Abstract

Background

Nursing care for patients with delirium is very complex and stressful and is associated with considerable care strain for nurses. Delirium recognition is the first step to the prevention and management of delirium and reduction of strain of care. Education is one of the strategies for improving nurses’ delirium recognition ability.

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of interactive E-learning on delirium recognition ability and delirium-related strain of care among critical care nurses.

Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted in 2019 using a two-group pretest-posttest design. Participants were 98 critical care nurses recruited through a census from two hospitals in Iran. They were non-randomly allocated to an intervention and a control group. Study intervention was an interactive E-learning program with four parts on delirium, its prevention, its treatment, and its diagnostic and screening procedures. The program was uploaded on a website and its link was provided to participants in the intervention group. Before and two months after the intervention, data were collected using the Strain of Care for Delirium Index and five case vignettes. For data analysis, the Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, independent-sample t, and paired-sample t tests were performed usingthe SPSS software (v. 16.0).

Findings

Groups did not significantly differ from each other regarding the pretest mean scores of delirium recognition ability and strain of care. After the intervention, the mean score of delirium recognition ability in the intervention group was significantly greater and the mean score of strain of care was significantly lower than the control group (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Interactive E-learning is effective in significantly improving critical care nurses’ delirium recognition ability and reducing their strain of care. As nurses’ heavy workload and limited free time are among the main barriers to their participation in face-to-face educational programs, interactive E-learning can be used for in-service education.

Keywords: E-learning, strain of care, delirium, recognition, nurse

Introduction

Delirium refers to altered consciousness and cognition with an acute onset and a fluctuating course. 1 Its prevalence in intensive care units (ICU) varies from 4% to 89%.2,3 Delirium is specifically prevalent among patients under mechanical ventilation so that more than 80% of these patients experience delirium.1,4,5

A study reported that delirium increased the length of hospital stay by 3.45 so that the length of hospital stay among patients with and without delirium was eleven and seven days, respectively. Moreover, delirium increased the risk of death by 2.43 times. 6

Nurses have critical role in care delivery to patients with delirium.7,8 However, care delivery to patients with delirium is difficult, burdensome, and frustrating for nurses, 9 significantly increases their workload, and hence, causes them severe stress, frustration, 7 fatigue, and bewilderment. 10 Studies show that nurses who provide care to patients with delirium experience moderate to high levels of stress.11–13 The challenging behaviors of patients with delirium also cause nurses distress and anxiety. 14 Moreover, fulfilling the unique needs of these patients’ and managing their problems face nurses with high levels of physical and mental stress, reduce their ability to recognize delirium, 10 and impose considerable strain of care on them.

Delirium recognition is the most important step to effective delirium management. 14 However, despite recent advances in the area of critical care, delirium is still under-recognized.15,16 Most nurses have limited delirium recognition ability and cannot recognize many cases of delirium. 17 Studies reported that nurses cannot accurately recognize delirium in 75% of cases. 18 A study showed that delirium recognition rate by healthcare providers in Iran was 13%. 19 Lack of knowledge about delirium and its screening methods is one of the factors contributing to its under-recognition20,21 and poor management. 22 A study in Iran reported that only 24.6% of nurses had adequate knowledge about delirium. 19 Two studies also reported that most healthcare providers had limited knowledge and skills for recognizing and managing delirium and highlighted that such lack of knowledge and skills can negatively affect patient outcome and nursing practice and increase nurses’ workload.2,23 Therefore, appropriate interventions are needed to improve delirium recognition knowledge and skills among healthcare providers, particularly ICU nurses.

Education is a potentially effective strategy for improving nurses’ delirium-related knowledge and their ability to recognize and manage delirium.7,14 Delirium-related educational programs for nurses improve delirium management and reduce nurses’ strain of care. 14 However, most nurses cannot attend these programs due to their busy work schedule, limited managerial and organizational support, and long distance between their workplace and place of education. 24 Accordingly, using electronic and portable educational strategies such as E-learning can overcome these barriers to education and satisfy learners’ different preferences and needs. 25

E-learning refers to different electronic technologies for education including web-based learning and mobile-based learning. 26 It can be an appropriate strategy for increasing learners’ access to educational materials without any time- and place-related limitation and hence, can reduce education-related costs and help professionals effectively balance their professional and personal needs. 27 E-learning can provide nurses with the opportunity to access the latest professional data. 28

Background

Interactive E-learning can increase healthcare providers’ professional skills. 2 Former studies reported that E-learning was effective in significantly enhancing nurses’ knowledge about medication administration and calculation, 29 rare diseases, 30 and palliative care, 31 developing their self-confidence for stress reduction in their relationships with patients, 32 and improving their professional skills.27,33 A study also showed that E-learning significantly improved nurses’ delirium recognition ability. 28 However, some studies showed that E-learning did not significantly improve nurses’ delirium recognition ability and did not significantly reduce their strain of care.2,23 A systematic review also showed no significant difference between the effects of E-learning and traditional teaching methods on nursing students’ and nurses’ knowledge, skills, and satisfaction. That study highlighted that the reviewed studies had different methodological limitations and hence, recommended further studies for evaluating the effects of E-learning. 34 Another review study on 52 studies published from 2007 to 2017 concluded that E-learning had positive effects and noted that due to the methodological limitations of the reviewed studies and the low validity and reliability of their outcome measures, further studies in different contexts would be needed. 35 On the other hand, most studies into the effects of E-learning were conducted in the area of medical education and in high-income countries 35 and hence, their results are not easily generalizable to low- and moderate-income countries. 36 The present study was conducted to address these gaps. The aim of the study was to evaluate the effects of interactive E-learning on delirium recognition ability and delirium-related strain of care among critical care nurses.

Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted in 2019 using a two-group pretest-posttest design.

Participants

Participants were 98 critical care nurses recruited to the study from four ICUs of two hospitals affiliated to Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran. Inclusion criteria were an ICU work experience of more than six months and the ability of working with computer. In order to minimize between-group information leakage, all nurses from one hospital were allocated to control group and all nurses from the other hospital were allocated to intervention group. Allocation was done through a draw lot. Blinding was not possible due to the characteristics of the study intervention.

Sample size was determined with a confidence level of 0.95, a power of 0.80, and the assumption that the mean score of strain of care in the intervention group should be at least 5 point greater than the control group to be considered statistically significant. As the total score of strain of care is 20–80 and its median is 50, 7 an effect size of 10% of the median (i.e., 5) was considered for sample size calculation. Accordingly, sample size per group was calculated to be 43. As 49 critical care nurses were working in each hospital of the study setting, all of them were recruited to the study through a census. Strain of care was used for sample size calculation due to its wider score range compared with delirium recognition ability.

Data collection

Data were collected using the Strain of Care for Delirium Index and five case vignettes. The Strain of Care for Delirium Index was used for assessing delirium-related strain of care among nurses. Introduced by Milisen and colleagues in 2004, this index has four subscales related to patients’ behavioral characteristics. These subscales are hypoactive behavior (three items), hypoalert behavior (four items), fluctuating course and psychoneurotic behavior (five items), and hyperactive/hyperalert behavior (eight items). These items assess the strain nurses experience while dealing with patients at any of the abovementioned status. Each item is scored on a four-point scale as follows: “Quite easy”: 1; “Easy”: 2; “Difficult”: 3; and “Quite difficult”: 4. The possible total score of the index is 20–80 and higher scores show greater strain of care. 7 Participants of the present study completed this index before and after the study intervention. The developers of the index reported that its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88. In the present study, twenty nurses twice completed the index with a one-week interval. Cronbach’s alpha and test-retest correlation coefficient were 0.793 and 0.783, respectively. These results indicated high internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire.

An instrument with five case vignettes for delirium was used for assessing nurses’ delirium recognition ability. Introduced in 2007, this instrument has five case vignettes for patients with dementia, hyperactive delirium, hypoactive delirium, hyperactive delirium superimposed on dementia, and hypoactive delirium superimposed on dementia. Each vignette contains complete information about the history and the symptoms of a patient followed by a question about the patient’s mental status and delirium type. Four case vignettes were used at pretest which were related to dementia, hyperactive delirium, hypoactive delirium, and hyperactive delirium superimposed on dementia. At the posttest, the hyperactive delirium superimposed on dementia was replaced with the hypoactive delirium superimposed on dementia. The possible answers to each case vignette are: “Dementia”, “Delirium”, “Delirium superimposed on dementia”, “Normal aging”, “Depression”, and “None”. Respondents recognize patient’s problem by selecting only one response. Accurate response is scored 1 and wrong response is scored zero. Therefore, the possible total score of this instrument is 0–4 and higher scores show greater delirium recognition ability. 37 For delirium recognition ability assessment in the present study, participants completed this instrument before and two months after the intervention onset. A former study reported that the Kappa coefficient of this instrument was 0.69. For reliability assessment, this instrument was twice completed by twenty nurses and then, Kuder-Richardson 21 coefficient for internal consistency and test-retest correlation coefficient for stability were calculated to be 0.78 and 0.877, respectively. These twenty nurses were not included in the final analysis. These results indicated high internal consistency and reliability of the instrument.

Intervention

Study intervention was an interactive E-learning program developed using relevant clinical guidelines and articles and prepared using the Storyline software (v. 3.0). The E-learning program consisted of four main parts, namely a sixteen-minute part on delirium, its definition, characteristics, and types, a twenty-minute part on the prevention and the risk factors of delirium, a twenty-minute part on delirium treatment, and a 22-minute part on delirium diagnostic and screening procedures. The program included texts, pictures, sound clips, and items for evaluation. After watching and reading the content of the program, participants in the intervention group answered the items of each part and then, they were provided with necessary feedback. They had the opportunity to repeat the test. The content validity of the E-learning program was assessed by a panel of experts consisted of nursing faculty members and critical care specialists. As participants were not familiar with interactive E-learning, a thirty-minute face-to-face educational session was held for those in the intervention group before the intervention in order to instruct them how to use the interactive E-learning program. Then, the E-learning program was uploaded on the website of one of the hospitals of the study setting and its link was provided to participants in the intervention group. They could access the program for two months. Every two weeks during the study intervention, a message was sent to participants in the intervention group through the WhatsApp mobile application to remind and motivate them for using the program. Participants in the control group received routine educations during the study and the E-learning program after the study. All participants were awarded a certificate of participation in the delirium recognition E-learning program. Posttest assessments of strain of care and delirium recognition ability were performed two months after the intervention onset.

Data analysis

The SPSS software (v. 16.0) was used for data analysis. Between-group comparisons respecting categorical and numerical variables were made through the Chi-square (or the Fisher’s exact) and the independent-sample t tests, respectively. Within-group comparisons were made through the paired-sample t test. The level of significance was set at less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, approved this study (code: IR.IUMS.REC.1397.760). Necessary permissions for the study were also obtained from the Research and Technology Administration of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran. We provided participants with clear explanations about the study aim and methods and asked them to complete the written informed consent form of the study.

Findings

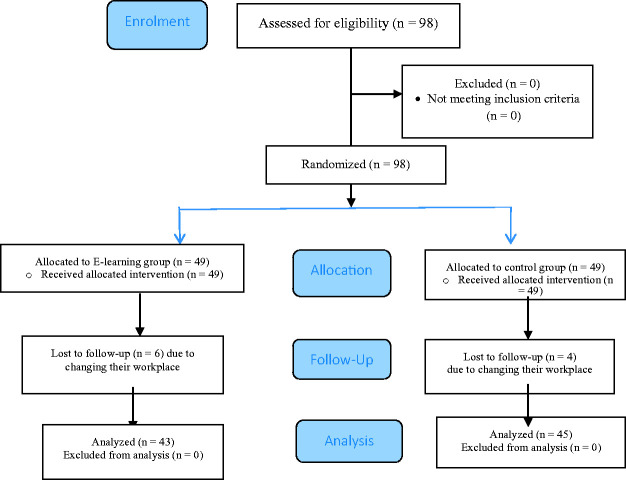

Six participants from the intervention and four from the control group were excluded because they changed their workplace during the study. Finally, data obtained from 88 nurses were analyzed (Figure 1). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups respecting participants’ demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of the study.

Table 1.

Between-group comparisons regarding participants’ characteristics.

| GroupCharacteristics | Intervention | Control | Test results |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 8 (18.6) | 7 (15.6) | χ2 = 0.145; DF = 1P = 0.704 |

| Female | 35 (81.4) | 38 (84.4) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 30.88 ± 4.90 | 31.40 ± 5.71 | t = 0.454; DF = 86P = 0.651 |

| Range | 24–47 | 24–46 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 11 (25.6) | 20 (44.4) | χ2 = 3.429; DF = 1P = 0.064 |

| Married | 32 (74.4) | 25 (55.6) | |

| Clinical work experience (years) | |||

| Mean±SD | 6.64 ± 4.70 | 6.53 ± 5.25 | t = 0.096; DF = 86P = 0.923 |

| Range | 0.66–24 | 1–20 | |

| ICU work experience (years) | |||

| Mean±SD | 4.03 ± 2.44 | 4.25 ± 4.16 | t = 0.304; DF = 71.6P = 0.762 |

| Range | 0.66–10 | 0.5–15 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Permanent official | 19 (44.2) | 9 (20.0) | χ2 = 6.876; DF = 3P = 0.076 |

| Conditional official | 8 (18.6) | 14 (31.1) | |

| Post-graduation service | 11 (25.6) | 12 (26.7) | |

| Other | 5 (11.6) | 10 (22.2) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Bachelor’s | 42 (97.7) | 44 (97.8) | P = 1.000 |

| Master’s | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.2) | |

| History of receiving delirium-related education | |||

| Yes | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.4) | p = 0.365 |

| No | 41 (95.3) | 43 (95.6) |

The pretest mean score of delirium recognition ability in the intervention and the control groups was respectively 1.86 ± 1.21 and 1.53 ± 0.81 and the between-group difference was not significant (P = 0.142). After the intervention, the mean score of delirium recognition ability was 2.95 ± 1.04 in the intervention group and 1.88 ± 0.91 in the control group and the between-group difference was significant (P < 0.001). The mean score of delirium recognition ability in the intervention group significantly increased after the intervention (P < 0.001), while the mean score of delirium recognition ability in the control group did not significantly change (P = 0.055). Moreover, the amount of pretest-posttest change in the mean score of delirium recognition ability in the intervention group was significantly greater than the control group (P = 0.02). The effect size of the study intervention respecting delirium recognition ability was 1.09 (95% confidence interval: 0.64 to 1.54; Table 2), denoting the significant effects of the study intervention on nurses’ delirium recognition ability.

Table 2.

Within- and between-group comparisons respecting nurses’ delirium recognition ability.

| GroupTime |

Control |

Intervention |

Test resultsa | Effect size(95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | |||

| Before | 0–3 | 1.53 ± 0.81 | 0–4 | 1.86 ± 1.21 | t = 1.484; DF = 73.27P = 0.142 | 1.09 (0.64 to 1.54) |

| After | 0–3 | 1.88 ± 0.91 | 0–4 | 2.95 ± 1.04 | t = 5.102; DF = 86P < 0.001 | |

| Test resultsb | t = 1.973; DF = 44P = 0.055 | t = 4.247; DF = 42P < 0.001 | —— | |||

| Pretest-posttest mean difference | 0.35 ± 1.21 | 1.09 ± 1.68 | t = 2.365; DF = 86P = 0.02 | |||

aThe results of the independent-sample t test.

bThe results of the paired-sample t test.

The pretest mean score of strain of care was 58.0 ± 9.22 in the intervention group and 55.02 ± 9.77 in the control group and the between-group difference was not significant (P = 0.146). After the intervention, these values changed to 52.0 ± 10.91 and 58.97 ± 8.28, respectively. The posttest mean scores of strain of care and all its subscales in the intervention group were significantly less than the control group (P < 0.05). Within-group comparisons showed that except for the mean score of the hyperactive/hyperalert behavior subscale (P > 0.05), the mean scores of strain of care and all its other subscales significantly increased in the control group and significantly decreased in the intervention group (P = 0.05). The amount of pretest-posttest change in the mean scores of strain of care and all its subscales in the intervention group was significantly greater than the control group (P = 0.02). The effect size of the study intervention regarding strain of care was –3.67 (95% confidence interval: –4.36 to –2.99), indicating the large effects of the study intervention on strain of care (Table 3).

Table 3.

Within- and between-group comparisons respecting nurses’ strain of care.

| Strain of care | GroupTime |

Control |

Intervention |

Test resultsa | Effect size(95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Hypoactivebehavior | Before | 3–10 | 7.31 ± 1.63 | 4–10 | 7.88 ± 1.31 | t = 1.806; DF = 86 P = 0.074 | –0.5 (–0.93 to –0.08) |

| After | 5–10 | 7.95 ± 1.24 | 3–10 | 7.06 ± 2.15 | t = 2.349 DF = 66.53P = 0.022 | ||

| Test resultsb | t = 2.32; DF = 44P = 0.025 | t = 2.419; DF= 44 P = 0.020 | |||||

| Mean difference | 0.64 ± 1.86 | –0.81 ± 2.21 | t = 3.357; DF = 86 P = 0.001 | ||||

| Hypoalert behavior | Before | 4–14 | 10.06 ± 2.16 | 4–14 | 10.95 ± 2.26 | t = 1.885; DF = 86 P = 0.063 | –0.59 (–1.02 to –0.16) |

| After | 6–14 | 10.68 ± 2.02 | 4–14 | 9.65 ± 2.04 | t = 2.798; DF = 86 P = 0.006 | ||

| Test resultsb | t = 2.804; DF= 44 P = 0.007 | t = 3.325; DF = 42 P = 0.002 | |||||

| Mean difference | 0.80 ± 1.91 | –1.30 ± 2.56 | t = 4.367; DF = 86 p < 0.001 | ||||

| Fluctuating course | Before | 6–18 | 13.28 ± 2.85 | 6–18 | 14.11 ± 2.60 | t = 1.418; DF = 86 p = 0.160 | –0.82 (–1.26 to –0.39) |

| After | 9–19 | 14.40 ± 2.32 | 5–19 | 11.79 ± 3.83 | t = 3.833; DF = 68.64 P < 0.001 | ||

| Test resultsb | t = 2.423; DF = 44 p = 0.020 | t = 3.535; DF = 42 P = 0.001 | |||||

| Mean difference | 1.11 ± 3.07 | –2.32 ± 4.13 | t = 4.318; DF = 86 P < 0.001 | ||||

| Hyperactive/hyperalert behavior | Before | 10–32 | 24.35 ± 5.87 | 9–32 | 25.04 ± 5.05 | t = 0.596; DF = 86 P = 0.553 | 0.5 (–0.93 to –0.08) |

| After | 13–32 | 25.76 ± 4.84 | 9–31 | 23.48 ± 5.68 | t = 2.316; DF = 86 P = 0.047 | ||

| Test resultsb | t = 1.641; DF = 44 P = 0.108 | t = 1.645; DF = 42 P = 0.107 | |||||

| Mean difference | 1.40 ± 5.72 | –1.558 ± 6.21 | t = 2.325; DF = 86 P = 0.022 | ||||

| Total | Before | 27–80 | 55.02 ± 9.77 | 28–69 | 58.0 ± 9.22 | t = 1.486; DF = 86 P = 0.146 | –3.67 (–4.36 to –2.99) |

| After | 36–71 | 58.97 ± 8.28 | 25–70 | 52.0 ± 10.91 | t = 3.387; DF = 86 P = 0.001 | ||

| Test resultsb | t = 3.347; DF = 44 P = 0.002 | t = 3.386; DF = 42 P = 0.002 | |||||

| Mean difference | 3.955 ± 7.92 | –6.00 ± 11.61 | t = 4.647; DF = 73.75 P < 0.001 | ||||

aThe results of the independent-sample t test.

bThe results of the paired-sample t test.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that interactive E-learning significantly improved critical care nurses’ delirium recognition ability. The effect size of the study intervention was 3.76, implying the strong effects of the interactive E-learning program on strain of care. 2 In line with this finding, a former study in three hospitals in Australia showed that E-learning significantly improved nurses’ delirium recognition ability. 28 Another study also reported the effectiveness of a delirium training program in improving nurses’ knowledge, self-confidence, and performance. 38 The positive effects of the study intervention can be due to the fact that interactive E-learning is a dynamic and interactive method which encourages learners’ participation in learning.39,40 Audiovisual attractiveness, ease of use, opportunity to ask probable questions, and the use of recently published articles and books for developing E-learning educational materials are among the other reasons for the effectiveness of interactive E-learning in significantly improving nurses’ delirium recognition ability. A former study showed that nurses usually prefer E-learning due to the possibility of accessing educational materials at any time and place and without any specific arrangement. 41 Contrary to our findings, Detroyer and colleagues found interactive E-learning ineffective in improving nurses’ delirium recognition ability and patients’ clinical outcomes. 23 This contradiction may be due to the difference between the studies respecting the time interval between intervention onset and posttest assessment which was two months in the present study and three months in Detroyer and colleagues’ study. Longer time intervals between intervention onset and posttest assessment can result in forgetting the learned materials. Another explanation for this contradiction may be the small number of participants in Detroyer and colleagues’ study (seventeen participants). Moreover, that study did not include a control group and did not use motivational strategies for motivating nurses to use educational materials. We attempted to motivate participants to use E-learning materials through sending them biweekly follow-up messages and awarding them a certificate of participation in the delirium recognition E-learning program.

Our findings also showed that with a large effect size, interactive E-learning significantly reduced the mean scores of nurses’ delirium-related strain of care and all its subscales except for the hyperactive/hyperalert behavior subscale. The positive effects of E-learning on strain of care may be due to its effectiveness in improving nurses’ ability to accurately recognize and manage delirium. A study showed that a six-week educational program on delirium care significantly reduced the stress related to the workload of care delivery to elderly people. 42 In contradiction with our findings, a study showed that interactive E-learning had no significant effects on nurses’ strain of care. 2 This discrepancy may be due to the fact that the sample of that study was heterogeneous and consisted of different healthcare providers (including nurses, physical therapists, and occupational therapists) and the design of that study was single-group. The insignificant effects of the study intervention on the hyperactive/hyperalert behavior subscale of strain of care may be due to the fact that most nurses mostly rely on their personal experiences for delirium management. 43

One of the limitations of the study was the impossibility of random allocation of individual participants due to the likelihood of between-group information leakage. Moreover, the study sample consisted of critical care nurses of only two hospitals and the long-term effects of the study intervention were not measured. We also solely assessed nurses’ delirium recognition-related knowledge. As knowledge improvement is not necessarily associated with performance improvement, future studies are recommended to evaluate the effects of interactive E-learning on nurses’ knowledge and performance respecting delirium recognition and management. In addition, follow-up assessment was performed at only one time point, i.e. two months after the pretest, which provided no reliable data about the long-term effects of the study intervention. Therefore, future studies are recommended to assess the long-term effects of interactive E-learning at different time points. Comparing the effects of interactive E-learning with other teaching methods is also recommended in order to determine the best method for improving critical care nurses’ knowledge and performance in the area of delirium recognition and management.

Conclusion

This study suggests that interactive E-learning can significantly improve critical care nurses’ delirium recognition ability, reduce their strain of care and thereby, improve the quality of nursing care. As nurses’ heavy workload and limited free time are among the main barriers to their participation in face-to-face educational programs, interactive E-learning can be used for in-service education. Educations about E-learning and its use are needed for hospital authorities and nursing managers in order to improve their knowledge of this method and prepare them for using E-learning in in-service education programs. Unlike face-to-face education, interactive E-learning does not put instructors and learners at risk for bacterial and viral diseases which are transmitted through respiratory droplets. Therefore, it can be used as a safe method for improving nurses’ professional knowledge and skills in the current COVID-19 pandemic. 44

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-zip-1-inc-10.1177_1751143720972627 for The effects of interactive E-learning on delirium recognition ability and delirium-related strain of care among critical care nurses by Tahereh Najafi Ghezeljeh, Fatemeh Rahnamaei, Soghra Omrani and Shima Haghani in Journal of the Intensive Care Society

Acknowledgements

This article was extracted from a Master’s thesis in nursing. The authors would like to thank all staff of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, the Research and Technology Administration of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran, and all nurses who participated in the study.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by Iran University of Medical Sciences.

ORCID iDs: Tahereh Najafi Ghezeljeh https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2779-2525

Fatemeh Rahnamaei https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2917-4122

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Van der Kuur A, Bethlehem C, Bruins N, et al. Impact of a premorbid psychiatric disorder on the incidence of delirium during ICU stay, morbidity, and long-term mortality. Crit Care Res Pract 2019; 2019: 6402097–6402098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detroyer E, Dobbels F, Debonnaire D, et al. The effect of an interactive delirium E-learning tool on healthcare workers’ delirium recognition, knowledge and strain in caring for delirious patients: a pilot pre-test/post-test study. BMC Med Educ 2016; 16: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rood P, Huisman-De Waal G, Vermeulen H, et al. Effect of organisational factors on the variation in incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Aust Crit Care 2018; 31: 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan BA, Lasiter S, Boustani MA. Critical care recovery center: making the case for an innovative collaborative care model for ICU survivors. Am J Nurs 2015; 115: 24–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Hammes J, Khan S, et al. Improving recovery and outcomes every day after the ICU (improv): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Trials 2018; 19: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch C, McCluskey L, Wilson D, et al. Delirium is prevalent in older hospital inpatients and associated with adverse outcomes: results of a prospective multi-centre study on world delirium awareness day. BMC Med 2019; 17: 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milisen K, Cremers S, Foreman MD, et al. The strain of care for delirium index: a new instrument to assess nurses' strain in caring for patients with delirium. Int J Nurs Stud 2004; 41: 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faustino TN, Pedreira LC, Freitas YSD, et al. Prevention and monitoring of delirium in older adults: an educational intervention. Rev Bras Enferm 2016; 69: 725–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyiola CE. The experiences of intensive care nurses caring for intubated patients with delirium. Master of Science Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 2019.

- 10.Yue P, Wang L, Liu C, et al. A qualitative study on experience of nurses caring for patients with delirium in ICUs in China: barriers, burdens and decision making dilemmas. Int J Nurs Sci 2015; 2: 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A. The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium‐related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics 2002; 43: 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover S, Shah R. Delirium‐related distress in caregivers: a study from a tertiary care centre in India. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2013; 49: 21–29. DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2012.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farahdel F. Tension due to caring patients with delirium among intensive care unit nurses in North and Razavi Khorasan. Master of Science Thesis, Iran University of Medical Sciences, 2020.

- 14.Mc Donnell S, Timmins F. A quantitative exploration of the subjective burden experienced by nurses when caring for patients with delirium. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 2488–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Awad SA. Critical care nurses' knowledge, perception and barriers regarding delirium in adult critical care units. Am J Nurs Res 2019; 7: 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler BM. Clinical education to decrease perceived barriers to delirium screening in adult intensive care units. Crit Care Nurs Q 2019; 42: 41–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Numan T, Vanden Boogaard M, Kamper AM, et al. Recognition of delirium in postoperative elderly patients: a multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65: 1932–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babine RL, Hyrkas KE, Bachand DA, et al. Falls in a tertiary care hospital – association with delirium: a replication study. Psychosomatics 2016; 57: 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monfared A, Soodmand M, Ghaseemzadeh G. Knowledge and attitude of intensive care units nurses towards delirium working at Guilan University of Medical Sciences in delirium. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2017; 7: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sillner AY, Holle CL, Rudolph JL. The overlap between falls and delirium in hospitalized older adults: a systematic review. Clin Geriatr Med 2019; 35: 221–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieow J, Chen F, Song G, et al. Effectiveness of an advanced practice nurse‐led delirium education and training programme. Int Nurs Rev 2019; 66: 506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van de Steeg L, Ijkema R, Langelaan M, et al. The effect of an E-learning course on nursing staff’s knowledge of delirium: a before-and-after study. BMC Med Educ 2015; 15: 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Detroyer E, Dobbels F, Teodorczuk A, et al. Effect of an interactive E-learning tool for delirium on patient and nursing outcomes in a geriatric hospital setting: findings of a before-after study. BMC Geriatrics 2018; 18: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahhosseini Z, Hamzehgardeshi Z. The facilitators and barriers to nurses' participation in continuing education programs: a mixed method explanatory sequential study. Glob J Health Sci 2015; 7: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosewell J. Learning styles. The Open University, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/pluginfile.php/629607/mod_resource/content/1/t175_4_3.pdf (2005, accessed 27 October 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouleau G, Gagnon M, Côté J, et al. Effects of E-learning in a continuing education context on nursing care: a review of systematic qualitative, quantitative and mixed studies reviews (protocol). BMJ Open 2017; 7: e018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair PM, Kable A, Levett-Jones T, et al. The effectiveness of internet-based E-learning on clinician behaviour and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2016; 57: 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCrow J, Sullivan KA, Beattie ER. Delirium knowledge and recognition: a randomized controlled trial of a web-based educational intervention for acute care nurses. Nurse Educ Today 2014; 34: 912–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Härkänen M, Voutilainen A, Turunen E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of educational interventions designed to improve medication administration skills and safety of registered nurses. Nurse Educ Today 2016; 41: 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicoll P, MacRury S, van Woerden HC, et al. Evaluation of technology-enhanced learning programs for health care professionals: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips JL, Piza M, Ingham J. Continuing professional development programmes for rural nurses involved in palliative care delivery: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today 2012; 32: 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunero S, Jeon Y, Foster K. Mental health education programmes for generalist health professionals: an integrative review. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2012; 21: 428–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hines S, Ramsbotham J, Coyer F. The effectiveness of interventions for improving the research literacy of nurses: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2015; 12: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lahti M, Hätönen H, Välimäki M. Impact of E-learning on nurses’ and student nurses knowledge, skills, and satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2014; 51: 136–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barteit S, Guzek D, Jahn A, et al. Evaluation of E-learning for medical education in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Comput Educ 2020; 145: 103726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Shorbaji N, Atun R, Car J, et al. 2015. ELearning for undergraduate health professional education. A systematic review informing a radical transformation of health workforce development, http://whoeducationguidelines.org/sites/default/files/uploads/eLearning-healthprof-report.pdf (accessed 27 October 2020).

- 37.Fick DM, Hodo DM, Lawrence F, et al. Recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia: assessing nurses’ knowledge using case vignettes. J Gerontol Nurs 2007; 33: 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim M, Lee H. The effects of delirium care training program for nurses in hospital nursing unit. Korean J Adult Nurs 2014; 26: 489–499. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, et al. Instructional design variations in internet-based learning for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med 2010; 85: 909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belanger L, Ducharme F. Narrative-based educational nursing intervention for managing hospitalized older adults at risk for delirium: field testing and qualitative evaluation. Geriatr Nurs 2015; 36: 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asgari P, Cheraghi MA, Shiri M, et al. Comparing two training methods on the level of delirium awareness in intensive care unit nurses. Jundishapur J Health Sci 2016; 8: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh I, Morgan K, Belludi G, et al. Does nurses' education reduce their work-related stress in the care of older people? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr 2015; 6: 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brooke J and, Manneh C. Caring for a patient with delirium in an acute hospital: the lived experience of cardiology, elderly care, renal, and respiratory nurses. Int J Nurs Pract 2018; 24: e12643:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoq MZ. E-Learning during the period of pandemic (COVID-19) in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: an empirical study. Am J Educ Res 2020; 8: 457–464. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-zip-1-inc-10.1177_1751143720972627 for The effects of interactive E-learning on delirium recognition ability and delirium-related strain of care among critical care nurses by Tahereh Najafi Ghezeljeh, Fatemeh Rahnamaei, Soghra Omrani and Shima Haghani in Journal of the Intensive Care Society