Abstract

Wnt signaling plays a major role in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation. The Wnt ligands are a family of 19 secreted glycoproteins that mediate their signaling effects via binding to Frizzled receptors and LRP5/6 coreceptors and transducing the signal either through β-catenin in the canonical pathway or through a series of other proteins in the noncanonical pathway. Many of the individual components of both canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling have additional functions throughout the body, establishing the complex interplay between Wnt signaling and other signaling pathways. This crosstalk between Wnt signaling and other pathways gives Wnt signaling a vital role in many cellular and organ processes. Dysregulation of this system has been implicated in many diseases affecting a wide array of organ systems, including cancer and embryological defects, and can even cause embryonic lethality. The complexity of this system and its interacting proteins have made Wnt signaling a target for many therapeutic treatments. However, both stimulatory and inhibitory treatments come with potential risks that need to be addressed. This review synthesized much of the current knowledge on the Wnt signaling pathway, beginning with the history of Wnt signaling. It thoroughly described the different variants of Wnt signaling, including canonical, noncanonical Wnt/PCP, and the noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway. Further description involved each of its components and their involvement in other cellular processes. Finally, this review explained the various other pathways and processes that crosstalk with Wnt signaling.

Keywords: β-catenin, Canonical Wnt, Noncanonical Wnt, Signal transduction, Signaling crosstalk

Introduction

Wnt signaling is an important evolutionarily conserved pathway that regulates a diverse range of cellular activities. The importance of these pathways in cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration has led to extensive study of its various components, but there is still much to be learned and discovered about this pathway and its various interactions with other pathways. The extent of the research on this pathway has led to it becoming the subject of many evolving therapies. Many of its components have been implicated in the development of treatments for various conditions, such as cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, congenital disorders, and even diabetes and heart disease. Wnt signaling is truly a fundamental pathway to much of human development and health.

The discovery of the first Wnt gene dates back 40 years ago to 1982 during experiments intended to discover proto-oncogenes via activation by proviruses.1,2 These experiments led to the discovery of int1, which causes a tumor of mammary epithelial cells when activated.1 Eventually, it was discovered that mice and human int1 homologs shared 99% of their amino acid sequences, elucidating the high degree of conservation of the int1 proto-oncogene.3 Prior to this, Sharma and Chopra identified a gene that codes for the development of the wings in Drosophila melanogaster, naming the gene wingless (Wg).4 Additionally, molecular hybridization identified a similar int1 homologue in Drosophila.5 This gene was initially called Dint1, but isolation and sequencing of clones of the Dint1 gene determined that it was identical to the Wg gene.5, 6, 7 Later, it was decided that the int1 and Wg genes would be named together as Wnt1 to reduce confusion with the other int genes. Int2 was renamed to FGF3, int3 was renamed to Notch4, and int4 is now called Wnt3A.8 The Wnt ligands are now known to be a group composed of 19 glycoproteins that each bind receptors at the cell surface to trigger intracellular signaling cascades to modulate gene expression.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Each of the Wnt ligands is a cysteine-rich protein that is 350–400 amino acids in length, with an N-terminal signal sequence targeting them for secretion (Table 1).14

Table 1.

List of Wnt genes and orthologs in humans and model organisms.

| Human |

Mouse |

Xenopus |

Zebrafish |

Drosophila |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt Gene | Chr | Ortholog | Chr | Ortholog | Ortholog | Ortholog |

| WNT1 | 12 | Wnt1 | 15 | Wnt1 | Wnt1 | Wg |

| WNT2 | 7 | Wnt2 | 6 | Wnt2a | Wnt2 | |

| WNT2B/13 | 1 | Wnt2b/13 | 3 | Wnt2b | Wnt2b | |

| WNT3 | 17 | Wnt3 | 11 | Wnt3 | Wnt3 | |

| WNT3A | 1 | Wnt3a | 11 | Wnt3a | ||

| WNT4 | 1 | Wnt4 | 4 | Wnt4 | Wnt4a & Wnt4b | |

| WNT5A | 3 | Wnt5a | 14 | Wnt5a | ||

| WNT5B | 12 | Wnt5b | 6 | Wnt5b | Wnt5b | |

| WNT6 | 2 | Wnt6 | 1 | Wnt6 | DWnt6 | |

| WNT7A | 3 | Wnt7a | 6 | Wnt7a | Wnt7 & Wnt7a | DWnt2 |

| WNT7B | 22 | Wnt7b | 15 | Wnt7b | ||

| WNT8A | 5 | Wnt8a | 18 | Wnt8a | Wnt8a | DWnt8/WntD |

| WNT8B | 10 | Wnt8b | 19 | Wnt8b | Wnt8b | |

| WNT9A | 1 | Wnt9a/14 | 11 | DWnt4 | ||

| WNT9B | Wnt9b/15 | 11 | ||||

| WNT10A | 2 | Wnt10a | 1 | Wnt10a | Wnt10a | DWnt10 |

| WNT10B/12 | 12 | Wnt10b | 15 | Wnt10b | Wnt10b | |

| WNT11 | 11 | Wnt11 | 7 | Wnt11 & Wnt11R | Wnt11 | |

| WNT14 | 1 | |||||

| WNT16 | 7 | Wnt16 | 6 | Wnt16 | ||

Wnt ligand family: canonical vs. noncanonical

Canonical and noncanonical Wnt ligands

Wnt signaling can be categorized into two pathways, the β-catenin-dependent pathway (canonical) and the β-catenin-independent pathway (noncanonical).15,16 The canonical pathway is important for inducing cell proliferation, differentiation, and maturation.16 It is also vital in producing proper body-axis specifications.17 The pathway is activated via the Wnt1 class ligands, which include Wnt2, Wnt3, Wnt3a, and Wnt8a.17 The canonical pathway is associated with the transport of β-catenin to the nucleus upon Wnt binding to the Frizzled (Fz or Fzd) receptor and the coreceptors LDL-receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 (LRP5 and LRP6)18,19 (Fig. 1). The Fz receptor contains a cysteine-rich domain (CRD) that is used to bind Wnt.20 In mammals, 10 Fz receptors have been identified.17,21

Figure 1.

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway. The left panel (A) demonstrates the activated Wnt signaling cascade, while the right side portrays the inhibited Wnt signaling cascade. Wnt binds to the Fz receptor and LRP5/6 co-receptor. This activates Dvl to cause the dissociation of Axin from the destruction complex, causing β-catenin to be stabilized and enter the nucleus. β-Catenin can then displace the inhibitory TLE/Groucho complexes, enabling TCF/LEF to transcribe the target genes. PP2A can also enhance Wnt signaling by dephosphorylating β-catenin, APC, and Axin. The result is the preservation of β-catenin by preventing ubiquitination and proteasomal breakdown. In the absence of Wnt signaling (B), the destruction complex breaks down β-catenin and inhibits gene transcription. Several other proteins also contribute to the inhibition of Wnt signaling. Dkk1 associates with Krm1 or Krm2 and LRP5/6, causing endocytosis of the LRP5/6 co-receptor. Wise/sclerostin binds to LRP5/6 to inhibit proper Wnt association with the coreceptor. xCer-L and WIF-1 both bind to Wnt ligands to inhibit signaling. IGFBP-4 functions as a competitive inhibitor of Wnt signaling by associating with LRP6 and Fz8, while sFRPs complex with Fz receptors to prevent Wnt ligand binding. The illustration was inspired by and created in BioRender.

If Wnt ligand binding does not occur, a destruction complex that is normally inhibited by Wnt removes the β-catenin. This destruction complex is composed of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein, Axin, serine/threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), casein kinase 1 (CK1), the E3-ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP, and protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A).22 While PP2A can impact Wnt signaling either positively or negatively in a cellular context-specific fashion,23 CK1 phosphorylates β-catenin at the Ser45 residue first, in a process called “priming”. This enables GSK-3 to phosphorylate the Ser33, Ser37, and Thr41 residues, which ultimately creates the binding site for the β-TrCP protein.22,24 The β-TrCP protein functions as an adaptor protein that complexes with Skp1/Cullin machinery to ubiquitinate β-catenin, enabling the destruction of β-catenin by the proteasome.22,24,25

The binding of Wnt to the Fz receptors and LRP 5/6 transports disheveled protein (Dvl) to the cell membrane, leading to phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tails of LRP 5/6. The LRP 5/6 can then bind Axin, removing it from the destruction complex, thus causing the complex to disassemble and release the β-catenin.14,26,27 This results in the stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm, and then its translocation to the nucleus and binding with the transcription factors TCF/LEF (T-cell factor/Lymphoid enhancer factor) and thus gene expression.14,26,28 Without β-catenin, the TCF/LEF complex is joined with the transducing-like enhancer protein (TLE/Groucho), which recruits HDACs, leading to transcriptional repression. However, β-catenin binding to TCF/LEF displaces the TLE/Groucho complexes and leads to the recruitment of activators to modify the interacting proteins, such as CBP/p300, Pygo, BCL9, and BRG129 (Fig. 1).

In contrast with the canonical pathway, noncanonical Wnt signaling is β-catenin-independent, as previously mentioned, and involves the Wnt5a type ligands, which include Wnt 4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, and Wnt11 15,17. Additionally, the noncanonical pathway involves different functions in comparison to the canonical pathway, such as dictating cellular polarization and migration.17,30 Noncanonical Wnt signaling follows two distinct pathways, the Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway and the Wnt/calcium (Ca2+) pathway.17,30

The Wnt/PCP pathway, like the canonical pathway, predominantly uses Fz receptors to bind Wnt (Fig. 2). These Fz receptors utilize several coreceptors, including protein tyrosine kinase 7 (PTK7),31 muscle-skeletal receptor tyrosine kinase (MUSK),32 tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor (ROR1/ROR2),33 tyrosine kinase related receptor (RYK),34 syndecan,35,36 and glypican.37,38 However, the Wnt/PCP pathway also uses Celsr1 and Vangl2 receptors, although the ligand-receptor binding interaction is still relatively unknown39 (Fig. 2). The Fz receptors in this pathway bind Wnt ligands and phosphorylate Dvl, leading to the recruitment of Inversin (Invs).40 The polarity protein Par6 interacts with Dvl, and Smad ubiquitination regulatory factor (Smurf) is recruited by the phosphorylated Dvl and binds to Par6. Smurf then ubiquitinates Prickle, a protein that normally inhibits Wnt/PCP signaling, targeting it for proteasomal destruction.41 The breakdown of Prickle enables Dvl to associate with the Dvl-associated activator of morphogenesis (DAAM). This complex can then activate Ras homologue gene-family member A (RhoA), but not Rac1 or Cdc24.15,39 DAAM also activates Profilin.42 Rac1 activates JNK, which phosphorylates and activates c-Jun to go to the nucleus and initiate gene expression.43,44 JNK also activates CapZ-interacting protein (CapZIP) via phosphorylation.45 RhoA activates RHO-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase (ROCK) and diaphanous 1 (DIA1).46,47 ROCK activates the myosin II regulatory light chain (MRLC).48,49 CapZIP, MRLC, DIA1, and profilin all contribute to actin polymerization, which is vital to cell polarity and migration.39 The Celsr1 receptor appears to function similarly to the Fz receptor, where Wnt binding ultimately causes activation of Dvl to stimulate the same signaling cascade. On the other hand, the binding of Wnt on Vangl2 causes dissociation of a complex of Dvl, Prickle, and inturned (Intu), enabling Dvl to complex with Invs39 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The noncanonical Wnt/PCP pathway. The binding of Wnt ligands leads to the phosphorylation of Dvl, which recruits Invs, Par6, and Smurf. Smurf ubiquitinates the inhibitory protein Prickle, targeting it for destruction. Dvl can then associate with DAAM, activating Rac1, profilin, and RhoA. Rac1 activates JNK, which phosphorylates c-Jun and CapZIP. c-Jun then goes to the nucleus to stimulate gene transcription. RhoA activates ROCK and DIA1, with the latter activating MRLC. CapZIP, MRLC, DIA1, and profilin all stimulate actin polymerization. Celsr1 stimulates Dvl due to Wnt binding like the Fz receptor. Wnt binding to the Vangl2 receptor causes dissociation of Prickle and Intu from Dvl, which can then bind to Invs. The illustration was inspired by and created in BioRender.

The Wnt/Ca2+ pathway is predominantly activated by the Wnt5a ligand and Fzd2 receptor50,51 (Fig. 3). The binding of the Wnt5a ligand to Fzd2 triggers G protein to activate phospholipase C (PLC).52,53 PLC then cleaves phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdInsP2 or PIP2) into diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3 or IP3). DAG, along with Ca2+, activates protein kinase C (PKC) to stimulate cell–division cycle 42 (Cdc42), which causes actin polymerization to contribute to cell polarization and migration.39 Meanwhile, IP3 binds to inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (InsP3Rs) on the membrane of the ER, stimulating Ca2+ release through the Ca2+ channels and increasing cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels.39,54 Stromal interaction molecule 1/2 (STIM1/2) detects the decrease in Ca2+ in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and activates Orai family proteins (Orai1, Orai2, or Orai3) on the plasma membrane to mediate store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE).39,54 Sarcoplasmic/ER Ca2+ ATPases (SERCAs) then pump Ca2+ back into the ER.39,54 The increased cytosolic Ca2+ from IP3 binding to InsP3R not only stimulates PKC but also stimulates calcineurin and CAMKII. Calcineurin activates the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), which causes gene transcription.55,56 On the other hand, CAMKII stimulates TGF-β-activated protein kinase 1 (TAK1), which then activates Nemo-like kinase (NLK).57 NLK phosphorylates TCF, inhibiting the β-catenin/TCF complex and preventing gene transcription58 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway. Wnt binding to the Fz receptor leads to G protein-mediated activation of PLC. PLC cleaves PIP2 into IP3 and DAG. IP3 binds to IP3 receptors (InsP3R) on the ER membrane to stimulate Ca2+ release. STIM1/2 detects this decrease in ER Ca2+ levels and activates Orai proteins in the plasma membrane to bring more Ca2+ into the cell, where SERCA can pump Ca2+ back into the ER. DAG can then activate PKC in the presence of Ca2+ and PKC can stimulate Cdc42 to enhance actin polymerization. The elevated intracellular Ca2+ level also stimulates calcineurin and CAMKII. Calcineurin activates NFAT, causing gene transcription. CAMKII activates TAK1, which activates NLK, when then phosphorylates TCF, preventing β-catenin-mediated gene transcription. The illustration was inspired by and created in BioRender.

Biological conservation of Wnt signaling

The Wnt signaling pathway is highly conserved. Wnt was first identified in Drosophila as the Wg protein due to mutations in the gene causing lack of wing and haltere development.4 The Wg gene is also called Dint1, as it was shown to be homologous to Int1 found in mice. This was the first connection discovered between Wnt found in Drosophila and Wnt found in vertebrates.7 In an experiment that proved the Wg gene is homologous to Int1 found in mice, van Ooyen et al sequenced the human and mouse Int1 genes in blocks of 50 nucleotides3 (Table 1). Comparison between the mouse and human Int1 genes revealed conservation of the splice sites, TATA box, and polyadenylation signal.3 Both proteins were also 370 amino acids long, with the only differences being found in the hydrophobic N-terminus.3 Homology was also established in the non-coding sequences.3 The overall homology between mouse and human Int1 homologs was 99%, revealing the conservation of the protein across species.3

Studies of cnidarians and sponges have also revealed the conservation of the Wnt signaling pathway, as the pathway was shown to be involved in the control of axis polarity.59 Petersen and Reddien further clarified that Wnt signaling is broadly used in primary body axis development.59 The Porcupine gene (Porc) codes for a transmembrane protein in the ER, allowing the processing and distribution of Drosophila Wg in vitro.60 Porc is an acyltransferase that palmitoylates the Wnt protein in the ER for secretion.61 Porc is also important for localizing Drosophila Wnt3 in the embryonic CNS.60 Tanaka et al isolated mouse Porc (Mporc) and Xenopus (Xporc) and analyzed them alongside homologous human MG61, C. elegans Mom-1, and Drosophila Porc. It was discovered that the Porc homologs among the vertebrates were well conserved via comparison of amino acid sequences, while the Drosophila Porc had an additional hydrophilic N-terminal sequence. This study revealed the conservation of Porc across species.60 Furthermore, injection of Mporc RNA into Drosophila embryos with Drosophila Porc resulted in some rescue of the embryos, albeit to a reduced extent compared to Drosophila Porc RNA. This study revealed the conservation of Porc and Porc function across multiple species.60

Biological assays for canonical vs. noncanonical Wnt classification

Various biological assays are used to identify components of the canonical and noncanonical pathways. From a broader perspective, the secondary-axis formation (i.e., axis duplication) analysis is one of the prototypes of canonical Wnt assays and can be used to assay activators and inhibitors of the canonical pathway, due to its role in proper axis specification.62 Luciferase reporter assays revealed that PTK7, a part of the noncanonical pathway, inhibits canonical Wnt signaling by precipitating Wnt3a and Wnt8 in the canonical pathway.63 Luciferase reporter assays can also be used to detect TCF/LEF activation,64,65 which are proteins that are mainly involved in the canonical pathway.28 Luciferase reporter assay could be used to form a high throughput screen for Wnt/β-catenin signaling.65 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is an assay that can be used to detect Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1), an inhibitor of the canonical pathway.66 Another type of analysis is the Western blot analysis, which can be used to detect the up-regulation of the canonical proteins β-catenin, Dvl, APC, and GSK-3 in the retina of mice.66 β-Catenin levels can also be detected using immunodetection assays.67

The Wnt inhibitory factor-1 (WIF-1), which is a member of the secreted Frizzled-related protein (sFRP) family, can inhibit both the canonical and noncanonical pathways by binding directly to Wnts, preventing them from binding to the Wnt receptor.68 Soft agar assay and Western blotting can be used to detect inhibition of osteosarcoma cell growth as a result of WIF-1 overexpression, providing insight into the regulation of both pathways.64

In the noncanonical Wnt pathway, Wnt5a is the most prominent ligand, using the ROR family of tyrosine kinases as receptors.69 A member of the kinesin family, Kif26b, is a downstream effector of the Wnt5a-ROR pathway, mediating cell migration during embryonic development.70 Hence, a Wnt5a-ROR-Kif26b (WRK) reporter assay was developed and could be used to measure the degree of Wnt5a-ROR signaling in real-time, utilizing a combination of flow cytometry, Western blot, and time-lapse microscopy.70 A similar test involves a GFP-Kif26b reporter cell line combined with flow cytometry to detect the levels of Wnt5a in the cells.71 The GFP signal enables quantitative analysis of the cells to detect Wnt5a expression, although the assay is sensitive to cell density.71

Controlled secretion of Wnt proteins

Wnt ligands are highly lipidated in the ER, limiting the range of diffusion to localize the ligand to its recipient cell.72 Specifically, the acyltransferase Porc palmitoylates the Wnt in the ER.61 The mom-1 gene codes for a similar acyltransferase in C. elegans.73 The Wnt ligands are secreted via a Wntless (Wls) transporter, which is a conserved transmembrane protein in the Golgi apparatus that was characterized in Wg-sending cells in Drosophila.74 Banziger et al transfected embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293T) with the Wnt3a expression vector and cultured them with siRNA to knock down the expression of the human WLS (hWLS) gene. Assaying the level of Wnt3a protein revealed that siRNA-treated hWLS (sihWLS) cells could not activate the Wnt pathway due to, at least in part, the lack of secretion of Wnt3a in the absence of the hWLS gene. This study established the importance of Wls for the secretion of Wnt ligands. Additionally, cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are also involved in Wnt signaling. Glypicans and syndecans compose the protein core of HSPGs and are covered in heparan sulfate chains.75 In Drosophila, a glypican called division abnormally delayed (dally) functions as a coreceptor for the Drosophila frizzled 2 (Dfz2) receptor.76 The dally gene specifically encodes the protein core of the HSPGs in Wg/Wnt signaling.76 Glypicans like dally also participate in transporting Wnt ligands toward target cells.74

Wnt receptors, co-receptors, and accessory proteins

Cognate receptors: the frizzled (Fz) proteins

Frizzled (Fz) is a seven-pass transmembrane receptor that binds Wnt ligands.77 The Fz genes generate Fz receptors, each of which ranges from 500 to 700 amino acids long, with a CRD on the N-terminus and a 40 to 100 amino acid-long hydrophilic linker region.78 The seven transmembrane domains are hydrophobic alpha-helices.78 Fz protein localizes in the plasma membrane, with the cysteine-rich N-terminus oriented extracellularly and the carboxy-terminus oriented intracellularly towards the cytoplasm.21,79,80 The intracellular carboxy-terminus is variable in length and not well conserved between the different Fz receptor types.78 Fz is also glycosylated79 and there are 10 Fz genes organized into four clusters.78 By amino acid sequence, Fzd1, Fzd2, and Fzd7 are 75% similar; Fzd5 and Fzd8 are 70% similar; Fzd4, Fzd9, and Fzd10 are 65% similar; and Fzd3 and Fzd6 are 50% similar.81 Comparison of amino acid sequences between clusters yields only 20%–40% similarity.78 The relative lack of sequence similarity suggests a lack of genomic conservation between the Fz receptors.

The importance of Fz receptors in the Wnt/PCP pathway was characterized by Fz mutations in Drosophila that caused abnormal wing hair patterns and polarity disruptions, revealing the importance of Fz in the Wnt/PCP pathway.82,83 Loss of function and overexpression mutations in Fz altered the assembly location of F-actin in wing development, indicating that Fz is important in cytoskeletal development.79 The misorientation of hairs also revealed the importance of Fz in not only receiving the Wnt signal but also propagating it in a proximal-distal direction.84 Mutations in Fz receptors also cause the defective orientation of the ommatidia (individual units composing a compound eye).85

Mutations in the frizzled 4 (Fzd4) receptor causes familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR), a disease that generally results in the lack of retinal angiogenesis. This leads to a variety of symptoms, including retinal fibrosis, detachment, and dysplasia.86 Mutations in Fzd1 and Fzd2 in mice caused cleft palate and ventricular septal defects (VSD). These mutations also affected neural tube closure and inner ear development. Fzd7 mutations also caused VSDs but were more commonly associated with a kinked tail.87 Knockout of Fzd5 in mice led to embryonic lethality due to placental insufficiency.88 Loss of Fzd5 also caused retinal cell death and excessive mesenchymal cells in the vitreous cavity among other issues.89 Loss of Fzd8 alone causes no phenotypic change, although the loss of even a single Fzd8 allele can increase the severity and penetrance of the ocular effects from loss of Fzd5.90 Homozygous loss of Fzd9 has yielded B-cell developmental abnormalities, defective visuospatial learning, and bone mass reduction compounded by osteoblast dysfunction.21 Homozygous Fzd6 deletions cause randomized hair follicles, generating waves, whorls, and tufts.91 Homozygous deletion of Fzd3 in mice causes inappropriate development of peripheral and central axons, leading to the inability to detect thermal and mechanical stimuli from the feet.92 Concomitant deletions in Fzd3 and Fzd6 cause neural tube closure defects and misorientation of inner ear hair cells, indicating their similar functions.93

Co-receptors: LRP5 and LRP6 proteins

Low-density-lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5/6 (LRP5/6) are single-pass transmembrane proteins that function as coreceptors for Fz receptors.19,94 The binding of the Wnt ligand triggers the dimerization of Fz and LRP5/6 94. This leads to the phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tail of LRP5/6 at five conserved PPPSP (also called the PPPSPXS) motifs.95,96 Several protein kinases are involved in this phosphorylation, including GSK-3, which is part of the destruction complex that normally binds β-catenin in the absence of Wnt signaling.94,97 The PPPSP motifs bind Axin from the destruction complex, inhibiting β-catenin phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitination that leads to proteasomal breakdown.95,96,98 LRP5 and LRP6 are homologous and expressed in embryogenesis.19 However, LRP6 is more important during embryogenesis, as evidenced by mice with homozygous deletion of Lrp6 demonstrating axial skeleton truncation, neural tube closure defects like spina bifida, as well as midbrain and hindbrain malformations.99 On the other hand, homozygous deletion of Lrp5 caused low bone mass due to decreased osteoblast activity, defective capillary cell apoptosis in the eye, defective clearance of chylomicrons, and impaired insulin secretion.100,101

Accessory Wnt binding proteins at the cell membrane

R-spondins

Roof plate specific-spondins (R-spondins) are four members of a larger family that contain thrombospondin type 1 repeats (TSR-1).102 The R prefix was given based on the first R-spondin due to its expression in the boundary of the roof plate and neuroepithelium in the dorsal neural tube.103 The R-spondins also contain an N-terminal signal peptide, two furin-like (FU1 and FU2) cysteine-rich domains near the N-terminus, and a C-terminal region with many positively charged amino acids.102,104 The R-spondins can bind to leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptors 4–6 (Lgr4-6).105 R-spondins bind Lgr4-6 via their FU2 domain and can bind ZNRF3 and RNF43 via their FU1 domain.106

ZNRF3 and RNF43

ZNRF3 and RNF43 are E3 ubiquitin ligases that target Wnt receptors for destruction to decrease Wnt signaling responses.107 ZNRF3 is a member of the ZNRF protein family, a family of E3 ubiquitin ligases that contain a zinc finger and a RING domain.108 R-spondins can bridge ZNRF3/RNF43 and LGR4/5/6, inhibiting ZNRF3/RNF43 activity via auto-ubiquitination and membrane clearance.106,109 In this manner, R-spondins act as Wnt agonists. RNF is a homolog of ZNRF43 that also contains a RING domain for its function as an E3 ubiquitin ligase.109

Derailed/Ryk

Derailed/Ryk (related to tyrosine kinase) is a member of the atypical tyrosine kinase family consisting of a Wnt inhibitory factor (WIF) domain extracellularly, an atypical kinase domain intracellularly, and a PDZ binding motif. Derailed is the Drosophila homolog, while Ryk is found in mammals.110 Interestingly, the tyrosine kinase domain is considered atypical due to sequence variations in the normally conserved tyrosine kinase residues. The domain lacks tyrosine kinase activity.111 The WIF domain of Ryk binds to Wnt1 and Wnt3a to activate TCF for the transcription of target genes.110 Ryk also forms a ternary complex with Wnt1 and Fz using its extracellular WIF domain, while the intracellular kinase domain binds to Dvl using its PDZ binding motif to activate TCF in response to Wnt3a stimulation.110 In Drosophila, Derailed was found to be important in learning and memory.112 Derailed/Ryk was also found to be important in axon guidance via interaction with Wnt5.113 The C. elegans homolog, lin-18, is important in determining vulval cell fate patterning.114

Receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptors (RORs)

RORs are members of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family that are highly conserved and consist of two members, ROR1 and ROR2.115 ROR1 and ROR2 are single-pass transmembrane receptors with an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain and a proline-rich domain (PRD) that is flanked by two serine–threonine rich domains.116 The extracellular side of the ROR contains an immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domain, a CRD, and a Kringle domain (KRD). The CRD of ROR1 and ROR2 is like those on Fz receptors.117 ROR1 and ROR2 play crucial roles in embryonic development. Mice lacking ROR2 expression have shortened limbs and tails, facial abnormalities, and dwarfism among other issues.118 Mutations in ROR2 also cause Robinow syndrome and Brachydactyly type B in humans.119, 120, 121 Wnt5a binds ROR2, causing heterodimerization of ROR2 with Fz2 using its CRD. RORs can activate the noncanonical Wnt/JNK-PCP pathway and inhibit the canonical β-catenin/TCF pathway.122 However, the components of the Wnt/ROR pathways are still mostly unknown.122 ROR1 is expressed in B-lymphocyte precursors and can rarely cause precursor-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).123 ROR1 and ROR2 in mice have been known to play an important role in the development of the nervous system.124

Gpr124 and Reck

Gpr124 is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) and Reck is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein.125 Reck binds to Wnt7, creating the Reck/Wnt7 complex that binds to Gpr124. This complex then joins with the Fz receptor and LRP5/6 coreceptor to stimulate canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling.125, 126, 127 The Gpr124 and Reck coactivators are vital in the development of the blood–brain barrier (BBB).128 Gpr124 knockout mice demonstrated microvascular hemorrhage and lethality in the embryo. Interestingly, Gpr124 deletion did not affect BBB integrity in adult mice.128

Intracellular mediators of Wnt signaling

The intracellular component of the Wnt signaling pathway is composed of several proteins for each pathway. This section will give a brief overview of each component of the canonical and two noncanonical Wnt pathways, looking further at the additional functions of the components outside of Wnt signaling. A description of the functions in Wnt signaling and the signaling cascade will be described in the canonical vs. noncanonical Wnt section. The inhibitors will also be discussed later. For the canonical pathway, the binding of Wnt to Fz and LRP5/6 mediates signal transduction to the nucleus via β-catenin (Fig. 1).

Intracellular mediators of the canonical pathway

β-Catenin was discovered to have two functions, one of them being its association with α- and γ-catenin to link Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) to cytoskeletal structures.129 The term catenin was given to these three molecules due to its linkage of the CAM, E-cadherin, to cytoskeletal structures.129 The second function of β-catenin is its role in Wnt signaling, which was discovered through the analysis of its Drosophila homolog, Armadillo (Arm). Seminal screens for mutations that caused altered segmentation of Drosophila embryos revealed the signaling potential of β-catenin.130 Additionally, mutations in Wg in Drosophila caused a corresponding decrease in Arm, leading to altered segment polarity, further delineating the link between Wnt signaling and β-catenin.131 Further studies would later reveal that β-catenin mediates its effects via the TCF/LEF transcription factors, stimulating the transcription of target genes.132

β-Catenin is a 781 amino acid long protein with 12 Arm repeats, which forms a super-helical structure composed of multiple α-helices with a hydrophobic core.133 The superhelix contains a large, positively charged groove that allows β-catenin to interact with cadherins, TCF, and APC.133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139 β-Catenin then binds TCF and LEF to mediate gene transcription (Fig. 4). Interestingly, TCF is considered a transcriptional repressor, while LEF is considered a transcriptional activator.140 TCF/LEF binds to DNA via its HMG box domain, which recognizes a sequence called the Wnt/Wg response element (WRE) on the DNA.141,142 The HMG domain binds to the WRE in the minor groove of the DNA, causing the DNA to bend.142 In addition to the HMG domain, TCF/LEF also contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) that makes nonspecific contacts with the phosphate backbone of the DNA, increasing TCF/LEF affinity for the DNA.142

Figure 4.

β-Catenin protein interactions. Some of these proteins were not discussed in this paper due to space constraints. Among those that have been discussed in this paper, there are notable inhibitors and activators. GSK-3β, CK1, APC, Axin, and β-TrCP are inhibitors of β-catenin as part of the destruction complex. PP2A has dual effects; it can dephosphorylate β-catenin to prevent ubiquitination and stabilize β-catenin, while it can also dephosphorylate GSK-3β, which can then inhibit β-catenin. YAP/TAZ is another inhibitor, as it can either bind to and suppress β-catenin without affecting its levels or associate with the destruction complex. Smad7 and Smurf2 can complex with β-catenin to ubiquitinate and degrade the protein. SUFU can export β-catenin from the nucleus. On the other hand, there are several activators of β-catenin, proteins that are activated by β-catenin, and proteins that assist with the functions of β-catenin. Smad3 is a chaperone protein that transports β-catenin into the nucleus. TCF/LEF are transcription factors that are activated by β-catenin. α- and γ-catenin join with β-catenin to link CAMs like E-cadherin to cytoskeletal structures, strengthening cell adhesion. It is noteworthy that some of the protein interactions are species-, tissue-, and/or context-dependent. The illustration was inspired by the Wnt homepage created and maintained by the Nusse Lab at Stanford University (http://web.stanford.edu/group/nusselab/cgi-bin/wnt/protein_interactions) and reference 137.

Intracellular mediators of noncanonical Wnt/PCP pathway

Dvl proteins

There are two noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways, the Wnt/PCP pathway, and the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway. The Wnt/PCP pathway involves several additional receptors and co-receptors that will be discussed in later sections. The first intracellular mediator of Wnt/PCP signaling is Dvl. All Dvl proteins contain three conserved domains, a DIX domain at the N-terminus, a central PDZ domain, and a DEP domain at the carboxy-terminus.143 In between the DIX and PDZ domains is a “basic region” composed of conserved Ser and Thr residues. Between the PDZ and DEP domains is a “proline-rich region".143 The DIX domain primarily activates the canonical pathway, enabling dynamic polymerization of Dvl to form puncta, which can then interact with Axin to prevent it from mediating the destruction of β-catenin.144 Although further research needs to be conducted to delineate the exact process of this interaction between Dvl and Axin, it has been theorized that the DIX domain of Dvl interacts with the similar DIX domain on Axin to induce a conformational change in Axin or relocates Axin.144 The PDZ domain is involved in both the canonical and noncanonical pathways.145 It binds the Fz receptor at its C-terminal conserved Lys-Thr-X-X-X-TRP (KTXXXW) motif.146 This motif is required for the activation of the canonical pathway, although the molecular mechanisms are poorly understood.147 The DEP domain activates the noncanonical pathway by mediating the interaction between Dvl and DAAM1.143 The DEP domain also translocates the Dvl protein to the plasma membrane after Wnt stimulation.148

Dvl has an NLS located between the PDZ and DEP domain (aside from the proline-rich region), and an NES (nuclear export signal) located between the DEP and C-terminus.143 Increasing evidence indicates that nuclear Dvl protein is critical for β-catenin and TCF factors to form a complex.149 Dvl has been shown to interact with many other transcriptional factors including FOXK1/2, TAZ, and HIPK1, as well as gene promoters such as CYP19A1.149 Furthermore, Dvl1 was shown to interact with EZH2 while Dvl3 interacts with chromatin-modifying enzymes such as KMT2D in cancer cells. In addition, Dvl proteins are extensively modified post-translationally by phosphorylation, lysine acetylation, and methylation, as well as ubiquitination, although the functional roles of Dvl post-translational modifications remain to be fully investigated.149

Inversin (Inv) protein

Inversin (Inv) is a 1062 amino acid long protein with characteristic 15 successive ankyrin repeats. It was first identified in Inv mutant mice that had situs inversus (reversed left/right polarity), underdeveloped tubules, and cyst formation in the kidneys.150 This discovery linked Inv to Wnt signaling. Simons et al used glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing the PDZ domain of Dvl to characterize the effect of Inv. The Inv directly interacted with the GST fusion protein. Inv also formed a protein complex with Dvl, indicating that it could inhibit the canonical pathway.151 Inv also participates in the noncanonical pathway, interacting with the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway proteins Strabismus (Stbm) and Prickle (Pk) like the Drosophila PCP protein Diego.151 Inv mutant mice developed renal cysts due to unopposed canonical Wnt signaling, which causes overgrowth of cells without terminal differentiation of renal tubular epithelial cells.151

Par6 protein

Par6 serves as a polarity protein and a scaffolding protein with other molecules.152 The scaffolding function is beneficial in complexing with Dvl and Smurf in the noncanonical pathway.41 Its cell polarity function is mediated by the G-protein-activated phospholipase C-Beta (PLC-β) interacting with Par proteins like Par6 through multiple PDZ domains that can bind the extreme C-terminal S/TXL motifs of PLC-β.152 This activates the PLC-β to hydrolyze PIP2 into IP3 and DAG, two important secondary messengers. IP3 and DAG play important roles in regulating cell polarity and asymmetric cell division.152

Smurf1 and Smurf2 proteins

Smurfs (Smurf1 and Smurf2) are E3 ubiquitin ligases of the C2-WW-HECT family of proteins.153 They were first identified in the ubiquitination and degradation of R-Smads in the BMP pathway to antagonize TGF-β/BMP signaling.154 Smurf1 contains a phospholipid/Ca2+ binding domain on its N-terminus, two WW domains for binding to PPXY (also called PY) motifs on other proteins, and a HECT domain on the C-terminus for ubiquitination of target proteins.154 Smurf1 targets Smad1 and Smad5 using its WW domains, which bind to the PY motifs on Smad1 and Smad5, enabling their degradation.154 Smurf2 uses the same mechanism to degrade Smad1 and Smad2.155 Smurf1 can also be recruited by Par6 to target RhoA for degradation, establishing the proper cell polarity needed for cell movement.156 Smurf1-induced RhoA degradation in tight junctions leads to their dissolution and enables TGF-β dependent epithelial–mesenchymal transition.157 These results indicate the importance of Smurfs in noncanonical Wnt/PCP signaling.

Prickle (Pk) protein

Prickle (Pk) is also involved in the Wnt/PCP pathway. Pk is considered a type 1 polarity gene along with Dvl and Fz because it affects the body surface and is believed to directly establish tissue polarity. On the other hand, type 2 and 3 tissue polarity genes affect specific body regions and are believed to interpret the polarity that the type 1 genes have established.158 All Pk proteins contain three LIM motifs and a conserved domain called Prickle Espinas Testin (PET).158 The LIM motifs are cysteine-rich domains with two zinc fingers that are joined by an amino acid spacer.159 The LIM domains bind target proteins and enable protein–protein interactions.158 The PET domain is monomeric and works with the LIM motifs to target Dvl to the cell membrane to facilitate its function in the Wnt/PCP pathway.160 Pk also has a prenylation motif on its C-terminus that is important but not required for its localization to the plasma membrane.161

Dvl-associated activator of morphogenesis (DAAM)

DAAM is a conserved actin nucleator that is a member of the formin family.162 DAAM members contain a GTPase binding domain (GBD), a diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID), an N-terminal dimerization domain (DD), a coiled-coil (CC), an FH1 domain, an FH2 domain, and a diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD). DAAM is highly expressed in tissues like the CNS, somites, dermomyotomes, and the heart and is important in organ symmetry. Specifically, it causes left-right (LR) symmetry due to its modulation of the myosin 1D (Myo1D) function. Drosophila Myo1D induces dextral twisting, which is important for orienting the native LR organs in larvae. The absence of Myo1D leads to situs inversus.163 DAAM nucleates F-actin, promoting the assembly of an F-actin network that enables Myo1D to induce chirality.162 Interference of DAAM with RNAi suppressed the expected 180-degree dextral rotation of the larval body, reducing it to just 90°. This experiment revealed the importance of DAAM in inducing proper chirality in Drosophila larvae.162 The FH2 domain is particularly important in actin nucleation and polymerization, while the FH1 domain interacts with profilin-actin during actin filament elongation.42

Profilin protein

Profilin is a protein associated with non-muscle actin (β- and γ-actin) and is involved in the control of actin polymerization. It was first isolated from calf spleens as a small protein that accompanied an actin-containing complex.164 When complexed with actin, profilin is called profilactin.165 Profilin contains a core of seven-stranded β-pleated sheets with α-helical N- and C-termini on one side, and two shorter α-helices on the other. The N- and C-termini form the poly-l-proline (PLP) binding surface, which enables profilin to bind actin and factors that participate in actin nucleation and elongation.166 Profilin inhibits spontaneous actin nucleation and polymerization by sequestering G-actin. However, it can also promote actin filament elongation using its PLP binding domain to interact with other proteins such as formins, Ena/vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), Arp2/3-dependent Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), and WASP family verprolin-homologous protein (WAVE) family.166,167 Profilin also facilitates the exchange of ADP for ATP on actin monomers, further enhancing polymerization.166,167 Interaction with formins allows profilin to associate with microtubules and increases the rate of depolymerization.168 With profilin as a mediator, DAAM1 can mediate cytoskeletal reorganization and cell movement for important processes such as gastrulation.169

Rac1 and RhoA proteins

Rac1 and RhoA are members of the Rho family of small GTPases.170 Both proteins are involved in a wide variety of cell processes, such as motility, proliferation, migration, and polarity via their regulation of actin polymerization.171 Both have conserved GDP/GTP binding domains called the G domain and a C-terminal region that contains a CAAX motif.172 The binding of GTP to Rac1 causes two regions (amino acids 25–40 and 60–76) called switch I and II to undergo a conformational change to interact with specific downstream effectors in the signaling cascade.171 Rac1 and RhoA can also undergo post-translational modification to prenylate the C-terminal CAAX motif, enabling membrane interaction.171 This association with the membrane is what enables Rac1 and RhoA to stimulate downstream signaling cascades to modulate cellular functions.170 The exchange of GDP for GTP is mediated by Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEFs) and GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), triggering the active state of Rac1 and RhoA to interact with downstream proteins.171,173 Guanosine dissociation inhibitors (GDI) can conceal the C-terminal isoprenyl motif in a hydrophobic pocket, sequestering Rac1 in the cytoplasm and preventing downstream activation.173,174 GDI also prevents GDP/GTP exchange to keep both in their inactive states.171,174 RhoA and Rac1 are spatially separated, with Rac1 active towards the leading edge of the cell, while RhoA is active towards the lagging edge.170 The two are also temporally segregated, with RhoA activity peaking before Rac1 in a coordinated cycle of protrusion and retraction. Rac1 and RhoA can antagonize each other mutually to coordinate this effect.175 Dysregulation of Rac1 and RhoA have been linked to cancer, as well as cognitive and cardiovascular diseases.172

Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK)

ROCK (also called RhoA/Rho kinase) is a Ser/Thr kinase that is stimulated by Rho.46,47,176,177 ROCK comes in two isoforms, ROCK1 and ROCK2. ROCK1 is 1354 amino acids long, while ROCK2 is 1388 amino acids long.178 They share 64% of their primary amino acid sequences, 92% homology in the kinase domains, and only 55% homology in the coiled-coil domains.178 The N-terminal region contains the ROCK kinase domains.178 The C-terminal region contains the coiled-coil domain and a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain; this region binds to the catalytic kinase domain to inhibit its activity. The coiled-coil domain contains a Rho-binding region that enables GTP-bound RhoA to disrupt the binding of the C-terminus and the kinase domain.179 The C-terminal region can also be cleaved by caspases during apoptosis to activate ROCK.180,181 Activated ROCK can associate with mammalian DIA (mDia) to stimulate actin cytoskeletal reorganization.177,182 ROCK proteins are generally expressed in many tissues and phosphorylate target proteins on R/KXXS/T or R/KXS/T amino acid motifs.178 ROCK proteins are involved in forming stress fibers composed of bundles of F-actin and myosin II.183 Focal adhesion complexes bind these fibers to the inner plasma membrane.184 The activation of ROCK by caspases gives ROCK a crucial role in forming membrane blebs during apoptosis.180,181 ROCK also plays a role in embryonic development, inducing cell migration, differentiation, and axis formation through its expression in the cardiac mesoderm, lateral plate mesoderm, and neural plate.178

c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)

JNK is a member of the three mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways that control cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation.185 The MAPK pathways are all activated by a series of phosphorylation reactions. JNK is activated by the MAP2K enzymes MKK4 and MKK7.186 Scaffold proteins just as JNK interacting protein 1 (JIP1) facilitate rapid activation of the JNK pathway.187 The JNK pathway can be inactivated by dual-specificity phosphatases (DUSPs).188 The JNK family contains three genes that can be spliced into 10 isoforms, namely, JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3. JNK1 and JNK2 are expressed in a variety of tissues, while JNK3 is expressed in the brain, heart, and testis.185 The protein products of these three genes are about 400 amino acids long, with a canonical Ser/Thr kinase domain.189 JNK is best known for inducing apoptosis via stimulating the mitochondrial release of cytochrome C to activate caspase and trigger apoptosis.190 However, the effects of JNK are context-specific, as JNK can phosphorylate anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 to promote apoptosis, but it can also phosphorylate pro-apoptotic BAD protein to prevent apoptosis.185 The dysregulation of JNK is linked to multiple diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and autoimmune diseases. JNK3 is being investigated as a potential target for the treatment of CNS disorders.191

C-Jun is the major substrate for JNK.185 c-Jun is a subunit of the transcription factor, activator protein 1 (AP-1).192 Anti-c-Jun antibodies caused partial G0 arrest in the cell cycle,193 while overexpression produced a greater transition into the S, G2, and M phases.194 Indeed, c-Jun is crucial in the regulation of the G1/S phase transition.195 c-Jun also plays an important role in both inducing and inhibiting apoptosis.196 Endogenously, c-Jun inhibits the expression of apoptosis-inducing genes and maintains cell survival, particularly p53 196,197. However, JNK signaling can cause c-Jun to induce apoptosis via survival factor removal.198 JNK phosphorylates the Ser63 and Ser73 residues of the c-Jun activation domain, causing AP-1 transcriptional activity to increase.199 This can cause the induction of apoptosis, although AP-1 is also involved in the inhibition of apoptosis as well depending on the tissue and developmental stage.196 As one might assume, c-Jun, along with JNK has been implicated in many cancers.185,197

CapZ-interacting protein (CapZIP)

CapZIP is a protein detected in muscle extracts that interacts with the F-actin capping protein CapZ. Capping proteins normally inhibit actin polymerization, preserving the actin monomer pool.200 In humans, CapZIP is phosphorylated at Ser-179 and Ser-244 by mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAP-K2).45 CapZIP serves as a substrate for stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs), which can also phosphorylate it at several sites (Ser-68, Ser-83, Ser-108, and Ser-216).45 Cell exposure to various stressful events causes the activation of several MAPKs, including SAPKs, JNK1, and JNK2. When under stress, SAPK3 and SAPK4 will phosphorylate CapZIP, triggering the dissociation of CapZIP from CapZ and enabling CapZ to modify actin filaments.45 JNK1 can also phosphorylate CapZIP, although slower and less extensively.45 Northern blot analysis reveals that CapZIP is expressed highly in skeletal muscle but to a lesser extent in cardiac muscle. In other organs such as the brain, lung, and liver, it is hardly detectable at all.45 Multiple-tissue expression arrays revealed that CapZIP is expressed in immune organs like the thymus, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow.45 CapZIP is also expressed in immune cells and has been isolated from B cells, as well as leukemia and lymphoma cell lines.45 CapZIP also regulates ciliogenesis via its upstream regulator Dvl. Dvl binds to ERK7 and CapZIP, functioning as a scaffold for a MAPK family member, ERK7 (also called MAPK15), to phosphorylate CapZIP, enabling ciliogenesis.201

Myosin II regulatory light chain (MRLC)

MRLC is a regulatory component of myosin II. Myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) phosphorylates the Ser19 residue of MRLC, and sometimes can even phosphorylate the Thr18 residue.202 This enhances the activity of the actin-activated Mg2+ ATPase in myosin II, increasing the assembly and stability of myosin II filaments. The dephosphorylation of MRLC increases myosin II activity and stability more so than monophosphorylation.203,204 However, both forms of MRLC are required for organizing stress fibers during interphase and forming the contractile ring in cell division.202 Dephosphorylation is also important for the disassembly of previous myosin filaments to form new ones.205 ROCK1 can phosphorylate MRLC to facilitate the generation of traction for cell motility.206 ROCK proteins also dephosphorylate MRLC,205 enabling the colocalization of MRLC with actin filaments in mitotic and interphase cells.202 Diphosphorylated MRLC also induces the formation of thick actin bundles containing myosin II, while unphosphorylated MRLC inhibits actin bundle formation.202 These findings emphasize the importance of MRLC in actin organization.

Diaphanous 1 (DIA1)

DIA1 (also called mDia in mammals) is a member of the diaphanous-related formins (DRFs) that are Rho-GTPase binding proteins.46 DIA1 contains a novel formin homology (FH) 2 domain that protects the barbed end of the actin filament from capping proteins and enables rapid assembly of actin subunits.207 DIA1 also has an FH1 domain that binds profilin-bound G-actin to bring it closer to the barbed end for elongation of the actin filament.207,208 DIA1 contains a Rho-GTPase binding domain in the N-terminal region and a Diaphanous-autoregulatory domain (DAD) in the C-terminal region. The N-terminal regulatory region is usually bound to DAD, causing autoinhibition. However, the binding of RhoA relieves this inhibition.209,210 DIA1 is involved in a variety of processes, such as mechanotransduction, cell polarity, migration, and even exocrine vesicle secretion.47 DIA1 mutations have been associated with deafness, cancer, and mental retardation.47 Mutations in formins like DIA1 have also been implicated in cancer metastasis due to the loosening of cellular adhesion. Expression levels of DIA1 have correlated with the stage and metastasis of cancer cells.210

Intracellular mediators of the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway

Phospholipase C (PLC)

PLC is activated by G protein due to Wnt ligand binding in the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway.52,53 The PLC family contains 13 different members with various functions and different structures. Although these members usually have little amino acid sequence homology, they have conserved EF-hand domains, PH domains, and C2 domains.211 They also all have catalytic X and Y domains.211 The PH domain is located towards the N-terminus and mediates the recruitment of PLC to the plasma membrane via binding to PIP2.212 The EF-hand motifs are part of the catalytic core of PLC along with X, Y, and C2 213. The EF-hand motif undergoes a conformational change upon binding of Ca2+ to PLC, revealing binding sites for other ligands.214 The X and Y domains form a triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) barrel-like structure composed of alternating α- and β-pleated sheets.213 The X domain contains all the catalytic residues, while the Y domain is important in modulating the preference of PLC for PIP2, as well as two other ligands PIP and PI.215 The C2 domains are formed from an eight-stranded β-pleated sandwich.213 Upon Ca2+ binding, C2 domains can mediate PLC binding to phospholipids to mediate signal transduction and membrane trafficking.216 Hokin et al used P32 to detect how phospholipid levels changed during enzyme secretion in pancreas slices with the addition of acetylcholine or carbamylcholine. They discovered that phospholipid activity increased five-to nine-fold.217

Unbeknownst to them at the time, the enzyme responsible for the increased phospholipid level was PLC.214 PLC cleaves PIP2 into IP3, which can then induce the intracellular release of Ca2+.218 PLC can be activated by a wide variety of receptors, such as B-cell receptors, T-cell receptors, Fc receptors, tyrosine kinase receptors, and G-protein coupled receptors. Due to the variety of receptors, this means that PLC can be activated by a wide variety of ligands, such as neurotransmitters, hormones, and histamine.214 Aside from IP3, the other product of PIP2 cleavage is DAG, which serves as a secondary messenger to activate Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C (PKC) to phosphorylate numerous downstream effectors and activate a wide array of cellular functions, such as cell polarization, proliferation, as well as learning and memory.219,220 Through Ca2+ release, PLC can regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, motility, gene expression, and other functions.214

Protein kinase C (PKC)

PKC is a family of protein kinases involved in a wide variety of diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease.221 There have been 518 protein kinase genes identified.222 PKC, in particular, phosphorylates Ser and Thr residues.221 PKC is activated by DAG, but can also be activated by phorbol esters, which are tumor promoters that mimic the action of DAG.221,223 Specifically, DAG and phorbol esters bind to the C1 domain on PKC, which contains a cysteine-rich sequence that resembles a DNA-binding zinc finger domain.224 PKC contains a regulatory region in the N-terminal half and a catalytic region in the C-terminal half. The C1 and C2 domains are located in the regulatory region and bind to the catalytic region, inhibiting its activity.221 The catalytic kinase region contains C3 and C4 domains.221 An important aspect of PKC is that, upon activation, it translocates to various cellular locations, joining with specific anchoring proteins at each site of action.225 With phorbol esters that irreversibly activate PKC isoenzymes in a nonselective manner, PKC was discovered to regulate many cellular functions.221 Some of these include cell proliferation, cell death, regulation of ion channels and receptors, cell-to-cell contact, and increasing gene transcription.221 However, this early work using phorbol esters does not reflect the effects of DAG due to the irreversibility of phorbol ester binding. The lack of selectivity of phorbol esters also means that they cannot identify the function of each PKC isoenzyme.221 Isoenzyme-specific inhibitors are still under development and undergoing trials, but this endeavor has proven to be difficult.221,223

Cdc42 protein

Cdc42 is a member of the Rho family of small GTPases with roles in actin cytoskeleton regulation, cell motility, cell polarity, and cell cycle progression among other functions.226 Cdc42 was characterized in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a species of yeast, with G25K being its mammalian and human homolog.227,228 Cdc42 has a P-loop, two switch regions (switch I and switch II), a polybasic region at the C-terminus, and a CAAX box for posttranslational geranylgeranylation.226 Cdc42 has been found in distinct pools in the Golgi apparatus, ER, and plasma membrane.229,230 The Golgi pool functions in three ways; it serves as a reservoir of Cdc42, functions independently from the plasma membrane pool to control protein transport from the Golgi apparatus, and coordinates with the pool to dictate cell polarity.231 Cdc42 modulates the Golgi-to-ER transport via actin regulation.232 The plasma membrane pool serves to regulate cell polarity via actin cytoskeletal rearrangement.233 At the ER, Cdc42 is necessary for tubule fission during ER remodeling.234 The activation of Cdc42 is regulated by GEFs, but unlike other Rho GTPases, Cdc42 is a hydrolase that can hydrolyze the GTP to GDP in the presence of GAP, even though GAP normally exchanges GDP for GTP.235,236 GDI inhibits Cdc42 like other Rho GTPases, via preventing GDP/GTP exchange.174 However, GDI also functions as a chaperone, delivering Cdc42 to its proper location and preventing its degradation.230 Cdc42 is currently under investigation as a therapeutic target for the treatment of cancer, although there are few Cdc42 mutations and no driver mutations that have been linked to cancer.226

Ca2+/calmodulin (CAM)-dependent kinase II (CAMKII)

CAMKII is a Ser/Thr protein kinase237 that was first characterized as a Ca2+-dependent regulator by Schulman and Greengard in 1978.238 There are over 80 known CAMKs.222 CAMKII is encoded by four different genes (α, β, γ, δ) in eukaryotes.239 CAMKII monomers form 12 subunit holoenzymes, with a C-terminal association domain that brings the N-terminal catalytic kinase domains together to fold into two rings of six subunits each.237,239 There is a regulatory segment that follows the kinase domain and is joined to a linker region that then connects to the association domain.237,240 The regulatory domain forms an α-helix to block the catalytic domain of each subunit.237 Additionally, the T286 phosphorylation site is sequestered in a hydrophobic groove, preventing autophosphorylation that would up-regulate CAMKII activity. Upon Ca2+/CAM binding to the regulatory domain, the regulatory segment is removed, enabling progressive autophosphorylation of the T286 site and increasing CAMKII activity.237 Normally, in the autoinhibited (compact) state, CAM cannot bind237,240,241; it is only when the compact state is in equilibrium with the non-autoinhibited (extended) state that CAM can bind the regulatory domain.237

Between the four CAMKII genes found in humans, the enzymes produced share 95% of their amino acid sequences in the kinase domains and 80% homology in the hub domains, with the linker region being the primary variable component.240 When two adjacent subunits are activated by Ca2+/CAM, they can phosphorylate one another on Thr286, causing increased Ca2+-independent activity.240

CAMKII has a role in adaptive contractive response during aerobic exercise.242 It is also involved in glucose production, cell cycle progression, and vascular smooth muscle function.243 Continuous activation of CAMKII can cause cardiac myocyte apoptosis, heart failure, and cardiac arrhythmia.244 CAMKII has also been identified as being able to spread the inflammatory response caused by damage to heart muscle.243 The progression of cardiomyopathy and even Chagas disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi is mediated by CAMKII signaling.243,245

TGF-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1)

TAK1 is a member of the MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK) family. It is a Ser/Thr kinase that was originally discovered to be a mediator of BMP and TGF-β signaling.246,247 TAK1 can be activated by many cytokines, such as TNF-α, TGF-β, TLRs, and IL-1 248,249. TAK1 activation causes the phosphorylation of TAK1, which leads to the activation of NF-kB, JNK, ERK, p38, and MAPKs.248,249 TAK1 is also involved in T- and B-cell signaling,248 as well as angiogenesis during embryonic development.249 Due to its role in immune and inflammatory processes, TAK1 has been implicated in multiple cancers, such as lymphoma and neuroblastoma, as well as colon, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers.250 In addition, a blockade of TAK1 leads to p53 up-regulation, indicating the importance of TAK1 in controlling cellular stresses.251 Activation of TAK1 requires three proteins, TAK1-binding protein 1 (TAB1), TAB2, and TAB3. TAB1 serves as an adaptor protein located on the N-terminal kinase domain of TAK1, while TAB2 and TAB3 will only bind the C-terminal TAK-binding domain after stimulation.249 TAB1 overproduction leads to increased TAK1 activity, but TAB1 deficiency has minor downstream effects.249 TAB2 and TAB3 are not required early on in TAK1 activation but are required for sustained TAK1 activation.249 In mice, TAK1 has been demonstrated to be a regulator of TNF signaling in the skin and modulates skin inflammation. It was found that a lack of TAK1 caused keratinocyte death due to absent NF-kB and JNK-mediated cell survival signaling.252 Recently, a selective TAK1 inhibitor called Takinib has been developed; it is activated by ATP and competitively inhibits TAK1 by binding to its ATP-binding pocket.253 Another TAK1 inhibitor called piperidylmethyloxychalcone (PMOC) also functions in the same manner.254

Nemo-like kinase (NLK)

NLK is a conserved Ser/Thr MAPK.255 It is the mammalian homolog of the Drosophila nemo gene, which was identified in Drosophila as important for the rotation of photoreceptor clusters in eye morphogenesis.256 NLK has a longer N-terminal region that is rich in histidine, proline, alanine, and glutamine.257 NLK can phosphorylate TCF4 to prevent the β-catenin/TCF complex from binding to DNA and initiating gene transcription. TAK1 can also stimulate NLK to phosphorylate TCF4, so NLK functions as a downstream effector of TAK1 in the repression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.58 Although TAK1 and NLK can repress canonical Wnt signaling, CAMKII from the noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway activates TAK1 in order to do so, indicating crosstalk between the two pathways.57 Furthermore, TAB2 can serve as a scaffold for TAK1 and NLK, enabling cooperative interaction for the inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling.258 NLK can also associate with NLK-associated RING finger protein (NARF), which is an E3 ubiquitin ligase whose action is up-regulated by NLK kinase activity.259 NARF can ubiquitinate TCF/LEF for degradation by the proteasome.259 NLK is involved in other pathways as well, such as Notch signaling and STAT protein signaling.259 Due to the function of NLK in Wnt signaling and other pathways, it is crucial in regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and other functions.259 For instance, NLK was found to inhibit the growth and migration of non-small cell lung cancer by restoring the expression of E-cadherin, which normally suppresses migration and invasion.260 However, analysis of colorectal cancer (CRC) cells found that NLK activity was increased, and only half of the CRC cells were apoptotic compared to non-CRC cells, indicating that NLK may have an anti-apoptotic function.261 NLK has also been identified as a pathological effector in mouse hearts, leading to progression toward heart failure and other cardiac conditions.262 This makes NLK a potential therapeutic target for various diseases.

Calcineurin (CaN)

CaN is a conserved Ser/Thr phosphatase that is activated by increased intracellular Ca2+ 263. It was first discovered by Wang and Desai in 1976 as a protein that counteracted the activation of bovine brain cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase.264 CaN is a heterodimer consisting of calcineurin A (the catalytic subunit) and calcineurin B (the regulatory subunit).265 The catalytic domain of calcineurin A is towards the N-terminal end, while the C-terminus contains three regulatory domains, the calcineurin B binding domain, the calmodulin-binding domain, and the autoinhibitory domain that binds to the active site when Ca2+/calmodulin is absent.265 Calcineurin B contains four Ca2+ binding EF-hand motifs.265 The mechanism of calcineurin B activation is still unknown.266 It is also structurally homologous to CAM.263 CaN along with CAM binds to Ca2+, then CAM binds CaN. This complex is what forms the active phosphatase.263 Although there are multiple CAM-modulated kinases, CaN is the only phosphatase that is directly activated by Ca2+ 263. CaN is best known for regulating the transcription of IL-2, dephosphorylating the transcription factor NF-ATp in response to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ via T cell receptor activation, and stimulating NF-ATp. CaN also controls cellular Ca2+ sequestration and cytokinesis.266 The immunosuppressive drugs FK506 and cyclosporin A can both target CaN and were key to identifying its functions.266 CaN is also important in the regulation of neurotransmitter release in neuromuscular junctions (NMJs).267 Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy have both been linked to CaN overactivation.268

Antagonists and inhibitory regulators of Wnt signaling

Extracellular antagonists of Wnt signaling

Secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRPs)

The largest family of secreted Wnt inhibitors are the sFRPs, which are structurally like the CRD ligand-binding domain of the Fz receptors.269 The first sFRP discovered was the Frizzled motif associated with bone development (Frzb).270 The sFRPs are about 295–346 amino acids long, with a CRD at the N-terminus.269 These CRDs share 30%–50% sequence similarity with the CRDs of Fz receptors, with 10 cysteine residues linked by disulfide bridges. The C-terminus has a netrin-related motif (NTR) that functions as a heparin-binding domain.271 Studies of Xenopus embryos revealed that Frzb binds to Wnt1 and Wnt8, sequestering them away from the Fz and LRP5/6 receptor complex.272, 273, 274 sFRPs can also form a nonfunctional complex with Fz receptors to prevent Wnt binding and signaling.275,276 Both the CRD and NTR domains are important in Wnt inhibition.277 The CRD domain binds to Wnt,273 while the NTR domain mimics the function of the entire sFRP1 to bind to Wnt ligands and inhibit Wnt signaling.278

Wnt-inhibitory factor 1 (WIF-1)

WIF-1 was first identified as an expressed sequence tag in the human retina279 found in fish, amphibians, and mammals.279 It contains a 150 amino acid long N-terminal signal sequence called the WIF domain, five epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats, and a 45 amino acid hydrophilic domain at the carboxy-terminus.279 The complete WIF-1 protein is 379 amino acids long.279 Analysis of Xenopus embryo assays found that WIF-1 binds Wnt8, while in Drosophila clone-8 cells, WIF-1 binds Wg, although not as strongly as with Wnt8.279 WIF-1 inhibits the binding of Wnt8 to Dfz2, blocking Wnt signaling.279

Dickkopf (Dkk) proteins

The Dickkopf (Dkk) proteins contain four members in vertebrates (Dkk1-4). Dkk1 was the first protein of its family to be discovered through experiments determining its importance in embryonic head formation and as a Wnt antagonist.280 The Dkk proteins are glycoproteins composed of 255–350 amino acids.281 Interestingly, although the Dkks all have a signal sequence and two conserved CRDs, there is little sequence similarity between them otherwise.280 Dkks primarily modulate the canonical Wnt signaling pathway via binding to the LRP5/6 co-receptor. Dkk1 associates with one of two single-pass transmembrane proteins called Kremen 1 or 2 (Krm1 or Krm2) while binding to LRP5/6. This interaction allows the endocytosis of the LRP5/6 receptor.19,281 Analysis of Dkk1 in cardiogenesis suggests that Dkk1 can activate JNK, indicating that Dkk1 may be involved in the noncanonical Wnt/PCP pathway as well.282

Wise and sclerostin (SOST) proteins

Wise and SOST are both members of a subfamily of cysteine knot proteins as they both contain cysteine knot motifs.283 Both Wise and SOST are also BMP antagonists.283,284 Wise protein is composed of 206 amino acids with 38% sequence homology with sclerostin.284 Wise is expressed in a wide variety of tissues, including branchial arches, rat endometrium, developing testes, and more.285 The sclerostin polypeptide is about 190 amino acids long with a cysteine knot formed from its flexible N- and C-terminal regions.286 Sclerostin is expressed in osteocytes to regulate bone formation. Deletions in the SOST gene that codes for sclerostin can result in van Buchem disease, which is characterized by a high bone mass due to loss of inhibition of bone formation.286 Reporter assays demonstrate that Wise can block Wnt1, Wnt3a, and Wnt10b.285 Wise also binds to the LRP6 coreceptor, preventing the binding of Wnt8.284 Additionally, Wise can function intracellularly to prevent LRP6 trafficking to the cell surface.287 Wise can also bind LRP4 to inhibit Wnt signaling.288 Sclerostin binds LRP5/6, specifically binding to LRP5 at the YWTD-EGF repeat domains, inhibiting Wnt signaling.289,290

Cerberus

Cerberus is an abundant organizer-specific gene that was isolated from Xenopus and can induce ectopic head formation.291 It also plays an important role in cardiogenesis during vertebrate embryonic development.292 Cerberus, like Wise and SOST, is in the cysteine knot superfamily.293,294 Long-form Cerberus (xCer-L) binds to Wnt8 and could inhibit Wnt signaling, but short-form Cerberus (xCer-S) cannot do the same.294 Further study is required to better understand the effects of Cerberus on the Wnt pathway.

IGFBP-4

IGFBP-4 is a member of the insulin-like growth-factor-binding proteins (IGFBPs) that bind and modulate insulin-like growth factors (IGFs). IGFBP-4 is important in cardiomyogenesis in vitro.295 IGFBP-4 interacts with LRP6 and Fz8, functioning as a competitive inhibitor of Wnt3a binding.295 In this manner, IGFBP-4 inhibits the canonical Wnt pathway.295,296 Furthermore, there are six IGFBP members. Although IGFBP-4 is the most powerful Wnt inhibitor, IGFBP-1, -2, and -6 also have Wnt inhibitor activity, albeit modestly. On the other hand, IGFBP-3 and -5 have no Wnt inhibition activity.295 Although some cancer cell lines in vitro saw a decrease in cell proliferation when treated with IGFBP-4, decreased levels of the protein increased the risk of breast cancer, and overexpression of IGFBP-4 caused prostate cancer growth in vivo.295

Intracellular negative regulators of Wnt signaling

Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)

APC is a tumor suppressor gene that is heavily associated with colorectal cancer (CRC).297 The APC protein is 2843 amino acids long,297 with a central region spanning about 1000 amino acids containing motifs that bind β-catenin or Axin.22 In humans, APC contains four 15-mers and seven 20-mers. The 20-mer repeats are phosphorylated by GSK-3β and CK1, enhancing the affinity of APC for β-catenin.22 Interspersed with the 20-mer repeats are three Ser-Ala-Met-Pro (SAMP) repeats that bind to Axin.298,299 Full-length APC or APC with SAMP repeats was found to protect β-catenin from dephosphorylation by PP2A, ensuring the destruction of β-catenin.299 The N-terminus of APC has a dimeric coiled-coil domain, with a heptad-repeat region that is crucial for the dimerization of APC.300 APC also contains an armadillo repeat domain (APC-arm) that enables APC to regulate the actin cytoskeleton and microtubules during cell polarization and migration.301,302 The C-terminal region of APC binds several proteins, such as microtubulin, indicating its role in microtubule assembly.303 APC mutation is best known for causing familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), a disease characterized by a family history of colorectal polyps and cancer. FAP is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner via a germline mutation.304

Axin proteins

Axin is a scaffold protein that was initially discovered as a protein product of the mouse Fused (Fu) gene, inhibiting Wnt signaling and regulating embryonic axis formation.305 There are two Axin homologs in eukaryotic organisms, Axin1 and Axin2, which are often collectively referred to as Axin. Axin1 is vital for embryonic viability and is widely expressed, while Axin2 is limited in its distribution to certain tissues.306,307 Axin1 was identified in mice as a locust causing kinky tail phenotypes, while Axin2 was identified due to its interactions with GSK-3β and β-catenin, as well as its homology to Axin1. The N-terminus contains the RGS (regulation of G-protein signaling) domain, which binds to APC.298 It is important to note that this region is homologous to regulators of G-protein signaling, but does not actually regulate any known G-protein.298 The RGS domain binds the third SAMP repeat and is highly conserved among Axins but is not conserved in other RGS proteins.298 Axin contains a C-terminal DIX domain that enables it to form homodimers with other Axin proteins, as well as heterodimers with Dvl.308,309 This interaction via the DIX domains is how Dvl can inhibit Axin and enable transduction of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.144 In between the RGS and DIX domains are regions that allow Axin to bind to β-catenin, GSK-3β, and CK1, forming a complex that will target β-catenin for degradation.307 Axin is important in many developmental processes, including anterior–posterior axis formation, organogenesis, neuronal proliferation and differentiation, synapse formation, and several others.307 Both Axin1 and Axin2 can function as the scaffold of the β-catenin destruction complex. They share the RGS and DIX domains, as well as the Tankyrase binding domain that maintains the Axin protein's stability.306 Interestingly, Axin2 is a target of β-catenin mediated gene transcription, but not Axin1. Due to this fact, Axin2, in particular, has been of interest in cancers caused by aberrant Wnt signaling activation, which leads to high levels of Axin2 expression.306 Axins also interact with many other pathways. Its interactions with p53 are important in stimulating transcription in p53-dependent target genes, shedding light on the importance of Axin as a tumor suppressor.310 Axin1 and Axin2 both inhibit Wnt signaling and stimulate TGF-β signaling. However, TGF-β signaling can inhibit Axin1 and Axin2 expression, leading to enhanced Wnt signaling that increases chondrocyte maturation.311

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) proteins

GSK-3 is a conserved Ser/Thr kinase that was first identified in rabbit skeletal muscle.312,313 There are two forms of GSK-3 in mammals, GSK-3α and GSK-3β, which are 98% homologous in the internal kinase domain, albeit with different N-terminal regions314 and C-terminal regions.315 Defects in GSK-3α in mice caused impaired locomotion and coordination, as well as psychiatric disorders.316 GSK-3β defects, on the other hand, are embryonically lethal,317,318 indicating that GSK-3β may be more important than GSK-3α. GSK-3 inhibits glycogen synthase via phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting glycogen synthesis.319 GSK-3 is inactivated by insulin, so GSK-3 dysregulation has been implicated in type II diabetes.318 Since both Wnt and insulin signaling pathways involve GSK-3β, this suggests that there is potential crosstalk between them. AKT phosphorylates and inhibits GSK-3 320 and Wnt causes GSK-3 dislocation from the destruction complex.321 GSK-3β is rich in the brain and is involved in neurogenesis, neurotransmission, and regulation of synaptic plasticity.322 However, it has also been implicated in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease.322 GSK-3β can be inhibited by lithium, which is used as a mood stabilizer for treating bipolar disorder.323 GSK-3β also enhances apoptosis via up-regulation of p53.324 GSK-3 can also modulate inflammation downstream of TLR signaling; activation of GSK-3 leads to the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1B, and IFNy, while inhibition of GSK-3 leads to the production of anti-inflammatory IL-10.325

Casein kinase 1 (CK1)

Casein kinase 1 (CK1) is a large family of conserved Ser/Thr kinase found in eukaryotes, with seven isoforms in humans (α, γ1, γ2, γ3, δ, ε, and α-like).326 CK1 is involved in a diverse range of cellular processes, such as vesicular trafficking, DNA repair, cell proliferation, and apoptosis.327 The kinase domain is conserved, but the N- and C-terminal domains vary in length among the CK1 family members.326 The N-terminal domain of CK1 is its catalytic domain, while the C-terminal domain has been associated with an inhibitory function, as CK1 with a truncated C-terminus led to an increase in catalytic domain activity.328,329

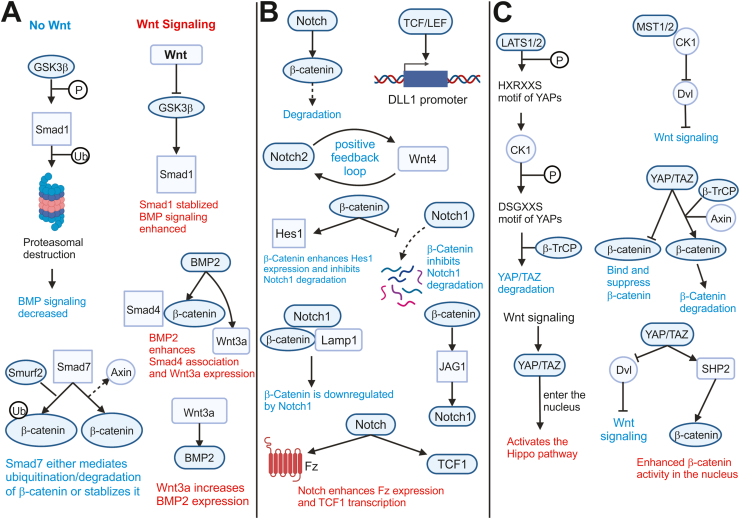

CK1 is generally considered constitutively active.330 The reason is unknown, but phosphatases have been inferred to be involved in this activity.329,330 Phosphorylation of CK1 either by itself or by other kinases inhibits its catalytic activity.330 Autophosphorylation on the C-terminus results in a phosphopeptide that binds to the catalytic domain.330 CK1 isoforms are regulated by scaffold proteins, which can sequester CK1 at several subcellular locations or bind CK1 allosterically to promote or inhibit CK1 activation.330 Although CK1 is also involved in the Hedgehog, NF-kB, and Hippo signaling pathways,326,327,330 Wnt signaling is perhaps its best-characterized process.330 CK1 phosphorylates β-catenin on Ser45, priming it for subsequent phosphorylation on Thr41, Ser37, and Ser33 by GSK-3.331 β-TrCP can then ubiquitinate β-catenin for proteasomal destruction.22,24