Abstract

Objective

This study sought to determine the serum concentrations of C-terminal telopeptide of Type-I collagen (CTx), a marker of collagen degradation, in a hospital population of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). The study also evaluated the prevalence of myocardial hyperechogenicity of the left ventricle (LV) in the same cats.

Animals and procedure

Cats brought to a university veterinary cardiology service entered the study when they had an echocardiographic diagnosis of HCM; echocardiographically normal cats served as controls. Serum CTx concentrations were assessed using ELISA.

Results

There was no difference in serum CTx concentrations between cats with HCM and controls (HCM: median 0.248 ng/mL, controls: median 0.253 ng/mL; P = 0.4). Significantly more cats with HCM (60%) showed echocardiographic LV myocardial hyperechogenicity compared to normal controls (17%; P = 0.0057), but serum CTx concentrations were not different between these 2 groups.

Conclusion and clinical relevance

These results indicate that, as in human patients with HCM and in contrast to earlier feline studies, there was no evidence of enhanced collagen degradation indicated by serum CTx concentrations in cats with HCM compared to normal controls.

Résumé

Concentration sérique de télopeptide C-terminal du collagène de Type I (CTx) et hyperéchogénicité myocardique chez des chats atteints de cardiomyopathie hypertrophique

Objectif

Le premier objectif de cette étude était d’évaluer le taux sérique d’un marqueur de dégradation de collagène, soit le télopeptide C-terminal du collagène de Type-I (CTx), chez les chats atteints de cardiomyopathie hypertrophique (CMH). Le deuxième objectif était d’évaluer la prévalence de l’hyperéchogénicité du myocarde du ventricule gauche chez ces mêmes chats.

Animaux et procédures

Les chats participant à l’étude avaient été présentés pour soins à un service de cardiologie vétérinaire universitaire, et ces chats avaient un diagnostic échocardiographique soit de CMH, soit d’aucune lésion cardiaque (groupe témoin). Le taux sérique de CTx a été évalué de façon immuno-enzymatique par ELISA.

Résultats

Les résultats n’ont démontré aucune différence entre le taux sérique de CTx chez les chats atteint de CMH et le taux sérique de CTx chez les chats sans lésion cardiaque (CMH : médiane, 0,248 ng/mL; groupe témoin : médiane, 0,253 ng/mL; P = 0,4). Plus de chats atteints de CMH (60 %) que de chats dans le groupe témoin (17 %) ont démontré une hyperéchogénicité du myocarde du ventricule gauche à l’échocardiographie (P = 0,0057), quoique les taux sériques de CTx n’étaient pas différents entre ces 2 groupes.

Conclusion et signification clinique

Ces résultats n’indiquent aucune augmentation de la dégradation de collagène chez les chats atteints de CMH, ce qui s’apparente aux résultats provenant d’études antérieures de la CMH chez l’humain mais non pas à ceux provenant d’études de la CMH féline.

(Traduit par les auteurs)

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a highly prevalent disease in the domestic cat population, and cats are a well-recognized animal model for HCM in humans (1,2). The disease process is initiated by genetic mutations in proteins of the cardiac sarcomere. Over 2000 pathologic mutations affecting at least 11 different cardiac proteins have been identified in humans with HCM; the most commonly affected proteins are beta-myosin heavy chain and myosin-binding protein C (3). In comparison, only 4 mutations, affecting genes that code for myosin-binding protein C [Maine coon (4), ragdoll (5)], betamyosin heavy chain [1 domestic shorthair (6)], and ALMS1 [sphynx (7)] have been identified in HCM in cats.

Characteristic histologic changes in feline and human HCM include myocyte hypertrophy and disarray, coronary microvascular remodeling, regional myocardial ischemia, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (1,8–13). Within the ECM, signaling pathways stimulate excessive fibroblast secretion and deposition of collagen with subsequent interstitial fibrosis (10,11). Associations between myocardial fibrosis and sudden cardiac death, ventricular arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure are important features of HCM in human patients (10,12,13).

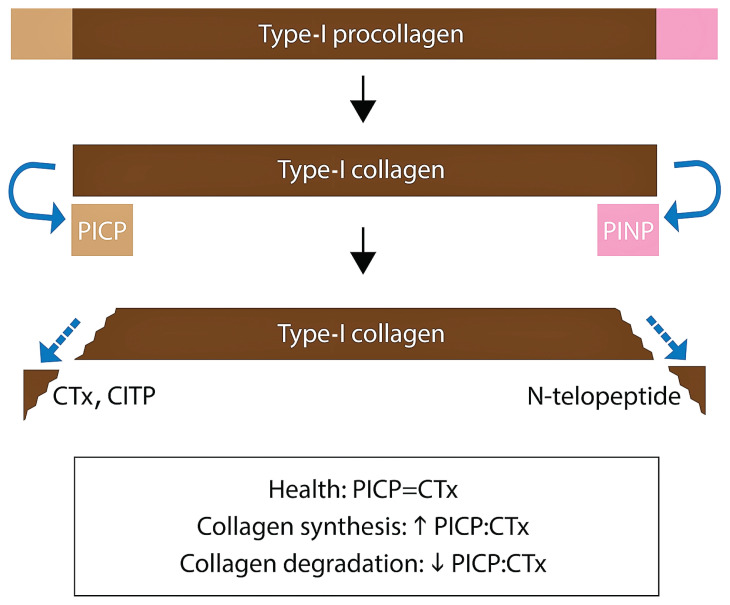

Myocardial fibrosis can be estimated clinically using indirect methods. Serum biomarkers of collagen turnover have been investigated in humans with disorders resulting in myocardial fibrosis. Both fibrillar collagen Types I and III are found in the cardiac ECM (14,15). They are synthesized as procollagens that undergo endoproteinase cleavage of propeptide extension domains before the mature collagen molecule cross-links and assembles into collagen fibers (14,15). The extension peptides are the amino (N)-terminal and carboxy (C)-terminal ends; these are released in a stoichiometric ratio to the active collagen molecule (16,17). Both are found in the vascular space, where they can be measured in serum (16–18). The C-terminal propeptide is stabilized by interchain disulfide bonds, which the N-terminal propeptide lacks. This makes the C-terminal of Type-I collagen (PICP) a reliable marker for collagen synthesis in various disease states (19,20). During collagen fiber disassembly, similar N- and C-terminal extension peptides, called telopeptides, are cleaved from collagen molecules by matrix metalloproteinases. The telopeptides consist of non-helical sequences of collagen and are measured in serum as surrogate markers of collagen degradation (21). Both the C-terminal end that includes the non-helical telopeptide and a terminal helical segment (ICTP or CITP), as well as the C-terminal end without the helical segment (CTx), are measurable in serum using commercially available ELISA methodology (21–23).

Serum concentrations of PICP (Type-I collagen synthesis) and ICTP (Type-I collagen degradation) (Figure 1) have been investigated in humans with heart disease, including HCM (24,25). Ho et al identified increased serum concentrations of PICP, increased serum PICP:ICTP, and no change in serum concentrations of ICTP in asymptomatic human patients with HCM compared to normal controls (25). The investigators concluded that the serum biomarker changes reflected a profibrotic state that could be identified before the development and clinical recognition of the disease phenotype of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) (25). Higher myocardial collagen content and interstitial myocardial fibrosis have been documented in cats with preclinical HCM compared to healthy cats, suggesting a profibrotic state plays a role in the pathogenesis of disease before onset of clinical signs (26). Biomarkers of collagen metabolism in ragdoll cats have been shown to correlate with the presence of the MYBPC3:R820W gene mutation (27). Whether biomarkers of collagen metabolism are altered in a hospital population of cats of various breeds with clinical HCM compared to healthy controls has not been reported.

Figure 1.

Extension domains of normal collagen turnover.

CITP — Carboxyterminal telopeptide of Type-I collagen including a terminal helical segment; CTx — Carboxyterminal telopeptide of Type-I collagen lacking a terminal helical segment; PICP — Carboxyterminal propeptide of Type-I procollagen; PINP — Aminoterminal propeptide of Type-I procollagen.

Echocardiography is the diagnostic test of choice for establishing a diagnosis of HCM in cats (1,2). The echogenicity (acoustic brightness) of myocardium can be altered by infiltrative diseases such as neoplasia and amyloid, or by fibrosis. An increase in echogenicity has been demonstrated in the hearts of dogs (28,29), rabbits (29), rats (30), and humans (31,32) in association with increased collagen content (fibrosis) resulting from myocardial infarction. In this context, myocardial echogenicity increases with time: infarcted myocardium can remain isoechoic for 1 wk after the onset of infarction and then become hyperechoic over the following 2 wk (30). The increase in echogenicity is associated with a change in collagen fiber morphology, with thin collagen fibers predominating initially, followed by a predominance of thick fibers later (30). Thus, myocardial hyperechogenicity is less likely to be clinically useful as a marker of acute myocardial infarction, and rather could be a marker of chronic heart disease. Such a marker could be useful in feline cardiology because the echocardiographic diagnosis of HCM can be challenging in some cats with equivocal LV measurements (2). Although fibrosis is a hallmark of feline HCM histologically (33), the presence or absence of myocardial hyperechogenicity has not been described systematically in cats with or without HCM.

We proposed to investigate whether an association could be detected between the presence of HCM and serum concentrations of a biomarker of collagen degradation (CTx) in cats presented to a veterinary teaching hospital for cardiovascular evaluation. Furthermore, we sought to assess whether a higher prevalence of cardiac LV myocardial hyperechogenicity (suggesting myocardial fibrosis, and thus, increased collagen content) could be detected echocardiographically in cats with HCM compared to normal cats; and if so, whether it was associated with serum concentrations of CTx. We hypothesized that there would be a difference in serum CTx concentrations between cats with an echocardiographic diagnosis of HCM and cats with a normal echocardiogram. We also hypothesized that the prevalence of LV myocardial hyperechogenicity would be greater in cats with HCM than in normal cats, and that cats with LV hyperechogenicity would have higher serum CTx concentrations compared to those of normal cats.

Materials and methods

Animals

The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care Committee at the Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island. Informed, signed owner consent was obtained for each cat. Cats were enrolled in the study upon presentation to the cardiology service at the Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island).

For each cat, physical examination, echocardiogram, and systemic blood pressure measurement using a Doppler unit were completed. A complete blood (cell) count (CBC), biochemical panel, and thyroxine concentration were obtained if not recently done by the primary veterinarian. Inclusion criteria included an echocardiographic diagnosis of either HCM or no structural heart disease. Reasons prompting cardiac evaluation included evaluation of an incidental murmur or arrhythmia, routine monitoring of previously diagnosed HCM, dyspnea, and breed screening. Cardiovascular exclusion criteria were an echocardiographic diagnosis of heart disease other than HCM, serum thyroxine hormone concentration above the upper limit of the reference interval (44 nmol/L) or Doppler-derived systolic arterial blood pressure > 160 mmHg. Other exclusion criteria were uncooperative behavior that prevented echocardiographic evaluation and atraumatic phlebotomy, and owner-reported clinical signs or physical examination findings consistent with any disease potentially indicating inflammation or fibrosis. These included a history of or current azotemia; a positive feline leukemia virus or feline immunodeficiency virus ELISA result; overt skeletal lesions; and clinical or laboratory findings that, in the opinion of the lead investigator (EA), could indicate inflammation. Control animals had no appreciable abnormalities on physical examination, CBCs, serum biochemical panels, or thyroxine concentrations.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was done on each cat using either a 7 MHz sector array or an 8 MHz curvilinear array probe to conduct standard 2-dimensional (2D), M-mode, color, and spectral Doppler evaluations (LOGIQ 7; GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, USA). Each echocardiogram was conducted by a veterinary cardiologist Board-certified by the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) or a cardiology resident under the direct supervision of an ACVIM Board-certified veterinary cardiologist. The diagnosis of HCM was made when ≥ 1 segments of the interventricular septum (IVS) or LV free wall (LVFW) exceeded a thickness of 5.5 mm in diastole (2). Cats were assessed as having no echocardiographic evidence of structural heart disease (and assigned to the control group) when the IVS and LVFW were uniformly < 5.5 mm in thickness; left atrial to aortic ratio (LA:Ao) was < 1.5; LV and right ventricular outflow velocities were < 2 m/s; and there was no 2D, M-mode, or Doppler evidence of structural cardiac lesions. One investigator (EC) reviewed available echocardiograms after data acquisition for all cats had been completed, blinded to echocardiographic diagnoses and serum CTx concentrations. From these images, the investigator subjectively determined whether or not LV myocardial hyperechogenicity was apparent and, when it was present, noted its distribution. Left ventricular myocardial hyperechogenicity was defined as a greater-than-expected acoustic brightness of part or all of the LV, notwithstanding the normal, expected differences in echogenicity caused by far-field enhancement and echo dropout.

Serum biomarker

Blood samples were obtained at the time of cardiac imaging by phlebotomy of the jugular or saphenous vein using a 3-milliliter syringe and 22- or 25-gauge needle. Blood was immediately transferred to an additive-free tube (Becton-Dickinson, Mississauga, Ontario) and allowed to clot at room temperature for ≤ 20 min. Samples were centrifuged (Clinical Centrifuge Model 428; International Equipment Company, Needham Heights, Massachusetts, USA) at 3000 rotations/min (1470 g) for 15 min. Following centrifugation, serum was decanted into 2-milliliter polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes in 100-microliter aliquots and stored at −80°C prior to batch analysis. Samples not immediately transferrable to the −80°C storage unit were stored at 4°C for < 12 h. Serum samples then were batch-analyzed using a commercially available ELISA for CTx (Serum CrossLaps ELISA; Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics, Herlev, Denmark) previously validated for use in cats (34).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis software (Minitab; Minitab, State College, Pennsylvania, USA and Prism; GraphPad, La Jolla, California, USA) was used for graphical evaluation of data sets and execution of statistical tests. Data sets collected for echocardiographic variables and serum concentrations of CTx were examined graphically and via the Anderson-Darling normality test. Descriptive data are reported as mean ± standard deviation and range for continuous variables with data fitting a normal distribution. Between-group comparisons of data sets fitting a normal distribution following square root transformation were done using a 2-sample t-test. Data sets for variables that failed to fit a normal distribution, including after log and square root transformation, were compared between groups using Mann-Whitney tests and reported as median [1st and 3rd quartiles (25 to 75%)]. The number of cats with LV myocardial hyperechogenicity was compared to the number of cats without LV myocardial hyperechogenicity using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance for all tests was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Fifty-six cats were initially considered for the study. Nine cats were excluded: 6 for uncooperative behavior that precluded atraumatic phlebotomy; 3 for echocardiographic diagnoses of restrictive cardiomyopathy, ventricular septal defect, and mitral valve dysplasia (each n = 1). The remaining 47 cats constituted the study population: 28 with an echocardiographic diagnosis of HCM and 19 healthy cats designated as normal controls (N group). The mean age of all enrolled cats was 7.0 ± 3.7 y (HCM: 8.1 ± 3.5 y, range: 2 to 16 y; N: 5.3 ± 3.5 y, range: 1.5 to 15 y). Cats in the HCM group were significantly older than cats in the N group (P = 0.01). There were 31 castrated males, 15 spayed females, and 1 intact female. This combined group included 29 domestic shorthair cats, 11 domestic longhair cats, 2 ragdolls, 2 Bengals, and 1 each of the following breeds: rex, Maine coon, and Russian tabby. Four of twenty-eight cats with HCM (14%) were concurrently diagnosed with congestive heart failure at the time of evaluation.

Echocardiography

By definition, the HCM group had larger IVS and LVFW measurements than the N group (both P < 0.01) (Table 1). The HCM group also had a larger LA:Ao than the N group, measured in both 2D (P < 0.01) and M-mode (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences between the HCM and N groups for measurements of LV fractional shortening (P = 0.52) or in the diameter of the LV in either systole (P = 0.28) or diastole (P = 0.25).

Table 1.

Echocardiographic measurements in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) versus normal controls (N).

| HCM (n = 28) | N (n = 19) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVSd (mm) | 5.1 (1.2) | 4.1 (0.5) | < 0.01 |

| IVSs (mm) | 7.2 (1.1) | 5.7 (0.8) | < 0.01 |

| LVIDd (mm) | 14.6 (2.8) | 15.4 (2.3) | 0.25 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 8.3 (0.2) | 9.0 (0.1) | 0.28 |

| LVFWd (mm) | 5.8 (1.4) | 4.3 (0.6) | < 0.01 |

| LVFWs (mm) | 7.7 (1.5) | 5.9 (0.7) | < 0.01 |

| FS (%) | 42.6 (8.5) | 41.0 (8.4) | 0.52 |

| IVSLax1 (mm) | 5.1 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.5) | < 0.01 |

| IVSLax2 (mm) | 6.3 (5.4 to 6.8) | 3.9 (3.5 to 4.5) | < 0.01 |

| LVFWLax (mm) | 6.8 (1.0) | 4.2 (0.5) | < 0.01 |

| IVSSax1 (mm) | 5.8 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.5) | < 0.01 |

| IVSSax2 (mm) | 5.9 (0.8) | 4.0 (0.5) | < 0.01 |

| LVFWSax (mm) | 6.5 (0.9) | 4.1 (0.6) | < 0.01 |

| LA:Ao (2D) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.8) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 0.0005 |

| LA:Ao (M-mode) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.8) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 0.0001 |

Values are reported as means (standard deviation) for normally distributed results and as medians (25th to 75th percentiles) for non-normally distributed results. FS — Fractional shortening; IVSd — Interventricular septal thickness in diastole, M-mode; IVSLax1 — Basal interventricular septal thickness in diastole as viewed in long axis, 2D; IVSLax2 — Mid-interventricular septal thickness in diastole as viewed in long axis, 2D; IVSs — Interventricular septal thickness in systole, M-mode; IVSSax1 — Left interventricular septal thickness in diastole as viewed in short axis at the papillary muscle level, 2D; IVSSax2 — Right interventricular septal thickness in diastole as viewed in short axis at the papillary muscle level, 2D; LA:Ao — Left atrial to aortic ratio; LVFWd — Left ventricular free wall thickness in diastole, M-mode; LVFWs — Left ventricular free wall thickness in systole, M-mode; LVFWLax — Basal left ventricular free wall thickness in diastole as viewed in long axis, 2D; LVFWSax — Basal left ventricular free wall thickness in systole as viewed in short axis, 2D; LVIDd — Left ventricular internal diameter in diastole, M-mode; LVIDs — Left ventricular internal diameter in systole, M-mode.

Echocardiograms were available for post-hoc review in 43 cats. Left ventricular myocardial hyperechogenicity was apparent in 18 cats: 15/25 cats with HCM (60%) and 3/18 cats in the N group (17%) (P = 0.0057) (Figure 2). The LV myocardial hyperechogenicity affected the papillary muscles (n = 5), interpapillary muscle or peripapillary muscle segments of the LV free wall (n = 6), or both (n = 2); the interventricular septum (n = 4); the LV free wall diffusely (n = 1); or the left ventricle diffusely (n = 4) (total > 18 because, in some cats, > 1 region of the LV was hyperechoic).

Figure 2.

Examples of left ventricular (LV) myocardial hyperechogenicity. Right parasternal short-axis views, mid-ventricular level. A — Well-circumscribed increase in echogenicity (arrows) affecting the LV, between the papillary muscles, extending from the subendocardium through most of the thickness of the LV free wall. B — Increase in echogenicity of both papillary muscles (asterisks) beyond the expected increase that occurs normally from far-field enhancement (see Video S1, available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net). C — Increase in echogenicity (arrows) of much of the LV free wall, predominantly affecting the subendocardial region (see Video S2, available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net).

Serum biomarker

The median serum concentration of CTx in the HCM group was 0.248 (25 to 75%, 0.146 to 0.483) ng/mL. The median serum concentration of CTx in the N group was 0.253 (25 to 75%, 0.184 to 0.56) ng/mL. There was no difference in serum CTx concentration between groups (P = 0.4).

The median serum concentration of CTx in cats with LV myocardial hyperechogenicity was 0.253 (25 to 75%, 0.183 to 0.492) ng/mL. The median serum concentration of CTx in cats without LV myocardial hyperechogenicity was 0.253 (25 to 75%, 0.14 to 0.556) ng/mL. There was no difference in serum CTx concentration between groups (P = 0.93).

Discussion

The lack of a significant difference in serum CTx concentration in cats with HCM and cats with normal echocardiograms offers no support for excessive collagen degradation in cats with HCM. This finding refuted the first hypothesis of the study. Similarly, in human HCM patients, Ho et al reported no difference in the concentrations of ICTP between HCM mutation carriers with and without phenotypic expression of LVH (25). In those patients, the higher PICP:ICTP ratio, a reflection of the balance between collagen synthesis and degradation, implied excessive collagen synthesis rather than altered collagen degradation. The results of the present study support investigating whether this situation also exists in cats with HCM.

The lack of difference in serum CTx concentration between cats with HCM and normal controls contrasts with the findings of Borgeat et al, which showed that mutation-positive ragdoll cats had higher serum concentration of CITP than did mutation-negative normal controls (27). Without a marker for Type-I collagen synthesis in that study, it is not clear if that finding occurred due to greater collagen degradation or a change in overall collagen metabolism in mutation carriers. The results of the present study did not document a different serum concentration between affected and healthy cats. Various explanations may account for this difference. First, Type-I collagen degradation could be more common in early stages of HCM, then slow after the development of LVH. If so, then the mutation carriers in the study from Borgeat et al who had not developed LVH would be expected to have higher CITP concentrations than would the cats with LVH. A second possible explanation for the difference between results of the present study and those of Borgeat et al is statistical underpowering of the present study. This seems less likely, as the present study involved 28 cats with HCM and no statistically significant difference in CTx concentration in these cats compared to controls, whereas the Borgeat et al study involved 25 cats with HCM with a significant difference reported compared to controls. Third, CITP and CTx are closely-related but distinct C-terminal telopeptide byproducts of Type-I collagen degradation (Figure 1), and a difference in the kinetics of their formation, or in assay performance, could explain the difference in results between the present study and that of Borgeat et al. A final possible explanation for the differences in results between studies is population composition. The study by Borgeat et al exclusively enrolled ragdoll cats in which the genetic mutation could be evaluated, whereas the present study included cats from 7 different breeds without genetic evaluation. Feline breed- or mutation-specific alterations in collagen metabolism have not been reported but could contribute to differences between these 2 studies. Additionally, affected cats in the present study were significantly older than normal controls, whereas the mutation carriers in the study from Borgeat et al were not different in age from normal controls. If collagen degradation is influenced by age, this might explain the discordant results in serum CTx concentrations between studies. DeLaurier et al reported that urine and serum CTx concentrations were inversely correlated with age in healthy cats; cats < 1 y of age had significantly higher CTx concentrations than did cats > 1 y of age (34,35). As CTx is not specific for myocardial collagen degradation, this was thought to reflect more rapid bone metabolism in growing animals, which stabilized with skeletal maturity.

The higher prevalence of LV myocardial hyperechogenicity in cats with HCM compared to controls supported the second hypothesis of this study. Increased LV myocardial echogenicity has been described subjectively in individual cats and is a well-known association with HCM (36), but is not routinely included in detailed descriptions of echocardiographic findings in cats with HCM (2). The significant difference in the present study between the prevalence of LV myocardial hyperechogenicity in HCM (60%) cats compared to cats in the N group (17%) suggests that evidence of myocardial fibrosis could be detectable echocardiographically in cats with HCM. The heterogeneity of phenotypic manifestations of HCM in cats means that having an additional echocardiographic finding associated with it, such as myocardial hyperechogenicity, could increase the suspicion of HCM when other data do not provide a clear answer. The presence of LV myocardial hyperechogenicity affecting the papillary muscles in 13/18 cats (72%) is consistent with these structures being the farthest removed of any part of the LV from a coronary arterial supply that is located epicardially, and thus, possibly at greater risk of ischemia in HCM. Although confirmation of fibrosis would require histopathologic evaluation of myocardium, measurements of serum CTx concentrations could have been a surrogate for assessing this variable. However, in this study population, no association was determined. The lack of a difference in serum CTx concentrations between cats with and those without LV myocardial hyperechogenicity refuted the third hypothesis of this study. Possible explanations for this result could include an alternative cause of such hyperechogenicity or poor assay performance.

This study had limitations that present areas warranting future investigation. First, entry criteria included a conservative cutoff for LV mural dimensions, which could cause Type 1 error by including cats in the HCM group that did not have HCM. Second, although the review of echocardiograms was done with the investigator unaware of the group assignment of each cat, echocardiographic images could be suggestive of HCM (or its absence) and thus could influence the investigator, despite blinding. Third, myocardial hyperechogenicity was assessed subjectively; in future studies, backscatter measurements could be used for a quantitative assessment of this finding (29,31), and interobserver variability could be investigated.

In conclusion, in this study — and in contrast to previous work in cats, but consistent with that in humans — cats with HCM did not have significantly different serum CTx concentrations than normal control cats. Left ventricular myocardial hyperechogenicity was more prevalent in cats with HCM than in normal controls. Serum CTx concentrations were not associated with LV myocardial hyperechogenicity. Evaluation of myocardial fibrosis in cats remains a worthwhile pursuit, particularly as evidence mounts that the presence and extent of myocardial fibrosis are negative prognostic indicators in humans with HCM.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ptarmigan Foundation, the Saleh Laboratory and the Atlantic Veterinary College Research Fund, and funds from the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Resident Research Grant (Cardiology).

This manuscript represents a portion of a thesis submitted by Dr. Anderson to the Atlantic Veterinary College Department of Companion Animals as partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Science degree.

Preliminary results were presented in abstract form at the Forum of the American Veterinary College of Internal Medicine, Seattle, Washington, June 2013.

The authors thank Monique Saleh, Allan MacKenzie, Ashley Patriquen, and Elaine Reveler for technical assistance. CVJ

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from the Ptarmigan Foundation, the Saleh Laboratory and the Atlantic Veterinary College Research Fund, and funds from the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Resident Research Grant (Cardiology).

Footnotes

Unpublished supplementary material (Videos S1, S2) is available online from: www.canadianveterinarians.net

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (kgray@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Kittleson MD, Meurs KM, Munro MJ, et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Maine coon cats: An animal model of human disease. Circulation. 1999;99:3172–3180. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payne JR, Brodbelt DC, Luis Fuentes V. Cardiomyopathy prevalence in 780 apparently healthy cats in rehoming centres (the CatScan study) J Vet Cardiol. 2015;17:S244–S257. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BA, Wang RS, Carnethon MR, et al. What causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? Am J Cardiol. 2022;179:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meurs KM, Sanchez X, David RM, et al. A cardiac myosin binding protein C mutation in the Maine coon cat with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3587–3593. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meurs KM, Norgard MM, Ederer MM, et al. A substitution mutation in the myosin binding protein C gene in ragdoll hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genomics. 2007;90:261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schipper T, Van Poucke M, Sonck L, et al. A feline orthologue of the human MYH7 c.5647G>A (p.(Glu1883Lys)) variant causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a domestic shorthair cat. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27:1724–1730. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0431-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meurs KM, Williams BG, DeProspero D, et al. A deleterious mutation in the ALMS1 gene in a naturally occurring model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the sphynx cat. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:108. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01740-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu SK, Maron BJ, Tilley LP. Feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Gross anatomic and quantitative histologic features. Am J Pathol. 1981;102:388–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St John Sutton MG, Lie JT, Anderson KR, O’Brien PC, Frye RL. Histopathological specificity of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: Myocardial fibre disarray and myocardial fibrosis. Br Heart J. 1980;44:433–443. doi: 10.1136/hrt.44.4.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Factor SM, Butany J, Sole MJ, et al. Pathologic fibrosis and matrix connective tissue in the subaortic myocardium of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1982;17:1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka M, Fujiwara H, Onodera T, et al. Quantitative analysis of myocardial fibrosis in normals, hypertensive hearts, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Br Heart J. 1986;55:575–581. doi: 10.1136/hrt.55.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diez J, Laviades C, Monreal I, et al. Toward the biochemical assessment of myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive patients. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:14D–17D. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80486-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Querejeta R, Varo N, Lopez B, et al. Serum carboxy-terminal propeptide of procollagen type I is a marker of myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive heart disease. Circulation. 2000;101:1729–1735. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen MJ. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism in animals: Uses and limitations. Vet Clin Pathol. 2003;32:101–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165x.2003.tb00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Risteli J, Niemi S, Kauppila S, et al. Collagen propeptides as indicators of collagen assembly. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;266:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taubman MB, Golderg B, Sherr CJ. Radioimmunoassay for human procollagen. Science. 1974;186:1115–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4169.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melkko J, Niemi S, Risteli L, et al. Radioimmunoassay of the carboxyterminal propeptide of human type I procollagen. Clin Chem. 1990;36:1328–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delmas PD. Biochemical markers of bone turnover. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;266:176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koivula MK, Ruotsalainen V, Björkman M, et al. Difference between total and intact assays for N-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen reflects degradation of pN-collagen rather than denaturation of intact propeptide. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47:67–71. doi: 10.1258/acb.2009.009110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebeling PR, Peterson JM, Riggs BL. Utility of type I procollagen propeptide assays for assessing abnormalities in metabolic bone diseases. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650071118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chubb SA. Measurement of C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTx) in serum. Clin Biochem. 2012;45:928–935. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pederson BJ, Bond M. Purification of human procollagen type I carboxyl-terminal propeptide cleaved as in vivo from procollagen and used to calibrate a radioimmunoassay of the propeptide. Clin Chem. 1994;40:811–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cristgau S, Rosenquist C, Alexandersen P, et al. Clinical evaluation of the Serum CrossLaps One Step ELISA, a new assay measuring the serum concentration of bone-derived degradation products of type I collagen C-telopeptides. Clin Chem. 1998;44:2290–2300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fassbach M, Schwartzkopff B. Elevated serum markers for collagen synthesis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and diastolic dysfunction. Z Kardiol. 2005;94:328–35. doi: 10.1007/s00392-005-0214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho CY, Lopez B, Coelho-Filho OR, et al. Myocardial fibrosis as an early manifestation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:552–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohr KH, Campbell FE, Owen H, et al. Myocardial collagen deposition and inflammatory cell infiltration in cats with pre-clinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Vet J. 2015;203:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgeat K, Dudhia J, Luis Fuentes V, Connolly DJ. Circulating concentrations of a marker of type I collagen metabolism are associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation status in ragdoll cats. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:360–365. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skorton DJ, Melton HE, Jr, Pandian NJ, et al. Detection of acute myocardial infarction in closed-chest dogs by analysis of regional two-dimensional echocardiographic gray-level distributions. Circ Res. 1983;52:36–44. doi: 10.1161/01.res.52.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mimbs JW, O’Donnell MA, Bauwens DA, et al. The dependence of ultrasonic attenuation and backscatter on collagen content in dog and rabbit hearts. Circ Res. 1980;47:49–58. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabel GM, Whittaker P, Vlachonassios K, Sonawala M, Chandraratna PA. Collagen fiber morphology determines echogenicity of myocardial scar: Implications for image interpretation. Echocardiography. 2006;23:103–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vered Z, Mohr GA, Barzilai B, et al. Ultrasound integrated backscatter tissue characterization of remote myocardial infarction in human subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:84–91. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picano E, Pelosi G, Marzilli M, et al. In vivo quantitative ultrasonic evaluation of myocardial fibrosis in humans. Circulation. 1990;81:58–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novo Matos J, Garcia-Canadilla P, Simcock IC, et al. Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) for the assessment of myocardial disarray, fibrosis and ventricular mass in a feline model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20169. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76809-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLaurier A, Jackson B, Pfeiffer D, Ingham K, Horton MA, Price JS. A comparison of methods for measuring serum and urinary markers of bone metabolism in cats. Res Vet Sci. 2004;77:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeLaurier A, Jackson B, Ingham K, Pfeiffer D, Horton MA, Price JS. Biochemical markers of bone turnover in the domestic cat: Relationships with age and feline osteoclastic resorptive lesions. J Nutr. 2002;132:1742S–1744S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.6.1742S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kittleson MD, Côté E. The feline cardiomyopathies: 2. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Feline Med Surg. 2021;23:1028–1051. doi: 10.1177/1098612X211020162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]