Fractures are a frequent cause of morbidity in older people and some result from a minor impact that would not damage normal bone. These are called fragility fractures and typically involve the wrist, hip, spine, or shoulder. In 2019 to 2020 the annual rate of hip fracture among Canadians aged 65 to 79 years was 169 per 100,000; for those 80 years or older the rate was 1038 per 100,000.1

In May 2023 the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) published a new guideline on screening for primary prevention of fragility fractures.2 It states:

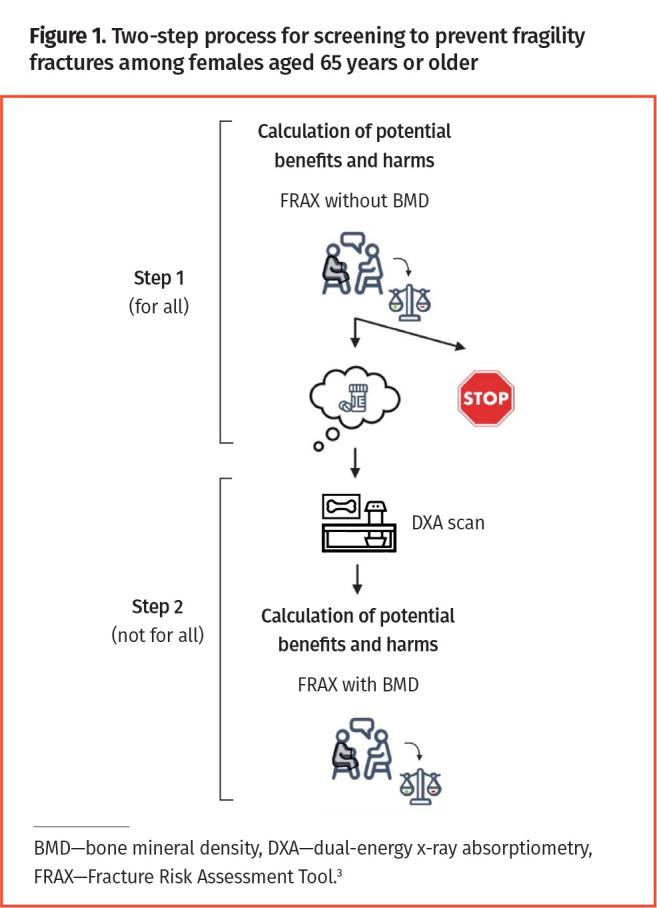

We recommend “risk assessment–first” screening for prevention of fragility fractures in females aged 65 years and older, with initial application of the Canadian clinical Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) without bone mineral density (BMD). The FRAX result should be used to facilitate shared decision-making about the possible benefits and harms of preventive pharmacotherapy. After this discussion, if preventive pharmacotherapy is being considered, clinicians should request BMD measurement using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry … of the femoral neck, and re-estimate fracture risk by adding the BMD T-score into FRAX (conditional recommendation, low-certainty evidence).2

This 2-step process using FRAX is summarized in Figure 1.3

Figure 1.

Two-step process for screening to prevent fragility fractures among females aged 65 years or older

Variability in patient preferences for preventive treatment led the CTFPHC to suggest clinicians engage in shared decision making on this topic. In the Prevention in Practice series in Canadian Family Physician, we have previously outlined how to implement shared decision making in the context of preventive health care.4-6

The CTFPHC guideline does not recommend screening for fragility fractures in females younger than 65 years or in males of any age. Although the guideline provides recommendations on screening for and prevention of fragility fractures through pharmacotherapy, the CTFPHC is not ignoring other risk factors. In particular, a separate guideline on fall prevention is under development.

Case description

Patricia, age 58, visits your clinic. You know each other well and benefit from a trusting relationship. Patricia is a White female who takes no medication, has never smoked, has never had a fragility fracture, and is now postmenopausal. She politely asks if it is time for a BMD test of her bones, as some of her friends have been diagnosed with and treated for osteoporosis. Is she like them?

Screening for osteoporosis among female patients aged 50 to 64 years is common in Canada, with data from 2018 to 2019 showing that about one-quarter had undergone at least 1 BMD test.7 Osteoporosis refers to a bone density of 2.5 standard deviations or more below the mean of a “normal” person, meaning the bone density of a healthy young adult at 30 years of age.8 However, the utility of labelling people as being osteoporotic when their bone density drops to an arbitrary level (such as 2.5 standard deviations or more) below the mean is unclear, given how multiple other factors (eg, body weight, age) contribute to the personal risk of fragility fracture. In a cohort of White persons 60 years or older, the relationship between BMD and fracture risk was found to be continuous.9 This finding underscores the point that when we assess a patient, we should incorporate BMD as a continuous variable in fracture risk assessment, rather than classifying patients arbitrarily using terms such as high risk or low risk based on BMD cut-off values.9 We should also understand that BMD improves risk assessment only marginally in comparison with other FRAX predictors.10,11

Appropriateness of routine tests

In 2020 the Prevention in Practice team wrote about the need for changes to clinical preventive care—for example, what testing to resume postpandemic or not, and why.12 In 2023 we think it is timely to return to the following question: are we giving enough thought to the appropriateness of so-called routine tests? Such testing can direct attention away from matters of greater importance to patient health. Others have also called for caution regarding low-value testing, identifying frequent repeat BMD testing as a prime example of this problem in Canadian primary care.13

In 2023 Johansson and colleagues explained how the routine ordering of tests carries an opportunity cost for health care,14 defined as benefit from interventions of proven effectiveness forgone by particular use of resources.15 At the same time, clinicians face a barrage of guideline recommendations that, in total, are impossible to implement. For example, primary care providers in the United States would have to work 27 hours per day just to follow all relevant guidelines.16 One strategy for addressing this problem would be to consider explicitly the time needed to implement each recommended intervention. A structured approach to this, called “time needed to treat,” has been proposed.14 The goal of estimating time needed to treat is to avoid having clinicians and patients spend their limited time together on recommendations of lesser importance and to improve access to care for individuals most in need of medical attention.

Strategies for prevention of fragility fracture

Consider 2 family physicians working in community-based group practices: Dr BMD and Dr FRAX. We estimate the time required for each to screen patients up to the age of 85 for primary prevention of fragility fractures. In so doing, we address the issue of time needed to screen and, for a subset, the time needed to discuss further testing and pharmacotherapy to prevent fragility fractures.

Dr BMD follows the 2010 Osteoporosis Canada recommendation that men and postmenopausal women aged 50 to 64 years with clinical risk factors for fracture (Table 1) and all persons 65 or older should periodically undergo BMD testing.17 For Dr BMD, the time required to screen includes time to order these BMD tests, to deal with their results, and to engage in discussions with patients about preventive treatment.

Table 1.

Risk factors for clinical fragility fractures

| RISK FACTOR | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Fragility fracture after age 40 | Fragility fractures resulting from minor impact that would not damage normal bone and involving the wrist, hip, spine, or shoulder |

| Prolonged glucocorticoid use | ≥3 months’ cumulative therapy in the previous year at a prednisone-equivalent dose of ≥7.5 mg daily |

| Use of other high-risk medications | Aromatase inhibitors or androgen deprivation therapy |

| Parental hip fracture | NA |

| Vertebral fracture or osteopenia identified on radiography | NA |

| Current smoking | NA |

| High alcohol intake | ≥3 units per day |

| Low body weight | <60 kg |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | NA |

| Other disorders strongly associated with osteoporosis |

|

NA—not applicable.

Adapted with permission from Papaioannou et al.17 Copyright 2010 Joule Inc.

Dr FRAX, on the other hand, uses a risk assessment–first strategy for females 65 years or older, as recommended by the CTFPHC.2 After 1 discussion of fracture risk, Dr FRAX does not repeat the process in less than 8 years, given there is no good evidence to conduct risk assessments repeatedly in stable patients. Nevertheless, considering these are female patients 65 or older, Dr FRAX will eventually rediscuss fracture risk with many patients over the next 2 decades until they reach age 85.

Which doctor spends more time trying to prevent fragility fractures? A risk assessment–first strategy using FRAX is less demanding of clinician time than a BMD-first strategy (Figure 2).18 Based on screening trials, we know that risk assessment–first strategies are effective.19 However, we have no high-quality evidence that directly compares BMD-first versus risk assessment–first strategies in terms of fracture prevention.

Figure 2.

Clinician time required to implement screening strategies to prevent fragility fractures for a sample practice population over 25 years: Estimates assume a practice population of 1200 adult patients. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care estimated screening times based on data from a convenience survey it distributed in April 2023.

Detailed information on how the time estimates in Figure 2 were calculated are available online.18,20 Time required for a BMD-first strategy for females and males aged 50 to 64 years could not be estimated as—smoking aside—the prevalence of clinical risk factors of fracture outlined in Table 1 are unknown.17

Case resolution

Let us assume Patricia is seeing Dr FRAX. When Patricia asks about BMD testing, Dr FRAX informs her of the CTFPHC guideline recommendation against screening in her age group.2 Then, to explain this briefly, Dr FRAX uses the new decision aid mentioned in the guideline.21 At 58 years of age, 6 female patients out of 100 like Patricia will sustain a fracture in the next 10 years, 1 being a hip fracture. By taking a bisphosphonate medication for 5 years, just 1 of these female patients will avoid a fracture (not of the hip).

Given such a small probability of benefit, as well as potential adverse effects of treatment, Patricia is not interested in preventive treatment at this time. Consequently, no BMD test is ordered. As Dr FRAX provides continuity of care, they will revisit this question together after Patricia turns 65. If this reassessment were to be done when she is 68, for example, at that time approximately 10 female patients out of 100 like Patricia would each sustain a fracture over the next 10 years, 2 of them being hip fractures. At that level of fracture risk, Patricia would be willing to consider preventive treatment. Thus, a BMD test would be done and follow-up would be scheduled to re-estimate fracture risk using the T-score at the femoral neck. This information would guide Patricia’s final decision on treatment initiation.

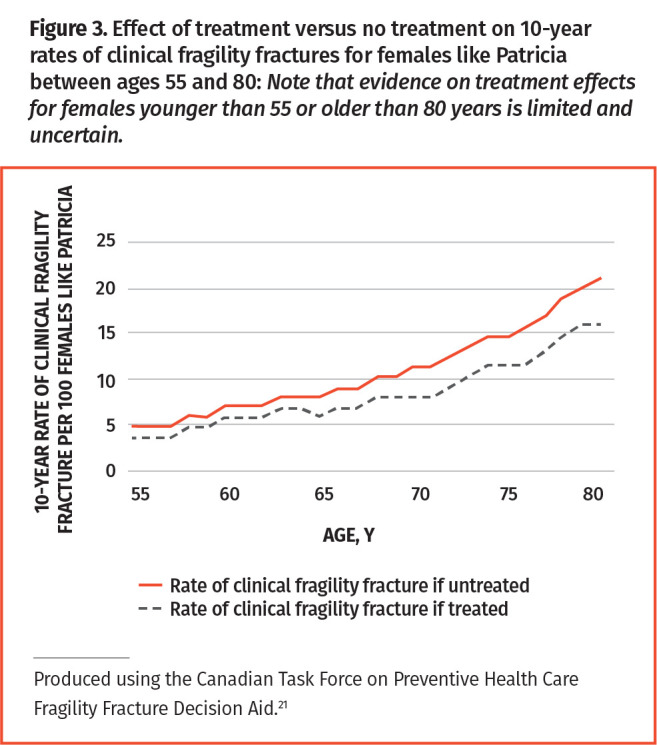

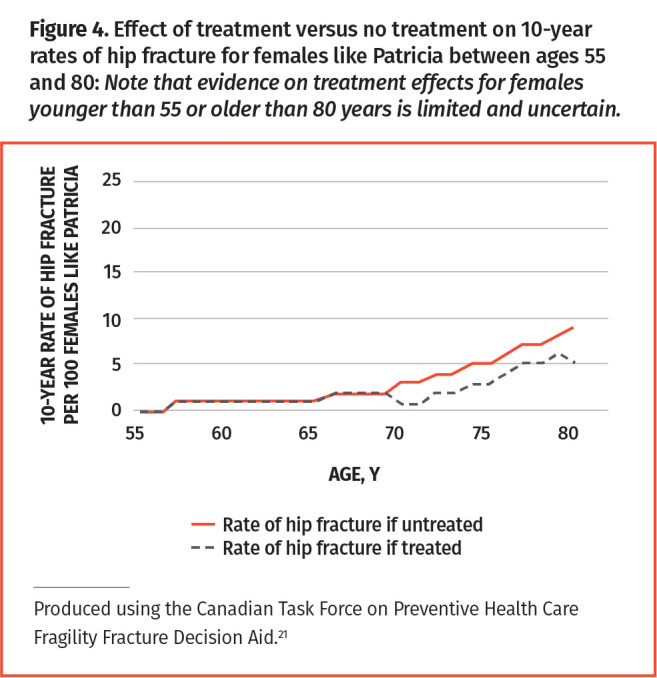

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the probability of clinical fragility fracture (also called major osteoporotic fracture) and hip fracture per 100 female patients like Patricia between the ages of 55 to 80.21 These figures also reveal the magnitude of benefit one can expect from preventive treatment. Patricia weighs 65.5 kg, her height is 170 cm, and both variables remain stable over time. She has no clinical risk factors for fragility fracture. Before age 65, Patricia can expect almost no benefit from bisphosphonate treatment in terms of preventing clinical fragility fracture. For preventing hip fracture in female patients like Patricia, benefit is possible, but only after age 70.

Figure 3.

Effect of treatment versus no treatment on 10-year rates of clinical fragility fractures for females like Patricia between ages 55 and 80: Note that evidence on treatment effects for females younger than 55 or older than 80 years is limited and uncertain.

Figure 4.

Effect of treatment versus no treatment on 10-year rates of hip fracture for females like Patricia between ages 55 and 80: Note that evidence on treatment effects for females younger than 55 or older than 80 years is limited and uncertain.

In our clinical scenario, Patricia raised the question of BMD testing. As such, Dr FRAX elicited her preference for preventive treatment in a patient-centred way. Using a decision aid, they were able to come to an understanding of what can be accomplished in terms of preventing fragility fractures. At age 58, Patricia decided against BMD testing as the benefit of preventive treatment was close to 0 (and harms were present). After patients are 65 years old, adopting a risk assessment–first strategy makes sense both for doctors and for their patients. First, the time saved through this strategy can be used to address issues of greatest importance to patients. Second, a risk assessment–first strategy will avoid labelling female patients as having osteoporosis, which may paradoxically lower quality of life and lead some to reduce their physical activity.22,23

Conclusion

At the population level, screening 1000 Canadian females after age 65 using a risk assessment–first strategy is expected to prevent 4 hip fractures and 12 clinical fragility fractures over 3 to 5 years of follow-up.19 Thus, if you have 250 females aged 65 to 85 in your practice, screening them at least once via a risk assessment–first strategy could prevent 1 hip fracture and 3 clinical fragility fractures.

Key points

▸ When screening females aged 65 years or older for prevention of fragility fractures, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) recommends a “risk assessment–first” strategy based on the Canadian clinical Fracture Risk Assessment Tool.

▸ The CTFPHC recommends against screening females aged 40 to 64 years or males of any age.

▸ If implemented, these CTFPHC recommendations should lead to less bone mineral density testing, which may help redirect health care resources to matters of greater value to patients.

▸ A risk assessment–first strategy can promote shared decision making more effectively between patients and providers and will also require less clinician time.

Suggested reading

Johansson M, Guyatt G, Montori V. Guidelines should consider clinicians’ time needed to treat. BMJ 2023;380:e072953.

Thériault G, Limburg H, Klarenbach S, Reynolds DL, Riva JJ, Thombs BD, et al. Recommendations on screening for primary prevention of fragility fractures. CMAJ 2023;195(18):E639-49.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to https://www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à https://www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’août 2023 à la page e165.

References

- 1.Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System . Summary table: osteoporosis-related fracture—hip (annual), crude rate, per 100,000, 2019-2020 (fiscal year), Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2021. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/ccdss/data-tool/Age?G=00&V=20&M=3. Accessed 2023 Jun 30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thériault G, Limburg H, Klarenbach S, Reynolds DL, Riva JJ, Thombs BD, et al. . Recommendations on screening for primary prevention of fragility fractures. CMAJ 2023;195(18):E639-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases . Fracture risk assessment tool: calculation tool [Canada]. Sheffield, UK: University of Sheffield; 2019. Available from: https://frax.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=19. Accessed 2023 Jun 30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grad R, Légaré F, Bell NR, Dickinson JA, Singh H, Moore AE, et al. . Shared decision making in preventive health care. What it is; what it is not. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:682-4 (Eng), e377-80 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang E, Bell NR, Dickinson JA, Grad R, Kasperavicius D, Moore AE, et al. . Eliciting patient values and preferences to inform shared decision making in preventive screening. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:28-31 (Eng), e13-6 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thériault G, Grad R, Dickinson JA, Breault P, Singh H, Bell NR, et al. . To share or not to share. When is shared decision making the best option? Can Fam Physician 2020;66:327-31 (Eng), e149-54 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System . Summary table: osteoporosis-related fracture care gap—bone mineral density (BMD) test, crude prevalence, percent who received a BMD test, 2018-2019 (fiscal year), Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2021. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/ccdss/data-tool/Age. Accessed 2023 Jul 3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy . Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 285(6):785-95.11176917 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mai HT, Tran TS, Ho-Le TP, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV.. Two-thirds of all fractures are not attributable to osteoporosis and advancing age: implications for fracture prevention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104(8):3514-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhiman P, Andersen S, Vestergaard P, Masud T, Qureshi N.. Does bone mineral density improve the predictive accuracy of fracture risk assessment? A prospective cohort study in northern Denmark. BMJ Open 2018;8(4):e018898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey E, Kanis JA, et al. . Independent clinical validation of a Canadian FRAX tool: fracture prediction and model calibration. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25(11):2350-8. Erratum in: J Bone Miner Res 2017;32(11):2319. Epub 2017 Oct 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson JA, Thériault G, Singh H, Szafran O, Grad R.. Rethinking screening during and after COVID-19. Should things ever be the same again? Can Fam Physician 2020;66:571-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendrith C, Bhatia M, Ivers NM, Mecredy G, Tu K, Hawker GA, et al. . Frequency of and variation in low-value care in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open 2017;5(1):E45-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson M, Guyatt G, Montori V.. Guidelines should consider clinicians’ time needed to treat. BMJ 2023;380:e072953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer S, Raftery J.. Economics notes: opportunity cost. BMJ 1999;318(7197):1551-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter J, Boyd C, Skandari MR, Laiteerapong N.. Revisiting the time needed to provide adult primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2023;38(1):147-55. Epub 2022 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, et al. . 2010 Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ 2010;182(17):1864-73. Epub 2010 Oct 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Screening to prevent fragility fractures. How much time does it take? Montréal, QC: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2023. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/CTFPHC_FF_ClinicianCommunication_Tool_v15_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 2023 May 29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gates M, Pillay J, Nuspl M, Wingert A, Vandermeer B, Hartling L.. Screening for the primary prevention of fragility fractures among adults aged 40 years and older in primary care: systematic reviews of the effects and acceptability of screening and treatment, and the accuracy of risk prediction tools. Syst Rev 2023;12(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.How was this calculation made? Montréal, QC: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2023. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/how-was-this-calculation-made/. Accessed 2023 May 9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fragility fracture decision aid. Montréal, QC: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2023. Available from: https://frax.canadiantaskforce.ca/. Accessed 2023 May 21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reventlow SD. Perceived risk of osteoporosis: restricted physical activities? Qualitative interview study with women in their sixties. Scand J Prim Health Care 2007;25(3):160-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao S, Zhao Y.. Quality of life in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 2023;32(6):1551-65. Epub 2022 Nov 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]