Abstract

The rat cytomegalovirus (RCMV) R78 gene belongs to an uncharacterized class of viral G protein-coupled receptor (GCR) genes. The predicted amino acid sequence of the R78 open reading frame (ORF) shows 25 and 20% similarity with the gene products of murine cytomegalovirus M78 and human cytomegalovirus UL78, respectively. The R78 gene is transcribed throughout the early and late phases of infection in rat embryo fibroblasts (REF) in vitro. Transcription of R78 was found to result in three different mRNAs: (i) a 1.8-kb mRNA containing the R78 sequence, (ii) a 3.7-kb mRNA containing both R77 and R78 sequences, and (iii) a 5.7-kb mRNA containing at least ORF R77 and ORF R78 sequences. To investigate the function of the R78 gene, we generated two different recombinant virus strains: an RCMV R78 null mutant (RCMVΔR78a) and an RCMV mutant encoding a GCR from which the putative intracellular C terminus has been deleted (RCMVΔR78c). These recombinant viruses replicated with a 10- to 100-fold-lower efficiency than wild-type (wt) virus in vitro. Interestingly, unlike wt virus-infected REF, REF infected with the recombinants develop a syncytium-like appearance. A striking difference between wt and recombinant viruses was also seen in vivo: a considerably higher survival was seen among recombinant virus-infected rats than among RCMV-infected rats. We conclude that the RCMV R78 gene encodes a novel GCR-like polypeptide that plays an important role in both RCMV replication in vitro and the pathogenesis of viral infection in vivo.

G protein-coupled receptors (GCRs) play a key role in transduction of extracellular signals to the intracellular environment. They can be activated by a variety of stimuli, such as neurotransmitters, hormones, and photons (reviewed by Probst et al. [53]). Upon ligand binding, GCRs activate G proteins, which in turn activate effector enzymes and ion channels in a cascade-like fashion. Thousands of GCR variants are encoded by genes of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Additionally, some are encoded by virus genes. To date, 20 putative viral GCR genes have been discovered: 2 in poxvirus genomes (21, 44), 11 in betaherpesvirus genomes (9, 22, 33, 49, 54), and 7 in gammaherpesvirus genomes (4, 26, 48, 57, 63). The majority of these genes was found to be similar to genes encoding cellular chemokine receptors. Although the functions of most of the putative viral GCRs are unclear, several are capable of binding chemokines, hence invoking a classical signal transduction response (1, 4, 31, 38, 42, 47). The herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) ECRF3-encoded chemokine receptor is capable of transducing signals upon activation by α chemokines (1). The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) US28-encoded chemokine receptor was shown to be a promiscuous calcium-mobilizing receptor for several β chemokines (31). Additionally, the US28 protein was suggested to be responsible for β-chemokine sequestration in HCMV-infected fibroblasts (15). The GCR encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) open reading frame (ORF) 74 not only binds both α and β chemokines but also is constitutively active, inducing second-messenger signalling in vitro (4). The KSHV chemokine receptor was also shown to stimulate cellular proliferation (4), transformation, and angiogenesis (7). A distinctive set of chemokine-like receptors is exclusively encoded by betaherpesviruses: HCMV UL33 (23), rat cytomegalovirus (RCMV) R33 (9), murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) M33 (54), and human herpesvirus 6 and 7 (HHV-6 and -7) U12 (33, 49). Recently, we found that the RCMV R33 gene is essential for the pathogenesis of viral infection in vivo and that unlike wild-type (wt) virus, an RCMV R33 null mutant could neither enter nor replicate in salivary gland epithelial cells of infected rats (9). A similar observation was made for MCMV M33: upon infection of mice with an MCMV M33 deletion mutant strain, virus could not be recovered from mouse salivary glands (26). Interestingly, betaherpesviruses encode another distinctive set of yet uncharacterized viral GCRs: HCMV UL78 (22), MCMV M78 (54), and HHV-6 and -7 U51 (33, 49). Although the positions of these UL78-like genes within the betaherpesvirus genomes are conserved, their sequences are rather divergent. Despite the presence of distinct GCR characteristics, such as seven transmembrane domains, two conserved cysteine residues, and a G protein-coupling domain (53), these UL78-like gene products show little similarity with any of the thousands of GCRs known to date. Nevertheless, characterization of this unique family of GCRs may be crucial to the development of new antiviral therapeutics. In this report, we present the sequence and transcriptional analysis of the RCMV member of this family of GCR genes, which we termed R78. In addition, RCMV strains were generated in which the R78 (ORF) is either partially or completely deleted from the genome (RCMVΔR78a or RCMVΔR78c, respectively). We show that disruption of the R78 gene affects RCMV replication in permissive cell types in vitro and that the RCMV R78 deletion mutant strains induce syncytium formation in rat embryo fibroblasts (REF) in vitro, in contrast to wt RCMV. In addition, a dramatically lower mortality was observed in rats infected with either RCMVΔR78a or RCMVΔR78c than in wt RCMV-infected rats. We conclude that the RCMV R78 gene plays a vital role in both RCMV replication in vitro and the pathogenesis of viral infection in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Primary REF, rat fibroblast cell line Rat2 TK− (ATCC CRL 1764), rat heart endothelium cell line 116 (RHEC), monocyte/macrophage cell line R2 (R2Mφ), and rat aorta medial smooth muscle cells (RSMC) were cultured as described previously (18, 24, 50, 60). RCMV (Maastricht strain) was propagated in REF (18). Virus titers were determined by a plaque assay using standard procedures (19). RCMV DNA was isolated from culture medium as described by Vink et al. (61).

Identification, cloning, and sequence analysis of the RCMV R78 gene.

Cloning of the 30-kb XbaI B fragment of the RCMV genome into vector pSP62-PL has previously been described (45). The XbaI B fragment was digested with various restriction endonucleases, and the resulting fragments were cloned into vector pUC119. Both strands of each clone were sequenced by using the Cy5 Autoread sequencing kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Roosendaal, The Netherlands) and ALFexpress automated DNA sequencer (Pharmacia Biotech). Sequence analysis was done with the program PC/Gene (version 2.11; IntelliGenetics). The sequences were checked for the presence of HCMV UL78-homologous regions by alignment with the GenBank nucleic acid database, using the BLASTN search algorithm (39). Thus, a 3.7-kb BamHI fragment was identified, which contains an ORF with considerable similarity to the HCMV UL78 ORF.

RCMVΔR78a recombination plasmid construction.

Plasmid p115, which contains a large part of the R78 ORF on a 2.4-kb SalI fragment (Fig. 1), was digested with SalI and subsequently treated with deoxynucleotide triphosphates and DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment (Pharmacia Biotech). Subsequently, the DNA was digested with BglII, and the resulting 1.4-kb fragment was cloned into BamHI-SmaI-treated vector pUC119, generating plasmid pA. Plasmid p114, which contains the remaining part of the R78 ORF on a 1.7-kb SalI fragment (Fig. 1), was digested with SalI. The 1.7-kb SalI insert from p114 was ligated into the SalI site of pA, generating pB. A 1.5-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment from Rc/CMV (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands), containing the neomycin resistance (neo) gene, was treated with Klenow enzyme and ligated into a XbaI-digested and Klenow enzyme-treated vector pB. This final construct (p147 [see Fig. 4]) was linearized by digestion with Asp718I and HindIII and used for transfection, in order to generate mutant RCMVΔR78a.

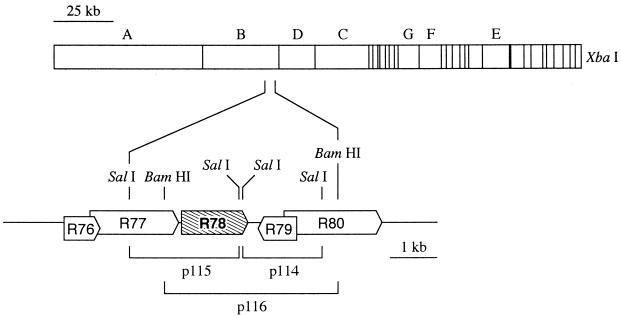

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the RCMV genome and relative position of the R78 gene, which encodes a putative GCR. An enlarged section of the map is shown below. Arrow boxes indicate the size and polarity of conserved RCMV ORFs.

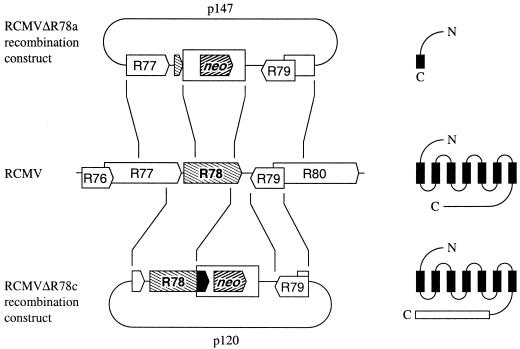

FIG. 4.

Construction of RCMV strains in which the R78 gene is disrupted. The RCMV genome, of which a segment representing the R78 region is shown in the middle, was modified by homologous recombination with different recombination plasmids (p147 [top] or p120 [bottom]), resulting in RCMVΔR78a or RCMVΔR78c, respectively. Approximately 85% of the R78 ORF has been deleted in the RCMVΔR78a genome (resulting in a gene encoding only the N-terminal part including half of the first predicted transmembrane domain, shown at the top right). In mutant RCMVΔR78c, the part of the R78 that encodes the putative intracellular C terminus has been replaced by a sequence encoding a stretch of 97 amino acids of irrelevant sequence (bottom right, indicated as a black arrow box). ORFs are shown as arrow boxes. Wild-type and mutated R78 ORFs are indicated with descending hatches. The neo genes that were inserted in the recombination plasmids are indicated with ascending hatches.

RCMVΔR78c recombination plasmid construction.

Plasmid p116, which contains the complete R78 ORF on a 3.7-kb BamHI fragment (Fig. 1), was digested with Asp718I and NcoI. The resulting 2.9-kb fragment was treated with Klenow enzyme and subsequently circularized with T4 DNA ligase, resulting in plasmid pC. One SalI site was removed from pC by digestion of the plasmid with XbaI and HindIII and subsequent treatment with Klenow enzyme. The resulting fragment was circularized, generating plasmid, pD. Plasmid pD was digested with SalI, treated with Klenow enzyme, and ligated to the blunt-ended DNA fragment containing the Rc/CMV neo gene (see above). The resulting plasmid, p120 (see Fig. 4), was linearized with Asp718I and XbaI prior to transfection, in order to generate mutant RCMVΔR78c.

Generation of RCMV R78 deletion mutants.

Approximately 107 Rat2 cells were trypsinized and subsequently centrifuged for 5 min at 500 × g. The cells were resuspended in 0.25 ml of culture medium, after which 10 μg of linearized plasmid of either p120 or p147 was added. The suspension was transferred to a 0.4-cm electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad, Veenendaal, The Netherlands) and pulsed at 0.25 kV and 500 μF in a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser electroporator. The cells were subsequently seeded in 10-cm-diameter culture dishes. At 6 h after transfection, the cells were infected with RCMV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. The culture medium was supplemented with 50 μg of G418 per ml at 16 h postinfection (p.i.). Recombinant viruses were plaque purified and cultured on REF monolayers as described earlier (9).

Southern blot hybridization.

DNA was isolated from wt RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, and RCMVΔR78c and then digested with either BamHI, BamHI-BglII, BamHI-EcoRV, BamHI-NcoI, SalI, or SalI-EcoRV. Subsequently, the digested DNA was electrophoresed through a 1% agarose gel and blotted onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, ’s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands) as described previously (16). Both a 3.7-kb insert from p116 containing the intact R78 ORF as well as sequences from R77 and R79 (R78 probe [see Fig. 5A]), along with a 1.5-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment containing the neo gene (neo probe) from Rc/CMV, were used as probes. Hybridization and detection experiments were performed with digoxigenin DNA labeling and chemiluminescence detection kits (Boehringer Mannheim, Almere, The Netherlands).

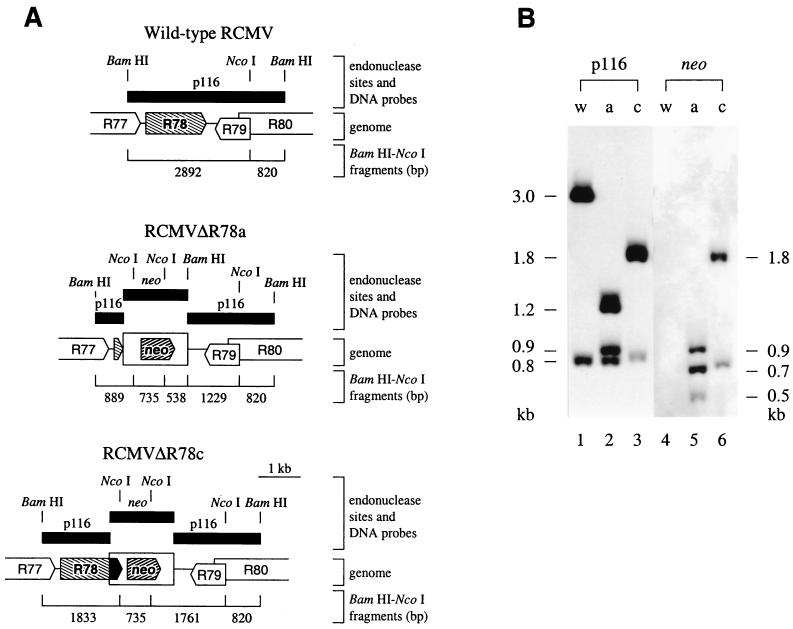

FIG. 5.

Southern blot analysis of recombinant viruses RCMVΔR78a and RCMVΔR78c. (A) DNA from RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, and RCMVΔR78c was digested with BamHI and NcoI, electrophoresed, blotted, and hybridized with either a probe derived from the p116 insert or a neo probe (both indicated with black boxes). ORFs are shown as arrow boxes. Wild-type and mutated R78 ORFs are indicated by descending hatches. The neo genes that were inserted in the recombination plasmids are indicated by ascending hatches. (B) Autoluminograph of a Southern blot containing wt (w) DNA, RCMVΔR78a (a) DNA, and RCMVΔR78c (c) DNA. The estimated lengths of BamHI-NcoI-digested DNA fragments are indicated at the sides in kilobases.

Isolation of poly(A)+ RNA and Northern blot analysis.

RCMV poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from REF at 2, 8, and 48 h p.i. and at immediate-early (IE), early (E), and late (L) times of infection with RCMV (MOI = 1). To obtain IE mRNA, REF were treated with 100 μg of cycloheximide per ml 1 h before, during, and 16 h after infection. During the 1-h infection period, the cells were exposed to RCMV. E mRNA was isolated after infection of REF with RCMV and treatment of cells with 100 μg of phosphonoacetic acid per ml from 3 h p.i. until the cells were harvested at 13 h p.i. L mRNA was isolated after infection of REF with either RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, or RCMVΔR78c and harvesting of cells at 72 h p.i. To obtain mRNA from mock-infected cells, a procedure similar to that described for the purification of L mRNA was used except that RCMV infection was omitted. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified with a QuickPrep Micro mRNA purification kit (Pharmacia Biotech). Aliquots (1 μg) of poly(A)+ RNA were electrophoresed through agarose under denaturing conditions as described by Brown and Mackey (17); then the RNA was transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim) as described previously (17). The 754-bp BamHI-SalI fragment from p115 and the 950-bp BglII-SalI, 206-bp BglII-NarI, and 1,088-bp BglII-SalI fragments from p116 (see Fig. 6A) were used to generate probes. These fragments contain R77-, R78-, R79-, and R79/R80-specific sequences, respectively. Hybridization and detection experiments were performed with digoxigenin DNA labeling and chemiluminescence detection kits (Boehringer Mannheim).

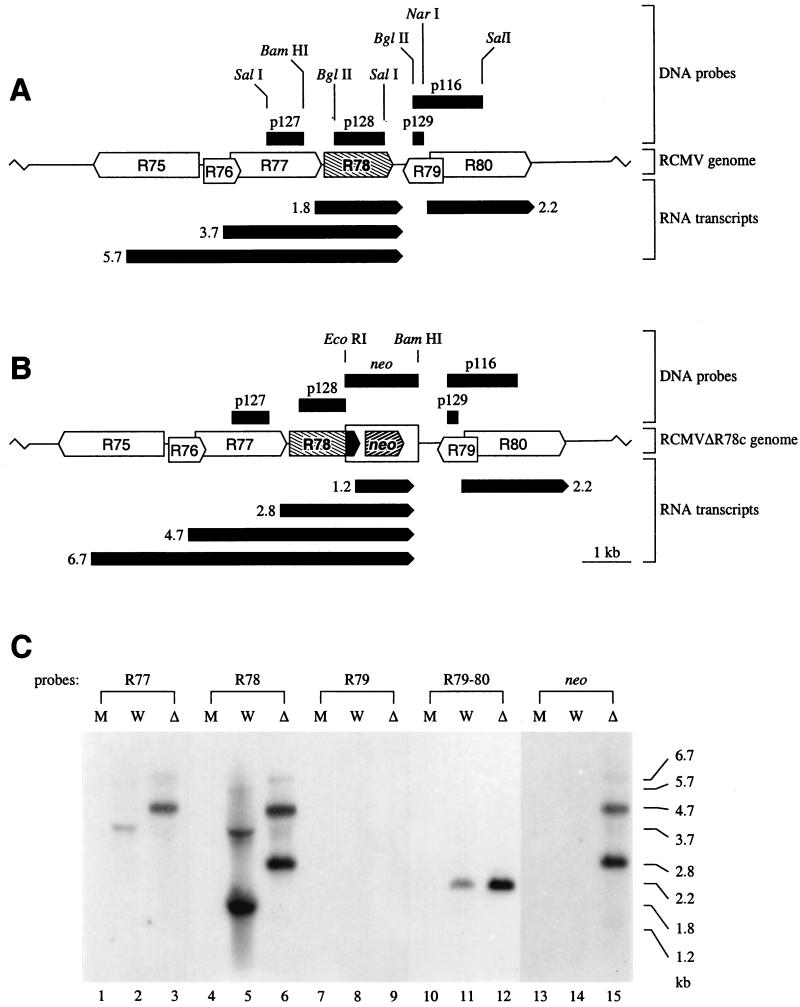

FIG. 6.

Transcription of R78 and neighboring genes. The wt RCMV (A) and RCMVΔR78c (B) genomes are represented by lines. ORFs are indicated by white, hatched, and black arrow boxes, probes are indicated by black boxes, and transcripts are indicated by black arrow boxes below the genomes. Lengths are shown at the sides in kilobases. (C) Autoluminographs from Northern blots that contain poly(A)+ RNA from virus-infected REF. The transcript lengths that correspond to the detected hybridization signals are indicated in kilobases. M, mock infected; W, wt RCMV infected; Δ, RCMVΔR78c infected.

Replication of ΔR78a and ΔR78c in vitro.

REF, RHEC, R2Mφ, and RSMC were grown either in 96-well plates or on glass slides and infected with either RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, or RCMVΔR78c at an MOI of 0.1 or 1. Culture medium samples (three per virus) were taken at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days p.i. and subjected to plaque titer determination. The cells were fixed and stained with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against RCMV E proteins (MAb RCMV 8 [20]) as described previously (60). The degree of infection was determined by counting the number of antigen-positive cells relative to the total number of cells in three different wells (four microscopic fields per well at a magnification of ×400).

Dissemination of wt RCMV and RCMVΔR78c in vivo.

Male specific-pathogen-free Lewis/N RT1 rats (Central Animal Facility, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands), used for all in vivo experiments in this study, were kept under standard conditions (55). Rats were immunocompromised by 5 Gy of total-body Röntgen irradiation 1 day before infection as described by Stals et al. (55), and all virus stocks that were used for inoculation in vivo were derived from tissue culture medium of virus-infected REF. Two groups of rats (10 weeks old; body weight of 250 to 300 g) were infected with 5 × 106 PFU of either RCMV or RCMVΔR78c. On days 4 and 21 p.i., five rats from each group were sacrificed, and their internal organs were collected. These organs were subjected to both plaque assay and immunohistochemistry (19). Tissue sections (4 μm) of the submaxillary salivary gland, spleen, kidney, liver, lung, heart, pancreas, thymus, aorta, and cervical lymph nodes were stained with MAb RCMV 8.

Survival of immunocompromised rats infected with either RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, or RCMVΔR78c.

Four-week-old rats (100 to 120 g) were divided into three groups of five rats. Intraperitoneal infection was carried out with 106 PFU of either RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, or RCMVΔR78c. The number of surviving rats was recorded daily until day 28 p.i.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the 3.7-kb BamHI fragment containing the R78 gene (Fig. 1) and the predicted amino acid sequence derived from R78 have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF077758.

RESULTS

Identification, cloning, and sequence analysis of the RCMV R78 gene.

Previously, it was shown that the majority of RCMV genes are collinear with genes of both HCMV and MCMV (9–11, 61, 62). We hypothesized that the position of a putative RCMV UL78 homolog would be analogous to that of both HCMV UL78 (22) and MCMV M78 (54). Accordingly, we focused on the 33-kb RCMV XbaI B fragment (Fig. 1) (45). This fragment was digested with various restriction endonucleases, subcloned, and sequenced. The GenBank database was subsequently screened for homology with the generated sequence. Thus, we identified (in plasmid p116) a 3.7-kb BamHI fragment showing considerable similarity to a region within the genomes of HCMV as well as MCMV, containing the UL78 and M78 genes, respectively. A 1,422-bp ORF was identified within the BamHI fragment (Fig. 1), which has the potential to encode a 474-amino-acid polypeptide with a predicted molecular mass of 50 kDa. This polypeptide shows 25 and 20% similarity with the amino acid sequences of M78 (54) and UL78 (22), respectively (Table 1). This low level of similarity is not uncommon to UL78-like sequences, since the amino acid sequences derived from UL78 and M78 share only 21% similarity (Table 1). In analogy to the nomenclature for the corresponding HCMV and MCMV genes, the 1,422-bp RCMV ORF was termed R78.

TABLE 1.

Similarities of predicted amino acid sequences among R78-like gene products

| Gene product | Similarity (%)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCMV R78 | MCMV M78 | HCMV UL78 | HHV-6 U51 | |

| MCMV M78 | 25.0 | |||

| HCMV UL78 | 20.1 | 20.8 | ||

| HHV-6 U51 | 13.9 | 14.9 | 15.4 | |

| HHV-7 U51 | 14.8 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 36.0 |

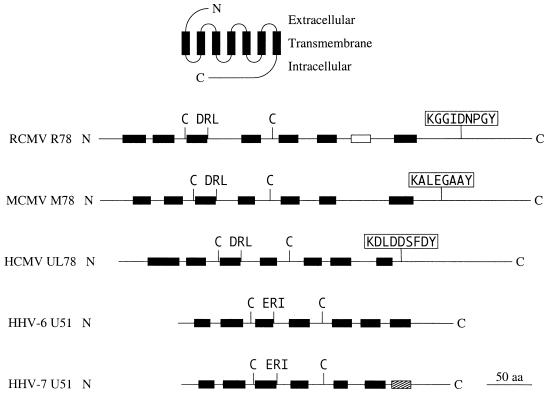

To investigate whether the amino acid sequence of the R78-derived polypeptide (pR78) possesses features that are characteristic of GCRs, the pR78 sequence was analyzed with computer program TMpred (ISREC Bioinformatics Group, Epalinges, Switzerland [58]). This program utilizes a database of existing transmembrane domains to predict potential transmembrane domains of an uncharacterized sequence. Computation revealed an extracellular N terminus and eight transmembrane domains, each of which might be folded as an α helix. Seven of these domains are collinear with the predicted transmembrane domains of the gene products of MCMV M78 and HCMV UL78 (Fig. 2). In addition, several amino acid residues that are conserved among most GCRs were identified (reviewed by Probst et al. [53]): two conserved cysteine residues at positions 94 and 190, which may form a disulfide bridge, and a conserved aspartic acid-arginine-leucine (DRL) motif (positions 118 to 120) that might be involved in G protein coupling (Fig. 2). These residues are also present within analogous regions of the UL78 and M78 gene products and the HHV-6 and -7 U51 gene products (Fig. 2). Another interesting feature is the presence of a putative tyrosine kinase phosphorylation site (phosphorylation consensus [R/K]X2/3[D/E]X2/3Y, at positions 392 to 400) (Fig. 2). These putative tyrosine phosphorylation sites are found in the predicted amino acid sequences of RCMV R78, MCMV M78, and HCMV UL78 but not in analogous regions of the predicted U51 amino acid sequence of either HHV-6 or HHV-7 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the gene products of RCMV R78, MCMV M78, HCMV UL78, and HHV-6 and -7 U51. The top drawing shows the two-dimensional orientation of GCRs (not to scale with diagrams of the other GCRs). Horizontal lines represent the one-dimensional structure of the R78-like gene products; designations of the genes that encode these receptors are shown at the left. Black boxes represent putative transmembrane α helices; the white box indicates an additional unique hydrophobic α-helix domain predicted by the computer program TMpred (58); the hatched box indicates a hydrophobic stretch of amino acid residues collinear with predicted transmembrane domains of the other GCRs, although not predicted by TMpred. Conserved cysteine residues are indicated by C’s. The (D/E)R(I/L) motifs indicate positions of the conserved putative G protein-coupling domains. The sequences enclosed in white boxes indicate positions of putative tyrosine kinase phosphorylation sites that are conserved among CMV genes relative to R78.

In order to classify the GCRs encoded by the R78-like genes, the predicted amino acid sequences of R78, M78, UL78, and HHV-6 and -7 U51 were screened against a nonredundant protein sequence data set (a combination of all nonredundant GenBank complete protein coding gene translations plus sequences from the Protein Data Bank, SwissProt, and Protein Information Resource databases [39]). This analysis demonstrated a clear relationship between pR78-like peptides and other GCRs; the predicted amino acid sequence of the UL78 gene was similar to sequences of GCRs such as a thrombin receptor (32) and opioid receptor (66), while the M78 gene product shows similarity with a lysophosphatidic acid receptor (3) and a somatostatin-like receptor (64). Surprisingly, the sequence of the C-terminal part of the R78 gene product was found to be similar to collagen-like sequences (in particular sequences such as human collagen (51) and spider silk protein (65). Although previously examined virus-encoded GCRs were shown to be related to chemokine receptors (1, 4, 9, 21, 26, 30, 38, 42, 44, 47, 57, 63), none of the pR78-like GCRs showed a collective similarity with GCRs of any particular class. Most notably, the N-terminal part of the R78-like gene products lack the signals for N-linked glycosylation, which are present in the N-terminal sequences of all other known virus-encoded GCRs, making this a unique set of receptors among virus-encoded GCRs.

R78 transcription.

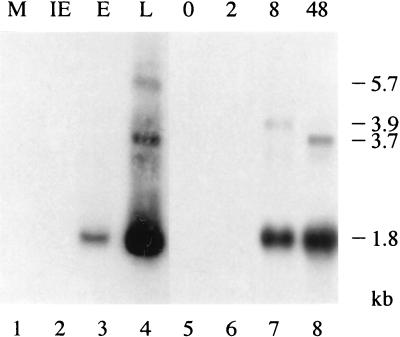

Although the ORFs of R78-like betaherpesvirus genes are poorly conserved, they are all preceded by a remarkable double TATA signal motif. Moreover, the start codons of R78, M78, and UL78 conform to the Kozak consensus (41). The positions and sequences of these motifs are summarized in Table 2. We set out to identify transcripts derived from the RCMV R78 gene by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 3, R78-specific hybridization signals were detected in phosphonoacetic acid-treated (lane 3) and untreated (lane 4) cells but not in cycloheximide-treated (lane 2) or mock-infected (lane 1) cells. In untreated, RCMV-infected REF, R78-specific signals were detected at 8 and 48 h p.i. (lanes 7 and 8, respectively) but not at earlier time points (lane 5 and 6, respectively). These results classify R78 as an E gene that is also transcribed during the L phase of infection in vitro.

TABLE 2.

Transcription initiation and translation signals of R78-like genes are conserveda

| Virus | Gene | TATA box 1

|

TATA box 2

|

Kozak

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Position | Sequence | Position | Sequence | Position | ||

| RCMV | R78 | TATTTG | −108 to −103 | TATAAG | −62 to −57 | GCCACGATGG | |

| MCMV | M78 | TATTTT | −148 to −143 | TATAAG | −104 to −99 | GTCGCCATGC | |

| HCMV | UL78 | TATTTA | −149 to −144 | TAATTT | −91 to −86 | TCCATCATGT | 37 to 46b |

| HHV-6 | U51 | TATTTT | −140 to −135 | TATATA | −103 to −97 | ||

| HHV-7 | U51 | TATTTT | −146 to −141 | TATAAA | −69 to −64 | ||

FIG. 3.

The RCMV R78 gene is transcribed at both E and L times of infection in REF. Lanes 1 and 5 of the autoradiograph of a Northern blot hybridized with an R78-specific probe represent mRNA from mock-infected (M) cells. Lanes 2 to 4 represent the IE, E, and L phases of infection, respectively; lanes 6 to 8 represent transcripts from REF at 2, 8, and 48 h p.i., respectively. The estimated lengths of the different transcripts are indicated at the right in kilobases.

An R78-specific transcript with a length of approximately 1.8 kb was detected during both the E and L phases (Fig. 3, lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). Since the R78 ORF was found to comprise 1,422 bp, and a putative polyadenylation signal (AATAAA) is located 94 bp downstream of the R78 ORF, we postulate that the 1.8-kb transcript corresponds to an mRNA that exclusively contains the R78 ORF. Two other R78-specific transcripts (3.7 and 5.7 kb, respectively) were detected during the L phase (lane 4) and at 48 h p.i. (lane 8). At 8 h p.i., we detected a 3.9-kb transcript (lane 7) but not the 3.7-kb transcript. It is possible that early after infection the combined transcription of R77 and R78 is initiated at a location 0.2 kb upstream of the transcription start site of the 3.7-kb transcript. Alternatively, since we did not use strand-specific probes, the 3.9-kb transcript could have derived from the opposite strand of the R77/R78 locus. However, this was not investigated further. The 3.9- and 3.7-kb transcripts may contain the R78 ORF as well as one or more neighboring ORFs. This hypothesis is supported by the notion that the gene upstream of R78 (R77; see below) lacks a polyadenylation site at its 3′ end. Additional Northern blot hybridization data (shown below) support the hypothesis of cotranscription of R77, R78, and other RCMV genes.

Generation of RCMV strains with a deletion of the R78 gene.

To investigate the role of R78 in the pathogenesis of RCMV disease, we constructed a mutant RCMV strain (RCMVΔR78a) in which a 1,030-bp BglII-SalI fragment from the R78 gene was deleted and replaced with a 1.5-kb neo expression cassette (Fig. 4). Another RCMV mutant strain (RCMVΔR78c) was constructed such that an 80-bp SalI fragment was replaced by the neo cassette (Fig. 4). Consequently, the part of R78 that encodes the putative intracellular C terminus was deleted and replaced by an irrelevant sequence of similar length, while the part that encodes the N terminus (including the seven predicted transmembrane helices) was preserved (Fig. 4). The deletion/insertion mutations were first introduced into plasmids containing the R78 gene (Fig. 4). The R78 gene within the RCMV genome was subsequently replaced by either of the mutated R78 genes via homologous recombination, after transfection of fibroblasts with the recombination plasmids and infection with RCMV. Selection for recombinant strains was established by supplementing the growth medium with G418. After plaque purification of the virus, the purity and integrity of the recombinant strains were checked by Southern blot analysis. Virion DNA from RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, and RCMVΔR78c was purified and digested with BamHI-NcoI (Fig. 5). We also digested purified virion DNA with either BamHI, BamHI-BglII, BamHI-EcoRV, NcoI, SalI, or SalI-EcoRV (data not shown). After agarose gel electrophoresis and transfer of the DNA to a filter, hybridization was done with either an R78-specific probe or a neo-specific probe. As shown in Fig. 5, the observed hybridization signals correspond exactly to the predicted restriction fragments. In addition, contaminating wt virus fragments were not detected in the RCMVΔR78a and RCMVΔR78c lanes (Fig. 5). These findings indicated that both recombinant strains are pure and contain the appropriate mutations.

RCMVΔR78c transcripts.

The deletion of the R78 ORF might invoke unforeseen events such as disruption of unknown promoter/enhancer regions of the neighboring gene R77, R79, or R80. To investigate the effect of modification of the R78 genes on transcription of these neighboring genes, a Northern blot hybridization experiment was performed with poly(A)+ RNA from REF infected with one of the two recombinant viruses (RCMVΔR78c) and wt RCMV-infected REF. The genes upstream and downstream of the R78 gene were found to have considerable sequence similarity to the MCMV M77, M79, and M80 genes (54), respectively (data not shown). These RCMV genes are therefore referred to as R77, R79, and R80, respectively. Probes were generated from R77-, R78-, R79-, R79/R80-, and neo-specific DNA fragments (Fig. 6A and B) and hybridized with poly(A)+ RNA extracted from either mock-, RCMV-, or RCMVΔR78c-infected fibroblasts at 48 h p.i. (Fig. 6C).

In agreement with a previous Northern blot hybridization experiment (Fig. 3), the R78-specific probe hybridized to three distinct RCMV transcripts of 1.8, 3.7, and albeit weakly, 5.7 kb, respectively (Fig. 6C, lane 5). Our hypothesis that the larger two of these R78-specific transcripts also contained the R77 ORF was verified by hybridization with an R77-specific probe, which led to the detection of similar 3.7- and 5.7-kb transcripts (lane 2). In poly(A)+ RNA from RCMVΔR78c-infected REF, the R77-specific probe and the R78-specific probe hybridized to similar transcripts. Interestingly, these transcripts are approximately 1 kb longer than their counterparts from wt RCMV-infected REF (lanes 3 and 6). These transcripts also hybridized to a neo-specific probe (lane 15), indicating that the 2.8-kb transcript (lanes 6 and 15) contains the modified R78 ORF as well as neo sequences, and both the 4.7-kb transcript (lanes 3, 6, and 15) and the 6.7-kb transcript (lanes 3, 6, and 15) encompass R77, the modified R78 ORF, as well as neo sequences (Fig. 6B). Additionally, the neo probe hybridized to a unique 1.2-kb transcript (lane 15). A similar neo-specific transcript was previously found to be expressed by an RCMV strain (RCMVΔR33) of which the R33 gene was disrupted by the neo gene (9).

R79-specific transcripts were detected in neither wt RCMV- nor RCMVΔR78c-infected REF (Fig. 6C, lanes 8 and 9). This might be a consequence of either a low level of R79 transcription or low efficiency of labeling of the R79-specific probe that was used for hybridization. Thus, a larger probe specific for both R79 and R80 was derived from the 1088-bp BglII-SalI fragment from plasmid p116 (Fig. 6A and B). With this probe, transcripts of similar lengths (2.4 kb) were detected in either RCMV- or RCMVΔR78c-infected REF (Fig. 6C, lanes 11 and 12). Since the lengths of these transcripts correspond to the size of the R80 ORF (2,457 bp [13]), we hypothesize that they contain R80 mRNA rather than R79 mRNA (Fig. 6A and B). Although we cannot formally exclude the possibility that disruption of the R78 ORF affects transcription of the R79 gene, we hypothesize that transcription of R79 does not differ between RCMV and RCMVΔR78c. This hypothesis is based on the following two observations. First, the putative promoter of R79 is likely to be situated upstream of the R79 ORF, within the R80 ORF distant from the disrupted R78 site in RCMVΔR78c. In addition, a potential polyadenylation site downstream of the R79 ORF and neighboring the R78 ORF (complementary to nucleotides 1858 to 1863 of GenBank accession no. AF077758) is preserved in both RCMVΔR78c and RCMVΔR78a.

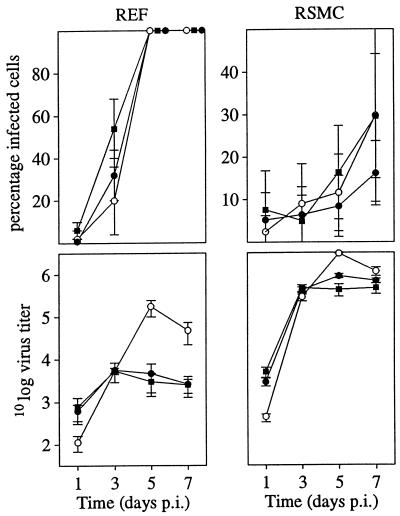

The R78 gene is important for efficient virus replication in various cell types in vitro.

The replication characteristics of RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, and RCMVΔR78c were assessed in four different cell types: REF RHEC, RSMC, and R2Mφ. Cells were infected with either RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, or RCMVΔR78c, and the proportion of infected cells relative to the total population of cells was determined at various time points. Additionally, the amount of excreted infectious virus was determined for each cell type. As shown in Fig. 7, the infected cell ratios did not differ significantly among REF and RSMC infected with either wt RCMV or each of the recombinant viruses during the observed time course. Also, infected cell ratios as well as virus titers in the culture medium of RHEC and R2Mφ infected with either wt or recombinant virus did not differ significantly (data not shown). However, clear differences were observed in virus titers in the culture medium of virus-infected REF and RSMC. In particular, at days 5 and 7 p.i., virus titers were 10- to 100-fold lower in the culture medium of both RCMVΔR78a- and RCMVΔR78c-infected REF than in the culture medium of wt RCMV-infected REF (Fig. 7). Additionally, at day 5 p.i., virus titers were 10-fold lower in the culture medium of recombinant virus-infected RSMC than in the medium of wt virus-infected RSMC (Fig. 7). Taken together, these data suggest that (i) R78-deleted viruses enter cells and spread throughout the monolayers of cells at similar rates as wt virus and (ii) in REF and RSMC, the production of recombinant virus is less efficient than the production of wt virus.

FIG. 7.

RCMV is attenuated upon deletion of the R78 gene. REF were infected at an MOI of 0.01 with either wt RCMV (○), RCMVΔR78a (■), or RCMVΔR78c (●). RSMC were infected with wt and mutant virus at an MOI of 1 (relative to REF infection). The upper graphs show the infected cell/total cell ratios at various time points p.i.; the lower graphs show virus titers determined in culture medium up to 7 days p.i. Standard deviations are indicated by vertical bars.

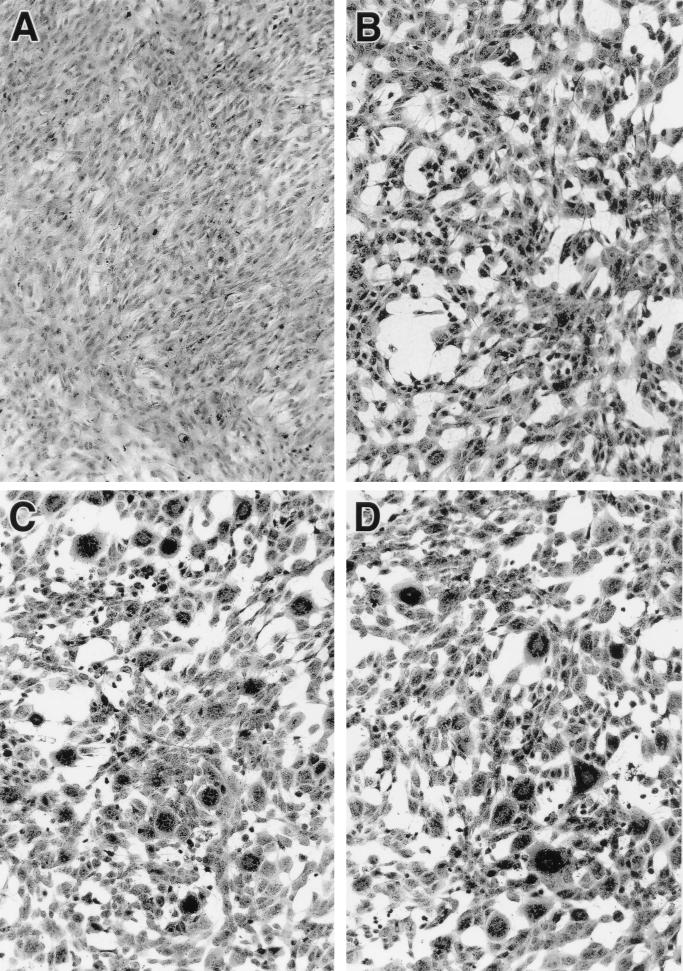

RCMVΔR78a and RCMVΔR78c induce syncytium formation in REF.

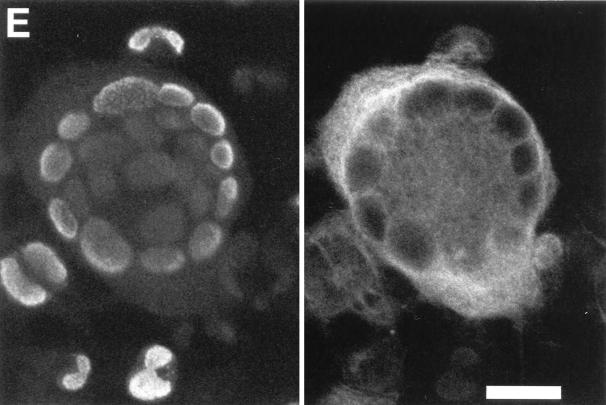

In addition to the differences in virus replication between wt and mutant viruses, the morphology of REF infected with either RCMVΔR78a or RCMVΔR78c clearly contrasted with that of wt virus-infected REF. Within the monolayers of mutant RCMV-infected REF (Fig. 8C and D) but not in those of infected RSMC, RHEC or R2Mφ, we observed syncytium-like cellular cultures that were larger than those typically seen in wt RCMV-infected REF monolayers (Fig. 8B). These structures appear 3 to 4 days p.i. To investigate the nature of these structures more closely, they were subjected to immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser scan microscopy. To this purpose, virus-infected REF were stained with MAb RCMV 8, which detects E-phase-expressed antigens in the nuclei (20). Additionally, these cells were counterstained with phalloidin, which binds to cytoskeletal F-actin fibers localized in the cytoplasm. MAb RCMV 8 and phalloidin were labeled with fluorescent markers fluorescein isothiocyanate and rhodamine, respectively. Surprisingly, the large structures that were seen in either RCMVΔR78a- or RCMVΔR78c-infected REF appeared to consist of a single cytoplasmic entity encapsulating 2 to 20 distinct nuclei. A typical example of such a syncytium-like structure is shown in Fig. 8E. The significance of these polykaryotic cells, or syncytia, and their relation to the function of the R78 gene is discussed below.

FIG. 8.

RCMV R78 deletion mutants induce syncytium formation in vitro. Immunofluorescence micrographs (magnification of ×400) show uninfected REF (A) and REF infected with either wt RCMV (B), RCMVΔR78a (C), or RCMVΔR78c (D). (E) Confocal laser scan micrograph taken from a syncytium structure in a monolayer of RCMVΔR78c-infected REF. The scale bar indicates 20 μm. The left-hand frame shows intracellular F-actin fibers that were stained with phalloidin-rhodamin (Eugene, Leiden, The Netherlands); the right-hand frame, of the same microscopic view, shows the nucleic distribution of RCMV E antigens detected by MAb RCMV 8 plus anti-mouse–fluorescein isothiocyanate.

R78 has a critical function in the pathogenesis of RCMV infection in vivo.

The role of R78 in the pathogenesis of RCMV disease was investigated by infection of rats with either wt or mutant virus. To compare virus dissemination in wt virus-infected and mutant virus-infected rats, two groups of immunocompromised rats were infected with 5 × 106 PFU of either RCMV or RCMVΔR78c. At days 4 and 21 p.i., the presence of virus in internal organs (aorta, heart, kidney, liver, lung, lymph nodes, pancreas, salivary glands, spleen, and thymus) of the infected rats was determined. At day 4 p.i., virus could be detected in 18% of the aforementioned organs in wt RCMV-infected rats and in 9% of the organs of RCMVΔR78c-infected rats, as determined by either plaque assay or immunohistochemistry. At this time point, the highest virus titers were found in the spleens of wt virus- or mutant virus-infected rats. In contrast to the marked differences in replication efficiency between wt and deletion mutant virus in vitro, the differences in the amount of virus recovered from either spleen (Table 3) or other organs (not shown) of infected rats were less dramatic. Neither wt nor mutant virus could be detected in the liver, pancreas, and salivary glands at day 4 p.i. At day 21 p.i., virus could be recovered from salivary glands of both wt RCMV- and RCMVΔR78c-infected rats but not from any of the other organs analyzed. Surprisingly, virus titers in salivary glands did not differ significantly between RCMV- and RCMVΔR78c-infected rats (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Virus titers and immunohistochemical detection of RCMV and RCMVΔR78c in salivary glands and spleen tissue

| Virus | Salivary gland

|

Spleen

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 4 p.i.

|

Day 28 p.i.

|

Day 4 p.i.

|

Day 28 p.i.

|

|||||

| Titer (log10 PFU/ml) | IPOXa | Titera mean log10 PFU/ml ± SD | IPOX | Titera mean log10 PFU/ml ± SD | IPOX | Titer (log10 PFU/ml) | IPOX | |

| RCMV | <1 | 0 | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 5 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2 | <1 | 0 |

| RCMVΔR78c | <1 | 0 | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 5 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0 | <1 | 0 |

Immune peroxidase assay (IPOX) data are presented as the number of rats of which the organ tissue was found RCMV positive of five rats tested.

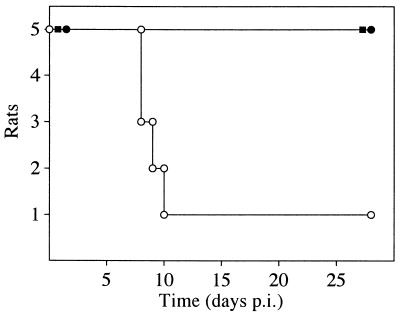

In a separate in vivo experiment, the virulence of wt and mutant viruses was determined by infecting rats with potentially lethal doses of virus. To this purpose, three groups of 4-week-old immunosuppressed rats were infected with 106 PFU of either RCMV, RCMVΔR78a, or RCMVΔR78c. Surprisingly, we found that mortality was dramatically lower in RCMVΔR78a- and RCMVΔR78c-infected rats than in RCMV-infected rats (Fig. 9). This result indicates that R78 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of RCMV infection.

FIG. 9.

The R78 gene plays a vital role in RCMV pathogenesis in vivo. The graph indicates survival of three groups of immunocompromised rats after intraperitoneal inoculation with 106 PFU of either wt RCMV (○), RCMVΔR78a (■), or RCMVΔR78c (●). Survival was recorded up to day 28 p.i.

DISCUSSION

Herpesviruses are known for the large size and complexity of their genomes, which encompass a vast number of genes, many of which are homologous to genes of the host organism. Beta- and gammaherpesvirus genomes contain genes homologous to GCR genes of the host. Eighteen beta- and gammaherpesvirus-encoded GCR genes have been recognized to date (4, 9, 21–23, 25, 33, 44, 49, 48, 54, 57, 63). These genes can be arranged into four groups based on sequence homology, genome location, and function of the respective gene product. One group (the US28 family) consists of two GCR genes: US27 and US28 (23). Both are exclusively present within an unconserved region of the HCMV genome (22). These GCRs are highly similar to mammalian chemokine receptors (15, 30). Although little is known about the function of the GCR encoded by US27, the HCMV US28-encoded GCR is a well-studied example of a virus-encoded GCR with an immunomodulatory function. This receptor was shown to bind β chemokines MIP1α, MIP1β, RANTES, MCP-1, and MCP-3 (14, 31, 47). Additionally, Bodaghi et al. reported that the US28 gene product modifies the chemokine environment of HCMV-infected cells through sequestering of β chemokines by continuous internalization (15). A second group (the UL33 family) contains five GCR genes: HCMV UL33 (23), RCMV R33 (9), MCMV M33 (26), and HHV-6 and -7 U12 (33, 49). Both sequence and position of these genes within their respective genomes are conserved. Similar to the US28 family, GCRs of the UL33 family were shown to be related to chemokine receptors. Previously, we reported that the predicted amino acid sequences of UL33-like receptors share more similarity with mammalian chemokine receptors than with nonchemokine receptors (9). Moreover, Isegawa et al. (38) demonstrated that one member of the UL33 family of GCRs, HHV-6 U12, is a functional β-chemokine receptor capable of binding MIP1α, MIP1β, RANTES, and MCP-1 (38). Although not much is known about the function of this chemokine receptor-like family, Margulies et al. detected the UL33 protein in both the membranes of HCMV-infected cells and the envelopes of HCMV virions (43a). Additionally, both RCMV R33 and MCMV M33 genes were shown to be essential for RCMV and MCMV replication in salivary glands of infected rats and mice, respectively (9, 26). A third group (the gammaherpesvirus GCR family) consists of seven gammaherpesvirus-encoded chemokine receptor-like genes: Epstein-Barr virus BILF1 (5, 25), HVS ECRF3 (48), KSHV ORF 74 (4), murine gammaherpesvirus 68 ORF 74 (63), and equine herpesvirus E1, E6, and E8 (57). In contrast to GCR genes of the US28 and UL33 family, sequences of the gammaherpesvirus GCR family are less well conserved. However, like GCR genes of the US28 and UL33 family, they show significant similarity with mammalian chemokine receptors (4, 26, 48, 57, 63). The role of any of these GCRs in replication or persistence of gammaherpesviruses is unknown. To date, two members of this family have been studied in detail. The HVS ECRF3-encoded GCR was shown to be capable of binding α chemokines interleukin-8, GRO/MGSA, and NAP-2 (1). Another gammaherpesvirus-encoded GCR, the KSHV ORF 74 gene product, was demonstrated to bind both α (interleukin-8, MGSA, NAP-2, and PF-4) and β (I-309 and RANTES) chemokines. In addition, the ORF 74 protein was found to be constitutively active (4), having both oncogenic and angiogenic potential (7). A fourth, novel group of GCR genes (the UL78 family) comprises five betaherpesvirus ORFs that were recently recognized as putative GCR genes: HCMV UL78, RCMV R78, MCMV M78, and HHV-6 and -7 U51 (references 33, 49, and 54 and this report). Similar to the positions of GCR genes of the UL33 family, the positions of the UL78-like genes are conserved within betaherpesvirus genomes. However, in contrast to the sequences of the UL33-like genes, the sequences of the UL78 family are poorly conserved. The predicted amino acid sequences derived from the UL78-like genes significantly resemble neither chemokine receptors nor any other of the thousands of GCRs currently known. The assumption that UL78-like genes are GCRs is based on three characteristics: (i) the presence of seven hydrophobic regions within the predicted amino acid sequences derived from all UL78-like genes (53); (ii) the presence of two cysteine residues within these amino acid sequences, which might be required for correct folding of the GCR polypeptide (53); and (iii) a stretch of amino acids within these amino acid sequences which bears similarity to a domain known to be required for G protein coupling (53). Consequently, the UL78 family is a novel class of orphan GCRs encoded by betaherpesviruses.

To investigate the role of the R78 gene in virus replication, RCMV strains in which the R78 gene is disrupted were constructed. These R78 deletion mutant strains were found to replicate 10- to 100-fold less efficiently than wt RCMV in fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells in vitro. By contrast, RCMV and MCMV strains that carry a deletion of the R33 and M33 gene, respectively, were previously found to replicate in vitro with efficiencies similar to those of the corresponding wt viruses (9, 26). A difference between these mutants and the R78 deletion mutants was also seen in vivo: both R33 and M33 deletion mutants were found to be impaired in replication in salivary glands of infected animals, whereas R78 deletion mutants were demonstrated to replicate as efficiently as wt RCMV in salivary glands. It is therefore likely that although both R33 and R78 putatively encode GCRs, these genes exert unrelated functions.

A lower efficiency of virus replication in vitro was observed not only after deletion of the complete R78 ORF from the RCMV genome but also after deletion of the region that encodes the putative R78 GCR C terminus. This putative intracellular part of the protein is therefore likely to be essential for the function of the R78 protein. The C terminus, like the DRL motif in the second intracellular domain of the R78 protein, might be essential for G protein coupling and signal transduction, similar to what was found for other GCRs (53).

The RCMV R78 gene plays an important part in the pathogenesis of virus infection in vivo. This was inferred from the lower mortality seen among immunocompromised rats infected with either RCMVΔR78a or RCMVΔR78c than among animals infected with wt virus. Although we did not find significant differences in virus replication between recombinant and wt viruses in vivo, it is possible that the decrease in virulence that is seen after disruption of the R78 gene of RCMV is correlated with the observation that both RCMVΔR78a and RCMVΔR78c replicate less efficiently in fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells in vitro than wt virus. Similar to the R78 gene, the R33 GCR-like gene was reported to have a vital function in the pathogenesis of RCMV infection (9). It is likely that the HCMV counterparts of these genes (UL78 and UL33, respectively) have similar, important functions in the pathogenesis of HCMV infections in humans. The gene products of both UL78 and UL33 can therefore be considered as potential targets for future development of novel antiviral strategies.

The two recombinant RCMV strains described in this report induce syncytium formation in infected fibroblasts in vitro. Previously, syncytium formation has been observed in many different cell types infected with a variety of herpesvirus species: HCMV-infected human amnion cells (28), varicella-zoster virus-infected human melanoma cells (34), Epstein-Barr virus-superinfected Raji cells (8), HHV-6-infected human primary fetal astrocytes (35), HHV-7-infected T lymphocytes (56), and RCMV-infected Rat2 cells (11). In these cases, syncytium formation appears to be associated with the cell type or MOI, since the same virus strains fail to produce these syncytium (syn) phenotypes upon infection of other permissive cell lines (8, 28, 34, 35) or after infection at lower titers (8, 56). Well-defined syn loci were found within genomes of a limited number of herpesvirus species, in particular within the genomes of herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) strains: UL20 (6), UL24 (40), UL27-gB (29), and UL53-gK (37). Some HCMV genes were likewise associated with syncytium formation. Syncytia are produced in human glioblastoma cells that constitutively express HCMV UL55-gB (59). Additionally, the chemokine receptor encoded by HCMV US28 was shown to enhance cell-cell fusion in cells constitutively expressing retroviral envelope glycoproteins (52). The recombinant RCMV strains RCMVΔR78a and RCMVΔR78c are the first syn mutant CMVs reported. We postulate that functional R78-encoded GCRs transduce signals to the cellular interior, thereby creating an intracellular environment essential for the formation of protein complexes to establish intercellular junctions. In HCMV- and HSV-1-infected cells, these cell-to-cell junctions are basically composed of viral glycoproteins (27, 36, 43). Since many syn mutations are localized in HSV glycoprotein genes (29, 37), syncytia could be generated as a result of destabilized cell-to-cell contacts. The putative GCR encoded by R78 may mediate stabilization of glycoprotein complexes, directly by association with these glycoprotein complexes, or indirectly, through signal transduction to establish cell-to-cell contacts. These possible mechanisms for the function of the R78 gene product will have to be addressed in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Erik Beuken for cloning and sequencing of RCMV DNA. We also thank Joanne van Dam, Suzanne Kaptein, and Marjorie Nelissen for processing rat organs, Jos Broers for generating the confocal laser scan micrographs, and Rien Blok for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahuja S K, Murphy P M. Molecular piracy of mammalian interleukin-8 receptor type B by herpesvirus saimiri. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20691–20694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ALIGN Query. 1 January 1997, posting date. [Online.] ALIGN program. Genestream, Institut de Génétique Humaine, Montpellier, France. http://www2.igh.cnrs.fr/bin/align-guess.cgi. [11 January 1999, last date accessed.]

- 3.An S, Bleu T, Hallmark O G, Goetzl E J. Characterization of a novel subtype of human G protein-coupled receptor for lysophosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7906–7910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvanitakis L, Geras-Raaka E, Varma A, Gershengorn M C, Cesarman E. Human herpesvirus KSHV encodes a constitutively active G-protein-coupled receptor linked to cell proliferation. Nature. 1997;385:347–350. doi: 10.1038/385347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baer R J, Bankier A T, Biggin M D, Deininger P L, Farrell P J, Gibson T J, Hatful G F, Hudson G S, Satchwell S C, Sequin C, Tuffnell P S, Barrell B G. DNA sequence and expression of the B95-8 Epstein-Barr virus genome. Nature. 1984;310:207–211. doi: 10.1038/310207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baines J D, Ward P L, Campadelli-Fiume G, Roizman B. The UL20 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 encodes a function necessary for viral egress. J Virol. 1991;65:6414–6424. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6414-6424.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bais C, Santomasso B, Coso O, Arvanitakis L, Geras Raaka E, Gutkind J S, Asch A S, Cesarman E, Gerhengorn M C, Mesri E A. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature. 1998;391:86–89. doi: 10.1038/34193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayliss G J, Wolf H. An Epstein-Barr virus early protein induces cell fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7162–7165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beisser P S, Vink C, van Dam J G, Grauls G, Vanherle S J, Bruggeman C A. The R33 G protein-coupled receptor gene of rat cytomegalovirus plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of viral infection. J Virol. 1998;72:2352–2363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2352-2363.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beisser P S, Kaptein S J F, Beuken E, Bruggeman C A, Vink C. The Maastricht strain and England strain of rat cytomegalovirus represent different betaherpesvirus species rather than strains. Virology. 1998;245:341–351. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beisser, P. S., C. A. Bruggeman, and C. Vink. Unpublished data.

- 12.Beuken E, Slobbe R, Bruggeman C A, Vink C. Cloning and sequence analysis of the genes encoding DNA polymerase, glycoprotein B, ICP 18.5 and major DNA-binding protein of rat cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1559–1562. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beuken, E., C. A. Bruggeman, and C. Vink. Unpublished data.

- 14.Billstrom M A, Johnson G L, Avdi N J, Scott Worthen G S. Intracellular signalling by the chemokine receptor US28 during human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:5535–5544. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5535-5544.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodaghi B, Jones T R, Zipeto D, Vita C, Sun L, Laurent L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier J, Michelson S. Chemokine sequenstration by viral chemoreceptors as a novel viral escape strategy: withdrawal of chemokines from the environment of cytomegalovirus-infected cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:855–866. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown T. Analysis of DNA sequences by blotting and hybridization. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1993. pp. 4.2.1–4.2.15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown T, Mackey K. Analysis of RNA by Northern and slot blot hybridization. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 4.9.1–4.9.16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruggeman C A, Meijer H, Dormans P H J, Debie W H M, Grauls G E L M, van Boven C P A. Isolation of a cytomegalovirus-like agent from wild rats. Arch Virol. 1982;73:231–241. doi: 10.1007/BF01318077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruggeman C A, Meijer H, Bosman F, van Boven C P A. Biology of rat cytomegalovirus infection. Intervirology. 1985;24:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000149612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruning J, Debie W H M, Dormans P H J, Meijer H, Bruggeman C A. The development and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against rat cytomegalovirus induced agents. Arch Virol. 1987;94:55–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01313725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao J X, Gershon P D, Black D N. Sequence analysis of HindIII Q2 fragment of capripoxvirus reveals a putative gene encoding a G-protein-coupled chemokine receptor homologue. Virology. 1995;209:207–212. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chee M S, Bankier A T, Beck S, Bohni R, Brown C M, Cerny R, Horsnell T, Hutchison III C A, Kouzarides T, Martignetti J A, Preddie E, Satchwell S C, Tomlinson P, Weston K M, Barrell B G. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;154:125–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chee M S, Satchwell S C, Preddie E, Weston K M, Barrell B G. Human cytomegalovirus encodes three G protein-coupled receptor homologues. Nature. 1990;344:774–777. doi: 10.1038/344774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damoiseaux J G M C, Döpp E A, Calame W, Chao D, MacPherson G G, Dijkstra C D. Rat macrophage lysosomal membrane antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody ED1. Immunology. 1994;83:140–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis-Poynter N J, Farrell H E. Masters of deception: a review of herpesvirus immune evation strategies. Immunol Cell Biol. 1996;74:513–522. doi: 10.1038/icb.1996.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis-Poynter N J, Lynch D M, Vally H, Shellam G R, Rawlinson W D, Barrell B G, Farrell H E. Identification and characterization of a G protein-coupled receptor homolog encoded by murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1997;71:1521–1529. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1521-1529.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dingwell K S, Brunetti C R, Hendricks R L, Tang Q, Tang M, Rainbow A J, Johnson D C. Herpes simplex virus glycoproteins E and I facilitate cell-to-cell spread in vivo and across junctions of cultured cells. J Virol. 1994;68:834–845. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.834-845.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figueroa M E, Geder L, Rapp F. Infection of human amnion cells with cytomegalovirus. J Med Virol. 1978;2:369–375. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890020410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gage P J, Levine M, Glorioso J C. Syncytium-inducing mutations localize to two discrete regions within the cytoplasmic domain of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein B. J Virol. 1993;67:2191–2201. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2191-2201.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao J L, Murphy P M. Human cytomegalovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional beta chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28539–28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao J L, Kuhns D B, Tiffany H L, McDermott D, Li X, Franke U, Murphy P M. Structure and functional expression of the human macrophage inflammatory protein 1α/RANTES receptor. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1421–1427. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerszten R E, Chen J, Ishii M, Ishii K, Nanevicz T, Turck C W, Vu T H, Coughlin S R. Thrombin receptor’s specificity for agonist peptide is determined by its extracellular surface. Nature. 1994;368:648–651. doi: 10.1038/368648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gompels U A, Nicholas J, Lawrence G, Jones M, Thomson B J, Martin M E, Efstathiou S, Craxton M, Macaulay H A. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content and genome evolution. Virology. 1995;209:29–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harson R, Grose C. Egress of varicella-zoster virus from the melanoma cell: a tropism for the melanocyte. J Virol. 1995;69:4994–5010. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4994-5010.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He J, McCarthy M, Zhou Y, Chandran B, Wood C. Infection of primary human fetal astrocytes by human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1996;70:1296–1300. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1296-1300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber M T, Compton T. The human cytomegalovirus UL74 gene encodes the third component of the glycoprotein H-glycoprotein L-containing envelope complex. J Virol. 1998;72:8191–8197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8191-8197.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutchinson L, Goldsmith K, Snoddy D, Ghosh H, Graham F L, Johnson D C. Identification and characterization of a novel herpes simplex virus glycoprotein, gK, involved in cell fusion. J Virol. 1992;66:5603–5609. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5603-5609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isegawa Y, Ping Z, Nakano K, Sugimoto N, Yamanishi K. Human herpesvirus 9 open reading frame U12 encodes a functional β-chemokine receptor. J Virol. 1998;72:6104–6112. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6104-6112.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ISREC WU-BLAST server. 3 June 1999, revision date. [Online.] BLAST program, version 2.0. ISREC Bioinformatics Group, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/WUBLAST_form.html. [11 January 1999, last date accessed.]

- 40.Jacobson J G, Martin S L, Coen D M. A conserved open reading frame that overlaps the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene is important for viral growth in cell culture. J Virol. 1989;63:1839–1843. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1839-1843.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozak M. An analysis of 5′-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8125–8148. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.20.8125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuhn D E, Beall C J, Kolattukudy P E. The cytomegalovirus US28 protein binds multiple CC chemokines with high affinity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211:325–330. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laquerre S, Argnani R, Anderson D B, Zucchini S, Manservigi R, Glorioso J C. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding by herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoproteins B and C, which differ in their contributions to virus attachment, penetration, and cell-to-cell spread. J Virol. 1998;72:6119–6130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6119-6130.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43a.Margulies B J, Browne H, Gibson W. Identification of the human cytomegalovirus G protein-coupled receptor homologue encoded by UL33 in infected cells and enveloped virus particles. Virology. 1996;225:111–125. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Massung R F, Jayarama V, Moyer R W. DNA sequence analysis of conserved and unique regions of swinepox virus: identification of genetic elements supporting phenotypic observations including a novel G protein-coupled receptor homologue. Virology. 1993;197:511–528. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meijer H, Dreesen J C, van Boven C P. Molecular cloning and restriction endonuclease mapping of the rat cytomegalovirus genome. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:1327–1342. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-7-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myers E W, Miller W. Optimal alignments in linear space. Comput Appl Biosci. 1988;4:11–17. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neote K, DiGregorio D, Mak J Y, Horuk R, Schall T J. Molecular cloning, functional expression, and signaling characteristics of a C-C chemokine receptor. Cell. 1993;72:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90118-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicholas J, Cameron K R, Honess R W. Herpesvirus saimiri encodes homologues of G protein-coupled receptors and cyclins. Nature. 1992;355:362–365. doi: 10.1038/355362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicholas J. Determination and analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of human herpesvirus 7. J Virol. 1996;70:5975–5989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5975-5989.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orlandi A, Paul Ehrlich H, Ropraz P, Spagnioli L G, Gabbiani G. Rat aortic smooth muscle cells isolated from different layers and different times after endothelial denudation show distinct biological features in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:982–989. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.6.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parente M G, Chung L C, Ryynanen J, Woodley D T, Wynn K W, Bauer E A, Mattei M G, Chu M-L, Uitto J. Human type VII collagen: cDNA cloning and chromosomal mapping of the gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6931–6935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.6931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pleskoff O, Tréboute C, Alizon M. The cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28 can enhance cell-cell fusion mediated by different viral proteins. J Virol. 1998;72:6389–6397. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6389-6397.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Probst W C, Snyder L A, Schuster D I, Brosius J, Sealfon S C. Sequence alignment of the G-protein coupled receptor superfamily. DNA Cell Biol. 1992;11:1–20. doi: 10.1089/dna.1992.11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rawlinson W D, Farrell H E, Barrell B G. Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1996;70:8833–8849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8833-8849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stals F S, Bosman F, van Boven C P, Bruggeman C A. An animal model for therapeutic intervention studies of CMV infection in the immunocompromised host. Arch Virol. 1990;114:91–107. doi: 10.1007/BF01311014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Secchiero P, Berneman Z N, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Biological and molecular characteristics of human herpesvirus 7: in vitro growth optimalization and development of a syncytia inhibition test. Virology. 1994;202:506–512. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Telford E A, Watson M S, Aird H C, Perry J, Davison A J. The DNA sequence of equine herpesvirus 2. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:520–528. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.TMpred—Prediction of Transmembrane Regions and Orientation. 3 June 1999, revision date. [Online.] TMpred program. ISREC Bioinformatics Group, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html. [11 January 1999, last date accessed.]

- 59.Tugizov S, Wang Y, Qadri I, Navarro D, Maidji E, Pereira L. Mutated forms of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B are impaired in inducing syncytium formation. Virology. 1995;209:580–591. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vossen R C R M, Derhaag J G, Slobbe-van Drunen M E P, Duijvestijn A M, van Dam-Mieras M C E, Bruggeman C A. A dual role for endothelial cells in cytomegalovirus infection? A study of cytomegalovirus infection in a series of rat endothelial cell lines. Virus Res. 1996;46:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(96)01375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vink C, Beuken E, Bruggeman C A. Structure of the rat cytomegalovirus genome termini. J Virol. 1996;70:5221–5229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5221-5229.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vink, C., E. Beuken, and C. A. Bruggeman. Unpublished results.

- 63.Virgin H W, IV, Latreille P, Wamsley P, Hallsworth K, Weck K E, Dal Canto A J, Speck S H. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol. 1997;71:5894–5904. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5894-5904.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson R, Ainscough R, Anderson K, Baynes C, Berks M, Bonfield J, Burton J, Connell M, Copsey T, Cooper J, Coulson A, Craxton M, Dear S, Du Z, Durbin R, Favello A, Fulton L, Gardner A, Green P, Hawkins T, Hillier L, Jier M, Johnston L, Jones M, Kershaw J, Kirsten J, Laister N, Latreille P, Lightning J, Lloyd C, McMurray A, Mortimore B, O’Callaghan M, Parsons J, Percy C, Rifken L, Roopra A, Saunders D, Shownkeen R, Smaldon N, Smith A, Sonnhammer E, Staden R, Sulston J, Thierry-Mieg J, Thomas K, Vaudin M, Vaughan K, Waterston R, Watson A, Weinstock L, Wilkinson-Sproat J, Wohldman P. 2.2 Mb of contiguous nucleotide sequence from chromosome III of C. elegans. Nature. 1994;368:32–38. doi: 10.1038/368032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu M, Lewis R V. Structure of a protein superfiber: spider dragline silk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7120–7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yasuda K, Raynor K, Kong H, Breder C D, Takeda J, Reisine T, Bell G I. Cloning and functional comparison of kappa and delta opioid receptors from mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6736–6740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]