Abstract

The distinction between “pregnancy viability” and “fetal viability” indicates the need for care and clarity when using the term “viability” in clinical practice and guidance.

What does it mean for a pregnancy or a fetus to be viable? This question has been passionately pursued in political, legal, religious, philosophical, and scientific conversations. The discussion is also occurring in a medical context, because this is one of our time's more critical health care questions. However, a lack of precision in health care professionals’ use of the term “viable” has contributed to confusion and misinformation regarding pregnancy and has inflamed an already precarious sociopolitical relationship between government and women's reproductive health. The term viable appears to be used variably, imprecisely, and with controversy throughout these different conversations, even in medicine and particularly when courts and legislatures appropriate medical terminology. The possibilities for legislatures to misuse and confuse the terminology are even more perilous, particularly considering proposed “heartbeat bills.” There is no uniform single line of viability that is medically appropriate to apply to all fetuses in all settings, and certainly not one based on gestational age alone. Terminology in medicine should aim to be free from controversial interpretation, which may not be the case for viability. Good medicine requires clear definitions, as evidenced by the need for medical dictionaries. Therefore, the question is better asked as, “Do we have a clear concept of how to use the term ‘viable’ in medicine and, specifically, obstetrics?”

As obstetricians, these questions have been on the authors' minds recently, and we hope to explore these questions with our colleagues. We should specify that we are not asking, “When does life begin?” We have our personal opinions on the answer to this question but do not purport to be professionals in philosophy, religion, cellular biology, or physiology. Instead, we wish to focus on the linguistic terminology and usage in medicine that confuses our colleagues, legislatures, judges, the public, and, most importantly, pregnant people and their families. As it stands, this confusion appears to lead one to ask the question “When does life begin?” even when it is not necessary. The unintended creep of the medical term viability into common parlance and usage has led to confusion, societal tension, and, most importantly, suboptimal care for birthing people.

Even though legal discourse has depended on medicine to define the concept of viability, it is arguable that medicine fails to clarify the confusion, though it is a term that has been used for nearly 200 years. Reference to viability in medical writing goes back at least to 1832, when William Potts Dewees in Compendius System of Midwifery defines viability as, “the capacity to sustain life, rather than the mere signs of this condition.”1,2 In the PubMed archives, we find, in 1841, “Case of a Foetus: Viable at Six Months,” which carries the prescient first sentence, “There is no question in medico-legal science more difficult, and none more interesting and important, than that of the exact limits of utero-gestation, that is, the longest and shortest periods which a child may be carried in the womb, and yet survive.”3

In current times, obstetricians use the terms viability or viable in two contexts:

At or around the time a fetus can survive outside of the uterus. This is often called fetal viability. A viable fetus is contrasted with a fetus that cannot survive outside of the pregnancy.

When an embryo or fetus has a detectable heartbeat. This is generally considered pregnancy viability. A viable pregnancy is contrasted with a failed pregnancy.

The subtle difference in those two usages suggests the importance of precision and specificity in this terminology. In one case—fetal viability—we describe a dependent organism that can possibly survive at that moment outside the pregnancy, though with the help of medical technology. In the other case—pregnancy viability—we describe a condition that has a possibility of producing a liveborn neonate, eventually. Unfortunately, we suspect that practitioners in these areas (obstetricians, midwives, and radiologists, for example) are rarely thinking of the difference between these two usages as they communicate with each other, patients and families, and society.

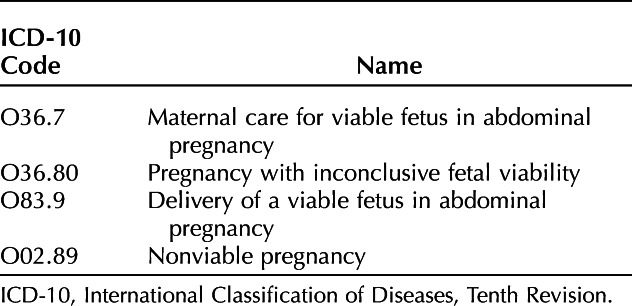

In fact, clinicians are guided systematically to get the distinction between fetal and pregnancy viability wrong. One example is in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes, published by the World Health Organization, used for billing, research, and other health services (Table 1). In particular, the code O36.80X_ is described as, “pregnancy with inconclusive fetal viability.” This code is most often used during an early pregnancy encounter, such as an ultrasonogram, during which the pregnancy’s location and potential are assessed. A code describing fetal viability is applied to a situation to determine pregnancy viability.

Table 1.

Examples of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision Diagnosis Codes Using the Term “Viability”

Failing to be specific in terminology has harmful implications. For example, telling someone being evaluated for early pregnancy that their ultrasonogram shows a viable pregnancy at 8 weeks of gestation can be confusing for someone who has heard the word viability applied in the context of abortion. Another patient with an ectopic pregnancy with ultrasonographically detectable cardiac activity might be led to believe, falsely, that her pregnancy has progressed to the point of newborn survival.

Fetal viability depends largely on fetal organ maturity, which is a function of gestational age. As noted above, the viability of a fetus means having reached such a stage of development as to be capable of living, under normal conditions, outside the pregnancy. Viability exists as a function of obstetric and neonatal medical care, the content and capacity of which vary dramatically across the United States and the world. Notably, the viability of an individual fetus is also influenced by other specific circumstances of that fetus, for instance the presence or absence of structural anomalies, fetal weight, amniotic fluid levels during the pregnancy, and presence of infection.

The terminology of viability cannot be avoided. But we can and must be clearer among ourselves, with society at large, and, above all, with our patients. When using these terms, we should be specific about distinguishing between pregnancy viability and fetal viability. Primarily, we should never let the word viability hang on its own, such as, “Ultrasound demonstrates viability.” Wherever possible, we should use plain language to describe the situation, such as, “Ultrasound demonstrates a 10-week fetus with cardiac activity.”

Words and concepts based on those expressions matter. As clinicians, we must be consistent when discussing the concept of viability. It has been said that there is something about a crisis that gives us clarity. We are currently facing a crisis of demarcation for providing optimal options to patients. Our patients and society look to us for guidance. Clinicians, our patients, the courts, legislatures, and the general public need this clarity. With this call to action for individuals to evaluate their use of the term viable, there is opportunity for professional organizations to clarify this confusion as well. If we do not get this right, how can we expect individuals outside of the medical profession to understand what it means for a pregnancy or fetus to be viable?

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Naomi Rogers, PhD, and Hope Metcalf, JD, for research and editorial assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Mark A. Turrentine, MD, Consultant Editor for Clinical Conundrums and Questioning Clinical Practice for Obstetrics & Gynecology, was not involved in the review for or the decision to publish this article.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D248.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dewees WP. Compendius system of midwifery. Carey & Lea; 1832. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Withycombe SK. Slipped away: pregnancy loss in nineteenth-century America [dissertation]. Accessed August 6, 2023. Available at: https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910104759102121

- 3.Dodd AT. Case of a fœtus: viable at six months. Prov Med Surg J (1840) 1841;2:473–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.s1-2.24.473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]