Abstract

Endocrine disrupting chemicals are a group of pollutants that can affect the endocrine system and lead to diseases and dysfunctions across the lifespan of organisms. They are omnipresent. They are in the air we breathe, in the food we eat and in the water we drink. They can be found in our everyday lives through personal care products, household cleaning products, furniture and in children’s toys. Every year, hundreds of new chemicals are produced and released onto the market without being tested, and they reach our bodies through everyday products. Permanent exposure to those chemicals may intensify or even become the main cause for the development of diseases such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular diseases and certain types of cancer. In recent years, legislation and regulations have been implemented, which aim to control the release of potentially adverse endocrine disrupting chemicals, often invoking the precautionary principle. The objective of this review is to provide an overview of research on environmental aspects of endocrine disrupting chemicals and their effects on human health, based on evidence from animal and human studies. Emphasis is given to three ubiquitous and persistent groups of chemicals, polychlorinated biphenyls, polybrominated diphenyl ethers and organochlorine pesticides, and on two non-persistent, but ubiquitous, bisphenol A and phthalates. Some selected historical cases are also presented and successful cases of regulation and legislation described. These led to a decrease in exposure and consequent minimization of the effects of these compounds. Recommendations from experts on this field, World Health Organization, scientific reports and from the Endocrine Society are included.

Keywords: Endocrine disruption, human health, children, environment, policy, precautionary principle

Introduction

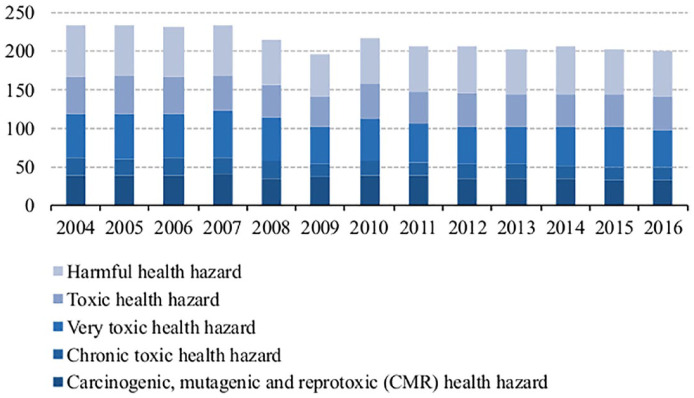

Some of the biggest problems that humankind faces are climate change and global warming, biodiversity loss, ocean dead zones, achieving energy sustainability, increasing population, which is estimated to exceed nine billion in 2050, 1 overconsumption of resources, waste management, air, soil and water pollution. These are posing dramatic challenges that can jeopardize our future. A myriad of synthetic chemicals has been released into the environment, especially since World War II, and some in large quantities. In 2015, the total production of chemicals within the 28 member states of European Union (EU) was 323 million ton, 205 million ton of which were considered hazardous to health. 2 Figure 1 presents the production of chemicals hazardous to health, over the last 12 years, according to five toxicity classes. The production rate does not necessarily translate into the release into the environment and human exposure, but it is, nevertheless, an indicator of the potential impact on human health and on the environment.

Figure 1.

Production of chemicals considered hazardous to health in European Union 28 countries (EU-28), between 2004 and 2016 (million tons). Consumption does not differ significantly from production. However, consumption is generally higher than production, due to importation.

Source: Eurostat.

Concerns regarding exposure to these chemicals and potential adverse effects are due, in part, to the increasing number of reports of their role as their endocrine disrupters. In the last 20 years, a large number of research papers have been published, which address various aspects of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including environmental occurrence, ecological effects and consequences of human exposure.

In 1996, with support from the European Commission, the World Health Organization (WHO), Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and other national authorities, the international meeting, ‘The impact on the endocrine disrupters on human health and wildlife’, appealed for a better understanding of epidemiological aspects, and to the needs of identification, monitoring and the development of methods to test and screen EDCs (The Weybridge Report). 3 This meeting considered that measures to reduce exposure to these chemicals should be made according to the Precautionary Principle (1992 Rio Declaration) (Rio Declaration, 1992 Principle 15:

In order to protect the environment, the Precautionary Approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.

In a Judgement (C180/96, point 99), on 5 May 1998, the Court of Justice, has said that ‘where there is uncertainty as to the existence or extent of risks to human health, the Commission may take protective measures without having to wait until the reality and seriousness of those risks become apparent’). The Precautionary Principle arose from environmental considerations and can be viewed as an ethical ideal. Another outcome of this international meeting was the definition of EDCs: an EDC was defined as an ‘exogenous substance or mixture that alters function(s) of the endocrine system and consequently causes adverse health effects in an intact organism, or its progeny, or (sub)populations’. Also, ‘a potential endocrine disrupter is an exogenous substance or mixture that possesses properties that might be expected to lead to endocrine disruption in an intact organism, or its progeny, or (sub)populations’ 4 (WHO, International Programme on Chemical Safety). 5

In 2009, The Endocrine Society published the first Scientific Statement on EDCs addressing the concerns to public health, based on evidence from animal models, clinical observations and epidemiological studies. 6 The statement includes evidence of the effects of endocrine disrupters on male and female reproduction, breast development, prostate and breast cancer, neuroendocrinology, thyroid, metabolism and obesity, and cardiovascular endocrinology, and calls for an increased understanding of the effects of EDCs, with the involvement of individual and scientific society stakeholders in communicating and implementing changes in public policy and awareness. 6 In 2013, the WHO released The State of the Science of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals - 2012 7 expressing concern on the impact of EDCs; this was supported by extensive research that improved the understanding of the mechanisms involved in endocrine disruption and stated that there is ample evidence attesting to the impacts of EDCs on human and wildlife health. 7 Even after decades of research on EDCs, and the two decades since the Weybridge Report, there is still no consensus on EDCs among scientists, regulators and activists, either within the EU or at the international level. On 16 December 2015, a judgement of the General Court of the Court of Justice of the EU declared that the European Commission ‘unlawfully failed to adopt delegate acts concerning the scientific criteria for the determination of endocrine properties’ (Case T-521/14). 8 The European Commission was expected to deliver, before December 2013, scientific criteria for the definition and identification of chemicals that may possess endocrine disrupting properties, and to adopt and delegate acts according to such criteria. 9 In October 2017, the member states’ representatives rejected the Commission’s definition on EDCs, and, 1 year later, there is still no defined strategy that addresses the challenges they pose. The regulation of chemicals includes carcinogens, mutagens, teratogens and substances that disrupt reproduction. EDCs represent a relatively new classification, involving different chemical classes that are able to mimic or antagonize endogenous hormones. Although there is no consensus on their regulation, EDCs are addressed in various cases in EU law, such as the Water Framework Directive, Registration, Evaluation and Authorization of Chemicals (REACH), Plant Protection Products Regulation (PPPR) and Cosmetic Regulation. These will be described briefly below.

EDCs are found in many of our everyday products, for example, those that we use for personal or domestic care, in the air we breathe, in the food we eat and in the water we drink. The challenges that arise from the field of endocrine disruption are the immense diversity of chemicals produced, but not tested, the mixtures and the unknown interactions between them, together with their consequent effects. The lack of an effective and strong legislation and regulation poses a significant threat to humans, animals and plants, and contributes to the exposure to chemicals that may disrupt the endocrine system.

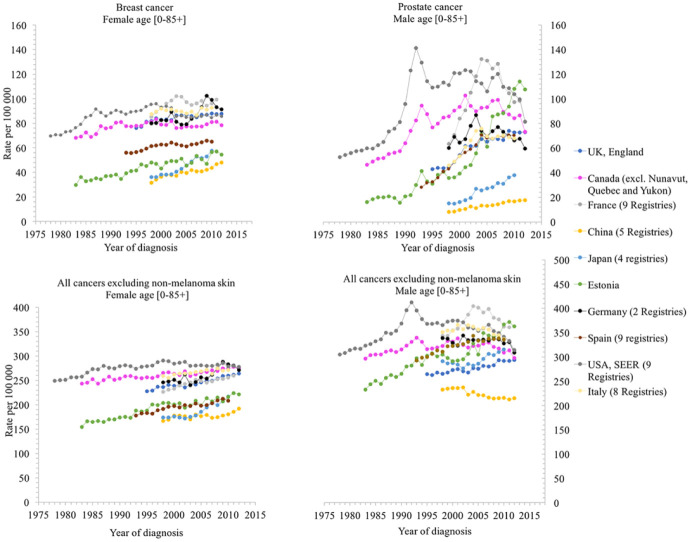

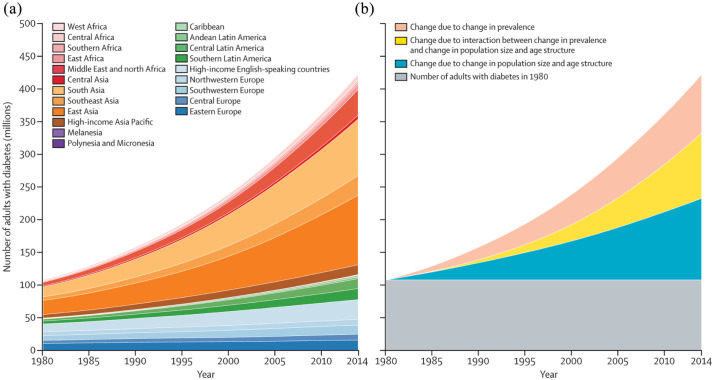

Since World War II, more than 140,000 synthetic chemical compounds have been produced; about 1000–2000 new compounds are synthesized each year, 10 and approximately 800 chemicals are known, or suspected, to interfere with endocrine system. 11 The increasing incidence rate of some medical conditions, such as breast and prostate cancer, types 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, in the last decades, and the higher rates observed in the industrialized world cannot be explained only by genetic factors (see Figures 2 and 3). Environmental factors, nutrition and lifestyle, viral diseases, are some of the other variables in such a complex system.

Figure 2.

Trends in cancer incidence, in the selected countries, by year of diagnosis. Data on trends in incidence for breast, prostate and all cancers excluding non-melanoma skin, for the selected countries, were extracted from CI5plus-Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Time Trends (http://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5plus/Default.aspx).

Figure 3.

Worldwide trends in the number of adults with diabetes by region (a) and decomposed into the contributions of population growth and ageing, rise in prevalence and interaction between the two (b). 12

Source: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8 and Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY).

In recent decades, several chemicals, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), dioxins, furans, pesticides, have been shown to interfere with various metabolic pathways, leading to alterations in development, growth and reproduction, and causing medical conditions which may not become evident until many years after exposure (see below). In 2005, the Environmental Working Group (EWG) found an average of 200 industrial chemicals and pollutants present in the umbilical cord blood, and tests revealing a total of 287 chemicals. 13 Among these were compounds banned by the Stockholm Convention. Of the total 287 chemicals detected in umbilical cord blood, 180 are reported to cause cancer in humans or animals, 217 are toxic to the brain and nervous system, and 208 cause birth defects or abnormal development. 14 Chemical exposure begins in the womb, even, potentially, in pre-conception stages, and can have a dramatic effect later in life. Certain environmental chemical pollutants can cause such effects weeks, months or even years after exposure (see below). Available data from these studies clearly indicate that the general population is exposed to at least, some of these pollutants. Many chemicals present in the environment originate in municipal wastewater. Several environmentally relevant organic chemicals, such as pharmaceuticals, pesticides, plasticizers, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), are not eliminated by conventional water treatment methods, and, through the urban water cycle, can enter ground and surface waters (Table 1). In addition, these pollutants can persist in the environment, bioaccumulate through the food chain and reach drinking water.

Table 1.

Endocrine disrupting chemicals found in consumption and surface waters.

| Compound | Adverse effects | Occurrence | Concentration (ng L−1) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | Carcinogenic, endocrine disrupter, hepatotoxic | Consumption waters (Germany) | 43–519 | 15 |

| Carbamazepine epoxide | Enzyme inhibition in fish | Consumption waters (Spain) | 2 | 16 |

| 17α-ethinyloestradiol | Endocrine disrupter | Europe | 0.3 | 17 |

| Ibuprofen | Surface waters (River Minho, Portugal) | 204.0 | 18 | |

| Bisphenol A | Endocrine disrupter, cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, infertility | Surface waters (Rivers Ave, Portugal) | 7.9–521.8 | 19 |

| 17α-ethinyloestradiol | Endocrine disrupter | Surface water (Ria Formosa Portugal) | 14.4–25.0 | 20 |

| Nonylphenol | Oestrogenic properties, endocrine disrupter | Surface water (Ria Formosa Portugal) | 12.2–547 | 20 |

This review provides an overview of research on environmental aspects of endocrine disrupters. Emphasis is given to three ubiquitous and persistent group of chemicals, for example, PCBs, PBDEs and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs), together with two non-persistent, but ubiquitous groups, bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, whose occurrence and effects on human health and wildlife have been widely reported. Selected historical cases are also presented to highlight the fact that, generally, human corrective actions tend to appear only following catastrophes, and in turn, the importance of the precautionary principle, a science-based approach that accepts uncertainty and requires action in order to avoid and prevent harm. Some successful cases are described of regulation and legislation that have prevented or decreased the exposure, and consequent effects, of these compounds. Recommendations from WHO, scientific reports and from the Endocrine Society are also included.

Understanding the processes involved

Our current knowledge of the mechanisms involved in the disruption of the normal functions of cells by EDCs is still limited. Nevertheless, it is known that EDCs can have multiple mechanisms of action, interact with different receptors and affect the entire endocrine system. The majority of studies focus on the oestrogen, androgen and thyroid receptors and their mechanistic pathways. Accordingly, this section will give only a very brief description of the normal endogenous oestrogen pathway and their disruption by oestrogenic EDCs. There are other mechanisms of action of EDCs (Table 2), especially those involving the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) which regulates the expression of several genes, including the cytochrome P450 (CYP)-1 gene family members and glutathione S-transferase M, which mediates many of the responses to environmental toxic chemicals. 34 An overview of some of the mechanisms involved can provide insight for more comprehensive understanding of the impact on human health. For additional background information, or detailed description of the endocrine events and their disruption by EDCs, several excellent reviews are available in the literature that cover this broad and continually evolving research field.21,35–38

Table 2.

Human nuclear receptors, their function, some major target genes and important ligands.

| NR | Function | Examples of target genes | Examples of endogenous ligand | Examples of endocrine disrupting chemicals | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Androgen (AR) | Male sexual development | Probasin, KGF, p21, maspin, PSA | Testosterone | p, p′-DDE, pesticides, plasticizers, phthalates, alkylphenols | 21–24 |

| Oestrogen (ER) | Female sexual development | IGFBP4 GREB1 CTSD |

Oestradiol | BPA, benzophenone derivatives, parabens, pesticides, dioxins, furans, heavy metals | 23,25,26 |

| Thyroid hormone (TR) | Metabolism heart rate | THRB | Thyroid hormones | PCBs, BPA, dioxins, furans, PBDEs, phthalates pesticides, perchlorates, phytoestrogens | 23,27–29 |

| Progesterone receptor (PR) | Female sexual development | Progesterone | Musk compounds, BPA, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides | 23,24 | |

| Glucocordicoid receptor (GR) | Development metabolism stress response | Cortisol | BPA, phthalates, PCBs, DPCBs, methyl sulphones, tolylfluanid | 23,24 | |

| Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) | Proliferation and differentiation Neurogenesis Circadian rhythm |

Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) | Indol and tryptophan derivatives | PCBs, dioxins, herbicides, indoles, pesticides, flavonoids | 23,24 |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) | Gluconeogenesis Lipid, fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism |

Cytochrome P450s (CYPs), glutathione S-transferase (GST) | Lipids Arachidonic acid derivatives Linoleic acid derivatives |

BPA, organotins, phthalates | 23,24 |

| Pregnane X receptor (PXR) | Xenobiotic detoxification Glucose tolerance and energy balance |

Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) CYP3A CYP2B CYP2Cs OATP2 MRP2 MDR1 GST-A2 BSEP CYP7A |

5 β-cholestane-3α, 7α, 12α-triol steroids | PCB, BPA | 24,30–32 |

| Retinoid X receptors (RXRs) | Cellular proliferation Development, growth and homeostasis |

Retinoic acid | Organochlorine pesticides, styrene dimers, alkylphenols parabens, organotins | 22,33 | |

| Constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) | Xenobiotic detoxification | CYP2B CYP3A CYP2Cs OATP2 MRP2 UGT1A1 |

Androstane and derivatives | PCB | 24,32 |

DDE: dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene.

The endocrine system is a complex network of glands that release specific hormones into the blood stream. It controls growth, development, metabolism, circadian cycles, glucose levels, sex hormones, T-cell development, calcium levels and many other functions. 39 The endocrine glands, located at various sites in the body, release certain chemicals, the hormones, that affect specific cells, target cells and receptors. Other chemicals can interfere with this hormone action. When they enter the body, EDCs mimic or antagonize natural hormones, interacting with hormone receptors, and can potentially disrupt the body’s normal functions.

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are a class of proteins, transcription factors, that regulate gene expression, and are activated by steroid hormones, such as oestrogen and progesterone, in addition to other lipid-soluble signal molecules such as retinoic acid, oxysterols and thyroid hormones. 39 Some of these NRs are considered to be orphans, as their specific ligand or physiological functions remain unknown. So far, 48 NRs have been discovered in humans through sequencing of the human genome. 40 A review on the mechanism of action of the NRs can be found in the paper of Gronemeyer et al. 22 Steroid hormone receptors, such as the oestrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), progesterone receptors and androgen receptors, are included in this NRs superfamily. Many EDCs exhibit oestrogenic activity, targeting oestrogen receptors (ERs), in particular, ERα and ERβ. EDCs that interfere with ER signalling generate biological responses via both genomic (nuclear) and non-genomic (extranuclear) pathways. 41

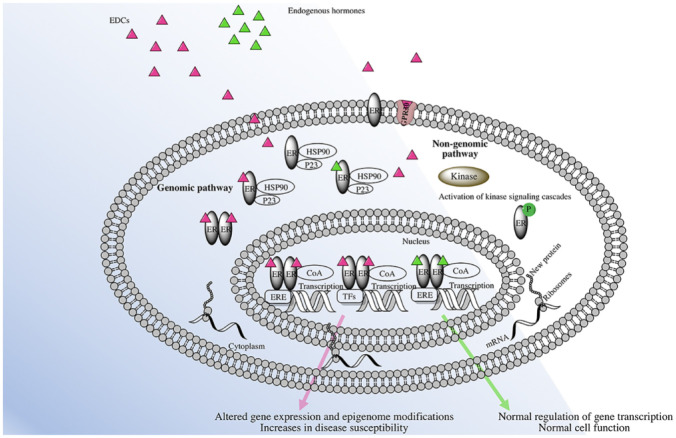

Oestrogen is not only a reproductive hormone, but also exerts effects on almost all tissues of the body, 35 and has been linked to the development of conditions such as cancer, endometriosis, obesity, insulin resistance as well as cardiovascular, autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases. 35 Oestrogens act through three types of receptors, the classical ERs, the ERα and ERβ, and the recently discovered, non-classical, G protein-coupled membrane receptor 30, GPR30. The GPR30 receptor is believed to react through non-genomic mechanisms, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Representation of endocrine disruption by EDCs.

ER: oestrogen receptor; ERE: oestrogen response element; CoA: coactivators; P: phosphorylation; TF: transcriptional factor.

According to the proposed classical model of oestrogen action, following the binding of oestrogen to the receptor in the cytoplasm, this complex dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus where it binds to a specific oestrogen responsive element (ERE), located within the promoter region of the target gene, to regulate gene transcription (Figure 4).35,42 The steroid hormone receptors are bound to protein chaperones, such as Hsp 70 and Hsp 90, which regulate their functions. 43 Once the ligand binds to the receptor in the cytoplasm, the receptor is freed from the protein chaperone and the co-chaperone p23, allowing homodimerization and movement towards the nucleus. The co-chaperone p23 is a small protein, with a relatively simple structure, and is found in all eukaryotes, from yeast to humans; it is best known as a co-chaperone of Hsp90. The p23 molecule is involved in various cellular processes. 44 Once in the nucleus, the oestrogen–ER complex recruits transcriptional coactivator proteins and components of the ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase complex that induce the transcription of target genes in response to the particular ligand. 35

Some EDCs, such as alkylphenols, BPA, dioxins, furans, heavy metals, and halogenated hydrocarbons, 36 can cross the cell membrane and bind directly to these receptors, either activating them by acting as agonists, or inhibiting them and acting as antagonists to the NRs. Thus, either a new protein is synthesized or messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) transcription is terminated.

This NR activation can occur with picogram quantities and nanomolar concentrations 40 of EDCs and, as with the steroid hormones, these can have an impact at similar very low doses.40,45,46

In the genomic pathway, EDCs bind to ERs, in particular ERE in the nucleus, affecting the transcription of target genes in the nucleus. The non-genomic pathway of EDCs may occur through the binding of GPR30, located in the cytoplasmic membrane, and consequently triggering subsequent stimulation of protein kinase activation and phosphorylation, affecting the transcription of target genes, by the ERE or by interaction between ERs with other transcriptional factors. The interaction between ERs and GPR30, in gene expression and intracellular signalling, can result in a cellular response, which may lead to adverse effects on organs, for example, carcinogenesis.

Persistent EDCs

POPs

POPs constitute a class of chemicals that share similar properties, such as persistence in the environment, high toxicity and half-life times of years or even decades before their degradation into less toxic forms (Table 3). They bioaccumulate through the food chain, and their lipophilicity means they will accumulate in fatty tissues, and thus pose a threat to human health and wildlife. Bioaccumulation leads to biomagnification, as POPs are absorbed by lower trophic organisms, such as phytoplankton, that are consumed by zooplankton, and accumulates in the fatty tissues of the organisms that are then eaten by higher organisms. This possibly magnifies the effect of POPs up the food chain. This concentration effect reaches its maximum level in top predator species, such as humans and other mammals. POPs have moderate volatility and are chemically and environmentally stable. Because of these characteristics, they may travel long distances and may be found everywhere, including the Arctic, Antarctica and even remote Pacific Islands. 73 POPs that are deposited and accumulated in the soil and water can evaporate or sublimate to the atmosphere and travel long distances, to condensate again, for example, in these remote regions.74,75 Through this cycle, these pollutants can contaminate indigenous people and wildlife in such regions, by entering in the food web or through inhalation. 74 Because of their genetics and lipid accumulation, indigenous people often have the highest levels of contamination with POPs, even though they did not produce or directly consume the products. POPs include polyhalogenated industrial chemicals, such as PCBs, polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs), OCPs such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), aldrin and heptachlor, and industrial by-products such as polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (Figure 4 and Table 5). They were banned by the Stockholm Convention, which became international law in 2004. However, some are still used. Mosquitoes that spread malaria are responsible for significant morbidity and the deaths of one million people each year, mostly children, and the solution for this problem is not clear. DDT is effective in killing and repelling the mosquitoes that transmit malaria. Although DDT is highly toxic to health and to the environment, in some countries, mainly in Africa, the benefit of using this pollutant to tackle malaria may compensate for the risk.

Table 3.

Examples of EDCs with widespread distribution in the environment and their reported health effects.

| Endocrine disrupting compound | Used for | Found in | Biological half life (in humans) | EDCs | Reported health impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenol A | Plasticizer Improvement of physical, thermal and mechanical properties |

Weak bond polycarbonate Epoxy resins Food and drink packaging |

6 h | 2.04 µg L-1 for children (n = 653) 1.88 µg/L for adults (n = 639) |

Oestrogenic effect Increase prostate, child behaviour problems, breast cancer, metabolism and breast cancer risk Anti-androgen Child behaviour problems |

46–50 |

| 17-α ethynyloestradiol | Synthetic hormone used as contraceptive pills | Rivers, groundwaters and superficial waters | 17 h | Mimic the endogenous oestrogen | 17,51 | |

| Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) | Flame retardants in furniture, textiles, plastics, electronics, etc. | Environment, human blood, placenta, foetal cord blood, urine and breast milk, children, fish, marine mammals and eggs | 2–16 years | 1.80–16.5 ng g−1 in human biological samples | Increase cell proliferation, carcinogenic, neurodevelopment deficit | 52–57 |

| PCBs | Dielectric fluids in capacitors and transformers, additives and plasticisers in paints, plastics and rubber sealants, pesticides, etc. | Environment and wildlife, human breast milk, human blood | Few years to 35 years | 140 ng L-1 of PCB-153 in cord serum | Intellectual impairment in young children Immunotoxicity, ectodermal defects, development delay, behavioural problems and poor cognitive development, neurotoxicity, cancer |

58–63 |

| Phthalates | Plasticisers in plastic, PVC baby toys, flooring, perfume, etc. | Environment, human biological fluids | 36 h | 2 × 10−9–8 × 10−6 M | Low sperm counts, metabolism, birth defects, asthma, neurobehaviour problems, cryptorchidism, hypospadias | 48,64–67 |

| TCDD | Pesticides, unwanted by-products of thermal and industrial processes | Environment, wildlife, food chain | 5–10 years | 2 ρg g-1 body fat | Changes in the sex ratio, chloracne, porphyria, transient hepatotoxicity, and peripheral and central neurotoxicity | 56,66–69 |

| Triclosan | Disinfectant and antiseptic used in soaps, toothpastes, kitchen utensils, toys, bedding, clothes | Environment, wildlife, human biological fluids | 21–96 h in human plasma | 1.65 µg L-1 estimate of urinary concentration per unit dose of triclosan | Biocidal effects and contributes to bacterial resistance, dermatitis, skin irritation. Triclosan react with chlorinated water producing chloroform | 48,70–72 |

EDC: endocrine disrupting chemical; TCDD: 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin.

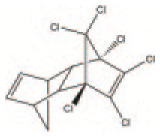

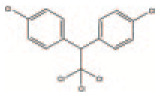

Table 5.

Persistent organic pollutants listed in Annexes A, B and C in the Stockholm Convention.

| Chemical | Use | Molecular formula | Chemical structure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

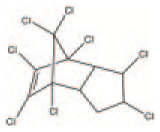

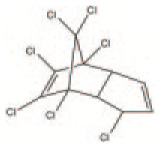

| Annex A (Elimination) Aldrin | Pesticide | Organochlorine insecticide | C12H8Cl6 |

|

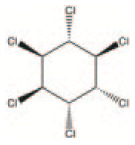

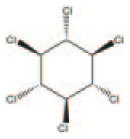

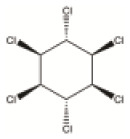

| α-hexachlorocyclohexane | Pesticide/by-product | Organochloride insecticide By-product of lindane (for each ton of lindane produced, 6–10 ton of α-hexachlorocyclohexane are also obtained) |

C6H6Cl6 |

|

| β-hexachlorocyclohexane | Pesticide/by-product | Organochloride insecticide Same properties as α-hexachlorocyclohexane |

C6H6Cl6 |

|

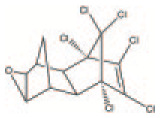

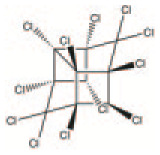

| Chlordane | Pesticide | Used extensively to control termites pesticide for corn and citrus crops, environmental half-life of 10–30 years | C10H6Cl8 |

|

| Chlordecone | Pesticide | Chlorinated pesticide and by-product of Mirex | C10Cl10O |

|

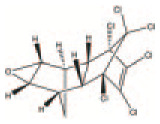

| Dieldrin | Pesticide | Organochloride pesticide | C12H8Cl6O |

|

| Endrin | Pesticide | Insecticide | C12H8Cl6O |

|

| Heptachlor | Pesticide | Insecticide. Can persist in the environment for decades | C10H5Cl7 |

|

| Hexabromobiphenyl | Industrial chemical | Flame retardant | C12H4Br6 |

|

| Hexabromodiphenyl ether and heptabromodiphenyl ether (commercial octabromodiphenyl ether) | Industrial chemical | Flame retardant Theoretical number of possible congeners is 209 147 |

C12 H(0-9)Br(1-10)O |

|

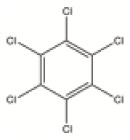

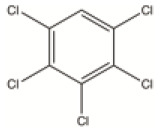

| Hexachlorobenzene (HCB) | Pesticide/industrial chemical | Used as fungicide in food crops | C6Cl6 |

|

| Lindane | Pesticide | Organochlorine pesticide | C6H6Cl6 |

|

| Mirex | Pesticide | Organochloride pesticide | C10Cl12 |

|

| Pentachlorobenzene | Pesticide/industrial chemical | By-product of the manufacture of carbon tetrachloride and benzene, intermediated in the production of pesticides | C6HCl5 |

|

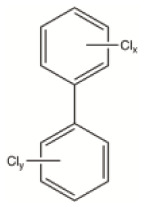

| Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | Industrial chemical | Used in agriculture and in a number of industrial applications electric transformers and capacitors | C12H10-nCln |

|

| Tetrabromodiphenyl ether and pentabromodiphenyl ether | Industrial chemical | Additive flame retardant | C12H6Br4O C12H5Br5O |

|

| Toxaphene | Pesticide | Pesticide used on cotton, crops and vegetables. Half-life of up to 12 years | C10H8Cl8 |

|

| Annex B (restriction) | ||||

| DDT | Pesticide | Pesticide used in agriculture and to control malaria | C14H9Cl5 |

|

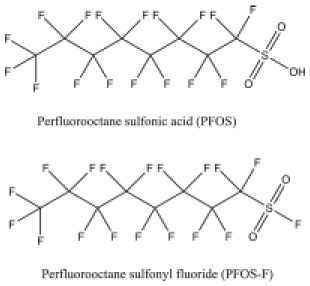

| Perfluorooctane sulphonic acid (PFOS), its salts and perfluorooctane sulphonyl fluoride (PFOS-F) | Industrial chemical | Man-made fluorosurfactant, used in impregnation formulations for textiles, leather, paints, varnishes, carpets, etc. | C8HF17O3S C8F18O2S |

|

| Annex C (unintentional production) | ||||

| Dioxins PCDDs |

By-product | 75 congeners | C12 H9-nClnO2 |

|

| Furans PCDFs |

By-product | 135 congeners | C12 H9-nClnO |

|

| HCB | By-product | By-product from the manufacture of certain chemicals that can give rise to dioxins and furans | C6Cl6 |

|

| PCBs | By-product | Besides being industrial chemicals, are also by-products | C12H10-nCln |

|

| Pentachlorobenzene | By-product | Unintentionally produced during combustion, thermal and industrial processes | C6HCl5 |

|

Some pollutants are granted exemptions for use, such as DDT in certain countries where malaria poses a major health threat, or some PCBs used in old electric transformers and capacitors in developing countries, where the alternatives are too expensive or too complicated to produce.

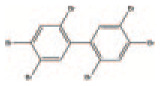

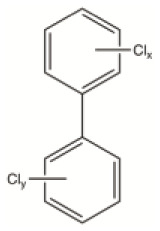

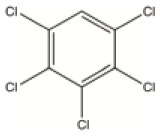

PCBs

PCBs constitute a class of chemically stable aromatic compounds in which 1 to 10 chlorine atoms are attached to a biphenyl backbone, allowing for, theoretically, 209 different congeners. PCBs were widely used in agriculture and in a number of industrial applications during the past decades. Their applications included dielectric fluids in capacitors and transformers, hydraulic fluids, their use in building materials, such as additives and plasticisers in paints, plastics and rubber sealants, copying paper, adhesives, pesticides. Due to their widespread use and careless disposal over several decades, PCBs have become widely distributed in the environment; although bans and restrictions exist on them at the global level, they are still found in the atmosphere, rivers, fish, other wildlife, human breast milk and other biological samples and in ecosystems. The toxic impact of PCBs on human health and on the environment was first recognized in the 1960s, in particular with the Yusho incident in Japan, and later, with the Yu-Cheng accident in Taiwan.

PCBs exhibit endocrine disrupting effects, such as ERs’ transcriptional activity and breast cancer cell line MCF-7 proliferation, and affect enzymes mediated by thyroid hormone. 76 In addition to the bioaccumulation and biomagnification characteristics of PCBs, these chemicals have also been passed to the future generations through pregnancy and breastfeeding, thus exposing the most vulnerable in the womb and infancy during critical stages of development, where the disruption can have a dramatic effect later in life. Because of the strong evidence for them inducing cancer in humans and in animals, PCBs were classified in 2013, by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).59–61

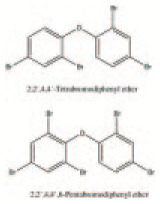

PBDEs

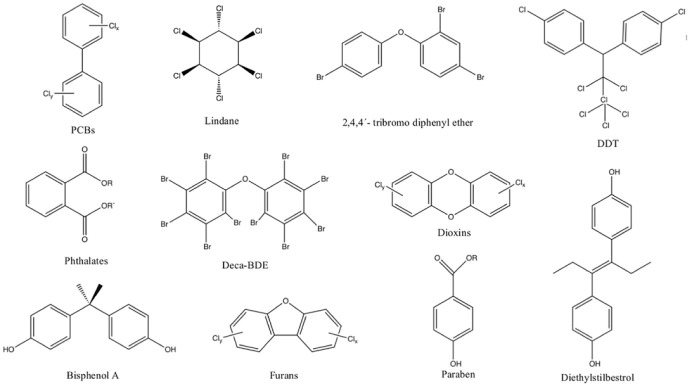

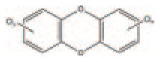

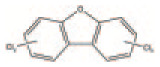

PBDEs constitute a class of polyhalogenated aromatic compounds with a basic structure consisting of two phenyl rings linked by an oxygen atom, with a variable number of from 1 to 10 bromide atoms, allowing for 209 different possible congeners, which depend on the number and position of the bromine atoms (Figure 5). Only a few of the 209 different combinations are commercially available, and their toxicity depends on the specific bromine substitution. The congener deca-BDE is poorly absorbed and rapidly eliminated. 53 In contrast, the congeners tri- to hexa-BDEs are strongly absorbed, slowly eliminated and strongly bioaccumulative. 53

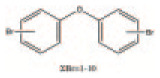

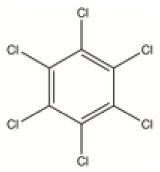

Figure 5.

Molecular structures of common endocrine disrupters.

PBDEs are widely used as brominated flame retardants, and are present in a number of consumer goods, plastics, electronics, furniture and textiles. Although PBDEs have been gradually phased-out worldwide (in the EU they were banned in 2004 and 2008), biomonitoring studies indicate that they are still ubiquitous in human blood and breast milk worlwide. 77 A number of older products, particularly e-wastes, such as obsolete electronic and electrical items, contain significant amounts of these pollutants that are still being released into the environment, leading to contamination of ecosystems. PBDEs have been found in fish, eggs, human breast milk and in infants and toddlers, probably as a result of contamination via house dust. The highest concentrations are found at the top of the food chain, indicating biomagnification 53 . The exposure routes include diet, ingestion, inhalation of indoor dust and dermal contact.

Certain PBDEs and their mixtures have been shown to disrupt the thyroid hormone thyroxine and have been associated with neurodevelopment deficits in rats and humans. Mixtures of PBDEs have increased cell proliferation in human breast cancer cell lines, and also carcinogenic effects in humans.52–55

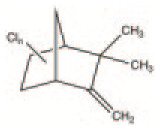

OCPs

OCPs are a ubiquitous, diverse group of POPs. Representative members of this group include DDT, mirex, dieldrin, chlordane, heptachlor, endrin, hexachlorobenzene (HCB), aldrin and toxaphene, which are listed in the so-called dirty dozen, banned by the Stockholm Convention. These pesticides were extensively used in agriculture and as insecticides for mosquito control between the 1940s and 1970s. Although banned, as a result of their strong persistence in the environment and bioaccumulation, the principal metabolites of DDT are detectable in more than 25% of the general population.78,79 The adverse health effects of OCPs on animals and human health have been extensively reported in the literature and linked to diabetes, cancer, neurodevelopment problems in children, miscarriages and many other health outcomes. Due to agricultural activities, traces of OCPs and their metabolites have been found in both surface and groundwater. The presence of OCPs in groundwater has been associated with increased risk of cancer among people consuming the contaminated supplies. The presence of these pollutants in several shallow groundwater samples and the corresponding potential health hazards were recently discussed. 80 In this study, HCB, hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), resulting from the degradation of lindane, and p, p′-DDE (dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene), a DDT metabolite, were detected, several years after their use. When the OCPs reach groundwater, they may remain there for several years. Human exposure towards OCPs includes the consumption of food and water contaminated with residues and their degradation products, dermal contact and inhalation. As with the other POPs, OCPs are characterized by their persistence, bioaccumulation and biomagnification, lipophilicity, and they may be transported over long distances by winds and ocean currents.

Non-persistent EDCs

BPA

BPA, with its full IUPAC name, 4-(2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) propan-2-yl)phenol, is an important monomer, used for the production of polycarbonates, epoxy resins, polyesters, polysulfones and polyether ketones and is also applied as polymer additive in plasticizers and halogenated flame retardants. It is present in a wide range of applications including baby bottles and linings for metal-based food and beverage cans, ophthalmic lenses, medical equipment, consumer electronics and electric equipment.

BPA was first synthesized by the Russian chemist Aleksandr P. Dianin in 1891 81 who reacted phenol with acetone in the presence of an acid catalyst. In 1905, Theodor Zincke also reported its synthesis. 82 In the 1930s, BPA was found to have oestrogenic activity, but, because of the development in 1938 of the more powerful synthetic oestrogen, diethylstilbestrol (DES), which is stronger than natural oestrogen, BPA was ignored for this application. In 1953, the Bayer chemist Hermann Schnell synthesized polycarbonates by reacting BPA with phosgene. The new material produced was clear, strong and stable and could be heated in microwave ovens without deformation. The production of new polycarbonates reached industrial levels in the 1960s and BPA production has increased greatly since then. In 2015, the production of BPA was estimated at more than 4.5 million ton.83,84 Each year, more than 100 ton is released into the atmosphere and is found in air, drinking water, house dust, food, lakes, sea and soil. BPA is ubiquitous. Human exposure occurs through food, drinking water, household products, cosmetics, medical equipment, dental materials and occupational sources. 85 The polymerization of polycarbonate plastics is not 100% complete, and, as consequence, the unbound monomer, or the additives, can easily leach out of the products into the environment. 86 Prompted by the broad applications of BPA, several studies have demonstrated continuing exposure of the general population to this chemical.

Although the oestrogenic activity of BPA is lower than that of natural estrogens,47,87 its prevalence at high concentrations in the environment, including surface, ground and drinking waters, poses a potential risk to human health.

In humans, after exposure, almost 100% of BPA is eliminated in the urine, excreted mainly as BPA-glucuronide. 88 In contrast to PCBs, which can persist in the human body for decades, 89 BPA has an average half-life of approximately 6 h in humans. 47 However, in spite of this short half-life, BPA can be considered as persistent due to its widespread occurrence and the continuous exposure that the population receives. There are several studies reporting the presence of BPA in urine samples of children and adults.47,88,49 BPA is found in the amniotic fluid, providing evidence for its passage through the placenta. 90 Its presence has been reported in maternal and foetal serum and amniotic fluid, indicating significant exposure during the prenatal stage. 90 In a biomonitoring study, 100% of the 81 children examined revealed the presence of BPA in their urine samples. The median intakes estimated for dietary ingestion, nondietary ingestion and inhalation were 109, 0.06 and 0.27 ng/kg/day, respectively. 88

A European level project on biomonitoring measured the BPA levels of 653/639 child–mother pairs and determined the mean values of 2.04 µg/L for children and 1.88 µg/L for mothers. Environmental, geographical and life style and dietary habits were considered factors that could predict exposure to BPA. 49

Numerous studies of human biomonitoring of BPA exposure in the global population have been reported. These studies reveal the exposure of more than 90% of the world’s population and demonstrate that there are no differences in the BPA levels between countries or continents, and that the urinary levels among the youngest groups tend to be higher than in the older ones. 49

Following from the restrictions imposed on the use of BPA in many countries, BPA analogues, such as the most common substitutes bisphenols F and S, have been synthesized and have replaced BPA in numerous consumer products. 91 Sixteen bisphenol analogues have been documented and are used commercially in thermal papers, food containers, toys lacquers, dental sealants, personal care products and in many other applications. 91 These analogues are now frequently detected in biomonitoring studies and in the environment 92 and also exhibit endocrine disrupting activity, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, reproductive toxicity and neurotoxicity.91,92

Phthalates

Phthalates are a group of multifunctional industrial chemicals and are used in a wide range of consumer products. They are used as plasticisers, to improve flexibility in plastics, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), or as additives in the textile industry, and as carriers in pesticide formulations. They are added to pharmaceuticals as coatings in time-release pharmaceuticals and are also used as industrial solvents and lubricants. Phthalates are frequently added to consumer and personal care products, such as cosmetics, perfume, deodorants, hair sprays, skin cleansers, to retain colour or fragrance, and are used in medical devices, toys and fuels to enhance performance. They are diesters of phthalic acid (1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid) and an alcohol moiety. The phthalate products display different properties which depend on the length and degree of the branching of the side chain. The branched chain di-(2-ethylhexyl)-phthalate (DEHP), with eight carbon atoms in the alkyl side chain, is one of the most commonly used phthalates worldwide. Between 2012 and 2018, the global consumption of DEHP exceeded 3000 thousand metric tonnes. 93

The polymer cellulose nitrate was synthesized in 1833 by Pelouze, while preparation of cellulose acetate was reported by Schutzenberger in 1865 and that of PVC by Baumann in 1872. 94 However, these polymers were too intractable to be processed and needed addition of substances, plasticisers, to soften them. Gum copal, natural rubber, linseed oil, castor oil and camphor were some of the substances tested to overcome the inherent intractability of these polymers. 94 The high volatility, flammability and unpleasant odour of the most commonly used plasticiser, camphor, triggered the search for alternatives. As a consequence, in the 1900s, diphenyl and dicresyl phthalates, and phthalic esters in general, were patented as plasticisers which avoided these problems. Phthalates became commercial during the 1920s and 1930s, along with a number of new thermoplastic polymers.

The first reports of the adverse effects of phthalates on animals date from 1945. 95 Since then, several reports have been published associating phthalates with a wide range of health outcomes (Table 3).

Phthalates are not covalently bonded to the polymeric matrix and, as such, may be easily and continuously released from the polymer chains to the surrounding environment, during their life cycle. Consequently, human exposure is widespread. Exposure is primarily through ingestion, inhalation and skin contact. As with BPA, phthalates are ubiquitous and the continuous exposure of general population to them has been demonstrated in various biomonitoring studies.96,97 The Scientific Committee on Toxicity, Ecotoxicity and the Environment (CSTEE) NOAEL (No-Observed-Adverse-Effect-Level) identified values for four phthalates di-isononyl phthalate (DINP), di-octyl phthalate (DNOP), di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), di-isodecyl phthalate (DIDP), which settled concerns with the so-called phthalate syndrome. The phthalate syndrome is the variety of effects observed in rat experiments and is characterized by malformations of their reproductive organs, reduced anogenital distances and nipple retention.98,99 Evidence of the human analogue of the ‘phthalate syndrome’ has been reported in recent years and has demonstrated the disruption of the androgen signalling pathway.65,100,101 Phthalates have been implicated in various male malformations of external genitalia, such as cryptorchidism and hypospadias. Reports on the effects of prenatal exposure to phthalates in humans showed that birth outcomes and reduced anogenital distance were associated with high levels of phthalate esters, notably DEHP, in the urine of the mothers during pregnancy.102,103 The incidence of these genital malformations is increasing in male new born babies. 103 In a recent study, the levels of phthalates in urine from 1170 peripubertal girls were measured. Concentrations of phthalates ranged from <1 to 10,000 µg/L and associations between phthalates exposure and puberty age were estimated. 65

Phthalates have been found in several consumer products, and in food, milk, and drinking water. Although the exposure to a single phthalate below a certain threshold does not produce any evident effect, the mixture of several phthalates could exhibit toxicity in the exposed individual. 99

Impact on human health

Although strong and robust evidence is mounting on the adverse effects of EDCs on human health, there is still considerable controversy surrounding this area.7,104–110 The complexities of the multiple causes and effects that lie behind the mode of action of EDCs, coupled with scepticism, denial machines, and industrial interests, contrarian scientists with their argumentum ad hominem, have all fuelled this controversy. In addition, some concepts can be difficult to accept or assimilate.

There is considerable evidence of adverse effects of EDCs in animal models. However, the evidence of their effects on human health is more controversial and challenging. The outcomes of exposure to certain environmental pollutants may only be evident years or decades later. Another difficulty, when assessing the consequences of EDCs on human health, is that humans are exposed to a large number of chemicals; each has specific modes of action, while interactions between them may lead to different results than with the individual compounds. 111

The phrase ‘the dose makes the poison’ is a traditional toxicological assumption first proposed by Paracelsus, where larger doses have a greater impact than lower ones. However, with EDCs, the dose no longer makes the poison, and understanding their toxicity is not a trivial process. Very low doses of some chemicals can have a greater impact on health than much higher ones. At low doses, they can bind to the receptors and induce a biological response. In contrast, higher doses can saturate the same receptors and inhibit the correspondent pathways.110,112 Long-term exposure of some chemicals at extremely low doses can have adverse health effects. The timing of exposure can also be a crucial factor. The toxicity of EDCs is a time-dependent process, and exposure to them during critical stages of development can have dramatic effects later in life. 113

Some historical cases

The historical case of DES is an example of how exposure of a foetus to synthetic oestrogen can adversely impact health later in life. DES was synthesized in 1938 by the biochemist Charles Dodds.114,115 Between the 1940s until the early 1970s, DES was prescribed to millions of American and European women, initially to treat the symptoms of the menopause, and later prescribed to pregnant women to prevent miscarriage, although there is no clinical evidence or adequate testing that supported such a claim. In 1971, Herbst et al. 113 demonstrated that DES causes a rare vaginal cancer in young woman, who were the daughters of mothers who had been exposed to the synthetic oestrogen. Since then, various other reports have been published demonstrating adverse outcomes associated with DES.116–118

Thalidomide, α-phthalimidoglutarimide, was synthesized by Chemie Grunenthal in West Germany in 1954. This company was searching for low-cost production of antibiotics from peptides and, when they failed to demonstrate any antibiotic activity, they decided to explore the potential of this new molecule as a sedative in humans. 103 After the tests in mice, rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, cats and dogs have not apparently revealed no toxicity or side effects, Chemie Grunenthal distributed free samples to doctors in West Germany and Switzerland. In 1957, after the company created its own tests, the ‘jiggle cage’, to demonstrate to the licensing authorities the efficacy of thalidomide as a sedative, it was commercialized, first in Germany and later in other European countries. The drug rapidly became a success and, soon after, was sold in 46 countries. Although studies of the effects on foetus were never performed, the company wrote in 1958 to all German physicians advising the prescription of thalidomide to pregnant women for morning sickness and nausea. 119 In 1961, reports started to appear, linking thalidomide with a variety of birth defects, including the rare malformation phocomelia. Between 1957 and 1961, thousands of babies were born worldwide with severe congenital malformations. Widukind Lenz, a German paediatrician, found that the administration of the drug between the 20th and 36th day of gestation could lead to the development of malformations in the foetus. Although the link with these birth defects precludes its prescription to pregnant women, currently, the drug thalidomide is used with an enormous success in various medical conditions, including erythema nodosum leprosum, immune system disorders, multiple myeloma, cancer and in many other examples.119–121

Another important historical case occurred in Japan in 1968; a rice cooking oil produced by Kanemi Company was accidentally contaminated with PCBs, polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs), polychlorinated quaterphenyls (PCQs) and other compounds from heat exchangers.122,123 Over 1800 people presented a range of symptoms, including dermal lesions, pigmentation of the skin, nails and conjunctiva, numbness of the limbs, irregular menstrual cycles; more than 500 have died from exposure to this contaminated oil. The incident is known as the Yusho oil disease, and clinical and epidemiological studies from it are extensively documented.122–124 From 2001 to 2003, measured mean blood levels of total dioxins and 2,3,4,7,8-penta-chlorodibenzofuran (PeCDF) in Yusho patients revealed that 36 years after the exposure, those levels were 3.4–4.8 and 11.6–16.8 times higher than in a control, providing evidence that PCBs and dioxins persist for many years in the human body. 89

In 1979, a similar case occurred in Taiwan, the ‘Yu-Cheng’ incident, in which 2000 people had consumed PCB- and PCDF-contaminated rice cooking oil. The symptoms were similar to those in the Yusho victims. High mortality from liver diseases was reported within 3 years after the incident 125 and children born to exposed mothers were found to have ectodermal defects, development delay, behavioural problems and poor cognitive development up to 7 years.58,126 A higher prevalence in type 2 diabetes among the Yu-Cheng cohort was also reported. 127

These historical cases drew attention to the possible dramatic consequences to human health and the environment, arising from the production and use of untested and unregulated synthetic chemicals, particularly in critical stages of development.

Exposure to EDCs, and growth, development and health of children

Foetuses, infants and children are particularly vulnerable to contaminants. Various environmental chemicals, including pesticides, PCBs, methyl-mercury, are known to be neurotoxic and may alter brain development. Neurodevelopment is a complex process that begins at conception with the formation of a primitive neural tube, the first stage of brain development, followed by a differentiation of the cells and the formation of the central nervous system. During the first two trimesters of foetal development, the basic structure of the brain is formed. Changes in neural connectivity and function occur in the last trimester and the first few postnatal years. Synaptogenesis and myelination, the most prolonged changes, occur in the last trimester and continue postnatally into adulthood.128,129 The disruption of these complex processes could lead to neurodevelopmental disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), schizophrenia, intellectual disabilities and neurological disorders, such as Rett syndrome (Table 3). The prenatal or early life exposure to EDCs can have repercussions on brain functions later in life. The POPs are of particular concern, due to their chemical structure, persistence and lipophilicity. They are widely dispersed into the environment, accumulate in organisms and can lead to biomagnification in the food chain. PCBs are among the most extensively studied environmental contaminants in terms of their effects on neurodevelopment and cognitive functions. Several reports have revealed PCBs adverse effects of these compounds, which include immunotoxicity, endocrine disruption, neurotoxicity and cancer.

The parental exposure to certain EDCs has been linked with a higher risk of congenital malformations in future progeny and changes in the sex ratio of the offspring. For example, the exposure of men to the dioxin 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) is linked to the decrease of the sex ratio in their offspring. The Seveso disaster occurred in 1976 with the release of the TCDD and resulted in the exposure of the population to this dioxin. It was observed that the children born from parents with the highest exposure to TCDD, in the first decade after the exposure, were all female.68,69 Many epidemiological studies are underway to study the long-term adverse health effect of this dioxin. Another example of the effects of pre-conception stages is related with occupational exposure; the pre-conception exposure of parents to pesticides is linked to the development of congenital malformations of their offspring.130–132

Since 1970, childhood cancer has been rising in Europe and United States by 1% per year, and the data show evidence for an increase in this trend.133,134 The causes of most childhood cancer are largely unknown. A few causes have been established, such as exposure to radiation and carcinogens, timing of exposures and genetic susceptibility to development of cancer, but only a limited number of chemical compounds have been directly linked to childhood cancer.

EDCs in indoor air and dust

New sources of human exposure to EDCs have been identified in indoor environments, such as homes and the workplace. Over the last decades, there has been a marked increase in new materials for building construction, furnishings, carpets, textiles, electrical and electronic appliances, and many other consumer products that are present in indoor environments. These lead to common classes of chemicals, such as formaldehyde, pesticides, phthalates, PCBs, brominated flame retardants, alkylphenols (e.g. nonylphenol, alkylphenol ethoxylates) and parabens, being found in indoor air and dust. Advances in technologies to improve thermal comfort have decreased the ventilation rates of indoor spaces and have, consequently, led to a decline in the quality of air inside the buildings. This has repercussions on health. Respiratory illness, sick building syndrome, allergies and loss of productivity are some the health implications reported.135–137

We spend about 90% of our life in enclosed spaces, particularly the home and workplace, and in cars 138 ; indoor air quality (IAQ), therefore, has a considerable impact on our exposure to contaminants. A number of major studies have been conducted on air and dust pollution of indoor environments (Table 4). The samples collected in these studies were found to have high levels of contaminants, and, in general, their concentrations in indoor air exceed those in outdoor air, and they are considered as ‘one of the most serious environmental risks to human health’.139,142,143

Table 4.

Organic chemicals detected in indoor air and dust.

| Samples (homes) | Number of organic chemicals identified |

Number detected per home |

Most abundant organic chemicals identified |

Concentrations |

References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | Dust | Air | Dust | Air | Dust | |||

| 120 | 52 | 66 | 13–28 | 6–42 | Phthalates, alkylphenols, brominated flame retardants, pesticides | 50–1500 ng m-3 | 139 | |

| 2 | PCBs | PCBs (52, 105 and 153) | – | – | PCBs (52, 105 and 153) | 8–35 ng m−3 | 21–190 µg g−1 | 140 |

| 34 | – | 65 PCBs congeners | – | 65 PCBs congeners | – | – | 260–23,000 ng g−1 | 141 |

| 50 | 63 | – | – | – | Phthalates, alkylphenols, PAHs | >1 µg m−3 | – | 142 |

PCB: polychlorinated biphenyl; PAH: polyaromatic hydrocarbon.

Children are at greater risk than adults since their normal behaviour, such as playing close to the ground, and considerable hand-to mouth and object-to-mouth contacts, increases the exposure through inhalation and ingestion routes. Physiological factors, such as the small body mass, weaker detoxification capabilities, and rapid growth and development, also contribute to the increased risk of health outcomes. 144 The process of ventilation dilutes and removes the chemicals produced by the daily activities and released from indoor sources. However, the removal of the sources of these chemicals would be a more effective way to decrease the exposure to pollutants.

Government policies

As mentioned above, the phrase ‘the dose makes the poison’ has been the basis for implementation of public health policies and imposition of thresholds regulations. However, when dealing with EDCs, the adage should be ‘the dose no longer makes the poison’. For example, studies of the effect of phthalates in animal models have shown that although the doses of each phthalate individually were below the ‘adverse effect threshold’, the mixtures of phthalates exhibited testicular toxicity,64,111 which raises concerns when humans are exposed to a panoply of chemicals every day.

As in many other fields of science, one reason for scepticism among the public on EDCs comes from the influence of predominantly industry backed lobbies. Although there are notable examples of very positive participation of certain individuals in industry, in general, this negative influence can weaken policies, and delay, or even put at risk their implementation protecting human health and the planet. The current legislation and regulations are ineffective to safeguard human population, nature and ecosystems. The tendency has been for the majority of industrial chemicals to go to the market without being extensively tested, and it is only when any adverse effects are dramatically evident, or when major accidents happen, that they are banned or regulated. In contrast, pharmaceuticals are subject to an intense, and very expensive, testing procedure before they can be released on the market. Even when they have shown to be safe, there may always be some secondary effects that could arise, and in such cases, the risk/benefit must be debated. Should not the release of industrial chemicals to the market be subject of similar rigorous procedures? The regulatory process must not be just at the national level, but, instead, a global agreement must be the goal, since some EDCs do not respect barriers or frontiers. POPs, for example, can evaporate from hotter regions and travel thousands of miles around the planet to condensate again in the polar and/or mountainous regions in the so-called grasshopper effect. As stated, the inhabitants in these places, such as the indigenous people from the Arctic regions, have some of the highest values of POPs, and they are far away from where those chemicals were produced or used. 145

Several European and International environmental treaties already exist on EDCs. In 1999, the European Commission’s Scientific Committee on Toxicity, Ecotoxicity and the Environment (CSTEE) and the European Parliament presented the Community Strategy for Endocrine Disrupting, whose objective was to identify the problem of endocrine disruption, its causes and consequences, and to define appropriate policy action to be taken by adopting a strategy in line with the precautionary principle ‘fulfilling the Commissions obligation to protect the health of the people and the environment’. 146

On 22 May 2001, in what can be considered a major achievement, governments of the whole world met in Sweden to sign and adopt an international treaty concerning POPs, and consider the view that they can pose significant threats to health and the environment. This is the Stockholm Convention on POPs. The convention is a global treaty, signed by 152 nations and administrated by the United Nations Environment Programme, with the purpose of protecting human health and the environment from POPs. It comprised five essential aims: ‘eliminate dangerous POPs, starting with the 21 listed in the Convention, support the transition to safer alternatives, target additional POPs for action, clean-up old stockpiles and equipment containing POPs, and work together for a POPs-free future’. 73 The treaty requires Parties to take measure to eliminate or reduce the release of POPs into the environment. It started with 12 substances, ‘the dirty dozen’, which included eight chlorinated pesticides (aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, mirex, chlordane, heptachlor, DDT and toxaphene), two industrial chemicals (PCBs and HCB) and two by-products (PCDFs and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin). The convention entered in force and became international law on 17 May 2004. In May 2009, nine more substances were added. Table 5 lists the POPs banned or restricted under the Stockholm Convention. As of March 2018, the Convention has 182 Parties as signatories. 148

Other important international agreements include the Basel International Convention and the Rotterdam Convention that regulate chemicals, pesticides and hazardous wastes at the global level. 149 The PPPR (No. 1107/2009) and the Biocidal Products Regulation (No. 528/2012 - BPR) both banned substances with endocrine disrupting properties and established that EDCs should be regulated on the basis of hazard and without a specific risk assessment, in addition to providing scientific criteria to identify endocrine disrupters.

EDCs are considered to be of similar regulatory concern as substances of very high concern in the REACH regulation (No. 1907/2006), which should be regulated on a specific case, case-by-case basis.

Other relevant EU legislation on EDCs includes the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC), Regulation 1272/2008 on the classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, the Toy Safety Directive (2009/48/EC) and the Cosmetics Regulation 1223/2009.

The European Commission Directive 2011/8/EU banned, on the basis of the precautionary principle, the production and sale of baby bottles and food-related products for children containing BPA (for more detailed information on European laws and regulations, readers are referred to the EUR-Lex (https://eur-lex.europa.eu)). BPA has been restricted since 2011, in the European Union, United States and other countries, because of its endocrine disrupting properties. As a consequence of these bans, the total exposure to BPA has effectively decreased, and BPA levels in the population of children showed a marked decrease from 2000 to 2008. 47

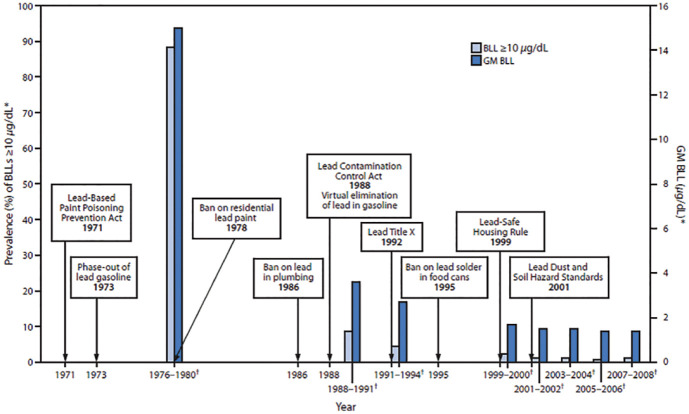

In Figure 6, the lead blood levels in young children are shown and are linked to the timeline of policies on lead poisoning prevention in United States. Before the implementation and intervention of policies, millions of children suffered from neurological effects and diminished intelligence capacity due to lead exposure from gasoline, paints and other consumer products.150,153,154 There is no threshold or safe level of lead in blood. Strong and decisive evidence revealed that the cognitive deficits and behavioural problems can occur at blood levels below 5 µL/dL.155,156 After the first policies were introduced, from 1976 to 1994, the lead blood levels dropped from 13.7 to 3.2 µL/dL and continued to decrease as policies were implemented.

Figure 6.

Timeline of lead poisoning prevention policies and blood lead levels in children aged 1–5 years, by year – National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1971–2008.150–152

Available at https://phil.cdc.gov. Accessed 19 November 2018.

The symbol ‘*’ denotes National estimates for GM BLLs and prevalence of BLLs ⩾10 µg/dL, by NHANES survey period and sample size of children aged 1–5 years: 1976–1980: N = 2372; 1988–1991: N = 2232; 1991–1994: N = 2392; 1999–2000: N = 723; 2001–2002: N = 898; 2003–2004: N = 911; 2005–2006: N = 968; 2007–2008: N = 817.

The symbol ‘†’ denotes NHANES survey period.

These, and the historical cases presented previously, indicate the limitations of science, policies and the actions of the common citizens to avoid and prevent irreversible damages but, at the same time, demonstrate that the concerted international effort, coupled with scientifically informed political decisions, can have a tremendous impact and effectiveness, through well-conceived policies and regulations, on the environment and human health.

Some recommendations to minimize exposure to EDCs

In what follows, we present a brief summary of recommendations issued by the Endocrine Society, WHO and the United Nations Environment Programme, and from experts in the field.7,157–159

It is preferable to opt for fresh food instead of processed and canned foods

Food contact materials (FCMs) are a significant source of contamination. In general, the FCMs are made of plastics that can contain additives, plasticizers and monomers that can leach and migrate to food. Several reports have been published on this subject.69,160–163 Metal cans are normally coated inside with a thin layer of epoxy resin, which is made from BPA.

It is preferable to opt for added chemicals-free food

Exposure to pesticides is linked to many diseases. Organic food may also be contaminated with pollutants because of the effects of the entire food chain and whole environment; however, this exposure is far less than conventional food. The option for organic food could be more expensive, but as the consumption increases (the organic food market is growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 14.56%, between 2017 and 2024), the prices of organic food products have tended to decrease.

Food in plastic containers should not be heated in a microwave oven. Plastic containers can be replaced by glass or ceramic ones.

The migration of the FCMs to foodstuffs can be accelerated by increasing the temperature. Some plastics, such as polycarbonate, may leach BPA. BPA analogues, such as bisphenols F and S, which were synthesized, have replaced BPA in numerous consumer products. 91 These analogues also exhibit endocrine disrupting activity, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, reproductive toxicity and neurotoxicity.91,92

The consumption of fat dairy or meat products should be reduced.

POPs bioaccumulate through the food chain, and their lipophilicity means they accumulate in fatty tissues. Bioaccumulation leads to biomagnification. POPs are absorbed by lower trophic organisms, such as phytoplankton, that are consumed by zooplankton and then by fish. They accumulate in fatty tissues of the organisms that are eaten by other organisms, thus magnifying their effect up the food chain. This concentration effect reaches maximum levels in top predator species, such as humans and other mammals.

Products such as makeup, perfume and skin care should be free of phthalates, parabens, triclosan and other chemicals.

Products with fragrances generally contain phthalates as carriers. Products that are labelled ‘antibacterial’ generally contain triclosan. Information about ingredients of cosmetics can be found in databases such as the EWG’s Skin Deep Cosmetics Database.

It is preferable to opt for ecological household cleaning products

Human exposure to BPA, phthalates and triclosan occurs, besides food, water and consumer products, through households cleaning products. The use of household cleaning products during pregnancy, at least once per week, was associated with 10%–44% greater levels of phthalate metabolites in urine. 164

Flame retardant treated furniture should be avoided

PBDEs are widely used as brominated flame retardants in furniture. These have been gradually phased-out worldwide since 2004; however, biomonitoring studies indicate that they are still ubiquitous in human blood and breast milk worlwide. 77 A number of older products contain significant amounts of these pollutants that are still being released into the surroundings environment. PBDEs have been found in human breast milk and in infants and toddlers, probably as a result of contamination by house dust.

Indoors environments should be ventilated regularly

It is estimated that the major source of contamination comes from indoor environments, since we spend about 90% of our life in enclosed spaces, particularly home and workplace, and also the car. Therefore, the IAQ has a considerable impact on our exposure to contaminants and poses a risk to human health.138,139,142,143

Alternatives to plastic toys are preferred

Children toys and teething items are generally made of plastics that contain additives which are intended to modify the properties of the polymer. The most common additives or plasticizers, added to increase flexibility, durability and so on, have been phthalate esters. Children’s normal behaviour, such as hand-to mouth and object-to-mouth contacts, increases the exposure through inhalation and ingestion routes. Phthalates have been implicated in various male malformations. Reports on the effects of prenatal exposure to phthalates in humans showed that birth outcomes were associated with high levels of phthalate esters in the urine of the mothers during pregnancy.102,103 Although EU has imposed a limit of 0.1% (W/W) of phthalates in toys, these have been found in much higher concentrations (from 0.1% to 63.34%). 165

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The exposure to EDCs begins before we are born, and even before conception. The extent of our chemical burden is unknown; every year, hundreds of new chemicals are produced and released onto the market without being tested, and reach our bodies through everyday products. The omnipresence of this exposure may have affected us all; we are not the same today as we were three centuries ago, before the invention of synthetic chemicals. We have opened Pandora’s box, and because of the overwhelming consequences of our actions, may be destroying our planet and our future. But the situation is not hopeless. A shift in lifestyles and consumption patterns is needed. We want to live our lives in the comfort that the modern age has brought to us, but we can aim for a more sustainable and ‘green’ future. One that provides health and wellbeing and preserves the only home we have, Earth. By changing habits of consumption, we influence commerce, industry and national and international policies. In this context, it is noteworthy that there are some significant shifts in policies and citizen’s thinking and choices that may have, if the trend persists, an important impact on our planet. This proenvironmental behaviour has increased considerably in recent years; the global organic food and beverages industry has grown at a compound annual growth rate around 14.56% between 2017 and 2024. 166 The worldwide number of electric vehicles increased from 2012 to 2017 from 110 thousands to 1.9 million. 167 The global renewable power capacity has grown from around 850 GW in 2000, to 1829 GW in 2014, 168 just to mention a few examples. International politics must also be influenced. However, this it is not a trivial process, since each country has different declared and other interests. For example, countries which have significant heavy chemicals industry are more hostile to changes towards a greener chemicals production. Hope also lies in the cooperation between countries, such as the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions. These have raised awareness of the problem and have led to worldwide efforts to enforce laws and regulations to protect the planet, and to protect us. There is, therefore, some hope that it might be possible to see all countries in the world working together on a solution to this global problem.

Author biographies

Telma Encarnação holds a Master’s degree in Chemistry (2009) and a First Degree in Industrial Chemistry (2007), both from the University of Coimbra. She is finishing her PhD on novel value added fine chemicals using microalgal biomass and isotopic labelling. Her research focuses on bioremediation using algae and in the sustainable transformation of emerging pollutants for producing bio-based products.

Alberto ACC Pais received his PhD in Chemistry in 1993 and is currently Full Professor at the Department of Chemistry of the University of Coimbra. His research focuses on Molecular Simulation, Chemometrics and Pharmaceutics. He was a guest editor for Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, Pharmaceutics, and co-editor of the book ‘Simvastin delivery: challenges and opportunities’. He is member of the section board for ‘Materials Science’ of the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. He is co-author of ca. 170 ISI articles, a book and several book chapters, ranging from molecular physics to food safety.

Maria G Campos completed her PhD in 1997 from Coimbra University Portugal followed this with postdoctoral studies in 2000 at Industrial Research, Ltd, Lower Hutt, New Zealand. She is Auxiliary Professor in the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Coimbra, Director of Observatory of Herbal-Drug Interactions, Head of the project IciPlant at the Oncological Hospital of Coimbra, and team leader of the International Bee pollen Working Group at IHC. She is co-author of 3 books, 16 book chapters and 94 scientific papers. She is also a member of the editorial board member of six scientific journals.

Hugh D Burrows is Professor in the Department of Chemistry, University of Coimbra, Portugal. He is a native of England and did his first degree (University of London) and PhD (University of Sussex) there. He has since worked in Universities in the United Kingdom (Warwick), Israel (Tel-Aviv), Nigeria (Obafemi Awolowo) and Portugal (Coimbra). He has been in Portugal for over 35 years, and his research has concentrated on various aspects of materials chemistry, polymers and photochemistry. Much of his current interests concentrate on interactions between light and molecules, particularly photophysical and aggregation behaviour of conjugated materials for applications in sensing, nanostructuring, illumination and artificial photosynthesis. He is Sócio Correspondente of the Academia de Ciências de Lisboa and Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry. He is author/co-author of 7 books, 14 book chapters, around 400 scientific articles and 2 Portuguese and 1 European patents. He is also the Scientific Editor of the IUPAC journal Pure and Applied Chemistry.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The authors acknowledge Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology, for the PhD research grants to SFRH/BD/81385/2011. The authors are also grateful for support from the Coimbra Chemistry Centre, which is funded by the FCT, through the projects PEst-OE/QUI/UI0313/2014 and POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007630.

References

- 1. United Nations. The 2017 Revision of World Population Prospects, 2017, https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/wpp2017_keyfindings.pdf

- 2. Eurostat. Chemicals production and consumption statistics, 2016. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Chemicals_production_and_consumption_statistics [Google Scholar]

- 3. OECD. European workshop on the impact of endocrine disrupters on human health and wildlife – report of proceedings, 1996, http://www.iehconsulting.co.uk/IEH_Consulting/IEHCPubs/EndocrineDisrupters/WEYBRIDGE.pdf

- 4. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/endocrine/documents/reports_conclusions_en.htm (accessed 24 November 2018).

- 5. Damstra T, Barlow S, Bergman A, et al. Global assessment of the state-of-the-science of endocrine disrupters. Geneva: International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS), World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev 2009; 30: 293–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bergman Å, Heindel J, Jobling S, et al. The state of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals. United Nations Environment Programme, World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Union (EU). Regulation (EU) Nº 528/2012-Biocidal products – action for failure to act – specification of the scientific criteria for the determination of endocrine-disrupting properties – failure by the Commission to adopt delegate acts – duty to act). Judgment of the General Court-Sweden v Commission Case T-521/14 (16 December 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9. European Parliament. Setting criteria on endocrine disrupters – follow-up to the General Court judgment. Belgium: European Parliament, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeung BH, Wan HT, Law AY, et al. Endocrine disrupting chemicals: multiple effects on testicular signaling and spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis 2011; 1: 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergman A, Heindel JJ, Kasten T, et al. The impact of endocrine disruption: a consensus statement on the state of the science. Environ Health Perspect 2013; 121: A104–A106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou B, Lu Y, Hajifathalian K., et al. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 2016; 387: 1513–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]