Abstract

Objectives

Neurofilament light (NfL) chain is a marker of neuroaxonal damage in various neurological diseases. Here we quantitated NfL levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum from patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and controls, using the R-PLEX NfL assay, which employs advanced Meso Scale Discovery® (MSD) electrochemiluminescence (ECL)-based detection technology.

Methods

NfL was quantitated in samples from 116 individuals from two sites (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Mayo Clinic), consisting of patients with MS (n=71) and age- and sex-matched inflammatory neurological controls (n=13) and non-inflammatory controls (n=32). Correlation of NfL levels between CSF and serum was assessed in paired samples in a subset of MS patients and controls (n=61). Additionally, we assessed the correlation between NfL levels obtained with MSD’s R-PLEX® and Quanterix’s single molecule array (Simoa®) assays in CSF and serum (n=32).

Results

Using the R-PLEX, NfL was quantitated in 99% of the samples tested, and showed a broad range in the CSF (82–500,000 ng/L) and serum (8.84–2,014 ng/L). Nf-L levels in both biofluids correlated strongly (r=0.81, p<0.0001). Lastly, Nf-L measured by MSD’s R-PLEX and Quanterix’s Simoa assays were highly correlated for both biofluids (CSF: r=0.94, p<0.0001; serum: r=0.95, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

We show that MSD’s R-PLEX NfL assay can reliably quantitate levels of NfL in the CSF and serum from patients with MS and controls, where levels correlate strongly with Simoa.

Keywords: cerebrospinal fluid, electrochemiluminescence, multiple sclerosis, neurofilament light, R-PLEX, serum, Simoa

Introduction

Neurofilament light (NfL) chain is the most abundant of the neuroaxonal intermediate filaments conferring structural stability, maintaining axon caliber and facilitating axonal growth [1]. NfL released from axons can be detected in blood. Normally, these levels are low, although they increase in an age-dependent fashion [2]. However, upon axonal damage of any cause, circulating levels of NfL increase significantly, thus rendering the protein a useful marker for axonal loss in several neurological diseases [1].

In patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), NfL levels are elevated in both blood [3] and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [4] compared to healthy controls, and they further increase during inflammatory disease states, such as in relapse [5] or around the time of new lesion development [6]. Serum NfL levels increase six years prior to the onset of clinical MS [7], and high levels of NfL are predictive of poorer clinical outcomes throughout the disease course (reviewed in Ref. [8]). Furthermore, studies have shown that NfL levels decrease following effective treatment with disease-modifying therapies [9]. Taken together, NfL levels in blood or CSF can be used for disease prognostication, as well as to monitor disease activity, and assess treatment response in MS.

While serum and CSF NfL levels correlate strongly, the NfL concentration in serum is typically orders of magnitude lower than its CSF counterpart. Thus, the development of highly sensitive quantitative technologies has enabled the reliable quantitation of NfL in serum, which is considered more advantageous over the CSF, due to minimal invasiveness of serum sampling. This is especially important in chronic neurological conditions such as MS, where longitudinal monitoring over the course of the disease is necessary.

In this study, we quantitated serum and CSF NfL in patients with MS and controls using the MSD® R-PLEX NfL assay, which employs sensitive electrochemiluminescence (ECL)-based detection technology. This technology uses SULFO-TAG™ ECL labels that emit light upon electrochemical stimulation initiated at electrode surfaces of microplates. The technology has high signal-to-background ratios due to minimal non-specific background and strong response to analytes, altogether resulting in high sensitivity and specificity. These qualities, coupled with rapid and multiplex capabilities make the R-PLEX assay ideal for clinical utility, where quality and efficiency are paramount.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

This is a retrospective study using previously collected de-identified serum and CSF samples. For each sample matrix we tested samples from 116 individuals: 71 patients with MS, 32 non-inflammatory neurological controls and 13 inflammatory neurological controls. Of the samples tested, 61 were from matched serum/CSF sets collected from the same individuals. Patient data included pertinent demographic details (age and sex), as well as clinical details at the time of sampling including Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and disease subtype (clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting MS, primary progressive MS, secondary progressive MS).

NfL quantitation

NfL was quantitated in 116 CSF and 62 serum samples (MS, inflammatory and non-inflammatory controls) using MSD’s R-PLEX Human Neurofilament L assay (Catalog # K1517XR-2, Meso Scale Discovery). All samples were stored at −80 °C, and aliquots were thawed once upon quantitation. Samples were visually inspected prior to analysis, and there were not any hemolyzed serum or blood-contaminated CSF samples. CSF samples were diluted 10-fold, serum samples 2-fold, and all samples were run in duplicates. The volume of original sample used was 5 μL of CSF and 25 μL of serum per replicate. The calibration curve was constructed using 8 calibrators with concentrations ranging from 0 to 50,000 ng/L. Signal from calibrators was fit to a 1/Y2-weighted four-parameter logistic (4PL) curve, which was then used for calculation of NfL concentration in samples.

For a subset of the matched CSF and serum samples from patients with MS (n=32), levels of NfL were available from previous measurements using the Quanterix’s Simoa® NfLightTM Advantage Kit (Qanterix), run as a batched assay and as per manufacturer’s instructions. Such levels were correlated to levels obtained using MSD’s R-PLEX NfL assay, to test whether there is a correlation between the NfL concentrations acquired with the two assays.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad 9 (Prism) was used for data analysis and visualization. NfL levels were log-transformed for all statistical analyses. Correlation analyses were performed using Pearson’s correlation. Group comparisons (MS vs. controls) were conducted using Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn’s multiple pairwise post-hoc tests between MS and control groups. Patient clinical and demographic data were analyzed as follows: Age was compared using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s pairwise post-hoc comparisons, and sex was compared using a Chi-square test.

For all analyses, two-tailed p-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographic and clinical information

The demographic and clinical information of the study subjects is shown in Table 1. Overall, there was no significant difference in age or sex distribution between patients with MS and controls. In the MS group, the female to male ratio was 3:1, the median EDSS score at sampling was 1.5. Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) (52.1%) was the leading type of MS, followed by primary progressive MS (PPMS) (36.7%).

Table 1:

Study participant clinical and demographic information.

| MS | Inflammatory control | Non-inflammatory control | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group size (subjects) | 71 | 13 | 32 | 116 | |

| Samples | CSF=71 | CSF=13 | CSF=32 | CSF=116 | |

| Serum=34 | Serum=10 | Serum=18 | Serum=62 | ||

| Matched=33 | Matched=10 | Matched=18 | Matched=61 | ||

| Age, years (mean ± StDev) | 43.75 ± 15.39 | 36.62 ± 14.59 | 38.75 ± 10.58 | 0.1017 | |

| Sex | 74% Female 26% Male |

46% Female 46% Male 8% Missing |

69% Female 26% Male 3% Missing |

0.2022 | |

| EDSS score at sampling, median (IQR) | 1.5 (2) | ||||

| MS type at sampling, % (n) | |||||

| RRMS | 52.1% (37) | ||||

| PPMS | 36.7% (26) | ||||

| CIS | 9.9% (7) | ||||

| PRMS | 1.4% (1) | ||||

StDev, standard deviation; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; IQR, interquartile interval; MS, multiple sclerosis; n, number of subjects; RRMS, relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; PPMS, primary-progressive multiple sclerosis; CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; PRMS, progressive-relapsing multiple sclerosis.

Neurological inflammatory controls consisted of 4 patients with neuroosarcoidosis, 4 patients with acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, 2 patients with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, 1 patient with neuromyelitis optica, 1 patient with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and 1 patient with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis neuropathy.

Non-inflammatory controls included patients evaluated for possible MS but subsequently diagnosed with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, anxiety, or migraine.

Analytical sensitivity and NfL concentration in study subjects

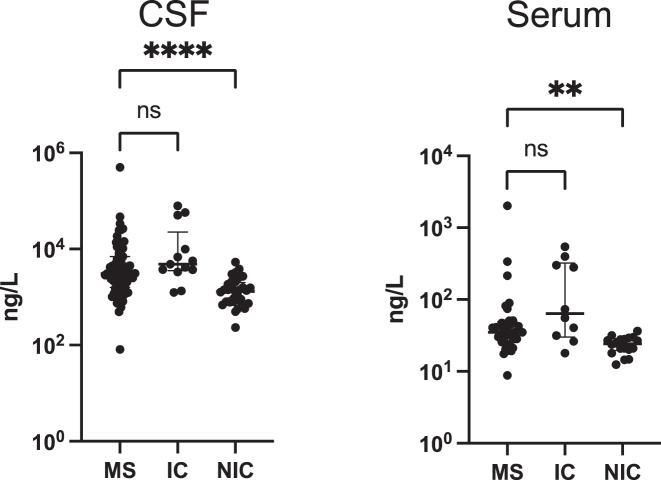

The NfL concentrations detected in the current samples ranged broadly, with sample concentration spanning over 3 logs range in serum (8.84–2,014 ng/L) and 5 logs range in the CSF (82–500,000 ng/L). Ninety-nine percent (99%) of samples were above the lower limit of detection (LLOD). Overall, NfL levels were significantly different between the three groups of the study [Kruskal–Wallis: p<0.0001 (CSF), p=0.0003 (serum)]. Pairwise analyses between the MS group and the control groups, showed that NfL concentration in patients with MS was significantly higher than in non-inflammatory controls (Dunn’s test: p<0.0001 (CSF), p=0.0026 (serum)], but similar to levels in inflammatory controls [Dunn’s test: p=0.155 (CSF); p=0.351 (serum)] (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Quantitation of CSF(c) and serum(s) NfL in all study subjects measured with MSD’s ECL technology. Graphs demonstrate higher levels of cNfL and sNfL in MS patients compared to non-inflammatory controls (NIC), but similar levels to inflammatory controls (IC). Asterisks indicate significance from pairwise post-hoc comparisons between MS and control groups, following a Kruskal–Wallis test. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Bars show median with interquartile range on concentration values (ng/L). CSF sample size: n=71 MS; 32 NIC; 13 IC. Serum sample size: n=33 MS; 18 NIC; 10 IC. ns, non-significant.

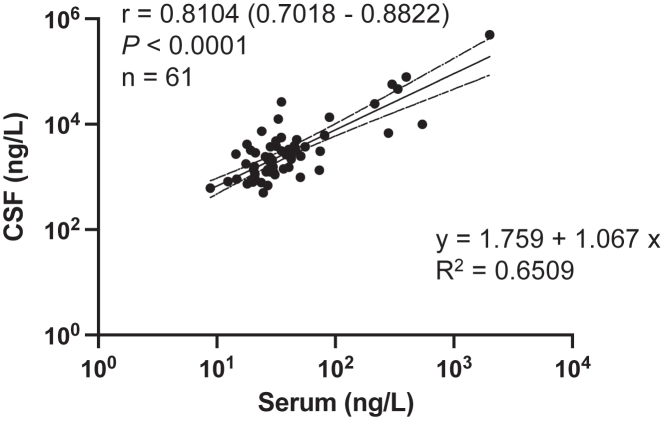

Correlation between serum and CSF NfL levels

We found a strong correlation of CSF and serum NfL levels in paired samples from 61 subjects (MS, inflammatory controls, non-inflammatory controls); Pearson’s correlation coefficient r=0.8104 (95% confidence interval: 0.7018–0.8822), p<0.0001 (Figure 2). The best-fitting line that represents the relationship between serum and CSF levels of NfL was also calculated with an adjusted R2=0.6509, indicating a good fit.

Figure 2:

Strong and significant correlation of serum and CSF NfL as measured with MSD’s ECL technology. Number of subjects is indicated by n [n=33 (MS); 10 (inflammatory control); 18 (non-inflammatory control)] and r is the Pearson correlation coefficient (with 95% confidence interval) on log-transformed concentration data. The equation that best represents the linear relationship of NfL measurements between serum and CSF is shown along with adjusted R2 values representing the goodness of fit.

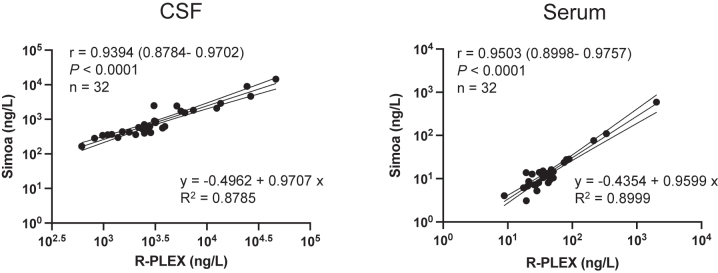

Correlation between MSD and Quanterix NfL levels

We found a very strong positive correlation between MSD R-PLEX and Quanterix Simoa assay measurements of NfL levels in the CSF [r=0.9394 (95% confidence interval: 0.8784–0.9702), p<0.001] and serum [r=0.9503 (95% confidence interval: 0.8998–0.9757), p<0.001] from patients with MS (Figure 3). MSD R-PLEX assay values were higher than the Quanterix Simoa values by 3 times for serum and 4 times in CSF, on average. Additionally, we report the equation of the best fitting line that represents the relationship for NfL levels between the two technologies in either biological fluid (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Correlation between MSD’s R-PLEX and Quanterix’s Simoa-quantitated levels of CSF and serum NfL levels. Levels of NfL as measured by MSD R-PLEX assay correlate strongly with levels measured by Quanterix’s Simoa assay in CSF and serum. Number of samples from patients with MS and r is the Pearson correlation coefficient (with 95% confidence interval) on log-transformed concentration data is indicated by n. The equation that best represents (fits) the linear relationship of NfL measurements between two technologies in each biological matrix is shown along with adjusted R2 values representing the goodness of fit.

Discussion

In this study we show the analytical performance of MSD’s R-PLEX Nf-L assay, which employs sensitive ECL detection, for the quantitation of Nf-L protein in serum and CSF from patients with MS and controls. Importantly, we show that the levels of CSF and serum NfL as measured by MSD’s R-PLEX technology correlate strongly with Quanterix’s Simoa platform. We additionally show that levels are elevated in the particular cohort of patients with MS compared to non-inflammatory controls, and that levels in serum, and CSF are correlated.

Simoa has emerged as the benchmark of blood neurofilament quantification, and involves an ultrasensitive digital immunoassay to detect analytes at femtogram/mL concentrations [10]. However, cost is an important consideration and barrier to translation, highlighting the need for competition and spurning the development of other assays that can provide similar levels of detection [8]. The R-PLEX technology employed here presents with multiple analytical and technical advantages including broad dynamic range, high signal-to-background ratios, small sample volume requirement, multiplex automated capability and minimal matrix interference. The MSD’s NfL assay tested here can detect NfL at concentrations between 7.5 ng/L (lower limit of quantification; LLOQ) – 50,000 ng/L (calibrator standard 1, top of curve) [11]. The assay’s lower limit of detection (LLOD) is 5.5 ng/L [11]. Here the sample concentrations ranged between 8.84 ng/L (lowest value obtained in a serum sample) – 500,000 ng/L (highest value obtained in a CSF sample). Notably, this assay presents an improvement over an earlier generation assay developed on the MSD platform for the detection of NfL, which used different antibodies and had lower analytical sensitivity (15.6 ng/L), as well as a narrower dynamic range (0–1,000 ng/L) [12, 13]. Absolute NfL concentrations acquired using MSD’s R-PLEX were on average 3–4 times higher than the levels quantitated using Simoa, likely due to the differences in the antibodies and calibrators used in these assays. This result emphasizes the importance for establishing inter-platform equivalence standards, especially as more methods for NfL detection emerge [8].

We found that the levels of NfL were significantly higher in patients with MS in this study group, when compared to non-inflammatory controls but were similar to inflammatory controls. The latter result further confirms the established view in the field that NfL is not a useful diagnostic marker for MS, rather it can be used for disease prognostication and monitoring.

Using this assay, we additionally show that NfL levels in serum and CSF correlate significantly, corroborating previous studies [14], and further supporting serum is a sufficient surrogate for CSF NfL levels in MS [13].

One important limitation of the study is the relatively small sample size. Future work will further characterize the inter-/intra-assay performance of the platform and the potential effect of interfering matrices in serum, as previously reported by other platforms [15]. Moreover, while NfL has been shown to be relatively stable upon delayed freezing and repeated thawing conditions, detailed stability tests using the MSD platform are warranted [16].

In conclusion, here we show the application of MSD’s R-PLEX NfL assay in quantitating NfL levels in serum and CSF from patients with MS and controls. We report the analytical sensitivity and dynamic range of the assay, and we show high correlation between NfL concentrations obtained using MSD’s R-PLEX and Quanterix’s Simoa NfL assays.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ulndreaj is supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from the University of Toronto’s Medicine by Design initiative, which receives funding from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF).

Footnotes

Research funding: The development of the MSD assays was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U24AI118660. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Funding for the Quanterix assays was provided by the Ottawa Hospital Innovation Grant.

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Competing interests: Some authors (CC, MS, GS, DC) are employees of MSD. Dr. Eleftherios P. Diamandis declares that he holds an advisory role with Abbott Diagnostics and a consultant role with Imaware Diagnostics. All other authors have nothing to declare.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

Ethical approval: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013) and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Boards (Mount Sinai Hospital, The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and Mayo Clinic).

Contributor Information

Ioannis Prassas, Email: yprassas@gmail.com.

Eleftherios P. Diamandis, Email: Eleftherios.Diamandis@sinaihealth.ca.

References

- 1.Gaetani L, Blennow K, Calabresi P, Filippo MD, Parnetti L, Zetterberg H. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90:870–81. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalil M, Pirpamer L, Hofer E, Voortman MM, Barro C, Leppert D, et al. Serum neurofilament light levels in normal aging and their association with morphologic brain changes. Nat Commun. 2020;11:812. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14612-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhle J, Kropshofer H, Haering DA, Kundu U, Meinert R, Barro C, et al. Blood neurofilament light chain as a biomarker of MS disease activity and treatment response. Neurology. 2019;92:e1007–15. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000007032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eikelenboom MJ, Petzold A, Lazeron RHC, Silber E, Sharief M, Thompson EJ, et al. Multiple sclerosis: neurofilament light chain antibodies are correlated to cerebral atrophy. Neurology. 2003;60:219–23. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000041496.58127.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akgün K, Kretschmann N, Haase R, Proschmann U, Kitzler HH, Reichmann H, et al. Profiling individual clinical responses by high-frequency serum neurofilament assessment in MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2019;8:e555. doi: 10.1212/nxi.0000000000000555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosso M, Gonzalez CT, Healy BC, Saxena S, Paul A, Bjornevik K, et al. Temporal association of sNfL and gad-enhancing lesions in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7:945–55. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjornevik K, Munger KL, Cortese M, Barro C, Healy BC, Niebuhr DW, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain levels in patients with presymptomatic multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:58–64. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thebault S, Booth RA, Rush CA, MacLean H, Freedman MS. Serum neurofilament light chain measurement in MS: hurdles to clinical translation. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:654942. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.654942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delcoigne B, Manouchehrinia A, Barro C, Benkert P, Michalak Z, Kappos L, et al. Blood neurofilament light levels segregate treatment effects in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2020;94:e1201–12. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quanterix . Simoa® technology [Internet] 2022. [20 Jun 2022]. https://www.quanterix.com/simoa-technology/ Available from: Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 11.R-PLEX human neurofilament light datasheet [Internet] 2022. [20 Jun 2022]. https://www.mesoscale.com/∼/media/files/data%20sheets/ds-r-plex-human-neurofilament-l.pdf Available from: Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaiottino J, Norgren N, Dobson R, Topping J, Nissim A, Malaspina A, et al. Increased neurofilament light chain blood levels in neurodegenerative neurological diseases. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhle J, Barro C, Andreasson U, Derfuss T, Lindberg R, Sandelius Å, et al. Comparison of three analytical platforms for quantification of the neurofilament light chain in blood samples: ELISA, electrochemiluminescence immunoassay and Simoa. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54:1655–61. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhle J, Barro C, Disanto G, Mathias A, Soneson C, Bonnier G, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain in early relapsing remitting MS is increased and correlates with CSF levels and with MRI measures of disease severity. Mult Scler Houndmills Basingstoke Engl. 2016;22:1550–9. doi: 10.1177/1352458515623365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Plavina T, Singh CM, Xiong K, Qiu X, Rudick RA, et al. Development of a highly sensitive neurofilament light chain assay on an automated immunoassay platform. Front Neurol. 2022;13:935382. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.935382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altmann P, Leutmezer F, Zach H, Wurm R, Stattmann M, Ponleitner M, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain withstands delayed freezing and repeated thawing. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19982. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77098-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]