Abstract

Background

Osteoporosis is a known, modifiable risk factor for lower extremity periprosthetic fractures. Unfortunately, a high percentage of patients at risk of osteoporosis who undergo THA or TKA do not receive routine screening and treatment for osteoporosis, but there is insufficient information determining the proportion of patients undergoing THA and TKA who should be screened and their implant-related complications.

Questions/purposes

(1) What proportion of patients in a large database who underwent THA or TKA met the criteria for osteoporosis screening? (2) What proportion of these patients received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) study before arthroplasty? (3) What was the 5-year cumulative incidence of fragility fracture or periprosthetic fracture after arthroplasty of those at high risk compared with those at low risk of osteoporosis?

Methods

Between January 2010 and October 2021, 710,097 and 1,353,218 patients who underwent THA and TKA, respectively, were captured in the Mariner dataset of the PearlDiver database. We used this dataset because it longitudinally tracks patients across a variety of insurance providers throughout the United States to provide generalizable data. Patients at least 50 years old with at least 2 years of follow-up were included, and patients with a diagnosis of malignancy and fracture-indicated total joint arthroplasty were excluded. Based on this initial criterion, 60% (425,005) of THAs and 66% (897,664) of TKAs were eligible. A further 11% (44,739) of THAs and 11% (102,463) of TKAs were excluded because of a prior diagnosis of or treatment for osteoporosis, leaving 54% (380,266) of THAs and 59% (795,201) of TKAs for analysis. Patients at high risk of osteoporosis were filtered using demographic and comorbidity information provided by the database and defined by national guidelines. The proportion of patients at high risk of osteoporosis who underwent osteoporosis screening via DEXA scan within 3 years was observed, and the 5-year cumulative incidence of periprosthetic fractures and fragility fracture was compared between the high-risk and low-risk cohorts.

Results

In total, 53% (201,450) and 55% (439,982) of patients who underwent THA and TKA, respectively, were considered at high risk of osteoporosis. Of these patients, 12% (24,898 of 201,450) and 13% (57,022 of 439,982) of patients who underwent THA and TKA, respectively, received a preoperative DEXA scan. Within 5 years, patients at high risk of osteoporosis undergoing THA and TKA had a higher cumulative incidence of fragility fractures (THA: HR 2.1 [95% CI 1.9 to 2.2]; TKA: HR 1.8 [95% CI 1.7 to 1.9]) and periprosthetic fractures (THA: HR 1.7 [95% CI 1.5 to 1.8]; TKA: HR 1.6 [95% CI 1.4 to 1.7]) than those at low risk (p < 0.001 for all).

Conclusion

We attribute the higher rates of fragility and periprosthetic fractures in those at high risk compared with those at low risk to an occult diagnosis of osteoporosis. Hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons can help reduce the incidence and burden of these osteoporosis-related complications by initiating screening and subsequently referring patients to bone health specialists for treatment. Future studies might investigate the proportion of osteoporosis in patients at high risk of having the condition, develop and evaluate practical bone health screening and treatment algorithms for hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons, and observe the cost-effectiveness of implementing these algorithms.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Fragility fractures caused by osteoporosis carry high morbidity, mortality, and economic burden [8, 10, 26]. In patients undergoing lower extremity arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, the prevalence of osteoporosis is approximately 26% [20], two times higher than the age-adjusted prevalence of osteoporosis in the general population of adults 50 years and older [12]. Patients with osteoporosis undergoing total joint arthroplasty are at increased risk of having not only fragility fractures but also periprosthetic fractures [21]. Treatments for osteoporosis [13] and intraoperative prophylactic techniques, such as cementation [19], have been shown to be advantageous in preventing bone health–related complications.

However, as in the general population, recommended osteoporosis screening rates using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning in patients at high risk of osteoporosis is believed to be low. In a single-institution study of 200 patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA), 59% met the criteria for DEXA testing but only 17% had a DEXA screening in the 2 years before surgery [7]. In a similar study of 505 patients undergoing TJA who were identified as having a high risk of osteoporosis, these rates have been shown to be even higher; 88% did not receive routine bone mineral density screening and 90% did not receive any pharmacologic treatment [27]. These studies, however, are limited by their use of single-institution data that cannot be extrapolated on a national level. To our knowledge, no studies have compared the incidence of fragility fractures and periprosthetic fractures in patients who are considered at high risk of osteoporosis to those who are considered at low risk among patients who were not diagnosed or treated for osteoporosis. Understanding the percentage of patients who should be screened and their risks after lower extremity arthroplasty on a national scale may display an opportunity for hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons to intervene.

We therefore asked: (1) What proportion of patients in a large database who underwent THA or TKA met the criteria for osteoporosis screening? (2) What proportion of these patients received a DEXA study before arthroplasty? (3) What was the 5-year cumulative incidence of fragility fracture or periprosthetic fracture after arthroplasty of those at high risk compared with those at low risk of osteoporosis?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective, comparative, large-database analysis using the PearlDiver Patient Records Database (www.pearldiverinc.com). The Mariner dataset of the database was used, which contains the all-payer claims information of more than 151 million patients from January 2010 to October 2021. Unlike other administrative claims databases, the Mariner dataset uses unique patient identifiers that are not limited to changes in insurance status, permitting longitudinal follow-up and minimizing loss to follow-up. This database was used for this study because its large sample of patients across various insurance providers throughout United States permits more generalizable results to the United States population than single-institution data can provide. Additionally, the use of these unique patient identifiers permits the observation of complications after an intervention, with a maximum of 10-year follow-up based on the years of the data accessible.

Patients

Between January 2010 and October 2021, 2,063,315 patients were captured in the Mariner dataset because they underwent THA (710,097) or TKA (1,353,218). Patients were identified based on Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes. We considered patients at least 50 years old who underwent elective TJA to be eligible. To identify elective TJA, patients with a diagnosis of malignancy and those who underwent TJA indicated for a fracture were identified via International Classification of Disease (ICD) billing codes and excluded (Supplemental Table 1; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B159). Based on this initial criterion, 72% (514,128 of 710,097) of the THAs and 80% (1,084,378 of 1,353,218) of the TKAs were eligible. Additionally, only patients with a minimum study follow-up of 2 years were included, excluding an additional 17% (89,123 of 514,128) of THAs and 17% of TKAs (186,714 of 1,084,378) because of loss to follow-up or incomplete datasets. Of these 425,005 THAs and 897,664 TKAs, an additional 11% (44,739) of THAs and 11% (102,463) of TKAs, were excluded because of a prior diagnosis of or treatment for osteoporosis (Supplemental Table 1; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B159). In total, 380,266 THAs and 795,201 TKAs were included in this study. The median follow-up for THA was 6.2 years (IQR 4.1 to 8.6) and that for TKA was 6.5 years (IQR 4.7 to 8.9).

Study Groups

Patients were stratified into two study groups based on the risk of osteoporosis at the time of surgery: those considered to be at low risk and those considered to be at high risk of osteoporosis. Patients were risk stratified using the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and Endocrinology Society guidelines for men and postmenopausal women [11, 28]. Based on these guidelines, patients were considered high risk if they were a woman at least 65 years old, a man at least 70 years old, or a patient of either gender who was at least 50 years old with known non‐age‐related risk factors for osteoporosis. These risk factors included tobacco use, alcohol abuse or dependence, being underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), having a prior fragility fracture, using chronic systemic corticosteroids, or having metabolic or genetic conditions affecting sex hormones (such as hypogonadism) or bone mineral density (such as osteogenesis imperfecta) [11, 28]. Prior published works have used these ICD diagnosis codes, CPT codes, and drug data provided by the PearlDiver database to define these high-risk patient populations [2, 22-24, 30]. Thus, we used these same codes to define our high-risk categories (Supplemental Table 1; http://links.lww.com/CORR/B159). Patients were considered at high risk of osteoporosis if they met at least one high-risk criterion defined above.

Primary and Secondary Study Outcomes

Our primary study goal was to observe the proportion of patients without a prior diagnosis of or treatment for osteoporosis undergoing TJA who were at high risk of osteoporosis. To achieve this, we determined the percentage of patients who met at least one high-risk criterion. We subsequently conducted a subanalysis of the percentage of patients in the different high-risk categories defined above. Our secondary study goal was to determine the proportion of these patients considered at high risk of osteoporosis who underwent preoperative bone health screening. To achieve this goal, we first observed the number and percentage of patients considered at high risk of osteoporosis who underwent screening via DEXA scan (CPT codes 77080, 77081, 77085, and 77086) within 3 years before TJA. The Endocrinology Society guidelines recommend bone mineral density screening every 2 years in patients at high risk of osteoporosis [11, 28]. We used a 3-year preoperative period to capture as many patients as possible. We conducted a subanalysis using the same high-risk categories discussed above to see differences in the current use of osteoporosis screening based on these different high-risk categories. Our final goal was to compare the 5-year cumulative incidence rates of fragility fractures and periprosthetic fractures between those at high risk and those without any high-risk criteria (low risk). Periprosthetic fractures only included low-energy fractures around the implant; by contrast, fragility fractures included nonperiprosthetic fractures of the hip, pelvis, spine, humerus, and wrist that were not caused by high-energy trauma. To include fractures caused by low-energy trauma only, we excluded all events that were likely to have been caused by high-energy events (such as a motor vehicle collision) at the same time these fractures occurred. This methodology of defining fragility fractures using ICD diagnosis codes was based on published works [1, 25].

Ethical Approval

The utilization of the PearlDiver database for this study was approved by our local institutional review board.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis for demographics and the proportion of patients screened. The number of patients in each category and their respective percentage among the population of interest were recorded. The 5-year cumulative incidence among those at high risk and those at low risk of osteoporosis was performed using a Kaplan-Meier analysis. Kaplan-Meier analysis permits the estimation of survival by censoring patients with the observed outcome, those who are lost to follow-up, and those with missing values by using the number at risk. For periprosthetic fractures, the number at risk decreased to 57,068 for THA and 129,187 for TKA. For fragility fractures, the number at risk decreased to 56,624 for THA and 128,000 for TKA. The loss of patients owing to death was small, because the mortality rate was 0.1% (171 of 1,175,467) for TJA. Because of this, a Kaplan-Meier analysis, rather than a competing events analysis, was justified to calculate the cumulative incidence rate [16, 29].

We used a Cox proportional hazard model to test for differences in the cumulative incidence rates, assuming that proportional hazards were checked in each analysis. For the risk of periprosthetic fracture and fragility fracture, the Schoenfeld residuals did not show a pattern of changing residuals for the predictor variable of those at high risk for THA (periprosthetic fractures = 0.512; fragility fracture = 0.649) and TKA (periprosthetic fractures = 0.628; fragility fracture = 0.732). This implies that the groups did not diverge at any point within 5 years. Thus, time-varying models were not required, and only one HR was calculated for each analysis. The resulting output was recorded as the HRs, 95% CIs, and p value. A p value less than 0.05 was used as the significance level for this study. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) provided by the PearlDiver database.

Results

Proportion of Patients at High Risk of Osteoporosis Who Underwent TJA

In total, 53% (201,450 of 380,266) and 55% (439,982 of 795,201) of patients who underwent THA and TKA, respectively, were at high risk of osteoporosis (Table 1). Among the 380,266 patients who underwent THA, 30% (115,203) were women older than 65 years, 17% (66,099) were men older than 70 years, and 4% (13,269) had a high-risk metabolic or genetic condition affecting sex hormones or bone mineral density condition: 3% (10,598) used tobacco products, 1% (4757) had a prior fragility fracture, 1% (3678) were underweight, 1% (2622) used steroids chronically, and 0.2% (861) had alcohol abuse or dependence (Table 1). Of the 795,201 patients who underwent TKA, 34% (267,742) were women older than 65 years, 17% (137,140) were men older than 70 years, and 3% (23,945) had a high-risk metabolic or genetic condition: 2% (18,202) used tobacco products, 1% (9786) had a prior fragility fracture, 1% (7332) were underweight, 1% (5279) used steroids chronically, and 0.2% (1344) had alcohol abuse or dependence (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline parameters and high-risk categories of patients undergoing THA and TKA

| Category | THA (N = 380,266) | TKA (N = 795,201) |

| Age group in years | ||

| 50-59 | 22 (85,393) | 19 (151,013) |

| 60-69 | 40 (148,248) | 41 (324,604) |

| 70-74 | 17 (63,820) | 19 (149,403) |

| 75 + | 22 (82,805) | 21 (170,181) |

| Women | 51 (195,694) | 58 (460,528) |

| Any high risk | 53 (201,450) | 55 (439,982) |

| Women 65 years and older | 30 (115,203) | 34 (267,742) |

| Men 70 years and older | 17 (66,099) | 17 (137,140) |

| Metabolic or genetic conditions | 3.5 (13,269) | 3.0 (23,945) |

| Tobacco product use | 2.8 (10,598) | 2.2 (18,202) |

| Prior fragility fracture | 1.3 (4757) | 1.2 (9786) |

| Underweight | 1.0 (3678) | 0.9 (7332) |

| Chronic steroid use | 0.7 (2622) | 0.7 (5279) |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 0.2 (861) | 0.2 (1344) |

Data are presented as % (n). International Classification of Diseases, Current Procedure Terminology, and drug codes were used to determine each high-risk category.

Prevalence of Osteoporosis Screening in Patients at High Risk of Osteoporosis

Of patients at high risk of osteoporosis, 12% (24,898 of 201,450) of those who underwent THA and 13% (57,022 of 439,982) of those who underwent TKA were screened via DEXA 3 years before surgery (Table 2). For THA, those who used steroids chronically were the most-screened (27% [715 of 2622]), followed by women 65 years and older (20% [22,787 of 115,203]), those who were underweight (14% [503 of 3678]), those who used tobacco products (8.2% [874 of 10,598]), those with a prior fragility fracture (7.3% [348 of 4757]), those with alcohol abuse or dependence (7.2% [62 of 861]), those with a high-risk metabolic or genetic condition (4.0% [527 of 13,269]), and men 70 years and older (2.3% [1542 of 66,099]) (Table 2). Similarly, for TKA, those who used steroids chronically were the most likely to be screened (28% [1470 of 5279]), followed by women 65 years and older (20% [53,815 of 267,742]), those who were underweight (14% [1047 of 7332]), those who used tobacco products (8.3% [1508 of 18,202]), those with a prior fragility fracture (7.8% [759 of 9786), those with alcohol abuse or dependence (5.9% [79 of 1344]), those at high risk of having a metabolic or genetic condition (3.6% [854 of 23,945]), and men 70 years and older (2.2% [3007 of 137,140]) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of DEXA testing within 3 years before THA or TKA in patients at high risk for osteoporosis

| Category | THA (N = 201,450) | TKA (N = 439,982) |

| Any high risk | 12 (24,898 of 201,450) | 13 (57,022 of 439,982) |

| Chronic steroid use | 27 (715 of 2622) | 28 (1470 of 5279) |

| Women 65 years and older | 19 (22,787 of 115,203) | 20 (53,815 of 267,742) |

| Underweight | 14 (503 of 3678) | 14 (1047 of 7332) |

| Smoker | 8.2 (874 of 10,598) | 8.3 (1508 of 18,201) |

| Prior fragility fracture | 7.3 (348 of 4757) | 7.8 (759 of 18,202) |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 7.2 (62 of 861) | 5.9 (79 of 1344) |

| Metabolic conditions | 4.0 (527 of 13,269) | 3.6 (854 of 23,945) |

| Men 70 years and older | 2.3 (1542 of 66,099) | 2.2 (3007 of 137,140) |

Data are presented as % (n). International Classification of Diseases, Current Procedure Terminology, and drug definitions were used for each high-risk category.

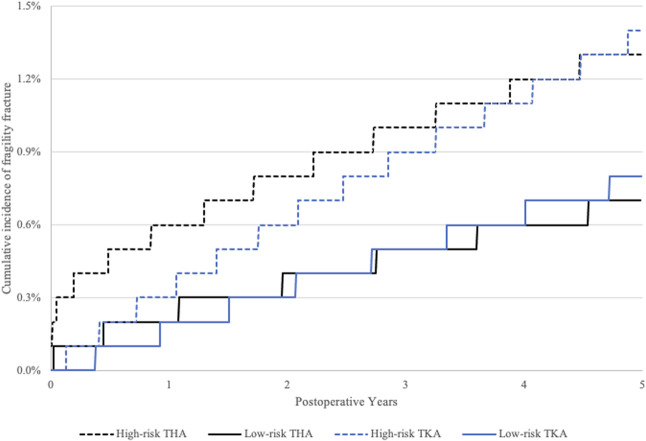

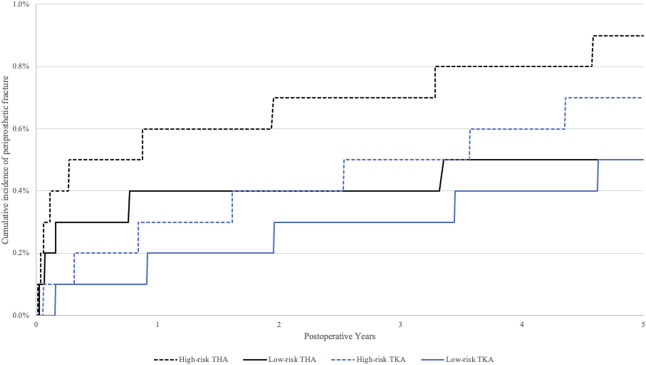

Cumulative Incidence of Fragility Fracture and Periprosthetic Fracture

The 5-year cumulative incidence rates of fragility fractures for those at high risk and low risk of osteoporosis after THA were 1.3% (95% CI 1.2% to 1.4%) and 0.7% (95% CI 0.7% to 0.8%), respectively (Fig. 1). The 5-year cumulative incidence rates for periprosthetic fractures for those at high risk and low risk of osteoporosis after THA were 0.9% (95% CI 0.8% to 0.9%) and 0.5% (95% CI 0.4% to 0.5%), respectively (Fig. 2). Patients at high risk of osteoporosis had higher risk of fragility fractures (HR 2.1 [95% CI 1.9 to 2.2]; p < 0.001) and periprosthetic fractures (HR 1.7 [95% CI 1.5 to 1.8]; p < 0.001) (Table 3) within 5 years of THA than those at low risk. The 5-year cumulative incidence rates of fragility fractures for those at high risk and low risk of osteoporosis after TKA were 1.4% (95% CI 1.4% to 1.5%) and 0.8% (95% CI 0.8% to 0.9%), respectively (Fig. 1). The 5-year cumulative incidence rates of periprosthetic fractures for those at high risk and low risk of osteoporosis after TKA were 0.7% (95% CI 0.7% to 0.8%) and 0.5% (95% CI 0.5% to 0.6%), respectively (Fig. 2). Patients at high risk of osteoporosis had a higher risk of fragility fractures (HR 1.8 [95% CI 1.7 to 1.9]; p < 0.001) and periprosthetic fractures (HR 1.6 [95% CI 1.4 to 1.7]; p < 0.001) (Table 3) within 5 years of TKA than those at low risk.

Fig. 1.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of fragility fracture after THA and TKA is shown. The high-risk group included those who met at least one endocrinology guideline criterion for osteoporosis screening. The low-risk group included those who did not meet any endocrinology guideline criteria for osteoporosis screening.

Fig. 2.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of periprosthetic fracture after THA and TKA is shown. The high-risk group included those who met at least one endocrinology guideline criterion for osteoporosis screening. The low-risk group included those who did not meet any endocrinology guideline criteria for osteoporosis screening.

Table 3.

A comparison of 5-year fracture risk between patients at high risk for osteoporosis and those at low risk

| Category | HR (95% CI) | p value |

| THA | ||

| Periprosthetic fracture | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Fragility fracture | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.2) | < 0.001 |

| TKA | ||

| Periprosthetic fracture | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.7) | < 0.001 |

| Fragility fracture | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | < 0.001 |

HRs are compared to those of patients at low risk for osteoporosis (did not meet any screening criteria). International Classification of Diseases, Current Procedure Terminology, and drug codes were used to determine each high-risk category.

Discussion

Prior studies reported that more than half of patients undergoing TJA meet at least one criterion to be screened for osteoporosis, but fewer than 20% of them undergo screening [7]. However, the use of single-institution data prevents the extrapolation of those results on a national scale. Additionally, there are no studies of which we are aware that assess the risk of fractures after TJA in patients who meet at least one criterion for osteoporosis screening compared with those who meet none. Our analysis using national data confirms that of prior studies observing that more than 50% of patients undergoing TJA met at least one criterion to be screened for osteoporosis but fewer than 15% of these patients underwent preoperative screening [7]. Additionally, these patients at high risk of osteoporosis had a higher risk of periprosthetic fractures and fragility fractures within 6 years of surgery. Because most patients undergoing elective TJA meet the national criteria for screening [7], hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons can play an important role in addressing the osteoporosis epidemic by screening patients who undergo TJA for osteoporosis and referring them to bone health specialists to reduce the higher rates of fragility fractures and periprosthetic fractures in this high-risk patient population.

Limitations

Our study used an administrative claims database and thus is limited in terms of the reliability and limited information provided by these billing codes. Regarding the high-risk criteria, the ICD codes and internal filters that were provided could address the major high-risk categories. However, certain ICD codes such as those for alcohol abuse or dependence may be underused, and thus may underrepresent that population. Additionally, there were other criteria such as radiographically confirmed osteopenia, clinical examination that identified height loss of kyphosis, cognitive ability, family history of osteoporosis, and poor vision or hearing based on assessments [11, 28] that may qualify a patient to be screened for osteoporosis. Thus, our proposed proportion of patients at high risk may be an underestimate, which tends to confirm our main message that hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons can help with screening. This also may explain the relatively high periprosthetic fracture and fragility fracture rates in the low-risk patient population. If all high-risk categories could be accounted for, we propose that the incidence of periprosthetic fracture and fragility fracture would be lower in the low-risk group, increasing the absolute risk reduction compared with the high-risk group. Additionally, although the database contains the records of more than 150 million patients, the populations are not randomly sampled and thus are limited in terms of generalizability. Regarding fractures, there are no specific ICD codes for fragility fractures. Therefore, to define fragility fractures as accurately as possible, we used published works that have used the PearlDiver Database [1, 25]. Regarding a comparison of patients at low risk versus those at high risk, we are limited in the reporting of intraoperative information; thus, the study is at risk of selection bias. Surgeons may change their intraoperative practice such as by using cementation or other intraoperative prophylactic measures if the surgeon thinks the patient is at increased risk of fracture. However, we are unable to access this information. These interventions may be more used in the high-risk patient population, and this might underestimate our findings regarding patients at low risk and those at high risk, and thus further support our rationale for surgeon-initiated osteoporosis screenings.

Proportion of Patients at High Risk of Osteoporosis Who Underwent TJA

Slightly more than half of patients who underwent elective hip or knee arthroplasty in this large-database, national study met at least one screening criteria for osteoporosis, based on well-accepted guidelines on the topic [11, 28]. This supports prior single-institution work reporting that 59% of patients undergoing TJAs met at least one criterion for screening [7]. These data are important for hip and knee surgeons when considering surgeon-initiated routine bone health screening, because they demonstrate a high demand for screening. A study of postmenopausal women 65 years and older undergoing THA assessed the prevalence of occult osteoporosis by performing preoperative screening, identifying that 25% of patients who had not undergone screening or treatment had an occult diagnosis of osteoporosis [15]. This demonstrates only one of the many high-risk categories for osteoporosis screening that were identified in this study. To better understand the larger picture and potential benefit of surgeon-initiated bone health screening, future prospective studies are needed to screen all high-risk patients discussed in this paper.

Prevalence of Osteoporosis Screening in Patients at High Risk of Osteoporosis

Only a small minority of patients—one of eight—determined to be at high risk of osteoporosis at the time of arthroplasty underwent screening for that diagnosis. This supports prior single-institution work finding that only 18% of patients determined to be at high risk of osteoporosis underwent preoperative screening [7]. In addition to the identified high proportion of patients undergoing TJA who meet at least one criterion for screening, the alarmingly low screening rates show the role surgeons can play in screening. However, the current climate places the burden of screening only on primary care providers. A survey among orthopaedic surgeons showed that surgeons believed osteoporosis screening and management is largely the responsibility of primary care providers [6], leading many to fail to initiate or discuss screening. Yet screening is not a novel concept in arthroplasty. To reduce highly morbid postoperative complications, preoperative screening for obesity, diabetes mellitus, anemia, and malnutrition has become standard of care [3-5, 9, 18]. Fragility fractures and periprosthetic fractures are a highly morbid complication that can be prevented via osteoporosis screening to risk-stratify patients and ultimately begin treatment. Because there have been no studies, to our knowledge, assessing the impact of an arthroplasty surgeon–initiated osteoporosis screening and treatment algorithm in preventing these fractures, there are no guidelines to recommend surgeon-initiated screening and treatment. Future prospective studies can define this algorithm and compare it with the standard of care to observe its efficacy in preventing fragility fractures and periprosthetic fractures.

Cumulative Incidence of Fragility Fracture and Periprosthetic Fracture

In a finding that validates our methodologic approach and provides useful information to arthroplasty surgeons, patients who were identified here as being at high risk of osteoporosis had nearly twice the cumulative incidence of fractures (periprosthetic fractures and fragility fractures) within 5 years of TJA. This suggests that arthroplasty surgeons are well-positioned to improve the overall health of their patients by engaging in the process of osteoporosis diagnosis when other preoperative medical factors are being managed in advance of elective surgery. Using the established screening criteria produced by endocrine societies [11, 17], surgeons can complement efforts by primary care physicians to initiate screening. Frameworks and algorithms have already been produced that orthopaedic surgeons can use to implement in their practice [14]. Although created to address patients who already sustained a fracture, these algorithms can be modified for those undergoing elective TJA, with our study showing the large benefit these interventions can provide on a systemic level. Nonetheless, the twofold higher risk of fracture only shows the demand for and not the efficacy of proposed interventions. Future studies are needed to observe whether these interventions are efficacious and cost-effective for implementation on a national level.

Conclusion

We attribute the higher rates of fragility and periprosthetic fractures in those at high risk than in those at low risk to an occult diagnosis of osteoporosis. Hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons can help reduce the incidence and burden of these osteoporosis-related complications by initiating screening and subsequently referring patients to bone health specialists for treatment. Because more than 50% of patients undergoing elective TJA should be screened for osteoporosis but fewer than 20% of these patients are screened, surgeon-initiated screening would have a high national impact. Future studies might investigate the proportion of osteoporosis in patients at high risk of the condition, develop and evaluate practical bone health screening and treatment algorithms for hip and knee arthroplasty surgeons, and observe the cost-effectiveness of implementing these algorithms.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

One of the authors (RS) is a consultant for Smith & Nephew and Zimmer, but no payments or benefits were received during the study period. One of the authors (GJG) is a consultant for Stryker, but no payments or benefits were received during the study period.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the George Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB# NCR213330).

This work was performed at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Washington, DC, USA.

Contributor Information

Alisa Malyavko, Email: alisamalyavko@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Alex Gu, Email: algu@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Andrew B. Harris, Email: andrewbharris@jhmi.edu.

Sandesh Rao, Email: srao875@gmail.com.

Robert Sterling, Email: rsterling@mfa.gwu.edu.

Gregory J. Golladay, Email: gregorygolladay@gmail.com.

Savyasachi C. Thakkar, Email: savyasachithakkar@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Agarwal AR, Cohen JS, Jorgensen A, Thakkar SC, Srikumaran U, Golladay GJ. Trends in anti-osteoporotic medication utilization following fragility fracture in the USA from 2011 to 2019. Osteoporos Int. 2023;34:379-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal AR, Wang KY, Xu AL, et al. Obesity does not associate with 5-year surgical complications following anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:947-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of osteoarthritis of the hip evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/osteoarthritis-of-the-hip/oa-hip-cpg_6-11-19.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2022.

- 4.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Surgical management of osteoarthritis of the knee clinical practice guideline. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/quality/quality-programs/lower-extremity-programs/surgical-management-of-osteoarthritis-of-the-knee/. Accessed December 13, 2022.

- 5.Baek SH. Identification and preoperative optimization of risk factors to prevent periprosthetic joint infection. World J Orthop. 2014;5:362-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton DW, Griffin DC, Carmouche JJ. Orthopedic surgeons’ views on the osteoporosis care gap and potential solutions: survey results. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernatz JT, Brooks AE, Squire MW, Illgen RI, 2nd, Binkley NC, Anderson PA. Osteoporosis is common and undertreated prior to total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1347-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JP, Adachi JD, Schemitsch E, et al. Mortality in older adults following a fragility fracture: real-world retrospective matched-cohort study in Ontario. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullock MW, Brown ML, Bracey DN, Langfitt MK, Shields JS, Lang JE. A bundle protocol to reduce the incidence of periprosthetic joint infections after total joint arthroplasty: a single-center experience. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:1067-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:465-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2020 update. Endocr Pract . 2020;26:1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Osteoporosis or low bone mass in older adults: United States, 2017-2018. Available at: 10.15620/CDC:103477. Accessed December 13, 2022 [DOI]

- 13.Cohen JS, Agarwal AR, Kinnard MJ, Thakkar SC, Golladay GJ. The association of postoperative osteoporosis therapy with periprosthetic fracture risk in patients undergoing arthroplasty for femoral neck fractures. J Arthroplasty. 2022;38:726-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer RP, Herbert B, Cuellar DO, et al. Osteoporosis and the orthopaedic surgeon: basic concepts for successful co-management of patients' bone health. Int Orthop. 2014;38:1731-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glowacki J, Hurwitz S, Thornhill TS, Kelly M, LeBoff MS. Osteoporosis and vitamin-D deficiency among postmenopausal women with osteoarthritis undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2371-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson AJ, Desai S, Zhang C, et al. A calcar collar is protective against early torsional/spiral periprosthetic femoral fracture: a paired cadaveric biomechanical analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2020;102:1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson NR, Springer B. Patient optimization strategies prior to elective total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2021;30:207-211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karachalios TS, Koutalos AA, Komnos GA. Total hip arthroplasty in patients with osteoporosis. Hip Int. 2020;30:370-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labuda A, Papaioannou A, Pritchard J, Kennedy C, DeBeer J, Adachi JD. Prevalence of osteoporosis in osteoarthritic patients undergoing total hip or total knee arthroplasty. Arch Phys Med Rehabil . 2008;89:2373-2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsland D, Mears SC. A review of periprosthetic femoral fractures associated with total hip arthroplasty. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2012;3:107-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng MK, Lam A, Diamond K, et al. What are the causes, costs and risk-factors for emergency department visits following primary total hip arthroplasty? An analysis of 1,018,772 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rebello E, Albright JA, Testa EJ, Alsoof D, Daniels AH, Arcand M. The use of prescription testosterone is associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing a distal biceps tendon injury and subsequently requiring surgical repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1254-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roecker Z, Kamalapathy P, Werner BC. Male sex, cartilage surgery, tobacco use, and opioid disorders are associated with an increased risk of infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2022;38:948-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross BJ, Lee OC, Harris MB, Dowd TC, Savoie FH, 3rd, Sherman WF. Rates of osteoporosis management and secondary preventative treatment after primary fragility fractures. JB JS Open Access. 2021;6:e20.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veronese N, Kolk H, Maggi S. Epidemiology of fragility fractures and social impact. In: Falaschi P, Marsh D, eds. Orthogeriatrics: The Management of Older Patients with Fragility Fractures. 2nd ed. Springer; 2020:19-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Levin JE, Amen TB, Arzani A, Manzi JE, Lane JM. Total joint arthroplasty and osteoporosis: looking beyond the joint to bone health. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:1719-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wongworawat MD, Dobbs MB, Gebhardt MC, et al. Editorial: estimating survivorship in the face of competing risks. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:1173-1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao AY, Agarwal AR, Harris AB, Cohen JS, Golladay GJ, Thakkar SC. The association of prior fragility fractures on 8-year periprosthetic fracture risk following total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. Published online February 22, 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.arth.2023.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.