Abstract

Partner notification (PN) is considered integral to the management of sexually transmitted infections (STI). Patient-referral is a common PN strategy and relies on index cases notifying and encouraging their partners to access treatment; however, it has shown limited efficacy. We conducted a mixed methods study to understand young people’s experiences of PN, particularly the risks and challenges encountered during patient-referral. All young people (16–24 years) attending a community-based sexual and reproductive health service in Zimbabwe who were diagnosed with an STI were counselled and offered PN slips, which enabled their partners to access free treatment at the service. PN slip uptake and partner treatment were recorded. Among 1807 young people (85.0% female) offered PN slips, 745 (41.2%) took up ≥1 PN slip and 103 partners (5.7%) returned for treatment. Most participants described feeling ill-equipped to counsel and persuade their partners to seek treatment. Between June and August 2021, youth researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 41 purposively selected young people diagnosed with an STI to explore their experiences of PN. PN posed considerable social risks, threatening their emotional and physical safety. Except for a minority in long-term, publicly acknowledged relationships, participants did not expect PN would achieve successful outcomes. Public health discourse, which constructs PN as “the right thing to do”, influenced participants to adopt narratives that concealed the difficulties of PN and their unmet needs. Urgent interrogation is needed of whether PN is a suitable or constructive strategy to continue pursuing with young people. To improve the outcomes of preventing reinfection and onward transmission of STIs, we must consider developing alternative strategies that better align with young people’s lived experiences.

Plain language summary Partner notification is a public health strategy used to trace the sexual partners of people who have received a sexually transmitted infection (STI) diagnosis. It aims to interrupt the chains of STI transmission and prevent reinfection by treating both the person diagnosed and their sexual partners. The least effective but most common partner notification strategy used in many resource-limited settings is called “patient referral”. This involves a sexual healthcare provider encouraging the person diagnosed to give a “partner notification slip” to their potentially exposed sexual partner/s and persuading them to access treatment. This research sought to better understand young people’s experiences of partner notification, particularly the risks and challenges they faced during patient-referral.

All young people (16–24 years) attending a community-based sexual and reproductive health service in Zimbabwe who were diagnosed with an STI were counselled and offered PN slips, which enabled their partners to access free treatment at the service. Young people trained as researchers interviewed 41 young people who had received a STI diagnosis to explore their experiences of partner notification.

Only a small number (5.7%) of the partners of those who took a slip attended the service for treatment. Most participants felt they did not have the preparation, skills, or resources to persuade their partners to seek treatment. Many described negative experiences during and after partner notification, including relationship breakdown, reputation damage, and physical violence.

These findings suggest that we should reconsider if partner notification is suitable or effective for use with young people. We should explore alternative approaches that do not present risks to young people’s social, emotional, and physical safety and well-being.

Keywords: sexually transmitted infections, partner notification, patient-referral, young people, social harms, risk landscape, risk hierarchies

Résumé

La notification au partenaire est considérée comme faisant partie intégrante de la prise en charge des infections sexuellement transmissibles (IST). L’orientation des patients est une stratégie fréquemment utilisée de notification au partenaire qui suppose que le patient zéro informe ses partenaires et les encourage à se faire traiter; néanmoins, elle a montré une efficacité limitée. Nous avons mené une étude à méthodologie mixte pour comprendre l’expérience des jeunes en matière de notification au partenaire, en particulier les risques et les obstacles rencontrés pendant l’orientation des patients. Tous les jeunes (16–24 ans) fréquentant un service de santé sexuelle et reproductive communautaire au Zimbabwe chez qui une IST avait été diagnostiquée ont été conseillés et se sont vu proposer des formulaires de notification au partenaire permettant à leurs partenaires d’avoir accès à un traitement gratuit dans le service. Le recours à ces formulaires et au traitement par les partenaires a été comptabilisé. Parmi les 1807 jeunes (dont 85.0% de femmes) à qui on a proposé un formulaire de notification des partenaires, 745 (41.2%) ont accepté ≥ 1 formulaire et 103 partenaires (5.7%) sont revenus pour se faire traiter. La plupart des participants ont indiqué qu’ils se sentaient mal préparés pour conseiller leurs partenaires et les persuader de demander un traitement. Entre juin et août 2021, de jeunes chercheurs ont réalisé des entretiens approfondis avec 41 jeunes sélectionnés à dessein chez qui une IST avait été diagnostiquée afin d’étudier leur expérience en matière de notification au partenaire. Cette notification posait des risques sociaux considérables, menaçant leur sécurité psychique et physique. À l’exception d’une minorité engagée dans des relations reconnues publiquement et de longue durée, les participants ne pensaient pas que la notification au partenaire obtiendrait des résultats satisfaisants. Le discours de santé publique, qui présente la notification au partenaire comme « la chose à faire », incitait les participants à adopter des récits cachant les difficultés de la notification au partenaire et leurs besoins insatisfaits. Il est nécessaire de se demander sans délai si la notification au partenaire est une stratégie adaptée ou constructive qu’il convient de continuer à appliquer avec les jeunes. Pour améliorer la prévention des réinfections et la transmission ultérieure des IST, nous devons envisager l’élaboration de stratégies de substitution, plus alignées sur l’expérience vécue par les jeunes.

Resumen

La notificación a la pareja (NP) se considera fundamental para el manejo de infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS). La referencia de pacientes es una estrategia común de NP, que consiste en que casos índice notifiquen y animen a sus parejas a conseguir tratamiento; sin embargo, ha mostrado eficacia limitada. Realizamos un estudio de métodos mixtos para entender las experiencias de NP de las personas jóvenes, en particular los riesgos y retos encontrados durante la referencia de pacientes. A todas las personas jóvenes (de 16 a 24 años) que asistieron a un servicio comunitario de salud sexual y reproductiva en Zimbabue y a quienes se les diagnóstico una ITS, se les brindó consejería y se les ofrecieron fichas de NP, que permitieron que sus parejas obtuvieran tratamiento gratuito en el servicio. Se registraron la aceptación de las fichas de NP y el tratamiento de las parejas. De 1807 jóvenes (85.0% mujeres) a quienes se les ofrecieron fichas de NP, 745 (41.2%) aceptaron ≥1 ficha de NP y 103 parejas (5.7%) regresaron para recibir tratamiento. La mayoría de las personas participantes describieron sentirse mal preparadas para asesorar y persuadir a sus parejas a que buscaran tratamiento. Entre junio y agosto de 2021, jóvenes investigadores realizaron entrevistas a profundidad con 41 personas jóvenes seleccionadas intencionalmente a quienes se les diagnosticó una ITS, con el fin de explorar sus experiencias de NP. La NP planteó considerables riesgos sociales, y puso en peligro su seguridad emocional y física. Salvo por una minoría que estaba en una relación a largo plazo reconocida públicamente, las personas participantes no esperaban que la NP tuviera buenos resultados. El discurso de salud pública, que construye la NP como “lo que es justo hacer”, influenció a las personas participantes para que adoptaran narrativas que ocultaron las dificultades de la NP y sus necesidades insatisfechas. Se necesita interrogación urgente para determinar si la NP es una estrategia idónea o constructiva que se debe continuar aplicando con las personas jóvenes. Para mejorar los resultados de prevención de reinfección y futura transmisión de ITS, debemos considerar formular otras estrategias que estén mejor alineadas con las vivencias de las personas jóvenes.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a major public health concern worldwide. In 2020, the World Health Organization estimated there were 374 million new infections with one of four curable STIs, Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia), Neisseria gonorrhoea (gonorrhoea), Trichomonas vaginalis (trichomoniasis) and syphilis, in people aged 15–49 years.1 Young people are particularly vulnerable to contracting STIs.2 In southern and eastern Africa, STIs are more prevalent among young than older age groups, with young women especially at risk.3,4

Partner notification (PN) is considered an essential component of the management of STIs, to both treat sexual partners and reduce the risk of re-infection in the index case.5 PN is based upon the premise that once an index case has been identified and treated, they represent a unique opportunity to “contact trace” other potential infections that might otherwise remain unidentified. Key PN strategies include “patient-referral” (index case notifies partner), “provider referral” (provider notifies partner), and “expedited partner therapy” (index case provides treatment or prescription to partner).5,6 Provider referral and expedited partner therapy have demonstrated higher efficacy and acceptability than patient-referral in high-income countries.7,8 Provider referral is expensive when compared with patient-orientated strategies, and requires greater infrastructural and personnel capacity.9 While expedited partner therapy is not legal in some settings, it is more cost-effective and has been shown to significantly reduce rates of reinfection.10 However, its use in southern African settings where it is legal and is included in national guidelines (such as in Zimbabwe), is currently limited to trials.10 Patient-referral has remained the most common PN method in the management of STIs in most resource-constrained settings.11

The purpose of PN is to achieve clinical and public health objectives, and counselling involves explaining to the index case how PN is both necessary and the only option to facilitate the treatment of the partner’s infection and prevent re-infection. Patient-referral is a multistep process requiring index cases to notify sexual partners, educate them on the adverse health impacts of STIs, and then persuade them to act on this information.12 Research has shown that PN takes place within diverse social, cultural, and health systems contexts, with factors such as gender equity and the configuration of notification strategies and availability of enhanced counselling within sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services significantly influencing PN’s acceptability (willingness to notify partners) and effectiveness (partners treated).11,13–16 This is evident in the wide variability both within and between studies.

There are very few studies focused specifically on young people in relation to PN, particularly in resource-limited settings.10,13,17 The risk landscape within which PN takes place is unique for young people.18–22 Adolescence is a period of sexual exploration, where relationships are often transient and unclearly defined.23 In many settings pre-marital sexual activity is deemed unacceptable, leading young people to hide their sexual activity.23,24 Age differences and power asymmetries are particularly common between adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) and their partners, leading to AGYW having limited negotiating power within their relationships.17,24 AGYW also have a high risk of intimate partner violence including sexual coercion.25–27 Economic precarity and emotional vulnerability are likely to make young people particularly vulnerable to social, emotional, and physical harms resulting from PN.28 In addition, youth engagement with sexual health services is often poor, due to barriers to access such as low acceptability of services, cost, concerns about confidentiality, and low STI literacy.18,21,22

There is relatively limited evidence about how the context framing young people’s sexual experiences, relationships and access to services impacts their response to being asked to notify their partners and their ability to do so. In this paper, we describe uptake of PN by young people and their sexual partners following diagnosis of an STI in a youth-friendly community-based integrated SRH service in Zimbabwe.29 We also explored qualitatively the experience of PN to gain a better understanding of young peoples’ experiences of PN following diagnosis of an STI, to consider its effectiveness and appropriateness.

Methods

Study design, sampling, and participants

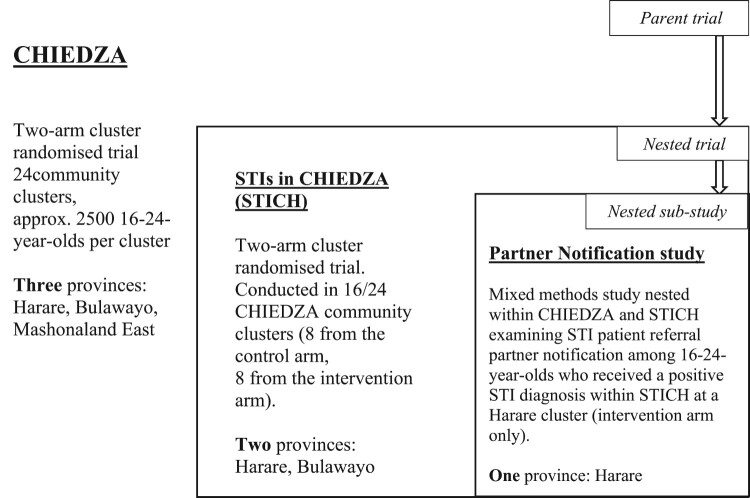

This mixed methods study was conducted as part of a large trial known as CHIEDZA (Trial registration number: NCT03719521).29 CHIEDZA was a cluster randomised trial of community-based integrated HIV and SRH services for youth aged 16–24 years in three provinces (each with eight clusters randomised 1:1 to trial or control arm) in Zimbabwe. Nested within CHIEDZA was a further trial investigating the impact of provision of STI testing and comprehensive management on population prevalence of STIs, known as STICH (STIs in CHIEDZA). This was conducted in two provinces (Harare and Bulawayo). STI testing and management were delivered by the CHIEDZA providers, and the intervention was integrated within the CHIEDZA service package. This mixed methods study of PN was embedded within the STICH trial. Figure 1 explains how the mixed methods partner notification sample was identified from within the STICH trial, which was nested within the CHIEDZA parent trial.

Figure 1.

Selection of participants from community clusters in the CHIEDZA parent and STICH trials

As part of STICH, clients accessing CHIEDZA services (aged 16–24 years) were offered testing for Neisseria gonorrhoea and Chlamydia trachomatis; women were also offered testing for Trichomonas vaginalis. Upon receiving a positive test result, clients were treated and offered counselling and PN was offered. The necessity to notify their partners was explained to the client in terms of addressing the risk of personal reinfection and interrupting the onward chain of transmission. In line with standard practice for patient-referral PN, slips were offered to clients (with no restriction on number of slips to each index) with a basic instruction provided to give the slip to their partner/s.

The qualitative component of the study was designed to facilitate insight into young people’s experiences of the PN process and the social landscape in which PN takes place, and to ensure that young people’s perspectives are considered, and can inform, future approaches to STI control and PN among young people. We engaged a diverse group of CHIEDZA clients, who had each received treatment for an STI at CHIEDZA within the past six months and were within intervention clusters in Harare province, in individual in-depth interviews. We employed purposive sampling by utilising CHIEDZA providers’ knowledge and interactions with clients to identify and invite individuals into the study to reflect the broader patterns of the CHIEDZA client-base. Providers telephoned eligible individuals to invite them to participate. Operational constraints meant that call attempts were not recorded. A number of individuals did not answer. Successful contact was made with 44 individuals, three of whom agreed but did not attend. A significant gender imbalance in CHIEDZA’s client-base, which is typical of most SRH services in the region, meant a similar imbalance was likely to be replicated in our sample. We utilised a snowball method to recruit more men into the study, by asking young men who were willing to participate to promote the study among their friendship group.

Ethics approval was provided by the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (12/2/2019) and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee (23/11/2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

Service providers recorded index client age and sex, the number of clients who took PN slips, and the number of slips taken by each client on electronic tablets using Survey CTO (SurveyCTO, Dobility, Inc, USA) at each visit. When/if a client’s partner(s) presented for treatment, this was also recorded.

In-depth interviews were conducted with 41 participants, aged 16–24 years, who had received an STI diagnosis within the past six months when attending one of the Harare intervention clusters. Interviews were conducted by four youth researchers (two male, two female) involved in the Youth Researchers Academy, a local, institutional programme training 18–24-year-olds in the purpose and practice of research.30 Promoting peers in research with young people is a well-documented approach within community-led health research.31, 32 Peer researchers have been identified as well-suited to exploring sensitive topics, such as young people’s sexual health, if conducted with sufficient training and support.33

A flexible topic guide was developed by the research team, including the youth researchers, and was shaped by consultation with providers and the CHIEDZA intervention research team. Insight into the key drivers of poor young people engagement and SRH outcomes, drawn from prior research conducted by the team and the wider literature, influenced how the interview guides were structured. Questions were framed to encourage empathetic enquiry about what young people felt they could or could not do in notifying their partners. Topics covered included the following themes: how participants first came to know about CHIEDZA and their motivations for visiting; initial perceptions and experiences of the CHIEDZA environment, staff, and services; reaction to receiving a positive STI diagnosis; experience of STI testing and treatment; their experience of PN; support received from family and friends.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed using STATA software (version 17.0). Continuous variables were summarised as means and SDs or medians and IQRs, and categorical variables as counts and percentages.

Analysis of qualitative interviews was closely intertwined with data collection. The study design enabled and facilitated an iterative data collection and analysis process, where interview analysis informed the structure and focus of consequent interviews. Interviews took place at the CHIEDZA service, lasted between 30 minutes and one hour, and were audio recorded. Guided by the preferences of participants, the interviews were conducted in Shona. Interviews were transcribed and translated into English. Youth researchers also wrote up field notes of each interview to capture their impressions of the interview encounter, paying particular attention to participants’ body language, for example discomfort, and hesitancy, as well as rapport and perceived levels of participants’ confidence in their discussion with the interviewer, to add additional dimensions to support interpretation of the transcripts.

In the preliminary stage of analysis, the research team reviewed these written documents and then together discussed initial analytical questions and emerging ideas, as well as potential changes to the interview guide to elicit further insights. The analysis was guided by the principles of interpretive thematic analysis.34 Members of the research team (JL, SB, VB, VK, LK, & EM) read all transcripts to familiarise with the data. Initial inductive coding of the data was developed during team discussions to generate themes and sub-themes. Discussions were documented through written analytical memos that were shared to shape further analytical inquiry. These meetings also served to develop youth researchers’ interviewing and analytical skills, shaping their approach to the next round of interviews and analysis.

Results

We first present the quantitative findings from the STICH trial about completion of partner notification among those who tested positive and took a PN slip. We then present the related qualitative findings, in which we explore the experiences of 41 individuals from within the STICH trial of engaging in partner notification.

From 21 September 2020 to 15 December 2021, overall 1807 (85.0% female, median age 21) (IQR 19–23) tested positive for any STI.3 Among them 745 (n = 41.2%) took up at least one PN slip and overall, 877 slips were taken up (median 1 slip, maximum 9 slips per index). At the end of the study, 106 partners of 103 clients (5.7%; 25 male, 78 female) of 1807 who tested positive for an STI returned for treatment at CHIEDZA. Of 539 clients across the Harare intervention sites who said they would notify their partner/s, only 22 partners sought treatment at CHIEDZA (6.1%).

Between June and August 2021, 41 individual in-depth interviews were conducted with participants attending the Harare intervention clusters, median age 22, 34 (82.9%) of whom were female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of qualitative participants (n = 41) aged 16–24 years

| N = 41 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 34 | 82.9 |

| Male | 7 | 17.1 |

| Age | ||

| 16–20 | 16 | 39.0 |

| 21–24 | 25 | 61.0 |

| Married | ||

| Yes | 11 (all female) | 26.8 |

| No | 29 | 70.7 |

| Divorced | 1 | 2.4 |

| Children | ||

| Yes | 12 (all female) | 29.3 |

| No | 29 | 70.7 |

Of the 41 participants interviewed, 35 (85.4%) reported they had carried out PN. Of these 35, 10 (28.6%) reported that their partners attended CHIEDZA for treatment and seven (20.0%) reported that their partners told them that they would go elsewhere for treatment. It is not possible to verify from our qualitative data whether partners did indeed go elsewhere or the reasons why partners of 25 participants did not come to CHIEDZA for testing and treatment.

Engaging in STI testing and treatment: comfort and confidence found through youth-friendly services

All the participants interviewed had been receiving SRH care from CHIEDZA. Other than their experience of being asked to notify their partners, they shared overwhelmingly positive accounts of their experiences of CHIEDZA. They characterised CHIEDZA as an exceptionally supportive environment, in which they felt comfortable and motivated to access acceptable and youth-centred SRH services. They credited the kindness of staff, the provision of free testing and treatment and the accompanying sense of control over their health as critical factors which encouraged them to engage in STI treatment and care. They valued being at ease in discussing sexual behaviour and reproductive health with knowledgeable providers and positioned this in contrast to the absence of support they received from friends and family and the hostility they encountered or feared in seeking sexual healthcare within mainstream services.

“The first time I came I was shy. I remember I stood at the gate for 10 minutes until one of the health service providers approached me and talked to me in a comforting way. He told me I should just relax; that it’s not a big process or something major. So, I felt ok and followed him to the tent. The testing process was fast, and they made me feel comfortable. They didn’t judge me.” (IDI 4, 20-year-old male)

The kindness and compassion of providers continued with a positive diagnosis. Several participants described their limited knowledge about STIs prior to their interactions with CHIEDZA staff. There was a common misunderstanding that STIs are “the same as HIV” and that any STI diagnosis indicated an incurable lifelong condition requiring ongoing treatment. Once CHIEDZA staff explained about the treatment for their specific infection participants described feeling immense relief and a confidence to confront their infection.

“I thought STIs are the same as HIV and that if positive I will be taking pills for the rest of my life and cannot be cured. So, I just thought it’s better to die than to take pills for the rest of my life. But then they explained everything to me, that STIs are different from HIV, and I have to take the pills here and I will be fine.” (IDI 20, 21 years female)

The “confronting” ask of PN

This reported positive experience began to change when clients, who had been diagnosed with an STI, were asked by CHIEDZA providers, in line with clinical best practice, to notify their partner/s and to encourage them to access treatment either at CHIEDZA or at another service. While there was a recognition that executing this request may not be straightforward, PN was framed as a vital element of the treatment pathway, with the client’s risk of reinfection cited as the driving motivation to have a current sexual partner treated. Counsellors tended not to prepare clients for the multiple steps of PN, including first notifying, then educating a partner about STIs, and finally encouraging a partner to attend for treatment. Upon leaving CHIEDZA, participants described immediately seeing the difficult terrain ahead. Many participants shared that they felt ill-equipped to initiate conversations with their partners and produce the intended outcomes of PN.

“After I got my results, I was told to go and tell my boyfriend. When I was on my way home, I kept on thinking, how am I going to talk to my partner about this?” (IDI 5, 20-year-old female)

“They explained it to me in a good way. They told me that I had to go and give my partner the notification slip so that she also comes for testing and treatment. I went to my girlfriend’s place to tell her and take her [to the clinic], but because she’s a girl, coming out sometimes it’s a big deal.” (IDI 13, 19-year-old male)

While providers emphasised the clinical necessity of PN in the counselling sessions, in their interviews young people focused on the many social, emotional, and physical risks involved in the process. The risks of reputational damage and physical violence were recurrent themes. Young women described needing to carefully choose the time and place that they would tell their partners to minimise the physical danger that the process of partner notification posed to them.

“Yes, l did manage to give him the slip. l knew his character, so I gave it to him where l felt safe. Before l even finished my story, he slapped me on the cheek.” (IDI 12, 23-year-old female)

Their safety concerns were not limited to the potential for physical violence, but to the emotional and relational damage that it might provoke. Thirty participants were unmarried, which meant that most of them wanted to conceal that they were sexually active. Many feared how their partner would react, assuming that it would aggravate retaliatory revelations of pre-marital sex and accusations of promiscuity, or at least provoke damaging rumours, that could reach their family and community. In sharing the information about their STI diagnosis, they lost control over how it would be used.

For those who were married, being sexually active within their marriage was assumed and expected. However, many married participants were concerned that they would be accused by their partner of promiscuity within their relationship, or that their diagnosis would become known to others, damaging their reputation and future relationship prospects.

“People would not want to tell [their partner] for a fear of rejection or being embarrassed. Because you will not know what they will disclose after you tell them. Questions build up bro, ‘like, who was cheating?’ You know what I mean?” (IDI 21, 20-year-old male)

“I think sometimes it’s the fear of your partner being hurt with that information and telling everyone in your area. Then you find out that the girls will lose interest in you.” (IDI 6 22-year-old male)

Weighing up the social, physical, and relational risks of telling their partner/s against the clinical risks in not telling presented real dilemmas for participants. The perception that PN would lead to negative outcomes was particularly acute for female participants. Gendered power dynamics, which left women more vulnerable to being blamed for and associated with STIs within their relationship, influenced whether they felt safe to notify their partners.

“I thought of telling him but … the mood he was in that day made me think twice. I knew he was going to put all the blame on me and break up with me, so I remained quiet. When I did finally tell him, he accused me of giving the STI to him. I found out that he had blocked me on WhatsApp and his family stopped talking to me. You know, if you are a couple that is known by almost everyone in the area … when there is a breakup, the boy is the one who usually starts telling people that he broke up with her because she had an STI. You know what boys do.” (IDI 1, 20-year-old female)

“It’s hard to decide to tell your partner, because maybe he will not accept that that’s how you are. And what if you test positive and he is negative? So, you will be afraid of ruining the marriage if you tell him such a thing and sometimes your partner won’t understand at all so it’s just difficult.” (IDI 39, 24-year-old female)

Young people alluded to a perceived disconnect between the request to notify partners and the reality in doing so, which was exacerbated by these challenges not being explicitly acknowledged within the counselling they received. Despite participants speaking positively about receiving excellent SRH services provided by CHIEDZA, most also explained how they found implementing PN as they were asked to do by providers exceptionally difficult.

Moralising of public health: production of compliance narratives conceals unmet needs

Despite the substantial perceived challenges and risks of PN, participants described learning from the counselling sessions that “it was something I have to do, because it’s the morally right thing to do” (IDI 34, 20-year-old female). This was underpinned by the public health rationale that they had the “responsibility” to act because it could be within their control to stop further infection. Sharing the complex realities of their sexual lives, until this point, had been met without judgement by CHIEDZA providers. In contrast, PN was approached through a distinct and rare moral lens of client “responsibility”. Whether they were able to notify their partner/s was considered by some to reflect their moral worth, signalling a unique risk of judgement in articulating hesitancy or resistance to CHIEDZA providers about feeling unable to notify their partner.

“If I didn’t notify my partner about it, I will really be acting like the devil’s sister. I don’t really know but I think it’s not fair not to tell your partner. You just have to tell them and get ready for what they might say.” (IDI 17, 22-year-old female)

Young people assumed there were no alternatives to PN. This impression was in part shaped by the lack of options presented in the counselling sessions other than completing patient-referral. According to young people’s accounts, discussions about the risks of PN were not proactively initiated by providers, although they were occasionally voiced by participants. Despite the possibility that providers would have responded with compassion to a young person reluctant to tell their partner, the framing of PN as a “moral duty” and an individual responsibility appeared to restrict discussions about whether, in an individual’s particular situation, PN was a safe or desirable course of action to pursue.

Dilemmas in telling and threats to engagement

Faced with these substantial dilemmas, and not confident to raise them with providers, some participants looked to creative solutions to navigate the various harms in telling and not telling. A minority of participants engineered opportunities for their partner to be tested, unlinked to their own infection, so that they could then both receive treatment and circumvent the risks of PN. Participants tended not to tell the providers of their plans, anticipating that as they had diverged from the general advice, providers would disapprove.

“I was given a slip to go and give my boyfriend, but I didn’t give it to him. He doesn’t even know that I was tested. Mmm what if he ends our relationship? He is very short-tempered, I’m scared, I can’t tell him. I’m thinking of having sex again with him and not using protection. Then, after that, I will tell him that I think we need to get tested so we will come together here to get tested. Then we will be positive at the same time, and we get treatment (laughs). I got this idea from one of my friends.” (IDI 23, 21-year-old female)

Overall, we found that participants commonly refrained from sharing their concerns about PN with providers. This served to further narrow the conversation and, perhaps mistakenly, affirm that providers would not accept alternative approaches nor necessarily appreciate the enormity of the demands in completing PN. The perceived pressure to notify partners led some participants to doubt the value of attendance at CHIEDZA and question their ongoing engagement in care.

“Perhaps it was better off l didn’t give him the Notification Slip, or even, if l did not come in the first place.” (IDI 43, 17-year-old female)

“You know, when I used to pass CHIEDZA, going wherever I was going, I used to just think what you people of CHIEDZA had done; that you ended my relationship and I used to change my mood the moment I pass by.” (IDI 5, 20-year-old female)

Blind spots and peer research: expressing what can hardly be said

In this study, interview accounts were co-produced by young people, as participants, and youth researchers. While we do not presume that the youth researchers necessarily shared the participants’ socio-economic and educational backgrounds, the similarity in their ages did appear to positively impact rapport and participants’ confidence to share details of their experiences that they suggested they might not have told an older researcher. Within the interviews, there appear to be hints of an implicit shared understanding between the participant and interviewer of the gendered relational contours shaping young people’s sexual relations on account of their shared age.

Participant: You know what boys do.

Interviewer: Yah, true, they start telling their friends, even the whole neighbourhood.

Participant: Yes, I do not know what is wrong with boys (interviewer and participant laugh together).

(IDI 7, 24-year-old female):

This peer-based research approach may have enabled us to access additional insights in which hesitancy or inability to complete PN were alluded to.

Participant: You know, for us young people having an STI is something major although sometimes we take it lightly. Just for us to have an STI is something major in a relationship. Once you tell your boyfriend that you have an STI, it’s like you are telling him that you’re pregnant and it’s not his baby.

: (interviewer and participant laugh together)

Participant: You get it, so it’s kind of hard to tell your partner even if it’s not HIV, maybe it’s something minor but for him to know that you have an STI, it’s a deal breaker for guys you know that even if a guy tells a girl that they have an STI, although it’s treatable it’s just a deal breaker for us young people, you get it. (IDI 30, 20-year-old female)

This is further supported by a pattern we identified, where on several occasions, participants sought guidance from the youth researcher, asking them SRH-related questions before and after the interviews that they said they did not feel confident to ask providers. For example, despite having reported in the interview that she had completed PN one participant asked if she would be able to return to the service if she had not successfully completed PN. Another asked how she would be received if she were to return for STI treatment again so soon after her first treatment having not been able to abstain from sex with her untreated partner.

Discussion

Studies evaluating PN strategies have typically focused on intended clinical outcomes, such as the proportion of partners treated and index case reinfection rates.6,35,36 However, the social landscape in which PN takes place, which shapes these outcomes, is only recently gaining critical attention.7 Despite the high proportion of participants in this study reporting that they did notify their partners, they also emphasised the substantial risks and dilemmas involved in notifying their partners. This study has shown that for young people, the anticipated social, emotional, and physical risks of PN often outweigh the risk of reinfection. This is reflected in the low numbers of partners attending CHIEDZA for treatment after receiving a PN slip from clients. Furthermore, taking a PN slip did not contribute greatly to partner attendance: 45 of the 106 partners who did attend CHIEDZA for treatment were partners with a client who did not take a PN slip, suggesting that other factors influenced attendance. While the overall environment and individualised care offered by CHIEDZA had a positive impact on clients, specific standardised interventions such as patient-referral PN sat in tension with this. Patient-referral PN, even when conducted within highly acceptable youth-focused SRH services, is currently ill-suited to respond to the complex social and relational contexts of young peoples’ lives.

The relational context of young peoples’ sexual lives explained how and why PN provoked considerable anxiety about consequent potential harms. Echoing this study’s findings, an emerging body of literature suggests that the success of patient-referral is heavily reliant upon individual and relationship circumstances, local contextual factors and referral support.12 A range of factors, including income and education level, and power dynamics within relationships, greatly influences the capacity of an index case to enact notification.11 The over-riding trend, in current research and highlighted in this study, shows that the less power and influence held by index cases, who are disproportionately female, the less likely patient-referral will be successful regardless of the clients’ intention to notify.11 When the index case is an adolescent or young woman, her power and ability to influence a positive resolution of the PN process is likely lesser, exposing her to an increased risk of social, emotional, and physical harm and greater likelihood of reinfection.

Research examining HIV PN (most often described as onward disclosure), while well-established in adults,37–39 has not been closely examined in young people. We should pause, however, to consider whether insights from HIV PN more generally are instructive for guiding STI prevention and control. There are clear differences in the social and epidemiological landscape of STIs and HIV that alter the role and function of PN. Recent advances in HIV treatment and prevention, such as Treatment as Prevention (TasP) and Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U = U) have shifted the rhetoric around the “need to tell” in settings with access to consistent viral load testing and U = U messaging. The need for and effect of onward disclosure have been fundamentally changed by the virtual elimination of transmission risk. Appropriating lessons learned from HIV PN to guide STI prevention and control is therefore becoming increasingly less helpful and might, in fact, obscure the specific issues PN raises when used as an essential STI prevention strategy.

The accounts of young people in this study suggest that key differences in the clinical profile of curable STIs and HIV significantly impact decision-making surrounding testing and, we might expect, PN. Participants described their relief when CHIEDZA staff corrected their conflation of curable STIs and HIV: once they understood that their infection could be easily treated, their reluctance to be tested dissipated. However, their hesitancy quickly resurfaced when PN was introduced as the necessary and unavoidable next step. The social risks and harms associated with PN are common, regardless of the type of infection. We must place greater emphasis on the social and relational contexts in which any public health intervention operates, alongside equipping young people with correct clinical knowledge to ensure they feel empowered to test, but also to manage STI prevention in the context of their individual relationships.

Although not the focus of this study, it is unlikely that alternate PN strategies, such as provider referral and expedited partner therapy, would be able to circumvent the significant social, emotional, and physical risks described by participants as they would continue to occur within these contexts. While provider referral might alleviate the threat of immediate physical violence, it may not fully remove the risk of subsequent violence, abandonment, or disclosure of STI diagnosis, each of which was described by participants interviewed in this study. Expedited partner therapy might improve the proportion of partners treated by removing the need for partners to attend a health facility and participate in counselling9,10 but again, it does not reduce the social, physical, and emotional risks described by young people. PN requires critical evaluation, not only to examine how it can best be implemented, but whether it is indeed safe for young people at all and therefore how it can be adapted.

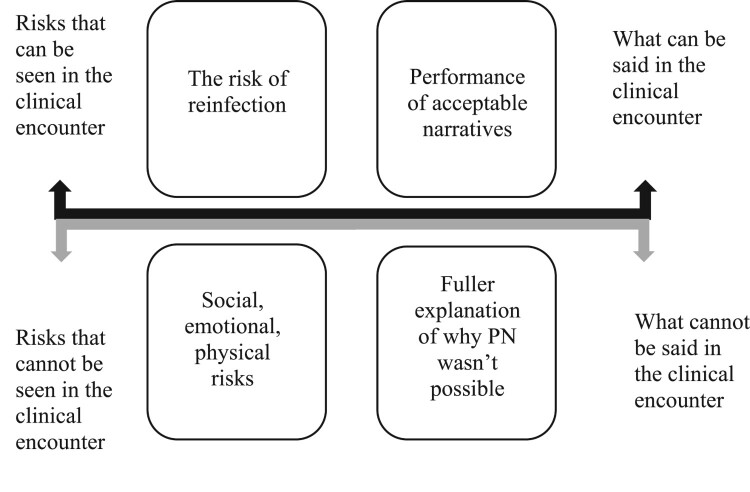

Risk landscapes: more than clinical risk

The risk of reinfection is positioned highest in the hierarchy of risks, and therefore drives a narrow focus on PN as the strategy to curb STI reinfection and onward transmission. Subsequent risks that might result from PN, such as the risk it poses for relationships, reputation, and individual wellbeing, tend not to be considered as posing equivalent risk. Ironically, in prioritising clinical objectives and not considering enough the social contexts within which PN takes place, these objectives are often not met: reinfection is not often averted. Failure to recognise the interconnectedness of the clinical and social has curtailed our ability to imagine alternative strategies.

The introduction of PN to clients by providers marked a shift in how young people in this study reflected on STI testing and treatment, as well as their wider perception of CHIEDZA. PN exposed a tension within the public health logic of offering youth-centred interventions, which created an open and accepting environment about a young person’s own diagnosis, and the narrower focus on clinical risk and personal responsibility embedded within STI control, which pushes for patient-referral PN to break chains of infection. As the clinical risk of reinfection occupies precedence during post-diagnosis STI management counselling, young people likely infer that a “hierarchy of risk” exists, with the social, emotional, and physical risks that PN might involve relegated to being of lesser importance and insufficient to render PN inappropriate.

Figure 2 shows the organisation of risk as it relates to the clinical encounter, and how this produces a narrow range of acceptable narratives available to clients when they returned to the clinic after they were advised to notify their partners. A fuller explanation of why they could not tell their partners remains unsaid under the pressure to perform an acceptable narrative of PN success (protecting your own health, protecting your partner’s health, performing a social duty to break chains of transmission). So, while the conversation between client and provider might appear uncomplicated, there is an implicit silence preventing the full range of clients’ concerns and worries from being shared and resolutions identified, even when open and non-judgemental dialogue had been the feature of client-provider relations previously.

Figure 2.

The risk landscape and partner notification

Risks to safety

The focus on PN as the singular means through which to reduce infection risk, overshadows the attention paid to the relational dynamics within sexual partnerships that give rise to gendered vulnerabilities. For example, where IPV may be a factor, PN can pose an extreme risk to safety.40,41 Gendered power dynamics within relationships and the gender imbalance in those accessing sexual health services and STI testing, places a disproportionate burden of these risks on young women.13,17 Furthermore, the constraint that relational dynamics place on an index case’s capacity to tell their partner and influence them to seek treatment is also left out of the conversation, reinforcing the idea that PN is routine and unproblematic and that difficulties should be privately managed. The lack of acknowledgement of the full range of risks associated with PN means that young people navigate this delicate balance often alone, having previously benefited from being able to talk openly to providers. Shame and stigma surrounding premarital sex heightens the risk because clients feel unable to call on support from family or friends.

A second moment of (not) telling: risks to engagement

PN is often framed as a moral duty, extending the responsibility that a young person has beyond their own health to being accountable for their partners’ health and by intervening in onward community transmission. This moralistic framing further entrenches young people’s reluctance to share concerns about the individual risks they might face, as it involves explicitly stating that they are prioritising the balance of risk for themselves over others. It also likely shapes some young people’s reticence to explain that they had not told. Such suppression of talk risks sanitising the discursive space that they had previously experienced as supportive and safe. Anticipating the problems that would be provoked through this second moment of telling, in which they would need to admit to providers they could not complete partner notification, can (and likely does) interrupt ongoing engagement in care. This risk to engagement, and previously established trust in youth-centred services, is under-appreciated in the broader conversation about PN and the risks it poses to young people’s health and wellbeing.

Tensions in delivering patient-referral PN in youth-centred services

Participants expressed positive feelings about their experiences receiving CHIEDZA services, including STI testing and treatment. They were motivated to engage in non-judgemental services in part because of the providers’ display of empathy to the contours of young peoples’ sexual lives. This suggests that the logic underpinning youth-centred services,42,43 which demonstrate compassion and support young people to facilitate their engagement in STI treatment and care and to minimise harms of infection, worked to enhance acceptability which translated into uptake of the service. However, the introduction of PN disrupts and unravels this relationship because the emphasis shifts explicitly to individual clinical treatment and public health outcomes, with much less attention paid to engaging with the broader social context in which their sexual behaviours and risks were embedded.

PN cannot always be done because it is not always safe to do so. Healthcare workers need to attend to the social realities of young people in order to engage and retain them in supportive and responsive care and thereby manage infection control. Individualised counselling about the “messy reality” of what is involved in PN is likely to have been curtailed by high demands on staff time, but it may also reflect that the centrality of PN, when conducted through patient-referral, needs to shift and accommodate alternatives which seek to protect and respond to the needs of the index case.

Resources – toolkit

In response to our findings, we developed a set of resources (online supplementary appendix) for immediate use within CHIEDZA to guide providers during post-diagnosis STI treatment and counselling. Matthews and colleagues’ open-source toolkit, which was designed for use with adults, was adapted to respond to the findings in our study with young people.44 However, these resources are unlikely to completely ameliorate the risks and dangers that PN raises; rather, they can be used to create open discursive spaces to encourage young people to articulate their concerns beyond the current singular focus on clinical risk. By introducing the social dimensions of PN and the possibility of not telling as a viable option, we intend for the resources to be beneficial to supporting provider–client relationships through facilitating more open and honest dialogue. These resources could become part of a broader re-think about public health interventions to control onward transmission of STIs among young people.

Where to next? Is PN safe for adolescents and young people?

The limited success of PN across population groups as an infection control strategy has led SRH practitioners and researchers to approach implementation and evaluation with tempered expectations.45 A growing awareness of the potential harms of PN is raising the question of the intervention’s suitability more prominently in the literature.13,17,45

Our findings serve as a warning for why ignoring the context of patient’s lives may render the clinical solution ineffective. Rather than interpreting a client’s inability to complete PN as patient non-compliance, it should instead alert us to the inappropriateness of an existing intervention, or in this case a public health expectation, to minimise related harm to patients. If, as we have learnt, PN imperils the physical, social, and emotional safety of the index case and undermines their engagement in care, while concurrently failing to achieve its clinical outcome, then the harms of PN are not “necessary” side-effects but an indication that the intervention may well be fundamentally ill-suited for purpose with this population group.

Given these findings, attention and investment ought to be directed toward developing and bolstering alternative strategies for engaging young people in STI testing and treatment. It may also be that the ongoing emphasis on pursuing PN in STI control has led to a slippage in understanding, or at least in our use of language about what PN is. It is a process, or strategy, rather than an outcome in itself. The clinical outcome that PN seeks to enable is the interruption of onward chains of transmission. We need to step back and focus on what strategies may be most effective, within specific contexts and for particular population groups, to achieve interruption transmission for STI control. If PN appears not to be a very effective strategy to interrupt transmission, and provokes other harms, then alternative indirect strategies may prove more effective. Social network testing and treatment may be a particularly relevant approach to achieve this outcome for use with young people to avoid the harms associated with patient-referral PN. Extending the reach of routine testing and treatment, particularly among young men, and strengthening condom advocacy will also reduce the burden of STI management on index cases.

Limitations

As previously mentioned, there was a gender imbalance in our sample despite our efforts to recruit men into the study. Young women made up the majority of CHIEDZA’s clients and this reflects trends in other SRH services. This was a limitation in the research; however, the data we were able to obtain from the few men in this study (n = 7/41) offers important insights into the gendered experiences of men when considering accessing SRH services. Our data were collected among young people willing to return to CHIEDZA to discuss their experiences of PN. It is possible then that extremely negative experiences may not have been collected, due to a reluctance to revisit these experiences. Operationally, we were unable to log all calls made during participant recruitment. Many who were called did not answer. This reluctance to participate potentially contributes to our hypothesis that PN is challenging for young people and presents dilemmas that are difficult to disclose to providers.

These limitations are reflective of the conditions of conducting research on sensitive sexual and reproductive health topics with young people. They further emphasise the need to create safe research spaces and relationships to investigate topics, which are likely characterised by a disconnect between public health advice and individual relational realities.

Conclusion

This study has explored young people’s experiences of PN within what they assessed to be a supportive and non-judgemental service environment, allowing us to consider the merits of the intervention itself. Young people found that PN involved unavoidable risk, and that it created a distance between clients and providers where the relationship had been trusting and empathic previously.

Whether PN is an appropriate and safe intervention where complex relational dynamics increase the risk to social and physical safety is a question that requires consideration across all age groups. However, it may be particularly pertinent in the context of young people’s sexual health where vulnerability to harm is more acute, and where maintaining engagement is already precariously balanced. When PN exposes young people to harms beyond the clinic, we must ask whether that intervention is fit for use with this population, and actively explore alternatives which strike a more appropriate balance of risks and can protect young people and their engagement in care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the participants who generously shared their experiences and time with us for this study, as well as CHIEDZA staff and our funders.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by MRC/DFID/NIHR [grant number MR/T040327/1]. The study was also supported by funding from the Wellcome Trust [Grant number: 206316_z_17_Z].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2220188. A short animated film related to the article can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mz2i0UtAWdY.

References

- 1.World Health Organzation . Sexually transmitted infections (STIs); 2021.

- 2.Dehne K, Riedner G.. Sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: the need for adequate health services. Geneva: World Health Organization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ); 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Martin K, Olaru ID, Buwu N, et al. Uptake of and factors associated with testing for sexually transmitted infections in community-based settings among youth in Zimbabwe: a mixed-methods study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(2):122–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torrone EA, Morrison CS, Chen PL, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis among women in sub-Saharan Africa: an individual participant data meta-analysis of 18 HIV prevention studies. PLoS Med. 2018;15(2):e1002511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021: towards ending STIs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathews C, Coetzee N, Zwarenstein M, et al. A systematic review of strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13(5):285–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert M, Hottes TS.. Alternative strategies for partner notification: a missing piece of the puzzle. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(3):174–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogben M, Collins D, Hoots B, et al. Partner services in sexually transmitted disease prevention programs: a review. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(2 Suppl 1):S53–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuwaha F, Kambugu F, Nsubuga PS, et al. Efficacy of patient-delivered partner medication in the treatment of sexual partners in Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(2):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omollo V, Bukusi EA, Kidoguchi L, et al. A pilot evaluation of expedited partner treatment and partner human immunodeficiency virus self-testing among adolescent girls and young women diagnosed with chlamydia trachomatis and neisseria gonorrhoeae in Kisumu, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(10):766–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taleghani S, Joseph-Davey D, West SB, et al. Acceptability and efficacy of partner notification for curable sexually transmitted infections in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int J STD AIDS. 2019;30(3):292–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward H, Bell G.. Partner notification. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;42(6):314–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chitneni P, Beksinska M, Dietrich JJ, et al. Partner notification and treatment outcomes among South African adolescents and young adults diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection via laboratory-based screening. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(7):627–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green H, Taleghani S, Nyemba D, et al. Partner notification and treatment for sexually transmitted infections among pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(13):1282–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalichman SC, Mathews C, Kalichman M, et al. Perceived barriers to partner notification among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients, Cape Town, South Africa. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017;39(2):407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews C, Kalichman MO, Laubscher R, et al. Sexual relationships, intimate partner violence and STI partner notification in Cape Town, South Africa: an observational study. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94(2):144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stangl AL, Sebany M, Kapungu C, et al. Is HIV index testing and partner notification safe for adolescent girls and young women in low- and middle-income countries? J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(S5):e25562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binu W, Marama T, Gerbaba M, et al. Sexual and reproductive health services utilization and associated factors among secondary school students in Nekemte town, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braeken D, Rondinelli I.. Sexual and reproductive health needs of young people: matching needs with systems. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(Suppl 1):S60–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mavodza CV, Busza J, Mackworth-Young CRS, et al. Family planning experiences and needs of young women living with and without HIV accessing an integrated HIV and SRH intervention in Zimbabwe – an exploratory qualitative study. Front Glob Womens Health. 2022;3:781983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ninsiima LR, Chiumia IK, Ndejjo R.. Factors influencing access to and utilisation of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odo AN, Samuel ES, Nwagu EN, et al. Sexual and reproductive health services (SRHS) for adolescents in Enugu state, Nigeria: a mixed methods approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gevers A, Jewkes R, Mathews C, et al. ‘I think it’s about experiencing, like, life’: a qualitative exploration of contemporary adolescent intimate relationships in South Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(10):1125–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jewkes R, Vundule C, Maforah F, et al. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(5):733–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sardinha L, Maheu-Giroux M, Stöckl H, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet. 2022;399(10327):803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zablotska IB, Gray RH, Koenig MA, et al. Alcohol use, intimate partner violence, sexual coercion and HIV among women aged 15–24 in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(2):225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stangl A, Sebany M, Kapunga C, Ricker C, Chard E.. Technical and programmatic considerations for index testing and partner notification for adolescent girls and young women: Technical report. Washington, DC: YouthPower Learning, Making Cents International; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dziva Chikwari C, Dauya E, Bandason T, et al. The impact of community-based integrated HIV and sexual and reproductive health services for youth on population-level HIV viral load and sexually transmitted infections in Zimbabwe: protocol for the CHIEDZA cluster-randomised trial. Wellcome Open Res. 2022;7(54):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tembo M, Mackworth-Young C, Kranzer K, et al. Youth researchers academy: a report on an innovative research training programme for young people in Zimbabwe. BMJ Innov. 2022;8(3):183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devotta K, Woodhall-Melnik J, Pedersen C, et al. Enriching qualitative research by engaging peer interviewers: a case study. Qual Res. 2016;16(6):661–680. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lile J, Richards L.. Youth as interviewers: methods and findings of participatory peer interviews in a youth garden project. J Adolesc Res. 2018;33(4):496–519. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell S, Aggleton P, Lockyer A, et al. Working with Aboriginal young people in sexual health research: a peer research methodology in remote Australia. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(1):16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alam N, Chamot E, Vermund SH, et al. Partner notification for sexually transmitted infections in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferreira A, Young T, Mathews C, et al. Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10(1):1–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD, Simoni JM.. Understanding HIV disclosure: a review and application of the Disclosure Processes Model. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(10):1618–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayfield Arnold E, Flannery RE, Rotheram-Borus D, et al. HIV disclosure among adults living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2008;20(1):80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Obermeyer CM, Baijal P, Pegurri E.. Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: a review. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1011–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, et al. Intimate partner violence and partner notification of sexually transmitted infections among adolescent and young adult family planning clinic patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(6):345–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenfeld EA, Marx J, Terry MA, et al. Intimate partner violence, partner notification, and expedited partner therapy: a qualitative study. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(8):656–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mackworth-Young C, Dringus S, Dauya E, et al. Putting youth at the centre: co-design of a community-based intervention to improve HIV outcomes among youth in Zimbabwe [version 2; peer review: 1 approved]. Wellcome Open Research. 2022;7(53). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mavodza CV, Mackworth-Young CRS, Bandason T, et al. When healthcare providers are supportive, ‘I’d rather not test alone’: exploring uptake and acceptability of HIV self-testing for youth in Zimbabwe – a mixed method study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(9):e25815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mathews C, Lombard C, Kalichman M, et al. Effects of enhanced STI partner notification counselling and provider-assisted partner services on partner referral and the incidence of STI diagnosis in Cape Town, South Africa: randomised controlled trial. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97(1):38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.