Key Points

Question

Does perioperative application of intravaginal estrogen cream in postmenopausal women undergoing a standardized native tissue apical vaginal prolapse repair reduce prolapse recurrence?

Findings

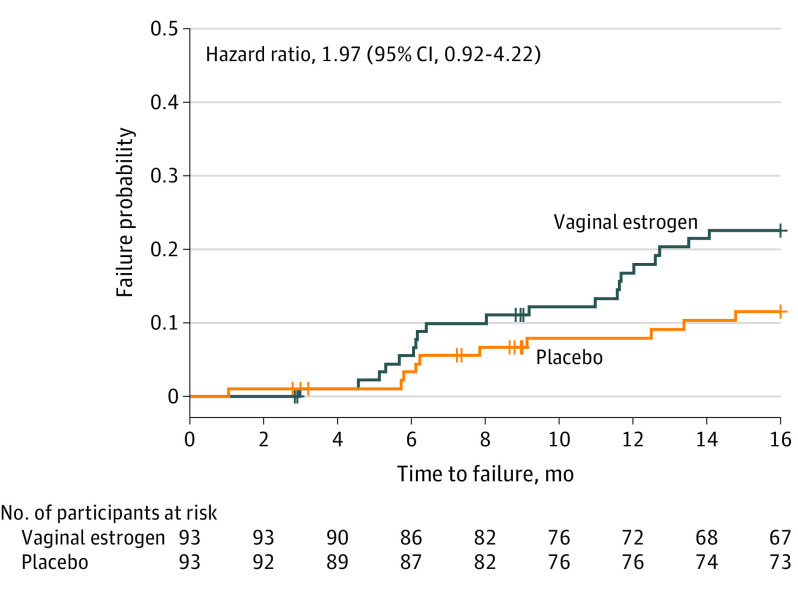

In this randomized clinical trial that included 186 participants with symptomatic anterior/apical vaginal prolapse, there was no statistically significant difference in the composite measure of treatment failure 12 months after the operation in those using vaginal estrogen cream before and after surgery compared with placebo (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.97).

Meaning

Perioperative vaginal estrogen application does not reduce prolapse recurrence rates after native tissue transvaginal repair.

Abstract

Importance

Surgical repairs of apical/uterovaginal prolapse are commonly performed using native tissue pelvic ligaments as the point of attachment for the vaginal cuff after a hysterectomy. Clinicians may recommend vaginal estrogen in an effort to reduce prolapse recurrence, but the effects of intravaginal estrogen on surgical prolapse management are uncertain.

Objective

To compare the efficacy of perioperative vaginal estrogen vs placebo cream on prolapse recurrence following native tissue surgical prolapse repair.

Design, Setting, and Participants

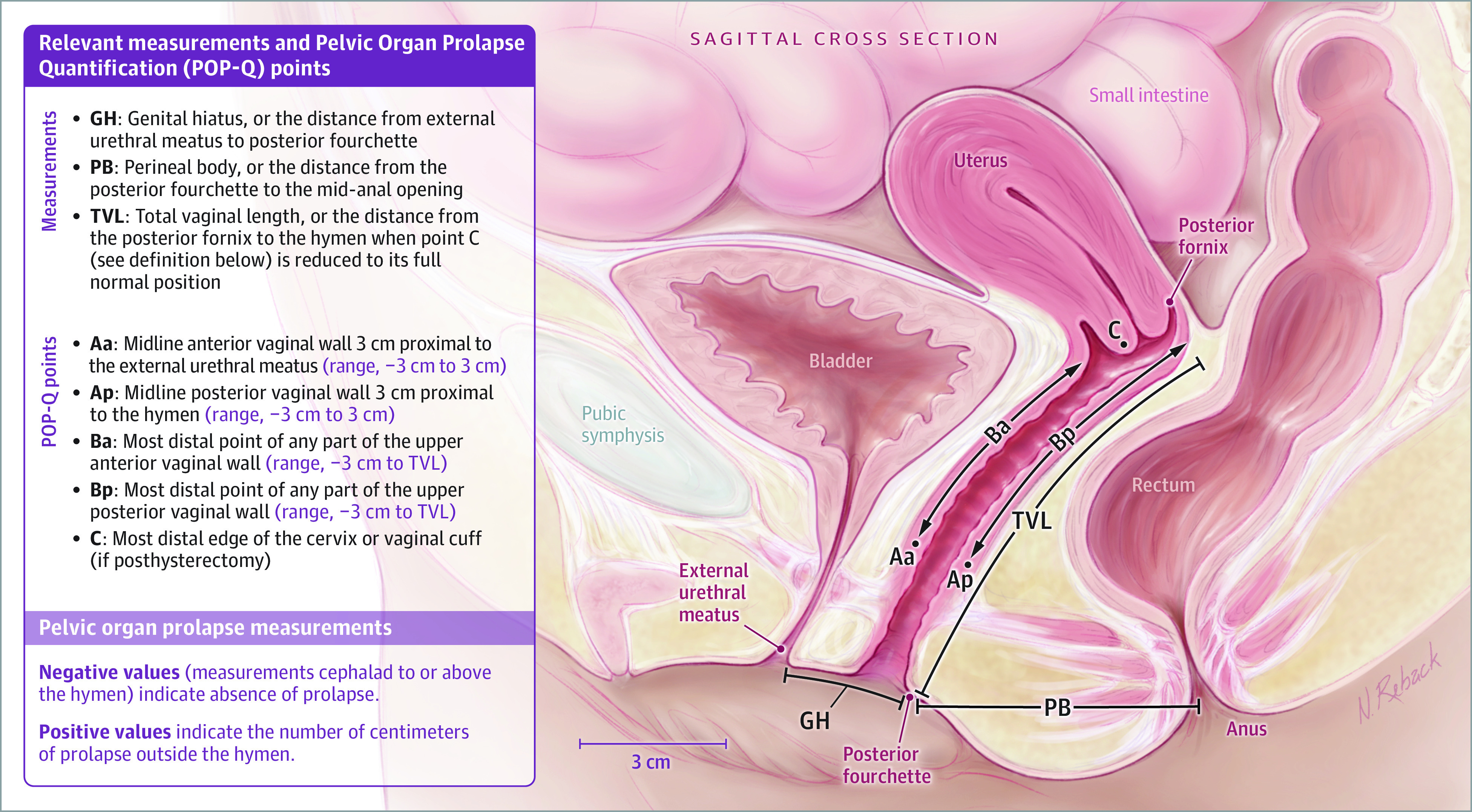

This randomized superiority clinical trial was conducted at 3 tertiary US clinical sites (Texas, Alabama, Rhode Island). Postmenopausal women (N = 206) with bothersome anterior and apical vaginal prolapse interested in surgical repair were enrolled in urogynecology clinics between December 2016 and February 2020.

Interventions

The intervention was 1 g of conjugated estrogen cream (0.625 mg/g) or placebo, inserted vaginally nightly for 2 weeks and then twice weekly to complete at least 5 weeks of application preoperatively; this continued twice weekly for 12 months postoperatively. Participants underwent a vaginal hysterectomy (if uterus present) and standardized apical fixation (either uterosacral or sacrospinous ligament fixation).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was time to failure of prolapse repair by 12 months after surgery defined by at least 1 of the following 3 outcomes: anatomical/objective prolapse of the anterior or posterior walls beyond the hymen or the apex descending more than one-third of the vaginal length, subjective vaginal bulge symptoms, or repeated prolapse treatment. Secondary outcomes included measures of urinary and sexual function, symptoms and signs of urogenital atrophy, and adverse events.

Results

Of 206 postmenopausal women, 199 were randomized and 186 underwent surgery. The mean (SD) age of participants was 65 (6.7) years. The primary outcome was not significantly different for women receiving vaginal estrogen vs placebo through 12 months: 12-month failure incidence of 19% (n = 20) for vaginal estrogen vs 9% (n = 10) for placebo (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.97 [95% CI, 0.92-4.22]), with the anatomic recurrence component being most common, rather than vaginal bulge symptoms or prolapse repeated treatment. Masked surgeon assessment of vaginal tissue quality and estrogenization was significantly better in the vaginal estrogen group at the time of the operation. In the subset of participants with at least moderately bothersome vaginal atrophy symptoms at baseline (n = 109), the vaginal atrophy score for most bothersome symptom was significantly better at 12 months with vaginal estrogen.

Conclusions and Relevance

Adjunctive perioperative vaginal estrogen application did not improve surgical success rates after native tissue transvaginal prolapse repair.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02431897

This randomized clinical superiority trial compares the efficacy of perioperative vaginal estrogen vs placebo cream on native tissue prolapse surgery outcomes.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse affects millions of women. In a hypothetical cohort of women aged 18 years, 1 in 5 can expect to undergo surgery for either stress incontinence or prolapse by the time she turns 80 years, which is greater than her risk of developing breast cancer.1 The lifetime risk for women to undergo pelvic organ prolapse surgery is at least 13%,1 and rates are anticipated to increase as the population ages.2 Reconstructive surgeries for anterior and apical vaginal prolapse are most commonly performed transvaginally using native tissue fixation points (eg, uterosacral or sacrospinous ligaments—2 approaches that have similar efficacy). Prolapse can also be repaired abdominally or laparoscopically using synthetic mesh material; these approaches have tradeoffs of longer operating times, risk of mesh-related complications, increased cost, and a different inventory of possible complications compared with transvaginal repairs.3,4 Unfortunately, reoperation for recurrent prolapse is not rare; approximately 11% to 12% of women 65 years and older will undergo reoperation within 5 years of their index prolapse repair, and rates are highest with native tissue vaginal surgery.3,5 Thus, there is a need to improve outcomes from native tissue prolapse repairs.

It is difficult to separate the effects of general aging from the specific impact of menopause and declining estrogen levels on the health of pelvic floor connective tissues.6,7 Presently, some experts recommend 4 or more weeks of preoperative local estrogen before reconstructive surgery in postmenopausal patients without adequate tissue estrogen,8,9 but this is not evidence based and the effects of intravaginal estrogen in surgical prolapse management—or its prevention—still remain uncertain. Systematic reviews may suggest possible benefits to estrogen application before and after pelvic reconstructive surgery, but, overall, the evidence is extremely limited, and there is a call for studies randomizing participants to receive estrogen preparations for the prevention and management of prolapse before and after reparative surgery.9,10 To address this evidence gap, this trial was designed to compare efficacy of perioperative vaginal estrogen vs placebo cream on native tissue prolapse surgery outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This was a 3-center, randomized, superiority trial. Its design has been published previously11 and the protocol and statistical analysis plan can be found in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2, respectively; these were approved by the institutional review boards at each site and an independent data and safety monitoring board assembled by the National Institute on Aging. All participants provided written informed consent. The statisticians (J.E.P. and L.S.H.) remained masked until February 2022, before which all substantive revisions to the statistical analysis plan and all primary analyses (conducted as “group A” vs “group B”) were made.

Study Population

The eligible study population included postmenopausal women 48 years or older with symptomatic prolapse of the apex and/or anterior vaginal wall at least to the hymen desiring an elective native tissue transvaginal surgical repair. Symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy were not required. Use of any estrogen, progesterone, selective estrogen receptor modulator, or other medication impacting vaginal milieu, by any route, was an exclusion criterion. Those with contraindications to topical estrogen therapy, body mass index (BMI) greater than 35 (ie, greater aromatase expression and estrogen levels associated with increased fat mass), current tobacco use, or previous vaginal apical prolapse repair or use of mesh for prolapse repair were excluded. The rationale for not including patients younger than 48 years (ie, the median age for inception of perimenopause) with early natural or surgical menopause was that these patients, if without contraindication, should be offered systemic estrogen treatment.12 Female sex was both self-reported and investigator-observed. Because differences in symptomatic prolapse prevalence have been identified across different races and ethnicities,13 these demographic data were collected by participant self-report from a list of options, including “more than 1” and “other.”

Randomization

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive vaginal estrogen cream or identical placebo cream. Stratifications were made for site, hysterectomy status, and duration since menopause (<10 y and ≥10 y). Surgeons, outcomes assessors, and participants were masked to intervention assignment.

Interventions

The intervention was 1 g of conjugated estrogen cream, 0.625 mg/g (Premarin), or identical placebo cream inserted vaginally nightly for 2 weeks, then twice weekly for a minimum of 5 total weeks before the surgical procedure. The creams were packaged in identical blank white tubes. Study cream was then resumed at hospital discharge and continued twice weekly for 12 months. The planned apical suspension surgery was standardized across sites as previously described11,14 and was either a uterosacral or sacrospinous ligament suspension, per surgeon discretion, using a combination of permanent and delayed absorbable monofilament sutures; these 2 approaches have been shown to have similar efficacy.15 Vaginal hysterectomy was performed if not previously completed. Concomitant anterior and posterior colporrhaphies and synthetic mesh midurethral slings were allowed and performed at the discretion of the surgeon. No transvaginal prolapse mesh was permitted.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was similar to a previous trial14 with comparison of time to failure by 12 months after surgery, with “failure” defined as 1 or more of the following outcomes: objective prolapse of the anterior or posterior walls beyond the hymen or the apex descending greater than one-third the total vaginal length (this outcome was redefined after a post hoc analysis as any point beyond the hymen [ie, including the apex]), subjective sense of bulge (ie, positive response and any degree of bother to the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 question “Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in your vaginal area?”),16 or repeated treatment (either repeat prolapse surgery or request for pessary). Objective assessments for prolapse recurrence were performed at clinic visits at postoperative months 1, 6, and 12 and a query for subjective sense of bulge was made at postoperative months 3, 6, 9, and 12.

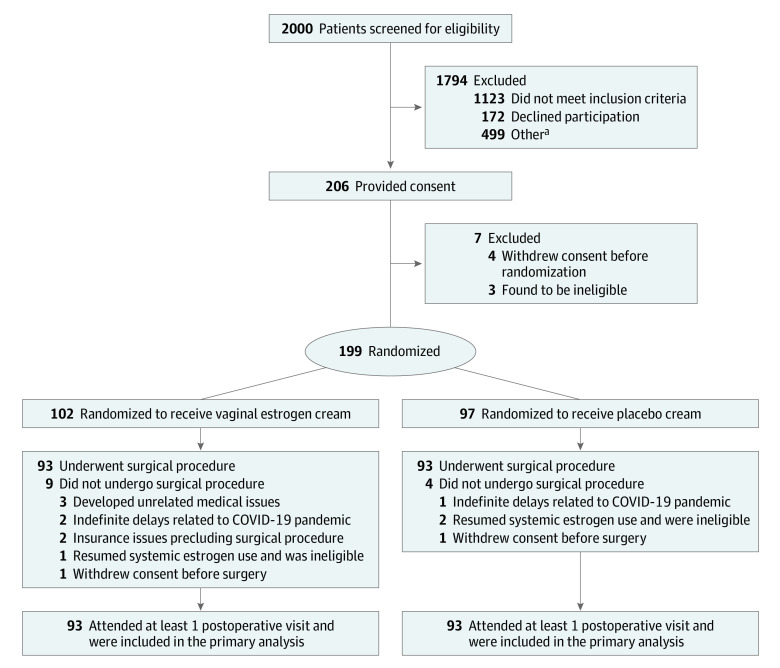

Secondary outcomes included individual measurements of the prolapse examination (ie, the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification [POP-Q], which quantifies descent of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, and the apex [Figure 1]—cervix or posthysterectomy cuff—in relation to the hymen)17; presence and severity/impact of prolapse, urinary, and bowel symptoms reported via the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-716; and the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and Patient Global Impression of Severity.18 Sexual function was assessed with the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ-IR).19 Vaginal atrophy symptoms were assessed with a questionnaire designed for this study that queried symptoms of vaginal dryness, soreness/pain, pain with intercourse (if sexually active), discharge, and itching. These were each scored as either 0 (not experienced), 1 (present but not bothersome), 2 (somewhat bothersome), 3 (moderately bothersome), or 4 (quite a bit bothersome) (Table 1). Changes in scores for the entire population and for the subset with at least 1 moderately bothersome symptom at baseline are reported. The Vaginal Atrophy Assessment tool, also developed for this study, assessed vaginal dryness/moisture, color/pallor, presence/absence of rugae, and presence/absence of petechiae each on a scale ranging from 1 (most atrophic) to 3 (most estrogenized-appearing), for a total possible score range of 4 to 12. Intraoperatively, surgeons were asked for their perception of the tissue quality of the vaginal wall on a scale from 1 (thin, attenuated, poor) to 5 (thick, healthy, robust).

Figure 1. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System Measures.

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal estrogen (n = 102) | Placebo (n = 97) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 64.9 (6.1) | 65.2 (7.3) |

| Race, No. (%)a | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Black | 10 (10) | 5 (5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 |

| White | 92 (90) | 89 (92) |

| Other | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Hispanic or Latina, No. (%)a | 24 (24) | 24 (25) |

| Health insurance, No. (%) | ||

| Private/HMO | 47 (46) | 44 (45) |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 34 (33) | 33 (34) |

| Othera | 20 (20) | 19 (20) |

| Self-pay | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Medical history | ||

| Gravidity, median (IQR) | 3 (2 to 3) | 2 (2 to 3) |

| Vaginal deliveries, median (IQR) | 2 (2 to 3) | 2 (2 to 3) |

| Any cesarean deliveries, No./No. (%) | 13/102 (13) [maximum No. = 4] | 10/97 (10) [maximum No. = 3] |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||

| Never | 71 (70) | 70 (72) |

| Formerly smoked (quit ≥6 mo prior) | 31 (30) | 25 (26) |

| Formerly smoked (quit <6 mo prior) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 20 (20) | 19 (20) |

| ≥3 Urinary tract infections in preceding year, No. (%) | 5 (5) | 5 (5) |

| Surgical history, No. (%) | ||

| Prior hysterectomy | 17 (17) | 15 (16) |

| Prior stress urinary incontinence surgery | 6 (6) | 4 (4) |

| Prior pelvic organ prolapse surgery | 6 (6) | 4 (4) |

| Examination measures | ||

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.3 (3.7) | 27.8 (4.0) |

| POP-Q measurements, median (IQR)b | ||

| Ba | 2 (1 to 3) | 2 (1 to 3) |

| Bp | −1 (−2 to 0) | −1.5 (−2 to 0) |

| C | −0.5 (−3 to 3) | −2 (−3 to 2) |

| Total vaginal length | 9 (8.5 to 10) | 9 (8 to 10) |

| Genital hiatus | 4 (3 to 5) | 4 (3.4 to 5) |

| POP-Q stage, No. (%)c | ||

| 2 | 29 (29) | 28 (29) |

| 3 | 63 (62) | 64 (66) |

| 4 | 9 (9) | 5 (5) |

| Oxford pelvic muscle assessment, median (IQR)d | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) |

| Vaginal epithelial assessment (erosion), No. (%) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Vaginal atrophy assessment total, median (IQR)e | 8 (6 to 8) [n = 100] | 8 (6 to 9) [n = 96] |

| Patient-reported symptom scores | ||

| Pelvic floor distress inventory-20, median (IQR)f | 103.1 (79.2 to 162.5) | 103.1 (60.4 to 144.8) |

| Pelvic organ prolapse distress inventory-6 | 50 (33.3 to 70.8) | 50 (25 to 58.3) |

| Urogenital distress inventory-6 | 37.5 (20.8 to 58.3) | 37.5 (12.5 to 54.2) |

| Colorectal anal distress inventory-8 | 18.8 (6.3 to 43) | 18.8 (6.3 to 37.5) |

| Pelvic floor impact questionnaire-7, median (IQR)g | 52.4 (19 to 104.8) | 42.9 (9.5 to 100) |

| Pelvic organ prolapse impact questionnaire-7 | 19 (0 to 42.9) | 14.3 (0 to 42.9) |

| Urinary impact questionnaire-7 | 19 (9.5 to 47.6) | 14.3 (4.8 to 42.9) |

| Colorectal anal impact questionniare-7 | 4.8 (0 to 23.9) | 4.8 (0 to 19) |

| PISQ-IR score of sexually active women, mean (SD)h | 3.2 (0.7) [n = 39] | 3.3 (0.5) [n = 39] |

| Dyspareunia, No. (%), from PISQ-IRh | 41 (42) [n = 98] | 47 (51) [n = 93] |

| Vaginal atrophy symptoms questionnaire score, median (IQR)i | 0.8 (0.2 to 1.6) | 0.8 (0 to 1.5) |

| Vaginal atrophy symptoms questionnaire maximum score (ie, of most bothersome symptom), median (IQR)i | 2 (1 to 3) | 2 (0 to 3) |

| Vaginal atrophy symptoms questionnaire maximum score (among those with at least 1 bothersome symptom), median (IQR)i | 3 (3 to 4) | 3 (2 to 4) |

| Vaginal atrophy symptoms questionnaire, most bothersome symptom, No. (%)i | ||

| Not applicable, none cause this much bother | 47 (46) | 43 (44) |

| Dryness | 27 (26) | 18 (19) |

| Soreness/pain | 9 (9) | 12 (12) |

| Pain with intercourse | 6 (6) | 11 (11) |

| Discharge | 8 (8) | 5 (5) |

| Itching | 5 (5) | 8 (8) |

| Patient global impression of severity of prolapse, median (IQR)j | 3 (3 to 4) | 3 (3 to 4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); PISQ-IR, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised; POP-Q, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification.

Race and Hispanic or Latina ethnicity were self-assigned by the participant. “Other” race was self-assigned if the participant did not primarily identify as any of the other choices. “Other” health insurance was assigned if the participant reported “other” or “don’t know” or did not reply.

Please see Figure 1 for a detailed description of POP-Q measurement points.

A POP-Q of stage 2 indicates the vagina is prolapsed between 1 cm above and 1 cm below the hymen; stage 3, the vagina is prolapsed more than 1 cm beyond the hymen but is not everted within 2 cm of total vaginal length; stage 4, the vagina is everted to within 2 cm of total vaginal length.

The Oxford Pelvic Muscle Assessment measures levator strength of contraction as 0 (no contraction), 1 (“flicker”), 3 (moderate strength with lift of pelvic floor), or 5 (strong contraction with elevation of the examiner’s fingers against resistance).

Three missing observations. The Vaginal Atrophy Assessment tool assesses dryness/moisture, color/pallor, presence/absence of rugae, and presence/absence of petechiae each on a scale from 1 (most atrophic) to 3 (most estrogenized-appearing), for a total possible score range of 4 to 12.

The Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20 scale ranges from 0 (least distress) to 300 (most distress) and is a sum of 3 subscale scores: the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory-6, the Urogenital Distress Inventory-6, and the Colorectal Anal Distress Inventory-8, each of which has a scale ranging from 0 (least distress) to 100 (most distress).

The Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 scale ranges from 0 (least impact) to 300 (most impact) and is a sum of 3 subscale scores: the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire-7, the Urinary Impact Questionnaire-7, and the Colorectal Anal Impact Questionniare-7, each of which is measured on a scale ranging from 0 (least impact) to 100 (most impact).

The PISQ-IR mean score ranges from 1 (worse sexual experience) to 5 (better sexual experience), with mid-range scores seen commonly with women with pelvic floor disorders. Dyspareunia was defined either as sexually active participants replying “sometimes,” “usually,” or “always” to the question, “Do you have pain during sexual intercourse?” or by sexually inactive participants who replied that they “strongly agree” or “somewhat agree” they were not sexually active due to fear of pain during intercourse.

The Vaginal Atrophy Symptoms Questionnaire asks respondents to rate—over the preceding month—their experiences of vaginal dryness, soreness or pain, pain with intercourse (if sexually active), discharge, and itching, each scored as 0 (not experienced), 1 (present but not bothersome), 2 (somewhat bothersome), 3 (moderately bothersome), or 4 (quite a bit bothersome). The sum is divided by the number of questions (5 [or 4 if not sexually active]). Of those symptoms causing at least moderate bother, the respondent is asked to identify the most bothersome symptom.

The Patient Global Impression of Severity asks respondents to assess their prolapse symptom condition as 1 (normal), 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe).

Sample Size Calculation

A 2-sided log-rank test with an overall sample size of 188 participants undergoing surgery (94 per group) would achieve 80% power at an α level of .05 to detect a hazard ratio of 0.5188 when the proportion of participants meeting failure criteria in the control group was 35% compared with 20% in the intervention group, measured at 12 months; a 15% improvement was considered clinically meaningful. This sample size of 188 accounts for 25% either lost to follow-up or not adherent to study cream intervention in the control and treatment groups. Allowing for an additional 15% attrition/loss of participants from baseline randomization to the surgical procedure, up to 222 total participants were planned for enrollment, halting after 188 participants underwent the surgical procedure. Not all randomized participants near the study’s end could have timely surgery due to COVID-19 pandemic–related delays in elective surgical procedures. Because the loss and nonadherence rates were lower than anticipated, the data and safety monitoring board approved a protocol change to 186 (93 per group) participants undergoing the surgical procedure.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was analyzed according to the assigned treatment group (modified intention-to-treat): all participants who were randomized, underwent a surgical prolapse repair, and had at least 1 postoperative assessment were analyzed according to their randomized group assignment. Two per-protocol analyses were also planned: the first included participants who were at least 50% adherent to cream use preoperatively and for the complete postoperative 12 months, as assessed by medication diaries, and the second included participants who were at least 50% adherent preoperatively and for at least 3 months postoperatively, as assessed by objective before-and-after tube weights.20

Scores from repeated surveys with continuous outcomes were analyzed using a mixed-effects model with repeated measures and subject as a random effect. Tests for interactions were performed between time effect and treatment effect. Cross-sectional assessments of categorical variables (at specific time intervals) were analyzed by χ2 testing. For missing longitudinal data, the likelihood-based mixed-effects models have been reported to be less biased and more representative of the data than other methods even when the data are not missing at random.21 Time-to-event data were analyzed using survival methods to include the log-rank test, Kaplan-Meier plots, and Cox regression, adjusted for treatment group and clinical site. For measures that may not be assumed normal, the data were transformed prior to analysis.

As with the primary outcome, secondary outcome measures such as continuous scores from repeated surveys were analyzed using mixed-effects models. Comparisons of atrophy symptoms used analysis of covariance, with treatment and study center as factors and baseline values as the covariate. Analyses were completed using R, version 4.2.2 (R Foundation).

Results

Study Population, Group Assignments, and Treatment

Enrollment occurred between December 1, 2016, and February 27, 2020. A total of 199 participants were randomized (102 in vaginal estrogen group and 97 in the placebo group; mean [SD] age, 65 [6.7] years); 93 in each group underwent prolapse repair surgery (Figure 2). All participants returned for at least 1 postoperative assessment and were included in the primary analysis. The characteristics of the participants at baseline were similar between the groups (Table 1). Vaginal dryness was the most common symptom (23%) in the 55% of participants with bothersome atrophy-related symptoms at baseline, with a median symptom score of 3 (moderate bother). The proportion of specific surgical approaches used were similar between the groups (Table 2).

Figure 2. Flow of Participants in a Randomized Clinical Trial of Perioperative Vaginal Estrogen as Adjunct to Native Tissue Vaginal Apical Prolapse Repair.

aOther reasons for patient exclusion: planned for nonnative tissue transvaginal surgery, enrolled in an alternative research study, surgery planned in less than 5 weeks, patient inability to speak/read/write in English or Spanish, ulcerated or excoriated tissues, or requiring a coordinated procedure with other surgical teams.

Table 2. Surgical Details and Intraoperative and Postoperative Events.

| Outcome | Vaginal estrogen (n = 93) | Placebo (n = 93) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures performed | |||

| Apical procedure, No. (%) | |||

| Uterosacral ligament suspension | 62 (67) | 75 (81) | |

| Sacrospinous ligament suspension | 29 (31) | 17 (18) | |

| Other | 2 (2)a | 1 (1)a | |

| Hysterectomy, No. (%) | 76 (82) | 79 (85) | −3 (−13.9 to 7.5) |

| Anterior colporrhaphy, No. (%) | 82 (88) | 73 (79) | 9.7 (−0.9 to 20.3) |

| Posterior colporrhaphy, No. (%) | 61 (66) | 59 (63) | 2.2 (−11.6 to 15.9) |

| Midurethral sling, No. (%) | 53 (57) | 53 (57) | 0 (−14.2 to 14.2) |

| Perioperative outcomes | |||

| Operative time, mean (SD), min | 170 (61) | 170 (60) | −0.3 (−17.7 to 17.2) |

| Estimated blood loss, mean (SD), mL | 189 (139) | 175 (110) | 14.1 (−22.2 to 50.4) |

| Transfusion at time of surgery, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Vaginal atrophy assessment total, mean (SD)b | 9.2 (2.1) | 8.3 (2.0) | 0.8 (0.2 to 1.4) |

| Surgeon’s perceived tissue quality at vaginal apex, mean (SD)c | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.06 to 0.56) |

| Intraoperative complications | |||

| Bladder perforation, No. (%) | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | −3.2 (−9.3 to 2.9) |

| Ureteral injury, No. (%) | 5 (5) | 7 (8) | −2.2 (−9.2 to 4.9) |

| Postoperative complications (up to 12 mo) | |||

| UTIs (or pyleonephritis), No. | |||

| Any UTI (counted once only per participant) | 18 (19) | 23 (25) | −5.4 (−17.3 to 6.5) |

| Total number of UTIs | 20 | 33 | |

| Rate of UTIs (number of UTIs per participant) | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.61 (0.32 to 1.13)d |

| Mesh exposure | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 mo or later after operation, No. (%) | n = 90 | n = 87 | |

| Granulation tissue | 16 (18) | 7 (8) | 9.9 (0.2 to 19.6) |

| Suture exposure | 14 (16) | 15 (17) | −1.2 (−12.1 to 9.5) |

| Vaginal skin erosion or ulceration | 0 | 1 (1) | −1.1 (−3.3 to 1.1) |

Abbreviation: UTI, urinary tract infection.

These nonprotocol procedures consisted of 1 uterosacral suspension performed laparoscopically after discovery of a pelvic mass necessitating laparoscopic removal, 1 patient-requested change to a laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy after randomization; and 1 isolated posterior colporrhaphy without vault suspension due to surgeon discretion that there was already adequate vault support, plus safety concerns.

The Vaginal Atrophy Assessment tool assesses dryness/moisture, color/pallor, presence/absence of rugae, and presence/absence of petechiae each on a scale ranging from 1 (most atrophic) to 3 (most estrogenized-appearing), for a total possible score range of 4 to 12. This was assessed either at the preoperative visit or in the operating room, which was at least 5 weeks after randomization.

Surgeons judged the tissue quality of the apical vagina for vault suspension suture placement on a scale ranging from 1 (thin/attenuated/poor) to 5 (thick/healthy/robust).

Incident rate ratio (95% CI).

Primary Outcome

There was no statistically significant difference in failure risk demonstrated for the composite primary outcome between the groups. The adjusted hazard ratio of failure for vaginal estrogen compared with placebo was 1.97 (95% CI, 0.92-4.22; P = .08) (Figure 3). The proportional hazards assumption was met. At 12 months, the model-estimated failure was 19% (95% CI, 9%-27%) (n = 20) for the vaginal estrogen group and 9% (95% CI, 2%-15%) (n = 10) for the placebo group.

Figure 3. Failure Probability for the Composite Primary Outcome Comparing Adjunctive Use of Vaginal Estrogen With Placebo Cream After Standardized Vaginal Vault Suspension Surgery.

Failure probability from survival analysis was estimated using an interval-censored proportional hazard model, controlled for clinical site and treatment assignment. Hazard ratio estimates the relative risk of failure using conjugated vaginal estrogen as compared to placebo cream. Available follow-up data were included for all participants through 12 months. At the time of analysis, 140 participants were censored prior to 12 months (67 with vaginal estrogen and 73 with placebo). The table indicates the number of patients who have not been censored or experienced a failure and who are still at risk for failure at the specified time point. The latest 12-month visit was recorded at 16.9 months after surgery; patients who had not experienced a failure prior to that time were censored for this analysis.

Adherence to the study cream using the first per-protocol definition (ie, use of at least 50% of anticipated study cream preoperatively and for 12 months postoperatively, per participant diary) was 77% for estrogen users and 74% of placebo participants. Using the second per-protocol definition (ie, use of at least 50% of anticipated study cream preoperatively and for 3 or more months postoperatively, per objective before-and-after tube weights), 82% of estrogen users and 75% of placebo users were adherent. Using the first per-protocol definition for adherence, the adjusted hazard ratio of failure for vaginal estrogen compared with placebo remained at 1.97 (95% CI, 0.80-4.84; P = .14) (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). For the second per-protocol definition for adherence, the adjusted hazard ratio of failure for vaginal estrogen compared with placebo was 2.44 (95% CI, 1.01-5.88; P = .048) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3).

Cumulative failures and failure categories by postoperative month 12 are detailed in eTable 1 in Supplement 3. At 12 months, the failure rate for the vaginal estrogen group was 20 of 87 participants (23%) compared with 10 of 83 (12%) for the placebo group, a risk difference of 11% (95% CI, −0.3% to 22.2%). Per-protocol cumulative failures and failure categories are presented in eTable 2 in Supplement 3. The most commonly reached failure component was anatomic, many of which were related to partial descent of the vaginal apex without visible prolapse beyond the hymen or symptomatic prolapse.

Secondary Outcomes

Table 3 shows secondary outcomes at 12 months. There were no differences in median POP-Q measurements. On the day of the surgical procedure, the surgeon assessment of vaginal tissue differed by group, with less atrophic appearance in the vaginal estrogen group than the placebo group: mean (SD) of 9.2 (2.2) vs 8.3 (2.0) points (difference, 0.8 [95% CI, 0.2-1.4]; P = .01). Similarly, surgeon assessment of vaginal apex tissue quality was greater in the vaginal estrogen group than the placebo group: mean (SD) of 3.6 (0.8) vs 3.3 (0.9) (difference, 0.3 [95% CI, 0.06-0.56]; P = .02).

Table 3. Secondary Outcomes.

| Outcomes at postoperative 12 mo | Vaginal estrogen (n = 93) | Placebo (n = 93) | Between-group difference (95% CI) or P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 mo | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | Baseline | 12 mo | Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| Physical examination at 12 mo | |||||||

| Pelvic organ prolapse quantification measurements, median (IQR)a | n = 90 | n = 87 | |||||

| Ba | −2 (−2 to −1) | −2 (−2 to −1) | 0 (0 to 1) | ||||

| Bp | −2 (−3 to −2) | −2 (−3 to −2) | 0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | ||||

| C | −7 (−8 to −6) | −7 (−8 to −6) | 0 (−0.5 to 0.5) | ||||

| Total vaginal length | 9 (7.5 to 9) | 8 (7.25 to 9) | −1 (−1 to 0) | ||||

| Genital hiatus | 3 (2.5 to 4) | 3 (2.5 to 3.5) | 0 (0 to 0) | ||||

| Patient-reported symptoms at 12 mo | |||||||

| PGII, much better or very much better, No./No. (%)b | 88/89 (98) | 84/86 (97) | .62 | ||||

| Patient global impression of severity of prolapse, median (IQR)c | 1 (1 to 1) | 1 (1 to 1) | .32 | ||||

| Most bothersome vaginal atrophy symptoms, No./No. (%)d | .14 | ||||||

| None | 72/89 (81) | 62/86 (72) | |||||

| Dryness | 8/89 (9) | 8/86 (9) | |||||

| Soreness/pain | 0/89 | 1/86 (1) | |||||

| Pain with intercourse | 2/89 (2) | 9/86 (11) | |||||

| Discharge | 0/89 | 1/86 (1) | |||||

| Itching | 7/89 (8) | 5/86 (6) | |||||

| Resolved or improving stress urinary incontinence, No./No. (%)e | 42/47 (89) | 31/34 (91) | −1.8% (−14.8% to 11.2%) | ||||

| Resolved or improving urgency urinary incontinence, No./No. (%)e | 40/45 (89) | 42/47 (89) | −0.5% (−13.2% to 12.3%) | ||||

| Resolved or improving (well-formed) fecal incontinence, No./No. (%)e | 17/21 (81) | 10/13 (77) | 4% (−24.3% to 32.4%) | ||||

| Resolved or improving (loose) fecal incontinence, No./No. (%)e | 21/28 (75) | 18/24 (75) | 0% (−23.6% to 23.6%) | ||||

| Total dyspareunia at 12 mo per PISQ-IR,f No./No. (%) | 22/90 (24) | 29/88 (33) | −8.5% (−21.7% to 4.7%) | ||||

| Sexually active with de novo dyspareunia (PISQ-IR), No./No. (%) | 1/19 (5) | 3/16 (19) | −13.5% (−35.1% to 8.1%) | ||||

| Not sexually active with de novo dyspareunia (PISQ-IR), No./No. (%) | 2/50 (4) | 1/44 (2) | 1.7% (−5.3% to 8.7%) | ||||

| Changes in patient-reported symptoms from baseline to 12 mo, adjusted mean (95% CI) | |||||||

| Pelvic floor distress inventory-20g | 115.0 (106.1 to 124.0) | 23.1 (14.1 to 32.2) | −91.9 (−105.4 to −78.4) | 107.9 (99.0 to 116.8) | 23.1 (13.9 to 32.3) | −84.8 (−98.4 to −71.2) | −7.1 (−28.8 to 14.6) |

| Pelvic organ prolapse distress inventory-6 | 49.8 (46.7 to 53.0) | 4.6 (1.4 to 7.9) | −45.2 (−50.5 to −39.9) | 46.4 (43.2 to 49.6) | 5.5 (2.2 to 8.8) | −41.0 (−45.8 to −35.1) | −4.3 (−12.8 to 4.3) |

| Urogenital distress inventory-6 | 39.9 (35.8 to 44.0) | 9.8 (5.7 to 14.0) | −30.1 (−36.2 to 23.8) | 37.9 (33.8 to 42.0) | 9.2 (5.0 to 13.5) | −28.7 (−34.9 to −22.4) | −1.4 (−11.3 to 8.6) |

| Colorectal anal distress inventory-8 | 25.1 (21.5 to 28.7) | 8.8 (5.1 to 12.4) | −16.3 (−20.8 to −11.8) | 23.6 (20.0 to 27.2) | 8.5 (4.8 to 12.2) | −15.1 (−19.7 to −10.6) | −1.2 (−8.5 to 6.0) |

| Pelvic floor impact questionnaire-7h | 71.9 (63.2 to 80.6) | 8.9 (0.1 to 17.8) | −62.9 (−77.0 to −48.9) | 64.2 (55.5 to 72.9) | 9.5 (0.5 to 18.5) | −54.7 (−68.8 to −40.5) | −8.3 (−30.8 to 14.2) |

| Pelvic organ prolapse impact questionnaire-7 | 26.9 (23.3 to 30.5) | 1.2 (0 to 4.9) | −25.7 (−31.8 to −19.6) | 25.2 (21.6 to 28.8) | 2.6 (0 to 6.3) | −22.6 (−28.7 to −16.5) | −3.1 (−12.8 to 6.6) |

| Urinary impact questionnaire-7 | 28.9 (25.4 to 32.5) | 4.3 (0.7 to 8.0) | −24.6 (−30.3 to −18.9) | 26.0 (22.4 to 29.6) | 4.2 (0.5 to 7.9) | −21.8 (−27.5 to −16.1) | −2.8 (−11.9 to 6.3) |

| Colorectal anal impact questionniare-7 | 16.2 (13.3 to 19.2) | 3.5 (0.5 to 6.5) | −12.7 (−17.1 to −8.3) | 12.9 (10.0 to 15.9) | 2.8 (0 to 5.9) | −10.2 (−14.6 to −5.7) | −2.6 (−9.6 to 4.5) |

| PISQ-IR score change from baseline of sexually active participantsi | 3.19 (3.01 to 3.38) | 3.55 (3.35 to 3.75) | 0.36 (0.16 to 0.56) | 3.28 (3.09 to 3.47) | 3.70 (3.50 to 3.90) | 0.42 (0.23 to 0.61) | −0.06 (−0.37 to 0.24) |

| Vaginal atrophy symptoms, mean scored | 1.02 (0.86 to 1.17) | 0.39 (0.23 to 0.55) | −0.62 (−0.84 to −0.41) | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.14) | 0.42 (0.25 to 0.58) | −0.56 (−0.77 to −0.35) | −0.06 (−0.40 to 0.28) |

| Vaginal atrophy symptoms maximum score (among those with at least 1 bothersome symptom)d | 3.20 (2.84 to 3.56) | 1.06 (0.70 to 1.43) | −2.14 (−2.64 to −1.64) | 2.89 (2.53 to 3.25) | 1.62 (1.24 to 1.99) | −1.27 (−1.78 to −0.77) | −0.87 (−1.67 to −0.07) |

| SF-12 physical score, median (IQR) | 47.0 (45.2 to 48.7) | 52.1 (50.3 to 53.8) | 5.1 (2.8 to 7.4) | 45.2 (43.5 to 47.0) | 53.2 (51.4 to 55.0) | 8.0 (5.7 to 10.3) | −2.9 (−6.6 to 0.8) |

| SF-12, mental score, median (IQR) | 47.7 (46.2 to 49.2) | 49.6 (48.1 to 51.2) | 1.9 (−0.3 to 4.1) | 46.8 (45.3 to 48.4) | 50.0 (48.4 to 51.6) | 3.2 (1.0 to 5.4) | −1.3 (−4.8 to 2.3) |

Abbreviations: PGII, patient global impression of improvement; PGPISQ-IR, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised; SF-12, 12-item Short Form Health Survey.

For definitions of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification measurements, see Figure 1.

Patient Global Impression of Improvement is scored from 1 (very much better) to 7 (very much worse).

Patient Global Impression of Severity refers to the patient’s perception of her prolapse symptom condition, rated from 1 (normal) to 4 (severe).

For a description of the Vaginal Atrophy Symptom Questionnaire, see footnote i in Table 1.

Resolved or improving stress and urgency urinary incontinence and fecal incontinence follows up those participants responding affirmatively at baseline to the symptom presence and assesses change to either no longer bothersome or bothersome but to a lesser degree.

Sexually active with de novo dyspareunia (ie, replying “sometimes,” “usually,” or “always” to PISQ-IR question of “Do you have pain during sexual intercourse?”) defines women who were sexually active at baseline and at 12 months and who are experiencing pain during intercourse only at 12 months. Not sexually active with de novo dyspareunia (“strongly agree” or “somewhat agree”) defines women who were not sexually active at baseline due to reasons other than fear of pain during intercourse and became sexually inactive at 12 months due to fear of pain during intercourse.

For a description of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-20, see footnote f in Table 1.

For a description of the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7, see footnote g in Table 1.

For a description of the PISQ-IR, see footnote h in Table 1.

Overall, 98% of participants in the vaginal estrogen group and 97% in the placebo group reported being “much better” or “very much better” per the Patient Global Impression of Improvement scale (difference, 1.2 [95% CI, −2.7 to 5.1]; P = .62). Improvements from baseline were seen in all patient-reported outcome measures, but without significant differences between vaginal estrogen and placebo, except for vaginal atrophy symptoms.

The percentage of participants with no vaginal atrophy symptoms similarly improved from baseline in both groups, from 46% to 81% for vaginal estrogen and 44% to 72% for placebo. However, among those with bothersome atrophy symptoms at baseline, there was significantly greater improvement by 12 months in the vaginal estrogen group: adjusted mean (SE) of 3.20 (0.18) to 1.06 ( 0.19) points, corresponding with a change from moderate bother to no bother. The adjusted mean (SE) in the placebo group changed from 2.89 (0.18) to 1.62 (0.19) points, corresponding with a change from moderate bother to somewhat bothered (adjusted mean difference, −0.87 points [95% CI, −1.67 to −0.07]; P = .003).

Among sexually active participants, overall sexual function improved similarly in both groups as measured by the PISQ-IR total score, increasing by an adjusted mean of 0.36 points (95% CI, 0.16-0.56) in the vaginal estrogen group and 0.42 points (95% CI, 0.23-0.61) in the placebo group (adjusted mean difference, −0.06 [95% CI, −0.37 to 0.24]; P = .10). Among sexually active participants, the dyspareunia rates changed from 41 of 98 (42%) to 22 of 90 (24%) in the vaginal estrogen group and 47 of 93 (51%) to 29 of 88 (33%) in the placebo group. De novo dyspareunia, measured by the PISQ-IR, was identified in 3 participants in the vaginal estrogen group and 4 participants in the placebo group. On the Vaginal Atrophy Symptom questionnaire at 12 months, 2 of 89 participants (2%) in the vaginal estrogen group reported that their most bothersome symptom was “pain with intercourse” compared with 9 of 86 (11%) in the placebo group (χ2 = 5.01; P = .03).

Adverse Events

The most reported adverse event was urinary tract infection, reported by 18 participants (19%) in the vaginal estrogen group vs 23 (25%) in the placebo group (P = .38) (Table 2; eTable 3 in Supplement 3). The number of urinary tract infections per participant was less for the vaginal estrogen group than for the placebo group (0.22 vs 0.36; P = .12). The next most common adverse events were yeast infection, nausea/vomiting, and dyspareunia (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). After postoperative month 6, suture exposure occurred in 14 of 90 participants (16%) in the vaginal estrogen group and 15 of 97 (17%) in the placebo group and granulation tissue was identified in 16 of 90 participants (18%) in the vaginal estrogen group and 7 of 87 (8%) in the placebo group (P = .048). No repeated operations were performed for suture exposure or granulation tissue. There were no cases of midurethral sling mesh exposure/erosion in either group.

Discussion

Perioperative vaginal estrogen cream did not improve surgical outcomes at 12 months after native tissue apical prolapse repair compared with placebo vaginal cream. Although 1 per-protocol analysis that included only participants objectively adherent to at least 50% of anticipated intervention use preoperatively and at least 3 months postoperatively found a higher rate of failure in the estrogen group, most of these failures were related to partial anatomic descent of the vaginal apex without prolapse beyond the hymen and no symptoms of bulge. In a post hoc analysis, when the primary outcome (modified intention-to-treat) was reanalyzed using a stricter anatomic failure definition of prolapse of the anterior, posterior, or apical vagina descending beyond the hymen, there was no difference in recurrent prolapse rates (eTable 4 in Supplement 3). In participants randomized to receive vaginal estrogen, at the time of surgery, masked examiners identified a more estrogenized-appearing vaginal epithelium and surgeon perception was that of a more robust, healthier-appearing vaginal wall into which apical fixation sutures were placed. Postoperatively, among participants with bothersome atrophy symptoms at baseline, there was greater improvement in these symptoms among those randomized to receive estrogen, corresponding with a change from moderate bother to no bother.

The overall failure rate of 18% by 12 months postoperatively in this trial was lower than expected; by comparison, the 2-year failure rate in the OPTIMAL study that used the same operative technique and same composite definition of failure was 36%.15 Besides the measurement of failure at an earlier time point in the present study, differences in the baseline characteristics of these studies’ populations may partially explain their differences in success/failure. First, because this study excluded participants with BMI greater than 35, overall, its participants had lower mean BMIs than in the OPTIMAL trial (27 vs 29). Some studies suggest that overweight/obesity is a risk for greater postoperative recurrence of prolapse.22,23 Second, this study had a much smaller percentage of participants with a prior hysterectomy compared with the OPTIMAL study (16% vs 27%), meaning that a greater proportion of participants first underwent a vaginal hysterectomy before their native tissue vault suspension in the current study. Conceivably, there could be differences in the quality of an apical prolapse repair when performed concomitantly with hysterectomy and a “fresh” vaginal cuff compared with the scar tissue encountered at time of a posthysterectomy vaginal vault suspension. This deserves additional study. Finally, although most POP-Q scores of participants appeared similar at baseline in both studies, the median genital hiatus measure was modestly smaller/narrower in this study compared with that reported in the OPTIMAL study: 4 (IQR, 3-5) vs 4.5 (range, 2-10). A wider hiatus may indicate weaker levator muscle tone and strength and has been shown to be an important risk factor associated with recurrent prolapse.24,25

Although expert opinion aligns with many urogynecologists’ anecdotal recommendations for pre- and/or postoperative vaginal estrogen to be used empirically for menopausal women undergoing reconstructive surgery,8,9 there are few prior studies that directly examine local estrogen use and postoperative outcomes.26,27,28,29 These trials either had nonprolapse primary outcomes (eg, assessments of vaginal tissue quality) or were small or pilot studies. The study by Felding et al,26 similar to the current study, did not identify a benefit with respect to prolapse recurrence but did find an improvement in urinary tract infection frequency among women randomized to receive vaginal estrogen.

Strengths of this study include its triple-masked randomized design. There were multiple surgeons from 3 geographically distinct academic programs, lending to more generalizable findings. The surgical approach was standardized. Participant retention was high, as were study drug adherence rates. The use of postoperative study drug for 12 months extends beyond the timing necessary for surgical wound healing.30,31 Where possible, validated questionnaires and outcome measures were used, and adverse events were queried in a standardized fashion.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, nonvalidated instruments were used to assess the secondary outcomes of atrophy objectively and as a patient-reported outcome. Second, the timing of the primary outcome at 12 months after surgery may be deemed too early, but, pragmatically, this was the longest one could ask or expect a postoperative patient to use placebo vaginal cream. After 12 months, patients were free to use—or not use—prescribed vaginal estrogen based on atrophy-related symptoms; this was recorded, and all participants continue to be followed up for up to 36 months. Third, the inclusion of the surgical failure criterion of the apex descending below one-third total vaginal length may seem too conservative, although this was the standard when this study was designed.14 There is no universally agreed-on definition of prolapse recurrence, but outcomes are also reported using a more contemporary definition of any POP-Q measure beyond the hymen (eTable 4 in Supplement 3).32,33 Fourth, participants were not queried about group assignment, so there are no data about who may have become unmasked because of feeling atrophy symptoms. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of nonadherence between the groups. Fifth, the wide CI for the primary outcome (0.92-4.22) points to relative uncertainty of the point estimate for the adjusted hazard ratio associated with vaginal estrogen use.

Conclusions

Perioperative vaginal estrogen does not reduce prolapse recurrence following native tissue vaginal repair, as performed in this study. Vaginal estrogen appears beneficial for reducing atrophy-related symptoms in the postoperative period.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eTables

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201-1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1096-1100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(10):CD012376. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2016-2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu JM, Dieter AA, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Cumulative incidence of a subsequent surgery after stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse procedure. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(6):1124-1130. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moalli PA, Talarico LC, Sung VW, et al. Impact of menopause on collagen subtypes in the arcus tendineous fasciae pelvis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(3):620-627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moalli PA, Klingensmith WL, Meyn LA, Zyczynski HM. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression by estrogen in fibroblasts that are derived from the pelvic floor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(1):72-79. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.124845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karram MM, Gebhart JB. Managing mesh complications after surgeries for urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. In: Barber MD, Bradley CS, Karram MM, Walters MD, eds. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2022:402. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahn DD, Ward RM, Sanses TV, et al. ; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group . Vaginal estrogen use in postmenopausal women with pelvic floor disorders: systematic review and practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(1):3-13. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2554-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail SI, Bain C, Hagen S. Oestrogens for treatment or prevention of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(9):CD007063. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007063.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahn DD, Richter HE, Sung VW, Larsen WI, Hynan LS. Design of a randomized clinical trial of perioperative vaginal estrogen versus placebo with transvaginal native tissue apical prolapse repair (Investigation to Minimize Prolapse Recurrence of the Vagina using Estrogen: IMPROVE). Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(1):e227-e233. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaunitz AM, Kapoor E, Faubion S. Treatment of women after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed prior to natural menopause. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1429-1430. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitcomb EL, Rortveit G, Brown JS, et al. Racial differences in pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1271-1277. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bf9cc8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Menefee S, et al. ; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . Operations and pelvic muscle training in the management of apical support loss (OPTIMAL) trial: design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(2):178-189. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023-1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):103-113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10-17. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):98-101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers RG, Rockwood TH, Constantine ML, et al. A new measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(7):1091-1103. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bachmann G, Bouchard C, Hoppe D, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose regimens of conjugated estrogens cream administered vaginally. Menopause. 2009;16(4):719-727. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a48c4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallinckrodt CH, Kaiser CJ, Watkin JG, Molenberghs G, Carroll RJ. The effect of correlation structure on treatment contrasts estimated from incomplete clinical trial data with likelihood-based repeated measures compared with last observation carried forward ANOVA. Clin Trials. 2004;1(6):477-489. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn049oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawasaki A, Corey EG, Laskey RA, Weidner AC, Siddiqui NY, Wu JM. Obesity as a risk for the recurrence of anterior vaginal wall prolapse after anterior colporrhaphy. J Reprod Med. 2013;58(5-6):195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, Kluivers KB, Van Eijndhoven HW. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(2):252.e1-252.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medina CA, Candiotti K, Takacs P. Wide genital hiatus is a risk factor for recurrence following anterior vaginal repair. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;101(2):184-187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowder JL, Oliphant SS, Shepherd JP, Ghetti C, Sutkin G. Genital hiatus size is associated with and predictive of apical vaginal support loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):718.e1-718.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felding C, Mikkelsen AL, Clausen HV, Loft A, Larsen LG. Preoperative treatment with oestradiol in women scheduled for vaginal operation for genital prolapse: a randomised, double-blind trial. Maturitas. 1992;15(3):241-249. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(92)90208-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karp DR, Jean-Michel M, Johnston Y, Suciu G, Aguilar VC, Davila GW. A randomized clinical trial of the impact of local estrogen on postoperative tissue quality after vaginal reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18(4):211-215. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e31825e6401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verghese TS, Middleton L, Cheed V, Leighton L, Daniels J, Latthe PM; LOTUS trial collaborative group . Randomised controlled trial to investigate the effectiveness of local oestrogen treatment in postmenopausal women undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery (LOTUS): a pilot study to assess feasibility of a large multicentre trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e025141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahn DD, Good MM, Roshanravan SM, et al. Effects of preoperative local estrogen in postmenopausal women with prolapse: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3728-3736. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenhalgh DG. The role of apoptosis in wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30(9):1019-1030. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(98)00058-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinke JM, Sorg H. Wound repair and regeneration. Eur Surg Res. 2012;49(1):35-43. doi: 10.1159/000339613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al. ; NICHD Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . Effect of vaginal mesh hysteropexy vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1054-1065. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menefee S, Richter HE, Myers D, et al. ; NICHD Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . Design of a 3-arm randomized trial for posthysterectomy vault prolpase involving sacral colpopexy, transvaginal mesh, and native tissue apical repair: the apcial suspension repair for vault prolapse in a three-arm randomized trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26(7):415-424. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eTables

Data sharing statement