Abstract

This work presents the synthesis of 12 phenol and chromone derivatives, prepared by the analogs, and the possibility of conducting an in silico study of its derivatives as a therapeutic alternative to combat the SARS-CoV-2, pathogen responsible for COVID-19 pandemic, using its S-glycoprotein as a macromolecular target. After the initial screening for the ranking of the products, it was chosen which structure presented the best energy bond with the target. As a result, derivative 4 was submitted to a molecular growth study using artificial intelligence, where 8436 initial structures were obtained that passed through the interaction filters and similarity to the active glycoprotein pocket through the MolAICal computational package. Thus, 557 Hits with active configuration were generated, which is very promising compared to the BLA reference link for inhibiting the biological target. Molecular dynamics also simulated these compounds to verify their stability within the active protein site to seek new therapeutic propositions to fight against the pandemic. The Hit 48 and 250 are the most active compounds against SARS-CoV-2. In summary, the results show that the Hit 250 would be more active than the natural compound, which could be further developed for further testing against SARS-CoV-2. The study employs the de novo approach to design new drugs, combining artificial intelligence and molecular dynamics simulations to create efficient molecular structures. This research aims to contribute to the development of effective therapeutic strategies against the pandemic.

Keywords: Main protease, COVID-19, Molecular docking, Pandemic, Deep learning

Introduction

The worldwide outbreak of COVID-19 caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus has generated a significant health problem (Rosa et al. 2021). The WHO declared this outbreak a pandemic, and China has been the most affected country. It is one of the most challenging problems of the twenty-first century and has changed the lives of people all over the world. SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus that is responsible for the outbreak of COVID-19, a disease that resembles SARS or MERS coronaviruses (Zhang et al. 2021a, b). It is classified as a new type of epidemic pneumonia with a high mortality rate (Ge et al. 2021). The disease is transmitted from person to person, and its symptoms are fever, coughing, and pneumonia (Thanh Tung et al. 2020).

In response, researchers and doctors rushed to find a suitable treatment for COVID-19, repurposing drugs like hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, and remdesivir, to name a few. Many of those drugs showed no benefit and in some cases even harmful effects (Ferreira et al. 2021; Shirazi et al. 2022). Some promising drugs are natural molecules and their derivatives, which are generally cheaper and more available than synthetic drugs (Singh et al. 2022), like limonoids (de Oliveira et al. 2021), tangeretin (Da Rocha et al. 2021), resveratrol, emodin, naringenin (Chakravarti et al. 2021) that may interact with the ACE2, S protein or Mpro, the main targets for COVID-19 treatment.

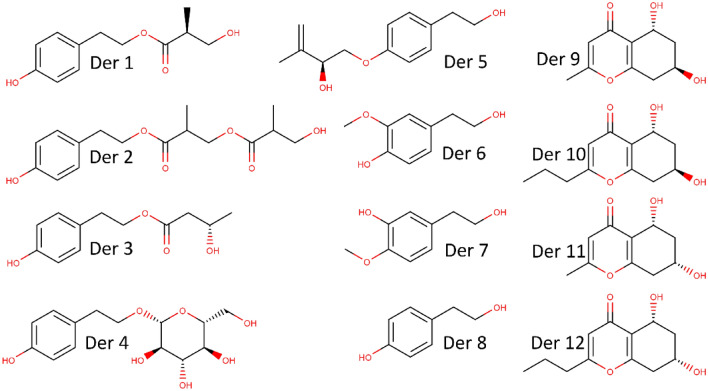

In this sense, Zhang et al. (2021a, b) found phenols and chromones derivated from Daldinia sp. had antiviral and antibacterial properties. In his work, the molecules (Fig. 2) and their derivatives assays showed anti-ZIKV (zika virus) and anti-influenza activities (Zhang et al. 2021a, b).

Fig. 2.

Initial growth structures of phenol and chromone derivatives

As the need for rapid screening of drugs and testing, amid a pandemic, computational tools can be an alternative to traditional drug development, as it is effective and cheaper. Among the diverse approaches, deep learning is a prevalent form of artificial intelligence that has been successfully applied in medical diagnostics, cell image analysis, organic synthesis, drug classification, and others (Kermany et al. 2018; Miao et al. 2019; Moen et al. 2019; Segler et al. 2018).

There are some options when looking for a drug planning tool using the deep learning model and classical algorithm that can perform the growth of fragments in the initial seed in the active pocket of receptors via the genetic algorithm. However, the MolAICal computational package is a representative, free, easy-to-install software for planning new drugs that can grow ligands fragment by fragment in the receiving bag. Another highlight is the Vinardo score, which MolAICal uses to evaluate the protein bag's binding affinity of growth ligands. In addition, MolAICal can also filter growth ligands according to synthetic accessibility (SA), Lipinski’s rule of five, and Pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) when new drug design tasks are being performed.

Based on the characteristics and merits of deep learning and classical programming, the MolAICal package is programmed to design 3D drugs in the specific cavity of the protein (Bai et al. 2021). The MolAICal package contains two modules written in the JAVA language.

Within this perspective, the present work proposes the search for new molecules based on phenol and chromones extracted from Daldinia sp., that exhibited some in vitro inhibitory antiviral properties, as efficient inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 through de novo design, aided by MolAICal artificial intelligence and additional study of molecular dynamics to generate new compounds that scores the highest binding affinity to the Spike glycoprotein and synthetic accessibility, with further investigation about the drug behavior with an absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) to provide their feasability of these new molecules as therapeutic agents.

Methodology

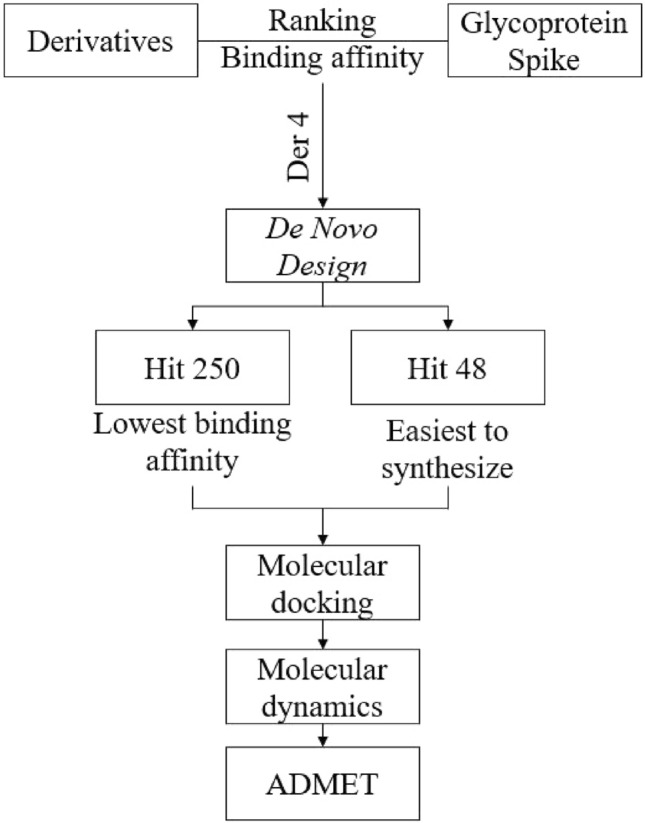

In silico study

An overall view of this work is simplified and represented in Fig. 1. First, an evaluation of the binding affinity of the derivatives and BLA (Biliverdin IX Alpha) with the Spike glycoprotein, through molecular docking, is realized to rank and select the lowest binding affinity from the compounds. In the second step, the selected molecule was used in the de novo design, in MolAICal, obtaining some potential drugs, from which the lowest binding affinity and highest synthetic accessibility are chosen as the best potential drugs and starting points to the further steps. In the sequence, study and evaluation of molecular docking (binding affinity, interaction with protein residues and MM/GBSA), molecular dynamics (RMSD, RMSF, H-bond, SASA), and ADMET (druglikeness, MCE-18, pharmacokinetic prediction, metabolism and oral toxicity) is performed to assess the potential to an in vitro and clinical trials of these molecules, using the BLA as a reference molecule.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the de novo design in this work

Preparation of binders and proteins

The derivatives (1–12), from the work of Zhang et al. (2021a, b) (Fig. 2), BLA, and the Hits 48 and 250 were created in Chem3D software (Ahmadi et al. 2005). The structures obtained in 3D were submitted subsequently to auto-optimization settings which was applied to the force field MMFF94S (Wahl et al. 2019), to generate bioactive conformations by minimization of randomly generated conformers, with algorithm Steepest Descent algorithm (Petrova and Solov’Ev 1997), and Step per Update 4 (Sutton et al. 2016) by software AVOGADRO® (Hanwell et al. 2012). All files with ligands were converted to corresponding formats (.mol2 and .pdbqt) with the addition of ionization and tautomeric states at pH 7.4 by using OpenBabel ver. 3.0.0 software (O’Boyle et al. 2011).

Protein structural preparation

The receptor under study was the Spike glycoprotein (glycoprotein S or E2) of SARS-CoV-2, obtained from the protein database repository code (PDB) ID 7B62 (Rosa et al. 2021), whose crystalline structure was obtained by X-ray diffraction. To validate the simulations, the redocking technique was performed on the co-crystallized ligand, biliverdin ix alpha (BLA), which was in the original file of the co-crystallized protein. In addition, the interfering residues, water molecules, and synthetic inhibitors were removed. Polar hydrogens were added to binders and protein separately. The used software was AutoDock Tools (Morris et al. 2009).

Deep learning model and de novo drug design

MolAICal contains the deep learning generator model of the drug, which was trained from 21,064 FDA-approved drug fragments. The 90 fragments generated by MolAICal and another 30 primary fragments were mixed for fragment growth in the cavity of the Spike glycoprotein.

Grid coordinates

The x, y, and z coordinates of the center of the cavity box of the glycoprotein were set to 21.404, 14.571, and − 18.006 Å, respectively. The cavity box lengths of the protein will be set to 30.0 Å along the x, y, and z directions. The fittest molecules were extracted for the subsequent evolved growth of 10% of the generated molecular populations. The 140 best molecules of generated molecular populations will be developed as the mother molecules. Thus, over 60 molecules were randomly selected from the generated molecular populations to increase the diversity and novelty of growth ligands. The maximum population was set at 3000.

Fibonacci points, Lipinski filter, and interference

Fibonacci’s 361 points are generated for the search for fragment disturbance, using the golden angle to distribute the points of the subsequent fragments from the initial growth fragment in the Spike glycoprotein pocket. Then when the fragments grow and form a ligand, a genetic algorithm is applied to optimize molecular conformation of the ligand. Crossover and mutation operators were set to 1.0 and 0.5, respectively.

According to Lipinski’s rule of five, a set of rules of the physico-chemical descriptors that encompasses most drugs used for druglikeness and ADMET, values of crystal binders in the glycoprotein, was to be defined for the values of XLOGP (5.0), hydrogen acceptors (10), hydrogen donors (5), molecular weight (500), and rotary bonds (10).

Pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) are compounds that may not have a therapeutic effect in vivo despite showing in silico fitting scores (Baell and Walters 2014), these compounds that usually are false positives, in the case of genetic algorithm may induce a false convergence of the optimal solution, were filtered out of unwanted growth binders.

After the genetic algorithm produced a generation, MolAICal uses a Vinardo score, to select the fittest ligands for the next generation. For this, it considers steric interactions, hydrophobicity, and H-bonds to evaluate the affinity between ligand and protein pocket.

Accessibility of synthesis

MolAICal has the Ambit-SA library, which allows to evaluate how easy a compound can be synthesize. This library utilizes 4 scores: molecular, stereochemical, fused and bridged systems complexity, which ranges from 0 to 100 (hardest to easiest). The synthetic accessibility score of the growth ligands was saved in the statistical results file at the end of the simulation. A total of 30 cycle generations was carried out for the entire drug design process. A total of six parallel drug design processes were carried out at protein. The Spike glycoprotein of the generated binders was saved between 480 and 785 from the molecular weight.

Processing

A total of 30 CPU multicores were executed in parallel for the entire molecular growth process. Drug as the whole design process combined with deep learning model and classical programming was carried out automatically by MolAICal’s designed package.

Molecular generation against the target protein was performed using the MolAiCal computational package (Bai et al. 2021) on a 10th Generation Intel®™ Core Intel CPU, up to 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA® GeForce® GTX 1660 Ti GPU, with a scanning time set to 8 h. Ten clusters were used to generate the structures. An average of approximately 8436 molecules were developed for the target protein during the experimental period.

Molecular docking and dynamics general filter

For this study, it is curious to point out that the estimated Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of binding is dependent on the semi-empirical free energy force field AMBER (Eberhardt et al. 2021) which composes the Autodock Vina algorithm. While stability analysis of ligand-receptor complex formation is possible through stability analysis using MM/GBSA calculations.

Molecular docking

The code used was AutoDock Vina, with its Lamarckian genetic algorithm (AG) in combination with grid-based affinity energy (Trott and Olson 2010), with the anchor region according to the synthetic binding found co-crystallized in the protein (BLA). The Spike glycoprotein was obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 7B62) (Rosa et al. 2021). Its structure was archived in the Protein Database with a resolution of 2.16 Å, determined from X-ray diffraction, classified as viral protein. The Lipinski’s rule of five (Benet et al. 2016), RMSD of up to 2.0 Å (Hevener et al. 2009), and affinity energy less than − 7.0 kcal/mol were used as an exclusion factor. The most favorable ones were represented by the lowest free binding energy (ΔG) (Gurung et al. 2016). Discovery Studio (Biovia 2015) conducted interaction 3D/2D visualization analysis studies, and Poseview was added (Fricker et al. 2004; Stierand et al. 2006).

Molecular dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed with the program NAMD (Phillips et al. 2005). The best conformations obtained in molecular docking were in the water solvated case in the TIP3P model (Kato et al. 2021), and in the CHARMM36-mar2019 force field (Huang et al. 2016). The preparation of the system was carried out in two steps. In the first step, the ligands were parameterized on the Charmm-Gui server (Jo et al. 2013) (https://www.charmm-gui.org/), and then they were submitted to the CGenFF server for parameter identification for CHARMM36 (Vanommeslaeghe et al. 2010). In the second step, the protein was prepared in the NAMD program. 1 Na+ ion per ligand was added to neutralize the total charge of the system. The latter was subjected to energy minimization by the Steepest Descent method. Then the system was subjected to NVT and NPT equilibrations under conditions described by Langevin (Farago 2019). The production simulations to study the system were performed for 100 ns. N3 was used as a standard reference drug to analyze the interactions between the ligand and the protein.

The quality of the structures obtained in MDs was evaluated using the following parameters with NAMD: potential energy (kcal/mol) (Diez et al. 2014); protein–ligand interaction energy (kcal/mol); root mean square deviation (RMSD, Å) of protein, ligands, and distances between them; root mean square fluctuation (RMSF, Å), minimum distances between proteins and ligands observed in MD (Arshia et al. 2021). Hydrogen bonds were evaluated with visual molecular dynamics (VMD) (Humphrey et al. 1996). The graphs will be generated using the Qtrace program (Lima et al. 2012; Phillips et al. 2005).

MM/GBSA calculations

MM/GBSA was calculated by MolAICal (Bai et al. 2021) on the basis of the MD log file of NAMD software (Phillips et al. 2005). The MM/GBSA is estimated by Eqs. 1, 2, and 3.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where ΔEMM, ΔGsol, and TΔS represent the gas phase MM energy, solvation-free energy (sum of polar contribution ΔGGB and non-polar contribution ΔGSA), and conformational entropy, respectively. ΔEMM contains van der Waals energy ΔEvdw, electrostatic ΔEele, and ΔEinternal of bond, angle, and dihedral energies.

Molecular dynamics simulations are an effective tool for understanding the relationships between the structure and function of macromolecules. Thus, this means that the information obtained from the dynamic properties of macromolecules is detailed enough to challenge the conventional paradigm of structural bioinformatics, which focuses on studying unique structures, and instead allows the analysis of conformational sets. The entropic contribution can be assessed based on MD trajectories by performing MD simulations. However, this contribution is usually ignored and, when considered, is mostly configurational rather than thermal. Configurational entropy can be estimated using trajectories based on the variance–covariance matrix of atomic positional fluctuations. A quasi-harmonic method can be used, in which the variance–covariance matrix is calculated for all atoms of the complex. In the quasi-harmonic process, the mass-weighted variance–covariance matrix is calculated from the DM trajectories using Cartesian coordinates. The global translations and rotations of the solute molecule are removed using the slightest squares adjustments of mass-weighted coordinates.

The GB method (with a, b, and c set to 0.8, 0, and 2.91, respectively, and with the default modified Bondi radii) was used to calculate the polar solvation energy, and the non-polar solvation energy was calculated using the solvent accessible surface area, according to Eq. 4.

| 4 |

The non-polar component of desolvation was estimated using the LCPO algorithm, with γ being 11.948 kcal/mol/Å2 and b 12.862 kcal/mol. Entropy was calculated by a standard mode analysis of the calculated harmonic frequencies at the MM level. In addition to water, to increase the accuracy, residues more than 8 Å of the binders were fixed to maintain the original geometry of the binders (Genheden and Ryde 2010).

In the MM/GBSA calculations, the polar component of desolvation was calculated by the modified GB model (GBOBC1, igb = 2 in Amber18) developed by Onufriev et al. (Onufriev et al. 2000), the exterior (solvent) dielectric constant was set to 80 as default.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as standard error ± of each experiment. After confirming the normality of distribution and data variance homogeneity, the groups’ differences were submitted to variance analysis (unidirectional ANOVA), followed by the Tukey test (Olleveant et al. 1999). All analyses were performed using Origin 8.5, with a statistical significance of 5% (p < 0.05).

In silico ADMET study

This predictive study of druglikeness properties and pharmacokinetic descriptors of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) was adapted from the methodologies of Rocha et al. (2022) and Lima et al. (2021), where different services available online constitute a consensus prediction between empirical decisions and numerical descriptors of in vivo and in vitro tests deposited in databases. Initially, the two-dimensional structural representation of the compounds was converted into a simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) and submitted to the ADMETlab 2.0 server (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) for quantitative estimation of druglikeness (QED) (Eq. 5) and for the similarity test with compounds registered in patents of the Medicinal Chemistry Evolution algorithm, 2018 (MCE-18) (Eq. 6)

| 5 |

| 6 |

where QED is defined by the sum of the physical–chemical properties (n = 8) that are within the ideality limit (di), which include: molecular weight (MW), partition coefficient (logP), H-bond donors (HBD), and H-bond acceptors (HBA), topological polar surface area (TPSA), number of rotatable bonds (nRot), number of aromatic rings (nAR), and reactive molecular fragments (Bickerton et al. 2012). MCE-18 relates the distribution of sp3 hybridization atoms between cyclic and acyclic structures, which include aromatic (AR) and non-aromatic (NAR) rings, chiral centers, and spiro-cyclic groups, where the final score expresses the degree of similarity of the compounds with substances registered in patents in recent years, where MCE-18 values > 45 show a better fit in this spectrum (Ivanenkov et al. 2019). The results were compared to the druglikeness from the Pfizer rule (optimal: logP ≤ 3, and TPSA > 75 Å2) (Hughes et al. 2008), GSK filter (optimal: logP ≤ 4 and MW ≤ 400 g/mol) (Gleeson 2008), and Golden Triangle rule (optimal: − 2 < logD ≤ 5 and 200 < MW ≤ 500 g/mol) (Johnson et al. 2009).

And then the SMILES code of the ligands was reported to PreADMET (https://preadmet.qsarhub.com/) and ADMETlab 2.0 (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) servers for estimation of passive permeability by the Madin-Darby Canine Kidney cells model (Papp MDCK), P-glycoprotein substrate (Pgp), human intestinal absorption (HIA), volume of distribution (VD), plasma protein binding (PPB), and blood–brain barrier permeability (BBB) as indicative of activity in the central nervous system (CNS). Finally, metabolism sites and reactive structural fragments were detected from the consensual structural reading between XenoSite (https://xenosite.org/) and Stoptox (https://stoptox.mml.unc.edu/) servers and related to excretion descriptors, including intrinsic clearance rate (CLint,u) and half-life (T1/2), organ toxicity descriptors, which include human hepatotoxicity (H-HT) and Ames mutagenicity (Xu et al. 2012), as well as acute toxicity, such as median lethal dose (LD50) in rats and median lethal concentration (LC50) in Minnow, performed on ProTox-II (https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/) and pkCSM (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/).

Results and discussion

In silico study

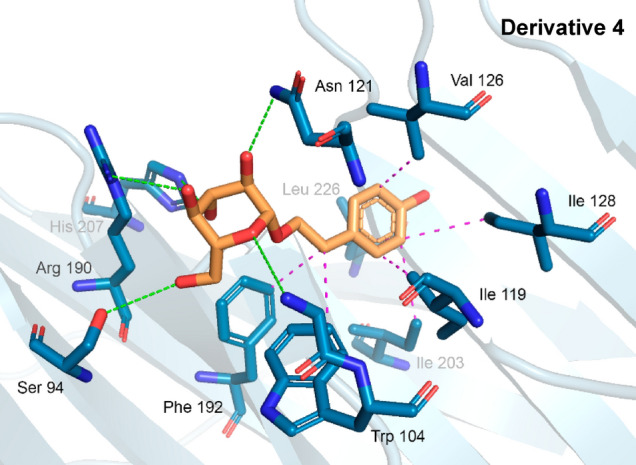

Based on the virtual screening performed by AutoDock Vina, it was possible to verify the affinity energies (kcal/mol) and correlated root mean square deviation (RMSD) between binder receptor against the Spike glycoprotein, especially derivative 4, with affinity energy of − 6.8 kcal/mol (RMSD 1.088 Å), evidencing moderate competitiveness, compared to the reference linker BLA with − 8.1 kcal/mol (Tumskiy and Tumskaia 2021; Wu et al. 2022) (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Data of energy of the compounds in front of molecular docking

| ID | Compounds | Binding affinity |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock vina (kcal/mol) | ||

| 1 | Der 1 | − 6.3 |

| 2 | Der 2 | − 6.4 |

| 3 | Der 3 | − 6.2 |

| 4 | Der 4 | − 6.8 |

| 5 | Der 5 | − 6.2 |

| 6 | Der 6 | − 5.2 |

| 7 | Der 7 | − 5.2 |

| 8 | Der 8 | − 5.1 |

| 9 | Der 9 | − 6.3 |

| 10 | Der 10 | − 6.2 |

| 11 | Der 11 | − 6.1 |

| 12 | Der 12 | − 6.5 |

| 13 | BLA | − 8.1 |

Fig. 3.

3D interactions of derivative 4 and Spike glycoprotein residues

All simulations performed (docking and redocking) presented RMSD values lower than 2 Å, highlighting the best pose of the BLA-glycoprotein complex, which presented RMSD in the order of 2.0 Å. From the best pose choices based on the RMSD, the binding affinity of the complexes for the ligands was evaluated, where again, the complex can be highlighted, which presented energy in the order of − 8.1 kcal/mol.

Thus, to assess the stability of the complex (proteins/ligand), the binding energy was used as a parameter, which has ideality parameters values below − 6.0 kcal/mol (Shityakov and Förster 2014). Then compound 4 was used as a starter for drug design de novo to potentiate binding capacity and bring new bioactive structures.

Production of Hits

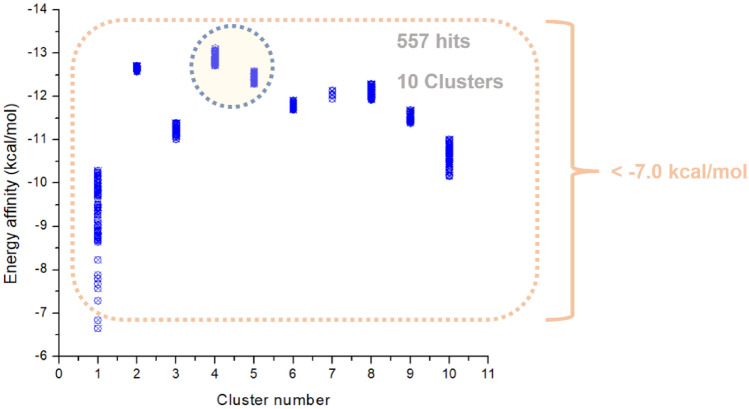

After the new drug design method, using MolAICal artificial intelligence software, we obtained 557 Hits (the active substance in the system), from the initial phenol derivative growth structure (derivative 4), in Fig. 3.

Up to ten clusters were processed, all of which obtained structures with affinity energy variation ranging from − 13.0 to − 7.0 kcal/mol, which obtained more favorable energies, as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Cluster number versus affinity energy

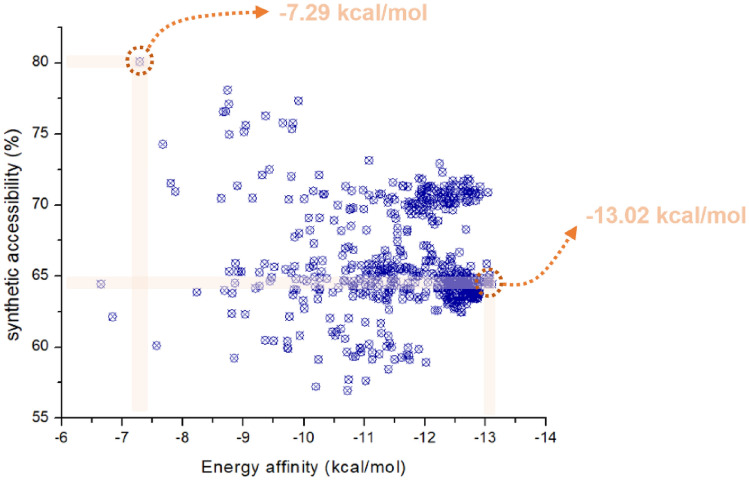

Synthetic accessibility

In the case of a molecule projected by de novo design, the experimental validation of its activity requires the synthesis of the compound. An approach to estimate the ease of synthesis of a ligand is called synthetic accessibility (SA), which is used to generate drug-like molecules and is necessary for many areas in the drug discovery process (Jain and Agrawal 2004; Wang et al. 2022). The evaluation of the SA of a lead candidate is a task that plays a role in the discovery of the lead, regardless of the method by which the lead candidate is identified (Scotti et al. 2013). The more complex the synthesis of the leading candidate, the more time and resources are needed to explore this specific area of the chemical space.

When chemical structures are built during the de novo drug design process, it cannot be taken for granted that such compounds' chemical synthesis is feasible. The synthetic accessibility pattern of the study’s Hits presented a very characteristic behavior of literature, where when the best fits protein, the more complex synthesis becomes (Ertl and Schuffenhauer 2009). However, it is possible to get Hits with ease of 75–80%, with an energy affinity of up to − 7.29 to − 13.02 kcal/mol, as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Synthetic accessibility versus affinity energy

Affinity energy

The 100 closest best results in affinity energy and RMSD were selected from the analogs produced, triggering the ligands to be grouped into clusters of similarity. The results of the generation experiments showed that the molecules obtained later had a better-fit score. The consequences for Spike glycoprotein demonstrate this trend well because the clusters generated were formed in proportion to time. Thus, this is possible because larger values generate more diverse molecules, but the convergence of mooring scores becomes poorer. According to the methodology, Cluster 1 initially presented two structures that did not interact very well with the protein, giving energies up to > − 7.0 kcal/mol. From Cluster 2 up to Cluster 10, there was an increase in affinity in the results, presenting energies below − 9.5 kcal/mol, where the most stable structure was Hit 250, with a binding energy of − 13.02 kcal/mol, representative of Cluster 4, taking into account, that the designs presented greater structural complexity, which decreased their SA. Cluster 1, in particular, presented a model that best adapted to synthetic accessibility 80%, in this case, the Hit 48, with an affinity energy of − 7.29 kcal/mol. These results are presented in Fig. 6.

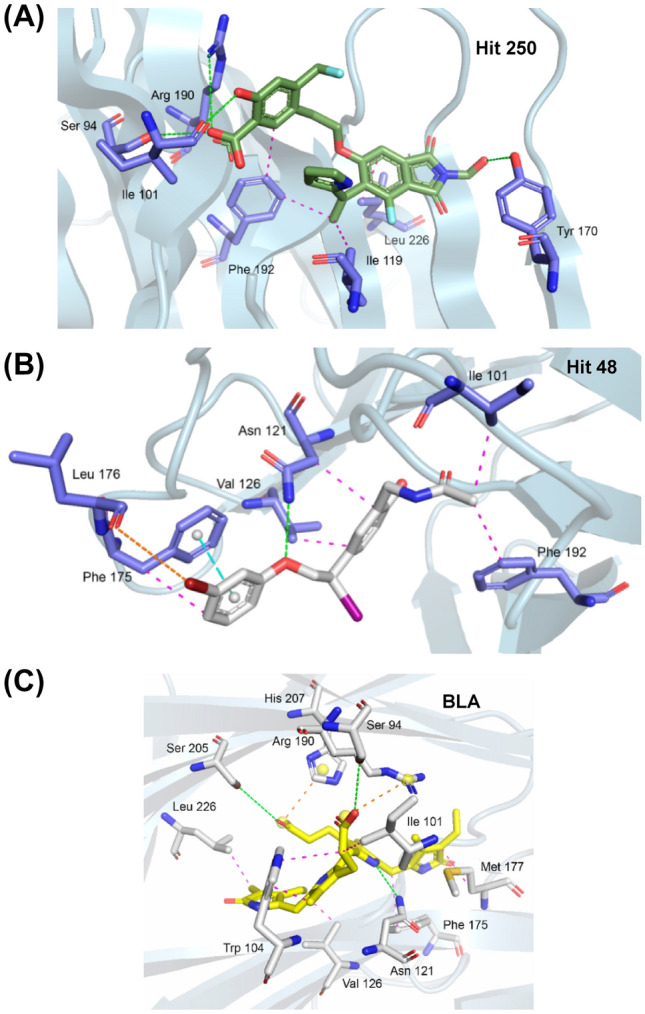

Fig. 6.

3D interactions between Hit 250 (a), Hit 48 (b), and BLA (c) and Spike glycoprotein residues

Interaction with protein residues

In a series of docking simulations performed by Singh et al. (2022) and Singh and Purohit (2023a, b), it is possible to observe the strong influence of compounds consisting of at least two rigid rings that have ether (R–O–R) and carbonyl (R–C=O) functional oxygenated groups, whether ester or ketone, on the selective modulation of Spike glycoprotein of SARS -CoV-2.

Hit 250 provided in molecular docking an RMSD of 1.3 Å, with an affinity energy of − 13.02 kcal/mol, interacting in the same region as the native BLA linker, as shown in Fig. 5a. With strong interactions, it presented four hydrogen bonds in the residues Ser 94 (2.74 Å), Ile 101 (2.10 Å), Tyr 170 (2.28 Å), and Arg 190 (3.04 Å), with a strong contribution from its oxygenated H-bond donor groups, accompanied by hydrophobic interactions pi-alkyl and alkyl with residues Ile 119 (3.77 Å), Phe 192 (3.94/3.78 Å), and Leu 226 (3.79 Å), with a strong contribution from its benzene and the heterocyclic rigid rings (Fig. 6a). The luminant represented by Hit 48, in Fig. 6b, presented the polar interaction represented by a strong hydrogen bond in the residue Asn 121 (2.51 Å), where the ether group (R–O–R) is the nucleophilic acceptor. In addition, a pi-Stacking interaction was observed with the residue Phe 175 (3.71 Å) and a halogen bond between the leu 176 residue (3.96 Å) and the bromine atom of the ligand. The coronaviral spike is the dominant viral antigen and the target of neutralizing antibodies. Finally, the linker used as a reference standard, the BLA, in the redocking study showed strongly three hydrogen bonds with the residues Ser 94 (2.54 Å), Asn 121 (2.29 Å), and Ser 205 (2.56 Å), with hydrophobic interactions in the residues Ile 101, Trp 104, Val 126, Phe 175, Met 177, and Leu 226, shown in Fig. 6c. Previous studies have shown that substitutions of Spike residues closely involved in ligand binding as His 207, Arg 190, and Asn 121, have Influenced in inhibition mechanism of the protein (Kim et al. 2021; Kumar et al. 2020; Rosa et al. 2021; Wagener et al. 2020). Additional data are presented in more detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative table of distances between residues/ligands

| Residues protein of S-glycoprotein | Molecular docking results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance of ligands (Å) | ||||

| BLA | Hit 250 | Hit 48 | Der 4 | |

| Ser 94 | 2.54 (HB) | 2.74 (HB) | – | 2.69 (HB) |

| Ile 101 | 3.84 (HI) | 2.10 (HB) | 3.54 (HI) | |

| Gly 103 | – | – | – | 2.92 (HB) |

| Trp 104 |

3.87 (HI) 2.85 (HI) |

– | – | 3.62 (HI) |

| Ile 119 | – | 3.77 (HI) | – | 3.58 (HI) |

| Asn 121 | 2.29 (HB) | – |

3.65 (HI) 2.51 (HB) |

2.16 (HB) |

| Val 126 | 3.27 (HI) | – | 3.41 (HI) | 3.78 (HI) |

| Ile 128 | – | – | – | 3.88 (HI) |

| Tyr 170 | – | 2.28 (HB) | – | – |

| Phe 175 | 3.79 (HI) | – | 3.71 (PS) | –– |

| Leu 176 | – | – | 3.96 (HaB) | – |

| Met 177 | 3.78 (HI) | – | – | – |

| Arg 190 | 5.05 (SB) | 3.04 (HB) | – | 2.79 (HB) |

| Phe 192 | – |

3.94 (HI) 3.78 (HI) |

3.77 (HI) | 3.73 (HI) |

| Ile 203 | – | – | – | 3.84 (HI) |

| Ser 205 | 2.56 (HB) | – | – | – |

| His 207 | 4.36 (SB) | – | – | 2.73 (HB) |

| Leu 226 | 3.30 (HI) | 3.79 (HI) | – | 3.63 (HI) |

HB (hydrophobic interactions: alkyl and π-alkyl), HB (hydrogen bond), SB (salt bridge), HaB (halogen bond), PS (π-stacking)

MM/GBSA calculations

After balancing the production dynamics, the sampling of the steps was performed from 5 to 5, following the sampling interval of 10 ns of the methodology for estimating the free energy variation using multiple trajectories. MM/GBSA calculations were performed in an implicit solvent field simulating a 0.15 M saline solution.

Although formally, the calculation of the free energy variation in this technique goes through the analysis of entropy from the normal modes of the system Eqs. 7, 8, and 9.

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

Calculations of normal modes are pretty time-consuming and computationally costly. This type ultimately makes virtual screening calculations, which are the focus of this study, not entirely impossible. However, there is a more important reason. It has been shown that entropy calculations decrease the correlation of predicted affinity values with experimental values when the analysis is done with a few microstates sampled from the trajectories (Hou et al. 2011; Rastelli et al. 2009). Because calculation time limitations are essential, including these calculations in the procedure is not encouraged.

MM/GBSA energies are considered a way to estimate free energy for in silico study of ligands in protein complexes (Genheden and Ryde 2015). They are typically based on MD simulations and bring accuracy between empirical punctuation and strict alchemical disturbance (Chen et al. 2018). As in conformational entropy, it is tough to obtain a concurrent value. Mainly, if ligands do not have any binding-induced structural changes in MD simulations, conformational entropy is generally ignored to calculate by standard mode analysis (Wang et al. 2018). MolAICal, therefore, provided a quick way to evaluate bonding free energy without ligand entropy based on the three-trajectory approach. Where, once again, the native ligand BLA/S-glycoprotein complex proved to be the best result, which continued to be the most stable in the study system, based on its free energy, with − 28.79 kcal/mol concerning the other ligand under study, Hit 48, which presented a free energy − 20.91 kcal/mol, and Hit 250, with free energy estimative − 15.50 kcal/mol. Therefore, the interaction energy decomposition technique revealed the contribution of the ligand–receptor complex and its final energy in Table 3.

Table 3.

Free energy estimation data of Hit 48, Hit 250, and BLA S-glycoprotein

| Complex | ∆E (electrostatic) + ∆G (sol) | ∆E (VDW) | ∆G binding (Kcal/mol) | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLA/S-Glycoprotein | 24.01 | − 52.80 | − 28.79 | ± 0.0262 |

| Hit 48/S-Glycoprotein | 15.51 | − 36.42 | − 20.91 | ± 0.0180 |

| Hit 250/S-Glycoprotein | 31.20 | − 45.69 | − 14.50 | ± 0.0260 |

Molecular dynamics

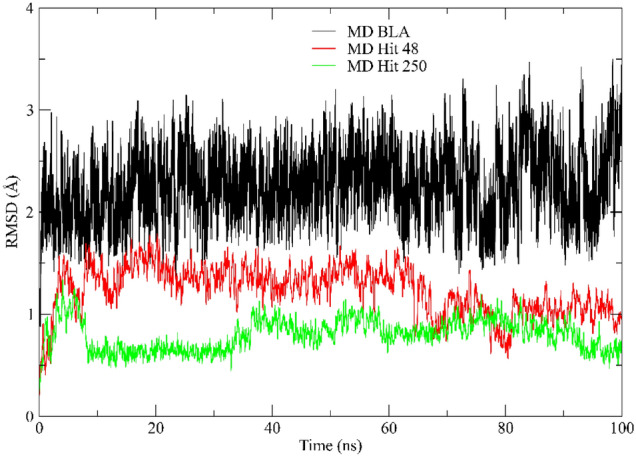

RMSD analysis

After the analysis of the energy values, other important parameters to investigate the quality of the molecular dynamics are root mean square deviation (RMSD) of protein (backbone) to Hit 250, Hit 48, and BLA. The RMSD values obtained by the protein backbone along the MDs show all values between 0.76 Å and 2.10 Å. In the MD with the Hit 250 ligand, the profile is closer to 0.8 Å. Soon after the MD of Hit 48 demonstrated similar behavior to the previous one, but only reached a more stable configuration when it arrived at 82 ns, with an average RMSD of 1.0 Å. Already finalizing, the RMSD values of MD with the reference linker BLA showed a situation of suitability to the most favorable system during the trajectory of 100 ns, with an average value of 1.9 Å, as shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

RMSD profile value obtained for S-glycoprotein with BLA (black line), Hit 250 (green line), and Hit 48 (red line)

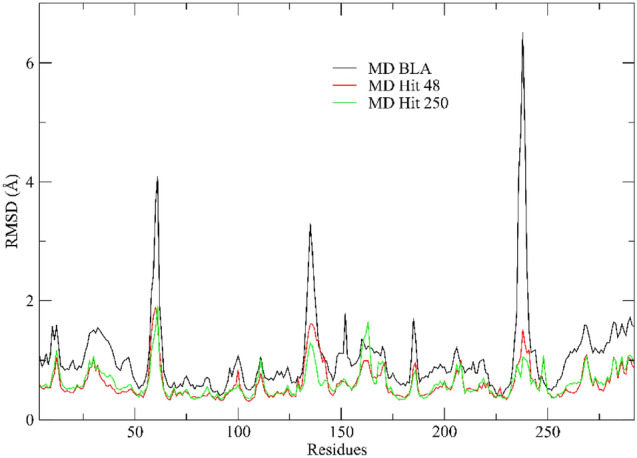

RMSF analysis

The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) is a parameter related to the flexibility of individual protein residues, serving to qualitatively assess the progression of molecular dynamics (Dong et al. 2018). Considering Fig. 8, a similar profile of RMSF values is observed regardless of the ligand in contact. However, it should be noted that the native leach er has obtained greater fluctuations in the residues Gln 52, Phe 135, and Gly 232, with values above 2.0 Å.

Fig. 8.

RMSF profile value obtained for S-glycoprotein with BLA (black line), MD Hit 250 (green line), and Hit 48 (red line)

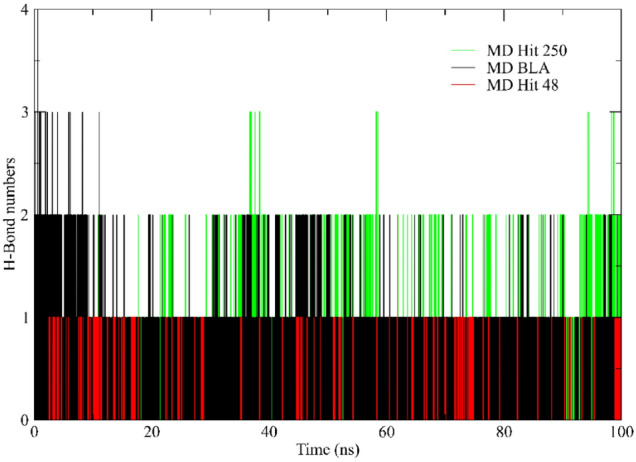

H-bonds

The number of hydrogen bonds (H-Bond) found during MDs, considering the maximum value of 3.3 Å, is shown in Fig. 9 and Table 4. About MD with reference ligand, BLA presents up to four hydrogen bonds per frame and several frames with three hydrogen bonds. The Hit 250 has only ten frames with three hydrogen bonds and several frames with two hydrogen bonds during molecular dynamics. And finally, MD with Hit 48 presents a smaller number of frames with two hydrogen bonds and several frames with one hydrogen bond. Therefore, it can be inferred that so much of the BLA as Hit 250 tend to interact more with Spike glycoprotein, making it a possible efficient antiviral against this virus. The interaction tendency between glycoprotein and Hit 250 can be confirmed by maintaining the binding site along the MD, evidenced by the hydrogen bonds detected in the three systems.

Fig. 9.

Number of hydrogen bonds (H-Bond) found between S-glycoprotein with BLA (black line), Hit 48 (red line), and Hit 250 (green line)

Table 4.

Residues of the S-glycoprotein that showed H-bond along the MDs

| System | H-Bond |

|---|---|

| MD with BLA | Ser 94, Glu 96, Asn 99, Ile 101, Asn 121, Tyr 170, Ser 172, Gln 173, Asp 178, Arg 190, and His 207 |

| MD with Hit 250 | Ser 94, Glu 96, Ile 101, Asn 121, Gln 173, and Arg 190 |

| MD with Hit 48 | Gly 103, Ser 205, His 207, and Leu 226 |

In the residues identified with H-bonds along the molecular dynamics, in Table 2, the recurrence of residues Asn 121, Arg 190, and His 207 is observed, as discussed previously in the docking results, a ligand binding in those residues are associated with inhibition of the protein, thus demonstrating an interaction potential of both Hit 48 and Hit 250, like the interaction between S-glycoprotein and BLA.

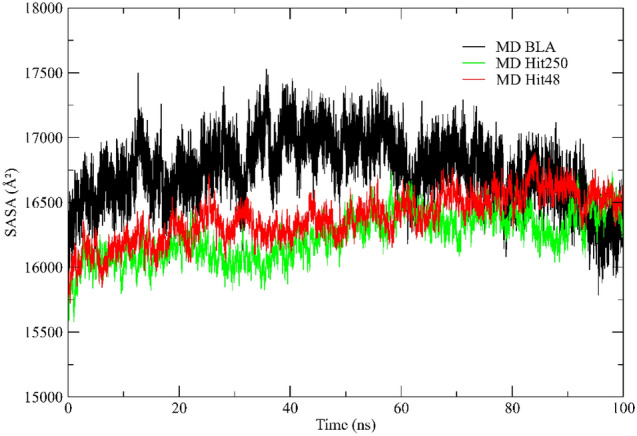

Solvent accessible surface area

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) is defined as the surface area of a protein that interacts with its solvent molecules (Mazola et al. 2015). Average SASA values for free BLA, Hit 250, and Hit 48 complexes were monitored during 100 ns MD simulations. The traces for the SASA in Fig. 10 show a steep increase within 10 ns indicating structural relaxation. The average SASA values for free BLA, Hit 250, and Hit 48 complexes were found to be 16,611 Å2, 16,249 Å2, and 16,223 Å2, respectively. There was no major change observed in the SASA values due to ligand binding. After this time, the values fluctuate around a constant value. We, thus, assume that the simulation times of 100 ns were sufficient for sampling equilibrated systems. The highest SASA is found for the S-glycoprotein molecules with the stabilizing monovalent ions. The run without monovalent ions shows a large fluctuation, whereas the systems with higher ion concentrations have smaller areas and may be shrinking under the influence of the surface charge, yielding more compact protein structures. Further inspection of the data demonstrates that the fluctuation or ‘breathing’ of the relaxed surface is mainly due to a fluctuation of the SASA of the flexible C-terminal area.

Fig. 10.

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of the S-glycoprotein from the MD simulations: Hit 250 (green line), Hit 48 (red line), and BLA (Black line), all stabilizing monovalent ions

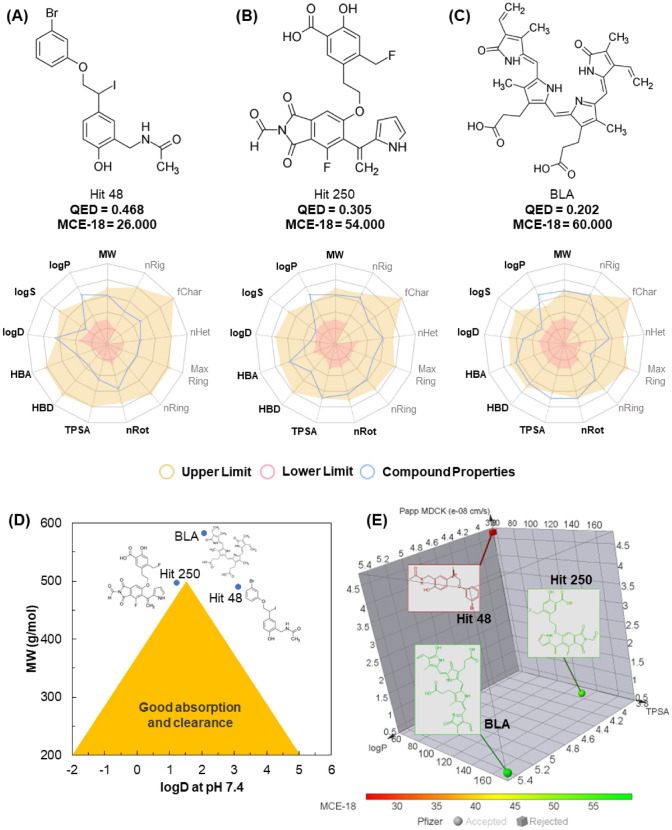

In silico ADMET study

Evaluation of druglikeness

For Wager et al. (2016), low lipophilic compounds (logP < 3) that are larger and more polar than commercially available CNS active substances (TPSA > 75 Å2) reside in a physicochemical space where in vivo toxicity is unlikely. Compounds with high lipophilicity and low polarity tend to be more toxic than safe, in addition to showing unfavorable pharmacodynamic interactions against biological targets (Hughes et al. 2008).

In the druglikeness radar of Fig. 11, it is possible to notice that the three compounds, that is, Hit 48 (Fig. 11a), Hit 250 (Fig. 11b), and the BLA ligand (Fig. 11c) move outside an ideal spectrum of mediated lipophilicity by logP, with values greater than 3.0 (Table 5). Compound Hit 48 showed low topological polarity (TPSA = 58.56 Å2) which, when combined with high lipophilicity, classified it as possibly CNS permeant toxicant, according to the Pfizer filter that combines these two attributes (Table 5).

Fig. 11.

Relationship between structure and druglikeness of Hit 48 (a), Hit 250 (b) and BLA (c), prediction of balance between absorption and clearance (d) and pharmacokinetic physical–chemical space (e)

Table 5.

Physicochemical properties and quantitative estimates of druglikeness

| Property | Hit 48 | Hit 250 | BLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical properties | |||

| logP | 3.84 | 3.98 | 5.46 |

| logD | 3.14 | 1.24 | 2.08 |

| MW | 488.94 g/mol | 496.11 g/mol | 582.25 g/mol |

| HBA | 4 | 9 | 10 |

| HBD | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| TPSA | 58.56 Å2 | 137.0 Å2 | 171.63 Å2 |

| nRot | 7 | 9 | 11 |

| nRing | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| MaxRing | 6 | 9 | 5 |

| nHet | 6 | 11 | 10 |

| fChar | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nRig | 13 | 26 | 29 |

| nStereo | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Medicinal chemistry | |||

| Pfizer rulea | 2 Alerts; logP > 3 and TPSA < 75 Å2; (–) | 1 alert; logP > 3; (+) | 1 alert; logP > 3; (+) |

| GSK filter | 1 Alert; MW > 400 g/mol; (−) | 1 Alert; MW > 400 g/mol; (−) | 2 Alerts; logP > 4 and MW > 400 g/mol; (−) |

| Golden Triangle | 0 alert; (+) | 0 alert; (+) | 1 alert; MW > 500 g/mol; (−) |

| QED | 0.468 | 0.305 | 0.202 |

| Fsp3 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| MCE-18 | 26.0 | 54.0 | 60.0 |

In highlight, properties favorable to binders

aPfizer’s rule relates logP and TPSA attributes to the physical–chemical space of the ligands: low logP and high TPSA (logP < 3 and TPSA > 75 Å2), low toxic risk; high logP and low TPSA (logP > 3 and TPSA < 75 Å2), toxic risk

It is curious to note that both Hit 48 and Hit 250 failed the GSK filter druglikeness criteria for having MW > 400 g/mol, an indication that these substances may have limited pharmacokinetics, such attributes include solubility, absorption, and stability metabolism (Gleeson 2008). However, it was possible to observe that Hit 250 passed the safety and pharmacodynamic criteria of the Pfizer rule, as it occupies a physical–chemical space where compounds with TPSA reside within the ideality spectrum (Fig. 11b).

Evaluation of MCE-18

In recent years, the molecules claimed for patents follow a physicochemical trend that deviates from the medicinal chemistry spectrum of the commonly used “rule of five”. This chemical singularity focuses on how the fraction of sp3 hydrous carbons is distributed in aliphatic structures, chiral centers, and aromatic and non-aromatic cyclic structures. In this perspective, molecules registered in patents have been shown to be slightly more lipophilic and more polar than commercially available therapeutics (Ivanenkov et al. 2019; Wager et al. 2010a, b).

In this test, it was possible to observe that QED values lower than 0.5 (on a scale ranging from 0.0 to 1.0) are directly related to the large molecular size of the ligands (MW > 400 g/mol), and are reduced as that the TPSA increases to 171.63 Å2 (BLA), depending on the number of HBA atoms (Table 5). However, the structural complexity involving the Hit 250 and BLA ligands, especially due to the total of four aromatic (or heteroaromatic) rings, including the total of nine atoms in the 2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione of the BLA complexed ligand, which yielded the ligands an MCE-18 score of 54.0 and 60.0, respectively. This finding suggests that the ligands present an excellent degree of similarity with the structural complexity of the compounds registered in patents in recent years (Table 5).

Predicted pharmacokinetic descriptors

The oral bioavailability of a drug concerns the alignment between the pharmacological portion absorbed as a function of a low rate of hepatic clearance. Pharmacological databases, such as Pfizer, Inc., estimate that a ligand exhibits high passive permeability when its in vitro Papp MDCK value is greater than 10 × 10–6 cm/s, which results in high oral bioavailability as its clearance rate decreases (van de Waterbeemd and Gifford 2003; Wager et al. 2010a, b). For Johnson et al. (2009), these descriptors are closely related to the buffer lipophilicity (logD) at pH 7.4, limited to small compounds that are not very lipophilic, that is, that occupy a physical–chemical space formed by − 2 < logD at pH 7.4 ≤ 5 and 200 < MW ≤ 500 g/mol.

In the graph in Fig. 11d, it is possible to observe that the three ligands are outside the ideality spectrum for good intestinal permeability. This empirical decision corroborates the estimated Papp MDCK descriptors, where values equal to and less than 4.7 × 10–8 cm/s suggest a low passive permeability (Table 6). However, the substances showed low susceptibility to being Pgp substrates, as an indication of good intestinal absorption, with HIA values > 90% for compounds Hit 48 and Hit 250 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Predicted pharmacokinetic descriptors from consensus testing across PreADMET, ADMETlab, ProTox-II, and pkCSM databases

| Property | Hit 48 | Hit 205 | BLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Papp MDCK | 4.70 × 10–8 cm/s | 4.35 × 10–9 cm/s | 4.34 × 10–9 cm/s |

| Pgp-sub | (–) | (–) | (–) |

| HIA | 95.92% | 91.51% | 86.78% |

| VD | 0.76 L/kg | 0.68 L/kg | 0.41 L/kg |

| PPB | 89.67% | 86.55% | 86.43% |

| BBB (C[Brain]/C[Blood]) | 2.969 | 0.029 | 0.098 |

| H-HT | (–) 0.72 | (–) 0.66 | (–) 0.75 |

| Mutagen | (–) 0.69 | (–) 0.71 | (–) 0.71 |

| LC50 Minnow | 0.02 mM | 0.32 mM | 1.86 mM |

In addition, it is possible to note the contribution of the high lipophilicity in the distribution of the compounds in the blood plasma and in the CNS. Compounds of greater lipophilicity can bind strongly with serum proteins and have their tissue distribution affected (Dyabina et al. 2016; Pires et al. 2018). In this study, it was possible to observe that the compounds presented PPB < 90%, which allows a considerable distribution in biological tissues. At the same time, the low polarity of Hit 48 makes it more susceptible to distribution in the CNS, corroborating the permeability coefficient in the BBB in the order of 2.969, which represents a ratio of the concentration of the compound in the brain by its distribution in the blood (C[Brain]/C[Blood]) (Table 6).

Metabolism and oral acute toxicity

Predicting the sites of metabolism allows us to estimate the effects of drug biotransformation on hepatic clearance and adverse effects on the human liver. Empirical analysis suggests that compounds with MW around 500 g/mol are metabolically unstable, that is, they have structural fragments susceptible to biotransformation, forming secondary metabolites that are more water soluble and more favorable to excretion. However, some biotransformations can form chemically reactive intermediates, such as epoxidation mediated by aromatic hydroxylation (Hughes et al. 2015; Johnson et al. 2009).

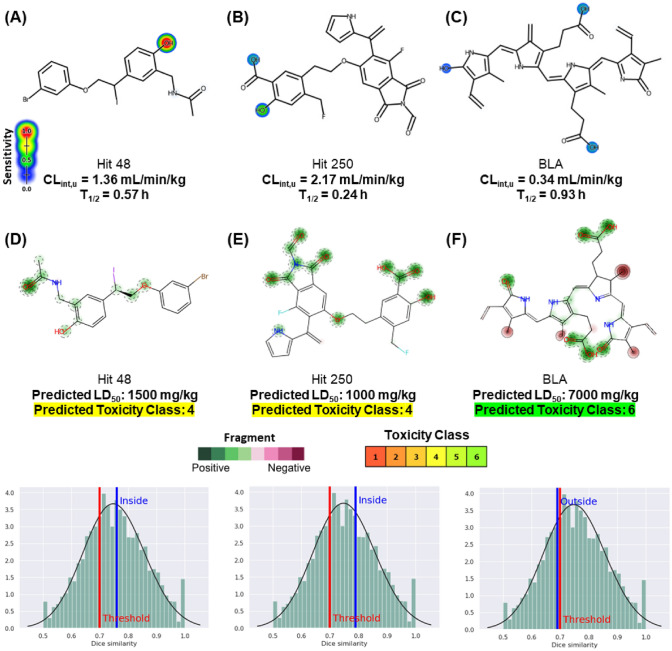

In this predictive test, the fragments are identified from a data library that relates the degree of sensitivity of the functional groups and structural fragments to be biotransformed in the human liver microsome system with the degree of specificity of these in the molecular structure (Zheng et al. 2009). Here, it was possible to observe, mainly, that the aromatic centers of the ligands do not pose a risk of hydroxylation, reducing the risk of these substances forming reactive secondary metabolites (Fig. 12a–c), which implies a low risk of human hepatotoxicity and mutagenicity (Table 6). Hit 48 has a phase II metabolism site in its phenolic hydroxyl, sensitive to conjugation reactions via UGT (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase), indicating that the substance is more resistant to phase I metabolism, with an order of CLint,u estimated at 1.36 mL/min/kg which may be indicative of good oral bioavailability (Fig. 12a). However, this metabolism pathway seeks to optimize the excretion pathway.

Fig. 12.

Metabolism site prediction of Hit 48 (a), Hit 250 (b), and BLA (c) and fragment-based acute toxicity prediction of Hit 48 (d), Hit 250 (e), and BLA (f)

A low rate of hepatic clearance implies a longer half-life (T1/2) for pharmacological action (van de Waterbeemd and Gifford 2003). This is observed when comparing the metabolism pathways of Hit 48 (Fig. 12a) and Hit 250 (Fig. 12b), where the higher incidence of metabolism sites induces a shorter T1/2 time to Hit 250, estimated at 0.24 h, depending on its highest clearance order compared to Hit 48, with an estimated CLint,u value of 2.17 mL/min/kg (Fig. 12b). In the probability maps of Figs. 12d–f, it is possible to observe that the metabolism sites are within the positive contributions that reduce the acute toxicity of the Hit 48 ligands (Fig. 12d) and Hit 250 (Fig. 12e), where the predicted LD50 values of 1500 mg/kg and 1000 mg/kg indicate that they are compounds of toxicity class 4 (Diaza et al. 2015), which are compounds that require control of the administered oral dose. These compounds showed an order of similarity greater than 70% (inside the threshold) with the compounds deposited in the PubMed database (Borba et al. 2022).

In addition, it is worth mentioning that Hit 250 and BLA binders showed the best LC50 values for Fathead Minnow, where values of 0.32 mM and 1.86 mM (in logarithmic scale), respectively, suggest that the minimum effective dose does not pose a risk to a fish population tested, as an indication of the safety of oral administration in humans (Table 5).

One of the limitations of de novo drug design has been that they cannot identify a perfect compound for synthesis since some of the potential Hits generated have complexity that compromises the realization of their synthesis. However, in return, they can identify high-quality ideas for future in vitro and in vivo assays. Considering the imperfections of automated chemical synthesis planning and reaction pathway design, combining AI-driven generative molecular design models with advanced synthesis and retrosynthesis algorithms could offer ample future opportunities for new molecular discoveries.

Conclusion

It was carried out through the innovative computer-aided drug design de novo, researching new drug candidates to treat Sars-Cov-2, more precisely, S-glycoprotein as a target. Therefore, an important role was played in developing new anti-COVID-19 drugs, which was of significant importance because, amid the limitation of resources, it accelerated the drug development process, reducing the time and additional costs of traditional screening. Some new derivatives of phenols and chromones were designed and studied through molecular docking, where 557 Hits were generated. The mode of binding of the proposed compounds with the target protein was evaluated, and the data from docking studies explained that some newly designed analogs had a significantly high affinity for the target protein compared to BLA as a reference linker.

The compound with the highest bioaffinity value was Hit 250, which proved to be the most potent inhibitor in this in silico study series with a binding energy of − 13.02 kcal/mol. Still, its synthetic viability was close to 50%, besides showing lower stability in the molecular dynamics analysis studies of RMSD, RMSF, and SASA. While another drew attention was Hit 48, with − 7.29 kcal/mol of affinity energy, presenting better synthetic viability, close to 80%, and better stability in the study of molecular dynamics, compared to the reference drug BLA, with the binding affinity of − 8.1 kcal/mol. In the ADMET tests, Hit 250 showed greater similarity with species registered in patents and stands out concerning Hit 48, for occupying a physical–chemical space with a low toxic incidence in vivo, due to its high polarity. Therefore, it is suggested that these compounds can be used in clinical trials to test their effectiveness for social benefits as a standard for future projects, optimization, and research in producing more effective analogs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Brazilian Agencies: Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (FUNCAP) (PNE-0112-00048.01.00/16), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, 308452/2022-4, 304152/2018-8) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Ensino Superior (CAPES, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Finance Code 001: PROEX 23038.000509/2020-82) for fellowships and financial supports. The authors used resources of the Centro Nacional de Processamento de Alto Desempenho da UFC (CENAPAD-UFC), that was essential for this work, for which the authors are grateful.

Funding

Hélcio Silva dos Santos acknowledges financial support from the PQ-BPI/FUNCAP (Grant#: BP4-0172-00075.01.00/20).

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors also declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Joan Petrus Oliveira Lima, Email: petrus.lima@uece.br.

Aluísio Marques da Fonseca, Email: aluisiomf@unilab.edu.br.

Gabrielle Silva Marinho, Email: gabrielle.marinho@uece.br.

Matheus Nunes da Rocha, Email: matheusndarocha@gmail.com.

Emanuelle Machado Marinho, Email: emanuellemarino@gmail.com.

Helcio Silva dos Santos, Email: helciodossantos@gmail.com.

Rafael Melo Freire, Email: rafael.melo@inia.cl.

Emmanuel Silva Marinho, Email: emmanuel.marinho@uece.br.

Pedro de Lima-Neto, Email: pln@ufc.br.

Pierre Basílio Almeida Fechine, Email: fechine@ufc.br.

References

- Ahmadi M, Jahed Motlagh M, Rahmani AT, Zolfagharzadeh MM, Shariatpanahi P, Chermack TJ, Coons LM, Cotter J, Eyiah-Donkor E, Poti V, Derbyshire J, Dolan TE, Fuller T, Kishita Y, McLellan BC, Giurco D, Aoki K, Yoshizawa G, Handoh IC, Bose S. Chem3D 15.0 user guide. Macromolecules. 2005;24(2):1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Arshia AH, Shadravan S, Solhjoo A, Sakhteman A, Sami A. De novo design of novel protease inhibitor candidates in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 using deep learning, docking, and molecular dynamic simulations. Comput Biol Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J, Walters MA. Chemistry: chemical con artists foil drug discovery. Nature. 2014;513(7519):481–483. doi: 10.1038/513481a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Q, Tan S, Xu T, Liu H, Huang J, Yao X. MolAICal: a soft tool for 3D drug design of protein targets by artificial intelligence and classical algorithm. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(3):1–12. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet, et al. BDDCS, the rule of 5 and drugability. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerton GR, Paolini GV, Besnard J, Muresan S, Hopkins AL. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat Chem. 2012;4(2):90–98. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biovia (2015) Dassault Systemes, BIOVIA Discovery Studio Modelling Environment, Release 4.5. San Diego: Dassault Systèmes

- Borba JVB, Alves VM, Braga RC, Korn DR, Overdahl K, Silva AC, Hall SUS, Overdahl E, Kleinstreuer N, Strickland J, Allen D, Andrade CH, Muratov EN, Tropsha A. STopTox: an in silico alternative to animal testing for acute systemic and topical toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2022 doi: 10.1289/EHP9341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti R, Singh R, Ghosh A, Dey D, Sharma P, Velayutham R, Roy S, Ghosh D. A review on potential of natural products in the management of COVID-19. RSC Adv. 2021;11(27):16711–16735. doi: 10.1039/d1ra00644d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Sun H, Wang J, Zhu F, Liu H, Wang Z, Lei T, Li Y, Hou T. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 8. Predicting binding free energies and poses of protein-RNA complexes. RNA. 2018;24(9):1183–1194. doi: 10.1261/rna.065896.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Rocha MN, Alves DR, Marinho MM, De Morais SM, Marinho ES. Virtual screening of citrus flavonoid tangeretin: a promising pharmacological tool for the treatment and prevention of Zika fever and COVID-19. J Comput Biophys Chem. 2021;20(3):283–304. doi: 10.1142/S2737416521500137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha MN, Marinho MM, Teixeira AMR, Marinho ES, dos Santos HS. Predictive ADMET study of rhodanine-3-acetic acid chalcone derivatives. J Indian Chem Soc. 2022;99(7):100535. doi: 10.1016/j.jics.2022.100535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira VM, Marinho MM, Magalhães EP, de Menezes RRPPB, Sampaio TL, Martins AMC, dos Santos HS, Marinho ES. Molecular docking identification for the efficacy of natural limonoids against COVID-19 virus main protease. J Indian Chem Soc. 2021;98(10):100157. doi: 10.1016/j.jics.2021.100157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaza RG, Manganelli S, Esposito A, Roncaglioni A, Manganaro A, Benfenati E. Comparison of in silico tools for evaluating rat oral acute toxicity. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2015;26(1):1–27. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2014.977819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez M, Petuya V, Martínez-Cruz LA, Hernández A. Insights into mechanism kinematics for protein motion simulation. BMC Bioinform. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong YW, Liao ML, Meng XL, Somero GN. Structural flexibility and protein adaptation to temperature: molecular dynamics analysis of malate dehydrogenases of marine molluscs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(6):1274–1279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718910115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Lima JR, Ferreira MKA, Sales KVB, da Silva AW, Marinho EM, Magalhães FEA, Marinho ES, Marinho MM, da Rocha MN, Bandeira PN, Teixeira AMR, de Menezes JESA, dos Santos HS. Diterpene Sonderianin isolated from Croton blanchetianus exhibits acetylcholinesterase inhibitory action and anxiolytic effect in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) by 5-HT system. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1991477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyabina AS, Radchenko EV, Palyulin VA, Zefirov NS. Prediction of blood-brain barrier permeability of organic compounds. Doklady Biochem Biophys. 2016;470(1):371–374. doi: 10.1134/S1607672916050173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61(8):3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl P, Schuffenhauer A. Estimation of synthetic accessibility score of drug-like molecules based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions. J Cheminform. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farago O. Langevin thermostat for robust configurational and kinetic sampling. Phys A Stat Mech Appl. 2019;534:122210. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2019.122210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira RM, Beranger RW, Sampaio PPN, Filho JM, Lima RAC. Outcomes associated with Hydroxychloroquine and Ivermectin in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a single-center experience. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2021;67(10):1466–1471. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.20210661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker PC, Gastreich M, Rarey M. Automated drawing of structural molecular formulas under constraints. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2004;44(3):1065–1078. doi: 10.1021/ci049958u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Tian T, Huang S, Wan F, Li J, Li S, Wang X, Yang H, Hong L, Wu N, Yuan E, Luo Y, Cheng L, Hu C, Lei Y, Shu H, Feng X, Jiang Z, Wu Y, Zeng J. An integrative drug repositioning framework discovered a potential therapeutic agent targeting COVID-19. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2021;6(1):1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00568-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S, Ryde ULF. How to obtain statistically converged MM/GBSA results. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(4):837–846. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S, Ryde U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015;10(5):449–461. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson MP. Generation of a set of simple, interpretable ADMET rules of thumb. J Med Chem. 2008;51(4):817–834. doi: 10.1021/jm701122q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung AB, Ali MA, Bhattacharjee A, Abul Farah M, Al-Hemaid F, Abou-Tarboush FM, Al-Anazi KM, Al-Anazi FSM, Lee J. Molecular docking of the anticancer bioactive compound proceraside with macromolecules involved in the cell cycle and DNA replication. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15(2):1–8. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15027829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanwell MD, Curtis DE, Lonie DC, Vandermeersch T, Zurek E, Hutchison GR. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform. 2012;4(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevener KE, Zhao W, Ball DM, Babaoglu K, Qi J, White SW, Lee RE. Validation of molecular docking programs for virtual screening against dihydropteroate synthase. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49(2):444–460. doi: 10.1021/ci800293n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Wang J, Li Y, Wang W. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51(1):69–82. doi: 10.1021/ci100275a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Rauscher S, Nawrocki G, Ran T, Feig M, De Groot BL, Grubmüller H, MacKerell AD. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Methods. 2016;14(1):71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JD, Blagg J, Price DA, Bailey S, DeCrescenzo GA, Devraj RV, Ellsworth E, Fobian YM, Gibbs ME, Gilles RW, Greene N, Huang E, Krieger-Burke T, Loesel J, Wager T, Whiteley L, Zhang Y. Physiochemical drug properties associated with in vivo toxicological outcomes. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(17):4872–4875. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TB, Miller GP, Swamidass SJ. Modeling epoxidation of drug-like molecules with a deep machine learning network. ACS Cent Sci. 2015;1(4):168–180. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenkov YA, Zagribelnyy BA, Aladinskiy VA. Are we opening the door to a new era of medicinal chemistry or being collapsed to a chemical singularity? J Med Chem. 2019;62(22):10026–10043. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain SK, Agrawal A. De novo drug design: an overview. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2004;66(6):721–728. [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Jiang W, Lee HS, Roux B, Im W. CHARMM-GUI ligand binder for absolute binding free energy calculations and its application. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53(1):267–277. doi: 10.1021/ci300505n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TW, Dress KR, Edwards M. Using the Golden Triangle to optimize clearance and oral absorption. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(19):5560–5564. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Nakayoshi T, Kurimoto E, Oda A. Molecular dynamics simulations for the protein–ligand complex structures obtained by computational docking studies using implicit or explicit solvents. Chem Phys Lett. 2021;781:139022. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2021.139022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kermany DS, Goldbaum M, Cai W, Valentim CCS, Liang H, Baxter SL, McKeown A, Yang G, Wu X, Yan F, Dong J, Prasadha MK, Pei J, Ting M, Zhu J, Li C, Hewett S, Dong J, Ziyar I, Zhang K. Identifying medical diagnoses and treatable diseases by image-based deep learning. Cell. 2018;172(5):1122.e9–1131.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Ahn HS, Go HJ, Kim DY, Kim JH, Lee JB, Park SY, Song CS, Lee SW, Ha SD, Choi C, Choi IS. Hemin as a novel candidate for treating COVID-19 via heme oxygenase-1 induction. Sci Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-01054-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Nyodu R, Maurya VK, Saxena SK (2020) Morphology, genome organization, replication, and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), 1rd edn. Springer, Singapore, pp 23–31. 10.1007/978-981-15-4814-7_3

- Lima AH, Souza PRM, Alencar N, Lameira J, Govender T, Kruger HG, Maguire GEM, Alves CN. Molecular modeling of T. rangeli, T. brucei gambiense, and T. evansi sialidases in complex with the DANA inhibitor. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;80(1):114–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazola Y, Guirola O, Palomares S, Chinea G, Menéndez C, Hernández L, Musacchio A. A comparative molecular dynamics study of thermophilic and mesophilic β-fructosidase enzymes. J Mol Model. 2015;21(9):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00894-015-2772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao R, Xia LY, Chen HH, Huang HH, Liang Y. Improved classification of blood–brain-barrier drugs using deep learning. Sci Rep. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44773-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen E, Bannon D, Kudo T, Graf W, Covert M, Van Valen D. Deep learning for cellular image analysis. Nat Methods. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olleveant NA, Humphris G, Roe B. How big is a drop? a volumetric assay of essential oils. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8(3):299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onufriev A, Bashford D, Case DA. Modification of the generalized born model suitable for macromolecules. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104(15):3712–3720. doi: 10.1021/jp994072s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova SS, Solov’Ev AD. The origin of the method of steepest descent. Hist Math. 1997;24(4):361–375. doi: 10.1006/hmat.1996.2146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires DEV, Kaminskas LM, Ascher DB (2018) Prediction and optimization of pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties of the ligand. In: Computational drug discovery and design. Humana Press, pp 271–284. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7756-7_14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rastelli G, Degliesposti G, Del Rio A, Sgobba M. Binding estimation after refinement, a new automated procedure for the refinement and rescoring of docked ligands in virtual screening. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;73(3):283–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa A, Pye VE, Graham C, Muir L, Seow J, Ng KW, Cook NJ, Rees-Spear C, Parker E, dos Santos MS, Rosadas C, Susana A, Rhys H, Nans A, Masino L, Roustan C, Christodoulou E, Ulferts R, Wrobel AG, Cherepanov P. SARS-CoV-2 can recruit a heme metabolite to evade antibody immunity. Sci Adv. 2021;7(22):1–18. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abg7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti L, Jaime Bezerra Mendonca Junior F, Rodrigo Magalhaes Moreira D, Sobral da Silva M, Pitta RI, Tullius Scotti M. SAR, QSAR and docking of anticancer flavonoids and variants: a review. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;12(24):2785–2809. doi: 10.2174/1568026611212240007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segler MHS, Preuss M, Waller MP. Planning chemical syntheses with deep neural networks and symbolic AI. Nature. 2018;555(7698):604–610. doi: 10.1038/nature25978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi FM, Mirzaei R, Nakhaee S, Nejatian A, Ghafari S, Mehrpour O. Repurposing the drug, ivermectin, in COVID-19: toxicological points of view. Eur J Med Res. 2022;27(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40001-022-00645-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shityakov S, Förster C. In silico predictive model to determine vector-mediated transport properties for the blood-brain barrier choline transporter. Adv Appl Bioinforma Chem. 2014 doi: 10.2147/AABC.S63749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Purohit R. Computational analysis of protein-ligand interaction by targeting a cell cycle restrainer. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2023;231:107367. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2023.107367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Purohit R. Multi-target approach against SARS-CoV-2 by stone apple molecules: a master key to drug design. Phytother Res. 2023 doi: 10.1002/ptr.7772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Bhardwaj VK, Purohit R. Inhibition of nonstructural protein 15 of SARS-CoV-2 by golden spice: a computational insight. Cell Biochem Funct. 2022;40(8):926–934. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stierand K, Maaß PC, Rarey M. Molecular complexes at a glance: automated generation of two-dimensional complex diagrams. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(14):1710–1716. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RS, Mahmood AR, White M. An emphatic approach to the problem of off-policy temporal-difference learning. J Mach Learn Res. 2016;17:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh Tung B, Hong Minh P, Nhu Son N, The Hai P. Screening virtual ACE2 enzyme inhibitory activity of compounds for COVID-19 treatment based on molecular docking. VNU J Sci Med Pharm Sci. 2020;36(4):1–11. doi: 10.25073/2588-1132/vnumps.4281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumskiy RS, Tumskaia AV. Multistep rational molecular design and combined docking for discovery of novel classes of inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease 3CLpro. Chem Phys Lett. 2021;780:138894. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2021.138894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Waterbeemd H, Gifford E. ADMET in silico modelling: towards prediction paradise? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(3):192–204. doi: 10.1038/nrd1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I, Mackerell AD. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(4):671–690. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagener FADTG, Pickkers P, Peterson SJ, Immenschuh S, Abraham NG. Targeting the heme-heme oxygenase system to prevent severe complications following covid-19 infections. Antioxidants. 2020;9(6):1–11. doi: 10.3390/antiox9060540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TT, Chandrasekaran RY, Hou X, Troutman MD, Verhoest PR, Villalobos A, Will Y. Defining desirable central nervous system drug space through the alignment of molecular properties, in vitro ADME, and safety attributes. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1(6):420–434. doi: 10.1021/cn100007x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TT, Hou X, Verhoest PR, Villalobos A. Moving beyond rules: the development of a central nervous system multiparameter optimization (CNS MPO) approach to enable alignment of druglike properties. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1(6):435–449. doi: 10.1021/cn100008c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TT, Hou X, Verhoest PR, Villalobos A. Central nervous system multiparameter optimization desirability: application in drug discovery. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7(6):767–775. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl J, Freyss J, von Korff M, Sander T. Accuracy evaluation and addition of improved dihedral parameters for the MMFF94s. J Cheminform. 2019;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13321-019-0371-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Greene D, Xiao L, Qi R, Luo R. Recent developments and applications of the MMPBSA method. Front Mol Biosci. 2018;4(87):1–18. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Wang Z, Sun H, Wang J, Shen C, Weng G, Chai X, Li H, Cao D, Hou T. Deep learning approaches for de novo drug design: an overview. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Hu B, Lu S, Duan R, Deng H, Li L, He L, Zhao Y, Wang J, Yu Z. Identification of raloxifene as a novel α-glucosidase inhibitor using a systematic drug repurposing approach in combination with cross molecular docking-based virtual screening and experimental verification. Carbohydr Res. 2022;511:108478. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2021.108478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Cheng F, Chen L, Du Z, Li W, Liu G, Lee PW, Tang Y. In silico prediction of chemical ames mutagenicity. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52(11):2840–2847. doi: 10.1021/ci300400a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Gu G, Zhang B, Wang Y, Bai J, Fang Y, Zhang T, Dai S, Cen S, Yu L. New phenol and chromone derivatives from the endolichenic fungus Daldinia species and their antiviral activities. RSC Adv. 2021;11(36):22489–22494. doi: 10.1039/d1ra03754d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Cai Y, Xiao T, Lu J, Peng H, Sterling SM, Walsh RM, Rits-Volloch S, Zhu H, Woosley AN, Yang W, Sliz P, Chen B. Structural impact on SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by D614G substitution. Science. 2021;372(6541):525–530. doi: 10.1126/science.abf2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Luo X, Shen Q, Wang Y, Du Y, Zhu W, Jiang H. Site of metabolism prediction for six biotransformations mediated by cytochromes P450. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(10):1251–1258. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.