Abstract

Tumor cells metastasize to distant organs mainly via hematogenous dissemination, in which circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are relatively vulnerable, and eliminating these cells has great potential to prevent metastasis. In vasculature, natural killer (NK) cells are the major effector lymphocytes for efficient killing of CTCs under fluid shear stress (FSS), which is an important mechanical cue in tumor metastasis. However, the influence of FSS on the cytotoxicity of NK cells against CTCs remains elusive. We report that the death rate of CTCs under both NK cells and FSS is much higher than the combined death induced by either NK cells or FSS, suggesting that FSS may enhance NK cell's cytotoxicity. This death increment is elicited by shear-induced NK activation and granzyme B entry into target cells rather than the death ligand TRAIL or secreted cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ. When NK cells form conjugates with CTCs or adhere to MICA-coated substrates, NK cell activating receptor NKG2D can directly sense FSS to induce NK activation and degranulation. These findings reveal the promotive effect of FSS on NK cell's cytotoxicity toward CTCs, thus providing new insight into immune surveillance of CTCs within circulation.

INTRODUCTION

Tumor metastasis accounts for >90% of cancer-related deaths.1,2 The sequential steps of metastasis involve the detachment of a subpopulation of tumor cells from a primary tumor, invasion through the surrounding tissue, intravasation and survival in the vascular system, and extravasation into and generation of secondary tumors at distal sites. A failure at any step can undermine the successful establishment of metastatic tumors. Various rate limiting factors challenge the fate of disseminated tumor cells and the efficiency of the metastasis process (e.g., <0.01%).3,4 Upon entry into the vasculature, CTCs experience multiple environmental stresses, such as anoikis, FSS, oxidative stress, and immune surveillance.1,5 Only a small subpopulation of CTCs survive under these stresses to seed metastasis. The frequency of CTCs in vasculature is correlated with the prognosis and survival of cancer patients.6,7 Therefore, unveiling the combined effects of these critical factors on the survival of CTCs during hematogenous dissemination is important to facilitate the development of new therapeutic strategies for eradicating CTCs and preventing metastasis.

Physiological FSS varies according to locations (capillaries, veins, or arteries), ranging from 1 to 30 dyn/cm2.8 The influence of FSS on the survival of CTCs has been extensively investigated. For example, we have found that FSS eliminates the majority of suspended tumor cells in a magnitude- and time-dependent manner.9,10 Shear-induced cell death can be attributed to the elevated cell membrane damage,11 oxidative level,12 and sensitivity to cytokine-induced apoptosis.13 Nevertheless, certain tumor cells exhibit resistance to FSS-induced damage. For example, actomyosin is believed to be responsible for the survival of a subpopulation of CTCs in blood shear stress.9,11 Our previous research shows that CTCs can survive FSS-induced destruction through histone acetylation-mediated nuclear expansion.14 Furthermore, FSS can also promote the malignant functions of CTCs. For example, FSS facilitates epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT),10,15 stemness,16 and drug resistance of tumor cells in suspension.17

Immune system plays a major role in eliminating tumor cells at every step of tumor metastasis.18 Since the duration of CTCs in vasculature is relatively short (with a half-life of 1–2.4 h),5,19–21 effective killing of these tumor cells through immune responses requires direct and quick recognition and cytotoxicity. NK cells are an important part of the innate immune system and function as the major eliminator of CTCs because they can rapidly recognize and kill malignant cells through germ-line encoded activating receptors.22,23 The number and activation of NK cells are highly associated with the survival of cancer patients.24–27 The majority of NK cells in vasculature are CD56dim subtype that has robust cytotoxicity with relatively low cytokine secretion ability compared with CD56bright subtype.28–30 After conjugate formation through integrins like LFA-1,31,32 NK cells can be activated through the interaction with activating ligands, such as MICA/B and ULBP1–6, which directly induce target cell death by secreting perforin to form pores in target cell membrane and transport granzymes.33–42 In addition, NK cells can kill target cells through the death receptor ligand TRAIL43,44 and cytokines, such as TNF-α45,46 and IFN-γ.47–49

Recent evidence shows that mechanical cues, such as substrate stiffness and the membrane tension of target cells, have significant effect on NK cell functions. For example, fast actin dynamics regulate SHP-1 conformation and activity and promote NK cell activation.50 NK cells generate about 10 pN contractile force on MICA-coated nanowires, which is required for their activation.51 NK cells on MICA-coated substrates show stiffness-dependent activation and are most activated on 150 kPa surface that is much stiffer than normal human tissues.52 NK cells on NKp30 and anti-LFA-1 coated surface or beads secrete more cytokines and granzymes on stiff surfaces (142 kPa) or beads (264 kPa).53 NKG2D can discriminate different ligands through mechanically regulated ligand conformational changes using the biomembrane force probe and molecular dynamics,54 suggesting that NKG2D may be a potential mechanosensor.

In vasculature, CTCs are exposed to both NK cells and FSS simultaneously. However, their synergistic effects on the survival of CTCs remain unclear. In particular, whether FSS can influence NK cell's cytotoxicity against CTCs is still unknown. This study investigated the influence of FSS in vasculature on NK cell's cytotoxicity toward CTCs in a microfluidic system. The mechanisms underlying shear-dependent cytotoxicity were dissected, including NK secreted cytokines and granzyme B. Furthermore, the roles of NKG2D in shear-induced degranulation, NK activation, and the mediated cell death were examined. The mechanosensitivity of NKG2D in response to FSS was tested and the influence of FSS on NKG2D-mediated mechanosensing was explored.

RESULTS

FSS enhances NK cell's cytotoxicity toward CTCs

To study the effect of FSS on NK cell's cytotoxicity, breast cancer cells in suspension were utilized to mimic CTCs and circulated with NK cells at the ratio of 1:4 under multiple levels of FSS (0, 1, 5, 10, and 20 dyn/cm2) within a microfluidic device.9 We found that 10 and 20 dyn/cm2 FSS induced substantial death of NK cells [Fig. S1(a)]. Thus, only 1 and 5 dyn/cm2 FSS were utilized in the rest of the study. Tumor cells exhibited a shear-dependent death response both with and without the co-culture with NK cells [Fig. 1(a)]. Importantly, the lysis ratio of tumor cells under both NK cells and FSS was much higher than the combined death induced by either NK cells or FSS, represented by the incremental lysis [Fig. 1(b), red bar]. In particular, under 5 dyn/cm2 FSS, the incremental lysis was more than twofold of that induced by NK cells [Fig. 1(c)], while this effect was negligible at 1 dyn/cm2. This indicates the reciprocal interaction between FSS and NK cells. Similarly, we also observed a shear-dependent caspase-3 activation and increment of caspase activity [Figs. 1(d) and 1(e)] in tumor cells, which might partially explain the shear-dependent lysis response [Figs. 1(a)–1(c)]. All the shear stresses above referred to the stress on the tubing wall. The shear stress distribution within the tubing depended on the radial position. Therefore, it was challenging to determine the exact FSS experienced by individual tumor cells. To validate this shear-induced response, suspended tumor cells were adhered to a poly-D-lysine (PDL)-coated chip and then treated with or without NK cells that were in suspension under 0, 0.1, and 0.2 dyn/cm2 FSS, respectively. In this scenario, all PDL-adhered tumor cells and the conjugated NK cells experienced a similar level of FSS on the chip, while suspended NK cells were circulated under the indicated wall shear stress that had minimal effect on their viability [Fig. S1(a)]. These PDL-adhered tumor cells showed as similar cytoskeleton, morphology, and focal adhesion as suspended cells under FSS [Figs. S1(b)–S1(g)]. The shear-dependent overall and incremental cell deaths of PDL-adhered tumor cells [Figs. 1(f), 1(g), and S1(h)] were similar to those of suspended tumor cells in the microfluidic tube [Figs. 1(a)–1(d)]. Taken together, these findings suggest that FSS within the vasculature can promote NK cell's cytotoxicity against CTCs.

FIG. 1.

FSS enhances NK cell cytotoxicity toward breast CTCs. (a) Lysis ratio of MDA-MB-231 under 0, 1, and 5 dyn/cm2 FSS with or without NK92 co-culturing. n = 4 independent experiments. (b) Lysis ratio of MDA-MB-231 under no treatment (spontaneous), FSS (5 dyn/cm2), NK92, and FSS (5 dyn/cm2) and NK92. n = 6 independent experiments. (c) Normalized increment of tumor cell death at 0, 1, and 5 dyn/cm2 FSS. n = 4 independent experiments. Lysis ratio (LR) of tumor cells was calculated by ; the increment was calculated by ; the normalized increment was calculated by . (d) The percentage of caspase-3+ tumor cells under different magnitudes of FSS with or without NK92 co-culturing. n = 4 independent experiments. (e) Increment of caspase-3 activation at 0, 1, 5 dyn/cm2 FSS. n = 4 independent experiments. (f) Apoptotic ratio of MDA-MB-231 cells at 0, 0.1, and 0.2 dyn/cm2 FSS with or without NK92 co-culturing, indicated by the percentage of cells positive for propidium iodide (PI+). n = 3 independent experiments. (g) Increment of tumor cell death at 0, 0.1, and 0.2 dyn/cm2 FSS. n = 3 independent experiments. All the results were presented as mean ± SEM. The one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test was adopted for statistical analysis. NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; and ****p < 0.0001.

FSS promotes the entry of granzyme B into target cells

The major way by which NK cells kill CTCs is by forming conjugates with target cells, secreting perforin through the immune synapse to form pores on the cell membrane, and delivering the major effector enzyme granzyme B.39–42,55 To elucidate how FSS enhanced NK cell's cytotoxicity, we first tested the influence of FSS on conjugate formation. The results showed that the conjugate formation between tumor cells and NK cells decreased along with the increase in FSS [Fig. 2(a)], which might result from shear-mediated disturbance. Nevertheless, there were more apoptotic cells in the formed conjugates under higher FSS [Fig. 2(b)]. Furthermore, the expression of CD107a, a known marker of NK cell activity, significantly increased at 5 dyn/cm2 FSS [Fig. 2(c)], suggesting the shear-induced activation of NK cells. Microtubule organizing center (MTOC) of NK cells is responsible for the directed delivery of lytic granules.41,56,57 The distance between MTOC and the synapse decreased along with the increase in FSS [Fig. 2(d)], indicating the shear-dependent MTOC polarization. Under 5 dyn/cm2 FSS, the MTOCs were much closer to the synapses [Fig. 2(d)], suggesting the activation of the conjugated NK cells. As a consequence, more granzyme B was delivered into the conjugated MDA-MB-231 cells under 5 dyn/cm2 FSS [Figs. 2(e) and S2(g)], which might explain the enhanced NK cell's cytotoxicity toward CTCs.

FIG. 2.

FSS promotes the entry of granzyme B into target cells. (a) Conjugate formation ratio between NK92 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells under different levels of FSS. n = 4 independent experiments. (b) The percentage of PI+ MDA-MB-231 cells within tumor cell-NK conjugates. n = 4 independent experiments. (c) The relative intensity of CD107a in NK cells co-cultured with tumor cells under different levels of FSS. n = 3 independent experiments. (d) MTOC polarization under different FSS represented by the distance between MTOC and the immunological synapse. n = 57, 46, and 59 cells for 0, 1, and 5 dyn/cm2 FSS. Scale bar: 10 μm. (e) The percentage of Granzyme B+ MDA-MB-231 after co-culturing with NK92 under different FSS. The representative flow cytometry images were shown on the right panel. n = 4 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (a)–(c) and (e) and Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's test (d). NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; and ****p < 0.0001.

Alternatively, NK cells can also induce tumor cell death via secreting cytokines, including TNF-α45,46 and IFN-γ,47–49 and via tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL).13,41,58,59 To investigate the roles of these mechanisms, the influence of FSS and tumor cells on the secretion of TNF-α and IFN-γ in NK cells was examined. There was no significant difference in TNF-α secretion when different levels of FSS were exerted with and without tumor cells [Fig. S2(a)]. Interestingly, the secreted IFN-γ decreased at 1 and 5 dyn/cm2 FSS compared to 0 dyn/cm2 [Fig. S2(c)]. These findings suggest that FSS does not promote the secretion of TNF-α and IFN-γ. This might be because cytokine secretion is different from cytotoxic granules secretion in NK cells.60 We further tested the cytotoxic effect of these cytokines under FSS. To treat MDA-MB-231 cells with or without FSS, 30 pg/mL TNF-α or 70 pg/mL IFN-γ was used. The results showed that there was no difference in cell apoptosis when suspended tumor cells were circulated under FSS with or without TNF-α and IFN-γ [Figs. S2(b) and S2(D)]. Furthermore, the blocking antibody was adopted to inhibit the functions of TRAIL. However, no significant difference was observed in tumor cell death under FSS compared with control IgG [Fig. S2 (e)]. In addition, the conditioned medium was collected from the co-culture of suspended tumor cells and NK cells under FSS. There was no net increment of cell lysis under 1 and 5 dyn/cm2 FSS [Fig. S2(f)], indicating that the cytokines secreted by NK cells may not contribute to the shear-induced increase in NK cell cytotoxicity.

Taken together, FSS impairs conjugate formation between NK and tumor cells while promoting NK cell activation and the delivery of granzyme B into target cells within the conjugates, which may enhance NK cell's cytotoxicity.

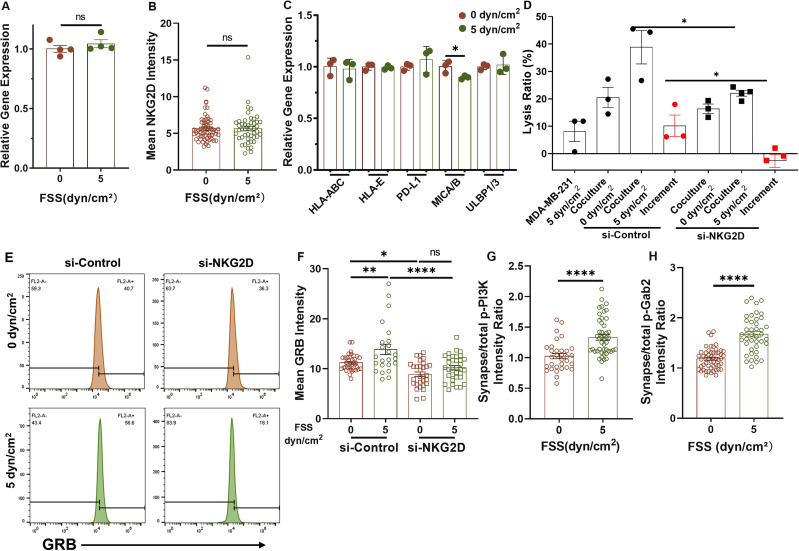

FSS promotes granzyme B entry into target cells via NKG2D

After engaging with target cells, the activity of NK cells is determined by a balance of activating and inhibitory signals.61–63 NK cells express germline-encoded receptors that recognize the corresponding ligands on the membranes of transformed cells.62 NKG2D, an important activating receptor expressed on NK cells, binds to several ligands that are structurally related to MHC class I, such as MICA, MICB, and ULBPs in humans.64–67 To test the role of NKG2D in shear-induced NK cell's cytotoxicity, we first explored the influence of FSS on the expressions of NKG2D and its ligands. Interestingly, shear treatment did not have significant impact on the mRNA and protein levels of NKG2D in NK cells [Figs. 3(a) and 3(b)] and ligands on MDA-MB-231 cells [Fig. 3(c)]. We next knocked down NKG2D in NK cells by electroporation [Fig. S3(a)] and found that silencing NKG2D significantly decreased the cytotoxicity increment under 5 dyn/cm2 FSS [Fig. 3(d)]. The amount of granzyme B in all tumor cells and the conjugated ones was remarkably elevated under FSS, which was blunted by the inhibition of NKG2D [Figs. 3(e) and 3(f)]. After ligation with MICA on target cells, PI3K and VAV1-Grb2 will be recruited to the intracellular domain of NKG2D with the help of the adaptor protein DAP1068–71 and Gab272 to transduce activating signals, which then facilitate the delivery of granzyme B into target cells. We then examined the activation of PI3K and Gab2 signaling under FSS. The shear treatment promoted the phosphorylation levels of both PI3K and Gab2 within the synapse region under 5 dyn/cm2 FSS compared with the static condition [Figs. 3(g), 3(h) and S3(b) and S3(g)]. Pharmacologic inhibition of PI3K and VAV1 (downstream of Gab2) diminished the shear-induced increase in granzyme B delivery into tumor cells [Figs. S3(c)–S3(f)]. Together, these results suggest that FSS may promote NK cell's cytotoxicity through NKG2D-mediated granzyme B injection.

FIG. 3.

FSS promotes Granzyme B entry into target cells via NKG2D. (a) and (b) The expression of NKG2D at mRNA and protein levels in NK cells after shear treatment. NK cells were treated under 0 or 5 dyn/cm2 FSS for 4 h, and then analyzed for NKG2D expression at both mRNA (a) and protein (b) levels by qPCR and immunofluorescence staining, respectively. n = 4 independent experiments in (a); n > 46 cells in (b). (c) mRNA expressions of activating/inhibitory receptors in MDA-MB-231 under 0 or 5 dyn/cm2 FSS treatment for 4 h. n = 3 independent experiments. (d) Lysis ratio of MDA-MB-231 under both NK cells and 0 or 5 dyn/cm2 FSS after knocking down NKG2D. n = 3 independent experiments. (e) and (f) Granzyme B entry into MDA-MB-231 after co-culturing with NK92 when NKG2D was knocked down under 0 or 5 dyn/cm2 FSS. MDA-MB-231 was co-cultured with NK92 that were transfected with NKG2D siRNA or negative control and then treated under 0 or 5 dyn/cm2 FSS. The amount of Granzyme B within tumor cells was measured by flow cytometry (e) and immunofluorescence staining (f) in the conjugated cells. Representative of two independent experiments in (e). n > 30 cells in (f). (g) and (h) The relative level of phosphorylated PI3K and Gab2 between the synapse and the whole NK cell after co-culturing with MDA-MB-231 under 0 and 5 dyn/cm2 FSS. n > 32 cells in (g); n > 42 cells in (h). Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-test (a), (c), and (h), Mann–Whitney U-test (b) and (g), and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (d) and (f). NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ****p < 0.0001.

NKG2D is mechanosensitive to FSS

Our findings have implicated the involvement of NKG2D in the shear-induced activation of NK cells. We further explored whether NKG2D could directly sense and respond to FSS. Toward this goal, the surface of the microfluidic chip was coated with MICA, a known ligand to interact with NKG2D. NK cells were allowed to adhere to the surface and then treated under FSS. Along with the increase in FSS, adhered NK cells showed elevated expression of CD107a on the cell membrane [Fig. 4(a)], which indicated the enhanced cytotoxicity of NK cells. However, FSS could not promote CD107a expression in NK cells that adhered to the substrates coated with ICAM-1, ligand of integrin LFA-1. These findings indicate that the shear-induced activation of NK cells may be mediated through direct NKG2D-MICA force sensing. Upon the interaction with MICA, DAP10, the adaptor of NKG2D intracellular domain, recruits Grb2-VAV1 and PI3K to promote immune synapse formation and NK cell activation.71,73 Lck has been proposed to phosphorylate both VAV174,75 and PI3K76,77 to initiate the downstream signaling. By using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensor that could measure Lck activity, we found that FSS could promote Lck activity after NK cells were conjugated with target cells. Note that high FRET ratio of the sensor represented low Lck activity. Silencing NKG2D diminished the decrease in the FRET ratio and rescued Lck activity to the control level [Fig. 4(b)]. FSS also promoted the accumulation of phosphorylated VAV1 within the immune synapse, which was fully blunted by silencing NKG2D [Fig. 4(c)]. PI3K is another kinase phosphorylated by Lck. We found that the phosphorylation of Akt, downstream of PI3K, was significantly enhanced under FSS, and this increase was rescued by knocking down NKG2D [Figs. 4(d) and S3(h)]. Furthermore, FSS could promote the MTOC polarization of NK cells after conjugating with target cells [Fig. 2(d)]. Silencing NKG2D diminished this shear-induced MTOC polarization [Figs. 4(e) and S3(i)]. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the activating receptor NKG2D can directly sense and respond to FSS by activating the downstream Lck/Grb2/VAV1/PI3K signaling after the engagement with MICA, which may promote NK cell's cytotoxicity.

FIG. 4.

NKG2D is mechanosensitive to FSS. (a) CD107a expression in NK92 cells under different FSS when adhering to chips coated with MICA or ICAM-1. n > 40 cells. (b) FRET ratio (YFP/CFP) of NK92 cells when co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells under different FSS. Higher FRET ratio represents lower Lck activity. n > 64 cells. Right: representative FRET images. (c) The effect of NKG2D on phosphorylated VAV1 within the synapse of NK92 cells when co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells under different FSS. n > 41 cells. (d) The effect of NKG2D on phosphorylated Akt level of NK92 cells when co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells under different FSS. n > 32 cells. (e) MOTC polarization in NK92 cells when co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells under different FSS after knocking down NKG2D. n > 56 cells. Statistical analysis was performed by using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's test (a), (c), and (d), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (b), and Mann–Whitney U-test (e). NS, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; and ****p < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

Tumor metastasis is a complex and inefficient process. Within the circulation system, a small subset of CTCs can survive the challenging environment, such as anchorage-dependent anoikis, oxidative stress, immune surveillance, and FSS. Less than 0.01% of these cells may eventually seed metastatic tumors.4,78 Previous studies have found that FSS can effectively eliminate CTCs in a time-dependent manner,9,10,12,79,80 which may be compromised by the short half-life of CTCs in vasculature (∼1–2.4 h).5,19–21 Furthermore, the immune system is predetermined to kill tumor cells and the eradication of CTCs within vasculature requires rapid activation of the immune responses. As an essential part of the innate immune system, NK cells function as a major effector of CTC elimination. The primary tumor microenvironment has been reported to inhibit the infiltration and cytotoxicity of NK cells.81–83 Previous studies have shown that stiff substrates promote MTOC polarization and NK cell degranulation,53 indicating the potential of mechanical stimulations in regulating NK cell function. FSS is one mechanical cue that exists at varying levels in the vasculature but at very low level in primary tumor sites. However, whether FSS can influence NK cell function is still unknown.

We report here for the first time that FSS of physiologic magnitude can promote NK cell's cytotoxicity to CTCs within a relatively short duration. It is known that NK cells can induce tumor cell death through both direct and indirect interactions. In this study, we show that FSS has no significant impact on the secretion of TNF-α and IFN-γ in NK cells and does not enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to the death induced by these cytokines, TRAIL, and the conditioned medium. This finding is different from the previous study that the death receptor ligand TRAIL can sensitize CTCs to FSS-induced cell death,13 which may be due to the fact that the amount of TRAIL secreted by NK cells is insufficient in mediating tumor cell death. Instead, FSS promotes NK cell degranulation and the delivery of granzyme B into target cells, suggesting the enhanced cytotoxicity. Thus, it is possible that one shear-activated NK cell may kill the conjugated tumor cell within a shorter time duration than a control NK cell. After efficient eradication, it may dissociate from the dead cell and continue to form conjugates with another tumor cell. Therefore, one NK cell may kill more tumor cells than one control cell within a given time duration under FSS, although shear treatment decreases the conjugate formation. Importantly, shear-induced NK activation is mediated by the mechanosensing of NKG2D-MICA interaction, inhibition of which abolishes the incremental effect of FSS on NK cell's cytotoxicity. Our findings provide new evidence to support that NK cells are sensitive to shear stress via NKG2D-mediated mechanotransduction, which may depend on force-induced alterations in ligand conformation.54

Previous research shows that cytotoxic T cells preferentially kill stiff tumor cells while sparing soft ones through perforin-mediated membrane pore formation.84 Malignant tumor cells are soft and enriched in cholesterol, which can protect them from cytotoxic T cell-mediated immunotherapy.85 Our previous studies find that CTCs that can survive after shear treatment exhibit much lower stiffness than control tumor cells,86 and the tumor cells selected by 3D soft fibrin are soft and malignant. These soft tumor cells may be thus more resistant to NK or T cell-mediated immune surveillance. Although FSS promotes NK cell's cytotoxicity, it is possible that a small subpopulation of CTCs with low stiffness but high resistance to both FSS and NK cells may still persist within the vasculature and eventually generate secondary lesions. Therefore, further investigation is needed to decipher the detailed survival mechanisms, which will facilitate the development of effective therapeutic strategies that can efficiently eliminate these resistant but malignant CTCs.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study reports that FSS enhances NK cell's cytotoxicity to CTCs in a shear-dependent manner. The incremental tumor cell death is attributed to the shear-induced activation of NK cells, which then deliver more granzyme B into CTCs to induce apoptosis, while the roles of the secreted cytokines and death ligands are dispensable. Importantly, when binding to the ligand MICA, NKG2D can directly sense FSS to promote NK cell activation and cytotoxicity. Silencing NKG2D abolishes FSS-mediated NK cell activation, granzyme B entry, and the incremental death of CTCs. These findings unveil a mechanically regulated CTC killing mechanism of NK cells, which may provide a novel mechanotargeting strategy for NK cell-based immunotherapy.

METHODS

Cell culture

NK92 cell line was a kind gift from Prof. Lei Sun in Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Table I). MDA-MB-231 cell line was purchased from ATCC. NK92 cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium α (Gibco) supplemented with 12.5% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 12.5% horse bovine serum (Sigma), 0.2 mM inositol (Sigma), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 0.02 mM folic acid (Sigma), 100 U/ml recombinant IL-2 (PeproTech), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were passaged every 2–3 days using 0.25% Trypsin (Gibco). In some experiments, NK92 cells were pretreated with 50 μM PI3K inhibitor LY294002 for 30 min or with 5 μM VAV1 inhibitor Azathioprine for 3 days.

TABLE I.

Antibodies, recombinant DNAs, and reagents.

| Reagent or resource | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-human granzyme B-PE antibody | eBioscience | Cat#12-8896-42 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-human CD107a-APC antibody | BioLegend | Cat#328620 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-human γ-tubulin antibody | Abclone | Cat#A9657 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-human Phospho-PI3K antibody | Abcam | Cat#4257 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-human Phospho-Gab2 antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #3882 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-human phospho- VAV1 antibody | R&D | Cat#MAB37861 |

| Rabbit anti-human phospho-Akt antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9271 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) | Abcam | Cat#ab150113 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594) | Abcam | Cat#ab150116 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-human CD253(TRAIL) antibody | eBioscience | Cat#16-9927-82 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-human NKG2D antibody | eBioscience | Cat#14–5878-82 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLenti-Lifeact-tdTomato | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_64048 |

| mTurquoise2-Paxillin | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_176107 |

| ZapLck biosensor | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_131584 |

| psPAX2 | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_12260 |

| pMD2.G | Addgene | RRID: Addgene_12259 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| KLRK1 siRNA | Invitrogen | Cat#108247 |

| Negative control siRNA | Invitrogen | Cat#AM4641 |

| See Table S1 for primer list | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Poly-D-lysine | Gibco | Cat#A3890401 |

| Collagen type I | Sigma | Cat#C3867-1VL |

| Bovine serum albumin | VWR Life Science | Cat#0332-500G |

| DMEM | Gibco | Cat#11995081 |

| MEMα | Gibco | Cat#12561056 |

| Penicillin/streptomycin | Gibco | Cat#0378016 |

| Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%), phenol red | Gibco | Cat#25200072 |

| Opti-MEM | Gibco | Cat#31985062 |

| Puromycin | Gibco | Cat#A1113803 |

| ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI | Invitrogen | Cat#S36938 |

| Cell tracker deep red dye | Invitrogen | Cat#C34565 |

| Cell tracker green CMFDA dye | Invitrogen | Cat#C2925 |

| Recombinant human TNF alpha protein | Abcam | Cat#ab259410 |

| Recombinant human interferon gamma protein | Abcam | Cat#ab259377 |

| Human MICA protein | Acro Biosystems | Cat#MIA-H5253-100ug |

| Recombinant human ICAM-1 | PeproTech | Cat#150–05 |

| Inositol | Sigma | Cat#I7508-50G |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | Sigma | Cat#M3148-25ML |

| Folic acid | Sigma | Cat#F8758-5G |

| Recombinant IL-2 | PeproTech | Cat#200-02 |

| Horse serum | Sigma | Cat#H1270-100ML |

| Propidium iodide | Invitrogen | Cat#P1304MP |

| LY294002 | MCE | Cat#HY-10108 |

| Azathioprine | MCE | Cat#HY-B0256 |

| FBS | Gibco | Cat#A3160802 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| NK92 | ATCC | CRL-2407 |

| MDA-MB-231 | ATCC | HTB-26 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Human interferon gamma ELISA Kit | Abcam | Cat#ab100537 |

| Human TNF alpha ELISA Kit | Abcam | Cat#ab181421 |

| Software | ||

| GraphPad Prism v8.3.1 | GraphPad Software | RRID: SCR_002798 |

| ImageJ v1.41 | NIH | RRID: SCR_003070 |

| NIS-elements | Nikon | RRID:SCR_014329 |

Transfection

The plasmids of Lifeact-tdTomato, mTurquoise2-Paxillin, and Lck FRET sensor purchased from Addgene were first co-transfected into HEK-293T cells with packaging and envelope plasmids. Supernatants containing viral particles were collected 36 and 72 h after transfection and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter, and the retrieved viruses were then concentrated using PEG8000 (Beyotime). Briefly, 30 ml of filtered crude lentivirus solution was added with 7.5 ml concentrating solution (50 g PEG8000 diluted in 200 ml H2O, added with 8.766 g NaCl). The mixture was then maintained at 4 °C overnight and centrifuged at 4000 g for 30 min to obtain the condensed viral particles. For the transfection of NK92, 2 × 105 cells per well were seeded into 24-well plates and then treated with 6 μM BX795 (InvivoGen) 30 min prior to the transfection. Appropriate amount of viral supernatant was added into the well along with 8 μg/ml polybrene (Beyotime). The plates were centrifuged at 1000 g for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 4–6 h. Then the virus-containing supernatant was removed and replaced by fresh growth medium. For the transfection of MDA-MB-231 cells, 2 × 105 cells per well were seeded into 24-well plates one day before transfection. Appropriate amount of viral supernatant was added into the well along with 8 μg/ml polybrene. After 6 h, virus-containing supernatant was removed and fresh growth medium was added. Virus transfection was validated by BD FACSAria III Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences) and the transfected cells were enriched through selective drug treatment.

For the knockdown experiments, NK92 cells were transfected with siNRA (Invitrogen) targeting KLRK1 using Gene Pulser Xcell Electroporation Systems (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 10 nM siRNA was added into NK92 cell suspension with a cell concentration of 1.5 × 106/ml. Electroporation was conducted under 150 μF plus 300 V for 3 pulses. After 48 h, the knockdown efficiency was validated by qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence staining.

Shear stress treatment

The in vitro circulation system mainly included a peristaltic pump (P-230, Harvard Instruments, Holliston, MA, USA), a silicone microtube (diameter 0.51 mm, length 1.5 m), and a 1 ml syringe used as a reservoir for the cell solution. This system produced pulsatile flow that could simulate FSS in the blood circulation. In accordance with Poiseuille's law, the wall shear stress (dyn/cm2) in the tubing was calculated as τ = 4μQ/( R3) where Q is the flow rate (from 0.001 to 230 ml/min), and μ is the liquid dynamic viscosity (0.01 dyn/cm2 for cell culture media), and R is the radius of the tube (0.255 mm). The entire system was sterilized with 75% ethanol and then rinsed with 4 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (HyClone) before the experiment. To avoid the attachment of suspended cells to the tubes and syringes, the system was pretreated with 1% bovine serum albumin (VWR Life Science). For FSS treatment, 1 ml cell suspension was added into the circulation system and subjected to different magnitudes of shear stress for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

In some experiments, cells were adhered to a microfluidic chip coated with poly-D-lysin (Gibco), ICAM-1 (PeproTech), or MICA (Acro Biosystems), which was connected with the above circulation system. The cells were then treated with FSS.

Cytotoxicity assay

To measure the cytotoxicity of NK92 against suspended MDA-MB-231 cells, these two cell types were labeled with deep red (Invitrogen) and green cell tracker (Invitrogen) before co-culturing, respectively. MDA-MB-231 cells were detached from cell culture dish with 0.25%Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) and resuspended with full medium of MEMα. NK92 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells were then co-cultured at the ratio of 4:1 (total 1 × 106 cells) for 4 h at static condition or under FSS treatment. MDA-MB-231 cells alone under static condition or under FSS were set as control groups. After co-culturing, all the cells were collected and propidium iodide (Invitrogen) was added to detect dead tumor cells. Lysis ratio (LR) of target cells was detected using BD Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) before and after co-culturing and calculated by

| (1) |

The increment was calculated by

| (2) |

The normalized increment was calculated by

| (3) |

Target cell death was also indicated by caspase-3 activation ratio among total MDA-MB-231 cells after FSS treatment. Then, 5 μM caspase-3 substrate (Beyotime) was added to cell suspension and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Then caspase-3 activation was detected by fluorescent imaging. The increment of caspase-3 positive ratio was calculated according to the formula (2).

ELISA assay

The ELISA of TNF-α (Abcam) and IFN-γ (Abcam) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantification was performed after collection of supernatants.

qRT-PCR

To analyze gene expression, cells were centrifuged and then total RNAs were extracted using Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA quality was measured and quantified using NanoDrop™ (Thermo). Complementary DNA was synthesized using Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using RR036A PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TaKaRa) and CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). The primers were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database and are listed in the supplementary material, Table I. For data analysis, the expressions of all genes were normalized using the ΔΔcycle threshold method against human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Microscope imaging and image analysis

For immunofluorescence staining, tumor cells and NK92 cells after various treatments were collected and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution (PFA) (Thermo Scientific™) for 15 min. Next, 0.1% Triton X-100 (SAFC) in 1% BSA solution was used to block and permeabilize the cells for 30 min at room temperature. After washing for three times, cells were stained with Granzyme B-PE (eBioscience), CD107a-APC (BioLegend) directly, or the first antibody: γ-tubulin (Abclone), phospho-PI3K (Abcam), phospho-Gab2(Abcam), phospho-VAV1 (Abcam), phospho-Akt (Abcam) at 4 °C overnight, and then stained with the corresponding secondary antibody: goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (Abcam) and goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594) (Abcam) at room temperature for 1 h. Cells were washed with PBS for three times and immersed in ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). At least 50 cells/condition were imaged by Leica TCS SPE confocal microscope. ImageJ (NIH) was utilized to analyze the fluorescence intensity.

For the FRET experiment, the images were collected with a 420DF20 excitation filter, a 450DRLP dichroic mirror, and two emission filters controlled by a filter changer (472/30 for CFP and 542/27 for FRET). The pixel-wise images of the YFP/CFP ratio were computed to quantify the FRET signals, which represent the Lck activity. A Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope (Nikon H550L) with a camera (ANDOR, Zyla sCMOS) and a 60×/1.40 oil Nikon objective was used to capture and analyze all images with NIS4.1.2 software.

Flow cytometry

The amount of granzyme B in tumor cells was analyzed using flow cytometry. MDA-MB-231 and NK92 were labeled with green and deep red cell tracker, respectively. After co-culturing, cells were fixed and permeabilized as mentioned above. Then granzyme B-PE antibody was used to stain granzyme B in MDA-MB-231 cells. After washing with PBS for three times, the granzyme B level was analyzed using BD Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using FlowJo_v10.6.2.

Statistical analysis

All the results were presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). The statistics between two conditions and among three or more conditions were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) if the required conditions were fulfilled (e.g., the samples assumed normal distribution), or by Mann–Whitney U-test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA if otherwise.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See the supplementary material that includes a list of PCR primers and three supplementary figures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the University Life Science Facility at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University for providing the confocal laser scanning microscopy and flow cytometry facility. We acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 11972316), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (Project Nos. JCYJ20200109142001798, SGDX2020110309520303, and JCYJ20220531091002006), the General Research Fund of Hong Kong Research Grant Council (PolyU 15214320), the Health and Medical Research Fund (18191421), and the internal grant from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (1-ZE2M, 1-CD75, and 1-ZVY1).

AUTHOR DECLARATIONS

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval is not required.

Author Contributions

Bing Hu: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Investigation (lead); Methodology (lead); Writing – original draft (equal). Ying Xin: Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal). Guanshuo Hu: Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal). Keming Li: Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal). Youhua Tan: Conceptualization (lead); Funding acquisition (lead); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Supervision (lead); Writing – original draft (lead); Writing – review & editing (lead).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1. Chaffer C. L. and Weinberg R. A., “ A perspective on cancer cell metastasis,” Science 331, 1559–1564 (2011). 10.1126/science.1203543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., and Jemal A., “ Cancer statistics, 2016,” Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 66, 7–30 (2016). 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gonzalez H., Robles I., and Werb Z., “ Innate and acquired immune surveillance in the postdissemination phase of metastasis,” FEBS J. 285, 654–664 (2018). 10.1111/febs.14325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Micalizzi D. S., Maheswaran S., and Haber D. A., “ A conduit to metastasis: Circulating tumor cell biology,” Genes Dev. 31, 1827–1840 (2017). 10.1101/gad.305805.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wirtz D., Konstantopoulos K., and Searson P. C., “ The physics of cancer: The role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis,” Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 512–522 (2011). 10.1038/nrc3080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nagrath S., Sequist L. V., Maheswaran S., Bell D. W., Irimia D., Ulkus L., Smith M. R., Kwak E. L., Digumarthy S., Muzikansky A. et al. , “ Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology,” Nature 450, 1235–1239 (2007). 10.1038/nature06385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Massagué J. and Obenauf A. C., “ Metastatic colonization by circulating tumour cells,” Nature 529, 298–306 (2016). 10.1038/nature17038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Papaioannou T. G. and Stefanadis C., “ Vascular wall shear stress: Basic principles and methods,” Hellenic J. Cardiol. 46, 9–15 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xin Y., Chen X., Tang X., Li K., Yang M., Tai W. C.-S., Liu Y., and Tan Y., “ Mechanics and actomyosin-dependent survival/chemoresistance of suspended tumor cells in shear flow,” Biophys. J. 116, 1803–1814 (2019). 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xin Y., Li K., Yang M., and Tan Y., “ Fluid shear stress induces EMT of circulating tumor cells via JNK signaling in favor of their survival during hematogenous dissemination,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8115 (2020). 10.3390/ijms21218115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moose D. L., Krog B. L., Kim T.-H., Zhao L., Williams-Perez S., Burke G., Rhodes L., Vanneste M., Breheny P., Milhem M. et al. , “ Cancer cells resist mechanical destruction in circulation via RhoA/actomyosin-dependent mechano-adaptation,” Cell Rep. 30, 3864–3874 (2020). 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma S., Fu A., Chiew G. G. Y., and Luo K. Q., “ Hemodynamic shear stress stimulates migration and extravasation of tumor cells by elevating cellular oxidative level,” Cancer Lett. 388, 239–248 (2017). 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitchell M. J. and King M. R., “ Fluid shear stress sensitizes cancer cells to receptor-mediated apoptosis via trimeric death receptors,” New J. Phys. 15, 015008 (2013). 10.1088/1367-2630/15/1/015008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu Z., Li K., Xin Y., Tang K., Yang M., Wang G., and Tan Y., “ Fluid shear stress regulates the survival of circulating tumor cells via nuclear expansion,” J. Cell Sci. 135, jcs259586 (2022). 10.1242/jcs.259586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Choi H. Y., Yang G. M., Dayem A. A., Saha S. K., Kim K., Yoo Y., Hong K., Kim J. H., Yee C., Lee K. M., and Cho S. G., “ Hydrodynamic shear stress promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition by downregulating ERK and GSK3β activities,” Breast Cancer Res. 21, 6 (2019). 10.1186/s13058-018-1071-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Triantafillu U. L., Park S., Klaassen N. L., Raddatz A. D., and Kim Y., “ Fluid shear stress induces cancer stem cell-like phenotype in MCF7 breast cancer cell line without inducing epithelial to mesenchymal transition,” Int. J. Oncol. 50, 993–1001 (2017). 10.3892/ijo.2017.3865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Triantafillu U. L., Park S., and Kim Y., “ Fluid shear stress induces drug resistance to doxorubicin and paclitaxel in the breast cancer cell line MCF7,” Adv. Ther. 2, 1800112 (2019). 10.1002/adtp.201800112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitamura T., Qian B. Z., and Pollard J. W., “ Immune cell promotion of metastasis,” Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 73–86 (2015). 10.1038/nri3789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meng S., Tripathy D., Frenkel E. P., Shete S., Naftalis E. Z., Huth J. F., Beitsch P. D., Leitch M., Hoover S., Euhus D. et al. , “ Circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer dormancy,” Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 8152–8162 (2004). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aceto N., Bardia A., Miyamoto D. T., Donaldson M. C., Wittner B. S., Spencer J. A., Yu M., Pely A., Engstrom A., and Zhu H., “ Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis,” Cell 158, 1110–1122 (2014). 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hamza B., Miller A. B., Meier L., Stockslager M., Ng S. R., King E. M., Lin L., DeGouveia K. L., Mulugeta N., Calistri N. L. et al. , “ Measuring kinetics and metastatic propensity of CTCs by blood exchange between mice,” Nat. Commun. 12, 5680 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-25917-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vivier E., Nunès J. A., and Vély F., “ Natural killer cell signaling pathways,” Science 306, 1517–1519 (2004). 10.1126/science.1103478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hashemi E. and Malarkannan S., “ Tissue-resident NK cells: Development, maturation, and clinical relevance,” Cancers 12, 1553 (2020). 10.3390/cancers12061553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu M., Mei F., Liu W., and Jiang J., “ Comprehensive characterization of tumor infiltrating natural killer cells and clinical significance in hepatocellular carcinoma based on gene expression profiles,” Biomed. Pharmacother. 121, 109637 (2020). 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cursons J., Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F., Foroutan M., Anderson A., Hollande F., Hediyeh-Zadeh S., Behren A., Huntington N. D., and Davis M. J., “ A gene signature predicting natural killer cell infiltration and improved survival in melanoma patients,” Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 1162–1174 (2019). 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barry K. C., Hsu J., Broz M. L., Cueto F. J., Binnewies M., Combes A. J., Nelson A. E., Loo K., Kumar R., Rosenblum M. D. et al. , “ A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments,” Nat. Med. 24, 1178–1191 (2018). 10.1038/s41591-018-0085-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muntasell A., Rojo F., Servitja S., Rubio-Perez C., Cabo M., Tamborero D., Costa-García M., Martínez-Garcia M., Menéndez S., Vazquez I. et al. , “ NK cell infiltrates and HLA class I expression in primary HER2+ breast cancer predict and uncouple pathological response and disease-free survival,” Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 1535–1545 (2019). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Di Vito C., Mikulak J., and Mavilio D., “ On the way to become a natural killer cell,” Front. Immunol. 10, 1812 (2019). 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quatrini L., Della Chiesa M., Sivori S., Mingari M. C., Pende D., and Moretta L., “ Human NK cells, their receptors and function,” Eur. J. Immunol. 51, 1566–1579 (2021). 10.1002/eji.202049028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Myers J. A. and Miller J. S., “ Exploring the NK cell platform for cancer immunotherapy,” Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 85–100 (2021). 10.1038/s41571-020-0426-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsumoto G., Omi Y., Lee U., Nishimura T., Shindo J., and Penninger J. M., “ Adhesion mediated by LFA-1 is required for efficient IL-12-induced NK and NKT cell cytotoxicity,” Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 3723–3731 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mace E. M., Monkley S. J., Critchley D. R., and Takei F., “ A dual role for talin in NK cell cytotoxicity: Activation of LFA-1-mediated cell adhesion and polarization of NK cells,” J. Immunol. 182, 948–956 (2009). 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu Z., Zhang H., Wu M., Peng G., He Y., Wan N., and Zeng Y., “ Targeting the NKG2D/NKG2D-L axis in acute myeloid leukemia,” Biomed. Pharmacother. 137, 111299 (2021). 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lanier L. L., “ NKG2D receptor and its ligands in host defense,” Cancer Immunol. Res. 3, 575–582 (2015). 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chiusolo V., Jacquemin G., Yonca Bassoy E., Vinet L., Liguori L., Walch M., Kozjak-Pavlovic V., and Martinvalet D., “ Granzyme B enters the mitochondria in a Sam50-, Tim22- and mtHsp70-dependent manner to induce apoptosis,” Cell Death Differ. 24, 747–758 (2017). 10.1038/cdd.2017.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chowdhury D. and Lieberman J., “ Death by a thousand cuts: Granzyme pathways of programmed cell death,” Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26, 389–420 (2008). 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thiery J., Keefe D., Saffarian S., Martinvalet D., Walch M., Boucrot E., Kirchhausen T., and Lieberman J., “ Perforin activates clathrin- and dynamin-dependent endocytosis, which is required for plasma membrane repair and delivery of granzyme B for granzyme-mediated apoptosis,” Blood 115, 1582–1593 (2010). 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brodbeck T., Nehmann N., Bethge A., Wedemann G., and Schumacher U., “ Perforin-dependent direct cytotoxicity in natural killer cells induces considerable knockdown of spontaneous lung metastases and computer modelling-proven tumor cell dormancy in a HT29 human colon cancer xenograft mouse model,” Mol. Cancer 13, 244 (2014). 10.1186/1476-4598-13-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rousalova I. and Krepela E., “ Granzyme B-induced apoptosis in cancer cells and its regulation (Review),” Int. J. Oncol. 37, 1361–1378 (2010). 10.3892/ijo_00000788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pinkoski M. J., Heibein J. A., Barry M., and Bleackley R. C., “ Nuclear translocation of granzyme B in target cell apoptosis,” Cell Death Differ. 7, 17–24 (2000). 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prager I. and Watzl C., “ Mechanisms of natural killer cell‐mediated cellular cytotoxicity,” J. Leukocyte Biol. 105, 1319–1329 (2019). 10.1002/JLB.MR0718-269R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sordo-Bahamonde C., Lorenzo-Herrero S., Payer Á. R., Gonzalez S., and López-Soto A., “ Mechanisms of apoptosis resistance to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in cancer,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3726 (2020). 10.3390/ijms21103726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takeda K., Cretney E., Hayakawa Y., Ota T., Akiba H., Ogasawara K., Yagita H., Kinoshita K., Okumura K., and Smyth M. J., “ TRAIL identifies immature natural killer cells in newborn mice and adult mouse liver,” Blood 105, 2082–2089 (2005). 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takeda K., Hayakawa Y., Smyth M. J., Kayagaki N., Yamaguchi N., Kakuta S., Iwakura Y., Yagita H., and Okumura K., “ Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in surveillance of tumor metastasis by liver natural killer cells,” Nat. Med. 7, 94–100 (2001). 10.1038/83416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Donato N. J. and Klostergaard J., “ Distinct stress and cell destruction pathways are engaged by TNF and ceramide during apoptosis of MCF-7 cells,” Exp. Cell Res. 294, 523–533 (2004). 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu Z.-G., Hsu H., Goeddel D. V., and Karin M., “ Dissection of TNF receptor 1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-κB activation prevents cell death,” Cell 87, 565–576 (1996). 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81375-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Song M., Ping Y., Zhang K., Yang L., Li F., Zhang C., Cheng S., Yue D., Maimela N. R., Qu J. et al. , “ Low-dose IFNγ induces tumor cell stemness in tumor microenvironment of non–small cell lung cancer,” Cancer Res. 79, 3737–3748 (2019). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li P., Du Q., Cao Z., Guo Z., Evankovich J., Yan W., Chang Y., Shao L., Stolz D. B., Tsung A., and Geller D. A., “ Interferon-gamma induces autophagy with growth inhibition and cell death in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells through interferon-regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1),” Cancer Lett. 314, 213–222 (2012). 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim E. J., Lee J. M., Namkoong S. E., Um S. J., and Park J. S., “ Interferon regulatory factor‐1 mediates interferon‐γ‐induced apoptosis in ovarian carcinoma cells,” J. Cell. Biochem. 85, 369–380 (2002). 10.1002/jcb.10142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Matalon O., Ben-Shmuel A., Kivelevitz J., Sabag B., Fried S., Joseph N., Noy E., Biber G., and Barda-Saad M., “ Actin retrograde flow controls natural killer cell response by regulating the conformation state of SHP-1,” EMBO J. 37, e96264 (2018). 10.15252/embj.201696264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Le Saux G., Bar-Hanin N., Edri A., Hadad U., Porgador A., and Schvartzman M., “ Nanoscale mechanosensing of natural killer cells is revealed by antigen-functionalized nanowires,” Adv. Mater. 31, 1805954 (2019). 10.1002/adma.201805954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mordechay L., Le Saux G., Edri A., Hadad U., Porgador A., and Schvartzman M., “ Mechanical regulation of the cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells,” ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 7, 122–132 (2021). 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Friedman D., Simmonds P., Hale A., Bere L., Hodson N. W., White M. R. H., and Davis D. M., “ Natural killer cell immune synapse formation and cytotoxicity are controlled by tension of the target interface,” J. Cell Sci. 134, jcs258570 (2021). 10.1242/jcs.258570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fan J., Shi J., Zhang Y., Liu J., An C., Zhu H., Wu P., Hu W., Qin R., Yao D. et al. , “ NKG2D discriminates diverse ligands through selectively mechano-regulated ligand conformational changes,” EMBO J. 41, e107739 (2022). 10.15252/embj.2021107739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Basu R., Whitlock B. M., Husson J., Le Floc'h A., Jin W., Oyler-Yaniv A., Dotiwala F., Giannone G., Hivroz C., Biais N. et al. , “ Cytotoxic T cells use mechanical force to potentiate target cell killing,” Cell 165, 100–110 (2016). 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mentlik A. N., Sanborn K. B., Holzbaur E. L., and Orange J. S., “ Rapid lytic granule convergence to the MTOC in natural killer cells is dependent on dynein but not cytolytic commitment,” Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2241–2256 (2010). 10.1091/mbc.e09-11-0930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Orange J. S., “ Formation and function of the lytic NK-cell immunological synapse,” Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 713–725 (2008). 10.1038/nri2381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yuan X., Gajan A., Chu Q., Xiong H., Wu K., and Wu G. S., “ Developing TRAIL/TRAIL death receptor-based cancer therapies,” Cancer Metastasis Rev. 37, 733–748 (2018). 10.1007/s10555-018-9728-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Carneiro B. A. and El-Deiry W. S., “ Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy,” Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 395–417 (2020). 10.1038/s41571-020-0341-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reefman E., Kay J. G., Wood S. M., Offenhäuser C., Brown D. L., Roy S., Stanley A. C., Low P. C., Manderson A. P., and Stow J. L., “ Cytokine secretion is distinct from secretion of cytotoxic granules in NK cells,” J. Immunol. 184, 4852–4862 (2010). 10.4049/jimmunol.0803954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huntington N. D., Cursons J., and Rautela J., “ The cancer–natural killer cell immunity cycle,” Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 437–454 (2020). 10.1038/s41568-020-0272-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lanier L. L., “ NK cell recognition,” Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 225–274 (2005). 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bryceson Y. T., March M. E., Ljunggren H. G., and Long E. O., “ Activation, coactivation, and costimulation of resting human natural killer cells,” Immunol. Rev. 214, 73–91 (2006). 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00457.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bauer S., Groh V., Wu J., Steinle A., Phillips J. H., Lanier L. L., and Spies T., “ Activation of NK cells and T Cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA,” Science 285, 727–729 (1999). 10.1126/science.285.5428.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Raulet D. H., Gasser S., Gowen B. G., Deng W., and Jung H., “ Regulation of ligands for the NKG2D activating receptor,” Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 413–441 (2013). 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fernández-Messina L., Reyburn H., and Vales-Gomez M., “ Human NKG2D-ligands: Cell biology strategies to ensure immune recognition,” Front. Immunol. 3, 299 (2012). 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Duan S., Guo W., Xu Z., He Y., Liang C., Mo Y., Wang Y., Xiong F., Guo C., Li Y. et al. , “ Natural killer group 2D receptor and its ligands in cancer immune escape,” Mol. Cancer 18, 29 (2019). 10.1186/s12943-019-0956-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wu J., Song Y., Bakker A. B., Bauer S., Spies T., Lanier L. L., and Phillips J. H., “ An activating immunoreceptor complex formed by NKG2D and DAP10,” Science 285, 730–732 (1999). 10.1126/science.285.5428.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Karimi M., Cao T. M., Baker J. A., Verneris M. R., Soares L., and Negrin R. S., “ Silencing human NKG2D, DAP10, and DAP12 reduces cytotoxicity of activated CD8+ T cells and NK cells,” J. Immunol. 175, 7819–7828 (2005). 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Marusina A. I., Burgess S. J., Pathmanathan I., Borrego F., and Coligan J. E., “ Regulation of human DAP10 gene expression in NK and T cells by Ap-1 transcription factors,” J. Immunol. 180, 409–417 (2008). 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Upshaw J. L., Arneson L. N., Schoon R. A., Dick C. J., Billadeau D. D., and Leibson P. J., “ NKG2D-mediated signaling requires a DAP10-bound Grb2-Vav1 intermediate and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase in human natural killer cells,” Nat. Immunol. 7, 524–532 (2006). 10.1038/ni1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Niu C., Li M., Chen Y., Zhang X., Zhu S., Zhou X., Zhou L., Li Z., Xu J., Hu J. F. et al. , “ LncRNA NCAL1 potentiates natural killer cell cytotoxicity through the Gab2-PI3K-AKT pathway,” Front. Immunol. 13, 970195 (2022). 10.3389/fimmu.2022.970195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wilton K. M., Overlee B. L., and Billadeau D. D., “ NKG2D–DAP10 signaling recruits EVL to the cytotoxic synapse to generate F-actin and promote NK cell cytotoxicity,” J. Cell Sci. 133, jcs230508 (2019). 10.1242/jcs.230508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Han J., Das B., Wei W., Van Aelst L., Mosteller R. D., Khosravi-Far R., Westwick J. K., Der C. J., and Broek D., “ Lck regulates Vav activation of members of the Rho family of GTPases,” Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 1346–1353 (1997). 10.1128/MCB.17.3.1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Barreira M., Rodríguez-Fdez S., and Bustelo X. R., “ New insights into the Vav1 activation cycle in lymphocytes,” Cell. Signalling 45, 132–144 (2018). 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cuevas B., Lu Y., Watt S., Kumar R., Zhang J., Siminovitch K. A., and Mills G. B., “ SHP-1 regulates Lck-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase phosphorylation and activity,” J. Biol. Chem. 274, 27583–27589 (1999). 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wan Z., Shao X., Ji X., Dong L., Wei J., Xiong Z., Liu W., and Qi H., “ Transmembrane domain-mediated Lck association underlies bystander and costimulatory ICOS signaling,” Cell. Mol. Immunol. 17, 143–152 (2020). 10.1038/s41423-018-0183-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Klein C. A., “ Framework models of tumor dormancy from patient-derived observations,” Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 21, 42–49 (2011). 10.1016/j.gde.2010.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fan R., Emery T., Zhang Y., Xia Y., Sun J., and Wan J., “ Circulatory shear flow alters the viability and proliferation of circulating colon cancer cells,” Sci. Rep. 6, 27073 (2016). 10.1038/srep27073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Regmi S., Fu A., and Luo K. Q., “ High shear stresses under exercise condition destroy circulating tumor cells in a microfluidic system,” Sci. Rep. 7, 39975 (2017). 10.1038/srep39975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Terrén I., Orrantia A., Vitallé J., Zenarruzabeitia O., and Borrego F., “ NK cell metabolism and tumor microenvironment,” Front. Immunol. 10, 2278 (2019). 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Piñeiro Fernández J., Luddy K. A., Harmon C., and O'Farrelly C., “ Hepatic tumor microenvironments and effects on NK cell phenotype and function,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4131 (2019). 10.3390/ijms20174131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Harmon C., Robinson M. W., Hand F., Almuaili D., Mentor K., Houlihan D. D., Hoti E., Lynch L., Geoghegan J., and O'Farrelly C., “ Lactate-mediated acidification of tumor microenvironment induces apoptosis of liver-resident NK cells in colorectal liver metastasis,” Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 335–346 (2019). 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Liu Y., Zhang T., Zhang H., Li J., Zhou N., Fiskesund R., Chen J., Lv J., Ma J., Zhang H. et al. , “ Cell softness prevents cytolytic T-cell killing of tumor-repopulating cells,” Cancer Res. 81, 476–488 (2021). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lei K., Kurum A., Kaynak M., Bonati L., Han Y., Cencen V., Gao M., Xie Y.-Q., Guo Y., Hannebelle M. T. M. et al. , “ Cancer-cell stiffening via cholesterol depletion enhances adoptive T-cell immunotherapy,” Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 1411–1425 (2021). 10.1038/s41551-021-00826-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Jin J., Tang K., Xin Y., Zhang T., and Tan Y., “ Hemodynamic shear flow regulates biophysical characteristics and functions of circulating breast tumor cells reminiscent of brain metastasis,” Soft Matter 14, 9528–9533 (2018). 10.1039/C8SM01781F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the supplementary material that includes a list of PCR primers and three supplementary figures.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.