Abstract

Objective

Preliminary remission criteria for gout have been developed. However, the patient experience of gout remission has not been described. This qualitative study aimed to understand the patient experience of gout remission and views about the preliminary gout remission criteria.

Methods

Semistructured interviews were conducted. All participants had gout, had not had a gout flare in the preceding 6 months, and were on urate‐lowering medication. Participants were asked to discuss their experience of gout remission and views about the preliminary remission criteria. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were analyzed using a reflexive thematic approach.

Results

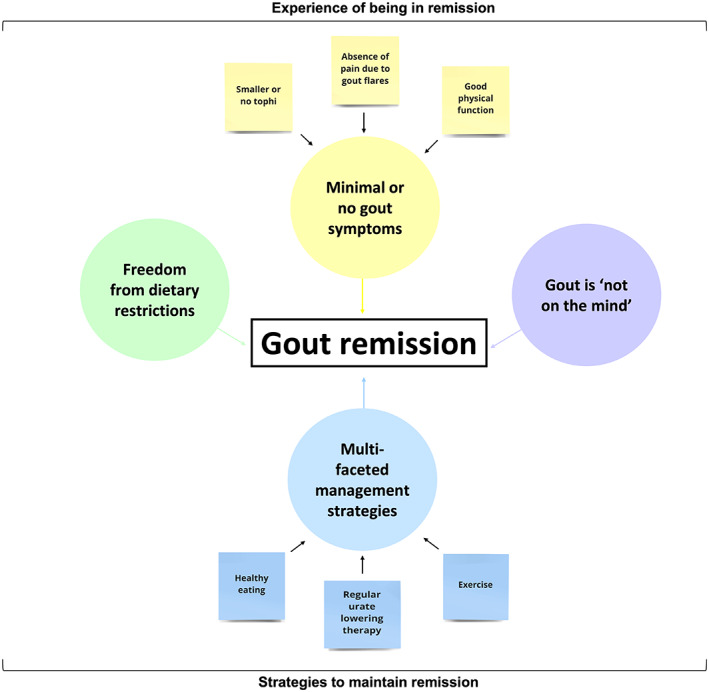

Twenty participants with gout (17 male participants, median age 63 years) were interviewed. Four key themes of the patient experience of remission were identified: 1) minimal or no gout symptoms (absence of pain due to gout flares, good physical function, smaller or no tophi), 2) freedom from dietary restrictions, 3) gout is “not on the mind”, and 4) multifaceted management strategies to maintain remission (regular urate‐lowering therapy, exercise, healthy eating). Participants believed that the preliminary remission criteria contained all relevant domains but considered that the pain and patient global assessment domains overlapped with the gout flares domain. Participants regarded 12 months as a more suitable time frame than 6 months to measure remission.

Conclusion

Patients experience gout remission as a return to normality with minimal or no gout symptoms, dietary freedom, and absence of mental load. Patients use a range of management strategies to maintain gout remission.

SIGNIFICANCE & INNOVATIONS.

Although preliminary gout remission criteria have been reported, patient perspectives about gout remission have not been described.

This qualitative study examines the patient experience of gout remission and views about the preliminary remission criteria.

Understanding how remission is experienced by patients will contribute to further refinement of gout remission criteria.

INTRODUCTION

Gout is a chronic disease caused by deposition of monosodium urate crystals in joints and other tissues. Gout typically presents as intermittent episodes of painful acute inflammatory arthritis (gout flares), with chronic gouty arthritis and tophaceous gout occurring in longstanding disease. Qualitative studies of people with gout have identified impact on physical function and daily activities, as well as isolation from social and family life (1, 2, 3, 4). Long‐term serum urate‐lowering therapy using a treat to serum urate target approach is recommended for the management of gout (5, 6).

In 2016, a preliminary definition for gout remission criteria was developed through a multinational consensus exercise of rheumatologists and researchers with an interest in gout, informed by the outcome measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) core outcome domains for long‐term gout studies (7). It was agreed that all of the following domains were required to fulfill the preliminary remission criteria for gout: absence of gout flares, absence of tophi, serum urate < 0.36 mmol/l (<6mg/dl), pain due to gout < 2 on a 0‐ to 10‐point scale, and patient global assessment of disease activity < 2 on a 0‐ to 10‐point scale. The serum urate and the patient‐reported outcome domains required measurement at least twice over a set time interval. Consensus was not achieved in the Delphi exercise for the time frame for remission, with equal responses for 6 months and 12 months (7).

Although derived from the OMERACT core outcome domains, the preliminary criteria were developed from a rheumatologist‐only perspective of remission. This is an important limitation to note because patient views about remission may not necessarily align with those of rheumatologists (8). This qualitative study aimed to understand the patient experience of gout remission and views about the preliminary gout remission criteria.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Design

This interpretivist study used a qualitative descriptive methodology, which enabled a meaningful understanding of participants’ experiences and perceptions of gout remission. This drew on the principals of naturalistic inquiry, which requires analysis of the data to be reflected in the descriptions given by participants and the findings to be reported using participants’ own words and quotes (9). An inductive approach to analysis allowed the data to determine the themes. The study team was composed of experienced researchers with expertise in gout and qualitative research as well as a person with gout as the patient research partner.

Participants

Participants were recruited through existing databases of people with gout who had volunteered for or participated in research at the Clinical Research Centre, University of Auckland, New Zealand, and consented to be contacted for future studies. Purposive sampling was used to ensure that there was broad representation in age, sex, ethnicity, and disease characteristics, including current or prior tophaceous gout. Participants were included if they had gout according to the 2015 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism gout classification criteria (10), if they had experienced no gout flares in the preceding 6 months, if they were aged 18 and older, if they were on urate‐lowering therapy, and if they were English speaking. Participants were excluded if they had cognitive impairments or other forms of inflammatory arthritis. The research team elected to recruit participants with no gout flares in the preceding 6 months rather than limiting recruitment to participants in remission according to the preliminary remission criteria to allow examination of the other domains and timelines of the remission criteria. Ethics approval was obtained from the Auckland Health Research Ethics Committee (AH24277), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection

Semistructured interviews were conducted by the same researcher (ADT‐A) who was not involved in the clinical care of the participants. Participants had the option of attending the interviews in person in a private room at the Clinical Research Centre (University of Auckland, New Zealand; 13 participants) or online via Zoom (seven participants). Demographic and clinical data were collected: age, sex, ethnicity, disease duration, number of gout flares in the last 6 and 12 months, number of tophi confirmed by a physician, most recent serum urate concentration, pain due to gout in the last month (0‐ to 10‐point scale, in which 0 was “no pain due to gout” and 10 “most severe pain due to gout”) (7), and patient global assessment of gout disease activity in the last week (0‐ to 10‐point scale, in which 0 was “very well” and 10 “very poor”) (7).

An initial interview schedule was compiled by the research team, and questions were rephrased as the interviews went on as part of a reflective approach. The main section of the interview schedule addressed the participant's experience of gout remission. An opening question of “can you tell me about your first gout attack or flare?” was used to initiate discussion about their experience of gout. In the following section, participants were told that they would be discussing gout remission. Remission was described to participants as “a state where your gout symptoms have gone away, and your gout is well controlled on medication.” This description was followed by questions such as “Do you consider yourself to be in remission—why or why not?” and “What are the main differences between when your gout was active and now in remission?” Additional prompts were used as needed to encourage discussion. In the second part of the interview, a diagram of the preliminary remission criteria was shown to participants, who were asked to share their thoughts about the domains and time frame of the criteria. They were also asked specific questions about the most suitable time frame to measure remission, any missing domains, and the relative importance of each domain. At the end of the interview, participants were asked to provide further comment about their views of gout remission and the preliminary remission criteria.

Each interview was digitally audio recorded, transcribed verbatim by ADT‐A, and anonymized to ensure participant confidentiality. Participants had the opportunity to review the transcripts for completeness and representativeness.

Sample size was determined by the anticipated high level of information power (11), which is an established sampling approach in qualitative research. Information power was achieved through 1) the clear and focused study aim, 2) the inclusion of only a specific sample of participants with well‐controlled gout, 3) an interview schedule developed by an experienced team and piloted by a patient research partner, 4) the use of prompts designed to encourage quality focused discussion, and 5) the use of reflexive thematic analysis, which is a robust method of analysis.

Data analysis

To understand the patient experience of gout remission, data were analyzed using a reflexive thematic approach (12). Using a reflexive journal, ADT‐A maintained reflexivity by reading and rereading the transcripts as well as making notes about participants’ remarks and how those remarks were understood and interpreted. This was also a part of the first step of analysis, which involves data familiarization. Data analysis and data collection occurred simultaneously, and the initial analysis informed successive data collection as concepts began to emerge. Initial coding of transcripts was completed by ADT‐A to represent distinct pieces of information and discussed with other members of the research team. Multiple iterations of coding were done as part of a recursive approach to the analysis. Coding of transcripts was done using NVivo software, Version 1.5.2 (QRS International Property). The final codes were used to construct potential themes and subthemes. This was done by grouping codes that shared an underlying meaning or concept into a theme or subtheme. The themes were reviewed and discussed by all authors. Illustrative quotes from the transcripts were selected to provide evidence for each theme and subtheme.

To explore patient views about the preliminary gout remission criteria, codes were grouped by an underlying meaning or concept, but these groups were not presented as themes.

RESULTS

Study participants

A total of 20 participants were interviewed, including 17 men with a median age of 63 years. Interviews lasted between 13 and 61 minutes. None of the participants were on antiinflammatory prophylaxis at the time of the study. Disease duration ranged from 2 to 54 years, the median serum urate concentration was 0.30 mmol/l (range 0.20 to 0.42 mmol/l), and all participants were taking allopurinol at a median dose of 300 mg/day. When asked about self‐perceived remission status, 19 (95%) of the participants believed they were in gout remission. When assessed against the preliminary gout remission criteria, 16 (80%) fulfilled the criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 20 study participants

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) years | 63 (40‐86) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |

| Male | 17 (85%) |

| Female | 3 (15%) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| African | 1 (5%) |

| Asian | 1 (5%) |

| Māori | 4 (20%) |

| NZ European | 13 (65%) |

| Pacific peoples | 1 (5%) |

| Years of education, median (range) a | 16 (10‐20) |

| Disease duration, median (range) years | 12 (2‐54) |

| Body mass index, median (range) | 29 (26‐38) |

| Serum urate concentration, median (range), mmol/l | 0.30 (0.20‐0.42) |

| Allopurinol dose, median (range), mg/day | 300 (100‐600) |

| On antiinflammatory prophylaxis, no. (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gout flares in the last 12 months, no. (%) | |

| 0 | 18 (90%) |

| ≥1 | 2 (10%) |

| Prior subcutaneous tophi, no. (%) | 5 (25%) |

| Current subcutaneous tophi, no. (%) b | 3 (15%) |

| Pain due to gout in the last month (0‐ to 10‐point scale), median (range) | 0 (0‐5) |

| Patient global assessment of gout disease activity in the last week, (0‐ to 10‐point scale), median (range) | 0 (0‐6) |

| Self‐perceived remission, no. (%) c | 19 (95%) |

| Fulfilment of preliminary remission criteria at 12 months, no. (%) c | 16 (80%) |

Abbreviation: NZ, New Zealand.

Total including primary (up to 8 years), secondary (up to 5 years), and tertiary education (up to 7 years or more).

Presence of tophi was confirmed by a physician.

Assessed at a single point in time.

Patient perceptions and experiences of remission

Four key themes were identified from the data: minimal or no gout symptoms, freedom from dietary restrictions, gout is not on the mind, and multifaceted management strategies to maintain remission. A thematic map of the themes and subthemes is shown in Figure 1, and supporting quotes for these themes are shown in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the four themes and subthemes contributing to the patient experience of gout remission.

Table 2.

Quotes supporting the “minimal or no gout symptoms” theme

| Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Absence of pain due to gout flares | “The flare ups are rare ‐ it's under control as in you know, you're not having the repeat pain the repeat flare ups” (participant 4, M). |

| “I don't have the pain that you get with gout” (participant 15, M). | |

| “Now I don't get it…no flare ups or anything” (participant 19, F). | |

| “Well, I haven't had a gout flare for 12 months at least. I get the occasional little twinge, but you know that doesn't stop me from doing anything” (participant 7, M). | |

| Good physical function | “You know before it would be hard to hold something, hold a cup or anything cause of the pain but now I can do anything, I even knit” (participant 5, F). |

| “[I can be active] I get up and go to meetings and I play golf once a week, I get up at my beach and I muck around and do my work and activity. I'm very fortunate so doesn't impact me at all as long as I can keep it under control” (participant 12, M). | |

| “At the height of the gout when its active or flares up, you can't do anything. You're pretty much chair bound, because to walk or to put pressure on it was just basically the pain was just too hard. So, it [remission]….just allows you [to go on] with normal life” (participant 17, M). | |

| Smaller or no tophi | “I feel like I'm in remission I feel like it's you know well treated and definitely the tophi are improving so that's a positive indicator” (participant 3, M). |

| “You definitely haven't gotten in remission if you are getting tophi” (participant 8, M). |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

Table 3.

Quotes supporting the “freedom from dietary restrictions” theme

| Quotes | |

|---|---|

| Freedom from dietary restrictions | “I just eat what I want to eat and drink what I want to drink, and I haven't had any [gout flares], it's great” (participant 20, M). |

| “[There is no] necessity for me to continue to just be conscious all the time of what I'm doing and what I'm eating and what the effects might be if I do something that's not right…I have what I would term a normal life” (participant 14, M). | |

| “I do eat a bit more tomato‐based meals than I used to, let's face it, life is about living you know, it'll be boring otherwise. So, I am eating a bit more of that richer food definitely” (participant 2, M). |

Abbreviation: M, male.

Table 4.

Quotes supporting the “gout is not on the mind” theme

| Quotes | |

|---|---|

| Gout is not on the mind | “[You're] back to normal, not noticing it, it's not an issue, it's not there, it's not on your mind at all” (participant 3, M). |

| “I certainly am quite reflective on what occurred previously…you're free from gout, you know, you're free from the mental kind of fatigue or stress” (participant 16, M). | |

| “There's been a lot of damage done, sort of a background of aches and pains, hips, back, but with that in context I give gout no thought whatsoever. If you've successfully treated it you are thinking about a lot of other things…as I say I give it no thought whatsoever” (participant 6, M). |

Abbreviation: M, male.

Table 5.

Quotes supporting the “multifaceted management strategies” theme

| Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Regular ULT‐serum urate lowering | “I haven't changed much always kept relatively careful about what I eat, exercise regularly and I've continued to do that, the difference is the medication” (participant 7, M). |

| “I've gotta take it to control something. I don't like the pain involved with gout, and I know that it can be easily controlled with allopurinol therefore I take it and I'm very religious with it. I just take it every morning without fail” (participant 8, M). | |

| “I've got a pattern, put my pill in my pocket and put my hand in there and if it's still there at lunchtime I know I gotta take it, but yeah, I'm pretty good I don't miss” (participant 12, M). | |

| Exercise | “If I don't exercise, I'm gonna get gout flares once again…It's good to know that it can be managed and also it all comes back down to you know your well‐being and your fitness levels and your health because I've looked after myself the last year, so I've had zero flares as a result” (participant 4, M). |

| “I think it is a really good idea to do lots of walking and to exercise…I've now got really much fitter; much fitter and I just think that that must have helped” (participant 9, F). | |

| “[I am] back to cycling now so that that actually helps” (participant 17, M). | |

| Healthy eating | “I'm way more conscious about diet because that is a controlling factor that I do have absolute control over…we have a lot of vegetable‐based meals now and you know, just try and help ourselves or help me a little bit” (participant 11, M). |

| “I've cut a lot of the foods, fast foods and fatty foods and added a lot of lot more fruit and vegetables to the diet” (participant 14, M). | |

| “I still think you know to a certain degree, if you live a healthy lifestyle as well, certainly is going to help” (participant 16, M). |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; ULT, urate lowering therapy.

Minimal or no gout symptoms

The first theme, “minimal or no gout symptoms,” included the following subthemes: 1) absence of pain due to gout flares, 2) good physical function, and 3) smaller or no tophi.

Absence of pain due to gout flares

Participants described that in the past, their pain due to gout had been caused by gout flares. In remission, participants did not experience severe and frequent pain caused by gout flares (Table 2). Because pain was the primary symptom of their gout, participants believed that this absence was a key aspect of being in remission. For some participants, there were rare cases of mild discomfort, such as a “twinge” or “tickle,” in remission; however, these did not have any impact on day‐to‐day life.

Good physical function

Good physical function was described by participants as being able to perform day‐to‐day activities, sporting activities, and social commitments without the pain associated with gout (Table 2). Participants compared their physical function in remission to times when they had severe and frequent gout flares, noting improvements in their ability to move around and be active. Good physical function contributed to the feeling of normality.

Smaller or no tophi

Although absence of tophi was considered a key component of remission, participants felt they were in remission if they could observe their tophi decreasing in size or disappearing (Table 2).

Freedom from dietary restrictions

The second theme was experienced by participants as dietary freedom. In remission, participants had confidence to eat and drink more of the foods and beverages that had been dietary triggers and had been restricted when their gout was active (Table 3). They were able to eat more of the foods that they enjoyed but had avoided. Participants experienced freedom in eating foods that had previously been dietary triggers as a sign of successful treatment because it contributed to a sense of normality, and they no longer had to be continually aware and cautious of what they ate.

Gout is not on the mind

The third theme identified from participants was “gout is not on the mind.” Because of the experience of having minimal or no gout symptoms, participants no longer believed their gout to be a major issue, and as such, it was not on the mind. Participants described the lack of worry and awareness about their gout as important to the experience of being in remission. In remission, participants viewed their gout as being gone, not only in a physical sense but also mentally, without the need to be constantly conscious of gout (Table 4).

Multifaceted management strategies for remission

Central to the patient experience of remission was being able to identify and accept factors that contribute to remission. The fourth theme of “multifaceted management strategies for remission” included the subthemes of 1) regular urate‐lowering therapy, 2) exercise, and 3) healthy eating.

Regular urate‐lowering therapy

Participants strongly attributed remission to the regular use of urate‐lowering medication. They expressed that their gout symptoms would return if they stopped taking the medication. Participants described high adherence to urate‐lowering therapy, mentioning that they made sure to take their medication every day (Table 5). They also commented on having strategies to support adherence.

Although regular urate‐lowering therapy was seen as important, participants also described other health strategies to maintain gout remission.

Exercise

With improved physical function due to absence of gout symptoms came the ability to exercise more. In turn, participants viewed a good level of fitness as a contributing factor to maintaining gout remission (Table 5). This included taking long walks, cycling, or going to the gym.

Healthy eating

In conjunction with exercise, participants also described a healthy diet as another strategy used to maintain remission. This included eating in moderation and, in some instances, eliminating some unhealthy foods from their diet and adding more vegetables (Table 5).

Views about the preliminary remission criteria

Participants were asked to share their views and opinions about the preliminary remission criteria. The criteria were well understood by participants. They considered the domains to be relevant and did not identify any additional domains.

“Well, that's me, that sums me up perfectly” (participant 1, male).

“I think the five things that you've got there cover it very well” (participant 8, male).

However, participants considered that the pain due to gout and absence of gout flares domains were overlapping and were measuring the same concept.

“‘Cause you can't have one [gout flare + pain] without the other” (participant 2, male).

“Well, they're quite symbiotic, right? So, if you think about no gout flares, well then, the pain score might be irrelevant. Because you get a flare then you have pain, if you have no flares then you got no pain” (participant 4, male).

“If you have no flare ups, you've got no pain it sort of answers itself” (participant 13, male).

Similarly, participants considered that the patient global assessment and pain due to gout domains covered the same concepts and would be redundant in the absence of gout flares.

“If you don't have any gout flares, you're not going to have a pain score in my opinion and your well‐being and disease activity assessment would be at zero as well” (participant 4, male).

“Well, I think possibly you could combine it [pain due to gout] with the wellness one, there seems to me to be a level of duplication” (participant 7, male).

“If you haven't got the pain the well‐being it's also, you know, it's zero” (participant 9, female).

Participants considered that the 12‐month time frame was the best option for defining remission as it provided greater certainty about the disease state.

“I think just based on my personal experience that it should be at least a year” (participant 3, male).

“That [6 months] could work also, but I think the 12 months is probably a better indicator of people who've got totally under control” (participant 8, male).

“If you're going to, if you're going to say you haven't got gout that would mean surely that you haven't got it for at least a year” (participant 14, male).

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study provides new insights into how people with gout experience life in a remission state and what it means to be in remission. “Minimal or no gout symptoms,” “freedom from dietary restrictions,” “gout is not on the mind,” and “multifaceted management strategies for remission” are key themes that describe the patient experience of remission.

An absence of gout flares was the strongest indicator of remission for participants. This is consistent with previous research showing that flare frequency contributes to the patient perception of disease control or low disease activity (8, 13). A gout flare is experienced as severe joint pain, and as such, participants in this study experience the absence of gout flares as an absence of pain due to gout. Pain has been described by people with gout as the defining symptom of gout and the cause of a diminished quality of life and activity limitation (14, 15). In prior qualitative studies exploring the patient experience of living with gout, it has been reported that pain due to gout places limitations on physical function and affects participation in work, social, sporting, and leisurely activities (2, 3, 4, 16, 17). In contrast, this study highlights that with the absence of pain due to gout flares, participants are not impacted by their gout and are able to engage in their activities, which is an essential aspect of gout remission.

The avoidance of foods, specifically those that trigger gout flares, is common in people with gout (2, 4, 17, 18). A previous qualitative study from Liddle et al (18) that explored the modification of diet by people with gout reported that participants made changes to their diet with the belief that this would control the timing and frequency of gout flares. In our study, participants reported that in remission, they ate and drank what they enjoyed without fear of triggering a gout flare. Associated with dietary freedom was the understanding by participants that their gout could not be solely controlled by their dietary choices and that urate‐lowering medication was the most important factor. Having increased dietary options without the onset of gout flares also improved participants’ well‐being because they become less anxious about their dietary intake. Dietary freedom is an important aspect of the patient experience of gout remission because it plays an integral role in the feeling of normality and improved mental well‐being.

Absence of mental load contributed greatly to participants’ experience of remission. This is represented in the theme of “gout is not on the mind.” When in remission, participants no longer about their gout and were no longer worried or stressed about it. This contrasts with themes identified in prior qualitative studies of people with gout in which participants reported feeling worried about gout and possible attacks during intercritical periods (3, 4). Absence of frequent, unpredictable, and severe gout flares enabled patients in remission to have greater certainty in their disease control, which in turn reduced the mental load associated with gout. A major contributing factor to no longer having gout on the mind or worrying about gout is the knowledge participants have about how they can manage and maintain the remission or well‐controlled state they are in.

Adherence to urate‐lowering medication is an important factor in the long‐term management of gout. This study only recruited participants who were on urate‐lowering medication. Furthermore, participants in this study had volunteered for or had previously participated in gout research, and as such, had been educated on the importance of urate‐lowering medication. This may account for why participants in this study strongly attributed their achievement and maintenance of remission to urate‐lowering medication. However, the importance of urate‐lowering therapy has been highlighted by other people with gout in qualitative studies exploring medication adherence. In a qualitative study, Singh (19) highlighted participants with high adherence to urate‐lowering therapy, noting that they adhered to their medication to prevent gout flares and to control their gout. This is consistent with the perspectives of the participants in our study who had the understanding that regular urate‐lowering therapy was beneficial for the long‐term management of their gout. Although adherence to urate‐lowering therapy was acknowledged as a very important component of gout remission, participants in this study adopted a range of strategies, such as exercise and diet management, to maintain remission. These self‐management strategies have also been reported in other qualitative studies of people with gout and are central to participants’ control of their gout (20, 21).

The preliminary gout remission criteria were directly informed by the OMERACT core outcome domains for long‐term gout, which were developed with patient research partners (22). However, the preliminary gout remission criteria were developed without specific input from patients. The current study has provided important new perspectives about definitions for gout remission. The preliminary gout remission criteria were well understood by participants, and no other relevant domains were identified. However, participants did question the relevance of the pain and patient global assessment domains in the absence of gout flares and whether these domains were overlapping or measuring the same construct. Previous analysis of individual remission domains in a cross‐sectional dual‐energy computed tomography study showed that there was modest overlap between gout remission domains; pain and patient global assessment showed the highest overlap in 50.7% of participants (23). However, in that study, the pain and patient global assessment domains were measured at a single time point instead of at least twice over a set time interval as required in the preliminary remission criteria. Further work will examine whether these domains overlap in longitudinal studies and how different definitions of remission perform over time. An additional important finding in this study was the patient view that the longer time frame of 12 months is preferred when considering whether a person with gout is in remission. This finding indicates that, if possible, a time frame of 12 months should be used to measure gout remission.

A strength of this study was the purposeful sampling to ensure a broad representation of participants across demographic and clinical characteristics of gout, providing diverse patient perspectives and experiences of gout remission. A potential limitation of this study was the wide range of disease duration among our participants, some with long disease duration, which may have resulted in recall bias from some participants when asked to compare their perceived remission state to the past when their gout was more active. A limitation of this study is its generalizability to the wider population of people with gout. Participants recruited for this study had volunteered for or participated in previous gout research, and as such, they may have had greater understanding about gout and the role of urate‐lowering therapy compared with the general population of people with gout. Furthermore, participants in this study had been on allopurinol, and people on febuxostat or uricosuric medication were not included. As part of our purposeful sampling approach, we tried to ensure there was recruitment of people with well‐controlled gout across different ethnic backgrounds; however, most of our participants were New Zealand European. The composition of our sample population, which included fewer Indigenous peoples, may potentially reflect inequitable outcomes in gout management in Aotearoa New Zealand, which is well documented (24, 25).

In conclusion, people with gout experience remission as a return to normality with minimal or no gout symptoms, dietary freedom, and absence of mental load. People with gout use a range of management strategies to maintain gout remission.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Dalbeth had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Tabi‐Amponsah, Stewart, Hosie, Dalbeth.

Acquisition of data

Tabi‐Amponsah, Horne, Dalbeth.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Tabi‐Amponsah, Stewart, Dalbeth.

Supporting information

Disclosure form

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants who generously gave their time to take part in this study. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Auckland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Auckland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Miss. Tabi‐Amponsah's work was supported by a University of Auckland Health Research Doctoral Scholarship.

Author disclosures are available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr2.11579.

REFERENCES

- 1. Garcia‐Guillen A, Stewart S, Su I, et al. Gout flare severity from the patient perspective: a qualitative interview study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2022;74:317–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seow LL, Jiao N, Wang W, et al. A qualitative study exploring perceptions of patients with gout. Clin Nurs Res 2020;29:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lindsay K, Gow P, Vanderpyl J, et al. The experience and impact of living with gout: a study of men with chronic gout using a qualitative grounded theory approach. J Clin Rheumatol 2011;17:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coulshed A, Nguyen AD, Stocker SL, et al. Australian patient perspectives on the impact of gout. Int J Rheum Dis 2020;23:1372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzgerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:879–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence‐based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Lautour H, Taylor WJ, Adebajo A, et al. Development of preliminary remission criteria for gout using Delphi and 1000Minds consensus exercises. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dalbeth N, Frampton C, Fung M, et al. Predictors of patient and physician assessments of gout control. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023;75:1287–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ann Cutler N, Halcomb E, Sim J. Using naturalistic inquiry to inform qualitative description. Nurse Res 2021;29:29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2557–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 2016;26:1753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Byrne D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke's approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Quant 2022;56:1391–412. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor W, Dalbeth N, Saag KG, et al. Flare rate thresholds for patient assessment of disease activity states in gout. J Rheumatol 2021;48:293–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tatlock S, Rüdell K, Panter C, et al. What outcomes are important for gout patients? In‐depth qualitative research into the gout patient experience to determine optimal endpoints for evaluating therapeutic interventions. Patient 2017;10:65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chandratre P, Mallen CD, Roddy E, et al. “You want to get on with the rest of your life”: a qualitative study of health‐related quality of life in gout. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:1197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Te Karu L, Bryant L, Elley CR. Maori experiences and perceptions of gout and its treatment: a kaupapa Maori qualitative study. J Prim Health Care 2013;5:214–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh JA. The impact of gout on patient's lives: a study of African‐American and Caucasian men and women with gout. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liddle J, Richardson JC, Hider SL, et al. ‘It's just a great muddle when it comes to food': a qualitative exploration of patient decision‐making around diet and gout. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2021;5:rkab055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh JA. Facilitators and barriers to adherence to urate‐lowering therapy in African‐Americans with gout: a qualitative study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Howren A, Cox SM, Shojania K, et al. How patients with gout become engaged in disease management: a constructivist grounded theory study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singh JA, Herbey I, Bharat A, et al. Gout self‐management in African American veterans: a qualitative exploration of challenges and solutions from patients' perspectives. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:1724–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schumacher HR, Taylor W, Edwards L, et al. Outcome domains for studies of acute and chronic gout. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2342–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dalbeth N, Frampton C, Fung M, et al. Concurrent validity of provisional remission criteria for gout: a dual‐energy CT study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dalbeth N, Dowell T, Gerard C, et al. Gout in Aotearoa New Zealand: the equity crisis continues in plain sight. N Z Med J 2018;131:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dalbeth N, House ME, Horne A, et al. The experience and impact of gout in Māori and Pacific people: a prospective observational study. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:247–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclosure form