Abstract

Background and Aims:

Cross-sectional studies on sexual function in men with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) yield mixed results. Using a prospective incidence cohort, we aimed to describe sexual function at baseline and over time and to identify factors associated with impaired sexual function in men with IBD.

Methods:

Men 18 years and older enrolled between April 2008 and January 2013 in the Ocean State Crohn’s and Colitis Area Registry (OSCCAR) with a minimum of 2 years of follow-up were eligible for study. Male sexual function was assessed using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), a self-administered questionnaire that assesses 5 dimensions of sexual function over the most recent 4 weeks. To assess changes in the IIEF per various demographic and clinical factors, linear mixed effects models were used.

Results:

Sixty-nine of 82 eligible men (84%) completed the questionnaire (41 Crohn’s disease, 28 ulcerative colitis). The mean age (SD) of the cohort at diagnosis was 43.4 (19.2) years. At baseline, 39% of men had global sexual dysfunction, and 94% had erectile dysfunction. Independent factors associated with erectile dysfunction are older age and lower physical and mental component summary scores on the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).

Conclusion:

In an incident cohort of IBD patients, most men had erectile dysfunction. Physicians should be aware of the high prevalence of erectile dysfunction and its associated risk factors among men with newly diagnosed IBD to direct multidisciplinary treatment planning.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, sexual function, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) that often present between the second and fourth decades of life, when sexual identity and relationships are developing.1 Sexual function is one of the top concerns expressed by patients with IBD yet remains poorly explored by researchers and clinicians.2 Furthermore, it is recognized that there are both frequent and complex direct and indirect effects from numerous chronic diseases on sexual health.3 Despite this, in a worldwide survey, only 9% of randomly selected individuals reported being asked about sexual health by their doctor, suggesting that sexual health is rarely addressed in a clinical setting.4

Regarding men with IBD, there is a paucity of literature describing sexual function in this population. Moody et al first published on this topic in 1993 and reported no difference in sexual frequency between men with IBD and non-IBD controls.5 However, they noted patients’ disease-related concerns and their potential impact on sexual function.5 In 2007, Timmer et al explored these concerns further and noted that 44% of men felt severely compromised sexually due to their IBD, with greater dysfunction noted among men with active disease.6 In 2013, Marin et al found that men with IBD had significantly lower scores in the erectile function and desire domains of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF).7 A more recent study found no association between IBD and sexual male dysfunction, but 92% of the participants were in clinical remission.8 Studies on sexual function among men with IBD are few and limited by cross-sectional design, poor response rates, lack of use of well-validated instruments to measure disease factors and sexual function, and variability of disease duration. Sexual function in men with newly diagnosed IBD has not been previously described.

The aims of this study were to describe baseline characteristics and changes in sexual function over time in a prospective cohort of men with newly diagnosed IBD in a community population and to identify factors associated with male sexual dysfunction.

METHODS

Study Subjects

The Ocean State Crohn’s and Colitis Area Registry (OSCCAR) is a community-based, prospective, inception cohort of newly diagnosed IBD patients residing in the state of Rhode Island. The objectives of OSCCAR include the characterization of clinical and subclinical factors that contribute to disease outcomes in IBD. Between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2012, 408 patients were enrolled in OSCCAR. Most subjects were enrolled within 1 year of diagnosis, with a median time to enrollment of 60 days from diagnosis. Inflammatory bowel disease was diagnosed based on signs and symptoms consistent with the diagnosis and confirmed on endoscopy, radiographic imaging, and/or histopathology.1

Eligible patients for our study were men age 18 or older, enrolled in OSCCAR within 1 year of IBD diagnosis, who completed the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), and had at least 2 years of follow-up.

Sexual Function Measurement

The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) is a widely used, multidimensional, 15-item questionnaire validated for the evaluation of male sexual function.9 It spans 5 domains of sexual functioning: erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and overall satisfaction. The erectile function domain has been validated as a tool for diagnosing and classifying levels of erectile dysfunction (ED) severity.10 The IIEF has a high degree of internal consistency (Cronbach alpha 0.91), adequate construct validity, and highly significant test-retest repeatability correlation coefficients for the 5 domain scores.10 Scores range from 5 to 75, with higher scores representing better sexual function. A score of 43 is the cutoff used for sexual dysfunction as previously done by other studies.7 A cutoff score of 25 in the erectile function domain has been shown to be optimal in distinguishing between men with and without ED.9 Patients are asked to reflect on the most recent 4 weeks when answering each question.

Patient-reported Outcomes

At scheduled intervals, subjects in OSCCAR were administered instruments to measure quality of life, symptoms, and psychological well-being and to assess medication use and surgical history. Additional data elements were also recorded by standardized chart review of the subjects’ medical record. Standardized study instruments used in this study were the Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-8), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) Scale, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ), and Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).

The Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale is a standardized, validated tool used to diagnose and measure severity of depression; a score ≥10 corresponds to clinically significant depression.11 Collection of PHQ-8 data began in October 2009 and was available for 61 (26 UC, 35 CD) men eligible for the current study.

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue Scale is an instrument that comprises 13 items that are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 52, with lower scores corresponding to greater fatigue. The FACIT-F has been validated in the general population and in various chronic conditions, including IBD.12–18

The Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire is a valid, reliable assessment tool that measures disease-specific quality of life across 4 dimensions of functioning: bowel, social, systemic, and emotional.19, 20 The questionnaire consists of 32 items, each scored from 1 to 7. Composite scores range from 32 to 224, with higher scores representing better quality of life.

The Short Form Health Survey is a validated instrument that comprises a set of quality of life measures. It consists of 8 subscales that can be aggregated in 2 distinct, higher-order summary scores: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS).21, 22 The study protocol was approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Rhode Island Hospital institutional review boards beginning August 29, 2007, and the approvals for use of quality of life measures were obtained from copyright holders.

Statistical Analysis

The main variables were summarized using means and percentages. The differences between CD and UC were assessed using a t test for continuous variables, and the Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables.

In the assessment of changes during the 2 years of follow-up, the data were modeled using linear mixed-effect models with year as a fixed effect and a random intercept for each patient and an AR(1) correlation structure. For binary variables, a logistic regression model was considered, and the coefficients were estimated using generalized estimating equations with unconstrained correlation.

Association between variables and the IIEF score were evaluated using data available from all years. A mixed effect model was used considering the covariates (either categorical or continuous) and time as fixed effect and a random intercept for each patient. P values were adjusted for multiple hypotheses using the Benjamini-Hochberg approach.

In the multivariable analysis, the same mixed-model approach was used considering variables with P < 0.2 in the univariate analysis. We found that there was a high correlation between IBDQ score, FACIT, PHQ-8, and SF-36 leading to multicollinearity in the model. To avoid this, IBDQ score was eliminated as >30% of the values were missing and FACIT; PHQ-8 were excluded because the estimated variance inflated factor (VIF) was greater than 3.5. All calculations were done using R (version 3.3.2).

RESULTS

Study Population and Sexual Function

Of the 82 eligible subjects, 69 men completed the IIEF (41 CD, 28 UC). Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographics, disease characteristics, and medical history of the study population. On average, men with CD had significantly higher PHQ-8 scores, lower FACIT scores, and lower IBDQ scores compared with men with UC (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Demographics, Disease Characteristics and History

| Crohn’s (n = 41) | Ulcerative Colitis (n = 28) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at enrollment (s.d.) | 40.4 (16.7) | 42.9 (16.5) | 0.56 |

| Age categories | 0.9 | ||

| 18–29, n (%) | 13 (32) | 8 (29) | |

| 30–44, n (%) | 10 (24) | 6 (21) | |

| 45–65, n (%) | 14 (34) | 12 (43) | |

| >65, n (%) | 4 (10) | 2 (7) | |

| Race | 1 | ||

| White, n (%) | 40 (98) | 27 (96) | |

| Other, n (%) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | |

| Hispanic or Latino origin | 0.90 | ||

| No, n (%) | 38 (93) | 27 (96) | |

| Yes, n (%) | 3 (7) | 1 (4) | |

| Marital status | 0.33 | ||

| Married, n (%) | 17 (42) | 12 (43) | |

| Single/never married, n (%) | 21 (51) | 10(36) | |

| Divorced/separated, n (%) | 3 (7) | 4 (14) | |

| Cohabitating, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | |

| Widowed, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | |

| Smoking status | 0.09 | ||

| Never smoked, n (%) | 26 (63) | 13 (46) | |

| Former smoker, n (%) | 9 (22) | 13 (46) | |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 6 (14.6) | 2 (7.1) | |

| Mean BMI (s.d.) | 28.5 (7.3) | 30.2 (15.3) | 0.60 |

| Disease activity | |||

| HBI, mean score (s.d.) | 3.5 (3.8) | n.a | n.a |

| SCCAI, mean score (s.d.) | n.a | 2.7 (2.5) | n.a |

| Symptoms | |||

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 25 (61) | 17 (61) | 1 |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 35 (85) | 25 (89) | 0.39 |

| Stool incontinence, n (%) | 12 (29) | 13 (46) | 0.12 |

| Medication use | |||

| Prednisone or IV corticosteroids, n (%) | 4 (10) | 3 (11) | 1 |

| Budesonide, n (%) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.51 |

| Biologic Therapies, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Quality of Life Measures | |||

| Mean SF-36 Physical Health Component (s.d.)a | 46.4 (9.6) | 51.3 (8.9) | 0.06 |

| Mean SF-36 Mental Health Component (s.d.)a | 46.1 (13.3) | 49.3 (11.2) | 0.34 |

| Mean IBDQ score (s.d.) | 166.2 (35.9) | 180.1 (22.2) | 0.05 |

| Mean FACIT score (s.d.) | 35.7 (12.6) | 42.5 (8.5) | 0.009 |

| Mean PHQ-8 score (s.d.)b | 5.2 (5.7) | 2.3 (3.0) | 0.02 |

| CD Location per Montreal Classificationc | n.a | ||

| L1 ileal | 9 (22) | n.a | |

| L2 colonic | 19 (46) | n.a | |

| L3 ileocolonic | 11 (27) | n.a | |

| L4 isolated upper diseased | 12 (29) | n.a | |

| CD Behavior per Montreal Classification | n.a | ||

| B1 non-stricturing, non-penetrating | 30 (73) | n.a | |

| B2 stricturing | 7 (17) | n.a | |

| B3 penetrating | 3 (7) | n.a | |

| P perianal disease | 4 (5) | n.a | |

| UC Location per Montreal Classification | n.a | ||

| E1 Proctitis | n.a | 2 (7) | |

| E2 Left-sided colitis | n.a | 14 (50) | |

| E3 Pancolitis | n.a | 12 (43) | |

| Extra-intestinal manifestations | n.ae | ||

| Musculoskeletal | 0 | 1 | |

| Ocular | 0 | 1 | |

| Dermatologic | 0 | 0 |

s.d., standard deviation; n.a., not applicable

Data available for 31 CD patients and 24 UC patients

Data available for 35 CD patients and 26 UC patients

Data available for 39 CD patients for L1-L3

Data available for 16 CD patients

Sample size inadequate for statistical analysis

Baseline mean IIEF score (SD) was 43.4 (19.2) overall (42.1 [19.3] CD, 45.3 [19.4] UC; P = 0.509), corresponding to sexual dysfunction in 39.1% men at baseline, defined as an IIEF score less than 43, with similar rates for UC and CD (35.7% in UC, 41.5% in CD; P = 0.8).

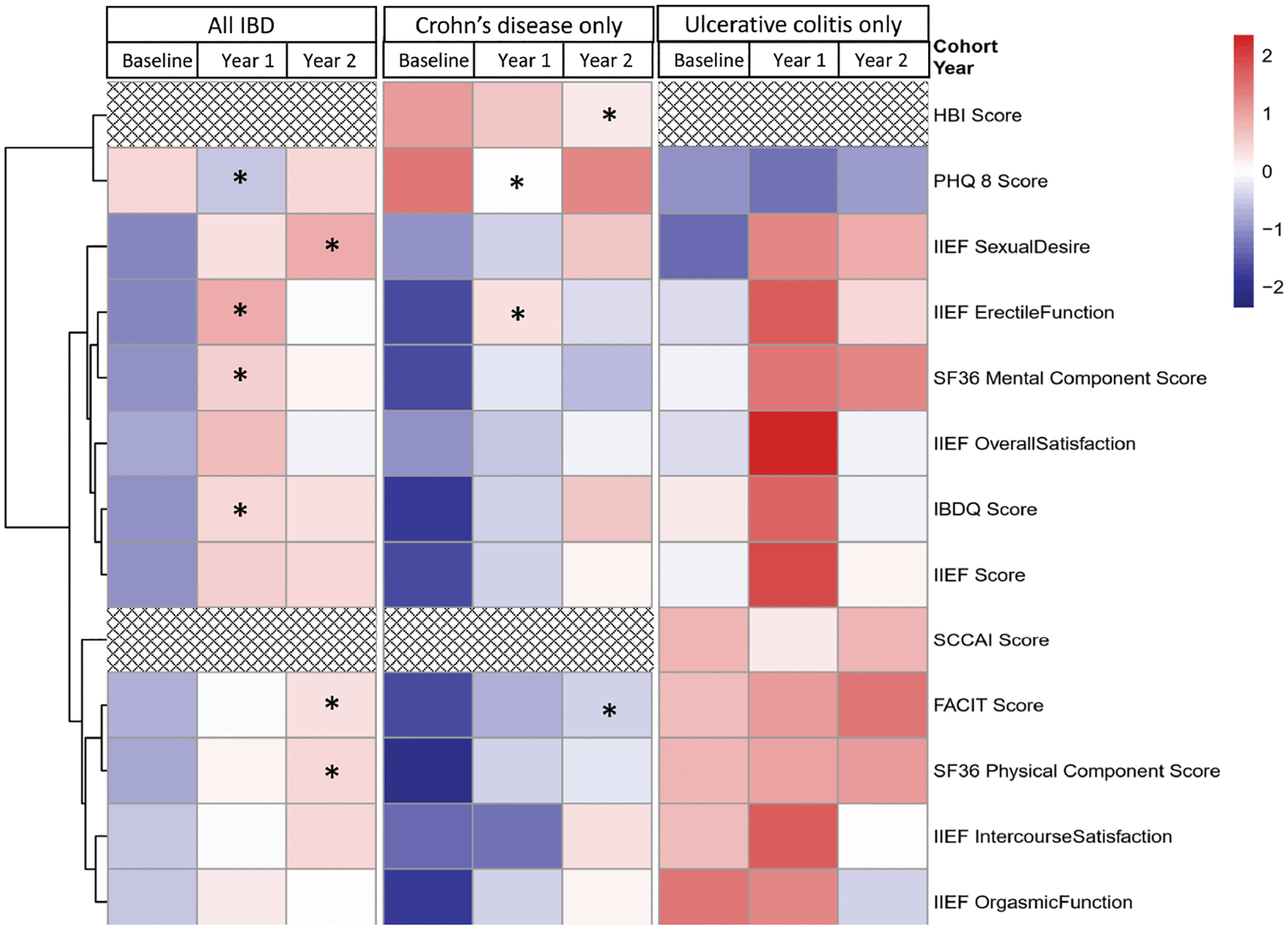

Throughout the duration of the study, there was no significant change in mean IIEF score (P = 0.181 overall; P = 0.224 for CD; P = 0.33 for UC) (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in mean IIEF score between CD and UC over time (ANOVA, P = 0.68).

FIGURE 1.

Heat map and dendrogram of relative changes in IIEF, disease and quality of life scores over time, according to IBD type. * P < 0.05. The heat map is a graphical representation of the mean of various clinical factors assessed in the study (in rows) at each time point overall and by disease subtype (columns). Colors represent the estimated mean for each time point and have been normalized for each score. Red represents higher scores, while blue represents lower scores. Stars indicate a significant increase from baseline was observed for that timepoint and patient subgroup. The dendrogram, represented by the tree-structured graph on the left of the figure, shows the result of unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the clinical variables whose change in time was studied. The heatmap is thus ordered by the relative distance between the variables, so that factors with similar changes over time are kept in close proximity and belong to the same cluster. The overall similarity of the cluster is indicated by height of the dendrogram corresponding to a cluster branch. For example, although at baseline FACIT scores for Crohn’s are lower than UC, FACIT scores increase over time reaching significance at year 2. This trend is very similar to SF-36 Physical Component Score.

Using the standard cutoff score of 25 for the erectile dysfunction domain, 94.2% of men in our cohort suffered from erectile dysfunction at baseline, and this did not significantly change over time (P = 0.94). Significant changes over time for the other domains (ie, intercourse satisfaction, sexual desire, orgasmic function, and overall satisfaction) were not seen (ANOVA, P > 0.05).

Sexual Function and Disease Activity

Figure 1 shows the mean scores of study measurements across all 3 time points. Colors represent the estimated mean for each time point and have been normalized for each score. Red represents higher scores, and blue represents lower scores. Among men with CD, mean Harvey–Bradshaw index (HBI) scores at baseline, year 1, and year 2 were 3.5, 3.1, and 2.5, respectively. There was a significant change between baseline and year 2 (P = 0.03), which is indicated with an asterisk in Figure 1. Among men with UC, mean Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) scores at baseline, year 1, and year 2 were 2.7, 2.0, and 2.7, respectively. There was no significant change between baseline and the other 2 time points. Among all men with IBD and CD, there was no significant association between disease activity and sexual function (Table 2). Men with UC were found to have a significant association between SCCAI score and the erectile function domain (P = 0.003), but this did not remain significant after adjustment for multiple hypotheses (Table 2). On multivariable analysis, disease activity was not found to be independently associated with global sexual function (results not shown).

TABLE 2.

Associations Between IIEF Total and Domain Scores and Various Factors Among All Men Across 2 Years: Univariate Analysis

| Variable | Unadjusted Estimate (95% CI) | Unadjusted P | Adjusted Pa | IIEF Domain(s) With Significant Associations (Unadjusted P, adjusted Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (continuous age with 1-year increments) | −0.12 (−0.36, 0.12) | 0.32 | 0.51 | Erectile function (0.01, 0.08) |

| Single marital statusb | 7.24 (−0.6, 15.1) | 0.07 | 0.35 | Orgasmic function (0.005, 0.123) |

| Overall satisfaction (0.008, 0.16) | ||||

| Smoking status (Current/former smoker vs nonsmoker) | 6.12 (−1.81, 14.06) | 0.13 | 0.39 | Orgasmic function (0.02, 0.21) |

| IBD subtype (UC vs CD) | 3.25 (−4.85,11.35) | 0.43 | 0.59 | |

| Disease activity | ||||

| HBI (CD only) | −0.5 (−1.57, 0.58) | 0.07 | 0.54 | |

| SCCAIc (UC only) | −1.28 (−3.25, 0.69) | 0.003 | 0.39 | Overall satisfaction (0.02, 0.16) |

| Quality of life measures | ||||

| IBDQ score | 0.11 (0, 0.21) | 0.06 | 0.35 | Erectile function (0.003, 0.03) |

| Sexual Desire (0.05, 0.31) | ||||

| Overall satisfaction (0.03, 0.16) | ||||

| SF-36 Mental Component Summaryc | 0.19 (−0.12, 0.49) | 0.22 | 0.39 | Erectile function (0.004, 0.03) |

| Overall satisfaction (0.05, 0.17) | ||||

| SF-36 Physical Component Summaryc | 0.52 (0.13, 0.91) | 0.01 | 0.24 | Erectile function (0, 0.001) |

| Overall satisfaction (0.05, 0.17) | ||||

| PHQ-8 scored | −0.72 (−1.36, −0.09) | 0.03 | 0.32 | Intercourse satisfaction (0.02, 0.52) |

| Overall satisfaction (0.02, 0.16) | ||||

| Anxiety | 1.37 (−0.64, 3.37) | 0.18 | 0.39 | Erectile function (0.04, 0.12) |

| Overall satisfaction (0.03, 0.16) | ||||

| FACIT-F score | 0.23 (−0.04, 0.49) | 0.1 | 0.39 | Erectile function (0.02, 0.09) |

| Symptomse | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 2 (−3.35, 7.34) | 0.46 | 0.59 | |

| Diarrhea | 3.36 (−1.99, 8.71) | 0.22 | 0.39 | Orgasmic function (0.03, 0.21) |

| Stool incontinence | −3.29 (−8.69, 2.11) | 0.23 | 0.39 | Sexual desire (0.04, 0.31) |

| Medication use | ||||

| Prednisone or IV corticosteroids | −1.75 (−7.36, 3.86) | 0.54 | 0.61 | |

| Biologics | 3.36 (−1.99, 8.71) | 0.22 | 0.39 | |

| Budesonide | 5.21 (−2.09, 12.5) | 0.16 | 0.39 | |

| CD Location per Montreal Classification (L1-3)f | 0.76 | 0.82 | ||

| L1 | 48.4 (37.1, 59.7) | |||

| L2 | 43.74 (36.0, 51.54) | |||

| L3 | 38.97 (19.07, 58.88) | |||

| CD Behavior per Montreal Classification (B1-3)g | 0.79 | 0.82 | ||

| B1 | 45.07 (38.68, 51.47) | |||

| B2 | 41.87 (28.91, 54.82) | |||

| B3 | 38.97 (19.07, 58.88) | |||

| P perianal disease modifier | 8.26 (−16.53, 33.05) | 0.08 | 0.61 | |

| UC Location per Montreal Classification (E1-E3)g | 0.47 | 0.59 | ||

| E1 | 61.05 (37.14, 84.95) | |||

| E2 | 45.91 (36.86, 54.95) | |||

| E3 | 46.04 (36.28, 55.81) | |||

CI, confidence interval

P-value adjusted for false discovery rate.

Sexual function by marital status analyzed as single or cohabitating vs. married, divorced/separated and widowed.

Data available for 55 subjects for SF-36

Data available for 61 subjects

Data available for 67 subjects for abdominal pain, 58 subjects for diarrhea and 59 subjects for stool incontinence

Data available for 39 subjects

Data available for 40 subjects

Sexual Function and Age, Marital Status, Smoking Status

Multivariable analysis showed that younger age was independently associated with higher total IIEF scores (results not shown) and erectile function domain scores (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Associations between Total Erectile Function and Demographic and Clinical Factors: Multivariable Analysis Without Imputation

| Estimate (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| SF-36 PCS (every 10 points) | 1.30 (0.49, 0.21) | 0.003 |

| SF-36 MCS (every 10 points) | 0.91 (0.27, 1.55) | 0.007 |

| Marital status (single/cohabitating) | 2.21 (−0.16, 4.58) | 0.08 |

| Stool incontinence | 1.48 (0.06, 2.82) | 0.4 |

| Age (every 10 years) | −1.16 (−1.86, −0.47) | 0.002 |

| Year 1 | 1.36 (0.36, 2.33) | 0.009 |

| Year 2 | 0.76(−0.31, 1.80) | 0.17 |

For continuous variables, the estimate represents the change in IIEF score for each variable unit. For categorical variables, the estimate represents the estimated least-square means between groups.

On multivariable analysis, men who were married had significantly lower global sexual function compared with men who were single or cohabitating with a partner, corresponding to a mean IIEF score difference of 15 points (results not shown). There was no association between marital status and erectile function (Table 3).

Fifteen men with UC (54%) and 15 (37%) men with CD were current or former smokers at baseline. Overall, current or former smokers had an IIEF score 12 points higher than nonsmokers. This effect was most pronounced in UC, which was associated with an average increase in IIEF score by 19 points (results not shown).

Sexual Function and Quality of Life

There were significant associations between performance on multiple IIEF domains and disease-specific and generic quality of life instruments. Overall, IBDQ score significantly increased between baseline and the first year (Fig. 1). Among all men, univariate analysis showed that lower IBDQ scores were associated with lower scores in the IIEF domains of erectile function, sexual desire, and overall satisfaction (Table 2). On multivariable analysis after adjustment for marital status, IBD subtype, PHQ-8 score, and FACIT score, IBDQ score was not an independent predictor of sexual function (data not shown).

Over time, the SF-36 PCS score increased, with significantly higher scores at year 2 compared with baseline (P = 0.032) among all patients (Fig. 1). The SF-36 MCS score also increased, but only during year 1 (P = 0.038), with a drop back to baseline at year 2 (Fig. 1). The SF-36 PCS—but not the MCS—was significantly associated with IIEF scores in univariate analysis without adjustment for multiple hypotheses (Table 2). On domain analysis, erectile function was significantly associated with all quality of life measures (ie, IBDQ, SF-36 MCS, SF-36 PCS). On multivariable analysis, SF-36 MCS and SF-36 PCS were both independently associated with erectile function (Table 3).

Sexual Function and Depression, Fatigue

Depression, defined as a PHQ-8 score of 10 or greater, was found in 6 (9.8%) of the 61 participants with available baseline PHQ-8 score data. Over time, PHQ-8 scores initially decreased at year 1 but then returned to baseline (P = 0.062) (Fig. 1). Among all men, lower scores on PHQ-8 were associated with lower IIEF scores (P = 0.03), but this was not sustained after adjustment for false discovery rate (P = 0.32, Table 2). The domains of intercourse satisfaction and overall satisfaction were statistically associated with PHQ-8 scores, without adjustment for multiple hypotheses (Table 2).

Using a FACIT-F scale cutoff score less than or equal to 30, 16 (23.2%) men had fatigue (12 [29.3%] CD and 4 [14.3%] UC) at baseline. Univariate analysis did not reveal a significant association between fatigue and sexual function among all men with IBD (P = 0.10) and UC (P = 0.9), but there was a significant association among men with CD (P = 0.049), specifically in the IIEF domains of erectile function (P = 0.046) and overall satisfaction (P = 0.028) (results not shown). Binary analysis showed no significant difference between patients with and without fatigue (P = 0.48 all men; P = 0.10 CD; P = 0.31 UC).

DISCUSSION

In this IBD inception cohort, we found that 94% of men have erectile dysfunction early in the course of their disease. This prevalence of male sexual dysfunction is substantially higher than the 31% reported by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the US general population.25 It is also much higher than the prevalence of sexual dysfunction reported globally.26, 27 Compared with other chronic diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease requiring renal replacement, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, our study found a higher prevalence of erectile dysfunction among men with IBD.28–31

Over the course of the 2-year study period, there was no significant change in mean IIEF score, despite improvement in disease activity and quality of life scores (Fig. 1). Medical treatment of sexual dysfunction in other chronic conditions has been shown to increase IIEF scores in as quickly as 12 weeks in other chronic conditions, including diabetes, spinal cord injury, ischemic heart disease, and depression.32–36 Our finding, therefore, is unlikely to be due to lack of responsiveness of IIEF. Instead, persistent sexual dysfunction in men with newly diagnosed IBD may be due to a lack of clinicians’ recognition and treatment of sexual dysfunction in this population.

On multivariable analysis, older age was independently associated with global sexual functioning and erectile dysfunction. The association between erectile function and age has been reported in the general population.37 However, in our study, 95% of men age 40 years and over had erectile dysfunction, compared with 10% men in the general population.38

Erectile function is independently associated with SF-36 MCS (Table 3). In our study, lower PHQ-8 scores were associated with lower IIEF scores; however, this association was not sustained on multivariable analysis. A lack of sustained association may be a result of missing data for PHQ-8 scores; scores were available for 61, 59, and 44 men at baseline, year 1, and year 2, respectively. In comparison, 2 previous cross-sectional reports from Europe have suggested that depression may play an important role in sexual functioning among men with IBD. A study from Spain that was compromised by a low (27%) response rate showed that treatment for depression may be an independent risk factor for sexual dysfunction.7 The same study suggested that, unlike women, men tended to blame psychological disease–related effects for worsening of intimacy.7 In 2007, Timmer et al reported a similar finding, with depressed mood (measured by the Hospital Depression Scale) found to be the most important determinant of a low score in all sexual function domains on the IIEF.34 In both studies, most patients had IBD for more than 10 years, and response rates were low (27% in Marin study, 41% in Timmer study). Two more recent studies also showed an association between depression and impaired sexual function in men with IBD, especially in the setting of active disease.40, 41 A study from a large internet-based cohort of IBD patients also found an association between an increasing level of depression and sexual interest and satisfaction.42 In that study, the mean time of disease duration was 13 years.42

In a recent, cross-sectional, observational cohort study, O’Toole et al developed a new tool to assess male sexual function in IBD.41 This new tool correlated with all subscales of the IIEF.41 Additionally, this study found that ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, high PHQ-8 scores, IBD activity, and previous smoking status all significantly associated with sexual dysfunction. However, comparisons to our findings must be done with caution, due to differences in study populations.41 Participants in the O’Toole study derived from 2 large medical centers in Boston, had an average of 14 years of disease duration, and had higher baseline disease severity with greater exposure to biologic therapy and IBD-related surgeries.41

In our study, increased disease activity was associated with lower sexual function in UC but not in CD (SCCAI in UC, unadjusted P = 0.003; HBI in CD, unadjusted P = 0.07). This may be due to statistical under-powering or imperfect measurements of disease activity. The lack of association between disease activity and sexual function may also be related to the overall mild disease in this inception cohort of men with newly diagnosed IBD. However, SF-36 PCS was independently associated with erectile function (Table 3)). Timmer et al reported 2 cross-sectional studies that utilized IIEF in men with IBD.6, 39 One study found no significant association between disease activity and IIEF scores,6 and the other reported inconclusive results.39 Interestingly, the same researchers found that sexual attractiveness and sexual interest (as measured by a cancer-specific sexual function questionnaire) in 91 men with IBD were higher in remission than in active disease.39 This is also similar to our own previously reported finding of a significant association between disease activity and body image dissatisfaction.43

Interestingly, we found former and current smoking to be independently associated with sexual functioning among men with UC but not CD (results not shown). This finding may be a result of a milder disease course experienced by smokers with UC. This is supported by a lower mean SCCAI score among current smokers compared with never smokers (mean SCCAI score among current smokers 1.8 vs mean SCCAI score among never smokers 3.0).

This study has several limitations. First, about one third of men in this cohort did not have sufficient data for analysis. We compared IIEF questionnaire completers and noncompleters and found no difference in demographics or disease activity scores. Still, our study may be susceptible to response bias. Second, we did not have a healthy control group to determine the impact of IBD on sexual function. Nevertheless, the instrument we used in this study has been well-validated in both healthy and diseased populations, with well-established cutoff values to distinguish between healthy and disordered sexual function in men. Third, a small number of men had perianal disease and surgeries, limiting our ability to explore the associations between these factors and sexual function. Fourth, accurate assessment of sexual functioning in men may be limited by discomfort in reporting such a private aspect of one’s personal life, even using self-administered questionnaires. Indeed, only 18% of sexually active men in the general population reported seeking medical help from doctors for sexual problems.4 Fifth, most of our patients were from Rhode Island, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other regions. However, because our study cohort consists of men in a community population rather than from tertiary care centers, it is likely to be more representative of the general population of patients with IBD.

Despite these limitations, our study possesses unique strengths. The greatest strength is the study’s prospective, longitudinal design. Moreover, this study involves men with newly diagnosed with IBD—a population that has not been previously examined with respect to sexual function. Also, the study has a high response rate (84%), compared with other studies. Another strength is the stability of the patient population in OSCCAR, which had an 11% drop-out rate during the study period. Additionally, our study utilized a larger variety of clinical- and disease-specific outcome measures than other male sexual function studies in IBD. Importantly, we utilized the IIEF, which is the most accepted tool for the evaluation of male sexual function.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in a community-based incident cohort of IBD men, we found that most men with recently diagnosed IBD have erectile dysfunction. Our findings also support an association between erectile dysfunction, older age, and quality of life measurements, which may have a potential role in the detection of ED in men with IBD. Clinicians should be aware of the high prevalence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in men with IBD. We recommend screening for sexual dysfunction in male patients with IBD and considering referral for treatment using pharmacotherapy and behavioral techniques, when appropriate. Furthermore, phosphodiesterase type 5-inhibitors, which have shown to improve sexual function in men with other chronic disease but have not been studied in IBD outside of surgery, deserve further investigation.32–35, 44 Future practice guidelines that provide screening and treatment guidelines for sexual dysfunction in men with IBD will improve the care provided to this population.

Supported by:

This work was supported by grants from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (5U01DP000340 and 3U01DP002676) and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shapiro JM, Zoega H, Shah SA, et al. Incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Rhode Island: report from the Ocean State Crohn’s and Colitis area registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1456–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basson R, Rees P, Wang R, et al. Sexual function in chronic illness. J Sex Med. 2010;7:374–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al. ; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moody GA, Mayberry JF. Perceived sexual dysfunction amongst patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 1993;54:256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmer A, Bauer A, Kemptner D, et al. Determinants of male sexual function in inflammatory bowel disease: a survey-based cross-sectional analysis in 280 men. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1236–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marín L, Mañosa M, Garcia-Planella E, et al. Sexual function and patients’ perceptions in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control survey. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valer P, Algaba A, Santos D, et al. Evaluation of the quality of semen and sexual function in men with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1144–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the international index of erectile function. Urology. 1999;54:346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinsley A, Macklin EA, Korzenik JR, et al. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue (FACIT-F) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1328–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D, Lai JS, Chang CH, et al. Fatigue in cancer patients compared with fatigue in the general united states population. Cancer. 2002;94:528–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, et al. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy fatigue scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:811–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai JS, Beaumont JL, Ogale S, et al. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale in patients with moderately to severely active systemic lupus erythematosus, participating in a clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Luo MP, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the short form 36 health survey and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue subscale for patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Signorovitch J, Brainsky A, Grotzinger KM. Validation of the FACIT-fatigue subscale, selected items from FACT-thrombocytopenia, and the SF-36v2 in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irvine EJ, Feagan B, Rochon J, et al. Quality of life: a valid and reliable measure of therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Canadian Crohn’s relapse prevention trial study group. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JF, et al. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariable imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Soft. 2011;45:1–67. https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v045i03 [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Buuren S Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2012. https://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1780871 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loprinzi PD, Nooe A. Erectile dysfunction and mortality in a national prospective cohort study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:2130–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. ; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jannini EA, Sternbach N, Limoncin E, et al. Health-related characteristics and unmet needs of men with erectile dysfunction: a survey in five European countries. J Sex Med. 2014;11:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dias M, Oliveira MJ, Oliveira P, et al. Does any association exist between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and erectile dysfunction? The DECODED study. Rev Port Pneumol (2006). 2017;23:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diemont WL, Vruggink PA, Meuleman EJ, et al. Sexual dysfunction after renal replacement therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tristano AG. The impact of rheumatic diseases on sexual function. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong P, Pope JE, Ouimet JM, et al. Erectile dysfunction associated with scleroderma: a case-control study of men with scleroderma and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:508–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rendell MS, Rajfer J, Wicker PA, et al. Sildenafil for treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Sildenafil diabetes study group. Jama. 1999;281:421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giuliano F, Hultling C, El Masry WS, et al. Randomized trial of sildenafil for the treatment of erectile dysfunction in spinal cord injury. Sildenafil study group. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conti CR, Pepine CJ, Sweeney M. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in patients with ischemic heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:29C–34C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsson AM, Persson CA; Swedish Sildenafil Investigators Group. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate for the treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with cardiovascular disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidman SN, Roose SP, Menza MA, et al. Treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with depressive symptoms: results of a placebo-controlled trial with sildenafil citrate. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1623–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helgason AR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, et al. Sexual desire, erection, orgasm and ejaculatory functions and their importance to elderly Swedish men: a population-based study. Age Ageing. 1996;25:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Leary MP, Rhodes T, Girman CJ, et al. Distribution of the brief male sexual inventory in community men. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timmer A, Bauer A, Dignass A, et al. Sexual function in persons with inflammatory bowel disease: a survey with matched controls. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bel LG, Vollebregt AM, Van der Meulen-de Jong AE, et al. Sexual dysfunctions in men and women with inflammatory bowel disease: the influence of IBD-related clinical factors and depression on sexual function. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1557–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Toole A, de Silva PS, Marc LG, et al. Sexual dysfunction in men with inflammatory bowel disease: a new IBD-specific scale. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eluri S, Cross RK, Martin C, et al. Inflammatory bowel diseases can adversely impact domains of sexual function such as satisfaction with sex life. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:1572–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saha S, Zhao YQ, Shah SA, et al. Body image dissatisfaction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindsey I, George B, Kettlewell M, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sildenafil (viagra) for erectile dysfunction after rectal excision for cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:727–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]