Abstract

目的

联合使用网络药理学和分子对接技术探究姜黄素作用于牙周炎的治疗靶点。

方法

采用多种数据库预测姜黄素、牙周炎的作用靶点,利用String绘制姜黄素-牙周炎蛋白质相互作用(PPI)网络,筛选出的关键靶基因进行基因本体论(GO)和京都基因与基因组百科全书(KEGG)分析;通过分子对接技术分析姜黄素治疗牙周炎的关键靶点。

结果

从数据库中获得672个牙周炎相关疾病靶点,107个姜黄素作用靶点,筛选获得20个关键靶点,对这20个靶点进行GO和KEGG通路富集分析发现,姜黄素可能通过调节低氧诱导因子(HIF)-1、甲状旁腺激素(PTH)等信号通路发挥治疗作用;分子对接分析结果表明,姜黄素和多个靶点均具有良好的结合潜能。

结论

本研究获得姜黄素治疗牙周炎的潜在靶点及分子机制,对促进药物的研发及临床应用提供理论基础。

Keywords: 姜黄素, 牙周炎, 网络药理学, 分子对接, 作用机制

Abstract

Objective

This study aims to explore the therapeutic targets of curcumin in periodontitis through network pharmacology and molecular docking technology.

Methods

Targets of curcumin and periodontitis were predicted by different databases, and the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network constructed by String revealed the interaction between curcumin and periodontitis. The key target genes were screened for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses. Molecular docking was performed to analyze the binding potential of curcumin to periodontitis.

Results

A total of 672 periodontitis-related disease targets and 107 curcumin-acting targets were obtained from the databases, and 20 key targets were screened. The GO and KEGG analyses of the 20 targets showed that curcumin might play a therapeutic role through the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 and parathyroid hormone (PTH) signaling pathways. Molecular docking analysis showed that curcumin had good binding potential with multiple targets.

Conclusion

The potential key targets and molecular mechanisms of curcumin in treating periodontitis provide a theoretical basis for new drug development and clinical applications.

Keywords: curcumin, periodontitis, network pharmacology, molecular docking analysis, mechanism

牙周炎是一种发生在牙周支持组织的慢性感染性疾病[1],2017年全球疾病负担研究[2]发现,全球重度牙周炎的患病率约9.8%,影响着约7.96亿人口。菌斑微生物及其产物是牙周炎的始动因子[3],因此,机械性清除菌斑微生物,防止和减缓菌斑的再附着是目前治疗牙周炎的主要途径[1]。但机械治疗的效果受诸多因素的限制,如较深的牙周袋、根分叉、复杂的根面解剖等[4]–[5]。局部辅助使用抗菌药物,如甲硝唑、四环素等,虽可提高临床疗效,但抗菌药物的应用也可带来了口腔局部菌群耐药性的产生,扰乱正常的口腔微生物群落[6]。因此,一些天然抗菌剂,如草本植物逐渐成为研究的热点。

姜黄素是一种从东南亚热带植物姜黄中提取的黄色多酚,具有多种生物学效应[7]。多项临床试验[8]–[10]表明,姜黄素能够抑制牙周袋内牙周致病菌的数量,改善患者的牙周状况。近期的系统评价[11]也显示:姜黄素辅助牙周非手术治疗能够提高牙龈指数(gingival index,GI)、龈沟出血指数(sulcus bleeding index,SBI)等牙周临床指标;同时姜黄素作为牙周机械治疗的辅助治疗药物,和氯己定在改善牙周临床指标[牙周袋探诊深度(pocket probing depth,PPD)、临床附着丧失(clinical attachment loss,CAL)、GI和菌斑指数(plaque index,PI)]方面能达到相似的效果[12]。但是由于姜黄素的水溶性较差,机体吸收率低,降解速度快[13],导致目前姜黄素的生物利用度尚不够充分。因此,有必要探究姜黄素治疗牙周炎的精准分子靶点,从而通过药物修饰提高作用效果。本文通过网络药理学以及分子对接技术深入挖掘分子姜黄素作用于牙周炎的潜在靶点和治疗机制,以期为研究姜黄素改良制剂提供理论依据。

1. 材料和方法

1.1. 牙周炎相关疾病靶点的筛选

以“chronic periodontitis”为关键词,从数据库Genecards(http://www.genecards.org/)、DisGeNET(http://www.disgenet.org/web/DisGeNET/menu)和Therapeutic Target(http://db.idrblab.org/ttd/)中检索牙周炎的潜在作用靶点,“Organism”选择“Homo sapients”,合并相关数据库去重后,得到牙周炎的相关靶基因。

1.2. 姜黄素相关作用靶点的筛选

姜黄素的2D和3D化学结构通过PubChem(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/home/chemicals)获得。通过数据库SwissTarget Prediction(http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/)、DrugBank(http://www.drugbank.ca/)、PharmMapper(http://lilab.e-cust.edu.cn/pharmmapper/index.php)获得姜黄素的潜在作用靶点。“Organism”选取“Homo sapients”,合并相关数据库去重后,得到姜黄素的相关靶基因。将其与1.1中所得靶点基因上传至在线作图工具(http://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/example.html),绘制韦恩图。

1.3. 蛋白质相互作用网络图构建

将姜黄素和牙周炎的交互靶基因导入String平台(http://string-db.org/)进行整合,构建蛋白质相互作用(protein-protein interaction,PPI)网络图,得到姜黄素靶点蛋白与牙周炎靶点蛋白之间的相互作用关系。

1.4. 基因本体论功能分析和京都基因与基因组百科全书通路富集分析

通过DAVID(https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp)[14]进行基因本体论(gene ontology,GO)、京都基因与基因组百科全书(Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes,KEGG)通路富集分析,收集生物过程(biological process,BP)、细胞组分(cellular component,CC)和分子功能(molecular function,MF)3部分以及KEGG富集分析数据并绘制网络图。

1.5. 分子对接分析及可视化

将PPI网络中的关键靶基因进行分子对接分析,从Protein Data Bank(PDB)数据库中下载靶基因对应蛋白3D结构,利用AutoDock Vina进行分子对接分析。通过两者结合能来评价其结合活性;结合能<0 kJ/mol,表示配体和受体能自发结合;结合能<−20.9 kJ/mol表示结合力良好[15]。选择结合能前8位的对接结果,应用PyMOL绘制结合模式图,进行对接模式展示。

2. 结果

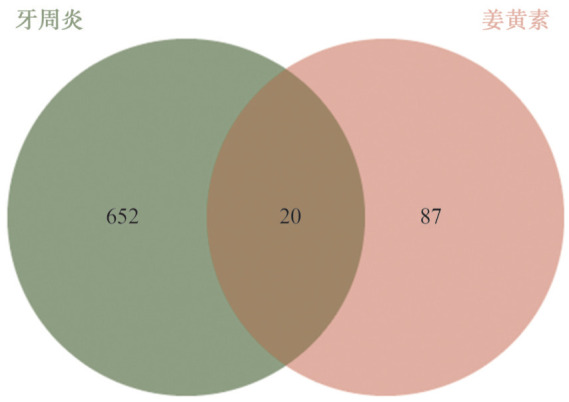

2.1. 牙周炎相关靶基因预测结果

从Therapeuti Target、Genecards和DisGeNET数据库分别获得1、560、287个和牙周炎相关靶基因,合并和去重后得到672个和疾病相关靶基因。

2.2. 姜黄素相关靶基因预测结果

通过PubChem数据库获得姜黄素2D和3D化学结构(图1A、B)。从SwissTargetPrediction、DrugBank和PharmMapper数据库分别获得67、13、29个和姜黄素相关靶基因,合并和去重后得到107个和牙周炎相关基因。

图 1. 姜黄素的结构.

Fig 1 Structures of curcumin

A:2D结构;B:3D结构。

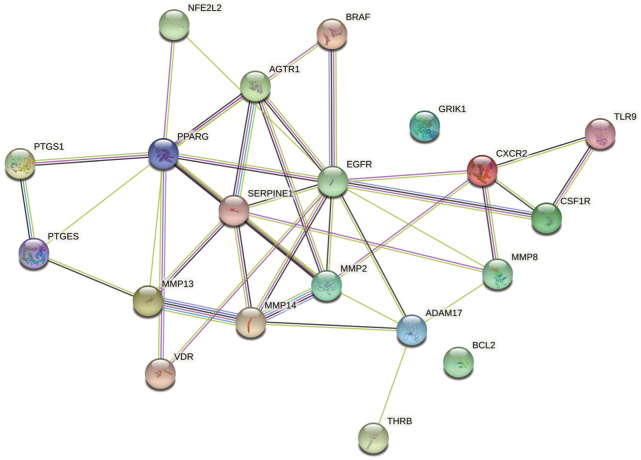

2.3. PPI网络图的构建

将672个牙周炎相关靶点和107个姜黄素作用靶点使用Venn线上分析工具jvenn(http://jvenn.toulouse.inra.fr/app/example.html)[16]取交集,获得20个姜黄素治疗牙周炎的预测靶点(图2),将结果导入蛋白互作分析网站String从而绘制PPI网络图(图3)。

图 2. 姜黄素与牙周炎交集靶点韦恩图.

Fig 2 Venn map of the intersection targets of curcumin and periodontitis

图 3. 姜黄素与牙周炎PPI图.

Fig 3 The targets PPI between curcumin and periodontitis

2.4. GO功能分析

将交集基因进行GO功能分析,其生物过程主要涉及炎症反应、细胞迁移的调控、基因表达的调控、蛋白质的水解作用、细胞增殖的调控等;细胞组成涉及细胞膜、细胞外基质、RNA聚合酶Ⅱ转录因子复合体;分子功能主要集中在锌离子结合、肽链内切酶活性、金属内切酶活性、序列特异性DNA结合、丝氨酸内切酶活性等(图4)。

图 4. 核心靶点的GO功能分析.

Fig 4 Go enrichment analysis of potential targets

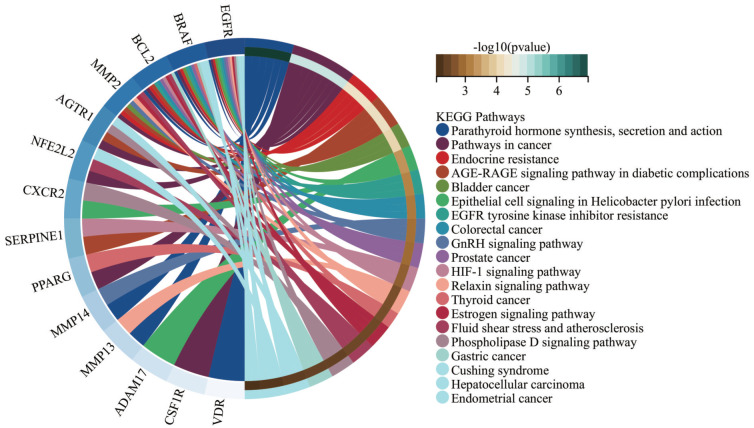

2.5. KEGG通路富集分析

对涉及的20个核心靶点进行KEGG通路富集分析(图5)发现,和炎症相关的通路主要富集于甲状旁腺激素(parathyroid hormone,PTH)的合成分泌、表皮生长受体-酪氨酸酶抑制剂抵抗、低氧诱导因子(hypoxia-inducible factor,HIF)信号转导通路等。

图 5. 核心靶点的KEGG分析.

Fig 5 KEGG analysis of potential targets

2.6. 分子对接分析

对筛选到的20个潜在关键靶点进行分子对接分析发现(表1),姜黄素和其中18个靶点蛋白的结合能小于−20.9 kJ/mol,提示姜黄素与PTGS1、PTGES、MMP13、VDR、MMP14、SERPINE1、PPARG、AGTR1、BRAF、EGFR、MMP2、THRB、ADAM17、GRIK1、MMP8、CSF1R、TLR9、BCL2有良好的结合力。利用PyMOL软件将分子对接技术可视化,其结合能排名前8的3D对接可视化结果如图6所示。

表 1. 姜黄素与牙周炎的交集靶基因.

Tab 1 Intersection target genes of curcumin and periodontitis

| 基因名称 | 蛋白名称 | 结合能/(kJ/mol) |

| NFE2L2 | 核转录因子E2相关因子2 | −19.90 |

| PTGS1 | 前列腺素过氧化合成酶1 | −26.63 |

| PTGES | 前列腺素E合酶 | −23.78 |

| MMP13 | 基质金属蛋白酶13 | −34.69 |

| VDR | 维生素D受体 | −22.70 |

| MMP14 | 基质金属蛋白酶14 | −29.05 |

| SERPINE1 | 纤溶酶原激活物抑制剂1 | −21.19 |

| PPARG | 过氧化物酶增殖体激活受体 | −23.24 |

| AGTR1 | 血管紧张素Ⅱ-1型受体 | −31.18 |

| BRAF | 苏氨酸蛋白激酶 | −24.66 |

| EGFR | 表皮生长因子受体 | −26.54 |

| MMP2 | 基质金属蛋白酶2 | −27.80 |

| THRB | 凝血酶原 | −27.80 |

| ADAM17 | 整合素金属蛋白酶17 | −27.55 |

| GRIK1 | 谷氨酸受体编码基因1 | −27.80 |

| CXCR2 | 趋化因子受体2 | −17.89 |

| MMP8 | 基质金属蛋白酶8 | −28.97 |

| CSF1R | 巨噬细胞集落刺激因子1受体 | −27.21 |

| TLR9 | Toll样受体9 | −29.26 |

| BCL2 | B细胞白血病/淋巴癌2 | −32.94 |

图 6. 分子对接的3D可视化效果.

Fig 6 3D visualization of the molecule docking

3. 讨论

虽然姜黄素对牙周炎的作用已得到证实,但是其具体的分子机制尚未完全阐明。前期的实验多集中于直接探究姜黄素对牙周炎相关免疫细胞或细胞因子的作用[17]–[19],较少关注姜黄素的作用靶点基因。本研究通过构建“药物-靶点-疾病”网络,识别药物与靶点之间相互作用,探讨姜黄素治疗牙周炎的潜在靶点和分子机制。

筛选出的交集靶基因包括MMP-13、Bcl-2、AGTR1、TLR9等,对这些基因通过GO功能和KEGG富集分析显示,姜黄素作用于牙周炎的机制多集中于HIF-α信号转导通路、PTH等。既往研究[20]–[23]发现,HIF-1α在牙周炎患者牙龈组织中、龈沟液以唾液中的表达显著高于牙周健康者,且其表达量与牙周炎严重程度呈正相关关系。同时HIF-1α可提高核转录因子-κB转录促进白细胞介素(interleukin,IL)-1β、肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor,TNF)-α的产生[24],从而促进牙周炎症反应的发生。PTH是由甲状旁腺细胞合成分泌的多肽分子,机体内成纤维细胞生长因子(fibroblast growth factor,FGF)23、维生素D、PTH组成一个复杂的、多组织的反馈系统。FGF23和碱性磷酸酶(alkaline phosphatase,ALP)是成骨细胞分化的早期标志之一,当FGF23和ALP水平变化时,提示成骨细胞前体向成骨细胞分化情况[25]。既往试验[26]–[29]发现,PTH能够提高FGF23和ALP的水平,从而上调1,25(OH)2D的合成,减轻牙槽骨的吸收,降低炎症细胞在牙周炎症组织中的浸润,提高骨的再生潜能,因此,姜黄素治疗牙周炎可能与这些途径有关。

分子对接结果发现,MMP-2、8、13、14在分子对接能量表中排名前几位,说明MMP是姜黄素作用于牙周炎重要的靶点之一。MMP是钙依赖性含锌肽内切酶的重要家族[30],MMP的激活导致细胞外基质蛋白的降解,从而导致牙周组织的破坏[31]–[32]。前期试验[33]–[37]发现,MMP-2、8、13、14在牙周炎患者龈沟液以及局部牙周组织中显著高于牙周健康者。MMP-2上调不仅导致结合上皮向根方迁移,结缔组织附着地破坏[38],同时,MMP-2还可通过诱发纤维蛋白碎片诱导细胞凋亡,抑制成骨细胞分化[39]。MMP-8和MMP-13同属于胶原酶,MMP-8和MMP-13被认为和牙周炎破坏最密切的细胞因子[39],牙周组织中的MMP-8、MMP-13可促进中性粒细胞的迁移,促进胶原以及细胞外基质的降解[39]–[40]。MMP-8由中性粒细胞分泌,通过调节激素受体,增强中性粒细胞髓过氧化物酶的活性[39]–[41],它的表达水平和牙周炎炎症程度呈正相关关系[42]。MMP-13可通过降解破骨细胞生成抑制因子半乳糖凝集素-3,导致核因子κB受体活化因子配体-转化生长因子-β1通路的激活,破骨作用增加[43]。MMP-14是一类膜型基质金属蛋白酶,属于Ⅰ型穿膜蛋白[39]。MMP-14不仅可以降解Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ型胶原,还可以通过激活MMP-2前体(proMMP-2)、proMMP-9、proMMP-13发挥胶原降解的作用。同时,MMP-14能够激活牙周炎症部位的MMP-8和MMP-13,加重牙周组织的破坏[39]。

TLR9主要通过激活B细胞和抗原提呈细胞的免疫活性,发挥促炎作用。TLR9信号的激活促进炎症反应的发生,产生如干扰素、IL-12之类的细胞因子[44],加重牙周炎症反应,同时TLR9的表达与牙周炎的炎症程度呈正相关关系[45]。Bcl-2是凋亡抑制基因,位于细胞内膜、内质网、线粒体外膜上,也参与了牙周炎的发展过程[46]。牙周炎患者局部组织中自由基和过氧化物增多,抗氧化物减少,而低水平氧自由基可诱导细胞凋亡,Bcl-2可通过减少活性氧启动信号转导途径抑制细胞凋亡,促进牙周组织的再生。因此,姜黄素可能通过调节MMP、TLR9以及Bcl-2等参与牙周炎的治疗。

综上,本研究通过网络药理学和分子对接技术分析,发现姜黄素可能通过多个靶点及其相关通路从而发挥治疗牙周炎的作用,为进一步探究姜黄素治疗牙周炎提供理论线索与实验依据。

Funding Statement

[基金项目] 四川省科技计划资助(2022NSFSC1521);广州市卫生健康科技一般引导项目(20221A011101);国家自然科学基金(82170970)

Supported by: Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022NSFSC1521); Guangzhou Health Science and Technology General Guidance Project (20221A011101); The National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170970).

Footnotes

利益冲突声明:作者声明本文无利益冲突。

References

- 1.孟 焕新. 牙周病学[M] 5版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社; 2020. pp. 321–323. [Google Scholar]; Meng HX. Periodontology[M] 5th ed. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House; 2020. pp. 321–323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J] Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanz M, Beighton D, Curtis MA, et al. Role of microbial biofilms in the maintenance of oral health and in the development of dental caries and periodontal diseases. Consensus report of group 1 of the Joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal disease[J] J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(Suppl 18):S5–S11. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomasi C, Leyland AH, Wennström JL. Factors influencing the outcome of non-surgical periodontal treatment: a multilevel approach[J] J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34(8):682–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Lang NP. Surgical and nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Learned and unlearned concepts[J] Periodontol 2000. 2013;62(1):218–231. doi: 10.1111/prd.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadi H, Ebrahimi A, Ahmadi F. Antibiotic therapy in dentistry[J] Int J Dent. 2021;2021:6667624. doi: 10.1155/2021/6667624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.蒋 宸, 韩 琪, 杨 靖梅. 姜黄素防治牙周炎的研究进展[J] 中华口腔医学杂志. 2020;55(9):685–690. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20191118-00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jiang C, Han Q, Yang JM. Research progress of curcumin in the prevention and treatment of periodontitis[J] Chin J Stomatol. 2020;55(9):685–690. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20191118-00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahalkar A, Kumathalli K, Kumar R. Determination of efficacy of curcumin and Tulsi extracts as local drugs in periodontal pocket reduction: a clinical and microbiological study[J] J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2021;25(3):197–202. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_158_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pérez-Pacheco CG, Fernandes NAR, Primo FL, et al. Local application of curcumin-loaded nanoparticles as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind split-mouth clinical trial[J] Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(5):3217–3227. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03652-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guru SR, Reddy KA, Rao RJ, et al. Comparative evaluation of 2% turmeric extract with nanocarrier and 1% chlorhexidine gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in patients with chronic periodontitis: a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial[J] J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2020;24(3):244–252. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_207_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Huang L, Zhang J, et al. Anti-inflammatory efficacy of curcumin as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J] Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:808460. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.808460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Huang L, Mazurel D, et al. Clinical efficacy of curcumin versus chlorhexidine as an adjunct to scaling and root planing for the treatment of periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J] Phytother Res. 2021;35(11):5980–5991. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng B, McClements DJ. Formulation of more efficacious curcumin delivery systems using colloid science: enhanced solubility, stability, and bioavailability[J] Molecules. 2020;25(12):2791. doi: 10.3390/molecules25122791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman BT, Hao M, Qiu J, et al. DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update)[J] Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W216–W221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.郝 民琦, 王 佳慧, 李 晓玲, et al. 基于网络药理学与分子对接探讨黄芪治疗溃疡性结肠炎的作用机制[J] 中国药房. 2021;32(10):1215–1223. [Google Scholar]; Hao MQ, Wang JH, Li XL, et al. Study on the mechanism of Astragali Radix in the treatment of ulcerative colitis based on network pharmacology and molecular docking[J] Chin Pharm. 2021;32(10):1215–1223. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardou P, Mariette J, Escudié F, et al. jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer[J] BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(1):293. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong R, Kang OH, Seo YS, et al. MAPKs and NF‑κB pathway inhibitory effect of bisdemethoxycurcumin on phorbol‑12‑myristate‑13‑acetate and A23187‑induced inflammation in human mast cells[J] Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(1):630–635. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reuter S, Charlet J, Juncker T, et al. Effect of curcumin on nuclear factor kappaB signaling pathways in human chronic myelogenous K562 leukemia cells[J] Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171:436–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Jiao J, Qi Y, et al. Curcumin: a review of experimental studies and mechanisms related to periodontitis treatment[J] J Periodontal Res. 2021;56(5):837–847. doi: 10.1111/jre.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afacan B, Öztürk VÖ, Paşalı Ç, et al. Gingival crevicular fluid and salivary HIF-1α, VEGF, and TNF-α levels in periodontal health and disease[J] J Periodontol. 2019;90(7):788–797. doi: 10.1002/JPER.18-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng KT, Li JP, Ng KM, et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in human periodontal tissue[J] J Periodontol. 2011;82(1):136–141. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasconcelos RC, Costa Ade L, Freitas Rde A, et al. Immunoexpression of HIF-1α and VEGF in periodontal disease and healthy gingival tissues[J] Braz Dent J. 2016;27(2):117–122. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201600533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi QY, Huang SG, Zeng JH, et al. Expression of hypoxia inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor-C in human chronic periodontitis[J] J Dent Sci. 2015;10(3):323–333. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn JK, Koh EM, Cha HS, et al. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in hypoxia-induced expressions of IL-8, MMP-1 and MMP-3 in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes[J] Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(6):834–839. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, et al. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism[J] J Clin Invest. 2004;113(4):561–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI19081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barros SP, Silva MA, Somerman MJ, et al. Parathyroid hormone protects against periodontitis-associated bone loss[J] J Dent Res. 2003;82(10):791–795. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasconcelos DF, Marques MR, Benatti BB, et al. Intermittent parathyroid hormone administration improves periodontal healing in rats[J] J Periodontol. 2014;85(5):721–728. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokunaga K, Seto H, Ohba H, et al. Topical and intermittent application of parathyroid hormone recovers alveolar bone loss in rat experimental periodontitis[J] J Periodontal Res. 2011;46(6):655–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bashutski JD, Eber RM, Kinney JS, et al. Teriparatide and osseous regeneration in the oral cavity[J] N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2396–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Yang X, Zhang H, et al. The role of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer glycosylation in regulating matrix metalloproteinases in periodontitis[J] J Periodontal Res. 2018;53(3):391–402. doi: 10.1111/jre.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorsa T, Ding YL, Ingman T, et al. Cellular source, activation and inhibition of dental plaque collagenase[J] J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22(9):709–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yakob M, Meurman JH, Sorsa T, et al. Treponema denticola associates with increased levels of MMP-8 and MMP-9 in gingival crevicular fluid[J] Oral Dis. 2013;19(7):694–701. doi: 10.1111/odi.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorsa T, Gursoy UK, Nwhator S, et al. Analysis of matrix metalloproteinases, especially MMP-8, in gingival creviclular fluid, mouthrinse and saliva for monitoring periodontal diseases[J] Periodontol 2000. 2016;70(1):142–163. doi: 10.1111/prd.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leppilahti JM, Hernández-Ríos PA, Gamonal JA, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases and myeloperoxidase in gingival crevicular fluid provide site-specific diagnostic value for chronic periodontitis[J] J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(4):348–356. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X, Zhang Z, Pan S, et al. Interaction between the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and the EMMPRIN/MMP-2, 9 route in periodontitis[J] J Periodontal Res. 2018;53(5):842–852. doi: 10.1111/jre.12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiili M, Cox SW, Chen HY, et al. Collagenase-2 (MMP-8) and collagenase-3 (MMP-13) in adult periodontitis: molecular forms and levels in gingival crevicular fluid and immunolocalisation in gingival tissue[J] J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(3):224–232. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baeza M, Garrido M, Hernández-Ríos P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy for apical and chronic periodontitis biomarkers in gingival crevicular fluid: an exploratory study[J] J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(1):34–45. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Checchi V, Maravic T, Bellini P, et al. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in periodontal disease[J] Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4923. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luchian I, Goriuc A, Sandu D, et al. The role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13) in periodontal and peri-Implant pathological processes[J] Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1806. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo KW, Chen W, Lung WY, et al. EGCG inhibited bladder cancer SW780 cell proliferation and migration both in vitro and in vivo via down-regulation of NF-κB and MMP-9[J] J Nutr Biochem. 2017;41:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sapna G, Gokul S, Bagri-Manjrekar K. Matrix metalloproteinases and periodontal diseases[J] Oral Dis. 2014;20(6):538–550. doi: 10.1111/odi.12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khuda F, Anuar NNM, Baharin B, et al. A mini review on the associations of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)-1,-8,-13 with periodontal disease[J] AIMS Mol Sci. 2021;8:13–31. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pivetta E, Scapolan M, Pecolo M, et al. MMP-13 stimulates osteoclast differentiation and activation in tumour breast bone metastases[J] Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(5):R105. doi: 10.1186/bcr3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tabeta K, Georgel P, Janssen E, et al. Toll-like receptors 9 and 3 as essential components of innate immune defense against mouse cytomegalovirus infection[J] Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(10):3516–3521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400525101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen YC, Liu CM, Jeng JH, et al. Association of pocket epithelial cell proliferation in periodontitis with TLR9 expression and inflammatory response[J] J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113(8):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karatas O, Balci Yuce H, Tulu F, et al. Evaluation of apoptosis and hypoxia-related factors in gingival tissues of smoker and non-smoker periodontitis patients[J] J Periodontal Res. 2020;55(3):392–399. doi: 10.1111/jre.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]