Key Points

-

•

Telomere content is increased in TP53-mutated AML/MDS compared with other AMLs, implicating altered telomere maintenance for pathogenesis.

-

•

Alterations of ETV6 and NF1 are frequent cooperating events in TP53-mutated AML/MDS.

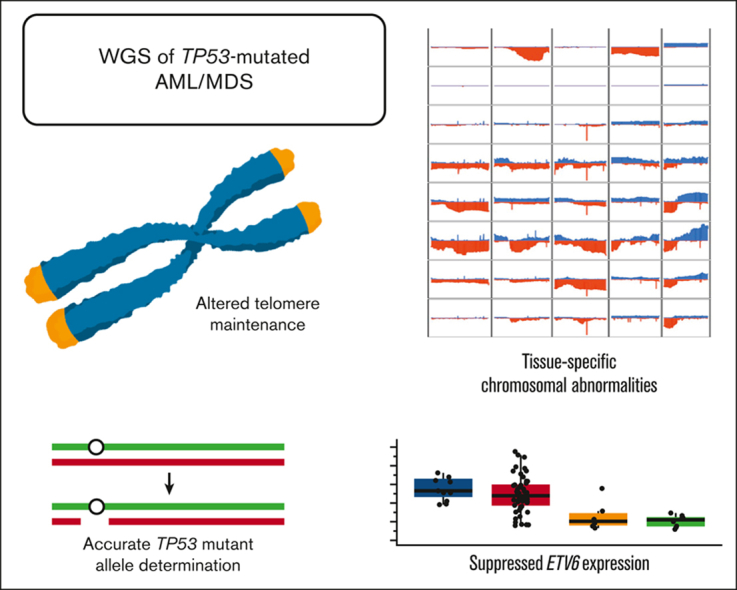

Visual Abstract

Abstract

TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies are associated with complex cytogenetics and extensive structural variants, which complicates detailed genomic analysis by conventional clinical techniques. We performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of 42 acute myeloid leukemia (AML)/myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) cases with paired normal tissue to better characterize the genomic landscape of TP53-mutated AML/MDS. WGS accurately determines TP53 allele status, a key prognostic factor, resulting in the reclassification of 12% of cases from monoallelic to multihit. Although aneuploidy and chromothripsis are shared with most TP53-mutated cancers, the specific chromosome abnormalities are distinct to each cancer type, suggesting a dependence on the tissue of origin. ETV6 expression is reduced in nearly all cases of TP53-mutated AML/MDS, either through gene deletion or presumed epigenetic silencing. Within the AML cohort, mutations of NF1 are highly enriched, with deletions of 1 copy of NF1 present in 45% of cases and biallelic mutations in 17%. Telomere content is increased in TP53-mutated AMLs compared with other AML subtypes, and abnormal telomeric sequences were detected in the interstitial regions of chromosomes. These data highlight the unique features of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies, including the high frequency of chromothripsis and structural variation, the frequent involvement of unique genes (including NF1 and ETV6) as cooperating events, and evidence for altered telomere maintenance.

Introduction

Myeloid malignancies with complex cytogenetics have adverse prognostic risk,1 and TP53 mutations are present in ∼70% of such cases.2 Extensive structural variation makes it difficult to completely characterize their genomes using standard clinical techniques for diagnosis and risk stratification,1,3 such as karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), targeted sequencing panels, and immunohistochemistry. Multiple genomic alterations of the TP53 locus indicate extremely poor prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).4 Although “multihit” TP53 events may be detected by sequencing panels and cytogenetics, they are limited in resolution and generally rely on indirect evidence, such as high variant allele frequency (VAF) in sequencing panels (ie, exceeding 50%,1,3 55%,5 or 60%6), and cannot deconvolute the effects of purity, ploidy, or clonality. Alternate approaches include DNA microarray but small copy-number changes or complex structural events remain undetected with this method. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) with adequate genome coverage can detect nearly all copy-number changes, structural variants (SV), single nucleotide variants (SNV), and small insertion/deletions (indels) in a tumor in an unbiased fashion, that is not limited to specific probes on FISH or sequencing panels.7

The pathogenesis of TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and MDS is still unclear. We, and others, previously reported that TP53 mutations are present years before the development of therapy-related TP53-mutated AML/MDS, suggesting that TP53 mutations initiate events.8, 9, 10 Multiple previous studies have shown that TP53 mutations are associated with aneuploidy and chromothripsis in both myeloid and other malignancies. Moreover, previous studies have shown that driver mutations commonly seen in other types of AML, such as mutations in DNMT3A, NPM1, and FLT3, are uncommon in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies, suggesting that SV, including chromosome-level alterations, are providing the cooperating events needed for leukemic transformation.

To characterize the genomic landscape more thoroughly in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies, we performed WGS on matched tumor/normal pairs from 42 patients. To our knowledge, these data provide the most detailed analysis to date of SV in TP53-mutated AML/MDS and yielded several new observations, including the identification of NF1 and ETV6 mutations as frequent cooperating events, and evidence for altered telomere maintenance.

Methods

Patient selection

All patients provided written informed consent for tissue repository and genomic sequencing in accordance with protocol #201011766 approved by the Washington University institutional review board. Cases were selected from patients with known pathogenic mutations or structural rearrangements in TP53 with available material from both tumor and normal tissue. Bone marrow aspirates were used for tumor analysis when available, otherwise peripheral blood was used. Skin or buccal samples were used for matched normal specimens.

WGS and RNA sequencing

WGS was performed as previously described.7 Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq S4 with 150–base pair paired end reads, targeting 60× coverage for tumors and 30× for matched normal samples. Sequencing depth and sample purity metrics for each case are summarized in supplemental Table 1. Estimated tumor purity of >20% (based on somatic VAFs) was required for inclusion.

Sequence data were aligned against reference sequence GRCh38 using BWA-MEM.11 Aligned reads were sorted, deduplicated, and recalibrated by base quality score. SNVs and small indels were detected using MuTect2,12 VarScan2,13 Strelka2,14 and GATK.15 SV were called using GRIDSS2.16 PURPLE was used for copy-number calling and detection of copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH).17 LINX was used for clustering of SV into complex variants.18 Chromothripsis was assessed with ShatterSeek.19 Telomeric content was assessed with TelomereHunter.20 Detection of telomeric insertions in intrachromosomal sequence was performed, as previously described.21 Refer to supplemental Methods for full details of variant calling and telomere analysis.

RNA sequencing was performed as described in supplemental Methods.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patient cohorts

We performed WGS on 42 samples from patients with TP53-mutated AML or MDS. Cases were selected from patients with pathogenic mutations or structural rearrangements in TP53 identified through panel sequencing, WGS, or cytogenetics at Washington University, including both previously published7,22,23 and newly identified cases. Paired normal tissue from each patient was used to ensure accurate distinction of somatic and germ line variants. Analysis was performed on diagnostic specimens obtained before treatment in all cases of AML and in 10 of 13 cases of MDS. As a comparator, we analyzed 18 cases of AML with core-binding factor (CBF) translocations, which have defined structural alterations, inv(16) with CBFB::MYH11 or t(8;21) with RUNX1::RUNX1T1 fusions, and lack TP53 mutations or complex cytogenetics.

The demographics of the cohort, including age, sex, ethnicity, blood counts, blast percentages, and prior treatment are summarized in Table 1. Detailed characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table 2, and full clinical descriptions are provided for each case in supplemental Materials. The clinical characteristics of these groups were generally well matched, although patients with CBF AML were significantly younger (P < .01, t test) with higher white blood cell counts (P < .01, t test) and higher peripheral blast percentages (P < .01, t test) than in patients with TP53-mutated AML.

Table 1.

Clinical summary of myeloid malignancy cases

| Cohort |

TP53 |

CBF |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | AML, n = 29 | MDS, n = 13 | AML, n = 18 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 66% (19) | 31% (4) | 56% (10) |

| Female | 34% (10) | 69% (9) | 44% (8) |

| Age, y, mean (range) | 65.7 (26-81) | 61.3 (41-85) | 45.5 (20-76) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 97% (28) | 100% (13) | 100% (18) |

| African American | 3% (1) | ||

| WBC, mean (103 cells per μL) | 9.3 | 5.0 | 34.0 |

| BM blast %, mean | 54% | 7% | 56% |

| PB blast %, mean | 14% | 2% | 39% |

| Subtype | |||

| M0 | 17% (5) | ||

| M1 | 14% (4) | 11% (2) | |

| M2 | 17% (5) | 33% (6) | |

| M4 | 10% (3) | 50% (9) | |

| M5 | 6% (1) | ||

| M6 | 10% (3) | ||

| M7 | 3% (1) | ||

| MRC | 14% (4) | ||

| Not categorized | 14% (4) | ||

| Excess blasts | 77% (10) | ||

| Multilineage dysplasia | 10% (3) | ||

| Therapy related | 3% (1) | 38% (5) | |

| Secondary to MDS | 10% (3) | ||

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Complex | 90% (26) | 100% (13) | |

| inv(3) | 3% (1) | ||

| del(Y) | 3% (1) | ||

| inv(16) | 67% (12) | ||

| t(8;21) | 28% (5) | ||

| Incomplete | 3% (1) | 6% (1) | |

| Previous treatment | |||

| None | 100% (29) | 77% (10) | 100% (18) |

| Hypomethylating agent | 15% (2) | ||

| Lenolidomide | 8% (1) | ||

| TP53status | |||

| Concordant: multihit | 93% (27) | 69% (9) | |

| Discordant: monoallelic → multihit | 7% (2) | 23% (3) | |

| Ambiguous → monoallelic | 8% (1) | ||

BM, bone marrow; MRC, myelodysplastic-related changes; PB, peripheral blood; WBC, white blood cell count.

One patient had a clinical history of Li-Fraumeni syndrome, who presented with therapy-related MDS with excess blasts. An additional patient who presented with de novo AML had a germline frameshift variant in CHEK2 (ENST00000328354.10:c.1100del), a pathogenic variant in Li-Fraumeni syndrome-2.24 No other pathogenic germline variants in cancer-predisposing genes were identified in the cohort.

WGS improves the ability to identify mutations in the TP53 gene

TP53 mutant allele status is an important prognostic factor. Biallelic TP53 mutation, of all copies of the gene, with no remaining wild-type allele, is associated with decreased survival in MDS.4,5 Proving that 2 mutations affect separate alleles is difficult, therefore, in the absence of definitive proof, the term multihit is generally used for cases with either 2 distinct TP53 mutations, a single mutation with chromosome 17p loss on karyotyping, or a single TP53 mutation with high VAF on panel sequencing (with varying threshold requirements of 50%,1,3 55%,5 or 60%6). Applying these conventional criteria to our cases (sequencing VAF > 55%, and cytogenetics), 93% of these AML cases and 69% of MDS cases were initially classified as multihit (Table 1); all events were confirmed by WGS. By adding WGS analysis, 5 additional cases (12%, 2 AML and 3 MDS) that initially appeared to be monoallelic (VAF < 50%) were found to have a second TP53 mutation. With this increased sensitivity, 94% of cases in the cohort contained multihit TP53 mutations, and the 1 remaining case (MDS with TP53 VAF of 54% and complex cytogenetics) was found to be monoallelic. Furthermore, nearly all multihit events (92%) could be confidently verified as biallelic. Multihit mutations predominantly occurred as a single SNV/indel combined either with loss of the wild-type TP53 allele (52%, n = 22), or CN-LOH (26%, n = 11; Figure 1A).

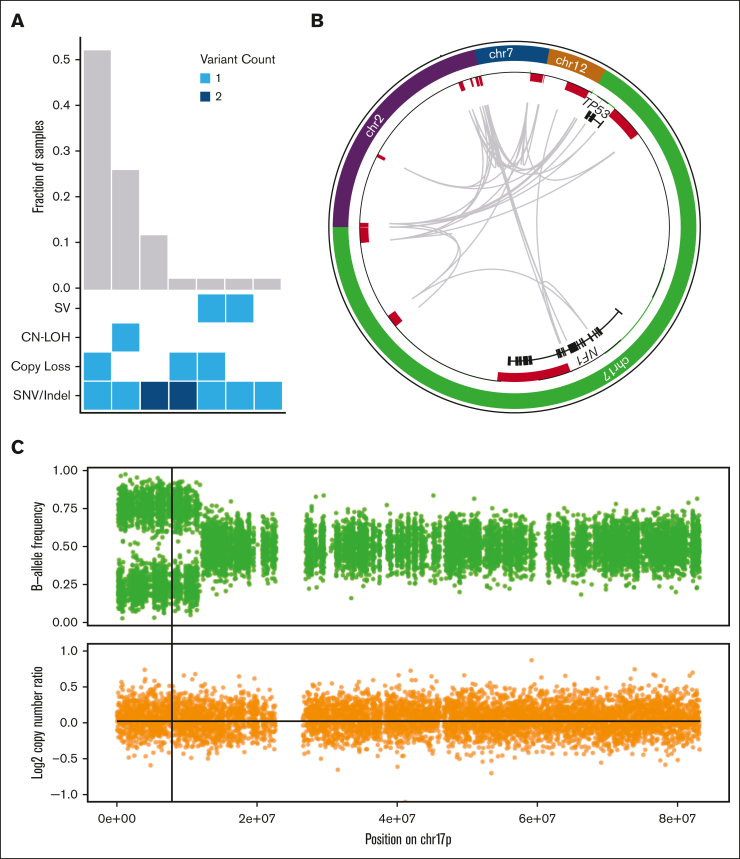

Figure 1.

WGS results in the reclassification of some cases of TP53-mutated MDS/AML. (A) Combinations of mutation types affecting TP53 in AML/MDS cases, and corresponding proportion in cohort. (B) Complex SV affecting the TP53 genetic locus is detected using WGS based on resolution of rearrangements involving ch7, chr12, chr2, and NF1 on chr17p. Copy-number losses are shown in red. Gray arcs indicate regions linked by SV. (C) CN-LOH affecting chr17p is detected using WGS based on shifts in B-allele frequency (top) whereas log2 copy-number ratio remains 0 (bottom). Vertical line indicates the position of the TP53 locus.

Examples of complex SV and CN-LOH that resulted in reclassification from monoallelic to multihit are illustrated. First, 1 patient (#480109) was previously classified as having MDS with monoallelic TP53 mutation based on VAF of 32%; cytogenetics reported “add(17)(q11.2)” with no 17p abnormality detected. With WGS, a complex SV was identified involving multiple regions on chromosomes 2, 7, 12, and 17 including the TP53 and NF1 loci (Figure 1B). Reclassification to multihit TP53 mutation increased the Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS-M) risk stratification25 from high to very high. Second, another patient (#147444) was previously classified as having MDS with monoallelic TP53 mutation based on a VAF of 48.9% and lack of a 17p abnormality on cytogenetics. WGS identified CN-LOH on 17p (Figure 1C). Reclassification to multihit TP53 mutation increased the IPSS-M stratification from moderately high to very high. In both of these cases, the presence of multihit TP53 mutations also affected the International Consensus Classification3 and the World Health Organization1 diagnostic classifications.

TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies have a distinct pattern of somatic SNVs and indels

The overall number of somatic point mutations and small indels was similar in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies and CBF AML samples (Figure 2), and neither the mutation spectrum nor signatures suggested recurrent differences in mutational processes (supplemental Figure 1). The trend toward an increased number of mutations in TP53-mutated cases may reflect the older age of this cohort compared with the patients with CBF AML. An analysis of variant allele frequencies suggests the presence of subclonal populations in all 60 cases studied (supplemental Methods).

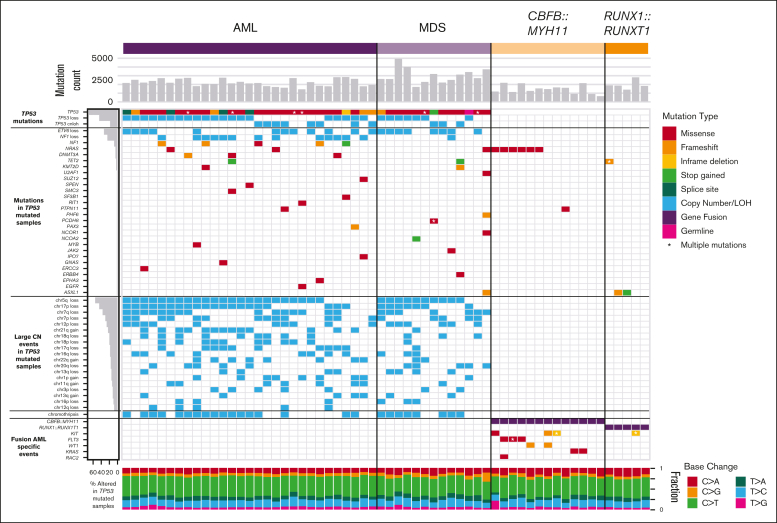

Figure 2.

Mutational landscape of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies.TP53-mutated AML (left) and MDS (middle), compared with AML driven by the CBFB::MYH11 or RUNX1::RUNX1T1 fusion proteins. Top: SNV/indel counts for each sample. Left: frequency of selected genomic alterations in TP53 samples. Middle: colors represent the types of mutations observed in each sample; asterisks indicate multiple SNV/indel hits. Bottom: proportion of each single-nucleotide base change per sample.

Cooperating mutations in TP53-mutated malignancies are distinct from other subtypes of AML. Mutations in common signaling genes KIT and FLT3, and also WT1,22,26 are absent (supplemental Table 3). Similarly, mutations in epigenetic modifiers (DNMT3A, TET2, or ASXL1) or spliceosome genes (U2AF1, SF3B1, SRSF2, or ZRSR2) are relatively uncommon, with a cumulative frequency of 14% and 4.8%, respectively. Furthermore, NRAS or KRAS mutations were present in only 7% (2 of 29) TP53-mutated AMLs vs 44% (8 of 18) CBF AMLs (P = .009). As an exception, the single case with a monoallelic TP53 mutation (a patient with MDS with excess blasts) had cooperating SNVs not seen in other cases, including ASXL1, U2AF1, and NRAS, perhaps reflecting a distinct mechanism of transformation.

AML cases with TP53 mutations were particularly enriched for comutations in NF1. SNVs, consisting mostly of frameshift or stop gains, were detected in 17.2% (5 of 29) of cases, and copy-number loss was identified in 44.8% (13 of 29) of cases. All 5 cases with SNVs also had a loss of the second NF1 allele, suggesting strong selection for multihit inactivation of NF1 in TP53-mutated AML cases.

Specific chromosome alterations in TP53-mutated malignancies from different organs

Although aneuploidy is widespread in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies, recurrent copy-number changes were evident and consistent with well-established cytogenetic changes, specifically loss of chr5, chr7, chr12, chr16, chr17, chr18, and chr20q, and gains in chr21, chr22, chr1p, and chr8 (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 2). A comparison to TP53-mutated solid tumors in the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) data set27 demonstrated striking differences in the patterns of recurrent copy-number changes (Figure 3). For example, loss of chr5q was present in >80% of the TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies in our study, compared with 58% and 38% of ovarian and esophageal adenocarcinomas, respectively, and <20% in any other tumor types. Similarly, chr7q loss was present in 56% of TP53-mutated myeloid tumors in our data set but was infrequent in all other TP53-mutated PCAWG tumor types. Conversely, some recurrent copy-number alterations that are common in other tumor types were only very rarely seen in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. For example, chromosome 6 loss was observed in <2.5% of TP53-mutated myeloid tumors but is often detected in TP53-mutated solid tumors, including ovarian (83%), pancreatic (61%), and esophageal (29%) adenocarcinomas.

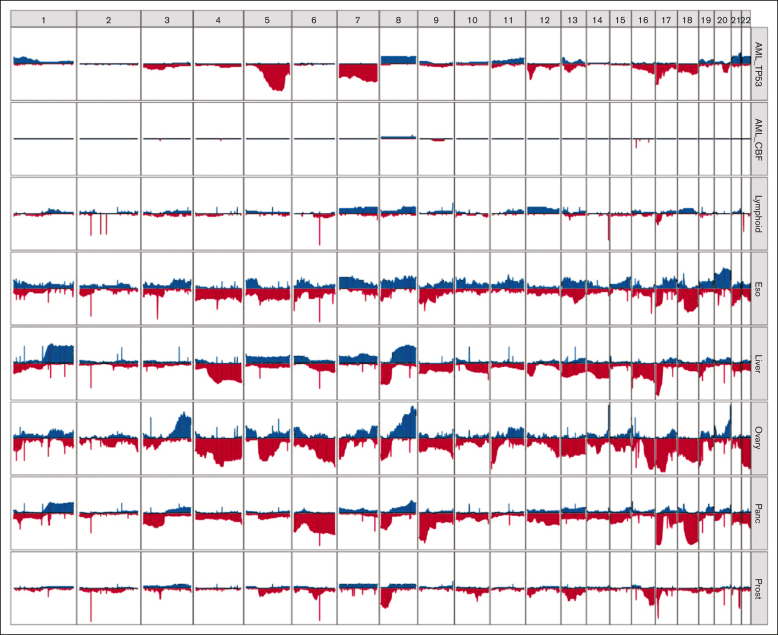

Figure 3.

Distinct patterns of copy-number alterations are observed in different TP53-mutated malignancies. The y-axis indicates the proportion of samples with a copy gain (blue, positive direction) or loss (red, negative direction) overlapping each gene, genome wide. Only mostly diploid samples without evidence of whole-genome doubling and with at least 50% of autosomes copy neutral are included. For the PCAWG data, all tumor types with at least 20 mostly diploid, TP53-mutated samples are included. Data sets included (top to bottom): TP53-mutated AML/MDS (n = 41), wild-type TP53 CBF AML (n = 18), and TP53-mutated lymphoid (B-NHL, n = 20; CLL, n = 6), esophageal (n = 24), hepatic (n = 56), ovarian (n = 23), pancreatic (n = 96), and prostate (n = 43) malignancies. B-NHL, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Of particular interest are TP53-mutated lymphoid malignancies (ie, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia), which lack the recurrent copy-number losses observed in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. These groups share only a high frequency of loss of the p-arm of chromosome 17, which encompasses the TP53 gene itself.

SV are frequent and often complex in TP53-mutated malignancies

In TP53-mutated AML/MDS samples, we observed a median of 71 somatic SVs per sample (range, 2-576 SVs; Figure 4A; supplemental Table 4). This represents a significantly higher burden than observed in the CBF AML samples (median, 6; range, 3-14 SVs; P = 5.6 × 10−8, 2-sided Wilcoxon ranked-sums test). In the TP53-mutated samples, the majority of SV represented highly complex rearrangements (Figure 4B). Of 3948 SV in TP53-mutated samples, 2673 (68%) were part of a complex SV involving ≥20 individual SV calls. In the 42 TP53-mutated samples, we detected ≥1 complex events comprising >20 SVs in 26 samples (62%), and ≥1 complex events comprising >100 SVs in 8 samples (19%). Genome wide, an analysis of SV breakpoints occurring in 100-kilobase windows showed clear enrichment of breakpoints only at the inv(16) and t(8;21) loci for CBF AML samples (Figure 4C). In contrast, breakpoints were identified throughout the genome in TP53-mutated AML/MDS cases, with enrichment on 17p (containing TP53) and on 21 (with 1 hotspot occurring just upstream from RUNX1).

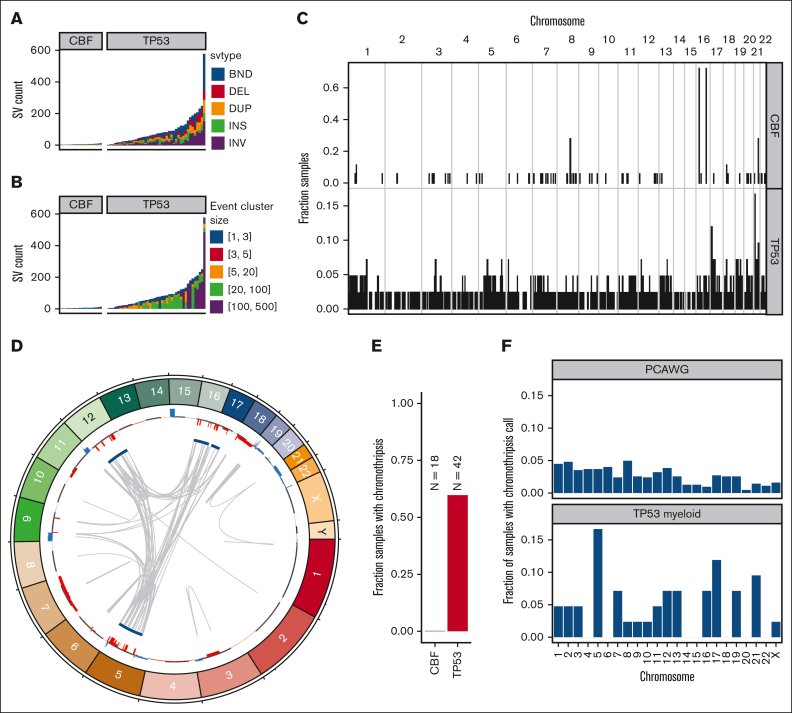

Figure 4.

SV and chromothripsis involve very large, complex events in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. (A) Somatic SV call counts for each case. Counts colored per SV classification: breakends (BND), deletion (DEL), duplication (DUP), insertion (INS), and inversion (INV). (B) Distribution of somatic SV cluster sizes for each case. Counts colored per the number of individual SV events occurring within the corresponding complex SV cluster. (C) Frequency of somatic SV breakpoints in 100-Kb windows genome wide. Bar height indicates the fraction of samples with at least 1 SV breakpoint within each window. (top) Fraction of CBF AML with somatic SV breakpoints in each window. (bottom) Fraction of TP53-mutant AML with somatic SV in each window. In CBF AML, enrichment of breakpoints is clearly present at inv(16) and t(8;21) positions. Breakpoints are present throughout the genome in TP53-mutated AML/MDS cases, with enrichment on chr17 and chr21. (D) Large regions of chr5, chr12, chr16, and chr17 are involved in complex rearrangements affecting copy number, including the TP53 genomic locus in a case of TP53-mutated AML (UPN 983349). (Outer track) copy gains (blue) and losses (red). (Inner track) regions involved in high-confidence chromothripsis events (dark blue). Gray arcs indicate novel adjacencies created by structural rearrangements. (E) Chromothripsis is detectable in 60% of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies and is not present in any CBF AML cases. (F) Genome-wide distribution of high-confidence chromothripsis calls. Proportion of all TP53-mutated PCAWG (top; n = 623) and AML/MDS (bottom; n = 42) samples with a chromothripsis call on each chromosome.

Chromothripsis is common in myeloid malignancies with a complex karyotype, with a reported frequency of 35% based on single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays.28 Chromothripsis arises from the attempted repair of extensive double-strand break fragmentation across regions of ≥1 chromosomes. The definition of chromothripsis includes the following: (1) clustering of breakpoints with large regions of interleaving normal sequence; (2) oscillations between 2 or 3 copy-number states; and (3) rearrangements of multiple fragments in random orientation and order.29 Using ShatterSeek to define high-confidence regions of chromothripsis,19 60% (25 of 42) of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies exhibited chromothripsis (Figure 4D; supplemental Table 5). In contrast, chromothripsis was not observed in any CBF AML samples. Of the 25 TP53-mutated AML/MDS samples with at least 1 high-confidence chromothripsis region, nearly half (48%; 12 of 25) had high-confidence regions detected on >1 chromosome (refer to Figure 4E for an example). In TP53-mutated AML/MDS, chromothripsis events occurred most frequently on chr5 (7 of 43 chromothripsis events), chr17 (5 of 43 chromothripsis events), and chr21 (4 of 43 chromothripsis events). This pattern is distinct from that observed across 603 TP53-mutated samples from the PCAWG consortium,19 in which 408 high-confidence chromothripsis regions were reported in 246 samples (38.2% of 19 different tumor types, but only 1 sample with myeloid malignancy; Figure 4F). We note that the 7 samples with chromothripsis within chr5 were a subset of the 33 samples with 5q loss, and do not represent biallelic loss of 5q. Three genomic regions were recurrently affected by chromothripsis in ≥4 of the TP53-mutated AML/MDS samples: an 87-Mb region of chr5q, in which the chromothripsis events involved large copy losses on 5q; a 6.2-Mb region on chr17q containing NF1, in which all 3 of 4 samples with chromothripsis exhibited a focal (<3 Mb) copy loss of NF1 and the fourth contained a disruptive SV breakpoint within the NF1 gene body; and a 12.8-Mb region on chr21q containing RUNX1, in which 3 of 4 samples with chromothripsis contained a disruptive SV breakpoint within the RUNX1 gene body.

Reduced expression of ETV6 is frequent in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies

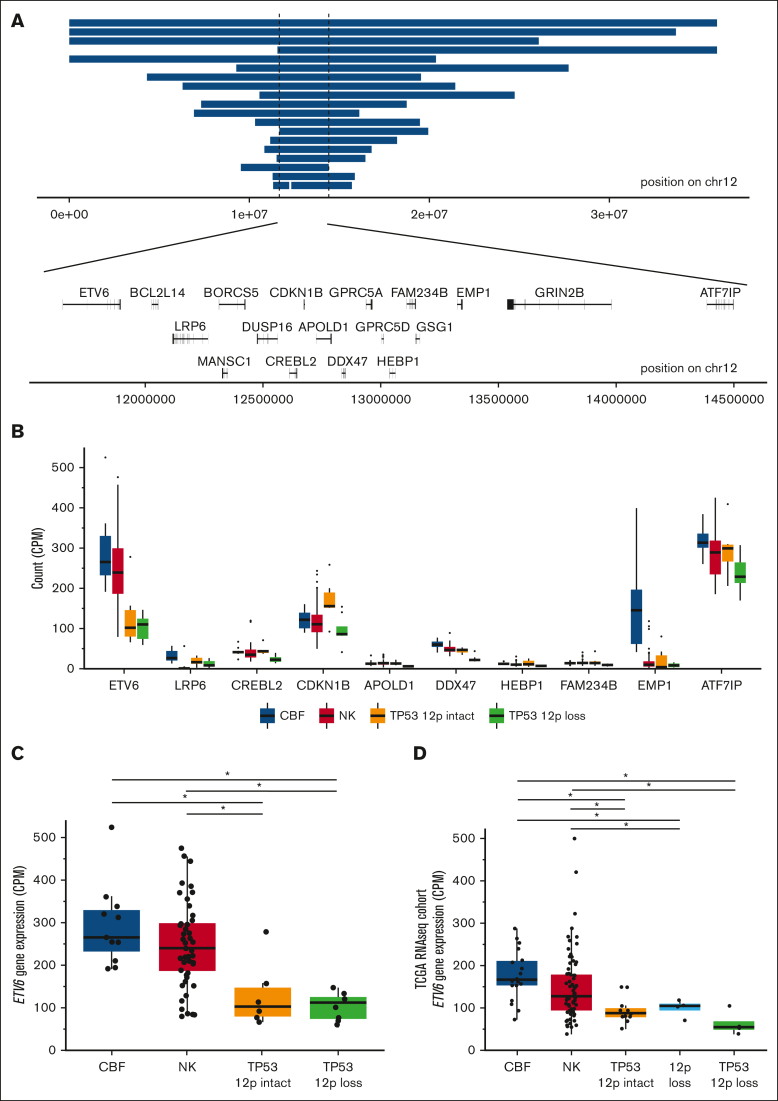

Copy-number losses on the p-arm of chromosome 12 occur frequently in TP53-mutated AML/MDS, affecting 45% (19 of 42) of samples in this cohort (supplemental Tables 6 and 7). The minimally deleted region of 12p spans 2.75 Mb, and includes the gene bodies of 18 protein-coding genes, including the tumor suppressors ETV6 and CDKN1B (Figure 5A). Both ETV6 and CDKN1B were also frequently deleted in TP53-mutated samples in the Beat AML cohort,26 with coordinate loss of each in 32% (6 of 19) of cases, compared with 1.7% (4 of 238) of non–TP53-mutated primary AML samples (odds ratio, 26; 95% confidence interval, 5.4-141.9; P = 1.3 × 10−5, 2-sided Fisher exact test, supplemental Table 8). We detected no somatic SNVs, indels, or fusions in either gene, nor in TP53-mutant cases from the Beat AML cohort.

Figure 5.

ETV6 deletion and decreased expression is common in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. (A) Genomic locations of copy-number losses intersecting the minimally deleted region on chr12p (n = 19). Locations of all protein encoding genes intersecting this region are shown. (B) mRNA expression for genes within the minimally deleted region of chr12p, displayed for genes with a minimum mean expression of 10 counts per million mapped reads for at least 1 group. Boxplot indicates median and first and third quartiles; whiskers indicate the range of all data points falling within 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR). CBF AML (n = 11); NK AML (n = 52); TP53-mutated with 12p intact (n = 6); and TP53-mutated with 12p loss (n = 8). (C) mRNA expression of ETV6 in TP53-mutated samples with and without 12p loss, compared with NK and CBF AML cases (n = 8, 6, 52, and 11, respectively). ∗Adjusted P value < .05, edgeR exactTestDoubleTail with adjustment for multiple comparisons. (D) Extension cohort of additional cases from the previously published The Cancer Genome Atlas Program AML data set. mRNA expression of ETV6 in TP53-mutated samples with 12p loss and with 12p intact (n = 4 and 11, respectively), NK (n = 79), CBF (n = 18), and 12p loss (TP53 wild type, n = 4) samples. ∗Adjusted P value < .05, t test with multiple testing correction.

RNA-sequencing data of genes in the minimally deleted region (Figure 5B) revealed that ETV6 was highly expressed in CBF and normal karyotype (NK) AMLs, and had significantly lower expression in TP53-mutated AMLs with 12p loss (adjusted P value = 1 × 10−4; Figure 5C; supplemental Table 9). In contrast, expression of CDKN1B in cases with a 12p deletion was similar to that observed in CBF or NK AMLs. Of note, a trend toward increased CDKN1B expression in 12p-intact TP53-mutant samples was observed, suggesting that its downregulation may not be an essential feature of TP53-mutant AML. The other gene with significantly decreased expression concordant with 12p deletion was DDX47 (adjusted P value = 4 × 10−8); however, this gene is not highly expressed in CBF and NK AMLs, and has no documented function in hematopoietic cells.

Surprisingly, decreased ETV6 expression was also observed in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies without 12p structural rearrangements (adjusted P value = .021; Figure 5C). This observation was confirmed in an extension cohort of messenger RNA (mRNA) data from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program22 (P values < .02 and .002 compared with CBF and NK AML cases, respectively; Figure 5D). No regulatory mutations in the ETV6 promoter or nearby enhancers were detected, nor was ETV6 promoter methylation altered in a cohort of 29 previously published samples with whole-genome bisulfite sequencing.23 Further studies will be needed to understand the genetic or epigenetic mechanisms governing ETV6 dysregulation in TP53-mutant myeloid malignancies.

Telomere content is increased in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies

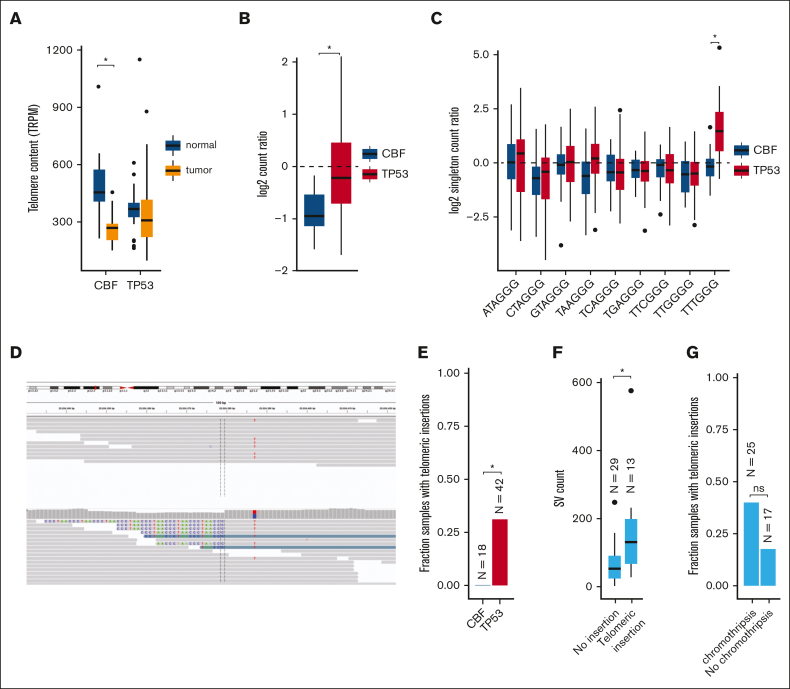

Excessive replication of leukemic blasts is expected to decrease telomere length in myeloid malignancies.30, 31, 32, 33 Indeed, reduced telomere content was detected in leukemic CBF AML bone marrow cells, compared with matched normal tissue obtained at the same time (mean shortening 226 telomeric reads per GC content–matched million reads; P = 8.3 × 10−7; Figure 6A; supplemental Table 10). Surprisingly, telomere content in TP53-mutated myeloid tumors was similar between leukemic and matched normal tissues. By normalizing tumor telomeric content to the paired normal for each sample (to account for age-related telomere shortening; supplemental Figure 3), we observed significantly less telomere shortening in TP53-mutant AML/MDS cases, compared with CBF AMLs (P = 1.7 × 10−5; Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Telomere content is increased in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. (A) Telomere content in units of telomeric reads per GC content–matched million reads (TRPM) was quantified in WGS from tumor specimens (orange) and paired germ line control tissues (skin or buccal DNA, blue) for CBF AML and TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. Significant telomere shortening in the CBF sample subset, with a mean shortening of 226 telomeric reads per GC content–matched million reads (TRPM; P = 8.3 × 10−7; 2-sided, paired t test) but not in the TP53-mutant subset (mean difference of −2.5 TRPM between tumor and normal). (B) Ratio of telomere content for tumor compared with normal tissue. TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies have significantly higher telomere content compared with CBF AML (P = 1.7 × 10−5, 2-sided t test). (C) Relative abundance of telomere variant repeats (TVR) in singleton context. Log2 tumor-to-normal ratio of singleton TVR repeats in TP53-mutant and CBF subtypes. The relative abundance of singleton TTTGGG repeats is significantly higher in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies compared with CBF AML (P = 1.4 × 10−7, 2-sided t test). (D) Example of intrachromosomal insertion of t-type telomeric hexamer sequences seen in the tumor but not the paired normal sequence data from a TP53-mutated case (UPN 387082). (E) Fractions of patients with TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies (n = 42) and CBF AML (n = 18) with detectable interstitial (nontelomere) telomeric repeat variants (P = .006, Fisher exact test). (F) TP53-mutated cases with detectable interstitial insertions of telomeric variant repeats have higher SV counts (P = .0033, Wilcoxon ranked-sums test). (G) Fraction of TP53-mutated cases with detectable interstitial insertions of telomeric variant repeats in sample with (n = 25) and without (n = 17) chromothripsis (P value, not significant; odds ratio, 3.03; 95% confidence interval, 0.61-20.7; Fisher exact test).

There are 2 candidate mechanisms by which telomere extension might occur. The first is a telomerase-dependent pathway, which has been associated with TTTGGG telomeric repeats.21 An analysis of telomere variant repeats in singleton context (ie, variant hexamers flanked by at least 3 t-type hexamers to each side) showed that telomeric repeats containing TTTGGG hexamers were significantly increased in TP53-mutated AML/MDS compared with the CBF subset (P = 1.4 × 10−7; Figure 6C). Telomerase-dependent telomere extension in solid tumors is frequently associated with extensive SV and copy-number amplifications affecting TERT expression.34 We observed copy-number events affecting the TERT locus on chr5p resulting in amplification in 2 samples, and a single TERT copy loss in 2 samples (supplemental Table 6). We did not observe any somatic SNVs, indels, or SVs affecting either the TERT gene body or promoter region. No significant difference in TERT mRNA expression was observed in TP53-mutated AML/MDS samples (supplemental Figure 4).

The second canonical mechanism of telomere extension is through the alternative lengthening of telomeres pathway, which has previously been associated with interstitial insertions of telomere sequences. Abnormal insertions of telomeric repeats adjacent to intrachromosomal regions (example shown in Figure 6D; supplemental Table 11) were detected in 13 (31%) TP53-mutated AML/MDS tumor samples but in none of the CBF tumor samples (P = .0061, Fisher exact test; Figure 6E). Of these 13 samples, 9 contained a single telomeric insertion; the remaining 4 contained ≥2 insertion sites. Within the subset of TP53-mutated samples, these telomeric insertions were associated with higher overall SV counts (P = .0033, Wilcoxon ranked-sums test, Figure 6F) and showed a trend toward the presence of chromothripsis that was not statistically significant (Figure 6G). The telomeric insertions tended to occur in close proximity to structural variations: 26% (5 of 19) occurred within 10 kb of a high-confidence chromothripsis region, and 68% (13 of 19) occurred within 10 kb of an SV breakpoint. ATRX or DAXX have been implicated in the alternative lengthening of telomeres pathway; notably, we did not observe any somatic SNVs, indels, or SVs affecting these genes. Similarly, ATRX and DAXX RNA expression did not significantly differ between the TP53-mutant and CBF or NK AMLs (supplemental Figure 4).

Discussion

The complex genomes of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies make genomic characterization of these cases difficult with traditional methods, including karyotyping, FISH, DNA microarrays, or targeted sequencing panels. To our knowledge, this study represents the largest WGS characterization of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies reported to date, and resolves the frequency, size, and complexity of acquired SV in these very disordered genomes. Novel observations using this approach include: (1) accurate determination of TP53 allele status by WGS reclassifies cases from monoallelic to multihit, which improves accuracy of IPSS-M risk prognosis for MDS; (2) aneuploidy in TP53-mutated AML/MDS differs remarkably from other cancers; (3) ETV6 is deleted in 45% of cases, with evidence for suppression in nondeleted cases; and (4) telomere content is higher in AML/MDS with TP53 mutations.

Multihit TP53 mutations are indicative of dismal prognosis in myeloid malignancies4,5 and are included in the International Consensus Classification3 and the World Health Organization1 classifications for MDS. We observed more frequent multihit involvement of TP53 (94%, with 92% of those unambiguously biallelic) compared with previous studies (76% of AML or MDS with excess blasts5; 63% of MDS4). This is likely because of a combination of cohort composition, with a higher number of complex karyotype cases,5 and better ascertainment provided by WGS. Current practices relying on cytogenetics and VAF thresholds for TP53 mutations miss multihit events in 12% of this cohort, and up to 25% of previously reported MDS cohorts,4,35 and may also underperform in peripheral blood samples or hemodilute bone marrow aspirates.

Chromosomal patterns of both aneuploidy and chromothripsis differed remarkably in TP53-mutated myeloid cancers vs lymphoid malignancies or solid tumors. Myeloid malignancies are known to involve losses of large regions on chromosomes 5 and 74 or chromothripsis,28 which we resolve to base-pair level breakpoints in many cases. Aneuploidy in TP53-mutated solid/lymphoid malignancies affects a substantially different pattern of chromosomes, but this has been previously unreported because of a paucity of myeloid malignancies in the PCAWG data set (1 case with TP53-mutated AML). Chromosomal alterations induced by TP53 mutations are specific to cell lineage, which previous models have suggested may arise because of sensitivity to disruptions, in particular transcription factors and signaling networks,36,37 or because of chromosome architecture and transcriptional activity.38

Although activating mutations in signaling proteins, such as NRAS and KRAS, are frequently observed in AML, they are relatively uncommon in TP53-mutated AML. In this cohort, we detected a strong enrichment of mutations in NF1, a negative regulator of Ras signaling. Previous studies identified NF1 mutations at frequencies of ∼5% for SNVs39 and 7% for SVs40 in all AMLs, and enrichment in complex karyotype AML of 9% for SNVs41 and 30% for SVs (with resolution to 0.1-2 Mb),42 although low NF1 RNA expression39 or high VAF41 suggested that these might be underestimates. Our observation of 45% of AML cases with NF1 mutations, with 17% of those being multihit, exceeds those estimates substantially and suggests strong cooperativity with TP53. The increased resolution of WGS identified 6 NF1 copy-number losses <3 Mb in size, not easily detectable with karyotyping. Additional studies will be needed to determine the mechanisms describing why NF1 mutations are preferentially selected for in a TP53-mutant context.

In this study, 45% of TP53-mutated AML/MDS samples had deletion of the p-arm of chromosome 12 with a minimally deleted region that included ETV6, consistent with other studies of complex karyotype AML,43 and far higher than non–complex karyotype AML or MDS (0.2%-3%).44 Gene expression data helped us nominate ETV6 as the most likely target gene in this region, although we cannot completely discount synergistic effects with other genes in the region, such as CDKN1B. This also led to the curious finding that ETV6 mRNA expression is decreased in TP53-mutated AML/MDS samples, even in those without 12p deletions, this suggests that downregulation of ETV6 gene expression, mediated either by genetic or epigenetic mechanisms, may be important for the pathogenesis of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies.

Our findings in CBF AMLs confirm previous studies in AML and MDS demonstrating shortened telomeres,30, 31, 32, 33 which play an essential role in genomic stability and shorten with each cell division.45 In contrast, we observed no significant decrease in the telomere content of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies, as was similarly reported in a recent conference abstract.46 We found support for both telomerase-dependent telomere extension, with an increase in TTTGGG telomeric repeats, and for ALT pathway telomere extension, with interstitial telomeric content. Furthermore, we may be underestimating interstitial telomeric content, because short-read WGS is not well suited to assess highly-repetitive telomere sequence.21 In solid tumors, these pathways are most often activated by high TERT expression or by ATRX or DAXX truncating mutations. However, for these cases, we observed only 2 with of TERT copy-number gains, which does not sufficiently explain this observation across the entire cohort. We conclude that TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies may use unique, as yet undefined mechanisms to induce telomere maintenance.

In summary, WGS of AML/MDS with paired normal tissue provides the most complete characterization to date of the genomic landscape of TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. These data emphasize the unique features of these cancers, including the high frequency of chromothripsis and SV, and the involvement of unique signaling genes, including NF1 and ETV6. Finally, we provide evidence that telomere maintenance is altered in TP53-mutated myeloid malignancies. These pathways may represent potential new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.F.D. has an equity ownership position in Magenta Therapeutics and WUGEN, and receives research funding from Amphivena Therapeutics, NeoImmune Tech, MacroGenics, Incyte, BiolineRx, and WUGEN. D.H.S. has received research funding from Illumina and consultant fees and stock options from WUGEN. E.J.D. is a consultant for Cofactor Genomics, Genescopy LLC, and Vertex, and has received honoraria from Blueprint Bio, AbbVie, and Illumina. Funding from these sources was not used for this study. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

Research support includes the Genomics of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Program Project grant, National Cancer Institute (NCI) P01 CA101937 (D.C.L and T.J.L.), Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Leukemia NCI P50 CA171963 (D.C.L.), NCI K12 CA167540 (K.A.O. and R.B.D.), NCI R50 CA211782 (C.A.M), and an American Society of Hematology award (K.A.O.). Core services were provided by the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center Tissue Procurement Core and Biostatistics Shared Resource Core through NCI Cancer Center grant P30CA091842, the Cytogenomics and Molecular Pathology Laboratory, Genome Technology Access Center, and the McDonnell Genome Institute at the Washington University School of Medicine.

Authorship

Contribution: H.J.A., K.A.O., C.A.M., D.C.L., T.J.L., M.J.W., and J.F.D. designed the study; S.E.H., P.W., R.B.D., S.P.T., and J.E.P. performed tissue repository sample identification and clinical annotations; R.S.F., C.C.F., N.M.H., D.H.S., E.J.D., and M.C.S. performed data acquisition; H.J.A., C.A.M., K.A.O., S.M.R., S.N.S., D.H.S., E.J.D., and M.C.S. performed data analysis; H.J.A., K.A.O., C.A.M., D.C.L., and T.J.L. wrote the manuscript draft; and all authors reviewed and contributed to the final manuscript.

Footnotes

∗H.J.A., K.A.O., and C.A.M. contributed equally to this study.

Data sets are available in dbGaP under study phs000159.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Khoury J, Solary E, Abla O, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1703–1719. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rücker FG, Schlenk RF, Bullinger L, et al. TP53 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype correlate with specific copy number alterations, monosomal karyotype, and dismal outcome. Blood. 2012;119(9):2114–2121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, et al. International Consensus classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022;140(11):1200–1228. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard E, Nannya Y, Hasserjian RP, et al. Implications of TP53 allelic state for genome stability, clinical presentation and outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1549–1556. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1008-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grob T, Al Hinai ASA, Sanders MA, et al. Molecular characterization of mutant TP53 acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2022;139(15):2347–2354. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberg OK, Siddon A, Madanat YF, et al. TP53 mutation defines a unique subgroup within complex karyotype de novo and therapy-related MDS/AML. Blood Adv. 2022;6(9):2847–2853. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncavage EJ, Schroeder MC, O’Laughlin M, et al. Genome sequencing as an alternative to cytogenetic analysis in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(10):924–935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Wang F, Kantarjian H, et al. Preleukaemic clonal haemopoiesis and risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):100–111. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30626-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillis NK, Ball M, Zhang Q, et al. Clonal haemopoiesis and therapy-related myeloid malignancies in elderly patients: a proof-of-concept, case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):112–121. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30627-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong TN, Ramsingh G, Young AL, et al. Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2015;518(7540):552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature13968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv. 2013 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997. Preprint posted online 16 March. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22(3):568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, Scheffler K, Halpern AL, et al. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat Methods. 2018;15(8):591–594. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Auwera GA, O’Connor BD. “O’Reilly Media, Inc.”; 2020. Genomics in the Cloud: Using Docker, GATK, and WDL in Terra. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron DL, Baber J, Shale C, et al. GRIDSS2: comprehensive characterisation of somatic structural variation using single breakend variants and structural variant phasing. Genome Biol. 2021;22(1):202. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02423-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Priestley P, Baber J, Lolkema MP, et al. Pan-cancer whole-genome analyses of metastatic solid tumours. Nature. 2019;575(7781):210–216. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1689-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shale C, Cameron DL, Baber J, et al. Unscrambling cancer genomes via integrated analysis of structural variation and copy number. Cell Genom. 2022;2(4):100112. doi: 10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cortés-Ciriano I, Lee JJ-K, Xi R, et al. Comprehensive analysis of chromothripsis in 2,658 human cancers using whole-genome sequencing. Nat Genet. 2020;52(3):331–341. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0576-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feuerbach L, Sieverling L, Deeg KI, et al. TelomereHunter - in silico estimation of telomere content and composition from cancer genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20(1):272. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-2851-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieverling L, Hong C, Koser SD, et al. Genomic footprints of activated telomere maintenance mechanisms in cancer. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):733. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Ley TJ, Miller C, Ding L, et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Upadhyay P, Beales J, Shah NM, et al. Recurrent transcriptional responses in AML and MDS patients treated with decitabine. Exp Hematol. 2022;111:50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2022.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell DW, Varley JM, Szydlo TE, et al. Heterozygous germ line hCHK2 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Science. 1999;286(5449):2528–2531. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernard E, Tuechler H, Greenberg Peter L, et al. Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System for myelodysplastic syndromes. NEJM Evidence. 2022;1(7) doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2018;562(7728):526–531. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0623-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ICGC/TCGA Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes Consortium Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature. 2020;578(7793):82–93. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rücker FG, Dolnik A, Blätte TJ, et al. Chromothripsis is linked to TP53 alteration, cell cycle impairment, and dismal outcome in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotype. Haematologica. 2018;103(1):e17–e20. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.180497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korbel JO, Campbell PJ. Criteria for inference of chromothripsis in cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;152(6):1226–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams J, Heppel NH, Britt-Compton B, et al. Telomere length is an independent prognostic marker in MDS but not in de novo AML. Br J Haematol. 2017;178(2):240–249. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park HS, Choi J, See CJ, et al. Dysregulation of telomere lengths and telomerase activity in myelodysplastic syndrome. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37(3):195–203. doi: 10.3343/alm.2017.37.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watts JM, Dumitriu B, Hilden P, et al. Telomere length and associations with somatic mutations and clinical outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2016;49:62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerbing RB, Alonzo TA, Sung L, et al. Shorter remission telomere length predicts delayed neutrophil recovery after acute myeloid leukemia therapy: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(31):3766–3772. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Chen F, Fonseca NA, et al. High-coverage whole-genome analysis of 1220 cancers reveals hundreds of genes deregulated by rearrangement-mediated cis-regulatory alterations. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):736. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13885-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshizato T, Nannya Y, Atsuta Y, et al. Genetic abnormalities in myelodysplasia and secondary acute myeloid leukemia: impact on outcome of stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2017;129(17):2347–2358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-12-754796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Short NJ, Montalban-Bravo G, Hwang H, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic impacts of mutant TP53 variant allelic frequency in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2020;4(22):5681–5689. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sack LM, Davoli T, Li MZ, et al. Profound tissue specificity in proliferation control underlies cancer drivers and aneuploidy patterns. Cell. 2018;173(2):499–514.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canela A, Maman Y, Jung S, et al. Genome organization drives chromosome fragility. Cell. 2017;170(3):507–521.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eisfeld A-K, Kohlschmidt J, Mrózek K, et al. NF1 mutations are recurrent in adult acute myeloid leukemia and confer poor outcome. Leukemia. 2018;32(12):2536–2545. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0147-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parkin B, Ouillette P, Wang Y, et al. NF1 inactivation in adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(16):4135–4147. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moison C, Lavallée V-P, Thiollier C, et al. Complex karyotype AML displays G2/M signature and hypersensitivity to PLK1 inhibition. Blood Adv. 2019;3(4):552–563. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018028480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rücker FG, Bullinger L, Schwaenen C, et al. Disclosure of candidate genes in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotypes using microarray-based molecular characterization. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3887–3894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feurstein S, Rücker FG, Bullinger L, et al. Haploinsufficiency of ETV6 and CDKN1B in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and complex karyotype. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):784. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q, Dong S, Yao H, et al. ETV6 mutation in a cohort of 970 patients with hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2014;99(10):e176–e178. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.104406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345(6274):458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wahida A, Hutter S, Gurnari C, et al. Mutant TP53 prevents telomere shortening in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):375. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.