Key Points

Question

What are the barriers and facilitators experienced by Latinx individuals with kidney failure who initiate home dialysis treatment?

Findings

In this qualitative study of Latinx people receiving home dialysis, barriers to home dialysis included misinformation, limited education, and issues with maintenance. Facilitators to home dialysis included an improved lifestyle and strong support system.

Meaning

Addressing reported barriers and facilitators to home dialysis may help improve access to home dialysis for Latinx individuals with kidney disease.

This qualitative study evaluates the experiences of Latinx individuals with kidney failure who are receiving home dialysis.

Abstract

Importance

Latinx people have a high burden of kidney disease but are less likely to receive home dialysis compared to non-Latinx White people. The disparity in home dialysis therapy has not been completely explained by demographic, medical, or social factors.

Objective

To understand the barriers and facilitators to home dialysis therapy experienced by Latinx individuals with kidney failure receiving home dialysis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This qualitative study used semistructured interviews with Latinx adults with kidney failure receiving home dialysis therapy in Denver, Colorado, and Houston, Texas, between November 2021 and March 2023. Patients were recruited from home dialysis clinics affiliated with academic medical centers. Of 39 individuals approached, 27 were included in the study. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using thematic analysis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Themes and subthemes regarding barriers and facilitators to home dialysis therapy.

Results

A total of 27 Latinx adults (17 [63%] female and 10 [37%] male) with kidney failure who were receiving home dialysis participated. Themes and subthemes were identified, 3 related to challenges with home dialysis and 2 related to facilitators. Challenges to home dialysis included misinformation and immigration-related barriers to care (including cultural stigma of dialysis, misinformation regarding chronic disease care, and lack of health insurance due to immigration status), limited dialysis education (including lack of predialysis care, no-nephrologist education, and shared decision-making), and maintenance of home dialysis (including equipment issues, lifestyle restrictions, and anxiety about complications). Facilitators to home dialysis included improved lifestyle (including convenience, autonomy, physical symptoms, and dietary flexibility) and support (including family involvement, relationships with staff, self-efficacy, and language concordance).

Conclusions and Relevance

Latinx participants in this study who were receiving home dialysis received misinformation and limited education regarding home dialysis, yet were engaged in self-advocacy and reported strong family and clinic support. These findings may inform new strategies aimed at improving access to home dialysis education and uptake for Latinx individuals with kidney disease.

Introduction

A priority of the Advancing American Kidney Health Initiative, a 2019 presidential executive order, is to increase the rate of home dialysis use (peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis) over in-center dialysis for people with incident kidney failure in the United States. While Latinx individuals experience 2.1 times the incidence of kidney failure compared to non-Latinx White individuals,1 they are less likely to be treated with home dialysis.1,2,3 In the United States in 2020, 11.8% of Latinx individuals starting dialysis received dialysis at home compared with 14.7% of non-Latinx White individuals. After 1 year of dialysis, 16.5% of Latinx people receiving dialysis used home dialysis therapies, compared to 22.9% of non-Latinx White people receiving dialysis who used home therapies.1

Known facilitators to home dialysis uptake in non-Latinx populations include higher levels of education and socioeconomic status, predialysis care (allowing for adequate education and preparatory time for dialysis), and family and care support.4,5,6 Patient-level barriers described in non-Latinx populations include lack of social support, worry about performing independently, and inadequate space or housing.5,7 Worldwide, home dialysis use varies widely among Latin American countries8; Mexico has one of the highest rates of peritoneal dialysis use in the world. Despite this, the rate of home dialysis use among Latinx populations in the US is low, which may be due to difference in patient- and system-level factors in the US.8,9,10 However, home dialysis uptake by Latinx populations in the US is not completely understood even when adjusting for medical, demographic, and social factors.2,3 Thus, it is unclear why home dialysis use is lower in this group, as Latinx patient perspectives regarding barriers and facilitators to home dialysis in the US have not been adequately studied. Our objective was to understand the barriers and facilitators to home dialysis therapy decision-making, uptake, and maintenance through qualitative interviews with Latinx individuals with kidney failure receiving home dialysis.

Methods

Study Design

Semistructured one-on-one phone interviews were conducted between November 2021 and March 2023 in the participants’ preferred language (English or Spanish). Participants provided verbal consent to participate in the research study and received a $60 gift card as compensation. The study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research reporting guideline.11 The Colorado and Harris Health Multi-Institutional Review Board approved the study as exempt from ongoing review (category 2 exemption12).

Setting and Participants

Eligible participants were English- or Spanish-speaking adults 18 years and older who were receiving home dialysis and who self-identified as Latinx/o/a and/or Hispanic. Participants were recruited from 3 home dialysis clinics affiliated with academic medical centers (2 in Denver, Colorado, and 1 in Houston, Texas). Initially, participants were recruited via convenience sampling of patients treated with home dialysis at 1 academic medical center in Denver. After initial analysis was completed, the Texas sample and second clinic in Denver were added in March 2022 using theoretical sampling (an iterative recruiting process where participants are recruited while data are being analyzed and theories are emerging).13 The invitation to participate occurred at their dialysis clinic appointment or by phone, and the semistructured interview and demographic questionnaire occurred via phone.

Interview Guide

The interview guide was informed by an extensive literature review,2,5,7,14,15,16,17,18,19 which was used as sensitizing concepts20,21 to guide the direction of the initial interviews. Questions explored dialysis treatment decision-making, education, and health care navigation as well as transition to home dialysis (eAppendix in Supplement 1).

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted by members of the study team (K.R., who is a nephrologist with prior qualitative research experience, and R.G.J., who is a Latina bilingual medical student trained in qualitative interviewing and methods by K.R., neither of whom had previous clinical interactions with participants, and C.C., who is a Latina bilingual patient navigator who had previous clinical interactions with some of the participants). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, professionally translated to English, deidentified, and continued until thematic saturation (ie, when further observation and analysis do not reveal new concepts).13,21,22

Analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed contemporaneously by 3 members (K.R., R.G.J., C.C.) using atlas.ti version 9.22 (Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development) between November 2021 and March 2023. Coding and analysis were performed to inductively identify concepts using principles of thematic analysis.23 These concepts were grouped into initial themes and subthemes and then developed and refined the coding until they captured the participants’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to their home dialysis experience. A theoretical framework was developed through process of analysis and comparison of concepts13 using principles of grounded theory.24,25,26 Consensus on the framework was reached after review by study team members to ensure that the findings reflected the full range and depth of the data. Member-checking (returning the data to participants for accuracy) was not conducted.

Results

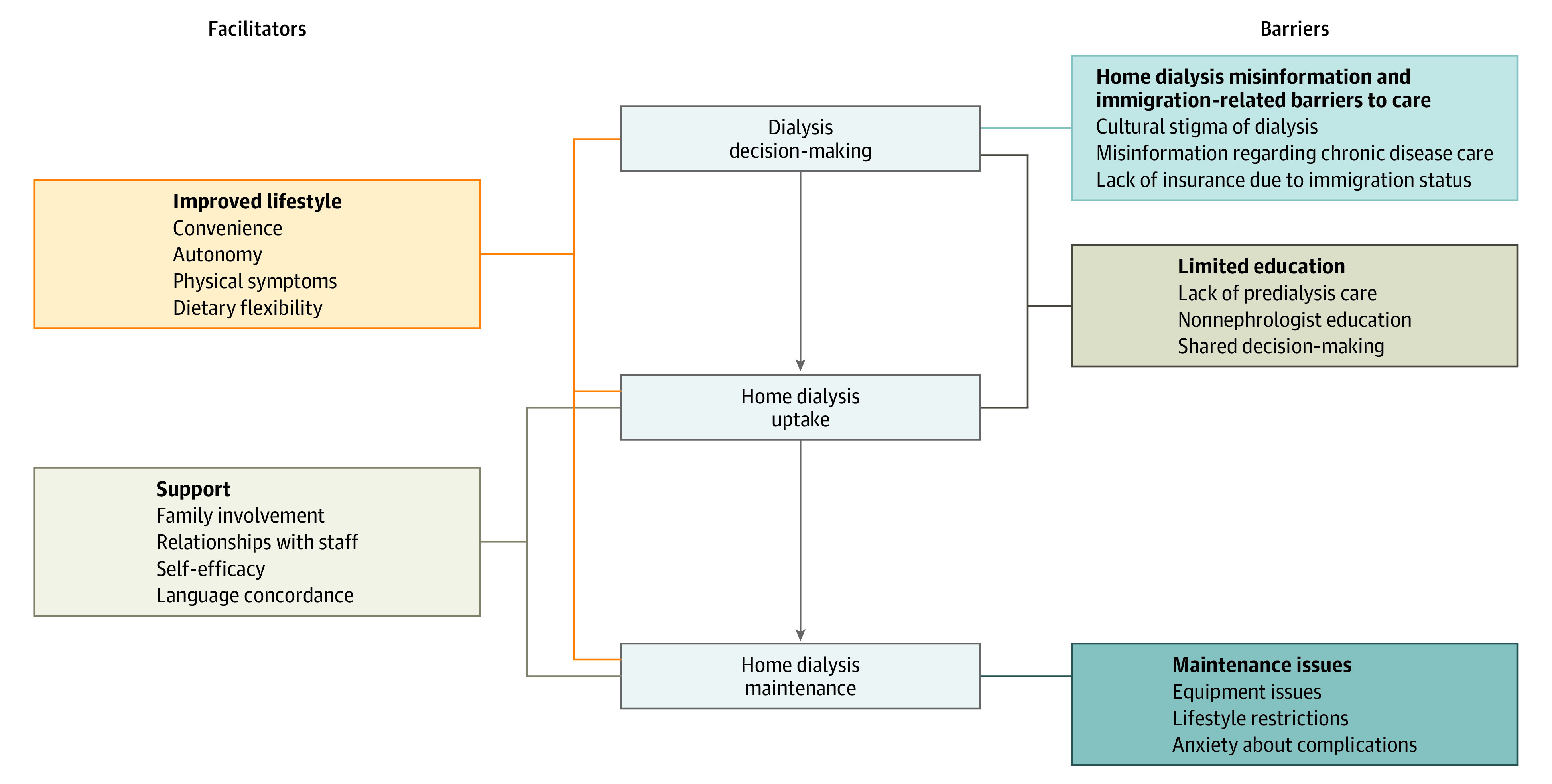

Of the 34 people approached, 27 participants (79%; 17 [63%] female and 10 [37%] male) were interviewed (Table 1). Nonparticipation was due to lack of interest (n = 4), recent kidney transplant (n = 1), patient illness (n = 1), and lack of decision-making capacity per spouse (n = 1). Nineteen participants (70%) were born in Mexico; 22 (81%) were treated with peritoneal dialysis, and 14 (51%) received in-center hemodialysis prior to home dialysis. Twenty (74%) interviews were conducted in Spanish and the mean interview duration was 40 minutes. We identified 5 themes, 3 focused on barriers and 2 focused on facilitators (Table 2). A thematic schema was developed to illustrate associations among the themes (Figure).

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) (N = 27) |

|---|---|

| Age range, y | |

| 20-30 | 1 (4) |

| 31-40 | 6 (22) |

| 41-50 | 7 (26) |

| 51-60 | 11 (41) |

| ≥61 | 2 (7) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 17 (63) |

| Male | 10 (37) |

| Modality type | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 22 (81) |

| Home hemodialysis | 5 (19) |

| Preferred language Spanish | 20 (24) |

| Country of origin | |

| Mexico | 19 (70) |

| United States | 4 (15) |

| Othera | 4 (15) |

| Self-reported limited English proficiency | 16 (60) |

| Married or has a partner | 12 (44) |

| Has children younger than 18 y | 15 (56) |

| >3 People living in home | 20 (74) |

| <High school education (n = 25)b | 6 (22) |

| Working (full or part time) | 10 (37) |

| Total years receiving dialysis, mean (SD) | 4.1 (5.9) |

| Prior history of in-center hemodialysis | 15 (56) |

| Prior history of kidney transplant | 5 (19) |

| Waitlisted for kidney transplant (n = 23)c | 6 (26) |

| Access to kidney physician before starting dialysis | 16 (59) |

| Proximity to home dialysis clinic, mean (SD), min (n = 25)d | 24 (13.2) |

| Self-reported history of diabetes | 10 (37) |

Including Puerto Rico, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.

Two patients reported unsure.

Four patients reported unsure.

Two patients reported unsure.

Table 2. Qualitative Themes, Subthemes, and Illustrative Quotes.

| Themes and subthemes | Quotes (participant ID number) |

|---|---|

| Home dialysis misinformation and immigration-related barriers to care | |

| Cultural stigma of dialysis |

|

| Misinformation regarding chronic disease care |

|

| Lack of health insurance due to immigration status |

|

| Limited dialysis education | |

| Lack of predialysis care |

|

| Nonnephrologist education |

|

| Shared decision-making |

|

| Maintenance of home dialysis | |

| Equipment issues |

|

| Lifestyle restrictions |

|

| Anxiety about complications |

|

| Improved lifestyle | |

| Convenience |

|

| Autonomy |

|

| Physical symptoms |

|

| Dietary flexibility |

|

| Support | |

| Family involvement |

|

| Relationships with staff |

|

| Self-efficacy |

|

| Language concordance |

|

Figure. Thematic Schema Illustrating Associations Between Potential Barriers and Facilitators to Home Dialysis Decision-Making, Uptake, and Maintenance.

Home Dialysis Misinformation and Immigration-Related Barriers to Care

Cultural Stigma of Dialysis

Participants described a perception in the Latinx community that people receiving home dialysis are sick, which made participants feel stigmatized. One participant elaborated, “I remember that they used to say, that so-and-so have dialysis, automatically one would say he’s going to die, he’s too sick” (Participant 22). In addition, participants described perceptions of home dialysis being unsafe or dangerous compared with in-center dialysis in their country of origin. One participant, when asked what his family in Mexico thinks about home dialysis, remarked “Nobody would want me to be doing it” (Participant 2).

Misinformation Regarding Chronic Disease Care

Participants felt much of the cultural stigma regarding dialysis was due to lack of information in the community regarding kidney disease and need for regular medical care. One participant elaborated, “It’s just that us Latinos, those of us who speak Spanish, we don’t go to see the doctor. We go to the doctor when we are already sick” (Participant 11).

Lack of Health Insurance Due to Immigration Status

Undocumented participants reported that lack of health care insurance led to uncertainty about dialysis treatment options. One participant commented, “For a Latino, the most worrying thing is not having certainty. When I went to the hospital, I didn’t have insurance because I was illegal…in the first hospital, the doctor told me they couldn’t treat me here in the United States because I am illegal” (Participant 15).

Limited Dialysis Education

Lack of Predialysis Care

Participants reported finding out about their kidney disease at a late stage or when they presented with symptoms. Others reported being told early on about their kidney disease but not understanding the implications of kidney disease progression; they did not know this was an end-stage, progressive disease. Others reported being told about their kidney disease by their primary care doctor but were not referred to specialty care until they started dialysis.

Nonnephrologist Education

Participants reported their nephrologist was not the main mechanism by which they heard about home dialysis. Participants described a range of ways in which they learned about home modality options, including friends, the internet, dialysis social workers and technicians, experience with family members who received home dialysis, and primary care physicians.

Shared Decision-Making

Many participants who received nephrology care before home dialysis (either predialysis or hemodialysis) reported that home dialysis was not discussed with them as an option. One participant said, “It wasn’t a great experience at the beginning and nobody offered nothing other ways, types, not even [peritoneal dialysis], nothing. They just put [you] into a center and you know how it is” (Participant 23).

Maintenance of Home Dialysis

Equipment Issues

Participants described navigating issues with the peritoneal dialysis catheter and dialysis machine, and maintaining hygiene, such as infections and machine malfunctions. Concerns with space or physical limitations were also mentioned.

Lifestyle Restrictions

Participants reported multiple ways in which home dialysis affected their day to day life, including hygiene, frequency of treatments, home dialysis affecting other medical issues, and maintaining body image. One participant described how the weight restrictions in peritoneal dialysis affected their inability to work: “I can’t carry heavy things. I mean, my job, I used to work in construction” (Participant 22).

Anxiety About Complications

Participants recalled feeling anxiety and stress with home dialysis. Some of the concerns mentioned were fear of a bad outcome at home, fear of an infection, or worry that they would not be able to perform dialysis independently.

Improved Lifestyle

Convenience

The convenience and flexibility of doing dialysis on their own schedules was a major motivator for participants. In particular, participants appreciated that they could modify their home dialysis schedules. One participant noted, “There’s flexibility to change my days, this is very difficult at the center, you have your schedule over there, a fixed schedule and you have to manage” (Participant 14).

Autonomy

Participants felt home dialysis offered a degree of control and autonomy over their treatments. Participants felt that administering their own treatment made them feel in control of their own disease. As one participant noted, “[When] I start putting my needles in, I start doing my treatments alone. I connected and disconnected myself. So, that gave me a lot of pride and independence” (Participant 23). Participants also felt that an advantage of home dialysis was more time with family. One participant said they opted for home dialysis, as “I have more time here at home with my child” (Participant 17). Many participants reported they chose home dialysis as it would allow them to keep working and support their families. One participant commented, “How was I going to survive, I couldn’t stop working…I really like dialysis at home because I can work” (Participant 16).

Physical Symptoms

Participants said that their symptom burden from kidney disease improved with home dialysis. Those who previously received in-center hemodialysis mentioned less fatigue and fewer symptoms of hypotension with home dialysis treatment. Participants reported that past negative experiences with hemodialysis, such as fatigue, feeling cold and uncomfortable, and having issues with their vascular access or needles, motivated them to opt for home dialysis.

Dietary Flexibility

Participants were glad to have a less restrictive diet compared with the chronic kidney disease or in-center hemodialysis diet, which allowed for more traditional Latinx foods, some of which are high in potassium. Despite this, many described difficulty in restricting their portion sizes and dairy intake. As one participant noted, “You know how we Latinos are. We are not full with a small portion, and we want more and more…but anyway, we learn, because in a month I have barely eaten cream or cheese, and I really like my wife to make me green enchiladas, or mole enchiladas, and I put in a lot of onion and cream” (Participant 11).

Support

Family Involvement

Participants noted their caregivers and families were involved by attending clinic visits to learn about treatment options. Most participants reported their family supported them in home dialysis either directly (et, setting up the machine) or indirectly (eg, driving them to appointments and providing childcare or emotional support). Many felt their family’s support was invaluable in their home dialysis treatment.

Relationships With Staff

Once referred to the home dialysis clinic, participants reported that their experience going through home dialysis training was helpful, and they felt supported and reassured by the home dialysis training team. Many described that going through this training gave them confidence and helped to ease their anxiety. Multiple participants described having close relationships with the home dialysis clinic staff. As one participant put it, “It feels like they’re my family in reality…they helped me out and everything” (Participant 20). Participants also felt supported by the clinic in navigating ancillary needs, such as dialysis supplies, food, and insurance.

Self-Efficacy

Participants described advocating for their own care to overcome barriers to home dialysis education and treatment. Some participants reported they did their own research to advocate for their choice modality. One participant described moving to a different state in order to be accepted into a home hemodialysis program. Another described advocating to be changed back to peritoneal dialysis after undergoing temporary hemodialysis treatment in a rehabilitation center. Many described the importance of having a resilient attitude in overcoming fear and complications with home dialysis, following instructions, and being adherent with the training and treatments.

Language Concordance

Spanish-speaking participants felt they received adequate language concordant information from the home dialysis clinic during training and home dialysis treatment. The written materials and guides were in Spanish, and some clinics had language concordant staff while others used video or phone interpreters.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to characterize the facilitators and barriers to home dialysis decision-making, uptake, and maintenance experienced by a group of Latinx people receiving home dialysis. Facilitators of home dialysis included family caregiver and staff support with dialysis, as well as motivations for an improved lifestyle, especially in terms of working and spending time with family. Major challenges to home dialysis for Latinx participants in our study were misinformation and stigma surrounding home dialysis within the Latinx community and poor education regarding modalities. Our findings corroborate known motivators for home dialysis in non-Latinx populations that have not been described in Latinx groups (eg, flexibility, autonomy, and avoidance of hemodialysis)10,13,14,15,16 and barriers to home dialysis (eg, inadequate modality education, lifestyle restrictions, and issues with health care navigation)7,27,28 but also identified barriers to home dialysis that are potentially more unique to this population, such as dialysis stigma, misinformation about chronic disease care, and immigration status creating barriers to education and access. Increasing the use of home dialysis is a national priority; yet the models under the Advancing American Kidney Health initiative do not address many underlying factors affecting home dialysis uptake, such as the effects of poor predialysis education, cultural misinformation, and clinician-patient trust. An understanding of the challenges faced by Latinx populations pursuing home dialysis is important to inform culturally tailored strategies to reduce disparities in this population.

Latinx participants in our study received information about home dialysis from nonnephrologists, such as their primary care doctor, emergency department, and other community sources. Participants also described misinformation in the Latinx community that led to not seeking care as well as limited shared decision-making with their clinicians with respect to dialysis modality. Lack of predialysis education by nephrologists is a major barrier to home dialysis, as it limits timely dialysis decision-making and home dialysis training and preparation.29,30 Peritoneal dialysis is more often chosen when patients have received adequate modality education,29 but Latinx groups are less likely to receive adequate education compared with non-Latinx White individuals.2,31 Culture-concordant shared decision-making approaches has been shown to be important for Latinx populations navigating decisions such as contraceptive use,32 diabetes care,33 breast cancer,34 and palliative care.35 It is possible that lack of culture-concordant shared dialysis decision-making, combined with misinformation and dialysis stigma within the Latinx community limiting care seeking and earlier education, may contribute to low home dialysis uptake in Latinx groups in the United States.

The central role of family in Latinx culture regarding social support and family-oriented health care decisions is important to consider for dialysis modality decision-making.35 Participants in our study reported their families supported their modality decision and helped them with dialysis either directly or indirectly, which were likely a facilitator to their success with home dialysis and may be missing for Latinx individuals who do not take up home dialysis. Lack of caregiver support is a commonly cited barrier for non-Latinx populations, observed with higher frequency in low income households.5 Many described working to support family and being with family as a motivator to home dialysis that is important to their Latinx identity. Further, our finding of Latinx diet flexibility as a facilitator to home dialysis uptake is important to maintain close family connections and cultural identities through meal sharing, an important characteristic of Latinx culture.36,37 These findings stress the importance of including Latinx families in home dialysis education, training, and treatment. Understanding the values motivating a patient’s dialysis modality decision-making may help frame the discussion regarding benefits of home dialysis that are unique to Latinx individuals’ cultural identity.

Participants in our study felt the home dialysis clinic staff supported and listened to them, and they noted that education and resources were supplied in their preferred language, which was important to maintenance of home dialysis treatment. In contrast, Latinx and Black people with kidney disease have reported mistrust and discrimination by their dialysis medical clinicians and system.38,39,40 The close and trusting relationships reported by participants in our study illustrate the Latinx cultural value of personalismo, “a value for interacting with persons with whom one has a warm, caring, and trusting personal relationship.”41 This likely played a role in successful maintenance of home dialysis therapy. Establishing a close relationship between dialysis staff and patients may be critical to establishing the trust necessary for Latinx people to feel confident and safe to perform home dialysis.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. The transferability of these findings to other dialysis centers or ethnic groups is uncertain. The sample in Texas comprised primarily individuals with undocumented immigration status, which may have led to a difference in structural barriers described by the participants included in the study. Additionally, what is referred to as the Latinx ethnic group is highly heterogeneous. Most of the participants in our study were of Mexican descent, which limits transferability to other Latinx communities. Moreover, as the participants in this study were successful with home dialysis uptake and maintenance, we were not able to elicit perspectives of individuals who did not commence or continue with home dialysis or who faced structural barriers impairing uptake. Future research including Latinx people who are not receiving home dialysis is critical to understanding additional barriers to home dialysis in this population.

Conclusions

Overall, the Latinx people receiving home dialysis in this study received limited predialysis education and misinformation regarding home dialysis and yet were self-advocates with strong family and clinic support, which may have facilitated success with their uptake and maintenance of home dialysis treatment. As such, efforts toward improving home dialysis disparities for Latinx groups must focus on early culture concordant modality education—especially those that build patient activation and self-advocacy while incorporating Latinx cultural values.

eAppendix. Participant interview guide

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases . United States Renal Data System annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2022

- 2.Shen JI, Chen L, Vangala S, et al. Socioeconomic factors and racial and ethnic differences in the initiation of home dialysis. Kidney Med. 2020;2(2):105-115. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra R, Soohoo M, Rivara MB, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in use of and outcomes with home dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(7):2123-2134. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Wasse H. Patient awareness and initiation of peritoneal dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(2):119-124. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash S, Perzynski AT, Austin PC, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and barriers to peritoneal dialysis: a mixed methods study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(10):1741-1749. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11241012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner DE, Meyer KB. Home dialysis in the United States: to increase utilization, address disparities. Kidney Med. 2020;2(2):95-97. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones LA, Gordon EJ, Hogan TP, et al. Challenges, facilitators, and recommendations for implementation of home dialysis in the Veterans Health Administration: patient, caregiver, and clinician perceptions. Kidney360. 2021;2(12):1928-1944. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000642021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luxardo R, Ceretta L, González-Bedat M, Ferreiro A, Rosa-Diez G. The Latin American Dialysis and Renal Transplantation Registry: report 2019. Clin Kidney J. 2021;15(3):425-431. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfab188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson BM, Akizawa T, Jager KJ, Kerr PG, Saran R, Pisoni RL. Factors affecting outcomes in patients reaching end-stage kidney disease worldwide: differences in access to renal replacement therapy, modality use, and haemodialysis practices. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):294-306. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30448-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizzolo K, Cervantes L, Shen JI. Racial and ethnic disparities in home dialysis use in the United States: barriers and solutions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(7):1258-1261. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2022030288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services . Exemptions (2018). Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/common-rule-subpart-a-46104/index.html

- 13.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Transaction; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukla AM, Hinkamp C, Segal E, et al. What do the US advanced kidney disease patients want? comprehensive pre-ESRD patient education (CPE) and choice of dialysis modality. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver MJ, Garg AX, Blake PG, et al. Impact of contraindications, barriers to self-care and support on incident peritoneal dialysis utilization. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(8):2737-2744. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golper TA, Saxena AB, Piraino B, et al. Systematic barriers to the effective delivery of home dialysis in the United States: a report from the Public Policy/Advocacy Committee of the North American Chapter of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(6):879-885. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fissell RB, Cavanaugh KL. Barriers to home dialysis: unraveling the tapestry of policy. Semin Dial. 2020;33(6):499-504. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan CT, Wallace E, Golper TA, et al. Exploring barriers and potential solutions in home dialysis: an NKF-KDOQI conference outcomes report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(3):363-371. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan CT, Collins K, Ditschman EP, et al. Overcoming barriers for uptake and continued use of home dialysis: an NKF-KDOQI conference report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(6):926-934. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowen GA. Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(3):12-23. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?:an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59-82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A. Qualitative Research Methods. SAGE Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corbin JMSA. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13:3-21. doi: 10.1007/BF00988593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. SAGE Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong A, Winkelmayer WC, Craig JC. Qualitative research in CKD: an overview of methods and applications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(3):338-346. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong A, Lesmana B, Johnson DW, Wong G, Campbell D, Craig JC. The perspectives of adults living with peritoneal dialysis: thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(6):873-888. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baillie J, Lankshear A. Patient and family perspectives on peritoneal dialysis at home: findings from an ethnographic study. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(1-2):222-234. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devoe DJ, Wong B, James MT, et al. Patient education and peritoneal dialysis modality selection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(3):422-433. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shukla AM, Bozorgmehri S, Ruchi R, et al. Utilization of CMS pre-ESRD Kidney Disease Education services and its associations with the home dialysis therapies. Perit Dial Int. 2021;41(5):453-462. doi: 10.1177/0896860820975586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purnell TS, Bae S, Luo X, et al. National trends in the association of race and ethnicity with predialysis nephrology care in the United States from 2005 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2015003. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carvajal DN, Klyushnenkova E, Barnet B. Latina contraceptive decision-making and use: the importance of provider communication and shared decision-making for patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(9):2159-2164. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson JA, Rosales A, Shillington AC, Bailey RA, Kabir C, Umpierrez GE. Improving access to shared decision-making for Hispanics/Latinos with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:619-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawley ST, Janz NK, Hamilton A, et al. Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):363-370. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cervantes L, Jones J, Linas S, Fischer S. Qualitative interviews exploring palliative care perspectives of Latinos on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):788-798. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10260916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caballero AE. Cultural competence in diabetes mellitus care: an urgent need. Insulin. 2007;2(2):80-91. doi: 10.1016/S1557-0843(07)80019-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caballero AE. Understanding the Hispanic/Latino patient. Am J Med. 2011;124(10)(suppl):S10-S15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkins KA, Keddem S, Bekele SB, Augustine KE, Long JA. Perspectives on racism in health care among Black veterans with chronic kidney disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2211900. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.11900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cervantes L, Fischer S, Berlinger N, et al. The illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529-535. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cervantes L, Rizzolo K, Carr AL, et al. Social and cultural challenges in caring for Latinx individuals with kidney failure in urban settings. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2125838. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis RE, Lee S, Johnson TP, Rothschild SK. Measuring the elusive construct of personalismo among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and Cuban American adults. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2019;41(1):103-121. doi: 10.1177/0739986318822535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Participant interview guide

Data Sharing Statement