Abstract

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) is a natural pathogen of the mouse and belongs to the Picornaviridae family. TMEV strains are divided into two subgroups on the basis of their pathogenicity. The first group contains two neurovirulent strains, FA and GDVII, which cause a rapid fatal encephalitis. The second group includes persistent strains, like DA and BeAn, which produce a biphasic neurological disease in susceptible mice. Persistence of these viruses in the white matter of the spinal cord leads to chronic inflammatory demyelination. L929 cells, which are susceptible to TMEV infection, were subjected to physicochemical mutagenesis. Cellular clones that became resistant to TMEV infection were selected by viral infection. Three such mutants resistant to strain GDVII were characterized to determine the step of the virus cycle that was inhibited. The mutation present in one of these mutant cell lines inhibited, by more than 1,000-fold, the entry of strain GDVII but hardly decreased infection by strain DA. In the two other cellular mutants, replication of the viral genome was slowed down. Interestingly, one of these mutant cell lines resisted infection by both the persistent and neurovirulent strains while the second cell line resisted infection by strain GDVII but remained susceptible to the persistent virus. These results show that although they have 95% identity at the amino acid sequence level, neurovirulent and persistent viruses use partly distinct pathways for both entry into cells and genome replication.

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) is a naturally occurring pathogen of the mouse belonging to the Picornaviridae family. It infects the gastrointestinal tract and spreads in the mouse population by the fecal-oral route. Like poliovirus, TMEV is highly neurotropic and can reach the central nervous system of the mouse, where it induces neurological diseases in some individuals (32). The various TMEV isolates are generally classified into two subgroups on the basis of the pathology they induce in the central nervous system of susceptible mice (for reviews, see references 4, 25, and 28).

The first subgroup contains two highly neurovirulent strains, GDVII and FA, that cause an acute lethal polioencephalomyelitis. These viruses mainly replicate in the neurons of the brain and kill the mice in a matter of days. The second subgroup contains persistent strains, including strains DA and BeAn, which provoke a biphasic disease (16). The early disease is a mild encephalitis during which the virus essentially infects some neurons of the brain. In susceptible mice, the virus then migrates to the spinal cord, first to the gray and then to the white matter, where it causes a persistent infection. At this stage (late disease), replication of the virus is detected mainly in macrophages or microglial cells, in oligodendrocytes, and, to a lesser extent, in astrocytes (1, 3, 17). Persistence of the virus is closely associated with a strong inflammatory response and with lesions of primary demyelination reminiscent of those observed in multiple sclerosis.

Although they cause markedly different pathologic effects, neurovirulent and persistent strains of TMEV are closely related and have 93 to 95% identity at the amino acid sequence level (23, 26, 27). Analysis of chimeric viruses constructed by exchanging the capsids of neurovirulent and persistent virus strains revealed that the capsid bears the main determinants of persistence and neurovirulence (5, 9, 22). This suggests that some differences in the capsid structure of the two groups of viruses might govern the recognition of alternative receptors or coreceptors and might be responsible for the difference in cellular tropism, with the GDVII virus being more neurotropic and the persistent strains being more glial-cell tropic (2, 13). The capsid structures of three TMEV isolates have been determined by X-ray crystallography (10, 19, 20). Capsids from persistent and neurovirulent strains differ mainly in loops exposed at the surface. The major structural differences are found in the CD loop of VP1 and in the EF loop of VP2. Interestingly, these surface-exposed loops, which might interact with the cellular receptor, precisely correspond to neutralizing epitopes (29, 35) and were found to influence the tropism of the virus in vitro as well as persistence in the central nervous system (11, 12, 14). Little is known about the receptor of TMEV. Both persistent and neurovirulent viruses were found to bind to a 34-kDa glycoprotein, which is abundant in neurons and in BHK-21 cells, the latter cells being used to grow the virus in vitro (15). However, competition experiments suggested that the two subgroups of viruses might bind to the same molecule but in different ways. Accordingly, it was shown recently that sialyllactose competed for entry with the persistent BeAn virus but not with the neurovirulent GDVII virus (34). A gap formed by the CD loop of VP1 and the EF loop of VP2 at the surface of the capsid of persistent strains would allow these strains to bind sialyloligosaccharides present on the receptor molecule. Neurovirulent strains would bind to the protein moiety of the receptor.

We obtained and characterized a series of L929 cell mutants resistant to infection by the highly cytopathic GDVII virus. Cell mutants fell into three subgroups according to their resistance to DA, GDVII, and capsid-swapping recombinant viruses. Further characterization of one cellular mutant from each group revealed that the requirement for cellular factors differed both for entry and for replication of DA and GDVII viruses in L929 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

L929 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL), 100 IU of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml and 100 mM sodium pyruvate. BHK-21 cells were cultured in Glasgow’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum (Gibco-BRL), 100 IU of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 130 g of tryptose phosphate broth (Gibco-BRL) per liter.

Viruses.

The DA and GDVII strains are prototypes of persistent and neurovirulent TMEV strains, respectively. The DA virus used in this study is the molecular clone DA1 (24). Strains R2 and R3 are capsid-swapping recombinants of strains DA and GDVII. These recombinants were constructed previously (22) by exchanging an AatII restriction fragment comprising 30 codons of region L, the entire capsid-coding region, and the 27 first codons of protein 2A. R2 is the GDVII derivative bearing the capsid of DA, and R3 is the DA derivative carrying the capsid of GDVII. Strain KJ6 is a DA derivative containing 5 amino acid substitutions in the capsid that highly enhance its infectivity for L929 cells (14). KJ13 is a recombinant virus that is similar to R2 but contains the capsid of KJ6 instead of that of DA. Mengovirus is a picornavirus related to TMEV. TMEV and mengovirus belong to the Cardiovirus genus and have about 60% identity at the amino acid sequence level.

Construction of plasmid pKJ13.

Plasmid pKJ13 was constructed by replacing the 2,251-bp BsiWI-NdeI restriction fragment of plasmid pTMR2 with the corresponding fragment of pKJ6. This fragment contains all the mutations responsible for adaptation of the virus to grow on L929 cells. pKJ13 thus contains the cDNA of a virus (KJ13) equivalent to virus R2 but adapted to grow on L929 cells.

Virus production.

Stocks of DA, GDVII, R2, R3, KJ6, KJ13, and mengovirus were produced, as described previously (24), by transfection of BHK-21 cells with the genomic RNA transcribed in vitro from plasmids carrying the corresponding cDNAs: pTMDA1 (21, 24), pTMGDVII (31), pTMR2 (22), pTMR3 (22), pKJ6 (14), pKJ13 (this work), and pMC24 (originally called pMC16.1) (7), respectively.

Culture supernatants were collected after completion of the cytopathic effect (generally between 48 and 72 h after transfection). The culture supernatant was frozen, thawed, and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was then collected and stored in aliquots at −70°C. Virus titers were determined by a standard plaque assay in BHK-21 cells.

Cell mutagenesis.

For chemical mutagenesis, cells were cultured in Earle’s medium in the presence of 0.25 to 7.5 μg of N-methyl-N′-nitro-n-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) (Sigma) per ml for 8 to 72 h (6, 33). The cells were then washed and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium until they reached confluence and were subsequently passaged once prior to the addition of virus for selection of virus-resistant cells. For physical mutagenesis, the cells were irradiated with a gamma irradiator at 300 to 900 rads. They were then grown to confluence and passaged once before the addition of virus for selection.

Resistant cells were passaged 3 or 4 times in the presence of virus and then about 20 times in the absence of virus. The cells were subsequently cloned once or twice.

Transfection of cells.

BHK-21 or L929 cell monolayers were transfected by electroporation with 5 to 20 μg of viral RNA, as described previously (14). The cells were then resuspended in culture medium and split into several 6-cm petri dishes for further RNA extraction or in 24-well plates for immunocytochemistry.

Dot blot hybridization.

At 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection, total RNA was extracted from transfected cells and the amount of viral RNA was monitored by dot blot hybridization as described previously (24).

Immunocytochemistry.

Infected or transfected monolayers of L929 cells were fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were then permeabilized for 5 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 and treated for 5 min with 0.3% H2O2 to inactivate endogenous peroxidases. Viral infection was detected with the F12B3 anti-VP1 monoclonal antibody (kindly provided by Michel Brahic), which was then detected by using a secondary biotinylated anti-mouse antibody and a streptavidin-peroxydase complex (DAKO LSAB 2 kit). Diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogenic substrate for peroxidase.

RESULTS

Selection of L929 cell mutants resistant to strain GDVII.

L929 cells were subjected to MNNG and/or gamma-ray mutagenesis. Cell mutants resistant to TMEV were selected by infection of the cultures with the neurovirulent and highly cytopathic GDVII strain. Emerging cell clones were passaged 3 or 4 times in the presence of the virus and then about 20 times without virus selection. The mutant cells obtained were cloned once or twice and then tested again for their resistance to the infection by GDVII. At this stage, about half of the mutant cells (11 of 24) had reverted to virus susceptibility for unknown reasons. Two cell lines were also discarded because they turned out to be persistently infected by the virus. A total of 11 cell lines resistant to virus GDVII were obtained and further characterized. Among these cell lines, four (L929#3, L929#7, L929#8, and L929#10) were fully resistant to infections performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) higher than 10 PFU per cell. Seven mutant cell lines (L929#1, L929#5, L929#6, L929#17, L929#18, L929#20, and L929#25) resisted the infection only when lower MOIs of GDVII virus were used.

Susceptibility of mutant cells to infection by DA and recombinant viruses.

We first examined whether the acquired resistance of the cells to GDVII was also directed toward DA. Surprisingly, the majority of cells (9 of 11) resistant to GDVII turned out to be susceptible to DA (Table 1). We next tested the susceptibility of the cellular clones to the infection by the recombinant viruses R2 (capsid of DA in a GDVII background) and R3 (capsid of GDVII in a DA background) (see Materials and Methods). The 11 cellular clones could be classified into three subgroups according to their relative resistance to the different viruses used.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of wild-type and mutant L929 cells to GDVII, DA, R3, and R2

| Cell line | Susceptibilitya of cell line to:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDVII | DA | R3 (capsid GDVII) | R2 (capsid DA) | |

| L929 | S | S | S | S |

| Group I | R | S | R | S |

| Group II | R* | S | S | R* |

| Group III | R* | R* | S | R* |

S, susceptibility; R, resistance; R*, resistance to a MOI of <10 PFU/cell.

Group I (L929#3, L929#7, L929#8, and L929#10) contained cell lines resistant to GDVII and R3 (GDVII capsid) and susceptible to DA and R2. Since resistance was directed toward the GDVII capsid, these mutants were likely to be mutated in a function required for virus entry or assembly.

The cell mutants classified in group II (L929#1, L929#5, L929#6, L929#17, and L929#18) were resistant to GDVII and R2 and susceptible to DA and R3. In this case, resistance was directed toward the replication functions of GDVII. Here, we understand “replication” in a broad sense, as any step of the virus life cycle between entry and release.

The third group of mutants (L929#20 and L929#25) contained cell lines resistant to low doses of both DA and GDVII. For unknown reasons, these mutants were still readily infected by R3 (GDVII capsid in a DA background), even when infections were performed at a MOI as low as 0.1 PFU per cell. This might be related to the fact that R2 and R3 are not precise capsid exchange recombinants but contain hybrid leader and 2A regions.

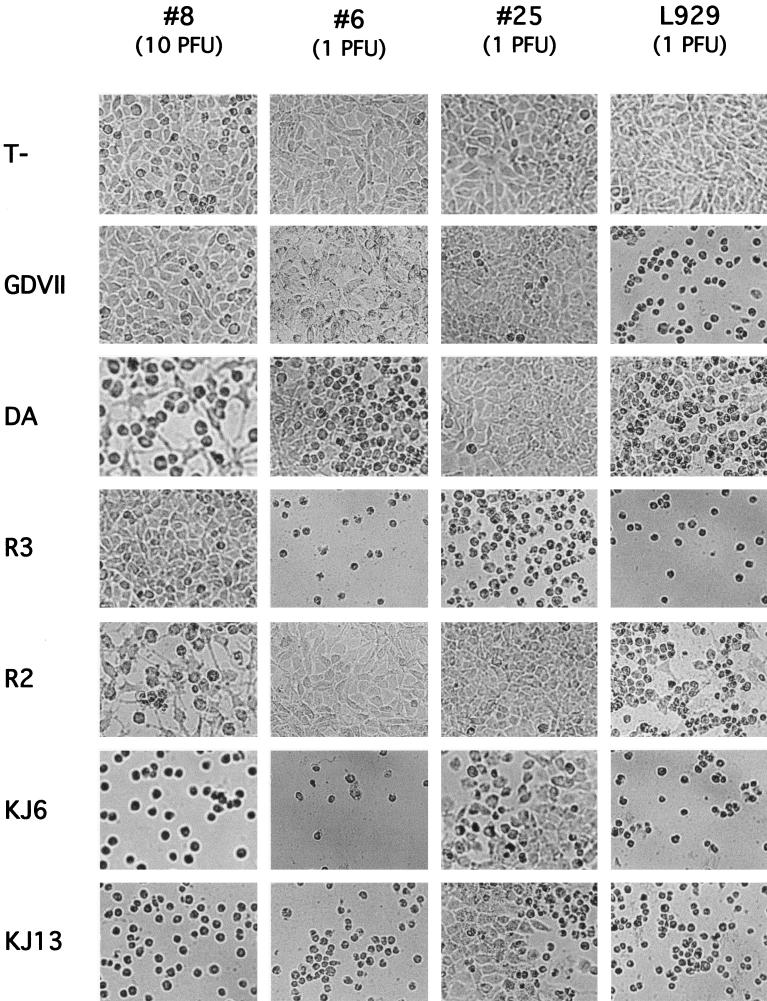

One mutant representative of each group was selected for further characterization: L929#8 (group I), L929#6 (group II), and L929#25 (group III). First, the infection experiments were repeated. Since the capsid of DA confers a low infectivity for L929 cells, KJ6 and KJ13 were added to the series to confirm the data obtained with DA and R2, respectively (Fig. 1). KJ6 is a derivative of DA that contains 5 amino acid mutations in the capsid, enhancing the infectivity for L929 cells. KJ13 is a recombinant virus containing the capsid of KJ6 in a GDVII background (see Materials and Methods). The mutant cells were also tested for susceptibility to mengovirus, a cardiovirus related to TMEV. The results of the infections are shown in Fig. 1. The three mutant cell lines conserved susceptibility to mengovirus (data not shown). As expected from their adaptation to L929 cells, cytopathic effect appeared much faster with KJ6 and KJ13 than with their counterparts DA and R2, but the overall pattern of resistance or susceptibility of the mutant cells was conserved. The most noticeable differences were that KJ6 and KJ13 progressively killed L929#25 cells although DA and R2 did not and that KJ13 killed L929#6 cultures although R2 did not. This could be explained by the very high efficiency of entry of these viruses into L929 cells. Similarly, L929#25 and L929#6 cells could be infected by GDVII when high MOIs were used.

FIG. 1.

Infection of wild-type and mutant L929 cells. Mutant or wild-type cell monolayers were infected at a MOI of 1 or 10 PFU per cell with DA, GDVII, R2, R3, KJ6, or KJ13 or were left uninfected (T−). Cytopathic effect was monitored by microscopy. Pictures are from cells infected for 72 h at the indicated MOI.

Replication of the GDVII genome in mutant cells.

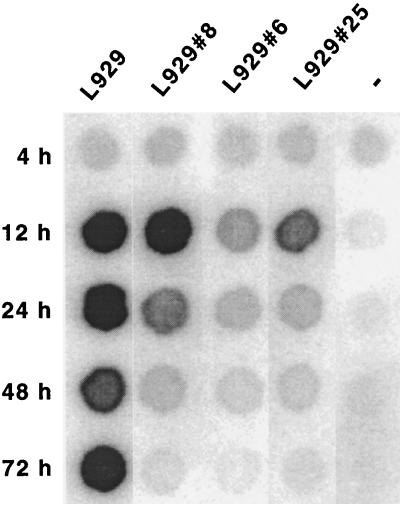

To determine whether replication or entry of GDVII was impaired in the three mutant cell lines described above, the viral RNA was transcribed in vitro from plasmid pTMGDVII and introduced into the cells by electroporation. Viral genome replication was followed by dot blot hybridization. Replication levels were estimated 12 h after transfection, when viral RNA from secondary infections cannot be detected. Later times (24, 48, and 72 h after transfection) were also investigated to monitor the evolution of the infection. At these times, the hybridization signals reflect a combination of replication and propagation efficiencies. Three independent experiments were performed and yielded consistent conclusions, although some quantitative differences were found. The results of a typical experiment are shown in Fig. 2. At 12 h after transfection, the genome of virus GDVII replicated as well in L929#8 cells as in wild-type cells, confirming that resistance of these cells to viral infection was not due to the inhibition of virus replication. In contrast, the level of replication of GDVII in L929#6 and L929#25 cells was decreased compared to replication in wild-type L929 cells. The lower signal for L929#6 and L929#25 cells was not a mere consequence of a lower transfection efficiency of these mutant cell lines since transfection efficiencies were less than twofold lower for the mutant than for the wild-type cells (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Replication of the genome of GDVII in wild-type and mutant L929 cells. Wild-type or mutant L929 cells were transfected by electroporation with in vitro-transcribed GDVII RNA. Total RNA was extracted from cells 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection. Viral RNA was detected by dot blot hybridization. At 12 h after transfection, RNA from secondary infections is not yet detected, and the amount of viral RNA thus reflects the replication efficiency. At later times, the hybridization signal also depends on the rate of propagation of the virus to nontransfected cells.

TABLE 2.

Transfection efficiency of the mutant cell linesa

| Cell line | Relative transfection efficiency (%)b |

|---|---|

| L929 | 100 |

| L929#8 | 72.7 ± 27.0 |

| L929#6 | 54.8 ± 26.4 |

| L929#25 | 57.1 ± 24.3 |

The luciferase-expressing plasmid, pSV2-luc, was transfected in the various cell lines by electroporation under the conditions used for RNA transfections.

The transfection efficiency is expressed as the luciferase activity normalized to that expressed by the wild-type cells (set at 100%). The data show the means and standard deviations of the results from five experiments involving various amounts of DNA.

Entry of GDVII and DA viruses in mutant cell lines.

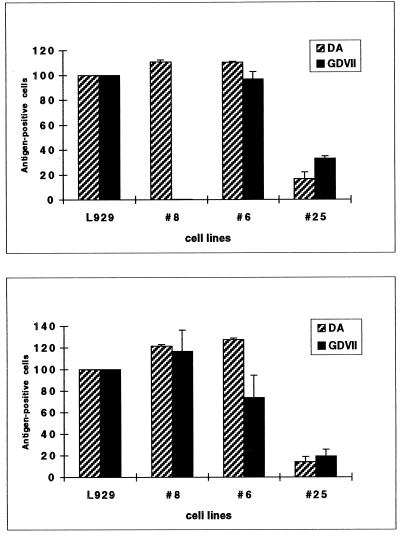

To analyze the entry of the virus into the mutant cell lines, we compared the proportion of cells replicating the virus after infection of the cells with the virus and after transfection of the cells with viral genomic RNA. Cells supporting virus replication were detected by immunocytochemistry 10 h after transfection or infection, to avoid the detection of secondary infections. This experiment was done for both DA and GDVII (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of virus entry into mutant cell lines by comparison of the transfection (bottom) and infection (top) efficiencies. Relative rates of viral antigen-positive L929 and mutant cells, after either transfection with GDVII or DA genomic RNA (bottom) or infection with 10 PFU of GDVII and DA per ml (top), are shown. The rate of positive wild-type cells was taken as 100%.

(i) L929#8.

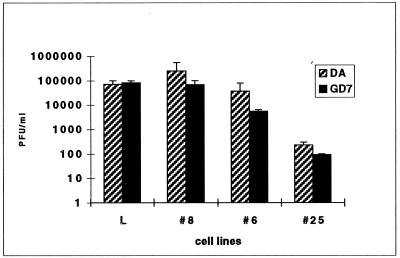

After infection with GDVII, about 1,000 to 10,000 times fewer L929#8 cells than wild-type L929 cells were positive for viral antigen. When cells were transfected with the viral RNA to bypass the entry step, as many cells were positive for L929#8 cells as for the wild-type control. These data nicely fit the data from infection and dot-blot experiments and show that the mutation present in L929#8 cells inhibits the entry of virus GDVII. Interestingly, these mutant cells were still readily infected by DA. On several occasions, however, the infection of L929#8 cells by virus DA also appeared to be slightly slower than the infection of wild-type cells. To make sure that the entry step was the only step inhibited in L929#8 cells, we measured the amount of infectious virions produced 14 h after transfection of the viral RNA into the cells (Fig. 4). Virus production by mutant cells was comparable to that by wild-type cells, demonstrating that neither replication nor virus assembly and release was inhibited in the L929#8 mutant cell line.

FIG. 4.

Production of infectious viral particles by mutant cells transfected with viral RNA. The amount of virus produced in the supernatant of transfected cells, 14 h after transfection, was measured by a plaque assay.

(ii) L929#6.

Infection of L929#6 cells, monitored by immunocytochemistry, appeared to be as efficient as infection of L929 cells for both DA and GDVII. After transfection, the number of L929#6 cells found to contain GDVII antigen was slightly although not significantly decreased. The amount of virus produced in the supernatant of transfected cells was also smaller in L929#6 cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. 4). This effect was slightly more pronounced for GDVII than for DA. Taken together, the data indicate that replication of GDVII and, to a lesser extent, of DA is reduced in L929#6 cells. This relatively small difference in the impact on the replication level is nevertheless sufficient to render L929#6 cells resistant to GDVII but not to DA (when considering overall cytopathic effect in the culture).

(iii) L929#25.

Compared with wild-type cells, detection of viral antigen in L929#25 cells was decreased by about 80% for both viruses after either infection or transfection. This suggests that in the majority of infected or transfected cells, viral replication is too low to allow viral antigen detection. Accordingly, there was a nearly 1,000-fold drop in virus production by cells transfected with the viral genome (Fig. 4). These data show that one of the steps of the virus replication cycle, occurring between virus entry and release, is inhibited in this mutant cell line.

Selection of L929 mutant cells resistant to KJ6.

Series of chemical and irradiation mutagenesis experiments were performed in an attempt to isolate L929 cells resistant to the entry of the DA-like subgroup of viruses, as was done for GDVII. KJ6 was used for this purpose instead of DA, because the latter virus did not propagate efficiently enough in L929 cells to be used as a strong selective agent. In spite of a number of mutagenesis trials, no resistant clone could be isolated. During the process of selection, a few clones grew transiently in the presence of virus KJ6. These clones turned out to resist infection by virus GDVII as well. However, all of these clones were finally overtaken by viral infection.

DISCUSSION

We obtained a series of mutant cell lines resistant to infection by the GDVII strain of TMEV. The resistance of four of these mutant cell lines was found to be directed toward the capsid of GDVII and could thus result from the inhibition of virus entry or of capsid assembly. However, we recently found that the capsid-encoding region of cardioviruses also contains an essential replication signal (18). Thus resistance to the capsid of GDVII could also result from the absence of a factor required for virus replication. Characterization of one of these cell lines (L929#8) demonstrated that resistance in that cell line correlated with a defect in virus entry rather than with a defect in replication. Indeed, the genome of virus GDVII replicated as well in mutant cells as in wild-type cells. Moreover, infection of mutant cells by GDVII was inhibited whereas transfection of the cells with viral RNA resulted in the production of wild-type levels of infectious particles. Although it is clear that virus entry is the step affected in this mutant, binding experiments performed by flow cytometry failed to reveal any difference in GDVII binding to wild-type and mutant cells.

Interestingly, L929#8 cells conserved susceptibility to the infection by DA. The entry of GDVII was decreased by more than 1,000-fold, while that of DA was only slightly affected. This clearly shows an important functional difference between neurovirulent and persistent viruses for entry into cells. Similarly, we previously observed a higher degree of resistance of nonactivated RAW264.7 macrophages to GDVII than to DA (30).

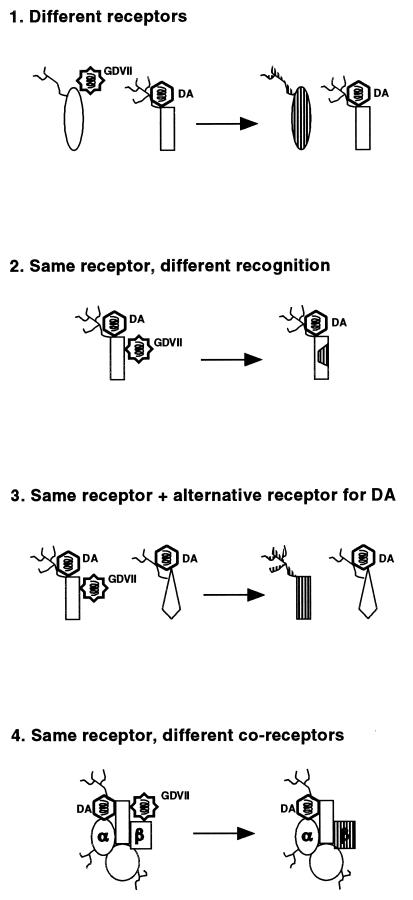

Several possibilities (which are not all mutually exclusive) might account for this difference in entry observed for persistent and neurovirulent viruses (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Binding of DA and GDVII to the receptor: hypotheses accounting for the differential entry of viruses DA and GDVII into L929 cells. The receptor is represented with a possible glycosylation ( ). α and β identify the putative coreceptor molecules. Left side, wild-type L929 cells; right side, L929#8 cells. Mutated parts of the receptor are dashed.

). α and β identify the putative coreceptor molecules. Left side, wild-type L929 cells; right side, L929#8 cells. Mutated parts of the receptor are dashed.

(i) DA and GDVII might use a different receptor to infect L929 cells. In this case, the mutation present in L929#8 cells would have affected solely the GDVII receptor. However, previous studies by Fotiadis et al. (8) and by Kilpatrick and Lipton (15) indicated that both viruses could bind to the same 34-kDa glycoprotein.

(ii) DA and GDVII might bind to the same receptor but in a different manner. As proposed by Fotiadis et al. (8) and by Zhou et al. (34), persistent strains would then recognize the sialyloligosaccharide moiety of the receptor while neurovirulent strains would bind only to the protein moiety. In this hypothesis, the receptor molecule of L929#8 cells would have been damaged precisely at the site recognized by GDVII but not by DA. It is surprising, in the hypothesis of a common receptor, that none of the three other mutants found to resist viruses harboring the GDVII capsid (group I) resisted the infection by viruses containing the DA capsid.

(iii) DA and GDVII might bind to the same receptor, but DA might also be able to use an alternative receptor for entry into L929 cells. This would explain the slight inhibition of DA entry into the mutant cells. It would also account for the fact that we were unable to select any cell mutant fully resistant to KJ6.

(iv) GDVII and DA might use a common receptor but alternative coreceptors. The coreceptor hypothesis could explain why we were unable to detect a clear difference in binding of GDVII to wild-type and mutant L929 cells (data not shown). We believe that there is a family of polymorphic coreceptor molecules that modulate infection efficiency. In addition to being different for different strains of viruses, these coreceptors would be polymorphic on different cell types, explaining the selection of capsid mutations during adaptation of the virus to growth on different cell lines (14). Thus, the relative affinity of a given capsid for the receptor-coreceptor complex present on a given cell type would determine the efficiency of virus entry into that cell and thus the overall tropism of the virus. A similar polymorphism at the level of the receptor molecule (case 1) could also account for all these observations.

Several cell mutants were found in which replication of the viral genome was decreased. Unlike the mutants affected in virus entry, replication mutants were susceptible to infections performed at high MOI. As with virus entry, replication of DA and GDVII also appeared to be differentially affected in some of the cell mutants. It is quite surprising that viruses with about 95% identity in their amino acid sequence would have at least some different host factor requirements for both entry and replication in a single cell line.

The isolation of cell mutants turned out to be a powerful strategy for the detection of subtle differences in the life cycles of related viruses. Further characterization of the mutants could assist the identification of host factors required for entry and replication of the virus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Anne Gustin, Aline Van Pel, and Thierry Boon, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Brussels, Belgium, for their expertise and help in setting up the mutagenesis experiments. Ann Palmenberg kindly provided the cDNA clone of mengovirus. We also thank Chloë Shaw-Jackson and Michel Brahic for critical reading of the manuscript and for many helpful scientific discussions.

K.J. is a fellow from the Belgian FRIA (Fonds pour la Recherche dans l’Industrie et l’Agriculture). T.M. is Senior Research associate with the FNRS (Belgian Fund for Scientific Research). This work was supported by convention 3.4573.94F of the FRSM, crédit aux chercheurs FNRS 1.5.185.96F, by the French Association pour la Recherche sur la Sclérose en Plaques (ARSEP), and by the Fonds de Développement Scientifique (FDS) of the University of Louvain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aubert C, Chamorro M, Brahic M. Identification of Theiler’s virus infected cells in the central nervous system of the mouse during demyelinating disease. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubert C, Brahic M. Early infection of the central nervous system by the GDVII and DA strains of Theiler’s virus. J Virol. 1995;69:3197–3200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3197-3200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahic M, Stroop W G, Baringer J R. Theiler’s virus persists in glial cells during demyelinating disease. Cell. 1981;26:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahic M, Bureau J-F, McAllister A. Mini-review: genetic determinants of the demyelinating disease caused by Theiler’s virus. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90001-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calenoff M A, Faaberg K S, Lipton H L. Genomic regions of neurovirulence and attenuation in Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:978–982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffino P, Scharff M D. Rate of somatic mutation in immunoglobulin production by mouse myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:219–223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duke G M, Palmenberg A C. Cloning and synthesis of infectious cardiovirus RNAs containing short, discrete poly(C) tracts. J Virol. 1989;63:1822–1826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1822-1826.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fotiadis C, Kilpatrick D K, Lipton H L. Comparison of the binding characteristics to BHK-21 cells of viruses representing the two Theiler’s virus neurovirulence groups. Virology. 1991;182:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu J, Stein S, Rosenstein L, Bodwell T, Routbort M, Semler B L, Roos R P. Neurovirulence determinants of genetically engineered Theiler viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4125–4129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant R A, Filman D J, Fujinami R S, Icenogle J P, Hogle J M. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2061–2065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarousse N, Grant R A, Hogle J M, Zhang L, Senkowski A, Roos R P, Michiels T, Brahic M, McAllister A. A single amino acid change determines persistence of a chimeric Theiler’s virus. J Virol. 1994;68:3364–3368. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3364-3368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarousse N, Martinat C, Syan S, Brahic M, McAllister A. Role of VP2 amino acid 141 in tropism of Theiler’s virus within the central nervous system. J Virol. 1996;70:8213–8217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8213-8217.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarousse N, Syan S, Martinat C, Brahic M. The neurovirulence of the DA and GDVII strains of Theiler’s virus correlates with their ability to infect cultured neurons. J Virol. 1998;72:7213–7220. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7213-7220.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jnaoui K, Michiels T. Adaptation of Theiler’s virus to L929 cells: mutations in the putative receptor binding site on the capsid map to neutralization sites and modulate viral persistence. Virology. 1998;244:397–404. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilpatrick D R, Lipton H L. Predominant binding of Theiler’s viruses to a 34-kilodalton receptor protein on susceptible cell lines. J Virol. 1991;65:5244–5249. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5244-5249.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipton H L. Theiler’s virus infection in mice: an unusual biphasic disease process leading to demyelination. Infect Immun. 1975;11:1147–1155. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1147-1155.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipton H L, Twaddle G, Jelachich M L. The predominant virus antigen burden is present in macrophages in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Virol. 1995;69:2525–2533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2525-2533.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lobert, P.-E., N. Escriou, J. Ruelle, and T. Michiels. A coding RNA sequence acts as a replication signal in cardioviruses. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Luo M, He C, Toth K S, Zhang C X, Lipton H L. Three-dimensional structure of Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus (BeAn strain) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2409–2413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo M, Toth K S, Zhou L, Pritchard A, Lipton H L. The structure of a highly virulent Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (GDVII) and implications for determinants of viral persistence. Virology. 1996;220:246–250. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAllister A, Tangy F, Aubert C, Brahic M. Molecular cloning of the complete genome of Theiler’s virus, strain DA, and production of infectious transcripts. Microb Pathog. 1989;7:381–388. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAllister A, Tangy F, Aubert C, Brahic M. Genetic mapping of the ability of Theiler’s virus to persist and demyelinate. J Virol. 1990;64:4252–4257. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4252-4257.1990. . (Author’s correction, J. Virol. 67:2427, 1993.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michiels T, Jarousse N, Brahic M. Analysis of the leader and capsid coding regions of persistent and neurovirulent strains of Theiler’s virus. Virology. 1995;214:550–558. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michiels T, Dejong V, Rodrigus R, Shaw-Jackson C. Protein 2A is not required for Theiler’s virus replication. J Virol. 1997;71:9549–9556. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9549-9556.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monteyne P, Bureau J-F, Brahic M. The infection of mouse by Theiler’s virus: from genetics to immunology. Immunol Rev. 1997;159:163–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohara Y, Stein S, Fu J, Stillman L, Klaman L, Roos R P. Molecular cloning and sequence determination of DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis viruses. Virology. 1988;164:245–255. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90642-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pevear D C, Borkowski J, Calenoff M, Oh C K, Ostrowski B, Lipton H L. Insights into Theiler’s virus neurovirulence based on a genomic comparison of the neurovirulent GDVII and less virulent BeAn strains. Virology. 1988;165:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90652-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez M, Oleszak E, Leibowitz J. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis: a model of demyelination and persistence of virus. Crit Rev Immunol. 1987;7:325–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato S, Zhang L, Kim J, Jakob J, Grant R A, Wollmann R, Roos R P. A neutralization site of DA strain of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus important for disease phenotype. Virology. 1996;226:327–337. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw-Jackson C, Michiels T. Infection of macrophages by Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus is highly dependent on their activation or differentiation state. J Virol. 1997;71:8864–8867. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8864-8867.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tangy F, McAllister A, Brahic M. Molecular cloning of the complete genome of strain GDVII of Theiler’s virus and production of infectious transcripts. J Virol. 1989;63:1101–1106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1101-1106.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theiler M, Gard S. Encephalomyelitis of mice. 1. Characteristics and pathogenesis of the virus. J Exp Med. 1940;72:49–67. doi: 10.1084/jem.72.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Pel A, Vessière F, Boon T. Protection against two spontaneous mouse leukemias conferred by immunogenic variants obtained by mutagenesis. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1992–2001. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.6.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou L, Lin X, Green T J, Lipton H L, Luo M. Role of sialyloligosaccharide binding in Theiler’s virus persistence. J Virol. 1997;71:9701–9712. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9701-9712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zurbriggen A, Hogle J M, Fujinami R. Alteration of amino acid 101 within capsid protein VP-1 changes the pathogenicity of Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2037–2049. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]