to the fact that ultrasound-induced peroxynitrite formation requires more energy than the products of the various dosimetries tested. Ultrasonic peroxynitrite formation experiments conducted at frequencies of 585, 860 and 1140 kHz demonstrate that the product generation is directly related to the ultrasound frequency. The amount of peroxynitrite formed at 585 kHz is greater than that formed at 860 kHz and 1140 kHz for a given density of ultrasonic energy. By comparing the results of this work obtained at frequencies of 516, 585, 860 and 1140 kHz with those published in the only paper available in the literature on the sonochemical formation of peroxynitrite (321 kHz), it can be confirmed that as the frequency of ultrasonic waves increases, the formation of peroxynitrite decreases. The same tendency of frequency dependence observed for peroxynitrite formation was found for all chemical dosimetries tested. The impact of ultrasonication power on peroxynitrite formation by sonication at different frequencies in the interval 585–1140 kHz was investigated. At lower acoustic power, no peroxynitrite was produced regardless of frequency. As the frequency increases, a greater amount of energy is required for the production of peroxynitrite. In spite of the ultrasonic frequency, peroxynitrite formation increased with increasing acoustic power. Thus, peroxynitrite formation by sonolysis is highly dependent on the ultrasonic power.

Since peroxynitrite is homogenously dispersed in the bulk solution, a solute susceptible to the powerful oxidant peroxynitrite can be sonochemically transformed not only in the immediate vicinity of the cavitation bubble, but also in the bulk of the solution. All sonochemical results, especially those performed at higher pH, should take into account the formation of peroxynitrite. Additionally, the production of peroxynitrite in alkaline solution (pH 12) by sonolysis can be considered as a chemical dosimeter in sonochemistry.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hamza Ferkous: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Oualid Hamdaoui: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Christian Pétrier: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, “Ministry of Education” in Saudi Arabia for funding this research (IFKSUOR3–027–1).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Suslick K.S., Didenko Y., Fang M.M., Hyeon T., Kolbeck K.J., McNamara W.B., Mdleleni M.M., Wong M. Acoustic cavitation and its chemical consequences. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A. 1999;357(1751):335–353. doi: 10.1098/rsta.1999.0330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Didenko Y.T., McNamara W.B., Suslick K.S. Hot spot conditions during cavitation in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:5817–5818. doi: 10.1021/ja9844635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adewuyi Y.G. Sonochemistry: environmental science and engineering applications. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001;40:4681–4715. doi: 10.1021/ie010096l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Theoretical estimation of the temperature and pressure within collapsing acoustical bubbles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann M.R., Hua I., Höchemer R. Application of ultrasonic irradiation for the degradation of chemical contaminants in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1996;3:S163–S172. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(96)00022-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerboua K., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Alghyamah A., Islam M.H., Hansen H.E., Pollet B.G. How do dissolved gases affect the sonochemical process of hydrogen production? An overview of thermodynamic and mechanistic effects On the “hot spot theory”. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;72 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105422. 105422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Saoudi F., Chiha M., Pétrier C. Influence of bicarbonate and carbonate ions on sonochemical degradation of Rhodamine B in aqueous phase. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;175:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood R.J., Lee J., Bussemaker M.J. A parametric review of sonochemistry: control and augmentation of sonochemical activity in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;38:351–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamdaoui O., Kerboua K. 1st ed. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2022. Energy aspects of acoustic cavitation and sonochemistry: fundamentals and engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrier C., Lamy M.-F., Francony A., Benahcene A., David B., Renaudin V., Gondrexon N. Sonochemical degradation of phenol in dilute aqueous solutions: comparison of the reaction rates at 20 and 487 kHz. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98(41):10514–10520. [Google Scholar]

- 11.O. Hamdaoui, S. Merouani, M. Ait Idir, H.C. Benmahmoud, A. Dehane, A. Alghyamah, Ultrasound/chlorine sono-hybrid-advanced oxidation process: impact of dissolved organic matter and mineral constituent, Ultrason. Sonochem. 83 (2022) 105918, doi:10.1016/J.ULTSONCH.2022.105918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Dharmarathne L., Ashokkumar M., Grieser F. On the generation of the hydrated electron during the sonolysis of aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2013;117:2409–2414. doi: 10.1021/jp312389n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colussi A.J., Weavers L.K., Hoffmann M.R. Chemical bubble dynamics and quantitative sonochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:6927–6934. doi: 10.1021/jp980930t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henglein A. Chemical effects of continuous and pulsed ultrasound in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1995;2:115–121. doi: 10.1016/1350-4177(95)00022-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henglein A. Sonochemistry: historical developments and modern aspects. Ultrasonics. 1987;25:6–16. doi: 10.1016/0041-624X(87)90003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart E.J., Henglein A. Free radical and free atom reactions in the sonolysis of aqueous iodide and formate solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:4342–4347. doi: 10.1021/j100266a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson L.H., Doraiswamy L.K. Sonochemistry: science and engineering, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999;38:1215–1249. doi: 10.1021/ie9804172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buxton G.V., Greenstock C.L., Helman W.P., Ross A.B., Buxton G.V., Greenstock C.L., Helman P., Ross A.B. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O-) in aqueous solution. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1988;17:513–886. doi: 10.1063/1.555805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pétrier C., Francony A. Ultrasonic waste-water treatment: incidence of ultrasonic frequency on the rate of phenol and carbon tetrachloride degradation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1997;4:295–300. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(97)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Kerabchi N. On the sonochemical production of nitrite and nitrate in water: a computational study. Water Eng. Model. Math. Tools. 2021:429–452. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-820644-7.00017-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Supeno, Kruus P. Sonochemical formation of nitrate and nitrite in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2000;7(3):109–113, doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(99)00043-7. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(99)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwedi-Nsah L.-M., Kobayashi T. Sonochemical nitrogen fixation for the generation of NO2− and NO3− ions under high-powered ultrasound in aqueous medium 105051 Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;66:105051. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mark G., Schuchmann H.P., Von Sonntag C. Formation of peroxynitrite by sonication of aerated water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:3781–3782. doi: 10.1021/ja9943391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vásquez-Vivar J., Denicola A., Radi R., Augusto O. Peroxynitrite-mediated decarboxylation of pyruvate to both carbon dioxide and carbon dioxide radical anion. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:786–794. doi: 10.1021/tx970031g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beckman J.S., Beckman T.W., Chen J., Marshall P.A., Freeman B.A. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radi R. Oxygen radicals, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite: redox pathways in molecular medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018;115:5839–5848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804932115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koda S., Kimura T., Kondo T., Mitome H. A standard method to calibrate sonochemical efficiency of an individual reaction system. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003;10:149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(03)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Saoudi F., Chiha M. Influence of experimental parameters on sonochemistry dosimetries: KI oxidation, Fricke reaction and H2O2 production. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;178:1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Juboori R.A., Yusaf T., Bowtell L., Aravinthan V. Energy characterisation of ultrasonic systems for industrial processes. Ultrasonics. 2015;57:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason T.J., Lorimer J.P., Bates D.M. Quantifying sonochemistry: casting some light on a ‘black art’. Ultrasonics. 1992;30:40–42. doi: 10.1016/0041-624X(92)90030-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kormann M.R., Bahnemann C., Hoffmann D.W. Photocatalytic production of H2O2 and organic peroxides in aqueous suspensions of TiO2, ZnO, and desert sand. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1988;22:798–806. doi: 10.1021/es00172a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pryor W.A., Cueto R., Jin X., Koppenol W.H., Ngu-Schwemlein M., Squadrito G.L., Uppu P.L., Uppu R.M. A practical method for preparing peroxynitrite solutions of low ionic strength and free of hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;18:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00105-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack J., Bolton J.R. Photochemistry of nitrite and nitrate in aqueous solution: a review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1999;128:1–13. doi: 10.1016/S1010-6030(99)00155-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang X.-F., Guo X.-Q., Zhao Y.-B. Development of a novel rhodamine-type fluorescent probe to determine peroxynitrite. Talanta. 2002;57:883–890. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(02)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha A., Goldstein S., Cabelli D., Czapski G. Determination of optimal conditions for synthesis of peroxynitrite by mixing acidified hydrogen peroxide with nitrite. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998;24:653–659. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kissner R., Nauser T., Bugnon P., Lye P.G., Koppenol W.H. Formation and properties of peroxynitrite as studied by laser flash photolysis, high-pressure stopped-flow technique, and pulse radiolysis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:1285–1292. doi: 10.1021/TX970160X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen J.L., Miller B.L., Zhang X., Hug G.L., Schöneich C. Oxidation of threonylmethionine by peroxynitrite. Quantification of the one-electron transfer pathway by comparison to one-electron photooxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:4749–4757. doi: 10.1021/JA964031Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iida Y., Yasui K., Tuziuti T., Sivakumar M. Sonochemistry and its dosimetry. Microchem. J. 2005;80:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2004.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tauber A., Schuchmann H.P., Von Sonntag C. Sonolysis of aqueous 4-nitrophenol at low and high pH. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2000;7:45–52. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(99)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang X., Mark G., von Sonntag C. OH radical formation by ultrasound in aqueous solutions Part I: the chemistry underlying the terephthalate dosimeter. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1996;3:57–63. doi: 10.1016/1350-4177(95)00032-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mark G., Tauber A., Laupert R., Schuchmann H.P., Schulz D., Mues A., Von Sonntag C. OH-radical formation by ultrasound in aqueous solution - Part II: Terephthalate and Fricke dosimetry and the influence of various conditions on the sonolytic yield. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1998;5:41–52. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(98)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Entezari M.H., Kruus P., Otson R. The effect of frequency on sonochemical reactions III: dissociation of carbon disulfide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1997;4:49–54. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(96)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutierrez M., Henglein A., Ibanez F. Radical scavenging in the sonolysis of aqueous solutions of iodide, bromide, and azide. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:6044–6047. doi: 10.1021/j100168a061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lymar S., Hurst J.K., Wishart J. Reactivity of peroxynitrite: implications for Hanford waste management and remediation. 1999 doi: 10.2172/834603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.A. Dehane, S. Merouani, O. Hamdaoui, M. Ashokkumar, An alternative technique for determining the number density of acoustic cavitation bubbles in sonochemical reactors,Ultrason. Sonochem. 82 (2022), 105872, doi:10.1016/J.ULTSONCH.2021.105872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Sensitivity of free radicals production in acoustically driven bubble to the ultrasonic frequency and nature of dissolved gases. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;22:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merouani S., Ferkous H., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. A method for predicting the number of active bubbles in sonochemical reactors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;22:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francony A., Pétrier C. Sonochemical degradation of carbon tetrachloride in aqueous solution at two frequencies: 20 kHz and 500 kHz. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1996;3:S77–S82. doi: 10.1016/1350-1477(96)00010-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pétrier C., Francony A. Ultrasonic waste-water treatment: incidence of ultrasonic frequency on the rate of phenol and carbon tetrachloride degradation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1997;4(4):295–300. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(97)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferkous H., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Pétrier C. Persulfate-enhanced sonochemical degradation of naphthol blue black in water: evidence of sulfate radical formation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:580–587, doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.06.027. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanthale P., Ashokkumar M., Grieser F. Sonoluminescence, sonochemistry (H2O2 yield) and bubble dynamics: Frequency and power effects. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Juboori R.A., Yusaf T., Bowtell L. Energy conversion efficiency of pulsed ultrasound. Energy Procedia. 2015;75:1560–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gasmi I., Hamdaoui O., Ferkous H., Alghyamah A. Sonochemical advanced oxidation process for the degradation of furosemide in water: effects of sonication’s conditions and scavengers,Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;95:106361. doi: 10.1016/J.ULTSONCH.2023.106361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Renaudin V., Gondrexon N., Boldo P., Pétrier C., Bernis A., Gonthier Y. Method for determining the chemically active zones in a high-frequency ultrasonic reactor. Ultrason. - Sonochem. 1994;1:3–7. doi: 10.1016/1350-4177(94)90002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamdaoui O., Naffrechoux E. Sonochemical and photosonochemical degradation of 4-chlorophenol in aqueous media. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15:981–987. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Energy analysis during acoustic bubble oscillations: relationship between bubble energy and sonochemical parameters. Ultrasonics. 2014;54:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferkous H., Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Comprehensive experimental and numerical investigations of the effect of frequency and acoustic intensity on the sonolytic degradation of naphthol blue black in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;26:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Effects of ultrasound frequency and acoustic amplitude on the size of sonochemically active bubbles-theoretical study. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20:815–819. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.