Abstract

PURPOSE

Patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers may experience significant reduction in their quality of life and often rely on family and unpaid caregivers for assistance after surgery. However, as caregivers are not systematically identified, little is known about the nature, difficulty, and personal demands of assistance they provide. We aim to assess the frequency and difficulty of specific assistance caregivers provide and identify potential interventions that could alleviate the caregiving demands.

METHODS

This was a prospective, multi-institutional study of caregivers accompanying patients with periampullary and pancreatic cancer at their 1-month postpancreatectomy office visit. An instrument that drew heavily on the National Study of Caregiving was administered to caregivers.

RESULTS

Of 240 caregivers, more than half (58.3%) of caregivers were the patients' spouse, a quarter (25.8%) were daughters or sons, 12.9% other relatives, and 2.9% nonrelatives. Caregivers least frequently provided assistance with transportation (14.6% every day) and most frequently provided assistance with housework (65.0% every day, P = .003) and diet (56.5% every day, P = .004). Caregivers reported the least difficulty helping patients with exercise (1.5% somewhat difficult). Caregivers reported significantly more difficulty with assisting with housework (14.5% somewhat difficult, P < .001) and diet (14.9% somewhat difficult, P < .001). Caregivers identified the immediate postpancreatectomy and early discharge periods as the most stressful phases. They also reported having received very little information about available services that could have supported their efforts.

CONCLUSION

Caregivers of patients with periampullary or pancreatic cancer provide considerable assistance in the postoperative period and many reported difficulty in assisting with housework and diet. Work is needed to better prepare and support caregivers to better enable them to adequately care for patients with pancreas and periampullary cancer.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of pancreatic and periampullary cancer has been on the rise, with pancreatic cancer projected to be the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States in 2021.1 Although significant advances have been made in the efficacy of chemotherapeutics for the disease, surgical resection remains the only treatment that provides patients the possibility of long-term survival.2 However, surgical resection is associated with significant morbidity that can decondition patients and often lead to significant weight loss for several months postoperatively.3,4 Additionally, any pancreatic resection has a significant impact on patients' quality of life. Part of this may be caused by postoperative exocrine insufficiency, manifesting as diarrhea, indigestion, bloating, need for enzyme replacement therapy, and endocrine insufficiency, such as diabetes with the need for insulin.5-8 These factors aggravate the already diminished quality of life that is present at the time of preoperative surgical evaluation.9 Patients are forced to make acute adjustments to their physical activities and diets to accommodate their postoperative gastrointestinal anatomy and function.

CONTEXT

Key Objectives

What is the nature, frequency, and difficulty associated with the care that family and other unpaid caregivers provide patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers who have undergone a pancreatectomy?

Knowledge Generated

Caregivers most frequently assisted with housework and diet and reported the greatest amount of difficulty with these. Caregivers identified the immediate postpancreatectomy and early discharge periods as most stressful and wanted more information on postoperative expectations and better preparation as a caregiver.

Relevance

This study highlights room for improvement in better preparing and supporting caregivers to adequately care for patients with pancreas and periampullary cancer.

For these reasons, as well as the often advanced age, and frailty of patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers, postpancreatectomy patients often rely on family and unpaid caregivers for support after hospital discharge.10 However, surgical research has not focused on out-of-hospital postoperative care and logistics. Specifically, caregivers are not systematically identified or routinely assessed in most cancer care delivery settings.11 Little is known about who caregivers are, as well as the nature and degree of assistance that they provide patients after pancreatectomy. The aim of this study was to identify the demographic characteristics of family and unpaid caregivers for patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers after pancreatectomy. Additionally, this study assesses the frequency and difficulty of specific help provided by caregivers and identifies potential interventions that may alleviate the demands of caregiving.

METHODS

This prospective, tri-institutional study was conducted from January 2019 to January 2020. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of all participating institutions. The study design and results were reported in concordance with the Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (Data Supplement [Table 1], online only).12 The surgery clinic schedule was screened by the clinic's charge nurse for patients who had undergone surgical resection for pancreatic or periampullary cancer and were scheduled for their 1-month postoperative clinic appointment. Eligible patients met with research staff before their scheduled appointment to be introduced to the study and its procedures and were invited to participate. A caregiver was defined as a person older than 18 years who accompanied the patient to the postoperative visit and was identified by the patient as their primary caregiver. In accordance with the IRB's protocol, informed consent was obtained first from the patient and then from the caregiver. Once patient consent was obtained, caregivers were then given an iPad to complete the survey on a REDCap platform in a private room separate from the patient.13 Caregivers were also given the option to complete the survey online at a later time via an emailed link. Providers were blinded to patients' and caregivers' participation or lack thereof during the clinic visit.

Instrument and Data Sources

An instrument was developed that included comprehensive measures of caregiver demographics, caregiving circumstances, and experiences. The instrument drew heavily on widely tested and validated measures of caregiver experiences from the National Study of Caregiving.14-16 The frequency of specific types of assistance provided by caregivers was assessed on a 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot) Likert-type scale. Caregivers assessed the difficulty of each type of assistance on a 1 (not at all difficult) to 4 (very difficult) Likert-type scale. Additional instruments included the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2),17 Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item (GAD-2),18,19 and Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine items.20 The PHQ-2 was designed as a depression screening tool and uses a 0-6 scale, where a score of 3 or greater serves as a validated cutoff for detection of depression. The GAD-2 screens for anxiety and is similarly scored on a 0-6 scale with a cutoff score of 3. Respite care was defined as paid services for patient assistance so that the caregiver could take time off. Paid help was defined as a service to perform household chores and personal care. Two open-ended questions were added for qualitative analysis: one question regarding the most stressful time for the caregiver during the patient's treatment and the second asking what information or service would have been most helpful to the caregiver. The goal of the open-ended questions was to elicit input and experiences that were not assessed in the closed-ended, structured questions. This decision was guided by the dearth of preexisting literature on caregivers' experience caring for patients with pancreatic or periampullary cancer.

Patient-level clinical variables were abstracted from the institutions' National Surgical Quality Improvement Project databases. Variables abstracted include patient sex, age, race, body mass index, preoperative use of chemotherapy and radiation, indication for operation, and type of operation.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Intercooled Stata software, version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were presented in frequencies with percentages and compared across groups with the Chi-squared test. The frequency and difficulty associated with specific assistance were analyzed as ordinal variables and were compared across each other with Kendall's rank-order correlation coefficient. The specific assistance associated with the lowest frequency and least difficulty was used as the controls against the other assistance for the comparative analyses. Continuous variables were presented in medians with interquartile ranges and compared across groups with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical significance was accepted at the P < .05 level. Open-ended questions were analyzed qualitatively using a grounded theory approach and categorized themes were identified from the responses.

RESULTS

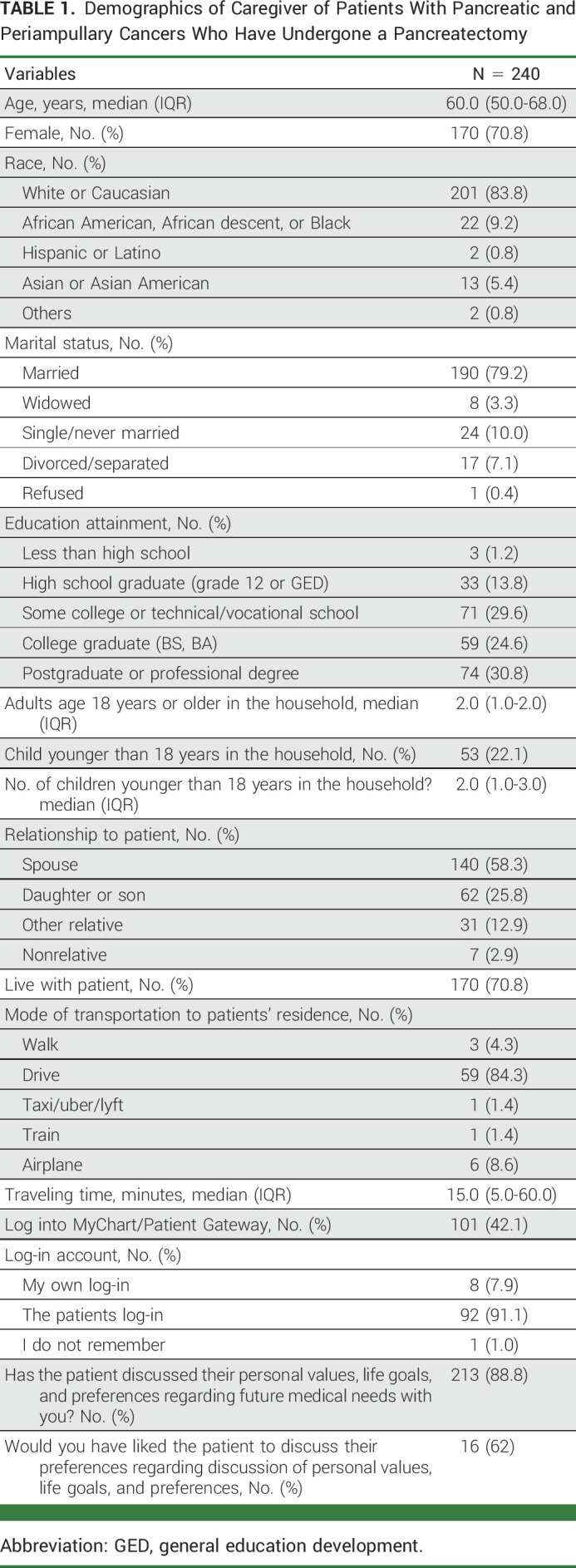

Caregiver Demographics

A total of 240 caregivers participated in the study (response rate 90.6%). The median age of caregivers was 60.0 years (IQR, 50.0-68.0 years), 70.8% of whom were women (Table 1). The majority were White (83.8%) and married (79.2%). More than half of the caregivers had at least a college graduate level education. When assessing the relationship of caregivers to patients, 58.3% reported being a spouse, 25.8% a daughter or son, 12.9% another relative, and 2.9% a nonrelative. Most caregivers (70.8%) lived with the patient, and for those who did not, most drove (84.3%) to the patients' residence with a median one-way traveling time of 15.0 minutes (IQR, 5.0-60.0 minutes). Less than half of caregivers logged into the MyChart/Patient Gateway, and for those who did, 91.1% used the patients' log-in instead of their own.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of Caregiver of Patients With Pancreatic and Periampullary Cancers Who Have Undergone a Pancreatectomy

Patient Demographics

There were 201 patients who participated in the study. Of all patients, 42.9% were female, with a median age of 68.2 years (IQR, 60.8-74.7 years). The majority of patients were White (87.1%), with another 6.9% and 3.7% being Black or African American and Asian, respectively. The median body mass index for the cohort was 25.1 kg/m2 (IQR, 22.5-28.1 kg/m2). Eighty one percent of patients underwent pancreatoduodenectomy, with the rest undergoing distal pancreatectomies. When assessing the indication of the operation, 69.2% of patients underwent pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, followed by 5.0% for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and 4.2% for ampullary adenocarcinoma. Of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, 36.6% had received preoperative chemotherapy and 28.2% had received preoperative radiation therapy.

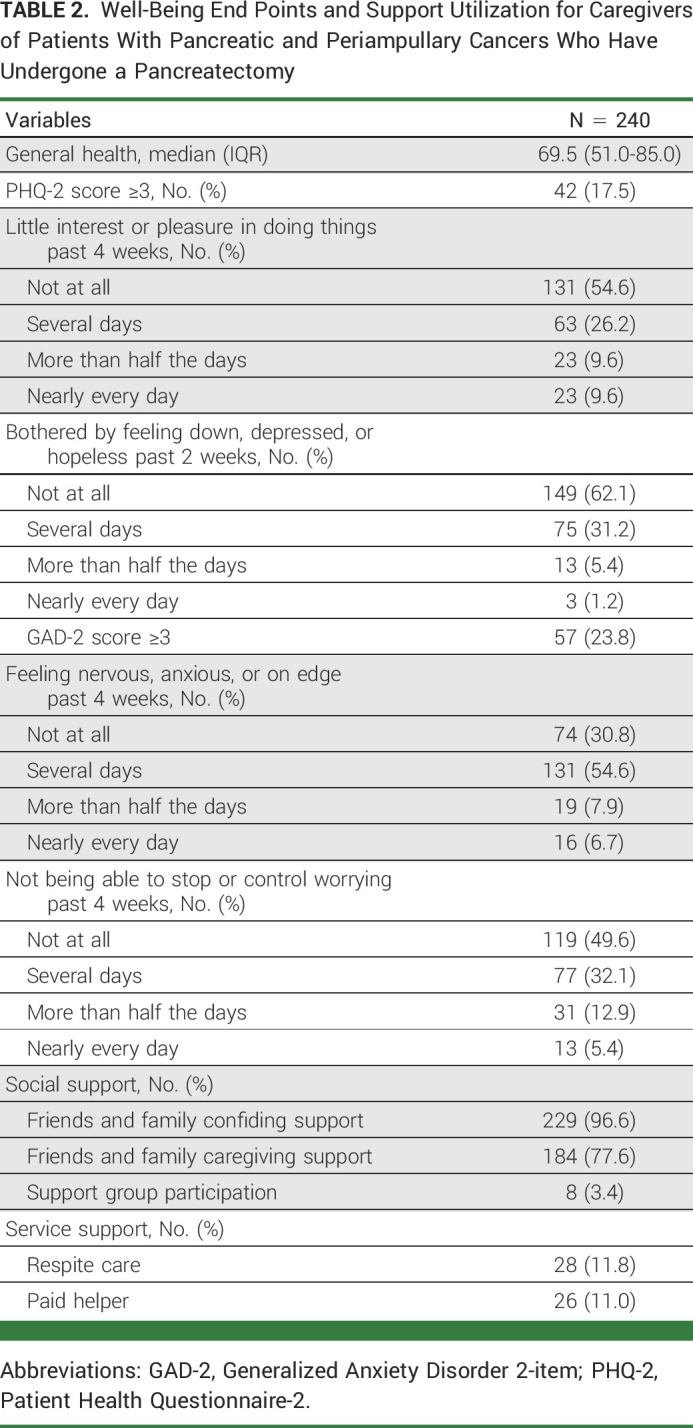

Caregiver Well-Being and Support

Caregivers reported a median general health score of 69.5 (IQR, 51.0-85.0) on a 0-100 scale. The prevalence of a positive depression screen with the PHQ-3 was 17.5%, and the prevalence of a positive anxiety screen with the GAD-3 was 23.8%. The breakdown of response to each instrument is shown in Table 2. Most caregivers reported having confiding support (96.6%) and caregiving support (77.6%). However, only 11.8% of caregivers used respite care, and 11.0% used a paid helper.

TABLE 2.

Well-Being End Points and Support Utilization for Caregivers of Patients With Pancreatic and Periampullary Cancers Who Have Undergone a Pancreatectomy

Nature and Difficulty of Assistance Provided

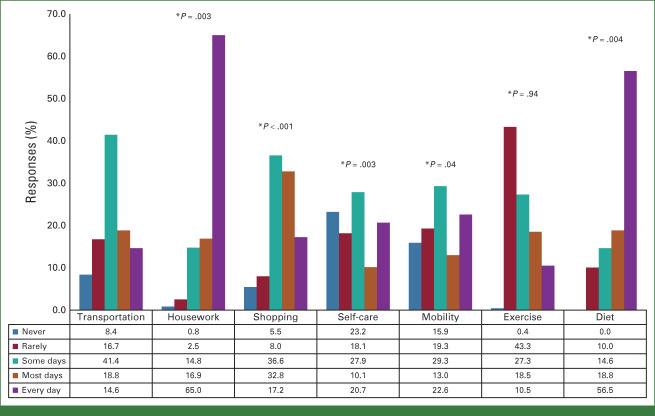

The least frequently provided type of assistance was transportation (18.8% most days, 14.6% every day). Caregivers most frequently provided the following assistance: shopping (32.8% most days, 17.2% every day, P < .001 when compared with transportation), housework (16.9% most days, 65.0% every day, P = .003 when compared with transportation), self-care (10.1% most days, 20.7% every day, P = .003 when compared with transportation), and diet-related assistance (18.8% most days, 56.5% every day, P = .004 when compared with transportation; Fig 1).

FIG 1.

The nature of assistance provided by caregivers to patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers after pancreatectomy. *P values compare the specific assistance with transportation as the control group.

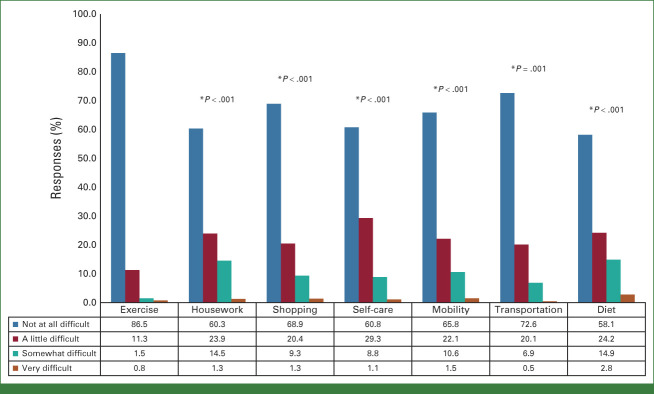

When assessing the difficulty associated with each type of assistance, caregivers reported the least amount of difficulty helping patients with exercise (1.5% somewhat difficult, 0.8% very difficult). Caregivers found all other assistance significantly more difficult to perform when compared with exercise (Fig 2.) Notably, caregivers found significantly more difficulty associated with assisting with housework (14.5% somewhat difficult, 1.3% very difficult, P < .001 when compared with exercise) and diet (14.9% somewhat difficult, 2.8% very difficult, P < .001 when compared with exercise).

FIG 2.

The degree of difficulty of assistance provided by caregivers to patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers after pancreatectomy. *P values compare the specific assistance with exercise as the control group.

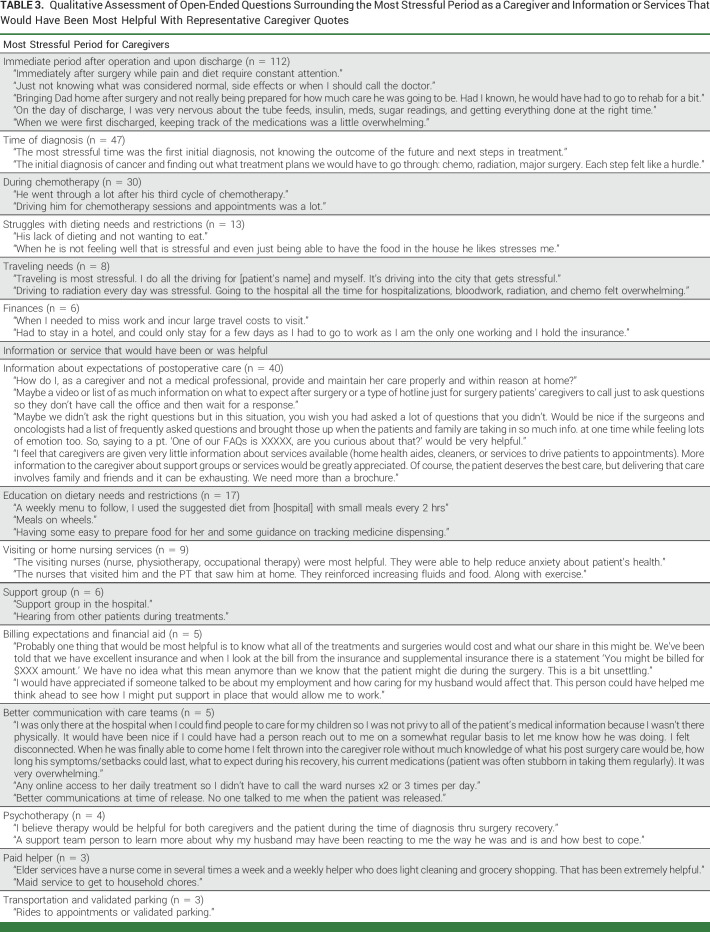

Most Stressful Time Periods and Caregivers' Needs

Caregivers identified the period immediately after the operation while the patient was still in the hospital and the period on discharge as the most stressful phases (n = 112, 46.7%). Caregivers noted in free-text comments that stress was associated with the intensity of care required, especially at home, surrounding symptom management and medication management (ie, timing of insulin dosing, frequency of pancreatic enzyme replacement). The second most endorsed aspect of stress involved psychosocial stress around the time of initial diagnosis (n = 47, 19.6%), followed by stress during treatment with chemotherapy (n = 30, 12.5%) and struggles with the patient's dieting needs and restrictions (n = 13, 5.4%). Other themes identified included stress because of travel and logistics (n = 8, 3.3%), finances (including pressure to remain at one's job to retain health insurance, for those who worked; n = 6, 2.5%), and challenges during treatment with radiation (n = 6, 2.5%; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Qualitative Assessment of Open-Ended Questions Surrounding the Most Stressful Period as a Caregiver and Information or Services That Would Have Been Most Helpful With Representative Caregiver Quotes

The majority of caregivers would have liked more information on expectations of postoperative care (n = 40, 16.7%). Additionally, they reported having received very little information about available services that could have supported their efforts, such as home health aides, paid helpers, or services that transport patients to appointments. The second most common deficient theme identified was the lack of knowledge on dietary needs and restrictions (n = 17, 7.1%). Caregivers struggled with knowing the types of food the patient could tolerate without causing abdominal bloating or diarrhea. Those who consulted with a nutritionist postoperative felt that such a consultation alleviated that stress. Other needs identified by caregivers included having visiting or home nursing services, participating in a support group who have gone through a similar experience, billing expectations and financial aid, better communication with care teams, and psychotherapy for both caregivers and patients (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study found that almost a quarter of caregivers for patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers after pancreatectomy screened positive for depression and anxiety. Although most caregivers had confiding and caregiving support, very few reported using respite care services or paid helpers. Caregivers most frequently provided patients assistance with shopping, housework, self-care, and diet. They reported the greatest difficulty providing assistance with housework and diet. Most caregivers identified the immediate postpancreatectomy and early discharge periods as the most stressful phases, emphasizing that more information on expectations of postoperative care and better preparation as a caregiver would have been most helpful.

The surgical and oncologic literature have historically focused on in-hospital outcomes such as length of hospital stay, morbidity, and readmission rates as quality metrics for cancer care. However, hospitals are moving to shorten length of hospital stay through enhanced recovery pathways to decrease the burgeoning health care cost.21,22 In this setting, a considerable amount of patient care responsibility has been shifted onto family and unpaid caregivers who presently serve as a considerable workforce even when patients are in rehabilitation and residential care facilities.23,24 A recent study demonstrated that social support was associated with decreased health care utilization and improved overall survival in patients with hematologic malignancies.25 Another study demonstrated that having social support was positively associated with the odds of receiving chemotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer.26 The ability of family and informal caregivers to provide care and assistance has a direct impact on patient outcomes, and providers should start conceptualizing health care as a process that encompasses care beyond the walls of the hospital. This study attempts to address this gap in pancreatic and periampullary cancer, an aggressive solid organ malignancy that requires a complex operation that likely renders patients even more reliant on caregivers for care.

Given the advanced age and frailty of most patients at the time of pancreatic or periampullary cancer diagnosis, support and assistance are often provided by adult children. These caregivers are typically working, in contrast to retired spouses who do not face similar working pressure. In this study, 42% of caregivers were either the children or relatives of patients. This is almost two-fold higher than the proportion (20%-30%) of adult children or relative caregivers reported in the breast27,28 and lung cancer caregiver population.29 Although most caregiver studies have focused on psychosocial interventions and support,30 the difference in caregiver demographics in this study has important implications for future research. There is a need to focus on assessing the impact of caregiving on financial stability and work productivity as these aspects are more relevant to a younger caregiver population looking after older patients with solid organ tumors.

Notably, up to a quarter of caregivers had positive scores on the depression and anxiety screens collected in the postoperative setting. A previous cross-sectional study of 462 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors demonstrated that patients experience weight loss, gastrointestinal disturbances, anxiety, and depression that all significantly impair their quality of life at the time of preoperative evaluation.9,31 The prevalence of patient depression and anxiety was associated with nonreceipt of chemotherapy treatment and poorer overall survival.32 It is likely that patients' caregivers also experience similar impairment to their well-being in the preoperative setting. Future studies should include caregiver assessment at the time of preoperative evaluation as another important time to provide initial support.

An important finding in this study is that caregivers reported that the most frequent type of assistance they provided—with the patient's diet—was also associated with a high degree of difficulty. This is consistent with the literature reporting that postpancreatectomy patients frequently experience postoperative digestive issues. An assessment of symptom clusters in 143 patients with pancreatic cancer found that gastrointestinal disturbances such as poor appetite, trouble digesting food, and weight loss to be the most prevalent and severe symptoms and persisted even at 9 months postoperatively.33 A separate study of 248 patients who had been treated via pancreatoduodenectomy demonstrated that bloating, indigestion, and excessive flatulence persisted even at 5 years after their resections.6 This is likely in part due to the changes in gastrointestinal anatomy associated with the pancreatoduodenectomy procedure that necessitates modifications in both the presentation (mechanical diet) and size of patients' meals. Along with the need for pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, caregivers likely experience difficulty in helping patients with day-to-day dietary challenges. Conversely, we found assistance with exercise to be least often identified as being difficult among caregivers. As exercise was not objectively defined in the questionnaire, caregivers may have interpreted the question as involving less strenuous or intensive activities—or the assisting with exercise have been overshadowed by more difficult tasks, reflecting anchoring biases.

When asked about potential support that could prove helpful for caregivers, the majority sought more information and education on postpancreatectomy expectations and patient care needs. This is consistent with the literature showing that caregivers lack access to and are poorly informed about patients' health and treatment plans.34-36 An assessment of 50 available websites on pancreatic cancer treatment options demonstrated a readability score equivalent to that of a second-year university level (<39% of US population),37 compounding the difficulty for caregivers to access relevant and understandable disease-specific information. The efficacy of providing this information during the preoperative clinic visit may be limited by cognitive overload, with most patients themselves being unsure of postoperative expectations.38 Video- and multimedia-based interventions have been shown to be beneficial to patients and caregivers in the preoperative setting for lung cancer,39 and the generalizability of such an intervention to caregivers of patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers should be investigated.

This study was conducted at 3 very high-volume, academic, tertiary referral centers for pancreatic and periampullary cancer. As such, participating caregivers may represent a more sophisticated and able population, and the study's findings may underestimate the demands of caregiving. Additionally, 84% of the studies' participant caregivers were White. More intentional participant recruitment to include caregivers of underrepresented racial minorities is needed so as not to exclude their perspectives and experiences. Finally, this study's timeframe focuses on 30 days after the initial operation, which is a limited time window to be assessing the caregiving experience. It is unknown if identified caregiving difficulties persist beyond the 30-day observation window or if there are other key challenges that extends beyond that timeframe and are unmeasured.

However, the majority of caregivers in this study identified the immediate postoperative phase as the most stressful time period, and the data presented are expected to represent the time during which caregiving needs are the most intense.

In conclusion, almost a quarter of caregivers for patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers after pancreatectomy were screened positive for depression and anxiety. Caregivers most frequently provided assistance with housework, self-care, and diet, and reported most difficulties with assisting with housework and diet. Most caregivers identified the immediate postoperative period and early discharge periods as the most stressful phases and desired more information on expectations of postoperative care and better preparation as a caregiver. This study provides a profile of family and unpaid caregivers for patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers and highlights the room for improvement in better preparing and supporting caregivers in providing care to their family members.

Cristina R. Ferrone

Research Funding: Intraop Medical (Inst)

Christopher L. Wolfgang

Leadership: Catalio

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Catalio

Albert W. Wu

Honoraria: Siemens Healthineers

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Siemens Healthineers

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

See accompanying editorial on page 523

DISCLAIMER

This is a US Government work. There are no restrictions on its use.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institute of Health under the award number: F32CA217455 and the Andrew L Warshaw, MD Institute for Pancreatic Cancer Research Grant under award number: 0004852948.

Z.V.F. and J.T. contributed equally to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Zhi Ven Fong, Motaz Qadan, Cristina R. Ferrone, David C. Chang, Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo, Jennifer L. Wolff, Albert W. Wu, Matthew J. Weiss

Administrative support: David C. Chang, Keith D. Lillemoe, Matthew J. Weiss

Provision of study materials or patients: Theresa P. Yeo, Dee Rinaldi, Fabian M. Johnston, Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo

Collection and assembly of data: Zhi Ven Fong, Jonathan Teinor, Theresa P. Yeo, Dee Rinaldi, Harish Lavu

Data analysis and interpretation: Zhi Ven Fong, Jonathan B. Greer, Motaz Qadan, Fabian M. Johnston, Charles J. Yeo, Christopher L. Wolfgang, Andrew L. Warshaw, Keith D. Lillemoe, Jennifer L. Wolff, Albert W. Wu

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Profile of the Postoperative Care Provided for Patients With Pancreatic and Periampullary Cancers by Family and Unpaid Caregivers

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Cristina R. Ferrone

Research Funding: Intraop Medical (Inst)

Christopher L. Wolfgang

Leadership: Catalio

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Catalio

Albert W. Wu

Honoraria: Siemens Healthineers

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Siemens Healthineers

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michelakos T, Sekigami Y, Kontos F, et al. Conditional survival in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients treated with total neoadjuvant therapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:2859–2870. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hue JJ, Ocuin LM, Kyasaram RK, et al. Weight tracking as a novel prognostic marker after pancreatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:3450–3459. doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-11325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fong ZV, Qadan M. Deciphering the etiology of weight loss following pancreatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:3369–3370. doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-11368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen CJ, Yakoub D, Macedo FI, et al. Long-term quality of life and gastrointestinal functional outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2018;268:657–664. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fong ZV, Sekigami Y, Qadan M, et al. Assessment of the long-term impact of pancreatoduodenectomy on health-related quality of life using the EORTC QLQ-PAN26 module. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:4216–4224. doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-09853-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fong ZV, Alvino DM, Castillo CF-D, et al. Health-related quality of life and functional outcomes in 5-year survivors after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2017;266:685–692. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim P-W, Dinh KH, Sullivan M, et al. Thirty-day outcomes underestimate endocrine and exocrine insufficiency after pancreatic resection. HPB. 2016;18:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeo TP, Fogg RW, Shimada A, et al. The imperative of assessing quality of life in patients presenting to a pancreaticobiliary surgery clinic. Ann Surg. 2023;277:e136–e143. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fong ZV, Lim P-W, Hendrix R, et al. Patient and caregiver considerations and priorities when selecting hospitals for complex cancer care. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:4183–4192. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09506-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolff JL. Family matters in health care delivery. JAMA. 2012;308:1529–1530. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, et al. A consensus-based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS) J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:3179–3187. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06737-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.https://www.nhats.org/researcher/nsoc National Study of Caregiving (NSOC)

- 15. Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Cornman JC, et al. Validation of new measures of disability and functioning in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A:1013–1021. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freedman VA, Agree EM, Cornman JC, et al. Reliability and validity of self-care and mobility accommodations measures in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Gerontologist. 2014;54:944–951. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.https://www.hiv.uw.edu/page/mental-health-screening/gad-2 Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item (GAD-2)

- 20. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, et al. Brief report: Screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lavu H, McCall NS, Winter JM, et al. Enhancing patient outcomes while containing costs after complex abdominal operation: A randomized controlled trial of the Whipple accelerated recovery pathway. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fong ZV, Ferrone CR, Thayer SP, et al. Understanding hospital readmissions after pancreaticoduodenectomy: Can we prevent them?: A 10-year contemporary experience with 1,173 patients at the Massachusetts General Hospital. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coe NB, Werner RM. Informal caregivers provide considerable front-line support in residential care facilities and nursing homes. Health Aff. 2022;41:105–111. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fong ZV, Teinor J, Yeo TP, et al. Assessment of caregivers’ burden when caring for patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:1468–1475. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson PC, Markovitz NH, Gray TF, et al. Association of social support with overall survival and healthcare utilization in patients with aggressive hematologic malignancies. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Davis RE, Trickey AW, Abrahamse P, et al. Association of cumulative social risk and social support with receipt of chemotherapy among patients with advanced colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13533. 10.6004/jnccn.2021.7033 [epub ahead of print on October 15, 2021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khanjari S, Langius-Eklöf A, Oskouie F, et al. Family caregivers of women with breast cancer in Iran report high psychological impact six months after diagnosis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner Jr H, et al. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale: Development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:55–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1026407010614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mosher CE, Jaynes HA, Hanna N, et al. Distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients: An examination of psychosocial and practical challenges. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1532-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burrell SA, Yeo TP, Smeltzer SC, et al. Symptom clusters in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing surgical resection: Part II. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2018;45:E53–E66. doi: 10.1188/18.ONF.E53-E66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davis NE, Hue JJ, Kyasaram RK, et al. Prodromal depression and anxiety are associated with worse treatment compliance and survival among patients with pancreatic cancer. Psychooncology. 2022;31:1390–1398. doi: 10.1002/pon.5945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burrell SA, Yeo TP, Smeltzer SC, et al. Symptom clusters in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing surgical resection: Part I. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2018;45:E36–E52. doi: 10.1188/18.ONF.E36-E52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zulman DM, Piette JD, Jenchura EC, et al. Facilitating out-of-home caregiving through health information technology: Survey of informal caregivers’ current practices, interests, and perceived barriers. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e123. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Swan BA. A nurse learns firsthand that you may fend for yourself after a hospital stay. Health Aff. 2012;31:2579–2582. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sarkar U, Bates DW. Care partners and online patient portals. JAMA. 2014;311:357–358. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Storino A, Castillo-Angeles M, Watkins AA, et al. Assessing the accuracy and readability of online health information for patients with pancreatic cancer. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:831–837. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O’Connor K, La Bruno D, Rudderow J, et al. Preparedness for surgery: Analyzing a quality improvement project in a population of patients undergoing hepato-pancreatico-biliary surgery. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020;24:E65–E70. doi: 10.1188/20.CJON.E65-E70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun V, Raz DJ, Ruel N, et al. A multimedia self-management intervention to prepare cancer patients and family caregivers for lung surgery and postoperative recovery. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18:e151–e159. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]