Abstract

Background

To determine outcomes of children with rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) with isolated lung metastases.

Methods

Data was analyzed for 428 patients with metastatic RMS treated on COG protocols. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated using Kaplan Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.

Results

Compared to patients with other metastatic sites (n = 373), patients with lung-only metastases (n = 55) were more likely to be < 10 years of age, have embryonal histology (ERMS), have N0 disease, and less likely to have primary extremity tumors. Lung-only patients had significantly better survival outcomes than patients with all other sites of metastatic disease (P < 0.0001) with 5-yr EFS of 48.1% vs. 18.8% and 5-yr OS of 64.1% vs. 26.9%. Patients with lung-only metastases, and those with a single extrapulmonary site of metastasis, had better survival compared to patients with 2 or more sites of metastatic disease (P < 0.0001). In patients with ERMS and lung-only metastases, there was no significant difference in survival between patients ≥10 years and 1–9 years (5-yr EFS: 58.3% vs. 68.2%, 5-yr OS: 66.7% vs. 67.7%).

Conclusions

With aggressive treatment, patients with ERMS and lung-only metastatic disease have superior EFS and OS compared to patients with other sites of metastatic disease, even when older than 10 years of age. Consideration should be given to including patients ≥10 years with ERMS and lung-only metastases in the same group as those <10 years in future risk stratification algorithms.

Keywords: Rhabdomyosarcoma, Lung Metastases, Children’s Oncology Group

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of childhood.1 It can present at different ages, in a variety of primary locations, and with different driver mutations, histologies, and patterns of metastatic spread.2 This variable presentation leads to complex risk stratification and treatment algorithms based on clinicopathologic features, with diverse outcomes across risk groups. Intermediate-risk (IR) RMS is comprised of a highly heterogenous group of patients with 5-yr EFS rates of 50–75% with the selective combination of multi-agent chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy,3–5 while patients with high-risk (HR) RMS have 3-yr EFS rates of approximately 16–30%.6–11 Metastatic disease is present in 16% of all cases of RMS and generally portends a poor prognosis.10,12,13 While most patients with metastatic disease are classified as high-risk, results from HR-RMS COG trials, D9803, ARST0431 and ARST08P1, demonstrated that patients younger than 10 years of age with stage IV embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS) had superior outcomes, with 3-year EFS of 60–64%.10–14 Patients with stage IV alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) were found to have the worst survival outcomes with 3-year EFS of 6–16%.10,11 These findings are reflected in the most recent COG risk classification and the eligibility for the current IR-RMS clinical trial (ARST1431) in which patients younger than 10 years of age with stage IV ERMS are classified as intermediate risk.6

Lung metastases are the most common site of metastatic disease, present at diagnosis in 5.7% of all new RMS.9,12,13 While studies have found the presence of lung metastases considerably increases the likelihood of developing metastases in other sites, there are a subset of patients presenting with isolated lung metastases.9,12,15–18 Studies of metastatic RMS frequently do not subdivide outcomes by metastatic site involvement. However, there is literature suggesting that not all metastatic presentations have uniformly poor outcomes.9,10,12,15–19 A limited number of studies have examined survival outcomes in patients with RMS stratified by pulmonary involvement with mixed results showing either improved or equivalent survival in patients with isolated lung metastases compared to patients with other sites of metastatic disease.9,15,16,18–20 It therefore remains an open question of whether patients with lung-only metastases represent a specific subpopulation that may be amenable to treatment approaches that vary from other high-risk groups.

The aim of this study is to determine the clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of children with metastatic RMS limited to the lung. Here, we describe the outcomes of children with metastatic RMS who were treated on COG trials from the year 1999 to 2013, and compare outcomes in those patients with lung-only metastatic disease to that of patients with metastases at other sites.

Materials and Methods

Patient population

Patients with newly diagnosed, metastatic RMS enrolled on previously reported COG studies from 1999–2013 (D9802, D9803, ARTS0431, ARST08P1) were included in this analysis 4,10,11,14,21. The risk group classifications and treatment schema are shown in Supplemental Table S1. These trials were approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution or by the Pediatric Central Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute. Informed consent and assent from the patient and/or parent/guardian, as appropriate, was obtained before enrollment.

Statistical methods

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics, treatment characteristics and outcomes of the patients were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the characteristics and outcome distribution of patients with metastatic disease to lung-only vs other sites. Median follow up time, along with interquartile range for patients alive at the time of this analysis, were also summarized.

The 5-year event free survival (EFS) probabilities and 5-year overall survival (OS) probabilities with 95% confidence intervals were estimated using Kaplan Meier (KM) method. EFS was defined as the time from study enrollment to time of disease relapse or progression, second malignancy, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. OS was defined as the time from enrollment to death from any cause. EFS and OS curves were compared between the groups using the log-rank test. All data analyses were performed using SAS statistical package (SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

In total, 428 eligible patients with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma were identified. The characteristics of patients with lung-only metastases (n = 55, 12.9%) and other sites of metastatic involvement, with or without lung (n = 373, 87.1%) are shown in Table 1 and Supplemental Table S2. Clinical features differed significantly (P<0.001) between patients with lung-only metastases and patients with other sites of metastatic involvement with respect to age, histology, primary site of disease, tumor invasiveness, and nodal involvement. Compared to patients with other metastatic sites of disease, patients with lung-only metastatic disease tended to be younger with 58.2% vs. 30.8% being between 1 and 9 years of age and 32.7% vs. 67.3% being 10 years of age or older. Patients with metastatic disease isolated to the lung were more likely to have embryonal histology (74.6% vs. 25.7%) and less likely to have alveolar histology (12.7% vs 66.2%) compared to patients with other metastatic sites of disease. Patients with lung-only metastatic disease were more likely to have primary tumors at parameningeal sites (23.6% vs 9.4%) and less likely to have the primary tumors in the extremities (7.3% vs. 27.1%) than patients with other metastatic sites of disease. Patients with metastatic disease limited to the lung were also more likely to have T1 tumors (21.8% vs. 7.51%) and less likely to have regional nodal involvement by both clinical (21.8% vs. 62.5%) and pathological (3.6% vs. 18.2%) staging.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with rhabdomyosarcoma metastatic to lung only and to other sites

| Lung only | Other sites -/+ lung | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Number | (%) | Number | (%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Total Number Patients | 55 | 373 | |||

| Age at diagnosis, years | <.0001 | ||||

| < 1 | 5 | 9.1 | 7 | 1.9 | |

| 1 – 9 | 32 | 58.2 | 115 | 30.8 | |

| ≥10 | 18 | 32.7 | 251 | 67.3 | |

| Histology Subtype | <0.0001 | ||||

| Alveolar | 7 | 12.7 | 247 | 66.2 | |

| Embryonal | 41 | 74.6 | 96 | 25.7 | |

| Botryoid | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Spindle cell | 3 | 5.5 | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Other | 3 | 5.5 | 27 | 7.2 | |

| Primary Site | <0.0001 | ||||

| Extremity | 4 | 7.3 | 101 | 27.1 | |

| GU Bladder/Prostate | 9 | 16.4 | 30 | 8.0 | |

| GU non-Bladder/Prostate# | 5 | 9.1 | 35 | 9.4 | |

| Head and Neck, nonparameningeal# | 4 | 7.3 | 13 | 3.5 | |

| Orbit# | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Parameningeal | 13 | 23.6 | 35 | 9.4 | |

| Perineum | 1 | 1.8 | 24 | 6.4 | |

| Retroperitoneal | 9 | 16.4 | 60 | 16.1 | |

| Trunk/paravertebral | 3 | 5.5 | 36 | 9.7 | |

| Intrathoracic | 0 | 0 | 13 | 3.5 | |

| Other | 7 | 12.7 | 18 | 4.8 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1.9 | |

| Tumor Invasiveness | 0.0014 | ||||

| T1 | 12 | 21.8 | 28 | 7.5 | |

| T2 | 43 | 78.2 | 344 | 92.2 | |

| Tx | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Regional Lymph Node | |||||

| Clinical | <0.0001 | ||||

| N0 | 43 | 78.2 | 121 | 32.4 | |

| N1 | 12 | 21.8 | 233 | 62.5 | |

| Nx | 0 | 0 | 19 | 5.1 | |

| Pathological | 0.0231 | ||||

| N0 | 13 | 23.6 | 70 | 18.8 | |

| N1 | 2 | 3.6 | 68 | 18.2 | |

| Nx | 40 | 72.7 | 235 | 63.0 | |

Favorable sites

P-value was obtained using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test

Treatment and outcome of patients with metastatic disease

Patients with lung-only metastatic disease were less likely to suffer relapse and/or progression compared to patients with other sites of metastatic disease (43.6% vs. 74%, p<0.0001) (Supplemental Table S2). Data on specific sites of relapse and/or progression was not available. However, no significant difference was found in the distribution of relapse/progression sites (local/regional, metastatic, and concurrent local/regional and metastatic sites) between patients with lung-only metastatic disease and patients with other metastatic sites (Supplemental Table S2).

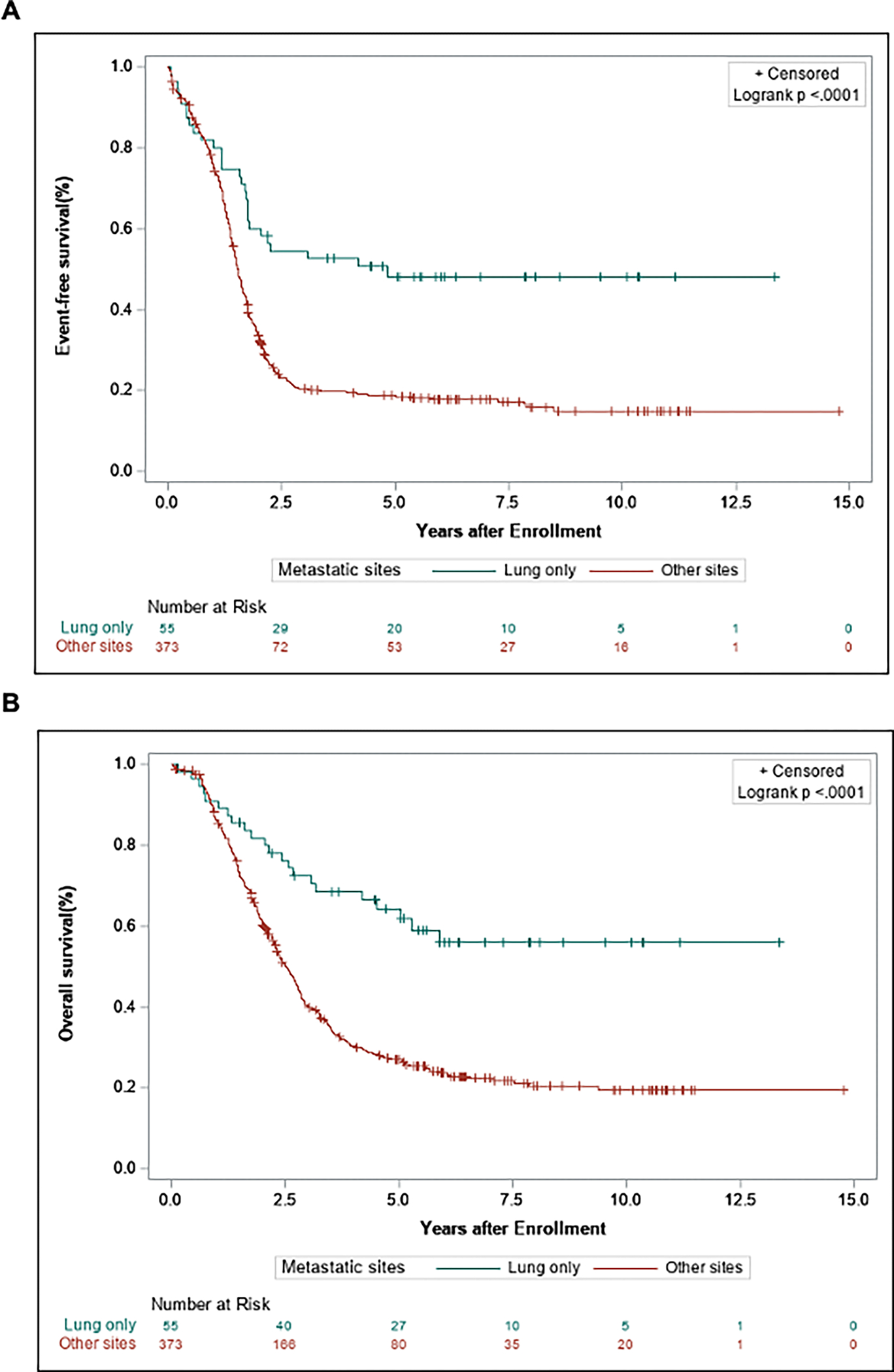

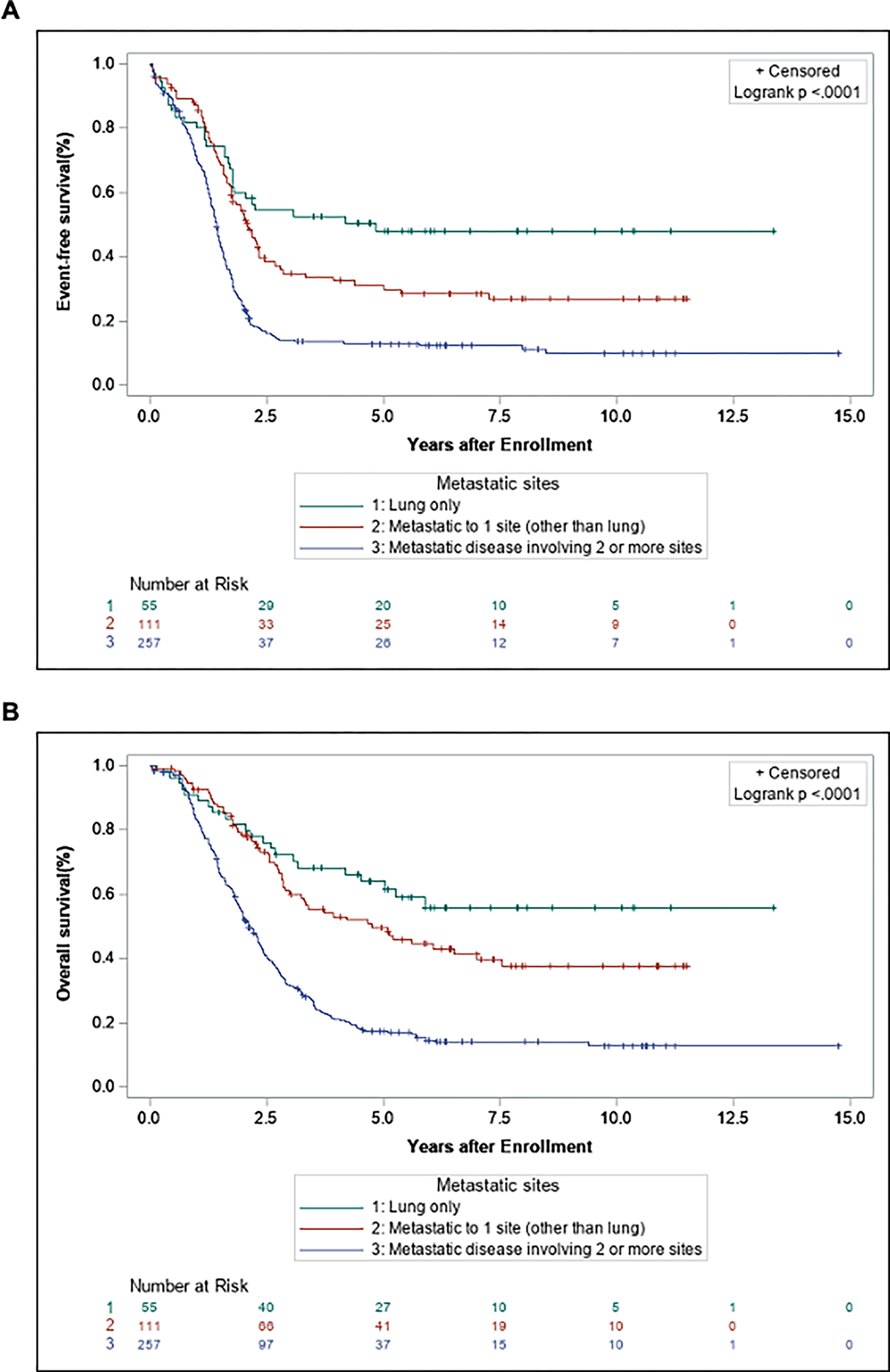

Five-year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were compared between patients with lung-only metastatic disease and patients with metastatic disease at other sites, with or without lung involvement. Overall, patients with metastatic disease isolated to the lung had an improved 5-yr EFS (48.1% vs. 18.8%) and 5-yr OS (64.1% vs. 26.9%, P < 0.0001) compared to patients with metastatic disease to other sites (Fig. 1). Patients with metastatic disease were then further divided into 3 groups: those with isolated lung metastases, patients with a single site of metastasis excluding the lung, and patients with 2 or more sites of metastases with or without lung involvement. Patients with isolated lung metastases, and patients with non-lung single site of metastasis, both demonstrated superior survival compared to patients with 2 or more sites of metastatic disease (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table S3). In a pairwise comparison, there was a trend towards improved EFS and OS in patients with lung-only metastases compared to those with non-lung single site of metastasis, but this did not reach statistical significance (EFS: 48.1% vs. 31.2%, P = 0.06; OS: 64.1% vs. 49.6%, P = 0.1266) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Event-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) and comparing patients with RMS metastatic disease in lung-only vs. all other metastatic sites −/+ lungs.

Figure 2.

Event-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) comparing patients with RMS metastatic disease divided into 3 groups: lung-only, metastatic disease limited to 1 site (other than lung), and metastatic disease involving 2 or more sites (with or without lung).

Next, a univariate analysis was performed to identify additional prognostic factors. Consistent with previous COG studies, age, histology, and primary tumor site were associated with worse EFS and OS in patients with metastatic disease to other sites with or without lung involvement (Supplemental Table S3). Patients between 1 and 9 years of age with metastatic disease to other sites showed an improved EFS and OS compared with those aged ≥10 years (EFS: 32.5% vs. 11.7%; OS: 43.1% vs. 18.2%). In patients with other sites of metastatic disease, alveolar histology was associated with significantly worse EFS and OS compared to patients with non-alveolar histology (EFS: 7.2% vs. 41.8%; OS: 47.9% vs. 16.6%). In patients with metastatic disease to other sites, those with primary tumors located at favorable sites had improved EFS and OS compared with those who had tumors at unfavorable sites (EFS rate, 38.4% vs. 10.4%; OS rate, 43.3% vs. 20.3%).

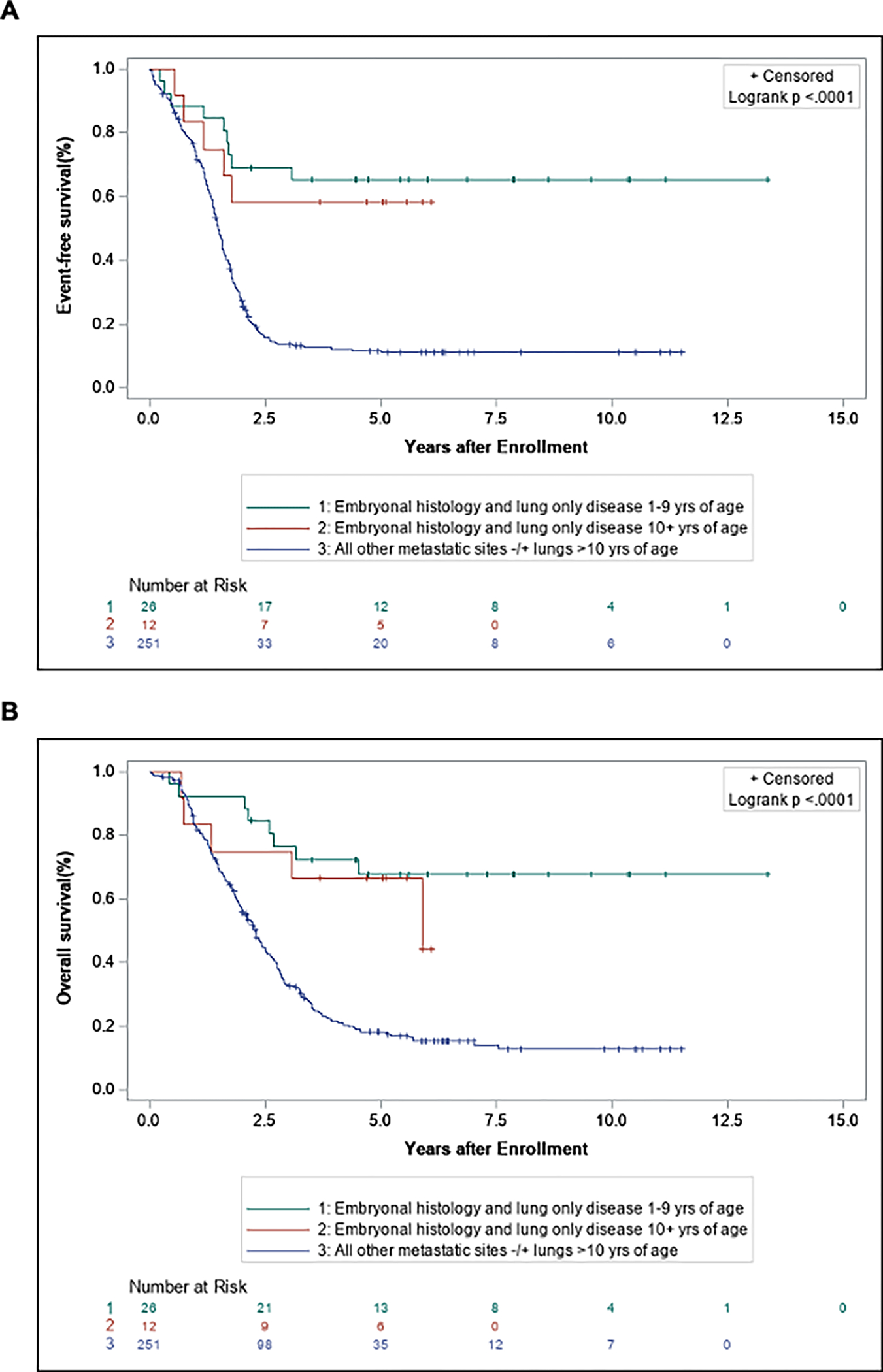

In contrast to patients with metastatic disease at other sites, no clinical or pathologic features were significantly associated with EFS or OS in patients with lung-only metastatic disease (Supplemental Table S3). Notably, patients with lung-only metastatic disease > 10 years of age had similar 5-year EFS and OS to that of patients between 1 and 9 years of age (EFS: 50% vs. 54.7%; OS: 65.8% vs. 64.2%). This was in sharp contrast to patients with other sites of metastatic involvement in which those ≥ 10 years of age had significantly worse 5-year EFS and OS compared to patients between 1 and 9 years of age (EFS: 50.0% vs. 11.7%, OS: 65.8% vs. 18.2%). When comparing outcomes by a function of age and histology (Fig. 3), patients ≥ 10 years of age with lung-only metastatic disease had a similar 5-year EFS and OS as those patients between 1 and 9 years of age, and both groups showed a superior survival compared to patients ≥ 10 years of age with other sites of metastatic disease (EFS: 58.3% vs. 66.2% vs. 11.7%, p<0.0001; OS: 66.7% vs. 67.7% vs. 18.2%, p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Event-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) comparing patients with embryonal histology and lung-only disease 10+ years of age, embryonal histology, and lung-only disease 1–9 years of age, all histology and other metastatic sites −/+ lungs >10 years of age.

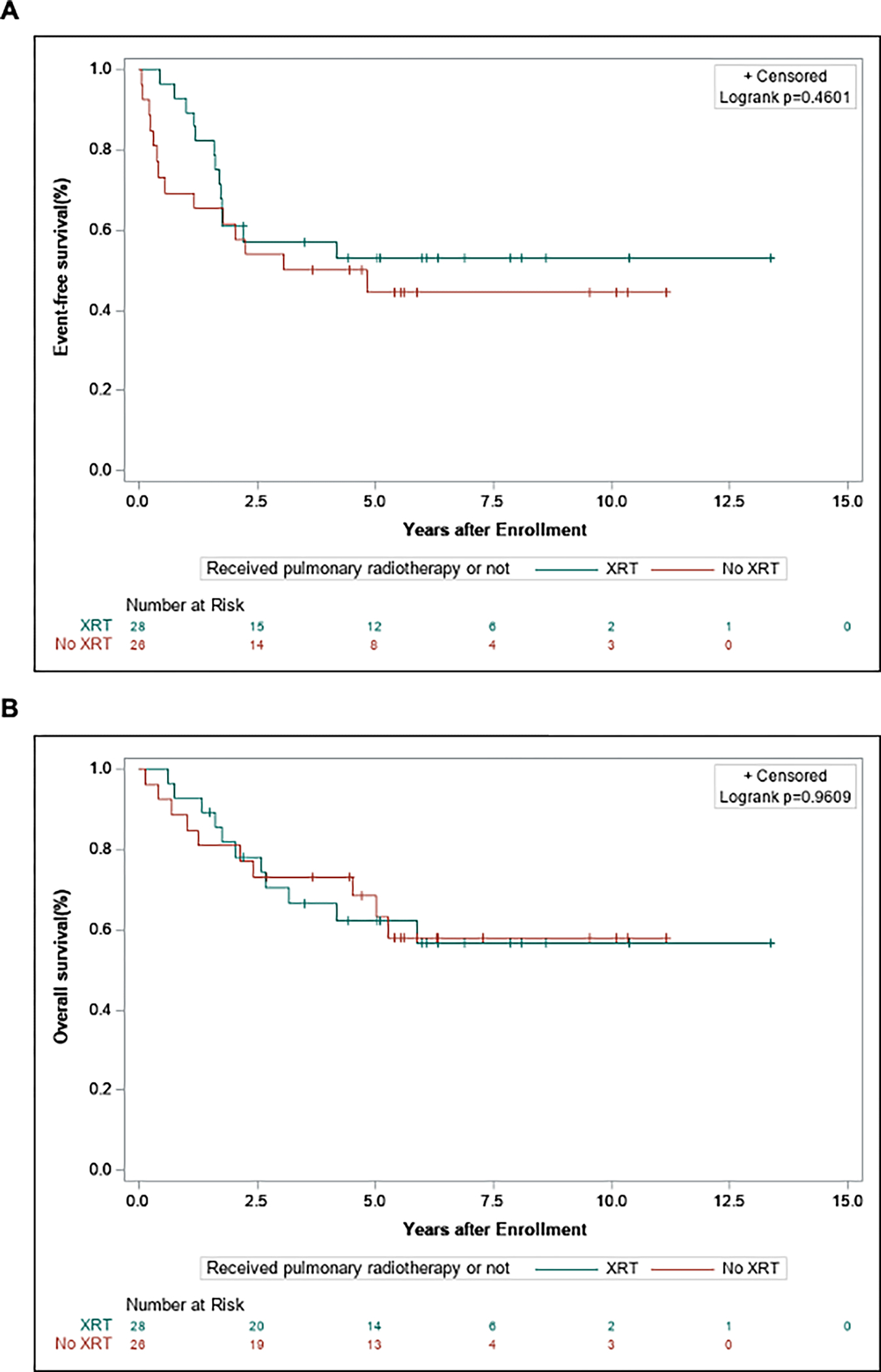

In patients with isolated lung metastases, 51.8% (n = 28) received radiotherapy to the lungs (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in survival outcomes between patients who received lung radiotherapy compared to those who did not receive radiotherapy (Fig. 4; EFS: 52.9% vs. 44.4%, P = 0.46; OS: 62.3% vs. 68.5%, P = 0.96). There was also no significant difference in the rate of relapse occurring in the lung compared to other metastatic sites (Table. 2).

TABLE 2.

Outcomes and disease recurrence in patients with lung only metastatic disease treated with pulmonary radiotherapy

| XRT | No XRT | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Number | (%) | Number | (%) | ||

| Total Numbera Patients | 28 | 51.9 | 26 | 48.2 | |

| Recurrence | 0.1071 | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 39.1 | 14 | 60.9 | |

| No | 19 | 61.3 | 12 | 38.7 | |

| Site of relapse/progression | 1.0000 | ||||

| Lung | 4 | 36.4 | 7 | 63.6 | |

| Other | 5 | 41.7 | 7 | 58.3 | |

P-value was obtained using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

Data regarding XRT not available for 1 patient with isolated lung metastases

Figure 4.

Event-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) comparing patients with RMS metastatic disease limited to the lung who received pulmonary radiotherapy vs. those who did not.

Discussion

Metastatic disease is an important prognostic marker in RMS and generally portends poor survival outcomes.10,12,13,22 The lung is the most common site of metastatic disease, present in 47% of patients with stage IV RMS.12 In roughly 18% of patients, lung is the only site of metastatic disease.12 In this analysis, patients with lung-only metastases were more likely to have favorable clinical features, including age of presentation between 1 and 9 years, embryonal histology, lower rates of regional lymph node involvement and fewer primary extremity tumors. We also found that patients with lung-only metastases had improved 5-year EFS and OS compared to patients with other metastatic sites. Consistent with previous reports12, we found that the number of metastatic sites was negatively associated with survival outcomes. Patients with lung-only metastatic disease demonstrated slightly better survival compared to patients with a single extrapulmonary site of metastasis, and both groups had significantly better survival compared to patients with 2 or more metastatic sites of disease, with or without lung involvement. Our results are in line with previous findings by Rodeberg et al. (2005), in which patients with lung-only metastatic RMS treated on Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies IV (IRS-IV) demonstrated more favorable clinical characteristics.15 In that study, there was also a trend towards improved 4-year OS in patients with isolated lung metastatic disease compared to other metastatic sites (37% vs. 24%, P = 0.092) and significantly worse survival in patients with 2 or more metastatic sites, but no statistically significant difference in survival outcomes between patients with lung-only metastases and a single extrapulmonary site. In a retrospective review of patients with RMS treated at a single institution, Williams et al. (2004) found that patients with metastases confined to the lung had 3-year OS and EFS rates of 75% and 63%, respectively, compared to 35% and 29% in all patients with metastatic disease18. A report from the European CWS study group analyzing outcomes in children with ERMS found that patients with isolated lung metastatic disease had a 5-year OS and EFS of 48.7% and 37.9%, respectively20.

While a majority of patients with metastatic disease are classified as high-risk, results from the two most recent HR-RMS COG trials, ARST0431 and ARST08P1, confirmed findings from D9803 demonstrating that patients 1 to 9 years of age with stage IV ERMS had a 3-year EFS of 60–64%, significantly better than the 3-year EFS of 6–16% noted in patients with stage IV ARMS10,11,14. Based on these findings, the classification of IR-RMS has been modified to include patients younger than 10 years of age with stage IV ERMS.6 In this study, we found that patients ≥ 10 years of age with ERMS and isolated lung metastases had similar survival outcomes compared to patients 1–9 years of age when treated with intensive regimens, including VAC with a cyclophosphamide dose of 2.2g/m2/course, or with intensive multi-modal therapy such as VAc (cyclophosphamide dose of 1.2g/m2/course) combined with interval compression of VDc and IE.

Rodeberg et al. (2005) reported a modest 4-year EFS and OS benefit with radiotherapy in patients with lung-only metastatic RMS treated on IRS-IV (EFS: 48 vs. 12%, P = 0.011; OS: 47% vs. 31%, P = 0.039).15 We found that roughly 50% of patients with isolated pulmonary metastatic disease received lung radiotherapy, but no survival benefit was associated with the use of radiotherapy in this study. These findings are in line with reports from the CWS study group showing that local treatment of pulmonary metastatic disease did not improve survival outcomes in patients with metastatic ERMS.20 However, the potential benefit of radiotherapy in treating patients with RMS and isolated pulmonary metastatic disease has not been formally assessed in a randomized fashion and future prospective studies in larger cohorts are needed. In addition to being retrospective in nature, our study is limited by heterogeneity in the timing of radiotherapy amongst the different COG protocols included in this analysis. Moreover, there was no available data concerning the number, size and pathologic confirmation of pulmonary lesions or whether a pulmonary metastasectomy was performed. There were only 7 patients with alveolar histology and lung-only metastases in this cohort, making it difficult to evaluate the clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes in this subgroup. This study was also limited by the lack of FOXO1-fusion status in the cohort of patients with isolated lung metastases, likely reflecting the fact that the vast majority (74.6%) of these patients had embryonal histology and did not undergo fusion testing. Additional studies will be needed to determine if FOXO1-fusion status provides additional prognostic information in patients with lung-only metastatic disease, particularly in patients with alveolar histology.

In this study, lung-only metastatic disease was associated with favorable clinicopathologic features, including a predominance of embryonal histology, likely driving improved survival outcomes in this population. Patients with ERMS and lung-only metastases had superior 5-year EFS and OS rates compared to patients with other sites of metastatic disease, even when ≥ 10 years of age. In COG ARST0431, an expanded group of patients with Oberlin risk scores of 0 to 1 had a 3-year EFS rate of 67% when treated with a dose-intensive multiagent regimen, an improvement over historical controls10. This group with lower risk metastatic disease included patients with ERMS ≥ 10 years of age and an Oberlin score <2. Our data suggest that patients ≥ 10 years of age with ERMS and lung-only metastases may be representative of this lower risk group identified on ARST0431. Currently, all patients with metastatic ERMS ≥ 10 years of age are classified as high risk by COG criteria, but these findings indicate that consideration be given to including patients with metastatic disease confined to the lung in the same group as those <10 years in future risk stratification algorithms.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure S1. Direct pairwise comparison of event-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) between patients with RMS metastatic disease limited to the lung and metastatic disease limited to a single extrapulmonary site. Direct pairwise comparison of event-free survival (C) and overall survival (D) between patients with RMS metastatic disease limited to the lung and metastatic disease to multiple sites (2 or more sites with or without lung).

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health to the Children’s Oncology Group (U10CA180886 and U10CA180899) and grants from St. Baldrick’s foundation. JCV is funded in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program and the Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists at Yale, sponsored by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation award #2015216, and the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- RMS

Rhabdomyosarcoma

- ERMS

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma

- ARMS

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

- OS

Overall survival

- EFS

Event-free survival

- HR

High risk

- IR

Intermediate risk

- IRS

Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2018, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/, based on November 2020 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2021. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shern JF, Yohe ME, Khan J. Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma. Crit Rev Oncog. 2015;20(3–4):227–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins DS, Chi YY, Anderson JR, et al. Addition of Vincristine and Irinotecan to Vincristine, Dactinomycin, and Cyclophosphamide Does Not Improve Outcome for Intermediate-Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(27):2770–2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arndt CA, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: children’s oncology group study D9803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5182–5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casey DL, Chi YY, Donaldson SS, et al. Increased local failure for patients with intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma on ARST0531: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2019;125(18):3242–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haduong JH, Heske CM, Allen-Rhoades W, et al. An update on rhabdomyosarcoma risk stratification and the rationale for current and future Children’s Oncology Group clinical trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(4):e29511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raney RB, Walterhouse DO, Meza JL, et al. Results of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group D9602 protocol, using vincristine and dactinomycin with or without cyclophosphamide and radiation therapy, for newly diagnosed patients with low-risk embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1312–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walterhouse DO, Pappo AS, Meza JL, et al. Shorter-duration therapy using vincristine, dactinomycin, and lower-dose cyclophosphamide with or without radiotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed low-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3547–3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breneman JC, Lyden E, Pappo AS, et al. Prognostic factors and clinical outcomes in children and adolescents with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma--a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weigel BJ, Lyden E, Anderson JR, et al. Intensive Multiagent Therapy, Including Dose-Compressed Cycles of Ifosfamide/Etoposide and Vincristine/Doxorubicin/Cyclophosphamide, Irinotecan, and Radiation, in Patients With High-Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(2):117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malempati S, Weigel BJ, Chi YY, et al. The addition of cixutumumab or temozolomide to intensive multiagent chemotherapy is feasible but does not improve outcome for patients with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2019;125(2):290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oberlin O, Rey A, Lyden E, et al. Prognostic factors in metastatic rhabdomyosarcomas: results of a pooled analysis from United States and European cooperative groups. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(14):2384–2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss AR, Lyden ER, Anderson JR, et al. Histologic and clinical characteristics can guide staging evaluations for children and adolescents with rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3226–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodeberg DA, Stoner JA, Garcia-Henriquez N, et al. Tumor volume and patient weight as predictors of outcome in children with intermediate risk rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2011;117(11):2541–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodeberg D, Arndt C, Breneman J, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of rhabdomyosarcoma patients with isolated lung metastases from IRS-IV. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(1):256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohan AC, Venkatramani R, Okcu MF, et al. Local therapy to distant metastatic sites in stage IV rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sparber-Sauer M, von Kalle T, Seitz G, et al. The prognostic value of early radiographic response in children and adolescents with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma stage IV, metastases confined to the lungs: A report from the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe (CWS). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams BA, Williams KM, Doyle J, et al. Metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: a retrospective review of patients treated at the hospital for sick children between 1989 and 1999. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26(4):243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carli M, Colombatti R, Oberlin O, et al. European intergroup studies (MMT4–89 and MMT4–91) on childhood metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(23):4787–4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dantonello TM, Winkler P, Boelling T, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma with metastases confined to the lungs: report from the CWS Study Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(5):725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pappo AS, Lyden E, Breitfeld P, et al. Two consecutive phase II window trials of irinotecan alone or in combination with vincristine for the treatment of metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(4):362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crist W, Gehan EA, Ragab AH, et al. The Third Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(3):610–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1. Direct pairwise comparison of event-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) between patients with RMS metastatic disease limited to the lung and metastatic disease limited to a single extrapulmonary site. Direct pairwise comparison of event-free survival (C) and overall survival (D) between patients with RMS metastatic disease limited to the lung and metastatic disease to multiple sites (2 or more sites with or without lung).