Key Points

Question

Is sacrospinous hysteropexy noninferior to the Manchester procedure for treatment of uterine descent that is not beyond the hymen?

Findings

This noninferiority randomized clinical trial included 434 patients with uterine descent that did not protrude beyond the hymen. The composite outcome of success after 2 years was lower for sacrospinous hysteropexy compared with the Manchester procedure (ie, did not meet noninferiority criteria).

Meaning

In patients with uterine descent that did not protrude beyond the hymen, the lower composite 2-year outcomes are consistent with inferiority of sacrospinous hysteropexy compared with the Manchester procedure.

Abstract

Importance

In many countries, sacrospinous hysteropexy is the most commonly practiced uterus-preserving technique in women undergoing a first operation for pelvic organ prolapse. However, there are no direct comparisons of outcomes after sacrospinous hysteropexy vs an older technique, the Manchester procedure.

Objective

To compare success of sacrospinous hysteropexy vs the Manchester procedure for the surgical treatment of uterine descent.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multicenter, noninferiority randomized clinical trial conducted in 26 hospitals in the Netherlands among 434 adult patients undergoing a first surgical treatment for uterine descent that did not protrude beyond the hymen.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to undergo sacrospinous hysteropexy (n = 217) or Manchester procedure (n = 217).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of success, defined as absence of pelvic organ prolapse beyond the hymen in any compartment evaluated by a standardized vaginal support quantification system, absence of bothersome bulge symptoms, and absence of prolapse retreatment (pessary or surgery) within 2 years after the operation. The predefined noninferiority margin was 9%. Secondary outcomes were anatomical and patient-reported outcomes, perioperative parameters, and surgery-related complications.

Results

Among 393 participants included in the as-randomized analysis (mean age, 61.7 years [SD, 9.1 years]), 151 of 196 (77.0%) in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group and 172 of 197 (87.3%) in the Manchester procedure group achieved the composite outcome of success. Sacrospinous hysteropexy did not meet the noninferiority criterion of −9% for the lower limit of the CI (risk difference, −10.3%; 95% CI, −17.8% to −2.8%; P = .63 for noninferiority). At 2-year follow-up, perioperative outcomes and patient-reported outcomes did not differ between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

Based on the composite outcome of surgical success 2 years after primary uterus-sparing pelvic organ prolapse surgery for uterine descent, these results support a finding that sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester procedure.

Trial Registration

TrialRegister.nl Identifier: NTR 6978

This randomized trial assesses the effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy vs Manchester procedure on a composite outcome of surgical success at 2 years among patients undergoing a first surgical treatment for uterine descent that did not protrude beyond the hymen.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is a common health problem, often associated with uterine prolapse; the estimated lifetime risk for pelvic organ prolapse surgery is 11% to 20%.1,2,3 Worldwide, the primary surgical approach for pelvic organ prolapse treatment is transvaginal.4 The most commonly performed procedure worldwide includes removal of the uterus and suspension of the upper vagina,2,3 although there are geographic variations in surgical preferences.4,5,6 In the last decade, surgical techniques that preserve the uterus are becoming more common.5,7 The current practice in the Netherlands for all stages of uterine prolapse is uterus-sparing surgery, and a slight majority (60%) of gynecologists prefers sacrospinous hysteropexy over the Manchester procedure as first choice of procedure in the primary treatment of uterine descent.8 The largest study with the longest follow-up is a randomized clinical trial that documented lower rates of anatomic prolapse recurrence at 5 years with uterine preservation (sacrospinous hysteropexy) compared with vaginal hysterectomy and repair.9 Two systematic reviews align with that trial’s results.10,11

An older uterus-sparing surgery, the Manchester procedure, was recently defined in an international consensus statement as amputation of the uterine cervix and plication of the uterosacral ligaments extraperitoneally above the remaining cervical stump.12 The increasing numbers of Manchester procedure13,14,15,16 studies suggest growing popularity. Prior studies, however, describe varying techniques and are based on observational studies.17,18 There has been no direct comparison of the outcomes of the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy. The aim of this study was to compare the anatomical and patient-reported outcomes of the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy at 2 years after surgery.19 We hypothesized that the composite surgical outcome of sacrospinous hysteropexy is noninferior to the Manchester procedure in patients undergoing surgery for treatment of uterine descent that did not protrude beyond the hymen.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a multicenter, randomized, unblinded clinical trial. This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Arnhem-Nijmegen (file number 2017-3443) and all local ethical committees in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.20 Board members from the Dutch Bekkenbodem4all patient support group participated in the development of the study protocol. All participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion and randomization. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 121 and the statistical analysis plan in Supplement 2. The 72 participating gynecologic surgeons were required to have performed at least 20 of both study procedures, with a minimum of 10 procedures each in the 2 years prior to study start. Both procedures were commonly performed in the participating 26 hospitals prior to the study. The participating hospitals represent almost half of the hospitals in the Netherlands performing these types of surgery. To standardize techniques, prior to study commencement, all participating surgeons reached agreement on specific techniques (eAppendix in Supplement 3). Details regarding the participating centers and gynecologic surgeons are shown in eTable 7 in Supplement 3.

Participants and Recruitment

Eligible patients included individuals aged 18 years or older planning to undergo a first surgery for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in any stage, with uterine descent, who had Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) point D22 at or proximal to −1 cm. During the protocol design, Dutch (uro)gynecologists were queried to reach consensus on the prolapse quantification that would facilitate equipoise. POP-Q point D was chosen as a measure that allows to differentiate between (1) presumed failure of the uterine suspensory ligaments and (2) cervical elongation.22 The eAppendix in Supplement 3 provides additional details.

Potential participants were excluded if they had a history of pelvic floor surgery, a need for concomitant anti-incontinence surgery, preferred uterus removal, had a contraindication to uterus preservation (eg, abnormal bleeding, [pre]malignancy), had insufficient fluency with the Dutch language, or wished future childbearing.

Presurgical Papanicolaou testing and/or endometrial biopsy were done when clinically indicated.

Data on ethnicity were collected via questionnaire in which participants chose from fixed ethnicity categories; these data were collected to provide information to readers on the generalizability of outcomes.

Randomization and Interventions

Participants were randomly allocated by a research nurse on site using a web-based randomization interface (CastorEDC) in a 1:1 ratio, with use of dynamic block-designed randomization with blocks of 2, 4, and 6. Neither the recruiters nor the trial project group was able to access the randomization sequence.

The intervention was not blinded as a difference in counseling or patient preference was not expected. An electronic case record form in CastorEDC was used to collect (peri)operative information, including the surgical steps and any protocol violations during the follow-up period.

In sacrospinous hysteropexy, the uterus is fixated unilaterally to the right sacrospinous ligament with 2 nonabsorbable sutures running through the posterior side of the cervix. The Manchester procedure consists of extraperitoneal plication of the uterosacral ligaments at the posterior side of the uterus and amputation of the cervix; furthermore, the cardinal ligaments are plicated on the anterior side of the cervix. The eAppendix in Supplement 3 provides an extensive description of the techniques, and Figure 1 illustrates the techniques of the 2 study procedures.

Figure 1. Illustration of Sacrospinous Hysteropexy and Manchester Procedure Techniques.

Measurements and Procedures

Physical examination, including prolapse quantification22 and history taking, took place preoperatively and at 6 weeks, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively. A trained professional who had not been that participant’s surgeon performed the postoperative prolapse quantification measurements.

Patient-reported questionnaires were completed electronically preoperatively and at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months postoperatively.21 The following validated questionnaires in Dutch were used: EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level Questionnaire,23 Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory 20,24 Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire 7,25 Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire–IUGA Revised,26 Productivity Cost Questionnaire and Medical Consumption Questionnaire,27 and Patient Global Impression of Improvement.28

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of surgical success, defined as absence of vaginal prolapse beyond the hymen, absence of bothersome bulge symptoms, and absence of retreatment of recurrent prolapse (pessary or surgery) within 2 years of follow-up.29 The absence of bulge symptoms was defined as a negative response to the question “Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in your vaginal area?” (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory 20, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory 6 subdomain, question 3; score, 0). All 3 criteria were required to categorize the primary outcome as “success.” The protocol included 6 prespecified secondary outcomes including anatomical outcomes, questionnaire scores, perioperative parameters, surgery-related morbidity, surgery-related complications, and costs. Patient Global Impression of Improvement scores were reported as absolute scores and as number of patients reporting “(very) much improved.”28

Sample Size Calculation and Noninferiority Margin

The sample size calculation was based on the composite outcome of success after 2 years of follow-up.21 A success rate of 89% for both sacrospinous hysteropexy and the Manchester procedure was expected, with a predefined noninferiority margin of 9%. This noninferiority margin was chosen to align with previous relevant pelvic organ prolapse studies that used noninferiority margins of 7% and 10%.30,31 Success rates of the procedures varied between 85% and 100% (sacrospinous hysteropexy) and 93% and 100% (Manchester procedure), with a mean rate of 89%.30,32 The SAVE-U trial used a 7% margin for anatomic failure within a single vaginal compartment. A power of 80% and a significance level of α = .025 resulted in a sample size of 193 per group. With an expected loss to follow-up of 10%, we planned to enroll 430 participants.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses followed the prespecified statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2). The Farrington-Manning test was used to test the noninferiority hypothesis for the primary outcome. If the lower limit of the 95% CI did not exceed the prespecified noninferiority margin of −9%, the null hypothesis would be rejected, and sacrospinous hysteropexy would be considered noninferior to the Manchester procedure. The main statistical analysis was performed in both the as-randomized and per-protocol populations, and noninferiority needed to be demonstrated in both the as-randomized and per-protocol analyses to confirm the hypothesis. The population as randomized consisted of all patients for whom primary outcome data (prolapse quantification, questionnaire, and information concerning reintervention for recurrent prolapse) were complete at 24 months of follow-up, irrespective of the treatment received. In the per-protocol population, patients with major protocol violations were excluded from analysis. Protocol violations were defined as deviations from the approved protocol based on the potential impact on outcomes; violations were categorized as minor or major. These were predefined when possible and otherwise decided by research group consensus.

In the primary analysis, no adjustment for covariates was applied. Consistent with plans outlined in the statistical analysis plan, a subgroup analysis for the primary outcome was performed (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). For the primary outcome, complete case analysis was performed. We did not perform imputation for missing data in secondary outcomes because the dropout rate was below 10% and the missing data were expected to be at random. The analyses were performed with IBM SPSS version 2533 and R version 4.0.3.34

Results

Participants were recruited in 26 participating Dutch hospitals (academic, n = 4; teaching, n = 20; nonteaching n = 2) between July 3, 2018, and February 18, 2020. The median number of participants enrolled per center was 11 (IQR, 5-25). The last follow-up visit took place on September 19, 2022.

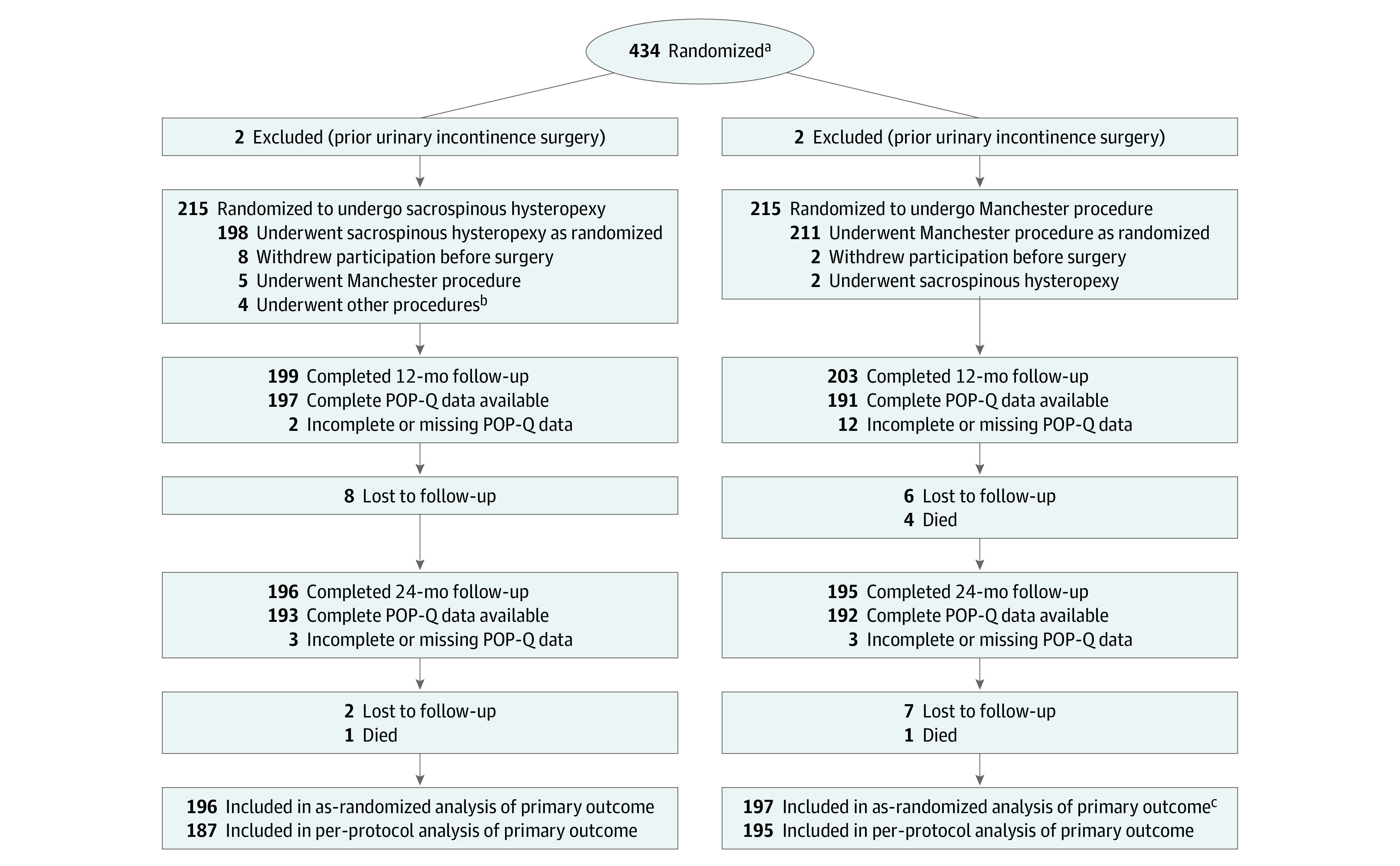

Figure 2 shows the flow of participants randomized to sacrospinous hysteropexy (n = 217) or the Manchester procedure (n = 217). Baseline characteristics in the treatment groups did not differ significantly (Table 1).

Figure 2. Participant Flow.

POP-Q indicates Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification.

aPatients aged 18 years or older with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse planning to undergo a vaginal uterus-preserving operation were screened for inclusion. There were no screening logs of eligible patients maintained at the 26 participating centers. For privacy reasons, the ethics committee did not permit collection of any anonymized data of screened nonparticipants. This made collection of the number of eligible patients prone to missing and double counts.

bOther procedures included vaginal hysterectomy (n = 1), anterior colporrhaphy and midurethral sling (n = 1), anterior and posterior colporrhaphy and perineal repair (n = 1), and posterior colporrhaphy (n = 1).

cTwo patients in the Manchester procedure group did not complete 2-years follow-up but were analyzed as having not met the composite outcome of surgical success. The patients underwent retreatment for recurrent pelvic organ prolapse before loss to follow-up and therefore did meet the criterion for the composite outcome.

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Sacrospinous hysteropexy (n = 215) | Manchester procedure (n = 215) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 61 (55-69) | 63 (56-70) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| African or Caribbean | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| European | 185 (86.0) | 183 (85.1) |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.4) |

| Othera | 25 (11.8) | 26 (12.1) |

| Highest educational level, No. (%) | ||

| Primary or secondary school | 82 (38.1) | 92 (42.8) |

| High school | 74 (34.4) | 77 (35.8) |

| Bachelor’s, master’s, or other academic degree | 55 (25.6) | 45 (20.9) |

| Comorbidities, No. (%)b | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 50 (23.3) | 51 (23.7) |

| Respiratory disease | 25 (11.6) | 17 (7.9) |

| Diabetes | 11 (5.1) | 11 (5.1) |

| Current smoking, No. (%) | 15 (7.0) | 15 (7.0) |

| No. of deliveries, median (IQR), | ||

| Vaginal | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) |

| Cesarean | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) |

| Assisted vaginal | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) |

| Family history of pelvic organ prolapse, No. (%) | 83 (38.6) | 77 (35.8) |

| Postmenopausal, No. (%) | 172 (80.0) | 174 (80.9) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)c | 25.4 (23.3-28.0) | 25.2 (23.2-28.6) |

| POP-Q point D, median (IQR), cm | −4 (−5 to −3) | −4 (−5 to −3) |

| POP-Q stage of uterine prolapse (point C), No. (%)d,e | ||

| 1 | 76 (35.3) | 73 (34.0) |

| 2 | 115 (53.5) | 124 (57.7) |

| 3 | 24 (11.2) | 18 (8.4) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Prolapse beyond hymen, No. (%)e | ||

| Anterior (POP-Q Aa or Ba >0) | 125 (58.1) | 128 (59.5) |

| Apical (POP-Q C >0) | 36 (16.7) | 41 (19.1) |

| Posterior (POP-Q Ap or Bp >0) | 11 (5.1) | 15 (7.0) |

| Overall POP-Q stage, No. (%)d | ||

| 2 | 87 (40.5) | 106 (49.3) |

| 3 | 128 (59.5) | 108 (50.2) |

| 4 | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

Abbreviation: POP-Q, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification.

The category of “other” ethnicity was not further specified.

Comorbidity data were collected at the study inclusion visit and were supplemented by study research nurses through medical record review.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

POP-Q stage 2: most distal prolapse is between 1 cm above and 1 cm beyond hymen; stage 3: most distal prolapse is prolapsed >1 cm beyond hymen but ≤2 cm less than total vaginal length; stage 4: total prolapse.

Degree of prolapse of anterior vaginal wall (Aa and Ba), posterior vaginal wall (Ap and Bp), and uterus or vaginal vault (C) is measured in centimeters both above or proximal to hymen (negative number) or beyond or distal to hymen (positive number), with plane of hymen defined as 0. A represents the descent of a measurement point 3 cm proximal to the hymen on the anterior (Aa) and posterior (Ap) vaginal wall. B is the most descended edge on the anterior (Ba) and posterior (Bp) vaginal wall.

Primary Outcome

The composite outcome for the Manchester procedure was 87.3%, compared with 77.0% for sacrospinous hysteropexy (difference, −10.3%; 95% CI, −17.8% to −2.8%; P = .007) (Table 2). The subcomponent of absence of prolapse beyond the hymen differed by group and was higher in the Manchester procedure group (95.9%) than in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group (86.7%) (difference, −9.2%; 95% CI, −14.7% to −3.7%; P = .001). Sacrospinous hysteropexy did not meet noninferiority criteria in either the as-randomized analysis (P = .65 for noninferiority) or the per-protocol analysis (P = .62 for noninferiority). The lower limit of the 95% CI for the treatment effect excluded zero, consistent with inferiority of sacrospinous hysteropexy.

Table 2. Composite Primary Outcome of Treatment Success for Pelvic Organ Prolapse at 2-Year Follow-Up by As-Randomized and Per-Protocol Analyses.

| Outcome | No./total (%) | Difference, % (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sacrospinous hysteropexy (n = 196) | Modified Manchester (n = 197) | |||

| Composite outcome of surgical success (as randomized)a | 151/196 (77.0) | 172/197 (87.3) | −10.3 (−17.8 to −2.8) | .007 |

| Absence of pelvic organ prolapse beyond hymen | 170/196 (86.7) | 187/195 (95.9) | −9.2 (−14.7 to −3.7) | .001 |

| Absence of bulge symptoms | 179/200 (89.5) | 183/201 (91.0) | −1.5 (−7.3 to 4.3) | .60 |

| Absence of reintervention | 187/199 (94.0) | 195/201 (97.0) | −3.0 (−7.1 to 1.0) | .14 |

| Composite outcome of surgical success (per protocol)a | 145/187 (77.5) | 171/195 (87.7) | −10.2 (−17.7 to −2.6) | .008 |

| Absence of pelvic organ prolapse beyond hymen | 164/187 (87.7) | 185/193 (95.9) | −8.2 (−13.6 to −2.7) | .004 |

| Absence of bulge symptoms | 171/191 (89.5) | 182/199 (91.5) | −1.9 (−7.8 to 3.9) | .52 |

| Absence of reintervention | 178/190 (93.7) | 193/199 (97.0) | −3.3 (−7.5 to 0.9) | .12 |

| Bothersome bulge symptomsb | 21/200(10.5) | 18/201 (9.0) | 1.5 (−4.3 to 7.3) | .60 |

| Without reintervention | 18/197 (9.1) | 14/198 (7.1) | 2.1 (−3.3 to 7.4) | .45 |

| POP-Q stage of uterine prolapse >2c | ||||

| All compartments | 135/196 (68.9) | 119/195 (61.0) | 7.9 (−1.6 to 17.3) | .10 |

| Anterior compartment | 124/196 (63.3) | 87/195 (44.6) | 18.6 (8.9 to 28.4) | <.001 |

| Apical compartment | 6/196 (3.1) | 1/195 (0.5) | 2.5 (−0.1 to 5.2) | .056 |

| Posterior compartment | 22/196 (11.2) | 54/195 (27.7) | −16.5 (−24.1 to −8.8) | <.001 |

| Prolapse beyond the hymend | ||||

| Overall | 26/196 (13.3) | 8/195 (4.1) | 9.2 (3.7 to 14.7) | .001 |

| Anterior (POP-Q Ba >0) | 20/196 (10.2) | 5/195 (2.6) | 7.6 (2.9 to 12.4) | .002 |

| Apical (POP-Q C >0) | 2/196 (1.0) | 0 | 1.0 (−0.9 to 2.9) | .48 |

| Posterior (POP-Q Bp >0) | 4/196 (2.0) | 3/195 (1.5) | 0.5 (−2.1 to 3.1) | .71 |

| Pessary treatmente | ||||

| First postoperative year | 8/200 (4.0) | 5/201 (2.5) | 1.5 (−2.0 to 5.0) | .39 |

| Second postoperative year | 4/199 (2.0) | 3/200 (1.5) | 0.5 (−2.1 to 3.1) | .70 |

| Repeat surgery in operated vaginal compartment | 9/207 (4.3) | 0 | ||

| Anterior compartment | 6/188 (3.2) | 0 | ||

| Apical compartmentf | 7/199 (3.5) | 0 | ||

| Posterior compartment | 1/60 (1.7) | 0 | ||

| Repeat surgery in nonoperated vaginal compartmentg | 2/154 (1.3) | 4/144 (2.8) | −1.5 (−4.7 to 1.7) | .37 |

| Anterior compartment | 1/19 (5.3) | 1/12 (8.3) | −3.1 (−21.7 to 15.5) | .75 |

| Posterior compartment | 1/145 (0.7) | 3/141(2.1) | −1.4 (−4.2 to 1.3) | .30 |

Abbreviation: POP-Q, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification.

Composite outcome of surgical success defined as absence of pelvic organ prolapse beyond the hymen in any compartment, absence of bulge symptoms, and absence of reoperation or pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse.

Bulge symptoms are defined as a positive response to the question “Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in your vaginal area?” (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory 20, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory 6 domain, question 3; score, 0).

POP-Q stage 2: most distal prolapse is between 1 cm above and 1 cm beyond hymen and includes these values; stage 3: most distal prolapse is prolapsed more than 1 cm beyond hymen but no further than 2 cm less than total vaginal length; stage 4: total prolapse.

See footnote d in Table 1 for description of prolapse definitions.

Pessary treatment starting at some point during the first or second postoperative year.

Repeat surgery for recurrent prolapse in the apical compartment after sacrospinous hysteropexy: cervical amputation (n = 1), modified Manchester procedure (n = 3), robot-assisted sacropexy (n = 3); there were no repeat surgeries for recurrent prolapse in the apical compartment after Manchester procedure.

There were no repeat surgeries in nonoperated apical compartments among patients who had no uterus suspension during the index surgery (which was not according to randomization, ie, a protocol violation).

Secondary Outcomes

No significant group differences were found for perioperative outcomes, patient-reported outcomes, or POP-Q measurements (eTables 1, 2A, and 2B in Supplement 3). Bothersome bulge symptoms were reported in 21 of 200 patients (10.5%) after sacrospinous hysteropexy and in 18 of 201 (9.0%) after Manchester procedure. Bothersome bulge symptoms without any reintervention for pelvic organ prolapse occurred in 18 of 197 patients (9.1%) after sacrospinous hysteropexy and in 14 of 198 (7.1%) after Manchester procedure at 2 years of follow-up. The Patient Global Impression of Improvement scores did not differ between the 2 groups; after 2 years, 156 of 195 patients (80.0%) in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group and 160 of 195 (82.1%) in the Manchester procedure group reported a (very) much improved situation compared with before the operation.

No participants in the Manchester procedure group underwent reoperation for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence in a previously operated vaginal compartment compared with 9 (4.3%) in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group. In the first year after surgery, pessary use occurred among 8 (4.0%) patients after sacrospinous hysteropexy and 5 (2.5%) patients after Manchester procedure. In the second year, 4 of those patients underwent a reoperation, 5 continued pessary use, and 4 stopped using a pessary.

eTable 4 in Supplement 3 shows data on surgical procedures and perioperative outcomes. Following Manchester procedure, 164 (80.4%) of the amputated cervical specimens underwent histological examination. Four patients had abnormal cervical histology findings, including 1 finding of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 in a patient who had not had a preoperative Papanicolaou test. No (pre)malignancies were detected during follow-up.

Protocol Violations and Adverse Events

Two patients in each group (0.9%) were excluded after randomization because they met a predefined exclusion criterion at randomization. Major protocol violations occurred among 12 participants, including incorrect procedures (2 with sacrospinous hysteropexy instead of Manchester procedure, 5 with Manchester procedure instead of sacrospinous hysteropexy, and 4 with a nonstudy procedure instead of sacrospinous hysteropexy [1 vaginal hysterectomy and 3 anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy without apical reconstruction]). One patient received concomitant sphincter ani repair in conjunction with sacrospinous hysteropexy and anterior colporrhaphy. These 12 patients were included in the as-randomized analysis but excluded from the per-protocol analysis.

Table 3 presents the adverse events during the study period. One participant (0.5%) in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group received medical treatment for cardiac arrest at the recovery unit immediately postoperatively, without residual symptoms. Although the event was likely related to surgery/anesthesia, it was not related to a specific study intervention. The reoperation rate for complications was similar in both groups. Severe (n = 1 [0.5%]) or persistent (≥2 months) (n = 3 [1.4%]) buttock pain requiring treatment after sacrospinous hysteropexy occurred in 4 patients, 3 of whom had suture removal (2 days, 4 months, and 6 months after surgery) and underwent another pelvic organ prolapse operation (Manchester procedure: n = 2; vaginal hysterectomy: n = 1). Prior to the suture removal, 2 patients had received a local nerve block, and another patient underwent a local nerve block that relieved symptoms without suture removal.

Table 3. Adverse Events.

| Adverse events | No./total (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sacrospinous hysteropexy (n = 207) | Manchester procedure (n = 213) | |

| Participants with serious adverse eventa | 9 (4.7) | 11 (5.1) |

| Deathb | 1/207 (0.05) | 5/213 (2.3) |

| Likely to be related to surgeryc | 0 | 1/213 (0.5) |

| Not related to surgery | 1/207 (0.5) | 4/213 (1.9) |

| Intraoperative period | ||

| Injury to adjacent organs | 0 | 0 |

| Blood loss >500 mL | 3/203 (1.5) | 1/213 (0.5) |

| Blood transfusion | 0 | 0 |

| Anesthetic incident | 1/203 (0.5) | 0 |

| Postoperative period | ||

| Infection | ||

| Urinary tract infection (<6 wk postoperatively) | 16/205 (7.8) | 24/209 (11.5) |

| Temperature >38 °C measured twice in 12 h | 3/205 (1.5) | 1/209 (0.5) |

| Wound infection | 2/207(1.0) | 0 |

| Other infectionsd | 3/205 (1.5) | 1/209 (0.5) |

| Urinary retention following treatmente | 37/203 (18.2) | 25/204 (12.3) |

| Clean intermittent self-catheterization | 25/36 (69.4) | 15/23 (65.2) |

| Foley catheter | 17/36 (47.2) | 9/23 (39.1) |

| Foley catheter and clean intermittent self-catheterization | 7/36 (19.4) | 2/23 (8.7) |

| No. of days, median (IQR) | 7 (3-9) | 6 (2-10) |

| Opiate use >2 d after surgery | 6/207 (2.9) | 1/212 (0.5) |

| Bleeding | ||

| Delayed hemorrhagef | 2/207 (1.0) | 2/212 (0.9) |

| Hematoma | 2/207 (1.0) | 2/212 (0.9) |

| Reoperation for reason other than pelvic organ prolapseg | 4/207 (1.9) | 2/212 (0.9) |

| Suture removal | 3/207 (1.4) | NA |

| Hemorrhage needing surgery | 1/207 (0.5) | 2/212 (0.9) |

| Rehospitalization for reason other than pelvic organ prolapseg | 7/207 (3.4) | 4/212 (1.9) |

| Urinary retention | 4/207 (1.9) | 0 |

| Infectionh | 3/207 (1.4) | 1/212 (0.5) |

| Suture removali | 2/207 (1.0) | 0 |

| Delayed hematoma (needing surgery) | 0 | 1/212 (0.5) |

| Constipation | 0 | 1/212 (0.5) |

| Buttock painj | 5/207 (2.3) | 0 |

| With treatment(s) | 4/207 (1.9) | 0 |

| Suture removal | 3/207 (1.4) | 0 |

| Nerve block | 3/195 (1.4) | 0 |

| Cervical stenosis | 0 | 2/212 (0.9) |

| With hematometra | 0 | 1/212 (0.5) |

Serious adverse events were defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a trial participant that does not have a causal relationship with the treatment and (1) is fatal and/or (2) is life-threatening and/or (3) makes hospital admission or an extension of the admission necessary and/or causes persistent or significant invalidity or work disability and/or (4) manifests itself in a congenital abnormality or malformation and/or (5) according to the investigator carrying out the research, could have developed into a serious undesired medical event but was prevented due to medical intervention. There were no (gynecological) malignancies found in either group during follow-up.

More details on causes of death are presented in eTable 6 in Supplement 3.

Death related to surgery was defined as a cause of death with a causal relationship to the surgery.

Other infections include COVID-19 infection with hospitalization (n = 1), infected hematoma (n = 1), and pyelonephritis (sacrospinous hysteropexy: n = 1; Manchester procedure: n = 1).

Repetitive greater than 150-mL residual urine (according to local protocol) or prolonged catheterization (more than 24 hours after first removal of Foley catheter, with no need for treatment) (sacrospinous hysteropexy: n = 1; Manchester procedure: n = 2).

Delayed hemorrhage defined as that which occurred after leaving the operating room.

Reoperations and rehospitalizations for reasons other than pelvic organ prolapse are not included here but are shown in Table 2.

Infection due to vaginal abscess (n = 1), infected hematoma (n = 1), and pyelonephritis (n = 2).

Two patients required rehospitalization for suture removal. One case of suture removal took place 2 days postoperatively before discharge (and therefore required no rehospitalization).

Includes only patients with buttock pain that required extra outpatient visits or (re)treatment.

Two participants had cervical stenosis after Manchester procedure, which became evident when they experienced postmenopausal bleeding (n = 1) or dysmenorrhea with hematometra (n = 1).

During the study period, 6 patients died (sacrospinous hysteropexy: n = 1 [0.5%]; Manchester procedure: n = 5 [2.3%]) (eTable 5 in Supplement 3). One patient (0.5%) died 5 weeks after Manchester procedure due to a suspected massive pulmonary embolism. The incident is plausibly related to surgery, but unlikely to be related to the specific study intervention. The deaths of the other 5 patients were not likely to be study related (malignancy [n = 2], Alzheimer disease [n = 1], cardiovascular incident [n = 1], and COVID-19 [n = 1]).

Discussion

In this large, multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing 2 uterus-sparing pelvic organ prolapse operations in patients undergoing their first surgical treatment, patients who underwent the Manchester procedure had a better composite outcome of success after 2-year follow-up, consistent with inferiority of sacrospinous hysteropexy.

Scandinavian registry studies report on large cohorts of pelvic organ prolapse operations, including uterus-sparing techniques.35 The most recent study by Brunes et al36 involving a Swedish registry reported that sacrospinous hysteropexy (n = 913) was associated with more complications (according to Clavien-Dindo classification) after 1 year (adjusted odds ratio, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.6-2.6) compared with the Manchester procedure (n = 1807). That finding was not confirmed in the present study. Our finding of no cervical or endometrial carcinoma during follow-up aligns with other studies that show that the risk of malignancy after uterus-sparing surgery is low (0.0%-1.1%).37,38,39,40,41

Pelvic organ prolapse recurrence in the anterior (ie, bladder) and posterior (ie, bowel) vaginal compartments differed by group. The risk of anterior recurrence was higher in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group. Previous studies have documented anterior compartment recurrences as a relevant problem after sacrospinous hysteropexy, occurring in up to 57% of patients.30,42,43 This high recurrence rate may be explained by the unphysiological dorsal direction of the vagina due to the fixation of the cervix, which results in more pressure on the anterior vaginal wall.

Prolapse recurrence in the posterior compartment of stage 2 or higher (ie, less descent than beyond the hymen) was higher in the Manchester procedure group. Findings from the SAVE-U study demonstrated that sacrospinous hysteropexy protects against posterior compartment recurrence compared with vaginal hysterectomy.44 As prolapse beyond the hymen is associated with symptoms, this may explain why the difference in posterior compartment prolapse has not (yet) led to a difference in reoperations in this study.29,45 Our findings highlight the need for rigorous assessment of this research question.

The risk of cervical canal stenosis after amputation of the cervix with the Manchester procedure was low (n = 2 [0.9%]). A prior study in young women reported a high rate of obstruction (11%), although the number of procedures needed for stenosis treatment was very low (0.5%).40 Other studies reported a similar low risk of obstruction (0.7%-3.3%).46,47,48,49

The strengths of this study include the randomized design, sample size, and broad national participation by almost half of all Dutch centers performing this type of surgery.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, there was no blinding. We know that patient preference does not play a major role in the choice for these 2 interventions.50 Since subjective patient-reported outcomes were part of the primary composite outcome, patient blinding would have been an option. It is unknown whether this would have affected the results. Second, the results are applicable only to patients who do not have uterine prolapse past the hymen (POP-Q point D above the level of the hymen). POP-Q point D represents the attachment and the stretch of the uterosacral ligaments but is normally not the most relevant anatomic measure in everyday clinical practice and is among the least reliable measurements in the POP-Q.51,52,53,54 Nonetheless, it became relevant as an inclusion criterion in this study, in which point D had to be above the level of the hymen to be included. This criterion was chosen based on a discussion of the study design with approximately 35 (uro)gynecologists who opted to participate in the study. The majority of clinicians did not think that descent of the uterine body at or beyond the level of the hymen was an appropriate indication for a Manchester procedure. However, cervical elongation is typically seen as an appropriate indication for a Manchester procedure.55 Third, even though a Manchester procedure is not a contraindication in the higher stages of prolapse,56 individuals with higher-stage prolapse were not included in the present study. When extrapolating from the baseline characteristics of participants in other nationwide studies of pelvic organ prolapse, approximately 90% of individuals with a first pelvic organ prolapse operation were eligible for the present study.30,31,57 Whether a Manchester procedure is a good option in the other 10% of individuals is not known based on this study, but might be interesting for further exploration. Fourth, this study took place in Dutch hospitals only and is a good representation of the Dutch patient population.46,58,59,60,61,62 It is not known whether the outcomes can be extrapolated to populations with other characteristics, but based on comparison of studies, we do not have reason to assume international divergence.3,63 Fifth, the data from this study are limited to the posterior approach to sacrospinous hysteropexy. In the Netherlands, the anterior approach is uncommon and there is no high-grade evidence available on the anterior technique. Nonetheless, the anterior approach might have an influence on outcomes (eg, in the anterior compartment) after sacrospinous hysteropexy. In the present study, the Manchester procedure technique is in line with the international standards.12 It is unknown whether the outcomes are applicable to modifications of the Manchester procedure, such as anterior plication of the ligaments.

Conclusions

Based on a composite outcome of surgical success 2 years after primary uterus-sparing pelvic organ prolapse surgery for uterine descent, these results support a finding that sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester procedure.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Anatomical Outcomes According to POP-Q System Preoperative, 1 and 2 Years Postoperative

eTable 2A. Patient Reported Outcomes Pre-operative and 6 Months Postoperative

eTable 2B. Patient Reported Outcomes 1 and 2 Years Post-operative

eTable 3. Subgroup Analysis for the Primary Outcome (Composite Outcome of Success)

eTable 4. Surgical Procedures and Perioperative Outcomes

eTable 5. Description of Loss to Follow-up

eTable 6. Description of Deaths During Follow-up

eTable 7. Participating Centers and Their Surgeons

eAppendix. Description of Surgical Techniques of SAM Study

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501-506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1096-1100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Boer TA, Slieker-Ten Hove MC, Burger CW, et al. The prevalence and factors associated with previous surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and/or urinary incontinence in a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;158(2):343-349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NICE guidance—urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. BJU Int. 2019;123(5):777-803. doi: 10.1111/bju.14763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enklaar RA, van Ijsselmuiden MN, IntHout J, et al. Practice pattern variation: treatment of pelvic organ prolapse in the Netherlands. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(7):1973-1980. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-04968-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Ijsselmuiden MN, Detollenaere RJ, Kampen MY, et al. Practice pattern variation in surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence in the Netherlands. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(11):1649-1656. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2755-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detollenaere RJ, den Boon J, Kluivers KB, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse and uterine descent in the Netherlands. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(5):781-788. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1934-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enklaar RA, Essers BAB, Ter Horst L, et al. Gynecologists’ perspectives on two types of uterus-preserving surgical repair of uterine descent; sacrospinous hysteropexy versus modified Manchester. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(4):835-840. doi: 10.1007/s00192-020-04568-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational follow-up of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:l5149. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):129-146. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapoor S, Sivanesan K, Robertson JA, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy: review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(9):1285-1294. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3291-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint Writing Group of the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association . Joint report on terminology for surgical procedures to treat pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(3):429-463. doi: 10.1007/s00192-020-04236-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman I, Söderberg MW, Kjaeldgaard A, Ek M. Cervical amputation versus vaginal hysterectomy: a population-based register study. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(2):257-266. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3119-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liebergall-Wischnitzer M, Ben-Meir A, Sarid O, et al. Women’s well-being after Manchester procedure for pelvic reconstruction with uterine preservation: a follow-up study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(6):1587-1592. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2195-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skiadas CC, Goldstein DP, Laufer MR. The Manchester-Fothergill procedure as a fertility sparing alternative for pelvic organ prolapse in young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19(2):89-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q, Wu N, Li Y, et al. Outcomes of Manchester procedure combined with high uterosacral ligament suspension for uterine prolapse. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49(4):1273-1282. doi: 10.1111/jog.15574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter K, Albrich W. Long-term results following fixation of the vagina on the sacrospinal ligament by the vaginal route (vaginaefixatio sacrospinalis vaginalis). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(7):811-816. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(81)90709-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dastur AE, Tank PD. Archibald Donald, William Fothergill and the Manchester operation. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2010;60(6):484-485. doi: 10.1007/s13224-010-0058-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husby KR, Lose G, Klarskov N. Trends in apical prolapse surgery between 2010 and 2016 in Denmark. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(2):321-327. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3852-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0749-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10-17. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717-1727. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Utomo E, Blok BF, Steensma AB, Korfage IJ. Validation of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) in a Dutch population. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(4):531-544. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2263-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Utomo E, Korfage IJ, Wildhagen MF, et al. Validation of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6) and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7) in a Dutch population. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(1):24-31. doi: 10.1002/nau.22496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dongen H, van der Vaart H, Kluivers KB, et al. Dutch translation and validation of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire–IUGA Revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(1):107-114. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3718-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute for Medical Technology Assessment . Questionnaires for the measurement of costs in economic evaluations. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://www.imta.nl/questionnaires/

- 28.Srikrishna S, Robinson D, Cardozo L. Validation of the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) for urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(5):523-528. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1069-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al. Defining success after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):600-609. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b2b1ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detollenaere RJ, den Boon J, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with suspension of the uterosacral ligaments in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: multicentre randomised non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2015;351:h3717. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Vaart LR, Vollebregt A, Milani AL, et al. Pessary or surgery for a symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: the PEOPLE study, a multicentre prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2022;129(5):820-829. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dietz V, Schraffordt Koops SE, van der Vaart CH. Vaginal surgery for uterine descent; which options do we have? a review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(3):349-356. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0779-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IBM Corp . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. IBM Corp; 2017.

- 34.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Accessed July 19, 2023. https://www.R-project.org

- 35.Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, Klarskov N. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(11):1887-1893. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunes M, Johannesson U, Drca A, et al. Recurrent surgery in uterine prolapse: a nationwide register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101(5):532-541. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engelbredt K, Glavind K, Kjaergaard N. Development of cervical and uterine malignancies during follow-up after Manchester-Fothergill procedure. J Gynecol Surg. 2020;36(2):60-64. doi: 10.1089/gyn.2019.0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husby KR, Gradel KO, Klarskov N. Endometrial cancer after the Manchester procedure: a nationwide cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(7):1881-1888. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05196-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurian R, Kirchhoff-Rowald A, Sahil S, et al. The risk of primary uterine and cervical cancer after hysteropexy. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(3):e493-e496. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ayhan A, Esin S, Guven S, et al. The Manchester operation for uterine prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;92(3):228-233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kow N, Goldman HB, Ridgeway B. Uterine conservation during prolapse repair: 9-year experience at a single institution. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22(3):126-131. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smilen SW, Saini J, Wallach SJ, Porges RF. The risk of cystocele after sacrospinous ligament fixation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(6 pt 1):1465-1471. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70041-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van IJsselmuiden MN, van Oudheusden A, Veen J, et al. Hysteropexy in the treatment of uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy versus sacrospinous hysteropexy-a multicentre randomised controlled trial (LAVA trial). BJOG. 2020;127(10):1284-1293. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(2):252-252. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swift SE, Tate SB, Nicholas J. Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: what is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(2):372-377. doi: 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00698-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oversand SH, Staff AC, Borstad E, Svenningsen R. The Manchester procedure: anatomical, subjective and sexual outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(8):1193-1201. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3622-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolstrup CK, Husby KR, Lose G, et al. The Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: a matched historical cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(3):431-440. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3519-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gold RS, Amir H, Baruch Y, et al. The Manchester operation—is it time for it to return to our surgical armamentarium in the twenty-first century? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;42(5):1419-1423. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2021.1983785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Enklaar RA, Knapen FMFM, Schulten SFM, et al. The modified Manchester Fothergill procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy with low uterosacral ligament suspension in patients with pelvic organ prolapse: long-term outcome. Int Urogynecol J. 2023;34(1):155-164. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05240-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulten SFM, Essers B, Notten KJB, et al. Patient’s preference for sacrospinous hysteropexy or modified Manchester operation: a discrete choice experiment. BJOG. 2023;130(1):99-106. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parekh M, Swift S, Lemos N, et al. Multicenter inter-examiner agreement trial for the validation of simplified POPQ system. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(6):645-650. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1395-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lemos N, Korte JE, Iskander M, et al. Center-by-center results of a multicenter prospective trial to determine the inter-observer correlation of the simplified POP-Q in describing pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(5):579-584. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1593-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobak WH, Rosenberger K, Walters MD. Interobserver variation in the assessment of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996;7(3):121-124. doi: 10.1007/BF01894199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hall AF, Theofrastous JP, Cundiff GW, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the proposed International Continence Society, Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, and American Urogynecologic Society pelvic organ prolapse classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(6):1467-1470. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70091-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park YJ, Kong MK, Lee J, et al. Manchester operation: an effective treatment for uterine prolapse caused by true cervical elongation. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60(11):1074-1080. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.11.1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walsh CE, Ow LL, Rajamaheswari N, Dwyer PL. The Manchester repair: an instructional video. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(9):1425-1427. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3284-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milani AL, Damoiseaux A, IntHout J, et al. Long-term outcome of vaginal mesh or native tissue in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(6):847-858. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3512-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Brubaker L, et al. Effect of uterosacral ligament suspension vs sacrospinous ligament fixation with or without perioperative behavioral therapy for pelvic organ vaginal prolapse on surgical outcomes and prolapse symptoms at 5 years in the OPTIMAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1554-1565. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023-1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Husby K, Lose G, Kopp TI, et al. The Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy in the treatment of uterine prolapse: a matched cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(1)(suppl 1):S3-S4. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan AS, Chang OH, Ferrando CA. Perioperative adverse events in women undergoing vaginal prolapse repair with uterine preservation versus concurrent hysterectomy: a matched cohort study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(10):621-626. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000001011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colombo M, Milani R. Sacrospinous ligament fixation and modified McCall culdoplasty during vaginal hysterectomy for advanced uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(1):13-20. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70245-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, et al. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201-1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Anatomical Outcomes According to POP-Q System Preoperative, 1 and 2 Years Postoperative

eTable 2A. Patient Reported Outcomes Pre-operative and 6 Months Postoperative

eTable 2B. Patient Reported Outcomes 1 and 2 Years Post-operative

eTable 3. Subgroup Analysis for the Primary Outcome (Composite Outcome of Success)

eTable 4. Surgical Procedures and Perioperative Outcomes

eTable 5. Description of Loss to Follow-up

eTable 6. Description of Deaths During Follow-up

eTable 7. Participating Centers and Their Surgeons

eAppendix. Description of Surgical Techniques of SAM Study

Data Sharing Statement