Abstract

Introduction: Photobiomodulation treatment (PBMT) is a relatively invasive method for treating wounds. An appropriate type of PBMT can produce desired and directed cellular and molecular processes. The aim of this study was to investigate the impacts of PBMT on stereological factors, bacterial count, and the expression of microRNA-21 and FGF2 in an infected, ischemic, and delayed wound healing model in rats with type one diabetes mellitus.

Methods: A delayed, ischemic, and infected wound was produced on the back skin of all 24 DM1 rats. Then, they were put into 4 groups at random (n=6 per group): 1=Control group day4 (CGday4); 2=Control group day 8 (CGday8); 3=PBMT group day4 (PGday4), in which the rats were exposed to PBMT and killed on day 4; 4=PBMT group day8 (PGday8), in which the rats received PBMT and they were killed on day 8. The size of the wound, the number of microbial colonies, stereological parameters, and the expression of microRNA-21 and FGF2 were all assessed in this study throughout the inflammation (day 4) and proliferation (day 8) stages of wound healing.

Results: On days 4 and 8, we discovered that the PGday4 and PGday8 groups significantly improved stereological parameters in comparison with the same CG groups. In terms of ulcer area size and microbiological counts, the PGday4 and PGday8 groups performed much better than the same CG groups. Simultaneously, the biomechanical findings in the PGday4 and PGday8 groups were much more extensive than those in the same CG groups. On days 4 and 8, the expression of FGF2 and microRNA-21 was more in all PG groups than in the CG groups (P<0.01).

Conclusion: PBMT significantly speeds up the repair of ischemic and MARS-infected wounds in DM1 rats by lowering microbial counts and modifying stereological parameters, microRNA-21, and FGF2 expression.

Keywords: Type one diabetes mellitus, Ulcer healing, Photobiomodulation, Stereological parameters, Microbial examination

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (DM1) is a chronic situation affected by the inability of the pancreas to produce enough insulin.1 In 2017, 451 million individuals worldwide were diagnosed with diabetes. By 2045, the number of DM1 people is predicted to reach 693 million. One of the most critical issues confronting DM1 patients is an increased risk of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). DFUs are caused by the interaction of various relevant elements. Infection, ischemia, and neuropathy are the three primary pathogenic causes that lead to diabetic foot complications. Some evidence shows lower limb amputation occurs in about 75 to 85% of cases following foot ulcers, which are usually associated with chronic infection, decreased recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), reduced angiogenesis, declined migration and proliferation of skin cells like fibroblasts and keratinocytes, and increases in inflammatory cells.2,3

The parenchyma around the wound, which includes fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, inflammatory cells, new blood vessels, regenerated neurons, and other cells, is harmed in diabetes wounds.4 In reaction to tissue injury, fibroblast, endothelial, and macrophage cells, in particular endothelial cells, release basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) which is crucial for promoting wound healing.5,6

Numerous studies have shown that fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) can speed up the repair of diabetic ulcers and has a lot of promise as a therapy for diabetic ulcers.5,6 bFGF, also identified as FGF2, promotes endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis while inhibiting cell death.

Numerous cellular processes, containing cell specification, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival, are regulated by FGF and microRNAs (miRNAs) signaling.7 miRNAs are non-coding RNAs that adjust gene expression. Recent data show that miRNAs have a central role in both the normal healing and development of long-term ulcers like DFUs.8

MicroRNA-21, one of the first mammalian miRNAs recognized, has been found to be involved in a variety of biological processes. Growing documents propose that MicroRNA-21 has an important role in cutaneous damage and skin wound recovery by forming a network with its target genes and signaling pathways.9-13 The therapy efficacy provided by miR-21 may be attributed to an increase in fibroblast differentiation, angiogenesis expansion, anti-inflammatory effects, collagen synthesis enhancement, and wound re-epithelialization. Xie et al discovered that miRNA-21 inhibits inflammation and promotes wound healing via modulating the expression of NF-κB through PDCD4 and FGF.9 However, the amount of MiR-21 expression was much lower in diabetic injuries. Reduced levels of miR-21 are likewise linked to increased levels of its target gene expression.12-15 Because of this, raising the amount of miRNA-21 in damaged tissue can reduce inflammatory signals and boost healing.13,16

The method of photobiomodulation treatment (PBMT) has long been applied to improve local circulation. PBMT increases ulcer repair by modulating the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and triggering angiogenesis, HIF-1α expression, and MMP-2 activity.17,18 PBMT improves ischemic tissue19 and accelerates the repair of a wound. Today, the PBMT technique is increasingly applied to some wounds and in incurable wound treatments.20-22

Over 100 identified chemicals are involved in the aberrant healing of skin injury in diabetics.23 The use of appropriate agents and biomodulators seems to be helpful in the management of incurable ulcers.24

In previous studies of our group, the positive impact of PBMT on the inflammatory and prolative steps of wound repair in healthy and diabetic rats was reported using stereological, biomechanical, and gene expression levels of some related genes in wound repair. However, in these studies, the role of miRNAs and their relationships was not investigated.25-27 Thus, we tried to investigate the effects of PBMT administration on the stereological parameters, expression of microRNA-21, FGF2, bacterial count, and wound size in an infected, ischemic, and delayed wound repairing model in a DM1 rat.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Twenty-four 3-month-old male rats were allocated into four groups at random (n = 6 for each group). An ischemic, delayed, and MARS-infected wound model was generated in all DM1 experimental animals. Experimental rats were arbitrarily allocated into 4 groups, including CGday 4 & day 8 = control groups; PGday4, the animals in this group were exposed to PBMT and killed on day 4; PGday8, the animals in this group received PBMT and were killed on day 8. In this study, the level of the wound area, microbial colony counts, stereological examination, and expression of FGF2 and miR-21 were evaluated in the inflammation phase (day 4) and in the proliferation phase (day 8), respectively.

DM1 Induction

After a 12-hour fast, DM1 was created with an IP prescription of streptozotocin (STZ) (40 mg/kg).28 A glucometer was used to perform a blood glucose test on tail-vein blood 8 days after the STZ prescription. Dm1 rats had fasting blood glucose levels that surpassed 250 mg/dL (13.9 mmol). Water consumption and weight were tracked throughout the research, and fasting blood glucose levels were measured again on the day of euthanasia to confirm diabetic status. To confirm DM1 induction, we kept all rats with DM1 for one month.29,30

Clinical Tests

Throughout the test, the DM1 rats’ blood glucose and body weight were checked.

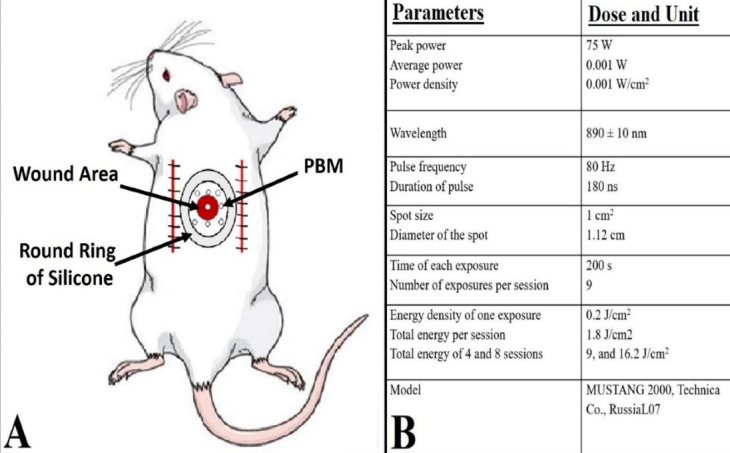

Surgery

Here, 50 mg/kg of ketamine and 5 mg/kg of xylazine were used to anesthetize the rats. All treated rats received ceftriaxone at a dose of 50 mg/kg before the operation and for 24 and 48 hours post-operation, respectively. A dorsal, bi-pedicle skin flap with a dimension of 10 3.5 cm was produced in the back skin of all animals. Then, a 12 mm full-thickness excisional round ulcer was created in the medial point of the flap through a biopsy punch. With a 0.4 silk skin holder, a round piece of silicone was sutured around the skin lesion. Here, 20 mg/kg of ibuprofen was injected into all the experimental rats every 8–12 hours before and 5 days after surgery (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Photograph of the wound area and laser radiation location (photobiomodulation) in the rat. (B) The dose and unit of the used photobiomodulation parameters

Injection of MRSA Into the Ulcer Area and Microbiological Test

In this preclinical study, the MRSA strain (ATCC 25923) was used. This technique has been reported in earlier studies. Briefly, a colony of MRSA with a concentration of 2 × 108 at 1 cc was prepared. A 100-L aliquot of it (2 × 107 MRSA) was injected locally into all ulcers following surgery. For microbiological tests, some microbiological samples were gathered from inured areas on days 0, 4th, and 8th, respectively. Then the bacterial colony was counted as the number of bacteria per sample (CFUs).25,31

Photobiomodulation

Ulcers in groups 3 (GPday4) and 4 (PGday8) were radiated with PBMT (Mustang 2000, LO7 Pen, Technica Co., Russia, Table 1) instantly after surgery and followed for 4 and 8 days, respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1. Primer Sequences of the Studied Genes .

| TARGET Gene | Primers | Primer Sequences | Tm |

| FGF2 | F | GACCCACACGTCAAACTACA | 57.77 |

| R | GCCGTCCATCTTCCTTCATAG | 58.24 | |

| GAPDH | F | ATCTGACATGCCGCCTGGAG | 61.40 |

| R | AAGGTTGGAAGAATGGGAGTTGC | 60.25 | |

| microRNA-21 | F | TAGCTTATCAGACTGATG | 62.10 |

| PROB | TGGTGTCGTGGAGTCG | 59.14 | |

| RNU6 | F | TCCGATCGTGAAGCGTTC | 64.40 |

| PROB | GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT | 63.05 |

Abbreviations: FGF2, fibroblast growth factor 2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; RNU6, RNA, U6 small nuclear 2.

Wound Area Measurement

In this study, a digital camera was used to photograph the wound site on days 0, 4, and 8. The size of the wounds (mm2) was then measured using Image J-NIH (USA) and compared with day zero.32

Wound Strength Examination

On day 8, a sample with a 50*5 mm dimension was taken from each wound location and put in a material testing machine. 10 mm/min was the rate of deformation. The maximal force (N) and stress high load (N/cm2) of the samples were estimated from the load-deformation curve.31

Histological and Stereological Analysis

The tissue samples obtained from each skin wound area were transferred into formalin saline for fixation. The collected samples were then paraffin blocked, and paraffin slices (5 m thick) were set for hematoxylin and eosin (H& E) staining. Lastly, 10 parts were chosen at random for stereological investigation. In this investigation, the physical dissector technique was set to estimate the number of macrophages, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and blood vessels in each rat. The systematic random sampling approach was used to choose 10 random paraffin slices from each rat. Four random fields were tallied in each segment. The raw data acquired were computed using the formulas shown below.

Numerical Density (Nv) = ΣQ/ (h × a/f × Σp):

Where ΣQ = the numeral of cells; h = dissector height; a/f = all the area of the counted frames; and ΣP = the total number of counting frames.

Number of blood vessels = 2ΣQ/ (ΣP × a/f)

Where ΣQ = all vessel numbers counted per each wound. The blood vessel counts were considered a marker for angiogenesis.

The serial slices were delivered and evaluated with a 100x objective lens for wound area cell counting.25,26,33,34

RNA Extraction and qRT -PCR Detection of miR-21 Expression Level

First, skin wound samples were harvested from the skin wound areas of all studied rats, and then total RNA from these skin samples was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The harvested total mRNA was estimated for purity by a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) at the ratio of absorbance 260/280 nm and then kept in a nitrogen tank at −80. The purified total mRNAs were reverse transcribed by cDNA reverse transcription kits (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). After pre-amplification, the expression level of the studied genes was evaluated by SYBR green and qRT-PCR on a Step OneTM thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH (a housekeeping gene) and RNU6b (RNA, U6 small nuclear 2) were applied as house kipping genes respectively.11-13 Table 1 replicates the primer lists for the GAPDH and FGF2, microRNA21, and RNU6b. Based on the pairwise fixed reallocation randomization test, the REST 2009 software was applied to estimate the level of gene expression in the rats studied. The obtained data were compared by the ΔΔCT method.11

Statistical Analysis

The obtained data were compared using SPSS 24, and the harvested data were displayed as the mean and standard deviation (SD). In this preclinical study, the independent samples ttest was used to assess the data obtained from body weight measurement, microbiological testing, wound strength tests, and wound area size. In this case, statistical significance was defined as considerably less than 0.05.

To determine the sample size, we used Cochran’s sample size method. For this purpose, Cochran’s table with a 5% significance level and 80% test power was used for one-way analysis and LSD tests. We conservatively selected six sample sizes for each experimental group.

Results

Clinical Observations

Clinical data revealed that all of the rats had DM1. Following STZ therapy, we noticed an important growth in blood sugar levels as well as a fall in body weight (Table 2).

Table 2. The Blood Sugar and Body Weight of the Studied Groups .

| Factors | Groups | |

| CG | PG | |

| First blood sugar (mg/dL) | 355.02 ± 52.3 | 333.1 ± 73 |

| Final blood sugar (mg/dL) | 414.3 ± 63.74** | 282.5 ± 44.1 |

| First body weight (g) | 310.4 ± 12.6 | 301.57 ± 12.2 |

| Final body weight (g) | 265.75 ± 15.95* | 285.80 ± 14.17 |

Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PG, Photobiomodulation group.

Data were evaluated and compared by the student t test. ** P < 0.01 and * P < 0.05.

Our independent samples t test data displayed that the body weight of rats was significantly superior in the PGday4 and PGday8 groups (P = 0.005) than in the CG group.

Blood sugar levels in the PG groups improved significantly more than those in the CG groups. This blood sugar decrease was more in the PGday8 group than in the CG group.

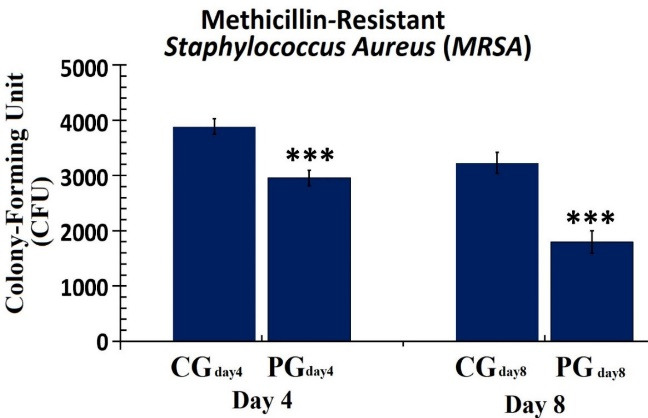

Microbial Findings

Our microbial study showed that the level of CFU on day 4 was considerably lesser in the PGday4 group (P = 0.000) than in the CGday4 group. On day 8, the changes in the count of CUF were also shown in the group of PGday8 compared with the CGday8 group (P = 0.000; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Number of Colony-Forming Units in the GP and CP Groups on the 4th and 8th Days. The independent-samples t-test was used to assess the data. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PG, Photobiomodulation group

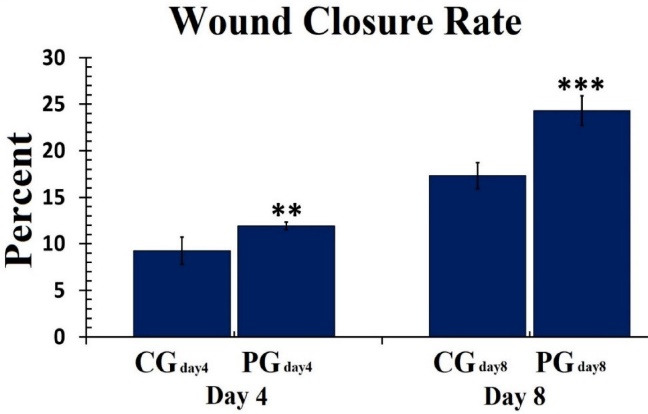

Wound Area Measurement

On day 4, the wound area size was meaningfully smaller in the PGday4 groups (P = 0.001) than in the CGday4 groups. On day 8, there was also a statistically significant alteration in the ulcer area between the PG and CG groups (P = 0.000; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Size of the Wound Area in the Studied Groups on Days 4 and 8. The data were analyzed by the independent samples t test. **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PG, Photobiomodulation group

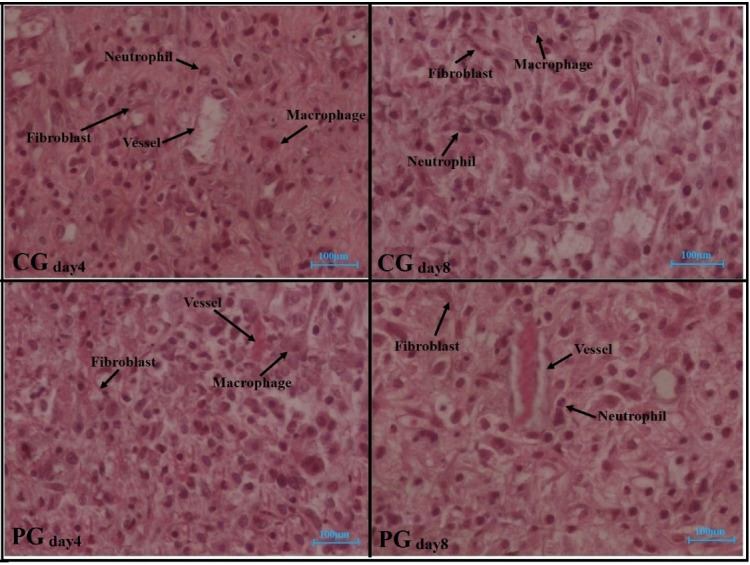

Stereological Findings

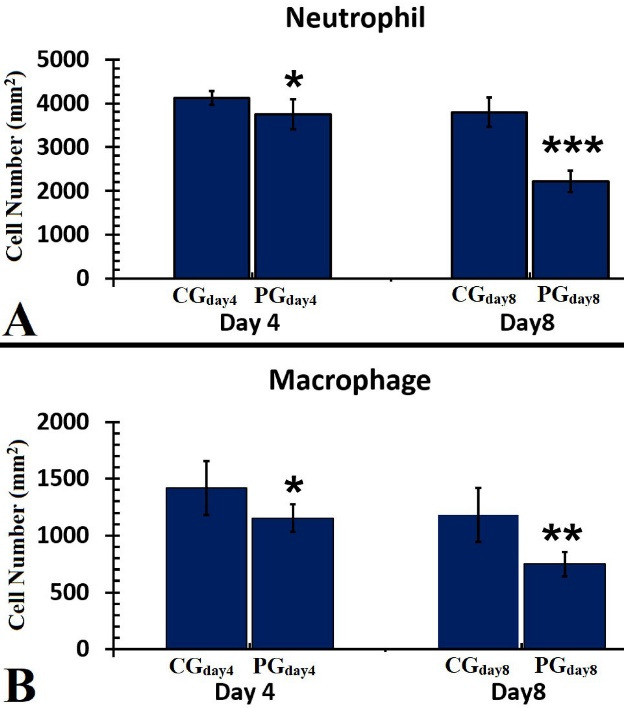

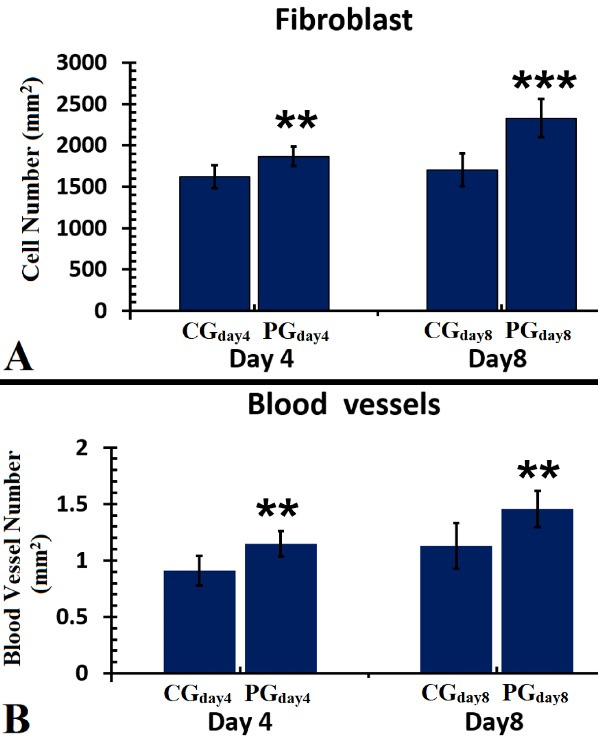

Figures 4-6 show all stereological findings among the control and PBMT groups on days 4 and 8.

Figure 4.

Hematoxylin and Eosin–Stained (H&E) Photographs of Repairing Tissues in All the Studied Groups on Days 4 and 8 After Surgery. Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PG, Photobiomodulation group

Figure 6.

A Comparison of Neutrophil (A) and Macrophage (B) Counts of the Wounds in the Studied Groups on Days 4 and 8. The independent-samples t-test was used to examine the results, which were shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PG, Photobiomodulation group

In terms of the stereological study, there were better stereological results in the PG groups than in the CG groups on both days 4 and 8. We showed better stereological results in PGday8 treatments compared to PGday4 (P < 0.05).

Fibroblasts Count

Figure 5, panel A, depicts all fibroblast findings on days 4 and 8 in the experimental groups. On both days 4 and 8, there were more fibroblasts in PGday4 (P = 0.03) and PGday8 (P = 0.000) groups than in the CG groups. The numerical density of fibroblast cells in the PGday8 groups was upper than that in the PGday4 group (P = 0.000; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A Comparison of the Wounds’ Neutrophil (A) and Macrophage (B) Levels on Days 4 and 8. The independent-samples t-test was used to examine the results, which were shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PG, Photobiomodulation group

Angiogenesis

Figure 5, panel B, shows all findings of angiogenesis in all groups on days 4 and 8. We showed that PGday4 treatments resulted in more angiogenesis than CGday4 (P= 0.003). Concurrently, the blood vessel count in the PGday8 group was greater than that in the PGday8 group (P = 0.006).

Neutrophils Count

There were lower neutrophils in PGday4 (P = 0.024) and PGday8 (P = 0.000) groups than in the similar CG groups. Concurrently, we found fewer neutrophils in PGday8 treatments compared to PGday4 (P = 0.028) (Figure 6, panel B).

Macrophage Counts

Figure 6, panel B, shows there were lower macrophages in almost all PG groups than in the CG group (P = 0.022 for PGday4, P = 0.001 for PGday8). On day 8, we discovered that the PGday8 treatment had significantly more macrophages than the PGday8 regimens (P = 0.001).

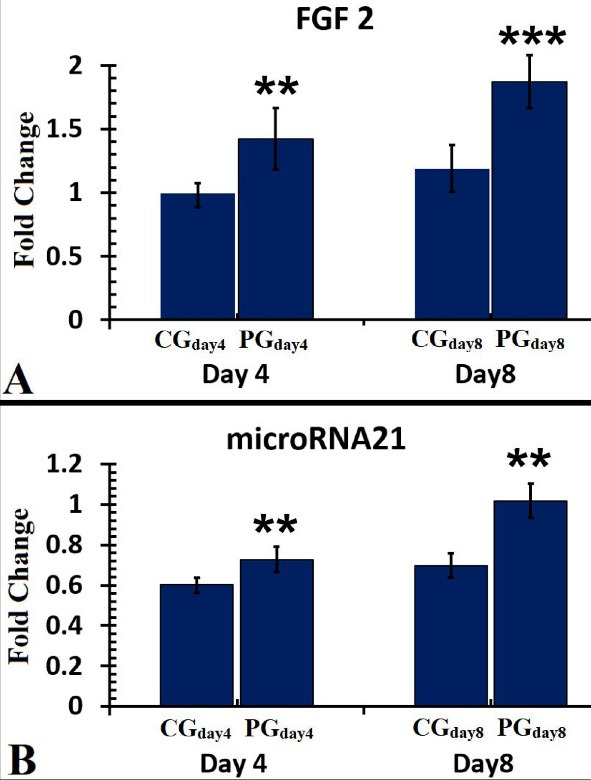

The Expression Level of FGF2

On day 4, there were advanced levels of FGF2 in the PGday4 group compared to the CGday4 group (P = 0.002). On day 8, we found that the PGday8 group had higher levels of FGF2 than the CGday8 group (P = 0.005). There were greater levels of FGF2 in the PGday8 group than in the PGday4 group (P = 0.001) (Figure 7, panel A).

Figure 7.

A Comparison of FGF2 (A) and miR-21 (B) Levels in the Injured Sites of the Studied Groups on Days 4 and 8. The data were reported as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using the independent-samples t test. **P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CG, Control group; PG, Photobiomodulation group

The Gene Expression Level of miR-21

All findings of the gene expression level of miR-21 in the wound bed on days 4 and 8 are shown in Figure 7 (panel B).

On day 4, there were greater levels of miR-21 in the PGday4 group than in the CGday4 group (P = 0.003). On day 8, the results of the PGday8 group were greater than the CGday8 (P = 0.000). The finding of the PGday8 improved in comparison with the PGday4 one (P = 0.045).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to measure the therapeutic influences of PBMT on stereological parameters, microRNA-21 expression, FGF2, ulcer size, and bacterial count in an infected, delayed, and ischemic wound repairing DM1 rat model. In summary, our findings showed that treatment regimens (PBMday4 and PBMday8) considerably reduced the microbial flora counts, improved the wound closure rate, and increased the expression of microRNA-21 and FGF2.

We also found that stereological parameters in the PBMday4 group were significantly more dominant than those in the other groups.

Today, a range of techniques have been advanced to enhance wound healing.

One of the effective techniques in medical settings and wound repair is photobiomodulation (PBM). Luckily, PBMT has been used effectively to accelerate injury repair in some non-diabetic preclinical models of ischemic tissue by increasing local blood flow and creating novel blood vessels in the ulcer environment.17

PBM is a method using lasers and/or light-emitting diodes (LEDs) to reduce inflammation and improve tissue repair.35 PBMT triggers cells to create upper energy and to experience self-renovation by applying visible red, green, and invisible near-infrared radiation.36 PBMT can enhance ADS function, proliferation, migration, and differentiation.37,38 Similar to these findings, we found that the application of a suitable mitogenic and anti-inflammatory agent, such as PBMT, improved the healing abilities of ulcers in the DM1 model of MARS ischemic and infected chronic wounds.

In this study, we also showed that the wound area was reduced by the use of PBMT, which was confirmed by an increase in the wound closure rate.

Interestingly, the induction of a bactericidal effect in the wound area was specifically enhanced by PBMT, accompanied by improved wound strength. Taken together, our findings indicate the application of PMBT, as an anti-inflammatory agent and cost-effective drug, could be helpful in PBM-based therapy in DFU treatments.

It has been proven that bacterial infections are the main causative factors in wound healing impairments.39 The widespread strain of staphylococcal, MRSA, is responsible for several wound infections and is identified to quickly advance resistance towards generally injected antibiotics. As a result, the increase and adaptation of MARS in the DFU area40 have resulted in a growth in the unrepairable staphylococcal infection spectrum.41 Therefore, there is an urgent need for some novel approaches to overcome MRSA infections and antimicrobial resistance.42 In this experiment, we specifically intended to assess the antibacterial impacts of PBMT43 because they have been shown to have antibacterial effects in animal models.

In this study, we showed that the use of PBMT can significantly decrease the microbial count compared to control groups. In line with these findings, Lipovsky et al, in a laboratory experiment, showed that PBMT (30, 60, 120 J/cm2, 100 mW, and 415 nm) inhibits Staphylococcus aureus effects by ROS generation.44 These antibacterial impacts of PBMT treatment may be attributed to the stimulation of ROS by PBMT. Kouhkheil et al examined the impacts of PBMT (890 nm, 0.2 J/cm2, 80 Hz) and human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium (CM-hBMMSC) (4 injections) alone and together on the wound strength and CFU of an MRSA-infected wound model in DM1 rats.

Kouhkheil et al found that CM-hBMMSC and PBMT alone or together significantly decreased the CFUs in comparison to the control group.25

In the study directed by Fridoni et al, the single and combined impacts of CM hBMMSC and PBMT on the stereological parameters were evaluated in an MRSA-infected wound model in rats with DM1. They concluded that the concomitant use of PBMT and CM-hBMMSC had anti-inflammatory and neo-vascular effects and accelerated the healing of skin damage in the MARS-infected wound model in DM1 rats.45 DFUs are described as being stuck in a persistent inflammatory state characterized by the accumulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as inflammatory cells and proteases. Accordingly, in the current study, the improved numbers of neutrophils and macrophages were detected in the control group on days 4 and 8.

Kim et al reported that the regular transmissions from the inflammation stage to the tissue restoration phase for the renewal of ECM are particularly critical for repairing damaged tissue. In addition, they showed that endothelial and fibroblast cells are the key cells involved in the remodeling of the ECM and angiogenesis for proper wound closure.46 In line with Kim and colleagues’ conclusion, in cases of fibroblasts and angiogenesis, our results showed that all experimental groups revealed significantly more blood vessels and fibroblast cell counts than the control group.

Overall, the use of PBMT (PGday4&8) presented the best significant results in increasing fibroblasts and blood vessels compared to control groups.

In this study, we found that PBMT can improve stereological parameters as well as FGF2 levels in the ECM during the proliferative and inflammatory phases of the injury-repairing process in TIDM rats. Concurrently, the results of the stereological and FGF2 examinations in the PGday8 group were significantly superior to those in the PGday4 group.

FGF2 encourages endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis while preventing endothelial cells from dying. Cell specification, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival are all controlled by FGF and miRNA signalling.7

One of our study’s distinctive findings is the amount of miR-21 and FGF2 gene expression. Although the findings of gene miR-21 gene expression level in PBMT groups were greater than the control one during the proliferative stage, the data of the PGday8 group were considerably higher than the other groups. As a result, our data show that our experimental groups, particularly the PGday8 group, performed well. Increased expression of miR-21 increases the proliferative response, decreases the inflammatory reaction, and increases wound repair.47 Liechty et al reported that miR-21 is complicated in the control of inflammation. Abnormal secretion of miR-21 may clarify the unusual inflammation and insistent polarization of macrophages shown in diabetic wounds.13 Wu et al showed that MiR-21-3p improved the function of fibroblasts and enhanced wound repairing in vivo by directly targeting protein sprout homolog 1 (SPRY1). They concluded that miR-21-3p may improve DFUs by decreasing SPRY1.11

Treatment with PBMT increases fibroblast numbers and FGF2 expression decreases inflammation in the wound bed and allows the ischemic and delayed wound healing model (IDHWM) to progress to the remodeling and proliferative stages of wound repairing. This is supported by our results from current and previous studies. PBMT not only demonstrates a statistically significant rise in granulation tissue (new dermal volume) formation at the proliferative stage of wound repairing in the treatment groups but also improves the tensile strength and wound closure rate at the remodeling phase.48 According to the results of our control group, there are pieces of evidence to propose that there is abnormal regulation of the inflammatory and proliferative phases as well, which can be seen in diabetic skin as increased neutrophil and macrophage counts and decreased values of miR-21 and FGF2 in the wound bed.49-51 According to our research, the lesser expression of miR-21 and FGF2 in the control group, which was increased by PBMT therapies, may be connected to the intrinsic dysregulation of inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling in this group. According to these findings, several pertinent studies have shown that miR-21 is crucial for the healing of wounds by forming a complex with its target genes (such as RECK, PTEN, SPRY 1/2, TIMP3, and NF(B)) and cascaded signaling pathways (such as ERK/MAPK, Akt/PI3K, catenin/Wnt /MMP-7, and TGF- Smad2/3-Smad7).

The stimulation of fibroblast differentiation, enhancement of new vessel formation, anti-inflammatory effects, augmentation of collagen production, and re-epithelialization of the injury may all be linked to miR-21’s therapy efficacy.9,51 Jie Xie et al reported that miRNA-21 exerts anti-inflammatory activities and ameliorates injury repairing by controlling the expression of NF-B by PDCD4.9

However, the level of MiR-21 expression significantly declined in diabetic injuries.9,52,53 Reduced levels of miR-21 also have a close relationship with the amplified expression level of its target gene. Therefore, increasing the level of miRNA-21 in damaged tissue can reduce inflammatory signals and improve healing.52

There are some limitations to this experimental investigation. The main limitations included the lack of immunohistochemistry data, associated genes and proteins, and biochemical factors implicated in skin wound healing such as oxidative stress and/or nitric oxide generation pathways which were due to budget restrictions.54

Another limitation was the use of only one micro-RNA due to budget restrictions. While many microRNAs are involved in the regulation of the wound healing process in the current study we studied only the effect of microRNA-21 on wound healing under the influence of PBM, which could be considered a limitation for the current study.

Furthermore, several other factors that were not examined in this study might be the reason of delayed healing. The study’s limited number of rats in each group might potentially be viewed as a potential weakness.

Conclusion

PBMT significantly improved injury repair in TIDM1 rats by lowering microbial counts, decreasing inflammatory cells like neutrophils and macrophages in the inflammatory phase, and increasing stereological parameters like fibroblast cells and blood vessels, as well as modifying microRNA-21 and FGF2 expression in the prolative phase. In terms of ulcer area size and body weight and blood glucose, the PBMT treatment groups were better than the control groups. As a result, PBMT treatment provides effective therapeutic results due to its moderating effects on the anti-inflammatory and proliferative characteristics of wounds.

Acknowledgments

The “Research Department of the School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences” has provided financial support for this article (Grant No. 25974).

Competing Interests

All the authors declare they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The experiment was authorized by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), Tehran, Iran, School of Medicine’s Medical Ethics Department (Ethics no. IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1400.295).

Please cite this article as follows: Amini A, Ghasemi Moravej F, Mostafavinia A, Ahmadi H, Chien S, Bayat M. Photobiomodulation therapy improves inflammatory responses by modifying stereological parameters, microRNA-21 and FGF2 expression. J Lasers Med Sci. 2023;14:e16. doi:10.34172/jlms.2023.16.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 Suppl 1:S5–S10. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fridoni M, Kouhkheil R, Abdollhifar MA, Amini A, Ghatrehsamani M, Ghoreishi SK, et al. Improvement in infected wound healing in type 1 diabetic rat by the synergistic effect of photobiomodulation therapy and conditioned medium. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(6):9906–16. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catrina SB, Zheng X. Disturbed hypoxic responses as a pathogenic mechanism of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32 Suppl 1:179–85. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brancato SK, Albina JE. Wound macrophages as key regulators of repair: origin, phenotype, and function. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duraisamy Y, Slevin M, Smith N, Bailey J, Zweit J, Smith C, et al. Effect of glycation on basic fibroblast growth factor induced angiogenesis and activation of associated signal transduction pathways in vascular endothelial cells: possible relevance to wound healing in diabetes. Angiogenesis. 2001;4(4):277–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1016068917266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grazul-Bilska AT, Luthra G, Reynolds LP, Bilski JJ, Johnson ML, Adbullah SA, et al. Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) on proliferation of human skin fibroblasts in type II diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2002;110(4):176–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf L, Gao CS, Gueta K, Xie Q, Chevallier T, Podduturi NR, et al. Identification and characterization of FGF2-dependent mRNA: microRNA networks during lens fiber cell differentiation. G3 (Bethesda) 2013;3(12):2239–55. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.008698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li D, Landén NX. MicroRNAs in skin wound healing. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27(S1):12–4. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2017.3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie J, Wu W, Zheng L, Lin X, Tai Y, Wang Y, et al. Roles of microRNA-21 in skin wound healing: a comprehensive review. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:828627. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.828627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang T, Feng Y, Sun H, Zhang L, Hao L, Shi C, et al. miR-21 regulates skin wound healing by targeting multiple aspects of the healing process. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(6):1911–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Zhang K, Liu R, Zhang H, Chen D, Yu S, et al. MicroRNA-21-3p accelerates diabetic wound healing in mice by downregulating SPRY1. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(15):15436–45. doi: 10.18632/aging.103610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang SY, Kim H, Kwak G, Jo SD, Cho D, Yang Y, et al. Development of microRNA-21 mimic nanocarriers for the treatment of cutaneous wounds. Theranostics. 2020;10(7):3240–53. doi: 10.7150/thno.39870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liechty C, Hu J, Zhang L, Liechty KW, Xu J. Role of microRNA-21 and its underlying mechanisms in inflammatory responses in diabetic wounds. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3328. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatt K, Lanting LL, Jia Y, Yadav S, Reddy MA, Magilnick N, et al. Anti-inflammatory role of microRNA-146a in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(8):2277–88. doi: 10.1681/asn.2015010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sekar D, Venugopal B, Sekar P, Ramalingam K. Role of microRNA 21 in diabetes and associated/related diseases. Gene. 2016;582(1):14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy D, Modi A, Khokhar M, Sankanagoudar S, Yadav D, Sharma S, et al. MicroRNA 21 emerging role in diabetic complications: a critical update. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2021;17(2):122–35. doi: 10.2174/1573399816666200503035035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cury V, Moretti AI, Assis L, Bossini P, de Souza Crusca J, Neto CB, et al. Low level laser therapy increases angiogenesis in a model of ischemic skin flap in rats mediated by VEGF, HIF-1α and MMP-2. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2013;125:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi H, Amini A, Fadaei Fathabady F, Mostafavinia A, Zare F, Ebrahimpour-Malekshah R, et al. Transplantation of photobiomodulation-preconditioned diabetic stem cells accelerates ischemic wound healing in diabetic rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):494. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01967-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park IS, Mondal A, Chung PS, Ahn JC. Prevention of skin flap necrosis by use of adipose-derived stromal cells with light-emitting diode phototherapy. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(3):283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karu T. Is it time to consider photobiomodulation as a drug equivalent? Photomed Laser Surg. 2013;31(5):189–91. doi: 10.1089/pho.2013.3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saltmarche AE. Low level laser therapy for healing acute and chronic wounds - the extendicare experience. Int Wound J. 2008;5(2):351–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallahnezhad S, Piryaei A, Tabeie F, Nazarian H, Darbandi H, Amini A, et al. Low-level laser therapy with helium-neon laser improved viability of osteoporotic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from ovariectomy-induced osteoporotic rats. J Biomed Opt. 2016;21(9):98002. doi: 10.1117/1.jbo.21.9.098002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Cellular and molecular basis of wound healing in diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1219–22. doi: 10.1172/jci32169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moradi A, Zare F, Mostafavinia A, Safaju S, Shahbazi A, Habibi M, et al. Photobiomodulation plus adipose-derived stem cells improve healing of ischemic infected wounds in type 2 diabetic rats. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1206. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouhkheil R, Fridoni M, Abdollhifar MA, Amini A, Bayat S, Ghoreishi SK, et al. Impact of photobiomodulation and condition medium on mast cell counts, degranulation, and wound strength in infected skin wound healing of diabetic rats. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2019;37(11):706–14. doi: 10.1089/photob.2019.4691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amini A, Pouriran R, Abdollahifar MA, Abbaszadeh HA, Ghoreishi SK, Chien S, et al. Stereological and molecular studies on the combined effects of photobiomodulation and human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium on wound healing in diabetic rats. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;182:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fadaie Fathabadie F, Bayat M, Amini A, Bayat M, Rezaie F. Effects of pulsed infra-red low level-laser irradiation on mast cells number and degranulation in open skin wound healing of healthy and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15(6):294–304. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2013.764435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mostafavinia A, Amini A, Ghorishi SK, Pouriran R, Bayat M. The effects of dosage and the routes of administrations of streptozotocin and alloxan on induction rate of type1 diabetes mellitus and mortality rate in rats. Lab Anim Res. 2016;32(3):160–5. doi: 10.5625/lar.2016.32.3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furman BL. Streptozotocin-induced diabetic models in mice and rats. Curr Protoc. 2021;1(4):e78. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pouriran R, Piryaei A, Mostafavinia A, Zandpazandi S, Hendudari F, Amini A, et al. The effect of combined pulsed wave low-level laser therapy and human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium on open skin wound healing in diabetic rats. Photomed Laser Surg. 2016;34(8):345–54. doi: 10.1089/pho.2015.4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kouhkheil R, Fridoni M, Piryaei A, Taheri S, Chirani AS, Anarkooli IJ, et al. The effect of combined pulsed wave low-level laser therapy and mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium on the healing of an infected wound with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal aureus in diabetic rats. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(7):5788–97. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moradi A, Kheirollahkhani Y, Fatahi P, Abdollahifar MA, Amini A, Naserzadeh P, et al. An improvement in acute wound healing in mice by the combined application of photobiomodulation and curcumin-loaded iron particles. Lasers Med Sci. 2019;34(4):779–91. doi: 10.1007/s10103-018-2664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khosravi Maharlooei M, Bagheri M, Solhjou Z, Moein Jahromi B, Akrami M, Rohani L, et al. Adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cell (AD-MSC) promotes skin wound healing in diabetic rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93(2):228–34. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bagheri M, Mostafavinia A, Abdollahifar MA, Amini A, Ghoreishi SK, Chien S, et al. Combined effects of metformin and photobiomodulation improve the proliferation phase of wound healing in type 2 diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;123:109776. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dompe C, Moncrieff L, Matys J, Grzech-Leśniak K, Kocherova I, Bryja A, et al. Photobiomodulation-underlying mechanism and clinical applications. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1724. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Da Silva D, Crous A, Abrahamse H. Photobiomodulation: an effective approach to enhance proliferation and differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells into osteoblasts. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:8843179. doi: 10.1155/2021/8843179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crous A, van Rensburg MJ, Abrahamse H. Single and consecutive application of near-infrared and green irradiation modulates adipose derived stem cell proliferation and affect differentiation factors. Biochimie. 2022;196:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zare F, Moradi A, Fallahnezhad S, Ghoreishi SK, Amini A, Chien S, et al. Photobiomodulation with 630 plus 810 nm wavelengths induce more in vitro cell viability of human adipose stem cells than human bone marrow-derived stem cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;201:111658. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edwards R, Harding KG. Bacteria and wound healing. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17(2):91–6. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boulton AJM, Armstrong DG, Kirsner RS, Attinger CE, Lavery LA, Lipsky BA, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Diabetic Foot Complications. Arlington, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2018. [PubMed]

- 41.Smith TL, Pearson ML, Wilcox KR, Cruz C, Lancaster MV, Robinson-Dunn B, et al. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus Glycopeptide-Intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Working Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(7):493–501. doi: 10.1056/nejm199902183400701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mot YY, Othman I, Sharifah SH. Synergistic antibacterial effect of co-administering adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells and Ophiophagus hannah L-amino acid oxidase in a mouse model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-infected wounds. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0457-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ranjbar R, Ashrafzadeh Takhtfooladi M. The effects of low level laser therapy on Staphylococcus aureus infected third-degree burns in diabetic rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2016;31(4):250–5. doi: 10.1590/s0102-865020160040000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipovsky A, Nitzan Y, Gedanken A, Lubart R. Visible light-induced killing of bacteria as a function of wavelength: implication for wound healing. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42(6):467–72. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fridoni M, Kouhkheil R, Abdollhifar MA, Amini A, Ghatrehsamani M, Ghoreishi SK, et al. Improvement in infected wound healing in type 1 diabetic rat by the synergistic effect of photobiomodulation therapy and conditioned medium. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(6):9906–16. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim H, Kim DE, Han G, Lim NR, Kim EH, Jang Y, et al. Harnessing the natural healing power of colostrum: bovine milk-derived extracellular vesicles from colostrum facilitating the transition from inflammation to tissue regeneration for accelerating cutaneous wound healing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11(6):e2102027. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202102027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Madhyastha R, Madhyastha H, Nakajima Y, Omura S, Maruyama M. MicroRNA signature in diabetic wound healing: promotive role of miR-21 in fibroblast migration. Int Wound J. 2012;9(4):355–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmadi H, Amini A, Fadaei Fathabady F, Mostafavinia A, Zare F, Ebrahimpour-Malekshah R, et al. Transplantation of photobiomodulation-preconditioned diabetic stem cells accelerates ischemic wound healing in diabetic rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):494. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01967-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geiger A, Walker A, Nissen E. Human fibrocyte-derived exosomes accelerate wound healing in genetically diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;467(2):303–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy S, Sen CK. miRNA in wound inflammation and angiogenesis. Microcirculation. 2012;19(3):224–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trzyna A, Banaś-Ząbczyk A. Adipose-derived stem cells secretome and its potential application in “stem cell-free therapy”. Biomolecules. 2021;11(6):878. doi: 10.3390/biom11060878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Q, Zhao H, Chen W, Huang P, Bi J. Human keratinocyte-derived microvesicle miRNA-21 promotes skin wound healing in diabetic rats through facilitating fibroblast function and angiogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;114:105570. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.105570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raziyeva K, Kim Y, Zharkinbekov Z, Kassymbek K, Jimi S, Saparov A. Immunology of acute and chronic wound healing. Biomolecules. 2021;11(5):700. doi: 10.3390/biom11050700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breulmann FL, Hatt LP, Schmitz B, Wehrle E, Richards RG, Della Bella E, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic potential of microRNAs for fracture healing processes and non-union fractures: a systematic review. Clin Transl Med. 2023;13(1):e1161. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]