Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a malignant brain tumor that grows quickly, spreads widely, and is resistant to treatment. Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)1 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that regulates cellular processes, including proliferation, survival, migration, and differentiation. FGFR1 was predominantly expressed in GBM tissues, and FGFR1 expression was negatively correlated with overall survival. We rationally designed a novel small molecule CYY292, which exhibited a strong affinity for the FGFR1 protein in GBM cell lines in vitro. CYY292 also exerted an effect on the conserved Ser777 residue of FGFR1. CYY292 dose-dependently inhibited cell proliferation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, stemness, invasion, and migration in vitro by specifically targeting the FGFR1/AKT/Snail pathways in GBM cells, and this effect was prevented by pharmacological inhibitors and critical gene knockdown. In vivo experiments revealed that CYY292 inhibited U87MG tumor growth more effectively than AZD4547. CYY292 also efficiently reduced GBM cell proliferation and increased survival in orthotopic GBM models. This study further elucidates the function of FGFR1 in the GBM and reveals the effect of CYY292, which targets FGFR1, on downstream signaling pathways directly reducing GBM cell growth, invasion, and metastasis and thus impairing the recruitment, activation, and function of immune cells.

Keywords: Blood-brain barrier, EMT, FGFR1, FGFR1 inhibitor, Glioblastoma

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most malignant type of glioma (grade IV), arises from astrocyte progenitor cells or stem cells. Among the most common brain tumors in humans, GBM has the highest fatality rate.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 GBM is one of the most aggressive forms of brain cancer, which is highly invasive and prevents surgical removal of all tumor cells, making recurrence inevitable. The great migratory capacity of GBM to infiltrate surrounding tissues is, at least in part, responsible for their invasion nature. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is thought to be one of the mechanisms that confer this invasive property to GBM cells.6 EMT is a biological process in which polarized epithelial cells are induced to undergo many biochemical changes, resulting in a mesenchymal phenotype with greater migratory capacity and resistance to genotoxic drugs.7 EMT is induced by the transitory activation of several oncogenic signaling pathways, triggering the reversible activation of transcription factors, such as Snail, Slug, Zeb1, and Twist.8 Factors that induce EMT in cancer may potentially induce EMT of glioma cells. Furthermore, EMT is an important inducer of the cancer stem cell (CSC) phenotype.9,10 GBM cells with a mesenchymal subtype frequently express neural stem cell markers and exhibit an aggressive character.10 In vitro and in clinical settings, glioma cells expressing stem cell markers are highly aggressive and resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.11,12 Therefore, it is urgent to find effective drug preparations and develop new therapeutic strategies to improve the prognosis of GBM cancer.

Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRS) belong to the tyrosine kinase receptor (TKR) family and regulate cell proliferation, survival, migration, and differentiation.13, 14, 15 Activation of the FGFR signaling pathway stimulates downstream signaling cascades, such as the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAP3K), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and phospholipase C γ (PLCγ) pathways, leading to tumor development and metastasis.16, 17, 18 FGFR1 gene is mutated or overexpressed in GBM and a wide spectrum of other solid tumors, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), melanoma, and breast, lung, prostate, bladder, and ovarian cancer. These tumorigenic FGFR1 aberrations constitutively activate FGFR1 and downstream contributing to tumor development.19, 20, 21 The Ser777 residue of FGFR1, which is located in the C-terminal tail, is a specific phosphorylation site targeted by ERK1 and ERK2. Ser777 phosphorylation lowers the activity of FGFR1 and its capacity to transmit mitotic signals, and FGFR1 Ser777 phosphorylation and cell migration may be strongly related to many types of cancer.22,23 In preclinical studies, FGFR inhibitors have been demonstrated to be quite effective and have shown great therapeutic value in preclinical models. AZD4547 and Infigratinib, two multikinase inhibitors that target FGFR and other kinases, have already excellent therapeutic promise in the clinical investigation of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and various other advanced solid tumors. However, the blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a critical barrier to the clinical efficacy of therapeutics to treat GBM,16,24,25 as tyrosine kinase inhibitors and other compounds cannot easily cross the BBB to exert their effects on GBM.26

In the present investigation, we identified CYY292 as a novel type of small molecule FGFR1 inhibitor. We describe how FGFR1 can be inhibited by CYY292 to prevent tumor invasion, metastasis, stemness, and proliferation. Additionally, we show that CYY292 can suppress brain cancer progression by crossing the BBB. Our research findings indicate that the FGFR1 protein is a druggable therapeutic target and that patients with locally advanced and metastatic cancer may benefit from the pharmacological effects of CYY292 on FGFR1.

Materials and methods

GBM cancer cell lines

The human GBM cancer cell lines U87MG, LN229, and U251, human embryonic kidney cell line human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T and mouse microglia cell line BV2 were purchased from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin‒streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Compound synthesis

On reasonable request, detailed information on the organic synthesis and chemical properties of the compound can be obtained. The compounds used in the study were dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain 10 mM stock solutions for in vitro studies. The FGFR inhibitor AZD4547 (cas no: 1035270-39-3, Shanghai, China) and PD173074 (cas no: 219,580-11-7, Shanghai, China) were purchased from Aladdin.

Cell viability and apoptosis assays

Cell proliferation was measured with a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were treated with vehicle or different concentrations of CYY292 for another 24 h. The cell growth was assessed by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a Molecular Devices microplate reader. The inhibition rate was calculated as follows [1 − (treatment/control)] × 100%. The logit technique was used to determine the IC50 value.

For apoptosis analysis, U87MG cells were treated with vehicle or various concentrations of CYY292 for 24 h, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by the FITC-conjugated Annexin V and PI staining (YEASEN, Shanghai, China) for 10 min according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell apoptosis was analyzed with FlowJo software.

Cell migration and invasion assays

For migration and invasion analysis, cells were inoculated in a serum-free medium (BD Bioscience) in the upper insert of a Transwell system. The lower insert, which was precoated with Matrigel (for cell migration analysis) or not (for cell invasion analysis), was filled with a complete culture medium. After the incubation period, the cells were fixed with methanol for 10 min, stained with 0.5% crystal violet, and counted under a microscope.

Western blotting and antibodies

Lysates were prepared from cells and tumor tissues for further use, and the protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting using anti-FGFR1 (Cell Signaling, #9740, 1:1000), anti-FGFR2 (Cell Signaling, #23328, 1:1000), anti-FGFR3 (Cell Signaling, #4574, 1:1000), anti-phosphorylated FGFR2 (Cell Signaling, #3476, 1:1000), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Cell Signaling, #3670, 1:200), anti-AKT (Cell Signaling, #4691, 1:2000), anti-phosphorylated AKT (Cell Signaling, #4060, 1:1000), anti-p44/42 MAPK (Cell Signaling, #4695, 1:3000), anti-phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK (Cell Signaling, #4370, 1:3000), anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, #97166, 1:5000), anti-Vimentin (Cell Signaling, #5741, 1:3000), anti-GSK3β (Cell Signaling, #5676, 1:2000), anti-phosphorylated GSK3β (Cell Signaling, #9322, 1:2000), anti-snail (Cell Signaling, #3879, 1:1000), anti-slug (Cell Signaling, # 9585.1:1000), anti-sox 2 (Cell Signaling, #3579, 1:1000), anti-Nanog (Cell Signaling, #4903.1:1000), anti-IκBɑ (Cell Signaling, #9242.1:2000), anti-phosphorylated IκBɑ (Cell Signaling, #5209.1:2000), anti-p65 (Cell Signaling, #8242, 1:500), anti-phosphorylated p65 (Cell Signaling, #13346,1:500), anti-p38 (Cell Signaling, #8690.1:1000), anti-phosphorylated p38 (Cell Signaling, #4511, 1:1000), anti-cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, #9661.1:200), anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling, #4970.1:5000), anti-phosphorylated FGFR1 (Abcam, ab173305, 1:1000), anti-phosphorylated FGFR3 (Abcam, ab155960,1:1000), anti-CD31 (Abcam, ab28364, 1:200), anti-F4/80 (Abcam, ab11101, 1:200), anti-phosphorylated serine (Abcam, ab9332, 1:1000), anti-ki67 (Abcam, ab15580, 1:300), anti-mouse (Abcam, ab6728,1:10,000), and anti-rabbit (Abcam, ab6721, 1:10,000).

Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

U87MG cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of CYY292 in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Control cells were incubated with an equal amount of DMSO. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS and then resuspended in cold PBS supplemented with a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. The cells were added to PCR strip tubes and heated in a thermocycler at the indicated temperature for 3 min. Then, the cells were lysed using two repeated freeze–thaw cycles (a pool of liquid nitrogen for uniform cooling and a block of metal heated to 25 °C for uniform heating). The supernatants were transferred to new tubes for Western blot analysis.

RNA preparation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated with a TRIzol kit (cat. no. 15596–026; Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using a Prime Script RT reagent kit (cat. no. RR047A; Takara, Shiga, Japan). qRT‒PCR was performed using qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme). The mRNA levels of the target genes were normalized to GAPDH levels. The primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Kinase activity analysis

In this experiment, we used the mobility shift assay method to assess the effects of various compounds on kinases. The compounds were applied at 5 concentrations (1000 nM stock solutions were diluted 10-fold). The compounds were added to single or multiple wells, and the assay was performed following the manufacturer's instructions (Sundia, Shanghai, China).

Molecular docking

The CDOCKER module of Discovery Studio 2016 was used for molecular docking in molecular modeling. CYY292 was mapped and converted to a 3D structure, and then locally minimized using the chemistry of the Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics (CHARMM) force field and X-ray crystals attached to FGFR1 (PDB code: 4V05). The binding site was determined by the initial ligand in the crystal structure and the protein-compound interaction was analyzed. Last, the image was created using PyMOL.

Colony formation assay

In 6-well plates, LN229 and U87MG cells (400–600 cells/well) were plated. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with different concentrations of CYY292 and then cultured for another 12 days. Finally, the cells were cleaned with phosphate buffered saline (PBS); colonies were fixed with methanol, stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution, and counted under a microscope.

Cloning, virus production, and infection

Full-length FGFR1 and truncated mutants were amplified by PCR and subcloned into the p3XFLAG-CMV vector. pLKO.1-FGFR1-shRNA1, pLKO.1-FGFR1-shRNA2, and Plko.1-FGFR1-shRNA3 were generated by GenScript Biotech Inc. (Hangzhou, China). HEK293T cells were transfected with the psPX2 and pMD2. G plasmids to obtain lentiviruses. The medium was replaced 24 h after transfection, and the conditioned medium containing virus particles was collected 48 h and 72 h after transfection. For virus infection, cells were treated with 10 μg/mL polybrene (Yeasen, China) mixed with virus-containing medium and culture medium at a ratio of 1:1 for 24 h. The cells were transfected again for 24 h, cultured in fresh medium for 24 h, and selected with puromycin-containing medium for 1 week. The sequences of the specific shRNAs used in this study are as follows: shFGFR1#1 (5′GATCCGGCTTCACTTAAGAATGTCTCTCAAGAGAGACATTTCTTAAGTGAAGCTTTTT3′), shFGFR1#2 (5′GATCCGCCGTCAATGTTTCAGATGATGCTATCAAGAGGAGCATCTGAAACATTGACGGTTTTT3′), and shFGFR1#3 (5′GATCCGGGCTTATTAATTCCGATACTATCAAGAGTAGTATCGGAATTAATAAGCCTTTTT3′).

Histological, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemical analyses

For histology, tumors and normal tissues were fixed with 4% PFA and embedded in paraffin. The embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μm, dewaxed, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For immunofluorescence analysis, cells and rehydrated tissue were grown on slides, fixed with 4% PFA, and incubated with antibodies. The images were acquired with a Leica-TCS SP8 microscope. For immunohistochemical analysis, defatted sections were incubated with citric acid-based antigen exposure solution for antigen retrieval. The sections were incubated in 0.3% H2O2 in PBS followed by a blocking buffer.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The compound was dissolved in a mixture of DMSO and physiological saline and injected into C57BL/6 mice via the tail vein at a dose of 30 mg/kg. The mice were sacrificed after anesthesia; their blood was collected from the retroorbital sinus; and their brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were collected (3 time points within 24 h, 3 mice per time point). The concentration of the compound was determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC‒MS/MS) (Worster, Germany).

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level measurement

ALT levels in the liver were measured with a kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Tumor xenograft and orthotopic xenograft models

All animal experiments complied with Wenzhou Medical University on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (wydw2021-0204). A total of 1 × 106 cells in a single-cell suspension were injected subcutaneously into the backs of 6- to 8-week-old male nude mice. The mice were randomly divided into three groups and maintained until their tumors reached a size of approximately 100 mm3. The tumor volume was calculated every day using the following formula: π × length × width2/6. At the end of treatment, the mice were euthanized (We allowed the animals to breathe diethyl ether and then utilized cervical dislocation to kill them in accordance with the applicable units' animal care and guidelines.), and tumors and organs were dissected, photographed, and weighed. In some experiments, 1 × 106 control shRNA-expressing cells and 2 × 106 FGFR1 shRNA-expressing cells were used to establish tumors of the same size. The tumor-related symptoms of tumor-bearing animals were regularly scored.

To further study the pharmacological properties of CYY292, we established an orthotopic xenograft nude mouse model. After the animals were deeply anesthetized (isoflurane), an incision was made in the scalp to expose the skull, and holes were drilled 0.5 mm anterior to and 1.0 mm lateral to the bregma. To establish the model, 2 × 105 cells were stereotactically injected into the right striata of the mice. On day 14 after injection, the tumor burdens of the mice were assessed using a GE Discovery 750 3.0 T MR scanner at the Zhejiang Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Hospital. The number of surviving nude mice was recorded, and survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan–Meier method.

Patient samples

In this study, 12 untreated patients with primary GBM were recruited from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Zhejiang, China; 2021-K-73-02). Tissue samples were retrieved from the Department of Pathology and sectioned. Subsequently, the tissue sections were fixed and subjected to immunohistochemical staining.

Clinical data analysis

Glioblastoma gene expression profiles and associated clinical data were downloaded from Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA)2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index). We further analyzed the relationship between gene expression and the progression of glioma ((http://www.cgga.org.cn).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in a blinded manner. Data from 3 independent experiments were presented as the mean ± SD. The number of groups/conditions (n) in each experiment is provided, and the data were presented as independent values rather than replicated. Differences were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney U test, unpaired two-sided Student's t-test, or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

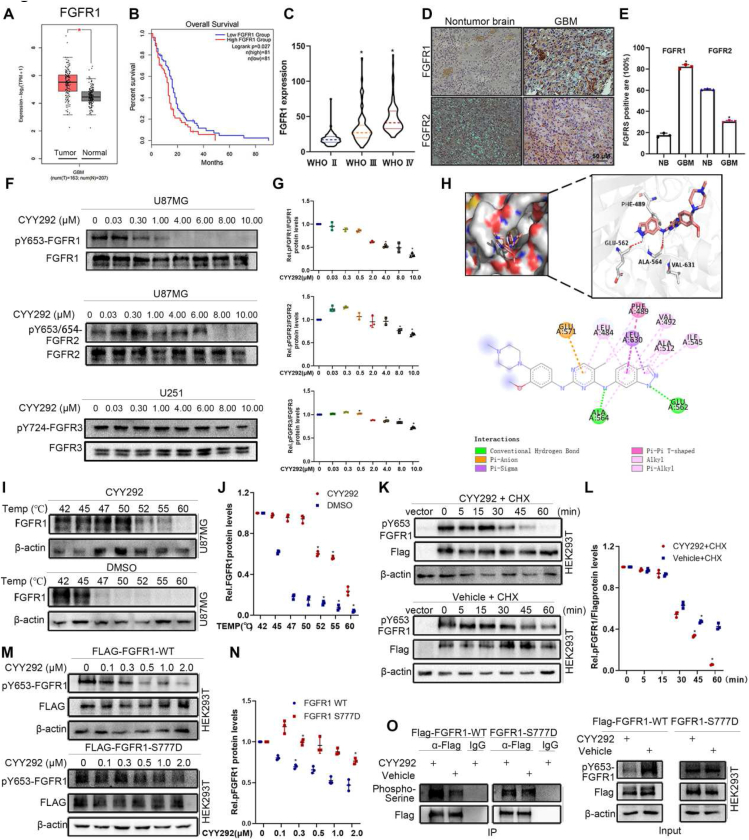

FGFR1 expression is negatively correlated with GBM prognosis

FGFR1 expression levels in tumors were significantly higher than those in normal tissues according to bioinformatics analysis of gene expression data from GEPIA (Fig. 1A). FGFR2 levels and FGFR3 levels exhibited the opposite change (Fig. S1A, B). There was no discernible difference in FGFR4 levels between the two groups (Fig. S1C). We also assessed which FGFR may be the most strongly associated with patient outcomes by analyzing a GBM dataset from TCGA using the Kaplan–Meier method. The analysis verified that FGFR1 levels were negatively correlated with the overall survival of patients (Fig. 1B). There was no significant correlation between FGFR2, FGFR3, or FGFR4 levels and patient survival (Fig. S1D–F). We then analyzed data from the Chinese Glioma Genome Alta (CGGA) database, and the results indicated that FGFR1 levels correlated with the progression of glioma (Fig. 1C). While FGFR3 and FGFR4 levels were not significantly correlated with glioma grade, FGFR2 levels decreased with increasing glioma grade (Fig. S1G–I). Our finding that FGFR1 is overexpressed in GBM was further supported by immunohistochemical staining of human glioma tissues (Fig. 1D). FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4 tested higher expression in non-tumor brain (NB) tissues than in GBM tissues (Fig. S1J). Collectively, these data imply that FGFR1 is frequently overexpressed in GBM and that FGFR1 expression is negatively correlated with overall survival.

Figure 1.

FGFR1 expression is negatively correlated with GBM prognosis. (A) Bioinformatic analysis of FGFR1 mRNA levels in the normal and GBM samples. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of TCGA GBM data. The data were collected from a public data set of stromal gene expression in GBM (GEPIA2). (C) FGFR1 expression is significantly up-regulated along with the WHO grade in the CGGA database. ∗P < 0.05. (D) Immunohistochemistry analysis of FGFR1 and FGFR2 expression in GBM and NB tissues. (E) Quantification of FGFR1 and FGFR2 in GBM and NB tissues. (F) Immunoblot analyses of the levels of phospho-FGFR1, phospho-FGFR2, and phospho-FGFR3 in the indicated cells treated with vehicle or various concentrations CYY292. (G) Densitometry of pFGFR1/FGFR1, pFGFR2/FGFR2, and pFGFR3/FGFR3 protein in cells as described in (F). (H) CYY292 was docked into the FGFR1 (4V05) using the docking program. The image shows the predicted binding pose. (I) Quantification was made using Western blot, U87MG cells were treated with CYY292 (4 μM) for 2 h, and temperatures between 42 °C–60 °C were defined to perform the test. (J) Densitometry of FGFR1/β-actin protein in cells as described in (I). (K) Immunoblot analysis of pFGFR1 expression in exogenous FGFR1 in HEK293T cells treated with vehicle or CYY292 and then with cycloheximide (CHX). (L) Densitometry of p-FGFR1/FLAG protein in cells as described in (K). (M) Exogenous FGFR1-WT and FGFR1 S777D of HEK293T cells were compared for endogenous p-FGFR1 expression. (N) Densitometry of pFGFR1/FLAG protein in cells as described in (M). (O) Comparison of phospho-Serine FGFR1-WT and FGFR1 S777D proteins in HEK293T cells treated with vehicle or 2 μM CYY292 for 12 h. MG132 (10 μM) was added 4 h before harvesting. IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA test.

CYY292 is a potent and selective inhibitor of FGFR1

Subsequently, we designed and optimized a series of compounds that inhibit FGFR1. Among them, compound CYY292 (C24H28N8O; MW, 444.24) had the strongest inhibitory effect on U87MG cell survival (Fig. S1L). The total synthesis of CYY292 is shown in Figure S2A. Acute toxicity tests showed that C57BL6 mice injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with a single dose of CYY292 up to 80 mg/kg showed no apparent adverse health effects over a 14-day observation period (Fig. S2B). An in vitro kinase activity assay revealed that CYY292 inhibited the tyrosine kinase activity of FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3 with IC50 values of 28, 28, and 78 nM, respectively (Fig. S1M) but had a weaker effect on FGFR4 kinase activity (IC50 > 1000). We next examined the degradation selectivity of CYY292. Immunoblot analysis indicated that CYY292 degrades phosphorylated FGFR1 with high selectivity without degrading phosphorylated FGFR2 or phosphorylated FGFR3 (Fig. 1F). CYY292 has excellent potency and remarkable selectivity for FGFR1, a member of the FGFR kinase family. Molecular docking experiments were carried out to more thoroughly assess the target interaction and binding mechanism of CYY292 to the FGFR1 protein [Protein Data Bank (PDB): 4V05] (Fig. 1H). Our computer simulations show that CYY292 forms hydrogen bonds with ALA564 and GLU562 (the dominant force). To further confirm the binding of the compound to FGFR1, we performed a CETSA to assess protein stability.27 Western blot analysis showed that FGFR1 was denatured at 47 °C in DMSO-treated control cells. However, following compound CYY292 treatment, the denaturation temperature increased to 58 °C (Fig. 1I, J). This finding indicates that compound CYY292 specifically stabilizes the FGFR1 protein in cells.

To directly investigate whether CYY292 impacts FGFR1 protein stability, we transfected exogenous FLAG-FGFR1 into HEK293T cells, treated them with cyclohexylamine (CHX; 100 μg/mL) to block the synthesis of new proteins and assessed phosphorylated FGFR1 degradation. After CHX treatment, phosphorylated FGFR1 showed reduced stability and was degraded quickly in CYY292-treated cells, while it was relatively stable in vehicle-treated cells, indicating that CYY292 reduced the stability of phosphorylated FGFR1 (Fig. 1K, L). Serine residues are prevalent in the C-terminal region of FGFR1; therefore, we believe that FGFR signaling may be regulated by the phosphorylation of certain serine residues.22 We compared the stability of phosphorylated FGFR1 in cells harboring the FGFR1-S777D mutant and WT FGFR1 after CYY292 treatment. CYY292 reduced phosphorylated FGFR1 protein levels in FGFR1-WT cells in a dose-dependent manner; however, 2 μM CYY292 had no effect on phosphorylated FGFR1 protein levels in FGFR1-S777D cells (Fig. 1M), confirming that Ser777 is a crucial amino acid residue for the binding of CYY292 to FGFR1. To determine whether this effect of CYY292 is caused by the phosphorylation of FGFR1, we subjected it to immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-FLAG beads. Notably, we observed that CYY292 increased the serine phosphorylation of FLAG-WT but had no effect on the serine phosphorylation of FLAG-S777D (Fig. 1O). These results imply that CYY292 alters FGFR1 phosphorylation both exogenously and endogenously, largely through the negative feedback effect of Ser777.

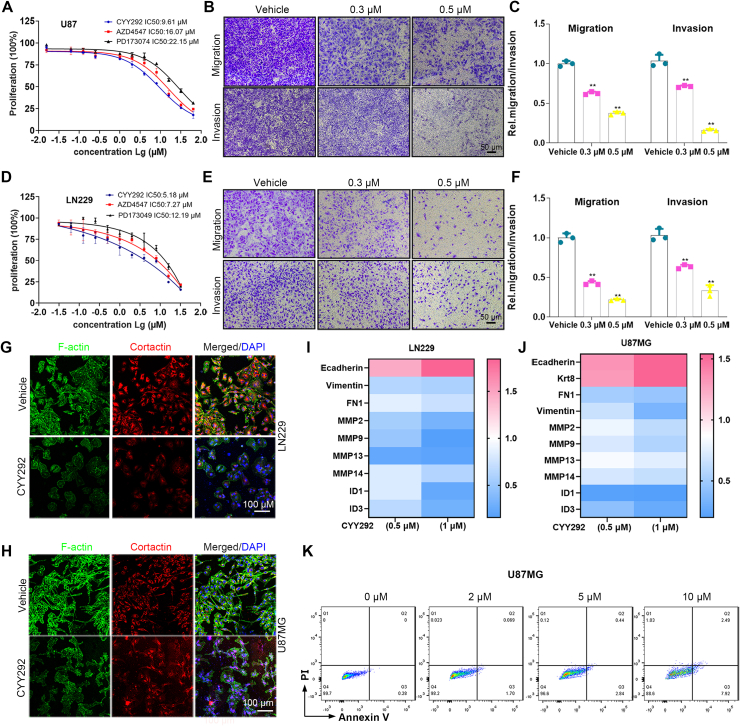

CYY292 reduces GBM cell migration and invasion and suppresses EMT

To evaluate the antitumor activity of CYY292, the inhibitory effect of CYY292 on the growth of U87MG, U251, and LN229 human GBM cells and BV2 mouse microglial cells was evaluated by the CCK-8 assay (Fig. S3A). We selected AZD4547 and PD173074, as the reference drugs. The activity of the three compounds against FGFR1 kinase is shown in Figure S3K. As shown in Figure 2A and D, we discovered that CYY292 had a stronger effect on suppressing cell proliferation than AZD4547 and PD173074. In contrast, in normal BV2 microglia, the effect of CYY292 was not different from that of AZD4547 or PD173074 (Fig. S3J). We first tried to determine whether CYY292 affects the migration and invasion of a variety of GBM cells. As shown in Figure 2B and E, CYY292 dose-dependently reduced the migration and invasion of all types of GBM cells in vitro (Fig. S3B). Wound-healing assays indicated a significant reduction in the wound closure area of CYY292 treatment cells at 24 h compared with negative control (NC) cells (Fig. S3D–I). CYY292 treatment for 24 h did not induce obvious apoptosis in U87MG cells but did decrease cell growth in a dose-dependent manner (by ∼62% at 10 μM) (Fig. 2K). F-actin is necessary for several crucial cellular processes, including cell contraction and motility, during cell division.28 We discovered that the levels of the cytoskeletal proteins F-actin and cortactin are altered by CYY292 (Fig. 2G, H), leading to the inhibition of cell migration and invasion. To assess the impact of CYY292 on GBM cell function, mRNA was isolated from vehicle- and CYY292-treated LN229 and U87MG cells. We discovered that the expression of epithelial markers (E-cadherin and keratin 18) was increased, while the expression of mesenchymal markers fibronectin (FN1) and vimentin was reduced. Notably, qRT-PCR analysis also showed that the expression of extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling genes (MMP2, MMP9, MMP13, and MMP14) and cell growth-stimulating genes (ID1 and ID3), which are related to invasion and metastasis was significantly decreased in CYY292-treated cells (Fig. 2I, J).

Figure 2.

CYY292 reduces GBM cell migration and invasion and suppresses EMT. (A, D) Effect of CYY292, AZD4547, and PD173074 on the viability of GBM cancer cells. Cells were challenged with increasing concentrations of CYY292 for 24 h and cell viability was measured by CCK8. IC50 values in U87MG and LN229 are shown. (B, E) Boyden chamber migration and invasion assays of U87MG (B) and LN229 (E) cells. Cells pretreated with CYY292 at different doses for 24 h were seeded in the upper insert in the presence (for invasion assay) or absence (for migration assay) of pre-coated Matrigel (n = 3). (C, F) Quantification of the migrated and invaded U87MG cells as shown in (B) and the migrated and invaded LN229 cells as shown in (E). (G, H) Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin and cortactin in vehicle- and CYY292-treated LN229 (G) and U87MG (H) cells. Nuclear, DAPI (blue). (I, J) qPCR analysis validated ECM remodeling genes (MMP2, MMP9, MMP13, MMP14), cell growth-stimulating genes (ID1 and ID3) as well as genes encoding EMT (E-cadherin, vimentin, FN1, Krt8). (K) Cell apoptosis analysis of U87MG cells that were treated with vehicle or different doses of CYY292 for 24 h (n = 3). Cells were co-stained with Annexin V and PI. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA test.

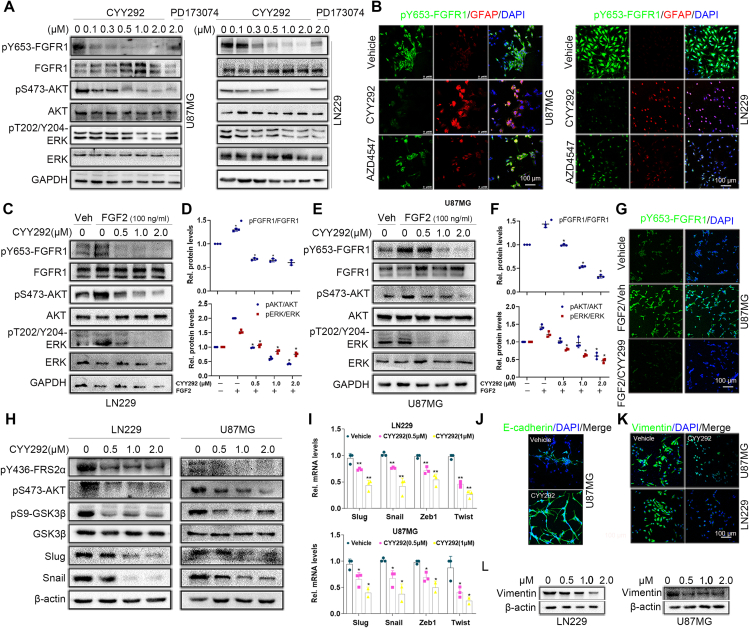

CYY292 specifically targets the FGFR1 signaling pathway in GBM cells

Because CYY292 specifically targets the FGFR1 receptors, we first tested whether the compound could directly affect FGFR signaling pathways in several kinds of GBM cells. Based on previous research (Fig. 1F), we administered three concentrations of CYY292, 0.5 μM, 1 μM, and 2 μM, to GBM cells to explore the underlying mechanism of the compound. We observed that phosphorylated FGFR1 (Tyr653) levels started to decrease in U87MG cells after treatment with 0.1 μM CYY292 (Fig. 3A). Additionally, CYY292 effectively inhibited downstream FGFR1 signaling in LN229 cells, as determined by assessing the phosphorylation of the scaffold proteins AKT (Ser473) and ERK (Thr202/Tyr204).29 No significant changes in FGFR1 mRNA levels were detected in CYY292-treated cells relative to control cells (Fig. S4A, B). CYY292 suppressed FGFR1 phosphorylation in a manner similar to that of PD173074, and the effect of CYY292 was dose- and time-dependent (Fig. S4C). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that phosphorylated FGFR1 expression was markedly decreased and GFAP expression was increased in CYY292-treated LN229 and U87MG cells compared to control cells (Fig. 3B). Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence showed that CYY292 dose-dependently reduced the FGF2-induced phosphorylation of several FGFR downstream proteins and inhibited downstream signaling pathways in LN229 and U87MG cells (Fig. 3C–G).

Figure 3.

CYY292 specifically targets the FGFR1 signaling pathway in GBM cells. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the indicated protein expressions in U87MG and LN229 cells treated with vehicle or CYY292, PD173074 for 2 h. Lysates were probed for FGFR1, p-FGFR1, AKT, p-AKT, ERK, p-ERK, and GAPDH served as controls. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of p-FGFR1 and GFAP in LN229 (right) and U87MG (left) cells. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). (C, E) Western blot analysis of p-FGFR1/FGFR1, p-AKT/AKT, and p-ERK/ERK in LN229 (C) and U87MG (E) cells exposed to CYY292 in a dose-dependent manner. FGF2 (100 ng/mL) was added 1 h before cell harvesting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D, F) Quantification of p-FGFR1/FGFR1, p-AKT/AKT, and p-ERK/ERK levels in LN229 (C) and U87MG (E). (G) Immunofluorescent staining of p-FGFR1 expressions in cancer cell lines that were treated with vehicle (Veh.) or FGF2 (100 ng/mL) for 2 h and then with vehicle or CYY292. (H) Western blot analysis using U87MG and LN229 lysates confirmed that phosphorylation of FGFR1, FRS2α, AKT, GSK3β, Snail, and Slug was effectively blocked by CYY292. Cells exposed to CYY292 at indicated concentrations for 24 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (I) CYY292 efficiently reduced Snail, Slug, Zeb1, and Twist levels in cells as indicated by representative qPCR analyses (n = 3). (J) Immunofluorescent staining of E-cadherin in the U87MG cells (n = 3). The indicated cells were pretreated with 1 μM for 24 h. (K) Immunofluorescent staining of vimentin in the U87MG and LN229 cells, respectively (n = 3). The indicated cells were pretreated with 1 μM for 24 h. (L) Western blot analysis of vimentin in U87MG and LN229 cells exposed to CYY292 at indicated concentrations for 24 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA test.

The PI3K-AKT pathway, a branch of the FGF signaling pathway,30 increases GSK3β activity by phosphorylating GSK3β at Ser9, increasing the stability and nuclear translocation of Snail and thereby promoting EMT.31,32 Therefore, we investigated whether CYY292 has an impact on the AKT/GSK3β/Snail pathway in LN229 and U87MG cells (Fig. 3H). As shown in Figure 3I, the mRNA levels of Slug, Snail, Zeb1, and Twist were decreased by approximately 60% relative to the basal level upon CYY292 treatment. After CYY292 treatment, the expression of the mesenchymal marker vimentin was decreased (Fig. 3K, L), and the expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin increased (Fig. 3J) in GBM cells.

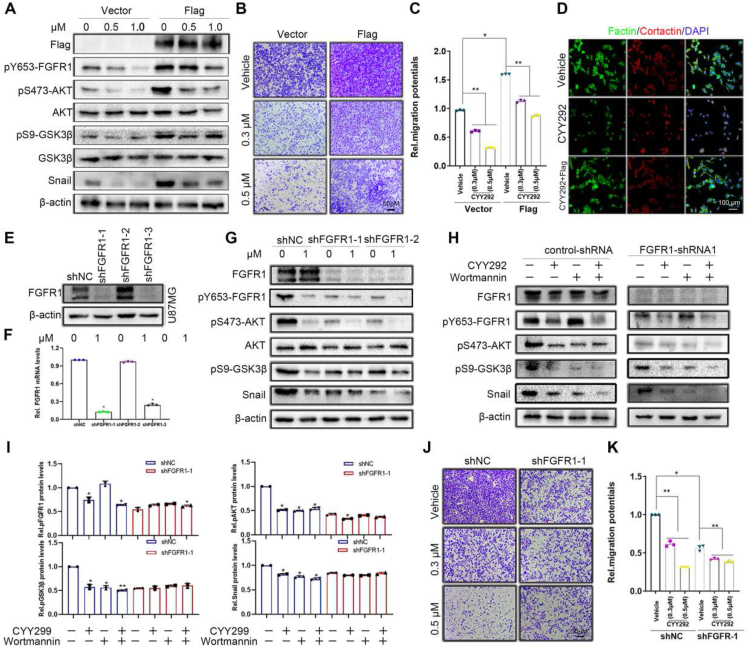

CYY292 blocks EMT by inactivating the Akt/GSK3β/Snail pathway

To prove our assumption, U87MG cells were infected with Flag-FGFR1. The phosphorylation of FGFR1, AKT, GSK3β, and Snail was increased in the FGFR1-overexpressing group compared with the control group, and CYY292 mitigated the changes in the expression of signaling proteins downstream of FGFR1 (Fig. 4A). To directly test whether FGFR1 is involved in the suppressive effect of CYY292 on cell invasion. Compared with control cells, FGFR1-overexpressing cells exhibited increased cell invasion and responded to CYY292 treatment (Fig. 4B, C). Furthermore, overexpression of FGFR1 in CYY292-treated GBM cells restored the morphology of U87MG cells (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

CYY292 blocks EMT by inactivating the Akt/GSK3β/Snail pathway. (A) FGFR1 stably (3 × FLAG-FGFR1) expressing cells are sufficient to increase the phosphorylation of FGFR1, AKT, GSK3β, and Snail. U87MG were infected with a plasmid expressing FGFR1 or a control. Cells were treated with dose-dependent CYY292 for 24 h. (B) Boyden chamber migration assays of U87MG cells stably expressing vehicle or Flag-FGFR1. (C) Quantification of invaded cells shown in (B). n = 3 independent experiments. (D) Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin and cortactin in vehicle-treated, CYY292-treated, or Flag-CYY292-treated U87MG cells. Nuclear, DAPI (blue). (E) U87MG cells were stably transfected with negative control shRNA or shRNA targeting FGFR1. (F) mRNA expression of FGFR1 in FGFR1-knockdown U87MG normalized to control cells (n = 3 independent experiments). (G) Comparison of p-FGFR1/FGFR1, p-AKT/AKT, p-GSK3β/GSK3β, and Snail expressions in control and FGFR1-deleted U87MG cells treated with vehicle or CYY292 for 24 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (H) Comparison of p-FGFR1, p-AKT, p-GSK3β, and Snail expressions in control (left) and FGFR1-deleted (right) U87MG cells treated with vehicle or CYY292 for 24 h. Cells were pre-treated with either wortmannin (0.1 μM) for 2 h. All representative blots and images as shown are from three independent experiments. (I) Quantification of p-FGFR1, p-AKT, and p-GSK3β levels in control (left) and FGFR1-deleted (right) U87MG cells. All data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). ∗P < 0.05. (J, K) Equal numbers of control and FGFR1-deleted U87MG cells pretreated with vehicle or CYY292 for 24 h were subjected to cell migration assays, and invaded cells were quantified (K). All data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, #P > 0.05. Differences are tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc test.

Then, we generated FGFR1 knockdown cells using shRNA to illustrate that FGFR1 is required for the effect of CYY292 (Fig. 4E). We found that CYY292 dose-dependently decreased phosphorylated FGFR1, AKT, GSK3β, and Snail levels in control and FGFR1-silenced U87MG cells (Fig. 4G). We investigated whether CYY292 regulates cell invasion and metastasis through the FGFR1/PI3K pathway. In control U87MG cells, phosphorylated AKT, GSK3β, and Snail levels were decreased by CYY292 and wortmannin (a PI3K inhibitor), but wortmannin was unable to alter phosphorylated FGFR1 levels. AKT/GSK3β-induced EMT was inhibited by CYY292 and wortmannin (Fig. 4H, I). It was found that CYY292 down-regulated the mRNA levels of Snail in control and FGFR1-silenced U87MG cells (Fig. S4E). FGFR1 was shown to be a negative regulator of EMT in GBM cells. FGFR1-silenced cells also showed reduced invasion compared with control cells and did not respond to CYY292 treatment (Fig. 4J). We also assessed the effect of FGFR1 knockdown on the proliferation ability of GBM cells in vitro. The proliferation of control and FGFR1-silenced cells was then measured in the presence of vehicles or various doses of CYY292. The inhibitory effect of CYY292 on cell growth was weaker in FGFR1 knockdown U87MG cells than in control cells (Fig. S4D). The data demonstrate that CYY292 inhibits AKT/GSK3β-induced EMT in response to FGFR1.

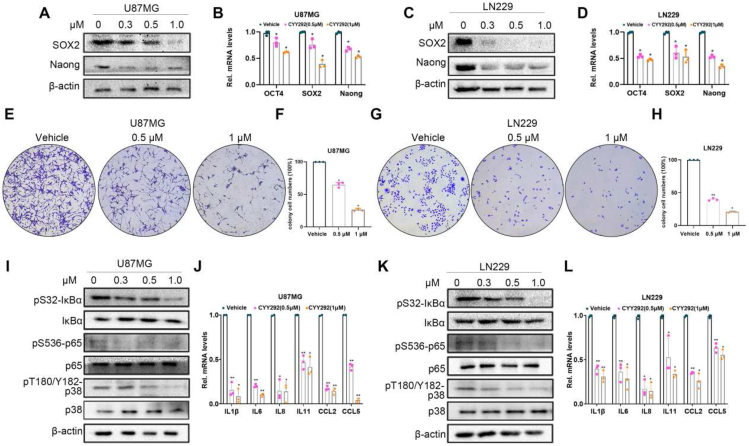

CYY292 suppresses the stemness function of GBM cells

Frequent tumor recurrence and subpar outcomes are known to result from the resistance of local GBM stem cells (GSCs) to currently available therapies.33 In addition, conventional treatments cannot eradicate CSCs, which exhibit increased invasiveness, metastasis, drug resistance, and immunological tolerance.10 Accordingly, we evaluated whether CYY292 influenced the stemness of GBM cells. We discovered that CYY292 markedly decreased the mRNA and protein expression of Nanog and Sox 2 in U87MG and LN229 cells (Fig. 5A–D). Besides, CYY292 also suppressed colony formation (that is, stemness) of U87MG and LN229 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5E–H). Cellular inflammation is prevented by the AKT signaling pathway. This signaling pathway can impact many downstream effectors, including p38MAPK, JNK1/2, and nuclear factor κ-B (NF-κB). Since activation of NF-κB and p38 signaling is closely associated with the generation of inflammatory factors,34, 35, 36 we used western blotting to analyze the phosphorylation of IκBɑ, p65, and p38 and found that CYY292 markedly reduced NF-κB and p38 activation (Fig. 5I, K). Oncogenes can trigger gene expression cascades, leading to the activation or overexpression of pro-inflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB, STAT3, and AP-1 and the production of cytokines and chemokines.36 We observed that CYY292 significantly decreased the mRNA expression of cytokines (IL1β, IL6, IL8, and IL11) and chemokines (CCl2 and CCl5) (Fig. 5J, L).

Figure 5.

CYY292 suppresses the stemness of GBM cells. (A, C) Immunoblot analyses of Nanog and Sox 2 levels in U87MG and LN229 cells treated with vehicle or CYY292 at 0.3, 0.5, and 1 μM for 24 h (n = 3). (B, D) qPCR analysis of Nanog, Sox2, and Oct 4 levels in cells treated as described in (A, C) (n = 3). (E, G) U87MG and LN229 cells were seeded in six-well plates and treated with 0.5 or 1 μM CYY292 or vehicle for colony formation assay. (F, H) Quantification of the U87MG cells and LN229 as shown in (E, G). (I, K) Immunoblot analyses of pIκBα/IκBα, p-p65/p65, and p-p38/p38 levels in U87MG and LN229 cells treated with vehicle or CYY292 at 0.3, 0.5, and 1 μM for 24 h. β-Actin was used as a protein-loading protein. (J, L) qPCR analysis of the levels of chemokine cytokines (IL1β, IL6, IL8, IL11) and chemokines (CCl2, CCl5) in cells treated as described in (A, C) (n = 3). All data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, #P > 0.05. Differences are tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc test.

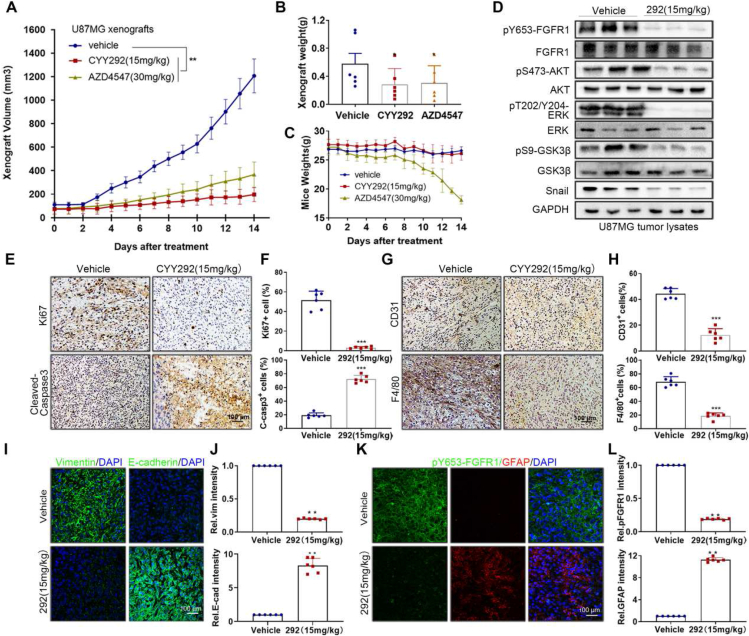

CYY292 inhibits U87MG xenograft tumor growth in vivo

Next, we investigated whether CYY292 has a similar effect on GBM cell growth in U87MG xenografts. For animal experiments, we did a preliminary experiment in advance, and finally chose 15 mg/kg (CYY292) and 30 mg/kg (AZD4547) for research. We discovered that CYY292 (15 mg/kg) (once a day) inhibited tumor growth by 83.7% and that AZD4547 (30 mg/kg) (once a day) inhibited tumor growth by 69.3%. Additionally, AZD4547 (30 mg/kg) caused nude mice to lose weight (Fig. 6A–C) and the physical condition of the nude mice deteriorated during the therapy. Furthermore, we found that CYY292 could reduce the expression of signaling pathway proteins mediated by FGFR1 (Fig. 6D, K). Afterward, we observed that CYY292 substantially reduced the percentage of proliferative (Ki67-positive) cells while increasing the percentage of apoptotic (cleaved caspase 3-positive) cells (Fig. 6E, F). It is well known that GSCs promote the recruitment of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which facilitate tumor progression. We discovered that CYY292 decreased the intratumoral infiltration of CD31+ endothelial cells and F4/80+ TAMs (Fig. 6G, H). Vimentin expression in the tumors of CYY292-treated mice consistently decreased, while E-cadherin expression in the tumors of CYY292-treated mice increased, indicating that CYY292 suppresses FGFR1-induced EMT in vivo (Fig. 6I). At later time points, we administered CYY292 (30 mg/kg) to nude mice, and the inhibition of tumor growth increased to 87.9% (Fig. S5A–C). We examined ALT levels in the liver to determine whether CYY292 is toxic to the liver; however, there was no discernible difference in ALT levels between the administration group and the control group (Fig. S5D). Notably, CYY292 did not alter body weight or induce detectable histological alterations in vital organs, such as the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, indicating that CYY292 is not toxic to mice (Fig. S5E).

Figure 6.

CYY292 inhibits U87MG xenograft tumor growth in vivo. (A–C) U87-MG xenograft tumor volumes (A), tumor weights (B), and mouse weights (C) were measured in athymic nude mice treated intraperitoneally with vehicle, CYY292 (15 mg/kg) or AZD4547 (30 mg/kg) for two consecutive weeks (n = 6 mice, each). The tumors were harvested at 14 days of follow-up. (D) Immunoblot analysis of p-FGFR1/FGFR1, p-AKT/AKT, p-GSK3β/GSK3β and Snail expressions in tumor lysates of vehicle- and CYY292-treated mice (n = 3 pools from six mice, each). GAPDH was used as a protein-loading protein. (E, G) Immunohistochemical staining of Ki67, cleaved-caspase 3, CD31 and F4/80 in xenograft tumors of vehicle- and CYY292-treated mice (n = 6 mice, each). (F, H) Quantification of Ki67-positive, cleaved-caspase3-positive, CD31-positive, and F4/80-positive cells in tumors as described in (E, G). (I, K) Immunofluorescence staining of E-cadherin, vimentin (I), p-FGFR1, and GFAP (K) in xenograft tumors of vehicle- and CYY292-treated mice. (J, L) Quantification of staining in primary tumors as described in (I, K). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Differences are tested using the Mann–Whitney U test.

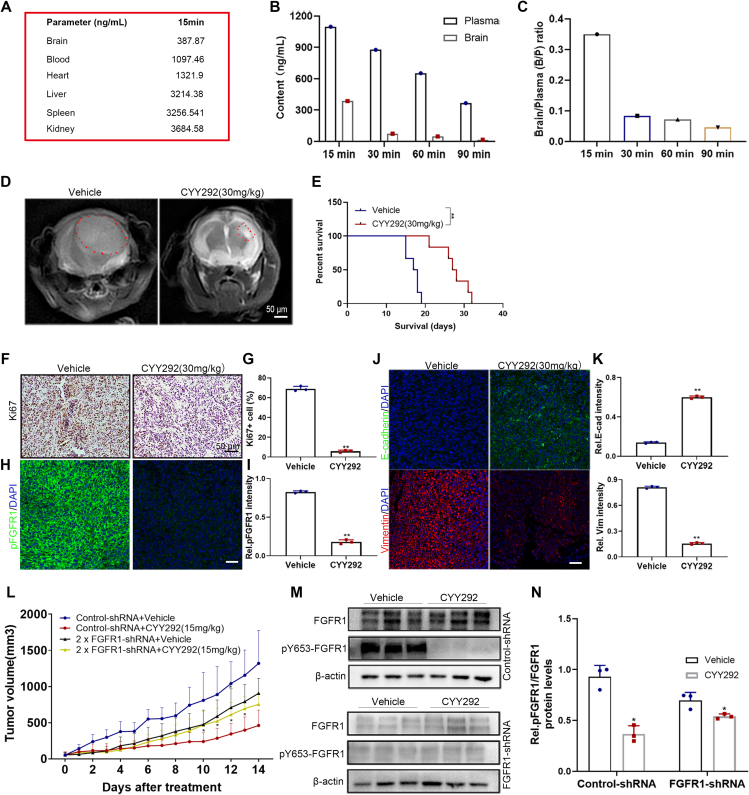

CYY292 suppresses FGFR1-mediated U87MG GBM cell growth and orthotopic GBM models

One of the fundamental reasons why GBM is difficult to treat is that compounds cannot easily cross the BBB. To determine if CYY292 crosses the BBB, we employed HPLC. We injected CYY292 (30 mg/kg) into BALB/c mice through the abdominal cavity, collected tissues and organs, and assessed the content and distribution of the compound in the tissues and organs (Fig. 7A). The brain/plasma ratio of CYY292 decreased with time. The content of CYY292 was within acceptable limits, and the results did not indicate that the compound accumulates in tissues (Fig. 7B, C). Additionally, the anticancer effect of CYY292 was tested in an orthotopic U87MG xenograft model. MRI on the 14th day showed that the volume of tumors generated by cells treated with compound CYY292 (once a day) was lower than that of tumors generated by control cells (Fig. 7D). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated that CYY292 increased the survival time following tumor cell implantation (Fig. 7E). Histological data show that ki67 (Fig. 7F) was reduced after CYY292 treatment, which indicated that CYY292 inhibited tumor growth. Consistently, tumors of CYY292-treated mice showed a decrease in phosphorylated FGFR1 expression (Fig. 7H). As expected, tumors of CYY292-treated mice exhibited remarkably reduced vimentin expression in tandem with increased E-cadherin protein levels, as assessed by immunofluorescence analyses (Fig. 7J).

Figure 7.

CYY292 suppresses FGFR1-mediated U87MG GBM cell growth and orthotopic GBM models. (A) In the screening BBB penetration assay, mice were dosed at 30 mg/kg and tissue (brain, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and blood) content are measured for 15 min. (B, C) In the screening BBB penetration assay, mice were dosed intravenously at 30 mg/kg and brain and plasma levels are measured at four time points. The ratio of brain to plasma (B/P) was determined over time (C). (D) Coronal-T2-weighted MRI of tumors generated by control- and CYY292-treated cells (n = 6 mice, each). (E) The survival of mice with orthotopic tumors was measured by Kaplan–Meier survival curves. ∗∗P < 0.01. (F) Immunohistochemical staining of Ki67 orthotopic tumors of vehicle- and CYY292-treated mice (n = 3 mice, each). (H, J) Immunofluorescence staining of p-FGFR1 (H), E-cadherin, and vimentin (J) in orthotopic tumors of vehicle- and CYY292-treated mice. (G, I, K) Quantification of staining in primary tumors as described in (F) and (H, J). (L) Growth of U87MG xenograft tumors derived from 1 × 106 control cells or 2 × 106FGFR1-silenced cells were monitored in nude mice treated with vehicle or CYY292 for two consecutive weeks (n = 6 mice, each). (∗P < 0.05, #P > 0.05, two-sided Student's t-test). (M) Immunoblot analysis of p-FGFR1 and FGFR1 expressions in lysates of xenograft tumors as described in (L). (N) Quantification of staining in primary tumors as described in (M). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

To further investigate whether the in vivo anticancer effect of CYY292 is dependent on FGFR1, we implanted vehicle-treated U87MG cells or FGFR1-silenced U87MG cells subcutaneously into nude mice. The injected nude mice received treatment for two consecutive weeks, and tumor growth was monitored. It is worth noting that CYY292 inhibited the growth of tumors formed by control cells but failed to affect the growth of tumors formed by FGFR1-silenced cells to a large extent (Fig. 7L), indicating that CYY292 inhibited tumor growth by specifically targeting the FGFR1 protein. As expected, CYY292 decreased phosphorylated FGFR1 levels in control cells but was unable to decrease phosphorylated FGFR1 levels in FGFR1-silenced cells (Fig. 7M, N). These in vivo results provide evidence that CYY292 can penetrate the BBB and reduce FGFR1-driven tumor growth.

Discussion

FGFR1 is a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays an important role in the occurrence and development of GBM, including proliferation, survival, migration, and differentiation. FGFR1 overexpression is linked to increased cancer cell invasion and proliferation according to a preclinical investigation.37, 38, 39 In the current study, inhibition of FGFR1 was found to be a crucial strategy for increasing the sensitivity of GBM to radiation, as FGFR1 is an oncogene that is expressed at a higher level in malignant tissues than in normal tissues.18,40 In this work, immunohistochemistry revealed that FGFR1 was expressed at a high level in GBM, and we discovered that FGFR1 expression increased with GBM grade and was negatively correlated with GBM patient survival.

Given the significance of FGFR1 in GBM, we designed the inhibitor CYY292, and the findings of in vitro kinase assays revealed that CYY292 effectively suppressed FGFR1 kinase activity (Fig. S1K). There are seven phosphorylation sites on FGFR1 (Tyr463, Tyr583, Tyr585, Tyr653, Tyr654, Tyr730, and Tyr766), of which Tyr653 and Tyr654 are crucial for triggering the tyrosine kinase activity of FGFR1 and are necessary for FGFR1-mediated biological responses.41 Our results indicate that CYY292 down-regulates the phosphorylation of Y653 of FGFR1, which mediates the phosphorylation of the two main downstream proteins, AKT and ERK. The degree of tyrosine phosphorylation within the receptor kinase domain is controlled by direct serine phosphorylation of FGFR1, which influences downstream signaling events and biological activities. The phosphorylation status of the Ser777 residue of FGFR1 influences receptor tyrosine phosphorylation (and activation) as well as downstream signaling.22,42 CYY292 enhances the phosphorylation of Ser777 and regulates FGFR1 activity through a negative feedback mechanism. To ensure the transmission of precise signals, more research is required to determine if other negative feedback mechanisms can also regulate FGFR1 activity.

We, therefore, propose that targeting FGFR1 might be a promising therapeutic approach for GBM. However, to our knowledge, the failure of tyrosine kinase-based therapies in treating GBM is related to the inability of tyrosine kinase inhibitors to cross the BBB. In the current investigation, we developed a novel small-molecule inhibitor, CYY292, which reached the brain and exhibited a reduction in brain/blood ratio over time (Fig. 7B, C). In an orthotopic mouse model, CYY292 reduced the size of xenograft tumors and improved the survival rate (Fig. 7D, E). CYY292 exhibits higher anti-proliferative activity than AZD4547 and PD173074 in U87MG, LN229, and U251 cells. The data above demonstrated that CYY292 had a greater effect than AZD4547 at the same dosage (Fig. 6A; Fig. S5A). The toxic and side effects of CYY292 on mice were much lower than those of AZD4547. Notably, we have demonstrated that, in tumor-bearing animals, CYY292 effectively inhibits FGFR1-driven cancer development and metastasis without eliciting obvious side toxicity (Fig. S2B, C). This can be attributed to the high selectivity of the compound for targeting FGFR1 protein and the spatial expression pattern of FGFR1 in malignant tissues as opposed to normal tissues. Based on the kinase detection results, we also acknowledged that the CYY292 may also target KDR, C-KIT, FLT1, and IGF1R. As such, further studies with alternative targets are warranted.

In this study, CYY292, a highly selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor of FGFR1, suppressed the growth, migration, and invasion of GBM cells. It is hypothesized that tumor growth is facilitated by EMT-induced cellular alterations that cause cancer cells to adopt a mesenchymal-like character. Many studies have revealed the essential function of E-cadherin deletion in EMT, and loss of E-cadherin expression has been observed during tumor development in most epithelial and epithelioid malignancies. Snail, also known as E-cadherin, is a direct inhibitory factor. The conserved C-terminal zinc finger structure of snail can bind to the E-box at the proximal end of the E-cadherin promoter of the downstream target gene to inhibit its transcription.8 We discovered that CYY292 suppressed Snail expression while simultaneously inducing E-cadherin expression (Fig. 3H, J). The induction of invasion and EMT has been linked to the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway.30 The phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 by AKT causes GSK3β activity to be reduced. GSK3β binds to and phosphorylates the Snail transcription repressor, causing Snail mRNA to translocate to the cytoplasm and be degraded.32 Our results showed that CYY292 suppressed Snail expression by controlling PI3K-AKT signaling and modulating cell shape, motility, proliferation, and differentiation. EMT is known to cause cancer cells to adopt stem cell properties by increasing the expression of stem cell markers, improving treatment chemoresistance, and boosting tumor-initiating activity (i.e., stemness). FGFR1 is the only member of the FGFR family that has been demonstrated to be functionally related to tumor cell sphere formation (a sign of stem cell viability). Higher survival following FGFR1 deletion, as well as increased tumorigenicity of FGFR1+ cells, highlight the important effect of FGFR1 on GSCs.12 We propose that CYY292 inhibits the stemness of GBM cells not only by directly targeting the CSC transcription factors Nanog and Sox 2 but also by suppressing NF-κB and p38 signaling. Here, we demonstrated the anti-proliferative, anti-invasive, and metastatic effects of FGFR1 inhibitors CYY292 in GBM cells and mouse models, revealing a potential multifaceted role for FGFR1 in the treatment of GBM.

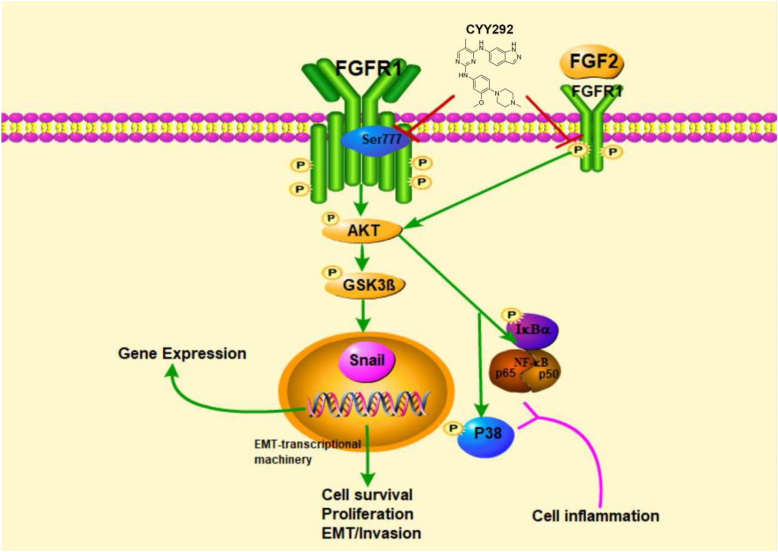

The effect of CYY292, which targets FGFR1, on downstream signaling pathways may directly reduce GBM growth, invasion, and metastasis and thus impair the recruitment, activation, and function of immune cells in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 8). We think more research is necessary to fully understand the therapeutic potential of CYY292 in the treatment of GBM cancer.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the effect of CYY292 on the FGFR1 signaling pathways.

Ethics declaration

All experiments met ethical review and were approved by Wenzhou Medical University on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (wydw2021-0204). Second Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Zhejiang, China; 2021-K-73-02).

Author contributions

Yan ran Bi: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing, and original draft. Jiahao Hu: operation. Ruiling Zheng, Ruiqing Sh, Junfeng Shi, Yutao Wang, and Wenyi Jiang: investigation. Peng Wang and Gyudong Kim: supervision. Xiaokun Li, Li Lin, and Zhiguo Liu: project administration, resources, supervision, and funding acquisition.

Conflict of interests

All authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81971180, 81973168 and 82003793), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (No. 2019–12M-5-028), the Scientific Research Project of Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China (No. ZY2019001), and the National Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (No. LZ22H300002).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2023.02.035.

Contributor Information

Gyudong Kim, Email: Gdkim0217@chonnam.ac.kr.

Zhiguo Liu, Email: Liucnu@163.com.

Xiaokun Li, Email: xiaokunli@wmu.edu.cn.

Li Lin, Email: linliwz@163.com.

Abbreviations

- BBB

Blood–brain barrier

- B/P

brain and plasma

- CSC

Cancer stem cell

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EMT

Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR1

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- GSC

GBM cancer stem cell

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- TAM

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TF

Transfer factor

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Davis M.E. Glioblastoma: overview of disease and treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20(5 Suppl):S2–S8. doi: 10.1188/16.CJON.S1.2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ou A., Alfred Yung W.K.A., Majd N. Molecular mechanisms of treatment resistance in glioblastoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):351. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juratli T.A., Qin N., Cahill D.P., et al. Molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic implications in pediatric high-grade gliomas. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;182:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldape K., Zadeh G., Mansouri S., et al. Glioblastoma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129(6):829–848. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Festuccia C., Biordi A.L., Tombolini V., et al. Targeted molecular therapy in glioblastoma. J Oncol. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/5104876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iser I.C., Pereira M.B., Lenz G., et al. The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-like process in glioblastoma: an updated systematic review and in silico investigation. Med Res Rev. 2017;37(2):271–313. doi: 10.1002/med.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittal V. Epithelial mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;13:395–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H.M., Bi Y.R., Li Y., et al. A potent CBP/p300-Snail interaction inhibitor suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in wild-type p53-expressing cancer. Sci Adv. 2020;6(17) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw8500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao C., Huang K., Shi J., et al. Genomics and prognosis analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in glioma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:183. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwadate Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma progression. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(3):1615–1620. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L.H., Yin Y.H., Chen H.Z., et al. TRIM24 promotes stemness and invasiveness of glioblastoma cells via activating Sox 2 expression. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(12):1797–1808. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez-Pascual A., Hale J.S., Kordowski A., et al. ADAMDEC1 maintains a growth factor signaling loop in cancer stem cells. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(11):1574–1589. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marseglia G., Lodola A., Mor M., et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors: patent review (2015-2019) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2019;29(12):965–977. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1688300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner N., Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(2):116–129. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katoh M., Nakagama H. FGF receptors: cancer biology and therapeutics. Med Res Rev. 2014;34(2):280–300. doi: 10.1002/med.21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai S., Zhou Z., Chen Z., et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs): structures and small molecule inhibitors. Cells. 2019;8(6):E614. doi: 10.3390/cells8060614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimenez-Pascual A., Siebzehnrubl F.A. Fibroblast growth factor receptor functions in glioblastoma. Cells. 2019;8(7):715. doi: 10.3390/cells8070715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Touat M., Ileana E., Postel-Vinay S., et al. Targeting FGFR signaling in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(12):2684–2694. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koole K., Brunen D., van Kempen P.M., et al. FGFR1 is a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3884–3893. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gouazé-Andersson V., Ghérardi M.J., Lemarié A., et al. FGFR1/FOXM1 pathway: a key regulator of glioblastoma stem cells radioresistance and a prognosis biomarker. Oncotarget. 2018;9(60):31637–31649. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pennisi D.J., Mikawa T. FGFR-1 is required by epicardium-derived cells for myocardial invasion and correct coronary vascular lineage differentiation. Dev Biol. 2009;328(1):148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zakrzewska M., Haugsten E.M., Nadratowska-Wesolowska B., et al. ERK-mediated phosphorylation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 on Ser777 inhibits signaling. Sci Signal. 2013;6(262):ra11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obenauer J.C., Cantley L.C., Yaffe M.B. Scansite 2.0:Proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3635–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallinan N., Finn S., Cuffe S., et al. Targeting the fibroblast growth factor receptor family in cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;46:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver A., Bossaer J.B. Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors: a review of a novel therapeutic class. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2021;27(3):702–710. doi: 10.1177/1078155220983425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodfellow V.S., Loweth C.J., Ravula S.B., et al. Discovery, synthesis, and characterization of an orally bioavailable, brain penetrant inhibitor of mixed lineage kinase 3. J Med Chem. 2013;56(20):8032–8048. doi: 10.1021/jm401094t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jafari R., Almqvist H., Axelsson H., et al. The cellular thermal shift assay for evaluating drug target interactions in cells. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(9):2100–2122. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di L., Liu L.J., Yan Y.M., et al. Discovery of a natural small-molecule compound that suppresses tumor EMT, stemness and metastasis by inhibiting TGFβ/BMP signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:134. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1130-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babina I.S., Turner N.C. Advances and challenges in targeting FGFR signalling in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(5):318–332. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akinleye A., Avvaru P., Furqan M., et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors as cancer therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:88. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng Q., Shi S., Liang C., et al. Abrogation of glutathione peroxidase-1 drives EMT and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by activating ROS-mediated Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling. Oncogene. 2018;37(44):5843–5857. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0392-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou B.P., Deng J., Xia W., et al. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3 beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(10):931–940. doi: 10.1038/ncb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bao S., Wu Q., McLendon R.E., et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C., Zeng L., Zhang T., et al. Tenuigenin prevents IL-1β-induced inflammation in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes by suppressing PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. Inflammation. 2016;39(2):807–812. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He S., Fu Y., Yan B., et al. Curcumol alleviates the inflammation of nucleus pulposus cells via the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway and delays intervertebral disk degeneration. World Neurosurg. 2021;155:e402–e411. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoesel B., Schmid J.A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Presta M., Chiodelli P., Giacomini A., et al. Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) in cancer: FGF traps as a new therapeutic approach. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;179:171–187. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grose R., Dickson C. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in tumorigenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giacomini A., Chiodelli P., Matarazzo S., et al. Blocking the FGF/FGFR system as a “two-compartment” antiangiogenic/antitumor approach in cancer therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2016;107:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng R., Chen Y., Wei L., et al. Resistance to FGFR1-targeted therapy leads to autophagy via TAK1/AMPK activation in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23(6):988–1002. doi: 10.1007/s10120-020-01088-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohammadi M., Dikic I., Sorokin A., et al. Identification of six novel autophosphorylation sites on fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and elucidation of their importance in receptor activation and signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(3):977–989. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sørensen V., Zhen Y., Zakrzewska M., et al. Phosphorylation of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 1 at Ser777 by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates translocation of exogenous FGF1 to the cytosol and nucleus. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(12):4129–4141. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02117-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.