Abstract

The concept of “one-airway-one-disease”, coined over 20 years ago, may be an over-simplification of the links between allergic diseases. Genomic studies suggest that rhinitis alone and rhinitis with asthma are operated by distinct pathways. In this MeDALL (Mechanisms of the Development of Allergy) study, we leveraged the information of the human interactome to distinguish the molecular mechanisms associated with two phenotypes of allergic rhinitis: rhinitis alone and rhinitis in multimorbidity with asthma. We observed significant differences in the topology of the interactomes and in the pathways associated to each phenotype. In rhinitis alone, identified pathways included cell cycle, cytokine signalling, developmental biology, immune system, metabolism of proteins and signal transduction. In rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity, most pathways were related to signal transduction. The remaining few were related to cytokine signalling, immune system or developmental biology. Toll-like receptors and IL-17-mediated signalling were identified in rhinitis alone, while IL-33 was identified in rhinitis in multimorbidity. On the other hand, few pathways were associated with both phenotypes, most being associated with signal transduction pathways including estrogen-stimulated signalling. The only immune system pathway was FceRI-mediated MAPK activation. In conclusion, our findings suggest that rhinitis alone and rhinitis and asthma multimorbidity should be considered as two distinct diseases.

Subject terms: Quality of life, Respiratory signs and symptoms, Asthma

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis tends to cluster with asthma (A) in multimorbidity1. However, clinically, two rhinitis (R) phenotypes can be identified: (i) R alone (affecting around 70–80% of patients with R) and (ii) R in multimorbidity with A (R + A), affecting 20–30%. On the other hand, the majority of patients with A have or have had rhinitis (R)1. Furthermore, airway remodelling, a constant feature of A, does simply not exist in R. It is also important to consider that the clinical, immunological and genetic differences between monosensitisation (to one allergen) and polysensitisation (to more than one allergen) and the link between polysensitisation and multimorbidity increase the heterogeneity of R. This suggests the existence of distinct molecular pathways in R + A and R alone2. In consequence, the concept of “one-airway-one-disease” (coined over 20 years ago) may be an oversimplification of the disease1,3.

Previous efforts to understand the links between R and R + A have focused on the atopic march sequence4. An alternative approach is the characterisation of the molecular mechanisms of these diseases and their interactions. A complete characterisation of cellular function can only emerge from studying how gene products interact with one another, forming a dense molecular network known as the interactome, which can be defined as the representation of all interactions (regulatory, metabolic, physical, etc.) among the gene products present at a given time within a cell. This is where the branch of systems biology, known as interactomics, comes into play, applying data mining and biostatistical methodologies (i) to identify molecular pathways and (ii) in general, to provide a molecular context that will facilitate the understanding of the complexity of many phenotypes. During the last decade, its analysis has provided important insights into the inner operations of the cell under different conditions including pathological ones5,6.

The MeDALL study, which was aimed at unravelling the complexity of allergic diseases, did show that the coexistence of eczema, R and A in the same child is more common than expected by chance alone, both in the presence and absence of IgE sensitisation. This suggests that these diseases share causal mechanisms7. A MeDALL in silico study suggested the existence of a multimorbidity cluster between A, eczema and R, and that type 2 signalling pathways represent a relevant multimorbidity mechanism of allergic diseases8. The in silico analysis of the interactome at the cellular level implied the existence of differentiated multimorbidity mechanisms between A, eczema and R at cell type level, as well as mechanisms common to distinct cell types9. A transcriptomics study of samples from MeDALL birth cohorts identified a signature of eight genes associated to multimorbidity for A, R and eczema7. In this study, genes of R alone differed from those of R + A multimorbidity without any overlap.

In this study, we used transcriptomic information obtained in MeDALL cohorts to compare the molecular mechanisms of R and R + A, assessing how the relationship between these diseases should be understood in a multimorbidity framework using an interactomics approach.

Materials and methods

Study design

We used the transcriptomics data from Lemonnier et al. obtained in MeDALL (Mechanisms of the Development of Allergy)10. The analysis comprised a cross-sectional study carried out in participants from three MeDALL cohorts using whole blood. It compared participants with single allergic disease (asthma, dermatitis or rhinitis) or with multimorbidity (A + D, A + R, D + R, or A + D + R) to those without asthma, dermatitis or rhinitis and non-allergic participants. We characterised the molecular pathways associated to R alone and R + A using an interactomics approach.

Settings and participants

Three birth cohorts were used: BAMSE (Swedish abbreviation for Children, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiology, Sweden), INMA (INfancia y Medio Ambiente, Spain) and GINIplus (German Infant Study on the Influence of Nutrition Intervention plus Air pollution and Genetics on Allergy Development, Germany)10.

Datasets

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for R alone and for R + A were obtained from the MeDALL gene expression study10–13. The full dataset is supplied in Supplementary Table S1.

The interactome

The first-degree interactomes of the DEGs for R alone and for R + A were independently generated using the IntAct database, which contains a curated collection of > 106 experimentally determined protein–protein interactions in human cells14. Data was downloaded via the IntAct web-based tool at the European Bioinformatics Institute (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/). Ensembl Gene IDs were used instead of HGNC names to avoid ambiguities. Self-interactions and expanded interactions were discarded. Interactomes are supplied in Supplementary Table S2. Network density was calculated as the number of edges with respect to the maximal possible number of edges. Random distributions were used to test the degree of interconnectedness of the interactomes. They were generated by random sampling of gene sets (of the same size) of each interactome over 10,000 iterations.

Functional annotation

The interactomes were functionally annotated using the DAVID web-based tool15, with the Reactome database as the source of functional information16 and the default gene background. Functional pathways were considered significant with FDR < 0.05. In order to simplify the functional annotation and remove redundancy, pathways associated to diseased or defective cellular processes were removed and we only considered pathways in the intermediate levels (levels 3 and 4) of the Reactome hierarchy. Furthermore, we assigned each pathway to a generic functional family (“Signal Transduction”, “Cell Cycle”, etc.) in order to help interpreting the results. We did this by (1) clustering all the pathways according to their Szymkiewicz-Simpson overlap17; (2) identifying the best partition of using the Pearson’s Gamma method18 implemented in the fpc R package; and (3) asigning each cluster in the best partition to a generic pathway (i.e. a Reactome pathway with > 800 genes) by means of a Fisher’s Exact Test19. Full functional annotation is available in Supplementary Table S3.

Software

All data mining and statistical analysis were carried out using the R programming language20.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the participants

Among the 786 participants included in the analysis, 54.8% had no allergic disease. Among those with an allergic disease, 45% had asthma (61% with multimorbidity), 42% dermatitis (48%) and 51% rhinitis (49%). Asthma was more common in BAMSE (63%), dermatitis in INMA (74%) and rhinitis in GINIplus (79%). Fifty-five percent of the participants had no allergic disease (BAMSE 39%, GINIplus 67%, INMA 54%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the population study.

| BAMSE | GINIplus | INMA | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual samples included | 270 | 346 | 208 | 824 |

| Samples with process faila | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Samples with quality failb | 7 | 11 | 1 | 19 |

| Outliers detectedc | 6 | 5 | 5 | 16 |

| Included in the analysis | 256 | 329 | 201 | 786 |

| Male (n, %d) | 143 (55.9) | 160 (48.6) | 99 (49.2) | 402 (51.1) |

| Female (n, %d) | 113 (44.1) | 169 (51.4) | 102 (50.8) | 384 (48.9) |

| Controls (n, %d) | 100 (39.1) | 222 (67.5) | 109 (54.2) | 431 (54.8) |

| Any allergic disease (n, %d) | 156 (60.9) | 107 (32.5) | 92 (45.8) | 355 (45.2) |

| A alone (n) | 32 | 15 | 18 | 65 |

| D alone (n) | 22 | 6 | 48 | 76 |

| R alone (n) | 23 | 64 | 4 | 91 |

| A + D (n) | 17 | 1 | 16 | 34 |

| A + R (n) | 33 | 15 | 2 | 50 |

| D + R (n) | 13 | 4 | 4 | 21 |

| A + D + R (n) | 16 | 2 | 0 | 18 |

| Asthma multimorbidity (n, %e) | 66 (42.3) | 18 (16.8) | 18 (19.6) | 102 (28.7) |

| Dermatitis multimorbidity (n, %e) | 46 (29.5) | 7 (6.5) | 20 (21.7) | 73 (20.6) |

| Rhinitis multimorbidity (n, %e) | 62 (39.7) | 21 (19.6) | 6 (6.5) | 89 (25.1) |

| Any multimorbidity (n, %e) | 79 (50.6) | 22 (20.6) | 22 (23.9) | 123 (34.6) |

| Any single disease (n, %e) | 77 (49.4) | 85 (79.4) | 70 (76.1) | 232 (65.4) |

| Age (years ± sd) | 16.7 ± 0.4 | 15.0 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 12.8 ± 5.1 |

Demographics. A: asthma, D: dermatitis, R: rhinitis.

aProcess fail: samples failed extraction, sample preparation or hybridisation/scan process, no CEL file available.

bQuality fail: samples not complying with minimal RIN or Genechip metrics thresholds.

cOutliers selection based on PCA as described in supplementary methods in Lemonnier et al.10.

d% of total.

e% of cases.

Topological analysis of the interactomes

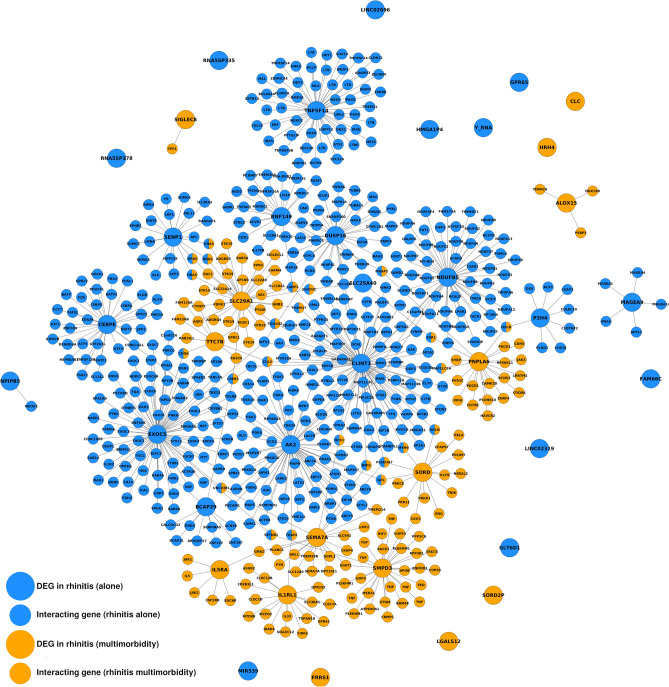

We generated interactomes for R alone and R + A, which can be seen as snapshots of the cellular mechanisms behind these conditions (Fig. 1). The interactome of R alone consisted of 464 genes connected by 466 edges. The interactome of R + A consisted of 130 genes connected by 149 edges. The interactome of R alone is 2.18 times denser than random expectation, which is statistically significant (z-test; P = 1.09·10–11). Similarly, the interactome of R + A is 6.22 times denser than random expectation, which is also statistically significant (z-test; P = 3.42·10–50). There were no DEGs common to R alone and R + A in the MeDALL study, but we identified 25 genes common to both interactomes, which implied a degree of interconnectedness significantly larger than random expectation (z-test; P = 2.52·10–22).

Figure 1.

Interactomes of rhinitis alone and rhinitis associated with multimorbidity. DEGs: differentially expressed genes. For clarity, only genes with HGNC symbol are shown.

Functional annotation

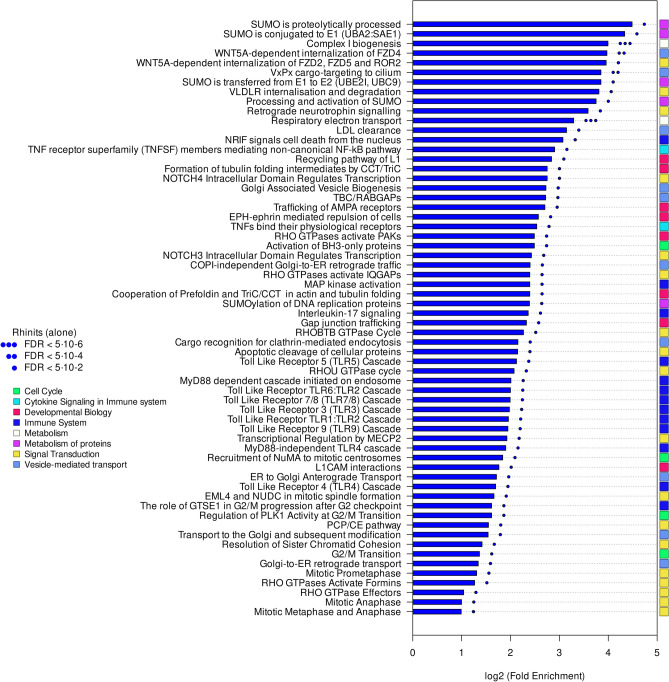

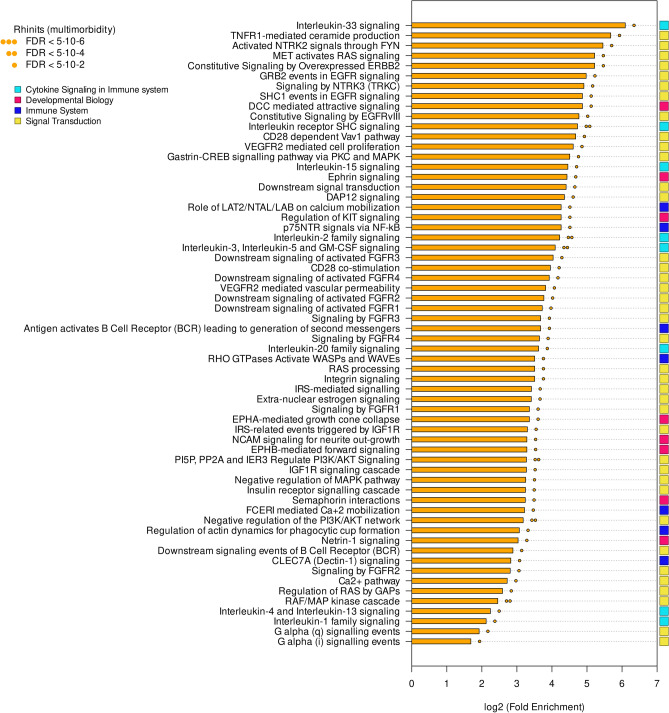

Functional annotation revealed marked differences in the molecular pathways of both phenotypes. Pathways specific to R alone (Fig. 2; in table form in Supplementary Table S4) involved a number of Toll-like receptor (TLR), IL-17 and MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88) signalling cascades, as well as WNT5A-dependent signalling, RHO GTPase activity and the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) pathways. In contrast, pathways associated to R + A (Fig. 3; in table form in Supplementary Table S4) were much richer in signal-transduction-related processes such as IL-mediated and fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs)-mediated signalling. IL-33 particularly stood out with a ~ 68-fold enrichment.

Figure 2.

Pathways unique to rhinitis alone. Pathways were classified in broad functional families (coloured rectangles).

Figure 3.

Pathways unique to rhinitis in multimorbidity. Pathways were classified in broad functional families (coloured rectangles).

The pathways common to both R phenotypes are shown in Fig. 4 (in table form in Supplementary Table S4). The pathways with largest fold enrichment (both in R alone and R + A) are estrogen-stimulated signalling through PRKCZ and RAS-mediated signalling.

Figure 4.

Pathways common to rhinitis alone and rhinitis in multimorbidity. Pathways were classified in broad functional families (coloured rectangles).

Discussion

Using topological and functional analysis, we identified a core of common mechanisms between the two phenotypes of R, but also found significant differences between both phenotypes. Densely interconnected groups of genes within the interactome are known to be contributors to the same pathological phenotypes21. The high level of connectivity that we observed within the interactome of each phenotype, together with the lack of common DEGs, suggests that R alone and R + A are largely mechanistically different diseases, affecting different molecular pathways.

TLRs stand out as strong drivers of R alone. TLRs are type I transmembrane receptors employed by the innate immune system22. Variation in the TLR genes has been associated with R in several candidate gene studies. A significant excess of rare variants in R patients was found in TLR1, TLR5, TLR7, TLR9 and TLR10 but not in TLR823. Children carrying a minor rs1927911 (TLR4) allele may be at a higher R risk24. In turn, TLR is strongly associated to MyD88 pathways, mediating in innate lymphoid cells type 2 (ILC2) activation and eosinophilic airway inflammation25,26. IL-17 was also identified, as were SUMO pathways, known to regulate many cellular processes including signal transduction and immune responses27,28. Furthermore, it is known that SUMOylation plays a critical role in the expression of TSLP in airway epithelial cells. Inhibition of SUMOylation attenuates house dust mite-induced epithelial barrier dysfunction29.

On the other hand, there are a number of mechanisms—such as Nf-kB-mediated signalling and IL-1 and IL-33 activity—that seem to be driving R + A multimorbidity. IL-33 and IL1RL1 are among the most highly replicated susceptibility loci for A30, and IL-33 has a known role in infection-mediated A susceptibility31. There is an increase in FGFR (fibroblast growth factor receptor) signalling. The FGF/FGFR signalling system regulates a variety of biological processes, including embryogenesis, angiogenesis, wound repair and lung development32. It may be relevant in A remodelling. Interleukin-33 (IL-33) which belongs to the interleukin-1 (IL-1) family is an alarmin cytokine with critical roles in tissue homeostasis, pathogenic infection, inflammation, allergy and type 2 immunity. IL-33 transmits signals through its receptor IL-33R (also called ST2) which is expressed on the surface of T helper 2 (Th2) cells and group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), thus inducing transcription of Th2-associated cytokine genes and host defense against pathogens33. IL33 and IL1RL1/ST2 are among the most highly replicated susceptibility loci for asthma34,35. However, IL-33 is not associated with rhinitis alone36.

The exposure of the airway epithelium to external stimuli such as allergens, microbes, and air pollution triggers the release of the alarmin cytokines IL-25, IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP interact with their ligands, IL-17RA, IL1RL1 and TSLPR, expressed by cells including dendritic cells, ILC2 cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. Alarmins play key roles in driving type 2-high, and to a lesser extent type 2-low responses, in asthma1,3,37. Future analysis could exploit tissue-specific transcriptomic data to highlight the differences between the epithelium of upper and lower airways38,39.

Finally, some signal transduction pathways common to R alone and R + A have an impact on the IgE-mediated immune response. They include activation of RAS on B cells, CD209 signalling40, MAPK Kinase41, FceRI MAPK kinase activation42, ERK activation43, Raf kinases44 or VEGFA45.

Limitations of the study

One major problem is that there are no data on A without rhinitis. However, this is not the first study in which either the A population is too low or there is no signal for A alone10. This is the case for the present study and we were unable to include the A alone group. It is likely that A is almost always associated with R in children.

Incompleteness and spurious interactions have for a long time been limitations in studies that make use of data from the human interactome. However, authors have argued that data noise does not limit a successful application of the interactome to the investigation of disease mechanisms46,47. Also, the human interactome is known to be biased towards certain genes of interest (a category that includes many disease-associated genes)48. However, non-biased interactomes have a much lower coverage, which makes them unsuitable for some topology-based studies49. Lastly, time-dependent and location-dependent interaction patterns are not captured in our study, which only considers an interactome static in time.

Impact of the study

Clinical data, epidemiologic studies50, mHealth-based studies51 and genomic approaches7 all support the existence of two distinct diseases: R alone and R with A multimorbidity. This study helps to better understand the differences between R and R + A and to refine the ARIA-MeDALL hypothesis on allergic diseases52. It also highlights the importance of IL-1753, IL-3354 and their interactions to understand the allergic multimorbidity.

Conclusions

The interactomes of R alone and R + A showed topological characteristics that suggest that the cellular mechanisms involved are different for each phenotype. We identified mechanisms specific to R alone (TLR and MyD88 signalling cascades, SUMO pathways) and mechanisms specific to R + A (IL-33-mediated signalling, FGFR-mediated signalling).

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

J.B. conceived and designed the project. D.A. implemented the computational analysis. E.M., G.H.K., J.C.C., J.M.A., M.B., N.L., O.G., S.G. and T.K. assisted in interpreting the results. D.A. and J.B. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets supporting this work are available as supplementary materials. Transcriptomics data was downloaded from Lemonnier et al.9.

Competing interests

DA reports personal fees from MASK-AIR SAS, outside the submitted work. JB reports personal fees from Cipla, Menarini, Mylan, Novartis, Purina, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva, Uriach, other from KYomed-Innov, other from Mask-air-SAS, outside the submitted work. JCC reports other from GSK, other from Merck, other from Pharmavite, outside the submitted work. GHK reports grants from Netherlands Lung Foundation, TEVA, VERTEX, GSK, Ubbo Emmius Foundation, European Union, Zon MW (Vici Grant), outside the submitted work; and GHK participated in advisory boards to GSK, AZ and Pure-IMS (Money to institution). The other authors have no COIs to disclose, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-39987-6.

References

- 1.Bousquet J, Va:n Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;108(5 Suppl):S147–334. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz AA, Popov T, Pawankar R, et al. Common characteristics of upper and lower airways in rhinitis and asthma: ARIA update, in collaboration with GA(2)LEN. Allergy. 2007;62(Suppl 84):1–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bousquet J, Melen E, Haahtela T, et al. Rhinitis associated with asthma is distinct from rhinitis alone: The ARIA-MeDALL hypothesis. Allergy. 2023;78(5):1169–1203. doi: 10.1111/all.15679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Custovic A, Custovic D, Kljaic Bukvic B, Fontanella S, Haider S. Atopic phenotypes and their implication in the atopic march. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020;16(9):873–881. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2020.1816825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: A network-based approach to human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruiz C, Zitnik M, Leskovec J. Identification of disease treatment mechanisms through the multiscale interactome. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1796. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21770-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinart M, Benet M, Annesi-Maesano I, von Berg A, Berdel D, Carlsen KC, Carlsen KH, Bindslev-Jensen C, Eller E, Fantini MP, et al. Comorbidity of eczema, rhinitis, and asthma in IgE-sensitised and non-IgE-sensitised children in MeDALL: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014;2(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguilar D, Pinart M, Koppelman GH, Saeys Y, Nawijn MC, Postma DS, Akdis M, Auffray C, Ballereau S, Benet M, et al. Computational analysis of multimorbidity between asthma, eczema and rhinitis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0179125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aguilar D, Lemonnier N, Koppelman GH, Melén E, Oliva B, Pinart M, Guerra S, Bousquet J, Anto JM. Understanding allergic multimorbidity within the non-eosinophilic interactome. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0224448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemonnier N, Melen E, Jiang Y, et al. A novel whole blood gene expression signature for asthma, dermatitis, and rhinitis multimorbidity in children and adolescents. Allergy. 2020;75:3248–3260. doi: 10.1111/all.14314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg AV, Krämer U, Link E, Bollrath C, Heinrich J, Brockow I, Koletzko S, Grübl A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Wichmann HE, et al. GINIplus Study Group. Impact of early feeding on childhood eczema: Development after nutritional intervention compared with the natural course—the GINIplus study up to the age of 6 years. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2010;40(4):627–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guxens M, Ballester F, Espada M, Fernández MF, Grimalt JO, Ibarluzea J, Olea N, Rebagliato M, Tardón A, Torrent M, Vioque J, et al. INMA Project. Cohort profile: The INMA–INfancia y Medio Ambiente–(Environment and Childhood) project. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012;41(4):930–940. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merid SK, Bustamante M, Standl M, Sunyer J, Heinrich J, Lemonnier N, Aguilar D, Antó JM, Bousquet J, Santa-Marina L, Lertxundi A, Bergström A, Kull I, Wheelock ÅM, Koppelman GH, Melén E, Gruzieva O. Integration of gene expression and DNA methylation identifies epigenetically controlled modules related to PM2.5 exposure. Environ. Int. 2021;146:106248. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Toro N, Shrivastava A, Ragueneau E, Meldal B, Combe C, Barrera E, Perfetto L, How K, Ratan P, Shirodkar G, et al. The IntAct database: Efficient access to fine-grained molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D648–D653. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, Jiao X, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Imamichi T, Chang W. DAVID: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jassal B, Matthews L, Viteri G, Gong C, Lorente P, Fabregat A, Sidiropoulos K, Cook J, Gillespie M, Haw R, et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D498–D503. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vijaymeena M, Kavitha K. A survey on similarity measures in text mining. Mach. Learn. Appl. Int. J. 2016;3:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halkidi M, Batistakis Y, Vazirgiannis M. On clustering validation techniques. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2001;2(17):107–145. doi: 10.1023/A:1012801612483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher RA. Statistical Methods for Research Workers. Oliver & Boyd; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park J, Lee DS, Christakis NA, Barabási AL. The impact of cellular networks on disease comorbidity. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:262. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zakeri A, Russo M. Dual role of toll-like receptors in human and experimental asthma models. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1027. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henmyr V, Lind-Hallden C, Carlberg D, et al. Characterization of genetic variation in TLR8 in relation to allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2016;71(3):333–341. doi: 10.1111/all.12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuertes E, Brauer M, MacIntyre E, et al. Childhood allergic rhinitis, traffic-related air pollution, and variability in the GSTP1, TNF, TLR2, and TLR4 genes: Results from the TAG study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132(2):342–352.e342. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shalaby KH, Allard-Coutu A, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Inhaled birch pollen extract induces airway hyperresponsiveness via oxidative stress but independently of pollen-intrinsic NADPH oxidase activity, or the TLR4-TRIF pathway. J. Immunol. 2013;191(2):922–933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein MM, Hrusch CL, Gozdz J, et al. Innate immunity and asthma risk in Amish and Hutterite farm children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375(5):411–421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eifler K, Vertegaal ACO, Mahajan R, Gerace L, Melchior F, Matunis MJ, et al. SUMO-1 modification of IκBα inhibits NF-κB activation. J. Cell Biol. 1998;140:259–270. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imbert F, Langford D. Viruses, SUMO, and immunity: The interplay between viruses and the host SUMOylation system. J. Neurovirol. 2021;27(4):531–541. doi: 10.1007/s13365-021-00995-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang S, Zhou Z, Zhou Z, et al. Blockade of CBX4-mediated beta-catenin SUMOylation attenuates airway epithelial barrier dysfunction in asthma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022;113(Pt A):109333. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cayrol C, Girard JP. IL-33 (IL-33): A nuclear cytokine from the IL-1 family. Immunol. Rev. 2018;281(1):154. doi: 10.1111/imr.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson DJ, Makrinioti H, Rana BM, et al. IL-33-dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014;190(12):1373–1382. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang D, Li X, Zhao C, et al. FGF/FGFR signaling: From lung development to respiratory diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021;62:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi XM, Lian H, Li S. Signaling and functions of interleukin-33 in immune regulation and diseases. Cell Insight. 2022;1(4):100042. doi: 10.1016/j.cellin.2022.100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Zhang Y, Zhang L. Discovering susceptibility genes for allergic rhinitis and allergy using a genome-wide association study strategy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;15(1):33–40. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise SK, Lin SY, Toskala E, Orlandi RR, Akdis CA, et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: Allergic rhinitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8(2):108–352. doi: 10.1002/alr.22070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi BY, Han M, Kwak JW, Kim TH. Genetics and epigenetics in allergic rhinitis. Genes. 2021;12(12):2004. doi: 10.3390/genes12122004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duchesne M, Okoye I, Lacy P. Epithelial cell alarmin cytokines: Frontline mediators of the asthma inflammatory response. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:975914. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagener AH, Zwinderman AH, Luiten S, Fokkens WJ, Bel EH, Sterk PJ, van Drunen CM. The impact of allergic rhinitis and asthma on human nasal and bronchial epithelial gene expression. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagener AH, Zwinderman AH, Luiten S, Fokkens WJ, Bel EH, Sterk PJ, van Drunen CM. dsRNA-induced changes in gene expression profiles of primary nasal and bronchial epithelial cells from patients with asthma, rhinitis and controls. Respir. Res. 2014;15(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jabril-Cuenod B, Zhang C, Scharenberg AM, et al. Syk-dependent phosphorylation of Shc. A potential link between FcepsilonRI and the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway through SOS and Grb2. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271(27):16268–16272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Yu W, Lyu SC, et al. A positive feedback loop reinforces the allergic immune response in human peanut allergy. J. Exp. Med. 2021;218(7):e20201793. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kannan Y, Wilson MS. TEC and MAPK kinase signalling pathways in T helper (TH) cell development, TH2 differentiation and allergic asthma. J. Clin. Cell Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.S12-011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mor A, Shefler I, Salamon P, Kloog Y, Mekori YA. Characterization of ERK activation in human mast cells stimulated by contact with T cells. Inflammation. 2010;33(2):119–125. doi: 10.1007/s10753-009-9165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin W, Su F, Gautam R, Wang N, Zhang Y, Wang X. Raf kinase inhibitor protein negatively regulates FcepsilonRI-mediated mast cell activation and allergic response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115(42):E9859–E9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805474115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cristinziano L, Poto R, Criscuolo G, et al. IL-33 and superantigenic activation of human lung mast cells induce the release of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors. Cells. 2021;10(1):145. doi: 10.3390/cells10010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menche J, Sharma A, Kitsak M, Ghiassian SD, Vidal M, Loscalzo J, et al. Disease networks. Uncovering disease-disease relationships through the incomplete interactome. Science. 2015;347(6224):1257601. doi: 10.1126/science.1257601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huttlin EL, Bruckner RJ, Paulo JA, Cannon JR, Ting L, Baltier K, Colby G, Gebreab F, Gygi MP, Parzen H, et al. Architecture of the human interactome defines protein communities and disease networks. Nature. 2017;545(7655):505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillis J, Pavlidis P. "Guilt by association" is the exception rather than the rule in gene networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8(3):e1002444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaefer MH, Serrano L, Andrade-Navarro MA. Correcting for the study bias associated with protein–protein interaction measurements reveals differences between protein degree distributions from different cancer types. Front. Genet. 2015;6:260. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burte E, Bousquet J, Varraso R, Gormand F, Just J, Matran R, et al. Characterization of rhinitis according to the asthma status in adults using an unsupervised approach in the EGEA study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bousquet J, Devillier P, Anto JM, Bewick M, Haahtela T, Arnavielhe S, et al. Daily allergic multimorbidity in rhinitis using mobile technology: A novel concept of the MASK study. Allergy. 2018;73(8):1622–1631. doi: 10.1111/all.13448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bousquet J, Anto JM, Wickman M, Keil T, Valenta R, Haahtela T, et al. Are allergic multimorbidities and IgE polysensitization associated with the persistence or re-occurrence of foetal type 2 signalling? The MeDALL hypothesis. Allergy. 2015;70(9):1062–1078. doi: 10.1111/all.12637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Majumder S, McGeachy MJ. IL-17 in the pathogenesis of disease: Good intentions gone awry. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021;39:537–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101819-092536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: The new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10(2):103–110. doi: 10.1038/nri2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this work are available as supplementary materials. Transcriptomics data was downloaded from Lemonnier et al.9.