Abstract

Vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs) can emerge from Sabin strain poliovirus serotypes 1, 2, and 3 contained in oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) after prolonged person-to-person transmission where population vaccination immunity against polioviruses is suboptimal. VDPVs can cause paralysis indistinguishable from wild polioviruses and outbreaks when community circulation ensues. VDPV serotype 2 outbreaks (cVDPV2) have been documented in The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since 2005. The nine cVDPV2 outbreaks detected during 2005–2012 were geographically-limited and resulted in 73 paralysis cases. No outbreaks were detected during 2013–2016. During January 1, 2017–December 31, 2021, 19 cVDPV2 outbreaks were detected in DRC. Seventeen of the 19 (including two first detected in Angola) resulted in 235 paralysis cases notified in 84 health zones in 18 of DRC’s 26 provinces; no notified paralysis cases were associated with the remaining two outbreaks. The DRC-KAS-3 cVDPV2 outbreak that circulated during 2019–2021, and resulted in 101 paralysis cases in 10 provinces, was the largest recorded in DRC during the reporting period in terms of numbers of paralysis cases and geographic expanse. The 15 outbreaks occurring during 2017–early 2021 were successfully controlled with numerous supplemental immunization activities (SIAs) using monovalent OPV Sabin-strain serotype 2 (mOPV2); however, suboptimal mOPV2 vaccination coverage appears to have seeded the cVDPV2 emergences detected during semester 2, 2018 through 2021. Use of the novel OPV serotype 2 (nOPV2), designed to have greater genetic stability than mOPV2, should help DRC’s efforts in controlling the more recent cVDPV2 outbreaks with a much lower risk of further seeding VDPV2 emergence. Improving nOPV2 SIA coverage should decrease the number of SIAs needed to interrupt transmission. DRC needs the support of polio eradication and Essential Immunization (EI) partners to accelerate the country’s ongoing initiatives for EI strengthening, introduction of a second dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) to increase protection against paralysis, and improving nOPV2 SIA coverage.

Keywords: Polio eradication, Acute flaccid paralysis, Surveillance, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Africa, Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2, Monovalent oral polio vaccine type 2, Novel oral polio vaccine type 2, Poliovirus environmental surveillance, Poliovirus outbreak response, Supplemental immunization activities

1. Introduction

Vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs) can emerge from Sabin strain poliovirus serotypes 1, 2, and 3 contained in the oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) after prolonged person-to-person transmission [1]. This prolonged transmission, occurring where population vaccination immunity against polioviruses is suboptimal, can lead to viral genetic mutations resulting in reversion to neurovirulence causing clinical disease indistinguishable from that caused by wild poliovirus (WPV) [1]. When community circulation of VDPVs is confirmed (i.e., an outbreak), these viruses are classified as circulating VDPVs (cVDPVs) [1]. Other classifications of VDPVs are 1) immunodeficiency-associated (iVDPVs) when isolated from persons with primary immunodeficiency or 2) ambiguous (aVDPVs), a classification of exclusion when not associated with immune-deficiency or community circulation when detected though acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) or environmental surveillance (ES) [1].

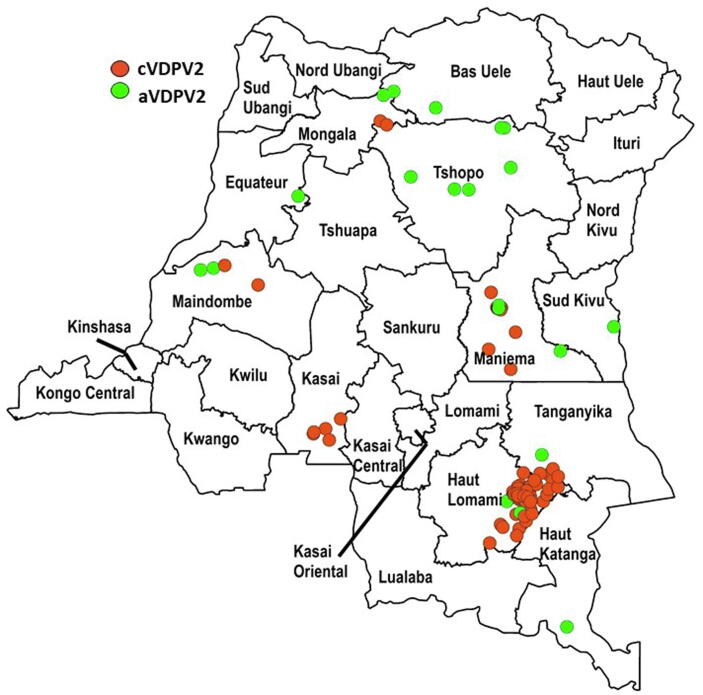

The Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) essential (routine) childhood immunization (EI) schedule for polio has included an OPV dose at birth, plus three additional doses administered by 14 weeks of age [2], [3]. During 1980–2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF estimated national coverage of third dose OPV (OPV3) vaccination delivered through EI never exceeded 78 % and has often been under 70 %, including since 2016 [2], [3]. During 1996–2016, EI OPV immunization was frequently supplemented by national and/or sub-national polio supplemental immunization activities (SIAs) with trivalent OPV (tOPV, containing Sabin-strain serotypes 1, 2, and 3), bivalent OPV (bOPV, containing Sabin-strain serotypes 1 and 2) and monovalent OPV Sabin-strain serotypes 1 or 3 (mOPV1, mOPV3). SIAs implemented house-to-house vaccination targeting children 0–59 months of age, or older age groups if epidemiologically justified, to fill immunity gaps and as response to WPV serotype 1 and 3 and cVDPV serotype 2 (cVDPV2) outbreaks [4], [5], [6]. Despite the preventive SIAs aimed at filling immunity gaps, VDPVs emerged and circulated during 2004–2016 (Fig. 1) [1], [7], [8]. During the 2004-2016 period, there were 93 AFP cases with VDPV serotype 2 (VDPV2) isolated from stool specimens; 73 (79 %) of the 93 AFP cases were associated with 9 cVDPV2 outbreaks with each of the remaining 20 (21 %) AFP cases associated with an independent aVDPV serotype 2 (aVDPV2) (Fig. 1) [7], [8]. Overall, 70 (75 %) of the 93 AFP cases were notified in, and six (67 %) of the 9 cVDPV2 outbreaks affected, Haut Lomami, Maniema, and Tanganyika provinces, suggesting a particular susceptibility in southeastern DRC (Fig. 1) [7], [8]. After the Haut Lomami cVDPV2 outbreak spanning 2011–2012 that resulted in 29 cVDPV2 cases, there were only five AFP cases associated with five unrelated aVDPV2s isolated during 2013–2016 (i.e., no cVDPV2 outbreaks) [7], [8].

Fig. 1.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases with ambiguous (aVDPV2) or circulating (cVDPV2) vaccine-derived poliovirus serotype 2 isolated from specimens, with onset of paralysis January 1, 2004-December 31, 2016, cumulative, by province. In 2006 and 2013, no AFP cases in DRC had any VDPV in specimens. For details, by province, see references 7 and 8.

DRC’s last SIAs using tOPV were conducted in March and April 2016 just prior to the globally synchronized switch from tOPV to bOPV [6], [9]. Following the 2015 declaration of WPV serotype 2 eradication, the use of tOPV was ceased globally on May 1, 2016 when tOPV was replaced with bOPV in EI and preventative SIAs [9]. In addition to bOPV replacing tOPV, a single dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV, containing serotypes 1,2, and 3) was introduced in OPV-using countries to provide some level of poliovirus serotype 2 immunity against paralysis; accordingly, in April 2015, one dose of IPV was introduced into DRC’s EI schedule at 14 weeks of age [2], [3], [10], [11]. We provide a comprehensive description of the epidemiology of cVDPV2s detected in DRC during the years after the 2016 tOPV to bOPV switch, January 1, 2017–December 31, 2021 [8], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17].

2. Methods

2.1. Surveillance for poliovirus

AFP surveillance: new-onset upper or lower limb flaccid weakness in any child < 15 years of age, clinician-suspected poliomyelitis in a person of any age, or sudden and severe difficulty breathing in a person >=15 years of age with no prior history of asthma or cardiac disease was reported to DRC’s Ministry of Public Health, Hygiene, and Prevention for investigation. These criteria met the WHO Regional Office for Africa (WHO-AFRO) and DRC’s AFP case definition or, for the latter, DRC’s expanded case definition [18], [19]. Two stool specimens were collected from each person with a reported AFP case and analyzed for the presence of poliovirus [18], [19]. Cases reported to DRC’s Ministry of Public Health, Hygiene, and Prevention with paralysis onset during January 1, 2017–December 31, 2021 were reviewed. AFP case classification as confirmed polio, non-polio, or polio-compatible was made after laboratory testing [19].

Data regarding direct and community contacts of AFP case-patients having paralysis onset during January 1, 2017–December 31, 2021 were reviewed. A direct contact of an AFP case-patient was a child younger than five years of age who had direct contact with the AFP case-patient in the week prior to and/or in the two-week period after paralysis onset [20]. A stool specimen was collected from direct contacts to assist with laboratory confirmation of the cause of AFP in the reported case if poliovirus was not isolated from the case-patient’s stool or an adequate stool sample could not be collected. That is, a poliovirus-positive laboratory result from a direct contact of an AFP case-patient could be used to confirm poliovirus infection in that case. Stool specimens collected from community contacts of AFP case-patients with confirmed poliovirus were frequently used to confirm poliovirus circulation within a community. For community contacts, one stool specimen was collected from each of 20 healthy children (<5 years but preferably < 2 years and with no evidence of AFP) residing in another part of the same community or in a nearby community of the poliovirus-positive AFP case-patient [20].

ES: the systematic collection of environmental samples (i.e., sewage/fecally-contaminated environmental waters) for poliovirus testing was initiated in DRC in quarter 3,2017 and expanded following Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) guidelines [21], [22] (Table 1). ES samples were collected using the grab method from open wastewater canals located in the provinces’ larger population centers; many sites were revised over time to optimize surveillance performance [6], [21], [22].

Table 1.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Environmental surveillance (ES) for polioviruses, numbers of samples collected (and sites operational), by weeks, during week 27, 2017-week 52, 2021, by province. Specific site locations might have been changed during the reporting period to optimize ES performance; detailed descriptions of specific collection sites are beyond the scope of this report.

| Province |

Weeks in 2017 |

Weeks in 2018 |

Weeks in 2019 |

Weeks in 2020 |

Weeks in 2021 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27–39 | 40–52 | 1–13 | 14–26 | 27–39 | 40–52 | 1–13 | 14–26 | 27–39 | 40–52 | 1–13 | 14–26 | 27–39 | 40–52 | 1–13 | 14–26 | 27–39 | 40–52 | |

| Haut Katanga | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 9 (2) | 14 (2) | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | 14 (2) | 14 (2) | 12 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 8 (2) | 12 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Kinshasa | 2 (2) | 6 (2) | 8 (2) | 14 (2) | 18 (4) | 28 (4) | 23 (4) | 42 (6) | 36 (6) | 41 (6) | 23 (6) | 12 (6* | 19 (6) | 24 (6) | 26 (6) | 27 (6) | 28 (6) | 27 (6) |

| Maniema | 2 (2) | 6 (2) | 10 (2) | 12 (2) | 14 (2) | 6 (2) | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | 14 (2) | 8 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | 10 (2) | 10 (2) | 10 (2) | 14 (2)* |

| Tshopo | 2 (2) | 8 (2) | 16 (2) | 14 (2) | 12 (2) | 8 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | |||||

| Kongo Central | 4 (2) | 8 (2) | 6 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | |||||||||

| Lualaba | 6 (2) | 7 (2) | 8 (2) | 12 (2) | 10 (2) | |||||||||||||

| Equateur | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 4 (2) | |||||||||||||

| Kwilu | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | |||||||||||||||

Poliovirus genetically linked to the DRC-KAS-3 cVDPV2 emergence was isolated from one environmental sample collected on May 7, 2020 in Kinshasa province, and poliovirus genetically linked to the DRC-MAN-3 and DRC-MAN-4 cVDPV2 emergences was isolated from three environmental samples collected in Maniema province during October 15-December 7, 2021.

2.2. Laboratory testing

Standard methods for poliovirus testing involve processing stool specimens and ES wastewater samples for poliovirus isolation followed by inoculation on cultures of RD and L20B cells [1]. Any poliovirus isolated from cell culture was serotyped, characterized, and underwent genomic sequencing and analysis [1]. Each genomic sequence was compared to Sabin-type parent strains and previously isolated wild and vaccine-derived polioviruses. VDPV2 is defined as poliovirus with >=6 nucleotide substitutions from type 2 Sabin-strain on genomic sequence analysis of the VP1 coding region [1], [23].

2.3. Confirmed circulating VDPV2 (cVDPV2)

Case and outbreak confirmation: Cases and isolates for cVDPV2 positive AFP cases, AFP case direct and community contacts, and environmental samples were classified per definitions in the WHO-AFRO AFP surveillance guidelines, GPEI ES guidelines, and VDPV reporting and classification guidelines [19], [21], [23]. VDPV2 found in specimens of a case-patient, confirms a VDPV2 case [23]. AFP cases without VDPV2 isolation were also classified as confirmed VDPV2 if specimens from the case-patient’s direct contact(s) yielded VDPV2 isolation [20]. VDPV2s were classified as circulating (cVDPV2) when there were >=2 independent isolations of genetically linked virus: through AFP and/or environmental surveillance or from healthy community contacts among themselves or following confirmation of a VDPV-positive specimen from an AFP case-patient [23]. Finding evidence of circulation defines a cVDPV2 outbreak [1], [23].

cVDPV2 emergence groups: Each emergence group originates from Sabin-strain type 2 starting reversion to neurovirulence in prolonged transmission in an under-immunized community [1]. Identification of new, independent emergences based on genomic sequence analysis is made when patterns of nucleotide substitutions are unique relative to prior emergences. Names of cVDPV2 emergence groups indicate the country and subnational region where first identified and the sequential number of any further independent emergences from the subnational region [13], [14]. Each emergence group of cVPDV2 is considered a new outbreak. With approximately 1 % nucleotide changes (∼9) per year in circulation, this allows an estimation of the time of the type 2 Sabin-strain source for that emergence group [1].

2.4. Outbreak response SIAs using mOPV2

Bulletins of DRC’s Centre des Operations d'Urgence Polio (COUP, Emergency Operations Center for Polio) and DRC’s WHO Country Office (WHO-DRC) provided the dates and health zones (HZs) where monovalent OPV Sabin-strain serotype 2 (mOPV2) outbreak response SIAs were conducted [6], [8], [24], [12], [13], [14].

2.5. Analytical and geographic software

Maps in Fig. 1, Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B, Fig. 3 were created using ArcGIS Version 10.8.1 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). Analysis of VP1 nucleotide sequences were conducted using the bioinformatics software Geneious Prime 2020.2.4 (https://www.geneious.com) [25].

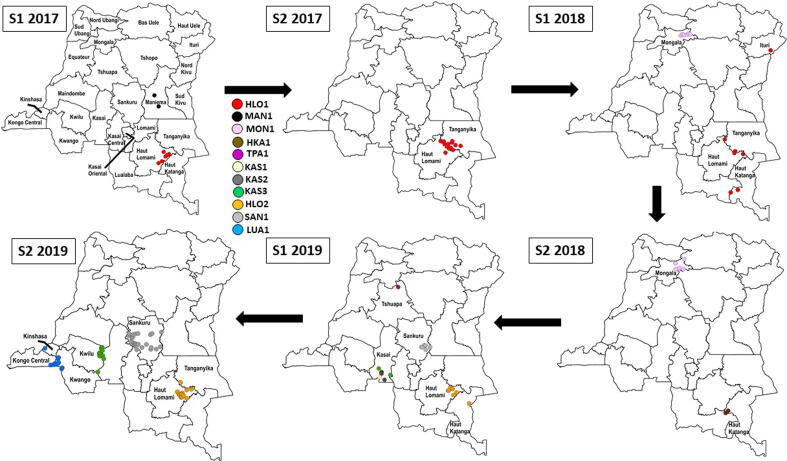

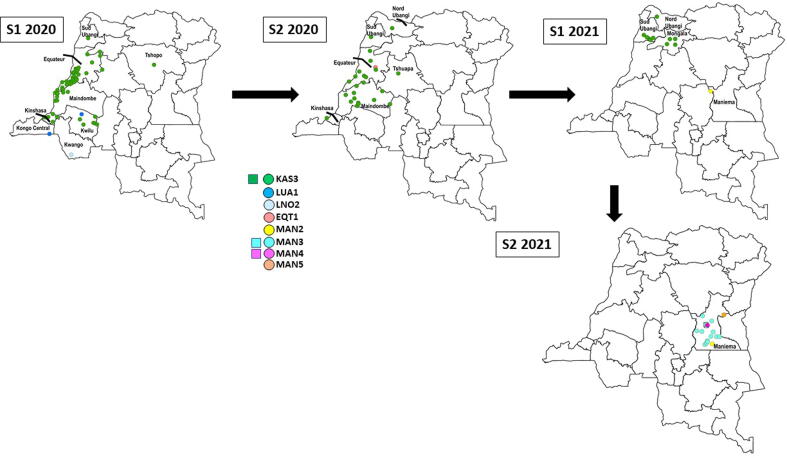

Fig. 2A.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases (◯) confirmed positive for circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus serotype 2 (cVDPV2), by emergence group and semester (S) of year of paralysis onset, January 1, 2017–December 31, 2019. The map for S1 2017 indicates all DRC province names; in subsequent maps, only provinces with AFP cases confirmed positive for cVDPV2 are labelled.

Fig. 2B.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases (◯) confirmed positive for and environmental samples (□) with circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus serotype 2 (cVDPV2), by emergence group and semester (S) of year of paralysis onset or sample collection, January 1, 2020–December 31, 2021.The map for S1 2017 indicates all DRC province names (Fig. 2A); in subsequent maps, only provinces with AFP cases confirmed positive for or environmental samples with cVDPV2 are labelled. DRC-TPA-2 and CAR-BNG-1 do not appear of these maps because genetically linked virus was not detected in AFP cases in DRC.

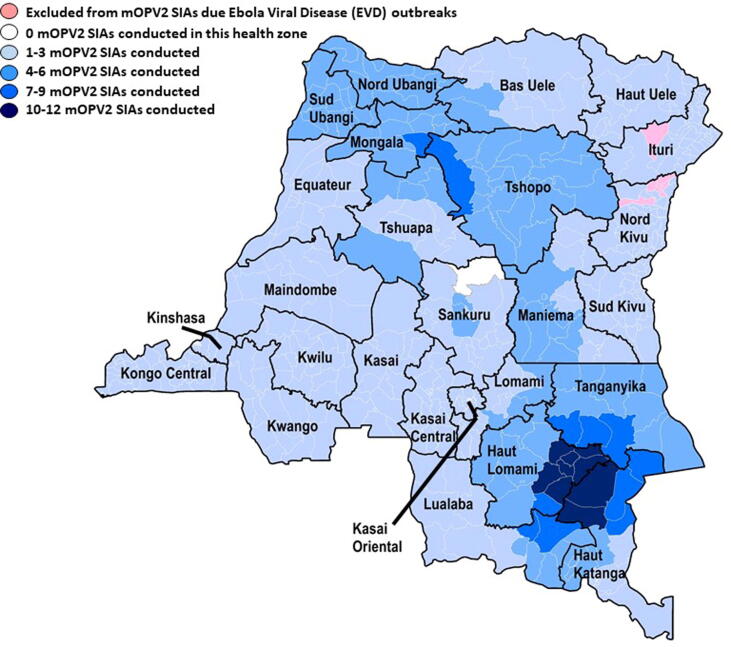

Fig. 3.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Numbers of monovalent oral polio vaccine Sabin-strain serotype 2 (mOPV2) Supplementary Immunization Activities (SIAs) conducted in response to circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus serotype 2 (cVDPV2) outbreaks, by health zone, June 2017–April 2021.

3. Results

3.1. Overall epidemiologic situation

During January 1, 2017–December 31, 2021, viruses genetically linked to 19 cVDPV2 outbreaks were detected in DRC. Seventeen of the 19 (including two first detected in Angola) resulted in 235 cases of paralysis notified in 84 HZs in 18 of DRC’s 26 provinces [8], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. An 18th cVDPV2 outbreak (DRC-TPA-2) was detected among a group of healthy children, and a 19th outbreak, first identified in CAR (CAR-BNG-1), was detected among direct contacts of an AFP case; however, no genetically linked virus was isolated from specimens of the associated AFP case-patient [17]. Transmission for the four 2021 emergence outbreaks continued into 2022 [6]. Table 2 provides the characteristics of the 19 cVDPV2 outbreaks. Table 1 illustrates the implementation of ES for polioviruses during the reporting period, by province and weeks of the year [6]. Of the 972 samples collected, poliovirus genetically linked to only three emergence groups were detected through ES.

Table 2.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) cases, other (human) sources, and environmental samples* with circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus serotype 2 (cVDPV2), by emergence name, date of onset of paralysis or sample collection, 2017–2021, and other characteristics.

| Emergence group | Total isolates [AFP + other (human)] | Total provinces with isolates |

AFP |

Other (human) |

Summary(2017-2021) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb. confirmed cVDPV2 positive AFP casesa | Onset of 1st case | Onset of last case | Nb. other positive samples | 1st collection date | Last collection date | Most recent virus isolation or paralysis onset in DRC* | Interval between 1st and last isolation/onset (days) in DRC* | Nucleotidebchange range | |||

| DRC-HLO-1 | 47 | 4 | 25 + 2a | 20 Feb 2017 | 27 May 2018 | 20 | 20 Jul 2017 | 15 Feb 2018 | 27 May 2018 | 461 | 14–29 |

| DRC-MAN-1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 26 Mar 2017 | 18 Apr 2017 | 1 | 5 May 2017 | 5 May 2017 | 5 May 2017 | 40 | 7–9 |

| DRC-MON-1 | 19 | 1 | 7 + 4a | 26 Apr 2018 | 13 Sep 2018 | 8 | 7 May 2018 | 8 Nov 2018 | 8 Nov 2018 | 196 | 18–26 |

| DRC-HKA-1 | 2 | 1 | 1 + 1a | 6 Oct 2018 | 7 Oct 2018 | 0 | – | – | 7 Oct 2018 | 1 | 7–8 |

| DRC-KAS-1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 8 Feb 2019 | 8 Feb 2019 | 2 | 16 Mar 2019 | 17 Mar 2019 | 17 Mar 2019 | 37 | 6–7 |

| DRC-HLO-2 | 26 | 3 | 20 | 10 Feb 2019 | 28 Oct 2019 | 6 | 23 Jun 2019 | 13 Dec 2019 | 13 Dec 2019 | 306 | 8–16 |

| DRC-KAS-2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 Apr 2019 | 7 Jun 2019 | 1 | 24 May 2019 | 24 May 2019 | 7 Jun 2019 | 65 | 6–11 |

| DRC-SAN-1 | 35 | 1 | 31 + 1a | 21 Apr 2019 | 30 Nov 2019 | 3 | 22 Jun 2019 | 27 Aug 2019 | 30 Nov 2019 | 223 | 6–17 |

| DRC-TPA-1 | 3 | 1 | 0 + 1a | 21 May 2019 | 21 May 2019 | 2 | 27 Jun 2019 | 14 Aug 2019 | 14 Aug 2019 | 85 | 7–10 |

| DRC-KAS-3 | 189 | 10 | 99 + 2a | 3 Jun 2019 | 30 Apr 2021 | 88 | 18 Nov 2019 | 21 Feb 2021 | 30 Apr 2021 | 697 | 8–28 |

| ANG-LUA-1 | 17 | 4 | 14 | 27 Sep 2019 | 29 Jan 2020 | 3 | 18 Nov 2019 | 22 Nov 2019 | 29 Jan 2020 | 124 | 6–12 |

| ANG-LNO-2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19 Feb 2020 | 19 Feb 2020 | 0 | – | – | 19 Feb 2020 | Not applicable | 19 |

| DRC-TPA-2 | 6 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 6 | 14 May 2020 | 14 May 2020 | 14 May 2020 | Not applicable | 6–7 |

| DRC-EQT-1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 4 Jul 2020 | 4 Jul 2020 | 9 | 18 May 2020 | 11 Sep 2020 | 11 Sep 2020 | 116 | 6–14 |

| CAR-BNG-1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 2 | 27 Oct 2020 | 27 Oct 2020 | 27 Oct 2020 | Not applicable | 21 |

| DRC-MAN-2¶ | 5 | 1 | 2 | 27 Jun 2021 | 16 Dec 2021 | 3 | 18 Aug 2021 | 19 Aug 2021 | 16 Dec 2021 | 172 | 7–13 |

| DRC-MAN-3¶ | 15 | 1 | 14 | 23 Oct 2021 | 31 Dec 2021 | 1 | 22 Nov 2021 | 22 Nov 2021 | 31 Dec 2021 | 77* | 9–18 |

| DRC-MAN-4¶ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 Nov 2021 | 13 Nov 2021 | 0 | – | – | 7 Dec 2021* | 24* | 11 |

| DRC-MAN-5¶ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30 Oct 2021 | 30 Oct 2021 | 0 | – | – | 30 Oct 2021 | Not applicable | 12 |

Poliovirus genetically linked to the KAS-3 cVDPV2 emergence was isolated from one environmental sample collected on May 7, 2020 in Kinshasa province, and poliovirus genetically linked to the MAN-3 and MAN-4 cVDPV2 emergences was isolated from three environmental samples collected in Maniema province during October 15-December 7, 2021.

11 AFP cases included in this table did not have cVDPV2 in their specimens but are counted as confirmed cVDPV2 positive AFP cases due to the cVDPV2 positivity of a direct contact. The AFP case-patient associated with the CAR-BNG-1 positive direct contacts had virus genetically linked to the DRC-KAS-3 cVDPV2 emergence in its specimens and thus is included in the case count for that emergence and not CAR-BNG-1. If the cVDPV2 positivity of a direct contact was used to confirm an AFP case as positive for cVDPV2, this contact was not included in the other (human) count to avoid the double counting of isolates.

The number of nucleotide differences in the VP1 region from the corresponding parental OPV Sabin strain.

Indicates emergences that circulated in 2022.

3.2. cVDPV2 outbreaks by year and DRC emergence group

2017 DRC-HLO-1: This emergence was first detected in specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in February 2017 notified in Malemba-Nkulu HZ (Haut Lomami) (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [8], [12], [13], [14], [15]. The cVDPV2 detected had 15 VP1 nucleotide differences from the parental Sabin 2 strain (Sabin-2). During 2017–2018, transmission of the HLO-1 emergence resulted in 26 additional cases notified in four additional HZs in Haut Lomami, three HZs in Tanganyika, and one HZ in each Haut Katanga and Ituri. The onset of paralysis for the most recent AFP case with genetically linked virus was in May 2018.

2017 DRC MAN-1: This emergence in Maniema province resulted in two AFP cases with paralysis onset in March (Kindu HZ) and April 2017 (Kunda HZ); the cVDPV2s isolated shared seven VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2 (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [8], [12], [13], [14].

2018 DRC-MON-1: This emergence was first detected in specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in April 2018 notified in Yamongili HZ (Mongala) (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [13], [14], [15]. The cVDPV2 isolated had 19 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2. Transmission of the DRC-MON-1 emergence resulted in ten additional cases notified in Bumba, Yamaluka, Yambuku, and Yamongili HZs (Mongala). The onset of paralysis for the most recent AFP case (Yamaluka HZ) with genetically linked virus was in September 2018.

2018 DRC-HKA-1: This emergence, detected in Haut Katanga province, resulted in two AFP cases notified in Mufunga-Sampwe HZ both with paralysis onset in October 2018; the viruses detected in specimens from one case-patient and from a direct contact of the second case-patient had seven/eight VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2 (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [14], [15]. No additional genetically linked viruses were detected after October 2018.

2019 DRC-KAS-1: This emergence resulted in one AFP case with paralysis onset in February 2019 in Kamonia HZ (Kasai) (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [15], [17]. The virus detected in the AFP case-patient’s stool had six VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2, and genetically linked virus was isolated from specimens of community contacts collected in March 2019. No additional genetically linked viruses were detected in DRC after March 2019; however, a genetically linked virus with 20 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2 was isolated from the specimen of an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in January 2021 in the Republic of the Congo (Niari district) [17].

2019 DRC-HLO-2: This emergence was first detected in specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in February 2019 notified in Malemba-Nkulu HZ (Haut Lomami) (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [15], [16], [17]. The cVDPV2 detected had eight VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2. During 2019, transmission of the DRC-HLO-2 emergence resulted in 19 additional cases notified in Malemba-Nkulu and in four additional HZ in Haut Lomami and one health zone in each of Tanganyika and Haut Katanga. The onset of paralysis for the most recent AFP case (Kinkondja HZ) with genetically linked virus was in October 2019.

2019 DRC-KAS-2: This emergence was first detected in specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in April 2019 notified in Kamonia HZ (Kasai) (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [15], [17]. The cVDPV2s detected had six/seven VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2. During the following months, transmission resulted in two and one additional case(s) in Kamonia and Kalonda-Ouest HZs (Kasai), respectively. The onset of paralysis for the most recent AFP case (Kalonda-Ouest HZ) with genetically linked virus was in June 2019.

2019 DRC-SAN-1: This emergence was first detected in the specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in April 2019 notified in Wembo-Nyama HZ (Sankuru) (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [15], [16], [17]. The cVDPV detected had six VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2. The outbreak resulted in 31 additional cases in seven additional HZ in Sankuru. The onset of paralysis for the most recent AFP case (Bena-Dibele HZ) with genetically linked virus was in November 2019.

2019 DRC-TPA-1: This emergence resulted in one AFP case in Lingomo HZ (Tshuapa) with paralysis onset in May 2019 (Fig. 2A, Table 2) [15], [17]. The case was confirmed after the isolation of the DRC-TPA-1 virus from a direct contact. Genetically linked virus was isolated from the specimen of a community contact. The cVDPV2 detected in the contacts’ specimens had seven/ten VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2. No additional genetically linked viruses were detected after August 2019.

2019 DRC-KAS-3: This emergence was first detected in the specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in June 2019 notified in Kalonda-Ouest HZ (Kasai) (Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B, Table 2) [15], [16], [17]. The cVDPV2 detected had eight VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2. Further transmission resulted in 100 additional AFP cases in 41 additional HZs in 10 provinces overall; additionally, genetically linked virus was isolated from an environmental sample collected in Limité HZ (Kinshasa) in May 2020 (Fig. 2B, Table 1, Table 2). The most recent AFP case (Lisala HZ, Mongala) with genetically linked virus had paralysis onset in April 2021.

2020 DRC-EQT-1: This emergence resulted in one AFP case with paralysis onset in July 2020 in Bolomba HZ (Equateur) (Fig. 2B, Table 2) [17]. The virus detected had six VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2, and genetically linked virus was isolated from specimens of several community contacts. No additional genetically linked viruses were detected after September 2020.

2020 DRC-TPA-2: This emergence was detected in specimens collected from community contacts of an AFP case-patient (but not in the AFP case-patient’s specimens) in Boende HZ (Tshuapa) in May 2020 (Table 2) [17]. The cVDPV2 detected had six/seven VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2. Genetically linked virus was not detected after May 2020.

2021 DRC-MAN-2: This emergence was first detected for an AFP case with paralysis onset in June 2021 notified in Kailo HZ (Maniema) (Fig. 2B, Table 2) [17]. The virus isolated had seven VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2, and genetically linked virus was isolated from specimens of community contacts collected during August 2021. Transmission of DRC-MAN-2 continued into 2022.

2021 DRC-MAN-3: This emergence was first detected in an ES sample collected in Kindu HZ (Maniema) in October 2021 (Fig. 2B, Table 1, Table 2). The virus isolated had 12 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2, and genetically linked virus was isolated from a second ES site in Kindu HZ and from the specimens of 14 AFP case-patients with paralysis onset during October-December 2021 that were notified in seven HZs in Maniema (Fig. 2B, Table 1, Table 2). Transmission of DRC-MAN-3 continued into 2022.

2021 DRC-MAN-4: This emergence was first detected in the specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in November 2021 notified in Alunguli HZ (Maniema). The virus isolated had 11 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2, and genetically linked virus was isolated from an ES sample collected in Kindu HZ in December 2021 (Fig. 2B, Table 1, Table 2). Transmission of DRC-MAN-4 continued into 2022.

2021 DRC-MAN-5: This emergence was first detected in the specimens from an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in October 2021 notified in Punia HZ (Maniema). The virus isolated had 12 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2, and genetically linked virus was isolated from additional AFP cases with paralysis onset in 2022. (Fig. 2B, Table 2). Transmission of DRC-MAN-5 continued into 2022.

3.3. cVDPV2 transmission in DRC related to outbreaks first detected in other countries, by country of origin

Angola: Virus genetically linked to the ANG-LUA-1 cVDPV2 emergence, first detected in Angola during semester 2, 2019, was isolated from the specimens of an AFP case-patient with paralysis onset in September 2019 notified in Popokabaka HZ (Kwango) (Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B, Table 2) [16], [17]. Thirteen additional Congolese AFP cases with genetically linked cVDPV2 were subsequently notified in Popokabaka and in three additional health zones (in three additional provinces): Kimvula (Kongo Central), Matete (Kinshasa), and Mokala (Kwilu). The most recent AFP case in DRC (Mokala HZ) with virus genetically linked to the ANG-LUA-1 cVDPV2 emergence had paralysis onset in January 2020. The ANG-LNO-2 cVDPV2 emergence, first detected in Angola during semester 2, 2019, was isolated from the specimens of a single Congolese AFP case-patient (paralysis onset February 2020) notified in Tembo HZ (Kwango) (Fig. 2B, Table 2) [17]. No additional viruses genetically linked to the ANG-LNO-2 cVDPV2 emergence were detected in DRC.

Central African Republic (CAR): Virus genetically linked to the CAR-BNG-1 cVDPV2 emergence, first detected in CAR during semester 2, 2019, was isolated from the specimens, collected in October 2020, of two direct contacts of an AFP case-patient in Banjow Moke HZ (Maindombe). That AFP case had genetically linked DRC-KAS-3 cVDPV2 virus isolated and thus is included in the case count for DRC-KAS-3 and not CAR-BNG-1 (Table 2). No subsequent detections of the CAR-BNG-1 occurred in DRC (Table 2) [17].

3.4. cVDPV2 outbreak response SIAs

Considering risk analyses prepared by DRC’s polio eradication partners, the Advisory Group on mOPV2 Provision recommended to the WHO Director-General the release of mOPV2 for DRC’s cVDPV2 outbreak response SIAs during 2017–2021 [26]. SIA HZs were those where cVDPV2 cases were notified and neighboring HZs at risk for importation and circulation of the cVDPV2 due to proximity, transportation routes, sub-optimal poliovirus immunity, history of VDPV2 emergence and transmission, poor AFP surveillance performance, etc. (Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B, Fig. 3; Table 2, Table 3) [6], [8], [24], [26], [12], [13], [14]. Because of simultaneous cVDPV2 outbreaks in numerous provinces by quarter 2, 2018 and assumed low poliovirus type 2 immunity throughout DRC, two large scale mOPV2 SIAs were conducted in 16 provinces, excepting Ebola Viral Disease (EVD)-affected HZs, during quarter 3 and 4, 2018 [6], [24]. In response to ANG-LUA-1 circulation in Zambia in 2019, one mOPV2 SIA was conducted in three HZs in Haut Katanga and one HZ in Tanganyika in December 2019 [6], [16], [24].

Table 3.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Monovalent oral poliovirus vaccine Sabin-strain serotype 2 (mOPV2) Supplemental Immunization Activities (SIAs) conducted in response to circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus serotype 2 (cVDPV2) outbreaks, by emergence targeted or covered, dates conducted, and geographic areas, June 2017–April 2021.

| cVDPV2 emergence targeted or covered | mOPV2 SIA Start Date End Date | Province (number of health zones) Provinces in bold are those where all health zones were included in the respective SIA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRC-HLO-1/DRC-MAN-1 |

27 Jun 2017 | 29 Jun 2017 | Haut Katanga (2), Haut Lomami (8), Lualaba (2), Maniema (8) |

| 13 Jul 2017 20 Jul 2017 |

15 Jul 2017 22 Jul 2017 |

Haut Katanga (2), Haut Lomami (8), Lualaba (2), Maniema (8) | |

| 14 Sep 2017 | 16 Sep 2017 | Haut Katanga (1), Haut Lomami (1), Maniema (1), mop-up | |

| DRC-HLO-1 |

30 Nov 2017 | 2 Dec 2017 | Haut Katanga (2), Haut Lomami (13), Lualaba (2), Tanganyika (3) |

| 16 Dec 2017 | 18 Dec 2017 | Haut Katanga (2), Haut Lomami (13), Lualaba (2), Tanganyika (3) | |

| 26 Apr 2018 | 28 Apr 2018 | Haut Katanga (4), Haut Lomami (16), Lomami (3), Tanganyika (11) | |

| 4 May 2018 | 6 May 2018 | Haut Katanga (9), Lualaba (5) | |

| 26 Jun 2018 | 28 Jun 2018 | Haut Katanga (27), Haut Lomami (16), Lomami (3), Lualaba (14), Tanganyika (11) | |

| DRC-MON-1 | 7 Jul 2018 | 12 Jul 2018 | Bas Uele (2), Mongala (6), Nord Ubangi (2), Tshopo (3) |

| DRC-HLO-1 | 30 Jul 2018 | 1 Aug 2018 | Ituri (8) |

| DRC-MON-1 | 30 Aug 2018 | 1 Sep 2018 | Bas Uele (11), Haut Uele (13), Ituri (35), Mongala (12), Nord Kivu (27), Nord Ubangi (11), Sud Kivu (34), Sud Ubangi (16), Tshopo (23) |

| 13 Sep 2018 | 15 Sep 2018 | Bas Uele (11), Haut Uele (13), Ituri (35), Mongala (12), Nord Kivu (26), Nord Ubangi (11), Sud Kivu (34), Sud Ubangi (16), Tshopo (23) | |

| DRC-HLO-1 |

27 Sep 2018 | 29 Sep 2018 | Haut Katanga (27), Haut Lomami (16), Kasai Oriental (19), Lomami (16), Lualaba (14), Maniema (18), Tanganyika (11) |

| 11 Oct 2018 | 13 Oct 2018 | Haut Katanga (27), Haut Lomami (16), Kasai Oriental (19), Lomami (16), Lualaba (14), Maniema (18), Tanganyika (11) | |

| DRC-MON-1 | 10 Dec 2018 | 12 Dec 2018 | Bas Uele (2), Mongala (8), Nord Ubangi (2), Tshopo (3) |

| DRC-HKA-1 | 31 Jan 2019 | 2 Feb 2019 | Haut Katanga (5), Haut Lomami (2), Lualaba (2) |

| DRC-KAS-1/DRC-KAS-2/DRC-KAS-3 |

9 May 2019 | 11 May 2019 | Kasai (7) |

| 21 Jun 2019 | 23 Jun 2019 | Kasai (11), Kasai Central (6) | |

| 12 Jul 2019 | 14 Jul 2019 | Kasai (11), Kasai Central (6) | |

| DRC-SAN-1 |

19 Jul 2019 | 21 Jul 2019 | Maniema (1), Sankuru (10) |

| 22 Aug 2019 | 24 Aug 2019 | Maniema (1), Sankuru (10) | |

| DRC-HLO-2 | 22 Aug 2019 | 24 Aug 2019 | Haut Lomami (5) |

| DRC-TPA-1 | 26 Sep 2019 | 28 Sep 2019 | Mongala (2), Tshopo (1), Tshuapa (4) |

| DRC-HLO-2 | 26 Sep 2019 | 28 Sep 2019 | Haut Katanga (5), Haut Lomami (7), Tanganyika (3) |

| DRC-TPA-1 | 24 Oct 2019 | 26 Oct 2019 | Mongala (2), Tshopo (1), Tshuapa (4) |

| DRC-HLO-2 | 17 Oct 2019 | 19 Oct 2019 | Haut Katanga (5), Haut Lomami (7), Tanganyika (3) |

| DRC-SAN-1 |

14 Nov 2019 | 16 Nov 2019 | Kasai (3), Kasai Central (1), Sankuru (8), Tshuapa (1) |

| 28 Nov 2019 | 30 Nov 2019 | Kasai (3), Kasai Central (1), Sankuru (8), Tshuapa (1) | |

| ANG-LUA-1 (response to ANG-LUA-1 circulation, Zambia) | 12 Dec 2019 | 14 Dec 2019 | Haut Katanga (3), Tanganyika (1) |

| DRC-KAS-3/ANG-LUA-1/ANG-LNO-2 |

6 Feb 2020 | 8 Feb 2020 | Kasai (4), Kasai Central (19), Kongo Central (31), Kwango (14), Kwilu (24) |

| 20 Feb 2020 | 22 Feb 2020 | Kasai (4), Kasai Central (19), Kongo Central (31), Kwango (14), Kwilu (24) | |

| DRC-KAS-3/CAR-BNG-1 |

15 Oct 2020 | 17 Oct 2020 | Kinshasa (35), Maindombe (14), Tshopo (23) |

| 29 Oct 2020 | 31 Oct 2020 | Kinshasa (35), Maindombe (14), Tshopo (23) | |

| DRC-KAS-3/DRC-EQT-1/DRC-TPA-2 |

10 Dec 2020 | 12 Dec 2020 | Equateur (18), Tshuapa (12) |

| 24 Dec 2020 28 Dec 2020 |

26 Dec 2020 30 Dec 2020 |

Equateur (18), Tshuapa (12) | |

| DRC-KAS-3 | 28 Jan 2021 | 30 Jan 2021 | Kinshasa (5), mop-up |

| 25 Mar 2021 | 27 Mar 2021 | Mongala (12), Nord Ubangi (11), Sud Ubangi (16) | |

| 8 Apr 2021 | 10 Apr 2021 | Mongala (12), Nord Ubangi (11), Sud Ubangi (16) | |

4. Discussion

Through 2021, all cVDPVs detected in DRC were serotype 2 [7], [8], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. During January 1, 2017–December 31, 2021,viruses genetically linked to 19 cVDPV2 outbreaks were detected in DRC. Seventeen of the 19 outbreaks (including two first detected in Angola) resulted in 235 cases of paralysis notified in 84 HZs in 18 of DRC’s 26 provinces [8], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. An 18th cVDPV2 outbreak (DRC-TPA-2) occurred among a group of healthy children and a 19th outbreak, first identified in CAR (CAR-BNG-1), was identified among direct contacts of an AFP case; however, no genetically linked virus was isolated from specimens of the associated AFP case-patients [17]. In three of the four cVDPV2 outbreaks occurring during 2017–2018, cases were notified in Haut Katanga, Haut Lomami, Maniema, and Tanganyika provinces, a geography with a history of cVDPV2 outbreaks during 2005–2012 [1], [7], [8]. Ten of the 15 cVDPV2 outbreaks in circulation in DRC during 2019–2021 were first detected in provinces outside of this southeastern geography [13], [14], [15], [16], [17].

From the extent of VP1 divergence from Sabin-2 strain of viruses of the DRC-HLO-1, DRC-MAN-1, and DRC-MON-1 cVDPV2 outbreaks (first detected during 2017-April 2018), the estimated originating dates for these emergences were during 2015–2016 (before or inadvertently just after the April 2016 global tOPV to bOPV1,3 switch) from tOPV administered through EI or SIAs, the primary OPV used in DRC during those years [6]. With national OPV3 coverage overall low, long-standing poor EI and SIA vaccination coverage among the target populations within specific communities of those provinces likely led to conditions quite conducive to VDPV2 emergence. The first virus detected in the DRC-MAN-1 cVDPV2 emergence had seven VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2 indicating emergence and circulation for less than one year before detection [8]. In contrast, the first viruses detected in the DRC-HLO-1 and DRC-MON-1 emergences had 15–19 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2 indicating emergence and circulation for much more than one year before detection [8]. These three outbreaks were declared closed by WHO-AFRO in December 2019 [6]. It is noteworthy that ten large-scale mOPV2 SIAs were conducted in the core DRC-HLO-1 cVDPV2 outbreak provinces (Haut Katanga, Haut Lomami, and Tanganyika) during 2017–2018 before that outbreak was confidently controlled. While revisits to unvaccinated children, Independent Monitoring, Lot Quality Assurance Sampling surveys, and post-SIA “mop-up” vaccination were strategies recommended for every SIA, there are three lines of evidence suggesting that these SIAs were not of sufficient quality to quickly increase poliovirus type 2 immunity during 2017–2018. First, the approximately 15-month duration of the DRC-HLO-1 outbreak; second, a sero-survey conducted in Haut Lomami in March/April 2018 in HZs having had four/five rounds of mOPV2 SIAs found < 60 % type 2 seropositivity in children 6–23 months of age; and third, two new cVDPV2 emergences (DRC-HKA-1 and DRC-HLO-2) were detected in this geography in semester 2, 2018 and semester 1, 2019. [15], [26], [27].

Genetic analyses of the 13 cVDPV2 emergences first detected in DRC during and after semester 2, 2018 estimated the timing of starting VDPV2 emergence during 2018 or later, after DRC’s mOPV2 outbreak responses began [6], [8], [24], [12], [13], [14]. Of note, no countries neighboring DRC used mOPV2 during 2016–semester 1, 2019 [25], [28]. Angola’s and CAR’s use of mOPV2 began in June and October 2019, respectively, after their first cVDPV2 outbreaks were confirmed [28], [15], [16], [17]. No post-switch tOPV use was discovered in DRC that could account for these VDPV2 emergences. These 13 distinct cVDPV2 emergences appear to have been “seeded” from mOPV2 used in DRC’s various outbreak response SIAs, and each had <=12 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin- 2 upon detection, indicating more timely detection through AFP surveillance than outbreaks confirmed in 2017-mid-2018. Outbreaks of the emergences of DRC-KAS-1, DRC-KAS-2, DRC-SAN-1, DRC-TPA-1, DRC-KAS-3, DRC-EQT-1, and DRC-TPA-2 were first detected in 2019/2020 outside of the zone where DRC’s mOPV2 SIAs were conducted in 2017/2018 [6], [24]. DRC-MAN-2, DRC-MAN-3, DRC-MAN-4, and DRC-MAN-5 were first detected in semester 2, 2021 in Maniema province; mOPV2 had been used most recently in Maniema in August 2019 and in contiguous provinces in December 2019. These four Maniema cVDVP2 emergences had a range of 7–12 VP1 nucleotide differences from Sabin-2 when first detected indicating emergence about 10–15 months prior. This indicates that the potential start of emergence from Sabin-2 in 2020 could have been from inadvertent use of mOPV2 or other exposure to Sabin-2 after outbreak SIAs. In any case, carefully examining all local cold stores is needed to ensure that mOPV2 vaccine is not retained after SIAs.

The cumulative magnitude and geographic expanse of these 13 emergence outbreaks, particularly DRC-SAN-1 and DRC-KAS-3, revealed deeply and chronic suboptimal poliovirus type 2 population immunity throughout DRC [15], [16], [17]. There were 101 cases of paralysis linked to the DRC-KAS-3 cVDPV2 emergence in a total of 10 provinces and 32 cases of paralysis linked to the DRC-SAN-1 cVDPV2 emergence in Sankuru. In addition, 14 AFP cases with cVDPV2 genetically linked to the Angolan ANG-LUA-1 cVDPV2 emergence were detected in four provinces. The 2019/2020 cVDPV2 circulation (DRC-KAS-3 and ANG-LUA-1) detected in Kinshasa city, a metropolitan area with an estimated 17 million inhabitants, did not result in a large outbreak. Technical support was deployed to the city’s high-risk HZ in early 2020 to ensure active and sensitive AFP surveillance; outbreak responses were apparently adequate despite delayed implementation due to suspension of polio SIAs in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic [16]. It is assumed that if there had been a large outbreak of sudden paralysis among children, it would have detected and reported to the health system through surveillance or by the population.

Four of the 2018–2019 outbreaks (DRC-HKA-1, DRC-KAS-1, DRC-KAS-2, and DRC-TPA-1) were declared closed by WHO-AFRO in October 2020 [6]. The four 2020 outbreaks plus the three outbreaks associated with imported emergence groups (DRC-HLO-2, DRC-SAN-1, DRC-TPA-2, DRC-EQT-1, ANG-LUA-1, ANG-LNO-2, and CAF-BNG-1) were declared closed by WHO-AFRO in May 2022 [6]. Virus genetically linked to the 2019 DRC-KAS-3 cVDPV2 emergence was last detected in April 2021 [26]. Thus, the 2019–2021 mOPV2 response SIAs were successful in interrupting the transmission of these 12 cVDPV2 outbreaks in DRC. Viruses genetically linked to all 2021 emergences were detected in 2022. Novel OPV2 vaccine (nOPV2), designed to have greater genetic stability than mOPV2 Sabin-strain, was introduced in DRC for cVDPV2 outbreak response SIAs in May 2022 [16], [17].

DRC had several experiences during the reporting period with transmission across international borders. cVDPV2 genetically linked to DRC-KAS-1 was isolated from a specimen collected from a child with a case of AFP (paralysis onset in January 2021) in the Republic of the Congo, approximately two years after the latest detection of DRC-KAS-1 in DRC, undetected by AFP surveillance in either country until that time [17]. This was the only detection of a DRC cVDPV2 emergence group outside of DRC through 2021. In contrast, Angola’s ANG-LUA-1 and ANG-LNO-2 cVDPV2 emergences circulated in DRC during 2019–2020 resulting in 15 cases of paralysis [16], [17]. Virus genetically linked to the CAR-BNG-1 emergence was detected in DRC in specimens, collected in October 2020, of two direct contacts of an AFP case-patient in Maindombe, DRC [17]. It is possible that the four cVDPV2 emergences detected through May 2019 in regions of CAR bordering DRC’s northern provinces were seeded from mOPV2 used in DRC [28], [15], [16], [17].

In 2018, DRC formalized the systematic collection of stool samples from direct contacts of AFP cases whose stools were “inadequate” (collected > 14 days after paralysis onset or were judged to be in poor condition upon arrival at the national laboratory) and from healthy children in communities near to that of certain VDPV2-positive AFP cases to confirm community circulation [18], [20]. Specimens from these sources were useful for confirmation of several cVDPV2 cases and outbreaks during the reporting period; this systematic contact specimen collection remains among DRC’s AFP surveillance activities [18], [20]. Undetected prolonged cVDPV2 circulation has not been apparent since 2018.

During the reporting period, ES for polioviruses was expanded from 6 sites in 3 provinces in quarter 3, 2017 to 20 sites in eight provinces by end 2021 [6]. Virus genetically to the DRC-KAS-3 cVDPV2 emergence was detected in one environmental sample collected in Limité HZ (Kinshasa) in 2020. ES was instrumental in detecting the DRC-MAN-3 cVDPV2 emergence in Maniema province before detection in specimens of AFP case-patients. A formal review of DRC’s poliovirus ES system could be useful for optimizing its effectiveness and guiding expansion to additional sites and cities [21].

During February-March 2018, DRC’s Minister of Health declared the cVDPV2 outbreaks a national public health emergency and established the polio COUP with a National Coordinator [24]. Simultaneously, polio eradication partners appointed a GPEI Coordinator as liaison to the COUP to facilitate coordination. Provincial COUPs were established in certain outbreak provinces [24]. The COUP and GPEI coordination continue to lead DRC’s cVDPV2 outbreak responses. The coordinators have had direct channels of communication with DRC’s Minister of Health and GPEI partner country representatives facilitating the endorsement of response plans, receipt of financial and material resources, and distribution of resources to implementing HZs.

DRC is continually combatting serious, concurrent health emergences and facing challenges with the delivery of health services [29]. The 2018–2020 EVD outbreaks delayed investigations of AFP cases (including certain ones confirmed as VDPV2-positive), implementation of cVDPV2 outbreak response SIAs, and the deployment of technical support for AFP surveillance [29]. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic delayed AFP case specimen transport and the conduct of the 2020 DRC-KAS-3 outbreak response SIAs planned for Kinshasa, Maindombe, and Tshopo provinces leading to the outbreak’s expanded geographic spread and magnitude into 2021 [16]. The COUP’s role in managing and coordinating the responses to concurrent and geographically scattered cVDPV2 outbreaks aided the Expanded Program on Immunization that was simultaneously responding to EVD and COVID-19, among other health emergencies [29]. Moreover, the COUP participated in detailed analyses conducted to determine the HZs at greatest need for the hundreds of thousands of person-hours of technical support provided for outbreak response and AFP surveillance by consultants during 2017–2021 [6], [24].

The African continent was declared free of indigenous WPV transmission in 2020 [30]. DRC was successful in interrupting WPV and cVDPV2 transmission in the past and interrupted the transmission of cVDPV2s that emerged and circulated during 2017–early 2021 [8]. However, the country has been recently plagued by new cVDPV2 emergence and circulation. nOPV2 SIAs were conducted in numerous of DRC’s provinces during 2022, and additional SIAs are planned in 2023, hopefully increasing type 2 mucosal immunity with a reduced risk for VDPV2 emergence. These efforts need be carefully planned and supported to reach the populations at risk. DRC needs the support of polio eradication and Essential Immunization (EI) partners to accelerate the country’s ongoing initiatives for EI strengthening, such as the Mashako Plan (an emergency plan to revitalize EI). Prompt introduction of a second dose of IPV would help increase protection from paralysis. If additional nOPV2 SIAs cannot be conducted promptly, consideration should be given to IPV SIAs in high-risk health zones [31]. DRC’s AFP surveillance system, despite challenges, has sustained the capacity to detect poliovirus circulation over decades with variable success in promptness; the system will continue to require partner support to ensure prompt VDPV detection, particularly in geographies historically susceptible to VDPV emergence and subsequent transmission; administration of mOPV2 in 2020–2021 could have seeded the emergence of yet undetected VDPV2s [4], [24], [6], [7], [8], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. The system would benefit from analyses and actions to ensure eventual growth to integrated surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Active AFP surveillance visits to health facilities should be conducted at an increased frequency. While AFP cases with inadequate specimens represent surveillance weakness and their numbers should be reduced, collection of stool specimens from their direct contacts and timely classification of the AFP case should be prioritized; prompt field investigations around polio-compatible cases are necessary [19]. Consideration should be given to field investigations around clusters of AFP cases. Improving access to clean water and good hygienic practices in high-risk areas could ultimately reduce poliovirus transmission and decrease the prevalence of multiple enteric diseases [32].

5. Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and respective agencies.

6. Financial interest

The authors do not have a financial or proprietary interest in a product, method, or material or lack thereof.

7. Financial support

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Mary M. Alleman, Cara C. Burns, Elizabeth Henderson, Jaume Jorba).

Ministry of Public Health, Hygiene and Prevention, The Democratic Republic of the Congo (Anicet Mwehu, Yogolelo Riziki).

National Institute for Communicable Diseases, National Health Laboratory Services, (Lerato Seakamela, Wayne Howard).

World Health Organization, The Democratic Republic of the Congo (Albert Kadiobo Mbule, Renee Ntumbannji Nsamba, Kpandja Djawe, Moïse Désiré Yapi, Marcellin Nimpa Mengouo).

World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa (Nicksy Gumede, Anfumbom K.W. Kfutwah, Modjirom Ndoutabe).

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Kamel Senouci).

Previous presentation: None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mary M. Alleman: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Jaume Jorba: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Visualization. Yogolelo Riziki: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Elizabeth Henderson: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Anicet Mwehu: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Lerato Seakamela: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Wayne Howard: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Albert Mbule: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Renee Ntumbannji Nsamba: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Kpandja Djawe: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Moïse Désiré Yapi: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Marcellin Nimpa Mengouo: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Nicksy Gumede: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Modjirom Ndoutabe: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Anfumbom K.W. Kfutwah: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Kamel Senouci: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Cara C. Burns: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank staff of: partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative; the Polio and Picornavirus Laboratory of the Division of Viral Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, National Health Laboratory Services; and DRC’s Ministry of Public Health, Hygiene and Prevention (especially the Emergency Operations Center for Polio) and community members in DRC for their tireless efforts in implementing polio eradication activities. The authors would like to extend a special remembrance to Dr. Pierre Kandolo Wenye, who promoted childhood vaccination in DRC for decades and served as coordinator of the DRC’s Emergency Operations Center for Polio until his death in 2022. The authors appreciate the review of earlier drafts of this manuscript by Drs. Eric Wiesen and Steve Wassilak.

Footnotes

This article was published as part of a supplement supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Global Immunization Division. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or World Health Organization or UNICEF or Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and are not attributable to the sponsors.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- 1.Burns C.C., Diop O.M., Sutter R.W., et al. Vaccine-derived polioviruses. J Infect Dis. 2022;2014(210):S283–S293. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage, WHO-UNICEF estimates of POL3 coverage. https://immunizationdata.who.int/listing.html?topic=coverage&location=. Accessed 1 February 2023.

- 3.UNICEF and World Health Organization. Democratic Republic of the Congo: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2021 revision. Democratic Republic of the Congo - UNICEF Data. Accessed 22 February 2023.

- 4.Alleman MM, Wannemuehler K, Weldon W, et al. Factors contributing to outbreaks of wild poliovirus type 1 infection involving persons aged ≥15 years in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2010–2011, informed by a pre-outbreak poliovirus immunity assessment. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:S62–73. https://doi.org /10.1093/infdis/jiu282. Accessed 2 June 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Voorman A., Hoff N.A., Doshi R.H., et al. Polio immunity and the impact of mass immunization campaigns in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Vaccine. 2017;35:5693–5699. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization, Democratic Republic of the Congo Country Office. Activités d’éradication de la poliomyélite (IEP), République Démocratique du Congo, weekly reports, 2010-2022. Available from the World Health Organization, Democratic Republic of the Congo Country Office.

- 7.Gumede N., Lentsoane O., Burns C.C., et al. Emergence of vaccine-derived polioviruses, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2004–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;2013(10):1583–1589. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alleman M.M., Chitale R., Burns C.C., et al. Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks and Events — Three Provinces, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:300–305. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6710a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hampton L.M., Farrell M., Ramirez-Gonzalez A., et al. Cessation of Trivalent Oral Poliovirus Vaccine and Introduction of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine — Worldwide, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:934–938. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6535a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grassly N.C. Immunogenicity and Effectiveness of Routine Immunization With 1 or 2 Doses of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2022;2014(210):S439–S446. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tevi-Benissan C., Okeibunor J., Maufras du Châtellier G., et al. Introduction of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine and Trivalent Oral Polio Vaccine/Bivalent Oral Polio Vaccine Switch in the African Region. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:S66–S75. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorba J., Diop O.M., Iber J., et al. Update on Vaccine-Derived Polioviruses — Worldwide, January 2016–June 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1185–1191. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6643a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorba J., Diop O.M.N., Iber J., et al. Update on Vaccine-Derived Polioviruses — Worldwide, January 2017–June 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1189–1194. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6742a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mbaeyi C., Alleman M.M., Ehrhardt D., et al. Update on Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks — Democratic Republic of the Congo and Horn of Africa, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:225–230. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6809a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorba J., Diop O.M., Iber J., et al. Update on vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks—worldwide, January 2018–June 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1024–1028. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alleman M.M., Jorba J., Greene S.A., et al. Update on vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks—worldwide, July 2019–February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:489–495. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6916a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alleman M.M., Jorba J., Henderson E., et al. Update on Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks — Worldwide, January 2020–June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1691–1699. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7049a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Public Health, Hygiene and Prevention, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fiche technique de surveillance des PFA, 27 février . Ministry of Public Health; Democratic Republic of the Congo: 2019. Available from the Expanded Programme on Immunization. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Acute flaccid paralysis surveillance field guide, January 2006. Available from the World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa.

- 20.World Health Organization, Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Global Polio Surveillance Action Plan, 2018-2020. https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GPEI-global-polio-surveillance-action-plan-2018-2020-EN-1.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2022.

- 21.World Health Organization, Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Guidelines on Environmental Surveillance for Detection of Polioviruses. https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GPLN_GuidelinesES_April2015.pdf. Accessed 22 February 2023.

- 22.Coulliette-Salmond A.D., Alleman M.M., Wilnique P., et al. Haïti Poliovirus Environmental Surveillance. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;101:1240–1248. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization, Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Reporting and classification of vaccine-derived polioviruses. https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/VDPV_ReportingClassification.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2022.

- 24.Ministry of Public Health, Hygiene and Prevention, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Various “Bulletin hebdomadaire de riposte à l’épidémie de PVDV2c en RDC” and “Compte Rendu de la réunion du Centre des Operations d'Urgence Polio (COUP, Emergency Operations Center-Polio)”. 2018-2021. Available from the Expanded Programme on Immunization, Ministry of Public Health, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- 25.Jorba J. Phylogenetic Analysis of Poliovirus Sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1387:227–237. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3292-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization, Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Standard Operating Procedures: Responding to a poliovirus event or outbreak - Version 3 (January 2019). https://reliefweb.int/report/world/standard-operating-procedures-responding-poliovirus-event-or-outbreak-version-3-january. Accessed 2 June 2022.

- 27.Okitolonda E, Rimoin A (Kinshasa School of Public Health and UCLA Fielding School of Public Health). Rapid vaccine coverage and linked biomarker survey, children 6-23 months Haut Lomami Province, Baseline Report 2018-2019. November 2019. Available from the Kinshasa School of Public Health, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- 28.Ministry of Public Health, Central African Republic. République Centrafricaine Rapport de Situation de la réponse aux cas de VDPV2. 2019. Available from the Expanded Programme on Immunization, Ministry of Public Health, Central African Republic.

- 29.World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin. 2017-2021. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/disease-outbreaks/outbreaks-and-other-emergencies-updates?utm_source=Newsweaver&utm_medium=email&utm_term=View%20archives%20of%20this%20update%20bulletin&utm_content=Tag%3AAFRO/WHE/HIM%20Outbreaks%20Weekly&utm_campaign=WHO%20AFRO%20-%20Outbreaks%20and%20Emergencies%20Bulletin%20-%20Week%2022/2022&page=5. Accessed 2 June 2022.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Africa Kicks Out Wild Polio. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/polio/why-it-matters/africa-kicks-out-wild-polio.htm. Accessed 2 June 2022.

- 31.Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance. Democratic Republic of Congo launches major vaccination drive. 2018. Accessed 2 June 2022.

- 32.UNICEF, Democratic Republic of Congo. Water, sanitation, and hygiene. 2021-2022. https://www.unicef.org/drcongo/en/what-we-do/water-sanitation-and-hygiene. Accessed 2 June 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.